Abstract

Universities offering agricultural programmes have the potential to complement public agricultural extension and advisory services because they are at the centre of knowledge generation—through research, teaching and community outreach programmes. The purpose of this study was to determine farmers’ acceptability of university agricultural extension and the factors influencing their decision. Using probability sampling, a sample of 442 participants from Gauteng Province were selected for inclusion in the survey to collect data through face-to-face interviews. Primary data were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis and Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) found in IBM SPSS version 27. The results showed that a significant proportion of the respondents favoured the introduction of university agricultural extension to complement public extension services as part of a pluralistic extension system. Furthermore, most of the farmers were willing to pay for extension services and were optimistic about the perceived benefits of associating with universities. The exploratory factor analysis revealed that access to research resources, improved extension services and training, and diffusion of university research were the three factors underlying the acceptability of university agricultural extension. It is suggested that a formal framework for pluralistic extension system should be developed through a participatory process that involves all stakeholders.

1. Background and introduction

In most countries throughout the world, government has been the main provider of agricultural extension services (Ajayi, Citation2006; Anderson & Feder, Citation2004; Cary, Citation1993; Kidd et al., Citation2000; Magoro & Hlungwani, Citation2014; Maoba, Citation2016). However, many countries have been reforming their public extension services because they are struggling to meet the demand for services due to high costs, limited resources, changes in extension philosophies or approaches, and slow increase in public funding activities (Afful & Lategan, Citation2014; Anderson & Feder, Citation2004; Picciotto & Anderson, Citation1997). In some countries, reforms are propagated by financial discipline implemented by the state; and agricultural extension has become a victim (Bennett, Citation1996; Kidd et al., Citation2000; Qamar, Citation2005). Generally, the main purpose of these reforms is to ensure that farmers are provided with the best agricultural extension services that are financially sustainable (Afful & Lategan, Citation2014; Kidd et al., Citation2000). Many countries have come up with agricultural extension reform strategies; these reforms are either market or non-market strategies (Laurent et al., Citation2006; Rivera et al., Citation2000). Market reforms include pluralism, cost recovery, total privatisation and revision of public-sector extension services, while non-market reforms comprise decentralisation/devolution (transferring power to local government) and subsidiary (Rivera et al., Citation2001). In general, market reforms are adopted in developed countries, whereas non-market reforms are common in developing countries—mainly because most farmers in developing countries are not willing to pay for agricultural extension services that form part of market reform (Afful, Citation2012; Ali et al., Citation2008; Foti et al., Citation2007; Oladele, Citation2008; Qamar, Citation2005). Agricultural extension reforms have yielded positive results in some countries but failed in others. In general, participatory reforms have been successful compared to fee-for-service, especially in low-income countries where there has been evaluation of the reforms (Davis, Citation2008). Participatory extension reforms have succeeded because they involve farmers and various stakeholders in planning and decision-making. On the other hand, fee-for-service extension systems may have failed because farmers cannot afford to pay for the services due to the low income earned from agricultural activities. For example, the willingness of the farmers to pay for extension services has been reported to be positively and significantly correlated with income (Ajayi, Citation2006; Loki et al., Citation2019; Oladele, Citation2008; Shausi et al., Citation2019; Uddin et al., Citation2016). Therefore, farmers with low farm income are reluctant to pay for extension services and are likely to contribute less.

In South Africa, the reform of agricultural extension started in 1994, after the new, democratically elected government came into power; the reform was aimed at correcting the dualistic agricultural extension services created by the apartheid government (Department of Agriculture DoA, Citation2005; Düvel, Citation2004; Koch & Terblanché, Citation2013; Ngomane, Citation2010; Phuhlisani, Citation2008). The dualistic system mainly benefited white farmers because the majority of them were commercial farmers, compared to black farmers who were farming on small-scale settings. For example, 90 000 white farmers were allocated about 3 000 agricultural extension officers with easy access to credit, marketing and guaranteed prices whereas 600 000 black farmers had less than 1 000 extension officers allocated to them (Lipton, Citation1972; Phuhlisani, Citation2008). Smallholder farmers who are mainly blacks, were oppressed by the apartheid system which segregated them from their white counterparts (Düvel, Citation2004). As a result, white farmers had better access to extension services compared to black farmers. Because of that, extension services offered to black farmers were characterised by poor quality, low effectiveness due to unqualified extension personnel, outdated extension methods and approaches, lack of coordination between government and agricultural corporations, insignificant relationship between extension and research; and low utilisation of farmer’s training centres (Hayward & Botha, Citation1995). Extension services offered to white farmers were of good quality because most of them are large-scale commercial farmers. Nonetheless, the reform changed agricultural extension services in South Africa from dualistic services (separate services for commercial and small-scale farmers) to amalgamated services focused on both small-scale farmers and large-scale commercial farmers after 1994 (Department of Agriculture DoA, Citation2005; Koch & Terblanché, Citation2013). The amalgamated system increased the number of extension personnel and improved access to extension services amongst black farmers who were previously disadvantaged by the dualistic agricultural extension. For example, Phuhlisani (Citation2008) found that South Africa had about 2 155 extension agents in January 2007; about a year later, the number of extension officers increased to 2 800 (Williams et al., Citation2008). Few year later, it was reported that South Africa has about 3 369 extension officers employed by government in various provinces (Ngaka & Zwane, Citation2018). Despite the high number of extension agents in the country, Agricultural Research Council (ARC) reported that the average ratio was 1:873, which is above government’s recommended ratio (Agricultural Research Council ARC, Citation2011). According to the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), the low extension to producer ratio is due to the rapid increase in the number of smallholder farmers accessing land through land reform programmes and lack of clear definition of the target recipients of extension services (Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries DAFF, Citation2016). As a results, there is assumption that all rural people are involved in agricultural production and entitled to public extension and advisory services. Because of the change in policies that governed agricultural extension services in South Africa in the post-apartheid government era, small-scale farmers started to depend heavily on public extension services as they could not afford private extension services (Ngomane, Citation2002). This change in policy created a burden on the public extension system because there were high expectations from government extension services. It has been reported that South African public extension services are not coping with the demand for extension services because the support provided to small-scale and resource-poor farmers is limited; this is hindering their aspirations to develop from emerging into commercial farmers (Phiri, Citation2009). As a result, these farmers are not satisfied with the public extension services (Agholor et al., Citation2013; Ngomane, Citation2000; Phiri, Citation2009). Therefore, there is a need to reform agricultural extension services in South Africa in order to improve the quality and effectiveness of the extension and advisory services rendered to the farmers.

