?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In this study, we examine the competitiveness effect of currency depreciation in the presence of external commercial borrowing (ECBs) and low financial development. The estimates of autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) show the contractionary effects of exchange rate depreciation on exports owing to increased liability denominated in foreign currency such as ECBs. We also find a positive relationship between bank credit and exports, but the marginal benefits of domestic credit diminish when the exchange rate depreciates. The findings of the study suggest that natural hedging does not act as a cushion against shocks and thus calls for the mandatory use of derivatives by firms. The development of domestic credit markets is essential to reap the benefits of currency depriciation in the export sector.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The present research probes the effect of foreign currency borrowing and the availability of credit in the domestic market on exports. The exports usually increase following a depreciation of the domestic currency as the goods and services become effectively cheaper. However, an increase in the foreign currency loans at the same time, offsets the benefits of depreciation. Also, export firms need credit to meet the increased demand due to the depreciation of the currency. The unavailability of such credit also adversely affects exports. In this research, we find that the foreign currency borrowings are neutralizing the benefits of export firms arising from the depreciation of the currency. The lack of financial development in India also adversely affecting exports in India. Therefore, we suggest mandatory hedging by the firms which can be facilitated by strengthening the derivatives markets.

1. Introduction

Conventional expenditure switching theories posit the expansionary impact of devaluations—that they have a positive effect on the current account. These small economy frameworks under a flexible exchange rate regime show the ability of currency depreciation to shift the demand from costlier imports towards cheaper domestic goods when the economy faces a real adverse shock. As a result, currency depreciation has competitiveness effect on exports thereby raising the earnings of the export sector (Duttagupta & Spilimbergo, Citation2004; Forbes, Citation2002; Ghei & Pritchett, Citation1999; Krueger & Tornell, Citation1999).

Theoretically, competitiveness effects depend on three factors as explained by the Marshall-Learner conditions—(a) domestic export prices are set in the local currency and absence of market pricing; (b) the supply of exports is sufficiently elastic; (c) the foreign demand for domestic exports is sufficiently elastic. Following the East Asia crisis, however, there has been growing evidence of the contractionary effect of depreciation on exports. Such a currency–export dilemma—i.e., the sluggish response of exports to currency depreciation—challenges conventional theories that exchange rate depreciation always has expansionary effects (Berman & Berthou, Citation2009; Duttagupta & Spilimbergo, Citation2004; Tang et al., Citation2013). Recent literature on open economy macroeconomics and corporate finance emphasise the role of credit market frictions in explaining the response of exports to currency depreciation. Foreign currency borrowings and the lack of domestic financial development impede the export growth of developing economies. Despite the importance of the issue, the evidence on India’s exports to exchange rate depreciation in the context of credit market imperfections has not been given enough attention. In this light, we investigate the growth of India’s exports in the presence of foreign currency liabilities and the lack of financial development or credit market frictions.

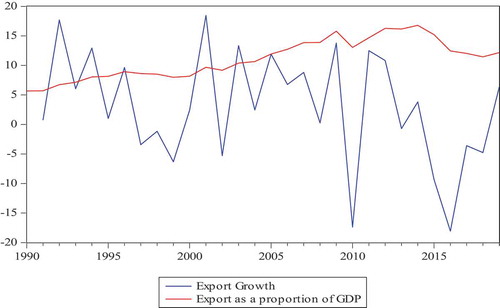

Against the backdrop of the 1991 balance of payments crisis, India embarked on structural reforms that established a new liberalisation policy framework. The government dismantled the controls on foreign trade and emphasised the promotion of exports (DIPP, Citation1991). India has adopted an export-led growth strategy since liberalisation, which is evident from subsequent trade policies. Export promotion schemes such as subsidies, export parks, and marketing assistance were introduced to facilitate growth in exports, and special economic zones (SEZs) were set up to foster exclusive export units. The ratio of total exports of goods and services to gross domestic product (GDP) in India increased from 5.67 percent in 1990 to 15.21 percent in 2015. However, the trend was volatile during the liberalisation era. The average growth rate of exports in the first decade of reforms (1991–2000) was 3.97 percent. The growth rate stood 4.68 percent during our study period 2001–2015 (, Appendix).

In consonance with the financial liberalisation policy framework, restrictions on overseas borrowings have been eased over the years. The corporate sector was allowed to borrow in foreign currency in order to meet short-term and long-term financial needs, albeit with few restrictions. Notably, external commercial borrowing (ECBs) increased from US$ 6.2 billion in 1986 to US$ 181.28 billion in 2016. The ratio of ECBs to total external debt in India rose from 16.57 percent in 1991 to 37.33 percent in 2016. Shin and Zhao (Citation2013) have raised concerns over growing ECBs in India and China, which Pradhan and Hiremath (Citation2020a) have highlighted the possible destabilising effect of such borrowings.

