?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study examined the influence of corporate board characteristics on environmental disclosure quantity of listed firms in two leading emerging economies: South Africa and Nigeria which practice integrated reporting framework and traditional reporting framework, respectively. Two issues motivate the study: First, calls by researchers for integrated reporting regulation in Nigeria. Second, the challenge facing regulatory bodies and companies boards in Nigeria in ensuring commitment to the protection of the environment and the society. Many studies have examined the influence of corporate governance on environmental disclosure at the cross-country level, documenting evidence that corporate governance mechanisms are essential for corporate ecological reporting. However, these studies examined settings based on the legal framework and mostly focused on companies quoted on common and civil law countries. They neglected the weak and robust reporting framework and difference within either common or civil law countries. Our study provides evidence on corporate board characteristics influence on environmental disclosure of quoted firms in South Africa and Nigeria. Data obtained from annual reports of 303 environmentally sensitive companies selected from South Africa (213) and Nigeria (90) was investigated using descriptive, multivariate, and regression model. Major findings indicate a significant positive association between board independence and environmental disclosure in Nigeria. In South Africa, 45% of environmentally sensitive industries significantly influence environmental disclosure, while 51% of environmentally polluting industries in Nigeria show insignificant association with environmental disclosure. Our findings are helpful to policymakers and other regulators for an impactful framework on environmental reporting.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Reporting on the environmental impact of the company’s activities ensures commitment to the protection of the environment and the larger society. Researchers in Nigeria call for regulation of integrated reporting. This research investigated the corporate board characteristics influence on environmental disclosure of quoted companies in two different countries (South Africa and Nigeria). These two countries adopt integrated financial reporting and traditional reporting framework, respectively. Data on annual reports of companies from the two countries were used. Results revealed a more significant positive association between board characteristics and environmental disclosure in South Africa and less relevant association in Nigeria. In a traditional reporting framework, the effect of environmentally sensitive-industries is insignificant and highly significant in the integrated reporting framework. The results enhance the policymakers and regulators decision on regulation of integrated reporting in Nigeria and other countries not under integrated reporting. Corporate board’s responsibility towards successfully integrated reporting also highlights.

1. Introduction

A call for companies environmental impact assessment and disclosure has assumed enormous dimensions over the decades. This clarion call aimed at providing a sustainable environment that will be conducive to the human and corporate organisations to operate efficiently (Votsi, Kallimanis, & Pantis, Citation2017). Disclosure is a means through which a company reports its environmental activities to the stakeholders (Hendri & Puteri, Citation2015). In recent times, corporate governance has been considered essential and relevant in sustainability reporting because research results reveal that it is a factor that influences the level of environmental disclosure (Omer & Andrew, Citation2014). Through environmental disclosure, firms project their corporate governance effectiveness in promoting sustainability, accountability, and transparency (Ajibodade & Uwuigbe, Citation2013).

Several studies have examined the influence of corporate governance on environmental disclosure at the firm level (Ienciu, Popa, & Ienciu, Citation2012), country-specific (e.g. Odoemelam & Okafor, Citation2018; Baboukardos, Citation2017; Akbas, Citation2016; Liao, Luo, & Tang, Citation2015), and cross-country evidence (Halme & Huse, Citation1997; Khlif, Guidara, & Souissi, Citation2015). Collectively, these studies show that corporate governance mechanisms are essential for corporate environmental reporting. However, the reviews on cross-country perspective have mostly examined a setting based on a legal framework (e.g. Khlif et al., Citation2015) and most importantly, the focus has been on companies quoted on common and civil law countries neglecting the weak and robust reporting framework. The studies have mainly concentrated on differentiating their sample size with regard to cross-country analysis based on the difference in common law and civil law countries (Khlif et al., Citation2015). The authors of these prior studies failed to consider the tendency of within laws reporting framework, (i.e. within either common or civil law countries). No empirical research compared all in one fit and traditional reporting on environmental disclosure.

We provided evidence on corporate board characteristics influence on environmental disclosure quantity of quoted firms in South Africa and Nigeria. Furthermore, we chose South Africa and Nigeria (two common law countries), unlike Khlif et al. (Citation2015) that investigated the relationship between corporate performance and social and environmental disclosure of South Africa (common law country) and Morocco (civil law country). Though these two African leading economies have the same legal system, a reasonable gap exists between the two nations in their corporate reporting framework for quoted firms. South African quoted companies are mandated to submit an integrated annual report as approved by the King III report (Rensburg & Botha, Citation2014; Zhou, Simnett, & Green, Citation2017). While in Nigeria, the traditional corporate annual reporting is still a vital medium of relating to the stakeholders, which Otu Umoren, John Udo, and Sunday George (Citation2015) found to be lacking relevant information concerning the natural capital and other non-financial issues. The empirical evidence on the determinants of disclosure decisions is largely inconclusive (Beyer, Cohen, Lys, & Walther, Citation2010; Gray, Javad, Power, & Sinclair, Citation2001; Ott, Schiemann, & Günther, Citation2017).

Our study contributes to accounting literature on the determinants of corporate environmental disclosure (Khlif et al., Citation2015). For the first time, we provide evidence between two countries of the same legal system but have different reporting mechanisms.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 the theoretical framework, literature review, and hypotheses development. Section 3 discusses the research methodology, and Section 4 explains the results and discussion. Finally, Section 5 conclusions and limitations as well as directions for future studies.

2. Underpinning theory

The theoretical framework adopted for this study to examine the relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and the quantity of corporate environmental disclosure practices of quoted companies in South Africa and Nigeria annual reports are the legitimate and stakeholder theories. These theories are linked to the concept that there exists a social contract between the organisation and society whereby an organisation endeavours to operate within the values and norms of the society and is being held responsible and accountable to its entire stakeholders (Gray et al., Citation1995).

2.1. Legitimacy theory

Legitimacy theory is derived from the concept of organisational legitimacy. It grants an organisation the right to carry out its operations in an agreement with society’s interests. Hence organisations seek to operate within the norms and aspirations of their respective communities. When there is a disparity between two value systems, there is a threat to the company’s legitimacy. The argument surrounding legitimacy theory is that companies can only survive if they are operating within the framework of the society’s norms and values. Greiling and Grüb (Citation2014) stress that an organisation must be accountable for its actions. Legitimacy theory is perceived as a possible reason for the recent rapid increase in environmental disclosure as corporate entities strive to be greenish in their operations (Braam, Uit de Weerd, Hauck, & Huijbregts, Citation2016; Lan, Wang, & Zhang, Citation2013; LYTON CHIYEMBEKEZO, Citation2013; Prasad, Mishra, & Kalro, Citation2016). Corporate disclosures represent a response to environmental pressures and the urge to legitimate their existence and actions. Companies disclose social and environmental information voluntarily to maintain their legitimacy. They aim to obtain the impression of the society that they are socially responsible. This reality of this perception lies in the strict adherence to the rule of law, and investors and citizen’s right to a healthy environment enshrined in the Constitution.

2.1.1. Stakeholder theory

Stakeholder theory is also considered as an explainable theory for corporate environmental accounting (Deegan & Blomquist, Citation2006; Depoers, Jeanjean, & Jérôme, Citation2016; Liao et al., Citation2015). It involves the recognition and identification of the relationship existing between the company’s behaviours and its impact on its stakeholders. The stakeholder theory perspective takes cognisance of the environment of the firm, including customers, suppliers, employees, and other segments of the society. As a result of this relationship, the company requires support from the stakeholders to survive. The connection must be managed if the company considers the stakeholders important. One of the ways of maintaining that relationship is by providing information through voluntary social and environmental disclosures to gain support and approval of these stakeholders. These stakeholders of the enterprise and lobbying decisions of these individuals are determined by the stakeholders who possess power, urgency, and legitimacy (Ahmad, Citation2015).

We conclude that legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory are the theories that dominate the explanations of social and environmental impact disclosure practices.

2.1.2. Empirical evidence

A good number of researchers have provided empirical evidence on the relationship between the extent of environmental disclosure and corporate governance. Mostly corporate governance mechanism is used as an independent variable and environmental disclosure as a dependent variable. In this section, we review some of the existing empirical studies as supported by underpinning theories.

