Abstract

This paper conceptualizes and operationalizes alliance justice capability (AJC) as a second order firm-level capability consisting of three distinct yet related first-order firm level skills which foster procedural justice (PJ), distributive justice (DJ) and interactional justice (IJ) in the relationship between alliance partners. The paper then goes on to test how AJC affects alliance performance, mediated by inter-firm affective commitment and calculative commitment. This model is tested via a survey that yielded 154 complete responses from alliance managers in the Indian Information Technology sector. The data was analysed with structural equation modelling using Mplus. Research findings partially validate the theoretical model put forward in this paper demonstrating the mediating role of affective commitment in the relationship between AJC and alliance performance.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper puts forward a new driver of strategic alliance performance by conceptualizing and operationalizing an alliance justice capability construct. Strategic alliances are increasingly important in the current economic environment where, due to a variety of reasons, organizations need to ally with other organizations to stay competitive and viable. Unfortunately, a significant number of these alliances fail to meet their objectives. This paper goes some way in helping organizations to better understand their alliances and subsequently improve their returns from alliances.

1. Introduction

In this interconnected and hyper-competitive world, alliances are becoming increasingly important for organizations. Unfortunately, not all of these alliances achieve their stated goals or potential (Gomes, Barnes, & Mahmood, Citation2016; Wang & Dyball, Citation2019). One under-researched aspect of alliances is justice (Dong, Zou, Sun, & Zhang, Citation2019). The importance of organizational justice is well accepted (Dong et al., Citation2019; Konovsky, Citation2000; Liu, Aroean, & Ko, Citation2019; Narasimhan, Narayanan, & Srinivasan, Citation2013). The presence of justice in a relationship has been shown to elicit commitment from partners (Johnson, Korsgaard, & Sapienza, Citation2002), reduce opportunistic behaviour (Luo, Citation2008) and help alleviate relational uncertainty (Luo, Liu, Yang, Maksimov, & Hou, Citation2015) leading to longer term exchanges and positive performance outcomes (Carnovale, Henke, DuHadway, & Yeniyurt, Citation2019).

The roots of organizational justice research can be traced back to a paper by Adams (Citation1965) which underlined the importance of perception of fairness outcomes by employees of an organization. In subsequent research (Dong et al., Citation2019; Greenberg, Citation1987; Holtz & Harold, Citation2011; Kim & Mauborgne, Citation1993; Roch & Shanock, Citation2006) this type of justice came to be known as distributive justice (DJ), that is, fair distribution of rewards and outcomes, within a relevant entity; be it a group, firm, or a network of firms. DJ is the oldest type of justice and operates on the principle that parties (individuals/firms) involved in a transaction are affected by whether the outcomes have been fairly distributed with regards to the resources invested by the concerned parties (Carnovale et al., Citation2019; Luo, Citation2007).

Further development of research in this area identified a second type of justice which has to do with the fairness of procedures followed rather than the fair distribution of rewards (Dong et al., Citation2019; Thibaut & Walker, Citation1975). This type of justice came to be known as procedural justice (PJ). PJ therefore refers to the fairness of the procedures that lead to a decision outcome without regards to the outcome itself (Liu et al., Citation2019; McFarlin & Sweeney, Citation1992). The basic premise here is that, irrespective of the outcome, individuals are affected by the perceived fairness of the procedures (Carnovale et al., Citation2019; Folger & Konovsky, Citation1989). So even if the final outcome is unfavourable, a person who believes that the process has been fair is likely to accept the outcome much more favourably compared to a person who believes that the process has been unfair (Lind, Allan, & Tyler, Citation1988).

As the organizational research advanced even further, a third distinct type of justice, namely interactional justice (IJ), was conceptualised (Carnovale et al., Citation2019; Roch & Shanock, Citation2006). IJ refers to the perception of an individual as to how he or she was treated, typically by a supervisor, in an organization (Roch & Shanock, Citation2006). Extant literature considers IJ to be distinct from PJ and DJ (Colquitt, Citation2001; Liu et al., Citation2019; Luo, Citation2007).

Although the area of organisational justice has seen an upswing in research, it can be noted that a majority of research has been at the micro level, that is, at the employee level, with limited research at the meso-level, that is, inter-firm level (Luo, Citation2007). Indeed, organizational justice research at the meso level of strategic alliances has been scarce. This paper addresses this paucity of justice research in the specific context of alliances. We conceptualise and then operationalise alliance justice capability (AJC) as a second-order firm-level capability which conceptualizes the three major facets of justice, namely PJ, DJ and IJ, as interlinked in the relationship between two partners. Based on data from 154 strategic alliances in India, we find that firm level AJC is positively associated with alliance performance (AP). Furthermore, we also find that this positive association is mediated by inter-firm commitment and in particular affective commitment (AC).

This paper adds to the confluence of the organizational justice and strategic alliance literature. We answer the call from recent researchers to further explore the impact of justice components on alliance performance outcomes in different industry and country contexts (Dong et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2019). Additionally, and more importantly, we contend that AJC can in fact be conceptualized as a second order firm level capability comprising of three first order firm-level skills namely PJ, DJ and IJ. To the best of our knowledge, this is one the first studies which conceptualizes and then operationalizes justice as a firm level capability. We argue that if, in an alliance context, a focal firm takes unilateral action to foster the three types of justice in an alliance relationship, it leads to the development of AC and calculative commitment (CC) in the relationship between alliance partners and also positively contributes to AP. Indeed, unilateral positive action by a focal firm has been shown to have a reciprocal positive impact on alliance level performance outcomes (Bello, Katsikeas, & Robson, Citation2010; Cullen, Johnson, & Sakano, Citation2000; Heimeriks, Citation2008). We also add to the literature by considering how, in contrast to existing scholarship (Johnson et al., Citation2002; Liu, Huang, Luo, & Zhao, Citation2012), different forms of commitment are affected by justice perceptions.