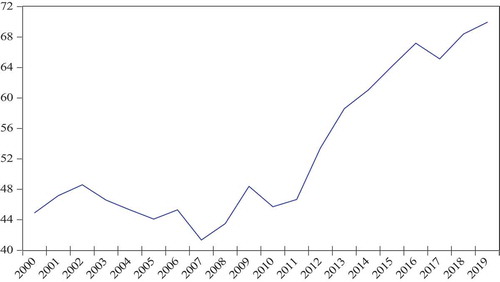

India has adopted a managed floating exchange rate system consistent with the policy of financial liberalisation. The value of the INR depreciated to INR 61.029/US$1 in 2014 from INR 44.940 in 2000. This depreciation implies a 1.36 times decrease in the value of the domestic currency against the US dollar. In 1992, the Indian government implemented a dual exchange rate system, which permitted exporters to convert 60 percent of their earnings in foreign exchange at the market rate and 40 percent at a lower official rate set by the government. Later, the managed floating exchange rate system was followed to asymmetrically intervene in the forex market to maintain export competitiveness (Ramachandran & Srinivasan, Citation2007). The annual exchange rate of the domestic currency against the US dollar stands at INR 69.93 per dollar in 2019 (, Appendix).

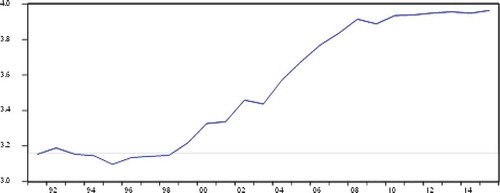

Sound and vibrant financial markets and institutions are essential for the successful opening of the economy for foreign trade and investment. Hence, financial sector reforms were introduced in India to deepen financial liberalisation. Domestic credit extended to the private sector has grown over the years since liberalisation (Figure ). However, India’s financial development is not on par with its emerging market (EM) peers. Banks still dominate the credit market in India, and this sector accounts for 64 percent of the total assets held by the overall financial system (India Brand Equity Foundation, Citation2020). The public sector accounts for the lion’s share in bank-based credit. The Indian banking sector’s asset quality has deteriorated over the years, primarily because of an increase in bad loans and bank fraud (RBI, Citation2017). India’s banking sector is indeed experiencing a crisis, whereas non-banking sources of finance are negligible (Hiremath, Citation2019). As a result, firms are facing credit constraints in domestic markets.

In this context, investigation of export performance in the presence of ECBs and a low level of financial development assumes importance. Previous studies have concentrated on the effects of the exchange rate (Chit et al., Citation2010; Chou, Citation2000; Sauer & Bohara, Citation2001) or level of financial sector development on exports ignoring the foreign liability channel. For instance, Chit and Judge (Citation2011) show that the effect of exchange rate volatility on exports depends on the level of financial sector development. Berman and Berthou (Citation2009) and Tang et al. (Citation2013) find that firms borrowing in foreign currency are exposed to substantial depreciation, and exports suffer owing to liabilities denominated in foreign currency or due to domestic credit constraints. However, these studies ignore supply-side factors. The inertia of export firms with dollar debt is expected to hurt aggregate output and defeat the export-led growth strategy. Departing from previous work, we follow a holistic and comprehensive approach to examine the issue and thus contribute to the literature on trade and finance.

The present study contributes to the literature on trade and open economy macroeconomics in the following ways. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the impact of ECBs and financial development on competitiveness effects in the Indian context. India is an ideal case for examining this issue given the growing presence of foreign corporate debt and the export-led growth strategy since 1991. Second, we study the interaction between exchange rate, financial development, and ECBs, instead of focusing on one aspect in isolation. Finally, a country level study of this kind offers insights into the unique and peculiar features of India’s macroeconomic environment, financial market development, and trade policy framework. To foreshadow the key result, we find that the lack of financial development and growing ECBs adversely affect India’s exports in the event of currency depreication. The findings call for policies to strength domestic credit markets. The rest of the paper is organised as follows. In Section 2, we present our theoretical framework and provide a summary of previous studies. Section 3 gives the outline the methodology. We discuss the empirical results in Section 4 and conclude the paper in Section 5.

2. Theoretical framework and related literature

One part of the literature holds the excessive dependency on short-term overseas borrowings, financial instability in the global market, mismanagement and under-regulation of domestic financial systems, and crony capitalism to be contributing factors for regional economic crises (Radelet & Sachs, Citation1998; Stiglitz, Citation1998). A recent study by Pradhan and Hiremath (Citation2020b) shows that both firm-specific factors and macroeconomic factors are responsible for the corporate sector dollarization among Indian firms. In contrast, the modified, dynamic New Keynesian general equilibrium model propounded by Bernanke et al. (Citation1999) demonstrates the role of credit market frictions in business fluctuations. Their framework depicts a “financial accelerator” in which endogenous developments in credit markets amplify and propagate real and nominal shocks in the economy. The amplification effects help resolve shocks, which can have a substantial real effect.

