Abstract

This study examines how a psychometric testing tool can be used to explain, predict and measure behavioural competences and how entrepreneurs fund the firm. Reference is made to studies of personality traits. More recent studies have called for research into behaviour and competences and specifically in the finance context of orchestration of resources.

The authors take a pragmatic realism perspective using a mixed method study to explore the “reality” of the entrepreneur. Cluster analysis is used to identify the relationship between behavioural competences and funding outcomes.

Applying Big 5 Theory of Personality and the Great 8 Competences indicates how behaviour impacts outcomes as entrepreneurs seek to access finance. The identification of three distinct groups in this longitudinal study means belonging to one of these groups predicts likely behaviour when searching for finance.

A strong behavioural characteristic which emerged, validated through interviews and psychometric testing, was an orientation towards engagement and working with other organisations. In a funding context, this manifested itself in using networks, seeking advice and sharing equity. These co-operative, collaborative characteristics are different to the classic image of the entrepreneur as a risk-taker or extrovert.

The study identifies entrepreneurs who are both successful and unsuccessful in finance applications and compares behavioural competency profiles, thus overcoming the limitations of many studies that are biased towards successful enterprises.

Public Interest Statement

It is difficult for financial institutions to determine the future viability of a business based purely on collateral and track record, resulting in potentially viable young businesses being denied access to growth capital. The 2004 Graham Review (HMT, 2004) concluded that even with new credit scoring techniques, the problems associated with asymmetric information remain.

This research provides a methodology which enables the identification of competences which overcome some of the difficulties caused by information asymmetry between stakeholders. Financial Institutions, Business Angels and Accelerator Programmes can use Competency data to differentiate between entrepreneurs and aid decision-making in the allocation of funding and other support.

1. Introduction

Behavioural competence is used as a lens through which the differences between entrepreneurs are identified and analysed, examining the impact this has on funding outcomes. A longitudinal methodology is adopted to examine how entrepreneurial behaviour influences funding outcomes of the firm.

Despite numerous Government initiatives, net lending to businesses has continued to fall, and schemes to encourage lending have made little difference (BOE, Citation2014). Indeed, “the funding gap has increased exponentially since onset of the financial crisis” (Jones & Jayawarna, Citation2012). Supply side problems have been exacerbated by banks rebuilding their capital base, becoming more risk averse and being unable to resume adequate lending to creditworthy businesses. Venture capital has also declined, as fund managers seek to carefully manage current investments.

Demand side factors have also had an impact on the flow of funds to small firms. The British Bankers Association commented “Every time that people read that banks aren’t lending, they don’t apply”, (Management Today, April 2013). This is consistent with the trend towards discouragement and the “rise of the non-seeker of advice” (SME Finance Monitor, Citation2013).

At the same time, there has been growth in more asset-based lending, and tax incentive schemes have made investments more efficient. This has resulted in the growth of business angel finance. There is also evidence that Peer-to-Peer funding models, now prevalent throughout the world, are beginning to develop in the UK through both debt and equity models.

In order to minimise the effect of situational conditions, the study focuses on a single sector—Creative Industries thus controlling for proximal explanations (Magnusson & Endler, Citation1977). This sector is growing at twice the rate of the rest of the economy and there is a greater reliance on equity finance. However, there is also a lack of data, a greater perception of risk, a lack of collateral and a concern amongst investors that entrepreneurs in this sector lack the commercial acumen to generate value within the venture (Deakins, North, Baldock, & Whittam, Citation2008).

Both demand and supply side factors have therefore resulted in fewer firms chasing diminished funding sources. Despite this environment, 28% of firms in the SME Finance Monitor (Citation2013) expected to try and raise finance and a further 17% were “would be,” and therefore wanted to raise finance if barriers could be removed. There is also evidence that Small Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) are increasingly prepared to consider alternative funding sources to the traditional types of equity and loans.

This research makes a contribution through the use of psychometric testing and measuring behavioural competences in entrepreneurs. It is a longitudinal study; three qualitative interviews are conducted over a 3-year period, identifying funding outcomes and behaviour associated with funding the small firm. The research makes a contribution through the confirmation that psychometric testing can be used to explain and predict how individuals finance the firm; what Wright and Stigliani (Citation2013) describes as resource orchestration.

2. Literature review

The study examines demand side market failure and considers the very different funding landscape faced by entrepreneurs following the banking crisis of 2008. The literature under review therefore considers funding factors, personality and entrepreneurial behaviour. It considers what individual entrepreneurs can “do” and why in order to access finance.

Many of the early studies in entrepreneurship were focused on what makes an entrepreneur (Baum & Locke, Citation2004; Baum & Silverman, Citation2004; Brockhaus, Citation1980; McClelland, Citation1961; Rauch & Frese, Citation2007; Sandberg & Hofer, Citation1987), and lacked definitive conclusions (Gartner, Citation1989). However, more recently, the debate has re-emerged in using personality traits as a means of predicting activity. The Five Factor Model, in particular, has been used to predict behaviour in the general work setting and Ciavarella (Citation2004) has identified this as a useful tool in the entrepreneurial context

More recently, there has been a call to look in more detail at behaviour and “what do entrepreneurs actually do” (Mueller, Volery, & von Siemens, Citation2012, p. 1; Bird, Schjoedt, & Baum, Citation2012). A number of studies have looked at entrepreneurial behaviour and it has been concluded that competences provides a potentially useful lens through which to frame these and other questions (Bridge, O’Neill, & Cromie, Citation1998; Burgoyne, Citation1993, Citation1989; Gherardi, Citation2003; Gruglis, Citation1997; Holton & Naquin, Citation2000; Sadler–Smith, Hampson, Chaston, & Badger, Citation2003).

The study of managerial behaviour has been described as “a missing field of research within the small business literature” and authors have highlighted the need for reliable measures (O’Gorman, Bourke, & Murray, Citation2005, p. 2; Bird et al., Citation2012). Wright and Stigliani (Citation2013) noted the need to examine in more detail how individual entrepreneurs arrive at the appropriate bundles of resources and capabilities to generate growth (Wright & Stigliani, Citation2013) and called for more “fine grained work” on how entrepreneurs influence outcomes (Wright & Stigliani, Citation2013, p.4). Other authors have called for an alternative paradigm (Bygrave & Timmons, Citation1992), involving more field studies and longitudinal research, and embracing the use of multi-dimensional approaches linked to the real working situation of the owner-manager (e.g. Caird, Citation1993; Gibb & Davies, Citation1990). McCarthy, Krueger, and Schoenecker (Citation1990), for example, called for more qualitative longitudinal studies to answer questions of how entrepreneurs leverage social networks in order to access funding sources (Brockhaus, Citation1980; Moran, Citation1998). Fraser (Citation2014) recognised a number of policy initiatives which could potentially allow entrepreneurs, who previously had been discouraged borrowers, to consider bank borrowing. These included more awareness of policy initiatives and better support for SMEs.

