Abstract

While the use of the term fintech or financial technology has proliferated widely, theoretical work on the concept has lagged behind. This article attempts to capture the discussion on fintech, to provide a critique of the literature, and to propose future research opportunities. In order to do so, a list of peer-reviewed journals was compiled, identified, examined, coded, and classified into high-level themes to be reviewed, analysed, and interpreted. After synthesising the notion of fintech in the literature, this article proposes several potential areas for further exploration, divided into the following themes: definition, attributes, adoption, regulation, and competition. Fintech or financial technology is a relatively new subject in the literature but commonly cited as one of the most important innovations in the financial industry. It is expected that this article will help researchers and academics who are interested in studying the phenomenon more broadly.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

As one of the most commonly cited innovation in the last couple of years, financial technology or fintech has not been adequately discussed in peer-reviewed journals. This paper analyses the emergence of fintech by reviewing the literature, analysing the result, and interpreting the findings. Evidently, fintech is a broad, complex, and rich phenomenon, and can manifest in any number of different ways. For example, fintech can be interpreted differently in different contexts without any consensus. Innovation in relation to fintech is also quite complicated and very dynamic. The way it is spread, widely adopted, and reach its critical mass is also rather peculiar. More importantly, the regulation aspects of fintech are perhaps the most controversial one, especially for those who are operating outside its jurisdictional boundaries. These characteristics of fintech present not only challenges to incumbent banks and financial services but also opportunities for innovative and agile startups to disrupt and take over the market.

Competing of Interest

The author declared no conflicts of interest concerning the publication of this article.

1. Background and rationale

More than 70% of millennials would rather go to the dentist than hear what their banks have to say (Arslanian, Citation2016). This statement alone, even though quite debatable, raises an important question regarding the role of banking and financial industries in the era of industry 4.0 (Gabor & Brooks, Citation2017; Jakšič & Marinč, Citation2019). Indeed, the rise of fintech has inevitably led to changes in the role of technology, consumer behaviour, and ecosystems, as well as the industry and regulation itself (Gozman, Liebenau, & Mangan, Citation2018; Wonglimpiyarat, Citation2017).

A single remark in regard to such development brought down years of thinking that finance and technology were so close as to be sometimes quite difficult to separate (Gomber, Koch, & Siering, Citation2017). The financial services sector is at the forefront of technological innovation and widely recognised as the most extensive IT user among the service sectors (Iman, Citation2014). What we sometimes forget to appreciate are the marvels of complexity and interaction that go on between service provider, consumers, technology, and regulation. In many ways, this article is an attempt to put ourselves right on that point.

Unfortunately, this line of research has not been well attended (Ozili, Citation2018). While there are overwhelming volume of research publications in this domain (see, for example, Ashta & Biot‐Paquerot, Citation2018; Milian, Spinola, & de Carvalho, 2019; Sangwan, Prakash, & Singh, Citation2019), there are not many studies on fintech to be found in peer-reviewed journals. This can be verified by a simple search of the keyword “fintech” in Google Scholar. Most results can be found in working papers, consulting reports, and policy studies. This research aims to address that gap. Central to this aim are the following questions: What is fintech? What are the focal issues of fintech in the peer-reviewed journals?

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is threefold: First, this paper attempts to provide a comprehensive critical review of fintech in the literature, which has not been addressed to date. The second goal of this paper is to report the results of a study designed to examine potential areas for further development of fintech, which has typically not been the focus of previous research. The final, and perhaps most important, goal of this paper is to provide scholars in the field of technology management with a specific set of recommendations aimed at moving the discussion forward.

The outline of this article is as follows. First, it has in this section briefly described the notion of fintech and the relevance of this study. Section 2 elaborates the approach and methodology used to conduct this investigation. Section 3 concentrates on analysing fintech research in the current literature. It focuses on the taxonomies and frameworks, and critically reflects on them. Section 4 contemplates on the findings and proposes further insights. Lastly, Section 5 draws a conclusion and offers future research directions to extend our knowledge of fintech.

2. Approach and methodology

It is both timely and important that we synthesise the literature on fintech (Ozili, Citation2018). Since fintech is an emerging area, most of the literature available comes in the form of technical reports, consulting reports, working papers, conference papers, policy studies, and news websites. This study attempts to distinguish itself by focusing only on peer-reviewed journals since the major contributions are likely to be in the top journals (Webster & Watson, Citation2002). Papers from predatory journals and less credible publishers were excluded from this analysis. Editorials, commentaries, teaching cases, and book reviews were also excluded.

In reviewing the articles, this study followed Webster and Watson (2002)’s proposed approach. The review should match the goals of clarity, reliability, accuracy, and brevity so as to let the reader performs a systematic and competent analysis regarding the current state of the phenomena (Hart, Citation1999). The goal of the review was to provide an overall picture of the current and relevant research literature that touches on fintech initiatives. Such approach deemed to be rigour and has been adopted by many authors, for example, Gomber et al. (Citation2017) and Jung, Dorner, Weinhardt, and Pusmaz (Citation2018).

To perform this analysis of fintech, a list of reputable journals was compiled, in the fields of business and management, information systems, technology management, computer science, and law, among others. These journals were then individually searched using the Web of Science, for articles which contained the keywords “fintech” or “financial technology” anywhere within the title, abstract, or keywords. This restriction has been made because the term “fintech” or “financial technology” is becoming a buzz word (Milian, Spinola, & de Carvalho, Citation2019) and creating overlap and confusion among the terms. This analysis attempts to get back to the roots of its definition.