Baldwin and Krugman (Citation1989) studied the exit of firms from the export market following a substantial negative shock from exchange rate depreciation emanating from financial market imperfections. The export firms bear higher sunk costs, which are more significant than the fixed cost paid by incumbent firms in the presence of market imperfections. A considerable amount of private debt is denominated in foreign currency to cover sunk costs and other fixed costs. Most of such external borrowings are unhedged, which exposes these economies to foreign exchange risk. On similar lines, Krugman (Citation1999) and Aghion et al. (Citation2001) demonstrate the adverse impact of financial frictions such as foreign currency debt on investments, cash flows, and the net worth of the firms. Caballero and Krishnamurthy (Citation2003) consider financial constraints a significant determinant of the vast stockpile of dollar-denominated debt in developing nations.

Eichengreen and Hausmann (Citation1999) argue that countries borrow in foreign currencies due to their inability to raise funds in global markets in their own currencies. Such an inability, popularly known as original sin, adversely affects the economy in the event of external shocks. Global factors such as transaction costs and network externalities constrain the ability of emerging economies to borrow from global markets or domestic markets for the long term. On the other hand, Goldstein and Turner (Citation2004) hold domestic factors such as weak economic policies and institutions as the primary causes of currency mismatch in emerging economies.

The dominant role of credit market frictions other than foreign currency debt underlies these dramatic episodes of financial crises. Rajan and Zingales (Citation1998) argue that economies with greater financial development grow faster due to financial liberalisation than those without developed financial markets and institutions. Venkatesh and Hiremath (Citation2020) show how emerging economies in Asia reduced the original sin by evaluating domestic credit markets. Credit market frictions include moral hazard, heterogeneity, and specificity, which reduce the number of financiers and discourage entrant firms by acting as constraints on finance (Wasmer & Weil Citation2004). The sluggish response of exports to the depreciation of the currency is primarily due to the price inelasticity of foreign demand for exports, credit constraints (which limit the supply of exporters), and the exogenous shift in world demand (Duttagupta & Spilimbergo, Citation2004). Constraints in the banking sector and the presence of low-quality financial markets with less information limit the gains from economic reforms and liberalisation policies (Brooks & Dovis Citation2020; Buera & Shin Citation2013; Kunieda & Shibata Citation2014; Shin & Zhao, Citation2013; Song et al. Citation2011).

Drawing on this theoretical debate, our conceptual framework relies on third-generation models of exchange rate combined with the model of credit market frictions of Bernanke et al. (Citation1999). Conventionally, exports are expected to increase following currency depreciation. However, the response of exports will be sluggish in the presence of friction in domestic credit markets. In the event of external shock, the value of loan repayments contracted in a foreign currency increases; and the number of tradable firms and the volume of exports falls. The lack of credit facility in the domestic market constrains firms from increasing supply in the export sector. Foreign debt and the low level of financial development not only worsen the balance sheets of export firms but also hurt economic growth.

The theoretical work on the incorporation of the role of credit markets in open economy macroeconomics led to the empirical investigation of the relationship between credit markets and exports. However, the research on this topic is still nascent. Berman and Berthou (Citation2009) hold that the frictions in credit markets contribute to boom–bust cycles in the economy. They estimated demand and supply export equations to examine the impact of financial market imperfections on the country’s exports in the event of exchange rate depreciation. They found that depriciation had an adverse effect on exports in those economies in which firms borrow in a foreign currency. Their sample includes 27 developed and developing countries for the period 1990 to 2005. Their findings show that the firms borrowing in foreign currency are exposed to substantial depreciation or devaluation.

Tang et al. (Citation2013) empirically demonstrated the adverse impact of significant depreciation on the exports of 17 East Asia-Pacific countries in the presence of foreign currency debt and lower levels of financial development. They argue that limited credit availability for export firms in countries with underdeveloped financial markets force them to borrow in foreign currencies. The weak credit markets in these economies restrict export firms from raising finance domestically. Hence, the expansionary effect is unrealised when financial markets are underdeveloped. Their results corroborate the findings of Berman and Berthou (Citation2009). Nevertheless, Tang et al. (Citation2013) ignore supply-side factors.

In this context, we inquire whether ECBs and financial development result in export contraction and stagnation. Does the financial development shock lower exports through the magnification effect? To the best of our knowledge, our study is a novel attempt to address these questions, especially in the context of an emerging economy such as India. We hypothesise that massive outstanding corporate debt in foreign currency and low levels of financial development adversely affect exports following the depreciation of the rupee against the dollar. We thus extend the empirical literature on open economy macroeconomics and corporate finance. We also capture the amplification effects of foreign liability, which is a novel contribution of this paper.

3. Methodology

In this study, we employ the ARDL model to examine how ECBs and financial development are related to exports in the long run. We also estimate ECM to capture short-term fluctuations. Furthermore, dynamic panel regression is estimated to generate firm-level evidence.

