?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The world’s oldest travel company Thomas Cook, the British tour operator with 19 million yearly clients, after 178 years of service, has officially announced that it would be liquidating its assets and filed for bankruptcy, despite attempts to rescue the brand. The low-cost travel firms and their cut-throat prices have certainly been a boon to customers, but legacy travel companies, who have been forced to decrease their prices, still not align themselves, especially if they have too diversified their activities and lost the scale advantage. In the field of today’s travel business, it is not possible only to rely on case studies and best practices. But it is necessary to come up with new approaches that can deal with changes in conditions such as when confronting the tourism business risk diversification and economies of scale. This article aims to create a general identification of the tourism business management system in terms of stable (and thus, sustainable) accommodation (and accompanying services) diversification, depending on the changes in the critical quantity of economies of scale. An analytical mathematical model is used for determining the diversification and economies of scale, and the parameters are determined using a full factorial design. The results of the study verify the functionality, reliability and consistency of the designed solution using a selected enterprise case study. From a practical point of view, the solution represents re-settings of diversification of accommodation offers in terms of changing the value of the critical scale of economies and other contextual factors for business.

Public Interest Statement

Currently, modern portfolio theory (MPT), or mean-variance analysis, is used to plan a product or service portfolio. It is a mathematical framework for assembling a portfolio of assets such that the expected return is maximized for a given level of risk. In this paper, we have followed this basic concept and created a relatively universal model that does not optimize the profit at the given risk but optimizes both variables at the same time - looking for the total optimum. Consequently, we first expressed the risk as a function of diversification and incorporated it into the function of seeking maximum profit in terms of the offered portfolio of products. Using differential calculus, we have found a generally valid solution that considers both the economies of scale and lower risk at higher diversification. Then we applied this solution to the area of tourism services.

1. Introduction

Several studies have shown that diversification has implied and different effects on firm profit (Shah, Citation2019; Alcántara-Pilar, Citation2018; Stimpert & Duhaime, Citation2007). Similarly, multiple authors argue that a negative relationship exists without considering other variables. However, others further expect that the link will include both primary and secondary effects (Louida, 2018; Lueckenbach et al., Citation2019; Reichenecker, Citation2019). This explanation was first mentioned by Rumelt (Citation1992), who described factor-based economies of scope and uncertain imitability in a pioneer study elucidating diversified profitability theory. Likewise, Bettis (Citation2002) found that excellent business performance in related products diversification is correlated with the improvement and utilisation of key managerial skills. The arguments of Park and Seyoung (Citation2019), Bettis (Citation2002) and Lippman and Rumelt (Citation1992) run parallel to those constructed by resource-based ideologists. Some resource-based authors moved the analysis of relatedness from the product to the resource grade (Anand & Singh, Citation2007; Bielstein, Citation2019; Toth, Citation2019; Su et al., Citation2019). For example, Chatterjee and Wernerfelt (Citation2001) found that independent diversifications of accommodation offers primarily rely on financial resources, exhibiting a lower performance than related diversifications utilizing material, information and human resources (HR) firms’ resources do. Almost identical results, supporting a positive association between diversification at the proprietary resource-level and performance, were found in several studies (Anand & Singh, Citation2007; Hung, 2019; Markides & Williamson, Citation2004; Montgomery & Wernerfelt, Citation1998).

In terms of offering tours or diversifying accommodation, this issue has been explored by various authors for many years. Some authors draw attention to the cultural preferences that affect the diversity of accommodation (Ramires, Citation2018); other authors see an effect for customers in the form of greater satisfaction in the diversification of accommodation (Tahir & Meltem, Citation2018). Some researchers consider the diversity of accommodation as part of the uniqueness of the destination (e.g. Thi Lan, 2018). Others see the positive trend of an increasing supply of accommodation accompanying them in the application of new technologies in tourism destination marketing (e.g. Andersson et al. Citation2017). also introduced the idea of a multiphase diversified portfolio during a tour, where sequentially, the diversified offer is available from the pre-trip phase to the predisposition at the destination phase. The phenomenon of diversification of accommodation and services has also been investigated from a historical perspective (Arie, Citation2018). The results clearly identify three clusters, as follows “conventional cultural tourists”, “spontaneous cultural tourists” and “absorptive cultural tourists”. It also recognises that the destination attributes that most influence satisfaction are specific elements of tourism supply, such as gastronomy, accommodation, culture and entertainment and hospitality. Most “agents” in the tourism sector (e.g. hotels, travel agencies and restaurants) communicate directly with consumers from different parts of the world, and thus, from different cultures. This presents an additional challenge to communications when the cultural context of service providers differs from that of the consumers with whom they are interacting (Dolores et al., Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2019).

