Abstract

This paper examines the roles of business improvement districts (BIDs) in revitalizing struggling neighborhoods and downtown areas in urban settings. For decades, New York City has been using BIDs as policy tool to help businesses thrive in rough areas. Previous research has shown that while BIDs can be very useful tool for enhancing the physical appearance, bringing in more foot traffic and increasing the property value in the districts where are instituted, they can also be a driver for complete transformation of a neighborhood by raising the real estate value. In doing so, they increase residential and commercial rental rates in the area. In addition to revitalizing dilapidated areas, BIDs can also be counterproductive by shifting the burden to low-income residents and small business owners. This paper outlines and documents the process through which BIDs transform an area from the perspectives of renters, business owners and BIDs directors in 16 of Brooklyn’s 25 BIDs districts. Using qualitative research design, we interviewed 46 participants in these districts, including 16 BIDs directors. The study shows in the process of transforming an area that BIDs produce immediate, intermediate, long-term and lasting impacts. Immediate impacts range from enhancing the physical appearance to increase in sales while intermediate and lasting impacts range from driving rental rates to complete social and cultural transformation of the area in few years.

Public Interest Statement

In all urban areas, there are many dilapidated areas. Dilapidation can be visible in the physical appearance of the place, which can leave the impression that the place is unsafe for residents, visitors and businesses. What local governments can do to help small businesses, homeowners and residents in these areas is often controversial. One policy in particular is known as business improvement district (BID), whereby local businesses and homeowners pay additional tax to be used for services that can attract customers. As a neighborhood is cleaning up, rental rates increase and real estate value appreciates. In a short period, the area becomes unaffordable to residents and small businesses and in the long-term the place will be completely transformed (or gentrified). Looking at 16 of the 25 BIDs areas in Brooklyn through the eyes of the local people, this paper explains how BID as a policy can have a negative impact on the groups it was intended to help.

1. Introduction

For decades, business improvement districts (BIDs) have been used as an economic development tool for small businesses in urban areas. A BIDs is a designated or mapped subdivision of a particular neighborhood, where property owners are required to pay an additional tax or assessment toward the funding of additional services within that designation or district. The evidence indicates that BIDs can transform a neighborhood by affecting rental rates and real estate value, making these areas very expensive for small businesses and low-income residents (Campagna, Citation2016; Hipler, Citation2007). As such, BIDs can be a vital tool for urban renewal, but they can also create challenges by shifting market forces. Largely, BIDS are acknowledged for improving physical appearance of neighborhoods and increasing sales for businesses and through this process they have been viewed to improve dilapidated neighborhoods by creating economic benefits for the entire community. However, not much has been documented about the process of transforming neighborhoods by increasing rental rates for small businesses and residents. More specifically, there is little known about how people who are affected the most by BIDs perceive the changes brought to their areas. This papers attempts to bridge this gap in the literature about BIDs by documenting the lived experiences of residents, business owners and BIDs directors in selected districts in the Borough of Brooklyn in New York City.

Currently, there are a total of 75 BIDs in NYC with the plan to add an additional 25 districts in the coming years (Elstein, Citation2016).) It is important for policymakers to understand that BIDs, as an economic development tool, are important particularly in the aftermath of the 2007/8 economic downturns. In theory, BIDs can be used to bolster the economy, create jobs, and pass along ripples of benefits for home and business owners. BIDs can also be used to strengthen the economic resilience of downtown areas, which have taken the center stage as key to rebuilding after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Looking at BIDs through the eyes of residents, BIDs directors and small business owners, this paper examines the economic impacts of BIDs on certain urban areas. Particularly, this study seeks to answer the question: how do BIDs influence the lived experiences of business owners, renters and residents in BIDs areas in Brooklyn in terms of their impacts on commercial rent, residential rent and property value? In answering this question, the paper threads together the process of neighborhoods transformation during and after the installment of BIDs in the area. This process is triggered by a combination of factors such as enhancement in physical appearance, perceived safety and rising desirability of the area, all of which are likely to increase real estate value, leading to continuous increase in rental rates and property taxes. As such, it is important to learn more about BIDs as their use continues to expand in New York City despite some of the negative outcomes.

Organizationally, this paper is divided into five sections. In this introductory section, we presented the challenges associated with using BIDS and the area where this paper contributes to expanding our knowledge about them. Section 2 provides reviewed literature on BIDs. Section 3 gives explanation of the research design and methodology used to conduct the study. Section 4 presents the study’s findings and finally Section 5 offers discussion of findings, theoretical implications and conclusion.

2. Literature review

This section provides the theoretical background and context for this study by situating BIDs within the literature on urban renewal and economic development policies in urban areas in the aftermath of the economic recession 2007/8. The section then proceeds to discuss the role that BIDs play as a policy tool.

2.1. Urban renewal and economic development

In the last 20‒30 years, changes in the postindustrial society have had drastic effects on cities. US economy has transitioned from manufacturing and production of goods to provision of services. This change created a shift in land use from industrial production to cultural production and consumption (Hamnett & Whitelegg, Citation2006; Wang, Citation2011). The visual transformation of urban communities was seen through the development of “stylish restaurants, bars, cafés and stores” (Wang, Citation2011 p. 364). The postindustrial change in the economy and the new demand for land use changed how cities are developed. Urban renewal/revitalization has been used as a development strategy for the past three decades. Particularly, urban renewal is conceptualized as the redevelopment of old buildings or slums within a large city (Wu, Citation2015). Historically, there have been two waves of urban renewal in the United States: first is the “old” urban renewal, dating from 1949 to 1974, and the second is the “new” urban renewal dating from 1992 to 2007 (Hyra, Citation2012). The first wave of urban renewal strategy was a plan to develop rundown property and impoverished areas surrounding central business districts for economic growth (Hyra, Citation2012). The aim for redeveloping cities was to attract middle-income suburban residents. The second wave described as “new” urban renewal was designed to expand downtowns. A major difference between the old and new renewal was that the first wave was enforced through federal policy. The shift from the old to new renewal strategies incited a new development of land/building use, with the creation of mixed-use developments.

