Abstract

This article analyses the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) fleet personnel’s responses to survey questionnaire items on the knowledge creation processes, in order to identify the current extent of processes within the fleet. Through knowledge creation, new knowledge is created, starting with the discovery of knowledge and eventually, new and additional knowledge creation. Saving this created knowledge from dissipating is crucial to remain relevant. Hence, a survey was conducted on 214 of the fleet’s personnel utilizing the Knowledge Creation Process SECI Model. The results revealed that knowledge creation processes are being practised in the fleet. However, the extent varied and most of the RMN fleet personnel participated at a moderate level in the processes. Socialization and internalization process dimensions are more actively utilized than externalization and combination process dimensions in knowledge creation within the fleet. Respondents with different demographic profiles had differences in their opinions, perceptions, and attitudes towards the knowledge creation processes. This needs to be looked into further since a sophisticated fleet with state-of-the-art inventories worth billions has many stakeholders concerned with safeguarding the sovereignty of the nation’s maritime interests. Therefore, this study is the foundation to assist the organization to assess issues and differences related to knowledge creation in order to improve organization performance.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The development and survivability of organizations depend on knowledge, as productivity would be enhanced if organizations know the value of knowledge as resources. Through knowledge creation and knowledge sharing, new knowledge is created and merged utilizing strategic and systematic method. It begins with the discovery of knowledge and eventually, new and additional knowledge creation. It is crucial for organizations to ensure that knowledge created within the organization does not dissipate in order to remain relevant in the current turbulent environment. Each time a personnel is transferred out or retired, they leave with substantial amount of organizational knowledge. Hence, this study is the foundation to assist any organization regardless in public or private sector, in eliminating the knowledge dissipation problem by assessing issues related to opinions, perceptions, and attitudes of personnel in knowledge creation.

1. Introduction

According to Memon (Citation2015), survivability and development of any organization depend on knowledge since it is part of the competency necessary for performing effectively (Salleh & Sulaiman, Citation2016). Previous researchers claimed that organization is a body of knowledge (Cavusgil et al., Citation2003; Gonzalez & Melo, Citation2018; Sikombe et al., Citation2019). They added that if the knowledge is properly leveraged, the importance can far exceed the physical resources. The initiatives of knowledge management (KM) are principally depending on how personnel share knowledge among them (Amber et al., Citation2019; Choi, Citation2016; Ipe, Citation2003). Sharing of knowledge is the critical element for organization to improve, both in private and public sector, by increasing the productivity and efficiency of organization (Amayah, Citation2013; Amber et al., Citation2019; Chong et al., Citation2011; Kim & Lee, Citation2006; Willem & Buelens, Citation2007; Wong et al., Citation2013).

Most successful organizations constantly create new knowledge (Nonaka, Citation1994). Bhatt (Citation2000), Salisbury (Citation2008), and Kaba and Ramaiah (Citation2017) posited that knowledge creation is the first stage in the life cycle of knowledge. Knowledge creation is seen to be the initiating component or element in KM (Mehralian et al., Citation2018). Amber et al. (Citation2019), Choi (Citation2016), and J. Zhang and Dawes (Citation2006) posited that in managerial reforms, knowledge-based reforms deemed to be important and they focus on knowledge creation with the process of accumulation and dissemination of knowledge (Amber et al., Citation2019; Choi, Citation2016). Mehralian et al. (Citation2018) further added that knowledge creation is so critical that most of the organizations are trying their best to be competitive by creating knowledge that will assist them to achieve their objectives.

Military organizations all around the world agree that the personnel within their organizations are actually their main and most vital assets and at the same time the sources of their organizational knowledge (Manuri, Citation2012). When personnel are transferred or retired from an organization, they leave with lots of knowledge that they have accumulated over their working years. This knowledge base must then to be re-created, re-built or reconstructed by new personnel who take up the posts. Thus, Nielsen and Razmerita (Citation2014) emphasized the need for managers and management to get actively involved in motivating and encouraging knowledge creation and knowledge sharing among personnel. Kianto et al. (Citation2016) also suggested that, management of knowledge can indeed nurture job satisfaction and, in so doing, foster high organizational performance.

On the other hand, Mafabi et al. (Citation2017) posited that it is important to share created knowledge among personnel because sharing will assist personal mastery through knowledge retention and action learning, such as in cases where knowledgeable personnel quit the job. Knowledge creation processes within the KM could also affect the utilization of adopted or adapted state-of-the-art equipment and technologies in military inventories which are used to achieve advantages in knowledge, thus increasing the sustainable competitive advantage of the organization (Manuri, Citation2012) or in other words, for the RMN fleet to remain relevant in safeguarding the sovereignty of the nation and its maritime interests. Since study in this field is scarce in the military context, especially the fleet, this research will contributes to the growth and development of new knowledge since the evolution of knowledge is of vital importance for a sophisticated organization like the RMN fleet. Hence, there is an obligation to produce and utilize knowledge effectively as active, dynamic and vigorous aspects of the life cycle of knowledge (Kaba & Ramaiah, Citation2017).

Easa (Citation2012) posited that an organization’s knowledge base is not only formal knowledge in the context of documentations, like SOPs, training programmes or formal information, but as Garvey and Williamson (Citation2002) and Tsoukas and Vladimirou (Citation2001) argued, it is also informal and tacit knowledge that is taken for granted. Easa (Citation2012) further added that informal knowledge is something personal, and it reflects personnel’s experiences, education levels and most importantly, the tacit understanding of individuals. This informal knowledge covers personnel’s attitudes towards their work and willingness to work for and with the organization, in general, and specifically, with and for one another (Tsoukas & Vladimirou, Citation2001). Hence, it is vital for the RMN fleet to do what is necessary to grab hold of this valuable asset through any platforms. On the other hand, Collins (Citation2010) posited that tacit knowledge is context specific, highly personal, and also deeply rooted in an individual’s emotions, values, ideas, and experiences, and there is no doubt that in the sophisticated RMN fleet, there is a lot of tacit knowledge that is required to be transferred through conferences, seminars, workshops, and meetings, despite all the available documentation.

In this study, the level or extent of knowledge creation processes need to be determined to ensure the processes are currently being practiced within the RMN fleet. The focus on the creation of knowledge in the organization is based on the SECI Model by Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995a, Citation1995b). This model from the management and organization field of study provides a platform and framework which comprehensively covers the knowledge creation process (Earl, Citation2001; Von Krogh et al., Citation2000). Hence, this study attempted to provide a clearer understanding of the aspects of each process contained in the SECI Model through RMN fleet personnel’s responses to questionnaire items and differences response in their demographic profiles. To pursue that, a quantitative method using questionnaires for data collection was adopted wherein the Rasch Model approach and Winsteps version 3.73 software were employed to assess issues related to the opinions, perceptions, and attitudes of the RMN fleet’s personnel on knowledge creation within the organization.

2. Knowledge creation

Mehralian et al. (Citation2018) opined that in whatever ways KM is defined in previous studies, knowledge creation process is seen to be the most vital and important in KM activities. The main reason why KM seems to triggered the great interest of many managers was largely due to knowledge creation potential that is very important in providing the means of innovative culture within the organizations (Mehralian et al., Citation2018).

Knowledge creation has been identified to provide values and competitive advantage to organizations (Bryant, Citation2005; Tsoukas & Mylonopoulos, Citation2004). It also can be defined as the capacity of organization to develop new ideas and the process of developing new knowledge in order to replace the old one (Pentland, Citation1995). It is a dynamic process which involve interactions at various level of organizations (Inkpen, Citation1996). Nonaka (Citation1994) stated that knowledge creation refers to a continuous process where personnel overcomes individual limitations imposed by prevailing information and past experiences by attaining new perspectives or observations of new environments and new knowledge. In other words, creation of knowledge process is a process of learning (Grimsdottir et al., Citation2019) as argued by Garvin (Citation1993) that by learning from experience, solving problems, experimenting with new approaches and sharing knowledge, new knowledge created.

