Abstract

Women in legal practice in Zimbabwe are subjected to cultural and structural restrictions in the cause of their work. In this context, the paper argues that women are not passive recipients of these challenges but come up with mechanisms to cushion themselves. The paper investigates the strategies employed by women as they negotiate these debilitating factors. Qualitative in-depth interviews were used with 46 participants who included 38 women and 5 men who were both in practice. Furthermore, three key informants were interviewed, one from the Law Society of Zimbabwe (LSZ) and two from the Zimbabwe Women Lawyers Association (ZWLA). The study demonstrates four broad strategies, namely, pulling out, conceding, social investment and going against the tide. Findings suggest that due to socio-cultural and structural constraints, the strategies are overwhelmingly maintaining male hegemonic tendencies and discriminatory practices in law firms. Therefore, there is need for all stakeholders including the professional body, law firm partners, men in practice and spouses to work together if women and men are ever going to have an equal operating environment in the practice of law in Zimbabwe.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

After establishing from my PhD thesis as well as from other scholarly articles that female lawyers are faced with a plethora of institutional and cultural restrictions as they practice law, it was deemed important to unravel their coping mechanisms. Traditionally, the practice of law has been dominated by males. Although females have since made significant in-roads in entering the legal profession, they remain barred from maximising their effort as they trade in the profession. Of interest in this study was the realisation that most of the coping strategies employed by women promote and strengthen the male hegemonic tendencies which have characterised the profession. However, older seasoned practitioners have since started challenging both the structural and economic restrictions placed upon them. It has been noted that there is need for all relevant stakeholders to come together if parity is to be reached in the legal profession in Zimbabwe.

1. Introduction

The legal profession has become increasingly diverse, particularly the increase in the number of women. In England, the percentage of female solicitors has grown tenfold since 1984 while the Bar Council has it that 34% of barristers in 2008 and almost 50% of new entrants were women (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013). Locally, within the Zimbabwean context, Michelson (Citation2013) notes that 30% of practicing lawyers in Zimbabwe are women. On a related note, Stewart (Citation2012) has it that for the year 2012–2013, first-year law students at the University of Zimbabwe were 133. Of these, 62% were women while the remaining 38% were men, clearly indicating that the former has dominated the enrolment of law students in Zimbabwe. Similar trends have also been witnessed in Zimbabwe’s law school enrolments since 2006 due to affirmative action policies which reduced entry requirements for women pursuing tertiary education (Stewart, Citation2012). Affirmative action was meant to address gender imbalance at tertiary institutions which was tilted against women. However, although there has been a surge in the enrolment of women in law schools in recent years, the increase is less reflected on practicing women who remain dominated by men (Michelson, Citation2013; Southworth, Citation2017).

The proportion of women in the previously male-dominated professions is ballooning worldwide (Clerc & Kels, Citation2013; Greed, Citation2000; Raz & Tzruya, Citation2018; Richman & Wood, Citation2011). However, the entrance of women into the workspace has brought new dimensions and dynamics in organisations which include work–life balance (Hlatywayo et al., Citation2014; Mani, Citation2013; Wattis et al., Citation2013), work-place sex segregation (Owoyemi & Olusanya, Citation2014; Schultz, Citation2018), sexual harassment (Buchanan et al., Citation2014; Pateman, Citation2016; Sadruddin, Citation2013). In particular reference to the law profession, women lawyers have been exposed to systemic subordination from the moment they began to enter the profession in significant numbers (Sommerlad, Citation2016).

An extensive body of literature addresses the structural inequalities within the legal profession across a wide range of indicators, including pay, career progression, status and retention with respect to both genders (S. C. Bolton & Muzio, Citation2007; Gorman & Kmec, Citation2009; Sommerlad & Sanderson, Citation2018; Wass & McNabb, Citation2006).

The work-place culture in most law firms is permissive of bullying behavior. This culture cultivates oppression through fear of failure and the consequent unhealthy workplace environment which does not only hinder ethical human interaction but also promotes the disproportionate attrition rate among young women lawyers (Bagust, Citation2014).

Research on women in previously male-dominated professions has been extensively conducted. Studies have demonstrated that even when women are numerically equal or outnumber men, usually in junior levels, professions maintain occupational segregation through the construction of women’s difference (S. Bolton & Muzio, Citation2007). Gender-based discrimination and exclusionary dynamics remain everyday experiences for most women in professions (Bourgeault, Citation2017; Powell & Sang, Citation2015; Saks, Citation2015; Saks & Brock, Citation2017; Stainback et al., Citation2016). Emerging literature has however started to reveal that professional women are challenging the dominance of men and are making inroads in previously male-dominated professions (Msila & Netshitangani, Citation2016; Stainback et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, particularly in Zimbabwe, patriarchy and gendered organisations continuously hamper efforts by women to fully challenge the dominance of men in these professions.

Scholars in Zimbabwe have therefore focused on factors determining the entry of women in surgery (Muchemwa & Erzingatsian, Citation2014), culture and gender on women managers in the hospitality and financial services (Zinyemba, Citation2013), women in distance education management positions (Shava & ebele, Citation2014). There seems to be a dearth of empirical research on the experiences of women in the legal profession in Zimbabwe.

The paper focuses on how women in the practice of law in Zimbabwe negotiate structural and cultural restrictions placed upon them in the course of their work. Using theory and empirical findings, the paper seeks to make some contributions in the fields of gender studies and professions. Empirically, it shows how women in the practice of law engage with organisational structures, particularly those which directly or indirectly impinge on their work. Further, the paper contributes on how practising women negotiate socio-culturally imposed limitations on their careers. In doing this, the paper identifies four, not mutually exclusive broad categories of strategies, namely, pulling out, conceding, social investment and going against the tide.

The article is divided into six sections, First, the nature of work in the legal practice is expanded and draws on a range of scholars focusing on different issues such as working hours, work-role stressors and gendered organisations. Secondly, the article provides a more focused discussion on women in the legal profession from a global perspective. The paper continues to look at gender roles in traditional Zimbabwean culture as these are considered generally important in decisions made by practising women. A section is devoted on work-to-nonwork conflict and its effects along gender lines. In the sixth section, focus is on findings and discussion before finally, providing conclusive remarks.

2. Nature of work in legal practice

Literature on legal practice is dominated with reports of practitioners working from dawn to midnight for days (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999; Sommerlad, Citation2016; Tremblay & Wu, Citation2016). The number of hours worked in a week has been identified as one of the characteristics of law practice and it also relates to work-to-nonwork conflict. Practitioners frequently work in the evenings and weekends, often resulting in one working between 50 and 60 hours a week (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999). It is therefore generally expected that lawyers experience significant conflict between their work and nonwork spheres. This conflict, as explained in the next section contributes to work-role stressors.

Work-role stressors involve chronic pressures contributing to lawyers’ feelings of resentment and a sense that work is invading their non-work life (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999). Individuals who occupy work roles that are perceived to be demanding or conflicting experience negative emotions that spill-over into their personal lives, thus creating tensions between the work and non-work domains (Azmat & Ferrer, Citation2017; Choroszewicz, Citation2016). Of interest are two role stressors which received significant attention of researchers, overload (Greenglass & Burke, Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2016; Mansour & Tremblay, Citation2016) and profit-driven focus (Kickbusch et al., Citation2016; Schnall et al., Citation2018).