The previous research exhibits two basic approaches. Based on data analysis, products are diversified either positively or negatively. Furthermore, there are two directions from the perspective of the use of the methodological apparatus (generalised diversification effects based on case studies or an optimised diversification process based on the methodological apparatus). In the optimised diversification group, linear programming (Park & Seyoung, Citation2019), fuzzy logic, multi-criteria evaluation (Arrais-Castro, Citation2018) or statistical analysis (Ma, Citation2017a) is employed. All these approaches are relatively sensitive to the field of collection or the industrial segment, and it is possible to exclude the third factor (statistical evaluation) or the subjectivity of experts (fuzzy logic and multi-criteria approaches).

In contrast to the instability of the validity of the detected sessions, using the above methods, the analytical solution is based on functional relationships that usually automatically satisfy the causality between dependent and independent variables. Thus, in this article, an analytical solution is designed, representing a time-constant and stable scheme with a relatively broad field of application. In addition, the solution is derived with a detailed description of the steps for its subsequent development to industries other than tourism business management.

2. Research questions

Beyond the statistical estimation of the regression model (for example, Assaf & Tsionas, Citation2019; Hasan et al., Citation2017 or Li et al., Citation2019 have a critical attitude to its use in the travel business), it is possible to find a general (or semi-general) explicit form of dependence of product portfolio diversification on microeconomic variables and business risk (e.g. described by the distribution of random variables). This analytical form of product portfolio diversification can be practically used to optimise the product portfolio, regardless of the selected economic control variables (e.g. to maximise the total profit during the reporting period).

3. Materials and methods

The solution design is based on finding an analytical solution for optimising diversity (diversification) of accommodation and accompanying services in relation to reducing business risk r, which negatively affects the profit margin by reducing the benefits of scale production. Thus, diversification acts in two ways: It positively affects the entrepreneur’s risk of loss by dividing production capacity into revenue substitutes, while at the same time, it decreases partial profit margins. The average profit margin is usually defined as the difference between the average price of one portfolio product pand the average total cost of product tc/q (where qis the average quantity of production of one portfolio type of product diversification and tc is the total cost).

In the absence of business risk of failure r= 0 (generally r∈〈0.1〉), it is possible to optimise the profit margin p—tc/q through the following equation:

If we estimate the risk of business r(e.g. from the distribution of random variables using aprobability density or distribution function or the ratio of unsuccessful business plans to the total number of plans in the reporting period), we will adjust equation Equation(1)(1)

(1) to optimise it according to two different criteria:

The risk of entrepreneurship, which decreases when the production capacity is distributed into yield substitutes, can be used in terms of the relationship for parallel business activities in the following way:

When determining the average risk r̅ (e.g. given as aweighted average risk of the whole activity portfolio), we can approximate EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) in the following form:

where xis the number of products of diversified offers of accommodation in each destination. For this variable, it is advisable to introduce the diversification, which is defined by the following relation:

where is the total number of clients served over aperiod (1year in the present case) multiplied by the average number of overnight stays per client.

By substituting (4) into (2), we obtain an implicit (exponential) expression of the number of products of adiversified production portfolio (portfolio of accommodation offers within the given destination x) in relation to the risk of rand the total average cost of the accommodation offers tc (tc = fc/q + vc), where vc is the average variable portfolio cost (sometimes replaced by direct costs per piece of accommodation offers). Thus,

Since (6) is afunction of multiple variables, to find the optimum number of x(offers of accommodation at agiven destination) depending on the risk and benefits of the range, we perform apartial derivative of EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) by x, which is equal to zero. Thus,

It is still necessary to express the average fixed cost fc/q in the production portfolio xfor avoiding optimising the yield component of the equation; that is, the cost component is not in the form of aderivative constant. The average variable costs probably do not have an explicit effect on economies of scale (mild effect of reducing labour intensity with increasing qis annulled by increasing machine wear, etc.). Therefore, it is advisable to let the average variable costs be represented by xas aderivation constant. Thus,

where are the average fixed costs of one product type from the total product portfolio. Substituting EquationEquation (9)(9)