A number of studies have looked at entrepreneurial behaviour and it has been concluded that competences provide a potentially useful lens through which to frame these and other questions (Bridge et al., Citation1998; Burgoyne, Citation1993, Citation1989; Gherardi, Citation2003; Gruglis, Citation1997; Holton & Naquin, Citation2000; Sadler–Smith et al., Citation2003). Through better observations of behaviour, small business researchers can therefore make a distinctive contribution to the understanding of how small firms are managed and structured (Bird et al., Citation2012; Gartner, Bird, & Starr, Citation1992; Mueller et al., Citation2012; O’Gorman et al., Citation2005). This will provide a better understanding as to why some individuals are better than others at exploiting resources, in addition to providing more detail on measures and also more detail on entrepreneurial characteristics. Specifically in the context of finding finance, this study examines behaviour and how does individual resource orchestration arrive at the appropriate bundles of resources and capabilities to generate growth (Wright & Stigliani, Citation2013)?

In identifying these opportunities for future research, Bird et al. (Citation2012) noted the shortcomings in research into entrepreneurial behaviour, and called for future researchers to be more precise in their conceptualisation, and particularly, in their operationalisation of behaviour. Mueller et al. (Citation2012) also noted, with the exception of the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics, many studies build on self-reports, rely on vague behavioural constructs or capture only one behaviour at a time.

3. Theoretical background

In studies on how entrepreneurs develop capital structure for small firms, Pecking Order Theory and Funding Escalator models were used to identify how firms fund themselves as they grow (Myers, Citation1984). Changes in financial markets have resulted in academics re-examining these tools concluding that a definitive rationale for capital structure in small firms remains elusive. In addition, most research has failed to make use of the potential of inductive analysis to uncover what constitutes entrepreneurs’ behaviour in a holistic manner (Bird et al., Citation2012).

The development of the Big Five model of personality traits (Goldberg, Citation1990) has provided a commonly accepted taxonomy for classifying personality. The absence of an equivalent taxonomy for classifying performance constructs has been repeatedly identified as a barrier hindering a better understanding of the relationship between personality and performance.

Understanding causation, as in how and why things are related, is necessary for effective intervention in organisations and specifying causal pathways and models is a particular strength of psychology. Kurz and Bartram used the concept of behavioural competency to attempt to integrate diverse theories, concepts and measures into an overall model of individual performance.

Behavioural competency is defined as sets of behaviours that are instrumental in the delivery of desired results or outcomes. Woodruffe agrees with the definition that behavioural competency is the set of behaviour patterns that the incumbent needs to bring to a position in order to perform its tasks and functions.

These definitions represent a development from the trait-based approach of Boyatzis in his seminal book “The Competent Manager”, where job competency is defined as an underlying characteristic of a person which results in an effective and/or superior performance of a job.

So, a competency is not the behaviour or performance itself, but the repertoire of capabilities, activities, processes and responses available that enable a range of work demands to be met more effectively by some people than others. The main factor that distinguishes a competency from other weighted composites of psychological constructs is the fact that a competency is defined in relation to its significance for performance at work (Kurz and Bartram 2002).

There were therefore a number of attempts to define the competency concept further and to provide more “finely grained” constructs of competency. Tett and Burnett, for example, developed a taxonomy of 53 competencies clustered around nine general areas—task orientation, dependability, open-mindedness, emotional control, communication, developing self and others, occupational acumen and concerns.

Borman and Brush proposed a structure of 1987 behaviours mapping onto 18 dimensions, which in turn map onto four very general dimensions—leadership and supervision; interpersonal relations and communication; technical behaviours and the mechanics of management; and useful behaviours and skills.

Bartram (Citation2005) extended this further adopting a three-tiered structure; bottom tier consisted of 110 components, mapped onto a set of 20 competency dimensions (the middle tier) and this is then loaded onto eight broad competency factors.

The top tier is the Big Eight, and importantly, also provides a mechanism for mapping measures of disposition or attainment onto competencies, and a number of studies, including longitudinal studies, have provided further confirmation of the eight factor structure (Kurz and Bartram 2002).

The Great Eight competencies (Bartram, Citation2005) represent a set of factors that underpin job performance. These eight competencies include: leading and deciding; supporting and cooperating; interacting and presenting; analysing and interpreting; creating and conceptualising; organising and executing; adapting and coping; as well as enterprising and performing (see Bartram and SHL Group Citation2005; Kurz and Bartram 2002).

The entrepreneurial behaviour literature therefore calls for more research which is able to both identify behaviour as discrete units and also introduce some element of measurement (Bird et al., Citation2012). The Great Eight was presented as an attempt to introduce a measurement tool and also identify competency as a lens through which to study behaviour. The Great Eight methodology (Bartram, Citation2005), grounded in Big Five model of personality (Goldberg (Citation1990), therefore forms the theoretical background to this study.

4. Objectives

This mixed methods study adopts an interpretist agenda and seeks to make a contribution to knowledge in the study of access to finance and entrepreneurship through the application of academic models developed in the psychology domain. Overall, the research seeks to answer the question:

Can psychometric testing be used to explain, predict and measure behavioural competences and the funding resource orchestration of the entrepreneur?

The objectives of the study are as follows:

1. Present a behavioural competency profile for a sample group of entrepreneurs and identify the differences between individuals.

2. Explore the use of psychometric testing in explaining and predicting how individual entrepreneurs seek finance for the firm.

5. Develop a methodology for entrepreneurs, policymakers and financial institutions to identify competencies in finding finance, and overcome problems of information asymmetry.

The study identifies entrepreneurs who are both successful and unsuccessful in finance applications and those that did not apply, comparing behavioural competency profiles, thus overcoming any bias towards successful enterprises (Rauch, Citation2007).

5. Methodology

This study was conducted using a longitudinal, fieldwork process incorporating analytical induction methodology. It adopts a pragmatic realist approach (Watson, Citation2013). As a sector, Creative Industries is dynamic and therefore more sensitive to unfavourable environments and one which over the course of this 3-year longitudinal study, follows Pettigrew’s recommendation to “go for extreme situations, critical incidents and social drama” and “provides a transparent look at growth, evolution, transformation, and conceivably decay of an organisation over time” (Pettigrew, Citation1990, p.277–280).

Size of business is another factor that might also moderate the effects of the individual. Creative Industries, with a larger proportion of smaller, growing firms, also allows for more expression of individual characteristics (Van Geldern et al. Citation2000).

A convenience sample of 60 entrepreneurs was recruited. The participants were screened in order to ensure each individual was the main financial decision maker in the company. In almost all cases, this person was also the owner, managing director, or senior partner (BDRC Citation2013). The panel was selected through trade networking activity, exhibitions and science park events. In order to participate, the entrepreneur had to evidence:

A desire to grow coupled with an increase in employment by 20% in at least 1 year in the last 5 years.