2.2. Environmental disclosure quantity

Otu Umoren et al. (Citation2015) from Nigeria provided evidence that the level of environmental information reported by sample companies listed in the Nigeria Stock Exchange (NSE) was 7%. The study used a sample of 40 companies across eight sectors and data from two-year 2013–2014 was analysed using descriptive statistics, correlation, and linear regression. The study desperately calls for integrated reporting in Nigeria. Otu Umoren et al. (Citation2015) sample size based on the firm-level study is limited regarding generalising the result of the survey.

In South Africa, KPMG (Citation2013) reported that companies that prepare environmental report increased from 45% in 2008 to 98% in 2013. Mandatory integrated annual reporting, enhanced governance structure, and a strong legal environment could be factors to this upsurge. Ahmed Haji and Anifowose (Citation2017) confirmed a significant rise in the overall corporate disclosure because of the adoption of integrated reporting in South Africa. This increase may be attributed to public pressure (Darrell & Schwartz, Citation1997). The current study focused on investigating and providing empirical evidence of the relationship between the extent of environmental disclosure and corporate board characteristics of listed companies in Nigeria and South Africa taking cognisance of both firm attribute in one hand and reporting framework of the individual country.

2.3. Corporate governance

Recent scandals that ravaged some companies have awakened a good number of studies on how entities are governed. Beekes, Brown, Zhan, and Zhang (Citation2016) in a cross-country study involving 23 countries confirmed: “the belief that better-governed firms make more frequent disclosures to the market” also corroborated by Ntim (Citation2016) and Rupley, Brown, and Marshall (Citation2012). That often happens in common law countries (Beekes et al., Citation2016) while national culture is said to be capable of explaining variations in firm-level and country level in corporate governance (Duong, Kang, & Salter, Citation2016) and carbon disclosure (Le & Tang, Citation2016). When the institution is weak, it affects the effectiveness of corporate governance (Kumar & Zattoni, Citation2016). Also, competent corporate governance is capable of reducing information asymmetry (Kanagaretnam, Lobo, & Whalen, Citation2007).A good number of measures have been taken to strengthen corporate governance in both Nigeria and South Africa. In South Africa ranging from King report on corporate governance in 1994 (Rossouw, Van der Watt, & Malan, Citation2002; Vaughn & Ryan, Citation2006), to King III report (King Committee on Corporate Governance, Citation2009). In Nigeria, in 2003, the Artedo Peterside committee set up by the Securities and Exchange Commission, developed a code of best practice for public companies in Nigeria. We focused on board independence (BIND), board size, board meetings, audit committee independence, and environmental committee as corporate board characteristics, while the emphasis is on the assumption that BIND arrangement may serve as bonding mechanisms in weak reporting environments, suggesting a substitutive relationship between BIND and the regulatory framework.

2.3.1. Board independence

The stakeholder’s theory buttress the importance of having independent directors in board composition aimed at protecting the interest of the investors (Arayssi, Dah, & Jizi, Citation2016; Gul & Leung, Citation2004; Jizi, Salama, Dixon, & Stratling, Citation2013). Liao et al. (Citation2015) showed evidence of a positive association between significant independent directors and extensive disclosure of GHG information from a UK sample of 329 largest companies using both univariate and regression models. García-Meca and Sánchez-Ballesta (Citation2010) adopted a meta-analysis approach to a sample of 27 empirical studies to explain the association of corporate governance structure with voluntary disclosure. The study document “that positive association between BIND and voluntary disclosure only occurs in those countries with high investor protection rights.” Jizi et al. (Citation2013) stated that there exists a positive relationship between the upper level of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure and more independent boards of directors. The study was based on a sample of large US commercial banks. Eberhardt-Toth (Citation2017) also supported having more independent executive administrators on the board. Post, Rahman, and McQuillen (Citation2014) empirically investigated the association between board structure and company environmental performance using sustainability-themed alliances as a moderating variable and the whole public oil and gas companies as a sample. They found among others that the sustainability-themed alliances moderate dependent and independent variables. A higher percentage of independent nonexecutive directors on the board are expected to relate to extensive environmental impact disclosure significantly.

2.3.2. Board size

The large composition of the board is perceived to be capable of influencing the extent to which corporate entities disclose their activities in any environment (Haniffa & Cooke, Citation2005; Ntim & Osei, Citation2011). Bhagat and Bolton (Citation2008) supported by agency theory (John & Senbet, Citation1998) due to the diversity of expertise of members (Allegrini & Greco, Citation2011; Nan, Salama, Hussainey, & Habbash, Citation2010; Xie, Davidson, & Dadalt, Citation2003). Some of the studies conducted in both developed and developing countries revealed a positive association between board size and environmental impact disclosures (Andrikopoulos & Kriklani, Citation2013; Khlif et al., Citation2015) while some showed negative relationship Uwuigbe and Ajayi (Citation2011) and others insignificant result (Cheng & Courtenay, Citation2006; Halme & Huse, Citation1997). Recent empirical evidence from an emerging economy by Trireksani and Djajadikerta (Citation2016) examined the relationship between corporate governance variables and the extent of environmental disclosure. The study focused only on mining companies listed in Indonesia Stock Exchange and employed content analysis of the annual reports and documents a significant positive association between the board size and the extent of environmental disclosure. Osazuwa, Che-Ahmad, and Che-Adam (Citation2016) utilised a cross-section data of sample size of 116 firms in Nigeria and provided evidence that board size positively relates to the level of environmental disclosure. Concerned about the quality of climate change disclosure, Ben-Amar and McIlkenny (Citation2015) result from Canada showed a positive association between board effectiveness and the firm’s decision to answer the CDP questionnaire as well as its carbon disclosure quality. Bridging the gap in knowledge about the relationship between corporate governance and CSR in the banking sector of US, Jizi et al. (Citation2013) found a significant positive association between board size and CRS. Jizi et al. (Citation2013) used meta-analysis to a sample of 64 empirical studies to identify possible determinants to the relationship between board, audit committee characteristics and voluntary disclosure. The study acknowledged that board size has a significant positive effect on voluntary disclosure. We expect a significant positive relationship between environmental disclosure variables and corporate board size.

2.3.3. Audit committee independence

Audit committee independence is among the dimensions of measuring audit committee effectiveness (Pincus, Rusbarsky, & Wong, Citation1989). This committee is part of corporate governance structure (Cohen, Hoitash, Krishnamoorthy, & Wright, Citation2014; Cohen, Krishnamoorthy, & Wright, Citation2002; Vera-Muñoz, Citation2005; Yasin & Nelson, Citation2013) that helps in overcoming agency-related problems (Aburaya, Citation2012; Ho & Shun Wong, Citation2001; Islam, Citation2010) as well as carrying out oversight function (Beasley, Carcello, Hermanson, & Neal, Citation2009; Rahim, Johari, & Takril, Citation2015) must be independent (Vera-Muñoz, Citation2005). Based on this important role of audit committee in achieving objectives of corporate governance (Ho & Shun Wong, Citation2001; Khan, Muttakin, & Siddiqui, Citation2013; Said, Hj Zainuddin, & Haron, Citation2009), required a good number of independent members for its effectiveness (Akhtaruddin & Haron, Citation2010; Bouaziz, Citation2012; Carcello & Neal, Citation2000; DeZoort, Hermanson, Archambeault, & Reed, Citation2002; Ghafran & O’Sullivan, Citation2013; Mohamad & Sulong, Citation2010). Some empirical evidence has emerged about the degree of number of independent members in positively influencing what, how and when to disclose information that will help stakeholders to make an informed decision. Madi, Ishak, and Manaf (Citation2014) in a study of 146 Malaysian listed firms for the year 2009 provided evidence that audit committee independence is positively related to voluntary corporate disclosure. The study used a content analysis method. Madi et al. (Citation2014) is a confirmation of Iatridis (Citation2013). Also, Samaha, Khlif, and Hussainey (Citation2015) reported a positive relationship between the level of voluntary disclosure and the percentage of independent directors on the audit committee.

