Abstract

Director selection is linked with contradictory board roles which call for the need of multiple approaches. In cooperatives, which are member- and user-driven rather than profit-driven, this approach is essential. The aim of this study is to analyze director selection in agricultural cooperatives by using a qualitative approach and hence, contribute to theory development. The results indicate that the director selection process and roles contain several paradox issues in two dimensions: administrative culture as well as the roles and authority of important actors. The paper contributes to the understanding of (1) mechanisms and relationships inherent in the process of director selection in agricultural cooperatives (2) the administrative culture as well as the roles and authority of the actors in the process and (3) paradoxes which help us to understand tensions in director selection under the requirement of fulfilling both the performance task and the conformance task. The paper discusses the results against the current board theories and suggests a new paradox dimension. It is suggested that director selection should be studied further from the perspectives of (1) implications of the use of authority and (2) the implications of the administrative culture.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Board members have a key opportunity to influence the success of a firm. It is important that board members are selected through a well-functioning selection process. Although cooperatives are a central part of the economy, their research is limited. Our study sheds light on the processes and roles of actors involved in the election of the board of directors in cooperatives. The results show that administrative culture has a key influence on the way the board’s selection process takes shape. In addition, the role and power of the governing bodies and their chairmen are an integral part of the selection process. There are also many cross-pressures on choices, which is why researchers are introducing a new paradox perspective. The election of the cooperative’s board of directors is part of a larger entity, good governance. The findings of the study will make the good governance of cooperatives even more effective.

1. Introduction

Director selection is a part of the broader concept of board governance, which comprises board composition and board processes (e.g., Maharaj, Citation2009; Menozzi et al., Citation2012; Pearce & Zahra, Citation1992). Board governance has been studied from several different perspectives, such as board composition vis-á-vis firm performance (Murphy & McIntyre, Citation2007; Ramli & Zakaria, Citation2010), board processes (Maharaj, Citation2009), and directors’ personal values (Grant & McGhee, Citation2017), but fewer scholars have strived to link director selection to effective governance (Kim & Cannella, Citation2008).

Director selection is intertwined with board roles (Van Ees & Postma, Citation2004), of which the monitoring role with a focus on directors’ independence (e.g., Ruigrok et al., Citation2006) has been most commonly investigated. Daily et al. (Citation2003, p. 379) criticize this, claiming that “researchers too often embrace a research paradigm that fits a rather narrow conceptualization of the entirety of corporate governance to the exclusion of alternative paradigms”. Michaud (Citation2013) highlights the need for multiple approaches to understand the occasionally contradictory roles of the board of directors (BOD). This is especially important in cooperatives, which are member-owned and user-driven rather than profit-driven (Bijman et al., Citation2014). In addition to the monitoring role (Fama & Jensen, Citation1983), the service role (stewardship approach, Muth & Donaldson, Citation1998) and democratic perspectives (Cornforth, Citation2004) should be considered. Multiple approaches would help to understand the contradiction in director selection and the BOD’s role as a conflict resolution body (e.g., Bammens et al., Citation2011) in the governance of cooperatives.

Research of director selection in cooperatives is theoretically motivated by three distinctive characteristics. First, “cooperatives can be distinguished from capitalist enterprises primarily by differences in the ownership structure and the manner in which their objectives are defined and controlled” (Diaz-Foncea & Marcuello, Citation2013, p. 238). Second, the aim of cooperatives is to serve their members’ interests rather than to maximize profit (Baltaca & Mavrenko, Citation2009). And third, the decision-making processes used in cooperatives are distinctively characterized by participation and internal democracy (Diaz-Foncea & Marcuello, Citation2013). The practical relevance of the study stems from the fact that agricultural cooperatives play a central role in national economies, generating approximately 700 trillion USD in turnover worldwide (ICA Coop, Citation2018). According to Huhtala and Tuominen (Citation2016), however, academic research on board governance in agricultural cooperatives is scarce. The authors found some research on the role and position of the CEO (Bijman et al., Citation2014, Citation2013; Cook & Burress, Citation2013; Deng & Hendrikse, Citation2015), member heterogeneity (Bijman et al., Citation2013; Österberg & Nilsson, Citation2009), processes of internal governance (CitationBijman et al., Citation2013, 2014; Cook & Burress, Citation2013; Österberg & Nilsson, Citation2009), structures of internal governance (Bijman et al., Citation2014), member democracy (Österberg & Nilsson, Citation2009), director training (Österberg & Nilsson, Citation2009), election of directors (Cook & Burress, Citation2013), member participation (Barraud-Didier et al., Citation2012; Cechin et al., Citation2013) as well as ownership and control (Bijman et al., Citation2014). All these studies were quantitative, and none of them had a qualitative method as the main approach. No studies on director selection processes were found. The Finnish context is relevant in this study because Finland is considered one of the world’s most cooperative countries with high market shares of the agricultural cooperatives (Pellervo Coop Center, Citation2019).

The purpose of this study is to analyze director selection in agricultural cooperatives by using qualitative data from the 16 largest Finnish agricultural co-operatives comprising 32 in-depth chairman interviews. We use the term “chairman” to refer to chairs of both genders. We aim to answer the question: “Which processes and actor roles play an integral part in the director selection of agricultural cooperatives?” As we primarily aim at theory development (not theory verification) by providing theoretical insights, we chose qualitative methodology. Our analysis focuses on the course of director selection and does not examine directors’ characteristics or qualifications.

Our report is structured as follows: First, we analyze director selection in the mainstream research literature. Second, we describe governance and director selection in cooperatives based on the literature. Third, we present our methods, data, and context, and finally, we present and discuss the findings and conclusions of our study.

2. Director selection—Theoretical framework

2.1. Board roles and director selection

Discrete roles of the BOD, including the monitoring and service roles, have been recognized in research in an effort to understand the multiple tasks of the BOD in governance (e.g., Cornforth, Citation2004). One of the major challenges of BODs is to find a balance between the monitoring role and the service role (Huse, Citation2005). However, the two roles have only partially been able to explain the contradictions that emerge in cooperatives and other member-based, democratically owned organizations. This has suggested a need for an integrative perspective (Hung, Citation1998, pp. 108–109), which Cornforth (Citation2004) calls a paradox perspective, arguing that the multiple approach helps to explain some of the tensions and ambiguities present in cooperatives.

The governance of a firm has to fulfil two tasks: the performance task and the conformance task (e.g., Tricker, Citation2015). These tasks are not always distinct in practice, but may rather be intertwined or even mutually contradictory, because the governing bodies need simultaneously to drive forward organizational performance and to ensure that the organization functions in an accountable manner towards its members (Cornforth, Citation2004). Kim and Cannella (Citation2008) suggest that further understanding of director selection process would contribute to a better understanding of board governance.

