?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The scope of financial development has been expanding and moving gradually towards a more inclusive development thus attention is gradually shifting to financial inclusion. It is against this background that this study investigates the role of migrants’ remittances on financial inclusion in selected SSA countries. Pooled Mean Group (PMG) form of panel ARDL was employed but cross-sectional dependent characteristics of the data required the use of cross-sectional methods that cater for such properties. Consequently, XTDCCE: Dynamic Common Correlated Effects and XTCCE Common Correlated Effects estimator were used as robustness checks. For the purpose of this empirical investigation, we collected data on Remittances, Account Ownership and Income Per Capita for 27 SSA countries based on data availability. The conclusion is that remittances have no significant effect on financial inclusion in SSA. However, the variable demonstrates the potential to positively influence financial inclusion. Thus, there should be concrete policy efforts in the SSA to make remittances count for inclusive growth. The study contributes substantially by moving attention from a broad concept of financial development to Financial Inclusion and employed a more recent panel estimating techniques to investigate the nexus between remittances and Inclusion.

Keywords:

JEL CLASSIFICATION:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Many developing economies especially African countries do not have enough domestic investment to move their economies to the desired level of economic growth and prosperity and thus rely heavily on capital inflows. Remittances serve as a major source of capital inflows for many developing economies both for consumption and investment purposes. Apart from this direct effect, other benefits that have been identified as spillovers of remittances include financial development and inclusions. The two concept borders on size and sophistication of financial services and accessibility of these services to the people. This study basically verified if these benefits (financial development and inclusion) are derivable from remittances in African countries as popularly discussed. However, the outcome of the study does not support the hypothesis that remittances improve financial development and inclusion in African countries.

1. Introduction

Migration of skilled and unskilled labour from many developing countries to more developed countries has its pros and cons. It is very easy to posit that developing countries are likely to face the shortage of skilled and unskilled labour as a result of migration. However, the role remittances as a major source of capital inflows in these countries are often not taken into consideration. Thus, a robust discussion of migration should be analysed viz-a-viz with the issue of remittances. The issue of remittances has been widely considered in many global public debates, with scholars such as Gupta, Pattillo, and Wagh (Citation2007), Singh, Haacker, Lee, and Le Goff (Citation2010), Adams and Klobodu (Citation2016), and many others, emphasizing its importance to economic growth and development. Basically, remittances as a construct in this study refer to transfers that are entailed in the Balance of Payments (BOPs) of a country. They comprise transfers by migrants, employees’ compensation and private transfers between countries (Awad, Citation2009). However, informal channels such as postal money orders and private money changers have been identified and these channels comprise up 75%, at least 35% of official transfers among countries (Freund & Spatafora, Citation2008).

Sub-Sahara African (SSA) countries have not been categorised as a significant receipt of remittances. Among the top 25 remittances recipient countries, only Nigeria is in SSA. Nevertheless, there are some countries in the region whose remittance inflow constitutes a larger proportion of their GDP, these include Lesotho—27.3%, Togo—10.1%, Senegal—9 .8%, Cape Verde—9.0%, and The Gambia—8.2%. The issue of under-reporting of remittance in the region is also a big problem. Remittances data are mostly not available, for instance, remittance information are available for less than one-third and two-third of African and SSA countries, respectively; often remittances via informal channels are not captured. However, the region has made substantial progress in terms of remittances inflows over the years. Specifically, the region was estimated to witness 3.4, 3.7 and 3.7 in 2016, 2017 and 2018 respectively in remittance growth rate.

In recent times, attention has been given to different channels through which remittances interact with economic growth in developing countries. Some of the channels, as discussed in the literature include household consumption, investment, and national saving, exchange rate and financial development. The nexus between remittances and financial development has been widely discussed in the region compared to other channels. Several extant studies have examined the link by using different measures of financial development. The major conclusion from these studies is that financial development responds positively to remittance inflow.

Also, studies in this area usually label remittance as an exogenous factor to domestic variables in developing countries. This assumption may not hold because other domestic variables may have a strong influence on remittances. Take for instance: a strong and viable financial sector in home countries can enable a cheap cost of transfer for the senders. An active financial sector can also make for easy access to funding for the recipient, and this is capable of facilitating increased remittances in such an economy. This draws attention to the causal relationship between remittances and financial development. This in line with Demirgüç-Kunt, Córdova, Peria, and Woodruff (Citation2011) which argued financial sector developments, using aggregate data, is subject to at least some form of endogeneity bias.