Globally, the reform of agricultural extension has shifted towards pluralistic extension delivery systems (Alimirzaei et al., Citation2019; Gemo et al., Citation2013; Knierim et al., Citation2017; Masangano et al., Citation2017; Nahdy et al., Citation2002; Rivera & Alex, Citation2004). A pluralistic extension system is about the provision of extension services by different organisations such as government, private sector and non-profit organisations (Klerkx & Proctor, Citation2013; Phillipson et al., Citation2016). Moreover, the system acknowledges the need to alleviate farmers’ challenges using different approaches because of the diversity of the farming systems used by different farmers (Gemo et al., Citation2013). In South Africa, the pluralistic extension system includes stakeholders such as government through the Ministry of Agriculture, agricultural cooperatives, commodity organisations and the private sector (Koch & Terblanché, Citation2013; Zwane, Citation2009). Moreover, Zwane (Citation2009) reported that research organisations, academic institutions, farmers’ unions and non-governmental organisations provide extension services to the farmers in South Africa. However, government is the main service provider of agricultural extension services in South Africa (Magoro & Hlungwani, Citation2014; Motiang & Webb, Citation2015; Nkosi, Citation2017; Zwane, Citation2009). Private agricultural extension services are profit driven and thus exclude poor farmers (Koch & Terblanché, Citation2013). This means that extension services rendered by the private sector are only accessible to commercial large-scale farmers and highly profitable agricultural enterprises. However, farmers’ unions and commodity organisations provide services to the farmers affiliated to them. Parallel to that, it is not mandatory for academic institutions such as universities to render agricultural extension services in South Africa. The provision of agricultural extension services by universities occurs at a limited scale through community engagement and outreach programmes. Nonetheless, from a societal perspective, university agricultural extension appears to be an attractive complement to public extension in South Africa. Universities may provide a viable option for pluralistic extension system because they are public-funded; besides, most of the universities offer agriculture and life sciences programmes. Again, university agricultural extension services can be accessible to poor farmers if there is a government framework for pluralistic extension delivery systems.

Internationally, university agricultural extension (cooperative extension) has been successful in many countries including the United States of America (USA), India, Nigeria and others (McLean, Citation2007; Okolo, Citation2010; Rodgers, Citation1992). For example, in the USA, university extension seated in land-grant universities has been the agent of innovation through research that improved the livelihoods of the beneficiaries (Franz & Townson, Citation2008). State agricultural universities and colleges in India have been successful in rendering extension and advisory services to their surrounding communities (Van den Ben & van den Ban, Citation2003). In South Africa, there is evidence that university agricultural extension played a critical role in the success of white commercial farmers during the apartheid era before the year 1994 (Ngomane, Citation2010). During that era, farmers had easy access to agricultural research and information from universities through the Department of Agriculture; however, the cordial relationship that existed between universities and the Department of Agriculture has weakened in recent years (Koch & Terblanché, Citation2013). As a result, university agricultural extension services have slowly diminished in both small-scale and commercial farming settings. The low participation of universities in rendering extension services is worrying because agricultural scholars at the universities are involved in agricultural development activities such as teaching, research, knowledge generation, curriculum and module development, and other academic activities. For example, universities generate knowledge about new agricultural innovations, ethnoveterinary medicine, farming practices, livestock and crop management, marketing of agricultural commodities, animal and crop breeding, adoption of innovations, land use planning, soil fertility and management and other important farming aspects. Knowledge generated by institutions of higher learning can be promoted by creating platforms that will link farmers with those institutions. It is because of that backdrop that university extension is perceived as an important stakeholder for pluralistic extension system in South Africa. Even though universities have the potential to participate in the provision of agricultural extension services in collaboration with government, it is unknown whether farmers are in favour of the pluralistic extension system that involves academic institutions. According to Pye-Smith (Citation2012), a pluralistic delivery system should be demand-led and should follow a participatory approach. Thus, the farmers’ acceptability of university agricultural extension is crucial because farmers are the main beneficiaries of extension services. To fill this knowledge gap, the research is aimed at exploring the acceptability of university extension as a complement to public extension services. The specific objectives of the study are as follows: to determine farmers’ acceptability of university agricultural extension as a complement to public extension; and identifying the important factors (predictors) influencing their decisions.

