Abstract

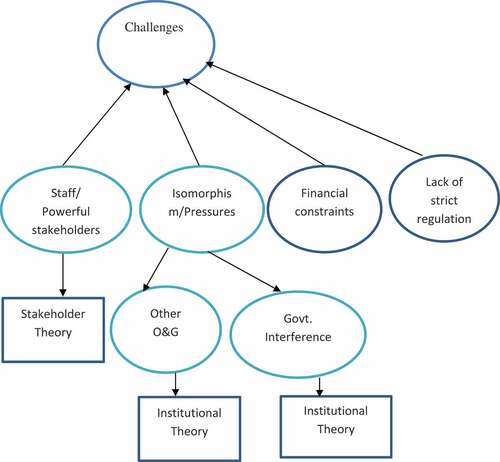

In recent times, firms and countries especially those in the developed economies are moving more into encompassing both voluntary and mandatory initiatives. This new initiative literature argues is relatively superior to the conventional voluntary initiatives prevalent in most developing economies. Although a catch for researchers, evidence from literature suggest that this interest has mainly been directed at finding the factors that encourage firms to engage in socially responsible investment (SRI) initiatives leading to a proliferation of extant literature. This notwithstanding, very little however exists on the Challenges Firms Face When Engaging In These SRI Initiatives Although Literature Gives An Indication Of Its Essence Especially Within Developing Economies. The Purpose Of This Study Is Thus To Explore The Challenges Faced By Oil And Gas Companies Especially In Developing Economies As They Engage In SRI By Delving Into The context-specific challenges they encounter. This is important as these SRI initiatives are seen to augment the efforts of governments within these developing economies. The study uses the interpretive multiple case study approach in achieving the objective of this tudy. The results of the study suggest that not only do the cases face peculiar challenges; undue government interference and financial constraints. But that the government whose effort they augment (with their SRI initiative) is a source of challenge. The findings also give an indication that some internal stakeholders (staff) form powerful stakeholder group that compound the challenges in engaging in SRI.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

With recent happenings within the oil and gas sector in sub-Saharan African countries including Ghana and how the oil finds in these nations have not benefitted these nations, this paper looks at the challenges the oil and gas firms face in trying to augment the efforts of Governments in providing the basic amenities through the socially responsible initiatives they undertake. This research has thus investigated the challenges that oil and gas firms listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange encounter in engaging in socially responsible initiatives. These challenges inhibit these oil and gas firms from helping governments in providing the needs of the citizenry. Data for this study were obtained from interviews and other archival documents. Although certain context-specific findings had been uncovered, what was interesting to note was how the government in itself served as a form of challenge to firms engaging in these socially responsible initiatives. The same government whose efforts these firms seem to complement.

1. Introduction

Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) activities look at the social, financial and environmental activities that firms engage in to take care of the enclave within which they operate. In other words, making sure that in undertaking their mandates as firms, the social as well as the environment they operate within in is in no way harmed. The activities these firms engage in are seen to be mostly voluntary (KPMG International, Citation2013). This remains mostly voluntary although some developed economies have moved towards its strict regulation. Its voluntary nature especially within the developing economies is because unlike financial accounting which is heavily regulated this is not (Deegan, Citation2017). This leads firms to engage in social and environmental activities at levels that best suits their needs.

Although these activities are not regulated in most developing economies, literature suggests that SRI initiatives are very necessary for these economies and they are done by firms to augment the efforts of government in providing basic needs, goods and services to its citizenry (Ablo, Citation2015; Ite, Citation2004). Because of this, the government of Ghana for instance, is seen to have brought about the Enterprise Development Centre to serve as a link between the government, local oil and gas firms and the Multinationals to ensure that they continually augment its efforts (Ablo, Citation2015). In taking care of the environment through SRI activities, firms face certain challenges. Their inability or failure to effectively solve these further worsens the plight of the citizenry.

Literature gives an insight into the challenges that firms face when engaging in SRI activities. These challenges being: lack of standardization due to lack of strict regulation, perceived notion and classification of firms and misrepresentation and misunderstanding of what SRI activities should entail (see Grougiou, Dedoulis, & Leventis, Citation2016; Hilson, Citation2012; Sethi, Martell, & Demir, Citation2017; Tomlinson, Citation2017). With the effects of these challenges being even more prevalent in developing economies (Brown & Fraser, Citation2006) because these developing economies contribute to more than half of the World’s GDP, with contributions coming mainly from natural resources in the form of oil and minerals (International Monetary Fund, Citation2013). These studies above however failed to give context-specific challenges that these firms face. They only give a broad classification of these challenges. Knowing the context-specific challenges are however more important since firms are different and countries are distinct from each other. In dealing with SRI challenges, context-specific problems must be identified by delving individually into the firms and their peculiar challenges.

Heightening the obvious lack of context-specific studies on SRI challenges the firms within the oil and gas sector face, Patten (Citation2015) exposes a deficiency in the methodological approach used in literature for SRI activities and challenges. He argued that SRI studies generally have variously identified causal relationships that hold on the average over a while but this has been far from being effective since researchers have resorted to proxies and measures that are available without properly testing their effectiveness and that future studies on SRI activities need in-depth look since every firm is distinct and that no two economies are the same. Studies on SRI like all other forms of social sciences in firms produce a reaction to situations and they are not bound by exact laws (Patten, Citation2015).

The problems indicated above are very critical for Ghana considering the fact that this industry is at a very young and developing stage, coupled with the current happenings within the oil and gas sector in Ghana. For instance, Ghana is classified as an oil exporter country but prices of oil and products had experienced continual increases to 5 Ghana Cedis (1 dollar) per liter, for the second pricing window in September 2018 (https://citibusinessnews.com/index.php/2018/09/15/fuel-prices-to-hit-5-cedis-per-litre/).

The International Energy Agency (IEA) also argued that although there has been some significant development in the power sector within sub-Saharan Africa within the last 5 years, Ghana is seen to be lagging behind as some 30% of her citizens still live without electricity. The government of Ghana opens the tender for six out of the nine oil blocks in its oil fields in a bid to increase the production of oil and gas in Ghana (https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Akufo-Addo-opens-tender-to-auction-six-oil-blocks-692613). If these challenges are not effectively addressed, there will not be any improvements made in this sector.