Although practitioners work long hours, they still have inadequate time to do their work (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999; Sommerlad, Citation2016), reflecting the work overload nature of practice. Work overload refers to the extent to which the amount of performance required in a job is excessive (Kavitha, Citation2017). Among other issues, it is characterised by perceived time pressures and deadlines, exorbitant work demands and informational overload (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999). Research has singled out work overload as one of the most important factors determining whether work conflicts with one’s nonwork life (Deery & Jago, Citation2015; Omar et al., Citation2015).

Profit-driven focus reflects an occupation form of role conflict that specifically relates to lawyers in practice (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999). There is a growing concern in the practice of law about the increasing profit-driven focus. Law practice has become the business of law as the profession has become more commercial and profit oriented, operating more like a business. The profession has since shifted away from a focus of helping clients as a service profession with collegial relations among legal practitioners, to an emphasis on competition among lawyers, maximising billing of clients and making profits. Profit-driven focus, as an occupation-specific form of role conflict, contribute to work-to-nonwork conflict (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999; Schnall et al., Citation2018).

In the context of profits driven focus, married professional women are simultaneously making efforts to meet their marital and family responsibilities, at the same time working in a demanding career. Therefore, work-role stressors have stronger effects on their work-to-nonwork conflict than for men (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999).

Profit-driven focus context in which legal practice operates relates to the increased number of hours professionals end up working. Law firms, according to J. E. Wallace (Citation1999) are known for exerting excessive demands on their practitioners, not only compared to other professionals, but also compared to lawyers working in other realms such as commerce and government (Nelson & Nelson, Citation1988). The immediate implication is that lawyers in practice experience more work-to-nonwork conflict than lawyers working in other settings. Women in practice are not only persecuted by work-to-nonwork conflict, but also by the gendered nature of many law firms (Acker, Citation1990; Stainback et al., Citation2016; Williams, Citation2018).

Gendered organisations are problematic for women in employment. Work policies, interpersonal networks and embedded attitudes in some organisations draw mainly from the life experience of the traditional male-breadwinner concept, thereby creating an unequal playing field, promoting the interests of men and the patriarchal values that it represents (Acker, Citation1990; Bilen-Green et al., Citation2008; Gorman & Kmec, Citation2009; Shava & n.d.ebele, Citation2014; Stainback et al., Citation2016).

3. Work-to-nonwork conflict in the legal profession

Work in practice invades one’s non-work life and is more pronounced to women than men where it has serious repercussions for the former on their careers, leading to high unemployment and the rate of attrition for women than men (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999). Greenhaus et al. (Citation1997) argue that women in professions experience greater work-to-nonwork conflict than men because of the value they attach to being successful both in their career and wife/mother roles. Women frequently leave practice due to time-related demands, lack of flexibility and child care responsibilities (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999; Seemann et al., Citation2016; Williams, Citation2018). It is, however, important to note that not all women leave practice.

Those who stay, particularly those integrating their full-time professional careers with marriage and family indicate challenges in coping with a double load involving the “second shift” (Hochschild & Machung, Citation2012, p. 33). After the formal workday, women engage in traditional family and caring responsibilities (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999; Shava & n.d.ebele, Citation2014; Zinyemba, Citation2013). DePasquale et al. (Citation2017) present similar arguments by highlighting that women usually feel that work is imposing on and conflicting with their family obligations more than their male counterparts.

Typically, work-nonwork conflict has been examined in terms of two components, time-based and strain-based (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999). Time-based conflict is the degree to which the time pressures associated with a role, in this case, work, invade the time meant or associated with another role (Greenhaus, Citation1988). Bartolomé and Evans (Citation1979) view strain-based conflict as the extent to which an individual is preoccupied with one role as they attempt to meet the demands of the other. This, as noted by Bartolomé and Evans (Citation1979) is reflected through a preoccupation with work after one would have left their respective workplace, signalling emotional and psychological strain of work-to-nonwork. The conflict has effects on the physical and psychological energy available for other non-work-related duties (Voydanoff, Citation1988).

Concerning priorities, married professional women have a tendency of placing emphasis on both their work and family roles, while married professional men dedicate more time to their work and less to their home and family responsibilities (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999). Men interpret working long hours in a demanding job as part of the good provider role and is thus considered as the primary way in which they contribute to their families (Gutek et al., Citation1991). On the other hand, professionally demanding careers for women may make them feel as if they are neglecting marital and/or family roles (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999). They may feel that work is imposing on their obligation outside of work to an extend that they become more sensitive to the demands of their paid work. There are however cultural dynamics on this issue as noted by (Zinyemba, Citation2013), particularly concerning women.

Cultural context plays a pivotal role in the perceptions of women about work and family balance (Thein et al., Citation2010). In a study comparing Chinese and American women, the Chinese argued that sacrificing family time for work signifies a self-sacrifice for the family whereas in the latter, sacrificing family life for work is viewed as failure to care for the family (Thein et al., Citation2010). Therefore, long working hours would not pose significant challenges for the Chinese women as it would to American women.

Legal practitioners, particularly women, make an effort to balance work and family demands through a selection of their work setting (Sommerlad, Citation2016), for example, women, more than men report that they avoid or leave practice because they want to trade their professions in government or commerce where they are more likely to achieve a healthy balance between work and nonwork demands (Pringle et al., Citation2017). The next section focuses on gender traditional roles viewed using Zimbabwean lenses.

4. Patriarchy and gender traditional roles in Zimbabwe

Patriarchy is a social system where men appropriate all social roles and keep women in subordinate positions (Kambarami, Citation2006). Traditionally, Zimbabwe is a patriarchal society where women have always been subdued under men (Chuma & Ncube, Citation2010; Zinyemba, Citation2013). Within this discourse, radical feminists argue that culture imprisons women, resulting in their subordination (Kambarami, Citation2006; Wadesango et al., Citation2011).

Patriarchy is bred through the socialisation process, which begins in the family and it infiltrates into the sectors of the society such as religion, education, economy, politics (Kambarami, Citation2006) and in corporate organisations (Adisa et al., Citation2019). The young are socialised to accept sexuality differences as patriarchal practices start to take shape through the family. In the Zimbabwean culture, the socialisation process differentiates the boy child from the girl child from a tender age. Culturally, Zimbabwean males view themselves as breadwinners and heads of households whilst females are taught to be obedient and submissive housekeepers (Kambarami, Citation2006). The reason behind such differentiation and discrimination is that society views women as sexual beings, not as human beings (Charvet, Citation1982). Furthermore, women are not only constantly defined in relation to men but are also frequently defined as subordinate and dependant to men. Resultantly, women are socialised to acquire qualities which fit them into a relationship of dependence on men. The qualities include gentleness, submission, passivity and always striving to please men (Diehl & Dzubinski, Citation2016; Pringle, Citation1992).

The Zimbabwean culture emphasises that once a girl reaches puberty, all teachings should be directed towards pleasing one’s future husband and being a gentle, obedient wife (Wadesango et al., Citation2011). The girl-child’s sexuality is further defined for her as she is taught how to use it to benefit men. These cultural teachings foster a dependence syndrome on women (Kambarami, Citation2006). Although the socialisation process which instils patriarchal practices into the young starts in the family, it does not end there, it penetrates other social institutions, among them, marriage as highlighted in the next paragraph.