Knowledge creation occurs when data is manipulated to become information and ultimately, knowledge is interpreted and used by personnel (Kalpic & Bernus, Citation2006). Ahmad et al. (Citation2011) added that new knowledge creation concerns experiments and testing of theories and model development to understand social and natural processes. On the other hand, Jogulu and Pansiri (Citation2011) posited that knowledge creation refers to different findings created through multiple data collection and analysis techniques that provide insightfulness and extensiveness in overall results. New knowledge can be generated in several ways. However, human creativity and innovation have been always the limelight of knowledge creation, where all the data and information need to be organized and analyzed by personnel to become new knowledge (Nonaka, Citation1994; Yang et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, Memon (Citation2015) brought up an interesting argument regarding the influence of the higher echelon during the knowledge creation process that could impact the processes, especially in relation to policies and decisions.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995a, Citation1995b) came out with one of the most influential theory of knowledge creation, which argued that interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge via socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization, leads to new knowledge creation (Grimsdottir et al., Citation2019; Nonaka & Konno, Citation1998; Nonaka and Takeuchi, Citation1995a, Citation1995b; Nonaka et al., Citation2000). Previous studies (Esterhuizen et al., Citation2012; Popadiuk & Choo, Citation2006; Sankowska, Citation2013), emphasized on the importance of the SECI model with regards to innovation in the organization. However, some issues have been put forward (Grimsdottir et al., Citation2019 & Esterhuizen et al., Citation2012), especially criticisms on the model that deemed not to be explaining how new ideas are formed and how the depth of understanding develops (Bereiter, Citation2002; Gourlay, Citation2006). To counter these, multiple studies were conducted by few scholars on explanation of why knowledge creation occurs in organization. For example, the study on understanding of knowledge creation in the context of knowledge-intensive business processes by Little and Deokar (Citation2016), by Hubers et al. (Citation2016) in the context of educational science, W. Zhang and Zhang (Citation2018) on knowledge creation through industry chain (chemical) in resource-based industry, and Li et al. (Citation2018) that proposed new knowledge creation model, Grey SECI (G-SECI), the enhancement of SECI model in the complex product systems development. Canonico et al. (Citation2019) and Tsai and Huili (Citation2007) also posited about the conditions that can facilitate the creation of knowledge and how to encourage the process and Chen et al. (Citation2012) added about the organizational mechanisms that will allow personnel to create knowledge within the organization. However, recent studies are almost none on exploring knowledge creation in the military context especially on the navy fleet. So, the study on knowledge creation in the RMN fleet was conducted to help identify the perception of navy personnel on knowledge creation processes that was based on SECI Model by Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995a, Citation1995b). The next subsections will discuss and elaborate more on the dimensions of knowledge creation processes namely, socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization.

2.1. Knowledge creation process – SECI model

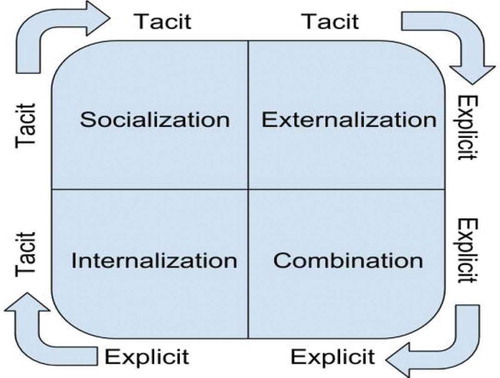

The SECI Model (Figure ) is a knowledge-creating process model, which is also known as a wheel of tacit and explicit knowledge transformation, developed by Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995a, Citation1995b). It stresses socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization as phases or modes of knowledge creation. It emphasizes the creation process of tacit or explicit knowledge and leveraging this process to establish knowledge networks within organizations (Warkentin et al., Citation2001). This model is in the context of business organization. However, it can be generalized in other sectors as discussed above, for instance, educational science, resource-based industry, product systems development and also financial (Allal-Chérif & Makhlouf, Citation2018) and entrepreneurship (Bandera et al., Citation2017). The researchers feel that it can be generalized in the military context too. Hence, the study is undertaken to assess the knowledge creation process perspective within the RMN fleet.

Figure 1. (Source: Nonaka and Takeuchi, Citation1995a, Citation1995b)SECI Model.

The cognitive model focuses on tacit and explicit knowledge conversion and on how to exchange this knowledge (Oskouei, Citation2013). This model also assists in knowing how to make both types of knowledge available at all levels of organizations. Furthermore, Huang et al. (Citation2010) stated that the application of the SECI Model will enrich the insights of an organization into their knowledge creation and the processes involved.

According to Hargreaves (Citation1999) and Schaap et al. (Citation2009), study on personnel involve in SECI model is scarce and Baldé et al. (Citation2018) posited that the picture is still incomplete even though numerous researches have been conducted on SECI Model. A study by Yeh et al. (Citation2011) established that respondents’ (in educational science) professional knowledge increased after working through the model. However, it was unclear on how and in what order they actually engaged in SECI. Hubers et al. (Citation2016) posited that it is still yet unknown, whether personnel are engaged in SECI in similar or different manner. They further theorized that the way personnel engages in SECI influences knowledge creation processes.

Adaptive Control of Thought (ACT) Model (Anderson, Citation1983) mentioned that continuous transformation of declarative (actual) knowledge leads to the cognitive development of skills and this finding is consistent with research by Ryle (Citation1949). Nonaka (Citation1994) however, argued that the transformation of knowledge explained by ACT Model showed that it is only unidirectional instead of being bidirectional. Hence, Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995a, Citation1995b) came out with SECI Model that explained the relationship between tacit and explicit knowledge.

On the other hand, Shahzad et al. (Citation2016) posited that Knowledge-Based View (KBV) of the Firm Theory (Grant, (Citation1996)) explains all the knowledge processes and their relationship with creativity and performance within the organization. So, based on the knowledge requirements and characteristics of knowledge, an organization, for instance, the RMN fleet is conceptualized as a body for integrating knowledge since knowledge is the most strategic and significant resource for ensuring the organization to have a sustainable competitive advantage and superior performance (Easterby-Smith et al., Citation2008).

There are few more management theories and models, for example, the one developed by Bose (Citation2004), Davenport and Prusak (Citation2000), and Hansen et al. (Citation1999). Nonetheless, the comprehensiveness of the SECI model is the main reason why the researchers chose the model for this study as compared to the other models that do not encompassed all of the knowledge creation processes. This is also supported by Grant and Grant (Citation2008) who stated that:

… the importance of Nonaka’s work is evidenced by its dominance as, by far, the most referenced material in the KM field and by the number of practitioner projects implementing elements of the model. While a variety of other knowledge classification systems have been proposed, variations on Nonaka’s interpretation of Polanyi’s original tacit/explicit knowledge concept dominate in the literature—both academic and practitioner. (p. 577)

The next sub-sections explain the four dimensions in SECI Model.