The aim of this paper is to find out the context-specific challenges that firms within the oil and gas sector in Ghana face when engaging in SRI activities. Apart from the extension in the scope of current literature, this paper also makes the following important contributions. First, this study seems to be the first of its kind that considers the context-specific challenges that oil and gas firms face in the SRI activities from the Ghanaian market perspective and one of the few from the developing economies perspective. Second, this paper will inform policymakers to implement strategies and policies that will help these firms to surmount the challenges they face in the SRI activities.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant existing literature. Section 3 discusses the methodology and the data used in arriving at the conclusions of this paper. Whilst Section 4 looks at the results and findings of this study, Section 5 looks at the discussions based on the results seen. Sections 6 and 7 talk about the contributions of the study and the conclusions drawn from the study, respectively.

2. Literature review

In identifying the challenges that firms encounter when engaging in SRI activities and in establishing the contributions and novelty of this study, extant literature has been reviewed. The literature review is organized into two main sections—theoretical literature and empirical literature. Whilst the empirical literature situates this study in what has been previously done and makes a case for the lack in already existing literature for which this study is imperative, the theoretical literature proposes the theory that this study has been situated. We begin with the theoretical principles underlying SRI and then follow it up with the relevant empirical literature.

2.1. Theoretical literature

There are several theories used in literature when dealing with SRI (either voluntary or mandatory). For the purpose of this paper, the stakeholder and the institutional theories have been discussed.

2.1.1. Stakeholder theory

The stakeholder theory is seen to have sprung up from the agency theory (Friedman, Citation1970). A stakeholder is one that has an interest in the affairs of a company. Investors, suppliers, governments, trade associations, and even the community are examples of the stakeholders of firms (Achim & Borlea, Citation2013). These stakeholders can be categorized under two main kinds. They are—primary and secondary stakeholders. The primary stakeholders are those whose lack of continuous involvement will lead to the company becoming extinct. Examples of these primary stakeholders are employees, customers, and suppliers. The secondary stakeholders are those that have less influence (have relative interaction and correspondence) on a company. Example the media.

Literature demonstrates that the stakeholder theory is one that came into being in the early 1980s with varied and unsettled history surrounding the coming into being of this theory (Clarkson, Citation1995). However, the work of Evan and Freeman (Citation1988) is said to be what gave firms focus and interest in the use of the stakeholder theory. From the work of Evan and Freeman (Citation1988), three ideas were extended. The first is that it is an extension of the shareholder theory (Freeman, Citation1999; Key, Citation1999). The second idea is that the stakeholder theory is anti-shareholder because it questions the assumption that profit maximization is the only and single mandate of firm Managers (Jensen, Citation2002). The third group, however, believes that the stakeholder theory is in to complement the shareholder theory (Heath & Norman, Citation2004).

This theory is seen to be useful in this paper as this study finds out that a stakeholder group (some workers) within one of the cases attitude towards the SRI initiative of their firm explain the threat and restraint part of the stakeholder theory. This is different from the class of stakeholders that exhibit this coercive power seen in the literature. Also, this theory is seen to help explain the conflicts that exist among these varied stakeholders as seen in the study by Tooley, Hooks, and Basnan (Citation2010).

2.1.2. Institutional theory

The institutional theory is traced traditionally to the works of Meyer and Rowan (Citation1977) and DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) and quiet recently to the study of Scott (Citation2001). The institutional theory explains why all organizations in a field tend to look and behave in the same way (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991). Institutional theory illuminates how organizations’ structure arises as a reflection of rationalized institutional rules. The main idea here is that organizational structures and processes tend to acquire meaning and achieve stability not on the basis of the effectiveness or the efficiency strategy they employ but from highly accepted and institutional rules. This theory looks at why companies respond to institutional pressures. DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) believed that what makes firms look similar are the processes, which they termed the isomorphism. The three institutional isomorphisms are the normative, mimetic, and coercive. Scott (Citation2001) believed that what makes firms look alike are the structures. He called these structures pillars. The three pillars are the regulative, normative, and cognitive structures.

The three institutional isomorphisms are therefore the building blocks to be used to explain the institutional theory. The isomorphism refers to the adaptation of an institutional practice by an organization which is the constraining force that makes firms within a population look alike with the same set of environmental conditions.

The normative isomorphism is the response to group norms and values because of an organization’s willingness to achieve the standards of professionalism. As a result, pressure mounts on an organization due to its membership of certain professional bodies. Mimetic isomorphism is an internal pressure on firms, rather than an imposed change. In other words, it is the response of the organization to uncertainty. Here the organization copies its competitors or other firms within their industry, by adopting the best practices. The third isomorphism which is the coercive stems from political influence. Firms feel pressured by political powers because of the issues of legitimacy.

No matter how similar organizations are from the outside, they will be totally different because organizations might not necessarily be faced with the same circumstances for them to look alike. So for firms to respond to ceremonial rules and actual internal efficiencies, they decouple (split) to enable the organization to maintain standardized, legitimate and formal structures while their activities vary in response to practical considerations and different situations.

The institutional theory is relevant in this research as it is seen to be used mainly in SRI studies. The reason for using this theory is because of its unique ownership characteristics of the firm (mainly foreign dominated). At the end of the study, we will be able to find out which of the isomorphism is applicable to the Ghanaian context and how it interplays because literature suggests that the institutional theory reacts differently within different economies even with similar ownership structures (Frumkin & Galaskiewicz, Citation2004; Verhoest, Verschuere, & Bouckaert, Citation2007)

2.2. Empirical literature

The empirical literature reviewed borders on SRI activities in the oil and gas sector and the challenges of SRI activities.

Although there is available literature suggesting that the oil and gas industry is one of the industries that championed the Social and Environmental Reporting agenda (Frynas, Citation2009), there is however no known date as to exactly when this took place. The Oil and Gas industry presents itself as an ideal industry to consider in SRI or Social and Environmental Reporting (SER) studies owing to the nature and impact of their operations on the environment. According to Scott (Citation2001), the oil and gas industry was the first industry to engage in SER because they wanted to retain their license for production and to be seen as being in the good books of the communities in which they operate. Hence, it is seen as an industry with a high rate of engagement in SER.