2. Methodology

The study was conducted in the Gauteng province of South Africa through a survey research design. The population of analysis consisted of farmers in Gauteng receiving agricultural extension and advisory services from government. Gauteng province was selected because there are about three universities offering various agricultural qualifications (agribusiness, agricultural economics and management, agricultural extension, animal production and science, agronomy, crop/plant production and science, entomology, plant pathology, pasture management and science, soil science and others). Moreover, about five of the universities in the province offer life science and other programmes that are related to agriculture. Therefore, most universities in Gauteng province are important stakeholders in agriculture through teaching, knowledge generation and development of agricultural innovations. Gauteng is the smallest province of South Africa; however, it has the highest population because it is the economic hub of the country with mining and industries. It contributes 35% of the gross domestic product (GDP) of South Africa, and 11% in Africa (Gauteng Enterprise Propeller GET, Citation2020). The province is multiracial because of labour influx from other provinces and African countries. According to Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970), a sample size of 368 is appropriate for a population of 9 000 to achieve a margin error of 5%. However, 442 participants were sampled because more farmers expressed interest to participate in the study during data collection. Most of the interested participants were found in community gardens where they are farming in groups. Although simple random sampling was used to select the targeted participants (368), an additional group of 74 farmers who showed interest were included in the study. Random sampling was chosen because it gives all the individual an equal opportunity to be selection for participation in the study (Acharya et al., Citation2013). The participants were farmers in community gardens, on agricultural plots and on large-scale farms. Before the data collection started, permission and ethical clearance were obtained from the Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD) and the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences (CAES) Research Ethics Review Committee of the University of South Africa (Unisa), respectively. A semi-structured survey instrument was utilised to collect data from the participants during face-to-face interviews. The survey instrument collected information about socio-demographic information (age, gender, marital status, education level, farmland size, farming experience and annual net farm income and farming category); acceptability of university agricultural extension and perceived advantages; access to extension services; perceptions about quality of extension services; and preferred extension delivery system and funding model for university extension; and perceived challenges of university extension. For the purpose of this paper, only information about farmer’s socio-demographic characteristics, acceptability of university extension and its advantages were selected to analysis. The other information was presented in the report for the main study that had different objectives. The survey instrument consisted of dichotomous, Likert-scale type, continuous and open-ended questions. However, for the purpose of this paper, only data from dichotomous and Likert-scale type questions was considered for analysis. A dichotomous question was asked about the acceptability of university agricultural extension as a complement to public extension. The possible responses to the question were “No” and “Yes”, denoted by zero (0) and one (1), respectively. Moreover, a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = uncertain, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree) was used to measure the perceived benefits of university agricultural extension. The five-point Likert scale consisted of 12 questions, which were later reduced to 10 – after performing exploratory factor analysis.

The study employed different methods of data analysis found in the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. The statistical analyses performed were a reliability test, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), descriptive statistics and binomial test. The first analysis involved determination of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient aimed at measuring internal consistency, and therefore an indicator of internal structure validity of the five-point Likert scale used to collect data. The analysis included all 12 Likert-scale type questions in the study. The coefficient value of Cronbach’s alpha obtained was 0.95. Thus, the internal consistency of the likert scale was satisfactory (Hair et al., Citation2006). There were no alpha values for each of the components extracted from the rotated matrix because the questions in the likert scale were not categorized. The factors and their items were extracted during rotation. All twelve (12) of the Likert-scale type questions were considered for exploratory factor analysis and descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistical analysis included frequencies, percentages, median, mean and interquartile range (IQR). The type of exploratory factor analysis used was Principal Axis Factoring (PAF). EFA was used to establish new variables associated with the acceptability of university extension and their correlation. EFA was chosen because it can reveal complex relationships that exist in a dataset by exploring it and testing predictions (Child, Citation2006). In the current study, one of the objectives was to identify important factors associated with the acceptability of university extension and their correlation. Thus, EFA was appropriate because it can extract the important predictors associated with a phenomenon. In addition, the study intended to develop a scale containing important factors that should be considered when investigating university extension services. Because of that, the questions in the Likert-scale were not grouped; thus, allowing EFA to do the classifications of the important factors and their items. According to Costello and Osborne (Citation2005), in social science research where exploratory factor analysis is applied, oblique rotations such as promax, direct oblimin and quartimin give better results than orthogonal rotations (Varimax, quartimax and equamax). Furthermore, oblique promax rotation was chosen because it gives better results than oblimin (Dien, Citation2010). As a result, Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) with promax rotation was employed in EFA. After performing exploratory factor analysis, all factor loadings above 0.50 were retained (Costello & Osborne, Citation2005; Hair et al., Citation2006). Subsequently, three factors with ten individual variables (items) were extracted. Two of the extracted factors had two or more variables (items); thus, they met the minimum requirements of three item factor. However, one factor had two items. The factor with two items was accepted because the variables were highly correlated (p < 0.001; rs = 0.70). According to Yong and Pearce (Citation2013), a rotated factor with two variables should be considered reliable if the variables are highly correlated with each other. All 10 of the variables that constituted three retained factors were subjected to internal consistency test. Thus, all ten items extracted were grouped according to the factors they were associated with. The coefficient values of Cronbach’s alpha obtained for factors 1, 2, and 3 were 0.91, 0.88 and 0.86, respectively. Therefore, the internal consistency of the likert scale was satisfactory for all the three factors. According to Taber (Citation2018), alpha values of 0.84–0.90 are considered reliable, whereas 0.91–0.93 is strongly reliable.

Furthermore, a binomial test was performed to test the hypothesis for dichotomous data. The purpose of the binomial test was to determine the significant difference between the respondents who were willing to accept university agricultural extension against the hypothesised proportions. The same principle was applied to the proportions of the respondents willing to pay for university extension services. The significant difference was determined at a 5% significance level (p ≤ 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

The results of socio-economic information showed that 68.1% of the respondents were non-commercial farmers and 31.9% classified themselves as commercial farmers. Therefore, more than two-thirds of the farmers who receive public extension and advisory services did not sell all their produce for income generation to sustain their livelihoods. This may be due the fact that most farmers were found in community gardens where sharing of produce and selling were common. In such settings, the purpose of farming is to sell some of the produce to earn income, while saving some of the produce for home consumption. Therefore, such farmers cannot categorize themselves as commercial farmers because they do not sell all their produce. From farmland perspective, it was found that on average, farm/plot size of the respondents was 4.55 ha with a minimum of 0.001 ha and a maximum of 72 ha. The standard deviation and standard error of mean achieved were 8.17 and 0.39, respectively. The Coefficient of Variation (CV) percentage achieved was 179.6%, which showed that the variation in the farm/plot size occupied by the respondents was extremely high. It implied that there were farmers who occupied very small farms/plots while others had large-scale farms. Most of the farmers with plot/farm size of less than one hectare (<1 ha) were found in community gardens located in the schools, open spaces in the community, clinics and municipal land. Community gardens were in urban areas where land is limited because of high population density. The current study found that on average, farmers who received public extension and advisory services in Gauteng province have been farming for six years (actual is 6.3). The minimum and maximum farming experience of the farmers was 0.2 years (two months) and 34 years, respectively. A standard deviation of 5.35 and standard error of mean of 0.25 were achieved. The variation of farming experience was high because the CV% obtained was 84.9%. The study measured the annual farm income and found that the average annual net farm income of the respondents in the previous year was R21 387.56 with a minimum of R0 and a maximum of R410 000. Farmers who had R0 as their farm net income in the previous year were mostly from vegetable gardens and those who lost their products. Some of the farmers in community gardens shared vegetables rather than selling them to earn an income, hence, their income was zero from farming activities. The standard error of the mean and standard deviation were 2404.61 and 50,553.95, respectively.