The raising of funds or the intention to raise funds in the future.

Active trading (indicated in year of incorporation).

A minimum of one employee in addition to the entrepreneur.

A profile of the sample is summarised as follows:

Within the definition of Creative Industries, 16 firms are software developers, 20 are mobile gaming companies, five develop social networking tools, three are commercial designers and five are promotional design agencies. Ten entrepreneurs are females and 50 are male. Age groups are 25–55. None of the firms are more than 20 years’ old and the maximum level of turnover is £1.8 million. Firms are based throughout the UK but predominantly in the Midlands. The panel profile is detailed in Table .

Competency data on each Entrepreneur was collected using “Trait”, a personality inventory assessment which measures 13 dimensions of personality and nine behavioural competences on a scale 0–10. The nine Trait competencies together with research propositions are detailed in Table . Each entrepreneur is given a prefix T 1–60.

Table 1. Panel profile of entrepreneurs

Table 2. Research propositions

Trait is grounded in the Big Five Model of personality (Goldberg, Citation1990) and Bartram’s Great Eight Competency Model (Bartram, Citation2005). Semi-structured Interviews were recorded taking between 30 min and 1 h with each entrepreneur annually over 3 years. The questionnaires were designed in order to evidence entrepreneurial behaviour, defined as “the concrete enactment by individuals (or teams) of tasks or activities” within a funding context (Bird et al., Citation2012: p.890). Using an analytic induction methodology (Znaniecki, Citation1934), the research question is examined using propositions with the goal of most accurately representing the reality of the situation.

Qualitative, semi-structured interviews explored the funding activities of the entrepreneur; what is the process through which they try and raise funds and what evidence is there of using behavioural competences in order to achieve their funding objectives. Questions are detailed in Appendix 1. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and coded directly using NVivo 10 qualitative research software, seeking to avoid the weaknesses highlighted by Bazeley (Citation2007, p.132) that “too often qualitative researchers rely simply on the presentation of key themes supported by quotes…” The “density” of each code (Carter, Shaw, Lam, & Wilson, Citation2007) is calculated by using the number and percentage of text characters that respondents spend talking about specific codes. Researcher bias was checked through a coding test with another researcher.

6. Results

6.1. Results of behavioural competences using psychometric testing

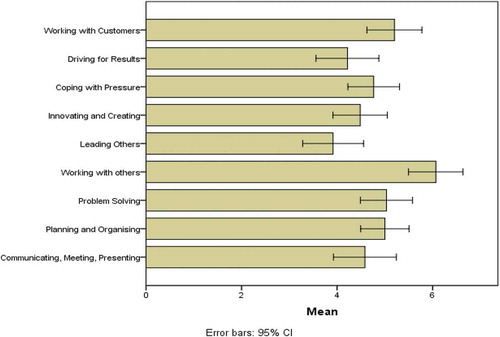

The mean data for the Behavioural Competency Score (BCS), 0–10 for all 60 of the entrepreneurs (T1–T60), is presented as follows:

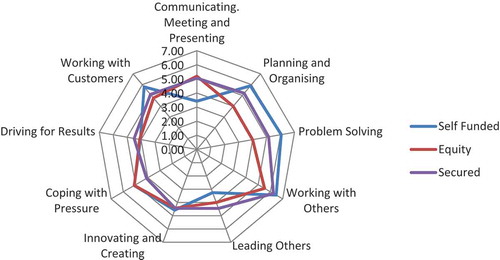

The results from this research indicate a tendency for higher competences in collaborative behaviours, along with business planning and problem-solving. Working with Others (6.07) and Working with Customers (5.2) are the highest scores. Leading Others (3.92) and Driving for Results (4.22) have the lowest BCSs. These results are in line with more recent studies (Zhao & Lumpkin, Citation2010) that the clichéd view of the swashbuckling entrepreneur emphasising leadership (Brockhaus, Citation1980) and locus of control (Begley & Boyd, Citation1987), for example, are at odds with reality.

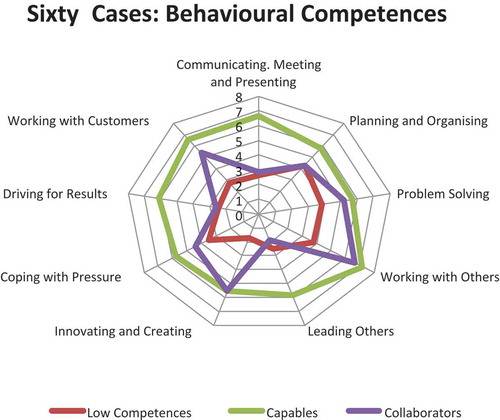

Cluster analysis, using Ward’s method, was then performed to identify groups (clusters) within the 60 cases of entrepreneurs, i.e. those entrepreneurs who share similar characteristics across the nine Behavioural Competences. For ease of clarity of subsequent analysis, each group is given a name and the mean scores for each group are presented as follows:

Capables has the highest competence scores in all groups; again Working with Others is the strongest (7.14), followed by Communicating, Meeting and Presenting (6.68), Working with Customers (6.61) and Driving for Results (6.14). Although the remaining competencies have lower scores, they are still higher than the other two groups. On balance, this group is the closest to the traditional view of entrepreneurs.

Collaborators has a focus on co-operation with high competency in Working with Others (6.67) and Working with Customers (5.4), followed by lower scores for Innovating and Creating (5.53) and Problem-Solving (5.2).

The Low Competences group above displays low scores across all competences; Planning and Organising (4.29) is the strongest competency in this group. The group is the most introverted; less interested in others with few social skills and methodical in approach.

Figure illustrates the mean behavioural competence scores and Figure illustrates the data, and the distinctive differences between the three clusters:

6.2. Funding outcomes years 1–3

6.2.1. Funding outcomes by cluster

Table details the number of entrepreneurs in each cluster, and among them, the number of entrepreneurs making successful, unsuccessful and non-applications (Didn’t Apply), in each of the 3 years of data collection. Interviews were carried out between September 2011 and August 2014 and as much as possible at 12-month intervals. Four cases dropped out of the programme after Year 1; 56 cases were analysed in Years 2 and 3.

Table 3. Applications versus Clusters

Twenty-eight entrepreneurs in the Capables cluster took part in the study in Year 1. This reduced to 26 who agreed to continue their participation in the study in Years 2 and 3. The Capables cluster was consistently more successful in funding applications over the periods; 11 entrepreneurs (39%) in this cluster made successful applications in Year 1, 13 (50%) in Year 2 and 13 (50%) in Year 3. This group also had the fewest unsuccessful applications; only three over the 3-year period. The number of Capables choosing not to apply for finance was also fairly stable over the period. Fifteen Collaborators participated in the study throughout the 3-year period. Collaborators had mixed results.

