Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to report on the results of the study to establish the mediating role of flow experience on the relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace with a focus on public hospitals in Uganda. This study was cross-sectional and a total sample size of 800 professional nurses in public hospitals in Uganda was considered. The findings indicated that flow experience partially mediates the relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace. Besides, the finding also indicated that there is a significant and positive relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace. The findings correspond to the argument that in the face of the variety of theoretical and practical implications provided, there is a need for professional workers to be innately involved in their work if their psychological capital is to affect their level of happiness at the workplace. However, this paper is limited by the fact that the respondents’ emotions were examined through a cross-sectional research design and the time effects of these emotions were not examined and remain unknown under this study.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In light of today’s turbulent work environment, it is more important for organizations to ensure that they have happy and productive employees. This is because, happiness at the workplace is essential for increased productivity. This study examines the role of psychological capital in bringing about happiness at the workplace amongst professional nurses in public hospitals in Uganda, while most importantly considering the mediation effect of flow experience in this relationship. Interestingly, while the professional nurses are working in a poor environment, they are frequently joyful, articulate, fully engaged and contented at work. It is of no wonder that they have high emotional strength, innately involved in their work and a high level of happiness at the workplace. It is this natural state of affairs that needs to be nurtured across all professionals in Uganda and beyond so that organizational productivity could be registered for socioeconomic transformation.

1. Introduction

World over, happiness at the workplace is crucial for improving productivity. This is because, happy employees are usually productive while those who are unhappy may not pay full attention to any activity at work (Joo & Lee, Citation2017; Seligman, Citation2011). Happy employees are also hopeful, they balance work challenges and skills, concentrate on their tasks, are interested in their work and are able to sustain positive emotions (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2005; Kagaari & Munene, Citation2007; Lyubomirsky & Sheldon, Citation2012; Seligman, Citation2004). As Diener, Citation2000, p. 39) points out, “In most organizations, employee happiness is of great significance to most employer.” According to Diener and Seligman (Citation2002), happiness, in the form of joy, appears in every category of “basic” human emotions. Feeling happy is fundamental to employees’ experiences, and most employees are at least altruistically happy much of the time. McMahon (Citation2010) argues that happiness has attracted the attention of philosophers since the dawn of written history, but has only recently come to the fore in psychological research. In addition, scholars have done extensive studies on PsyCap and happiness at the workplace as identified in the literature (Luthans & Avolio, Citation2009; Lyubomirsky & Sheldon, Citation2012; Seligman, Citation2011).

Although there are many studies on happiness at the workplace, none of these studies has examined the contribution of PsyCap and happiness in Uganda among professional nurses, as well as examining flow experience as a mediator in the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace in a Sub-Saharan-African country like Uganda. The desire to establish the mediating role of flow experience in the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace in the health sector of Uganda formed the current research motivation. In this case, our results suggest that flow experience mediates the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace.

The results from this study are important in a number of ways: First, it contributes to the scant literature by documenting the mediating role of flow experience in the relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace using evidence from public hospitals in Uganda. Second, the study is important to the Government and managers of hospitals, especially in Uganda to consider the role of happiness in health service delivery. Indeed, when the employees are made happy at the workplace, they concentrate more on achieving daily tasks, especially in delivering health services to the patients. Finally, the study results are significant for policy makers, especially those involved in formulating health policies that affect the health workers.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: the next chapter reviews the extant literature; Section 3 describes the methods adopted in this study; Section 4 provides the results; Section 5 discusses the results from the study and finally Section 6 highlights the summary, conclusion, limitations, and areas for future studies.

2. Literature review and hypotheses setting

2.1. Theoretical underpinnings

Seligman (Citation2002) defines happiness as “consisting of pleasure, engagement, and meaning.” In this study, the authors utilize the Broaden and Build Theory (BBT) together with the Psychology of Flow Theory (PsyFT) to examine the mediating role of flow experience in the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace. BBT suggests how positive emotions broaden awareness and helps build psychological (personal) resources and produce happiness at the workplace (Fredrickson, Citation2001), while the PsyFT is anchored on the argument that employees are so involved in an activity that nothing else other than activity seems to matter (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2005; Jessica, Citation2010; Joo & Lee, Citation2017). The BBT explains the positive causes of happiness at the workplace. For example, employees are happy at work if in the past, they have gone through difficulties or if they have had too demanding targets to achieve and they have eventually achieved them. The theory further suggests that if one has hope of achieving his or her intended goals and is confident that he or she can achieve organizational objectives, then such an employee is likely to be happy. It thus follows that PsyCap is closely linked to happiness at the workplace.

