?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study clarifies consumers’ defense mechanisms and message elaboration to highlight the connection between consumer engagement with messages and brand success. Two eye-tracking experiments tested whether skepticism toward companies’ cause-related marketing (CRM) initiatives would lead to wide variations in how CRM ads influence consumers’ message elaboration. Informational appeals discouraged highly skeptical consumers’ message elaboration; thus, they process information through heuristic cues, such as “likes” and followers. However, negative emotional appeals led consumers to process information in a more accommodative and systematic manner. Moreover, the degree of message elaboration on heuristic cues (Study 1) and images (Study 2) has a crucial mediating role in the CRM appeal effect on credibility judgment. This study addresses the existing research gab by examining how dispositional CRM skepticism guides consumer message elaboration.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study examines whether emotional messaging and peripheral cues can curb the negative effects of consumer skepticism on cause-related marketing communication. Although cause-related marketing practices are vulnerable to the negative effect of skepticism, there is little guidance on how cause- related marketing messages are transmitted without being deconstructed for their credibility by consumers who demand transparency. Moreover, there is little guidance on how different strategies affect processing engagement and important brand outcomes, such as driving traffic to brand locations. This study addressed this gap and secures an obvious link between skepticism, message elaboration, and message credibility, illustrating that consumers’ level of cause-related marketing skepticism controls the extent to which they are likely to be defensive against detailed advertisement information. The study highlighted that given that skepticism results in low levels of information processing regarding a company’s cause-related marketing, understanding the contextual appeal to use on social media will help marketers enhance skeptical consumer engagement with their brand pages and build consumer relationships.

1. Introduction

A company’s performance is increasingly judged based on its societal impact. This situation encourages the incorporation of organizational chairty and fundraising activities through consumer engagement, which is known as cause-related marketing (CRM) (Chernev & Blair, Citation2015). Companies evolve their CRM communications to be engaging through social networking sites (SNSs), encouraging consumers to join their brand pages (Andersen & Johansen, Citation2016). Consumers today can incorporate and multiply brand messages, which facilitates enormous viral effects, such as favorable attitudes toward cause marketing campaigns and brands (Brodie et al., Citation2011; Dessart et al., Citation2015; Knoll, Citation2016). Therefore, motivating consumers to further engage with a brand page has significant relevance for businesses in marketing communication today.

However, such a CRM strategy is bound to backfire on the company; consumers often perceive the alignments with non-profits as a marketing ploy (Szykman et al., Citation2004). Moreover, the gap between the promotion budget allocated for advertisement and the final donation leads consumers to devalue CRM communications and interpret these messages as insincere (Skarmeas & Leonidou, Citation2013). Skeptical consumers may become passively involved by detaching themselves from CRM messages; thus they fail to engage with message elaboration (Obermiller et al., Citation2005). Given that attentional information processing and message elaboration are crucial determinants in decision-making (Guerreiro et al., Citation2015; Ketelaar et al., Citation2017), increasing skeptical consumers’ processing level is an important communication objective for marketers.

Although CRM practices are vulnerable to the negative effect of skepticism, there is little guidance on how CRM messages are transmitted without being deconstructed for their credibility by consumers who demand transparency and how different strategies affect processing engagement and, ultimately, important brand outcomes such as driving traffic to brand locations on and offline (Ashley & Tuten, Citation2014).

Thus, this study enhances the field’s understanding of curbing the negative effects of CRM skepticism on Facebook brand pages. To better understand how to buffer consumer negative evaluations, this study identifies and tests the cognitive mechanisms underlying message elaboration using eye movement data captured by an eye-tracking device; monitored visual attention has been considered a crucial indicator of the level of message elaboration (Pieters et al., Citation2010). Study 1 provides initial evidence to support the assertion that the detrimental effects of consumer skepticism toward CRM ads can be lessened through emotional messaging and heuristic cues. Study 2 replicated Study 1 with different informational and emotional CRM claims on a Facebook brand page. Moreover, the second study explored whether the amount of attention paid and the level of information processing depends on the positive or negative emotional effect.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. CRM skepticism

Consumer CRM skepticism is defined as a consumer’s tendency to distrust cause-related marketing actions or messages (Singh et al., Citation2009; Webb & Mohr, Citation1998). Consumers utilize their knowledge of marketing tactics to interpret and evaluate such actions and messages. Thus, consumers acquire more knowledge and develop coping strategies, such as skepticism, to evaluate specific claims made by companies engaged in CRM (Friestad & Wright, Citation1994). Hence, these consumers are more resistant to marketing persuasion tactics and rarely believe company claims (Forehand & Grier, Citation2003).

A well-known CRM strength is the direct relationship between a company, cause, and consumer as the consumer’s product purchase leads to cause-benefiting donations. However, if consumers feel mislead, they react with skepticism regarding sincerity and commitment (Bae, Citation2018; Gupta & Pirsch, Citation2006; Odou & Perchpeyrou, Citation2011). This skepticism is rooted in the fact that the relationship between the consumer and the charity is indirect; the company benefits first before any obligation to donate is accrued (Dean, Citation2004). Therefore, consumers may perceive CRM as exploitation of charity for self-interest rather than altruism (Dean, Citation2004). The contradiction between a for-profit company and a CRM amplifies CRM skepticism (Szykman et al., Citation2004). The discrepancies between the budget allocated to promote the campaign and the final donation also intensify consumers disbelief of CRM claims (Preston, Citation2011; Yoon et al., Citation2006). Consequently, consumers may view a CRM claim as just another promotional tactic to manipulate them (Odou & Perchpeyrou, Citation2011; Webb & Mohr, Citation1998). Thus, initially spiked good publicity can quickly reverse due to consumers’ perceptions of the companies as exploiters of causes and charities (Barone et al., Citation2000).

2.2. Skepticism and emotional appeals

While CRM offers can trigger consumer skepticism, selecting the best appeal type might lessen this impact. Previous studies have found that the extent of consumers’ CRM skepticism is important based on their responses to emotional and informational appeals (Obermiller et al., Citation2005) An informational CRM appeal is designed to appeal to the intellect by using detailed information about a sponsoring company’s socially responsible behavior and its benefits to a specific social cause (Matthens et al., Citation2014). However, an emotional CRM appeal communicates emotionally appealing contents, such sad images of needy persons or a story highlighting how the initiative enhanced the needy person’s life (Guerreiro et al., Citation2015; Small & Verrochi, Citation2009).

According to the dual-process models, message elaboration refers to the extent to which a person carefully scrutinizes an ad message (Chaiken & Trope, Citation1999; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1981). Message elaboration has been linked to information processing motives grounded in a desire to acquire and share information (Rubin, Citation1993). Highly skeptical consumers may not engage with the information presented by marketers (Darke & Ritchie, Citation2007). Therefore, the failure to engage in message elaboration is a predictable defense mechanism that triggers a detachment from the persuasive message (Friestad & Wright, Citation1994). Thus, emotional appeals may be more convincing for skeptical consumers than informational appeals (Bae, Citation2019; Matthes & Wonneberger, Citation2014; Obermiller & Spangenberg, Citation1998).