In the after mass of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007/8, urban renewal policies became relevant because the economic recession left lasting impacts on how policymakers in municipalities respond to the relative collapse of the housing market, mass unemployment and the decrease in consumer spending. These issues affected millions of lives on a macroeconomic and microeconomic scale (Elwell, Citation2013). Under these conditions, governments (national and local) are constantly looking for policy tools that respond to the changing economy (Elwell, Citation2013; Seidman, Citation2012). One contentious issue that arises during recovery debates is what economic development means to various stakeholders.

Feldman, Hadjmichael, Lanahan and Kemenny (Citation2016) defined economic development as “the activities that expand capacities to realize the potential of individuals, firms, or communities who contribute to the advancement of society through the responsible production of goods and services” (p. 18). Quantitative measurability of these activities could be challenging because some of the metrics have the potential to be subjective and conditional. As such, the debate on economic development tools tends to center on economic growth because it is more tangible and measurable. Growth can also be viewed differently by diverse communities who occupy the urban landscape (Lin & Long, Citation2008). In these diverse communities, the impacts of economic development and the tools that are used can vary drastically between celebrated success and devastation (Lin & Long, Citation2008; Liu, Miller, & Wang, Citation2014). Consequently, the conversation surrounding economic development tools for urban communities can be polarizing because of the engendered disparities. Hyra (Citation2012) noted that urban renewal policies often impact cultural assets in urban neighborhoods which contribute to resident’s sense of place and identity. Specifically, urban renewal policies, of which BIDs are a part, often add attractive elements to a neighborhood such as housing, entertainment and eateries that attract higher-income residents forcing lower-income residents out (Hyra, Citation2012). Neighborhoods as a small composite of a larger landscape are usually more homogenous in social, political and economic attributes (Lin & Long, Citation2008). However, defining an urban setting has far-reaching repercussions. For instance, Johnson and Shifferd (Citation2016) argued that the limitations in defining neighborhoods by the Census Bureau have been constrained to a dichotomous comparison between how many people settle in urban areas versus rural areas. Porter and Howell (Citation2009) conquered that this dichotomy is changing into what they describe as a “continuum-based typology” (p. 590), for in more recent years, descriptions have expanded to include suburbs and exurbs as other distinctions within the urban landscape. Housing policies over the last 60 years along with changes in economy have contributed to the creation of the suburban landscape and how Americans would participate in their social and work life (Micklow & Warner, Citation2014; Nelson & Malizia, Citation2006). Clearly, the social construction of space deeply impacts neighborhoods in terms of marginalization, privilege and zoning regulations, in favor of protecting suburbia (Micklow & Warner, Citation2014).

These varying definitions and descriptions of changing landscapes are attributed to the social, political and economic development of a particular area or community. The identity of an urban context or landscape cannot be separated from the intentions of a city’s urban planning and development activities. Jacobs and Paulsen (Citation2009) noted that scholars “recognize the political power of development interests, debates over urban and regional form, the role of transportation, and, less often, planning as a method for managing social and racial conflicts”(p. 134). Urban renewal policies have transformed over the years from policies directed at removing urban blight through demolition and reconstruction to policies focused on upgrading and enhancing existing community infrastructure such as housing stock and entertainment outlets (Cho, Kim, Roberts, & Kim, Citation2010). Quality of life and a sense of place are quickly becoming the core touchstone in economic development programs, for creating urban spaces that are cleaner, well-lit and closer to public transits, and employment cluster is a combination that appeals to a changing demographic (Reilly & Renski, Citation2008). As urban planning continues to play an increasing role in mediating the needs of those who migrate to urban settings, it is important to note the challenges that have not yet been fully resolved, specifically, the dilemma of affordability for those who currently inhabit this space (Zukin, Citation2015).

While literature indicates trends toward reclaiming the city as a desirable locale, it also shows the growing complexity facing those who live through this transition. It is true that since the 1960s, city planners have taken a more socially conscious approach to address inequities (Jacobs & Paulsen, Citation2009; Von Hoffman, Citation2009); yet, in many instances, this approach yielded to the economics of supply and demand. Housing does not stand alone in this fight; local business owners are also at the mercy of urban development, where economic development takes precedence over neighborhood preservation. Community well-being have been disconnected from urban and economic development and planning (Liu et al., Citation2014). In transitioning areas, gentrified retail spaces tend to become only affordable to big businesses. Literature on revitalization shows that there is a logical connection between the tools of economic development such as BIDs and neighborhoods transformation. However, literature also shows that fiscal challenges in dilapidated areas necessitate the use of these tools, which can affect residents who are already vulnerable to the whims of economic turbulence.

2.2. Business improvement districts and revitalization in NYC

Ultimately, most urban renewal initiatives are funded by either federal or local government or both. As a modern approach, local governments have adopted another economic development tool known as BID. The development of BIDs attracted many new businesses, residents and investors into struggling neighborhoods to enhance the economic well-being of the district. Although BIDs are not primarily funded by the government or urban renewal policies (though they can apply and receive grants from governments), they have goals similar to urban renewal programs. BIDs services are generally—in addition to those already offered by the local government—limited to sanitation, maintenance, security, promotions and special events (Briffault, Citation1999). These services are geared toward enticing current and new shoppers to the district. The funds collected from the assessments are funneled toward the above-mentioned services and a BID’s operating costs. The main purpose of BIDs was to make commercial retail corridors in urban or downtown communities attractive so as to compete with suburban shopping centers such as “malls, office parks, and non-urban commercial centers” (Briffault, Citation1999, p. 370). In theory, BIDs seek only to make improvements in the designated areas which can bring about many benefits to a community, in reality; however, BIDs create unintended or intended impacts that are often omitted from the conversation about BIDs as a policy tool.