Relatedly, the PsyFT argues that once employees perform their duties wholeheartedly and eventually get absorbed in those activities, the employees concentrate on them and, when they achieve their goals, they become happy. In other words, the decision to get absorbed into company activities may rely on whether an employee becomes happy if he or she meets his or her targets. It can be argued that even when an employee has the hope, self-efficacy is resilient and has the capacity to see through the future, with no concentration on company activities, less self-control and capacity to balance challenges and skills, he is likely not be happy at the workplace.

2.2. Psychological capital, flow experience and happiness at the workplace

A review of the literature reveals that studies examining the association between PsyCap and flow experience involve the transformation of potentially negative experiences into positive experiences over time (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1988; Joo & Lee, Citation2017). For example, in a longitudinal study of talented teenagers, Csikszentmihalyi (Citation2005) found that only those who learned to enjoy practicing their talent (i.e. mathematics, music, science, art, and athletics) were able to continue developing it through their high school years. Those who became bored or stressed of working on their talent, sooner or later gave up, while those who experienced flow in their work continued to perfect their talent (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2005; Malik, Citation2013). PsyCap is the assemblage and simultaneous presence of four components of positive psychological resources (hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism). While each can stand on its own merits, it is when they are all present and linked together that they can provide insight into an individual work-related flow experience. It is this simultaneous composite presence of the individual elements that makes it a higher-order construct (Luthans, Avolio, Avey, & Norman, 2007). Flow experience when supported by theoretical work, like the PsyFT, can meet the criteria of PsyCap (Luthans, Youssef, & Avolio, Citation2007). Indeed, PsyCap has been established and empirically proved to help in explaining happiness at the workplace (Bandura, Citation1977; Luthans & Avolio, Citation2009). Research shows that PsyCap components of self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience have positive relationships with happiness at the workplace. For example, self-efficacy has been found to have a positive impact on happiness at the workplace (Luthans & Avolio, Citation2009). Employees’ optimism is related to sustainable happiness at the workplace (Kahn, Citation1992). Hope and resilience have been found to be associated with employees’ happiness at the workplace (Malik, Citation2013) and their loyalty to the organizations they work with (Kahn, Citation1992).

Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1988) defines flow experience as “the holistic sensation that employees feel when they act with total involvement”. Thus, flow experience is a condition in which employees are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter at the time. The experience is so enjoyable that employees will do it even at great cost for the sheer sake of doing it Csikszentmihalyi (Citation2005). Literature has established that flow experience in terms of balancing challenges and skills, concentration on the task at hand and perceived control, contribute to happiness at the workplace (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, Citation1989; Youssef & Luthans, Citation2007; Pallant, Citation2005). In this regard, this study discusses whether flow experience has an effect on PsyCap and happiness at the workplace. Flow experience is an area that has had a flourish of research within the past couple of decades. Literature from the sports psychology shows that flow experience has continued to have a strong presence in that field since 2000 (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, Citation2008). Apart from sports psychology, flow experience is an emerging area in research (Asakawa, Citation2010). According to flow theory, the activity-inducing flow becomes autotelic (worth doing for its own benefit), an effect later found in the work setting and connected to work satisfaction (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, Citation1989).

The current study is guided by the conceptualization that flow experience mediates the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace. Drawing from the theories of PsyFT and BBT to explain the role of flow experience and happiness at the workplace, both theories assume positive emotions (Lyubomirsky, Citation2005; Seligman, Citation2002). Literature has further established that PsyCap and work-related flow would inspire the employees to work with more enthusiasm and happiness at the workplace (Youssef & Luthans, Citation2007). According to Fredrickson (Citation2001), individuals experiencing high levels of work-role fit perceive their jobs to be a calling and are willing to go beyond occupational restraints to accomplish tasks. For example, a sense of meaningfulness usually acts as an intrinsic motivation and makes employees work more happily, thus increasing employees’ happiness and making their work enjoyable. When employees feel free to schedule their work and freely determine which method to use, they may experience a higher level of positive emotions and this may enhance their level of personal engagement and enjoyment (Luthans & Jensen, Citation2005). Studies such as Seligman (Citation2002) and Lyubomirsky (Citation2005) reveal that flow experience plays a role in mediating the effects of PsyCap on happiness at the workplace. In this study, an attempt is made to support previous scholars’ findings as discussed above and we thus hypothesize that:

H1:

There is a significant and positive relationship between PsyCap and flow experience

H2:

There is a significant positive relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace.