2.3.4. Board meetings

Vafeas (Citation1999) revealed that “board activity, measured by board meeting frequency, is an important dimension of board operations” which helps to overcome agency conflicts (Xie et al., Citation2003). Ntim and Osei (Citation2011) study the impact of corporate board meetings on corporate performance of 169 listed companies in South Africa and found a positive relationship. On the other hand, Kantudu and Samaila (Citation2015) reported negative association based on the study of the impact of monitoring characteristics on financial reporting quality of the Nigerian listed oil marketing firms. While in Nigeria, Osazuwa et al. (Citation2016) investigated the relationship between board characteristics and the extent of environmental disclosures. The study used cross-sectional data and quantitative design method and documents a negative relationship between board meetings and environmental disclosure.

2.3.5. Environmental committee

The environmental committee is saddled with the responsibility of assessing the natural capital (Council on Social Work Education, Citation2015; Pryor, Bierbaum, & Melillo, Citation1998; Rockwell, Citation1991; Sánchez & McIvor, Citation2007; Sano & Kawai, Citation1996; Stewart, Citation2004). An advisory committee (Vasseur et al., Citation1997) that has shown a high-level transparency towards the environment (Liao et al., Citation2015).However, the words of Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (Citation2009) that “…environmental committee do not reward environmental strategies more than those without such structures, suggesting that these mechanisms play a merely symbolic role,” call for more evidence on the relationship between the environmental committee and corporate environmental disclosure practices. Dixon-Fowler, Ellstrand, and Johnson (Citation2017) found a positive association between board environmental committees and corporate environmental performance. In agreement with agency theory, such committee will be proactive and not reactive in handling environmental issues and actions help companies gain environmental legitimacy (Berrone, Fosfuri, & Gelabert, Citation2015; Hummel & Schlick, Citation2016) and firm value (Clarkson, Fang, Li, & Richardson, Citation2013; Plumlee, Brown, Hayes, & Marshall, Citation2015) as well as beneficial to shareholders (Griffin & Sun, Citation2013).Peters and Romi (Citation2013b) reported a positive association between the environmental committee and environmental disclosure.

2.4. Corporate attributes (control variable)

Roberts (1992) pointed out the importance of company characteristics in investigating the level of corporate environmental disclosure. In this current study, the firm attribute is used as control variables as previously done by (e.g. Akbas, Citation2016). Therefore, we consider only three attributes- company size, industry membership, and auditor type.

2.4.1. Industry membership

The industry a company belongs is perceived to be a determinant factor of the quantity of environmental impact disclosure to the stakeholders. In a study by Halkos and Skouloudis (Citation2016) using a disclosure index, investigate the level of disclosure practices of the largest 100 firms operating in Greece, document among others that working in environmentally sensitive sectors has a positive association with climate change disclosure. The study used a logit regression method. This evidence supported an earlier study by Galani, Gravas, and Stavropoulos (Citation2012). On the contrary, Ong, Tho, Goh, Thai, and Teh (Citation2016) found that less environmentally sensitive industry disclosed more and higher quality of environmental disclosure than ecologically sensitive industries of Malaysia. The finding is not unconnected to the poor and weak legal environment as it relates to the environment (Ong et al., Citation2016). In Jordan, Ismail and Ibrahim (Citation2008) on the overall, found no significant relationship between industry type and the level of social and environmental disclosure. From the United Kingdom, Brammer and Pavelin (Citation2008) provided evidence to support that industry class relate to the extent of corporate disclosure of environmental information using a sample of 450 conglomerates selected from different sectors.

2.4.2. Firm size

Large companies exhibit higher disclosure as they have financial “muscle” to bear the cost. Various studies provided the empirical result relating the size of a company and the level of environmental disclosure. In China, Lu and Abeysekera (Citation2014); Zeng, Xu, Dong, and Tam (Citation2010) documented a positive significant relationship. Greek evidence shows that size is a strong determinant of environmental ratings (Galani et al., Citation2012). Adhikari and Tondkar (Citation1992) examined the relationship between selected environmental factors and stock exchange disclosure requirements of 35 stock exchanges in different countries and found that the size of the equity market significantly explained the variation. Chek, Zam Zuriyati, Nordin Yunus, and Norwani (Citation2013) used content analysis and Pearson correlation methodology and found the size of 154 companies in consumer and plantation industries of Malaysia to correlate with level disclosure. Having the desire to fill the gap in knowledge, Ismail and Ibrahim (Citation2008) provided evidence from Jordan a developing country. Using a sample of 60 companies in the manufacturing and service sectors, content analysis was employed. The study equally found a positive association between company size and level of environmental disclosure. Also from Thailand, Suttipun and Stanton (Citation2012) found a positive association. Evidence from developed country US showed a different result when company size and industry type were used as a control variable to determine the relationship between performance and disclosure for the 131 companies (Patten, Citation1992). Canadian experience as documented by Cormier and Magnan (Citation1999) showed that firm size significantly explain environmental disclosure. Also in UK, Brammer and Pavelin (Citation2008) reported a positive association.

2.4.3. Audit firm size

The reputation of an engaged external auditor is perceived to be an influencing factor in corporate environmental disclosure practices. As such complete disclosure enhances the audit firms reputation (Copley, Citation1991). Anchoring on this perception, Wang, Sewon, and Claiborne (Citation2008) provided evidence from China. The study showed that voluntary disclosure is related to the reputation of the auditor. Braam and Borghans (Citation2014) see the interlock ties between the board and the external auditor as a catalyst for voluntary corporate disclosure. From the point of ethical values, Houqe, van Zijl, Dunstan, and Karim (Citation2015) stated thus entities “from countries where ‘high corporate moral values’ prevail are more likely to hire a Big four auditor.” By extension, we expect “Big 4” auditor type to influence extensive corporate environmental disclosure in a strong legal environment, investor protection and disclosure standards (El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Pittman, Citation2016; Ernstberger & Grüning, Citation2013).

2.4.4. Research hypotheses

In cognisance of the theoretical and empirical evidence on the relationship between board characteristics and the extent of overall environmental disclosure. We state hypotheses for this study thus:

H1.

Corporate Environmental Disclosure Quantity is associated with corporate board characteristics in African emergent markets (South Africa and Nigeria).

H2:

Board Independence arrangement serve as bonding mechanism in the traditional reporting framework (Nigeria) and not in integrated reporting framework (South Africa) with the extent of corporate Environmental Disclosure Quantity

3. Research method

This current study used an archive data which call for ex-post facto research design to enable us to investigate the relationship between corporate board characteristics and environmental disclosure practices of listed companies in South Africa and Nigeria. The population of the study is listed companies of NSE and Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE). This population comprises of 188 and 360 companies listed on NSE and JSE, respectively. We eliminated companies that are either suspended or unavailability of the annual report for the year 2015. The 303 (Nigeria 90 and South Africa 213) companies formed the sample size for the study. The sample is made up of large and industrially diverse companies for possible generalisation of the findings (Aburaya, Citation2012; Brammer & Pavelin, Citation2006).

The study employed content analysis of annual reports which has been widely used by previous studies to investigate the extent of environmental disclosure by corporate entities (Akbas, Citation2016; Fallan, Citation2016; Hackston & Milne, Citation1996; Hughes, Anderson, & Golden, Citation2001; Khlif et al., Citation2015; Niskala & Pretes, Citation1995; Nor, Bahari, Adnan, Kamal, & Ali, Citation2016; Ong et al., Citation2016). In line with prior studies (Aburaya, Citation2012; Clarkson, Li, Richardson, & Vasvari, Citation2008; Cormier et al., 2011; Hackston & Milne, Citation1996), we developed a 35 checklist item (Appendix A) was used to measuring the extent (Aburaya, Citation2012; Odoemelam & Okafor, Citation2018). The annual report of the sample companies for the year 2015 was used for the investigation. This data is based on the annual reports which are the secondary source (Hussey & Hussey, Citation1997) of data collection that is widely accepted as credible (Al-Tuwaijri, Christensen, & Hughes, Citation2004; Neu, Warsame, & Pedwell, Citation1998; Tilt, Citation2001; Tilt & Symes, Citation1999).