(9) into (8) yields the equation form that is adapted for derivation according to x:

After partial derivation of relation (9), according to the searched diversified portfolio variable of production x, we obtain

By separating the variable xon the left side of the equation, we obtain an explicit expression of the accommodation offers in the given destination variable. Thus,

where the domain variables are

EquationEquation (11)(11)

(11) can be adjusted to the needs of the management of the travel agency so that the dependent variables are the total microeconomic variables for which information is readily available (e.g. from management accounting records). We can then calculate the total variable costs (direct costs as average variable costs; VC [EUR]), total fixed costs (total investment costs for the period of 1year; FC [EUR]), total annual profit (before interest; TP [EUR]). We can find these values by multiplying the average values for revenues and variable costs by the number of paid nights of diversified accommodation at the destination during the reference period q.Thus,

Substituting total variables from relationship (12) to relationship (11), we obtain anew (modified) relationship for determining the dependency of the portfolio of accommodation offers at the destination based on the total microeconomic variables available from management accounting:

For example, for total fixed costs (annual investment excluding variable costs), FC = 5 × 106 EUR, estimated annual profit TP = 5.9 × 106 EUR and number of nights spent in travel agency tours (average number of guests perday times days peryear) q= 250 × 365 = 9.1250 × 104, the average price of accommodation p= 100 EUR and the average variable (direct) costs c= 35 EUR combines the business risk and profit of the corresponding portfolio of accommodation at the destination:

It is advisable to operate with quantities that can be regulated via manager settings to plan the future business portfolio. The tourism manager usually sets the amount of investment in FC business (e.g. travel agency) and profit margin (average cost of one night’s travel and average variable cost: p-vc). For this purpose, it is appropriate (using the microeconomic theory of income and cost) to modify formula (12) to form adependency on the travel agency’s supply diversification depending on the FC’s annual investment and investment and profit coverage (p-vc). Thus, we first express the total (annual) profit of the travel agency TP as the difference between the total revenue TR and total cost TC (TC = VC + FC):

Subsequently, the expression of the total profit TP represented by formula (15) is substituted by formula (12). This operation gives us the form of an explicit dependence of the package (holiday) portfolio xfor the given destination on the average annual FC investment and package price per customer and one accommodationday p:

By gradually adjusting formula (16), we obtain formula (17), which is used to set the portfolio of package (accommodation) xfor agiven destination depending on the FC investment and average price of one-day package (or accommodation) p:

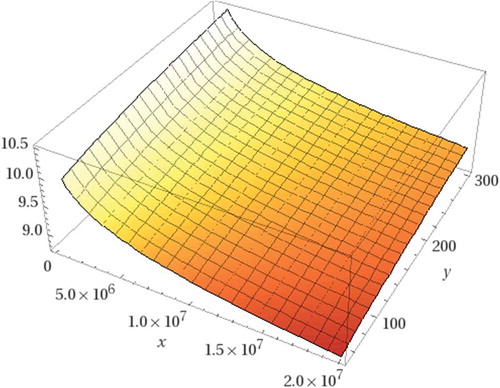

Relationship (17) shows that the dependency of the diversification of the package of travel packages in destination xon business risk rcan be estimated as the average annual occupancy of the hotel, r= 0.9. The diversification of accommodation offers dependson two variables when calculating the direct (variable) cost of accommodation per guest vc. Formula (17) is then used for determining the extent of the offer of residential tours; it also considers business risk (implicitly expressed by r). This dependence is expressed by the diversification of the trip offer xon two variables of the FC investment, and the price of the one-night trip pis shown in Figure .

Figure 1. Dependence of diversification of production on fixed costs (x) and total revenue (y) at risk r= 0.1.