Our paper unfolds as follows. The paper begins with a review of the pertinent literature in the area of organizational justice, commitment and performance. Next the hypotheses are developed in detail. The sampling strategy and survey methodology are then described before presenting the results. Finally, the outcomes of the research are discussed, managerial implications are identified and conclusions drawn.

2. Literature review

2.1. Organizational justice

The basic principle behind justice theories is that fairness in the organizational workspace holds importance for the employees as well as organizations and affects how they work (Carnovale et al., Citation2019; Colquitt, Citation2001; Konovsky, Citation2000). In the context of alliances, DJ refers to the fair distribution of outcomes to the parties involved (Dong et al., Citation2019). The underlying theoretical paradigm comes from equity theory which contends that people compare the distribution of rewards to the amount of resources contributed by them and other team members involved (Adams, Citation1965). If a member receives more than what it contributed it is deemed to have been overpaid. On the other hand, if the member receives less than what it contributed it is deemed to have been underpaid (Carnovale et al., Citation2019). Satisfaction is achieved if the division of outcomes reflects the efforts and contribution by a party (Greenberg, Citation1990; Leventhal, Citation1976). The concept of DJ holds importance in the context of alliances because rewards can be monetary (profit) as well as non-monetary (knowledge/learning) (Luo, Citation2007). The contract between alliance partners often does not govern all possibilities, especially in longer term relationships, and eventually it is the relationship between alliance partners that prevails. In this context the fair sharing of non-monetary rewards, in-addition to the monetary rewards, becomes vital for smooth alliance functioning (Dong et al., Citation2019).

Following a different line of reasoning PJ contends that the degree of fairness in processes is a major determinant of people’s reaction to that decision (Liu et al., Citation2019). In an alliance context Luo (Citation2005, p. 696) defines PJ as “the fairness of an alliance’s strategic decision-making process and the procedures that influence each party’s gains and interests, as perceived by the boundary spanners who represent each party”. It is distinct from DJ in that the focus is on fairness of procedures instead of the final outcomes (Carnovale et al., Citation2019). Although outcome is no doubt important extant literature contends that the perceived fairness of the procedures is equally, if not more, important (Dong et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2019; Yadong Luo, Citation2007).

In addition to PJ and DJ, IJ has also been shown by extant research to have significant performance outcomes (Luo, Citation2007). In the context of alliances Luo (Citation2007, p. 647) defines it as the “extent to which interpersonal treatment and information exchange between boundary spanners representing each party are fair”. IJ thus entails that the alliance partners’ representatives (especially the boundary spanners) are treated in a respectful manner taking care of social sensitivities involved. Whereas PJ is more concerned with the formal aspect of the exchange process, IJ is concerned with the social aspects of the exchange process including respect, honesty and dignity (Colquitt, Citation2001; Luo, Citation2007).

The firm level skill that ensures DJ entails that the focal firm takes measures to make sure that the rewards and returns generated from an alliance are shared fairly with its alliance partner(s). This basically implies that partners get a share that reflects their contribution towards the alliance in terms of resources, responsibilities and efforts. The firm level skill to ensure PJ entails that the focal firm takes measures to ensure that the procedures concerning important decision-making procedures of the alliance are fair and just (Wang, Craighead, & Li, Citation2014). The firm level skill that ensures IJ entails a firm having the ability to make sure that its partners are treated in a respectful manner taking care of the social sensitivities involved.

We contend that a firm level capability that ensures fairness between alliance partners via firm-level processes, during the alliance management phase, leads to positive alliance performance outcomes. We name this capability, at alliance level, alliance justice capability (AJC), that is, the firm level capability which ensures that alliance partner feels that the procedures have been transparent and just, that the rewards, if any, have been distributed fairly and that the relationship between the boundary spanners has been cordial and respectful. Thus, we envisage AJC as a second order capability that consists of three distinct yet related first order firm level procedures or skills namely PJ, DJ and IJ, answering a call from Luo et al. (Citation2015) regarding the lack of research on justice, as a key aspect of relationships.

2.2. Commitment

Commitment has been put forward as a key constituent in inter-firm relations (Bello et al., Citation2010; Sluyts, Matthyssens, Martens, & Streukens, Citation2011). Skarmeas, Katsikeas, and Schlegelmilch (Citation2002) contend that commitment signifies the desire to continue the relationship over a long time, willingness to sacrifice for the benefit of the relationship, expectation in its continuity and belief in the importance of the relationship. A relationship that is based on mutual commitment is likely to get full cooperation of partners since partners are less likely to indulge in opportunistic behaviour or hold back cooperation in the belief that the partnership is going to last and the other partner(s) is serious in maintaining it for mutual benefit (Cullen, Johnson, & Sakano, Citation1995).

Styles, Patterson, and Ahmed (Citation2008) see commitment as consisting of two major components namely AC and CC building on the seminal research by Meyer and Allen (Citation1991). The affective or attitudinal component of the commitment is concerned with the care shown by a partner for the alliance (Bloemer, Pluymaekers, & Odekerken, Citation2013; McFarlin & Sweeney, Citation1992). CC is conceptualized as deriving from the side bets associated with a perceived lack of alternatives (Becker, Citation1960) as well as the perceived costs associated with leaving (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, Citation2002). At an alliance level, this calculative or rational element of commitment arises from the expectations and concerns of a focal firm with respect to the cost and benefits associated with an alliance (Styles et al., Citation2008).