Various scholars have linked urban redevelopment to commercial gentrification. Ferm (Citation2016) identified commercial gentrification as the process of low-value small businesses being displaced during the reinvention of neighborhoods by higher or more competitive businesses and/or a more profitable residential property. Wang (Citation2011) argued that “the formation of gentrified neighborhoods is now usually associated with the redevelopment of old neighborhoods into upscale real estate, involving the forced relocation of existing residents” (p. 364). Hyra (Citation2012) further associated gentrification with the migration of minority groups during the renewal and gentrification process. Using Brooklyn and Harlem as examples of the displacement of minority residents and business owners after urban renewal process, Hyra (Citation2012) noted the increase in “forcing the displacement of several longstanding mom and pop black-owned businesses” (p. 500).

The New York City Council consistently works alongside New York City Planning officials to develop new zoning plans for neighborhoods across the city. There are currently many zoning plans at work for communities such as Canarsie, Red Hook and Sheepsheadbay, all of which are located in the borough of Brooklyn. The City Council has recently approved rezoning (to mean revitalization plan) for East New York, Brooklyn. The new East New York neighborhood plan promises to provide economic development through affordable housing, safer streets for pedestrians and beatification (NYC.gov, Citation2016). The plan for rezoning East New York appears to be exceptional in that the city will beautify the area by fixing streets, adding more parks, and will also create a new and more profound commercial area that will bolster the local job market. However, in the near future, small businesses and low-income residents are likely to face higher rental rates. One can assume that this commercial area is an example of where a BID might form, resulting in more neighborhood upgrades. As hard as planners work to realize these kinds of benefits for neighborhoods, the burden on residents and small businesses are all too common reality. While all these upgrades sound remarkable for investors and big business owners, examples of such rezoning-fueled transformation are visible today in Dumbo and Williamsburg in Brooklyn. Both of these neighborhoods were formerly home to low-income residents and small businesses, but they are now both considered among the most expensive neighborhoods in Brooklyn (Silver, Citation2010).

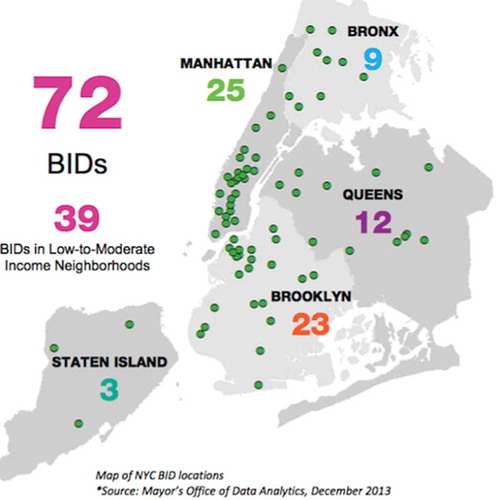

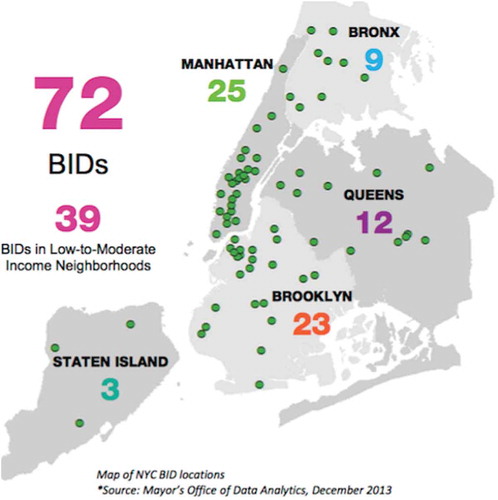

The context of this case study shows that using BIDs as an economic development tool or urban renewal policy can invariably affect residential and commercial rent, along with real estate value in proximity to the BID locale. Economic development tools are designed to promote financial solidity and reduce the blight of poverty and economic frailty (Gross, Citation2005). This case study explores and documents the process through which BIDs transform an area while leaving behind negative intended or unintended consequences. Figure shows the locations of all BIDS in NYC five boroughs, with 23 in Brooklyn (the map predates the addition of two BIDs in Brooklyn in the past three years). As appears in the map most of these districts are either in and around the downtown area..

3. Methodology

3.1. Research context

According to U.S. Small Business Administration (Citation2018), there are 29.6 million small businesses (99.9 of US businesses) in the United States with 57.9 million workers (47.8 of US employees). Oftentimes, it is unclear what is considered small business because the definition of a small business is ever changing (Anastasia, Citation2015). The small business administration recently defined small business as “if it qualifies for government contracts” (p. 90). The North American Industry Classification System indicates that a business is considered small if the company has less than 500 employees. Previous definitions have determined a small business as being economically disadvantaged and having an income under $21.5 million for service and manufacturing. In 2012, over 28 million small businesses accounted for half of the US workforce while contributing to an average of 60% of all new jobs (Anastasia, Citation2015). The discrepancy in how small businesses are defined explains the rampant inconsistencies in statistics about their numbers and size. Regardless of their numbers and how they are defined, small businesses contribute to employment and economic growth, yet their sustainability can be impacted by the economic development and policies implemented in cities.

By the end of 2017, NYC. Gov (Citation2018) Office of Mayor (2017) reported that “there are more than 220,000 small businesses rooted in local neighborhoods across the five boroughs, employing more than half of New York City residents” (p. 1). It is unknown how many of the small businesses are located in Brooklyn, what is known, however, is that they do face varying degrees of challenges across New York City. In certain areas, they are not generating enough sales due to the lack of foot traffics while in certain areas they cannot afford to pay the increasing commercial rent (WNYC, Citation2018). BIDs are primarily conceived to help small businesses thrive as part of an urban renewal package. The irony is that while BIDs can be useful in improving the physical appearance of an area, attracting new businesses and increasing foot traffic and consequently sales, they can also be counterproductive by contributing to fast appreciation in real estate value and complete transformation of a neighborhood. These changes not only affect renters and home owners in the BIDs areas, but eventually they affect the very businesses that they were intended to help.

To examine the impacts of BIDs (immediate, intermediate and long-term) on neighborhoods, 16 neighborhoods in Brooklyn were used to form a case study. The borough of Brooklyn was chosen because it is one of the fastest growing and most sought after locales to live in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. However, the boom in rental, mixed use and commercial developments are a telling sign of the contextual issues pertaining to housing availability and affordability for those who become marginalized and often displaced during economic urban development (Bagli, Citation2016).