The highest proportion of this cluster making successful applications was in Year 2 at seven (47% of Collaborators); this group had four unsuccessful applications over the 3-year period and also had the highest proportion of non-applications (67%, 40% and 66%, respectively). Seventeen Low Competence entrepreneurs embarked on the study and this reduced to 15 for Years 2 and 3. The Low Competence group had the lowest level of success; 13 unsuccessful applications over the period with a success rate below 27%. Non-applications were also high at 64%, 33% and 60%, respectively.

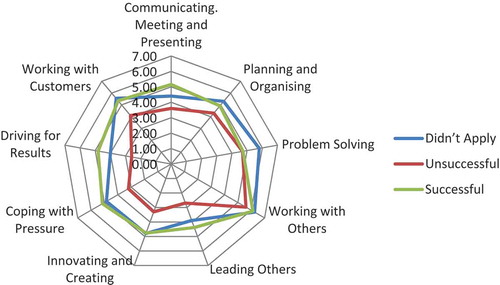

Using the BCS scores, the study also analysed Behavioural Competency by funding outcome and these are illustrated in Figure .

Unsuccessful applications had lower levels of competencies compared with entrepreneurs, who either chose not to apply, or made successful applications. Successful cases were stronger in Communicating, Meeting, Presenting, Leading Others, Coping with Pressure and Driving for Results. Didn’t Apply cases were stronger in Planning and Organising, Problem-Solving, Working with Others, Innovating and Creating and Working with Customers.

6.3. Funding outcome by cluster: significance test

Collecting three tranches of data produced a sufficient sample to make further statistical analysis appropriate. Analysing all applications over the 3-year period, a Chi-Square test was performed and confirmed the significance of the relationship between cluster membership and application outcome χ2 (1, n = 172) = 21.488, p < .000). This shows that cluster membership is an indicator of funding outcomes

6.3.1. Funding type versus cluster group

Self-Funded are those entrepreneurs who have used only internal resources to fund the firm, either through working capital, director’s loans or qualifying for grants. Equity-funded is those who have shared equity with third-party investors. Secured Funding is loan finance, where entrepreneurs have arranged borrowing using secured forms of finance

Capables had the same proportion (31%) of self-funded entrepreneurs and equity-funded, and overall, had a greater proportion of secured funding. Collaborators had a greater proportion of Self Funders (49%). Low Competences were equally spread across all funding types.

Funding type by cluster remained very stable for each entrepreneur. Only two entrepreneurs changed funding type over the period of the study.

By examining the BCSs across these different groups, Figure presents the differences in competencies across funding types.

Equity-funded entrepreneurs have higher BCSs in Coping with Pressure and Communicating Meeting and Presenting, possible indicators of the process of both presenting and subsequently working with third-party investors. Entrepreneurs who are self-funded or use secured finance have higher BCSs in Planning and Organising and Problem-Solving, possibly due to competences required to both satisfy secured lenders or for problem-solving in a totally self-funded business.

6.4. Funding type by cluster: significance test

Analysing applications over the 3-year period, a chi-square test was performed and confirmed that the relationship between cluster membership and funding type was not significant (χ2 (1, n = 172) = 4.495, p < .343).

Entrepreneurs were also asked if, in principle, they would be willing to share equity in the company, i.e. was equity sharing simply not an option in principle. A chi-square test was performed and confirmed that there was no significance between cluster membership and willingness to share equity.

6.4.1. Funding outcome by funding type

Seventy-eight per cent of Entrepreneurs, who were self-funded at the outset of the research, remained self-funded at the end. Of particular note in Table is the success of equity-funded entrepreneurs to make further successful funding applications, either for new investors or existing investors “following-on”. Secured funders had mixed results with 30% having applied with successful applications and 57% choosing not to apply over the 3-year period. This is detailed in Table .

Table 4. Funding type by cluster

Table 5. Funding outcomes by funding type

6.5. Funding outcome by funding type: significance test

Analysing applications over the 3-year period, a chi-square test was performed and confirmed the significance of the relationship between funding type and funding outcome (χ2 (1, n = 172) = 51.466, p < .000).

6.5.1. Using advisors

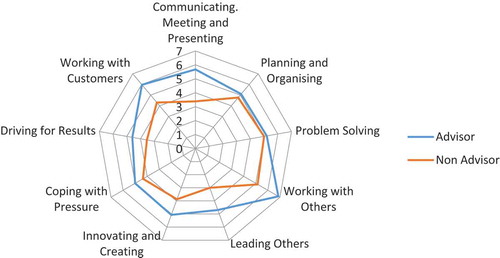

This is summarised in Figure . To provide increased insight into the degree to which entrepreneurs Work with Others, each was asked in every phase of the study to confirm if advisors had been used to assist decision-making, in relation to funding. Table analyses this by cluster:

Table 6. Advisors versus clusters

Table 7. Indicates relationship between the use of advisors and applications outcomes

Table 8. Year 1 coded interview density

Table 9. Year 2 coded interview density

Table 10. Year 3 coded interview density

In the study, 77% of Capables reported using advisors in each year of the study. Collaborators also made use of advisors at 60%. Conversely, only 25% of the Low Competency cluster had appointed advisors during the period. Table indicates the relationship between use of advisors and application outcomes.

In the study, 47% of cases with advisors reported successful applications, in contrast with 19% non-advised entrepreneurs. When analysed with the Behavioural Competency scores, this group also outperforms non-advisors across all competences:

6.6. Advisors by cluster: significance test

Analysing the use of advisors over the 3-year period, a chi-square test was performed and confirmed the relationship between cluster membership and use of advisors was significant (χ2 (1, n = 172) = 32.974, p < .000).

A chi-square test was performed and confirmed the relationship between using advisors and application outcome was significant (χ2 (1, n = 172) = 27.462, p < .000). This would indicate the use of advisors results in more successful funding applications.

6.7. Semi-structured interviews, data collection and analysis

The nine behavioural competences were used as a guide to frame the semi-structured interviews and explore what the entrepreneur actually “did” in order to fund the firm. In addition, a tenth code was developed—Behavioural Difficulties—in order to explore how each cluster reacted to problems in the funding process.

Making up each of the Behavioural Competence Codes are a number of coded themes which emerged during the course of the interviews; descriptions for these are in Appendix 2.

6.7.1. Year 1 coded interviews

Phase 1 interviews were carried out between May and October 2012.

Working with Others accounts for the largest number of words coded in the interviews (All Cases—23%) and is the strongest code for Collaborators (31%). This is detailed in Table . An example of this was the emerging theme Serial Networking; T29 (a Collaborator), for example, develops digital games for use in the music industry. The business was established in 2010 and T29 has used private equity and angel finance to fund the business. He talks about how he used his network (coded to Serial Networking) to source funding: “I am an LBS alumni… one of my ex-classmates runs an offshore angel group. cooperating with her on the Isle of Man to pitch in front of high net worth individuals”.