2.1.1. Socialization

Nonaka and Konno (Citation1998) posited that socialization is a process of new knowledge developed through sharing of personal experiences. Socialization also refers to a process of converting tacit to tacit knowledge through social interactions (Karim et al., Citation2012). It is about sharing experiences where the element of tacit knowledge being shared and created (Nonaka, Takeuchi & Umemoto, Citation1996). Expert knowledge can be transferred by interacting and taking part in group activities where skills and values will be mutually understood (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Nonaka (Citation1994) postulated that tacit knowledge can be acquired apart from normal conversation, by observation, imitation, and practice. Even when personnel cannot articulate knowledge, it will be transmitted to all through common interface and they can apply it when needed (Weick, Citation1995). Massingham (Citation2014) found that socialization worked well in his study via brainstorming on a discussed topic observed. Hence, personal interaction in socialization is one of the richest forms of communications and it will allow immediate feedback if needed (Koskinen & Vanharanta, Citation2002). This process can widely be observed within the RMN fleet by having conferences, seminars, workshops, meetings, etc.

2.1.2. Externalization

Externalization modes relate to the process of converting tacit into explicit knowledge through a systematized approach, which could involve the use of visual aids, concepts, analogies, metaphors, etc (Karim et al., Citation2012). In this mode, process of conversion for subjective, intangible, and inexpressible knowledge (tacit) to objective, tangible and expressible knowledge (explicit) took place (Memon, Citation2015). It can be achieved by writing (e.g.: description of work processes), through debates or arguments and self-reflection (Nonaka & Konno, Citation1998). According to Nonaka (Citation1994), tacit and explicit knowledge are complementing each other and by articulation, tacit knowledge transfer is possible (Hamel, Citation1991; Koskinen & Vanharanta, Citation2002). For example, externalization of knowledge can take place through multimedia interactions such as videos, pictures or online conversations (Razmerita et al., Citation2014). Knowledge used enables externalization, where knowledge creation, sharing, distribution, and exchange took place so that others can observe and participate (Kari, Citation2009). The end result for externalization mode is documentation of knowledge as can be witnessed in promulgation of standard operating procedures (SOPs), doctrines, policies, reports, minutes, and every documentation available within the RMN fleet.

2.1.3. Combination

Combination is the process of explicitly tested knowledge conversion within the organization (Nonaka & Konno, Citation1998). It is concerned with creating explicit knowledge from explicit knowledge and knowledge conversion involving social processes to combine different bodies of explicit knowledge held by individuals (Nonaka, Citation1994). Karim et al. (Citation2012) described that it is a process of using systematic mechanisms in converting explicit knowledge into explicit knowledge utilizing communication and integration, where personnel exchange and combine knowledge. It also provides knowledge repository that beneficial to others in knowledge management cycle (Nonaka & Takeuchi, Citation1995a, Citation1995b). Memon (Citation2015) posited that the combination and exchange of knowledge in tangible or intangible forms takes place by collecting new information through making connections between new and existing or old knowledge in order to organize new concepts in a more systematic or structured manner. This shared pool of knowledge possibly created will reflect standards and norms in organization (Weick, Citation1995). In the RMN fleet perspective, table-top exercises, war gaming or simulator training are the way forward in “testing” the old knowledge while creating new knowledge. In other words, in combination mode, we can obtain codified knowledge sources, for example, by combining old and new knowledge or combining documents to create new knowledge.

2.1.4. Internalization

Internalization begins when assessed knowledge acquired, incorporated, and integrated into personnel’s existing knowledge (Nonaka, Citation1994). It is the evaluation and integration of knowledge into normal regular work processes (Boland & Tenkasi, Citation1995). It is also a process of embodying unfamiliar explicit knowledge into work routines where it eventually becomes accustomed (Nonaka & Konno, Citation1998). Nonaka et al. (Citation2000) posited that the internalization mode is the process through which knowledge becomes valuable when it is internalized in personnel. New or improvised practices and standards internalized by personnel can be observed in the sense of professionalism, best practice and also how they conduct things (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). This process is closely related to the learning-by-doing process (Nonaka & Takeuchi, Citation1996). Karim et al. (Citation2012) added that it is the process of explicit to tacit knowledge conversion performed when personnel begin to utilize knowledge obtained in their routine or practical work. For instance, the RMN fleet personnel read the SOPs, doctrines, manuals, etc., which are explicit knowledge, and they internalize and apply the knowledge practically or in their routine work. Meanwhile, according to Memon (Citation2015), comparing and contrasting existing and new ideas, concepts, or knowledge with experience in the internalization mode are done to facilitate the understanding of meanings.

Previous studies (Hubers et al., Citation2016; Yeh et al., Citation2011) indicated that it was still unclear on how and in what order personnel engaged in SECI, whether it was similar or there were differences occur. Swap et al. (Citation2001) posited that transference of organizational knowledge is done informally, mostly in socialization and internalization modes. The socialization and internalization modes are more critical according to Nonaka (Citation1994) because they require self-active involvement and stronger personal commitment thus making SECI is not equally important. These informal knowledge processes within the socialization and internalization modes are deemed to be very important in organizational learning processes, and their influence is important for organizational performance (Lahti et al., Citation2002). Hubers et al. (Citation2016) also found that personnel were more frequently and personally engaged in socialization and internalization modes where they gained deeper and more knowledge. They further encouraged the stimulation of active personal engagement in those two modes. However, externalization and combination modes also carry important practices and they are part of SECI Model and need not to be neglected. Hence, it is worth to look into the dimensions in order to establish a well-organised and balance organization, as mentioned by Nonaka (Citation1994) and Nonaka et al. (Citation2014) that if one out of four modes were impeded (especially socialization and internalization), both quality and quantity of knowledge will be deteriorating. Hubers et al. (Citation2016) further added that if socialization and internalization were improperly enacted, externalization and combination dimensions cannot be properly taken up and it will results in lack of progress and impermanent knowledge.

3. Methodology

This study employed a quantitative approach where a survey was conducted to understand the aspects of each process in the SECI Model. The following sub-sections describe the details of the survey.

3.1. Population and sampling

The sampling was administered in the 1st quarter of 2019. The researchers used stratified random sampling to highlight a specific subgroup within the population. It is the most efficient technique where all groups are adequately sampled and comparisons among them are possible (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016). This sampling also provides more precision and requires smaller sample. Proportionate allocation was used in this study to infer the results that represent the whole RMN fleet. Hence, the fleet personnel were stratified into senior, middle, and lower management level. There were approximately 400 personnel serving onboard the warships selected and according to Sekaran (Citation2013), 200 respondents are adequate for this study. However, the researchers took 300 respondents and a collective administrative survey was conducted, as the nature of the personnel onboard allowed the researcher to carry out such a survey, to ensure a high response rate, and to have personal contact with the participants (Kumar, Citation2011). Prior to the selection of samples, the researchers identified three different types of ship from different squadrons for sampling. They were a frigate, a corvette and a multi-purpose command support ship (MPCSS) that were located at the Lumut Naval Base. These ships were selected based on their importance in fleet operations, narrowed down to squadron leaders or the representative of the types of ships which adequately represented the fleet as a whole. This study excluded other units in the RMN.

Many ethical obligations may arise during data collection, data analysis and during the interpretation of collected data (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). The participation in survey was a voluntary basis and information was given to respondents about ethical approval by means of consent forms to be signed by them. They are free to withdraw if they are uncomfortable and wish to do so, as Collis and Hussey (Citation2014) posited that researchers must be responsible for ethical conduct and protection of the participants. On top of that, prior approval was also obtained from university research ethic committee, Fleet Commanders of the RMN fleet and Commanding Officers of the ships selected.

The senior level of management comprised officers with the rank of Lieutenant Commander and above. The middle level was from Petty Officer to Lieutenant, and the lower level was Leading Rate and below. The researchers distributed and collected 300 questionnaires (Sekaran, Citation2013). However, only 234 (78%) were analysed because 66 (22%) questionnaires were either incomplete or had multiple answers for one question and were thus rejected and removed from the data set. The data were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, then processed with the Rasch Model software, Winsteps version 3.73, for data validation and cleaning. There were no outlier responses in the data; however, further checking for detecting misfit responses found that 20 respondents needed to be omitted because of the way their responses differed from the rest. Ultimately, 214 (71.3%) respondents were retained for analysis. The demographic profile of respondents is shown in Table .