Studies that have been conducted on oil and gas firms with regard to SER present similar findings (Comyns & Figge, Citation2015; Raufflet, Cruz, & Bres, Citation2014; Alazzani & Wan-Hussin, Citation2013; Scott, 2000). The focus of these studies was how the effects of the activities of oil and gas firms could be minimized on the environment especially in developing economies. It was seen from the findings that when oil and gas firms engaged in SER, it led to transparency, credibility, and comparability of their reports. And that mining and oil and gas firms operate under different environments if they are located within the developed or developing economy. Hence, these firms face challenges when they engage in SER implementation due to the national or international environment, but this idea has not been properly explored.

The variations that exist in the CSR initiatives of the sampled companies in relation to countries with varying levels of stakeholder engagement also showed more commitment to environmental issues, through the discussions of policy and practice (Alazzani & Wan-Hussin, Citation2013). In showing what firms were disclosing in terms of their SER, it was realized that every year is distinct regarding what is reported on SER so there is the need for strict regulations guiding the activities of the firms. However, these studies failed to bring out the challenges that the firms face when dealing with SER with regard to oil and gas firms (Comyns & Figge, Citation2015).

Reporting on the social and environmental issues of firms is so important to the survival of firms that they are now seen as de facto laws for business. Organizations operating within the environment are required to be efficient by engaging themselves in activities which make them socially responsible. Being socially responsible requires that, an entity engages in some form of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities.

Firms within the mining, oil and gas industry face different challenges when engaging in SER. This is attributable to the differences in the economies they operate in (Raufflet et al., Citation2014).

Although the studies referenced above acknowledge that firms face challenges with regard to SER, due to national and international environments these firms operate in, very little is said or known about the actual challenges these oil and gas firms face. The mere existence of the problems due to international environment these firms operate in only reflects the issues and does not discuss them.

With regard to literature, on the challenges that oil and gas firms face when involved in SRI activities within firms, Bondy and Starkey (Citation2014) argued that the approach that a firm uses between the two (global and integrated) determines the nature and the type of challenges this firm will face and most importantly whether stakeholders and their view could be considered as a challenge in the SRI process. The global approach which was rather popular among the firms used in the study accommodated little or no stakeholder engagements since it ignores the local factors but only takes into consideration globally recognized best approaches. Some sort of best practice which is identified imposed on and implemented on all subsidiary firms. With the integrated approach, home or national cultures are factored into the process whilst the global approach ignores the local factors and only takes into consideration globally recognized best approaches. With the integrated, comments were incorporated from the beginning till the end.

Other issues discussed by implementation case studies are that within the extractive industry, SRI initiatives bordered on five main areas. These are environmental stewardship, community development, education, welfare, health and safety (Dobele, Westberg, Steel, & Flowers, Citation2014). It explores how companies with larger environmental impacts implement SER within their firms and the role of their stakeholders in helping to identify impediments during implementation. Although there had been earlier studies that had discussed the implementation of SER within firms, their study looked at achieving successful SER implementation by using strategies to win the trust of relevant stakeholders. All these issues translated into the firm withdrawing and taking control and orders from the head office where all the activities that pertained to SER were directed. They faced some problems because the local communities who initially had been in touch with the firm felt their issues on SER (which is) the direct impact of the firm’s activities on the environment were not taken into consideration. This led to conflicts because although the firm’s Head Office felt there were best practices in place to manage their SER impact on the environment, the stakeholders felt they did not work well. After the firm modified its strategy by bringing their physical presence into the community in which they operate as well as proper stakeholder engagements, things got better for the firm.

It is suggested that for effective SER implementation within firms, certain factors need to be critically looked at. These include the proper identification and prioritization of influential stakeholders, the identification of the relationship between the firms’ stakeholders, the need for internal commitment of management and employees to SER and the appointment of an SER champion. There is also the need for a local presence to facilitate community engagement, feedback and monitoring and the imperative to build trust and social legitimacy within the local community. Failure to look at these factors leads to challenges during the implementation process. Graafland and Zhang (Citation2014) however opined that in China, the challenges these local oil and gas firms face extend beyond stakeholder pressures from competitive multinational firms to high cost of engaging in SRI activities and the lack of resources in training appropriate people to take up SRI activities within the firms. And that the approach (global) used does not necessarily fit the Chinese context (Krueger, Citation2008) and that general challenges are rather focused on at the expense of looking out for context-specific challenges (Frynas, Citation2005; Ramasamy & Yeung, Citation2009).

While concentration has mainly been on the role or effects of stakeholder activities on the SRI initiatives, it is believed that this direction and focus are limited such that the stakeholder perspective might not necessarily be applicable in all environments (Maon et al., Citation2009) and what defines who is the powerful stakeholder is different for each firm and context. The lack of knowing and satisfying this condition equally leads to challenges in the SRI investment activities (Maignan, Ferrell, & Ferrell, Citation2005; Panapanaan, Linnanen, Karvonen, & Phan, Citation2003) stressed on the role of stakeholders and their concerns with regard to SRI implementation where the stakeholders were either seen providing input to the development of the SRI activities or stifling the progress being made.

A study on a developing economy (Nigeria) suggested that the challenges firms encounter depend on what they define as SRI and not all that fits as SRI activities for the developed economies will fit the developing economies (Amaeshi, Adi, Ogbechie, & Amao, Citation2006b). The study found out that the current meaning and practice of SRI in Nigeria is largely exploratory and does not present or adopt any normative stance (or “best practice” approach) towards the practice and meaning of SRI. It examines SRI as a neutral business practice (Amaeshi et al., Citation2006b). For instance, a private company with notice could terminate the employment of its employees at will and for no reason after giving due notice which is 1 month by statute and usually 3 months by contract. To the Researchers, this creates real challenges in adopting and implementing some western notions of SRI activities (i.e., responsible employee relations) in Nigeria and further questions the touting of CSR as a standardized global practice. They believe CSR activities in Nigeria could not be framed from a stakeholder perspective (or socialist model). Also, SRI implementation issues border on addressing socio-economic challenges of government (e.g., poverty alleviation, health-care provision, infrastructure development, education, etc.) and would be informed by socio‐cultural influences (e.g., communalism and charity). So they do not necessarily reflect the popular western standard or expectations (e.g., consumer protection, fair trade, green marketing, climate change concerns, socially responsible investments, etc.).