This study looked only at peer-reviewed journals written in English and neglected other sources, such as conference proceedings, reports, theses, and dissertations. This approach generated 218 articles in total, discussing “fintech” or “financial technology” theoretically or empirically. These articles were then scaled down for further manual examination to remove irrelevant and distant matches, and bring the number to a manageable size. When reviewing the literature, the researcher managed to identify a number of publications that met the inclusion criteria. The total number of articles that met this threshold was only 61, and these were then sorted by journal and year.

The author initially reads a subset of these articles to develop a list of categories that could be further coded. At the same time, two research assistants then independently coded each article based on these themes. The author reviews the result, resolves any discrepancies in coding, and revisits the codes until reach a consensus. The purpose of this approach is not merely to review the literature comprehensively, instead, to highlight themes and trends that are revealed as salient in empirical studies on fintech.

Content analysis was employed, particularly conceptual analysis to establish the existence and frequency of concepts in the data (Creswell, Citation2003). This involves quantifying the occurrence in the literature of a particular concept chosen for examination and further analysis, which can be both implicit and explicit in nature. This overall qualitative approach deemed to be suitable for this investigation and sufficiently sensitive to offer an understanding of the phenomena.

From there, each and every article was identified, examined, coded, and classified into some high-level themes (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). Key articles encountered during this examination, not already in the data set, were also reviewed. Some papers were excluded from coding due to data saturation having already been reached.Footnote1 With the themes coded and captured, an exercise was performed to consolidate the codes (Table ). These were then reviewed, analysed, and interpreted. Thus, the broad trends in the conceptualisation were identified, upon which analysis this paper is based.

Table 1. Coding themes

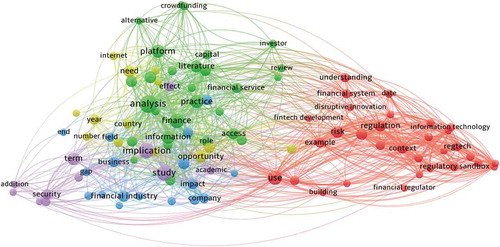

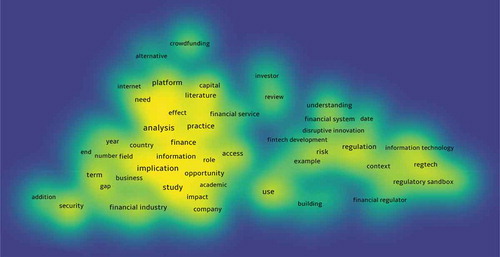

The network analysis was then performed by taking into account every keyword in the title and abstract fields and ignoring structured abstract labels and copyright statements. This study performed binary counting using VOSviewer, using the minimum number of occurrences of a term is 3. This counting resulted in 1563 terms, in which 135 of them meet the threshold. The numbers of terms to be selected in this network mapping are 100 (see Figure ).

As can be seen from Figure , most literature concerning fintech is focusing on the analysis, (business) practices, and the implication of such technologies in the market and society. These areas seem to be in constant growth from year to year while at the same time extending the reach to certain aspects of fintech such as platform, crowdfunding, security, as well as industries. On the right-hand side of the figure, there is also an active discussion regarding the regulatory aspect of fintech. Areas that become the focus are regulation, sandbox, the financial regulator, and regtech. Combining our review, network mapping, and heat map analysis help us to construct a map of the field in terms of density, frequency, and findings.

In the following section, this paper will provide what needs to be considered a tentative overview of this trend, organised around some of the most important issues and topics examined in the analysed publications. In the first step of analysis, this study examines the definition and importance of fintech in the literature. We find a very broad spectrum of definition and different set of theories that will be discussed below.

3. What is Fintech and why does it matter?

Analysing technological innovation, such as fintech, is quite challenging, if not impossible, through the lens of traditional or neoclassical economics that mainly focuses on product’s price or supply and demand. Technological artefacts and intellectual knowledge have peculiar attributes that distinguish them from other resources (Galende, Citation2006). Furthermore, financial intermediation has now shifted from conventional banks to “shadow” banks, those non-depository financial institutions that do not have to comply with traditional banking regulation (Buchak, Matvos, Piskorski, & Seru, Citation2018).

With the above backdrop, the emergence of fintech has thus given rise to “financial service disintermediation” as well as to the need for a new form of protection for consumers and investors (Giudici, Citation2018; Guo & Liang, Citation2016). Fintech start-ups are able to avoid the intermediation costs and minimum capital requirements usually associated with traditional banking services (Iman, Citation2018a). The use of big data analytics and data science has also changed how data are captured, processed, and analysed, which has in turn reduced search costs significantly (Giudici, Citation2018).

Joining these studies, Gomber et al. (Citation2017) define fintech as a neologism coming from “financial” and “technology” and referring to the connection between modern Internet technologies and established business activities of the banking sector. Meanwhile, Hung and Luo (Citation2016) identify five dimensions that can change the dynamics of the fintech market: players, added value, rules, tactics, and scope. In much of the literature, fintech is used in a purely functional way, providing variation in terms of the subject (Alt, Beck, & Smits, Citation2018; Gai, Qiu, & Sun, Citation2018; Lee & Shin, Citation2018).

For example, Puschmann (Citation2017) forcefully argues that fintech is “[…] incremental or disruptive innovations in or in the context of the financial services industry induced by IT developments resulting in new intra- or inter-organisational business models, products and services, organisations, processes and systems” (p74). Meanwhile, Gomber et al. (Citation2017) describe fintech as initiatives in the financial sector that are challenging established roles, business models, and service offerings by introducing technology-based innovations.