3.1. Export function and variables

The preceding discussion highlights several variables that influence the competitiveness effect. We investigate the issue in light of two underlying market imperfections—i.e., a considerable amount of private debt is denominated in foreign currency; low financial development restricts agents from borrowing domestically. Nonetheless, the availability of credit, and the constraints on it, are also industry-specific. Recently, there has been a concentration of ECBs in the manufacturing sector, followed by the software industry (Table ). ECB has increasingly become an essential source of finance for export firms between 2004 and 2015. The trend indicates that ECBs are a significant source of funds for Indian firms to meet long-term goals. Our focus in this study is on export firms that borrow in foreign currency through the ECBs route.Footnote1

Table 1. ECBs by the export firms

We estimate the following export function to quantify the effect of ECBs and level of financial development on exports:

In EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) EXPORTS is the export of goods and services from India in real termsFootnote2; ΔREER denotes the change in the real effective exchange rate. GDP and FD are the gross domestic product and the level of financial development, respectively. We employ quarterly time series data expressed in rupees from 2000 to 2014 for the analysis. We collected data from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), UNCTAD, Reserve Bank of India (RBI), and the World Bank. All variables are presented in real terms and have been transformed into natural logarithms to maintain uniformity. Moreover, the logarithmic transformations make positively skewed variables customarily distributed (Changyong et al. Citation2014).

In the absence of credit market imperfections, the coefficient of the traditional macroeconomic fundamentals (i.e., GDP) is anticipated to be positive. The supply of exports depends on the potential local income and hence 1 > 0. The expected sign of the coefficient of ΔREER

2)Footnote3 is positive because currency depreciation makes exports inexpensive. Hence, the demand for exports increases with a small depreciation of the exchange rate. Moreover, the relationship between ΔREER and the trade balance depends upon the time horizon—here, it is the long run. In the presence of credit market imperfections, depreciation does not always have competitiveness effects. The realisation of the expansionary effect depends on the country’s foreign debt and financial development. The interaction term, REERt*ECBt, captures the impact of ECBs on exports in response to currency depreciation. Hence, the coefficient of REERt*ECBt

3) is expected to be negative because more ECBs in a country implies the negative response of exports following a depreciation. A significant depreciation of the real exchange rate increases the country’s debt burden and borrowing costs and limits its production capabilities.

We include the financial development variable to capture the effect of credit constraints on exports. The interaction term REERt*FDt measures this effect. We use the domestic private credit to non-financial sectors as a proportion of GDP as a proxy for credit constraints. The proxy is consistent with the standard literature (e.g., Berman & Berthou, Citation2009; Tang et al., Citation2013). The World Bank (Citation2020) considers domestic private credit to non-financial sectors as one of the accepted measures of financial depth. Such a measure explains the level of credit. This proxy has also received much attention in the empirical literature as it has a strong statistical link to long-term economic growth (World Bank, Citation2020). This measure excludes loans offered to governments, public enterprises, and other government agencies. It also does not comprise the credit issued by central banks. The theoretically expected sign of 4 (financial development) is uncertain. The countries with a higher level of financial development have more significant exports deriving a positive coefficient and vice-versa (Tang et al., Citation2013).

Additionally, we include three non-linear components: (i) interaction of exchange rate and financial development; (ii) exchange rate; and (iii) ECBs. We consider the non-linear forms of these variables to capture the relevant features of the data based on the theoretical propositions discussed in previous studies. We use the non-linear, REERt*FDt2 to capture the amplification effects of financial shocks on exports (see, Bernanke et al., Citation1999). The sign of 4 is expected to be positive when financial development facilitates the growth of exports. When the dampening impact of the financial shock is amplified and propagated,

5 is expected to be negative. Arcand et al. (Citation2012) record a concave relationship between financial development and economic growth. The author supports the hypothesis that there is such a thing as “too much finance”—where the marginal effect of financial development turns negative after a threshold. We use ΔREERt2 to capture the non-linear shocks of exchange rate depreciation on exports (Baldwin & Krugman, Citation1989). We expect a negative sign for the coefficient of the squared exchange rate (

6) because substantial currency depreciation offsets the competitiveness effect. The coefficient of the squared term of the foreign liability (

7) is also expected to be negative due to its association with amplification effects of balance sheet shocks. Excess reliance on foreign currency borrowings will inflate the outstanding debt and hurts the exports as evident from the East Asian crisis. We test the hypothesis that more corporate borrowings and credit constraints in the economy result in the deterioration of exports in the event of currency depreciation. We anticipate a non-linear, but inverse relationship between ECBs and exports.