3.2. Research design

BIDs as a policy tool have been shown to revitalize and transform neighborhoods, but not much understood about the process through which they do so from the perspectives of the very people who come in contact with their effects. Because not much has been done to tell the story about BIDs through the eyes of those who are affected by the produced changes, this exploratory study intends to systematically document the perspectives of BIDs directors, small business owners and resident in BIDs districts. As such, the study uses a qualitative method to serve the purpose of exploring undiscovered aspects of BIDs.

Qualitative research design is known to be useful in providing insights into the phenomenon that is not well studied before, especially when quantitative methods are not known or expected to be effective, mainly when the subject pertains to understanding or evaluating a process (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008). Additionally, Yin (Citation2003) suggested that a qualitative methods should be considered when (a) the objective of the study is to answer “how” and “why” questions; (b) a researcher cannot control the behavior of subjects or participants; (c) a researcher cannot separate the contextual conditions from the phenomenon under study because they are relevant; or (d) the boundaries are not clear between the phenomenon and context. Moreover, qualitative methods are more useful in developing a deeper understanding of a new phenomenon or for clarifying the subject matter for future investigation. Since all these conditions are strongly applicable and relevant in the context of this research, then using a qualitative case study was conceived of as a suitable research design to unravel, identify and document any recurring themes or patterns in order to draw general understanding of BIDs impacts on neighborhoods through the eyes of the stakeholders. Additionally, the rationale for using qualitative case study was based on a belief that numerical tables of rental rates in BIDs district would not tell us more than what already know about the continuous increase in residential and commercial rents. More importantly, increase in rental rates cannot be attributed to BIDs alone by any means for rent continues to increase annually in the entire borough of Brooklyn. Consequently, the use of qualitative methods made it possible to deeply understand the experiences of BIDs directors, small business owners and residents and this is where the study contributes to the literature on BIDs by adding nuances that go beyond the celebratory tone that hail BIDs as the savior of stagnant urban centers.

3.3. Population and sample

The participants in this study were stakeholders from neighborhoods in the borough of Brooklyn, NY. A convenience snowballing sample was used to reach out to residents, business owners and BIDs directors as key informants because of the time and cost constraints. Also, before electing to use a convenient sample, we distributed a self-administered questionnaire in two areas as way to test what data collection method will work and we failed to gather any valuable or useable information. Through snowballing and referral, we invited whoever made themselves available to our calls and emails to participate. The particular BID communities (shown in Table ) were also chosen based on the availability of participants who agreed to talk to us. We contacted BID directors, residents and business owners within specified BID district, and we asked a few select open-ended questions to obtain a full description of participants’ experiences within their BID district. Our hope was that a mixed sample of residents, business owners and key informants would be sufficient not only to provide enough information for the exploratory phase of the study but also to represent diverse views of various stakeholders in BIDs areas. Out of the 23 BIDs districts in Brooklyn, the sample included a total of 48 participants, 16 of whom were key informants (BIDs directors) and the remaining 32 were residents and business owners. Table provides a list of all the BIDs in Brooklyn, including the 16 districts used in this study.

Table 1. BIDs in Brooklyn 16 (samples) on the left

Table 2. Qualitative data analysis

3.4. Data: sources, collection and processing

In order to answer our research question, we relied on two sources of data. First, the secondary data came from the surveyed literature as well as analysis of texts, reports and documents about BIDs provided by community boards no 2. The second source of data is the primary data which we collected through interviews (in person and over the phone). We decided to use interviews because they allowed for the most efficient use of time and for follow-up questions. As mentioned earlier, we tried unsuccessfully to use a questionnaire. Also, after we consulted with our participants, it became clear to us that using focus group discussion was not possible due to difficulties to coordinate meeting time for different individuals.

After obtaining the human subject approval and all relevant materials, we conducted interviews with the participants who agreed to talk to us. Interviews were conducted during 2016–2017 in 16 of Brooklyn’s 23 BIDs districts as shown in Table . The data collected were first recorded, transcribed and then checked for validity by comparing responses from other participants. The transcribed data was then coded based on a priori codes developed from the research question and then based on emerging themes. These codes were then further collapsed into broader categories. These categories were then arranged into themes, which were used to produce accounts. We used these accounts to develop our arguments during interpretation which appear in discussion and conclusion. The priori codes, categories and themes revolved around conversations surrounding BIDs impact as the process for transforming areas through immediate, intermediate and long-term impacts. Each theme covers aspects of BIDs’ roles and impacts. For example, asking if informants think a specific instance of rent increase could be linked to the effect of BIDs. After that, recurring themes and patterns were identified by tabulating data in a similar table to generate accounts. Finally, after all data was synthesized, analyzed and organized by categories, generalized conclusions were drawn from the analysis. The results and findings are reported in a summarized table highlighting the process of transformation in BIDS areas.

3.5. Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis involves nine successive steps: data, finding a focus, managing data, reading and annotating, categorizing data, linking data, connecting categories, corroborating evidence, and producing an account (Dey, Citation1993).) These steps can broadly be divided into two stages: de-contextualization and contextualization. According to Tesch (Citation2013), during de-contextualization, fragmented pieces of data can stand alone. Primarily, contextualization depends upon a systematic process of data interpretation during which overall themes and organizing principles can be identified whereby producing themes is similar to producing an account. Steps such as finding a focus, managing data, reading and annotating, and categorizing data can be considered as part of the de-contextualization stage, which produces fragmented pieces of data that can stand alone. This is what reports about BIDs represent; each report makes sense on its own but it does not paint a general picture about how the stakeholders (participants) view the process. On the contrary, linking data, connecting categories, corroborating evidence and producing an account constitute the contextualization stage. This stage requires a process through which linkages and connections are created. In a way, the de-contextualization stage resonates with what Wolcott (Citation2009) calls the description stage, in which data speaks for itself. Starting with priori codes derived from the surveyed literature and research question, using actual quotes from participants, Table presents the process we used for data analysis and organization beginning with coding to generating accounts to making interpretations.