2.3. AP

Measuring the performance of a strategic alliance has always been a complex task as there is no unanimity in the literature as to what constitutes AP and therefore how to correctly measure AP (Arino, Citation2003; Glaister & Buckley, Citation1998; Nielsen, Citation2007). There are theoretical as well as methodological differences associated with AP measurement including differences in opinion as to which factors constitute AP (Inkpen, Citation2001; Nielsen, Citation2007; Ren, Gray, & Kim, Citation2009), data collection issues (Gulati, Citation1998; Lunnan & Haugland, Citation2008) and multifaceted nature of the alliances themselves (Christoffersen, Citation2013; Ren et al., Citation2009).

However, there is a general consensus in the literature that AP can primarily be measured either objectively or subjectively. AP can be measured objectively by analysing secondary data including return on investment or changes in the share price of the focal firm over a period of time (Glaister & Buckley, Citation1998). A subjective measurement of AP entails asking the alliance manager, directly involved in handling the day-to-day alliance matters, about her/his opinion on the state of the alliance. Altough it is fairly obvious that objective and subjective measurement of AP represent two very different methods of measuring AP, past research suggests that there is a high degree of correllation, ranging from 0.4 to 0.8, among these two measures (Guthrie, Citation2001; Richard, Devinney, Yip, & Johnson, Citation2009). We have measured AP using a subjective measure by asking the opinion of the alliance manager directly involved in the daily management and running of the alliance.

3. Hypotheses development

3.1. AJC

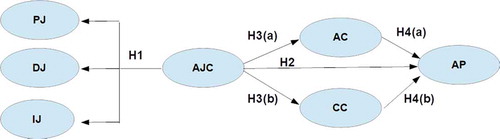

There is a general consensus in the literature that organizational justice can be primarily categorized into three related yet distinct types namely PJ, DJ and IJ. Consequently, we hypothesise that AJC is a second order capability that consists of these three distinct yet related firm-level skills (see the left-hand side Figure below).

In an alliance setting DJ entails that the rewards of an alliance are distributed fairly in proportion to the amount of resources devoted to the alliance by all the partners (Yadong Luo, Citation2007). Following this it is argued that the DJ component of AJC entails that the focal firm takes measures to ensure that the rewards and returns generated from an alliance are shared fairly with its alliance partner(s). This basically implies that partners get a share that reflects their contribution towards the alliance in terms of resources, responsibilities and efforts.

In addition to DJ there is widespread support in the extant research for the importance of PJ (Johnson et al., Citation2002; Kim & Mauborgne, Citation1993; Konovsky, Citation2000; Thibaut & Walker, Citation1975). In this context it is argued that the PJ component of AJC entails that the focal firm takes measures to ensure that the procedures concerning important decision-making procedures of the alliance are fair and just. If a focal firm conducts its alliance operations in a transparent and fair manner, it assuages the anxieties of its partner firm.

IJ resides at an individual level and refers to the perception of an individual as to how he or she was treated, typically by a supervisor, in an organization (Roch & Shanock, Citation2006). In the context of alliances Luo (Citation2007, p. 647) defines it as the “extent to which interpersonal treatment and information exchange between boundary spanners representing each party are fair”. The IJ component of AJC thus entails a firm having the ability to make sure that its partners are treated in a respectful manner taking care of social sensitivities involved. So, whereas PJ is concerned with the formal aspect of the exchange process, IJ is concerned with the social aspect of the exchange process such as respect, honesty and dignity (Colquitt, Citation2001; Luo, Citation2007).

This provides the first hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1: AJC is a second order capability comprising of three distinct first order firm level skills namely PJ, DJ and IJ.

3.2. AJC and AP

In an alliance context justice signifies to a focal firm that an alliance partner is not taking undue advantage of the relationship thus helping in reducing transaction costs and ultimately enhancing the performance outcomes (Yadong Luo, Citation2008). Research has shown a positive association between all three types of organizational justice constructs, namely PJ, DJ and IJ, and alliance functioning in general (Ariño & Ring, Citation2010) and AP outcomes in particular (Dong et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2019; Luo, Citation2007; Wang & Dyball, Citation2019). This leads us to the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: A firm’s AJC is positively associated with AP.

3.3. AJC and commitment

Commitment signifies to a focal firm that its alliance partner intends to stay in the relationship for the long term and is willing to go the extra mile for the benefit of the relationship. The extant research has focussed on two primary aspects of inter-firm commitment namely AC and CC (Styles et al., Citation2008). This affective component of commitment comes from an alliance partner caring for the relationship (Bloemer et al., Citation2013; McFarlin & Sweeney, Citation1992). Extant research (Johnson et al., Citation2002; Luo, Citation2009) has found a significant relationship between forms of justice and commitment where commitment was measured as a mix of AC and CC. Liu et al. (Citation2012) found that each form of justice (DJ, PJ, and IJ) had a significant effect on a general measure of commitment. In an inter-organisational context, Gomes et al (Citation2017) found that PJ and IJ independently had a significant positive relationship with AC. Based on this stream of research, we hypothesise as follows:

Hypothesis 3(a): A firm’s AJC is positively associated with AC.

The calculative or rational commitment arises from the expectations and concerns of a focal firm with respect to the costs and benefits associated with remaining in an alliance (Ganesan, Brown, Mariadoss, & Ho, Citation2010; Holm, Eriksson, & Johanson, Citation1999). As previously noted, commitment, as measured by AC and CC combined, has been found to have a significant relationship (Johnson et al., Citation2002) with justice, a result confirmed by Luo (Citation2009). Gomes et al (Citation2017) found a positive significant relationship between PJ and IJ and CC in an inter-firm context.

Hypothesis 3(b): A firm’s AJC is positively associated with CC.