3.2. ARDL cointegration

The cointegration methods of Engle and Granger (Citation1987) and Johansen (Citation1991) are the fundamental approaches discussed in the empirical literature to estimate long-run relationships among variables.Footnote4 The same order of integration of time series variables is a prerequisite for conducting cointegration techniques. However, we find that the variables included in the model are not of the same order of integration (Table ). We employ the ARDL bound testing approach of Pesaran and Shin (Citation1998) to overcome the problem of a different order of integration. ARDL is an advanced approach to analyse the long-run relationships and dynamic interactions among the variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Table 3. Unit root statistics

Bound testing (BT) is a two-stage approach builds on the ARDL framework. The Wald test or F-statistic is conducted by imposing linear restrictions on the estimated long-run coefficients with one period lag to validate the existence of a long-run relationship in levels among the variables. The calculated values of F-statistic are then compared with the critical tabulated values (Pesaran et al., Citation2001). These tables report the lower bound critical values based on the assumption that the explanatory variables Xt are I(0), whereas the upper bound critical values are based on the assumption that Xt is I(1). The null and alternative hypotheses are as follows:

If the computed F-statistic is higher than the upper bound tabulated values, the null hypothesis of no long-run relationship can be rejected. Conversely, if the computed F-statistic value is smaller than the lower bound tabulated values, then the null hypothesis of no cointegration cannot be dismissed. When the calculated F-statistic value falls between the lower and upper bound tabulated values, the results are inconclusive.

We use short-run dynamic error correction models (ECM) to examine short-run fluctuations corrected in the long-run. We estimate ECM to check how fast a dependent variable adjusts to its equilibrium after a change in the independent variables. Therefore, ECM is a useful tool for estimating the short-run dynamics of the parameters. We employ Case V of Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) c0 ≠ 0 and c1 ≠ 0 because our model supports the unrestricted linear trend and intercepts (Table ). Nevertheless, the unit root test proposed by Dickey and Fuller (Citation1979), unlike Dickey and Fuller (Citation1981), ignores the constraints linking the intercept and trend coefficient, c0 and c1, to the parameter vectors (πyy, πyx,x), respectively, in Cases III and V. Here, the deterministic trend restriction c1 = —(πEXPORTS, EXPORTS, πEXPORTSx,x)ϒ is ignored, and the ECM is denoted as:

Table 4. Pre-requisite diagnostic check for ARDL estimation

Table 5. Long-run coefficients of the variable in the equation

Table 6. Diagnostic tests of the long-run estimates

Table 7. ECM test statistics

We test the relationship between EXPORTSt and the Xt of the joint null hypothesis (πEXPORTS, EXPORTS = 0, πEXPORTSx,x = 0) in the model. EXPORTS is the dependent variable, whereas X represents independent variables, namely, GDP, ΔREER, REER*ECB, REER*FD, REER*FD2, ΔREER2, and ECB2 as defined in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) .

4. Results and discussions

The descriptive statistics presented in Table show that the mean values of all the variables are positive. The positive skewness of variables, namely REER*ECB and ECB2, indicates fat tail distribution. The negative skewness for EXPORTS, REER*FD2, REER*FD, ΔREER, ΔREER2, and GDP implies that distribution is skewed to the left. The Jarque–Bera (Citation1987) test results indicate the non-normal distribution of series except ΔREER and ΔREER2.

We employ unit root tests, namely ADF (Citation1979), PP (Citation1988), and KPSS (Citation1992), to check the stationarity of the time series and ascertain the order of integration of regressors included in the model. The results in Table reveal that all the variables are integrated of the order I(1) except ΔREER and ΔREER2, which are I(0). Therefore, the ARDL technique is the most suitable in this case.

4.1. The long-run relationship among the variables

We estimate EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) to quantify the long-run relationship between India’s exports and its determinants. We include variables with the lag terms regressed on the dependent variable. Pesaran and Shin (Citation1998) demonstrate the reliability and usefulness of the ARDL procedure to estimate data with small samples. However, we employ quarterly time series data with 60 observations, to ensure robust estimations. We use the SBC to select the lag in ARDL. The SBC not only has small-sample properties similar to the AIC, but it is also consistent, parsimonious, and performs better in most experiments (Morimune & Mantani, Citation1995; Quinn, Citation1988).

The bound test statistics presented in Table reject the null of no cointegration at a one percent level of significance when EXPORTS is the dependent variable across the models. Notwithstanding, we find no unique long-run relationship (except the Model D) between EXPORTS and the explanatory variables—GDP, ΔREER, REER*ECB, REER*FD, REER*FD2, ΔREER2, and ECB2.

Purposively, we report five models to establish the long-run and short-run dynamics between exports and independent variables. In Model A, we examine the foreign liability channel; Model B explains the effect of financial development, whereas Model C documents financial development and its amplification effects. Model D and E examine the amplification effects of the exchange rate and foreign liability, respectively.

The estimates of long-run ARDL models are presented in Table (Model A-E). We follow the SBC criteria to select the appropriate lag length for ARDL model estimation. The order of the ARDL model corrects the residual serial correlation and endogeneity problem (Pesaran & Shin, Citation1998).