4. Findings

In the beginning, we asked about the ways in which BIDs influence (in terms of rental rates and prices) the experiences of business owners, renters and potential homebuyers in Brooklyn. Answering the questions paints a picture of BIDs’ impacts (immediate, intermediate, long-term/lasting) on neighborhoods through the eyes and lived experiences of the stakeholders who are affected the most by such transformation. The findings of this research are based on what we recorded through interviews and observations.

4.1. Immediate impacts

It is shown that one of the primary roles for BIDs is to collect taxes to be used in improving the physical appearance and safety of the area. Initially, we assumed that BIDs can change the area in a short period of time in terms of cleanliness and physical appearance. The findings presented in Table support most of what we assumed. However, it is important to note that some of the inquiries were initially met with resistance, because of an assumption that a negative response was elicited, but we also experienced very informed conversations. The findings in Table are presented through direct quotes from the participants. The percentage on the right column indicate the number of participants who agreed with the assertion indicated in the code.

Table 3. BIDs immediate impacts (N = 32)

4.2. Intermediate impacts

As BIDs is instituted, the physical appearance of the area improves and the rental rates (commercial and residential) start to rise, soon after the real estate value begins to appreciate faster. An increase in the real estate value means an increase in property taxes, which will immediately be accompanied by additional increase in commercial rent and residential rent. In addition to increase in property taxes, a high demand on the area also lead to continuous rise in commercial and residential rental rates. As BIDs areas are redeveloped, they are likely to be sought after. Yet, the relationship between BIDs and increase in rental rates has been nothing but anecdotal because there are other situational and contextual factors that can influence rental rates. It was also very difficult to quantify the exact impact of BIDs on any specific rent increase incident. In the eyes of participants in this study, the role of BIDs in driving rental rate is a reality of everyday life. One BIDs director puts it this way:

There is no doubt in my mind that the physical improvements brought to the area by BIDs have contributed to this spike in rental rates. Here is how I witnessed it firsthand in Atlantic Barclays area. As soon as they announced the plan to build the sport complex, before even the construction has begun, real estate agent were running around trying to put their hand on any property sooner than later. Everybody knew that this area will be super expensive. Soon enough, the area cleaned up, people were enticed by the big money and new mixed used buildings started to dominate the landscape. Immediately, the place that used to rent for $1,400 went for $2,400. Now you can imagine the commercial rent and the value of homes in the area.

Along time resident of Metrotech area, went even further and lamented that

What really drives me crazy is that most of this construction is for investment and it is not going to provide more supply so that rent will go down or remain the same. It is insane that while there are new buildings (presumably new supply) the rent continues to increase. I think I am blessed, I have an old rent, and I don’t know what young people do these days if studio in that building over there is going for $3,600. How much money do you have to make to be able to live there? And how many people do make that much?

A small business owner around Grand Street made the case in a point by stating that

In the beginning, we were told the additional fees we pay will help clean up the area, bring customers and increase our sales, little that we knew we might have shot ourselves in the foot. We paid for the cleanup and the place is becoming attractive now, but the rent is almost doubled. How can we do this to ourselves? The city keeps telling us that they understand that we are squeezed between a rock and hard place. Soon enough, many of us won’t be able to do business around here.

Another BIDs director went on to add that

The biggest challenge now for this area is the cost of entry, with the high risk of doing business to begin with, it seems that the cost to start in this district will increase the risk to three fold. Commercial rent is untouchable for small entrepreneurs. You need a lot of upfront cash and rent to start.

From the responses provided by renters, business owners and BIDs director, what seems to be emerging is that, without some sort of a relief in forms of affordable housing for renters and tax break for business owners, BIDs can be a double-edge sword. Table shows this irony as reflected in the responses of BIDs directors whose experiences in the BIDs leadership range from 4 to 14 years. Four questions were asked to speak to the intermediate impacts BIDs have on businesses.

Table 4. BIDs intermediate and long-term impacts directors responses (N = 16)

The main concern for both residential and business renters was the rising rental rates. It was evident that rent was increasing in most BID neighborhoods in Brooklyn and was likely to continue to increase. This was the main concern of business owners, fearing that increasing the rent would cause them to have to close their businesses or relocate. In addition to rising rents, lack of a comprehensive knowledge about city rules and ordinances was also a big concern for property owners. Violations and fines received by business owners added to their cost of conducting business and took time out of their schedules when having to attend hearings and adjudications. BIDs directors worked hard to assist both business and property owners with these challenges. For instance, business owners and BID directors looked at how BIDs could provide instructions on how owners can get grants from small business services. Another example described was for residents in BID neighborhoods, looking to provide property owners with resources like supplemental funds and matching grants that would allow owners to upgrade their property, which would result in attracting more tenants.

4.3. Long-term/lasting impacts

When asked about the effect BIDs might have on rental rates, residents, business owners and BIDs directors unanimously agreed that BIDs have affected residential renters, small business owners and potential home buyers. However, many interviewees discussed the issue of adaptability, and how they felt businesses need to learn how to identify the changing characteristics of their neighborhoods, customer base and the products they sold. In the end being able to continuously adapt to the changes in neighborhoods is important. One business owner stated that “[i]t is very difficult and expensive to start up a business and sustain it now.” Another business owner went on to add that “[t]axes are very high now. It is almost impossible to make profit as we used to and I wonder for how long many of us can remain open”. Counter to what BIDs initially hope to do in helping small businesses, a business owner boldly stated that “Mom and Pop stores are being pushed out, they can’t keep up with the costs of doing business and they definitely cannot compete with big businesses”.

Moreover, when we asked about whether any specific group might be more positively or negatively affected by the presence of a BID, responders noted that everyone in the community was somehow affected in a way. Business owners, property owners, customers and visitors were affected by the changes BIDs created in those neighborhoods. One frustrated resident stated that

I actually didn’t know anything about BIDs before I talked to you. I thought Crown Heights as a place is just being gentrified like Williamsburg and DUMBO. I guess I didn’t know the mechanics of the process, but I know when I see these fancy cafes coming to a neighborhood then other fancy restaurant will follow and soon enough the place will change and the culture will change because it is all new faces now. We used to play music in the streets and know our neighbors. This place has completely changed and it is already expanding to Lefferts Garden and Flatbush.