3.2. Acceptability of university agricultural extension and perceived benefits

The results of the farmers’ acceptability of university agricultural extension showed that 91.2% of the respondents were in favour of including universities as part of a pluralistic extension system in the study area, whereas 8.8% were against the idea. The assumption (alternative hypothesis) was that most farmers (≥51%) would accept university agricultural extension as a complement to public agricultural extension and advisory services. A significant value (p < 0.001) was obtained from the results of the binomial test; thus, the alternative hypothesis is accepted. Moreover, the majority (55.4%) of the respondents were willing to pay for extension and advisory services offered by universities, while 44.6% were not. With the assumption that most farmers would be willing to pay for extension and advisory services, a statistically significant p-value of 0.035 was achieved from the results of the binomial test. Therefore, the hypothesis is accepted because a significant proportion of the respondents were in favour of paying for extension and advisory services rendered by universities.

The results regarding perceived benefits of university agricultural extension are presented in Table . The descriptive statistical outputs in Table indicate that on average, 79.3% of the respondents accepted university agricultural extension and advisory services as part of the pluralistic extension system. This is shown by the proportion of “agree” and “strongly agree” combined. An average median score of 4.0 also supports this. All the variables that measured perceived benefits of university agricultural extension achieved a median score of 4.0. Furthermore, the findings in Table depict that more than four-fifths (>80%) of the respondents perceived five benefits of university agricultural extension and advisory services as the most important. In chronological order, the three most important benefits are better access to agricultural extension and advisory services (86.7%), access to formal education and training (85.1%), and receiving advice from subject matter experts (84.1%). The other important benefits perceived by the respondents were creating an environment for universities to conduct research that is responsive to the farmers’ needs (83.3%), allowing universities to communicate their research findings to the farmers (81%) and enabling universities to develop a curriculum that is relevant to the society and to benefit the farmers (80.7%). About three-quarters of the respondents held the notion that university agricultural extension and advisory services will enable universities to use their community engagement and outreach activities to benefit the farmers (78.3%) and to provide farmers with access to research infrastructure (75.4%). Again, the same proportional representation (about three-quarters) of the respondents perceived university agricultural extension and advisory services as a system that will enable farmers to access research innovations (75.3%) and link universities with practical extension work (75.1%). On the other hand, less than three-quarters of the respondents perceived university extension as a system that will provide farmers with access to research funding (73.6%) and research journals (73.3%). In general, the results show than nearly four-fifths (79.3%) were optimistic about the perceived benefits of university agricultural extension and advisory services presented in Table . Therefore, most of the farmers in the study area are aware of the potential benefits of allowing universities to render agricultural extension and advisory services in collaboration with government. In addition, the respondents were well informed about some of the happenings at the universities that offer agricultural programmes (qualifications). Hence, a large proportion of the farmers were in agreement with the statements that measured the perceived benefits of university agricultural extension and advisory services.

Table 1. Perceived benefits of the acceptability of university agricultural extension (n = 442)

3.3. Exploratory factor analysis of underlying factors

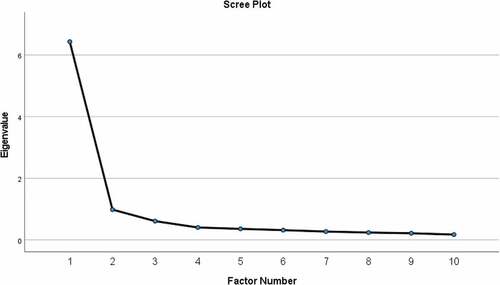

As explained in the methodology section, Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) with promax rotation was conducted using the data presented in Table . The purpose of exploratory factor analysis was to categorise the underlying factors (dimensions) of the acceptability of university agricultural extension in the study area. The results of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were 0.92 and 3392.38 (chi-square value), respectively. Moreover, the KMO results were statistically significant at 1% (p < 0.001). According to Kaiser (Citation1970), a KMO value of ≥ 0.90 implies that the data is suitable for factor analysis. Therefore, the sample size and data were appropriate for factor analysis because there was internal coherence of the data. To select Total Percentage of Variance-Accounted-For (PVAF) in the variables, a scree plot was utilised. The scree plot in Figure indicates that the decrease of the elbow starts at factor 4 with an eigenvalue of 0.40. As a result, the first three factors before the graph started forming an elbow (decreasing) were retained.

Table presents the results of the exploratory factor analysis of the acceptability of university agricultural extension. The results in Table depict that three extracted factors contributed 80.241% of the variance. The three extracted factors have been named 1) Access to research resources, 2) Improved extension services and training; and 3) Diffusion of university research. Factor 1 consists of five items (variables) that account for 64.32% of the total variance. Factor 2 and Factor 3 contributed to 9.84% and 6.09% of the total variance, respectively. Both Factor 2 and Factor 3 had less than four items, and Factor 2 had the lowest number of items (2). Factor 1 had the highest eigenvalue of 6.43, followed by Factor 2 with 0.98 and 0.61 for Factor 3. The factor loading for most of the items in Table was greater than 0.60; therefore, there was correlation between the extracted factors and their items. The variables (items) for Factor 1 (Access to research resources) were farmers’ access to the following: research infrastructure, funding, journals and innovations; and linking universities with practical extension work. It shows that most farmers were aware that research is one of the core functions of universities in the society. Better access to agricultural extension and advisory services; and access to formal education and training were the items that constituted Factor 2 (Improved extension services and training). Even though factor 2 has two items, it was accepted because the two variables were highly correlated (rs = 0.70) . On the other hand, Factor 3 (Diffusion of university research) consisted of the following items: the capabilities of universities to communicate their research findings to the farmers, universities conducting research that is responsive to the farmers’ needs, and farmers receiving advice from subject matter experts. Furthermore, the communalities of the items ranged between 0.66 and 0.83; therefore, most variation has been extracted. It implied that 66%–83% of the variability in the perceived benefits of university agricultural extension is explained by factors 1–3.