Planning and Organising, Communicating and Presenting and Innovating and Creating were also strong interview themes. Coded within Planning and Organising, for example, was Capacity Planning. T9 runs a professional architecture practice in the West Midlands. The business has been established 10 years and has now grown to three branches—Midlands, North East, South West—with plans to open more. T9 has used a Government-backed bank loan to start and develop the business and plans to use private equity to expand in the future. He describes how he has developed a method of managing capacity in order to estimate the investment required for the business: “I have detailed capacity planning (Capacity Planning) translated into a spreadsheet which gives us a dynamic target to hit each month”.

Low Competency entrepreneurs had a significantly higher density (55%) of codes indicating difficulties associated with sourcing finance. T13, for example, … “Your (plan) P&L to a degree goes (Bad Planning) out the window … all very unpredictable. So it’s guesswork”.

Innovating and Creating also remained a strong theme and example of which was T6 (a Collaborator) who used a Peer-to-Peer lender to find an alternative to bank funding: “We have used Funding Circle … used them because the bank weren’t helpful … found through mailer … provided annual P&L plan, predictions, forecasts, unsecured, over three years … when the banks rained stuff in got a positive response. Didn’t meet anyone—all over the phone”.

A more detailed examination of the data revealed Planning and Organising was more prevalent for those entrepreneurs either not applying, or making successful applications. Planning and Organising was a stronger theme for the self-funded and secured group. Innovating and Creating and Communicating, Meeting and Presenting were stronger for equity-funded entrepreneurs. Working with Customers was a strong theme for Secured entrepreneurs. A strong theme for equity-funded entrepreneurs Communicating, Meeting and Presenting; T19, for example, “(Communicating the Vision) … financial data and soft skills that become apparent being consistent doing what you said you were going to do … and ensuring you communicate and let them know what is happening. So nervous these days … any sign people are not communicating things can go pear-shaped very quickly …”.

In Year 1, therefore, Working with Others and Planning and Organising were the strongest themes emerging in the interviews, particularly with Capables and Collaborators. Low Competence entrepreneurs reported the largest number of behavioural difficulties. Planning and Organising was a strong theme for Non-Applying entrepreneurs, and also for those using self-funded or secured-funded finance.

6.7.2. Year 2 coded interviews

This is detailed in Table . Working with Others, Communicating Meeting and Presenting, Innovating and Creating and Problem-Solving continued to be strong themes in the interviews and together make up, 54% of coded themes.

Working with Others is particularly strong for Capables and those entrepreneurs making successful applications; T45, for example, expanded into the United States and talks enthusiastically about the use of advisors: “This year we brought in advisors from the West Coast … Head of Mobile at Winga … she is a new investor one we have brought in (this year) …”.

Compared with Year 1 interviews, Collaborators, in particular, were keener to give examples of problem-solving competences. T29, for example, made changes through a new model which included a revenue share with a partner: “Now more focus on smaller amounts … get teamed up with global marketing partner … revenue share with them. (Developing a New Business Model) … when we are bigger will go back to Broono Mars …”.

Communicating, Meeting and Presenting was also again discussed in successful cases. T45 (a Capable) approached a number of new private investors: “Did pitches … clearly … looked at … angels who want to invest and make a social impact … (Approaching Investors) … we did a pitch there and ended up getting £90K from that group … got introduced to them in order to give a reference for someone else and they ended up being interested in the business …”.

Again Low Competences accounted for the largest number of behavioural difficulties, accounting for 75% of themes coded.

Increasing themes over Year 1, however, was Planning and Organising and Problem-Solving, particularly amongst Non-Applying entrepreneurs. Communicating, Meeting and Presenting was an even stronger theme for Equity-Funded entrepreneurs than in Year 1. Problem-Solving was also increasingly important for Self-Funded and Equity-Funded entrepreneurs. Planning and Organising remained a significant theme for Self-Funded entrepreneurs.

6.7.3. Year 3 coded interview analysis

This is detailed in Table . Again, Working with Others was again the strongest theme, with Capables and Collaborators in particular. Compared with Year 2, Innovating and Creating was also a stronger theme, particularly amongst those that were successful in funding applications. T08 (a Capable) successfully applied for a grant in the year and described the support he received from the SME Educational Programme: “Yeah, it was unbelievable, the training, the coaching, the people that came to the presentation, the follow-up stuff … I can just pick up the phone and speak to people, they’re there to basically find someone or find a way.

A closer examination of the data also indicated Driving for Results, along with Communicating, Meeting and Presenting and Planning and Organising were also strong themes amongst successful entrepreneurs. Innovating and Creating was a strong theme particularly amongst self-funded entrepreneurs.

7. Discussion

Data gathered through the Trait test enabled the study to group the entrepreneurs into competency clusters. Further statistical analysis confirmed cluster membership and funding outcome as significant and funding type and funding outcome as also significant. The 3-year qualitative study then allowed for deeper analysis of exactly what entrepreneurs “did” in order to raise finance.

For each of the eight propositions where there is a positive indication that the proposition is proven, this has been indicated although to confirm thoroughly from a philosophical perspective will require further studies. In some cases, no positive indication was found in propositions; further work will be required both in formation of propositions and also more data collection.

Working with Others has been a strong theme through all three phases of the interviews, particularly with Capables and Collaborators. Key themes emerging from the 3-year study included networking, using advisors and investigating joint ventures. It is also the strongest competence in this group of entrepreneurs and is the strongest competence amongst successfully applying entrepreneurs. However, higher scores also indicate an increased use of self-finance as opposed to equity or secured-funding, indicating collaborative skills may also be used, in some cases, to resource the firm, without the need for external finance. The use of Advisors was also researched specifically in the study and those entrepreneurs using Advisors were more likely to have successful funding outcomes, again statistically significant.

The methodology of analytic induction allows for modification of propositions as the themes emerge from the data. Working with Others is the highest competency level across all clusters. Capables scores highest across this competency, making most use of Advisors. This leads to a revised Proposition 1:

Revised Proposition 1: Working with Others: Being able to Work with Others Provides Opportunities to Access Finance and also Self-Finance. Positive indicator.

Communicating, Meeting and Presenting is associated with having social confidence in meeting and speaking, whilst also communicating clearly and persuasively. Business angels have become an important source of equity finance to SMEs and business angel activity and communication skills are key in presenting investment propositions.

Themes emerging in the study included presenting to potential international investors and there was evidence of social boldness, the confidence to interact with strangers (Zhang, Souitaris, Soh, & Wong, Citation2008) and entrepreneurs attempting to send signals to prospective investors (Spence, Citation1973) at pitching events, for example. In this study, Communicating, Meeting and Presenting was a strong competency amongst Capables and amongst successful applications

Proposition 2: Communicating, Meeting and Presenting: Being a good communicator can facilitate more access to finance. Positive indicator.