It is not uncommon to encounter people who have not heard about BIDs, especially renters. As for how to mitigate the impacts on small businesses, key informants noted that it was very important for BIDs to educate property owners and business owners on how to serve changing neighborhoods. One perceptive BIDs director told us that

People are angry and they think there is away for this process to be slowed or reversed. This is true about renting residents and affected business owners. The reality is that BIDs are small cog in a big machine, the entire Borough of Brooklyn has become the go-to place since the economic recession. With new influx of people going to one place, there will be fast and often drastic changes. BIDs were an attempt to help businesses to compete and thrive, but now the challenge is to survive in a very demanding environment.

Finally, when asked about the future outlooks of BIDs, key informants indicated that as long as BIDs stay focused on their mission, such as keeping neighborhoods safe, then they are going to keep attracting people while making communities better. A business owner reported that

Rental rates are high in and around Atlantic and even in areas where it used to be cheap, but because prices here drove so many business to nearby areas, the demand is higher now and the rent is going up in the entire surround area. Unless you move your business to a place that is far from here it will be really hard to afford to stay open.

As for the cultural transformation, one resident lamented that “there are cultural changes happening in the downtown areas.” Another renting resident stated that “some residents can’t afford to stay here and have to relocate.” In these previous quotes and comments, one can clearly infer that the long-term impacts are becoming lasting impacts. The area is now completely transformed while the real estate value continues to appreciate driving rental rates even higher. Such changes in one area will soon spill over and have similar effect in contiguous neighborhoods

5. Discussion

In an effort to stimulate the economy in the urban communities, BIDs have been used to boost spending by making urban commercial districts more inviting to consumers who typically shop in suburban or mall settings. As we have seen so far, BIDs do in fact attract consumers and increase sales for businesses but they also can be a vehicle for complete transformation of a neighborhood. In this study, we aimed to draw a picture about the process through which BIDs do change and transform urban landscape through the eyes of renters, small business owners and BIDs directors. The reality is that BIDs as a policy initiative are implemented in a context that is marred by very deep controversies about government’s intentions. Historically, urban communities were often identified as problematic areas for the government to revitalize. These neighborhoods are defined by the federal government as “blighted neighborhoods” (Dickerson, Citation2016, p. 978ik) with low or sinking property values. Robick (Citation2011) contended that urban neighborhoods tend to be populated by low-income, minority families. In the past, urban renewal polices produced fear of displacement and created anxiety around the need to have to relocate elsewhere. Old or new, urban renewal is an economic tool for the government to utilize potential neighborhoods and to enhance economic growth. Thus far, the debate surrounding urban revitalization often times is centered on property rights of elite who occupy higher socioeconomic order rather than the economic development of a particular landscape. Development then becomes more than just a conversation about market and/or government policy surrounding fiscal growth and preservation, it rather should include the importance of protecting the rights of non-owning residents, owning residents, renters, business owners and developers.

Gentrification, as a by-product of urban renewal policies, then becomes all but inevitable outcome. Many neighborhoods in New York City have already gone through socio-demographic transformations. Arguably, gentrification can be seen as beneficial to residents in urban communities by bringing in new housing developments, additional retail and cultural services which could create more local jobs. Notwithstanding the positive attributes of gentrifications, the low-income minority groups are likely to suffer or be displaced (Freeman & Braconi, Citation2004). Similar to former studies, responses from participants indicated that improvement in a neighborhood cause hyperinflation of rent and real estate prices (Godbey, Citation2008) and this is exactly why BIDs becomes a vital tool with intended and unintended outcomes.

5.1. Intended or unintended outcomes

It is arguable that the immediate impacts such as improvement in physical appearance, cleanliness and increase foot traffic can be viewed as intended positive outcomes. Practically, what might be even more challenging is to argue that even what might be perceived as negative outcomes such as the increase in residential and commercial rent as well as increase real estate value are in fact negative at all. The complexity of the matter originates in the rational choice dilemma as a tool for policymaking. This is to ask whose interests the policy serves. Increase in property value is good for homeowners and for government (higher property tax), but could be bad for renters and small business owners. The same logic can be extended to long-term impacts as well as the lasting impacts. Again, cleaner neighborhood with higher property value spilling over to nearby areas will lead to cleaner areas with higher property value and taxes. In this aspect, BIDs share the fundamental underpinnings of any given public policy, who gets what when and how, which comes with unequal distribution of benefits and burdens. In nutshell, all the changes brought about by BIDs can be seen as intended outcomes despite the fact that they affect certain groups negatively. When a neighborhood improves, the benefits go to the city, homeowners and real estate businesses and to some extent small businesses, but the burden is shouldered by low-income residents and to some degree small businesses. Figure shows the role BIDs play in the process of neighborhood transformation. A struggling area is rezoned and then opened for business. BIDs are then introduced. Immediately, the physical appearance of the place improves and then more businesses come in which bring more consumers to the area, leading to more sales. Soon after, the real estate value appreciates faster while commercial and residential rents start to increase. As a result, both low-income residents and small business owners struggle and may slowly be forced out of that area. Big businesses and new residents with higher income start to move in, the real estate value continues to appreciate even faster and both commercial and residential rents continue to rise. Not long after, the place is completely transformed physically, socially, culturally and economically. Such changes will soon spill over to the adjacent areas because of dynamo effect.

Reponses from participants have indicated that there is a correlation between BIDs and the intermediate and long-term impacts. An example of this can be seen in the lived experiences of small businesses as they are being squeezed out because rental rates continue to rise dramatically over a short period of time, which can favor larger businesses and chain stores because they have the economics of scale to absorb the high entry cost. Small business owners like mom and pop shops were left at a greater disadvantage in the BIDs districts. The primary concern of most BID directors is that residential and commercial rent increases are likely to continue in the future.