This study contributes to literature fundamentally by attempting to investigate the causal relationship between financial inclusion and remittances, especially in large SSA countries, and estimate their relationship. In doing this, the study is not unaware of the fact that some studies, such as Toxopeus and Lensink (Citation2007) and Aga and Martinez Peria (Citation2014) have attempted to investigate the connecting links from remittances to financial inclusion at a cross-sectional level in developing countries. This study, however, presents a fresh insight, especially in the way it concentrates on 27 selected SSA countries. This gives room for rigorous and more focused analysis on the nexus between remittances and financial inclusion, and by extension, assessing the extent of the latter in the SSA. In explaining financial inclusion, the study aligned with the definition provided by Beck, Demirguc-Kunt, and Levine (Citation2009) which described “financial inclusion as the availability and equality of opportunities to access financial services”.

At this juncture, there is a need to provide distinction and link between financial development which is a popular concept in development economic literature and financial inclusion which is gradually attracting more empirical attention in recent times. According to Demirguc-Kunt, Klapper, and Singer (Citation2017) “financial inclusion implies that all adult members of the society are granted access to a range of proper financial services, designed based on their needs and provided at affordable costs”. Based on this definition, financial inclusion has measured by array of variables including percentage of adults that have an account at a formal financial institution and percentage of adults that had a loan from a financial institution. On the other hand, financial development as defined by Hacıoğlu, Dinçer, and Olgu (Citation2015) is the development in the size, efficiency and stability of and access to the financial system. On the account of this definition, the issue of size, efficiency and stability of the financial system are core issues in financial development while the issue of accessibility is a key in financial inclusion. However, financial inclusion is an integral part of financial development.

Beyond this introductory section of the paper, there are four other sections that make up the paper. Section two centres on the discussion of literature from extant studies, section three presents data and methodology. Section four discusses the empirical findings and section five concludes with research contribution and policy implications.

2. Literature review

2.1. Stylized facts of remittances and financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa

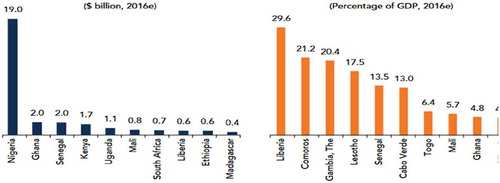

Following Ratha, Eigen-Zucchi, and Plaza (Citation2016), as shown in figure one, remittance flows to SSA Africa have declined. Specifically, it was estimated to decline by 6.1% and reached $33 billion in 2016. Several factors have been advanced for this nose-diving trend in the flow of remittances into the area. The most important of these factors is the poor economic performances in remittance-sending countries. Many European countries that have absorbed large migrants from the region have not been doing well economically. Another factor, as elucidated in the World Bank 2016 report, is the decline in commodity prices, majorly the price of crude oil. This has a great impact on the countries receiving remittances from regional commodity exporters such as Saudi Arabia. Also, one of the factors is the exchange rate regime in remittance-receiving countries in the region, especially Nigeria. The inconsistency in exchange rate policies, characterized by overregulated exchange regime in many of these countries, has caused the diversion of remittances to informal channels.

Moreover, the cost of remittances in SSA has been reported to be very high in caparison with other areas of the world. In the sub-region, the mean remittance costs raised from 9.7% in 2016 Q1 to 9.8% in 2017 Q1 (Ratha et al., Citation2016). This makes the region the highest in the world. Unfortunately, intraregional remittances transfer corridor was reported to be most expensive in 2017, especially in countries such as Angola and Namibia—27%, South Africa and Botswana—21%, Nigeria and Mali—20%. This makes it extremely difficult to bring the cost of transaction below 3%−5% in the region, as envisaged in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, with the increase in oil prices and much improved global economic activities in 2017 and 2018, remittances to the sub-region were estimated to rise by 3.3%. Specifically, remittances to a country like Nigeria, considered being the largest in the region (see Figure ) are estimated to rise by 1.9%. Also, Ghana, being the second largest is estimated to receive 3.1% more, while Senegal occupying the third position is estimated to experience an additional 2.6% in remittance inflows.