Table 1. Demographic data of RMN fleet personnel (N = 214)

3.2. Instrument

A questionnaire survey was conducted to get a clearer and better understanding of the respondents’ levels of awareness and thinking in the knowledge creation processes. Curley et al. (Citation2002) mentioned that it is necessary to use questionnaires since it seems to be almost impossible to individually interview the personnel in an organization to obtain relevant data and information. A collective administrative survey was conducted as the nature of the participating personnel allowed the researcher to carry out such a survey to ensure a high response rate and to have personal contact with the participants (Kumar, Citation2011). The questionnaire was developed with closed-ended questions to get the relevant data or information pertaining to the study. According to Curley et al. (Citation2002), closed-ended questions force quick responses, can be scored quickly and expedite later evaluation. In this study, ordinal type data were gathered from the questionnaire.

This study is based on a knowledge creation processes instrument that has four dimensions: socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization. The questionnaire was adapted from Easa (Citation2012) as per Appendix 1. Responses to the items were based on a five-point Likert rating scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). A pilot study was done with five RMN fleet personnel to test the items’ content. Slight changes were made based on the comments. Demographic profile information such as academic qualification, job position, type of ship, number of training programmes attended and length of service were utilized in this study to find differences in how personnel responded to the items. The survey was conducted within the RMN fleet during the ships were non-operational or secured alongside the operational jetty of the naval base.

3.3. Measurement model and data analysis

The appropriate analysis for this type of data is using a Rasch Model rating scale, where the ordinal data are counted as frequencies then looked as odd probability. After that, the probability is converted into equal-interval-type data using a logarithm (Boone et al., Citation2016; Sumintono & Widhiarso, Citation2014). The logarithm function is used to produce measurements with the same equal-interval scale. Then a measurement model is calibrated by the process of conjoint-measurement to determine the relationship between the item difficulty level and person ability using the same unit-scale called a logit (logarithm odd unit). The data were prepared to be imputed using Winsteps version 3.73 software (Linacre, Citation2013).

The Rasch Model rating scale is particularly suitable for measuring latent traits in assessing human opinions, perceptions, and attitudes (Bond & Fox, Citation2015; Engelhard, Citation2013; Sondergeld & Johnson, Citation2014). With the Rasch analysis, the results can explain item difficulty levels with accurate and precise measurement (item calibration), detecting item fit, identifying item bias (differential item functioning [DIF]), as well as measuring the respondent knowledge creation level (Linacre, Citation2013). Further, respondent analysis using this measurement model provides better and more accurate results that will be more helpful in obtaining the consistency of responses to the questionnaire (person-fit statistics).

The two-facet item and person rating scale model were processed for 53 knowledge creation process items and 214 respondents using the Rasch Model approach. The items were centred at zero, which allowed the person to “float” calibrated their knowledge creation level. As shown in Table , the mean measure (logit) of the items is 0.00 logit and the standard deviation is relatively low (0.29), suggesting that dispersion of measures was not wide across the logit scale in terms of item difficulty level. For person, the logit mean was 0.36 logit, showing all respondents tended to be slightly involved in the knowledge creation process, but the standard deviation of 1.24 indicates a very wide dispersion level. The average outfit mean-square statistics are near their expected value of 1, both for item and person, and the chi-squared value is significant, showing uniform fit to the model (Boone et al., Citation2016; Engelhard, Citation2013). The strata index (equal to or more than three) and reliability (more than 0.67) item and person statistics suggest very good reliability (Fisher, Citation2007).

Table 2. Summary person and item statistics

Rating criteria used in this current study, as stated previously were five ratings (agreement levels from strongly disagree to strongly agree), the separation statistics of the Likert-type ratings 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 showed that the threshold does not have an ideal distance between rating 1 (strongly disagree) and 2 (disagree). The researchers then collapsed the ratings into four, which were then 1, 1, 2, 3, and 4, which resulted in an ideal distance value between the rating scale of 1.40 to 5.0 logit (Van Zile-Tamsen, Citation2017).

4. Results

The results of the study are described in the following sub-sections.

4.1. Item difficulty

Table classifies the items according to their item difficulty level or logit value of item (LVI). The classification of the items into four difficulty levels was done by dividing the distribution of the item logit scores based on mean and standard deviation values. There were 10 items (18%) in the category of very difficult to agree with by respondents (LVI > 0.29 logit); in the second category, which is difficult to agree (+0.29 ≥ LVI ≥ 0.00), there were 16 items (30%); in the next category which is easy to agree with by respondents (0.00 ≥ LVI ≥ −0.29) there were also 16 items (30%); and lastly 13 items (22%) fall into the category very easy to agree with by the respondents (LVI < −0.29 logit).

Table 3. Knowledge Creation Processes Item Calibration

As shown in the table above, the socialization process dimension tended to be easily conducted by the RMN fleet personnel, where 10 (A5, A11, A2, A1, A4, A3, A6, A7, A10, A14) out of 14 items fall into the easy and very easy to agree with categories. In contrast, the externalization and combination process dimensions tended toward not being easy to do (nine [B2, B9, B8, B11, B13, B6, B7, B4, B10, and C4, C11, C12, C13, C3, C6, C10, C9, C7] out of 13 items fell into the difficult and very difficult to agree with categories). The internationalization process dimension did not have very difficult items, with nine out of 13 items categorised as easy to agree with. This indicates that the perception of RMN fleet personnel on the knowledge creation process was that they did not have much difficulty in terms of socialization and internalization processes compared to externalization and combination processes, which they perceived as difficult to be conducted.

Figure is an item-person map of the study resulted from Winstep software where 214 respondents answered 53 knowledge creation process items. The right side of the map shows each item’s level of difficulty, ranging from easy to agree with by the respondents in the bottom right (logit score −1.49 for item A14) to the hardest one to agree with on the top right (logit score +0.71 for item A13). The items work well and are capable of separating RMN fleet personnel participation levels for knowledge creation processes, with a unidimensional raw variance index of 32.2%.

The left-hand side shows the distribution of RMN fleet personnel respondents according to their logit scores, ranging from the very-high level of participation in knowledge creation processes on the top left (logit score > +1.6) to the low level of participation in the bottom left (logit score < −0.88). The respondents’ distribution of the person logit score is divided into four categories based on mean and standard deviation values, from the very-high level of participation at the top left to the low level of knowledge creation at the bottom left.

4.2. Person level of knowledge creation process participation

Based on the mean and standard deviation of the person logit shown in Figure , Table categorizes RMN fleet personnel into four levels of participation in knowledge creation processes (very high level to low level of participation). Using the demographic profile of personnel and its logit value of person (LVP), the table below provides details for each group’s level of participation.

Table 4. RMN Fleet Personnel (N = 214)

The table above shows that regardless of demographic profile differences, most of the RMN fleet personnel were at the moderate level of participation in knowledge creation processes. Some were observed at the high level of participation, which included those with education at diploma and degree levels, 2–3 years of service on board, ship type of the corvette class, serving in the technical and other departments, and those who had attended training programme twice. However, the difference of value between high to moderate participation was almost insignificant.

There were two interesting trends in the results that relate demographic variables of RMN fleet personnel with their level of participation in knowledge creation processes, which are in terms of the type of ship on which they served and number of training programme attended.