2.2. Rational and social perspectives to director selection

In the literature on director selection, two main perspectives prevail: the rational perspective and the social perspective (Withers et al., Citation2012). The rational perspective represents a view of director selection as an attempt to meet the governance and resource needs of the firm and its owners. The social perspective emphasizes the social processes and biases that may affect director selection (e.g., Westphal & Stern, Citation2006, Citation2007). In line with the social perspective, Withers et al. (Citation2012) point out in their extensive literature review “that the self-interests of powerful individuals can drive director selection processes, challenging the fundamental assumption of the rational economic perspective” (p. 247).

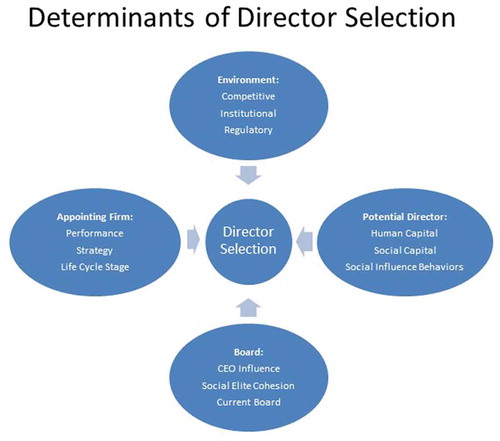

The selection process involves several internal and external determinants (Withers et al., Citation2012, see Figure ). First, the firm and its board internally steer director selection. Second, the environment where the firm operates has implications for director selection. External impulses may derive from the market, legislation, or policies. Third, the potential directors who make up the “director market” determine the available supply of prospective directors.

The rational perspective assumes that directors serve the best interests of the organization (Fama & Jensen, Citation1983), and the director selection process hence reflects an attempt to meet the firm’s monitoring role (Withers et al., Citation2012). This perspective emphasizes board composition and the level of board independence (i.e., the mix of inside and outside directors) but does not consider the individual characteristics contributed by each director to the board (Hillman et al., Citation2000). The rational perspective also complies with the resource needs of the BOD, presuming that boards of directors reduce uncertainties and bring key resources to the firm (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978), as well as with the service role of the BOD (Muth & Donaldson, Citation1998).

The social perspective (e.g., Khurana & Pick, Citation2004) highlights the social factors, such as social influence and human and social capital (Figure ). This research perspective targets the social processes and biases that may affect director selection (e.g., Westphal & Stern, Citation2006, Citation2007). Bazerman and Schoorman (Citation1983) maintain that selection of the perceived optimal director will also be influenced by political factors due to social contacts, and an optimal search will often lead to a choice made within the existing social networks.

Figure 1. Determinants of director selection to corporate board(Withers et al., Citation2012).

Withers et al. (Citation2012, Figure ) emphasize that the outcome of director selection is more than the result of the coming together of the appointing firm and the potential directors. This interaction is affected by the environment, i.e., the context of the social dynamics between the board and the external environment. Corporate governance is one of the regulatory factors. The CEO may also influence director nomination (Clune et al., Citation2014). Willpower, emotional commitment, cognitive constructs as well as ideology may be inherent in director selection (Johannisson & Huse, Citation2000), causing a need to apply both rational and social perspectives in research.

2.3. Processual perspective to director selection

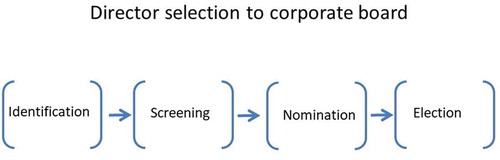

Director selection is regarded as an essential board process in enterprises (e.g., Agyemang-Mintah, Citation2015; Burke, Citation1997; Schmeiser, Citation2012). The literature hence proposes a third, processual, perspective to the director selection. Withers et al. (Citation2012, p. 245) define director selection as “the formal process by which individuals are identified, screened, nominated and elected (or appointed) to corporate boards”

Figure 2. Process of director selection to corporate board in public corporations (Withers et al., Citation2012).

The process of director selection in corporations begins by identifying potential candidates (Figure ). The candidates are usually identified and screened by a nominating committee composed of mostly independent directors (Hoskisson et al., Citation2009). Candidates can be proposed by incumbent directors, the CEO, or search firms employed to identify candidates (Withers et al., Citation2012). In the past, many board members were selected by CEOs based on their personal relationships, affiliations, or friendships (O’Neal & Thomas, Citation1995).

However, attempts have been made to professionalize selection through the appointment of nomination committees (NC) (Ruigrok et al., Citation2006). NCs are believed to improve the board’s effectiveness through managing its composition by, for instance, improving the directors’ qualifications and enhancing board independence (Kaczmarek et al., Citation2012). Some organizations take a critical stance to NCs. Ruigrok et al. (Citation2006) maintain that CEOs who simultaneously serve as chairmen of the board have a critical attitude to a standing NC, which could reduce their influence on the selection of potential board members. The final stage of the process is the election in the general assembly or some other body specified in the company rules.

In sum, three perspectives, the rational, social and processual, have been proposed in the existing literature.

3. Board governance and director selection in cooperatives

3.1. Hallmarks of cooperative governance

The governance of cooperatives is both similar to and different from the governance of other firms. It is similar in that the members of a cooperative own the firm and act as principals to the board and the management (Diaz-Foncea & Marcuello, Citation2013). What is different is that the members are also users of the firm and have transactions with it. This member duality per se is a paradox and has several consequences for governance. Gui (Citation1991) calls this a mutual benefit, and Diaz-Foncea and Marcuello (Citation2013) clarify this by stating that those who have the power to make decisions in cooperatives can manage the organization for their own benefit. Therefore, in general, cooperatives are more closely controlled by their member-owners than are investor-owned firms (IOF) (Hansmann, Citation1999). However, while the owners of an IOF usually have uniform interests to obtain a high return on investment the members of a cooperative may be heterogeneous in their interests (Bijman et al., Citation2013). This heterogeneity may have a serious impact on the efficacy of the cooperative (Hansmann, Citation1996) and cause tension between board members acting simultaneously as representatives for particular stakeholder groups and as “experts” pursuing the performance of the organization (Cornforth, Citation2002). It should further be noted that cooperatives lack external mechanisms for disciplining their management (Staatz, Citation1987; Trechter et al., Citation1997). The task of performance evaluation mainly lies with the members and their representatives on the BOD.

3.2. Director selection in agricultural cooperatives

As regards BOD selection, there is no single way to find board candidates to cooperatives. In his report of agricultural cooperatives, Reynolds (Citation2004) points out that large cooperatives often select their candidates differently from those with relatively few members. For instance, some cooperatives strive to include directors in NCs with the assumption that they know what capabilities are most needed on their board. A possible weakness in this arrangement is that incumbents may exclude candidates who could be critical of current board work, or that director control over candidate selection may make members feel that they have no real influence on the selection process (Reynolds, Citation2004).