With a rather similar main theme, Ng and Kwok (Citation2017) classify fintech organisation into four different categories: efficient payment process, robo-advisors, peer-to-peer load and deposit platforms, and crowdfunding. Meanwhile, Lee and Shin (Citation2018) identify five different elements of fintech ecosystems: fintech start-ups, technology developers, the government, financial customers, and traditional financial institutions. Two markedly interesting views of fintech lie within the scope of this general definition and classification: first, technology plays an important roleFootnote2; and second, fintech encompasses existing government policies and regulations.Footnote3

While, traditionally, banks have always been the vanguard sector in the use of IT (Barras, Citation1990), this situation has forced banks and traditional financial institutions to increase their capabilities and expertise (Iman, Citation2019). Under these circumstances, fintech companies can choose to be disruptors or collaborators (Hung & Luo, Citation2016). A co-opetition strategy, where competition and cooperation exist at the same time (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, Citation1996), might be of interest for players in this niche and profitable market.

Yet, at the same time, government regulations could play a more pivotal role in the emergence of fintech start-ups. Their policies could significantly shape the way industry develops (Arner, Barberis, et al., Citation2017a). What needs to be stressed here is that, in introducing such regulation, we should proceed with caution. If governments requested all banks to engage in innovation, the results would probably not be as expected; however, if they encouraged fintech start-ups to enter the regulated market, there would be too many limitations and requirements that could perhaps not be fulfilled (Hung & Luo, Citation2016).

In some developed countries, the regulatory regime may favour fintech start-ups (see Arner, Barberis, & Buckley, Citation2016; Arner, Barberis, et al., Citation2017a; Arner, Zetzsche, et al., Citation2017b ; Stern, Makinen, & Qian, Citation2017; Zetzsche & Preiner, Citation2018). However, some other countries tend towards protectionism. For example, Taiwan’s government encourages traditional banks to invest in fintech companies for collaboration purposes, rather than giving incentives to fintech start-up entrepreneurs to develop new innovative products and services (Hung & Luo, Citation2016). Along the same lines, Iman (Citation2018b) presents the complexities of government regulation regarding fintech in Indonesia, and the overlaps between the central bank and the financial services authority.

This study finds that extant literatures tend to be descriptive and exploratory. Some studies propose more novel definition and approach toward fintech (e.g. Gomber et al., Citation2017; Wonglimpiyarat, Citation2017, Citation2018), while several others concentrate on interaction and the ecosystems (e.g. Kang, 2018; Lee & Shin, Citation2018; Leong et al., Citation2017; Thompson, Citation2017). Equivocality of fintech is also emerged in this analysis (David-West, Iheanachor, & Kelikume, Citation2018; De Kerviler, Demoulin, & Zidda, Citation2016; Kim, Park, & Choi, Citation2016; Kim, Park, Choi, & Yeon, Citation2015). It seems that fintech can enhance and facilitate opportunities, but also can have some detrimental effects.

From the analysis, it is evident that fintech is a broad, complex, and rich phenomenon, and can manifest in any number of different ways. Some focus on the innovation aspects of fintech, while others are on the new market and product development area. Some concentrate on regulation and compliance, while others are on technicalities and technological artefact (see Table ). With that said, it is important to note that this examination is not the only, or even the first, study of its kind in the academic domain.

Table 2. Examples of research on Fintech

4. How have previous scholars considered Fintech?

The review of the extant literature has provided us with useful insights into the dynamics of fintech that turns out to be very different than technology start-up firms. However, both the growing presence and the unexplained absence in some areas provide opportunities for further strengthening and possibly a re-shaping of the literature. We are currently perhaps in the limbo of purgatory and yet to come to grips with the idea of fintech. Thus, it is important that we classify fintech in a more robust way.

During the analysis, we read, coded, and classified fintech into different categories for further classification (see Table ). Based on its characteristics, we divided them into several classifications according to its relationship, subsectors, underlying technologies, service offering, key actors, contexts, as well as industries. While we tried our best to make every effort to be thorough in our categorisation, the possibility remains that this study might have missed some categories. However, any omissions hopefully would not significantly alter the conclusion.

Table 3. Fintech taxonomies

As this overview has shown, there have been quite a number of studies published in business and management journals that do take fintech seriously. These can be found clustered around a number of important subthemes, such as the rise and transformation of fintech, its peculiarities, consumer adoptions, regulations, and market competition.

4.1. Universal definition of Fintech

In order to be able to clearly define fintech, it is important to appreciate it and the historical roots of its origin. However, as the following review will show, studies of this kind, where the origins of fintech are considered as an extension of financial service provision (see Table ), have, almost invariably, been qualitative and have included very little or no historical research (Schueffel, Citation2016).

Table 4. The development of banking and Fintech

However, it appears that we do not have a unified definition of fintech just yet. Some of the literature is focusing on roles and structures (e.g. Arner, Barberis, et al., Citation2017a; Arner, Zetzsche, et al., Citation2017b; Lee & Shin, Citation2018), while other researchers are emphasising attributes and (product and service) provision (e.g. Iman, Citation2018b; Ng & Kwok, Citation2017). In addition, there are a number of more isolated studies that have demonstrated that most fintech companies have their origins in the IT industry instead of the traditional banking sector (Gomber et al., Citation2017). Similarly to Iman (Citation2018b), King (Citation2014) finds that fintech founders are often former bank employees. This is due to their capabilities in creating new solutions and tasks, work that was previously dominated by banks and financial institutions.