Table 2. Results of the exploratory factor analysis of the acceptability of university agricultural extension (n = 442)

After extracting and naming three important factors underlying the acceptability of university agricultural extension, factor correlation was performed. The results of the factor correlation matrix showed that Factor 1 was positively correlated with Factor 2 (rs = 0.658). The results implied that those respondents who held the opinion that university agricultural extension would provide access to research resources believed that they would gain improved access to extension services and training. Furthermore, the same farmers perceived improved access to research resources as a way of diffusing university research to the farmers (rs = 0.702). Again, Factors 2 and 3 were positively correlated (rs = 0.704). It implied that the respondents who perceived university agricultural extension as a way of improving access to extension services and training held the notion that universities will improve diffusion of research from institutions of higher learning.

4. Discussion

The study discovered that a significant proportion of the respondents accepted university agricultural extension as a complement to public (government) agricultural extension and advisory services. Most of the farmers were willing to pay for pluralistic extension services that include universities. It showed that farmers were familiar with the differences that exist between government and institutions of higher learning about the provision of extension and advisory services. Furthermore, the farmers held the notion that to receive quality extension and advisory services it is necessary to pay universities to render the services in collaboration with government. It implied that farmers in the study area were in favour of a pluralistic extension system offered by government and institutions of higher learning; therefore, introducing pluralistic extension in the study area is demand-driven. Pye-Smith (Citation2012) reported that a pluralistic delivery system should be demand-led and participatory—to enable universities to render services that are responsive to farmers’ needs. In support of the study findings, Chowa et al. (Citation2013) found that farmers accepted pluralistic extension because it provided access to extension services from various sources, as well as diversified information. Thus, acceptability of a pluralistic extension system can be influenced by the perceived benefits of receiving support from different institutions and practices. For example, Kabir et al. (Citation2020) reported that a pluralistic support system is responsive to farmers’ needs and demands. In the current study, the need to include universities in the pluralistic extension system is demand-led and this shows that farmers know what they need from institutions of higher learning to improve their farming activities. As a result, the system is more likely to respond to the needs of the farmers and to ultimately succeed in the delivery of extension services. However, that could only happen if farmers are involved in the planning and implementation of pluralistic extension systems that are suitable for the study area and responsive to the farmers’ needs. The participation of farmers in developing a sustainable framework for a pluralistic extension system cannot be overlooked because the success of extension services is measured on the progress made by the farmers (beneficiaries). Besides, farmers’ willingness to pay for extension and advisory services offered by universities is an indication that their participation in the development of a pluralistic extension system is crucial. Again, the findings implied that most farmers wanted to deviate from solely depending on free extension and advisory services from government because they were willing to pay for university agricultural extension services. Determining farmers’ willingness to pay for extension services has been widely explored in contexts where the feasibility of privatising extension services was evaluated. There is a degree of polarisation on the payment of extension services by farmers. Similarly, Budak and Budak (Citation2010); Ozor et al. (Citation2013); Afful et al. (Citation2014); Uddin et al. (Citation2016); and Loki et al. (Citation2019) found that most farmers are willing to pay for agricultural extension services. In contrast, Foti et al. (Citation2007); Ali et al. (Citation2008); as well as Oladele (Citation2008) discovered that the willingness to pay for extension services was low amongst the farmers. Although most of the farmers expressed interest to pay for university extension services rendered through a pluralistic extension system, it is important to determine whether farmers can afford to pay for such services. Determining farmers’ financial capability is important because payment for extension services can be influenced by income, access to services and other factors. Several scholars have reported a positive and significant correlation between farmers’ income and their willingness to pay for extension services (Ajayi, Citation2006; Loki et al., Citation2019; Oladele, Citation2008; Shausi et al., Citation2019; Uddin et al., Citation2016). Therefore, even farmers who have expressed their willingness to pay for university extension services may be reluctant to do so if the prices are unaffordable.

The exploratory factors that influenced the acceptability of university agricultural extension included access to research resources, improved extension services and training, and diffusion of university research. The most important factor was access to research resources and it consisted of four items namely infrastructure, funding, journal innovations and linking universities with practical extension work. Farmers’ expectation of universities to provide access to research funding is not far-fetched because most universities are involved in research projects funded by various stakeholders. In South Africa, government provides core funding for research at universities through the Ministry of Higher Education (Luruli & Mouton, Citation2016). Considering that most of the universities in South Africa are public institutions, it is not surprising that farmers perceive their association with universities as a way to access research funds. According to Cloete et al. (Citation2015), the role of universities is to conduct research and to provide services to the public. In this context, universities can utilise their research funds to conduct some of their research on the farms of the recipients of university agricultural extension services. By so doing, universities will undertake research that is responsive to the needs of the farmers and will link universities with practical extension work. In terms of research journals, farmers who accepted university agricultural extension did not perceive access to research journals as a benefit associated with access to extension services from universities, although institutions of higher learning are affiliated with databases that provide access to academic journals. University personnel can easily access research articles from academic journals and share them with farmers. Besides, scholars have the capacity to explain academic and scientific information in the language that farmers can understand. However, access to research journals did not influence the farmers’ perception positively. The reason could be that most academic research documents are limited to peer review rather than transferring knowledge to the main beneficiaries (Atchoarena & Holmes, Citation2005). As a result, some of the scientific jargon utilised in academic journals may be difficult for farmers to understand without the help of subject experts. Besides, farmers in the study area may be unfamiliar with the advantages of how access to information from academic journals can improve their productivity.

