Abstract

The purpose of the study on which this article is based, was to interrogate the relationship marketing practices of small retailers in South Africa. The researcher also explores the impact of relationship marketing practices on the performance of small retailers in South Africa (SA). Objectives were formulated and hypotheses were tested using ANOVA and regression analysis and survey data drawn from small retailers’ owners/managers in South Africa. The results indicate that small retailers in SA practice relationships marketing and that they share information with suppliers and are involved in various types of relationships such as ling-term relationships, collaborative relationships and transactional relationships. Information sharing was found to influence the performance of small retailers while other relationship types did not. Moreover, the age of the owners of small enterprises did not influence their relationship marketing practices, while their level of education was found to do so. This study offers managerial insights into the roles that relationship marketing, especially information sharing with their suppliers play in the performance of small retailers. This study makes three key contributions. First, the study proved that small retailers practice relationship marketing, although they still emphasise transactional relationships over collaborative relationships. Second, the importance of information sharing in small retailers, which requires that small retailers continue sharing information for improved business performance. Third, the demographics of small business owners/managers have no influence on relationship marketing practices.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper is about relationship marketing and how small retailers can utilise relationship marketing to their advantage. Small retailers in SA face severe competition from large retailers. Relationship marketing could benefit them since they will be able to attract and keep customers in their businesses. Readers will understand relationship marketing and the types of relationship marketing practices suitable for small retail businesses.

1. Introduction

Relationship marketing has been the subject of investigation for more than two decades. Most studies, however, focus on large businesses, with the result that the principles and practices of relationship marketing have been developed from their point of view, while ignoring the existence of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Small retailers, which are regarded as SMEs, are not exempt from undertaking relationship marketing—to survive, they need to attract and retain both suppliers and customers.

The retail industry in South Africa has experienced significant changes due to shopping centre developments across the country. Compared to a decade ago. In SA, 32 new shopping centres are developed everyday while 17 new shopping centres were developed in 2017 alone (APA-News, 2017:1). These development poses a major challenge to small retailers operating in the same area. Small retailers now face severe competition from major retailers that have expanded their operations into new areas, including regions where smaller entities were known to operate. As a result of this expansion, smaller enterprises have been losing customers to major retailers (Durham, Citation2011, p. 34). Relationship marketing could be useful for those small retailers set on retaining customers and surviving. This is because relationship marketing seeks long-term relationships with existing stakeholders in the marketing process, including suppliers, allies, competitors, distributors, employees and consumers (Steyn, Ellis, & Musika, Citation2004, p. 35–36). Businesses can gain competitive advantage by choosing the right supplier(s) (Agarwal, Sahai, Mishra, Bag, & Singh, Citation2011, p. 801) with whom to develop lasting relationships.

As competition continues to intensity, so consumers are moving away from small retailers and shopping at larger outlets such as Checkers, PicknPay, spaza shops (informal retail outlets) and Spar (Italian Trade Agency, Citation2013, p. 1). Reasons why consumers are moving away from smaller retailers include the fact that they can expect competitive prices when shopping at larger retailers (Strydom, Citation2012, p. 163, 170), which also stock a greater variety of products at discounted prices (Liedeman, Charman, Piper, & Petersen, Citation2013, p. 2). The ability of small retailers to build long-lasting and collaborative relationships with their suppliers could enhance their standing in the market, and enable them to be competitive.

Small retailers fall into the Department of Trade and Industry’s definition of small, medium, and micro enterprises (SMMEs), as outlined by the National Strategy for Small Business Development (DTI, Citation1996, p. 6). As SMEs, small retailers play a vital role in the economic development of a country (Muhammed, Char, Yasoa, & Hassan, Citation2010) and fulfil numerous roles, ranging from poverty alleviation and employment creation, to international competitiveness (Nieman, Hough, & Nieuwenhuizen, Citation2003). In South Africa, SMEs account for almost 91 per cent of businesses, contribute 60 per cent towards the country’s employment and 51–57 per cent towards the gross domestic product (GDP) (Kongolo, Citation2010). The survival of small retailers is thus crucial for the economy. Relationship marketing could benefit them and sustain their businesses through building long-term and collaborative relationships which, in turn, will generate certain benefits, including creating a profitable market for their products, securing cost savings, enhancing efficiencies and reducing risk (Dos Santos, Citation2010, p. 117).

1. Literature review

1.1. Small retailers in South Africa

Small retailers in SA face competitive pressures form large retailers, especially the supermarkets, that offer the supplementary service such wide assortment of products, other non-food products selling concurrently in a convenient setting and are able to offer high quality products in convenient location with ‘one-stop” shopping and an overall shopping experience (Basker & Noel Citation2013, p. 4). Supermarkets also have market advantages over small retailers since they invest in logistics, distribution centres, networks and inventory maintenance more than independent retailers do (Das Nair Citation2016, p. 1; Reardon, Timmer, Barrett & Berdegue Citation2003, p. 1142). Estimates suggest that the modern retail industry in SA accounts for approximately 70 percent of national retail markets of which supermarkets are an important source of supply in the retail food sector (Durham, Citation2011, p. 34). This has created pressure on small independent retailers (both formal independent supermarkets and spaza shops). A spaza shop is an informal convenience shop usually run from home. Spaza shops supplement household incomes of owners by selling everyday household items (Wikipedia).

The small independent retailers target low-income consumers and are a means through which small suppliers can enter into the supply chain (Das Nair& Chisoro Citation2015, p. 2). Small retailers represents an alternative model of entry for small players in the supermarket industry as opposed to the traditional supermarket chain model (Das Nair & Dube, Citation2015, p. 4). The retail sector in SA consists of the formal and informal sector. The informal sector consists mainly of spaza shops, hawkers and street vendors, which are found in townships (Ravhugoni & Ngobese Citation2010, p. 7).