Figure 1. Flow of Remittance in SSA countries

The array of reports on financial development has shown that SSA and Africa at large have made a substantial improvement in the financial system. However, examining the comparison of private credit to GDP indicates that there is a wide gap with fellow developing economies (World Bank, Citation2012). According to the same report, private credit to GDP ratio constituted around 24% of GDP in SSA Africa in 2010 this is considered very small compared with 77% for all fellow developing economies, and 172% obtainable in high-income economies. Using the stock market as another indicator of financial development, about 50% of African countries have stock markets and very few of them considered to be liquid (Beck et al., Citation2009). When the market capitalization of these stock markets is compared with other markets in other regions of the world, market capitalization to GDP is around 38%, excluding South Africa, as against 44% in fellow developing economies and 62% obtainable in high-income economies (World Bank, Citation2012).

Apart from the financial development indicators mentioned above, financial inclusion is gradually becoming another big issue in SSA. Many reports on financial inclusion have shown that the region is not performing well on all inclusion indicators, and this may be one of the reasons for non-inclusive growth in the region. Africa in general, according to Demirguc-Kunt and Klapper (Citation2012) reported that 23% of adults in Africa have an account at a formal financial institution. According to Massara and Mialou (Citation2014) in the IMF report, the report shows that only 34% of the population has bank accounts in the sub-region, as against 94% in high-income countries. Just 7.3% of the SSA population were reported to use the formal account to receive their salaries. Within SSA, large variation in account ownership has been reported, 42% in Southern Africa as compared to 7% in Central Africa. In 2017, Global Findex data show that within SSA, adults with a financial institution account enjoyed a moderate increase of 4% points since 2014 and mobile money account has risen more than twice precisely 9% points.

2.2. Empirical literature

Generally, developing countries are the major beneficiaries of remittances; thus, most works of literature featured here are based on them. Most importantly, the link between remittances vis a vis financial development has been extensively discussed in the literature amidst controversies. Most of the controversies arise from channels through which remittances influence financial development and the direction of causality between the variables. Also, in the reviewed literature, financial development has been measured using different proxies, and this has influenced research outcomes which have made it difficult to achieve a consensus as regards the relationship between remittances and financial development.

Studies by Freund and Spatafora (Citation2008) and Giuliano and Ruiz-Arranz (Citation2009), for instance, observed that the remittances can serve as a complement for investment if channelled into productive activities, with high returns when there is a functional financial system. Contrarily, the contribution of remittances may be insignificant, if it fails to ease the liquidity constraints in the financial system which makes it possible to release resources for productive engagements. However, most studies have argued that irrespective of the channel, remittances contribute to financial development and, by extension, economic growth.

Likewise, studies by Mundaca (Citation2009), Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (Citation2011) and Rao and Hassan (Citation2011) pointed out that there exists a direct relationship between remittances and financial development. Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (Citation2011) argued in a more specific term that remittances facilitate financial development, due to the positive association that exists between remittances and savings which by extension increases the bank credit. On the same plane, Mundaca (Citation2009) averred that the existence of complementarity between remittances and financial development is a precondition for growth enhancement. This position is also maintained by Nyamongo, Misati, Kipyegon, and Ndirangu (Citation2012) in a similar study using data from Sub-Saharan African. However, a study by Karikari, Mensah, and Harvey (Citation2016) differs markedly in this regard. In taking a different stance, their study focused more on the causal relationship between remittances and financial development in 50 selected African countries. They revealed that certain aspects of financial development are stimulated by remittances, while a better financial system fosters receipts of remittances.

Apart from these panel studies, country-specific studies have also demonstrated elements of controversy. The link between remittance inflows and development of the financial sector in Nigeria was examined by Oke, Uadiale, and Okpala (Citation2011). The data employed in the study cover 1977 to 2009. The study revealed that remittance inflows exert a substantial effect on the development of the financial sector. A similar study conducted in Bangladesh by Chowdhurry in 2011 assesses the relevance of remittances to the development of the financial sector. In the study, the link between financial development and remittances was assessed using the cointegration analysis and the vector error correction model. His conclusion is that Bangladesh’s financial system has benefited from the increase in remittance inflows.

However, some scholars have expressed reservations about the effect of remittances on financial development. Bettin, Lucchetti, and Zazzaro (Citation2012) employed a behavioural model of household’s remittances to analyse the interaction between remittance and financial development in the home country. The study argued that an inefficient financial sector in the home country may inhibit immigrants’ trust to transfer large amounts. With this submission, reversed causality has been established between remittances and financial development. A similar study by Sibindi (Citation2014) examined the direction of causality between financial development and remittances, concluding that the causal relationship runs from financial development to remittances without feedback, using data from Lesotho.