We transform the coordinate system x, y, zto view agraphical optimisation of the xtravel agency offers variables, such that

The dependency xof the diversified portfolio of tours and accommodation is expressed as afunction of two variables x = f (FC, p). Other variables use values from the case study formalised by (14), that is, the fixed values r= 0.90, q= 250 × 365 = 9.1250 × 104 (man-night accommodation), with arange of independent variables:

Relationship (12) shows the dependence of the portfolio of tours and accommodation on business risk, as well as the ratio of average fixed costs to total revenues. Hence, the optimisation depends on the estimated (or accepted) business risk and the proportion of fixed costs per unit of product and total sales. Therefore, with the growth of fixed costs (investment) compared with sales, the diversification (with fixed risk r) decreases. Consequently, arelatively small cash flow compared with investment means that the entrepreneur must focus more on the benefits of scale than on minimising business risk. This risk can be expressed by adjusting EquationEquation (11)(11)

(11) as follows:

Where:

We transform the coordinate system x, y, zto view agraphical optimisation of the xdiversified portfolio accommodation variables such that

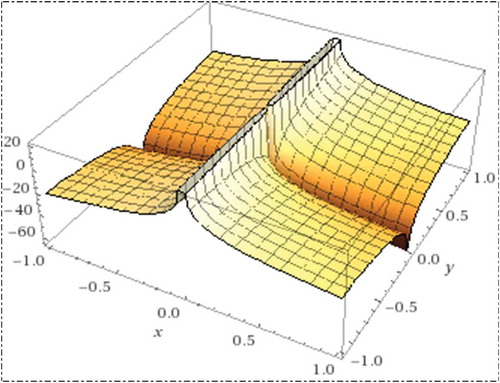

Figure 2. Dependence of diversification of production on fixed costs (x) and total revenue (y) at risk r= 0.1.

Source: Results from our calculation (2019).

From Figure , it is apparent that adiversified portfolio of peak production is achieved around zero points of fixed costs, and the maximum rate of diversification is in the situation where the investment costs are relatively small compared with total sales. The discontinuity solution of diversified portfolio variables can also be seen when the total sales are around zero points. If the conditions of the variables listed under (13) are not met, the graphical solution of (12) must be done in acomplex representation, as shown in Figure .

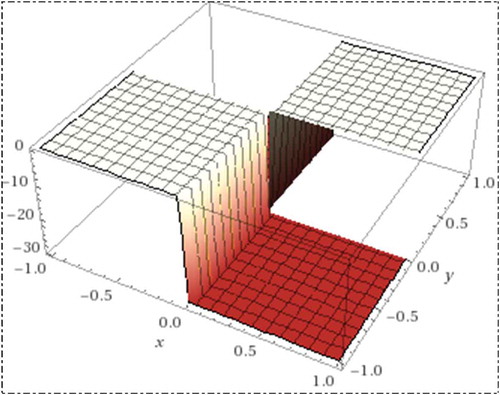

Figure 3. Imaginary part of the solution of expression (12).

Source: Results from our calculation (2019).

The imaginary part of the accommodation offers asolution in such ahypothetical case (e.g. by negative revenue). Negative revenue occurs when producers pay customers after removal of the product (e.g. if the product is accompanied by aharmful substance that is greater than the utility of the product).

4. Results

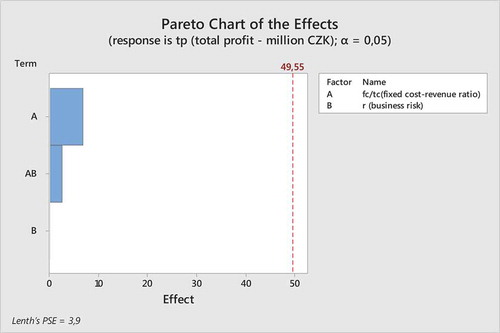

The first step in the factorial experiment was detecting the factors and interactions influencing the mean of the responses (diversification of accommodation and total profit). The results of the experiment are shown in Table . For the significance test, asignificance level of α = 5% (0.05) was selected. Then, if the p-value was less than the significance level (0.05), the factor or interaction was statistically significant. This experiment showed that there were no main effects of the diversified production portfolio or total profit, and no interaction effects were statistically significant. This finding is further supported by aPareto plot (see Figure ) and normal plot of the standardised effect (see Figure ). The description of the diversified portfolio variables and the value ranges is shown in Table . The coded settings of these variables for the experimental trials are mentioned in Table .

Table 1. Diversified portfolio of accommodation offers to maximise profit

Table 2. List of process parameters for the experiment

In the Pareto plot (Figure ), any factor or interaction effect extending past the reference line is considered significant. The calculated effect factor in the un-coded values (response factor to achange from (–1 to +1)) is shown in the first column of Table . Thesecond column represents the regression coefficient (half of the effect of each factor).