1.2. Relationship marketing

Gupta and Sahu (Citation2012, p. 59) define relationship marketing as “an approach to develop a long-term association with customers, measure the satisfaction level and develop effective programs to retain the customer with the business”. Relationship marketing emphasises cooperative and trusting relationships between buyers, suppliers and other stakeholders in the marketing value chain. Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994, p. 31) demonstrate that an effective relationship marketing investment builds stronger, more trusting customer relations. In a business-to-business (B2B) environment, strong relationships with customers generate satisfactory returns for suppliers (Palmatier, Scheer, Evans, & Arnold, Citation2008, p. 186). According to Monczka, Handfield, Giunipero, Patterson & Waters (Citation2010, p. 109) relationship with suppliers and customers is regarded as the best way of improving costs, quality, delivery, time schedules and other measures of performance.

Relationship marketing establishes long-term relationships with customers as well as other role-players, which will contribute to the successful operation of the business in the future (Eiriz & Wilson, Citation2006, p. 275–276). The purpose of relationship marketing is to establish relationships with all stakeholders (particularly suppliers), to involve them in new product development activities and to create multi-functional teams consisting of customers and suppliers (McIvor, Humphreys, & McCurry, Citation2003, p. 152). Oboreh, Francis, and Ogechukwu (Citation2013) found relationship marketing to be an effective strategy for small businesses. Furthermore, Kawsar (Citation2016) found that Muslim owned businesses apply relationship marketing for the benefit of not only customers but their god (Allah) to ensure long term survival of the business. .

Instead of an adversarial approach, collaborative relationships are preferable, where all parties/employees within the business are involved in building relationships with diverse stakeholders. Transactional relationships are largely characterised by distrust, limited communication and distant relationships, which are limited to simple purchasing transactions (Swink, Melnyk, Cooper, & Hartley, Citation2011, p. 294). The focus, in transactional relationships, is on minimising the price of goods and services by buying products from a large number of suppliers and using short-term contracts to obtain the best bargaining position against competing suppliers (Makhitha, Cant, & Theron, Citation2016, p. 287). By contrast, collaborative relationships are guided by trust and commitment from both parties, and a willingness to share information. Communication takes place at all levels, and involves sharing information as well as suggestions for continuous improvements (Bataineh, Al-Abdallah, Salhab, & Shoter, Citation2015, p. 127).

Relationship marketing holds many benefits for businesses, both at the operational and the strategic level. Amongst the operational benefits for the buyer, of developing close relationships with key suppliers, are improved quality or service delivery, and reduced costs (Villena, Revilla, & Choi, Citation2011, p. 574). At the strategic level, benefits include enhanced business performance due to sustainable improvements in product quality, innovation, enhanced competitiveness, and increased market share (Kannan & Tan, Citation2006, p. 769). Importantly, relationships with different suppliers must be managed differently, since not all parties are necessarily at the same relationships stages in the supply chain. Further, relationships between buyers and suppliers tend to influence businesses performance (Adams, Khoja & Kauffmann, Citation2012, p. 31). Hsu, Kannan, Tan and Leong (Citation2008, p. 305) found that relationship marketing and information sharing influence both market performance (through high product quality levels) and competitive and financial performance (through market share and return on assets). To this end, Hsu et al. (Citation2008, p. 305) add that SMEs need to pay close attention to individual inter-firm relationships, and how they can immerse their businesses more broadly in the supply chain. Naili, Naryoso, and Ardyan (Citation2017) also stated that parties should ensure a long-term partnership and the quality of relationship between suppliers and small retailers.

Gronroos (Citation1994, p. 8) defines long-term relationships as existing where both parties, over time, learn how to best interact with each other, leading to decreasing relationship costs for the customer and supplier/service provider. Long-term relationships are mutually satisfactory, making it possible for customers to avoid the significant transaction costs involved in changing suppliers or service providers, and allowing suppliers to avoid suffering unnecessary quality costs. According to Sheu, Chen and Yae (Citation2006, p. 27), a long-term orientation refers to a party’s willingness to expend effort in developing a lasting relationship, as is frequently demonstrated by entities committing resources to a relationship in the form of time, money or facilities. A study by Makhitha (Citation2017, p. 662) found that retailers select suppliers with whom they want to be involved in long-term relationships and with whom they can share information in a collaborative relationship. Finally, businesses involved in long-term relationships are more likely to be profitable if they can reduce the cost of doing business.

Information sharing enhances the level of collaboration among parties involved in a relationship, and is therefore a key requirement for collaborative relationships (Claro & Claro, Citation2010, p. 226). This might, however, pose a challenge for small retail owners/managers, since maintaining and exploring the information benefits to be derived from current and future stakeholders require a great deal of resources and time, which they might not have. Existing studies reveal that businesses in collaborative relationships share information about both their company and their products (Chinomona & Pooe, Citation2013, p. 6). Furthermore, communication between suppliers and customers enables the former to know the latter’s needs, while permitting the customer to identify the supplier’s capabilities—both parties can thus meet the other’s needs (Handriana, Citation2016; Cao & Zang, Citation2010, p. 364).

1.3. Relationship marketing in small businesses/retailers

Resource constraints is one of the challenges which has an impact on SMEs’ ability to undertake relationship marketing. The lack of a management information system limits the use of data which is already available within organisations, thereby hampering information sharing. Since SMEs are characterised by owner/manager structures, collaborative relationships are entered into between different owners/managers, while other employees are only involved to a lesser extent (Percy, Visvanathan, & Watson, Citation2010, p. 2601). This affects the ability of SMEs to build long-lasting and collaborative relationships.

While relationship marketing emphasises the need to build relationships with a few suppliers, small retailers often need to find a variety of different suppliers to meet the changing needs of their customers, instead of continuing to work with existing suppliers with whom they have quality relationships (Adjei, Griffith, & Noble, Citation2009, p. 500). Therefore, strong relationships with suppliers might hamper the ability of small retailers to respond to market demands in a timely manner. Small retailers nevertheless need to leverage their relationships with existing suppliers, if they are to respond to the market effectively, when the overall competitive landscape changes (Adjei et al., Citation2009, p. 500).