Skeptical consumers’ detachment from the CRM message may be explained by the cognitive avoidance model (Hock & Krohne, Citation2004), which posits that skeptical consumers tend to avoid persuasive communications containing messages that contradict their existing beliefs and are, therefore, more inclined to avoid informational messages than emotional ones. Considering this informational message avoidance tendency, several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of emotional appeals. Kanter and Wortzel (Citation1985) suggested that since skepticism originated from disbelief in a company’s sincerity, an emotional touch rather than extensive information might be more effective in convincing consumers. Similarly, Matthes and Wonneberger (Citation2014) found that emotional appeals curbed CRM skepticism. Thus, an emotional appeal might alleviate the low level of message elaboration (DeCarlo & Barone, Citation2009).

2.3. Skepticism and heuristic cues

When consumers process brand information online, they assign greater credibility to information verified by other web users. It is known as an endorsement heuristic, where consumers believe that something is correct if others think it is correct (Metzger & Flanagin, Citation2015). Sundar (Citation2008) also suggested that computer-generated content is perceived as free from bias; therefore, people trust machines more than humans as a source of information. Thus, likes and followers on SNSs may act as heuristic cues for people to deal with doubt (Westerman et al., Citation2012). Phua and Ahn (Citation2014) also found that followers could make a company appear more credible to consumers.

As a mechanism of information processing, an individual allocates his or her mental energy to incoming stimuli or media messages through visual attention (Perse, Citation1990). There are no noticeable gaps between what is seen and what is processed; eye fixation can be considered an indicator of intense cognitive processing (Rayner, Citation1998). Elaborate processing requires high levels of attention (Russo, Citation2011); thus, total fixation duration (TFD) is considered an indication of elaborate information processing.

Given that attention is a selection process, where some inputs are processed deeper than others, and is provoked by viewing motives (Perse, Citation1990), it may not make sense for highly skeptical consumers to select and scrutinize a plethora of untruthful messages concerning. Skeptical consumers may select and deeply engage in computer-generated content as a more reliable basis for their judgment by how others have verified and selected the contents on the company’s SNSs. Therefore, it would be reasonable to expect that when the brand’s SNS is full of information, highlighting the company’s CRM activities, highly skeptical consumers versus less skeptical consumers may pay more attention to those endorsement heuristic cues. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H1: When viewing an informational and an emotional CRM ad on a Facebook brand page, individuals with higher levels of skepticism will (a) exhibit shorter TFD on a text and (b) longer TFD on heuristic cues such as likes and followers.

H2: When viewing an informational and an emotional CRM ad on a Facebook brand page, individuals with lower levels of skepticism will (a) exhibit longer TFD on a text and (b) shorter TFD on heuristic cues such as likes and followers.

2.4. The mediating role of elaboration on message credibility

Message engagement, a state evoked by a particular message at a particular point in time (Laczniak et al., Citation1989), has been found to influence the consequences of message effects. When consumers became more involved in the content of companies, they considered them more credible and showed greater intention to purchase their product (Kim et al., Citation2009). Moreover, consumers who are more involved in processing advertising messages consider the message to be more believable (Wang, Citation2006). Westerman et al. (Citation2014) also found that the amount of cognitive elaboration Twitter users engaged in plays a significant role in mediating the effect of Twitter contents that update their credibility perception.

Visual attention research has also provided evidence of the effect of message engagement on attitude formation and behavioral intention. Guerreiro et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated that a higher duration of attention towards the cause-related target led consumers to donate to the charity cause. Moreover, perceived message credibility is a positive predictor of behavioral intention (Chang, Citation2011; Goldsmith et al., Citation2000).

Therefore, this study proposes that positive increases in consumer responses are a function of elaboration on the CRM message. Specifically, in an informational appeal, increased message credibility is due to the attention to heuristic cues, such as likes and followers, for highly skeptical consumers. Meanwhile, for less skeptical consumers, increased message credibility is due to the attention to central cues. Notably, the study predicted that this effect is conditional on CRM skepticism. Furthermore, this credibility perception will lead to greater intention to join the brand page and purchase the advertised product.

H3: The interaction effect of CRM ad appeals and skepticism on consumer perception of message credibility is mediated by (a) TFD on a text and (b) TFD on heuristic cues.

H4: A greater perceived message credibility will generate a stronger intention to (a) join the brand page and (b) purchase the advertised company’s product.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

A total of 215 undergraduate students at a large Midwestern university in the USA were recruited through an online SONA system: an online student participant pool. The participants received extra course credit as compensation for their participation. Students were selected as the sample because this demography is very responsive to cause marketing (Nielsen, Citation2016), shares social cause information on Facebook (Nielsen, Citation2014), and is homogeneous (Peterson, Citation2001).

Of the 215 participants, four were eliminated because of poor eye movement data, resulting in a total sample of 211: 113 females (53.6%) and 98 (46.4%) males aged 18 to 24, with a mean age of 19.81 (SD = 1.46). Most participants were Caucasian (65.9%), followed by Hispanic (9.5%) and Asian (7.6%). Participants’ demographic characteristics were insignificantly correlated with the dependent variables (all ps > 0.05).

3.2. Research design

To examine the effects of CRM ad appeal types on message elaboration and perceptual responses, a 2 (informational or emotional appeal type) × 2 (high or low CRM skepticism) between-subjects factorial design was employed.

3.3. Stimuli development

A fictitious non-profit organization (NPO) called “Hands for Hunger” was created as global consumers ranked poverty and hunger as the most concerning social cause (Nielsen, Citation2014). In selecting a company, fifty students (outside the main study) assessed the perceived congruence of the social cause with three companies: a food retail company (FOODBAG), a bottled water company (ICIS), and a running shoe company (LeCaf). FOODBAG was evaluated as the most compatible with the hunger cause (F(2, 48) = 48.02, p < 0.01).

3.4. Manipulations of appeal type

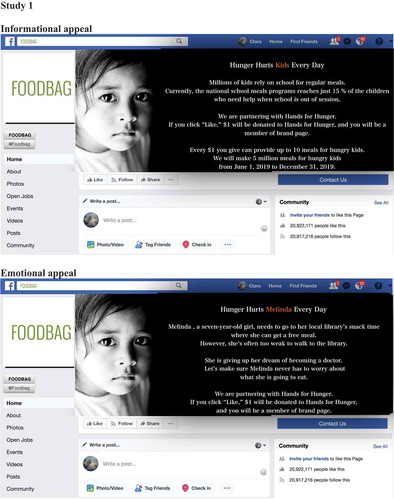

Since this study examines the effect of CRM on consumer intention to join a brand fan page and purchase company products, a Facebook page was created for FOODBAG.

In the emotional appeal, a seven-year-old girl, Melinda, was introduced. The headline, “Hunger Hurts Melinda Every Day,” was presented with a picture of a girl followed by a description of her situation (see Appendix 1). In the informational appeal, “Melinda” was replaced with “Kids” in the headline. The description presented general facts about the challenges faced by children in the U.S. Further details on the CRM initiative was added at the end of the description. Other factors, such as message sequence, visual image, and Facebook layout, were identical for the two conditions. The company’s likes and followers were featured on the bottom right of the page in both conditions.