The long-run estimates of all the selected variables are consistent with the priori and expectations except REER*FD2. We categorise GDP and ΔREER as variables representing traditional competitiveness effects. The positive and significant coefficient of GDP in all the models implies the positive impact of domestic activity on exports. The value of income elasticity is greater than unity suggesting the sensitiveness of exports’ supply to national income. Our results on the GDP–exports nexus are consistent with the previous studies (Berman & Berthou, Citation2009; Duttagupta & Spilimbergo, Citation2004; Tang et al., Citation2013). The variable ΔREER is insignificant in all the models in the long run. The evidence on REER indicates that the exchange rate alone does not help boost exports in a competitive global market. This result is consistent with the findings of Berman and Berthou (Citation2009) for developed and developing countries but contrasts evidence from a group of East Asia-Pacific countries (Tang et al., Citation2013).

ECBs and financial development are the central explanatory variables of the current research. We find a negative and significant impact of foreign liability on India’s exports (see Models A-D, Table ). The findings suggest that the exchange rate has an adverse effect on India’s exports due to the dependency on ECBs to finance business in the export sector. The exchange rate depreciation deteriorates the balance sheets of export firms through foreign liabilities and the bank-lending channel and nullifies the traditional competitiveness effect emanating from the exchange rate depreciation. The unfavourable impact of changes in the exchange rate reduces the capability of a few firms to service their debt. At the same time, new entrants will be reluctant to borrow from external sources. In a nutshell, the potentiality and production capacity of the export sector declines. Our findings show why exchange rate depreciation does not always lead to competitiveness or expansionary effects.

We include the interaction term REER and private credit to the non-financial sector (REER*FD) in Model B to examine the effect of the exchange rate through the financial development channel. Domestic credit to the private sector (level of financial development) has been notably surging since 1995 and witnessed a steep growth between 1998 and 2008. However, the growth rate was flattened afterwards (Figure ). In our analysis, we find that financial development has a positive effect on exports. The evidence supports the hypothesis that countries with developed financial sectors experience higher exports than those without such sectors. Our results corroborate the findings of Kletzer and Bardhan (Citation1987), Beck (Citation2002), and Tang et al. (Citation2013) in this respect. Although India has made progress in terms of financial development during the post-liberalisation period, the domestic credit market is still dominated by the banking sector.

Figure 1. Growth of domestic private credit.

We also capture the amplification effects of financial development on India’s exports in Model C. The coefficient of REER*FD2 is negative and statistically significant (10 percent). The negative sign implies a concave relationship between financial development and exports. In other words, the marginal benefits of domestic credit availability diminish in the event of large exchange rate depreciation. Our findings of REER*FD2 is inconsistent with the previous studies (e.g., Berman & Berthou, Citation2009; Tang et al., Citation2013). Nonetheless, this finding draws further support from a couple of important studies. For instance, Arcand et al. (Citation2012) derive a non-monotonic and concave relationship between financial development and economic growth. The authors find a positive relationship between the size of the financial system and economic growth at intermediate levels. However, they find a plunge in output growth due to more finance. Arcand et al. (Citation2012) support the “too much finance” hypothesis and accredit the misallocation of resources to such a concave trend. Samargandi et al. (Citation2015) also demonstrate the effect of the presence of too much finance in many developing economies. In our analysis, the non-linear effect of financial development is negative due to the misallocation of resources or the wrong selection of projects. Our findings are consistent with the argument of Hiremath (Citation2019) that the growing non-performing assets and defaults are primarily concentrated among large firms due to approval of wrong projects and misallocation of the resources by the Indian banking sector. Thus, not only the availability but also efficient allocation of credit is critical to ensure the good performance of the export sector.

Furthermore, we find the squared value of the exchange rate on the exports to be negative but insignificant, implying that there is no notable influence of exchange rate shocks on exports (Model D). We include the non-linear component of ECBs to capture the amplification effects of the foreign liability. The estimate suggests the detrimental effects of external liability shocks on the economy (Model E).

The diagnostic statistics of the long-run coefficients of the variable are reported in Tables and . The statistically significant F-statistic implies that the independent variables included in the model can define the best variations in the dependent variable. The high value of adjusted R2 confirms that the model is a good fit. The model (EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) ) passes several diagnostic tests, namely the Lagrange Multiplier serial correlation, Jarque–Bera normality, Ramsey RESET specification, and heteroscedasticity tests (Table ).

Overall, our results establish that growing ECBs and lack of financial development hurt exports in the event of currency depreciation. Such a deterioration will affect economic growth and worsen the current account deficit.

4.2. Short-run relationship among the variables

We perform the following ECM test to examine short-run fluctuations.