Within the Zimbabwean setup, marriage is the desired destination for most women (Chireshe & Chireshe, Citation2010). What seems to fuel patriarchy in marriage is the payment of lobola also identified as bride wealth or bride price Chabata (Citation2012), which in most cases relegate women to subordinate positions at the same time, giving men all rights over the former. As a result, bride price, which is part of the patriarchal nature of the Zimbabwean society breeds gender inequality (Chiweshe, Citation2016; Kambarami, Citation2006). Inequality is also reflected on the importance of taking care of their husbands, providing catering services and respecting their position in the household which is placed on women in marriage. Furthermore, Zimbabwean culture suggests strong cultural stereotypes of men as providers of food, shelter and clothing for the family and women as nurturers who take care of the cooking, cleaning and domestic duties (Montgomery et al., Citation2012).

5. Coping with gender-related challenges in organisations

Literature has established that professional women in organisations are not passive recipients of the organisational environment they operate. They put in place mechanisms to cushion themselves against gender-related challenges.

In a study on minority legal practitioners in big law firms in the United Kingdom, Tomlinson et al. (Citation2013) established that some women use assimilation strategies. These strategies encompass the display of behaviour patterns and traits that show conformity with the dominant white masculine culture. Similarly, minority groups may benefit from assimilation in the US where they engage in such strategies as improving academic performance and social mobility (Greenman & Xie, Citation2006). For young minority professionals, not looking “too ethnic” is of value given that some cultural practices are frequently regarded as unrefined (Archer, Citation2011, p. 147). Tomlinson et al. (Citation2013) also note that assimilation can be adopted through such behaviours as incorporating Western patterns of self-presentation, avoiding involvement in minority group networks and taking up the hobbies and dress code of the dominant group. Other assimilation strategies include underplaying the visibility and impact of family life, returning to work quickly after maternity, and embracing stereotypically masculine career trajectories, that is, effectively managing like a man (Wajcman, Citation2013).

Another strategy used by minorities including women in practice is compromising (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013). This relates to issues associated with work–life balance and is said to be more pronounced to practitioners with children or in a family setup. Women sacrifice a lot to strike a balance between family and work demands (Crompton & Harris, Citation1999; Tomlinson, Citation2006). Tomlinson et al. (Citation2013, p. 258) called this behaviour “satisficing”. For women in legal practice, compromises involve re-evaluating conflicting and competing priorities. Of interest is the aspect of maternity which has seen some women postponing pregnancy and at times marriage until attaining established careers (Kanwar et al., Citation2013; Shava & n.d.ebele, Citation2014). Even when they go for maternity leave, these women have a tendency of returning to work quickly (Sommerlad, Citation2016; Tomlinson et al., Citation2013).

Women in practice may also engage in playing the game strategies (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013). These entail overcoming or maximizing on the structural and cultural barriers within the profession. Women employing this strategy develop techniques to overcome one’s difference, or better still, make the difference count in their favour. Performing and proving one’s value is a characteristic of playing the game. Carbado and Gulati (Citation1999, p. 1260) named this activity “effort signaling strategies”. Although this strategy cuts across gender, there are some categories of people in a firm, particularly the minority who are under more scrutiny; hence, the need to prove themselves is higher. Furthermore, gaining exposure, visibility and to be identified as someone who performs well under pressure is also considered advantageous (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013).

Reforming the system is another strategy employed by women. This entails attempts to reform the profession, particularly practice, and is more common with senior members or those who would have reached the partnership level (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013). Women at this level have witnessed the structural inequalities within the profession, at the same time, they have gained enough status and power to challenge these. Senior women use their status and power to challenge the existing unfair policies and practices against minorities such as women.

In response to challenges in legal practice, some women relocate. This strategy entails one leaving practice, and seeking alternative employment opportunities that are more conducive to family life (Bagust, Citation2014; Kay et al., Citation2016). However, relocation may take the form of one leaving one firm and joining another one with policies that match with one’s attributes, for example, a woman of an African origin leaving a white-dominated firm where racial discrimination is rife and joining a firm where the majority are blacks (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013).

6. Methods

This section focuses on the methodological aspects which were used. Due to the social nature of the study and the desire to understand human experience, interpretivist paradigm was used. Different women in the practice of law subjectively experience and respond to their work environment, thus acknowledging the multiple realities concept which is a fundamental characterisitc of this paradigm (Packard, Citation2017). Interpretivists seek to understand the world of human experience (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017; Iofrida et al., Citation2018; Packard, Citation2017). Reality is socially constructed in interpretivist paradigm (Iofrida et al., Citation2018; Kivunja & Kuyini, Citation2017). The researcher, therefore, makes meaning of their data through their personal thinking and cognitive processing of data and this is informed by their interaction with participants.

In line with interpretivism, a qualitative approach was adopted due to its unique characteristics which proved advantageous to this research. As noted by Mouton and Babbie (Citation2001), qualitative research considers the insider perspective. In this case, insiders are women in the legal profession operating in a restrictive environment.

Meanings of action in a social context are at the center of qualitative studies (Coolican, Citation2017; Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017; Matthews & Ross, Citation2014; Walliman, Citation2017). The assumption was behaviours of women in practice could not be detached from the challenges they face in the profession. The constraining environment was argued a significant determinant of behaviours of women in practice. Therefore, it was important to have an in-depth understanding on the meaning of these behaviours within a specific context, an aspect which could not be addressed by quantitative methodology. In relation to this, researchers are interested in people, their experiences and perceptions of the world around them (Coolican, Citation2017; Iofrida et al., Citation2018). The study sought to understand women in practice within their context and how they interpret and respond to institutional and social constraints in the profession.

Forty-six participants (see Table ) were purposively selected and interviewed using four different interview guides, each tailored to suit the respective category of participants.

Table 1. Categories of participants

Data were analysed using thematic analysis (TA), guided by the process of open, axial and selective coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). As argued by Braun et al. (Citation2019), TA entails systematically identifying, organising and offering insight into patterns of meaning in a data set. Analysis of data began with a thorough reading and re-reading of the transcribed interview scripts. These were read in conjunction with brief notes which had been noted down during each interview session. The idea behind was to address the aspect of critical distance. The researcher played several roles in the research process; of concern are the roles of designer and evaluator. Continuously engaging with data maintained some level of critical distance (Charmaz, Citation2014; Corbin et al., Citation2014). As noted by Cassell et al. (Citation2018), critical distance is necessary for one to remain detached and objective in the research process. Furthermore, continually engaging with data allowed the researcher to develop some form of relationship and familiarity with the text (Terre Blanche et al., Citation2006). During the reading of each interview, notes were made in the left-hand margin on the transcriptions. This was done to identify and describe discourses in the text. Atlas TI version 8 was also utilised in arranging the themes. Atlas TI is a qualitative data analysis software.

7. Findings and discussion

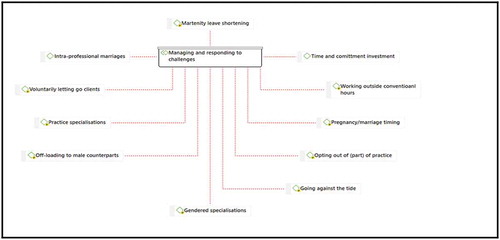

As highlighted in previous studies (Carbado & Gulati, Citation1999; Mickel & Dallimore, Citation2009; Tomlinson et al., Citation2013), participants developed strategies to respond to and manage the challenges they are confronted with within the practice of law. Strategies were identified, ranging from compromising on leave days, engaging in “gendered” specialisations, informally “embracing men” in practice for their convenience while more radical respondents spoke about their efforts to reform structures and practices within practice. These strategies are however not mutually exclusive as individuals engage in different strategies over time and at different times simultaneously. Figure depicts the strategies employed by women in legal practice in Zimbabwe in response to the challenges they face in the execution of their professional mandate.