Additional 67 undergraduate students confirmed a significant mean difference between the two conditions (Memotional = 5.87, SD = 0.59; Minformational = 3.57, SD = 0.89, F (1,66) = 34.40, p < 0.001 for an emotional condition; Minformational = 5.30, SD = 0.76; Memotional = 3.02, SD = 0.99, F (1,66) = 56.38, p < 0.001 for an informational condition), indicating that the manipulation was successful.

3.5. Procedure

The participants were invited to a laboratory and provided with an informed consent form. They were then guided to sit in front of a Tobii Pro 60 eye-tracking device, connected to a 22-inch LED monitor.

One condition was randomly presented to each participant, and participants’ eye movements while viewing the ad were recorded. After finishing the eye-tracking portion of the experiment, participants completed an online questionnaire via Qualtrics, which measured the appeal type manipulation check, their level of CRM skepticism, perceived message credibility, and their intention to join the brand page and purchase the advertised company’s product. Their demographic information was recorded. After the approximately 20 minutes experiment, the participants were debriefed and thanked.

3.6. Measures

Consumers’ CRM skepticism was assessed by a modified nine ad skepticism scale (Obermiller & Spangenberg, Citation1998) on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). High (M = 4.79, SD = 0.61) and low groups (M = 3.11, SD = 0.49) were distinguished based on the median value of 3.80. The TFD from the eye-tracking device measured the message elaboration. A fixation is a measure of eye position when the eyes rest for a brief moment and visual information is gathered (Wolfe & Horowitz, Citation2004). TFD is the length of the fixation (in seconds) for a CRM ad. Longer TFD indicates greater message elaboration. Thus, to produce the TFD data, two separate areas of interest (AOIs) regarding the text and heuristic cues were drawn.

Message credibility was measured using six items on a seven-point scale (MacKenzie & Lutz, Citation1989; Yoo & MacInnis, Citation2005). Intentions regarding joining the brand page were measured using three items on a seven-point scale developed by Muk and Chung (Citation2014). Purchase intention was measured using three items on a seven-point scale (Sen & Bhattacharya, Citation2001). Table provides an overview of all items, average variance extracted (AVE), construct reliability (CR) and factor loadings.

Table 1. Measurement scales, item loading, CR, and AVE

4. Results

4.1. Scale verification

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) evaluated the psychometric properties of the latent constructs using AMOS 22. Two items measuring CRM skepticism were eliminated due to poor factor loadings (e.g., “Companies pretend to care more about society than they really do” and “Most CRM messages from companies are intended to mislead consumers rather than inform them”). The loadings for the other latent constructs were statistically significant, and convergent validity was achieved. The CR suggests internal consistency ranging from 0.66 to 0.96, and the AVE of each construct exceeded the minimum criteria of 0.50, confirming convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). The /df ratio was below 2.0, and CFI, GFI, NFI, and TLI values exceeded the 0.90 threshold for model fit (McDonald & Marsh, Citation1990). All AVE estimates were larger than the squared pairwise correlations, thus confirming discriminant validity (Fornell & Larker, Citation1981). Table reports the correlations of the latent constructs.

Table 2. Construct correlations and AVE on diagonal

4.2. Manipulation check

An independent samples t-test demonstrated that the manipulation of the appeal type was successful (Minformational = 4.66, SD = 1.21, Memotional = 4.31, SD = 1.13, t (209) = 2.15, p < 0.05 for informational condition; Memotional = 4.89, SD = 1.26, Minformational = 4.02, SD = 1.52, t (209) = 4.46, p < 0.01 for emotional condition).

4.3. Hypotheses tests

4.3.1. Effect of CRM ad appeal on message elaboration

A two-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed a significant interaction effect between skepticism and ad appeal (Wilk’s = 0.85, F (2, 206) = 17.58, p < 0.001, partial = 0.15). A univariate analysis demonstrated that the interaction between skepticism and ad appeal was significant on the TFD regarding text (F (1, 207) = 14.69, p < 0.001, partial = 0.07) and peripheral cues (F (1, 207) = 18.97, p < 0.001, partial = 0.08). As predicted, when viewing an informational appeal, highly skeptical consumers give more attention to heuristic cues (M = 2.04, SD = 0.72) than to text (M = 1.99, SD = 0.52) (see Table ). They give more attention to central cue (i.e., text, M = 2.18, SD = 0.53) than to heuristic cues (M = 1.65, SD = 0.43) when processing emotional appeal. However, regardless of ad appeals, less skeptical consumers showed a greater elaboration on central cue (Minformatioanl = 3.12, SD = 0.84; Memotional = 2.64, SD = 0.56) than heuristic cues (Minformatioanl = 1.06, SD = 0.48; Memotional = 1.33, SD = 0.50). Hypotheses 1 and 2 were thus supported.

Table 3. Means and standard deviation of subjective elaboration and visual attention for high vs. low CRM skepticism

4.3.2. Moderated mediation analysis

The SPSS macro PROCESS (model 7) was applied for moderated mediation analysis (Hayes, Citation2013). This macro generates higher power and a lower Type 1 error (Hayes, Citation2013). The variables were centered to avoid potentially problematic high multicollinearity with the interaction term. The results demonstrated significant moderated mediation. Table specifies the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the conditional indirect effects of CRM ad appeals on message credibility through TFD on text and TFD on peripheral cues for high- and low- skepticism consumers (1 for informational appeal and 2 for emotional appeal).

Table 4. Moderated multiple mediation analysis, indirect effects on message credibility

The indirect effect of ad appeals on credibility through TFD on heuristic cues was significant for both highly and less skeptical consumers (βhigh = 0.11, SE = 0.05, 95% CI: 0.03 to 0.24, βlow = −0.07, SE = 0.03, 95% CI: −0.17 to −0.02). However, the indirect effect of ad appeals on credibility through TFD on text was insignificant for both types of consumers (βhigh = −0.01, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: −0.07 to 0.01, βlow = 0.03, SE = 0.04, 95% CI: −0.04 to 0.14). The index of moderated mediation was significant for TFD on heuristic cues (β = 0.18, SE = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.05 to 0.37). TFD on text was insignificant (β = −0.04, SE = 0.06, 95% CI: −0.20 to 0.06). For both types of consumers, the effect of CRM ad appeals on message credibility worked through TFD on heuristic cues. Therefore, H3b was supported.

4.3.3. Effect of perceived message credibility on intentions

To test the hypotheses, a general linear regression was conducted. The regression results demonstrated significant positive effects of message credibility on intention to join a brand page (β = 0.55, t = 8.35, p < 0.001, = 0.26) and purchase an advertised product (β = 0.61, t = 10.49, p < 0.001, = 0.36). These findings supported H4a and H4b.