Coding of the items to generate a data set is in line with (e.g. Gray, Kouhy, and Lavers (Citation1995); Aburaya (Citation2012)) based on a measure of disclosure volume by the scoring system. Despite the criticism that un-weighted index (dichotomous scores) of the 1 if the item is disclosed and 0, if not disclosed, negate the possibility that all the elements are not equally important (Barako, Hancock, & Izan, Citation2006),the un-weighted index is accepted for measuring quantity of entities environmental disclosure (Bozzolan, Trombetta, & Beretta, Citation2009) and previous studies have used dichotomous score (e.g. Aburaya (Citation2012); Haniffa and Cooke (Citation2005); Chau and Gray (Citation2002). Hence, we adopt the formula by Aburaya (Citation2012) and Odoemelam and Okafor (Citation2018) for calculating the quantity of environmental disclosure by the sample companies.

Corporate Environmental Disclosure Quantity Index for each company is computed according to the following equation:

n

CED Quantity = Σ Quantity

i = 1

MAX Quantity i

where:

CED Quantity = Corporate Environmental Disclosure Quantity Index,

Quantityi = 1 if item i is disclosed; 0 if item i is not disclosed,

MAX Quantity = maximum applicable disclosure quantity score,

n = number of items disclosed.

The study tests the hypotheses using a cross-sectional sample of companies (Cho, Roberts, & Patten, Citation2010) listed across South African and Nigerian stock exchange (www.jse.co.za and www.nse.com.ng)

3.1. Model specification

To achieve the purpose of examining the relationship between board characteristics and the extent of environmental disclosure, we follow Akbas (Citation2016) model using ordinary least square with cross-sectional data and as well as panel data technique to test the association. Therefore, the model for the study is specified thus:

where:

CEDQ: the overall of environmental disclosure of company ἱ

α0: intercept

BSIZE: board size of company ἱ

BIND: Board independence of company ἱ

BOMET: board meeting of company ἱ

ACOINDE: audit committee independence of company ἱ

ENVICOM: an environmental committee of company ἱ

SIZE: size of company ἱ

INDM: industry membership of company ἱ

AFS: auditor type of company ἱ

Ɛἱ: random error term

The apriori signs are β1 > 0, β2 > 0, β3 > 0, β4 > 0, β5 > 0, β6 > 0, β7 > 0, β8 > 0

The variables and their measurements are further explained in Table .

4. Result and discussion of findings

Results in this study are presented as follows. Firstly, the descriptive statistics table and analysis and followed by multivariate analysis and discussions of findings.

4.1. Descriptive analysis

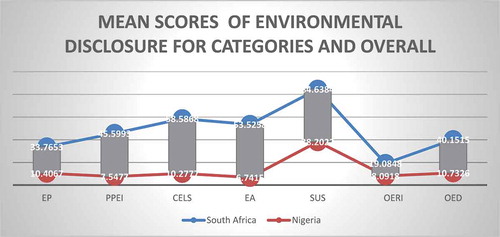

Table , panel A results show that environmental disclosures are more relevant in the South African sample and less in Nigeria sample. For, instance, the mean of overall environmental disclosure score accounts for 40% while in Nigeria the average for overall environmental disclosure amount to 10.7%. These results suggest that integrated reporting framework and regulatory environment stimulates the extent of environmental disclosure more than the opposite (Figure ).

Table 1. Measurement and explanation of variables

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Figure 1. Environmental disclosure means scores for South Africa and Nigeria (Appendix B).

Panel B of Table shows relevant information in this study. It reveals that 35% of South Africa sample firms have an environmental committee as one of their corporate board mechanisms, while 65% of the same sample size of South Africa have no environmental committee. Also revealed in this study with regard to the panel B of Table result is that in a stakeholder-oriented model such as South Africa (Khlif et al., Citation2015) environmentally sensitive industries are legitimately concerned towards the natural capital. For instance, 45% of the total sample size of South Africa belongs to environmentally polluting industries scored a mean of 48%, whereas, the less environmentally sensitive industries totalling 117 (55%) have a mean value of 33%. On the contrary, the same result for Nigeria is quite revealing and confirms the relatively weak reporting framework and environment the firms operate. Panel B, also, reveal that for Nigeria, environmentally sensitive industries demonstrate poor concern towards the environment with regard to their environmental reporting in the traditional annual reports. For instance, out of 90 firms, 46 (51%) are in the membership of environmentally sensitive industries but not surprising, their mean score is 9.5% while 44 (49%) number of less environmentally sensitive industries score higher mean of 12%. This outcome buttresses the point that in a weak reporting environment, less environmental polluting industries disclosed more than and higher quantity environmental information.

Audit firm size’s reputation theory was confirmed in the analysis in Panel B of Table . A total of 72% and 60% of South Africa and Nigeria samples engage the services of “Big4” and audit firm size demonstrated legitimatising their reputation. Audit firm size in Table statistically significantly influences overall environmental disclosure in both study countries. The result implies that in a poor and weak institution, audit firm reputation substitute for strong legal and regulatory framework.

Table 3. Model summary and ANOVAa

Table 4. Coefficients (overall sample)

4.1.1. Correlation matrix

The correlation matrix showed no presence of multicollinearity among the variables. The result is depicted on Appendix C.

4.1.2. Multivariate analysis

Table reports the results of multiple regressions

4.1.3. Testing of the overall multiple regression model fit

Testing of the overall multiple regression model fit, Muijs (2004) suggested that for a goodness of fit with an adjusted R square: < 0.1: poor fit; 0.11–0.3: modest fit; 0.31–0.5: moderate fit; >0.5: strong fit. However, Table reveals a statistically significant relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable, which according to Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (2011) it tells us that it is useful to proceed with our regression analysis, as it contains important results. Table reveals a coefficient of multiple determination (R square of 0.505 and an Adjusted R square of 0.492), which represents the proportion of the variation in CEDQ that is explained by the set of independent variables in this study. This implies that the independent variables jointly explain about 50% of the variation in CEDQ of quoted sample companies F-test has the capacity to assess multiple regression coefficients simultaneously. Hence, the F-statistic in Table above tests if the whole regression model framed in this study to test hypotheses is a good fit for the data. Observe that Table reveals that the independent variables jointly predict significantly the dependent variable, CEDQ (F-statistic (8.392) = 37.299, p-value < .05). These results simply indicate that the multiple regression model postulated in this study is a good fit for our data.

Also, Table indicates that South Africa sample has an Adjusted R square of 0.336, which represents the percentage of the variation in CEDQ that is explained by the set of independent variables in this study. The implication of this is that the independent variables together account for just about 33% of the change in CEDQ of quoted companies in South Africa. Note that the Adjusted R square is used here instead of the traditional R square because Adjusted R square reflects both the number of independent variables in the model and the sample size. While Nigeria sample result showed that Adjusted R square of 0.296, which represents the proportion of the variation in CEDQ that is explained by the set of independent variables in this study. This implies that the independent variables jointly explain 29% of the variation in CEDQ of quoted companies in Nigeria.

From Table , the model reveals that board characteristics statistically significantly (p = 0.000) associated with the extent of environmental disclosure of listed firms in South Africa and Nigeria. The results provide supporting evidence for the first conjecture H1; corporate environmental disclosure quantity (CEDQ) is associated with corporate board characteristics in African emergent markets (South Africa and Nigeria). The finding agrees with (e.g. Akbas, Citation2016; Beekes et al., Citation2016) that the model is significant in the model (whole sample, South Africa and Nigeria) considered. We, therefore, accept the H1.

Considering the whole sample of the study, the coefficients of the independent variables are given in Table in the unstandardised coefficients column. The intercept or constant is given as −23.397. It is important to state that the independent variables are calculated relative to each other rather than independent of each other. Hence, we say that, relative to each other, ENVICOM has the strongest positive effect (β = 14.621) on the level of CEDQ, and that this statistically significant (p-value = 0.000, which is stronger than 0.01 and 0.05). In the same vein, INDM (β = 8.214, p-value = 0.001), ADT (β = 6.496, p-value = 0.012), BSIZE (β = 1.269, p-value = 0.005), and ACOINDE (β = 0.185, p-value = 0.000), equally have significant effect on CEDQ. BIND has the lowest insignificant (p-value = 083, which is weaker than 0.05) positive effect (β = 0.135) on CEDQ; Several other independent variables have insignificant positive effect on CEDQ and they include BOMET (β = 0.454, p-value = 0.515) and SIZE (β = 0.721, p-value = 0.087).