3.4. Commitment and AP

Commitment entails a firm thinking on a long-term basis, in the context of an alliance. When a focal firm is committed to the relationship it removes the fears of the partner-firm with regards to opportunism. Partners think on a longer-term basis which helps in the full potential of the alliance being realized. Commitment signifies that the alliance partners have internalized the alliance relationship (Cullen et al., Citation2000). Consequently, partners would be more willing to invest in the relationship thus leading to better AP outcomes. Empirical evidence has shown that commitment, in general, leads to performance (Lohtia, Bello, Yamada, & Gilliland, Citation2005; Nakos & Brouthers, Citation2008; Sarkar, Echambadi, Cavusgil, & Aulakh, Citation2001; Skarmeas et al., Citation2002) all found commitment positively associated with performance. These results are borne out by a large-scale review of the literature which finds a positive relationship between both forms of commitment and AP (Christoffersen, Citation2013). In an early paper, Kumar, Hibbard, and Stern (Citation1994) investigated the effects of commitment on performance and found that, relative to calculative commitment, affective commitment had a stronger positive effect on performance in a distribution channel context. Thus, we argue that presence of AC and CC would lead to positive AP outcomes. This leads to the following set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4(a): AC is positively associated with AP.

Hypothesis 4(b): CC is positively associated with AP.

4. Method

4.1. Data collection

The firms from the Indian information technology (IT) industry were used for testing the model. This was done for a variety of reasons. First, even though the Indian IT industry has seen remarkable progress over the last two decades or so, not many studies in academia analyse this growth. This is especially surprising since it is a very dynamic sector with internal and external competition growing by the day (Nadkarni & Herrmann, Citation2010). With entry barriers crumbling and many countries trying to imitate the Indian model (e.g. Russia, Poland, China, Philippines), Indian firms are trying hard to place themselves in a position where they can add substantial value to their partners and clients that cannot be easily imitated by the competition. One of the major ways is by entering into a long-term partnership. Second, IT industry firms typically have many partnerships (Glaister & Buckley, Citation1998; Schreiner, Kale, & Corsten, Citation2009). In the context of the Indian IT industry, many firms have partnerships/alliances with big technology firms such as IBM, Microsoft, SAP and Oracle. Third, the world today stands at the crossroads of a seismic shift where the balance of power is slowly but steadily shifting from western economies to the economies in Asia, South America and Africa. In this context, India provides a developing economy setting that is slowly but surely taking off as an economic powerhouse.

To obtain the target population of alliances of Indian IT-services firms, three primary sources were used namely Capitaline, NASSCOM and websites of large technology vendors, such as Microsoft, Oracle and SAP. Following this 994 firms were identified that had a strategic partnership with another company. The 994 firms were individually called to (i) determine and/or confirm if the focal firm had a partnership and (ii) to get the name and details (email/office address) of the person who would be the most knowledgeable about the working of that partnership. Additionally, the professional networking site LinkedIn was used to verify the profiles of the respondents. The respondents were chosen carefully, keeping in mind previous studies (Kumar et al., Citation1993). The alliance manager was selected as the respondent if such a post existed within a company. In cases where there was no specific post for alliance management a person from the top management of the company (CEO, Director, President) was selected. In the Indian IT sector, a lot of the SMEs are new (10–15 years old) and founded by their CEOs (Nadkarni & Herrmann, Citation2010). The top management is directly involved in the management of their alliances. The executive that was eventually selected had the responsibility of dealing with alliances of her or his firm.

A total of 177 firms (that is 17.8%) were removed from this list because either the firm declined to give details about its partnerships and/or a suitable qualified respondent or the alliance had terminated and the company no longer engaged with a partner to be of interest in this study. Thus 817 firms served as the final sampling frame to which the survey was mailed in late 2011. The final valid response rate for the survey was good at 18.8%, after removing responses which were incomplete.

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Justice measures

PJ, DJ and IJ items were taken from Luo (Citation2007) with adaptions made such as those by Schreiner et al. (Citation2009) to measure the justice as a firm-level capability (See Table ).

4.2.1.1. DJ

Five items were used to measure DJ. The first four items were adapted from Luo (Citation2007) and the last item from Colquitt (Citation2001). These items basically capture the efforts made by the focal firm in ensuring that the rewards/returns of the partnership are shared with its partner in a fair manner. The items measured the efforts made by the focal firm in making sure that the rewards of the partnership are shared in accordance to resources contributed, commitment shown, responsibilities taken and performance delivered.

4.2.1.2. PJ

PJ was measured using nine items. The items were adapted from Luo (Citation2007) and capture the degree to which the focal firm ensures that the various procedures related to the partnership such as making important decisions, planning and managing partnership as well as knowledge and resource sharing are fair and just.

4.2.1.3. IJ

Six items were employed to operationalize IJ. The items were adapted from Luo (Citation2007) and capture the quality of the relationship between the boundary spanners of the two firms involved in the partnership.

4.2.2. Commitment

Commitment items were taken from Styles et al. (Citation2008). Inter-firm commitment was operationalized as a two-dimensional construct, that is, AC and CC. The entire commitment scale from Styles et al. (Citation2008) was used for measuring commitment. Five items were used to measure AC and four items were used to measure CC (See Table ).

4.2.3. AP

AP was measured with items from Krishnan, Martin, and Noorderhaven (Citation2006) with an additional item from Kale and Singh (Citation2007) regarding competitive position (See Table ).

5. Analysis and results

Due to the key informant strategy employed, there is a possibility of common method bias. The use of established scales and proximal separation served to reduce the risk of common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, Citation2012). Confirmatory factor analysis, using a single factor, was conducted to test for common method bias and the result was a very poorly fitting model (χ2 = 1566.580, df = 299, p = 0.000, CFI = 0.527, RMSEA = 0.166, SRMR = 0.139) thus providing evidence for the lack of common method bias.