A link is found between one’s biographical narratives and the strategies used. For instance, recently qualified young women lawyers engaged in more projective, future focused strategies such as postponing marriage and childbearing as they enter practice with the aim of establishing their careers. Compromise was more pronounced in slightly older respondents who are faced with the challenge of reconciling professional and private life. Furthermore, more experienced participants, usually at partnership level had the opportunity and ability to challenge and reform existing practices and structures. Biographical narratives were therefore important in establishing the point at which different strategies were adopted.

Following is a discussion of strategies adopted by women in practice as they try to adjust and manage the challenges they face in the execution of their work. They are broadly divided into four, namely pulling out, conceding, social investments and going against the tide, each having its own sub-strategies.

7.1. Pulling out

As acknowledged in previous studies, women in previously male-dominated professions in general and legal practice, in particular, have cited giving up as one of the strategies (Powell & Sang, Citation2015; Ross & Godwin, Citation2016). Two types of giving up emerged from this study. First, quitting and moving out of practice and second, quitting some areas of specialisation but remaining in practice. Pertaining completely leaving practice, Ednah, a 34-year-old married executive with ZWLA and has been in the profession for 12 years commented on this: “ … the majority of them leave practice and instead go to become company secretaries, legal advisors in banks, for clients … where the environment can be more conducive, they can balance work and home”.

This concurs with existing literature (Long, Citation2016; Sterling & Reichman, Citation2016) that attrition for women is high in practice. Cited both in literature (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999; Powell & Sang, Citation2015) and in the study as the main reason is the unfriendliness of practice as it fails to respond to gender demands, particularly of women. Quitting practice was argued to be common about 2 years after marriage, especially when the woman starts bearing children, making it difficult to balance professional and family demands. Similar predictions also argued that women bore the bulk burden of household duties such as caring responsibilities, leaving them with less time for professional commitment (DePasquale et al., Citation2017; Whatmore, Citation2016). In line with the findings, Azmat and Ferrer (Citation2017) note that women in practice face difficulties in meeting the competing professional and family demands, leading to their withdrawal. Furthermore, Brenda, a 28-year-old single woman reflected on her concerns about her aspired future and the way women in practice are treated;

The second I am married, and I have kids … I am out of practice … At the end of the day we are women, regardless of one’s profession. You know, we might be bright, we might do the work often, be fantastic, but there is just not enough leeway being made so that women can navigate practice and family …

Some women in practice even before they get married, they are already planning their exit from the practice as they realise the difficulties associated with balancing work and family demands. As presented below, whilst others leave practice completely, some deliberately leave parts of practice as they adjust.

Practice is composed of different specialisations depending on the nature of cases being handled. Cases are categorised into, for instance, civil, criminal and commercial. Criminal cases, according to most participants, are tedious, requires high levels of social capital in terms of social connections and in most cases, corruption is rife in these cases, forcing legal practitioners to be prepared to and ready to invest accordingly. The remaining two types of cases, particularly civil have been argued to be relatively simple, less hectic and requiring less social capital. Some women deliberately shun criminal cases for civil and commercial cases. The gendered nature of cases in the practice of law is clearly articulated by Maud, a 32-year-old married, mother of one and has been in practice for 4 years when she says;

You will find that, that is why we have a large number of male lawyers taking on criminal cases because of these reasons that we have been discussing and a large number of us female lawyers taking on the civil ones, because the civil ones is … sort of tamed. It is dealt with during the day

As noted above, civil cases also provide women an opportunity to balance professional and family demands as these cases are usually dealt with during normal working hours. This strategy is most common to married women with children who are unwilling to leave practice at the same time, not being comfortable with some specialisations due to their nature which may compromise their family demands. The practice of law, and in particular, the criminal specialisation requires long, unpredictable hours (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013) and may be incompatible with family responsibilities imposed on women by patriarchy. However, unlike previous studies, most participants who settled for civil cases only indicated that they were willing to quit practice if opportunities were to open in commerce and industry. Therefore, what makes some women stay in practice is the economic decline, meaning fewer opportunities for employment outside practice unlike in more stable economies were most researches were conducted.

7.2. Conceding

Some women were found to be using conceding strategies. In this study, these strategies entail a scenario whereby a woman in practice consciously decides to forgo or postpone an individually and/or socially valued aspect. As seen below, conceding takes place in three distinct ways which are, voluntarily letting go off clients, postponing marriage or childbearing and compromising maternity leave.

Some participants argued to be using or once used the strategy of letting go off clients. The strategy often related to work–life balance and was mostly relevant to respondents who had children, and, in some cases, who were married as well. Letting off clients was common in situations where time for work assignments clashed with the typical family time, for instance, clients who would seek legal assistance after hours. Although responding positively would mean more income, women, particularly married and with children forfeited such clients. Brenda, a 35-year-old, married and a mother of two with 9 years of experience commented on this: “You are at home, you got your husband and the children. To explain to your husband that I have a client who has been arrested at 23:00hrs or midnight, it puzzles him. So, you grow into ignoring”.

Literature shows how women make sacrifice to satisfy both work and family demands (J. E. Wallace, Citation2004, Citation2006; Nelson & Nelson, Citation1988). Two possible reasons make the Zimbabwean scenario unique from the previous studies, particularly those conducted in the global north. First, marriage is generally highly valued in Zimbabwe and its cultural values are still socially upheld (Chireshe & Chireshe, Citation2010). The study has revealed that married women are generally less prepared to sacrifice their marriages for professional duties. Second, Zimbabwe still remains a patriarchal society where females generally assume subordinate roles even in marriages (Kambarami, Citation2006; Wadesango et al., Citation2011). As noted by some participants, they need permission from their husbands to attend to clients during non-working hours. Similarly, some indicated that to avoid unnecessary hustles, they will just let go off clients in need of assistance during non-working hours. Furthermore, most of the cases which were reported to be declined by married women were of a criminal nature. These are characterised by unpredictable times which may interfere with family time. As noted by Greenhaus et al. (Citation1997), time-based conflict is more pronounced in women than men due to patriarchy which burdens the former with family responsibilities, thus causing them to decline some cases as witnessed in this study. Letting go off clients is induced by restrictive marital setups, prompting some women to postpone marriage and/or childbearing as seen in the next paragraphs.

Although marriage is highly valued in Zimbabwe (Chabaya et al., Citation2009; Kambarami, Citation2006), some women in practice have resorted to postpone marriage or childbearing as they try to cushion themselves from the challenges they face. This strategy was raised by four participants with Brenda having to narrate her priorities and possible family-related challenges that may pose some challenges to her career:

My career first, everything follows. I cannot have kids now because if I have children now, I have to look after these children. You know, then you have a husband that you have to look after. He is not going to understand that my wife is a lawyer, because he is my wife, he is married to a wife not a lawyer. He sees you as a wife, not as a lawyer.