In his extensive review, Schueffel (Citation2016) maintains that the term “fintech” is standing on shaky ground and suffering from semantical problems. The term is already producing offspring (Alt et al., Citation2018; Gai et al., Citation2018; Lee & Shin, Citation2018), with derivatives such as regtech, insurtech (Stoeckli et al., Citation2018), and wealtech, without there ever having been an established common definition of fintech in the first place. Taking this a step further, Schueffel (Citation2016) posits that, due to its lack of definition, what an English speaker means by fintech could be very different to what a Frenchman or German means by it—let alone the rest of the world. Thus, it is especially important that we come up with a universal definition of fintech that can be adopted and turned into a business standard.

4.2. Fintech and its peculiarities

Fintech has grown rapidly in many different contexts, offering new innovative products and services using contemporary technologies (e.g. Alt et al., Citation2018; Gomber et al., Citation2017). However, the directions and magnitudes of the products and services delivered by fintech firms vary widely. Some studies have pursued this route by focusing on the adoption and diffusion of fintech products and services (consumer side), but to the best of our knowledge, there are very few studies focusing on what happens behind closed doors (producer side). This is seemingly at odds with what one might expect, since understanding what lies beneath such innovations would in no way destroy the magic; if anything, it would only deepen our appreciation and teach us about our technological development (Dranev, Frolova, & Ochirova, Citation2019).

With regard to managing innovation, Wonglimpiyarat (Citation2017) proposes a systemic approach to managing the tension between the complexity of innovation and the capabilities of the innovators to manage such innovation. Banks have traditionally been recognised as the most intensive users of IT (Barras, Citation1990) and perhaps the most innovative (Iman, Citation2014) in the service sector. However, the blossoming fintech penetration has opened up a new landscape of financial industry. It has also bridged the gap to enable cross-network payment and transfer services (Shim & Shin, Citation2016; Thompson, Citation2017). Thus, it is no wonder that the relationships between the fintech firms and the other actors and players in the industry are quite complicated.

Borrowing the Schumpeterian (1937) view of creative destruction, this phenomenon will unarguably raise a question: Should we promote the emergence of fintech start-ups to stimulate economic growth? Or should we deliberately limit the growth of incumbents since innovations do not usually come from them? Wonglimpiyarat (Citation2017) argues that fintech innovations require high systemic characteristics due to the network of ownerships and externalities that becomes an important factor during the diffusion stages. Yet, the peculiar characteristics of fintech firms are not all at the same level, and nor indeed are their innovative capabilities and resources.

4.3. Adoption pattern

Analysing fintech will lead to path dependencies in terms of ownership (banks vs. non-banks), of structure (fintech vs. techfin), of regulation (or rather a lack thereof), and of scope (from payments/simple products to more complex products). Most of the literature is focusing on either diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, Citation1983) or the technology acceptance model (Davis, Citation1989). A couple of papers, however, deserve a special mention here since they are using rather “unpopular” theories, such as regulatory focus theory (Higgins, Citation1998), in analysing fintech adoption.

In this particular market, fintech offers new products and services that satisfy customers’ needs not previously addressed by traditional financial service firms (Gomber et al., Citation2017; Pousttchi & Dehnert, Citation2018). Companies in the market are capable of developing innovations and creating novel opportunities, utilising state-of-the-art technologies and contemporary concepts. Thus, their products and services are usually relatively better-suited to and better-performing in today’s high-speed environment (Alt et al., Citation2018). These companies are agile and innovative enough that they are expected to take over the traditional banking sector, leaving banks with very limited services they can still offer to customers (Hemmadi, Citation2015).

Thus, another future direction this research points the way towards would be to examine the dynamics of existing consumers as well as the response of traditional incumbent firms. Fintech consumers will obviously form new digital habits, and change their values and loyalty (Pousttchi & Dehnert, Citation2018). On the other hand, since the time consumers spend on their decisions will increasingly be shortened, it is important that incumbent firms not only speed up their innovation but also utilise data-driven approaches to compete with new fintech firms (Lee & Shin, Citation2018). Such remarkable interdependencies between consumers, incumbent firms, and new fintech firms promise fruitful areas for further exploration.

4.4. Regulatory regimes

Departing from Hung and Luo (Citation2016)’s analysis, traditional banks that have been protected for too long will not offer a friendly environment for fintech start-ups. Here, they will face high barriers to entry, tough competition, and a market that already enjoys services from existing banks. Government intervention in this sector is less likely, since the government will not want to damage the foundations of these traditional financial institutions or stimulate systemic risk (Chen, Citation2016). This might suggest that a more systematic and consequential interaction between management scholars and (business) laws might be of benefit.

Admittedly, fintech is pivotal not only in increasing the accessibility and diversity of services but also in stimulating financial sector development (Gabor & Brooks, Citation2017; Haddad & Hornuf, Citation2018; Swartz, Citation2017). Thus, a better understanding of fintech and regulatory realms is mandatory for this and the democratisation of financial services. Indeed, the regulatory realms, as well as the institutional logics that prevail, represent a critical force shaping every economic actor involved in the fintech industry.

What we should not forget is that the intersection of functionalities, consumers, technological platforms, and emerging business models, defined by the rising fintech firms, has challenged the regulators in many different ways (Arner, Barberis, & Buckley, Citation2015; Arner et al., Citation2016). Regulation usually trails behind technological innovation and is often tardy in responding to new business models and practices (Gozman & Currie, Citation2014). Thus, it is necessary that we analyse the problems these new fintech firms will face in pushing further against so many jurisdictional boundaries at once.