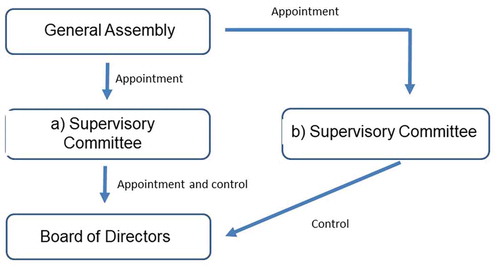

The agricultural cooperative’s governance structure affects how and by whom directors are selected. In the basic traditional model, called one-tier model (Bijman et al., Citation2014), directors are appointed by the general assembly (GA), also called the members’ meeting. In the more developed supervisory committee model, called two-tier model, the supervisory committee (see Figure ) may appoint the directors (Bijman et al., Citation2014; Henrÿ, Citation2012). However, it should be noted that cooperative legislation varies across countries. This means that in some countries, the supervisory committee has the authority to appoint the directors (Figure , option a), whereas in some other countries it only controls the directors (Figure , option b) without authority to appoint them.

Figure 3. Supervisory committee model of governance structure in agricultural cooperatives(developed by the authors, based on Bijman et al., Citation2014).

4. Methodology

4.1. Choice of method

Our study aimed at theory development (not theory verification or testing). We therefore chose to use a qualitative research strategy (e.g., Yin, Citation2009). “Qualitative methodology can provide “a ‘deeper’ understanding of social phenomena than would be obtained from a purely quantitative methodology” (Silverman, Citation2006, p. 56). The method used in this study was inductive, which means that the aim of the study was specified along with the research process and parallel to the accumulating understanding of the phenomenon of interest (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Gioia et al., Citation2013).

4.2. Sampling and target group

Our data sampling was theoretical (not random) because the purpose was to develop theory, not to test it. Our data comprises Finnish agricultural cooperatives (Appendix –), which are suitable for illuminating the constructs and patterns behind the phenomenon under study. Finland was chosen as the setting because Finnish agricultural cooperatives represent an essential part of the national economy and comprehensive data were available.

We included in our series the 16 largest cooperatives of Finland based on the number of members in 2014. These cooperatives account for over 99% of the entire turnover and over 95% of the members of all Finnish agricultural cooperatives. Divided by sector, there were nine dairy cooperatives, four meat cooperatives, one animal breeding cooperative, one forestry cooperative, and one egg cooperative in the series. The total turnover of the selected cooperatives without their subsidiaries was up to 2.9 billion euros. The data on this period were comprehensively available and consistent. The key figures of these cooperatives are presented as a time series in Appendix 1–4.

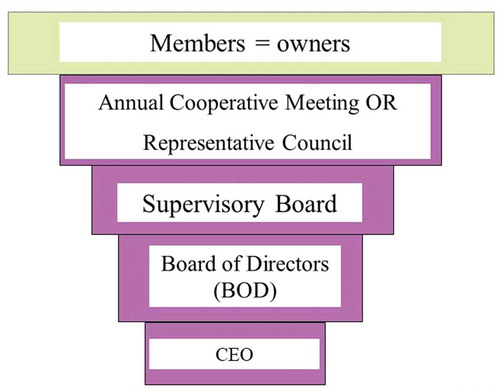

A structural model of the Finnish cooperatives is presented in Figure . According to the Cooperative Act of Finland (2014), the obligatory bodies of governance are the annual cooperative meeting and the board of directors (BOD). The annual meeting can be replaced by a council of delegates constituted through member election.

There are several variations of this model, and each cooperative may stipulate their own structure in the bylaws. Our target group includes the following variations (Table ):

Table 1. Alternative models of Finnish agricultural cooperatives

Twelve of the 16 cooperatives in our series have a council of delegates, and eleven cooperatives have a supervisory board. Cooperatives with a high number of members are more likely to have a council of delegates than those with fewer members. No such pattern is seen regarding the presence of a supervisory board. All the cooperatives covered here have an appointed CEO.

4.3. Data

Open-ended in-depth interviews were used. We interviewed (Appendix 5) 32 persons: all the 16 chairmen of the BODs, all the chairmen of the supervisory boards (11 people), and in the five cases without a supervisory board, the chairmen of the representative councils. Two of the chairmen were female. To mitigate biases, we used a maximum number of not only chairmen of the BODs (who participate in director selection) but also chairmen of the supervisory boards or representative councils. The focus in the interviews was on people’s views and thoughts about the governance structure, the election procedure, the official and unofficial discussions, the roles of the different actors as well as the local values and traditions (Appendix 5). The technique of semi-structured interview was used, and the material thereby obtained constituted our primary data. The bylaws of the cooperatives were also analyzed, and that analysis was used as supportive data.

The composition and key element of the data are described in the Table :

Table 2. Key elements of data

4.4. Analysis of data

Our research question is: How do chairmen describe the process and the roles in the director selection of agricultural cooperatives? The aim of the study is to develop theory (not to verify it) by providing theoretical insights, and we hence chose qualitative methodology. According to Eisenhardt and Graebner (Citation2007), the theory-building process includes cycling between the data, the emerging theory, and the extant literature. We used a stepwise qualitative analysis (Gioia & Thomas, Citation1996) to sort out the data. We began our analysis by reading the interviews and recognizing the informants’ views, which allowed us to create the first-order concepts (Gioia et al., Citation2013; Gioia & Thomas, Citation1996; Langley, Citation1999; Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985; Locke & Golden-Biddle, Citation1997). These concepts can also be considered the first-stage abstraction. This level of analysis describes and represents the interviewees’ comments. At this stage, we adhered to the informants’ terms and made only a minimal attempt to filter the concepts. All of the included 43 concepts (Table ) were mentioned by the informants a minimum of two times. The number of concepts was quite high, but according to Gioia et al. (Citation2013), it is important to have an adequate number of concepts. Next, we started searching for similarities and differences between the concepts and created 10 second-order themes (Gioia & Thomas, Citation1996). This level of analysis approaches in-depth abstraction and enables the researchers to illustrate the concepts. Along the lines of Gioia and Thomas (Citation1996) and Gioia et al. (Citation2013), we then further filtered the emergent second-order themes into two aggregate dimensions, which together constituted our data structure. We analyzed and classified the data several times in order to obtain a rigorous, comprehensive set of themes and dimensions.

Table 3. Development of the data structure from first-order concepts through second-order themes to aggregate dimensions

During our analysis, we realized that the two aggregate dimensions in Table contained mutually opposite, competing or otherwise contradictory approaches to director selection. To provide a better understanding of the phenomenon under study we outlined a new perspective that we call paradoxes of director selection (Table ). We define a paradox as a situation that involves two or more facts or qualities that seem to contradict each other.

Table 4. Formation of the perspective Paradoxes of director selection

The nature of the paradoxes is discussed in detail in chapter 5.1.—5.3.