Previous studies (Beck-Gernsheim, Citation2002; Kanwar et al., Citation2013; Peng, Citation2017) saw some women in the global north completely cancelling marriage, and in some instances, child-bearing, in pursuit of their careers. However, in this study, no participant revealed cancelling marriage or childbearing altogether, rather, they indicated postponing, thus confirming the value attached on marriage alluded to earlier on.

Childbearing in formal employment circles, particularly for women, entails maternity leave and some participants reported that they either forfeit it completely or just take part of it. Some narrated how their colleagues in practice negotiated this leave. In Zimbabwe, according to the Labour Act Chapter 28:01, maternity leave is 98 days. The nature of practice in many contemporary firms is profit driven (J. E. Wallace, Citation1999; Schnall et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, in Zimbabwe, due to a declining economy, some firms cunningly maximise on the profit-driven aspect by paying practitioners on commission. As seen in the study, some firms, particularly those emerging may even fail to fully pay someone on maternity leave. The common adage, “we eat what we kill” may work against women on maternity leave, particularly those paid on commission or those who risk no payment at all, forcing them to come up with strategies to balance the leave and employment demands as seen below.

Some participants noted that due to economic pressures, they cut-short their maternity leave. This was common to practitioners who were paid on commission and those who were on basic but unpaid whilst on maternity leave. Juliet, a 38-year-old woman, with a single child and having been in the profession for 7 years highlights; “… but at times, you will have to … you will find yourself compromising and you just need to come back because you need the money …”.

Furthermore, Ednah added her voice to the debate;

The way law firms are configured is around, are you able to meet targets to generate a certain amount to be paid and so the law firm itself would be saying, oh, look, if you take three months away on maternity leave, it is at your own cost, it is not like we are going to give you a salary because we are not meeting targets because of your absence.

Therefore, one is not directly forced to report for work when they are on maternity leave, rather the nature of practice, exacerbated by the declining economy sees some women compromising their leave.

In some instances, women on maternity leave are directly asked to continue with their cases. Brian, a 28-year-old man with 3 years in the profession alluded to this by saying.

… it is the partners who end up saying you have to squeeze, even if you are on leave, if you attended … one or two cases. So, you will find that if you are a woman … you could be coming to court probably on Tuesday and Thursday.

Unlike the previously mentioned techniques of handling maternity leave challenges, this technique entails taking a leave in full but is punctuated with episodes of reporting at work, taking instructions and representing clients in court as and when necessary. A similar trend is also popular, not only with juniors, but with partners as well. Participants shed light on the reduced ability of women partners in taking their leave. Jean, a 46-year-old divorced woman, partner, mother of two with 22 years of experience narrates how her position as a partner pressurised her to compromise her maternity leave on her first pregnancy;

… I had to get into the office and deal with the clients because, you see, at that point, I was a partner then, so, it is your practice and you want to promote it, so who do you expect to work for you in your absence … you cannot fold your hands saying I am on maternity leave, you just have to work.

Similarly, Primrose, a 26-year-old single woman with 3 years in practice reflects on an event she witnessed from her superior, a woman partner;

… I would give you an example, my boss, she is a partner in the firm, she had a meeting on the day she gave birth … because she is the partner, she is the rain-maker and some people come here because they want to see her directly … So, if she could not have made herself available, we would have lost business.

Therefore, concerning maternity leave, both legal assistants and partners are affected. Unlike previous studies, where women compromise their maternity leave to show professional commitment, and hence improving chances of promotion (Sommerlad, Citation2016; Tomlinson et al., Citation2013) and to act like men (Wajcman, Citation2013), the Zimbabwean experience of the same is driven by economic needs due to a precarious economic environment. Practitioners, including women face economic challenges and take advantage of possible situations to make money; hence, they may be prepared to compromise their maternity leave. Some participants indicated that to deal with the challenges, they establish strong informal ties with men and other women in their firms who will rescue them when they are incapacitated as outlined in the next section.

7.3. Social investment strategies

Contrary to previous studies, one strategy that emerged is socially investing in relationships with colleagues. Some participants revealed that when called to attend to a client outside the normal working hours, they depend on their male counterparts to rescue them or in some cases, their unmarried women colleagues. This is common to married women with children as noted by Tamuka, a 30-year-old married man who has been in practice for 5 years:

The alternative arrangement could be for instance, a lady lawyer at 2300hrs perhaps because of her safety and social restrictions, she can’t move out of her place to go and attend to a client, she can ring a colleague and say Mr. so and so, can you attend … Mr. so and so is detained, may you kindly assist him and then I will take over tomorrow …

This strategy is common amongst married women with children as they respond to criminal cases, which may be unpredictable in terms of timing and may compromise on family time. Patriarchy and its male dominance (Chuma & Ncube, Citation2010; Zinyemba, Citation2013) is seen as women are reluctant to leave their households without the husbands’ permission who may deny them.

Contrary to the already discussed scenario whereby some married women completely discard criminal cases, particularly those that come during family time, this technique allows women to keep their clients but will seek help during moments they perceive themselves as socially incapacitated. They reclaim their clients, as acknowledged by Tamuka above where he argues that women may ask for assistance from men in the profession when a case arises during unfriendly hours, only to reclaim the case the following morning, during normal working hours. This technique is premised on efforts to negotiate patriarchy (Wadesango et al., Citation2011; Zinyemba, Citation2013) as employed women try to balance both family and professional demands This technique is also not represented in the legal practice literature. Whilst some married women with children get help from fellow professionals as they try to negotiate their challenges, some respond by marrying professional mates as outlined below.

To circumvent the challenges brought about by spousal restrictions, women in practice may marry fellow practitioners. Polite, a 28-year-old married woman, a mother of two children, with 3 years experience sheds more light;

… it would have been difficult had I been married to someone who is not in the profession, who really doesn’t understand possibly the implications … He understands what I mean when I say I am busy, because he is from within … So, that is the one advantage that I can say, possibly marrying someone from the same profession.

Similarly, Brian emphasises the advantages of women marrying fellow practitioners; “ … so, you would notice that probably, if the husband is a lawyer … but if the husband is in another profession, it would actually be a challenge …”.

The assumption is that men in practice understand the dynamics and nature of practice more than outsiders. Areas argued to be causing mayhem in marriages include working and attending to clients outside normal working hours, particularly late evenings, early morning and weekends. One is therefore likely to be understood with a spouse in practice on such matters. This is silent in the current literature on how women in practice deal with their challenges. Most likely, the reason being that most studies were conducted in the global north where women are comparatively more empowered than those in the global south, and thus, effects of patriarchy are more limited in the world of the former than the latter.

A similar social investment technique has been for women to deal with all the paperwork associated with a case and then hand over a case to a male counterpart or at times, to a more seasoned woman practitioner who will then appear in court. Brian sheds light;

… she will work with the paperwork, and then it goes with someone else who goes to court … There are some female lawyers whom you really do not know, but then when you take a close look, they are the once doing the actually work …

This has not been part of the existing literature. Avoidance of court appearance is attributed to the perceived unfriendly environment, especially to novice junior women in practice. In that regard, Brenda had to say:

… because you are a woman … it is charactierised by a lot of sexist comments whereby they try and bully you and intimidate you, like, what are you doing here, do you know about the ins and outs of court, you are a woman, at your age, shouldn’t you be at home with children?

To circumvent such challenges, some women, particularly, young and emerging professionals split the work between themselves and other legal practitioners with the former doing the paperwork and the latter, court representation. Although most of the techniques entail women in practice adjusting to the dominance of men, some resist this as outlined below.