From the review of literature done above, these studies argue that the definition of what can be classified under SRI activities and the challenges they face depend on whether the firms are in the developed or developing economies and even beyond the economies, all firms are distinct from each other. As a result, the challenges these firms face are mainly context dependent. These gaps make a case for this study.

3. Research method

This section mainly discusses the research strategy, the inclusion strategy for the cases, the data collection process, how data were managed and analyzed, how the study has ensured that the data collected and findings are trustworthy and the ethical considerations of the study.

3.1. Research strategy: multiple interpretive case studies

This section discusses the interpretive case study approach that has been used in this paper to explore the challenges the oil and gas firms encounter when engaging in SRI activities, the processes and why it is the appropriate approach.

The interpretive case study approach does an in-depth explanation of the phenomenon and social behaviors. In this study, there has been an in-depth research into the challenges that these oil and gas firms encounter when engaging in SRI activities. Yin (Citation1994) defined the interpretive case study approach as a process that investigates phenomenon within real-life settings. While Yin (Citation1994) defines a case study as a process, Merriam (Citation1998) sees it as an end product.

Although an interpretive case study looks at only one case in a particular instance, a multiple case study approach is seen as the best way of looking at this phenomenon being investigated in this research. A multiple case study is the type of case study which involves collecting and analyzing data from several cases. The multiple case study approach is being used here because of its numerous advantages. First, there is more to be learnt from a multiple case study where a researcher gets a clearer understanding of whether a particular theory best suits the context or not. Hence, the robustness of a particular study is better tested with the use of the multiple case study approach (Yin, Citation1994). This is also affirmed by the study done by Bryman (Citation2008) who posited that with multiple case studies, theory building is one of the benefits likely to be derived from it.

3.2. Selecting the cases

The selection of the case firms began with a search of the firms classified as oil and gas firms based on the Ghana Stock Exchange’s classification of firms. The next consideration was whether these firms engage in SRI activities. The access to data and the theoretical interest of the researcher also played a key role in the selection of the firms. Whilst convenience and access to data were both important in the selection of the cases, the selection of cases was also dependent on the nature of the activities of the oil and gas firms which are the downstream and upstream. The final criterion in the selection of the case firms was the ownership structure of these firms. Most firms listed on the GSE are said to be mainly foreign owned (70%) and the rest being government owned (GSE, Citation2018). These parameters were established to ensure that only the cases with the relevant characteristics were included in this study. Three firms were ultimately chosen to form the cases.

3.3. Data collection process

In achieving the aim of this paper, data were sought from multiple sources, i.e., both primary and secondary sources. The primary data were obtained from the face to face semi-structured interviews and observation whilst the secondary data were obtained from archival documents. In total, 28 interviews were conducted with 12 different individuals during three separate visits. The first visit took place between May and July 2017, the second visit took place between January and March 2018 and the third visit took place between October and November 2018. The first visit was mainly to establish a rapport with the potential interviewees and lay the foundation for subsequent visits. The second visit was used to gather evidence on the context-specific challenges firms’ face when engaging in SRI activities and processes. The third visit was mainly for verbal feedbacks, follow-ups and clarification of emerging issues and patterns after the initial interviews had been analyzed. Appendices 1, 2, and 3 contain a list of the interviewees spread of the three visits.

The interviewees were from the three Manager levels (top-, middle-, and lower-Level managers) within the case firms. The views of these three different groups were sought from questions on what challenges they faced when engaging in their SRI activities. Although most of the interviewees were part of the SRI department and therefore knew the SRI activities within the firms, others had been part of the department in earlier years and still contributed to the SRI activities. The contributions of these people were equally important since they helped us to compare the challenges the firm encountered in previous years to what is happening currently.

The number of people chosen for the interviews was not predetermined. It was however determined mainly by the time constraints as well as the attainment of theoretical saturation (Fusch & Ness, Citation2015; Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017). The selection of a specific interviewee was equally guided by both theory and the research question posed. The sampling of the interviewees was therefore purposeful and not based on any theory (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994) since the selection was based on whether an individual is or was previously part of the department that handles SRI within the firms.

3.4. Data management and analysis

Since there are three firms representing the cases, analysis was done along two strands. That is the intra-case data analysis (where each firm was treated as a distinct entity) and the cross-case data analysis which helps in comparing across the three firms. The cross-data analysis helped to identify the similarities and difference that exist in the SRI initiatives of the three firms.

3.5. Trustworthiness of the data

To ensure that the data collected are credible, different groups of individuals were interviewed (from the three Manager levels) and different techniques (interviews, observation, and archival data as discussed early-on). Another way of ensuring that the data collected was credible was to send the transcribed data to the interviewees to ensure that their ideas had been fully captured.

3.6. Ethical consideration

The ethical considerations of this research are in line with three main principles. They are quality, autonomy, and confidentiality. With regard to quality, the researcher is qualified to undertake the study. The researcher is not a novice on the broad subject of environmental accounting. The researcher had served as a research assistant for 2 years to a lecturer whose research interest is in Environmental Accounting. The researcher had also attended some qualitative research training seminars.

With the second principle of Autonomy, in undertaking the research, the researcher ensured balance between the need for the human research and integrity. In this study, at no point was the researcher too powerful at the expense of the human integrity of the participants (to ensure balance of power between the researcher and the participants).

The third principle talks about Confidentiality which stipulates that the researcher cannot personally use the confidential data obtained neither should it be given to any third party. Practically, to ensure that the identities of the firms as well as the interviewees are protected, pseudonyms have been used. For instance, for the three case firms, they will be referred to as Firm 1, Firm 2, and Firm 3, respectively, while Manager 1, Manager 2, etc., represent the interviewees.

4. Results and findings

4.1. Intra-case data analysis

4.1.1. Overview of Firm 1

Firm 1 was initially founded as a private company in the early 1960s to deal in oil and gas products such as fuels, Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG), lubricants, bitumen, and other petroleum products in Ghana. In the early 1970s, the Government of Ghana acquired the shares of the smaller shareholders leaving the ownership of this firm in the hands of only two shareholders, namely, the government of Ghana and another shareholder. Firm 1 is a public listed company which was listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange in 2007. The annual reports from 2007 to 2017 show evidence of the activities this firm engaged in to meet the expectations of the firm, its customers and staff. Apart from the pictorial evidence in the annual reports, sub-sections of the annual reports of the firm also highlighted the SRI initiatives of the firm during the period under review with regard to its Environment, Economic (Operating) and Financial, Health, Safety, Security and Environment, Training and Corporate Social Responsibility.