To enrich the data analysis, we classified our series of 16 cooperatives into three categories based on their mission: (1) ownership cooperatives, (2) marketing cooperatives, and (3) procurement cooperatives (Table ). Mission was determined by analyzing the bylaws and the actual operations of the cooperatives as well as the information given by the informants. The classification contributes to the recognition of deeper patterns when analyzing the results later in chapter 5.

Table 5. Division of the cooperatives based on their mission

5. Results and findings

Table shows that our aggregate dimensions and second-order themes involve several paradoxes in director selection. We will now discuss each of the paradoxes separately.

5.1. Administrative culture

Director selection begins with a process of mapping out candidates when a vacancy has been opened. Regional producers and elected officials may organize events where the topic is discussed. A query in writing may be sent to the members of the representative council or to the regions, asking them to identify suitable candidates and to check their willingness to run for candidacy. While the CEO may be asked about suitable candidates, he/she is kept strictly apart from the actual nomination and election process in all cooperatives.

The main route to the selection process is the cooperative’s own governance. Possible candidates are primarily and traditionally identified or searched from among resigning board members, from the supervisory board, or from the representative council. “People usually reach the highest governance positions through membership of the supervisory board”. Some cooperatives, however, increasingly search candidates from among the active members of their cooperative or even outside the cooperative. “If necessary, we even try to find suitable outsider candidates”. This raises controversial thoughts because it is not a traditional route to the BOD.

Collective selectionis the traditional way to have a larger group, typically the supervisory board or the representative council, collectively work as the evaluator “there is no preparatory organization … but things happen through unofficial discussions” and the nominator “the official part is limited to the supervisory board meeting preceded by the nomination, where the matter can be taken up and confirmed”. The cooperatives applying collective selection do not appoint NCs. Some other cooperatives have NCs or consider appointing one in the future. They emphasize the benefits of NCs, e.g., a systematic approach to election. “This committee, it makes a proposal to the supervisory board after it has surveyed the available candidates”. “We have had a nomination committee for years in the supervisory board … it brings a kind of orderliness to the election process, it is no longer possible to have surprising new candidates pop up in election meetings.”

The renewal of board members raised divergent thoughts. Most of the informants who commented on the theme thought that incumbents should primarily be re-elected if they still have the motivation. “Nobody has been fired from the BOD, they resign because of their age or termination of their farm operations”. Signs of a changing selection culture could be seen among those who suggested that the overall external environment (e.g., market, regulation), other incumbents, and the prevailing needs of the BOD should be regarded when renewing the composition of the BOD. These informants emphasized the importance of renewal and were ready to set a maximum time for the mandate period. While diverging opinions arose between the informants, no differences could be seen across the three categories of cooperatives (see Table ).

As regards external factors, outside stakeholder groups do not have any say on the choices. “No outsider, no … bank or farmers’ union … of course not … but in member council election they may nominate candidates just like anybody else.” In some cooperatives, previous experiences of outside stakeholders still caused dubiousness: “The reason (for not accepting outside candidates) have been outside actors who have strived to influence the functioning of the governance.”

5.2. Roles and authority of actors

The role of the BOD in director selection is to rate the suitability of different people and to examine the candidates’ backgrounds. The BOD’s role is rather prominent in the early stages of the selection process but diminishes towards the end of the process. When candidates are mapped out and informal discussions about them are carried out, the role of the BOD is essential. “We on the BOD naturally discuss the persons who have shown interest and activity”. Later in the process the BOD’s role is felt to be less consequential and more controversial.

The BOD should not attend; in practice we are asked … members of the supervisory board call us and ask what kind of fellow this person is and what we think about him … it is collaboration, but we operate in the background when we are asked.

The primary role of the supervisory board and the representative councils to communicate with the regions and the members and to analyze the candidates. “Unofficial discussions are carried out, and it is actually the duty of the leading elected members to observe governance … and to figure out the matter … so that we are ready when vacancies come up.” Their role also includes—depending on the legislation—the final stage, where they elect or appoint the BOD. Our informants said that the electing body has the ultimate authority to make the decision either based on the proposals or without any proposal. If necessary, the electing body takes a vote.

Regional interests are a central theme in director selection. The role of the regions may be so strong that the elector, i.e., the supervisory board, needs to have well-argued reasons for differing from the regions’ proposal. However, the role of the regions seems to be in transition: while the traditional role of regions is still rather strong, and regionality is regarded as a built-in aspect of cooperatives and an indication of their democratic nature, some informants think that regions should not influence the selection of directors at all. Some cooperatives have “gentleman’s agreements” on regional balance of the BOD. “It is discussed in the regions how their representation is secured on the BOD”. This causes controversial situations where some cooperatives (especially procurement cooperatives) emphasize the central role of the regions, whereas some others strive to minimize the active role of the regions. “Regional committees have pretty much power in the selection of the supervisory board and also try to apply it to the selection of the BOD, but this has been absolutely prevented”.

The role of the NC is to identify the needs of the BOD in advance and to carry out discussion about people and their characteristics. “The nomination committee talks about names and potential candidates, especially board professionals who are outsiders and who are searched for”. The NC is usually permanent, although some cooperatives prefer an ad hoc committee for each individual nomination. If a cooperative has a permanent NC, it may identify the future needs of the BOD at any stage of the selection process. “We have had a nomination committee for years in the supervisory board … it brings a kind of orderliness to the election process, it is no longer possible to have surprising new candidates pop up in election meetings.”

The role of the chairs of the BOD, the supervisory board as well as the representative council are multiple and intertwined. The BOD chairman functions as a middleman between the BOD and the supervisory board/representative council. He or she is an expert who is consulted by the nomination committee, where his role is to inform the committee about the competence needs of the BOD and about the environment. “Chairmen of the BOD attend the nomination committee as experts. They are not actual members, but their role is to answer questions about how the BOD is working”. At the same time, he maintains contacts with the other directors of the BOD and is ready at all times to answer questions concerning candidates or the situation on the BOD. The BOD chairman not only discusses the candidates but is also considered responsible for the selection of suitable candidates. “ to give information on what the BOD stands for … some members of the representative council may have no idea of what is required in the work of the BOD”. The chairman may be asked about prospective candidates. He and the BOD may check out candidates’ backgrounds and even headhunt for candidates. “My (chairman of BOD) opinion is not a crucial factor, but I think it is good for me to attend the preparatory discussion”. It should be noted that the BOD chairman’s role is informal, and he or she has no formal authority in this question. The challenge of the BOD chairman is to find a balance between being active, neutral, or passive in the process of director selection. The marketing cooperatives tend to think that the BOD chair should have a say if he knows of a person who is just right for the needs; however, most informants think that the chairman of the BOD should remain more or less outside of the selection process or at least the final election. “BOD members should not be active in that process”.