Figure shows that RMN fleet personnel who served aboard the multi-purpose command support ship (MPCSS) were more active in knowledge creation processes, followed by sailors on board the corvette and then fleet personnel who worked on board the frigate. The combat ships (corvette and frigate) are equipped with state-of-the-art sensors and weaponry, while MPCSSs are not. Thus, it is perceived that aboard combat ships, knowledge creation takes place more in comparison to MPCSSs. This interesting finding indicates that even when ships are sophisticated, it does not mean that knowledge creation processes take place rigorously on board.

Meanwhile, Figure , below, indicates that the number of training programmes attended accounts for differences in the perceptions regarding RMN fleet personnel’s participation in knowledge creation processes in that more training tends to make them more active. This shows that training tends to make them change their perceptions and attitudes toward knowledge creation processes.

4.3. Differences between respondents’ demographic factors and the knowledge creation processes

The next stage of analysis is about differences between respondents’ demographic variables and knowledge creation process items. These were analysed using differential item functioning (DIF) analysis, the results of which suggested that respondents of separate subgroups responded differently to some items (Adams et al., Citation2020; Boone et al., Citation2014; Rouquette et al., Citation2019) when measuring distinctive knowledge creation processes at item level. The DIF analysis shows that only three demographic factors had significantly different responses (DIF probability index less than 5%) to items mentioned above, which were job position, type of ship and number of training programmes attended.

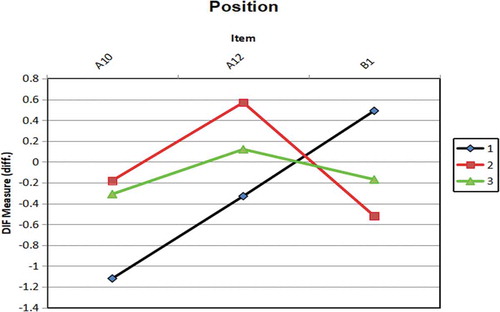

Figure 5. Person DIF Plot Based on RMN Fleet Management Level.

Based on the RMN fleet personnel responses, three items were identified as having significant differences based on management position. The graph in Figure shows that service members at the senior management level tended to more easily agree with item A10 (involving the RMN fleet in joint operations/exercises supports staff’s knowledge through face-to-face interaction with others) and A12 (the RMN fleet invites its qualified members and external experts to speak about their beliefs, values and culture) compared to personnel at the middle and lower levels. Interestingly, item B1 on the externalization process (when others can’t understand me, I am usually able to give examples to help explaining) was easier for respondents with middle and lower job positions to agree with than it was for those at the senior management level.

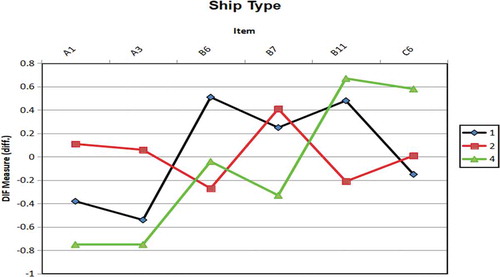

Figure 6. Person DIF Plot Based on Ship Type.

In terms of the ship types that fleet personnel served aboard, six items were identified as having significant DIF bias (Figure ). Sailors who served on board MPCSSs found it easier to agree with items A1 (during discussion, I try to find out others’ opinions, concept, thoughts or ideas), A3 (my colleagues and I will actively share life or work experience with each other) and B7 (I facilitate creative and constructive conversation among group members) compared to those serving on other ship types. The personnel of the two combat ship types had the same response for item B7 (they did not often do it), but indicated doing more in relation to new things (C6: I engage in developing criteria to determine the value of new concepts), showing they often engage themselves in learning about new concepts. Sailors who worked on board corvettes are interestingly more active in producing reports based on their experience (item B11: the RMN fleet issues reports of externals based on its accumulated experience).

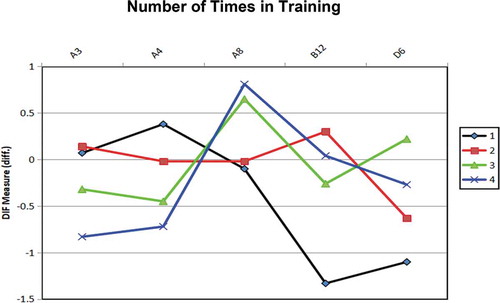

Figure 7. Person DIF Plot Based on Number of Times Involved in Training.

The DIF analysis based on number of times involved in training showed unique responses (Figure ). Sailors who never took part in any training more often agreed compared to other groups to two items (item B12: the RMN fleet establishes the topics of training programmes and seminars based on its qualified members and external experts and item D6: when communicating with others, I will give others time to think about what we just discussed). For item A8 (the RMN fleet follows a systematic plan to rotate its staff in all departments), sailors who had training twice or more found it difficult to agree. The RMN fleet personnel who had more training found it easy to agree with items A3 (my colleagues and I will actively share life or work experience with each other) and A4 (I gather information from other departments), showing that networks based on knowledge and service enabled them to share something.

5. Discussion

This study initially measured item difficulty in all modes of the knowledge creation process. Among four dimensions of the knowledge creation process, externalization (tacit to explicit knowledge conversion) and combination (explicit to explicit knowledge conversion) modes were perceived by the respondents as being difficult to conduct. A study by Muthuveloo et al. (Citation2017) indicated that socialization and internalization modes contributed significant influences as compared to externalization and combination modes in tacit knowledge management for organizational performance. This is assumed to be due to both externalization and combination modes being considered more formal processes utilizing, for instance, prepared visuals, documentation, or other forms of formal media. However, according to Little and Deokar (Citation2016), the utilization and expansion of knowledge in organizations relies on both formal and informal processes via effective communication.

The RMN fleet personnel participation in knowledge creation processes was measured as moderate, and this signifies the need for encouraging, motivating, and inspiring them to get heavily involved since they are the backbone of the RMN. Two demographic details – type of ship and number of times involved in training—were identified as producing interesting findings. Personnel serving on board the MPCSS were more active in knowledge creation processes as compared to the sophisticated corvette and frigate. The researchers surmise that personnel on board MPCSSs have a sense of inferiority when compared to those who serve aboard combat vessels, which makes them more active in knowledge creation processes. It is assumed that their mentality, attitudes, and perceptions changed in order to be at par with personnel who serve on board warships. It is also presumed that the selected personnel on board the combat vessels thought that they were well equipped with knowledge, hence making them less active in knowledge creation processes. However, there is no study or empirical evidence with regard to this except for issues on competency which have been brought up in board of inquiry (BOI) reports regarding recent mishaps involving collisions and fires on board frigates (CN feedback on BOI Report dated 12 Sep 2014 & 14 Nov 2017). On the other hand, a study by Ahmad et al. (Citation2011) indicated that personnel with various backgrounds in technologies such as those found on board sophisticated corvettes or frigates are supposed to be more technology savvy as compared to those serving aboard MPCSSs. However, in this study, the researchers found the opposite was true. This could be due to technology may be used to enable or oppress personnel at work (Coovert & Thompson, Citation2014). Personnel aboard MPCSS adopted the former in order for them to compete for their recognition and not to be underestimated. However, they must have had some foundation in technology because according to Cascio and Montealegre (Citation2016), only competent personnel is likely to experience less anxiety when new technology is introduced.

Meanwhile, the number of times in training influences changes in perceptions and attitudes towards the relevant processes. Greater amounts of training make personnel more active in knowledge creation processes. Training is conducted and attended by the RMN fleet personnel for their specialization and knowledge enhancement. Kaba and Ramaiah (Citation2017) found significant differences in specialisation and experience in the usage of knowledge creation tools. The increased levels of specialisation and experience resulting from the number of times in training caused personnel to more actively involve themselves in knowledge creation processes.