In recent times, studies are looking at the causal link between remittances and financial development. For example, Chowdhury (Citation2016), using dynamic panel estimation established that remittances can be effective for promoting growth but financial variables. The study submitted that more developed financial systems may attract more remittances. In the same manner, Fromentin (Citation2017) investigated the dynamic interaction between remittances and financial development in Latin America and the Caribbean countries, using Granger causality test and panel non-causality test. The conclusion of the study is that there is a positive and bi-directional link between remittances and financial development. In the same argument, a country-specific study undertaken by Khurshid, Kedong, Călin, and Popovici (Citation2017) shows the causal link between remittances and financial development.

Recently, financial inclusion is becoming an important part of financial development; thus, studies are emerging that seem to be interested in the link between remittance and financial inclusion, especially in developing countries. Toxopeus and Lensink (Citation2007) used system equation estimates to examine if when controlled for financial inclusion, whether remittances have a developmental effect in developing countries. The study found evidence supporting the objective. Also, Anzoategui, Demirgüç-Kunt & Martínez Pería (Citation2011) explored the nexus between international remittances and financial inclusion in El Salvador by using aggregate data on bank credit and deposit amounts over the period 1975–2007 for 109 developing countries. They reported evidence of linkage between remittances and financial inclusion.

Also, Aga and Martinez Peria (Citation2014) assessed the effect of remittances on financial inclusion in five selected SSA countries (Burkina Faso, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Uganda) comprising about 10,000 households using survey data. They concluded that the chances of a household opening a bank account is largely influenced by international remittances in the five SSA countries. However, Ambrosius & Cuecuecha (Citation2016) in the country-specific study examined the effect of remittances on formal and informal financial services usage using Mexican household data. They submitted that remittances greatly influence the ownership of savings account.

3. Data and methodology

To execute empirical analysis for this study, the following data were employed; Adult with bank account per one thousand, credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP, per capita Remittances and per capita GDP. Financial inclusion as the dependent variable was proxy by an adult with bank account per one thousand. Similarly, the second dependent variable (financial development) was proxy by credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP. Also, per capita remittances measured by international inflow of remittances is our key independent. Per capita GDP was introduced as the control variable. Additional independent variables were also obtained from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Development Indicators (WDI) databases which also served sources for all the data.

In all, two models were estimated. In the first model, 27 SSA countries were included in a balanced panel analysis. These countries were selected based on data available for the period 1990 to 2016. The countries included comprises Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Comoros, Congo, Dem. Congo Rep., Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo and Uganda. The data employed in the second model just like first model ranged from 1990 to 2016. To prevent endogeneity bias in this study, the direction of causality between remittances and financial inclusion was thoroughly investigated using Dumitrescu and Hurlin (Citation2012). The Dumitrescu Hurlin Panel Granger Causality was also used due to the existence of cross-sectional dependence in the data. Subsequently, the relationship among the variables was investigated using Panel ARDL and robustness was also performed, following Chudik and Pesaran (Citation2015) panel estimation that accounts for heterogeneity and cross-sectional dependence in panel data. In addition, the PMG form of panel ARDL was specifically employed due to the short-time nature of data used in this study.

3.1. Specification model

Following a similar study in this area, data employed in this study have both cross-sectional and time-series features. These data were used to study the possible relationship between account opening and independent variables of remittances and GDP per capita in the first model. In the second model, the credit to the private sector serves as dependent variables and remittances and GDP per capita were employed as independent variables. Functionally, the equations estimated can be expressed as follows:

Pooled Mean Group (PMG) can be formulated as follows:

In equation three, the cross section is represented by i = 1, 2, …… N and time is denoted by = 1,2, …… T. Also, denoted the vector of regressors. While

and

are used to represent the parameters of vectors for scalars and external variables with an inherent feature of a group-specific effect. Furthermore,

represents the disturbance terms. If these disturbance term co-integrated, then it is an I(0) process. This characteristic suggests that error correction dynamics of the variables in the system moves away from equilibrium, and consequently, equation three can be re-specified to account for error correction thus:

= 1,2, …. N, and

= 1, 2, …., T, where

Stacking the time series observation for each group, Equationequation (4)4

4 becomes

The error correction parameter is denoted by and it is indicative of the speed of adjustment. Introducing dependent and independent variables in Equationequation 3

3

3 , our Pooled Mean Group (PMG) takes this form for the first model;

In error correction form, we have

and for the second model

Again in error correction form, we have

3.1.1. Properties of data

In an effort to base our estimation on sound econometric analysis, we subjected our data to preliminary econometric tests of cross-sectional dependence, panel unit root tests and co-integration tests. The results are presented in table one, two and three below.