4.5. Market and competition

Gomber et al. (Citation2017) sum things up nicely when they say that fintech refers to innovators and disruptors that offer more security, flexibility, opportunities, and efficiencies. Thus, the innovator can either be a new fintech start-up, a technology company, or an established service provider. The pursuit of a collaborative strategy may lead down some fruitful avenues (Wonglimpiyarat, Citation2017), but in some other countries, the market has become a zero-sum game (e.g. Hung & Luo, Citation2016). This suggests that future studies aiming towards further holistically cognisant theorising should be set up in ways that allow us to specifically examine this dynamic conditionality.

The emergence of fintech has also redefined the roles of conventional financial intermediaries (Gai et al., Citation2018; Haddad & Hornuf, Citation2018). For example, in the fintech lending market, the increasing lending volume will give rise to commission revenue, which could then lead to an underestimation of the credit risk of the counterparty (Giudici, Citation2018). This is where the insurance sector could hopefully take part. Unfortunately, most of the articles are focusing on the main players and have neglected those at the supporting and back-end level, such as security, insurance, IT infrastructure, and others.

In the context of developing countries that are not financial centres such as Hong Kong or Singapore, there will probably be no significant consequences in terms of direct job losses as a result of fintech innovation (Chen, Citation2016; Iman, Citation2018b; Tao, Dong, & Lin, Citation2017). However, this study speculates that there will be job shifts in related industries such as law firms, accounting firms, technology vendors, and others. While the number of them is perhaps substantially smaller, very different skill sets are required of today’s bankers and financiers than were required of those in the industry 10 years ago (Arslanian, Citation2016).

Having said all that, we are well aware that fintech is an engaging topic and has not yet been over-researched (Romānova & Kudinska, Citation2016). The main contribution of this paper is to outline promising areas for further research. It presents opportunities to be explored in the future (see Table ). This research also demonstrates a practical approach to managing fintech innovation and overseeing its current development. The analyses also offer practical implications on the innovation management of fintech, as well as insights for policy makers and governments.

Box 1. The rise and rise of Fintech in Indonesia

Table 5. Research issues in Fintech

5. Concluding remarks

This paper is concerned with the novelty of fintech that has not been well addressed in peer-reviewed journals. It shows the extent to which fintech is being discussed in the academic literature. The research findings suggest insightful implications such as that we are still trying to come up with a universal definition of fintech. Its attributes and characteristics, especially its interaction within the ecosystems, along with market competitions, are interesting and worth of further scrutiny. Its adoption pattern, especially in developing countries and in combating financial inclusion, is of importance. Moreover, regulatory regimes in different contexts represent a promising area that could contribute to the literature.

While there are increasing debate in the literatures of fintech, it is obvious that we must still analyse, observe, and explore the literature from multiple perspectives. Based on the review, the extant literature are fragmented and tend to be disconnected to the literatures on management or strategy. By integrating those aforementioned different themes, with an objective mindset, we will be able to build, in a steady fashion, a system of fintech services and governance which is more comprehensive and multidisciplinary. Moreover, national cultural factors in different contexts seem to be quite influential and idiosyncratic—that will complement the analysis of fintech ecosystems thoroughly.

Deep criticisms remain. One of the most troublesome is that this review focused only on the keywords of “fintech” and/or “financial technology”, while in reality there are several equally important keywords that could have been looked for, such as “blockchain”, “cryptocurrency”, “crowdfunding”, “big data analytics”, and “near field communication”, among others. This method turned out to be rather inclusive by ignoring those related keywords. Another criticism is that, due to its fast-growing development, by the time this article is published, its relevance and timeliness might have lessened. Thus, this paper should be considered as the first step in our research area and to serve as a stepping stone to move the literature forward.

All in all, this article has brought into view a quite extensive research base in business and management that employs fintech in a variety of ways. It has also identified a growing number of studies that display what we call “fintech transformation”, by considering its peculiarities, attributes, dynamic complexities, and contingencies. Heeding the above suggestions will, the researcher believe, strengthen, and expand both of these and, ultimately, transform fintech from what appears to be an outsider status into an integral part of (empirical) research and theorising in business and management studies. While the author understands that many holes can be found in this review and proposition, it hopefully makes for interesting fodder nevertheless.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank participants of the 2019 British Academy of Management meeting in Birmingham for their valuable feedback. This research was supported by the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia through 2019 Post-doctoral Program.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nofie Iman

Nofie Iman is currently working at the Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada. His research interests are in the area of management of innovation and technology strategy. He has published several papers on fintech, mobile payment, financial services, as well as other technological innovation, particularly in service sector.

Notes

1. We define saturation as informational redundancy (see Sandelowski, Citation2008). We begin to gather the same ideas, arguments, and/or propositions again and again, and thus, it is then time to stop collecting literatures and begin analysing what has been collected (Grady, Citation1998).

2. Most literature argue that fintech is technological-driven innovation rather than market-driven or consumer-driven innovation.

3. Fintech are operating in many different industry/sectors, which make them difficult to regulate. An example is the intersection between incumbent banks that are moving into technology vs. start-up companies that are beginning to offer bank-like products such as personal loans, term credit, mutual funds, among others (Iman, Citation2019).