Based on DIF analysis, three demographic details were associated with significantly different responses to knowledge creation items. These were job position, type of ship and number of times in training. In relation to job position, where the management is divided into senior, middle, and lower levels, the military ranks of personnel are reported for every level of management, as mentioned in the sampling procedure. In this analysis, senior management, which comprised mostly officers, senior officers and heads of departments, tended to disagree about cases where others did not understand them and they needed to explain things. The finding indicates that most probably instructions, commands, or directives are given by them in one-way communication. The researchers assume that as upper managers, they expected that subordinates would need to have their own initiative to seek information or advice in finding answers pertaining to the orders and not be spoon fed, as this is a norm in military organization. However, Kaba and Ramaiah (Citation2017) posited that academic qualification, job position, or length of service do not implicate knowledge creation. Therefore, job position should not have any impact on the level of performance and productivity.

On the other hand, the middle- and lower-level management personnel tended to disagree about whether involvement in joint operations/exercises would support their knowledge through face-to-face interaction and on the aspect of experts being invited to share their experiences. This could be due to limited opportunities for having face-to-face meetings with members of other agencies or services, and this is assumed to be the same regarding experts. Nevertheless, as a high-reliability organization, the RMN fleet, while striving to maintain reliable performance, is susceptible to experiencing unwanted hazard, and thus needs to maintain high levels of performance and efficiency (Milosevic et al., Citation2015). Hence, in order to maintain reliable performance, the RMN fleet has specific standard operating procedures for operations, extensive training, briefing and debriefing, and audits and inspections to ensure the highest standards for the fleet.

Under the type of ship category, different platforms gave different and interesting responses. Personnel on board MPCSS tended to have discussions, sharing and facilitating knowledge creation processes more as compared to the combat ships. These activities are generally accepted as key to knowledge management effectiveness (Agyemang et al., Citation2016), which is beneficial to the organization. On the other hand, corvette and frigate personnel were found to have interacted more with many new concepts. This is because the personnel of combat vessels always keep themselves up to date with procedures and policies regarding maritime warfare scenarios and maritime rules and regulations. Comparatively, corvettes are the most effective among platforms in producing reports, thus generating new knowledge.

As for the number of times in training, responses showed personnel without training tended to agree that training programme should be tailored and that time was needed for discussion. A systematic plan for rotating personnel within departments, on the other hand, was strongly disagreed to by personnel with more experience in training. However, they were in common agreement on sharing experiences and gathering information as this networking enabled the personnel in sharing their valuable knowledge.

6. Conclusion

This study investigated personnel responses to questionnaire items and differences between their demographic profiles through analyses utilizing the SECI knowledge creation process model. The study found that the socialization and internalization modes of the knowledge creation process are easier to integrate within the RMN fleet than the externalization and combination modes. This reflects that tacit to tacit knowledge conversion via formal and informal interactions and explicit to tacit knowledge conversion by studying all documentation available within the fleet (learning by doing what is stipulated in documents) are more common. This knowledge conversion is deemed to be more informal as compared to the externalization and combination modes.

The level of participation in knowledge creation processes is identified as not unified within the fleet. Some types of ship will have more active personnel in participating and some not. This is a problem that needs to be addressed since the management of this knowledge is important in ensuring the effectiveness of the organization (Agyemang et al., Citation2016). Training has been identified as a factor in motivating fleet personnel to be actively involved in knowledge creation processes by changing their mindset, attitudes, perceptions, and opinions toward these processes.

The study also found that most of the RMN fleet personnel participate at a moderate level in knowledge creation processes. This needs to be looked into further since a sophisticated fleet with state-of-the-art inventories worth billions has many stakeholders concerned with safeguarding the sovereignty of the nation’s maritime interests. Hence, this study achieved its objectives of identifying the current extent of knowledge creation processes in the RMN fleet and as a high-reliability organization, with zero tolerance for any incidents or mishaps, the RMN fleet needs to be always vigilant and well prepared for any unforeseen circumstances in conducting operations.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shaftdean Lufty Rusland

Shaftdean Lufty Rusland, a Doctor of Management candidate, Noor Ismawati Jaafar, an Associate Professor and Deputy Dean (Research & Development) and Bambang Sumintono, a Senior Lecturer in University of Malaya, Malaysia, collaborated together to investigate knowledge creation process in the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) fleet since 2018. The study is intended to gauge the extent of knowledge creation process within the fleet and to propose a framework in knowledge creation enhancement process, to further improve the performance of the fleet. This is achieved by utilizing and enhancing existing knowledge creation process model with the hope of generalizing it to other establishments within the RMN, the other Malaysian Armed Forces’ services and perhaps to other sectors regardless public or private sectors in Malaysia. This article is the first contribution practically and theoretically, to the named stakeholders, and subsequent initiatives and articles will follow to further contribute to an under-researched study, especially in the military context in Malaysia.

References

- Adams, D., Mabel, H. J. T., Sumintono, B., & Siew, P. O. (2020). Blended learning engagement in public and private higher education institutions: A differential item functioning analysis of students’ backgrounds. Malaysian Journal of Learning & Instruction, 17(1), 133–25. http://mjli.uum.edu.my/images/vol.17no.2jan2020/133-158.pdf

- Agyemang, F. G., Dzandu, M. D., & Boateng, H. (2016). Knowledge sharing among teachers: The role of the big five personality traits. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 46(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-12-2014-0066

- Ahmad, M., Bakar, J. A. A., Yahya, N. I., Yusof, N., & Zulkifli, A. N. (2011). Effect of demographic factors on knowledge creation processes in learning management system among postgraduate students [Paper presented]. 2011 IEEE Conference on Open Systems (ICOS2011), Langkawi, Malaysia.

- Allal-Chérif, O., & Makhlouf, M. (2018). Using serious games to manage knowledge: The SECI model perspective. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1539–1543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.013

- Amayah, A. T. (2013). Determinants of knowledge sharing in a public sector organization. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(3), 454–471. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-11-2012-0369

- Amber, Q., Ahmad, M., Khan, I. A., & Hashmi, F. A. (2019). Knowledge sharing and social dilemma in bureaucratic organizations: Evidence from public sector in Pakistan. Cogent Business & Management (2019), 6: 1685445. http://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1685445

- Anderson, J. R. (1983). The architecture of cognition. Harvard University Press.

- Baldé, M., Ferreira, A., & Maynard, T. (2018). SECI driven creativity: The role of team trust and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(8), 1688–1711. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2017-0241

- Bandera, C., Keshtkar, F., Bartolacci, M., Neerudu, S., & Passerini, K. (2017). Knowledge management and the entrepreneur: Insights from Ikujiro Nonaka’s dynamic knowledge creation model (SECI). International Journal of Innovation Studies, 1(3), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijis.2017.10.005

- Bereiter, C. (2002). Education and mind in the knowledge age. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bhatt, G. D. (2000). Organizing knowledge in the knowledge development cycle. Journal of Knowledge Management, 4(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270010315371

- Boland, R. J., & Tenkasi, R. V. (1995). Perspective making and perspective taking in communities of knowing. Organization Science, 6(4), 350–372. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.4.350

- Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2015). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (3rd ed. ed.). Routledge.

- Boone, W. J., Staver, J. R., & Yale, M. S. (2014). Rasch analysis in the human sciences. Springer.