3.1.2. Cross-sectional dependence results

In line with Pesaran (Citation2004), we investigated the cross-dependence of our data using a battery of cross-dependence tests and the results are reported in Table .

Table 1. Cross-Sectional Dependence Results

Given the cross-sectional dependence tests, it is impossible to accept the null hypothesis that our data are cross-sectional independent. We particularly focused on the result from Pesaran CD because of the characteristic of panel data such that N > T. However, all results of CD tests were uniform, attesting to the fact that there is the presence of cross-sectional dependence in the data. Based on these outcomes, the second generation of unit root tests, particularly Pesaran cross-sectional augmented panel unit root test (CIPS), will be required to test for stationarity. This is due to the fact the assumption of cross-sectional independence proposed in the first generation of unit root tests is too restrictive for macro series. This may cause to size distortions and low power (Hurlin & Mignon, Citation2007). Pesaran (Citation2007) CIPS unit root test results are given below in Table .

Table 2. Pesaran (Citation2007) CIPS Test

Pesaran CIPS test follows Dickey–Fuller regression augmented with the cross-section average of lagged levels of the individual series. The approach also assumes one or more common unobserved factors producing cross-country dependence. Persiaran CIPS results as presented in Table indicate the rejection of the unit root hypothesis for all the variables, especially at lag 0 and 1. This shows that Account opening, remittances and credit to the private sector are all stationary at first difference and GDP per capita at level.

Similarly, the presence of cross-sectional dependence and unit root in the variables necessitates the need to adopt co-integration tests with the capability to resolve the problems. In recent literature focusing, Westerlund (Citation2007) co-integration test has been credited with such capability. For the purpose of this study, Westerlund (Citation2007) and Westerlund and Edgerton (Citation2007) were utilized to investigate co-integration in our variables. The central purpose of the test is to check for the presence of co-integration, by determining whether or not the individual panel members are error-correcting. Also, these tests allow for heterogeneity among the units forming the panel. To enable comparison, the results of traditional co-integration tests, specifically Pedroni (Citation1999, Citation2004)), are reported alongside Westerlund (Citation2007) and Westerlund and Edgerton (Citation2007). The two results are reported in Tables and for both models 1 and 2.

Table 3. (Model 1) Panel Co-Integration Tests results

Table 4. Error-Correction Panel Co-Integration Test Results (Model 1)

The results of Pedroni (Citation1999, Citation2004), as reported in Table , indicate the rejection of the hypothesis of no co-integration, especially between dimension at a critical level of 5%, for the two models. Similarly, the results from Westerlund (Citation2007) and Westerlund and Edgerton (Citation2007) presented in Table show that we can reject the hypothesis of no co-integration for the two models at 10%, despite accounting for cross-sectional dependence in the two models with. Thus, it is convenient to say that there is a long-run relationship among the variables.

Given all the preliminary investigations, the models were found to be suitable for necessary estimations. Before estimating our model, we tested for causality direction between the two major variables in our models, in line with the point made at the background to this study. Based on the econometric properties of the data, we employed Dumitrescu and Hurlin (Citation2012) Granger non-causality panel procedure. The test is particularly designed for heterogeneous panel data and it has proven to produce consistent and unbiased results in the face of a small sample and cross-sectional dependence. The results of causality tests are reported in Tables and for models 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 5. Dumitrescu And Hurlin (Citation2012) Granger non-causality results: Model (1)

Table 6. Dumitrescu And Hurlin (Citation2012) Granger non-causality results: Model (2)

In the Granger non-causality results, as presented in Table upper parts, the results show that the hypothesis of Granger non-causality can be rejected between remittances and financial inclusion for SSA countries. This indicates that remittances Granger-cause inclusion for at least one panelvar (id). In terms of causality, this implies that the past of value of remittance can help predict financial inclusion proxy by account opening in SSA. Also, we explored the possibility of reversed causality between the two variables. The results, as reported in Table lower parts, show that it can similarly reject the hypothesis of Granger non-causality from inclusion to remittances. This shows that there is a reversed causality from inclusion to remittances. In general, the results from the two tests indicate bi-directional causality between remittances and inclusion proxy by account opening, and this can pose a serious challenge for model estimation. On the other hand, the results from the second model basically indicate unidirectional causality from remittances to financial inclusion proxy by a credit to the private sector.