References

- Adhami, S., Giudici, G., & Martinazzi, S. (2018, November –December). Why do businesses go crypto? An empirical analysis of initial coin offerings. Journal of Economics and Business, 100, 64–17. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2018.04.001

- Alt, R., Beck, R., & Smits, M. T. (2018). FinTech and the transformation of the financial industry. Electronic Markets, 28(3), 235–243. doi:10.1007/s12525-018-0310-9

- Anagnostopoulos, I. (2018). Fintech and regtech: Impact on regulators and banks. Journal of Economics and Business, 100, 7–25. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2018.07.003

- Arner, D. W., Barberis, J. N., & Buckley, R. P. (2015). The evolution of Fintech: A new post-crisis paradigm. Georgetown Journal International Law, 47, 1271–1319.

- Arner, D. W., Barberis, J. N., & Buckley, R. P. (2016). The emergence of regtech 2.0: From know your customer to know your data. Journal of Financial Transformation, 22, 79–86.

- Arner, D. W., Barberis, J. N., & Buckley, R. P. (2017a). FinTech, RegTech, and the reconceptualization of financial regulation. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, 37(3), 371–413.

- Arner, D. W, Zetzsche, D. A, Buckley, R. P, & Barberis, J. N. (2017b). Fall 3). Fintech and Regtech: Enabling Innovation while Preserving Financial Stability. Georgetown Journal Of International Affairs, 18, 47–58. doi: 10.1353/gia.2017.0036

- Arslanian, H. (2016) How FinTech is shaping the future of banking. TEDx Talks. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/pPkNtN8G7q8.

- Ashta, A. (2018). News and trends in Fintech and digital microfinance: Why are European MFIs invisible? FIIB Business Review (FBR), 7(4), 1–12.

- Ashta, A., & Biot‐Paquerot, G. (2018). Fintech evolution: Strategic value management issues in a fast changing industry. Strategic Change, 27(4), 301–311. doi:10.1002/jsc.2203

- Barras, R. (1990). Interactive innovation in financial and business services: The vanguard of the service revolution. Research Policy, 19(3), 215–237. doi:10.1016/0048-7333(90)90037-7

- Begenau, J., Farboodi, M., & Veldkamp, L. (2018). Big data in finance and the growth of large firms. Journal of Monetary Economics, 97, 71–87. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2018.05.013

- Brammertz, W., & Mendelowitz, A. I. (2018). From digital currencies to digital finance: The case for a smart financial contract standard. The Journal of Risk Finance, 19(1), 76–92. doi:10.1108/JRF-02-2017-0025

- Brandenburger, A. M., & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-opetition. New York: Doubleday.

- Brody, M., Lev, O., Taft, J. P., Wilkes, G., Bisanz, M., Shinohara, T., & Tsai, J. (2017). Three financial regulators issue reports on product and service innovations. Journal of Investment Compliance, 18(1), 84–91. doi:10.1108/JOIC-02-2017-0005

- Buchak, G., Matvos, G., Piskorski, T., & Seru, A. (2018). Fintech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks. Journal of Financial Economics, 130(3), 453–483. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.03.011

- Chen, L. (2016). From fintech to finlife: The case of fintech development in China. China Economic Journal, 9(3), 225–239. doi:10.1080/17538963.2016.1215057

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- David-West, O., Iheanachor, N., & Kelikume, I. (2018). A resource-based view of digital financial services (DFS): An exploratory study of Nigerian providers. Journal of Business Research, 88, 513–526. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.034

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. doi:10.2307/249008

- De Kerviler, G., Demoulin, N. T., & Zidda, P. (2016). Adoption of in-store mobile payment: Are perceived risk and convenience the only drivers? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 334–344. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.04.011

- Dranev, Y., Frolova, K., & Ochirova, E. (2019). The impact of fintech M&A on stock returns. Research in International Business and Finance, 48, 353–364. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.01.012

- Drasch, B. J., Schweizer, A., & Urbach, N. (2018). Integrating the ‘Troublemakers’: A taxonomy for cooperation between banks and fintechs. Journal of Economics and Business, 100, 26–42. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2018.04.002

- Ferretti, F. (2018). Consumer access to capital in the age of FinTech and big data: The limits of EU law. Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 25(4), 476–499. doi:10.1177/1023263X18794407

- Gabor, D., & Brooks, S. (2017). The digital revolution in financial inclusion: International development in the fintech era. New Political Economy, 22(4), 423–436. doi:10.1080/13563467.2017.1259298

- Gai, K., Qiu, M., & Sun, X. (2018). A survey on FinTech. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 103(1), 262–273. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2017.10.011

- Galende, J. (2006). Analysis of technological innovation from business economics and management. Technovation, 26(3), 300–311. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2005.04.006

- Gimpel, H., Rau, D., & Röglinger, M. (2018). Understanding FinTech start-ups – A taxonomy of consumer-oriented service offerings. Electronic Markets, 28(3), 245–264. doi:10.1007/s12525-017-0275-0

- Giudici, P. (2018). Financial data science. Statistics & Probability Letters, 136, 160–164. doi:10.1016/j.spl.2018.02.024

- Gomber, P., Koch, J. A., & Siering, M. (2017). Digital Finance and FinTech: Current research and future research directions. Journal of Business Economics, 87(5), 537–580. doi:10.1007/s11573-017-0852-x

- Gozman, D., & Currie, W. (2014). The role of investment management systems in regulatory compliance: A post-financial crisis study of displacement mechanisms. Journal of Information Technology, 29(1), 44–58. doi:10.1057/jit.2013.16

- Gozman, D., Liebenau, J., & Mangan, J. (2018). The innovation mechanisms of fintech start-ups: Insights from SWIFT’s innotribe competition. Journal of Management Information Systems, 35(1), 145–179. doi:10.1080/07421222.2018.1440768

- Grady, M. P. (1998). Qualitative and action research: A practitioner handbook. Bloomington: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

- Guo, Y., & Liang, C. (2016). Blockchain application and outlook in the banking industry. Financial Innovation, 2(1), 24. doi:10.1186/s40854-016-0034-9

- Haddad, C., & Hornuf, L. (2018). The emergence of the global fintech market: Economic and technological determinants. Small Business Economics, 53(1),81–105.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9991-x.