- Boone, W. J., Townsend, J. S., & Staver, J. R. (2016). Utilizing multifaceted Rasch measurement through FACETS to evaluate science education data sets composed of judges, respondents, and rating scale items: An exemplar utilizing the elementary science teaching analysis matrix instrument. Science Education, 100(2), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21210

- Bose, R. (2004). Knowledge management metrics. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 104(6), 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570410543771

- Bryant, S. (2005). The impact of peer mentoring on organizational knowledge creation and sharing: An empirical study in a software firm. Group and Organization Management, 30(3), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601103258439

- Canonico, P., De Nito, E., Esposito, V., Iacono, M. P., & Consiglio, S. (2019). Knowledge creation in the automotive industry: Analysing obeya-oriented practices using the SECI model. Journal of Business Research, 112 (May 2020), 450-457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.047

- Cascio, W. F., & Montealegre, R. (2016). How technology is changing work and organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 349–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062352

- Cavusgil, T., Calantone., S., & Zhao, Y. (2003). Tacit knowledge transfer and firm innovation capability. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 18(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620310458615

- Chen, Y., Liu, Z.-L., & Xie, Y. B. (2012). A knowledge-based framework for creative conceptual design of multi-disciplinary systems. Computer-Aided Design, 44(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cad.2011.02.016

- Chief of Navy (CN) feedback on Board of Inquiry (BOI) report. Retrieved Sep 12, 2014, from MTL/NTAD(SEK-UND)/4418/5 - (12) file in the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) Headquarters (HQ), Kuala Lumpur.

- Chief of Navy (CN) feedback on Board of Inquiry (BOI) report. MTL(N1-2).500-2/15/29 –(5). Retrieved Nov 14, 2017, from MTL(N1-2).500-2/15/29 - (5) file in the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) Headquarters (HQ), Kuala Lumpur.

- Choi, Y. (2016). The impact of social capital on employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior: An empirical analysis of US federal agencies. Public Performance & Management Review, 39(2), 381–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1108795

- Chong, S. C., Salleh, K., Ahmad, S. N. S., & Sharifuddin, S. I. S. O. (2011). KM implementation in a public sector accounting organization: An empirical investigation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(3), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271111137457

- Collins, H. (2010). Tacit and explicit knowledge. The University of Chicago Press.

- Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2014). Business research: A practical guide for graduate & undergraduate students (4th ed.). Palgrave MacMillan Higher Education.

- Coovert, M. D., & Thompson, L. F. (2014). Toward a synergistic relationship between psychology and technology. Chapter 1 (pg 1) in The psychology of workplace technology. New York: Routledge. ebook ISBN 9780203735565

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage Publication Inc.

- Curley, A., McClure, G., Spence, D., & Craig, S. (2002). The new NHS: Modern, definable? A questionnaire to assess knowledge of, and attitudes to, the new NHS. Clinician in Management, 11(1), 15–23. ISSN Print: 0965-5751

- Davenport, T., & Prusak, L. (2000). Working knowledge ((2nd ed.). Harvard Business Press.

- Earl, M. (2001). Knowledge management strategies: Toward a taxonomy. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045670

- Easa, N. F. H. (2012). Knowledge management and the SECI model: A study of innovation in the Egyptian banking sector. Stirling Management School, University of Stirling.

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. R. (2008). Management research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publication Ltd.

- Engelhard, G., Jr. (2013). Invariant measurement: Using Rasch models in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Routledge.

- Esterhuizen, D., Schutte, C. S., & Du Toit, A. S. A. (2012). Knowledge creation processes as critical enablers for innovation. International Journal of Information Management, 32(4), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2011.11.013

- Fisher, W. P. J. (2007). Rating scale instrument quality criteria. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 21(1), 1095. http://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt211m.htm

- Garvey, B., & Williamson, B. (2002). Beyond knowledge management: Dialogue, creativity and the corporate curriculum (1st ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Garvin, D. A. (1993). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 71(4), 78–91. https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

- Gonzalez, R., & Melo, T. (2018). Innovation by knowledge exploration and exploitation: An empirical study of the automotive Industry. Gest. Prod., São Carlos, 25(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-530X3899-17

- Gourlay, S. (2006). Conceptualizing knowledge creation: A critique of Nonaka’s theory. Journal of Management Studies, 43(7), 1415–1436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00637.x

- Grant, K., & Grant, C. (2008). The knowledge management capabilities of the major Canadian financial institutions. The international Conference on Knowledge Management.

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122. Special issue: Knowledge and the firm (winter, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171110

- Grimsdottir, E., Edvardsson, I. R., & Durst, S. (2019). Knowledge creation in knowledge-intensive small and medium sized enterprises. International Journal Knowledge-Based Development, 10(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKBD.2019.098236

- Hamel, G. (1991). Competition for competence and inter-partner learning within international strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12(S1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120908

- Hansen, M. T., Nohria, N., & Tierney, T. (1999). What’s your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business Review, 77(2), 1999. In Knowledge management: Critical perspectives on business and management (vol 3). Routledge: London and New York.

- Hargreaves, D. H. (1999). The knowledge-creating school. British Journal of Educational Studies, 47(2), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.00107

- Huang, Y., Basu, C., & Hsu, M. K. (2010). Exploring motivation of travel knowledge sharing on social network sites: An empirical investigation of U.S. college students. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 19(7), 717–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2010.508002

- Hubers, M., Poortman, C., Schildkamp, K., Pieters, J., & Handelzalts, A. (2016). Opening the black box: Knowledge creation in data teams. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 1(1), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-07-2015-0003

- Inkpen, A. C. (1996). Creating knowledge through collaboration. California Management Review, 39(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165879

- Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in organizations: A conceptual framework. Human Resource Development Review, 2(4), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484303257985

- Jogulu, U. D., & Pansiri, J. (2011). Mixed methods: A research design for management doctoral dissertations. Management Research Review, 34(6), 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171111136211

- Kaba, A., & Ramaiah, C. K. (2017). Demographic differences in using knowledge creation tools among faculty members. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(4), 857–871. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-09-2016-0379

- Kalpic, B., & Bernus, P. (2006). Business process modeling through the knowledge management perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management, 10(3), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270610670849

- Kari, J. (2009). Informational uses of spiritual information: An analysis of messages reportedly transmitted by extraphysical means. Journal of Information Science, 35(4), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551508101860

- Karim, N. S. A., Razi, M. J. M., & Mohamed, N. (2012). Measuring employee readiness for knowledge management using intention to be involved with KM SECI processes. Business Process Management Journal, 18(5), 777–791. https://doi.org/10.1108/14637151211270153

- Kianto, A., Vanhala, M., & Heilman, A. (2016). The impact of knowledge management on job satisfaction. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(4), 621–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2015-0398

- Kim, S., & Lee, H. (2006). The impact of organizational context and information technology on employee knowledgesharing capabilities. Public Administration Review, 66(3), 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.2006.66.issue-3

- Koskinen, K., & Vanharanta, H. (2002). The role of tacit knowledge in innovation processes of small technology companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 80(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(02)00243-8

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. SAGE Publishing.

- Lahti, R. K., Darr, E. D., & Krebs, V. E. (2002). Developing the productivity of a dynamic workforce: The impact of informal knowledge transfer. Journal of Organizational Excellence, 21(2), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/npr.10015

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situating learning in communities of practice. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 63–82). American Psychological Association.