H3:

There is a significant positive relationship between flow experience and happiness at the workplace.

H4:

Flow experience significantly mediates the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace.

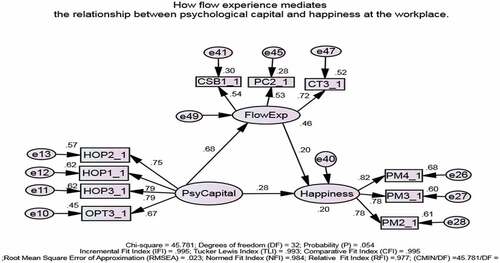

Arising out of this literature review, the model in Figure was developed to guide this study.

3. Methods

3.1. Research design, population, sample, and data collection

This study adopted a cross-sectional research design. The study population was 900 professional nurses employed in public hospitals in Uganda. These professional nurses were selected from public hospitals in the three regions of Uganda. Uganda has four regions, that is to say, central region, western, northern and eastern regions. The study considered the central, western and northern regions because they have the highest numbers of public hospitals and professional nurses (Uganda Bureau of Statistics [UBOS], Citation2016). Purposive sampling approach was employed to identify professional nurses who perform particular roles. All professional nurses were considered for the study and thus given questionnaires. The data collection exercise was conducted between January and May 2018. The questionnaires were distributed to the participants by the authors with assistance from research assistants. In the process of recruiting research assistants, emphasis was put on their experience in data collection. The research assistants first underwent a two-day training on the research topic and on the data collection process. The research assistants were given hard copies of printed questionnaires, lists of hospitals to visit and the respondents. The research assistants were under supervision of the authors of this work. Each respondent was given a questionnaire to complete. Because of the nature of hospital operations, the participants could not complete the questionnaire in a single day and therefore were given ample time to complete the questionnaire. After distributing the questionnaires, some participants could ask for more time and the research assistant, and in some cases, the authors themselves would go back to the participant to collect the completed questionnaires. Out of the 900 questionnaires distributed, 800 usable questionnaires were returned giving a response rate of 88.8%. The high response rate is due to the ample time given to the respondents and the several call-backs made. A thorough check of the questionnaire would be done before the author and/or research assistant leave the participant. This was aimed at avoiding incomplete questionnaires. Those professional nurses who were not able to complete the questionnaire or were not interested in participating in the study were not coerced to participate and thus no questionnaires were picked from them. To identify the professional nurses, the authors and the research assistants would first identify themselves to the medical superintendent (head of the hospital) and would ask for a list of nurses in the hospital and the medical superintendent would help the authors to get access to the nurses through delegating officers in the human resource offices. The interactions between the data collectors and the participants would fully be in isolation with the officers of human resource or medical superintendent. The sample characteristics are reported in Table which is provided under Section 4.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

3.2. The questionnaire, reliability, validity, and variable measurements

The study used a questionnaire to enlist responses from respondents. The questionnaire was used because of its popularity in collecting data from a large sample. Further, the study used a questionnaire because the information supplied in it only passes through the hands of the data gatherers and thus confidentiality of information is maintained. Questionnaires can be in close answer format or open answer format. Given that this study aimed at calculating the mean ratings of statements designed on a six-point Likert scale, a closed answer format questionnaire was used. The questionnaire items were subjected to reliability tests and according to Cronbach (Citation1951) and Hair, William, Barry, et al. (Citation2010), questionnaire items whose Cronbach's alpha coefficient is 0.7 and above are considered reliable. For this study, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients were 0.85, 0.83, and 0.84 for happiness at the workplace, flow experience, and PsyCap, respectively. For validity tests, questionnaires were given to experts in practice and various scholars. These made changes to the items and the questionnaire was revised accordingly. The questionnaire was given to the experts before going to the field. Therefore, the revised questionnaire was used for data collection and after data collection, Cronbach's alpha was computed.