The estimates of EquationEquation (5)(5)

(5) are presented in Table . Similar to long-run estimates, ECM estimates show the statistical significance of GDP and the insignificance of the exchange rate. The central variable, REER*ECB, is also negative and significant in all the models except Model E, confirming the contractionary effect of currency depreciation on exports due to the increased value of liabilities in foreign currency. Furthermore, we find a direct relationship between financial development and exports (REER*FD), but the influence turns negative when the currency depreciations are large (Model C). We also observe the substantial and negative impact of the non-linear component of ECB on India’s exports. Overall the short-term estimates confirm the long-run relationship.

The computed ECM coefficients in the models, which range between −0.653 and −0.709, are statistically significant. The value of the ECM coefficient implies a higher speed of adjustment of the short-run discrepancies corrected in the long-run to attain equilibrium. The statistical significance and the negative sign of the ECM coefficients confirm the presence of a short-run equilibrium relationship between EXPORTS and GDP, REER*ECB, REER*FD, and REER*FD2. These results are consistent with our long-run estimates.

Overall, the results suggest that the financial development and bank-lending channel increase India’s exports, but the additional availability of credit is causing a fall in exports when there is a large exchange rate depreciation. The value of the adjusted R2 suggests that the model is a good fit, and the F-value reveals the correct specification. The model is free from the problem of autocorrelation, as confirmed by the Durbin-Watson statistic (Table ).

We also examine export performance in the presence of ECBs and financial development using firm-level data to ensure the robustness of the baseline results that use macro-level data. We employ the dynamic panel regression of Arellano and Bond (Citation1991).Footnote5 We find theoretically consistent signs of the variables, and the firm-level analysis corroborates our macroeconomic inferences (Table ). The diagnostic check results show that the models are free from serial correlation and endogeneity, which further confirms the robustness of the models and the overall analysis.

Table 8. Firm-specific determinants of the export supply function

The RBI has been making several changes related to the end-use of ECBs. About 50–70 percent of the end-use requirement of ECBs is allocated to activities such as import of capital goods, power, modernisation, overseas acquisition, and onward/sub-lending. The end-use of ECBs on overseas acquisition indicates that Indian firms, including small and medium enterprises (SMEs), acquire new technologies from foreign markets to upgrade productivity. Similarly, we observe the utilisation of ECBs for new projects in the power, infrastructure, and specified service sectors (Table , Appendix). An investigation of end-use of ECBs and its relation with exports offers fascinating insights, but such an analysis is beyond the scope of the present work.Footnote6

The natural hedge is an important aspect related to export firms. The potential increase in export earnings protects the firms from the adverse effect of currency depreciation on liabilities denominated in foreign currency. Our findings established the deterioration of the balance sheets of export firms due to currency depreciation through the foreign liability channel. In other words, the dependency on ECBs restricts the realisation of export revenue stemming from exchange rate depreciation. Therefore, the mandatory minimum level of hedging for firms without and with export sales is inevitable. This hedging is possible when derivative markets are developed. The offshore financial derivatives markets in India are illiquid and costly. Developing vibrant derivative markets has to be a priority for regulators.

We documented how the lack of financial development and a growing reliance on ECBs affects exports. To reduce the problem, the development of a robust domestic debt market in India is indispensable. The export firms will reap the fruits of depreciation only when local credit is readily available at a low cost for a desirable maturity period. Patnaik et al. (Citation2015) and Sahoo (Citation2015) also opine that strengthening the nexus between bond, currency, and derivatives makes hedging low-cost and attractive to firms. Our suggestion of strengthening domestic bond market is consistent is consistent with work of Venkatesh and Hiremath (Citation2020). Therefore, the fall in India’s exports following exchange rate depreciation, as evident from the present analyses, demands changes in the current policies related to ECBs.

There have been recent policy measures to ease the controls on capital to mitigate currency mismatches. According to Pandey et al. (Citation2015), out of 76 capital flow measures in India, 68 were eased, and eight were tightened between 2003 and 2013. They also found further relaxation of norms for firms to utilise the ECB route. Furthermore, the latest data reveals a decline in the hedge ratio from 35 percent in 2013 to 14 to 15 percent in 2014, posing a severe threat to India’s financial stability (Patnaik et al., Citation2015). Although the introduction of the rupee-denominated bondsFootnote7 is a vital step in minimising exchange rate risks; yet, it does not appear to be a game-changer as lower-rated companies still find it challenging to raise funds from this source (Roy, Citation2016). The policies related to ECBs require regular supervision and regular monitoring by the regulator.

The findings of the study have important practical implications. The export firms need to improve their core competence to increase export sales instead of relying merely on exchange rate depreciation to boost exports. Such depreciation is of little help when these firms borrow in foreign currency. The firms need to use hedging instruments instead of expecting the central bank to intervene in the forex market to rescue them.