4.2. Challenges faced by Firm 1 when engaging in SRI activities

SRI activities are associated with a plethora of challenges. Literature, however, shows evidence of broad external challenges. The researcher sought to find out the unique context-specific challenges faced by Firm 1 in the implementation of SRI. The fieldwork conducted in Firm 1 shows that they face a number of challenges during the implementation of SRI initiatives and are presented below.

Findings 1: Inadequate Financial Resources.

Analyses of the data gathered revealed that inadequate financial resource is one of the major challenges if not the most significant challenge they face in the implementation of SRI. The interviewees noted that they are usually overwhelmed by the requests they receive from the initial stages of the SRI development, implementation, and programs (community engagement). The interviewees unanimously noted these requests usually exceed their expectation and they pose significant challenges to them in selecting the projects to fund. One of the interviewees said the following:

“The requests we get are invariably 110times more than our budgets. Selecting even becomes a problem. Some of them have connections here and there and they pull all sorts of strings. If you are not firm and careful, all your budgets will be diverted away into frivolous and undeserving course.” (F1M4)

On this issue of inadequate funding, some of the interviewees decried the relative unforeseen cost. For instance, one of the interviewees said that:

“The fact that every site is unique is the challenge, where there is high water retention in the environment for instance, you will have to redesign and this comes with extra cost that hitherto might not have been envisaged”. There are new technologies though. Cost sometimes limits your ability to implement new and better technology. The company ensures that we engage in things that are safety oriented better than being penalized. It is better to do the right thing than being penalized to incur other costs.” (F1M3)

“With the issue of financing SRI, if you are not firm and careful, all your budgets will be diverted away into frivolous and undeserving course the issue of excess and unbudgeted costs is a problem sometimes” (F1M4)

“A couple of times they have drilled a bore hole as part of their SRI activities where the Ghana Standards Board in particular found the acidic content of the water not suitable and they had to do a lot of dips. In times like that, there will be delays and extra costs incurred by the firm. We had a case near Obuasi mine where they realized the water had not passed the test. We had to do several scientific things to make the water wholesome. That means extra cost. Fairly smooth process in his opinion except the hitches seen” (F1M1)

This finding deviated from the three broad/general challenges given in the literature as constraints on firms when engaging in SRI initiatives. The three are the lack of strict regulations to guide SRI (Hilson, Citation2012; Sethi et al., Citation2017), the perceived notion and classifications society gives to firms (Grougiou et al., Citation2016) and the misunderstanding of what SRI drivers and implementation entail (Tomlinson, Citation2017).

Findings 2: Government Interference

Another challenge faced by Firm 1 in SRI activities/initiatives is the influence of government in the activities of the firm. The interviewees also subtly highlighted the government’s influence or interference by the central government. The government’s influence or interference is highlighted in the remarks below:

“Some of them have connections here and there and they pull all sorts of strings and then you start receiving so much pressure and you are forced to implement those particular CSR projects” (F1M4).

Another said “it was the norm that government interferes in the activities and decision-making of the firm and that every government comes with its peculiar needs and sight of interest” (F1M6).

This seems interesting to note especially when government and the firm sees these initiatives by the firms to contribute to the provision of goods and services for the citizenry especially because the government lacks the financial strength and resources to provide all the needs of the citizenry.

4.2.1. Overview of Firm 2

Firm 2 is a multinational company. Its operation in Ghana started in the early 1960s and it was listed on the GSE in 1991 under a different name from what it uses currently. It is world-class oil, gas, and chemical group with industrial and commercial operations spanning oil, gas, power generation, renewable energies and chemicals. With regard to SRI initiative engaged in by the firm, although no specific mention is made of SRI, the annual reports and the interviews conducted give an indication that SRI initiative is paramount to the firm. Pictorial evidence can be seen on how the firm engages in Environmental, Social and Financial/Economic activities for the benefit of its customers, staff as well as the communities they engage in. Apart from the pictorial evidence, other sub-sections within the annual reports discuss the economic environment, financial and operational performance, and corporate social responsibility matters.

4.3. Challenges faced by Firm 2 when engaging in SRI activities

The development and initiatives of SRI are inundated with a number of challenges. The interviewees within Firm 2 have identified the ones they face in their bid to engage and implement SRI within the firm. These challenges have been identified in the sections below.

Finding 1: Lack of Adequate Resources

The interviewees unanimously highlighted the lack of adequate funding as one of the major impediments. Most of the SRI initiatives undertaken usually require or involve relatively significant capital outlay. Also, since inflation in Ghana has been rising over the past few years, price changes and price hikes lead to the fall in the value of available funds in the discharge of their activities. The interviewees noted that unforeseen and unbudgeted costs are major issues. They had the following to say:

“Last year a project we were embarking on a borehole, we sunk the borehole and we will go back this year to complete it. In some preceding year, school building project with a playground but the funds were not enough so we had to only put up the school building and the playground the following year. Because it was part of the proposal we showed to the community” (F2M1)

“I think that the cost used to be our issue. I don’t know if it still is though. You see when funds are allocated at the beginning of the year, we are in Ghana. Inflation on goods and service can be crazy sometimes. So when prices increase, we would now make memos and send back and forth until the funds are released. I remember in 2008 or so, our department had to fund the difference through no fault of ours. It puts so much strain on our budget for the year, wastes time, slows down projects and all” (F2M2)

“I sincerely wish our local Board has better role and authority. They know exactly what is going on and thus in a better position to direct and take decisions. But that is solely in the hands of our Headquarters. We contribute 50% of the project, sometimes there are unforeseen costs that might not have been captured in the local budget and we have to bear them. Also, the changes in prices of goods and services, contribute to this unforeseen costs” (F2M3)

Finding 2: Undue Government Interference

Although the ownership of Firm 2 is largely foreign, the interviewees also noted that the interference of government or government agencies was another major impediment to the effective implementation of SRI projects within the firm. These interferences they argue often come in the form of project specifications which may not be consistent with initial project design or objective. For instance, one of the interviewees said the following:

“Some few years ago, when we put up a classroom block with the sole aim of enhancing primary studies, government comes in through the GES and says it must be given to JSS studies. Some of these things create problems for us” (F2M1)

Finding 3: Lack of Commitment

Apart from cost, the interviewees also argue that the lack of full commitment from other workers is also a challenge they encounter when implementing SRI within their firm. They argue that from the identification to actual initiatives or activities, the input and commitment from all the staff within the different sectors or departments of the firm other than the SRI department are required. The interviewees unanimously argue that they do not receive the full support from these people mostly due to the fact that the output from the implementation does not directly affect their performance. To emphasize this challenge, the interviewees had this to say:

“Internal politics and apathy of work from other internal workers/Lack of cooperation from some Engineers who are also internal workers feel at a particular time in the year there is pressure to achieve targets that will determine their output instead of working on building schools that will benefit communities and not them personally” (F2M1)

“You know sometimes when people in our firm are not the ones that undertake SRI they are not really bothered and supportive and not on-time in performing their duties. Waste of time is also an issue sometimes “ (F2M3)

“ … it put so much strain on our budget for the year. Wastes time, slows down projects and all. Eii [interviewee screams] almost forgot” (F2M2)

This lack of commitment from the workers in the other departments could be attributed to the fact that these people deem themselves as a section of powerful stakeholders whose needs should be met for the smooth running of the firm. This attitude could also be attributable to lack of proper education. In order words, the mission and vision of the firm have not been carved to see the essence of SRI and its implementation within the firm. Also, there has not been proper communication of it within the firm. When the staff of a firm are not enthused or do not see the importance of SRI within their firm, they do not work effectively to ensure its success.

Finding 4: Bureaucratic Procedures

Aside the above-listed challenges, the interviewees also highlighted the bureaucracies involved in the making of decisions and with the implementation of SRI. As indicated above, SRI decisions of Firm 2 are centralized. The global Head Office makes the final decision regarding the project to be undertaken in a given period. This, according to the interviewees creates unnecessary delays and frustrations. To this, the interviewees had the following to say:

“Sometimes it takes up to six months for approval of SRI projects identified to be accepted by the Head Office whilst there is a local Board in Ghana that better know the conditions that are pertinent in Ghana (a case of the Jirapa). It is more frustrating especially you know all the stress you go through so these unnecessary bureaucracy, pressures and threats from the Head Office to retrieve the 50% of their sponsorship.” (F2M1).

“ … this militates against the smooth and effective implementation of SRI projects and it leads to delays in project implementation.” (F2M2).

4.3.1. Overview of Firm 3

Firm 3 is a multinational company that is present in almost all the continents in the world. In Ghana, it is the only firm currently involved in the actual drilling of oil (upstream) as the others have just began with the process of permit for drilling. Firm 3 was listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange in 2011 after it went through all the necessary processes needed for drilling oil. A dig into the annual reports of Firm 3 (2011–2017, since they listed in 2011) shows that the firm has been factoring a shadow carbon cost into their investment decisions. This is because Firm 3 as at now is strictly an off-shore firm and thus has not started with any on-shore activities in Ghana yet. In as much as the Annual Reports do not in any place explicitly state the firm’s engagements in SRI, there are some sections within the Report that show the firm's engagement in SRI. The annual reports mention what the firm does with regard to sustainability. A look at the annual reports for instance for 2017, indicated a section on Committed Mutual Benefits with a sub-section named Socioeconomic Investments. This is to ensure the mutual benefits of the firm and its host nations or communities.

4.4. Challenges faced by Firm 3 when engaging in SRI activities

The implementation of SRI is associated with a plethora of challenges. The researcher sought to find out the unique context and specific challenges faced by Firm 3 in the implementation of SRI. The challenges highlighted by the interviewees are presented in the sections below.

Findings 1: Delays in SRI project execution due to the absence of strict regulation and standardization.

The interviewees indicated that the absence of adequate regulation and standardization in the industry is a challenge to the effective implementation of SRI initiatives. The interviewees observed that:

“ … . well fortunately for us we have adequate financial resources to implement identified SRI projects in the year. … [Interviewee smiles] you know us already we have the money. The only challenge that comes to mind is what I term a lack of standardisation of these [SRI] initiatives. Sometimes we wished there is some form of regulation and standardisation in this space. To be utterly frank with you we can actually do more than what we have done so far. This issue is with the introduction of the EIA we [Firm 3] identify the projects we want to undertake or implement. The identified projects seen under our SEI are then submitted to the EPA to assess the impact of the project and give us the go ahead. More often than not the approval of the EIA takes an unreasonably long time. I recall instances where midway through the project implementation, the government [EPA] comes back to tell us that the project will not yield the desired impact it ought to. So we are forced to undertake additional projects. Sometimes we wish the government [EPA] acts proactively. We expect the government to provide details of their expectations so we are aware of what is expected of us by setting rules on how they want it done right from the onset to enable us make adequate preparations towards it. This arrangement sometimes leads to unnecessary delays in project execution.” (F3M1)

“The only challenge I point to is the fact that we have to take the initiative. We are always ahead of the state institutions or agencies. We have to perform impact assessment of our operations on the environment and communities we operate in and develop programmes to ameliorate adverse impact of our operations on the environment. We wish the appropriate state agencies will be more active in the Environmental Impact Assessment and projects that are undertaken to reduce or compensate the people for the impact of our operations. Sometimes the state agencies seem interested in the environmental impact of SRI projects half way through project implementation. This can sometimes be a bit frustrating” (F3M2)

4.5. Cross-case data analysis

The development and implementation of SRI could be fraught with a plethora of challenges that could stifle the effective implementation of SRI initiatives and achievement of SRI goals. The interviewees of the study highlighted a considerable number of challenges they encounter in the implementation of SRI initiatives. Some of the challenges highlighted by the interviewees were similar to those identified by interviewees from other firms. The challenges highlighted by the interviewees include inadequate financial resources, undue government interference, bureaucratic procedures, lack of commitment by personnel of the organization and standardized regulation.