Table presents the coefficients of the independent variables (South Africa) in the unstandardised coefficients column. ENVICOM has the strongest positive effect (β = 17.602) on the extent of CEDQ, (p-value = 0.000, which is stronger than 0.01 and 0.05). Followed by INDM (β = 8.938, p-value = 0.006), BSIZE (β = 1.263, p-value = 0.050), equally have significant effect on CEDQ. While, BIND (β = 0.029, p-value = .793), BOMET (β = −.021, p-value = .980), ACOINDE (β = 0.134, p-value = 0.195), SIZE (β = 1.338, p-value = 0.101), and AFS (β = 6.323, p-value = 0.087) have insignificant positive effect on CEDQ.

Table 5. Coefficients and significance (South Africa Sample)

Table presents the coefficients of the independent variables (Nigeria Sample) in the unstandardised coefficients column. BIND has the most significant positive effect (β = 0.220) on the extent of CEDQ, (p-value = 0.00, which is stronger than 0.01 and 0.05). BSIZE (β = 1.186, p-value = 0.023), AFS (β = 5.248, p-value = 0.036), equally have significant effect on CEDQ. While, BOMET (β = 1.194, p-value = .205), ACOINDE (β = .043, p-value = .494),ENVICOM (β = 3.215, p-value = 0.308),SIZE (β = 0.387, p-value = 0.267), and INDM (β = 1.569, p-value = 0.551) are statistical.

Table 6. Coefficients and significance (Nigeria Sample)

The results of the relationship between percentage of independent directors of the total number of directors on the board of a company (BIND) and CEDQ (whole sample, p-value = 0.08,South Africa, 0.79, and Nigeria, 0.00) in Tables , and respectively, provide supporting evidence for the second conjecture H2: BIND arrangement serve as bonding mechanism in the traditional reporting framework (Nigeria) and not in integrated reporting framework (South Africa) with the extent of CEDQ. The finding agrees with the view of (e.g. (Ernstberger & Grüning, Citation2013; Ntim, Citation2016) and tends to disagree with Jizi et al. (Citation2013) (whole sample, South Africa and Nigeria) considered. Hence, these results allow validating our H2.

4.2. Discussion of findings

The regression results showed the influence of selected corporate board mechanisms and firm attributes on the CEDQ. The result indicates that BIND which is statistically significant (p < 0.01) for Nigeria sample only. The superior result of BIND against South African listed firms provide evidence in support of the view of Ernstberger and Grüning (Citation2013) however, strong corporate governance arrangements may serve as bonding mechanisms in weak legal environments (traditional reporting framework), suggesting a substitutive relationship between corporate governance and the regulatory framework. It implies that the independent executive direct board as a dimension of a better-governed company ensures the reduction of information asymmetry (Ernstberger & Grüning, Citation2013; Ntim, Citation2016). The revelation implies that South African legal and regulatory framework is strong (Khlif et al., Citation2015) that compensate the level of South Africa environmental disclosure while the independent executive directors on board of listed firms in Nigeria substituted for the poor regulatory environment (Adegbite, Citation2015).

Based on the evidence, board size associated with the extent of environmental disclosure among listed companies in South Africa and Nigeria. The results agree with the findings of (Akbas, Citation2016; Haniffa & Cooke, Citation2005; Jizi et al., Citation2013; Ntim & Osei, Citation2011; Osazuwa et al., Citation2016) that board size influences the extent of environmental disclosure. The finding agrees that having a large board comprising a diversity of expertise (Nan et al., Citation2010) encourages more disclosure. We find that audit firm size influences the extent of corporate environmental disclosure. The result concurs with (Braam & Borghans, Citation2014).Hence, these results allow corroborating the results attained by Wang et al. (Citation2008), Copley (Citation1991), Braam and Borghans (Citation2014).

Moreso, South Africa’s estimated regression result indicates that environmental committee (ENVICOM) and industry membership (INDUM) are statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01) and (p ≤ 0.01), respectively. On the contrary, Nigeria’s estimated regression results show that both variables are statistically insignificant at (p > 0.05) for ENVICOM and (p > 0.05) for INDUM. The results of South Africa with regard to environmental committee and industry membership positive association to the extent of overall environmental disclosure were not surprising. South African companies are operating in a relatively strong legal environment and have a strong regulatory standard (i.e. Integrated reporting). The ENVICOM result from South Africa confirms the views of Liao et al. (Citation2015) & Council on Social Work Education (Citation2015). The findings agree with Dixon-Fowler et al. (Citation2017); Peters & Romi (2013) and gaining of environmental legitimacy Berrone et al. (Citation2015). Firms operating in a highly regulated and strong reporting environment is also enjoined to be proactive (Peters & Romi, 2012) in agreement with legitimacy theory. The result disagrees with the view of Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (Citation2009).

In the same vein, our findings show that environmentally sensitive industries in a strong reporting framework (South Africa) are legitimising their operations. South Africa’s results corroborate well the results reached by Halkos and Skouloudis (Citation2016), Galani et al. (Citation2012), Brammer and Pavelin (Citation2008) confirming that the presence of strong reporting framework institution associated with the occurrence of stakeholder activism (Darrell & Schwartz, Citation1997), upheld legitimacy theory.

However, on the contrary, disagree with Ong et al. (Citation2016). While environmentally sensitive industries result from Nigeria, agrees with Ismail and Ibrahim (Citation2008) that document insignificant relationship and Ong et al. (Citation2016) of low disclosure of environmentally sensitive industries that portrays poor and weak legal environment (traditional framework).

On the other hand, the coefficients for the variables audit committee independence; board meeting and firm size were not significant in both countries. This finding implies that these variables do not significantly influence the extent of environmental disclosure of listed firms in South Africa and Nigeria. These results negate the stakeholder’s theory which expects the presence of independent directors on the board to help to overcome information related problems (Aburaya, Citation2012; Ho & Shun Wong, Citation2001; Rahim et al., Citation2015) and larger firms to extensively disclose environmental information. The result on board meeting contradicts the earlier finding of Osazuwa et al. (Citation2016) in Nigeria and (Ntim & Osei, Citation2011) from South Africa. The result on company size does not match with the results achieved by Lu and Abeysekera (Citation2014); Zeng et al. (Citation2010); Galani et al. (Citation2012);Ismail and Ibrahim (Citation2008); Suttipun and Stanton (Citation2012); Cormier and Magnan (Citation1999); Brammer and Pavelin (Citation2008) as well as Chek et al. (Citation2013). Usually, companies having a big size are characterised by more transparency, less information asymmetry

5. Conclusions

The differences in respect to the mode of reporting system between the two leading African emerging economies allows us to distinguish between the extent at which corporate board mechanisms influence environmental disclosure quantity between the two countries South Africa and Nigeria. Our results are consistent with the conclusion that corporate board characteristics associate with environmental disclosure quantity in both countries, but emphasises centres on a substitutive relationship between BIND and the regulatory framework. The magnitude of the association in a relatively weak regulatory framework and that of strong reporting environment. Our results are robust for CEDQ for a country that has a strong institution and has implemented integrated reporting regulations. Moreover, the influence of BIND on environmental reporting suggests a substitutive relationship in a traditional reporting setting. While interestingly, our results reveal a great concern with regard to environmentally polluting industries and less environmentally polluting industries. Firms from the strong regulatory framework and are environmentally sensitive-industries are more inclined to disclose their environmental impact. While their counterpart firms from weak legal environment publish less environmental impact to stakeholders. This result is inconsistent with both the voluntary disclosure perspective and the legitimacy theory. Interestingly, companies that have environmental committee are more likely to publish their environmental responses. Furthermore, our results are based on the unique setting of the medium of disclosure, characterised by mandatory integrated reporting of environmental impact and voluntary disclosure of climate change-related issues. Therefore, we are constrained to cross-sectional content analysis and should be careful of generalising our specific results. Our results provide useful insight background information for future research and are also relevant for regulators and policymakers charged with environmental accounting. Our contribution to the literature is twofold. First, we shed further light on the substitutive relationship between BIND and the regulatory framework. Second, we contribute specifically to the environmental disclosure literature by showing—in the setting of different reporting framework—industry membership influences on environmental disclosure decisions vary. In Polluting-intensive industries, the mandatory disclosure perspective (integrated reporting) and the legitimacy perspective advanced in prior research appear to complement each other in a highly regulated country while our result extends prior study arguing that environmentally sensitive industries in the poorly regulatory country, voluntary disclosure perspective substitute legitimacy perspective.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Grace N. Ofoegbu

Grace N. Ofoegbu holds a Doctorate degree in Accounting and she is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Accountancy, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus, Nigeria. She is the current Head of Accountancy Department at the University for 2018/2019 academic year. In addition, she holds the professional certification of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria, a Fellow of the Institute. Her research interest includes Corporate Financial Reporting, Taxation, and Auditing.