5. Discussion

This study finds that when viewing an informational CRM communication, avoidance occurred during information processing for highly skeptical consumers regarding detailed information. However, high-skepticism consumers give more attention to central cues than peripheral cues when processing the emotional ad. Low-skepticism consumers, however, relied more on the central cue than peripheral cues regardless of the appeal. Moreover, message elaboration on heuristic cues was found to mediate the CRM effect on message credibility. This study also found that once consumers consider the CRM message to be credible, they are more likely to join the brand page and purchase a product.

6. Study 2

Study 2 was designed to validate Study 1 with a different sample and ascertain whether different emotional appeals (i.e., positive versus negative) draw highly skeptical consumers’ attention and message elaboration differently. Thus, this study extends the research on CRM skepticism by showing that a certain type of emotional appealing strategy can alleviate the negative effects of CRM skepticism.

6.1. Positive versus negative emotional appeals

Several studies have found that positive emotional appeals inhibit individuals’ abilities to carefully examine persuasive messages (Fiedler, Citation2001; Myers & Sar, Citation2015). For example, the mood-and-general-knowledge model (Bless, Citation2000) posits that, in a positive affective state, people are more likely to rely on existing schemas and stored general-knowledge structures. In a negative affective state, people are less likely to do so, resulting in increased attention to and retention of external information in a more accommodative, detailed, and systematic manner (Schwarz & Bless, Citation1992). Thus, when highly skeptical consumers encounter CRM messages that induce positive emotions, they may retrieve their existing persuasion knowledge and CRM skepticism, which in turn triggers reliance on heuristic information. However, when highly skeptical consumers are exposed to CRM campaigns that elicit negative emotions, they may systematically process central details from a CRM campaign. Homer and Yoon (Citation1992) have already asserted that negatively framed advertisements reduced the negative effect of skepticism on both ad attitudes and brand attitudes. Therefore, a needy person’s sad image and story may alleviate skeptical consumers’ resistance and facilitate their transition to information processing, which in turn generates greater message credibility and additional positive outcomes. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H5: Individuals with higher levels of skepticism will exhibit (a) a longer TFD on text, (b) a longer TFD on an image, and (c) a shorter TFD on heuristic cues when viewing a CRM ad with a negative rather than positive emotional appeal and an informational appeal.

H6: Individuals with lower levels of skepticism will exhibit (a) a longer TFD on text, (b) a shorter TFD on an image, and (c) a shorter TFD on heuristic cues when viewing a CRM ad regardless of the appeal type.

When a needy person expresses sadness, a viewer shares that pain; this emotional convergence of sadness facilitates further information processing, resulting in high charitable behavior (Baberini et al., Citation2015). As Study 1 found, a positive increase in consumer response is a function of attention and elaboration on the CRM message. For more skeptical consumers, attention to the text and the sad image may lead to greater message credibility. For less skeptical consumers, attention to central cues may enhance message credibility. Therefore, it is expected that CRM receptivity will work as follows:

H7: The interaction effect of CRM ad appeals and skepticism on consumer perception of message credibility is mediated by (a) TFD on text, (b) TFD on image, and (c) TFD on heuristic cues.

It has been found that more credible information alleviates consumer concerns that the company’s initial intention is in some way suspect (Campbell & Kirmani, Citation2000). Once consumers considered the sponsoring company to be more credible, they foavorably evaluated the comapany’s CRM ad on a Facebook brand page, resulting in greater intention to join the company’s brand page (Bae, Citation2018). Lin and Lu (Citation2010) also found that credibility motivates consumers to join brands’ Facebook fan pages. Joining a brand page featuring CRM may allow consummers to indirectly control the impression they give off simply by associating themselves with brand that is sponsoring the given cause (Bae, Citation2019) since supporting causes may provide them with an opportunity to demonstrate good citizenship behavior (Boyd & Ellison, Citation2007). Thus, consumers are likely to consider joining a Facebook brand page featuring CRM.

Previous studies have found that compared to nonmembers, members of Facebook brand pages spent more money on the brands for which they were members. For example, members of Starbucks’ Facebook page spend more and transact more frequently relative to nonmenbers (Lipsman et al., Citation2012). Manchanda et al. (Citation2015), demonstrated a significant increase in expenditures from customers that joined the company’s social network brand page. Given that credibility perception increases a consumer’s willingness to join a brand’s membership, which in turn lead to greater purchase intention, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H8: Intention to join the brand page will mediate the relationship between perceived message credibillity and intention to purchase the advertised company’s product.

7. Methods

7.1. Sampling

A total of 201 undergraduate students at a large Midwestern university in the USA were recruited through an online SONA system. The participants received extra course credit as compensation for their participation. Four were eliminated because of poor eye movement data, resulting in a total sample size of 197: 98 males (44.7%) and 109 females (55.3%) aged 19 to 29, with a mean age of 24.03 (SD = 2.74). Most participants were Caucasian (68.5%), followed by Hispanic (10.7%) and African American (7.1%). Participants’ demographic characteristics had no impact on the dependent variables (all ps > 0.05).

7.2. Research design

The experiment was a 3 (informational, positive emotional, or negative emotional appeal type) × 2 (high or low CRM skepticism) between-subjects factorial design.

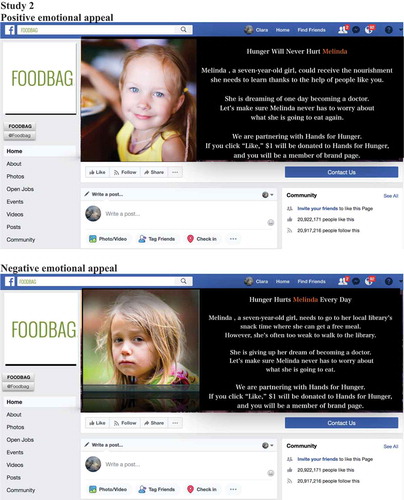

7.3. Manipulations of appeal type

The stimulus for the informational CRM ad was like that of the first study. For the positive appeal, the headline was replaced with “Hunger Will Never Hurt Melinda,” and a picture of a smiling girl was presented. The text was replaced with “Melinda, a seven-year-old girl, could receive the nourishment she needs to learn thanks to the help of people like you. She is dreaming of one day becoming a doctor.” Stimuli for the negative emotional CRM ad employed the same message content as that of Study 1, except the image of a girl (see Appendix 1).

To select positive and negative images, after selecting five images of girls per each condition by two research assistants, 50 participants (outside the main study) rated one image among the five positive images as the most positive (F(4, 46) = 11.08, p < 0.001) and another among the five negative images as the most negative (F(4, 46) = 9.23, p < 0.01).

7.4. Procedure and measurement

The experiment procedure and measures were like Study 1, except for a dependent measure. To ensure the effect of different image types on visual attention, one more AOI was drawn for the image. The rest of the scales and items were based on the measures used in the first study. Table reports the results of the CFA, including the scale items. Table reports the correlations of the latent constructs. All items had significant loadings on their respective constructs, confirming convergent validity. The χ2/df ratio was below 2.0 (χ2/df = 1.365), and all the goodness-of-fit indices were sufficient (CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.974, GFI = 0.901, NFI = 0.924, RMSEA = 0.042).