Increasingly SMEs are beginning to think more laterally of other potential methods of financing growth. Asset-based lending has increased and Social Lending, Crowdfunding and Peer-to-Peer lending have also increased in relevance through the course of this study. From the literature, therefore, innovative behaviour appears an important competence for an entrepreneur. Innovativeness is a strong competency for both Capables and Collaborators. Again, the study adds to knowledge by recognising some entrepreneurs have higher levels of competencies in Innovation and Creativity. It is clear that competences in these behaviours allow some entrepreneurs to be more innovative in their consideration of funding, both in terms of the nature of funding and finding the best funding option for the firm, whether they used these options or not. Proposition 3 is therefore modified and as follows:

Revised Proposition 3: Innovating and Creating: Innovating and creative competences gives entrepreneurs the opportunity to consider and access new forms of finance. Positive indicator.

Finance is considered a disproportionately important problem for high-growth firms, compared to other businesses (NESTA, Citation2011), as the entrepreneurs seek ways of funding growth. Yet, the difficulties in solving these problems appears to be giving rise to an increase in the non-seeker of finance, as entrepreneurs describe the main barriers to an application and discouragement expectation of an unsuccessful outcome. The Problem-Solving competence itself is not one of the highest BCSs and both Capables (5.7) and Collaborators (5.2) have similar levels overall. It included developing the business model in order to attract finance and also using match funding. Where this competency became more significant was in the “Didn’t Apply” group of entrepreneurs, who had a higher level of competence in this competence (5.8) compared to either Successful (4.92) or Unsuccessful (4.3) entrepreneurs. Self-funded entrepreneurs also had the highest competency in Problem-Solving (6.0).

It would appear, therefore, that this Problem-Solving competence indicates resourcefulness amongst self-funded, non-applying entrepreneurs. Interview data indicated evidence for this.

Revised Proposition 4: An entrepreneur who can problem solve is better able to select a self-funding strategy for the firm. Positive indicator.

In the Capables cluster, Planning and Organising is a mid-level competence in terms of performance (5.82). It is at a lower competence for Collaborators and Low Competence group. Not as strong as Problem-Solving, but it is also a stronger competence in the Didn’t Apply group of entrepreneurs, again indicating a level of resourcefulness amongst entrepreneurs. Themes emerging from the data included producing business plans, cash management and using flexible staff management to increase working capital. Again, this is a stronger competence amongst non-applications and secured funders, where debt providers are more likely to require more formal management controls in place.

Planning and Organising was a strong theme in the first phase of qualitative interviews. However, in the following 2 years when the study focused more on what the entrepreneur had actually “done” in the previous 12-month period, evidence of planning and organising was less prevalent. It remained a strong theme only in self-funded entrepreneurs.

Higher competencies in Planning and Organising also seem more relevant to those entrepreneurs choosing not to apply for finance (non-applications), but there is not the same evidence for this behaviour in the qualitative interviews, when this was a strong theme, but only in the first year of study. Therefore:

Revised Proposition 5: Planning and Organising: Entrepreneurs with a higher competence in planning and organising will be better able to self-fund and not require external finance. Proposition: Partial Positive Indicator.

Driving for Results is a strong trait for Capables, but not for Collaborators or Low Competence clusters. Emerging themes in the qualitative interviews included identifying growth and opportunity and using persistence and challenging behaviour. It is also a strong trait in successful applications.

Driving for Results emerged as a stronger theme as the research programme progressed, particularly amongst equity seeking Capables. These entrepreneurs were able to meet challenges in the business and were able to indicate a more proactive approach.

Proposition 6: Driving for Results: An entrepreneur who is driven can access more funding opportunities. Positive Indicator.

Within the study, Working with Customers was part of the collaborative competences that score most highly with Capables and Collaborators. In particular, some entrepreneurs were able to develop a relationship with customers which enabled more flexibility in payment terms, leveraging relationships with customers which increased working capital inflows into the business.

Working with Customers was one of the strongest competences overall and both Capables and Collaborators were particularly strong in this behaviour. These entrepreneurs were able to utilise this working relationship with customers to leverage working capital, or in some cases, actually provide a service on behalf of the customer, and in doing so, making it easier to plan cash flow.

Proposition 7: Working with Customers increases opportunities to access finance. Positive Indicator.

The classic image of the entrepreneur as a “risk taker” or an “extrovert” may discourage some individuals from becoming entrepreneurs who would otherwise be successful at this pursuit.

In this research study, Leadership is not one of the strongest competences amongst the Capable cluster of entrepreneurs, and within the group as a whole, it is the weakest competence. However, there was very little evidence in the interview data of this behavioural competence. (In year 3 no data were coded to this competence).

Proposition 8: Leading Others: Competency in leadership increases access to finance. No Positive Indicator.

The competence to cope with pressure was outlined by Dew and Wiltbank (Citation2008), identifying entrepreneurs who excel in an ability to remain calm, composed and free from worry or anxiety at times of pressure. Starting and growing a business involves periods of dealing with problems and setbacks in a calm, positive way and higher competences will be critical to good decision-making.

Often entrepreneurs are managing several activities at the same time, and managing a busy role with competing demands, without feeling undue pressure, will improve effective decision-making.

Overall, it is not a strong competence either for Capables, or overall in all clusters, and there was very little evidence of this behaviour in the semi-structured interviews.

Proposition 9: Coping with Pressure: Entrepreneurs who are better able to cope with pressure increase access to finance. No Positive Indicator.

8. Conclusion

Since 2008, various Government initiatives have tried to improve the flow of funds to small firms, recognising this sector as key to economic growth. Despite these efforts, total stock of lending still remained lower in 2014 than at any point since 2008. New forms of funding have emerged including a variety of Peer-to-Peer funding models, business angel and asset finance has increased, but still today the environment for capital-raising remains a challenge for the small firm.

Entrepreneurs are unable to influence supply side factors. This study therefore takes an alternative position and looks at the demand side of market failure; so what can the individual entrepreneur do in order to successfully fund the firm (Mueller et al., Citation2012). This field presents a challenge to investors, as information asymmetry prevents the efficient flow of information about the firm. Prospective financiers, therefore, find it difficult to access the potential of new ventures (Baum & Silverman, Citation2004; Venkataraman, Citation1997).

The lens through which this study examines entrepreneurship is behaviour, the “missing field of research” (O’Gorman et al., Citation2005, p.2), and specifically, behavioural competences. The study also seeks to introduce measurement validity (Bird et al., Citation2012) and therefore compare behavioural competence amongst a group of entrepreneurs. The study uses propositions developed through an analytical methodology in order to find explanation for the existence, or not, of observed phenomenon. For construct validity, 60 cases are used, and all the data have been derived from coded interview data.