The dependent variable for this study is happiness at the workplace which was operationalized in terms of meaningfulness, personal engagement, life satisfaction, and positive emotions and this was in line with the works of Diener and Seligman (Citation2002). Flow experience was operationalized in terms of challenge and skill balance, concentration on the task and perceived control, and this was adopted from Csikszentmihalyi (Citation2005). Psycap was operationalized in terms of hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy, and this was based on scales developed by Luthans et al. (Citation2007). Response options for all the study variables were based on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = always without fail to 6 = never less than a quarter of the time. The six-point scale was used to avoid undecided responses from respondents’ who might want to stick in the middle.

3.3. Data management and analysis

Data management was consistent with the recommendations by Field (Citation2009). In particular, data were cleaned, coded and entered in a statistical package for social scientists data editor. The data were analysed through Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS). The authors of this study checked for missing values and also outliers which are data points (observations) that do not fit the trend shown by the remaining data (Anderson, Kudela, Cho, Bergey, & Franaszczuk, Citation2007). The outliers bias the mean and inflate the standard deviation (Field, Citation2009). Field (Citation2009) explains several options for dealing with outliers. These options include deleting the data from the person who contributed to the outlier, transforming the data or changing the score and this involves changing the score to be one unit above the next highest score in the data set, calculating what score would give rise to a z-score of 3.29 or using the mean plus two times the standard deviation (rather than three times the standard deviation) (Field, Citation2009). In this study, outliers were dealt with through calculating what score would give rise to a z-score of 3.29 (or perhaps 3) by rearranging the z-score equation in section 1.7.4, which gives us X= (z× s) + X-. All this means is that we calculate the mean (X-) and standard deviation (s) of the data; we know that z is 3 (or 3.29 if you want to be exact) so we just add three times the standard deviation to the mean, and replace our outliers with that score.

Because the questionnaires were checked by the authors and research assistants before leaving the respondents, there were no missing values in the data set. The assumptions of normality, the linearity of data and homogeneity of variance were found to be tenable. For example, the assumption of homogeneity of variance was tested for using the Levene’s test and for the variables of interest; the Levene’s test was not significant at p > 0.05.

According to Hair, William, Barry, Rolph, and Ronald (Citation2010), structural equation model (SEM) involves constructing a model that combines the manifest and latent variables of all the global variables into a single model for decision-making in AMOS through bootstrap. Hair et al. (Citation2010) recommend that two competing models should be constructed to determine the model that is better for decision-making. Additionally, Preacher & Hayes also recommend that the p-values should be used to determine the type of mediation effect that exists and for full mediation, p< 0.001 and for partial mediation the p< 0.005. Thus, in order to establish the mediating role of flow experience in the relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace, an SEM model combining the independent variable (psychological capital), mediator variable (flow experience), and dependent variable (happiness at the workplace) was constructed. The results are indicated in the next section.

4. Results

4.1. Sample characteristics

The results from this study indicated that majority (40%) of the respondents were in the 31–40 age bracket as compared to those who were in the 20–30 age bracket. Besides, the results also showed that majority (77%) of the respondents were female as compared to the male who comprised 23%. Furthermore, the results also revealed that most (51%) of the respondents had attained a certificate level of education as compared to those with a master's degree (0.8%). In addition, the results also indicated that most of the respondents (62%) were located in the central region as compared to those from the western region (9%). Similarly, the results also showed that most (64%) of the respondents were general nurses as compared to the registered nurses who constituted only 1.6%. More so, the results also showed that majority (62%) of the respondents were married as compared to 3.5% who were in a relationship. The results of the sample characteristics are shown in Table .