Table 5. Construct correlations and AVE on diagonal

All AVEs were greater than the squared interconstruct correlations, confirming discriminant validity.

8. Results

8.1. Manipulation checks

Participants exposed to the informational appeal rated significantly higher on the measure for informative and rationality (Minformational = 4.92, SD = 1.01; Mpositive = 2.55, SD = 0.54; Mnegative = 2.45, SD = 0.97, F(2, 194) = 389.89, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc tests, p < 0.001). Positive appeals were rated as most positive (Mpositive = 4.62, SD = 0.59; Mnegative = 2.46, SD = 0.66; Minformational = 2.67, SD = 0.78, F(2, 194) = 93.18, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc tests, p < 0.001), and negative appeals, most negative (Mnegative = 4.98, SD = 0.62; Mpositive = 3.14, SD = 0.71; Minformational = 3.91, SD = 0.83, F(2, 194) = 107.72, p < 0.001; Tukey post hoc tests, p < 0.001).

8.2. Hypothesis test

8.2.1. Effects of CRM ad appeal on message elaboration

Highly skeptical and less skeptical consumers were grouped based on median values (Median = 3.33; high (n = 98, M = 4.42, SD = 0.79), low (n = 99, M = 2.70, SD = 0.48). A two-way MANOVA demonstrated significant interaction effects between skepticism and CRM appeal (Wilk’s = 0.51, F (8, 376) = 18.86, p < 0.001,partial = 0.29). The effect of CRM appeal on the combined dependent variables is not the same for highly and less skeptical consumers, such as the main effects of CRM skepticism (Wilk’s = 0.58, F (4, 188) = 33.96, p < 0.001, partial

= 0.42) and CRM appeal (Wilk’s = 0562, F (8, 376) = 16.12, p < 0.001, partial

= 0.26).

Univariate results demonstrated interaction effects between skepticism and appeal types on a central cue (i.e., text) (F (2, 191) = 4.88, p < 0.01, partial = 0.05), image (F (2, 191) = 4.54, p < 0.05, partial

= 0.05), and heuristic cues (F (2, 191) = 7.32, p < 0.001, partial

= 0.07).

As Table illustrates, highly skeptical consumers paid greater attention to text when they viewed a negative compared to positive and informational appeals (Mnegative = 11.20, SD = 4.25; Mpositive = 10.23, SD = 2.61, Minformational = 9.13, SD = 3.59) (F (2, 191) = 4.88, p < 0.01, partial = 0.05). Therefore, H5a was supported. Negative images held highly skeptical consumers’ visual attention longer than informational and positive images (Mnegative = 7.25, SD = 3.30; Minformational = 4.97, SD = 3.11; Mpositive = 3.10, SD = 2.81) (F (2, 191) = 4.54, p < 0.05, partial

= 0.05). Thus, H5b was supported. Heuristic cues did not hold highly skeptical consumers’ attention for both negative (M = 0.89, SD = 0.44) and positive appeal (M = 0.83, SD = 0.48), unlike informational appeal (M = 1.28, SD = 0.72). However, the difference between negative and positive appeals was insignificant (p >.05). Thus H5 c was not supported.

Table 6. Means and standard deviation of subjective elaboration and visual attention for high vs. low CRM skepticism

Less skeptical consumers paid more attention to text (Minformational = 14.54, SD = 2.86; Mnegative = 13.55, SD = 3.58, Mpositive = 12.33, SD = 2.96) than heuristic cues (Minformational = 0.49, SD = 0.22; Mnegative = 0.63, SD = 0.45, Mpositive = 0.78, SD = 0.80) and image (Minformational = 1.44, SD = 2.30; Mnegative = 3.28, SD = 0.63, Mpositive = 2.02, SD = 2.11) regardless of the appeal type. Thus, H6 was supported.

8.2.2. Moderated mediation analysis

A macro PROCESS (model 7) was applied for moderated mediation analysis (Hayes, Citation2018) to test the moderated mediation hypothesis. Table illustrates the 95% CI of the conditional indirect effects of CRM ad appeals on message credibility through TFD on text, TFD on images, and TFD on heuristic cues for highly and less skeptical consumers (1 for informational appeal, 2 for positive appeal, 3 for negative appeal).

Table 7. Moderated multiple mediation analysis, indirect effects on message credibility

The conditional effects analysis demonstrated that the indirect effect of ad appeals on credibility through TFD on image was significantly positive among highly skeptical consumers (β = 0.28, SE = 0.07, 95% CI: 0.28 to 0.53) and less skeptical consumers (β = 0.27, SE = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.25 to 0.44). The indirect effect of ad appeals on credibility through TFD on text was insignificant for both types of consumer (βhigh = 0.03, SE = 0.03, 95% CI: −0.04 to 0.09, βlow = −0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI: −0.04 to 0.14). The indirect effect of ad appeals on credibility through TFD on heuristic cues was significantly negative among highly skeptical consumers (β = −0.20, SE = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.43), but insignificant for less skeptical consumers (β = −0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI: −0.04 to 0.14). The index of moderated mediation was significant for TFD on image (β = 0.18, SE = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.12). TFDs on text and heuristic cues were insignificant (βbody text = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI: −0.01 to 0.05, βheuristic cues = 0.02, SE = 0.07, 95% CI: −0.14 to 0.18). Therefore, H7b was supported, unlike H7a and H7 c.

8.2.3. The mediating role of intention to join the brand page

The mediating role of intention to join the brand page was tested with Model 4 of the PROCESS macro of Hayes (Citation2013). As predicted, each antecedent factor had significant effects on the subsequent factor (perceived message credibility intention to join a brand page, β = 0.55, t(195) = 8.35, p < 0.001; intention to join a brand page

intention to purchase advertised product, β = 0.51, t(194) = 7.59, p < 0.001). A bootstrap analysis with a 10,000 sample and a confidence level of 0.05 confirmed a positive (0.28) and significant (confidence interval: 0.18 to 0.40) indirect effect, supporting H8.

9. Discussion

Highly skeptical consumers were likely to pay more attention to message details and an image that primarily induces sadness. However, less skeptical consumers paid more attention to detailed CRM messages regardless of the appeal type. The second study found a significant mediating role of elaboration regarding an image, but the attention paid to text and heuristic cues did not mediate the effect of the appeal on credibility perception. Intention to join a brand page was found to mediate the effect of perceived message credibility on intention to purchase the advertised company’s product.

10. General discussion

This study hypothesized that skepticism toward companies’ CRM initiatives leads to variations in how CRM ad appeals influence consumers’ message elaboration. This study identified the cognitive mechanism underlying message elaboration to understand how it works to shield consumer evaluations against the negative effect of CRM skepticism.

The main finding is that when viewing an informational CRM communication, consumers with high CRM skepticism did not devote time and effort to central cues because they distrust the company’s sincerity and devalue its CRM claims (Matthens et al., Citation2014; Obermiller et al., Citation2005). Avoidance occurred during the information processing for highly skeptical consumers when presented with detailed information on CRM initiatives.