For reliability, NVivo 10 was used to create a research database and literature was reviewed to inform the development of the research propositions. The results were also validated with a group of external practitioners including representatives from venture capital, business angels and clearing banks. With regard to limitations of the study, the work would benefit from consideration of other sectors, increased sample size and more in-depth interviews.

In particular, the identification of three distinct groups in this longitudinal study means belonging to one of these groups predicts likely behaviour when searching for finance. Propositions developed through analytical induction confirmed specific behaviours associated with finding finance.

The study has implications for Financial Institutions, Business Angels and Accelerator Programmes using competency data to differentiate between entrepreneurs and aid decision-making in the allocation of funding and other support. The study also strengthens the argument for more longitudinal studies. Lumpkin and Dess (Citation1996) report that around three quarters of the performance studies and all the intention studies which the authors reviewed were cross-sectional in nature, which raises a question, in their own words, of “the causal direction of our observed effects” (p.398).

Through the domains of entrepreneurship and psychology, the study adds to existing literature through the novel application of “Big Five” and “Great Eight” theories of personality and competency. The three distinctive clusters were proven to have different characteristics in relation to funding outcomes, funding types and use of advisors, for example. It therefore follows that identification of an entrepreneur as belonging to one of the three groups has considerable predictive significance in relation to behavioural competences and how the entrepreneur accesses finance. For the practitioner, it provides a methodology which enables the identification of competences which overcome the difficulties caused by information asymmetry in the process of funding the firm.

By both measuring behavioural competence and identifying the associated behaviour, the research makes a contribution through the use of psychometric testing to explain and predict how individuals finance the firm; what Wright and Stigliani (Citation2013) describe as resource orchestration.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Geoff Parkes

My main areas of research interest are international marketing strategies and small firms. I have a background in practice and am interested in the areas of behaviour and factors influencing outcomes in entrepreneurial ventures. This study is in line with further work currently undertaken in language competency and the impact on competitive advantage in small firms.

Dr Geoff Parkes is the Associate Dean International, Aston Business School and the Associate Pro Vice Chancellor International at Aston University. He is a Warwick MBA and holds a Doctorate of Business Administration from Aston University. He is currently seconded to Aston Hong Kong where he leads the University's international collaborative activities in China and East Asia. He supervises DBA and PhD candidates and his teaching experience includes a variety of entrepreneurship programmes including the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Business programme. He is a visiting lecturer at VWA-Studienakademie, Stuttgart and Hong Kong Polytechnic University. He is a Senior Fellow of the UK Higher Education Academy.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Bartram, D. (2005). The great eight competences: A criterion-centric approach to validation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1185–1203. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1185

- Baum, J., & Silverman, B. (2004). Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 411–436. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00038-7

- Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 587–598. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.587

- Bazeley, P. (2007). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. London: Sage.

- Begley, T. M., & Boyd, D. P. (1987). Psychological characteristics associated with performance in entrepreneurial firms and smaller businesses. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(1), 79. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(87)90020-6

- Bird, B., Schjoedt, L., & Baum, J. R. (2012). Entrepreneurs’ behavior: Elucidation and measurement introduction. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 36(5), 889–913.

- Black, J. (1998). Entrepreneur or entrepreneurs? Justification for a range of definitions. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 10, 45–65.

- BOE. (2014). Trends In Lending. Relates to Published Lending Report from the Bank of England.

- Bridge, S., O’Neill, K., & Cromie, S. (1998). Understanding enterprise entrepreneurship, and small business. London: MacMillan.

- Brockhaus, S. R. H. (1980). Risk taking propensity of entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 509–520.

- Burgoyne, J. (1989). Creating the managerial portfolio: Building on competency approaches to management development,’ management education and development. Management Education and Development, 12(1), 55–61.

- Burgoyne, J. (1993). The competence movement: Issues, stakeholders and prospects. Personnel Review, 22(6), 6–13. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000000812

- Bygrave, W., & Timmons, J. (1992). Venture capital at the cross roads. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Caird, S. P. (1993). What do psychological tests suggest about entrepreneurs? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 8(6), 11. doi:10.1108/02683949310047428

- Carter, S., Shaw, E., Lam, W., & Wilson, F. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurship, and bank lending: The criteria and processes used by bank loan officers in assessing applications. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 31(3), 427–444.

- Ciavarella, M. (2004). The Big Five and venture survival: Is there a linkage? Journal of Business Venturing, 19(4), 465. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.03.001

- Collins, J., & Porras, J. (1994). Built to last: Successful habits of visionary companies. Harper: New York.

- Deakins, D., North, D., Baldock, R., & Whittam, G. (2008). SMEs access to finance: Is there still a debt gap? Belfast: ISBE.

- Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2008). ‘The effect of small business managers’ growth motivation on firm growth: A longitudinal study. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 32(3), 437–457.

- Dew, R. S., & Wiltbank. (2008). Outlines of a behavioral theory of the entrepreneurial firm. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 66(1). doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2006.10.008

- Fraser, S. 2014. Back to borrowing? Perspectives on the ‘Arc of discouragement. White Paper No 8. Birmingha: Enterprise Research Centre.

- Frese, M., van Gelderen, M., & Ombach, M. (2000). How to plan as a small scale business owner: Psychological process characteristics of action strategies and success. Journal of Small Business Management, 38(2), 1–18.

- Gartner, W. B. (1989). Some suggestions for research on entrepreneurial traits and characteristics. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 14(1), 27–37.

- Gartner, W. B., Bird, B. J., & Starr, J. A. (1992). Acting as if: Differentiating entrepreneurial from organizational behavior. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 16(3), 13–31.

- Gherardi, S. (2003). Feminist theory and organizational theory: A dialogue on new bases. The Oxford handbook of organization theory. C. Knudsen and H. Tsoukas (pp. 210–237). Oxford: OUP.

- Gibb, A., & Davies, L. (1990). In pursuit of frameworks for the development of growth models of the small business. International Small Business Journal, 9(1), 15–31. doi:10.1177/026624269000900103

- Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative ‘Description of personality’. The big five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216–1229.

- Granovetter, M. (1973). ‘The strength or weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469

- Gruglis, I. (1997). The consequences of competence: A critical assessment of the management NVQ. Personnel Review, 26(6), 428–444. doi:10.1108/00483489710188865

- Holton, E., & Naquin. (2000). Developing high-performance leadership competency: Advances in developing human resources. San Fransisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

- Jones, O., & Jayawarna, D. (2012). Are financial institutions failing UK SMEs. ISBE, 35th Annual Conference. Dublin.

- Locke, E., & Latham, G. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NY: Prentice Hall.