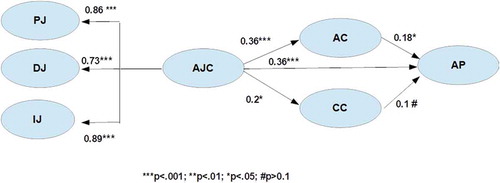

A two-stage approach to the analysis was taken following Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) and Bagozzi and Yi (Citation2012) using MPlus. Measurement models were carried out followed by the estimation of structural models, as per Figure , to test the hypotheses. Confirmatory factor analysis was run for each construct. One item from the AC scale and one item from the CC scale failed to meet reliability requirements in that their factor loadings were below 0.60 (0.459 for the AC item, and 0.059 for the CC item). A measurement model for all constructs with no causal relationships and free covariance estimation between constructs was developed. This showed an acceptable level of fit (χ2 = 886.126, df = 480, p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.074, CFI = 0.890, SRMR = 0.071) providing evidence of convergent validity (O’Leary-Kelly & Vokurka, Citation1998). Further evidence of convergent validity was that all factor loadings were greater than 0.6, the t-values were significantly greater than 2, and each loading was greater than double its standard error (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). Construct validity was assessed, as per Appendix 1 Tables A1-A3, using composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE).

All CR values were over 0.790 and all AVEs were over 0.5 except AC which was very close at 0.498 (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation2012; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). In order to assess discriminant validity, the square roots of the AVE scores were assessed against the inter-construct correlations (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) as per the diagonal of Table . All were higher than the relevant inter-construct correlations, thus providing strong evidence of discriminant validity. High correlations between the three forms of justice were expected given that they are to be modelled as a higher order construct.

Table 1. Inter-construct correlations

The structural model (see Figure ), testing all the six hypotheses, showed an acceptable level of fit (χ2 = 894.498, df = 487, p = 0.000; CFI = 0.889; RMSEA = 0.074; SRMR = 0.074).

All of the hypothesized paths in this paper were found to be significant, except one, (see Table ). We used the approach of Schreiner et al. (Citation2009) to test the validity of our first hypothesis, that is, a second-order factor model of AJC. Consequently, the fit of the AJC-model was compared to two competing models. Firstly, the AJC model was compared to a one factor solution where all the justice items were loaded onto a single factor. The fit indices of this solution showed unsatisfactory values. Secondly, the AJC model was also compared to a first-order three factor solution, where the correlations between factors are constrained, was also tested. It was noted that that the second order AJC factor model provided the best fit. Additionally, the correlations between the first order factors were fairly high overall, as per Table . Similarly, the first order factors showed high loadings on to the second order AJC factor. Overall these results suggest that it is suitable to conceptualize AJC as a multidimensional second-order capability (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988; Schreiner et al., Citation2009). We find support for H2 in that AJC has a significant positive effect on AP (b = 0.361, p = 0.000). We also find support for H3a (b = 0.358, p = 0.000) and H3b (b = 0.201, p = 0.031) showing that AJC has a significant positive effect on both forms of commitment. We find support for H4a (b = 0.184, p = 0.046) but not for H4b (b = 0.098, p = 0.234). As a result, we find a mediating role for AC but not for CC in the relationship between AJC and AP.

Table 2. Results of hypotheses testing

6. Discussion

This study conceptualizes and operationalizes an AJC construct, in the specific context of strategic alliances. The results, from our analysis of data from 154 strategic alliances from the Indian IT sector firms, suggest that it is appropriate to conceptualize AJC as a second-order firm level capability consisting of three first order firm-level skills namely PJ, DJ and IJ. Our results also indicate a strong positive association between AJC and AP. This result is consistent with recent, but limited, research, which focusses on the role of organizational justice components on strategic alliance performance outcomes (Carnovale et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2019; Wang & Dyball, Citation2019).

Our results also suggest that a firm level capability that fosters PJ, DJ and IJ in an alliance, leads to the development of AC as well as CC in the relationship. Our results point to a stronger relationship between AJC and AC compared to AJC and CC. This is not entirely unexpected. The affective or attitudinal component of the commitment comes from an alliance partner caring for the relationship (Bloemer et al., Citation2013; McFarlin & Sweeney, Citation1992). Cullen et al. (Citation2000) argue that the affective component of the inter-organizational commitment has a psychological aspect that pushes an alliance partner to willingly go beyond its contractual obligations to make the alliance succeed. On the other hand, the calculative or rational commitment arises from the expectations and concerns of a focal firm with respect to the cost and benefits associated with an alliance (Styles et al., Citation2008). If a focal firm makes repeated efforts to foster justice at a procedural level, interactional level and with respect to the distribution of end rewards, it is bound to get noticed by the other partner of an alliance. Research has indicated that unilateral positive action does have a reciprocal positive effect on alliance performance (Bello et al., Citation2010; Cullen et al., Citation2000; Heimeriks, Citation2008). We also find that the two forms of commitment have differential effects on AP. We find that in line with the extant literature (Christoffersen, Citation2013; Nakos & Brouthers, Citation2008). The literature strongly suggests that there is a significant positive relationship between CC and AP, though we did not find this in our context using established measures. The outcomes from Kumar et al. (Citation1994) provide some insight in that they found a stronger relationship between AC and AP versus CC and AP, though it should be noted that both relationships in their study were significant.

7. Theoretical and managerial contributions and implications

7.1. Theoretical contributions and implications

This study is timely for a number of reasons. First, our understanding of justice in an alliance context is limited and there are few studies which discuss the impact of all three constituents of organizational justice in the context of alliances. The extant organizational justice literature has focused more on micro-level issues, such as perceptions of justice among employees (Barclay & Kiefer, Citation2014; Holtz & Harold, Citation2011) rather than meso-level issues, such as perceptions of justice between organizations in an inter-firm partnership context (Liu et al., Citation2019; Luo, Citation2007). This is unfortunate since inter-firm partnerships and alliances offer an attractive domain for justice research (Ariño & Ring, Citation2010). This study adds to this significant gap in the literature by conceptualizing a holistic second order AJC construct and empirically testing it.