- Hart, C. (1999). Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science imagination. London: Sage Publications.

- Hemmadi, M. (2015). FinTech is both friend and FOE. Canadian Business, 88(6), 10–11.

- Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 1–46. Academic Press

- Huang, R. H. (2018). Online P2P lending and regulatory responses in China: Opportunities and challenges. European Business Organization Law Review, 19(1), 63–92. doi:10.1007/s40804-018-0100-z

- Hung, J. L., & Luo, B. (2016). FinTech in Taiwan: A case study of a Bank’s strategic planning for an investment in a FinTech company. Financial Innovation, 2(1), 15. doi:10.1186/s40854-016-0037-6

- Iman, N. (2014). Innovation in financial services: a tale from e-banking development in indonesia. International Journal Of Business Innovation and Research, 8(5), 498–522. doi: 10.1504/IJBIR.2014.064611

- Iman, N. (2018a). Assessing the dynamics of fintech in Indonesia. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 15(4), 296–303. doi:10.21511/imfi.15(4).2018.24

- Iman, N. (2018b). Is mobile payment still relevant in the fintech era? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 30, 72–82. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2018.05.009

- Iman, N. (2019). Traditional banks against fintech startups: A field investigation of a regional bank in Indonesia. Banks and Bank Systems, 14(3), 20–33. doi:10.21511/bbs.14(3).2019.03

- Jagtiani, J., & Lemieux, C. (2018). Do fintech lenders penetrate areas that are underserved by traditional banks? Journal of Economics and Business, 100, 43–54. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2018.03.001

- Jakšič, M., & Marinč, M. (2019). Relationship banking and information technology: The role of artificial intelligence and FinTech. Risk Management, 21(1), 1–18. doi:10.1057/s41283-018-0039-y

- Jun, J., & Yeo, E. (2016). Entry of FinTech firms and competition in the retail payments market. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 45, 159–184. doi:10.1111/ajfs.2016.45.issue-2

- Jung, D., Dorner, V., Weinhardt, C., & Pusmaz, H. (2018). Designing a robo-advisor for risk-averse, low-budget consumers. Electronic Markets, 28(3), 367–380. doi:10.1007/s12525-017-0279-9

- Kang, J. (2018). Mobile payment in Fintech environment: Trends, security challenges, and services. Human-centric Computing and Information Sciences, 8(1), 1–32. doi:10.1186/s13673-018-0155-4

- Kim, Y., Park, Y. J., & Choi, J. (2016). The adoption of mobile payment services for “Fintech”. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 11(2), 1058–1061.

- Kim, Y., Park, Y. J., Choi, J., & Yeon, J. (2015). An empirical study on the adoption of “Fintech” service: Focused on mobile payment services. Advanced Science and Technology Letters, 114(26), 136–140.

- King, A. (2014) Fintech: Throwing down the gauntlet to financial services. http://www.unquote.com/unquote/analysis/74596/fintech-throwing-down-the-gauntlet-to-financial-services.

- Langley, P., & Leyshon, A. (2017). Capitalizing on the crowd: The monetary and financial ecologies of crowdfunding. Environment and Planning A, 49(5), 1019–1039. doi:10.1177/0308518X16687556

- Larios-Hernández, G. J. (2017). Blockchain entrepreneurship opportunity in the practices of the unbanked. Business Horizons, 60(6), 865–874. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2017.07.012

- Lee, L., & Shin, Y. J. (2018). Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons, 61(1), 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2017.09.003

- Leong, C., Tan, B., Xiao, X., Tan, F. T. C., & Sun, Y. (2017). Nurturing a FinTech ecosystem: The case of a youth microloan startup in China. International Journal of Information Management, 37(2), 92–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.11.006

- Li, G., Dai, J. S., Park, E.-M., & Park, S.-T. (2017). A study on the service and trend of Fintech security based on text-mining: Focused on the data of Korean online news. Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques, 13(4), 249–255. doi:10.1007/s11416-016-0288-9

- Li, Y., Spigt, R., & Swinkels, L. (2017). The impact of FinTech start-ups on incumbent retail banks’ share prices. Financial Innovation, 3, 1–26. doi:10.1186/s40854-017-0076-7

- Martínez-Climent, C., Zorio-Grima, A., & Ribeiro-Soriano, D. (2018). Financial return crowdfunding: Literature review and bibliometric analysis. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(3), 527–553. doi:10.1007/s11365-018-0511-x

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage publication.