Due to the limited size of their businesses, small retailers are often unable to procure goods at low prices, compared to their large competitors. Small retailers also face the challenge of suppliers not offering fair prices or beneficial terms of supply (Das Nair & Dube, Citation2015, p. 4). This makes it difficult for smaller entities to provide a variety of products at relatively cheaper prices, while large retailers have that ability to do so (D’ Haese & Van Huylenbroeck, Citation2005, p. 95).

Small businesses are known to build interpersonal relationships with their stakeholders, but they also establish transactional relationships (Coviello, Brodie, & Munro, Citation2000, p. 531). As Adams et al. (Citation2012, p. 31) report, small enterprises are more likely to build long-term relationships. By contrast, big businesses prefer looser relationships with small businesses as customers or suppliers, due to the limited resources of the latter (Van Scheers, Citation2011, p. 50). Badenhorst-Weiss, Cilliers and Eicker (Citation2014) reported that small retail businesses in South Africa that focused on product-related (product quality, product variety and best brands) elements in their market offering as the main competing discipline, tend to survive and grow.

Liedeman et al. (Citation2013) found that small retailers in SA face major challenges from those small retailers owned by foreigners because they are unable to negotiate price discounts and merchandising services from producers are therefore unable to charge competitive prices.

2. Problem statement and objectives

SMEs use different methods from large businesses, when engaging in purchasing relationships. Large businesses tend to be governed by formal arrangements, such as contracts and credit terms (Morrissey & Pittaway, Citation2006, p. 293). Relationships marketing between retailers and their suppliers evolved since 1983 (Berry, Citation1983), and have evolved from transactional to more collaborative relationships, and have become less exploitative and more cooperative as both sides recognise the need to invest in their supply chain relationships, to protect their business interests (White, Citation2000, p. 15). Historically, suppliers and retailers have had rather adversarial relationships, thus mutual trust and collaboration were difficult to nurture (Sheu, Chen & Yae, Citation2006, p. 35). However, relationships have become less exploitative and more collaborative, as parties need to invest in relationships in the supply chain for their mutual benefit (White, Citation2000, p. 15). Small retailers should look into the prospect of developing strong and close relationships, which is referred to as relationship quality (Ismail, Citation2014). Makhubela (Citation2019) found that small retailers do not face challenges when building relationships with customers and suppliers.

A study by Makhitha (Citation2017, p. 662) found that relationship-marketing practices, such as fostering collaborative and long-term relationships, help to grow the number of customers and boost the profitability of SMEs. In addition, selecting the right suppliers can also boost a firm’s performance (Wouters, Anderson, & Wynstra, Citation2005, p. 190). Businesses tend to measure their success by determining how many new customers and suppliers they attract, instead of gauging their ability to retain existing customers and suppliers (Dean, Citation2002, p. 3). According to Dean (Citation2002, p. 260), SMEs that build close relationships with customers and suppliers, in order to understand the challenges and problems they face, are well informed. Whilst studies have shown that relationship marketing benefits small businesses and retailers, little is known about how small retailers in Johannesburg, in South Africa, achieve this. Roberts-Lombard (Citation2010), who conducted a study on the relationship-marketing practices of travel agencies in the Western Cape, found that those entities indeed undertake long-term relationship marketing. Drotskie and Okanga (Citation2016), by contrast, found that small businesses prefer short-term relationships. The following questions therefore arise: Do small retailers undertake relationship marketing? Do relationship-marketing practices differ from one small retailer to the next?

2.1. Hypothesis development

Studies on the impact of demographic factors on small retailers supplier selection and relationship marketing has proven that demographics factors impact on marketing practices of small retailers (Makhitha, Citation2017). Experienced owners and managers of small retailers are in a position to execute relationship marketing than their younger counterparts (Afande, Citation2015). Makhubela (Citation2019) and Soke and Wiid (Citation2016) also found that age and years of operation impact on the marketing practices of small retailers. Furthermore, Fuertes, Egdell, & McQuaid, Citation2013 and Sin Tan, Choy Chong, Lin, and Cyril Eze (Citation2010) also found age and years’ experience to influence relationship marketing practices. It is therefore hypothesised that:

H1The demographic factors influence relationship marketing practices of small retailers in SA.

According to Field Larry and Meile (Citation2008), information technology enhances information-sharing, and is associated with satisfaction with overall supplier performance. Andrew Millington Markus Eberhardt Barry Wilkinson (Citation2006), further found that the supplier and buyer benefit if they invest in their relationship which support that relationship marketing influences the performance of business and including all stakeholders involved in a relationship. In a study by Sheu et al. (Citation2006), retailer- supplier-relationships were found to enhance supplier-retailer performance, especially those involved in information sharing, information sharing, long-term relationships and collaborative relationships. Adams et al. (Citation2012):31 found that small businesses are more likely to foster long-term relationships, which improves organisational performance due to knowledge and process sharing. Against the above background, the following hypothesis was developed:

H2 The performance of small retailers in SA is influenced by their relationships marketing practices.

3. Research methodology

The study on which this article is based, targeted small, independent retailers in the Johannesburg city centre and in Soweto, the large amalgamation of townships on the outskirts of Johannesburg and home to 40 per cent of the city’s inhabitants (as at 2004) (Ligthelm, Citation2008, p. 37). The target sample for the study was owners of small retailers in Soweto consisting of indigenous owners’ as well Indian and other foreign owned small retailers. The study adopted a convenience sampling method, since the author did not have access to a database of small retailers in that geographical area. As noted by Cooper and Schindler (Citation2006, p. 245), convenience sampling is a method that allows the researcher to choose suitable, available subjects for study.

Two fieldworkers received training prior to assisting with the data collection process. The fill-in questionnaire was pre-tested with 20 small retailers. Feedback from the pilot test was used to adapt the wording of the texts, before the fieldworkers distributed the final questionnaires to independent retailers for completion.

The targeted number of questionnaires was 200, and more than that number were distributed personally by fieldworkers, but only 116 were returned completed, i.e., a response rate of 55 per cent. The researcher attributed the low response rate to independent retailers’ likely unwillingness to participate in the study.