When viewing a negative emotional CRM appeal, highly skeptical consumers allocated their attention primarily to the text than when viewing a positive appeal. High-skepticism consumers paid more attention to an image of a sad child (a negative appeal) than that of a smiling child (a positive appeal). Negative emotional appeals led consumers to process information in a more accommodative, detailed, and systematic manner; it leads to a more careful analysis of the specific information. Although highly skeptical consumers detach themselves from CRM messages for not being worth processing (Darke & Ritchie, Citation2007) and that they contradict their existing beliefs (Knobloch-Westerwick & Meng, Citation2009), when facing CRM messages that are written to primarily induce sadness, highly skeptical consumers may be less likely to rely on stored generalized knowledge structures, resulting in attention to message details (Bless, Citation2000; Schwarz & Bless, Citation1992). Sadness induced by the negative message might allow consumers to engage in more thoughtful scrutiny when deciding whether to help someone in need or purchase an advertised product (Erlandsson et al., Citation2018).

A complementary mechanism that can explain skeptical consumers’ elaboration in processing negative emotive contents is narrative transportation (Escalas, Citation2007). The child’s plight might evoke narrative processing, which transports viewers into the needy child’s story rather than analytically thinking about motive (J. H. Nielsen & Escalas, Citation2010). Engaging and transportation stories might be valuable for reducing resistance by producing emotional effects that create a stronger message involvement.

Moreover, the degree of cognitive elaboration that participants engage in when confronted with different appeal types has a crucial mediating role in the CRM appeal effect on credibility judgment. The results demonstrated that consumers who paid more attention to the heuristic cues (Study 1) and images (Study 2) consider the CRM message to be more credible. It is consistent with previous studies; consumers involved in processing advertising contents consider the message to be believable (Guerreiro et al., Citation2015; Wang, Citation2006; Wei et al., Citation2010).

Although the mediating role of cognitive elaboration on heuristic cues is not consistent across the two studies, for more skeptical consumers, when viewing an informational appeal, attention to heuristic cues coherently enhances the perception of message credibility. Furthermore, it encourages consumers to join the brand page, which leads to greater purchase intentions. Although highly skeptical consumers do not thoroughly engage with the central element of CRM initiatives in detailed informational CRM claims that are fact-based, they still consider the message credible via close attention to the heuristic cues. This finding supports endorsement heuristics; people assign greater credibility to information verified by others (Sundar, Citation2008); thus highly skeptical consumers might rely more on heuristic cues as a source of credibility judgments (Jin & Phua, Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2019; Metzger & Flanagin, Citation2015). This study provides more evidence that credibility perception is a powerful predictor of consumers’ behavioral intention (Bae, Citation2018; Jeong et al., Citation2013).

11. Theoretical implications

This study extends the literature by examining consumers’ visual attention along with the subjective experience of message elaboration as an underlying cognitive mechanism that can help predict favorable responses to a Facebook brand page featuring CRM. The study supports the persuasion knowledge model by providing robust evidence of how the defense mechanism during information processing shapes consumer responses (Friestad & Wright, Citation1994).

However, how dispositional CRM skepticism guides consumer message elaboration (and how this message elaboration induces consumer trust in marketing communications) has been ignored. This study addressed this gap and secures an obvious link between skepticism, message elaboration, and message credibility, illustrating that consumers’ level of CRM skepticism controls the extent to which they are likely to be defensive against detailed information, which results in failed message elaboration. Eventually, this detachment from the CRM message results in greater disbelief in the company’s CRM communications (Friestad & Wright, Citation1994).

The study also extends the literature on the dual-process model. Highly skeptical consumers are less likely to be motivated to devote cognitive processing to comprehensive CRM information. This low engagement when viewing a company’s CRM information leads skeptical consumers to adopt heuristic processing; thus, they rely strongly on peripheral cues to process informational appeal CRM communications (Obermiller et al., Citation2005; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1983).

The findings are also consistent with the literature, emphasizing the beneficial processing effects of negative appeals for CRM communications (Bless, Citation2000; Bless & Fiedler, Citation2012). Highly skeptical consumers presented with a negative appeal (unlike a positive or informational appeal) seem to devote more cognitive effort in message elaboration. The cognitive benefits of a negative appeal can be understood in terms of the more accommodative, externally oriented processing style it induces (Bless & Fiedler, Citation2012) that allows consumers to rely less on existing persuasion knowledge and improves the efficacy of strategic communications.

The study demonstrates that the narrative and transportation models might serve as a theoretical framework for the level of message elaboration triggered by negatively framed CRM communications. Engaging, transporting stories may be valuable as they reduce skeptical consumers’ resistance, encourage them to process CRM information, and produce cognitive and emotional effects that create stronger attitudes and intentions (Escalas, Citation2007; Moyer-Gusé & Nabi, Citation2011; Murphy et al., Citation2013).

The study also found that the social information processing approach and dual processing model of credibility (Metzger, Citation2007) are applicable in understanding the heuristic information processing involved in skeptical consumers’ decision-making. The finding indicates that computer-generated content can be used to possibly endorse a communication (Metzger et al., Citation2010) or trigger a bandwagon cue (Sundar, Citation2008) to help consumers judge a company’s sincerity regarding a particular social cause.

12. Managerial implications

Understanding the contextual appeal to use on SNSs will help marketers enhance skeptical consumer engagement with their brand pages and build consumer relationships. The findings suggest that negative appeals seem to motivate skeptical consumers toward greater CRM messages elaboration. Particularly, the sad image of a child is a powerful force, motivating them to engage in thorough information processing rather than relying on their predisposition to be skeptical of CRM. Therefore, the negative effect of CRM skepticism can be curbed by integrating a negatively framed emotional CRM message with an image of a sad child.

Moreover, even though skeptical consumers still regard the company as credible based on heuristic cues, they do not thoroughly engage in the main element of CRM commitment in the informational claims. As long as the SNS page has system-generated heuristic or bandwagon cues, skeptical consumers may still perceive social approval of the CRM initiatives, triggering a sense of credibility. Hence, skeptical consumers may join the brand community. A social media strategy enables the brand to be part of an active community that maintains constant connections with consumers anywhere and anytime. Thus, marketers should continue to include Facebook and other social media platforms in their cause-marketing strategy because social media users are highly engaged with brands on their sites, exhibiting strong brand preference. Marketers should also maximize consumer engagement on SNSs through attention-grabbing posts and relevant updates on brand pages and encourage content sharing by users to facilitate reciprocal liking and following of brand pages.

13. Limitations and future research

First, the eye-movement data do not reveal whether participants are absorbed or are transported into the narrative world of the needy child’s sad story. Future studies should include a narrative transportation variable as a distinct mental process to differentiate the greater cognitive rigor, which invites skeptical consumers to process the content more analytically.

Second, this study failed to explore the potential mediating effect of message-induced emotions when consumers are processing CRM messages. Future studies should examine their role in motivating consumers to process information.