Interpretations of the study’s findings point to the reality that there were other issues facing renters and property owners such as the increase in property taxes. Increasing property tax adds to the expenses of owning a property and contributes to the increase of rents for tenants of commercial and residential spaces. Other challenges that emerged during the interviews were issues pertaining to adaptability for business owners. These include change in economy, specifically technological changes, the decrease in foot traffic, and the increase of e-commerce. Another issue facing store owners was new and inventive ways to market their businesses in BID districts. Furthermore, the responses indicated that BID directors were aware of these challenges and have sought solutions for their communities. They saw their role emerging from administrators to advocates in order to meet the needs of those who were affected by these negative changes. Education about how businesses and owners could plan more strategically seemed to be a priority for many directors. Lastly, creating a way to communicate to the city, and advocate for better tax relief programs for property and business owners alike was a very important point of discussion. In the end, what the BIDs directors wanted for BIDs was likely to mitigate the negative impacts that BIDs bring about.

6. Conclusion

For more than 30 years, BIDs have been used as an economic development tool for the promotion and development of struggling to potential areas, usually downtown areas. The problem, however, as we have seen, is that while BIDs have well-intentioned goals, they have the potential of transforming the entire area through fast appreciation of real estate value. The experiences shared by participants and key informants indicated that BIDs, as a policy tool, are capable of revitalizing a neighborhood as intended while also creating unwanted outcomes resulting from unequal distribution of benefits and burden. While homeowners and government gain more, low-resident and small businesses may face displacement. The findings of this research supported our initial assumptions that BIDs can be a vital policy tool, albeit, leaving negative impacts on certain groups.

Previous study have shown that BIDs can be a useful economic development tool if we conceive of development in terms of economic growth from policymakers’ perspectives. There was little known however about stakeholders’ perceptions about the role BIDs can play in bringing about economic development as well as increasing property value and consequently rental rates. This study has generated new insights by adding new nuances to the complex nature of the debates surrounding BIDs as an urban renewal policy. Findings from this research indicated that like other public policies, BIDs creates the dilemma of whose interests should be prioritized and whose perspectives should be used to determine whether BIDs leave negative impacts on urban landscape by acting as a vehicle for gentrification. This study has outlined and discussed the process through which BIDs can completely transform a neighborhood beginning with immediate impacts (improved physical appearance) and ending with lasting impacts whereby the area has become an expensive high-end area with mixed-used building occupying the urban landscape. Generally, research on BIDs has focused on their vitality as an economic development tool, but largely ignored the perspectives of business owners, residential tenants, and BIDs directors. Previous studies failed to acknowledge the perspectives of these groups. If BIDs are the necessary evil, then this study shows that debate on BIDs ought to go beyond their celebrated role as an economic revitalization tool.

The rising concerns emerged from this study is the impact of BIDs on renters, owners and future homebuyers. As such, understanding the importance of policy implications could further assist in the success of these neighborhoods. New policies should be introduced to alleviate financial burdens for businesses and property owners. For instance, raising taxes could be extended to five years rather than on an annual basis. This could give residents and new businesses time to adapt to changes. To alleviate these sudden and new changes, small business owners should be granted additional tax deductions to help them stay in business or be eligible for grant subsidies to offset rising operational costs in utilities and marketing. Policy implementation should remain flexible enough to accommodate all parties that are affected by these changes. To do so, it is imperative to understand the negative impacts on certain groups. Perhaps, commercial developers should be incentivized to build a minimum number of affordable housing units to house lower-income populations in the BIDs district. For future research, scholars should seek to study the long-term economic and social effects of BIDs on communities. In essence, are BIDs as a policy tool a new name for gentrifying efforts? Engaging in this endeavor can help enhance our understanding of BIDs and their impacts on individuals and communities.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bakry Elmedni

Bakry Elmedni, Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Master of Public Administration MPA Program, School of Business, Public Administration and Information Sciences, LIU Brooklyn. Broadly, Dr Elmedni’s research centers on the role of leadership and governance in promoting social equity and organizational efficacy. This research on business improvement district (BIDs) connects to other two major areas of his research: one is the choice of BIDs as a policy tool for stimulating economic development and the other is the impact such policy on housing options for low-income residents.

Nicole Christian

Nicole Christian, MPA, is an adjunct assistant professor in the MPA Program at the School of Business, Public Administration and Information Sciences at LIU Brooklyn. She currently works as a consultant to non-profit organizations in the greater New York area.

Crystal Stone

Crystal Stone, MPA. Completed a Master of Public Administration (MPA) at the School of Business, Public Administration and Information Sciences at LIU Brooklyn. She currently works for a non-profit sector NYC.

References

- Anastasia, C. (2015). Exploring definitions of small business and why it is so difficult. Journal of Management Policy and Practice, 16(4), 88–99. Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/1762038319?accountid=27899

- Bagli, C. V. (2016, August 29). ‘The market is saturated’: Brooklyn’s rental boom may turn into a glut. Retrieved November 17, 2016, from http:nyti.ms/2bVPGXW

- Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(14), 544–559.

- Briffault, R. (1999). A government for our time? Business improvement districts and urban governance. Columbia Law Review, 99(2), 365–477. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org.liucat.lib.liu.edu/stable/1123583

- Campagna, J. (2016). Zoning and incentives for promoting retail diversity and preserving neighborhood character. Retrieved from http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/MeetingDetail.aspx?ID=503474&GUID=43FCFF2A-BA0F-4936-8493-3B2636093D1F&Search=

- Cho, S., Kim, J., Roberts, R. K., & Kim, S. G. (2010). Neighborhood spillover effects between rezoning and housing price. The Annals of Regional Science, 48(1), 301–319. doi:10.1007/s00168-010-0401-9

- Dey, I. (1993). Qualitative Data Analysis. NY, NYC: Routledge.