The supervisory board chairman is the most influential of all chairmen and has a central role in coordinating the discussion on selection. He or she alone, or in some cooperatives together with the chairman of the BOD, often steers the discussion behind the scenes. “The chairman of the board of directors and the chairman of the supervisory board make up a twosome”. The further the selection process progresses, the more important is the role of the supervisory board and its chairman and the less central is the role of the BOD and its chairman. A few informants pointed out that the supervisory board chair should not have a visible role but should rather function as a coordinator and let the members of the supervisory board take the main role. The representative council chairman has a role in initiating the process and in encouraging early-stage discussion about potential board members. On the other hand, the informants said that the chair should keep his/her integrity and be careful not to promote any particular candidate.

Summary of the paradoxes of director selection:

Table shows that the data involve several controversial issues causing diverging perspectives. The perspectives are not necessarily either/or issues but may be present simultaneously. We call them paradoxes in this study and will discuss them in more detail in the next chapter.

Table 6. Paradox issues and their nature in director selection

6. Discussion

Our research question was “Which processes and actor roles play an integral part in the director selection of agricultural cooperatives?” Our results indicated that the chairmen approach the question through several paradoxes from two dimensions: (1) administrative culture, (2) roles and authority of important actors. We will discuss here the results against the existing theoretical approaches to the selection of directors (processual, rational, and social dimensions), against some central theories of board work (agency, stewardship and democratic) and with reference to the current literature.

A major paradox in the administrative culture of cooperatives prevails in the search process of candidates and in the process of how candidates can get promoted to the BOD. Both governance-driven and membership-driven search processes were found, but promotion to the BOD was mainly through the representative council or the supervisory board, depending on the cooperative’s governance structure (see Figure ). Parallel to this, new ways to identify and promote candidates have been adopted. Some cooperatives pick up candidates directly from the membership outside the representative council or the supervisory board. A few cooperatives select outside directors (who belong neither to the governance nor to the membership), and increasingly more cooperatives seem willing to start doing that in the future. A third paradox in the administrative culture concerns the issue of the preparatory process: whether the selection is steered in the traditional way by having the governance collectively discuss the candidates or the NC working on the preparation. In larger cooperatives, the NC more often has a distinct role in discussing the candidates and making a proposal. Our informants’ opinions about the need for an NC varied. Those who did not consider it necessary said that they want to secure regional representation on the BOD and do not want to shift decision power from the supervisory board or the representative council to an NC. Reynolds (Citation2004) reported having encountered a similar worry that incumbents in the NC could control the selection, while the members would not have any real influence on the selection process. Those holding an opposite view maintained that without an NC the election becomes too informal.

The authority of the governance bodies is stipulated in the Cooperative Act of Finland (representative council, supervisory board, BOD) or in the bylaws of each cooperative (NC). It is hence unambiguous that the supervisory board (or the representative council) ultimately elects the BOD. However, the roles and authority mandates of the actors are seemingly intertwined with the personal power of the chairs and the power of the regions, which causes paradoxes. One paradox lies in the relations between the regions and the governance bodies. Due to the social pressure by the regions, the supervisory board—despite its formal authority—may need to “listen” to the regions, which may have a remarkable influence on the selection. Another paradox is the role of the BOD chair. He or she does not have any formal authority over the selection but may be crucially involved in the background processes. The supervisory board and the BOD chairs, sometimes together with the vice-chairs, typically initiate and steer the discussion. These observations support Withers et al. (Citation2012) notion about powerful individuals who can drive director selection processes, however, so that no evidence of chairmen’s self-interests was observed. The role of the NC depends on how long the committee has been in use, how detailed its directive is, what the composition of the committee is, and how clearly and publicly its role has been defined and communicated in the cooperative. In a few cooperatives, the position of the NC was considered somewhat controversial or fuzzy.

From the processual dimension, director candidates in corporations can be incumbent directors, CEOs, or outsiders (Withers et al., Citation2012). Candidates are usually identified and screened by nominating committees (e.g., Ruigrok et al., Citation2006). Our results revealed a few distinct differences between agricultural cooperatives and corporations. Directors are primarily sought from among the cooperative’s own governance, i.e., incumbent resigning directors, supervisory board, or representative council. Only secondarily are candidates searched from among the membership or from outside the cooperative. CEOs are BOD candidates less often than previously because agricultural cooperatives have increasingly adopted bylaws which exclude CEOs from BODs.

In corporations, attempts have been made to professionalize the selection process through the appointment of nomination committees (Ruigrok et al., Citation2006). This is not necessarily true of agricultural cooperatives. Identification and search of candidates are often done collectively by regions, supervisory boards or representative councils. Agricultural cooperatives typically start the screening of candidates informally through discussions and observations. These discussions are carried out on the supervisory board, between the leading chairmen, on the BOD, in the representative council, collectively in the governance, and in the regions. This phenomenon might not be equally common in corporations, where ownership is often more centralized than in cooperatives.

The director selection process in agricultural cooperatives may involve some practical problems, such as lack of information or delayed information about director vacancies. In addition, the traditional identification model, where candidates are searched through discussions across the entire governance, discussions in regions, or mutual discussions between the leading governance members, seems prone to disorderliness and possible tensions between the BOD and the supervisory board (representative council). Developing the professionality of nomination was a key issue for many agricultural cooperatives. Electors should evaluate and challenge the director candidates. The overall situation on the BOD should be considered, and the transparency of the election process should be increased. In these cooperatives, NCs are becoming increasingly common. Their benefits include orderliness of screening and nomination and organized discussions between the supervisory board (representative council) and the BOD. The roles of the BOD and its chairman are also more clearly defined than in the traditional identification model: the chairman’s duty is to inform the NC of the needs on the BOD, although he or she does not intervene in the actual appointment. It is noteworthy, however, that many agricultural cooperatives were critical of the NC, which is often assumed to endanger the traditional way to favor regionality in director selection and to play too big a role in the nomination process.

From the rational dimension, directors usually serve, in the spirit of the agency theory, the best interests of the organization by attempting to meet the firm’s monitoring and resource needs (Withers et al., Citation2012). Our results indicate that agricultural cooperatives do not prefer outside directors as the main way to organize the monitoring function. Rather, the requisite monitoring is achieved by having regional representation on the BOD, and if not there, at least on the supervisory board. The regional aspect is regarded as a built-in feature of cooperatives, and it is especially conspicuous in procurement cooperatives. On the other hand, in line with the stewardship theory (Muth & Donaldson, Citation1998), which emphasizes the significance of the service and strategic role of the BOD, the representational view in agricultural cooperatives is giving way to competence needs: the results indicate that directors’ attributes, such as skills and personal characteristics, are becoming increasingly important. This coincides with the views of Cornforth (Citation2004), who maintains that board members in member-based organizations should have expertise and experience that can add value to the organization’s performance, and that directors should therefore be selected for their professional expertise and skills. In our case, this applied especially to large ownership cooperatives and marketing cooperatives. A remarkable change has taken place in the relationships with the farmers’ union: unlike earlier, informants were critical of its role in the selection of directors. Our results do not support the observation that outside stakeholders or political actors would significantly affect director selection in agricultural cooperatives. Overall, it is safe to say that director selection in agricultural cooperatives is moving from lay thinking into a more professional direction.