Ndubuisi Odoemelam

Ndubuisi Odoemelam is currently carrying out Ph.D. research on the effect of accounting earnings of quoted Nigerian firms on economic growth of Nigeria, under the supervision of Prof. R G. Okafor.

Regina G. Okafor

Regina G. Okafor is a Professor of Accounting in the Department of Accountancy, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus, Nigeria. She is the current Dean of Faculty of Business Administration in the University of Nigeria .

References

- Aburaya, R. K. (2012). The relationship between corporate governance and environmental disclosure: UK evidence. Doctoral thesis Durham University..

- Adegbite, E. (2015). Good corporate governance in Nigeria: Antecedents, propositions, and peculiarities. International Business Review, 24(2), 319–330. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.08.004

- Adhikari, A., & Tondkar, R. H. (1992). Environmental factors influencing accounting disclosure requirements of global stock exchanges. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 4(2), 75–105. doi:10.1111/j.1467-646X.1992.tb00024.x

- Ahmad, A. (2015). Lobbying in accounting standards setting. Global Journal of Management and Business, 15(3), 1–36.

- Ahmed Haji, A., & Anifowose, M. (2017). Initial trends in corporate disclosures following the introduction of integrated reporting practice in South Africa. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18(2), 373–399. doi:10.1108/JIC-01-2016-0020

- Ajibodade, S. O., & Uwuigbe, U. (2013). Effects of corporate governance on corporate social and environmental disclosure among listed firms in Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 2(5), 76–92.

- Akbas, H. E. (2016). The relationship between board characteristics and environmental disclosure: Evidence from Turkish listed companies. South East European Journal of Economics and Business, 11(2), 7–19. doi:10.1515/jeb-2016-0007

- Akhtaruddin, M., & Haron, H. (2010). Board ownership, audit committees’ effectiveness, and corporate voluntary disclosures. Asian Review of Accounting, 18(3), 245–259. doi:10.1108/13217341011089649

- Allegrini, M., & Greco, G. (2011). Corporate boards, audit committees and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Italian listed companies. Journal of Management & Governance, 187–216. doi:10.1007/s10997-011-9168-3

- Al-Tuwaijri, S. A., Christensen, T. E., & Hughes, K. E. (2004). The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(5–6), 447–471. doi:10.1016/S0361-3682(03)00032-1

- Andrikopoulos, A., & Kriklani, N. (2013). Environmental disclosure and financial characteristics of the firm: The case of Denmark. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 20(1), 55–64. doi:10.1002/csr.1281

- Arayssi, M., Dah, M., & Jizi, M. (2016). Women on boards, sustainability reporting, and firm performance. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 7(3), 376–401. doi:10.1108/SAMPJ-07-2015-0055

- Baboukardos, D. (2017). Market valuation of greenhouse gas emissions under a mandatory reporting regime: Evidence from the UK. Accounting Forum. doi:10.1016/j.accfor.2017.02.003

- Barako, D. G., Hancock, P., & Izan, H. Y. (2006). Factors influencing voluntary corporate disclosure by Kenyan companies. Corporate Governance, 14(2), 107–125. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8683.2006.00491.x

- Beasley, M. S., Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., & Neal, T. L. (2009). The audit committee oversight process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(1), 65–122. doi:10.1506/car.26.1.3

- Beekes, W., Brown, P., Zhan, W., & Zhang, Q. (2016). Corporate governance, companies’ disclosure practices, and market transparency: A cross country study. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 43(3–4), 263–297. doi:10.1111/jbfa.12174

- Ben-Amar, W., & McIlkenny, P. (2015). Board effectiveness and the voluntary disclosure of climate change information. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(8), 704–719. doi:10.1002/bse.1840

- Berrone, P., Fosfuri, A., & Gelabert, L. (2015). Does greenwashing pay off? Understanding the relationship between environmental actions and environmental legitimacy. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2816-9

- Berrone, P., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2009). Environmental performance and executive compensation: An integrated agency-institutional perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 103–126. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.36461950

- Beyer, A., Cohen, D. A., Lys, T. Z., & Walther, B. R. (2010). The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2), 296–343. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.10.003

- Bhagat, S., & Bolton, B. (2008). Corporate governance and firm performance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(3), 257–273. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2008.03.006

- Bouaziz, Z. (2012). The impact of the presence of audit committees on the financial performance of Tunisian companies. International Journal of Management & Business Studies, 2(4), 57–64. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2003898

- Bozzolan, S., Trombetta, M., & Beretta, S. (2009). Forward-looking disclosures, financial verifiability, and analysts’ forecasts: A study of cross-listed European firms. European Accounting Review, 18(3), 435–473. doi:10.1080/09638180802627779

- Braam, G., & Borghans, L. (2014). Board and auditor interlocks and voluntary disclosure in annual reports. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 12(2), 135–160. doi:10.1108/JFRA-11-2012-0054

- Braam, G. J. M., Uit de Weerd, L., Hauck, M., & Huijbregts, M. A. J. (2016). Determinants of corporate environmental reporting: The importance of environmental performance and assurance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 129, 724–734. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.039

- Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Voluntary environmental disclosures by large UK companies. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 33(7–8), 1168–1188. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5957.2006.00598.x

- Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2008). Factors influencing the quality of corporate environmental disclosure. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17(2), 120–136. doi:10.1002/bse.506

- Carcello, J. V., & Neal, T. L. (2000). Audit committee composition and auditor reporting. Accounting Review, 75(4), 453–467. doi:10.2308/accr.2000.75.4.453

- Chau, G. K., & Gray, S. J. (2002). Ownership structure and corporate voluntary disclosure in Hong Kong and Singapore. The International Journal of Accounting, 37(2), 247–265. doi:10.1016/S0020-7063(02)00153-X

- Chek, I. T., Zam Zuriyati, M., Nordin Yunus, J., & Norwani, N. M. (2013). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in consumer products and plantation industry in Malaysia. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 3(5), 118–125. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/6849945/Corporate_Social_Responsibility_CSR_Disclosure_in_Consumer_Products_and_Plantation_Industry_in_Malaysia.

- Cheng, E. C. M., & Courtenay, S. M. (2006). Board composition, regulatory regime, and voluntary disclosure. The International Journal of Accounting, 41(3), 262–289. doi:10.1016/j.intacc.2006.07.001

- Cho, C. H., Roberts, R. W., & Patten, D. M. (2010). The language of US corporate environmental disclosure. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(4), 431–443. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2009.10.002

- Clarkson, P. M., Fang, X., Li, Y., & Richardson, G. (2013). The relevance of environmental disclosures: Are such disclosures incrementally informative? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 32(5), 410–431. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2013.06.008

- Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4–5), 303–327. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2007.05.003

- Cohen, J., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. M. (2002). Corporate governance and the audit process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(4), 573–594. doi:10.1506/983M-EPXG-4Y0R-J9YK

- Cohen, J. R., Hoitash, U., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. M. (2014). The effect of audit committee industry expertise on monitoring the financial reporting process. Accounting Review, 89, 243–273. doi:10.2308/accr-50585

- Copley, P. A. (1991). The association between municipal disclosure practices and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 10(4), 245–266. doi:10.1016/0278-4254(91)90001-Z

- Cormier, D., & Magnan, M. (1999). Corporate environmental disclosure strategies: Determinants, costs, and benefits. Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance, 14(4), 429–451. doi:10.1177/0148558X9901400403

- Council on Social Work Education. (2015). Committee on environmental justice. Retrieved from http://www.cswe.org/CentersInitiatives/Diversity/AboutDiversity/15550/79492.aspx

- Darrell, W., & Schwartz, B. N. (1997). Environmental disclosures and public policy pressure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 16(2), 125–154. doi:10.1016/S0278-4254(96)00015-4

- Deegan, C., & Blomquist, C. (2006). Stakeholder influence on corporate reporting: An exploration of the interaction between WWF-Australia and the Australian minerals industry. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(4–5), 343–372. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2005.04.001

- Depoers, F., Jeanjean, T., & Jérôme, T. (2016). Voluntary disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions: Contrasting the carbon disclosure project and corporate reports. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(3), 445–461. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2432-0

- DeZoort, F. T., Hermanson, D. R., Archambeault, D. S., & Reed, S. A. (2002). Audit committee effectiveness: A synthesis of the empirical audit committee literature. Journal of Accounting Literature, 21, 38–75.