- Dickerson, A. M. (2016). Revitalizing urban cities: Linking the past to the present. The University of Memphis Law Review, 46(4), 973–1008. Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/1804847012?accountid=27899

- Elstein, A. (2016, September 18). Shaping a neighborhood’s destiny from the shadows. Business improvement districts were created to rescue a dirty, crime-ridden city. With order restored, some say it's time to bid them goodbye. Retrieved from http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20160918/REAL_ESTATE/160919896/clean-operators-or-shadow-governments-critics-of-bids-say-its-time-to-bid-adieu-to-citys-business-improvement-districts-like-the-bryant-park-restoration-corp-and-alliance-for-downtown-new-york-that-have-become-big-business

- Elwell, C. K. (2013). Economic recovery: sustaining U.S. economic growth in a post- crisis economy*. Current Politics and Economics of the United States, Canada and Mexico, 15(3), 369–404. Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/1622681224?accountid=12142

- Feldman, M., Hadjmichael, T., Lanahan, L., & Kemenny, T. (2016). The logic of economic develoment: A defintion nd model investment. Environmental Planning C: Politics and Space, 34(1), 5-21. doi:org/10.1177%2F0263774X5614653

- Ferm, J. (2016). Preventing the displacement of small businesses through commercial gentrification: Are affordable workspace policies the solution? Planning Practice & Research, 31(4), 402–419. doi:10.1080/02697459.2016.1198546

- Freeman, L., & Braconi, F. (2004). Gentrification and displacement: New York city in the 1990s. American Planning Association. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(1), 39–52. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/229657239?accountid=27899

- Godbey, M. (2008). Gentrification, authenticity and white middle-class identity in jonathanlethem’s the fortress of solitude. The Arizona Quarterly, 64(1), 131–151,153. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/199348098?accountid=27899

- Gross, J. S. (2005). Business improvement districts in New York City’s low-income and high-income neighborhoods. Economic Development Quarterly, 19(2), 174–189. Retrieved from http://0search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/215397715?accountid=12142

- Hamnett & Whitelegg. (2006). Loft conversion and gentrification in London: From industrial to postindustrial land use. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 9(1), 106–124. doi:10.1068/a38474

- Hipler, H. M. (2007). Economic redevelopment of small-city downtowns: options and considerations for the practitioner: Part 2. Florida Bar Journal, 81(2), 40–43.

- Hyra, D. S. (2012). Conceptualizing the new urban renewal comparing the past to the present. Urban Affairs Review, 48(4), 498–527. doi:10.1177/1078087411434905

- Jacobs, H. M., & Paulsen, K. (2009). Property rights: The neglected theme of 20th-century american planning. American Planning Association. Journal of the American Planning Association, 75(2), 134–143. Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/229633675?accountid=12142

- Johnson, B. E., & Shifferd, J. (2016). Who lives where: A comprehensive population taxonomy of cities, suburbs, exurbs, and rural areas in the united states. The Geographical Bulletin, 57(1), 25–40. Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/1785518397?accountid=12142

- Lin, J., & Long, L. (2008). What neighborhood are you in? Empirical findings of relationships between household travel and neighborhood characteristics. Transportation, 35(6), 739–758. doi:10.1007/s11116-008-9167-7

- Liu, C. Y., Miller, J., & Wang, Q. (2014). Ethnic enterprises and community development. GeoJournal, 79(5), 565–576. doi:10.1007/s10708-013-9513-y

- Micklow, A. C., & Warner, M. E. (2014). Not your mother’s suburb: Remaking communities for a more diverse population. The Urban Lawyer, 46(4), 729–739,741–751. Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/1728147836?accountid=12142

- Nelson, A. C., & Malizia, E. (2006). planning leadership in a new era. Journal of the American Planning Association, 72(4), 393–409. Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/229620546?accountid=12142

- NYC. Gov (2018) Office of Mayor. 2017 Small business progress report. Retrieved from http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/sbs/downloads/pdf/about/reports/smallbizreport-2017.pdf

- NYC.gov (2016). East New York Neighborhood Plan. Retrieved from http://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/plans/east-new-york/east-new-york-1.page

- Porter, J. R., & Howell, F. M. (2009). On the ‘urbanness’ of metropolitan areas: Testing the homogeneity assumption, 19702000. Population Research and Policy Review, 28(5), 589–613. doi:10.1007/s11113-008-9121-6

- Reilly, C. J., & Renski, H. (2008). Place and Prosperity: Quality of Place as an Economic Driver. Maine Policy Review, 17(1), 12–25. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mpr/vol17/iss1/5 Retrieved from http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20160918/REAL_ESTATE/160919896/cl ean-operators-or-shadow-governments-critics-of-bids-say-its-time-to-bid-adieu-to-citys-business-improvement-districts-like-the-bryant-park-restoration-corp-and-alliance-for-downtown-new-york-that-have-become-big-business.

- Robick, B. D. (2011). Blight: The development of a contested concept (Order No. 3452459). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (864740266). Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/864740266?accountid=27899

- Seidman, L. S. (2012). Keynesian fiscal stimulus: What have we learned from the great recession? Bus Econ Business Economics, 47(4), 273–284. doi:10.1057/be.2012.25

- Silver, N. (2010). The most livable neighborhoods in New York. New York, 32–43. Retrieved from http://0search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/205162515?accountid=27899

- Tesch, R. (2013). Qualitative research: analysis types and software tools. NY, NYC: Routledge.

- U.S. Small Business Administration (2018). Small business profile. Retrieved from https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/All_States.pdf

- Von Hoffman, A. (2009). Housing and planning: A century of social reform and local power. American Planning Association. Journal of the American Planning Association, 75(2), 231–244. Retrieved from http://0search.proquest.com.liucat.lib.liu.edu/docview/229652889?accountid=12142

- Wang, S. W. (2011). Commercial gentrification and entrepreneurial governance in Shanghai: A case study of Taikang road creative cluster. Urban Policy & Research, 29(4), 363–380. doi:10.1080/08111146.2011.598226

- WNYC (2018) Retrieved from https://www.wnyc.org/

- Wolcott, H. E. (2009). Writing up qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications, Inc.

- Wu, F. (2015). State dominance in urban redevelopment: Beyond gentrification in urban China. Urban Affairs Review, 52, 631–658. doi:10.1177/1078087415612930

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Zukin, S. (2015). Cited in Beaur Bryce (2015), Sharon Zukin: Built for humans: The sociologist on the role of the artist in gentrification, challenges to affordable housing, and the commodification of New York City’s loft lifestyle. Retrieved from https://www.guernicamag.com/built-for-humans/