- Milian, E. Z., Spinola, M. M., & de Carvalho, M. M. (2019). Fintechs: A literature review and research agenda. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 34, 100833. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2019.100833

- Nakashima, T. (2018). Creating credit by making use of mobility with FinTech and IoT. IATSS Research, 42(2), 61–66. doi:10.1016/j.iatssr.2018.06.001

- Ng, A. W., & Kwok, B. K. B. (2017). Emergence of Fintech and cybersecurity in a global financial centre: Strategic approach by a regulator. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 25(4), 422–434. doi:10.1108/JFRC-01-2017-0013

- Nooren, P, van Gorp, N, van Eijk, N, & Fathaigh, R.Ó. (2018). Should we regulate digital platforms? a new framework for evaluating policy options. Policy & Internet, 10, 264–301. doi.10.1002/poi3.177

- Ozili, P. K. (2018). Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanbul Review, 18(4), 329–340. doi:10.1016/j.bir.2017.12.003

- Pousttchi, P., & Dehnert, M. (2018). Exploring the digitalization impact on consumer decision-making in retail banking. Electronic Markets, 28(3), 265–286. doi:10.1007/s12525-017-0283-0

- Puschmann, T. (2017). Fintech. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 59(1), 69–76. doi:10.1007/s12599-017-0464-6

- Qiu, M., Gai, K., Zhao, H., & Liu, M. (2018). Privacy‐preserving smart data storage for financial industry in cloud computing. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience, 30, 1–10. doi:10.1002/cpe.v30.5

- Rogers, E. M. (1983). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

- Romānova, I., & Kudinska, M. (2016). Banking and Fintech: A challenge or opportunity? In S. Grima, F. Bezzina, I. Romānova, & R. Rupeika-Apoga (Eds.), Contemporary issues in finance: Current challenges from across Europe (Contemporary studies in economic and financial analysis) 98, 21–35. West Yorkshire, England: Emerald Publishing Ltd.

- Ryu, H.-S. (2018). What makes users willing or hesitant to use Fintech? The moderating effect of user type. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 118(3), 541–569. doi:10.1108/IMDS-07-2017-0325

- Sandelowski, M. (2008). Theoretical saturation. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 875–876). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Sangwan, V., Prakash, P., & Singh, S. (2019). Financial technology: A review of extant literature. Studies in Economics and Finance, Forthcoming. doi.10.1108/SEF-07-2019-0270

- Schueffel, P. (2016). Taming the beast: A scientific definition of fintech. Journal of Innovation Management, 4(4), 32–54. doi:10.24840/2183-0606_004.004_0004

- Shim, Y., & Shin, D.-H. (2016). Analyzing China’s Fintech industry from the perspective of actor-network theory. Telecommunications Policy, 40, 168–181. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2015.11.005

- Stern, C., Makinen, M., & Qian, Z. (2017). FinTechs in China–With a special focus on peer to peer lending. Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies, 10(3), 215–228. doi:10.1108/JCEFTS-06-2017-0015

- Stewart, H., & Jürjens, J. (2018). Data security and consumer trust in FinTech innovation in Germany. Information & Computer Security, 26(1), 109–128. doi:10.1108/ICS-06-2017-0039

- Stoeckli, E., Dremel, C., & Uebernickel, F. (2018). Exploring characteristics and transformational capabilities of InsurTech innovations to understand insurance value creation in a digital world. Electronic Markets, 28(3), 287–305. doi:10.1007/s12525-018-0304-7

- Swartz, K. L. (2017). Stored value facilities: Changing the fintech landscape in Hong Kong. Journal of Investment Compliance, 18(1), 107–110. doi:10.1108/JOIC-02-2017-0010

- Tao, Q., Dong, Y., & Lin, Z. (2017). Who can get money? Evidence from the Chinese peer-to-peer lending platform. Information Systems Frontiers, 19(3), 425–441. doi:10.1007/s10796-017-9751-5

- Thompson, B. S. (2017). Can financial technology innovate benefit distribution in payments for ecosystem services and REDD+? Ecological Economics, 139, 150–157. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.04.008

- Todorof, M. (2018). Shariah-compliant FinTech in the banking industry. ERA Forum, 19(1), 1–17. doi:10.1007/s12027-018-0505-8

- Töpfer, L.-M. (2018). Inside global financial networks: The state, lead firms, and the rise of fintech. Dialogues in Human Geography, 8(3), 294–299. doi:10.1177/2043820618797779

- Tsai, C.-H., & Peng, K.-J. (2017). The fintech revolution and financial regulation: The case of online supply-chain financing. Asian Journal of Law and Society, 4, 109–132. doi:10.1017/als.2016.65

- Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, 26(2)(June, 2002), xiii–xxiii. www.jstor.org/stable/4132319.

- Wonglimpiyarat, J. (2017). FinTech banking industry: A systemic approach. Foresight, 19(6), 590–603. doi:10.1108/FS-07-2017-0026

- Wonglimpiyarat, J. (2018). Challenges and dynamics of FinTech crowd funding: An innovation system approach. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 29, 98–108. doi:10.1016/j.hitech.2018.04.009

- Yoon, K.-S., & Jun, J. (2019). Liability and antifraud investment in fintech retail payment services. Contemporary Economic Policy, 37(1), 181–194. doi:10.1111/coep.2019.37.issue-1

- Zavolokina, L., Dolata, M., & Schwabe, G. (2016). The FinTech phenomenon: Antecedents of financial innovation perceived by the popular press. Financial Innovation, 2, 1–16. doi:10.1186/s40854-016-0036-7

- Zetzsche, D. A., Buckley, R. P., Barberis, J. N., & Arner, D. W. (2017). Regulating a revolution: From regulatory sandboxes to smart regulation. Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law, 23(1), 31–103.

- Zetzsche, D. A., & Preiner, C. (2018). Cross-border crowdfunding: Towards a single crowdlending and crowdinvesting market for Europe. European Business Organization Law Review, 19(2), 217–251. doi:10.1007/s40804-018-0110-x