Literature on relationship marketing in small businesses and retailers (Bataineh et al., Citation2015; Chinomona & Pooe, Citation2013; Claro & Claro, Citation2010; Hsu et al., Citation2008; Kannan & Tan, Citation2006; Villena et al., Citation2011) was used to design the questionnaire. The 24 items comprising the questionnaire were used to measure the relationship practices small retailers followed when engaging with their suppliers. In addition, three items measuring the impact of relationship marketing practices on the performance of independent retailers were inserted. A Likert scale was used, ranging from extremely important = 5 to not important at all = 1. The demographic section consisted of 14 questions that helped to determine the background profiles of the small retailers participating in the study. Data were analysed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics were used, and ANOVA tests (statistical analyses used to test for differences between two means or more group means (Sudman & Blair, Citation1998, p. 483) were conducted. A significant ANOVA result would indicate that at least one pair of means differ significantly, therefore post hoc tests can indicate which pair(s) differ(s) significantly (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2010, p. 473).

4. Results and findings

4.1. Demographic profile of respondents

The demographic profile of the retailers appears in Table . The majority of respondents were male (51%, n = 60), which shows that most retailers are either owned by men. As can be seen from the table, almost two-thirds (64.4%, n = 74) of respondents were aged 25–40, which implies that the businesses in question are mainly owned by the younger generation. The majority of respondents had completed grade 12/matric (31.0%, n = 36), while a considerable number had a diploma or certificate (25.0%, n = 29).

Table 1. Demographics of the respondents

Most businesses had been in operation for a period of three years or less (47.4%, n = 55), while 37.9 per cent had matured beyond five years (n = 44). Buying in small retailers is mostly done by the owner-managers (59.6%, n = 68). More than 90 per cent (92.8%, n = 103) of respondents indicated that they had one to ten suppliers for their chosen product(s). Most respondents (85.3%, n = 93) bought directly from wholesalers.

4.2. Types of products sold by the retailers

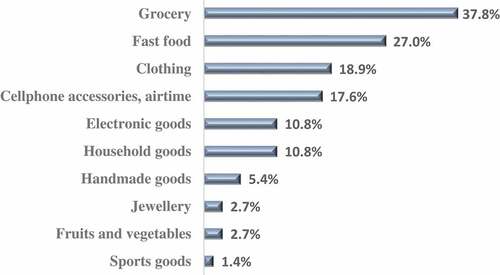

On average, the respondents sold 1.35 different products, the most popular of which was groceries (37.8%, n = 28), followed by fast food (27.0%, n = 20) and the least popular sports goods (1.4%, n = 1) (see Figure ).

4.3. Support received from suppliers

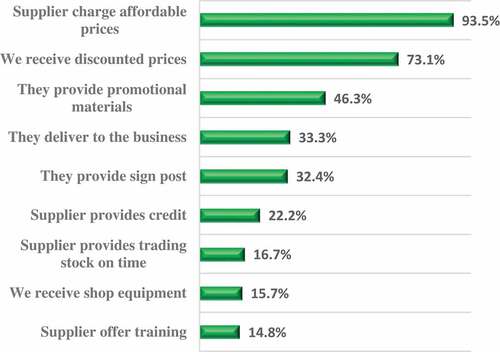

On average, the respondents mentioned 3.41 ways in which their suppliers supported them. Most respondents (93.5%, n = 101) felt that their suppliers did so by charging affordable prices, offering discounted prices, or providing promotional materials (see Figure ).

5. Retailer-supplier relationship marketing practices

Principal component analysis (PCA) with IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used to examine patterns of correlations between the questions used to measure the relationship practices of independent retailers. The factorability of the correlation matrix was investigated using Pearson’s product-moment and Spearman’s correlation coefficients. The correlation matrix (Table ) shows coefficients of 0.3 and above, especially between information sharing and long-term relationships, and between long-term relationships and collaborative relationships. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.710, which is well above the recommended minimum value of 0.6 (Field & Miles, Citation2010, p. 560). Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Hair et al., Citation2010, p. 92) attained statistical significance at p < .001. Thus, the correlation matrix was deemed factorable.

Table 2. Correlations among the latent constructs (Pearson’s in the lower half/Spearman’s in the upper half)

Varimax rotation was performed. Factor loadings of less than 0.5 were excluded from the analysis. Hair et al. (Citation2010, p. 117) consider factor loadings of 0.30 to be acceptable, but this is dependent on sample size. For example, Stevens (cited in Field & Miles, Citation2010, p. 557) indicates that, for a sample of 200, a factor loading of 0.364 is acceptable, while for a sample of 1 000, 0.162 is acceptable. Although variables with a loading of 0.3 can be interpreted, it should be noted that the higher the loading, the more the variable is a pre-measure of the factor.

A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.74 was achieved, with constructs loading a Cronbach alpha of between 0.5 and 0.85. Malhotra (Citation2010, p. 319) deems a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.60 acceptable, and 0.70 an indication of satisfactory internal consistency. To determine the validity of the instrument, a threshold of 0.38 to 0.83 was maintained on the communalities, as well as a cut-off point of 0.30 on the Pearson’s correlations, as proposed by Kim and Mueller (Citation1978). This resulted in eight items being dropped from the factor analysis after loading unsatisfactorily in the initial scale refinement procedure, which suggests that those items may be incapable of differentiating between factors. Thus, 15 items were factor analysed: four factors/components were identified, with one factor loading two items. The components were named as follows: Information sharing (factor 1), Long-term relationships (factor 2), Transactional relationships (factor 3) and Collaborative relationships (factor 4). The percentage of variance for the factors was 66.36 (see Table ).