4. Research findings

As specified in the model specification, Panel ARDL was used as a method of estimation. Specifically, we employed Pooled Mean Group (PMG) to estimate both long and short-run effects of remittances on financial inclusion proxy by account penetration and credit to the private sector in two different models. Estimation results from the two models are presented in Tables and . Most importantly, in an attempt to obtain reliable results from our estimations and due to the presence of cross-sectional dependence in our data, other estimation techniques were also employed. Precisely, we used xtdcce stata code, as developed by Jan Ditzen to implement Pesaran (Citation2006) and Chudik & Pesaran (Citation2015). xtdcce provides for (Pooled) Mean Group estimations in a dynamic panel, with consideration for dependence between countries. It also corrects small sample time series bias by using Recursive Mean Adjustment, as suggested by Chudik & Pesaran (Citation2015). The results are presented jointly with PMG results in Tables and .

The results from Table indicate that remittance has a positive effect on financial inclusion, both in the short-run and long-run. However, the results as presented show that remittances do not have a statistically significant effect on financial inclusion as a proxy by account penetration. Considerably, remittances do have a considerable effect in the long-run using PMG estimation method. But, this same position does not hold when other estimation techniques that take care of cross-sectional dependence are employed. Estimations from xtdcce by Ditzen (Citation2016) and xtcce dynamic CCE by Neal (Citation2015) show that there is no significant effect of remittance on financial inclusion as a proxy by account penetration, both in the long-run and short-run. However, both methods indicate that remittances have positive on financial inclusion.

Table 7. FI (Account Penetration)

Table 8. FI (Credit to Private Sector)

Similarly, the results in Table show that remittances have a positive effect on financial inclusion. Using the PMG estimation method, the results show that there is a statistically significant effect of remittance on financial inclusion, only in the short-run. However, this does not apply in the long-run. Considerably, the results from other estimation techniques, such as xtdcce by Ditzen (Citation2016) and xtcce dynamic CCE by Neal (Citation2015) contradict PMG estimation results. The results show that remittances do not have a significant positive effect on financial inclusion. Since these methods account for cross-sectional dependence identified in our data, we are left with no option than to base our conclusion and policy prescriptions on the results from xtdcce by Ditzen (Citation2016) and xtcce dynamic CCE by Neal (Citation2015) estimation techniques.

5. Conclusion

5.1. Research contribution and implications

After thorough econometric analyses of our data, the study concludes that remittances have the potential to explain changes in financial inclusion. To be sure, remittances have the potentials to positively influence financial inclusion in SSA. However, this potential has not been fully harnessed; given the fact that empirical shreds of evidence show that remittances have no significant effect on financial inclusion in the SSA African region. This assertion aligns with another related study within and outside the region taken for consideration in this paper. A position such as this has been well explored by scholars, including Anzoategui, Demirguc-Kunt, and Peria (Citation2011), Brown, Carmignani, and Fayad (Citation2013), and Coulibaly (Citation2015). It is pertinent to also note that the views articulated by these scholars contradict the findings of similar studies, especially those of Toxopeus & Lensink (Citation2007), Anzoategui, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Pería (Citation2011), Karikari et al. (Citation2016), and Nyanhete (Citation2017). Based on these findings, the study has been able to contribute to the literature by establishing the existence of positive interaction between financial inclusion and remittances but such interaction is not significant. However, the study has provided a shift of attention from financial development to financial inclusion which is a more pressing issue in the region.

The core set of policy intervention that can be employed in both countries of origin and host countries includes:

Reducing cost and risk of money transfer for migrants. This will go a long way in reducing transfer through unregulated channels.

Financial education for migrants with a focus on providing information about existing financial products that meet their needs and also raise awareness on unregulated remittance transfer risks and solutions.

Financial education should also be provided to recipients in host countries in order to build the capability to make the best use of remittances.

Authorities, especially remittances receiving countries in SSA should devise an innovative system, such as EcCash Diaspora service that is offered by Econet Wireless in Zimbabwe, so as to attract more remittances from their migrants.