7.4. Going against the tide strategies

These strategies make a shift from the old “woman-as-victim” narratives by exposing some resistance techniques that women employ in the face of challenges. Most of the strategies employed by women in practice reproduce and naturalise gender inequality. In contrast, some women recognise and resist male dominance and gendered organisations through a range of actions. These include being strict but polite in one’s approach, resisting gender-related and non-legal duties, resisting any decision that undervalues women and generally going an extra mile in commitment and deliverables. These are discussed in the following paragraphs.

To deal with possible gender-related abuses and degradation, some participants make sure they are strict and professional in their approach to work. Brenda narrates how she uses this to mitigate her challenges;

You are not respected as a woman, whether or not you have a masters degree, ten doctorate degrees … you become almost hard. You tell them, I am here for business … no room for pleasantries because the second I am friendly, and I say look, Mr. so and so, it is a pleasure to meet you, they take advantage of that … by nature, I want to smile … to be friendly to people, and the second I do that, I don’t know if it is viewed as weakness, you will see people start to take advantage.

There is a need to create a professional social distance between themselves and others such as male workmates and clients, thus leaving less room for aspects such as sexual harassment.

Resisting gender-related duties at the workplace such as making tea is another strategy used by women. Ndaizivei, a 33-year-old woman partner, a mother of one and 11 years in practice spoke of how she refuses duties that are not in line with practice;

… and also very bold to draw boundaries which is a very worrying step because you might worry about losing your job, but either you sign up to stomaching unfair treatment or you take the bold step and set out your boundaries and say, I don’t think this is part of my scope, or no, I did this yesterday, I did this the day before yesterday, somebody else has to do it. Why don’t you do it, why don’t you assign somebody else to do it … there is nothing biological about these administrative duties, anyone can do it. In effect, as a rule, I do not pour teas here, everybody knows that I do not pour teas, even for clients. When the tray comes, I tell them they are free to pour … because I do not want to reinforce it in their heads that they can ask me in the middle of the meeting to go and collect some water or something like that. I also don’t take minutes in meetings. I just don’t, I listen, and I engage … I make it very clear; I hope you have somebody taking minutes because I don’t take minutes. I don’t say it in a nasty way, I just say, I don’t take minutes.

This minimises possibilities of unfair treatment on women which promotes male hegemonic tendencies in firms. As revealed above, although it is a good move, one risks losing their job as they are perceived as rebellious by challenging the system that sustains the dominance of men.

To cushion themselves, women may also challenge illegalities that characterise practice such as the denial explicitly or implicitly of maternity leave, at times in Zimbabwe, under the guise of economic hardships. Concerning this, Ndaizivei gives an account of what happened to her as she was the first woman to go on maternity leave and come back at her firm;

… so, nobody knew what to do and I had to kind of fight my way and say, if I weren’t a female, or if were, for example, a receptionist, you were going to pay me my full salaries, you were not going to deduct something and say, because she wasn’t at work. So, why are you expecting me to have been productive in those four months?

According to previous researchers (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013), some women successfully challenge the unfair and illegal treatment being practiced in some law firms. Also, as witnessed in this study, this is mostly undertaken by senior members in practice who are more established.

As asserted by Tomlinson et al. (Citation2013) and Wajcman (Citation2013), putting more effort and hours to match the perceived performance of men has been cited as one of the strategies employed by some women in this study. Furthermore, women have shown strength and resilience when they want to make it in practice as noted by Jodlea, a 30-year-old single woman who relocated to the corporate world after having spent 4 years in practice; “… that you continuously have to prove yourself to people and work twice as hard as anybody else … yes, to prove yourself, while others just, you know, naturally have it on a silver platter by virtue of them being males”. Similarly, Primrose notes that;

So, you have to go prepared, even if it means putting a little more work, than usual, and that is how I end up putting long hours, twelve hours or so. But, yes, you just have to be prepared, you have to stand your ground and you have to work hard.

Strategies associated with going against the tide were common with women who had on average, more than 8 years in practice and those who were at partnership level. Possibly, it could be that they had moved up the organisational ladder and had learned much, to the extent that they cannot be pushed away easily. Furthermore, they command a significant amount of respect from peers, even men.

8. Conclusion

The paper explored ways through which women in practice in Zimbabwe negotiate structural and cultural restrictions placed upon them. It argued that women are not passive recipients of the systematic discrimination levelled against them, they come up with ways and mechanisms to cushion themselves.

The major conclusion is that women in practice adopt several strategies to deal with their challenges. The strategies address limitations placed upon women emanating from domestic and professional spheres. However, most of them reproduce the systems, practices and structures currently in existence instead of transforming them. Generally, women have adjusted by embracing the systems, practices and structures working against them. The acceptance is necessitated by the poor economic performance as those who challenge the status quo risk losing employment which has become so difficult to secure. Findings of this study suggest that due to socio-cultural dictates, the way practice is organised and the gendered nature of most law firms, women in practice, particularly young new entrants engage in practices that subdue them under men. There is, therefore, need for other relevant stakeholders to come on board to partner with women in practice to overcome the barriers. Although most strategies reproduce the status quo, some women, particularly seasoned practitioners and partners challenge the subordination and restrictions imposed on women. Their power rests on the seniority positions and number of years in the profession.

The fight against discriminatory practices is slow and less effective because it is left to women alone. Men should realise and accept the effects of their conscious and unconscious hegemonic tendencies on women and by so doing publicly denounce it, at the same time embracing and accepting the presence of women in the profession as equals. Acceptance must also go beyond the professional space into the domestic space where men must recognise the nature and requirements of practice. Developments of this nature at family level will provide space for women not only to enter practice and excel, but also significantly expand their horizons into male-dominated specialisations. The Law Society of Zimbabwe should also be actively involved in making practice gender neutral by conducting workshops and awareness campaigns to that effect. As a professional body, it is important to take the leading role in challenging and breaking down the barriers that affect women in practice. Gender friendly related policies to be used by law firms must be spearheaded and enforced by the professional body if gender equality is to be realised in practice in Zimbabwe. In simpler terms, the war against discriminatory tendencies in practice requires political will from all the stakeholders involved.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Farai Maunganidze

Farai Maunganidze is a senior lecturer at Great Zimbabwe University, Department of Human Resource Management and a Research Associate with the University of Pretoria, Department of Sociology. From 2017 to 2019, he was a post-doctoral fellow with the University of Pretoria, Department of Sociology. His thesis obtained from the University of KwaZulu Natal focused on professions and professional work, an area which he has decided to pursue. He is also a member of the International Sociology Association (ISA) under Research Committee 52 which focuses on professions.

References

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4(2), 139–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002

- Adisa, T. A., Abdulraheem, I., & Isiaka, S. B. (2019). Patriarchal hegemony: Investigating the impact of patriarchy on women’s work-life balance. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 34(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2018-0095

- Archer, L. (2011). Constructing minority ethnic middle-class identity: An exploratory study with parents, pupils and young professionals. Sociology, 45(1), 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510387187

- Azmat, G., & Ferrer, R. (2017). Gender gaps in performance: Evidence from young lawyers. Journal of Political Economy, 125(5), 1306–1355. https://doi.org/10.1086/693686

- Bagust, J. (2014). The culture of bullying in Australian corporate law firms. Legal Ethics, 17(2), 177–201. https://doi.org/10.5235/1460728X.17.2.177

- Bartolomé, F., & Evans, P. A. L. (1979). Professional lives versus private lives-shifting patterns of managerial commitment. Organizational Dynamics, 7(4), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(79)90019-6

- Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2002). Individualization: Institutionalized individualism and its social and political consequences. Sage.