Table 3. Factor analysis

Factor 1, which loaded six items, closely related to the sharing of information, and was thus named “Information sharing”. It included items such as “We share competitor information with suppliers” (M = 4.00); “We share new product ideas with our suppliers” (M = 4.21); “We communicate our changing needs with suppliers” (M = 4.36), “We share information with our suppliers regarding the quality of the products” (M = 4.59) and “We exchange performance feedback” (M = 3.90). It appears that small retailers value their relationships by sharing information with their suppliers, as shown by the high mean score of 4.210. According to Bordonaba-Juste and Cambra-Fierro (Citation2009, p. 399), communication between suppliers and customers enables the former to know the customer’s needs, permits the buyer to identify the supplier’s capabilities, and enables both to match each other’s needs. Information sharing further enables parties in the relationships to improve their products, as well as their promotional and distribution strategies, by sharing information on product development, marketing and promotional strategies, as well as future distribution initiatives (Roberts-Lombard, Citation2010, p. 11).

Factor 2, named “Long-term relationships”, loaded four items. This factor had the highest mean score of 4.19, which implies that small retailers prefer long-term relationships to other types of relations. They exhibit long-term relationship practices, as was evident from the following: “Sustaining relationships with suppliers” (M = 4.47), “We have plans to continue with this relationship” (M = 4.15), “We expect our relationship with suppliers to last a long time” (M = 4.44), “We have long-term relationships with suppliers” (M = 4.32) and “We review all our supply relationships regularly in order to identify problems and/or opportunities” (M = 3.73). The fact that “We sustain our relationships with suppliers” has the highest mean score (M = 4.47), shows that the respondents value long-term relationships.

Makhitha (Citation2017, p. 663) found that long-term relationships lead to increased profits—a finding corroborated by numerous researchers (Akridge, Gray, Boehlje, & Widdows, Citation2007, p. 6; Chung, Sternquist, & Chen, Citation2006, p. 354; Coviello et al., Citation2000, p. 538; Roberts-Lombard, Citation2010, p. 10).

The third factor, which loaded three items that reflected transactional behaviours, was named “Transactional relationships”. The mean score for this type of relationship was 3.91, followed by the fourth factor, “Collaborative relationships”, which loaded two items and had a mean score of 3.58. The findings reported on here, seem to suggest that small retailers engage in transactional relationships more than they do in collaborative relationships, but prefer long-term relationships to both of the aforementioned. Small retailers change suppliers if they are not performing well, and are willing to do so from time to time. Businesses entering into transactional relationships buy goods from a large number of suppliers that can be played off against each other, in order to gain advantages, and they use only short-term contracts (Thakkar & Deshmukh, Citation2008, p. 95). Existing studies support the notion that some small businesses establish transactional relationships (Morrissey & Pittaway, Citation2006, p. 293). Forming collaborative relationships helps boost the number of customers (Makhitha, Citation2017, p. 663), which implies that small retailers may lose customers by failing to enter into collaborative relationships. Smaller enterprises which emphasise collaborative relationships value having fewer suppliers, as this allows them to concentrate on order volumes and to gain greater influence over suppliers. This enables retailers to focus on selected suppliers, which reduces the total cost of ownership (Eggert, Ulaga, & Hollman, Citation2009, p. 145).

6. Relationship marketing practices and demographic factors

To establish whether age has a significant effect on relationship marketing, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to test for significant mean differences. The test revealed that age does not have a significant effect on any of the four factors uncovered by means of exploratory factor analysis.

To establish whether level of education has a significant effect on relationship marketing, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to test for significant mean differences. The test revealed that level of education does not have a significant effect on transactional relationships. The test did indicate, however, that level of education has a significant effect on information sharing (χ2(4) = 11.123, p < .05). The Mann-Whitney U was subsequently used as post-hoc test to determine which pairs of groups differed significantly.

The mean rate at which those respondents who completed matric (MR = 21.78, n = 36) shared information with their suppliers was significantly lower than that of those who had a degree (MR = 31.27, n = 11).

The mean rate at which those respondents who completed matric (MR = 24.18, n = 36) shared information with their suppliers was significantly lower than that of those who had a postgraduate qualification (MR = 34.14, n = 18).

The mean rate at which those respondents with a diploma/certificate (MR = 18.05, n = 29) shared information with their suppliers was significantly lower than that of those who had a degree (MR = 26.95, n = 11).

The mean rate at which those respondents with a diploma/certificate (MR = 20.29, n = 29) shared information with their suppliers was significantly lower than that of those who had a postgraduate qualification (MR = 29.97, n = 18).

The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed that education level has a significant effect on long-term relationships (χ2(4) = 16.007, p < .01). The Mann-Whitney U was used as post-hoc test to determine which pairs of groups differed significantly.

The importance attached to sustaining relationships with suppliers by those respondents without a matric (MR = 14.14, n = 22) was significantly lower than for those with a degree (MR = 22.73, n = 11).

The importance attached to sustaining relationships with suppliers by those respondents without a matric (MR = 15.00, n = 22) was significantly lower than for those with a postgraduate degree (MR = 27.22, n = 18).

The importance attached to sustaining relationships with suppliers by those respondents with a matric (MR = 23.38, n = 36) was significantly lower than for those with a postgraduate degree (MR = 35.75, n = 18).

The importance attached to sustaining relationships with suppliers by those respondents with a diploma/certificate (MR = 20.59, n = 29) was significantly lower than for those with a postgraduate degree (MR = 29.50, n = 18) as shown in Table .

Table 4. The impact of relationship marketing on small retail performance

The Kruskal-Wallis test found that level of education has a significant effect on collaborative relationships (χ2(4) = 13.356, p < .05). The Mann-Whitney U was used as post-hoc test to determine which pairs of groups differed significantly. This is shown in Table below.

The collaborative relationships for those respondents without a matric (MR = 15.84, n = 22) was significantly higher than for those with a postgraduate degree (MR = 26.19, n = 18).

The collaborative relationships for those respondents with a matric (MR = 23.00, n = 36) was significantly higher than for those with a postgraduate degree (MR = 36.50, n = 18).

The collaborative relationships for those respondents with a diploma/certificate (MR = 19.74, n = 29) was significantly higher than for those with a postgraduate degree (MR = 30.86, n = 18).

To establish whether business maturity has a significant effect on relationship marketing, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to test for significant mean differences among the age groups.