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance.’ Academy of management. The Academy of Management Review, 21, 1. doi:10.5465/amr.1996.9602161568

- Magnusson, D., & Endler, N. (1977). Personality at the crossroads: Current issues in interactional psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- McCarthy, M., Krueger, D., & Schoenecker, T. (1990). Changes in the time allocation patterns of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 15(2), 7–18. doi:10.1177/104225879101500203

- McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Free Press.

- Moran, P. (1998). Personality characteristics and growth orientation of the small business owner. International Small Business Journal, 16(3), 17–38. doi:10.1177/0266242698163001

- Mueller, S., Volery, T., & von Siemens, B. (2012). What do entrepreneurs actually do? An observational study of entrepreneurs’ Everyday behavior in the start-up and growth stages. Entrepreneurial Theory and Practice(September), 995–1017. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00538.x

- Myers, S. C. (1984). The capital structure puzzle. The Journal of Finance, 39(3), 575. doi:10.2307/2327916

- NESTA. (2011). The vital growth report research report.

- O’Gorman, C., Bourke, S., & Murray, J. A. (2005). The nature of managerial work in small growth-orientated businesses. Small Business Economics, 25(1), 1–16. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-4254-z

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1990). Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organization Science, 1(3), 267–292. doi:10.1287/orsc.1.3.267

- Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2007). ‘Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 16(4), 353–385. doi:10.1080/13594320701595438

- Rauch, R., van Doorn, R., & Hulsink, W. (2014). A qualitative approach to evidence-based entrepreneurship: Theoretical considerations and an example involving business clusters. Entrepreneurial Theory and Practice, 38, 333–368. doi:10.1111/etap.2014.38.issue-2

- Sadler–Smith, E., Hampson, Y., Chaston, I., & Badger, B. (2003). Managerial behavior, entrepreneurial style, and small firm performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(1), 47. doi:10.1111/1540-627X.00066

- Sandberg, W. R., & Hofer, C. W. (1987). Improving new venture performance: The role of strategy, industry structure, and the entrepreneur. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(1), 5. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(87)90016-4

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency Academy of management. The Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263. doi:10.5465/amr.2001.4378020

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2004). Making it happen: Beyond theories of the firm to theories of firm. Wiley.

- Schumpeter, J. (1934). The theory of economic development. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimension of entrepreneurship. The Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship, 72–90.

- SME Finance Monitor. (2012). BDRC Continental. London: BDRC

- SME Finance Monitor. (2013). BDRC Continental. London: BDRC

- SME Finance Monitor. (2014). BDRC Continental. London: BDRC

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signalling. Journal of Quarterly Economics, 87, 355–379. doi:10.2307/1882010

- Venkataraman, S. (1997). The distinctive domain of entrepreneurship research: An editor’s perspective. Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence, and Growth, J. K. Greenwich and B. R.3: 119–138.

- Watson, T. (2013). ‘Entrepreneurial action and the EuroAmerican social science tradition: Pragmatism, realism and looking beyond ‘the entrepreneur’. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(1–2), 16–35. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.754267

- Wright, M., & Stigliani, I. (2013). Entrepreneurship and growth. International Small Business Journal, 31(1), 3–22. doi:10.1177/0266242612467359

- Zhang, J., Souitaris, V., Soh, P.-H., & Wong, P.-K. (2008). A contingent model of network utilization in early financing of technology ventures. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 32(4), 593–613.

- Zhao, S., & Lumpkin. (2010). The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(2), 381-404.

- Znaniecki, F. (1934). The method of sociology. New York, NY: Farrar & Rinehart.

Appendix 1.

Semi-Structured Interview Questionnaires

Phase 1 Semi-Structured Interview Questionnaires

Introduction

Do you expect a requirement to raise finance in the next 3 years?

Have you raised any finance in the last 12 months?

When was the business established?

How many employees?

What is the most recent turnover?

What is the current funding structure?

How long have you spent in the industry?

What is your Functional Expertise?

What are your qualifications?

Funding

What is your experience of running an SME?

Have you any experience of family entrepreneurship?

How much do you think your knowledge of this industry helps you to solve funding problems?

Do your qualifications help you to access finance?

How have you planned your funding requirements?

How do you expect to plan your funding requirements differently in the future?

How have you solved funding problems in the past?

In what ways do you think you will solve funding problems in the future?

How have you presented and communicated your funding requirements?

Do you expect to change the way you communicate and present your funding requirements in the future?

Have you examples of how you have cooperated with other individuals or businesses in order to solve funding problems?

Do you expect to change how you co-operate with other individuals or businesses to solve funding problems in the future?

Do you lead the funding process in your firm or is it the responsibility of others and you take a supporting role?

Can you give me any examples of how you could be innovative and creative in the way you fund your business?

How do you cope with pressure and managing uncertainty?

Do you think Driving for Results will be an important factor when trying to raise finance?

How do you develop relationships with customers?

Can you think how your own social skills could be important in raising funds for your business?

Do you think your own financial skills could help or hinder in funding applications?

Phase 2 Semi-Structured Interview Questionnaires

(A.) DBA: Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Finding Growth Finance

What new funding have you access to in the last 12 months?

Why now?

Why did you select this?

How did you do it?

How much in relation to your current equity plus debt?

And how much have your employees grown by … from what to what

How much time did it take (hours of your time)

What were the stages in the process? (time for each stage)

Planning—inc cash flow (with who); what meetings

Networking

Exit

New Business Model

Have you been unsuccessful in any funding applications over the last 12 months?

Why did you select this?

On reflection, why was the application unsuccessful?

How much time did it take? (hours of your time)

What were the stages in the process? (time for each stage)

Planning—inc cash flow (with who); meetings

Networking

New Business Model

Are you trying to access new funds currently?

Why now?

Why did you select this type?

How did you do it?

How much time is it taking? (hours of your time)

What are the stages in the process? (time for each stage)

Planning—inc cash flow (with who); meetings

Networking

New Business Model

Are you planning any new funds in the next 12 month?

Why

Is it debt?

How will you do this—Prompts

How much time did it take? (hours of your time)

What were the stages in the process? (time for each stage)

Planning inc cash flow (with who); meeting

Or equity?

How much time did it take? (hours of your time)

What were the stages in the process? (time for each stage)

Planning (with who); meeting

Why this type?

New Business Model

Would you exchange equity for the opportunity to access growth finance in the future?

Are you considering any form of funding that you would consider being innovative?

Moving Premises (Clustering?)

Through new income streams

Learning about finance

Customers or Suppliers

Is there someone you would describe as a formal Advisor (or Mentor) to the business—YES or NO

Who and why did you choose this person(s)?

How often do you discuss issues with them?

What issues; how much time?

Have you appointed formal Non-Exec to the Board?

Why?

How often do you discuss issues with them?

What issues; how much time?

Is it still your desire to grow? YES/NO/MAYBE

If yes, how much over the next 5 years?

Appendix 2. Theme and coding summary