- Dixon-Fowler, H. R., Ellstrand, A. E., & Johnson, J. L. (2017). The role of board environmental committees in corporate environmental performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(3), 423–438. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2664-7

- Duong, H. K., Kang, H., & Salter, S. B. (2016). National culture and corporate governance. Journal of International Accounting Research, 15(3), 67–96. doi:10.2308/jiar-51346

- Eberhardt-Toth, E. (2017). Who should be on a board corporate social responsibility committee? Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 1926–1935. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.08.127

- El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Pittman, J. (2016). Cross-country evidence on the importance of Big Four auditors to equity pricing: The mediating role of legal institutions. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 54, 60–81. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2016.03.002

- Ernstberger, J., & Grüning, M. (2013). How do firm- and country-level governance mechanisms affect firms’ disclosure? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 32(3), 50–67. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2013.02.003

- Fallan, E. (2016). Environmental reporting regulations and reporting practices. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 36(1), 34–55. doi:10.1080/0969160X.2016.1149300

- Galani, D., Gravas, E., & Stavropoulos, A. (2012). Company characteristics and environmental policy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21(4), 236–247. doi:10.1002/bse.731

- García-Meca, E., & Sánchez-Ballesta, J. P. (2010). The association of board independence and ownership concentration with voluntary disclosure: A meta-analysis. European Accounting Review, 19(3), 603–627. doi:10.1080/09638180.2010.496979

- Ghafran, C., & O’Sullivan, N. (2013). The governance role of audit committees: Reviewing a decade of evidence. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(4), 381–407. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00347.x

- Gray, R., Javad, M., Power, D. M., & Sinclair, C. D. (2001). Social and environmental disclosure and corporate characteristics: A research note and extension15. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 28(3), 327–357. doi:10.1111/1468-5957.00376

- Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995). Corporate social and environmental reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(2), 47–77. doi:10.1108/09513579510146996

- Greiling, D., & Grüb, B. (2014). Sustainability reporting in Austrian and German local public enterprises. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 17(3), 209–223. doi:10.1080/17487870.2014.909315

- Griffin, P. A., & Sun, Y. (2013). Going green: Market reaction to CSRwire news releases. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 32(2), 93–113. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2013.02.002

- Gul, F. A., & Leung, S. (2004). Board leadership, outside directors’ expertise and voluntary corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 23(5), 351–379. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2004.07.001

- Hackston, D., & Milne, M. J. (1996). Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in New Zealand companies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 9(1), 77–108. doi:10.1108/09513579610109987

- Halkos, G., & Skouloudis, A. (2016). Exploring the current status and key determinants of corporate disclosure on climate change: Evidence from the Greek business sector. Environmental Science & Policy, 56, 22–31. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.10.011

- Halme, M., & Huse, M. (1997). The influence of corporate governance, industry and country factors on environmental reporting. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13(2), 137–157. doi:10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00002-X

- Haniffa, R. M., & Cooke, T. E. (2005). The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(5), 391–430. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2005.06.001

- Hendri, S., & Puteri, K. (2015). Impact of corporate governance on corporate environmental disclosure: Indonesian evidence, International Conference on Trends in Economics, Humanities and Management (ICTEH’ 15), August 12 – 13, Pattaya (Thailand).

- Ho, S. S., & Shun Wong, K. (2001). A study of the relationship between corporate governance structures and the extent of voluntary disclosure. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 10(2), 139–156. doi:10.1016/S1061-9518(01)00041-6

- Houqe, M. N., van Zijl, T., Dunstan, K., & Karim, A. K. M. W. (2015). Corporate ethics and auditor choice—international evidence. Research in Accounting Regulation, 27(1), 57–65. doi:10.1016/j.racreg.2015.03.007

- Hughes, S. B., Anderson, A., & Golden, S. (2001). Corporate environmental disclosures: Are they useful in determining environmental performance?. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 20(3), 217–240. doi:10.1016/S0278-4254(01)00031-X

- Hummel, K., & Schlick, C. (2016). The relationship between sustainability performance and sustainability disclosure – Reconciling voluntary disclosure theory and legitimacy theory. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 35, 5. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2016.06.001

- Hussey, J., & Hussey, R. (1997). Business research : A practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students. Macmillan Business. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.ng/books/about/Business_Research.html?id=UVu1QgAACAAJ&redir_esc=y

- Iatridis, G. E. (2013). Environmental disclosure quality: Evidence on environmental performance, corporate governance and value relevance. Emerging Markets Review, 14, 1. doi:10.1016/j.ememar.2012.11.003

- Ienciu, I.-A., Popa, I. E., & Ienciu, N. M. (2012). Environmental reporting and good practice of corporate governance: Petroleum industry case study. Procedia Economics and Finance, 3, 961–967. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(12)00258-4

- Islam, M. Z. (2010). Agency problem and the role of audit committee : Implications for corporate sector in Bangladesh. Journal of Economics and Finance, 2(3), 177–189.

- Ismail, K. N. I. K., & Ibrahim, A. H. (2008). Social and environmental disclosure in the annual reports of Jordanian Companies. Issues in Social & Environmental Accounting, 2(2), 198–210. doi:10.22164/isea.v2i2.32

- Jizi, M. I., Salama, A., Dixon, R., & Stratling, R. (2013). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from the US Banking sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 601–615. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1929-2

- John, K., & Senbet, L. W. (1998). Corporate governance and board effectiveness. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(4), 371–403. doi:10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00005-3

- Kanagaretnam, K., Lobo, G. J., & Whalen, D. J. (2007). Does good corporate governance reduce information asymmetry around quarterly earnings announcements? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 26(4), 497–522. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2007.05.003

- Kantudu, A. S., & Samaila, I. A. (2015). Board characteristics, independent audit committee and financial reporting quality of oil marketing firms: Evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Finance, Accounting, and Management, 1(July), 34–50. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Khan, A., Muttakin, M. B., & Siddiqui, J. (2013). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 207–223. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1336-0

- Khlif, H., Guidara, A., & Souissi, M. (2015). Corporate social and environmental disclosure and corporate performance. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 5(1), 51–69. doi:10.1108/JAEE-06-2012-0024

- King Committee on Corporate Governance. (2009). Corporate and commercial/king report on governance for South Africa. King III Report. doi:10.1177/1524839909332800

- KPMG. (2013). The KPMG Survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2013: Executive summary. Kpmg, 1–20. www.kpmg.com/sustainability

- Kumar, P., & Zattoni, A. (2016). Institutional environment and corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24(2), 82–84. doi:10.1111/corg.12160

- Lan, Y., Wang, L., & Zhang, X. (2013). Determinants and features of voluntary disclosure in the Chinese stock market. China Journal of Accounting Research, 6(4), 265–285. doi:10.1016/j.cjar.2013.04.001

- Le, L. L., & Tang, Q. (2016). Does national culture influence corporate carbon disclosure propensity? Journal of International Accounting Research, 15(1), 17–47. doi:10.2308/jiar-51131

- Liao, L., Luo, L., & Tang, Q. (2015). Gender diversity, board independence, environmental committee, and greenhouse gas disclosure. British Accounting Review, 47(4), 409–424. doi:10.1016/j.bar.2014.01.002

- Lu, Y., & Abeysekera, I. (2014). Stakeholders’ power, corporate characteristics, and social and environmental disclosure: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 64, 426–436. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.005

- LYTON CHIYEMBEKEZO, C. H. I. T. H. A. M. B. O. W. . (2013). The extent and determinants of greenhouse gas reporting in the United Kingdom Doctor of Philosophy. Bournemouth University, (December).