- Bilen-Green, C., Froelich, K. A., & Jacobson, S. W. (2008). The prevalence of women in academic leadership positions, and potential impact on prevalence of women in the professorial ranks. IPaper presented at Women in Engineering ProActive Network Annual Conference, St. Louis.

- Bolton, S. C., & Muzio, D. (2007). Can’t live with ‘em; can’t live without ‘em: gendered segmentation in the legal profession. Sociology, 41(1), 47–64.

- Bourgeault, I. L. (2017). Conceptualizing the social and political context of the health workforce: Health professions, the state, and its gender dimensions. Frontiers in Sociology, 2, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2017.00016

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. (pp. 843–860). New York, NY: Springer (in press).

- Buchanan, N. T., Settles, I. H., Hall, A. T., & O’Connor, R. C. (2014). A review of organizational strategies for reducing sexual harassment: Insights from the US military. Journal of Social Issues, 70(4), 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12086

- Carbado, D. W., & Gulati, M. (1999). Working identity. Cornell Law. Review., 85(1), 1259-1308.

- Cassell, C., Cunliffe, A. L., & Grandy, G. (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods.. Sage. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1679432

- Chabata, T. (2012). The commercialisation of lobola in contemporary Zimbabwe. A Journal on African Women’s Experiences, 2(1), 11-14.

- Chabaya, O., Rembe, S., & Wadesango, N. (2009). The persistence of gender inequality in Zimbabwe: Factors that impede the advancement of women into leadership positions in primary schools. South African Journal of Education, 29(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n2a259

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Charvet, J. (1982). Modern Ideologies: Feminism. In London: JM dent and sons limited.

- Chireshe, E., & Chireshe, R. (2010). Lobola: The perceptions of great Zimbabwe university students. Journal of Pan African Studies, 3(9), 211–221.

- Chiweshe, M. K. (2016). Wives at the market place: Commercialisation of lobola and commodification of women’s bodies in Zimbabwe. The Oriental Anthropologist, 16(2), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0976343020160202

- Choroszewicz, M. (2016). Women attorneys and gendering processes in law firms in Helsinki. Sosiologia, 53(2), 122–137.

- Chuma, M., & Ncube, F. (2010). Operating in men’s shoes’: Challenges faced by female managers in the banking sector of Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 12(7), 172–185.

- Clerc, I., & Kels, P. (2013). Coping with career boundaries in masculine professions: Career politics of female professionals in the ICT and energy supplier industries in Switzerland. Gender, Work, and Organization, 20(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12017

- Coolican, H. (2017). Research methods and statistics in psychology. Psychology Press.

- Corbin, J., Strauss, A., & Strauss, A. L. (2014). Basics of qualitative research. Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative. and mixed methods approaches: Sage publications.

- Crompton, R., & Harris, F. (1999). Employment, careers, and families: The significance of choice and constraint in women’s lives. In Restructuring gender relations and employment: The decline of the male breadwinner (pp. 128–149). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deery, M., & Jago, L. (2015). Revisiting talent management, work-life balance and retention strategies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(3), 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2013-0538

- DePasquale, N., Polenick, C. A., Davis, K. D., Moen, P., Hammer, L. B., & Almeida, D. M. (2017). The psychosocial implications of managing work and family caregiving roles: Gender differences among information technology professionals. Journal of Family Issues, 38(11), 1495–1519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15584680

- Diehl, A. B., & Dzubinski, L. M. (2016). Making the invisible visible: A cross‐sector analysis of gender‐based leadership barriers. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 27(2), 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21248

- Gorman, E. H., & Kmec, J. A. (2009). Hierarchical rank and women’s organizational mobility: Glass ceilings in corporate law firms. American Journal of Sociology, 114(5), 1428–1474. https://doi.org/10.1086/595950

- Greed, C. (2000). Women in the construction professions: Achieving critical mass. Gender, Work, and Organization, 7(3), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00106

- Greenglass, E. R., & Burke, R. J. (2016). Stress and the effects of hospital restructuring in nurses. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive, 33(2), 93-108.

- Greenhaus, J. H. (1988). The intersection of work and family roles: Individual, interpersonal, and organizational issues. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 3(4), 23.

- Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., Singh, R., & Parasuraman, S. (1997). Work and family influences on departure from public accounting. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50(2), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.1578

- Greenman, E., & Xie, Y. (2006). Is assimilation theory dead. In Population studies centre, university of Michigan.

- Gutek, B. A., Searle, S., & Klepa, L. (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(4), 560. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.4.560

- Hlatywayo, C. K., Zingwe, T., Mhlanga, T. S., & Mpofu, B. D. (2014). Precursors of emotional stability, stress, and work-family conflict among female bank employees. The International Business & Economics Research Journal (Online), 13(4), 861.

- Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (2012). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. Penguin.

- Iofrida, N., De Luca, A. I., Strano, A., & Gulisano, G. (2018). Can social research paradigms justify the diversity of approaches to social life cycle assessment? The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 23(3), 464–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1206-6

- Kambarami, M. (2006). Femininity, sexuality and culture: Patriarchy and female subordination in Zimbabwe. In South Africa: ARSRC.

- Kanwar, A., Ferreira, F., & Latchem, C. (2013). Women and leadership in open and distance learning and development: Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning (COL).

- Kavitha, V. (2017). The relationship and effect of role overload, role ambiguity, work-life balance and career development on work stress among call center executives of business process outsourcing (BPO) in Selangor. Universiti Utara Malaysia.

- Kay, F. M., Alarie, S. L., & Adjei, J. K. (2016). Undermining gender equality: Female attrition from private law practice. Law & Society Review, 50(3), 766–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12214

- Kickbusch, I., Allen, L., & Franz, C. (2016). The commercial determinants of health. The Lancet Global Health, 4(12), e895–e896. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30217-0

- Kivunja, C., & Kuyini, A. B. (2017). Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(5), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26

- Lee, A. R., Son, S.-M., & Kim, K. K. (2016). Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.011

- Long, A. B. (2016). Employment discrimination in the legal profession: A question of ethics. In U. Ill. L. Rev 2. (pp. 445).

- Mani, V. (2013). Work life balance and women professionals. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 13(5), 1-8.

- Mansour, S., & Tremblay, D.-G. (2016). Workload, generic and work–family specific social supports and job stress: Mediating role of work–family and family–work conflict. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(8), 1778–1804. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0607

- Matthews, B., & Ross, L. (2014). Research methods. Pearson Higher Ed.

- Michelson, E. (2013). Women in the legal profession, 1970-2010: A study of the global supply of lawyers. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 20(2), 1071–1137. https://doi.org/10.2979/indjglolegstu.20.2.1071

- Mickel, A. E., & Dallimore, E. J. (2009). Life-quality decisions: Tension-management strategies used by individuals when making tradeoffs. Human Relations, 62(5), 627–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709103453

- Montgomery, E. T., Chidanyika, A., Chipato, T., & van der Straten, A. (2012). Sharing the trousers: Gender roles and relationships in an HIV-prevention trial in Zimbabwe. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(7), 795–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.697191

- Mouton, J., & Babbie, E. (2001). The practice of social research. Cape town, Soth Africa: Van Schaik Publishers.