4.2. Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics were generated to show how the observed data fitted well to the model developed under this study. The results from the descriptive statistics analysis indicated that the variable of psychological capital had a mean = 2.87 and standard deviation = 0.814, while flow experience had a mean = 2.21 and standard deviation = 0.626, and happiness at the workplace at a mean = 2.18 and standard deviation = 0.619. The descriptive statistics results revealed that all the variables had their means not far from the standard deviation. This implies that the observed data fitted well to the model developed under this study since the means were far from the standard deviation as the measure of central tendency. Furthermore, statistics were also generated for the Skewness and Kurtosis. The rule of thumb is that the figures for both the Skewness and Kurtosis for normal data should range between −3.29 and 3.29 (Field, Citation2009). However, Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007) suggest that Skewness and Kurtosis statistics for normal distribution should range between −2 and +2 although a more lenient +3 to −3 can also show normality. The results from this study showed that Skewness and Kurtosis statistics were achieved and tenable since they ranged between −2 and +2 as stipulated by Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007). The results are indicated in Table .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

4.3. Correlation analysis

The second stage of analysis involved Pearson correlation analysis (shown in Table ) to explore the relationship between the predictor and outcome variables. Table results indicate that there is a significant positive relationship between PsyCap and flow experience (r = .58**, p < 0.01). This implies that a positive change in PsyCap may lead to a change in flow experience. This provides support for H1 which states that PsyCap and flow experience are positively and significantly related. Results further indicate that flow experience is positively and significantly associated with happiness at work (r = .63**, p < 0.01). This means that a unit change in flow experience may lead to a .63 change in happiness at work in the same direction. This finding provides support for H2 which states that there is a significant positive relationship between flow experience and happiness at the workplace. Finally, PsyCap and happiness at work are positively and significantly associated (r = .53**, p < 0.01). The implication is that an increase in the level of PsyCap may lead to an increase in happiness at the workplace. This provides support for H3 which states that there is a significant positive relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace. The age which is treated as a control variable in this study was found to be negatively but significantly associated with happiness at work.

Table 3. Correlation analysis

4.4. Testing for mediation using the SEM bootstrap approach

4.4.1. Measurement model

The measurement models were constructed prior to testing of the mediation effect through SEM bootstrap approach in AMOS. The measurement model was constructed to show how the manifest variables are linked well to the latent global variable of psychological capital. The results indicated good model fit indices with Chi-square = 53.302; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.962; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.976; Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 0.976; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.062. Besides, another measurement model was constructed to show how the manifest variables link well to the latent global variable of flow experience. The results indicated a good model fit indices with Chi-square = 72.166; TLI = 0.935; CFI = 0.961; IFI = 0.961; RMSEA = 0.064. Furthermore, measurement model for happiness at the workplace was constructed to show how the manifest variables linked it. The results also indicated a good model fit indices with Chi-square = 47.531; TLI = 0.972; CFI = 0.983; IFI = 0.983; RMSEA = 0.047 (See Table )

Table 4. SEM competing models for non-mediation and mediation effects

4.4.2. SEM model for mediating effect

The results of the structural equation model revealed a perfect model fit indices with Chi-square = 45.781; TLI = 0.993; CFI = 0.995; IFI = 0.995; RMSEA = 0.023. Besides, the results showed that there is a significant and positive relationship between psychological capital and flow experience (β = 0.361, p-value = 0.0001). Thus, this supports hypothesis H1 of this study. Similarly, the results from this study indicated that there is a significant and positive relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace (β = 0.245, p-value = 0.001). This is in line with hypothesis H2 under this study. The results from this study also show that there is a significant and positive relationship between flow experience and happiness at the workplace (β = 0.331, p-value = 0.001). This lends support to hypothesis H3 of this study. Finally, the results indicate that flow experience significantly and positively mediates the relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace and it is a partial type of mediation effect (β = 0.137, p-value < 0.05) (Tables and ). This supports hypothesis H4 of the study. The inclusion of flow experience in the model explains 20% of the variation in happiness at the workplace. When flow experience is included into the model, it boosts the explanatory power of psychological capital on happiness at the workplace by 13.7% (Figure ).

Table 5. Total, direct and indirect effects in an SEM mediated model

Table 6. Bootstrap mediation results

5. Discussion

This study contributes to the existing literature on happiness at the workplace, psychological capital and the role of flow experience on the relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace. Based on the hypothesis H1, this study finds that there is a positive and significant relationship between psychological capital and flow experience among professional nurses’ in public hospitals in Uganda. These findings are consistent with Luthans et al. (Citation2007) who found that an employee with PsyCap has an improved flow experience. The finding suggests that employees, who are resilient at work, are able to balance challenges and skills and experience concentration on the task.