Second, to the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies which puts forward justice as a firm-level capability. In doing so, we argue that unilateral positive action by an alliance member fosters inter-firm commitment in an alliance relationship in the form of AC and CC ultimately positively impacting AP. Traditionally alliance related studies of commitment have measured individual elements of justice and commitment as a global construct (Gomes et al., Citation2017; Johnson et al., Citation2002; Luo, Citation2009). We add to the literature through considering how justice as a holistic concept affects the different elements of commitment. In this way we provide a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between justice perceptions and commitment in an alliance context. Alliance research has generally found that commitment leads to AP. We show a light on this relationship through investigating the differential effects of AC and CC on AP following Kumar et al. (Citation1994) and differently from the remainder of the literature which takes a more holistic view of the commitment-performance relationship (Christoffersen, Citation2013). We find that while the AC-AP link is significant, the link between CC and AP is not significant. In this way, we add to our understanding of how the different elements of commitment affect AP.

7.2. Managerial contributions and implications

Identifying and assessing a new driver of performance in alliances is an important managerial contribution of this paper. The issue of AJC has been demonstrated in this paper to have a direct effect on performance. Alliance managers need to consider how they can implement procedures to ensure that justice occurs. This is an activity that begins with the alliance formation phase and is likely to continue throughout the alliance. AJC also directly affects the level of commitment, both affective and calculative, and as such is important for the longevity of the alliance as relationship elements such as commitment often replace more strict contractual terms in longer alliances. While developing systems to ensure justice requires resources from the alliance manager, the benefits are potentially long lasting and would be transferrable to other alliances that the organization has.

If a focal firm has the ability to compare levels of justice they experience from different partners, this can affect their commitment to other partners in their alliance portfolio. For example, a focal firm may perceive that it is being treated differently (in terms of justice) by different partners. If one partner is not treating the focal firm fairly, it is likely that the level of both AC and CC of the focal firm with that partner will decrease, with consequent impacts on AP. We posit that our model will need have another aspect in a portfolio context. We would expect that the justice perceptions of similar alliance partners or some approximation of the justice perceptions of the alliance portfolio will affect AJC in the current model. As AJC consists of perceptions, these perceptions are going to be judged against expectations and we expect these expectations will be set based on other members of the alliance portfolio, including how the focal firm feels that it treats its own partners in the portfolio.

As alliances mature, there is a move away from contractual considerations to a more relational social exchange basis. This is evident in many alliances through increasing commitment levels. While the literature suggests that both forms of commitment (AC and CC) are important in determining performance, our research suggests that firms should focus on the affective nature of the relationship and try to bolster this. AC can be bolstered by creating stronger personal bonds between the key participants in each alliance and by giving time to the non-contractual issues that bind partners together. While developing aspects that enhance CC such as exclusivity and dependence are good strategies for managers, our results show that higher AP comes from AC and that efforts to engage in CC may not increase AP.

8. Conclusions, limitations and future research directions

In conclusion, we find that perceptions of justice, as measured through AJC, are an important driver of AP. There is ample evidence that almost half of all inter-firm alliances fail in meeting their stated objectives. The failure rate is particularly high in the case of international alliances (Kaplan, Norton, & Rugelsjoen, Citation2010). While significant effort rightfully goes into the formation and contractual negotiations phase, the longest part of the alliance should be in the management phase. We show that in established alliances justice perceptions are essential for developing higher levels of AC, CC and AP. We find a positive mediating role for AC in the AJC-AP relationship, and interestingly, in contrast to the extant literature no significant relationship between CC and AP. This is an interesting outcome that can be explored in other studies and contexts.

While this paper addresses a major gap in the alliance and justice literature, the findings should be evaluated in light of the following limitations, which limit this study’s generalizability. First, this study was undertaken in the specific context of Indian IT firms. Other industries and geographies may have different dynamics which may change the nature of the capabilities required. Although the IT industry has very similar working procedures in most countries, the dynamics differ compared with other industries, such as, the manufacturing sector. Furthermore, India is an emerging economy and thus different in a variety of ways not only from developed economies but also from major emerging economies, such as, Brazil and China. Our focus on firms in a single sector with relatively common procedures and in a single country has helped to reduce the variance that could be brought about by the cross-cultural nature of alliances.

Second, the alliances that formed the sample for this research were contractual in nature and were primarily technology oriented. Given that strategic alliances include a variety of interfirm agreements such as licensing, R&D agreements and joint ventures (Gulati, Citation1995, Gulati et al., Citation2012), the partner involvement differs considerably across these various types of agreements. Consequently, contract-based alliances and partnerships have different partner dynamics compared to, say, joint ventures that bind the partners more strongly. Although it is likely that the proposed relationship between AJC and alliance performance would hold and perhaps even improve in the case of relationships that are more intense in nature such as joint ventures, this relationship needs to be further tested in multiple settings in order to examine its reliability.

Third, we focussed on single alliances between two partners. It is now common to see multi-partner alliances with alliance partners also from countries outside the national borders of the focal firm. It would therefore be of interest to see how alliance justice capability is understood in this context. Fourth, our alliances were relatively long term in nature and of strategic benefit to the firms involved. Other methods of inter-organisational relationships exist such as international joint ventures and it would be useful to see if similar capabilities evolve in such organisations where there are effectively three parties to the relationship: the initial partners and the joint venture organisation.