Whereas Firm 1 and Firm 2 highlighted inadequate financial resources as one of the major obstacles to implementing the SRI initiatives, Firm 3’s major challenge is the seeming lack of standardized regulation in the SRI space of the industry. The interviewees argued that the government does not have specific mandatory rules for them to abide by when they engage in SRI. However, they are required to submit their Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) to the government through its agencies. What the firm submits is what the government uses as a mandatory tool in guiding their SRI initiatives. This is a challenge because the firm determines through their own analysis what must go into the EIA. When both firms are compared, the content of their EIA will be different. After the government is satisfied with what has been provided in the EIA, it then becomes a mandatory law for the firms. Failure to comply with the dictates of the EIA results in the firm being punished. According to the interviewees in Firm 1 and Firm 2, these inadequate financial resources result in delays in the implementation of SRI initiatives or projects. These interviewees in Firms 1 and 2 further highlighted government interferences as a major impediment in the implementation of SRI projects. The government’s interference is in the form of project selection of SRI projects and SRI project specifications. This challenge was however not highlighted by the interviewees in Firm 3.

The differences in the challenges faced by these firms could be attributed to the differences in the level of operation. Firms 1 and 2 operate in the downstream of the oil and gas industry, whereas Firm 3 operates in the upstream of the industry. This suggests that the firms operating at varied streams of the industry face varied challenges and firms operating at the same level or stream of the industry also encounter similar challenges in the implementation of SRI initiatives.

5. Discussions

The downstream foreign-owned firm (Firm 2) has no autonomy in their implementation choice and process because it relies on its parent company for some financial assistance in the implementation of its SRI practices and it is therefore compelled by the parent company to do what they require by way of their SRI practices. Although they engage in some sort of stakeholder engagements, they place little premium on this stakeholder engagement and rather go by the dictates of the parent company. The dependence on the parent company or corporate Headquarters for financial assistance in implementing the SRI practices is what leads to the financial challenges faced by the firm. It also renders the local Board of Directors who are supposed to take decisions such as the implementation approach and its timing powerless. This shows some level of weaknesses in the corporate governance system for listed firms. Herein, whilst all stakeholders of the firm including Regulatory agencies in Ghana believe the firm practices good corporate governance because of the existence of the Board of Directors mandated with the daily running of the firm, in reality, the decisions with regard to SRI are taken and manned by the parent firm or global Headquarters. The role of the local Board of Directors is only a ceremonial role.

The results of this study also show that as stated in the literature, firms react differently to different sets of stakeholder pressures and this influences the choice of their SRI implementation approach selected (Perez-Batres, Doh, Miller, and Pisani (Citation2012)). However, whether an influence is succumbed to, is dependent on the type and intensiveness of the stakeholder pressures and whether these stakeholders provide finances. To this end, this study finds that not all stakeholders apply equal pressure and not all firms respond in the same fashion to these pressures on the process and implementation of the SRI approach. The firm yields to these pressures especially when finances come from these stakeholders.

6. Contributions of the study

The findings of this study have a significant impact on research. This study and its findings contribute to the emerging literature on SRI within the oil and gas sector from the chosen context. First, it will serve as a reference point for future studies as the majority of the world’s deposits in oil and other natural resources are seen to be in developing economies. Secondly, this study is also novel and unique as it brings out the context-specific challenges these firms face with their SRI practices as opposed to the general challenges discussed in the literature. This shows that although the firms are within Ghana, what inhibits their engagement in SRI practices are however distinct.

The findings of this study give some beneficial policy directions. It proposes that policymakers come up with standardized regulations for SRI practices for listed firms as there is none currently since they solely rely on the EIA whose outcomes are different among these oil and gas firms. The lack of cohesion and standardization should push policymakers to ensure that SRI is well regulated soon as done or practiced in other developed economies. Specifically, the Ghanaian government should consider not only the churning out of guidelines but how to make it standardized and enforceable by putting in policies and strategies since the legally enforceable ones are seen to have been effective in other jurisdictions. In the same vein, the loopholes within the SRI space and lapses in the corporate governance structures of these listed firms should be properly identified and dealt with.

7. Conclusions

This study found out that when firms are striving to implement SRI initiatives within their firms, they encounter certain challenges. This study has identified firm-specific challenges which are pretty distinct from the broad or general challenges mainly seen in the literature.

The findings of this study interestingly reveal that although a couple of firm-specific challenges have been identified, the major one for Firms 1 and 2 has to do with financial inadequacies or challenges. However, this has not been the case of Firm 3. The interviewees argue that their major challenge has to do with the fact that the regulatory bodies do not have a well spelt out codified laws for guiding SRI but rather the regulatory agencies take the EIA submitted to them and make what the firm has stated mandatory. They argue that this sometimes leads to back and forth delays with these regulatory agencies. For example, two different firms will state totally different things in their EIA but what is binding on them is different so punishment for non-compliance also will be different. This could have been easily avoided if the Regulatory agencies bring out laws that the firms will comply with. This finding is quite different from what literature says about the countries that engage in mandatory SRI initiatives.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mawuena Akosua Cudjoe

Mawuena Akosua Cudjoe is currently a final year PhD student at the Putra Business School, Malaysia. Prior to enrolling for the PhD programme, she was a Graduate Assistant at the University of Ghana Business School. Her research interests are in Sustainability, Corporate Governance and Auditing.

Ahmed Razman Abdul Latiff

Ahmed Razman Abdul Latiff is an Associate Professor at the Putra Business School. He holds a PhD in Corporate Governance from Liverpool John Moores University. His research interests include corporate governance and ethics, contemporary issues in accounting, finance, entrepreneurship and human governance.

Nor Aziah Abu Kasim

Nor Aziah Abu Kasim is currently an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Putra Malaysia. She holds a PhD in Management Accounting from the University of Manchester. Her research interests include change management in organisations.

Mohammad Noor Hisham Bin Osman

Mohammad Noor Hisham bin Osman is a Senior Lecturer in Accounting at the Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Putra Malaysia. His research interests include corporate governance and audit quality, with focus on going-concern audit opinion.

References

- Ablo, A. D. (2015). Local content and participation in Ghana’s oil and gas industry: Can enterprise development make a difference? The Extractive Industries and Society, 2(2), 320–18. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2015.02.003

- Achim, M. V., & Borlea, N. S. (2013). Corporate governance and business performances. Modern approaches in the new economy, LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, Germany.