5.2. Research limitation and future works

There is a paucity of secondary data on financial inclusion for many SSA African countries and the available data are not extended in terms of periods. This can create a methodological challenge for researchers. More countries and periods would have been included in the study but for the paucity of data. Future study can include more countries and more variables especially those variables that focus more on the use of financial services rather than access to financial services as employed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lukman.O. Oyelami

Lukman Oyeyinka Oyelami is a lecturer at Economic Unit, Distance Learning Institute and adjunct Research economist with the Institute of Nigeria-China development studies, University of Lagos. He bagged his Ph.D from the prestigious Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-ife. He currently teaches Macroeconomics, International trade and Econometrics.

Adeyemi A. Ogundipe

Adeyemi A. Ogundipe holds a PhD in Economics, with specific focus on Resource Economics and Economic Dynamics. He currently lectures and conducts research at Covenant University in the Department of Economics and Development Studies, Nigeria. He is also a research fellow at the Covenant University Centre for Economic Policy and Development Research (CEPDeR).

References

- Adams, S., & Klobodu, E. K. M. (2016). Remittances, regime durability and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Economic Analysis and Policy, 50, 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2016.01.002

- Aga, G., & Martinez Peria, M. (2014). International remittances and financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa (No. 6991). The World Bank. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-6991

- Ambrosius, C., & Cuecuecha, A. (2016). Remittances and the use of formal and informal financial services. World development, issue C, 80–89.

- Anzoategui, D., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Pería, M. S. M. (2011). Remittances and financial inclusion: Evidence from El Salvador. World Development, 54, 338–349. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10986/3603

- Awad, I. (2009). The global economic crisis and migrant workers: Impact and response. International labour office, International Migration Programme, Geneva: ILO. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---actrav/documents/publication/wcms_112967.pdf

- Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2009). Financial institutions and markets across countries and over time-data and analysis (No. 4943). The World Bank. Retrieved from ftp://wbftpx02.worldbank.org/pub/repec/SSRN/staging/4943.pdf

- Bettin, G., Lucchetti, R., & Zazzaro, A. (2012). Endogeneity and sample selection in a model for remittances. Journal of Development Economics, 99(2), 370–384. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.05.001

- Brown, R. P., Carmignani, F., & Fayad, G. (2013). Migrants’ remittances and financial development: Macro‐and micro‐level evidence of a perverse relationship. The World Economy, 36(5), 636–660. doi:10.1111/twec.12016

- Chowdhury, M. (2016). Financial development, remittances and economic growth: Evidence using a dynamic panel estimation. Margin: the Journal of Applied Economic Research, 10(1), 35–54. doi:10.1177/0973801015612666

- Chudik, A., & Pesaran, M. H. (2015). Common correlated effects estimation of heterogeneous dynamic panel data models with weakly exogenous regressors. Journal of Econometrics, 188(2), 393–420. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2015.03.007

- Coulibaly, D. (2015). Remittances and financial development in Sub-Saharan African countries: A system approach. Economic Modelling, 45, 249–258. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2014.12.005

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Córdova, E. L., Peria, M. S. M., & Woodruff, C. (2011). Remittances and banking sector breadth and depth: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 95(2), 229–241. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.04.002

- Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Klapper, L. (2012). Financial inclusion in Africa: An overview (No. 6088). The World Bank. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/534321468332946450/pdf/WPS6088.pdf

- Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Singer, D. (2017). Financial inclusion and inclusive growth: A review of recent empirical evidence(English). Policy Research working paper; no. WPS 8040. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/403611493134249446/Financial-inclusion-and-inclusive-growth-a-review-of-recent-empirical-evidence

- Ditzen, J. (2016). xtdcce: Estimating dynamic common correlated effects in Stata. The Spatial Economics and Econometrics Centre (SEEC). Retrieved from http://seec.hw.ac.uk/images/discussionpapers/SEEC_DiscussionPaper_No8.pdf

- Dumitrescu, E. I., & Hurlin, C. (2012). Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Economic Modelling, 29(4), 1450–1460. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2012.02.014

- Freund, C., & Spatafora, N. (2008). Remittances, transaction costs, and informality. Journal of Development Economics, 86(2), 356–366. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.09.002

- Fromentin, V. (2017). The long-run and short-run impacts of remittances on financial development in developing countries. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 66, 192–201. doi:10.1016/j.qref.2017.02.006

- Giuliano, P., & Ruiz-Arranz, M. (2009). Remittances, financial development, and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 90(1), 144152. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.10.005

- Gupta, S., Pattillo, C. A., & Wagh, S. (2007). Impact of remittances on poverty and financial development in Sub-Saharan Africa (No. 7-38). International Monetary Fund. Retrieve from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=20428