This area is a fruitful avenue for future research. It would be of interest to consider an inter-temporal model to understand how justice perceptions change over time. There is also a lack of research, in an alliance context, on how justice perceptions are developed and how expectations in relation to this are set. Our paper is one of the first, in an alliance context, to highlight the differential effects of AC and CC on AP. While our study focussed on AJC and its links with commitment and performance, future studies could consider how AJC affects other alliance-related constructs such as trust, relationship quality, and resource allocation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mayank Dhaundiyal

Mayank Dhaundiyal is an Associate Professor of Strategic Management, Innovation and Entrepreneurship at O P Jindal Global University, India. He holds a Ph.D. in Strategic Management and an M.Sc. in Marketing (First Class Honours) from Technological University Dublin, Ireland and a B.Tech. in Information Technology (First Class) from VIT University, India. Mayank’s research interest is in the areas of strategic alliances, resource based and dynamic capability view and firm level capability development.

Joseph Coughlan

Joseph Coughlan is the Professor of Marketing at Maynooth University, Ireland. His previous academic appointment was as Head of School at Dublin Institute of Technology and he has held visiting appointments at University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and at the Financial University of the Government of the Russian Federation in Moscow. He received his Ph.D. in Operational Research and Marketing from Warwick Business School, UK. Joseph’s core research area is in how organisations build and sustain mutually beneficial relationships and his work has been published in international peer reviewed journals.

References

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–17.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Arino, A. (2003). Measures of strategic alliance performance: An analysis of construct validity. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(1), 66–79. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400005

- Ariño, A., & Ring, P. S. (2010). The role of fairness in alliance formation. Strategic Management Journal, 31(10), 1054–1087. doi:10.1002/smj.v31:10

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. doi:10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x

- Barclay, L. J., & Kiefer, T. (2014). Approach or avoid? Exploring overall justice and the differential effects of positive and negative emotions. Journal of Management, 40(7), 1857–1898. doi:10.1177/0149206312441833

- Becker, H. S. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66(1), 32–40. doi:10.1086/222820

- Bello, D. C., Katsikeas, C. S., & Robson, M. J. (2010). Does accommodating a self-serving partner in an international marketing alliance pay off? Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 77–93. doi:10.1509/jmkg.74.6.77

- Bloemer, J., Pluymaekers, M., & Odekerken, A. (2013). Trust and affective commitment as energizing forces for export performance. International Business Review, 22(2), 363–380. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2012.05.002

- Carnovale, S., Henke, J. J., DuHadway, W., & Yeniyurt, S. (2019). Unintended consequences: How suppliers compensate for price concessions and the role of organizational justice in buyer‐supplier relations. Journal of Business Logistics. doi:10.1111/jbl.12205

- Christoffersen, J. (2013). A review of antecedents of international strategic alliance performance: Synthesized evidence and new directions for core constructs. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(1), 66–85. doi:10.1111/ijmr.2013.15.issue-1

- Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.386

- Cullen, J. B., Johnson, J. L., & Sakano, T. (1995). Japanese and local partner commitment to IJVs: Psychological consequences of outcomes and investments in the IJV relationship. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(1), 91–115. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490167

- Cullen, J. B., Johnson, J. L., & Sakano, T. (2000). Success through commitment and trust: The soft side of strategic alliance management. Journal of World Business, 35(3), 223. doi:10.1016/S1090-9516(00)00036-5

- Dong, X., Zou, S., Sun, G., & Zhang, Z. (2019). Conditional effects of justice on instability in international joint ventures. Journal of Business Research, 101, 171–182. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.027

- Folger, R., & Konovsky, M. A. (1989). Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 32(1), 115–130.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

- Ganesan, S., Brown, S. P., Mariadoss, B. J., & Ho, H. (2010). Buffering and amplifying effects of relationship commitment in business-to-business relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 47, 361–373. doi:10.1509/jmkr.47.2.361

- Glaister, K. W., & Buckley, P. J. (1998). Measures of performance in UK international alliances. Organization Studies, 19(1), 89–118. doi:10.1177/017084069801900105

- Gomes, E., Barnes, B. R., & Mahmood, T. (2016). A 22 year review of strategic alliance research in the leading management journals. International Business Review, 25, 15–27. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.03.005

- Gomes, E., Mellahi, K., Sahadev, S., & Harvey, A. (2017). Perceptions of justice and organisational commitment in International mergers and acquisitions. International Marketing Review, 34(5), 582–605.

- Greenberg, J. (1987). A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 9–22. doi:10.5465/amr.1987.4306437

- Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of Management, 16(2), 399. doi:10.1177/014920639001600208

- Gulati, R. (1995). Social structure and alliance formation patterns: A longitudinal analysis. Administrative science quarterly, 619–652.

- Gulati, R. (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 293–317. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0266

- Gulati, R., Wohlgezogen, F., & Zhelyazkov, P. (2012). The two facets of collaboration: Cooperation and coordination in strategic alliances. The Academy of Management Annals, 6(1), 531–583.

- Guthrie, J. P. (2001). High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: Evidence from New Zealand. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 180–190.

- Heimeriks, K. H. (2008). Developing alliance capabilities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Holm, D. B., Eriksson, K., & Johanson, J. (1999). Creating value through mutual commitment to business network relationships. Strategic Management Journal, 20(5), 467–486. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0266

- Holtz, B. C., & Harold, C. M. (2011). Interpersonal justice and deviance: The moderating effects of interpersonal justice values and justice orientation. Journal of Management. doi:10.1177/0149206310390049

- Inkpen, A. C. (2001). Strategic Alliances. In A. Rugman, M. & T. Brewer, L. (Eds.), Oxford handbook of international business (pp. 402–427). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, J. P., Korsgaard, M. A., & Sapienza, H. J. (2002). Perceived fairness, decision control, and commitment in international joint venture management teams. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1141–1160. doi:10.1002/smj.277

- Kale, P., & Singh, H. (2007). Building firm capabilities through learning: The role of the alliance learning process in alliance capability and firm-level alliance success. Strategic Management Journal, 28(10), 981–1000. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0266

- Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P., & Rugelsjoen, B. (2010). Managing alliances with the balanced scorecard. Harvard Business Review, 88(1), 114–120.

- Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. A. (1993). Procedural justice, attitudes, and subsidiary top management compliance with multinationals’ corporate strategic decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 502–526.

- Konovsky, M. A. (2000). Understanding procedural justice and its impact on business organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 489–511. doi:10.1177/014920630002600306

- Krishnan, R., Martin, X., & Noorderhaven, N. G. (2006). When does trust matter to alliance performance? Academy of Management Journal, 49(5), 894–917. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.22798171

- Kumar, N., Hibbard, J. D., & Stern, L. W. (1994). The nature and consequences of marketing channel intermediary commitment. Cambridge Massachusetts: Marketing Science Institute.

- Kumar, N., Stern, L. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1993). Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1633–1651.

- Leventhal, G. S. (1976). The distribution of rewards and resources in groups and organizations. In L. Berkowitz & W. Walster (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 91–131). New York: Academic Press.

- Lind, E., Allan, & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum.

- Liu, G., Aroean, L., & Ko, W. W. (2019). A business ecosystem perspective of supply chain justice practices. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 39, 1122–1143. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-09-2018-0578

- Liu, Y., Huang, Y., Luo, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2012). How does justice matter in achieving buyer–supplier relationship performance? Journal of Operations Management, 30(5), 355–367. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2012.03.003

- Lohtia, R., Bello, D. C., Yamada, T., & Gilliland, D. I. (2005). The role of commitment in foreign–Japanese relationships: Mediating performance for foreign sellers in Japan. Journal of Business Research, 58(8), 1009–1018. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2004.03.002

- Lunnan, R., & Haugland, S. A. (2008). Predicting and measuring alliance performance: A multidimensional analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 29(5), 545–556. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0266

- Luo, Y. (2005). How important are shared perceptions of procedural justice in cooperative alliances? Academy of Management Journal, 48(4), 695–709. doi:10.5465/amj.2005.17843946

- Luo, Y. (2007). The independent and interactive roles of procedural, distributive and interactional justice in strategic alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 644–664. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.25526452

- Luo, Y. (2008). Procedural fairness and interfirm cooperation in strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 29(1), 27–46. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0266

- Luo, Y. (2009). From gain-sharing to gain-generation: The quest for distributive justice in international joint ventures. Journal of International Management, 15(4), 343–356. doi:10.1016/j.intman.2008.12.006

- Luo, Y., Liu, Y., Yang, Q., Maksimov, V., & Hou, J. (2015). Improving performance and reducing cost in buyer–supplier relationships: The role of justice in curtailing opportunism. Journal of Business Research, 68(3), 607–615. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.08.011

- McFarlin, D. B., & Sweeney, P. D. (1992). Research notes. Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 35(3), 626–637.

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. doi:10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

- Nadkarni, S., & Herrmann, P. (2010). Ceo personality, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: The case of the indian business process outsourcing industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5), 1050–1073. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.54533196

- Nakos, G., & Brouthers, K. D. (2008). International alliance commitment and performance of small and medium-size enterprises: The mediating role of process control. Journal of International Management, 14(2), 124–137. doi:10.1016/j.intman.2007.11.001

- Narasimhan, R., Narayanan, S., & Srinivasan, R. (2013). An investigation of justice in supply chain relationships and their performance impact. Journal of Operations Management, 31(5), 236–247. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2013.05.001

- Nielsen, B. B. (2007). Determining international strategic alliance performance: A multidimensional approach. International Business Review, 16(3), 337–361. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2007.02.004

- O’Leary-Kelly, S. W., & Vokurka, R. J. (1998). The empirical assessment of construct validity. Journal of Operations Management, 16(4), 387–405. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00020-5

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Ren, H., Gray, B., & Kim, K. (2009). Performance of international joint ventures: What factors really make a difference and how? Journal of Management, 35(3), 805–832.

- Richard, P. J., Devinney, T. M., Yip, G. S., & Johnson, G. (2009). Measuring organizational performance: Towards methodological best practice. Journal of Management, 35(3), 718–804. doi:10.1177/0149206308330560

- Roch, S. G., & Shanock, L. R. (2006). Organizational justice in an exchange framework: Clarifying organizational justice distinctions. Journal of Management, 32(2), 299–322. doi:10.1177/0149206305280115

- Sarkar, M. B., Echambadi, R., Cavusgil, S. T., & Aulakh, P. S. (2001). The influence of complementarity, compatibility, and relationship capital on alliance performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29, 358–373. doi:10.1177/03079450094216

- Schreiner, M., Kale, P., & Corsten, D. (2009). What really is alliance management capability and how does it impact alliance outcomes and success? Strategic Management Journal, 30(13), 1395–1419. doi:10.1002/smj.v30:13

- Skarmeas, D., Katsikeas, C., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2002). Drivers of commitment and its impact on performance in cross-cultural buyer-seller relationships: The importer’s perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(4), 757–783. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8491043

- Sluyts, K., Matthyssens, P., Martens, R., & Streukens, S. (2011). Building capabilities to manage strategic alliances. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(6), 875–886. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.06.022

- Styles, C., Patterson, P. G., & Ahmed, F. (2008). A relational model of export performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5), 880–900. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400385

- Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

- Wang, A., & Dyball, M. C. (2019). Management controls and their links with fairness and performance in inter‐organisational relationships. Accounting & Finance, 59, 1835–1868. doi:10.1111/acfi.12408

- Wang, Q., Craighead, C. W., & Li, J. J. (2014). Justice served: Mitigating damaged trust stemming from supply chain disruptions. Journal of Operations Management, 32(6), 374–386. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2014.07.001

Appendix

Table A1. Organizational Justice Items

Table A2. Commitment Items

Table A3. AP Items