Further, the results for H2 also show that there is a significant positive relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace. This implies that hopeful employees are happy at the workplace. The finding is consistent with Seligman (Citation2011), Luthans and Lansons (Citation2006) and Windle (Citation2011) who noted that hopeful employees are happy at their workplace.

Based on H3, the results revealed that there is a significant positive relationship between flow experience and happiness at the workplace. Indeed, Avey, Luthans, and Jensen (Citation2009) noted that when experience flow is strong, employees' involvement on the tasks may be easily observed, resulting in feelings of joy, which in turn encourage flow experience.

Regarding H4 on the mediation role of flow experience, the results indicate partial and significant mediation effect of flow experience on the relationship between psychological capital and happiness at the workplace among professional nurses in public hospitals. This means that whereas PsyCap is directly associated with happiness at the workplace, its contribution can be partly felt through flow experience. This is in line with Luthans et al. (Citation2007) who argued that when employees feel part and parcel of the tasks performed at work, they would be more likely to feel involved in the organization through greater concentration on the tasks, balancing challenges and skills and in turn, displaying better positive feelings and joy.

6. Summary and conclusion

The current study examined the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace, and the mediation role of flow experience in the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace. Through the self-administered questionnaire, 800 professional nurses were selected in Uganda’s three regions, central, western, and northern, to be part of the study. The current study hypothesized that there is a positive relationship between PsyCap and flow experience, PsyCap, and happiness at the workplace, flow experience and happiness at the workplace. We also hypothesized that flow experience mediates the relationship between PsyCap and happiness at the workplace. Our results supported the hypotheses developed. This current study recommends that those in charge of public hospitals in Uganda should not just focus on employee happiness, but should consider the flow experience of professional nurses. This is because flow experience has been found in this paper to have a significant impact on professional nurse’s happiness. As flow experience increases, professional nurses are more engaged and happier.

The study combined two theories, BBT and PsyFT by Fredrickson (Citation2001) and Ryan and Deci (Citation2002), respectively, to explain happiness at the workplace. Therefore, the integration of the two theories has provided a more robust understanding of happiness at work and what explains it. This study is beneficial to human resource managers of public hospitals who deal with health employees. They should redesign the recruitment system and policies that can boost PsyCap and flow experience in order to promote happiness at the workplace among professional nurses in Uganda. Having professional nurses who possess PsyCap helps them cope with poor public hospital environment through impacting their flow experience. It could be coherent that PsyCap strengths can be used as a tool by professional nurses to sustain their positive emotions. Thus, it is beneficial for public hospital managers and policy makers to have happier professional nurses.

Like any other study, this study also has limitations which are discussed alongside suggestions for future studies. First, the research only considered professional nurses in the public health sector in Uganda and did not consider other categories of medical workers, like medical doctors, clinical officers, administrators, support staff, and even professional nurses in private medical practice. These could be used as samples in future studies. This research only focuses on two factors that predict happiness at the workplace that is PsyCap and flow experience. Future studies can consider other factors that predict happiness at the workplace, such as environmental factors and self-driven personality (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2005; Luthans, Citation2002) among other factors. Future researchers should be interested in finding out other factors that predict happiness at the workplace in developing countries like Uganda. In addition, this study focused only on cross-sectional data; thus, a longitudinal study and experiments may be used in future research. Besides, the current study was purely quantitative; therefore, a qualitative survey or a mixed methods design may be utilized in future.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Charles Kawalya

Charles Kawalya is a lecturer in the Department of Human resource Management at Makerere University Business School. His research interests are in organizational and positive psychology.

John C Munene

Prof John Munene. (PhD) is a professor of organizational psychology at Makerere University Business School, Director PhD Programmes and HR consultant. His research focuses on positive psychology.

Joseph Ntayi

Prof Joseph Ntay. (PhD) is professor of procurement and business strategy and Dean of Faculty of Economics, Energy and Management Science. He is a scholar in strategy.

James Kagaari

Prof. James Kagaari. (PhD), a professor of organizational psychology at Makerere University Business School. His research focuses on organizational psychology.