Third, this study examined a CRM campaign developed at the corporate level to avoid the complexity of selecting a product category relevant to the sample group. There may be different implications for brands on Facebook based on product categories. Future studies should examine a wider variety of product categories relevant to the research participants. Similarly, other prosocial causes and forms of charity should be explored as well.

Fourth, screenshots of fictitious Facebook brand pages were digitally manipulated to test the effectiveness of different CRM appeal types. There may be variations in the effectiveness of appeal types, image valence, and heuristic cues according to each social media vehicle. Future studies should test whether the effectiveness of negative CRM appeals is consistent among online photo-video sharing media such as Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter.

Finally, the effect of bandwagon heuristics may differ based on whether the number of likes or followers is high or low. Therefore, future studies should explore how the difference between a higher and lower number of computer-generated information items influences consumers’ information processing.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mikyeung Bae

Mikyeung Bae is an assistant professor in Strategic Communications at Oklahoma State University. Her research interests include cause-related marketing and consumer psychology. She has published articles, among others, in The Journal of Consumer Marketing, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, Journal of Promotion Management, Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, Computers in Human Behavior, and Asian Journal of Communication.

References

- Andersen, S. E., & Johansen, T. S. (2016). Cause-related marketing 2.0: Connection, collaboration and commitment. Journal of Marketing Communications, 22(5), 524–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2014.938684

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Ashley, C., & Tuten, T. (2014). Creative strategies in social media marketing: An exploratory study of branded social content and consumer engagement. Psychology & Marketing, 32(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20761

- Baberini, M., Coleman, C.-L., Slovic, P., & Västfjäll, D. (2015). Examining the effects of photographic attributes on sympathy, emotions, and donation behavior. Visual Communication Quarterly, 22(2), 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/15551393.2015.1061433

- Bae, M. (2018). Overcoming skepticism toward cause-related marketing claims: The role of consumers’ attributions and a temporary state of skepticism. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 35(2), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-06-2016-1827

- Bae, M. (2019). Role of skepticism and message elaboration in determining consumers’ response to cause-related marketing claims on Facebook brand pages. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2019.1666071

- Barone, M. J., Miyazaki, A. D., & Taylor, K. A. (2000). The influence of cause-related marketing on consumer choice: Does one good turn deserve another? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300282006

- Bless, H. (2000). The interplay of affect and cognition: The mediating role of general knowledge structures. Cambridge University Press.

- Bless, H., & Fiedler, K. (2012). Mood and the regulation of information processing and behavior. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Affect in social thinking and behavior (pp. 65–84). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

- Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Juric, B., & Ilic, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252–271. https://doi.org/0.1177/1094670511411703

- Campbell, M. C., & Kirmani, A. (2000). Consumers’ use of persuasion knowledge: The effects of accessibility and cognitive capacity on perceptions of an influence agent. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1086/314309

- Chaiken, S., & Trope, Y. (1999). Dual-process theories in social psychology. Guilford Press.

- Chang, C.-T. (2011). Guilt appeals in cause-related marketing The subversive roles of product type and donation magnitude. International Journal of Advertising, 30(4), 587–616. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-30-4-587-616

- Chernev, A., & Blair, S. (2015). Doing well by doing good: The benevolent halo of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(6), 1412–1425. https://doi.org/10.1086/680089

- Darke, P. R., & Ritchie, R. J. B. (2007). The defensive consumer: Advertising deception, defensive processing, and distrust. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(1), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.1.114

- Dean, D. H. (2004). Consumer reaction to negative publicity: Effects of corporate reputation, response, and responsibility for a crisis event. Journal of Business Communication, 41(2), 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943603261748

- DeCarlo, T. E., & Barone, M. J. (2009). With suspicious (but happy) minds: Mood’s ability to neutralize the effects of suspicion on persuasion. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(3), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.02.018

- Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2015). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2014-0635

- Erlandsson, A., Nilsson, A., & Västfjäll, D. (2018). Attitudes and donation behavior when reading positive and negative charity appeals. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 30(4), 444–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2018.1452828

- Escalas, J. E. (2007). Self-referencing and persuasion: Narrative transportation versus analytical elaboration. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(4), 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1086/510216

- Fiedler, K. (2001). Affective influences on social information processing. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), The handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 163–185). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Forehand, M. R., & Grier, S. (2003). When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company intent on consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1303_15

- Fornell, C., & Larker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Friestad, M., & Wright, P. (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/209380

- Goldsmith, R. E., Lafferty, B. A., & Newell, S. J. (2000). The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity credibility on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673616

- Guerreiro, J., Rita, P., & Trigueiros, D. (2015). Attention, emotions and cause-related marketing effectiveness. European Journal of Marketing, 49(11), 1728–1750. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-09-2014-0543

- Gupta, S., & Pirsch, J. (2006). The company-cause-customer fit decision in cause-related marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(6), 314–326. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760610701850

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

- Hock, M., & Krohne, H. W. (2004). Coping with threat and memory for ambiguous information: Testing the repressive discontinuity hypothesis. Emotion, 4(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.65

- Homer, P. M., & Yoon, S. (1992). Message framing and the interrelationships among ad-based feelings, affect, and cognition. Journal of Advertising, 21(1),19-33.

- Jeong, H. J., Paek, H.-J., & Lee, M. (2013). Corporate social responsibility effects on social network sites. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1889–1895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.010

- Jin, S.-A.-A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following celebrities’ Twitter about brands: The impact of Twitt-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers’ source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.827606

- Kanter, D., & Wortzel, L. H. (1985). CYNICISM AND ALIENATION AS MARKETING CONSIDERATIONS: SOME NEW WAYS TO APPROACH THE FEMALE CONSUMER. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 2(1),5-15.

- Ketelaar, P. E., Bernritter, S. F., Riet, J. V. T., Huhn, A. E., Woudenberg, T. J. V., Muller, B. C. N., & Janssen, L. (2017). Disentangling location-based advertising: The effects of location congruency and medium type on consumers’ ad attention and brand choice. International Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1093810

- Kim, S., Haley, E., & Koo, G.-Y. (2009). Comparison of the paths from consumer involvement types to ad responses between corporate advertising and product advertising. Journal of Advertising, 38(3), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367380305

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S., & Meng, J. (2009). Looking the other way: Selective exposure to attitude-consistent and counterattitudinal political information. Communication Research, 36(3), 426–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650209333030

- Knoll, J. (2016). Advertising in social media: A review of empirical evidence. International Journal of Advertising, 35(2), 266–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1021898

- Laczniak, R. N., Muehling, D. D., & Grossbart, S. (1989). Manipulating message involvement in advertising research. Journal of Advertising, 18(2), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1989.10673149

- Lee, Y.-J., O’Donnell, N. H., & Hust, S. J. (2019). Interaction effects of system-generated information and consumer skepticism: An evaluation of issue support behavior in CSR Twitter campaigns. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1507853