The second important exploratory factor was improved extension services. The respondents held the notion that universities would offer better access to agricultural extension and advisory services and provide them with access to formal education and training. It was envisaged that farmers would expect universities to provide access to extension services and education because the common role of universities is to facilitate access to education in the society. In some instances, universities provide agricultural extension services and access to higher education simultaneously (Douglass, Citation2007). That is applicable in countries where agricultural universities are expected to generate and apply knowledge to improve agricultural production (Gornitzka & Maassen, Citation2007; Okolo, Citation2010). In South Africa, however, the provision of university agricultural extension services is not mandatory because universities are housed in the Ministry of Higher Education and Training, whereas the Ministry of Agriculture is responsible for extension and advisory services. Thus, to meet the farmers’ expectations, universities in the study area could establish community engagement and outreach programmes that create a conducive environment for the provision of extension services and informal educational programmes that provide for the farmers’ needs. Informal educational programmes will deviate from normal university admission requirements that may exclude most of the farmers. In addition, a formal framework for a pluralistic extension system could remedy the envisaged problem.

Diffusion of university research was the last exploratory factor that influenced the willingness of farmers to accept university agricultural extension services. The assumption was that university agricultural extension services would create a platform for universities to communicate (share) their research findings with the farmers. By so doing, farmers will receive advice from subject matter experts working at the universities. As a result, universities will conduct research that is responsive to the farmers’ needs.The results of the exploratory factor analysis indicated diffusion of university research as the underlying factor associated with farmers’ acceptability of university agricultural extension services. According to Cloete et al. (Citation2015), it is mainly because the role of universities is to produce scientific knowledge through research and to provide expertise that resolve persistent developmental issues in the society. Through research, universities have contributed to agricultural development in many countries (Atchoarena & Holmes, Citation2005; Johanson et al., Citation2008; Liu & Tao, Citation2020; Okolo, Citation2010). Universities’ research can only contribute to development if the findings are communicated to the target audience (beneficiaries), though. Hence, farmers in the study area perceived their association with universities as a way to access the research outcomes of universities. Farmers’ expectations are parallel to the traditional role of agricultural extension, which is diffusion of the research results to the farmers.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The provision and payment of university agricultural extension services are widely accepted by farmers as a suitable mechanism for a pluralistic extension system in the Gauteng province of South Africa. The study findings implied that the necessity for a pluralistic extension system in the study area is demand-driven because most of the farmers were in favour of the proposal.

The theoretical contribution of the study is that the need for pluralistic extension and payment of services from institutions of higher learning is widely accepted by the recipients of extension services (agricultural producers). The assumption is that pluralistic extension system involving universities will improve farmer’s access to research resources, extension services and training, and diffuse university research. Thus, the study contributes to the existing theory by explaining the factors that will help to explain acceptability of pluralistic extension involving universities. In addition, the study makes a practical contribution towards the development of sustainable framework for pluralistic extension system involving institutions of higher learning. In conclusion, there is a need for universities to render extension services in collaboration with government to improve farmer’s access to extension services and research resources. Most importantly, the agricultural extension services of universities should enable farmers to access the required funding as well as research articles from journals. It is recommended that a formal framework for a pluralistic extension system should be developed through a participatory process that involves the Ministry of Higher Education and Training, the Ministry of Agriculture, farmers and other stakeholders. Furthermore, the implementation of a pluralistic extension system should consist of concerted efforts between all the stakeholders to avoid duplication of efforts and waste of resources. The framework for a pluralistic extension system should enable universities to provide research resources to the farmers; improve access to extension services and trainfarmers; and create a platform for the diffusion of university research outcomes to the farmers. Other extension studies may use EFA to explore factors associated with the acceptability of pluralistic extension services. The limitation of the study is that it only focused on farmer’s acceptability of university extension and perceived advantages using structured questions. Therefore, is a need to determine whether universities have capacity to render extension services required by farmers. In addition, the benefits and perceived challenges of university extension can be investigated from farmers, government personnel and university academic staff members.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and convey gratitude to the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences (CAES) of the University of South Africa (Unisa) for funding the study through the College Research Fund. Moreover, we appreciate all farmers in Gauteng province who participated in the study, Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD) for granting permission to conduct the study, agricultural advisors from GDARD and research assistants who made it possible for the study to be conducted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

M.M.S. Maake

Matome Moshobane Simeon Maake is a Lecturer in the Department of Agriculture and Animal Health at the University of South Africa (UNISA) and a PhD candidate at the same University. He hold Masters Degree, Bachelor of Technologiae and National Diploma in Agriculture from Tshwane University of Technology. The focus of his research work is the acceptability of University-based agricultural extension as a complement to public extension services.

M.A. Antwi

Michael Akwasi Antwi is an agricultural economist and Full Professor in the Department of Agriculture and Animal Health at the University of South Africa. Prof. Antwi obtained BSc (Honours), MSc and PhD in Agricultural Economics from University of Science and Technology in Ghana, University of Pretoria and North West University in South Africa, respectively. His research fields are food security, land reform, climate change, cooperatives, marketing, economic viability analysis, evaluation/impact assessment, poverty alleviation, economic efficiency, technology adoption and rural finance.

References

- Acharya, A. S., Prakash, A., Saxena, P., & Nigam, A. (2013). Sampling: Why and how of it. Indian Journal of Medical Specialties, 4(2), 330–15. https://doi.org/10.7713/ijms.2013.0032

- Afful, D. B. 2012. Payment for the delivery of agricultural extension services: a need-based analysis of medium and small-scale commercial crop farmers in the Free State Province of South Africa [ PhD thesis. Unpublished]. University of Fort Hare.

- Afful, D. B., & Lategan, F. S. (2014). User contributions and public extension delivery models: Implications for financial sustainability of extension in South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 42, 39–48.

- Afful, D. B., Obi, A., & Lategan, F. S. (2014). Understanding situational incompatibility of payment for the delivery of public extension services. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 6(4), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2013.0479

- Agholor, I. A., Monde, N., Obi, A., & Sunday, O. A. (2013). Quality of extension services: A case study of farmers in Amathole. Journal of Agricultural Science, 5(2), 204–212. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v5n2p204

- Agricultural Research Council (ARC). (2011). Concept towards sustainable agricultural development. ARC.