From the social dimension, i.e., when considering the impact of social influence as well as human and social capital on the selection process, our findings revealed that the nature of the cooperative’s administrative culture affects the selection process. Following the democratic perspective (Cornforth, Citation2004), the informal influence of the region is considerable, notwithstanding our notion that the regional emphasis is diminishing. In view of the facts that the primary access to the BOD proceeds from the membership through the governance, and that the incumbent directors are often favored compared to new directors, this perspective, which can be called the “traditional administrative culture”, may be at odds with the rational dimension causing paradoxes and possibly power struggles between the regions/membership and the governance bodies (BOD, supervisory board). Given that the governing bodies are responsible for both the organizational performance and the conformance of the operations to the needs of the membership (Cornforth, Citation2004; Tricker, Citation2015), the challenge to reconcile the rational and the social dimensions, especially in a challenging regulatory and market environment, is a major issue for agricultural cooperatives.

Compared with corporations, director selection is less BOD-driven in agricultural cooperatives, which reflects the democratic and social nature of these organizations. The supervisory board and its chairman influence selection across the entire process. The BOD’s and its chairman’s influence, which primarily takes the form of informal use of power, concentrates on the early and middle phases of the process. The NC plays a central role, especially in formal evaluation and nomination. In addition, given that the NC is most commonly chaired by the chairman of the supervisory board, who often has a powerful role in the committee, the influence of the committee may be even bigger.

The tradition of mutual discussion is strong in all cooperatives, but the culture of discussion varies across them. What is common to all cooperatives is that the chairmen at all levels of governance, i.e., the BOD, the supervisory board, and the representative council, influence director selection through informal and occasionally extensive discussions on candidates. The most influential person who also has formal authority in the selection is the chairman of the supervisory board. The chairman of the BOD also has an essential role, though his or her involvement is less direct and takes place at an earlier stage than that of the chairman of the supervisory board. Opinions differ as to whether the discussions should be carried out collectively in bigger groups or in smaller groups between the chairmen or in the nomination committee. Given that cooperatives are generally much more closely controlled by their member-owners than are investor-owned companies (Hansmann, Citation1996), and that the members of agricultural cooperatives have a specific interest in the cooperative which they extensively patronize, the chairmen’s use of power in director selection emerges as a central social mechanism.

In the corporate literature, CEOs are reported to play a central role in the director selection of corporations (e.g., Clune et al., Citation2014). In the Anglo-Saxon corporate culture, CEOs are typically members or even chairmen of the board (Chisholm, Citation1985; Johnson et al., Citation1996; Monks & Minow, Citation2004). Our findings do not support a powerful role of the CEO in cooperatives’ director selection. Some CEOs may be asked about potential candidates at the screening phase, but otherwise, they are kept apart from nomination and election.

Director selection in the studied cooperatives often raises tensions which affirms the observation of Bijman et al. (Citation2013) that the members of a cooperative may be heterogeneous in their interests. Regional aspirations play a big role in the director selection of agricultural cooperatives. The argument for the representative view in director selection stems from a theoretical approach to cooperative governance called the democratic perspective (Cornforth, Citation2004), which underlines that board members are lay representatives and there to serve their constituencies or the stakeholders they represent. This argument can be criticized in the context of our case, because the Finnish Cooperative Act says that the duty of the BOD is to promote the benefit of the entire cooperative rather than any individual subgroups. Another observation is that the aspirations of regional and other representatives may be at odds with the aspiration of electing competent directors.

In terms of the context and the traditions in cooperatives, Komulainen (Citation2018) states how Finnish cooperatives have historically had a strong regional emphasis with the “local spirit” (p. 62). Siltala (Citation2013, p. 186) maintains that a fundamental problem among the leaders of a large Finnish forest cooperative was an overemphasized member-advocacy which happened at the cost of the industrial processes. Another common tradition that still was in power in the 1980s were cross-memberships across producer cooperatives and the farmers’ union MTK. Double roles were seen, e.g., in the forest owners’ cooperative (Kuisma et al., Citation2014, p. 78). Karhu (Citation1999) states how the 1980s and the early 1990s were difficult times for farmer-owned cooperatives, which had to learn the rules of the opening market. He describes how the owner-will of farmers was weak and their ability to steer the firms inadequate and as a result, the boards of the second tier cooperatives were converted into farmers’-majority. Going against the grain of history, our results indicate that locality and, to a certain extent, regional advocacy still have a role in director selection. The results, pertaining to outside stakeholders do not indicate that stakeholders would have influence on the director selection. History of weak farmer-ownership may resonate on present producer cooperatives in such a way that most farmers are critical in nominating external directors to cooperative boards.

Director selection in cooperatives calls for special scrutiny because of the twofold mission of cooperatives: to be financially sustainable (performance) and to defend members’ collective interests (conformance). Most of the present theories (Table ) approach board governance, including director selection, from the rational perspective, while the social perspective remains underrepresented in this scrutiny. It is suggested that director selection should be studied further from the perspectives of (a) the implications of the use of authority and (b) the implications of the administrative culture. We suggest that director selection research within cooperatives should be continued at least in the following contexts: nomination committees, role of the supervisory board, consumer and worker cooperatives as well as tensions and paradoxes across the present board theories.

Table 7. Addition of a new theoretical dimension to director selection

Our results and findings have a few limitations. The results need to be interpreted within the context of the country where the data were gathered, because local contexts may have implications on the results and findings. The number of cases (16) in the series was limited, and the results and findings may hence be prone to biases. Additional research in other countries and contexts would contribute further to the academic scholarship of governance in agricultural cooperatives. Our results should be primarily evaluated in the context of agricultural cooperatives because these cooperatives include specific features in terms of their market environment, policy regulation, and the close interrelationship between the cooperative and the business of its farmer-members. However, all cooperatives share the features of dispersed and collective ownership, democratic decision-making, and the dynamic role of lay members on the BOD. Therefore, this paper may contribute to the initiation of research on other types of cooperatives as well. Finally, we note that the boards of the cooperatives’ subsidiaries were excluded from this study, and hence our results can be only partially applied to hybrid cooperatives with subsidiaries.

7. Conclusions

Current academic scholarship leaves unanswered questions and contains theoretical weaknesses concerning director selection in cooperatives. Neither the mainstream nor the cooperative literature have properly concentrated on the antecedents of board composition, i.e., the selection process. Cornforth (Citation2004) maintained that the corporate theories are too one-dimensional and do not reach the diverse issues in the governance of member-based organizations.