The Kruskal-Wallis test found that business maturity does not have a significant effect on any of the four factors uncovered through exploratory factor analysis.

7. Relationship marketing and small retailer performance

To determine whether relationship marketing influences the performance of small retailers, the respondents were asked to identify one supplier from whom they had recently purchased merchandise, and to indicate how buying from this supplier benefited their business, in respect of a growing number of customers, increased profits and greater market share.

The responses regarding growing number of customers, increased profits and greater market share are strongly correlated (r ranging from 0.640 to 0.792) and the set of questions demonstrate strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.885). Subjecting these three benefit items to Principal Component analysis resulted in a single latent construct with strong loadings for each of the three improvement items (ranging from 0.871 to 0.934) and explaining 81.35% of the variation on the data. A new construct was created by calculating the mean of the responses for the three benefit items for each respondent. This construct was named “Buying from this supplier improved our business in terms of increased number of customers, increased profits and enlarged market share”.

Standard multiple regression was performed by using ‘Buying from this supplier improved our business in terms of increased number of customers, increased profits and enlarged market as dependent variable against information sharing, long-term relationship, transactional relationship and collaborative relationship. The data was found to be free of multicollinearity and the residuals are normally distributed and independent of the predicted values. The results are listed in Table .

The regression results indicate that there is a significant relationship between Information sharing and the benefits that the businesses experience because of dealing with their chosen supplier. The effect of the other relationship dimensions did not demonstrate a significant contribution in the model.

8. Recommendations and conclusions

Although the results of this study revealed that small retailers practise information sharing, and foster long-term, transactional and collaborative relationships, they were found to prefer long-term relationships over other types of relations, as shown by the high mean score (M = 4.219), followed by information sharing (M = 4.210). The fact that small retailers foster long-term relationships and share information with their suppliers is a step in the right direction for their businesses. They need to maintain these types of relationships, as it will ensure that, in the long term, these small entities continue to receive good-quality products from their suppliers (Roberts-Lombard & Steyn, Citation2008, p. 25).

By fostering long-term relationships, small enterprises will form bonds with suppliers who are able to learn, improve and grow in the relationship (Naudé & Badenhorst-Weiss, Citation2012, p. 95). Information sharing is more crucial in long-term and collaborative relationships (Claro & Claro, Citation2010, p. 227): by sharing information with their suppliers, smaller retailers have the possibility of enhancing their performance (Chinomona & Pooe, Citation2013, p. 6).

Collaborative relationships received less attention than other types (M = 3.58). Small retailers are urged to strengthen their engagement with suppliers so that, in the long term, those bonds develop into collaborative relationships, which are more beneficial than mere long-term relationships (Makhitha, Citation2017, p. 663).

Small retailers without post-school qualifications are less keen to share information and foster long-term relationships than those with a post-school or postgraduate qualification. This implies that small retailers might realise the importance of information sharing and long-term relationships for the survival of their businesses if they have the benefit of a further qualification. It is important to note that small retailers without post-school qualifications emphasise collaborative relationship marketing, more so than those with post-school qualifications do, possibly because they realise the importance of such collaboration. Business customers that rely on their suppliers can reduce costs, enhance product quality and develop innovations faster than their competitors’ suppliers (Liker & Choi, Citation2006, p. 23).

The regression results has shown that small retailers benefit from information through increased number of customers, increased profits and enlarged market share. It is advisable that small retailers strengthen their relationship with suppliers and continue sharing information with their suppliers so as to increase the benefits received through relationship marketing.

9. Research limitations and future research

The study found that small retailers nurture long-term relationships, and share information with their suppliers. To them, collaborative relationships are less crucial than relations of a transactional nature. Further, the study revealed that for small retailers the practice of relationship marketing differs, depending on the level of education of the owner/manager. Educated small entrepreneurs are prone to practise information sharing and build long-term relationships, while those who are less educated lag behind in this regard. Less-educated small retailers engage in collaborative relationships, more so than those who are educated.

While the study targeted small retailers in Johannesburg and Soweto, the findings cannot be generalised across small businesses in South Africa. Further studies could investigate the relationship practices of small retailers across different regions of this country.

The research method used in this study was convenience sampling, since no database of small retailers in Johannesburg and Soweto was available at the time. Further studies could investigate the marketing communication practices of small retailers, so as to enable their owners/managers to market their businesses better and enhance their chances of survival. Future studies might also focus on the factors that satisfy small retailers’ customers, or might investigate the relationship between small retailers and their customers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

KM Makhitha

K.M Makhitha is an associate professor and the HOD of the department of marketing and retail management at the University of South Africa (Unisa). Her research focus area is on consumer behaviour and small business marketing. The small business marketing research project focus on SMEs marketing in general and also small independent retailers.

References

- Adams, J. H., Khoja, F. M., & Kauffman, R. (2012). An empirical study of buyer–Supplier relationships within small business organizations. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(1), 20–17.

- Adjei, M. T., Griffith, D. A., & Noble, S. M. (2009). When do relationships pay off for small retailers? Exploring targets and contexts to understand the value of relationship marketing. Journal of Retailing, 85(4), 493–501.

- Afande, O. F. (2015). Factors influencing growth of small and microenterprises in Nairobi central business district. Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development, 9(1), 104–139.

- Agarwal, P., Sahai, M., Mishra, V., Bag, M., & Singh, V. (2011). A review of multi-criteria decision-making techniques for supplier evaluation and selection. International Journal of Industrial Engineering Computations, 2(4), 801–810.

- Akridge, A. T., Gray, J., Boehlje, A., & Widdows, R. (2007). An evaluation of CRN practices among agribusiness. International Food Agribusiness Management Rev, 10, 36–60.

- Andrew Millington Markus Eberhardt Barry Wilkinson. (2006). Supplier performance and selection in China. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26(2), 185–201.

- Badenhorst-Weiss, J., Cilliers, J.O, & Eicker, T. (2014). Unique market offering by formal independent retail and wholesale small businesses in soweto township. South Africa. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 12(4), 366-376.