- Ajayi, A. O. (2006). An assessment of farmers’ willingness to pay for extension services using the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM): The case of Oyo state, Nigeria. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 12(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240600861567

- Ali, S., Ahmad, M., Ali, T., Islam-Ud-Bin, S., & Iqbal, M. Z. (2008). Farmers’ willingness to pay (WTP) for advisory services by private sector extension: The case of Punjab. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 45(3), 107–111.

- Alimirzaei, E., Hosseini, S. M., Hejazi, S. Y., & Movahed Mohammadi, H. (2019). Executive coherence in Iranian pluralistic agricultural extension and advisory system. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 21(3), 531–543.

- Anderson, J. R., & Feder, G. (2004). Agricultural extension: Global intentions and hard realities. World Bank Research Observer, 19(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkh013

- Atchoarena, D., & Holmes, K. (2005). The role of agricultural colleges and universities in rural development and lifelong learning in Asia. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development, 2(1362–2016–107652), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.37801/ajad2005.2.1-2.2

- Bennett, C. F. (1996). Rationale for public funding of agricultural extension programs. Journal of Agriculture and Food Information, 3(4), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/J108v03n04_02

- Budak, D. B., & Budak, F. (2010). Livestock producers’ needs and willingness to pay for extension services in Adana province of Turkey. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 5(11), 1187–1190. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR09.567

- Cary, J. W. (1993). Changing foundations for government support of agricultural extension in economically developed countries. Sociologia Ruralis, 3(4), 336–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.1993.tb00968.x

- Child, D. (2006). The essentials of factor analysis (3rd ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Chowa, C., Garforth, C., & Cardey, S. (2013). Farmer experience of pluralistic agricultural extension, Malawi. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 19(2), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2012.735620

- Cloete, N., Maassen, P., & Bailey, T. (2015). Roles of universities and the African context. knowledge production and contradictory functions in African higher education. In N. Cloete, P. Maassen, & T. Bailey (Eds.), Knowledge production and contradictory functions in African higher education. African minds higher education dynamics series, 1. Cape Town: African minds (pp. 1–17). https://doi.org/10.47622/978-1-920677-85-5

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10(7), 1–9.

- Davis, K. R. (2008). Extension in Sub-Saharan Africa: Overview and assessment of past and current models and future prospects. Journal of International Agricultural Extension Education, 15(3), 15–28.

- Department of Agriculture (DoA). (2005). Norms and standards for extension and advisory services in agriculture. Department of Agriculture.

- Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF). (2016). National policy on extension and advisory services. DAFF.

- Dien, J. (2010). Evaluating two‐step PCA of ERP data with geomin, infomax, oblimin, promax, and varimax rotations. Psychophysiology, 47(1), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00885.x

- Douglass, J. A. (2007). The conditions for admission: Access, equity, and the social contract of public universities. Stanford University Press.

- Düvel, G. H. (2004). Developing an appropriate extension approach for South Africa: Process and outcome. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 33, 1–10.

- Foti, R., Nyakudya, I., Moyo, M., Chikuvire, J., & Mlambo, N. (2007). Determinants of farmer demand for“fee-for-service” extension in Zimbabwe: The case of Mashonaland Central province. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 14(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.5191/jiaee.2007.14108

- Franz, N. K., & Townson, L. (2008). The nature of complex organizations: The case of cooperative extension. In M. T. Braverman, M. Engle, M. E. Arnold, & R. A. Rennekamp (Eds.), Program evaluation in a complex organizational system: Lessons from cooperative extension (Vol. 120, pp. 5–14). New Directions for Evaluation.

- Gauteng Enterprise Propeller (GET). (2020). Annual performance plan for 2019/20. GET.

- Gemo, H. R., Stevens, J. B., & Chilonda, P. (2013). The role of a pluralistic extension system in enhancing agriculture productivity in Mozambique. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 41, 59–75.

- Gornitzka, Å., & Maassen, P. (2007). An instrument for national political agendas: The hierarchical vision. In University dynamics and European integration, J. Olsen & P. Maassen. Springer (pp. 81–98).https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5971-1_4

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hayward, J., & Botha, C. (1995). Extension, training and research. In R. Singini & J. Van Rooyen (Eds.), Serving small scale farmers: An evaluation of DBSA’s farmer support programmes. Development Bank of Southern Africa.

- Johanson, R., Saint, W., Ragasa, C., & Pehu, E. (2008). Cultivating knowledge and skills to grow African Agriculture. In M. Tembon & L. Fort (Eds.), Girls’ Education in the 21st Century: Gender equality, empowerment and economic growth (pp. 239–253). The World Bank.

- Kabir, K. H., Knierim, A., & Chowdhury, A. (2020). Assessment of a pluralistic advisory system: The case of Madhupur Sal Forest in Bangladesh. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 26(3), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2020.1718719

- Kaiser, H. F. (1970). A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika, 35(4), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291817

- Kidd, A. D., Lamers, J. P. A., Ficarelli, P. P., & Hoffman, V. (2000). Privatising agricultural extension: Caveat emptor. Journal of Rural Studies, 16(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(99)00040-6

- Klerkx, L., & Proctor, A. (2013). Beyond fragmentation and disconnect: Networks for knowledge exchange in the English land management advisory system. Land Use Policy, 30(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.02.003

- Knierim, A., Labarthe, P., Laurent, C., Prager, K., Kania, J., Madureira, L., & Ndah, T. H. (2017). Pluralism of agricultural advisory service providers – Facts and insights from Europe. Journal of Rural Studies, 55, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.07.018

- Koch, B. H., & Terblanché, S. E. (2013). An overview of agricultural extension in South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 41, 107–117.

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Laurent, C., Cerf, M., & Labarthe, P. (2006). Agricultural extension services and market regulation: Learning from a comparison of six EU countries. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 12(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240600740787

- Lipton, M. (1972). The South African census and the Bantustan policy. The World Today, 28(6), 257–271.