This paper makes four contributions to the scholarship of cooperatives: First, it specifies the mechanisms and relationships inherent in the process of director selection in agricultural cooperatives in a manner that has not been explicitly reported in the current literature. Second, it clarifies the administrative culture as well as the roles and authority of the actors in the process. Third, it discloses paradoxes which help us to understand how agricultural cooperatives approach director selection under the requirement of fulfilling both the performance task and the conformance task. And fourth, it discusses the results against the current board theories by indicating that director selection should be considered not only from the agency perspective but also from the stewardship and specifically from a democratic perspective. Finally, our paper contributes to the mainstream research on board governance by disclosing the tensions between the conformance and performance tasks of the governance bodies.

Further, based on our results we would add a further dimension to the current board theories. Table illustrates this:

Overall, the results constitute a meaningful story that increases our understanding of the processes, roles and paradoxes in the director selection of agricultural cooperatives.

Appendix 1. Key figures of the series sorted by the number of members in 2014.

Appendix 2. Development of turnover in the series 2011-2014.

Appendix 3. Development of the number of members in the series 2011-2014.

Appendix 4. Development of the number of members in the governing bodies in 2011-2014 by sub-groups.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kari Huhtala

Kari Huhtala is director of cooperation at Pellervo Coop Center in Finland. His expertise includes cooperative governance and the cooperative business model. He is a doctoral student at LUT University.

Pasi Tuominen

Pasi Tuominen is a university lecturer at the University of Eastern Finland (UEF). His research focuses on management and governance of co-operatives. He has published in journals such as International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, International Journal of Co-operative Management, Journal of Co-operative Studies and Social Responsibility Journal.

Terhi Tuominen

Terhi Tuominen is a post-doctoral researcher at the LUT University Her research focuses on the strategic management of consumer co-operatives, various forms of entrepreneurship. She has published in journals as International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, International Journal of Co-operative Management, Journal of Co-operative Studies, Social Responsibility Journal and Nordic Journal of Business.

References

- Agyemang-Mintah, P. (2015). The nomination committee and firm performance: An empirical investigation of UK financial institutions during the pre/post financial crisis. Corporate Board: Role, Duties and Composition, 11(3), 176–26. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311485166_The_nomination_committee_and_firm_performance_An_empirical_investigation_of_UK_financial_institutions_during_the_prepost_financial_crisis

- Baltaca, B., & Mavrenko, T. (2009). Financial cooperation as a low-cost tool or effective microfinancing. Journal of Business Management. ISSN 1691-5348, pp. 56-64. https://www.riseba.lv/sites/default/files/inline-files/jbm-2009_0.pdf#page=56

- Bammens, Y., Voordeckers, W., & Van Gils, A. (2011). Boards of directors in family businesses: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal Management Reviews, 13(2), 113–237. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2010.00289.x

- Barraud-Didier, V., Henninger, M., & Akremi, A. (2012). The relationship between members’ trust and participation in the governance of cooperatives: The role of organizational commitment. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 15(1), 1–24. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00695926/

- Bazerman, M., & Schoorman, F. (1983). A limited rationality model of interlocking directorates. Academy of Management Review, 8(2), 206–217. https://journals.aom.org/doi/abs/10.5465/amr.1983.4284723

- Bijman, J., Hanisch, M., & van der Sangen, G. (2014). Shifting control? The changes of internal governance in agricultural co-operatives in the EU. Annals of Public and Co-operative Economics, 85(4), 641–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12055

- Bijman, J., Hendrikse, G., & van Oijen, A. (2013). Accommodating two worlds in one organisation: Changing board models in agricultural cooperatives. Managerial and Decision Economics, 34(3–5), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2584

- Burke, R. (1997). Women on corporate boards of directors: A needed resource. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(9), 909–915. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017987220508

- Cechin, A., Bijman, J., Pascucci, S., Zylbersztajn, D., & Omta, O. (2013). Drivers of pro-active member participation in agricultural cooperatives: Evidence from Brazil. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 4(4), 443–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12023

- Chisholm, W. (1985). Structuring, staffing, and maintaining the board. In E. Mattar & M. Ball (Eds.), Handbook for corporate directors (pp. 24.01–24.06). McGraw-Hill.

- Clune, R., Hermanson, D., Tompkins, J., & Zhongxia, Y. (2014). The nominating committee process: A qualitative examination of board independence and formalization. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(3), 748–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12044

- Cook, M., & Burress, M. (2013). The impact of CEO tenure on cooperative governance. Managerial and Decision Economics, 34(3–5), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2585

- Cornforth, C. (2002). Making sense of co-operative governance: Competing models and tensions. Review of International Co-operation, 95(1), 51–57. http://oro.open.ac.uk/15400/

- Cornforth, C. (2004). The GOVERNANCE of co-operatives and mutual associations: A paradox perspective. Annals of Public and Co-operative Economics, 75(1), 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.2004.00241.x

- Daily, C., Dalton, D., & Cannella, A. (2003). Corporate governance: Decades of dialogue and data. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.10196703

- Deng, W., & Hendrikse, G. (2015). Managerial vision bias and cooperative governance. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 42(5), 797–828. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbv017

- Diaz-Foncea, M., & Marcuello, C. (2013). Entrepreneurs and the context of co-operative organizations: A definition of co-operative entrepreneur. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 30(4), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1267

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

- Eisenhardt, K., & Graebner, M. (2007). Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Academy of Management Journal 2007, Vol. 50, No. 1, 25–32 doi:10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Fama, E., & Jensen, M. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/467037

- Gioia, D., Corley, K., & Hamilton, A. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gioia, D., & Thomas, J. (1996, September). Identity, image, and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during strategic change in academia. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(3), ABI/INFORM Collection p. 370. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393936

- Grant, P., & McGhee, P. (2017). Personal moral values of directors and corporate governance. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-03-2016-0046

- Gui, B. (1991). The economic rationale for the “Third Sector” – Nonprofit and other noncapitalist organizations. Annals of Public and Co-operative Economics, 62(4), 551–572. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8292.1991.tb01367.x

- Hansmann, H. (1996). The ownership of enterprise. ISBN 9780674001718.

- Hansmann, H. (1999). Co-operative firms in theory and practice. Liiketaloudellinen Aikakausikirja, 48(4), 387–403. http://lta.lib.aalto.fi/1999/4/lta_1999_04_a2.pdf

- Henrÿ, H. (2012). Guidelines for Co-operative Legislation third revised edition (3rd ed.). ILO.