Sam Mafabi

Dr. Sam Mafabi (PhD) is a senior lecturer in organizational Behaviour at Makerere University Business School. His research interests include positive psychology and knowledge management.

Francis Kasekende

Dr. Francis Kasekende (PhD) is a senior lecturer at Makerere University Business School. His research include psychological capital and organizational development.

References

- Anderson, W. S., Kudela, P., Cho, J., Bergey, G. K., & Franaszczuk, P. J. (2007). Studies of stimulus parameters for seizure disruption using neural network simulations. Biological Cybernetics, 9(7), 173–13. doi:10.1007/s00422-007-0166-0

- Asakawa, K. (2010). Flow experience, culture, and well-being: How do autotelic Japanese college students feel, behave, and think in their daily lives? Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(2), 205–223. doi:10.1007/s10902-008-9132-3

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Jensen, S. (2009). Psychological Capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resource Management, 4(8), 677–693. doi:10.1002/hrm.20294

- Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work and Stress, 2(2), 187–200. doi:10.1080/02678370802393649

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Cronbach, L.J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988). Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2005). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2005). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(6), 815–822. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.815

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy employees. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00415

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd edn). London: Sage.

- Field, A. (2010). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- Fisher, C. D. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 384–412. doi:10.1111/ijmr.2010.12.issue-4

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 4(8), 39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotion in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 5(6), 218–226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). The value of positive emotions. American Scientist Hand Book.

- Fullagar, C. J., & Kelloway, E. K. (2009). Flow at work: An experience sampling approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 595–615. doi:10.1348/096317908X357903

- Hair, J. F., William, C. B., Barry, B. J., Rolph, E. A., & Ronald, L. T. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education Inc.

- Hair, J.F, William, C.B, Barry, B.J, Roph, E.A, & Ronald, L.T. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. In Nj (6th ed.). Pearson Education Inc: Upper Saddle River.

- Jessica, P. J. (2010). Happiness at work: Maximizing your psychological capital for success (1st ed.). Kindle-edition US-Amazon.

- Joo, B. K., & Lee, I. (2017). Workplace happiness: Work engagement, career satisfaction, and subjective well-being. Evidence-based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 5(2), 206–221. doi:10.1108/EBHRM-04-2015-0011

- Kagaari, J., & Munene, J. C. (2007). Engineering lecturers’ competencies and organizational citizenship behaviours at Kyambogo University. Journal of European Industrial Training, 31(9), 706–726. doi:10.1108/03090590710846675

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 3(3), 697–724.

- Kahn, W. A. (1992). To be fully there: Psychological presence at work. Human Relations, 4(5), 321–349. doi:10.1177/001872679204500402

- Luthans, F. (2002). Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive, 1(6), 57–72l.

- Luthans, F., & Avolio, B. J. (2009). The “point” of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(2), 291–307. doi:10.1002/job.v30:2

- Luthans, F., & Lansons. (2006). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(3), 695–706.

- Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2007). Psychological capital. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- Luthans, K. W., & Jensen, S. M. (2005). The linkage between psychological capital and commitment to the organizational mission: A study of nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration, 35(6), 304–310. doi:10.1097/00005110-200506000-00007

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2005). The how of happiness. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Lyubomirsky, S., & Sheldon, K. M. (2012). The challenge of staying happier: Testing the hedonic adaptation prevention model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(5), 670–680. doi:10.1177/0146167212436400

- Malik, A. (2013). Efficacy, hope, optimism and resilience at workplace-positive organizational behavior. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 3(10), 1–4.

- McMahon. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Review, 12(4), 384–412. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00270.x

- Pallant, J. (2005). Development and validation of a scale to measure perceived control of internal states. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(2), 308–370. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA7502_10

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effect in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. doi:10.3758/BF03206553

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 5(5), 68–78. 71.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon: New York, NY.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). (2016). National population and housing census. Kampala: UBOS. Retrieved from http://www.ubos.org/onlinefiles/uploads/ubos/NPHC/NPHC%202014%20PROVISIONA L%20RESULTS%20REPORT.

- Windle, G. (2011). The resilience network. What is resilience? A systematic review and concept analysis. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 2(1), 1–18.

- Youssef, C. M., & Luthans, F. (2007). Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. Journal of Management, 33(5), 774–800. doi:10.1177/0149206307305562