- Basker, E, & NoeL, M. 2013. Competition challenges in the supermarket sector with an application to Latin American markets. Report for the World Bank and the Regional Competition Centre for Latin America. Retrieved from: https://www.fne.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Competition-Challenges-in-the-Supermarket-Sector.pdf.

- Bataineh, A. Q., Al-Abdallah, G. M., Salhab, H. A., & Shoter, A. M. (2015). The effect of relationship marketing on customer retention in the Jordanian pharmaceutical sector. International Journal of Business and Management, 10(3), 117–131.

- Berry, L. L. (1983). Relationship marketing. In L. L. Berry, G. L. Shostack, & G. D. Upah (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on services marketing (pp. 25–28). Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association.

- Bordonaba-Juste, V., & Cambra-Fierro, J. J. (2009). Managing supply chain in the context of SMEs: A collaborative and customized partnership with the suppliers as the key for success. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 14(5), 393–402.

- Cao, M., & Zhang, Q. (2010). Supply-chain collaborative advantage: A firm’s perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 128, 358–367.

- Chinomona, R., & Pooe, R. I. D. (2013). The influence of logistics integration on information sharing and business performance: The case of small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 7(1), 1–9.

- Chung, J., Sternquist, T. B., & Chen, Z. (2006). Retailer–Buyer supplier relationships: The Japanese difference. Journal of Retailing, 82(4), 349–355.

- Claro, D. P., & Claro, P. B. O. (2010). Collaborative buyer–Supplier relationships and downstream information in marketing channels. Industrial Marketing Management, 39, 221–228.

- Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2006). Business research methods (9th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Coviello, N., Brodie, R. J., & Munro, H. J. (2000). An investigation of marketing practice by firm size. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 523–545.

- D’Haese, M. D., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2005). The rise of supermarkets and changing expenditure patterns of poor rural households: A case study in the Transkei area, South Africa. Food Policy, 30, 97–113.

- Das Nair, R. 2016. Competition in supermarkets: a South African perspective 1. 2nd annual competition and economic regulation (Acer) week, Southern Africa. Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development, University of Johannesburg. Working paper, 11 March. Retrieved from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/52246331e4b0a46e5f1b8ce5/t/56f130034d088e7b7cb6fef4/1458647047632/Reena+das+Nair_Competition+in+Supermarkets+-+A+South+African+Perspective.pdf.

- Das Nair, R & Chisoro, S. (2015). The expansion of regional supermarket chains: changing models of retailing and the implications for local supplier capabilities in South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research. WIDER Working Paper 2015/114. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303984408_The_expansion_of_regional_supermarket_chains_Changing_models_of_retailing_and_the_implications_for_local_supplier_capabilities_in_South_Africa_Botswana_Zambia_and_Zimbabwe

- Das Nair, R., & Dube, S. S. (2015). Competition and regulation: Competition, barriers to entry and inclusive growth: Case study on fruit and veg city centre for competition. Regulation and Economic Development, University of Johannesburg. Working paper 9/2015. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg.

- Dean, A. A. (2002). The development of a relationship marketing framework that captures the delivery of value in entrepreneurial SMEs (Doctoral thesis). West Yorkshire: University of Huddersfield.

- DTI. (1996). National Small Business Act, NO. 102 OF 1996. Retrieved from: https://www.thedti.gov.za/sme_development/docs/act.pdf.

- Dos Santos, M. A. O. (2010). Benefits derived by a major South African retailer through collaboration and innovation within its supply chain. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 4(1), 102–119.

- Drotskie, A., & Okanga, B. (2016). Managing customer–Supplier relationships between big businesses and SMEs in South Africa. Journal of Contemporary Management, 13(1), 190–221.

- Durham, L. (2011). Opportunities and challenges for South African retailers. Supermarket & Retailer, 33–35.

- Eggert, A., Ulaga, W., & Hollman, S. (2009). Benchmarking the impact of customer share in key-supplier relationships. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 24(3/4), 154–160.

- Eiriz, V., & Wilson, D. (2006). Research in relationship marketing: Antecedents, traditions and integration. European Journal of Marketing, 40(3/4), 275–290.

- Field, A., & Miles, J. (2010). Discovering statistics using SAS. London, UK: Sage.

- Field Larry, J. M., & Meile, C. (2008). Supplier relations and supply chain performance in financial services processes. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 28(2), 185–206. doi:10.1108/01443570810846892

- Fuertes, V, . (2013). V & and mcquaid. R. 2013. Extending Working Lives: Age Management in Smes. Employee Relations Vol. 35 No, 3, pp. 272–293.

- Grönroos, C. (1994). From marketing mix to relationship marketing: Towards a paradigm shift in marketing. Management Decision, 32(2), 4–20.

- Gupta, A., & Sahu, G. P. (2012). A literature review and classification of relationship marketing research. International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management, 3(1), 56–81.

- Hair, J. F., Black, C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Handriana, T. (2016). The role of relationship marketing in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Journal Pengurusan, 48, 137–148.

- Hsu, C., Kannan, V. R., Tan, K., & Leong, G. K. (2008). Information sharing, buyer–Supplier relationships, and firm performance: A multi-region analysis. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 38(4), 296–310.

- Ismail, M. D. (2014). Building SMEs competitive advantage in export markets: The role of human capital and relationship quality. Jurnal Pengurusan, 40, 3–13.

- Italian Trade Agency. (2013). Overview of the South African retail market. ICE-Agenzia per la promozione all’estero e l’internazionalizzazione delle imprese italiane. On behalf of Veneto Promozione S.c.p.A, October. Internet: http://www.tv.camcom.gov.it/docs/Corsi/Atti/2013_11_07/OverviewofthesouthAfrica.pdf; downloaded 2016-07-01

- Kannan, V. R., & Tan, K. C. (2006). Buyer–Supplier relationships: The impact of supplier selection and buyer–Supplier engagement on relationship and firm performance. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 36(10), 755–775.

- Kawsar, M. D. J. (2016). Customer relationship marketing in the UK Muslim SMEs: An Islamic perspective (Thesis). Salford, UK: Salford Business School, University of Salford.