- Lin, L.-Y., & Lu, C.-Y. (2010). The influence of corporate image, relationship marketing, and trust on purchase intention: The moderating effects of word-of-mouth. Tourism Review, 65(3), 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371011083503

- Lipsman, A., Mudd, G., Rich, M., & Bruich, S. (2012). The power of like: How brands reach (and influence) fans through social media marketing. Journal of Advertising Research, 52(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-52-1-040-052

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251413

- Manchanda, P., Packard, G., & Pattabhiramaiah, A. (2015). Social dollars: The economic impact of customer participation in a firm-sponsored online customer community. Marketing Science, 34(3), 367–387. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2014.0890

- Matthens, J., Wonneberger, A., & Schmuck, D. (2014). Consumers’ green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 1885–1893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.054

- Matthes, J., & Wonneberger, A. (2014). The skeptical green consumer revisited: Testing the relationship between green consumerism and skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.834804

- McDonald, R. P., & Marsh, H. W. (1990). Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.247

- Metzger, M. J. (2007). Making sense of credibility on the web: Models for evaluating online information and recommendations for future research. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology Banner, 58(13), 2078–2091. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20672

- Metzger, M. J., & Flanagin, A. J. (2015). Psychological approaches to credibility assessment online. Wiley Blackwell.

- Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., & Medders, R. B. (2010). Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. Journal of Communication, 60(2), 413–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01488.x

- Moyer-Gusé, E., & Nabi, R. L. (2011). Comparing the effects of entertainment and educational television programming on risky sexual behavior. Health Communication, 26(5), 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2011.552481

- Muk, A., & Chung, C. (2014). Driving Consumers to Become Fans of Brand Pages: A Theoretical Framework. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 14(1),1-10.

- Murphy, S. T., Frank, L. B., Chatterjee, J. S., & Baezconde-Garbanati, L. (2013). Narrative versus nonnarrative: The role of identification, transportation, and emotion in reducing health disparities. Journal of Communication, 63(1), 116–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12007

- Myers, J., & Sar, S. (2015). The influence of consumer mood state as a contextual factor on imagery-inducing advertisements and brand attitude. Journal of Marketing Communications, 21(4), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2012.762421

- Nielsen. (2014). Doing well by doing good. New York, NY: The Nielsen Company, LLC. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2014/doing-well-by-doing-good.html

- Nielsen. (2016). Global responsibility & sustainability. New York, NY: The Nielsen Company, LLC. Retrieved from http://sites.nielsen.com/yearinreview/2016/global-responsibility-and-sustainability.html

- Nielsen, J. H., & Escalas, J. E. (2010). Easier is not always better: The moderating role of processing type on preference fluency. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(3), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2010.06.016

- Obermiller, C., & Spangenberg, E. R. (1998). Development of a scale to measure consumer skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(2), 159–186. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp0702_03

- Obermiller, C., Spangenberg, E. R., & MacLachlan, D. L. (2005). Ad skepticism: The consequences of disbelief. Journal of Advertising, 34(3), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2005.10639199

- Odou, P., & Perchpeyrou, P. D. (2011). Consumer cynicism. European Journal of Marketing, 45(11/12), 1799–1808. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111167432

- Perse, E. M. (1990). Audience selectivity and involvement in the newer media environment. Communication Research, 17(5), 675–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365090017005005

- Peterson, R. A. (2001). On the use of college students in social science research: Insights from a second-order meta-analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(3), 450–461. https://doi.org/10.1086/323732

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1981). Issue involvement as a moderator of the effects on attitude of advertising content and context. In K. B. Monroe (Ed.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 8, pp. 20–25). Association for Consumer Research.

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1983). Central and peripheral routes to persuasion: Application to advertising. In L. Percy & A. Woodside (Eds.), Advertising and consumer psychology (pp. 3–23). Lexington Books.

- Phua, J., & Ahn, S. U. (2014). Explicating the ‘like’ on Facebook brand pages: The effect of intensity of Facebook use, number of overall ‘likes’, and number of friends ' ‘likes’ on consumers' brand outcomes. Journal of Marketing Communications, 22(5),544-559.

- Pieters, R., Wedel, M., & Batra, R. (2010). The stopping power of advertising: Measures and effects of visual complexity. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.5.48

- Preston, J. (2011). Pepsi bets on local grants, not the super bowl. New York, NY: The New York Times Company. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/31/business/media/31pepsi.html

- Rayner, K. (1998). Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 124(3), 372–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.372

- Rubin, A. M. (1993). Audience activity and media use. Communication Monographs, 60(1), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759309376300

- Russo, J. E. (2011). Eye fixations as a process trace. In M. Schulte-Mecklenbeck, A. Kuhberger, & R. Ranyard (Eds.), A handbook of process tracing methods for decision research: A critical reveiw and user’s guide (pp. 43–64). Psychology Press.

- Schwarz, N., & Bless, H. (1992). Constructing reality and its alternatives: Assimilation and constrast effects in social judgment. Erlbaum.

- Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.225.18838

- Singh, S., Kristensen, L., & Villasenor, E. (2009). Overcoming skepticism towards cause related claims: The case of Norway. International Marketing Review, 26(3), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330910960807

- Skarmeas, D., & Leonidou, C. N. (2013). When consumers doubt, watch out! The role of CSR skepticism. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1831–1838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.004

- Small, D. A., & Verrochi, M. M. (2009). The face of need: Facial emotion expression on charity advertisements. Journal of Marketing Research, 46 (6), 777–787. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20618940

- Sundar, S. S. (2008). The main model: A heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility. In M. J. Metzger & A. J. Flanagin (Eds.), Digital media and learning (pp. 73–100). The MIT Press.

- Szykman, L. R., Bloom, P. N., & Blazing, J. (2004). Does corporate sponsorship of a socially-oriented message make a difference? An investigation of the effects of sponsorship identity on responses to an anti-drinking and driving message. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(1&2), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1401&2_3

- Wang, A. (2006). Advertising engagement: A driver of message involvement on message effects. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849906060429

- Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (1998). A typology of consumer responses to cause-related marketing: From skeptics to socially concerned. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 17 (2), 226–238. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30000773

- Wei, R., LO, V.-H., & Lu, H.-Y. (2010). The third-person effect of tainted food product recall news: Examining the role of credibility, attention, and elaboration for college students in Taiwan. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 87(3–4), 598–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769901008700310

- Westerman, D., Spence, P. R., & Heide, B. V. D. (2012). A social network as information: The effect of system generated reports of connectedness on credibility on Twitter. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(1), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.001

- Westerman, D., Spence, P. R., & Heide, B. V. D. (2014). Social media as information source: Recency of updates and credibility of information. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12041

- Wolfe, J. M., & Horowitz, T. S. (2004). What attributes guide the deployment of visual attention and how do they do it? Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 5(6), 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1411

- Yoo, C., & MacInnis, D. (2005). The brand attitude formation process of emotional and informational ads. Journal of Business Research, 58(10), 1397–1406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.03.011

- Yoon, Y., Gurhan-Canli, Z., & Schwarz, N. (2006). The efffect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1604_9