- Alazzani, A., & Wan-Hussin, W. N. (2013). Global reporting initiative’s environmental reporting: A study of oil and gas companies. Ecological Indicators, 32, 19–24. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.02.019

- Amaeshi, K. M., Adi, B. C., Ogbechie, C., & Amao, O. O. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in Nigeria: Western mimicry or indigenous influences? Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 24, 83–100. doi:10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2006.wi.00009

- Bondy, K., & Starkey, K. (2014). The dilemmas of internationalization: Corporate social responsibility in the multinational corporation. British Journal of Management, 25(1), 4–22. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00840.x

- Brown, J., & Fraser, M. (2006). Approaches and perspectives in social and environmental accounting: An overview of the conceptual landscape. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15, 103–117. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0836

- Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117. doi:10.5465/amr.1995.9503271994

- Comyns, B., & Figge, F. (2015). Greenhouse gas reporting quality in the oil and gas industry: A longitudinal study using the typology of “search”,“experience” and “credence” information. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 28(3), 403–433. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-10-2013-1498

- Deegan, C. (2017). Twenty-five years of social and environmental accounting research within critical perspectives of accounting: Hits, misses and ways forward. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 43, 65–87. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2016.06.005

- DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. doi:10.2307/2095101

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (Eds.). (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (Vol. 17). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Dobele, A. R., Westberg, K., Steel, M., & Flowers, K. (2014). An examination of corporate social responsibility implementation and stakeholder engagement: A case study in the Australian mining industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23(3), 145–159. doi:10.1002/bse.1775

- Evan, W. M., & Freeman, R. E. (1988). A stakeholder theory of the modern corporation: Kantian capitalism.

- Freeman, R. E. (1999). Divergent stakeholder theory. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 233–236.

- Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits/M. Friedman/The New York Times Magazine.

- Frumkin, P., & Galaskiewicz, J. (2004). Institutional isomorphism and public sector organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 14(3), 283–307. doi:10.1093/jopart/muh028

- Frynas, J. G. (2005). The false developmental promise of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from multinational oil companies. International Affairs, 81(3), 581–598. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00470.x

- Frynas, J. G. (2009). Corporate social responsibility in the oil and gas sector. The Journal of World Energy Law & Business, 2(3), 178–195. doi:10.1093/jwelb/jwp012

- Fusch, P. I., & Ness, L. R. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 20(9), 1408–1416.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Graafland, J., & Zhang, L. (2014). Corporate social responsibility in China: Implementation and challenges. Business Ethics: A European Review, 23(1), 113–135. doi:10.1111/beer.12036

- Grougiou, V., Dedoulis, E., & Leventis, S. (2016). Corporate social responsibility reporting and organizational stigma: The case of “sin” industries. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 905–914. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.06.041

- GSE. (2018). Internal memo: Listed firms’ reactions to CSR.

- Heath, J., & Norman, W. (2004). Stakeholder theory, corporate governance and public management: What can the history of state-run enterprises teach us in the post-Enron era? Journal of Business Ethics, 53(3), 247–265. doi:10.1023/B:BUSI.0000039418.75103.ed

- Hilson, G. (2012). Corporate social responsibility in the extractive industries: Experiences from developing countries. Resources Policy, 37(2), 131–137. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.01.002

- International Monetary Fund. (2013). World Economic Outlook, hopes, realities and risks World Economic and Financial Surveys.

- Ite, U. (2004). Multinationals and corporate social responsibility in developing countries: A case study of Nigeria. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 11(1), 1–11. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1535-3966

- Jensen, M. C. (2002). Value maximization, stakeholder theory, and the corporate objective function. In Business ethics quarterly (pp. 235–256).

- Key, S. (1999). Toward a new theory of the firm: A critique of stakeholder “theory”. Management Decision, 37(4), 317–328. doi:10.1108/00251749910269366

- KPMG International. (2013). The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting.

- Krueger, D. A. (2008). The ethics of global supply chains in China–Convergences of East and West. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(1–2), 113–120. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9393-5

- Maignan, I., Ferrell, O. C., & Ferrell, L. (2005). A stakeholder model for implementing social responsibility in marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 39(9/10), 956–977. doi:10.1108/03090560510610662

- Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Swaen, V. (2009). Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 71–89. doi:10.1007/s10551-008-9804-2

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publisher.

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. doi:10.1086/226550

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park: Sage.

- Panapanaan, V. M., Linnanen, L., Karvonen, M. M., & Phan, V. T. (2003). Roadmapping corporate social responsibility in Finnish companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(2–3), 133–148. doi:10.1023/A:1023391530903

- Patten, D. M. (2015). An insider’s reflection on quantitative research in the social and environmental disclosure domain. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 32, 45–50. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2015.04.006

- Perez-Batres, L. A., Doh, J. P., Miller, V. V., & Pisani, M. J. (2012). Stakeholder pressures as determinants of CSR strategic choice: Why do firms choose symbolic versus substantive self-regulatory codes of conduct? Journal of Business Ethics, 110(2), 157–172. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1419-y

- Ramasamy, B., & Yeung, M. (2009). Chinese consumers’ perception of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 119–132. doi:10.1007/s10551-008-9825-x

- Raufflet, E., Cruz, L. B., & Bres, L. (2014). An assessment of corporate social responsibility practices in the mining and oil and gas industries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 84, 256–270. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.077

- Scott, W. R. (2001). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oakes: Sage.

- Sethi, S. P., Martell, T. F., & Demir, M. (2017). Enhancing the role and effectiveness of corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports: The missing element of content verification and integrity assurance. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(1), 59–82. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2862-3

- Tomlinson, K. (2017). Oil and gas companies and the management of social and environmental impacts and issues. The evolution of the industry’s approach WIDER Working Paper 2017/22. United nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research. Retrieved from Wider.unu.edu

- Tooley, S., Hooks, J., & Basnan, N. (2010). Performance reporting by Malaysian local authorities: Identifying stakeholder needs. Financial Accountability & Management, 26(2), 103–133. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0408.2009.00478.x

- Verhoest, K., Verschuere, B., & Bouckaert, G. (2007). Pressure, legitimacy, and innovative behavior by public organizations. Governance, 20(3), 469–497. doi:10.1111/gove.2007.20.issue-3

- Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd ed.). Beverly Hills, C.A: Sage.