- Kim, J. O., & Mueller, C. W. (1978). Factor analysis: Statistical methods and practical issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Kongolo, M. (2010). Job creation versus job shedding and the role of SMEs in economic development. African Journal of Business Management, 4(11), 2288–2295.

- Liedeman, R., Charman, A., Piper, L., & Petersen, L. (2013). Why are foreign-run spaza shops more successful? The rapidly changing spaza sector in South Africa. Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation. Econ 3x3:1–.

- Ligthelm, A. A. (2008). The impact of shopping mall development on small township retailers. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 11(1), 37–53.

- Liker, J. K., & Choi, T. Y. (2006). Building deep supplier relationships harvard business review on supply chain management. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Makhitha, K. M. (2017). The impact of independent retailers’ relationship marketing practices on performance. Journal of Contemporary Management, 14, 645–673.

- Makhitha, M., Cant, M., & Theron, D. (2016). Business-to-business marketing. Cape Town: Juta.

- Makhubela, V. F. (2019). The impact of marketing communication strategies on the performance of small independent retailers in Soweto, South Africa (Dissertation). Pretoria: Unisa.

- Malhotra, N. K. (2010). Marketing research: An applied orientation (6th ed.). New York: Pearson.

- McIvor, R., Humphreys, P., & McCurry, L. (2003). Electronic commerce: Supporting collaboration in the supply chain? Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 139, 147–152.

- Monczka, R, Handfield, R, & Giunipero, LC, Patterson, JL& waters d. 2010. Purchasing and supply chain management. 4th ed. Hampshire, UK: Cengage Learning

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment–Trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

- Morrissey, W. J., & Pittaway, L. (2006). Buyer–Supplier relationships in small firms: The use of social factors to manage relationships. International Small Business Journal, 24(3), 272–298.

- Muhammed, M. Z., Char, A. K., Yasoa, M. R., & Hassan, Z. (2010). Small and medium businesses (SMEs) competing in the global business environment: A case of Malaysia. International Business Research, 3(1), 66–75.

- Naili, F., Naryoso, A., & Ardyan, E. (2017). Model of relationship marketing partnerships between Batik SMEs and batik distributors in Central Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development, 8(4), 1–14. doi:10.4018/IJSESD

- Naudé, M. J., & Badenhorst-Weiss, J. A. (2012). Supplier–Customer relationships: Weaknesses in South African automotive supply chains. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 6(1), 91–106.

- Nieman, G., Hough, J., & Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2003). Entrepreneurship: A South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

- Oboreh, N., Francis, U. G., & Ogechukwu, A. D. (2013). Relationship marketing as an effective strategy by IGBO managed SMEs in Nigeria. Global Journal of Management and Business Research Marketing, 13(6), 1–21.

- Palmatier, R. W., Scheer, L. K., Evans, K. R., & Arnold, T. J. (2008). Achieving relationship marketing effectiveness in business-to-business exchanges. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36, 174–190.

- Percy, W. S., Visvanathan, N., & Watson, C. (2010). Relationship marketing: Strategic and tactical challenges for SMEs. African Journal of Business Management, 4(13), 2596–2603.

- Ravhugoni, T, & Ngobese, M. 2010. Disappearance of small independent retailers in south africa: the waterbed and spiral effects of bargaining power. Retrieved from: http://www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Disappearance-of-Small-Independent-Retailers-in-South-Africafinal.pdf.

- Reardon, T, Timmer, CP, Barrett, CB, & Berdegue, J. (2003). The rise of supermarkets in africa, asia and latin america. American Journal Of Agricultural Economics, 85, 1140-1146.

- Roberts-Lombard, M. (2010). The supplier relationship practices of travel agencies in the Western Cape Province – What is the status quo? Acta Commercii, 10, 1–14.

- Roberts-Lombard, M., & Steyn, T. F. J. (2008). The relationship marketing practices of travel agencies in the Western Cape province. South African Journal of Business Management, 39(4), 15–26.

- Sheu, C., Yen, H. R., & Yae, B. (2006). Determinants of supplier–Retailer collaboration: Evidence from an international study. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26(1), 24–49.

- Sin Tan, K., Choy Chong, S., Lin, B., & Cyril Eze, U. (2010). Internet-based ICT adoption among SMEs: Demographic versus benefits, barriers, and adoption intention. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 23(1), 27–55.

- Soke, B. V., & Wiid, J. A. (2016). Small-business: Marketing in Soweto, the importance of the human touch. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 14(4), 186–193.

- Steyn, T. F. I., Ellis, S. M., & Musika, F. A. A. 2004. Implementing relationship marketing: The role of internal and external customer orientation. Paper presented at the European Institute for Advances Studies in Management (EIASM) Workshop on Relationship Marketing (pp. 1–19), Brussels, Belgium.

- Strydom, J. W. (2012). Retailing in disadvantaged communities: The outshopping phenomenon revisited. Journal of Contemporary Management, 8, 150–172.

- Sudman, S., & Blair, E. (1998). Marketing research: A problem solving approach. International ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Swink, M., Melnyk, S. A., Cooper, M. B., & Hartley, J. L. (2011). Managing operations across the supply chain. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Thakkar, J., & Deshmukh, S. G. (2008). Evaluation of buyer–Supplier relationships using an integrated mathematical approach of interpretive structural modelling (ISM) and graph theoretic matrix: The case study of Indian automotive SMEs. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 19(1), 92–124.

- Van Scheers, L. M. (2011). SMEs’ marketing skills challenges in South Africa. African Journal of Business Management, 4(1), 504–525.

- Villena, V. H., Revilla, E. R., & Choi, T. Y. (2011). The dark side of buyer–Supplier relationships: A social capital perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 29, 561–576.

- White, H. M. F. (2000). Buyer–Supplier relationships in the UK fresh produce industry. British Food Journal, 102(1), 6–17.

- Wouters, M., Anderson, J., & Wynstra, F. (2005). The adoption of total cost of ownership for sourcing decisions: A structural equations analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(2), 167–191.