- Hillman, A., Cannella, A., & Paetzold, R. (2000). The resource dependence role of corporate directors: Strategic adaptation of board composition in response to environmental change. Journal of Management Studies, 37(2), 235–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00179

- Hoskisson, R., Castleton, M., & Withers, M. (2009). Complementarity in monitoring and bonding: More intense monitoring leads to higher executive compensation. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(2), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2009.39985541

- Huhtala, K., & Tuominen, P. (2016, September 15–16). Election of board members in cooperatives: A review on cooperative governance vis-à-vis corporate governance. Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

- Hung, H. (1998). A typology of the theories of the roles of governing boards. Corporate Governance, 6(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8683.00089

- Huse, M. (2005). Corporate governance: Understanding important contingencies. Corporate Ownership & Control, 2(4), Summer 2005. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv2i4p3

- ICA Coop. (2018). International Cooperative Alliance. https://monitor.coop/sites/default/files/publication-files/wcm2018-web-803416144.pdf

- Johannisson, B., & Huse, M. (2000). Recruiting outside board members in the small family business: An ideological challenge. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 12(4), 353–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620050177958

- Johnson, J., Ellstrand, A., & Daily, C. (1996). Boards of directors: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 22(3), 409–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639602200303

- Kaczmarek, S., Kimino, S., & Pye, A. (2012). Antecedents of board composition: the role of nomination committees. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 20(5), 474–489. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2012.00913.x

- Karhu, S. (1999). Osuuskunnat taas ovat suorastaan afääriyrityksiä. In M. Kuisma, A. Henttinen, S. Karhu, & M. Pohls ( Toim.), Kansantalous. Pellervo ja yhteisen yrittämisen idea 1899–1999 (pp. 243–426). Pellervo-Seura ry.

- Khurana, R., & Pick, K. (2004). The social nature of boards. Brooklyn Law Review, 70, pp. 1259–1285. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/brklr70&div=44&id=&page=

- Kim, Y., & Cannella, A. (2008). Toward a social capital theory of director selection. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16(4), 282–293. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2008.00693.x

- Komulainen, A. (2018). Valloittavat osuuskaupat - päivittäistavarakaupan keskittyminen Suomessa 1879–1938 [Academic thesis]. Akateeminen väitöskirja.

- Kuisma, M., Keskisarja, T., & Siltala, S. (2014). Paperin painajainen: Metsäliitto, metsät ja miljardit Suomen kohtaloissa 1984–2014. Siltala.

- Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2553248

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

- Locke, K., & Golden-Biddle, K. (1997). Constructing opportunities for contribution: Structuring intertextual coherence and “problematizing” in organizational studies. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1023–1062. https://journals.aom.org/doi/abs/10.5465/256926

- Maharaj, R. (2009). Corporate governance decision-making model: How to nominate skilled board members, by addressing the formal and informal systems. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 6(2), 106–126. https://doi.org/10.1057/jdg.2008.27

- Menozzi, A., Urtiaga, M., & Vannoni, D. (2012). Board composition, political connections, and performance in state-owned enterprises. Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(3), 671–698. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtr055

- Michaud, V. (2013). Mediating the paradoxes of organizational governance through numbers. Organizational Studies, 35(1), 75–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613495335

- Monks, R., & Minow, N. (2004). Corporate governance (3rd ed.). Blackwell.

- Murphy, S., & McIntyre, M. (2007). Board of director performance: A group dynamics perspective. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 7(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700710739831

- Muth, M., & Donaldson, L. (1998). Stewardship theory and board structure: A contingency approach. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 6(1), 5–28. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-8683.00076

- O’Neal, D., & Thomas, H. (1995). Director networks/director selection: The board’s strategic role. European Management Journal, 13(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-2373(94)00060-K

- Österberg, P., & Nilsson, J. (2009). Members‘ perception of their participation in the governance of cooperatives: The key to trust and commitment in agricultural cooperatives. Agribusiness, 25(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.20200

- Pearce, J., & Zahra, S. (1992). Board composition from a strategic contingency perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 29(4), 411–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1992.tb00672.x

- Pellervo Coop Center (2019). Website source. https://pellervo.fi/english/cooperation-finland/

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Harper & Row.

- Ramli, R., & Zakaria, H. (2010). A new perspective on board composition and firm performance in an emerging market. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 10(5), 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720701011085607

- Reynolds, B. (2004). Nominating, electing and compensating co-op directors. USDA/Rural Development.

- Ruigrok, W., Peck, S., Tacheva, S., Greve, P., & Hu, Y. (2006). The determinants and effects of board nomination committees. Journal of Management and Governance, 10(2), 119–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-006-0001-3

- Schmeiser, S. (2012). Corporate board dynamics: Directors voting for directors. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 82(2–3), 505–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2012.03.006

- Siltala, S. (2013). Puu-Valion nousu ja uho [Academic Thesis]. Helsingin yliopisto, Humanistinen tiedekunta. Akateeminen väitöskirja.

- Silverman, D. (2006). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. Sage Publications.

- Staatz, J. (1987). The structural characteristics of farmer co-operatives and their behavioral consequences. Co-operative Theory: New Approaches, Citeseer, 18, pp. 33–60. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.667.862&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Trechter, D., King, R., Cobia, D., & Hartell, J. (1997). Case Studies of Executive Compensation in Agricultural Co-operatives. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 19(2), 492–503. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.2307/1349756

- Tricker, B. (2015). Corporate governance: Principles, policies, and practices. Oxford University Press.

- Van Ees, H., & Postma, T. (2004). Dutch boards and governance: A comparative institutional analysis of board roles and member (S)election procedures. International Studies of Management and Organization Issue, 34(2), 90–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2004.11043702

- Westphal, J., & Stern, I. (2006). The other pathway to the boardroom: Interpersonal influence behavior as a substitute for elite credentials and majority status in obtaining board appointments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(2), 169–204. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.51.2.169

- Westphal, J., & Stern, I. (2007). Flattery will get you everywhere (especially if you are a male Caucasian): How ingratiation, boardroom behavior, and demographic minority status affect additional board appointments at U.S. companies. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 267–288. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24634434

- Withers, M., Hillman, A., & Cannella, A. (2012). A multidisciplinary review of the director selection literature. Journal of Management, 38(1), 243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311428671

- Yin, R. (2009). Case study research (4th ed.). Sage.

Appendix 5. Interview scheme.

Describe yourself, your career and your duty in the cooperative.

Your cooperative’s mission and main functions.

The present structure of your cooperative and how it has evolved over the past 10 years.

The BOD election procedure in your cooperative, including nomination. The election procedure of your supervisory board and/or member council.

Emergence of the owner /member will in BOD election in your cooperative.

Official and unofficial discussion of BOD election.

The function and role of the body and its chairman that elects the BOD.

The role of the BOD itself and the CEO in the BOD election process.

The election criteria of BOD members.

The most important stakeholders of your cooperative and their impact on the elections of your cooperative.

Traditions, values and adopted praxis vis-á-vis BOD election.

The discussion culture concerning BOD election in your cooperative.

Conflicts and how they are resolved in issues concerning BOD election. 14. The ideal BOD in your cooperative.

How to develop the BOD election procedure.