- Msila, V., & Netshitangani, T. (2016). Women and leadership: Learning from an African philosophy. Africanising the Curriculum: Indigenous Perspectives and Theories, 2(1), 83–95.

- Muchemwa, F., & Erzingatsian, K. (2014). Women in surgery: Factors deterring women from being surgeons in Zimbabwe. East and Central African Journal of Surgery, 19(2), 5–11.

- Nelson, R. J., & Nelson, R. L. (1988). Partners with power:. The social transformation of the large law firm: Univ of California Press.

- Omar, M. K., Mohd, I. H., & Ariffin, M. S. (2015). Workload, role conflict and work-life balance among employees of an enforcement agency in Malaysia. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law, 8(2), 52–57.

- Owoyemi, O., & Olusanya, O. (2014). Gender: A precursor for discriminating against women in paid employment in Nigeria. American Journal of Business and Management, 3(1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.11634/216796061403399

- Packard, M. D. (2017). Where did interpretivism go in the theory of entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 536–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.05.004

- Pateman, C. (2016). Sexual contract. In The wiley blackwell encyclopedia of gender and sexuality studies (pp. 1–3).

- Peng, A. (2017). Is marriage a must? hegemonic femininity and the portrayal of “leftover women” in chinese television drama. PhD Dissertation, Syracuse University.

- Powell, A., & Sang, K. J. (2015). Everyday experiences of sexism in male-dominated professions: A bourdieusian perspective. Sociology, 49(5), 919–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038515573475

- Pringle, J. K., Harris, C., Ravenswood, K., Giddings, L., Ryan, I., & Jaeger, S. (2017). Women’s career progression in law firms: Views from the top, views from below. Gender, Work, and Organization, 24(4), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12180

- Pringle, R. (1992). Defining women: Social institutions and gender divisions (Vol. 2). Polity.

- Raz, A. E., & Tzruya, G. (2018). Doing gender in segregated and assimilative organizations: ultra‐orthodox jewish women in the Israeli high‐tech labour market. Gender, Work, and Organization, 25(4), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12205

- Richman, L. S., & Wood, W. (2011). How women cope: Being a numerical minority in a male‐dominated profession. Journal of Social Issues, 67(3), 492–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01711.x

- Ross, M. M. S., & Godwin, A. (2016). Engineering identity implications on the retention of Black women in engineering industry. Paper presented at the American society for engineering education annual conference, New Orleans, LA.

- Sadruddin, M. M. (2013). Sexual harassment at workplace in Pakistan-issues and remedies about the global issue at managerial sector. Journal of Managerial Sciences, 7(1), 113-125.

- Saks, M. (2015). Inequalities, marginality and the professions. Current Sociology, 63(6), 850–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392115587332

- Saks, M., & Brock, D. M. (2017). Professions and Organizations. Management Research: European Perspectives, 34(1), 1-6.

- Schnall, P. L., Dobson, M., Rosskam, E., & Elling, R. H. (2018). Unhealthy work: Causes, consequences, cures. Routledge.

- Schultz, V. (2018). Telling stories about women and work: Judicial interpretations of sex segregation in the workplace in title vii cases raising the lack of interest argument [1990]. In Feminist legal theory (pp. 124–155). Routledge.

- Seemann, N. M., Webster, F., Holden, H. A., Carol-anne, E. M., Baxter, N., Desjardins, C., & Cil, T. (2016). Women in academic surgery: Why is the playing field still not level? The American Journal of Surgery, 211(2), 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.036

- Shava, G. N., & Ndebele, C. (2014). Challenges and opportunities for women in distance education management positions: Experiences from the zimbabwe open university (ZOU). Journal of Social Sciences, 40(3), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2014.11893331

- Sommerlad, H. (2016). “A pit to put women in”: Professionalism, work intensification, sexualisation and work–life balance in the legal profession in England and Wales. International Journal of the Legal Profession, 23(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695958.2016.1140945

- Sommerlad, H., & Sanderson, P. (2018). Gender, choice and commitment: Women solicitors in England and wales and the struggle for equal status. Routledge.

- Southworth, A. (2017). Our fragmented profession. Geo. Journal Legal Ethics, 30(1), 431-446.

- Stainback, K., Kleiner, S., & Skaggs, S. (2016). Women in power: Undoing or redoing the gendered organization? Gender & Society, 30(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243215602906

- Sterling, J. S., & Reichman, N. (2016). Overlooked and undervalued: Women in private law practice. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 12(1), 373–393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-120814-121705

- Stewart, J. E. (2012). Lawyers? Women? Women Lawyers in Zimbabwe? Journal of Law & Social Research (JLSR), 2(3), 11–28.

- Terre Blanche, M., Durrheim, K., & Painter, D. (2006). Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences. UCT Press.

- Thein, H. H., Austen, S., Currie, J., & Lewin, E. (2010). The impact of cultural context on the perception of work/family balance by professional women in Singapore and Hong Kong. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 10(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595810384585

- Tomlinson, J. (2006). Women’s work-life balance trajectories in the UK: Reformulating choice and constraint in transitions through part-time work across the life-course. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 34(3), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880600769555

- Tomlinson, J., Muzio, D., Sommerlad, H., Webley, L., & Duff, L. (2013). Structure, agency and career strategies of white women and black and minority ethnic individuals in the legal profession. Human Relations, 66(2), 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712460556

- Tremblay, D. G. M., & Wu, J., Eds. (2016). Work-Family Balance for Women Lawyers Today: A Reality or Still a Dream? Connerley. Handbook on Well-Being of Working Women. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life.Springer.

- Voydanoff, P. (1988). Work role characteristics, family structure demands, and work/family conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50(3), 749–761. https://doi.org/10.2307/352644

- Wadesango, N., Rembe, S., & Chabaya, O. (2011). Violation of women’s rights by harmful traditional practices. The Anthropologist, 13(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2011.11891187

- Wajcman, J. (2013). Managing like a man:. Women and men in corporate management: John Wiley & Sons.

- Wallace, J. E. (1999). Work‐to‐nonwork conflict among married male and female lawyers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(6), 797–816. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199911)20:6<797::AID-JOB942>3.0.CO;2-D

- Wallace, J. E. (2004). MOTHERHOOD AND CAREER COMMITMENT TO THE LEGAL PROFESSION. In Diversity in the work force (Vol. 14, pp. 219–246). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Wallace, J. E. (2006). Can Women in Law Have it All? A Study of Motherhood, Career Satisfaction and Life Balance. In Professional service firms (Vol. 24, pp. 283–306). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Walliman, N. (2017). Research methods: The basics. Routledge.

- Wass, V., & McNabb, R. (2006). Pay, promotion and parenthood amongst women solicitors. Work, Employment & Society, 20(2), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017006064115

- Wattis, L., Standing, K., & Yerkes, M. A. (2013). Mothers and work–life balance: Exploring the contradictions and complexities involved in work–family negotiation. Community, Work & Family, 16(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2012.722008

- Whatmore, S. (2016). Farming women: Gender, work and family enterprise. Springer.

- Williams, J. C. (2018). Deconstructing Gender [1989]. In Feminist Legal Theory (pp. 95–123). Routledge.

- Zinyemba, A. (2013). Leadership challenges for women manager in the hospitality and financial services in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 2(4), 15–21.