- Hacıoğlu, Ü., Dinçer, H., & Olgu, Ö. (2015). Evaluation of branch-based efficiency in Turkish deposit banks: Evidence from privately-owned banks. In Handbook of research on strategic developments and regulatory practice in global finance (pp. 64–74). Hershey, PA: IGI Global. doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-7288-8.ch007

- Hurlin, C., & Mignon, V. (2007). Second Generation Panel Unit Root Tests. (No. halshs-00159842). doi:10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0467B

- Karikari, N. K., Mensah, S., & Harvey, S. K. (2016). Do remittances promote financial development in Africa? SpringerPlus, 5(1), 1011. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2658-7

- Khurshid, A., Kedong, Y., Călin, A. C., & Popovici, O. C. (2017). A note on the relationship linking remittances and financial development in Pakistan. Financial Studies, 21(4). Retrieved from ftp://www.ipe.ro/RePEc/vls/vls_pdf/vol21i4p6-26.pdf

- Massara, M. A., & Mialou, A. (2014). Assessing countries’ financial inclusion standing-A new composite index (No. 14-36). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.678.5013&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Mundaca, B. G. (2009). Remittances, financial market development, and economic growth: The case of Latin America and the Caribbean. Review of Development Economics, 13(2), 288–303. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9361.2008.00487.x

- Neal, T. (2015). Estimating heterogeneous coefficients in panel data models with endogenous regressors and common factors. Workblacking Paper.

- Nyamongo, E. M., Misati, R. N., Kipyegon, L., & Ndirangu, L. (2012). Remittances, financial development and economic growth in Africa. Journal of Economics and Business, 64(3), 240–260. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2012.01.001

- Nyanhete, A. (2017). The role of international mobile remittances in promoting financial inclusion and development. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 6(2), 256. doi:10.14207/ejsd.2017.v6n2p256

- Oke, B. O., Uadiale, O. M., & Okpala, O. P. (2011). Impact of workers’ remittances on financial development in Nigeria. International Business Research, 4(4), 218. doi:10.5539/ibr.v4n4p218

- Pedroni, P. (1999). Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61(S1), 653–670. doi:10.1111/1468-0084.0610s1653

- Pedroni, P. (2004). Panel cointegration: Asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series test with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Econometric Theory, 20(3), 597–625. doi:10.1017/S0266466604203073

- Pesaran, M. H. (2004). General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in Panels (No. 1240). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). Retrieved from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/18868/1/cesifo1_wp1229.pdf

- Pesaran, M. H. (2006). Estimation and inference in large heterogeneous panels with a multifactor error structure. Econometrica, 74(4), 967–1012. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0262.2006.00692.x

- Pesaran, M. H. (2007). A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. Journal of Applied Economics, 22(2), 265–312. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Rao, B. B., & Hassan, G. M. (2011). A panel data analysis of the growth effects of remittances. Economic Modelling, 28(1–2), 701–709. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2010.05.011

- Ratha, D., De, S., Plaza, S., Schuettler, K., Shaw, W., Wyss, H., & Yi, S. (2016). Migration and remittances: Recent developments and outlook. Migration and Development Brief, 26, 4–6. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0913-2

- Ratha, D., Eigen-Zucchi, C., & Plaza, S. (2016). Migration and remittances factbook 2016. World Bank Publications. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0319-2

- Sibindi, A. B. (2014). Remittances, financial development and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Lesotho. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 116. Retrieved from https://virtusinterpress.org/IMG/pdf/10-22495_jgr_v3_i4_c1_p4.pdf

- Singh, R. J., Haacker, M., Lee, K. W., & Le Goff, M. (2010). Determinants and macroeconomic impact of remittances in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Economies, 20(2), 312–340. doi:10.1093/jae/ejq039

- Toxopeus, H. S., & Lensink, R. (2007). Remittances and financial inclusion in development. WIDER Research Paper 2007/49. UNU-WIDER. Retreived from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/63621/1/546116124.pdf

- Westerlund, J. (2007). Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69(6), 709–748. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.2007.00477.x

- Westerlund, J., & Edgerton, D. L. (2007). A panel bootstrap cointegration test. Economics Letters, 97(3), 185–190. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2007.03.003

- World Bank. 2012. Global Financial Development Report 2013: Rethinking the Role of the State in Finance. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retreived from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11848