Figure 4. Pareto plot shows no significant parameters and no significant interaction.

Source: Results from our experiment (2019).

Table 3. Coded coefficients for x(Diversification of accommodation offers)

Tables and show the estimation of the coefficients for determining the predictive equations of the diversified portfolio and total profit responses. Data from 21 randomly selected travel agencies were used for estimating the regression coefficient values.

Table 4. Regression equation for Diversified Portfolio in un-coded units

Table 5. Coded coefficients for tp (Total profit [million CZK])

The procedure for calculating the regression parameters was introduced, for example, in Antony (Citation2003). Data from 21 randomly selected travel agencies were used for estimating the regression coefficient values.

5. Conclusion

As shown by the Pareto graph in Figure , as well as Tables and , the statistical estimate of regression parameters for predicting the accommodation portfolio diversification and total production gains in the reporting period was not statistically significant. In these situations, it is useful to create an analytical solution for finding the number of diversified products in afixed cost–total revenue ratio and business risk (in addition to finding adifferent model, for example, polynomial). This analytical solution represents the original proposal of the authors of the article for eliminating the disadvantage of the statistical solution, which often (in contrast to an analytical solution) does not express the causality between control and controlled variables (in this case, diversification of the product portfolio, risk of business activities and average fixed cost–total revenue ratio).

The research question on the possibilities of finding the analytical form of diversification of accommodation was proven through relationship (12). The practical functionality of the solution was verified by the consistency of the settlement of relation (12) with Tables and .

Table 6. Regression equation for Total Profit in un-coded units

Group’s Key Research Activities

Recently, the authors’ team was developing new methods for the design of experiments, especially for the operational level of management. The authors’ team has encountered arelatively frequent phenomenon where the statistical (or regression) model does not imply causality between individual factors of abusiness process (often due to the confounding factor) in this field. Therefore, the authors’ team is currently interested in verifying the causality of regression models and eventual transformation from regression to causal form with afocus on business processes. The continuity of this research and the topic of the article is that we have created an analytical (causal) model for generally finding the total optimum level of portfolio diversification. This model thus slightly contradicts previous approaches argued that it is possible to maximize profit only at higher variability (at higher risk).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Czech University of Life Sciences Foundation, and the paper was written under the framework of IGA project 2019B0006: ‘Management Attributes of Alternative Business Models in Food Production’ (Atributy řízení alternativních business modelů vprodukci potravin). The authors also gratefully acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for carefully reading the manuscript and providing several useful suggestions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tomas Macak

Tomas Macak earned his PhD at the Czech Technical University (Faculty of Mechanical Engineering), Prague, in 2006. Currently, he is an associate professor of Management at the Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague.

Jan Hron

Jan Hron is a full professor and former Rector of the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague (CULS). His research focuses on transdisciplinary approach for exploring regulatory systems, their structures, constraints, and the application of cybernetics to management and organizations.

Monika Jadrna

Monika Jadrna earned her PhD at the Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague. Her dissertation topic was designing experiments for international tourism business management and operational management. Currently, she is senior lecturer of Management at the Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague.

References

- Assaf,A., & Tsionas, M.G. (2019). Revisiting shape and moderation effects in curvilinear models. Tourism Management, 75, 216–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.05.007

- Stoffelen,A., & Vanneste, A.D. (2018). The role of history and identity discourses in cross-border tourism destination development: AVogtland case study. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8(2018), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.04.003

- Tahir,A., & Meltem,C. (2018). A motivation-based segmentation of holiday tourists participating in whitewater rafting. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9(2018), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.11.001

- Alcántara-Pilar, J.M., Armenski,T., Blanco-Encomienda, F.J., & Del Barrio-García,S. (2018). Effects of cultural difference on users’ online experience with adestination website: Astructural equation modelling approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8(2018), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.06.002

- Arrais-Castro,A. (2018). Collaborative framework for virtual organisation synthesis based on adynamic multi-criteria decision model. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing, 31(9), 857–868. DOI: 10.1080/0951192X.2018.1447146

- Bettis, R A, & Hall, W. K. (2002). ‘diversification strategy, accounting determined risk, and accounting. Determined Return. Academy Of Management Journal, 25(2), 254-264.