- Li, M., Liu, H., & Zhou, J. (2018). G-SECI model-based knowledge creation for CoPS innovation: The role of grey knowledge. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(4), 887–911. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2016-0458

- Linacre, J. M. (2013). A user’s guide to winsteps ministeps Rasch-model computer programs. [version 3.74.0]. winsteps.com (by John M. Linacre) http://www.winsteps.com/index.htm

- Little, T. A., & Deokar, A. V. (2016). Understanding knowledge creation in the context of knowledge-intensive business processes. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(5), 858–879. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2015-0443

- Mafabi, S., Nasiima, S., Muhimbise, E. M., Kaekende, F., & Nakiyonga, C. (2017). The mediation role of intention in knowledge sharing behaviour. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 47(2), 172–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-02-2016-0008

- Manuri, I. (2012). Knowledge management in the Malaysian armed forces: A study on perceptions and applications in the context of an information and communication technology environment [The Doctoral Research Abstracts]. IPSis Biannual Publication, 2 (2).Institute of Graduate Studies, UiTM.

- Massingham, P. (2014). An evaluation of knowledge management tools: Part 1 – Managing knowledge resources. Journal of Knowledge Management, 18(6), 1075–1100. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2013-0449

- Mehralian, G., Nazari, J. A., & Ghasemzadeh, P. (2018). The effects of knowledge creation process on organizational performance using the BSC approach: The mediating role of intellectual capital. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(4), 802–823. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2016-0457

- Memon, S. B. (2015). Relationship between organizational culture and knowledge creation process in knowledge-intensive banks. Queen Margaret University.

- Milosevic, I., Bass, A. E., & Combs, G. M. (2015). The paradox of knowledge creation in a high-reliability organization: A case study. Journal of Management, 44(3), 1174–1201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315599215

- Muthuveloo, R., Shanmugam, N., & Teoh, A. P. (2017). The impact of tacit knowledge management on organizational performance: Evidence from Malaysia. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(4), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.07.010

- Nielsen, & Razmerita. (2014). Motivation and knowledge sharing through social media within Danish organizations. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, 429 (TDIT 2014), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-43459-8_13

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organization knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 1–118. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

- Nonaka, I., Kodama, M., Hirose, A., & Kohlbacher, F. (2014). Dynamic fractal organizations for promoting knowledge-based transformation – A new paradigm for organizational theory. European Management Journal, 32(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.02.003

- Nonaka, I., & Konno, N. (1998). The concept of ‘ba’: Building foundation for knowledge creation. California Management Review, 40(3), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165942

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995a). The knowledge-creating company. How Japanese companies foster creativity and innovation for competitive advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995b). The knowledge-creating company. How Japanese companies create dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H., & Umemoto, K. (1996). A theory of organizational knowledge creation. International Journal of Technology Management, 11(7–8), 833-845. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.1996.025472

- Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., & Konno, N. (2000). SECI, Ba and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(99)00115-6

- Oskouei, A. G. (2013). Investigation of knowledge management based on Nonaka and Takeuchi model in Mashhad municipality [Doctoral dissertation]. Eastern Mediterranean University.

- Pentland, B. T. (1995). Information systems and organizational earning: The social epistemology of organizational knowledge systems. Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, 5(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-8022(95)90011-X

- Popadiuk, S., & Choo, C. W. (2006). Innovation and knowledge creation: How are these concepts related? International Journal of Information Management, 26(4), 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2006.03.011

- Razmerita, L., Kirchner, K., & Nabeth, T. (2014). Social media in organizations: Leveraging personal and collective knowledge processes. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 24(1), 74–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10919392.2014.866504

- Rouquette, A., Hardouin, J.-B., Vanhaesebrouck, A., Sébille, V., Coste, J., & Christensen, K. B. (2019). Differential Item Functioning (DIF) in composite health measurement scale: Recommendations for characterizing DIF with meaningful consequences within the Rasch model framework. PLoS ONE, 14(4), e0215073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215073

- Ryle, G. (1949). The concept of mind. Hutchinson.

- Salisbury, M. (2008). From instructional systems design to managing the life cycle of knowledge in organizations. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 20(3–4), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.20007

- Salleh, K. M., & Sulaiman, N. L. (2016). Malaysian HRD practitioners’ competencies in manufacturing and non-manufacturing sector: An application of the competency model. Man In India, 96(4), 1169–1179.

- Sankowska, A. (2013). Relationships between organizational trust, knowledge transfer, knowledge creation and firm’s innovativeness. Learning Organization, 20(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696471311288546

- Schaap, H., De Bruijn, E., Van der Schaaf, M. F., & Kirschner, P. (2009). Student’s personal professional theories in competence-based vocational education: The construction of personal knowledge through internalization and socialization. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 61(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820903230999

- Sekaran, U. (2013). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. Wiley.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Shahzad, K., Siddiqi, A. F., Ahmid, F., Bajwa, S. U., & Sultani, A. R. (2016). Integrating knowledge management (KM) strategies and processes to enhance organizational creativity and performance: An empirical investigation. Journal of Modelling in Management, 11(1), 154–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-07-2014-0061

- Sikombe, S., Phiri, M. A., & Wright, L. T. (2019). Exploring tacit knowledge transfer and innovation capabilities within the buyer–supplier collaboration: A literature review. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1683130. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1683130

- Sondergeld, T. A., & Johnson, C. C. (2014). Using Rasch measurement for the development and use of affective assessments in science education research. Science Education, 98(4), 581–613. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21118

- Sumintono, B., & Widhiarso, W. (2014). Aplikasi model Rasch untuk penelitian ilmu-ilmu sosial (Rev ed.). Trimkom Publishing House.

- Swap, W., Leonard, D., Shields, M., & Abrams, L. (2001). Using mentoring and storytelling to transfer knowledge in the workplace. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045668

- Tsai, M. T., & Huili, Y. (2007). Knowledge creation process in new venture strategy and performance. Journal of Business Research, 60(4), 371–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.10.003

- Tsoukas, H., & Mylonopoulos, N. (2004). Introduction: Knowledge construction and creation in organizations. British Journal of Management, 15(S1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2004.t01-2-00402.x

- Tsoukas, H., & Vladimirou, E. (2001). What is organizational knowledge? Journal of Management Studies, 38(7), 973–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00268

- Van Zile-Tamsen, C. (2017). Using Rasch analysis to inform rating scale development. Research in Higher Education, 58(8), 922–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9448-0

- Von Krogh, G., Ichijo, K., & Nonaka, I. (2000). Enabling knowledge creation: How to unlock the mystery of tacit knowledge and release the power of innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Warkentin, M., Bapna, R., & Sugumaran, V. (2001). E-knowledge networks for inter-organizational collaborative E-business. Logistics Information Management, 14(1/2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1108/09576050110363040

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sense-making in organizations. Sage Publications.

- Willem, A., & Buelens, M. (2007). Knowledge sharing in public sector organizations: The effect of organizational characteristics on interdepartmental knowledge sharing. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(4), 581–606. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mul021

- Wong, K. Y., Tan, L. P., Lee, C. S., & Wong, W. P. (2013). Knowledge management performance measurement: Measures, approaches, trends and future directions. Information Development, 31(3), 239-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666913513278

- Yang, J., Roy, S., & Goel, V. (2020). Who engages in explicit knowledge creation after graduation? Evidence from the alumni impact survey of a large Canadian public university. Studies in Higher Education, 1–15. ISSN: 0307-5079 (Print) 1470-174X (Online). https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1732907

- Yeh, Y. C., Huang, L. Y., & Yeh, Y. L. (2011). Knowledge management in blended learning: Effects on professional development in creativity instruction. Computers and Education, 56(1), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.011

- Zhang, J., & Dawes, S. S. (2006). Expectations and perceptions of benefits, barriers, and success in public sector knowledge networks. Public Performance & Management Review, 29(4), 433–466. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2006.11051880

- Zhang, W., & Zhang, W. (2018). Knowledge creation through industry chain in resource-based industry: Case study on phosphorus chemical industry chain in western Guizhou of China”. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(5), 1037–1060. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-02-2017-0061