- Madi, H. K., Ishak, Z., & Manaf, N. A. A. (2014). The impact of audit committee characteristics on corporate voluntary disclosure. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 164, 486–492. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.106

- Mohamad, W. I. A., & Sulong, Z. (2010). Corporate governance mechanisms and extent of disclosure: Evidence from listed companies in Malaysia. International Business Research, 3(4), 216–228. doi:10.5539/ibr.v3n4p216

- Nan, S., Salama, A., Hussainey, K., & Habbash, M. (2010). Corporate environmental disclosure, corporate governance, and earnings management. Managerial Auditing Journal, 25(7), 679–700. doi:10.1108/02686901011061351

- Neu, D., Warsame, H., & Pedwell, K. (1998). Managing public impressions: Environmental disclosures in annual reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23(3), 265–282. doi:10.1016/S0361-3682(97)00008-1

- Niskala, M., & Pretes, M. (1995). Environmental reporting in Finland: A note on the use of annual reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(6), 457–466. doi:10.1016/0361-3682(94)00032-Q

- Nor, N. M., Bahari, N. A. S., Adnan, N. A., Kamal, S. M. Q. A. S., & Ali, I. M. (2016). The effects of environmental disclosure on financial performance in Malaysia. Procedia Economics and Finance, 35, 117–126. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(16)00016-2

- Ntim, C. G. (2016). Corporate governance, corporate health accounting, and firm value: The case of HIV/AIDS disclosures in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Accounting, 51(2), 155–216. doi:10.1016/j.intacc.2016.04.006

- Ntim, C. G., & Osei, K. A. (2011). The impact of corporate board meetings on corporate performance in South Africa. African Review of Economics and Finance, 2(2), 83–103.

- Odoemelam, N., & Okafor, R. G. (2018). The influence of corporate governance on environmental disclosure of listed non-financial firms in Nigeria. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management, 2(1), 25–50. doi:10.28992/ijsam.v2i1.47

- Omer, M. E., & Andrew, C. W. (2014). The impact of corporate characteristics and corporate governance on corporate social and environmental disclosure: A literature review. International Journal of Business & Management, 9(9), 1–15.

- Ong, T. S., Tho, H. S., Goh, H. H., Thai, S. B., & Teh, B. H. (2016). The relationship between environmental disclosures and financial performance of public listed companies in Malaysia. International Business Management, 10(4), 461–467. doi:10.3923/ibm.2016.461.467

- Osazuwa, N. P., Che-Ahmad, A., & Che-Adam, N. (2016). Board characteristics and environmental disclosure in Nigeria. Information (Japan), 19(18A), 3069–3074.

- Ott, C., Schiemann, F., & Günther, T. (2017). Disentangling the determinants of the response and the publication decisions: The case of the carbon disclosure project. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 36(1), 14–33. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2016.11.003

- Otu Umoren, A., John Udo, E., & Sunday George, B. (2015). Environmental, social and governance disclosures: A call for integrated reporting in Nigeria. Journal of Finance and Accounting, 3(6), 227–233. doi:10.11648/j.jfa.20150306.19

- Patten, D. M. (1992). Intra-industry environmental disclosures in response to the Alaskan oil spill: A note on legitimacy theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(5), 471–475. doi:10.1016/0361-3682(92)90042-Q

- Peters, G. F., & Romi, A. M. (2013b). Does the voluntary adoption of corporate governance mechanisms improve environmental risk disclosures? Evidence from greenhouse gas emission accounting. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 637–666. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1886-9

- Pincus, K., Rusbarsky, M., & Wong, J. (1989). Voluntary formation of corporate audit committees among NASDAQ firms. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 8(4), 239–265. doi:10.1016/0278-4254(89)90014-8

- Plumlee, M., Brown, D., Hayes, R. M., & Marshall, R. S. (2015). Voluntary environmental disclosure quality and firm value: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 34(4), 336–361. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2015.04.004

- Post, C., Rahman, N., & McQuillen, C. (2014). From board composition to corporate environmental performance through sustainability-themed alliances. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(2), 423–435. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2231-7

- Prasad, M., Mishra, T., & Kalro, A. D. (2016). Environmental disclosure by Indian companies: An empirical study. Environment, Development, and Sustainability, 1–24. doi:10.1007/s10668-016-9840-5

- Pryor, D., Bierbaum, R., & Melillo, J. (1998). Environmental monitoring and research initiative: A priority activity for the committee on environmental and natural resources. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 51(1–2), 3–14. doi:10.1023/A:1005918527591

- Rahim, M. F. A., Johari, R. J., & Takril, N. F. (2015). Revisited note on corporate governance and quality of audit committee: Malaysian perspective. Procedia Economics and Finance, 28, 213–221. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01102-8

- Rensburg, R., & Botha, E. (2014). Is integrated reporting the silver bullet of financial communication? A stakeholder perspective from South Africa. Public Relations Review, 40(2), 144–152. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.11.016

- Rockwell, R. C. (1991). SSRC committee for research on global environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 1(3), 254–258. doi:10.1016/0959-3780(91)90047-W

- Rossouw, G. J., Van der Watt, A., & Malan, D. P. (2002). Corporate governance in South Africa. Journal of Business Ethics, 37(3), 289–302. doi:10.4102/sajim.v15i2.575

- Rupley, K. H., Brown, D., & Marshall, R. S. (2012). Governance, media and the quality of environmental disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 31(6), 610–640. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2012.09.002

- Said, R., Hj Zainuddin, Y., & Haron, H. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Social Responsibility Journal, 5(2), 212–226. doi:10.1108/17471110910964496

- Samaha, K., Khlif, H., & Hussainey, K. (2015). The impact of board and audit committee characteristics on voluntary disclosure: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing, and Taxation, 24, 13–28. doi:10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2014.11.001

- Sánchez, R. A., & McIvor, E. (2007). The Antarctic Committee for Environmental Protection: Past, present, and future. Polar Record, 43(3), 239–246. doi:10.1017/S0032247407006547

- Sano, T., & Kawai, K.-I. (1996). Activities of the JSTP Committee on environmental issues. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 59(3), 183–185. doi:10.1016/0924-0136(95)02129-9

- Stewart, K. L. (2004). The environmental enrichment committee. In ATLA Alternatives to Laboratory Animals, 32, 191–194.

- Suttipun, M., & Stanton, P. (2012). Determinants of environmental disclosure in Thai corporate annual reports. International Journal of Accounting and Financial Reporting, 2(1), 99. doi:10.5296/ijafr.v2i1.1458

- Tilt, C. A. (2001). The content and disclosure of Australian corporate environmental policies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 14(2), 190–212. doi:10.1108/09513570110389314

- Tilt, C. A., & Symes, C. F. (1999). Environmental disclosure by Australian mining companies: Environmental conscience or commercial reality? Accounting Forum, 23(2), 137–154. doi:10.1111/1467-6303.00008

- Trireksani, T., & Djajadikerta, H. G. (2016). Corporate governance and environmental disclosure in the Indonesian mining industry. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 10(1), 18–28. doi:10.14453/aabfj.v10i1.3

- Uwuigbe, U. O., & Ajayi, A. O. (2011). Corporate social responsibility disclosures by environmentally visible corporations: A study of selected firms in Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Management, 3(9), 9–17. Retrieved from www.iiste.org.

- Vafeas, N. (1999). Board meeting frequency and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 53(1), 113–142. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(99)00018-5

- Vasseur, L., Lafrance, L., Ansseau, C., Renaud, D., Morin, D., & Audet, T. (1997). Advisory committee: A powerful tool for helping decision makers in environmental issues. Environmental Management. doi:10.1007/s002679900035

- Vaughn, M., & Ryan, L. V. (2006). Corporate governance in South Africa: A bellwether for the continent? Corporate Governance: An International Review, 14(5), 504–512. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8683.2006.00533.x

- Vera-Muñoz, S. C. (2005). Corporate governance reforms: Redefined expectations of audit committee responsibilities and effectiveness. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-005-0177-5

- Votsi, N. E. P., Kallimanis, A. S., & Pantis, I. D. (2017). An environmental index of noise and light pollution at EU by spatial correlation of quiet and unlit areas. Environmental Pollution, 221, 459–469. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.12.015