- Montgomery, C.A., & Wernerfelt,B. (1998). Diversification Ricardian Rents and Tobin’s Q. Rand Journal of Economics, 19(4), 623–632. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555461

- Markides, C.C., & Williamson, P.J. (2004). Related diversification, core competencies and corporate performance. Strategic Management Journal, 15(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250151010

- Lueckenbach,F., Baumgarth,C., Schmidt, H.J., & Henseler,J. (2019). To perform or not to perform? How strategic orientations influence the performance of Social Entrepreneurship Organizations. Cogent Business & Management, 6. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1647820

- Sung,G., Woo,L., & Paek,S. (2019). How important is F&B operation in the hotel industry? Empirical evidence in the US market. Tourism Management, 75, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.03.010

- Li,H., Xu,Y.-H., Li, X.(., & Xu,H. (2019). Failure analysis of corporations with multiple hospitality businesses. Tourism Management, 73, 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.01.018

- Anand,J., & Singh,H. (2007). Asset redeployment, acquisitions and corporate strategy in declining industries. Strategic Management Journal, 18(Special Issue), 99–118.

- Antony,J. (2003). Experimental design for industrial engineers and business managers using simple graphical tools, Butterworth-Heinemann. in press.

- Reichenecker,J. (2019). Diversification effect of standard and optimized carry trades. The European Journal of Finance, 25(8), 745–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.01.018

- Stimpert, J.L., & Duhaime, I.M. (2007). Seeing the big picture: The influence of industry, diversification and business strategy on performance. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 560–583. DOI: 10.2307/257053

- Dolores,M., Sabiote-Ortiz, C.M., Martín-Santana, J.D., & Beerli-Palacio,A. (2018). Antecedents and consequences of cultural intelligence in tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8(2018), 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.07.006

- Su,M., Wall,G., Wang,Y., & Jin,M. (2019). Livelihood sustainability in arural tourism destination - Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tourism Management, 71, 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.019

- Tot,M. (2019). Effects of bank capital on liquidity creation and business diversification: Evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Asian Economics, 61, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2018.12.001

- Hasan, M.K., Ismail, A.R., & Islam, M.F. (2017). Tourist risk perceptions and revisit intention: Acritical review of literature. Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1412874. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2017.1412874

- Bielstein,P. (2019). Mean-variance optimization using forward-looking return estimates. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 52(3), 815–840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-018-0727-4

- Ma,R. (2017a). Diversification and target leverage of financial institutions. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 46, 11–35.

- Ma,R. (2017b). Export market diversification and innovation capability of Chinese firms: The moderating effect of export product. Conference: 2nd International Conference on Economics and Management Innovations (ICEMI), 1(1), 103–105.

- Bettis, R.A., & Hall, W.K. (2002). Diversification strategy, accounting determined risk, and accounting determined return. Academy of Management Journal, 25(2), 254–264. DOI: 10.2307/255989

- Rumelt, R.P. (1992). Diversification strategy and profitability. Strategic Management Journal, 3(3), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250030407

- Ramires, A, Brandao, F, & Sousa, A. C. (2018). Motivation-based cluster analysis of international tourists visiting a world heritage city: the case of porto, portugal. Journal Of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 49-60.

- Chatterjee,S., & Wernerfelt,B. (2001). The link between resources and type of diversification: Theory and evidence. Strategic Management Journal, 12(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120104

- Park,S., & Seyoung,S. (2019). Linear programing models for portfolio optimization using a benchmark. European Journal of Finance, 25(5), 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2018.1536070

- Stoffelen, Arie, & Vanneste, A. D. (2018). The role of history and identity discourses in cross-border tourism destination development: a vogtland case study. Journal Of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 204–213.

- Duman,T., Ozbal,O., & Malcolm,D. (2018). The role of affective factors on brand resonance: Measuring customer-based brand equity for the Sarajevo brand. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8(2018), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.08.001

- Shah,T. (2019). Does the number of holdings in arisk parity portfolio matter? Journal of Asset Management, 20(2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.08.001

- Andersson, T.D., Mossberg,L., & Therkelsen,A. (2017). Food and tourism synergies: Perspectives on consumption, production and destination development. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1275290

- Toth, G, & Lengyel, B. (2019). Inter-firm inventor mobility and the role of co-inventor networks in producing high-impact innovation. Journal Of Technology Transfer. doi: 10.1007/s10961-019-09758-5