- Liu, T., & Tao, P. (2020). Evaluating the effectiveness of university agricultural extension test stations using Wuli-Shili-Renli methodology. Ciência Rural, 51(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20190982

- Loki, O., Mudhara, M., Pakela-Jezile, Y., & Mkhabela, T. S. (2019). Factors influencing land reform beneficiaries’ willingness to pay for extension services in Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 47(4), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2019/v47n4a524

- Luruli, N. M., & Mouton, J. (2016). The early history of research funding in South Africa: From the research grant board to the FRD. South African Journal of Science, 112(5–6), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2016/20150097

- Magoro, M. D., & Hlungwani, S. S. (2014). The role of agricultural extension in the 21st century: Reflections from Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Extension, 2(1), 89–93.

- Maoba, S. (2016). Farmers’ perception of agricultural extension service delivery in Germiston Region, Gauteng province, South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 44(2), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2016/v44n2a415

- Masangano, C. M., Kambewa, D., Bosscher, N., & Fatch, P. (2017). Malawi’s experiences with the implementation of pluralistic, demand-driven and decentralised agricultural extension policy. Journal of Agricultural Extension & Rural Development, 9(9), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.5897/JAERD2017.0875

- McLean, S. (2007). University extension and social change: Positioning a university of the People in Saskatchewan. Adult Education Quarterly, 58(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713607305945

- Motiang, D. M., & Webb, E. C. (2015). Sources of information for smallholder cattle farmers in Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati district municipality in the North West province, South Africa. Applied Animal Husbandry and Rural Development, 8, 28–33.

- Nahdy, S., Byekwaso, F., & Neilson, D. (2002). Decentralized farmer-owned extension in Uganda. In S. A. Breth (Ed.), Food security in changing Africa. Geneva: Centre for applied studies in international negotiations.

- Ngaka, M. J., & Zwane, E. M. (2018). The role of partnerships in agricultural extension service delivery: A study conducted in provincial departments of agriculture in South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension (SAJAE), 46(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2018/v46n1a399

- Ngomane, T. 2000. Transformation and restructuring needs for smallholder irrigation projects in the Northern Province of South Africa: Makuleke farmers’ perspectives [ Master’s thesis. Unpublished]. University of the North.

- Ngomane, T. (2002). Public sector for the agricultural extension systems in the Northern province of South Africa: A system undergoing transformation. Journal of International Agricultural Extension Education, 9(3), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.5191/jiaee.2002.09304

- Ngomane, T. (2010). From a deficit-based to an appreciative inquiry approach in extension programs: Constructing a case for a positive shift in the current extension intervention paradigm. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 17(3), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.5191/jiaee.2010.17305

- Nkosi, N. Z. 2017. Level of access to agricultural extension and advisory services by emerging livestock farmers in Uthungulu District Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal province [ Master’s dissertation]. University of South Africa. Unpublished.

- Okolo, B. N. (2010). Nigerian universities and agriculture: Their role in the development of agriculture for sustainable food security. Journal of Developments in Sustainable Agriculture, 5(1), 23–30.

- Oladele, O. I. (2008). Factors determining farmers’ willingness to pay for extension services in Oyo state Nigeria. Agricultura Tropica et Subtropica, 41(4), 165–170.

- Ozor, N., Garforth, C. J., & Madukwe, M. C. (2013). Farmers’ willingness to pay for agricultural extension service: Evidence from Nigeria. Journal of International Development, 25(3), 382–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1849

- Phillipson, J., Proctor, A., Emery, S. B., & Lowe, P. (2016). Performing inter-professional expertise in rural advisory networks. Land Use Policy, 54, 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.02.018

- Phiri, C. 2009. Livestock, rural livelihoods and rural development interventions in the Eastern Cape: case studies of Chris Hani, Alfred Nzo and Amathole district municipalities [ Doctorate thesis]. University of Fort Hare,

- Phuhlisani. (2008). Extension and smallholder agriculture key issues from a review of the literature. Phuhlisani.

- Picciotto, R., & Anderson, J. R. (1997). Reconsidering agricultural extension. The World Bank Research Observer, 12(2), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/12.2.249

- Pye-Smith, C. 2012. Agricultural extension: A time for change: Linking Knowledge to policy and action for food and livelihoods. Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation. Online. Available from: Retrieved August 27, 2021. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/75389/1689_PDF.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Qamar, M. K. (2005). Modernising national agricultural extension systems: A practical guide for policy-makers of developing countries. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO).

- Rivera, W. M., & Alex, G. (2004). The continuing role of government in pluralistic extension systems. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 11(3), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.5191/jiaee.2004.11305

- Rivera, W. M., Qamar, M. K., & Van Crowder, L. 2001. Agricultural and rural extension worldwide: Options for institutional reform in the developing countries. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Online available from: Retrieved July 15, 2021. https://www.fao.org/3/y2709e/y2709e.pdf

- Rivera, W. M., Willem, Z., Gory, A., Vin, A., Crowder, L., & Andersen, J. V. (2000). Contracting for extension: Review of emerging practices – agricultural knowledge and information systems. Good practice Note.

- Rodgers, E. M. (1992). Prospectus for a cooperative extension system in education. Science Communication, 13(3), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/107554709201300305

- Shausi, G. L., Ahmad, A. K., & Abdallah, J. M. (2019). Factors determining crop farmers’ willingness to pay for agricultural extension services in Tanzania: A case of Mpwapwa and Mvomero Districts. Journal of Agricultural Extension & Rural Development, 11(12), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.5897/JAERD2019.1097

- Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

- Uddin, E., Gao, Q., & Mamun-Ur-Rashid, M. D. (2016). Crop farmers’ willingness to pay for agricultural extension services in Bangladesh: Cases of selected villages in two important agro-ecological zones. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 22(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2014.971826

- Van den Ben, A. W., & van den Ban, A. W. (2003). Funding and delivering agricultural extension in India. Journal of International Agricultural Extension Education, 10(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.5191/jiaee.2003.10103

- Williams, B., Mayson, D., De Satgé, R., Epstein, S., & Semwayo, T. (2008). Extension and smallholder Agriculture: Key issues from a review of the Literature. Phuhlisani.

- Yong, A. G., & Pearce, S. (2013). A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 9(2), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.09.2.p079

- Zwane, E. M. 2009. Participatory development of an extension approach and policy for Limpopo province, South Africa [ PhD Thesis]. University of Pretoria.