5. Conclusion

We investigated the nexus between exports, ECBs, and financial development using both macroeconomic and firm-level data. We observed that currency depreciation results in the shrinking of exports because of a reliance on external finance by Indian firms. The level of financial development has a positive impact on exports, but the non-linear form suggests the diminishing effects of additional credit availability on exports when the domestic currency is depreciating. Our findings show the usefulness of foreign debt dynamics in explaining the currency–export puzzle. Our results call for the development of foreign currency derivatives, better access to rupee-denominated bonds, and the development of domestic credit markets to improve exports. In this research, we could not inquire into the relationship between the end-use of ECBs and exports due to several data constraints. Another limitation of the present work is that it is confined to macro and firm-level analysis and does not extend to industry- and sector-specific analysis. The limitations indicate the scope for future study. Future research can also focus on examining firm-level credit constraints and how these constraints interact with macroeconomic constraints in the fixed-income market. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis of credit and exports provide robust policy suggestions.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of the paper was presented in 53rd Annual Conference of the Indian Econometric Society held at National Institute of Science Education and Research, Bhubaneswar during December 22-24, 2016. We thank the participants for the suggestions. We thank the anonymous reviewers for the impactful comments on the earlier version of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ashis Kumar Pradhan

Ashis Kumar Pradhan is an Assistant Professor at Maulana Azad National Institute of Technology, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. He works in the area of open economy Macroeconomics and Financial Economics. He has published articles in reputed national and international journals.

Gourishankar S Hiremath

Gourishankar S. Hiremath is an Associate Professor of Finance at IIT Kharagpur and alumnus of the University of Hyderabad. Hiremath is the author of “Indian Stock Market – An Empirical Analysis of Informational Efficiency.” Hiremath was a visiting fellow at Cambridge Judge Business School. Hiremath's areas of research interest include financial economics, open economy macroeconomics and political economy with a primary focus on interaction of market efficiency, corporate finance and international capital flows.

Notes

1. Our study is subject to the availability of data. The data on export credit and short-term pre-shipment and post-shipment credit are not available. Furthermore, the data on interest rate subvention schemes that provide added advantage to specific industries availing export credit would have given more intriguing insights.

2. We deflate the exports of goods and services using the export price index, whereas the rest of the variables are deflated using the consumer price index.

3. The sign of the coefficient of the ΔREER can also be negative because a small degree of depreciation decreases the supply of exports as the capital imports used in the production becomes costlier.

4. Phillips and Hansen (Citation1990), Phillips (Citation1991), and Phillips and Loretan (Citation1991), among others, propose cointegration techniques.

5. The panel unit root test statistics indicate stationarity of all the variables. The results are not reported to save space but available upon request from the authors.

6. To gain such insight, a sector-level analysis in which firms grouped as per the ECB end-use is required. However, we have not carried out such an analysis in this paper due to several data constraints. The unavailability of data under each group also restricts the comparative analysis and poses challenges for meaningful estimations. We thank an anonomyous reviewer for the insight on this issue.

7. HDFC Ltd., NTPC, and Adani Transmission issued Masala bonds and raised INR 30, 20, and 5 billion, respectively.

References

- Aghion, P., Bacchetta, P., & Banerjee, A. (2001). Currency crises and monetary policy in an economy with credit constraints. European Economic Review, 45(7), 1121–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(00)00100-8

- Arcand, J.-L., Enrico, B., & Panizza, U. (2012). Too Much Finance? Working Papers 161. International Monetary Fund.

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968

- Baldwin, R., & Krugman, P. (1989). Persistent trade effects of large exchange rate shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 635–654. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937860

- Beck, T. (2002). Financial development and international trade: Is there a link? Journal of International Economics, 57(1), 107–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(01)00131-3

- Berman, N., & Berthou, A. (2009). Financial market imperfections and the impact of exchange rate movements on exports. Review of International Economics, 17(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2008.00781.x

- Bernanke, S. B., Gertler, M., & Gilchrist, S. (1999). The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. In J. B. Taylor & M. Woodford (Eds.), Handbook of macroeconomics (Vol. 1, pp. 1341–1393). North-Holland.

- Brooks, W., & Dovis, A. (2020). Credit market frictions and trade liberalizations. Journal of Monetary Economics, 111, 32-47. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2019.01.013

- Buera, F. J., & Shin, Y. (2013). Financial Frictions and the Persistence of History: A Quantitative Exploration. Journal of Political Economy, 121, 221-272. 2 doi:10.1086/670271

- Caballero, J. R., & Krishnamurthy, A. (2003). Excessive Dollar Debt: Financial development and underinsurance. The Journal of Finance, 58(2), 867–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00549

- Changyong, F. E. N. G., Hongyue, W. A. N. G., Naiji, L. U., Tian, C. H. E. N., Hua, H. E., & Ying, L. U. (2014). Log-transformation and its implications for data analysis. Shanghai archives of psychiatry, 26(2), 105.

- Chit, M. M., & Judge, A. (2011). Non‐linear effect of exchange rate volatility on exports: The role of financial sector development in emerging East Asian economies. International Review of Applied Economics, 25(1), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2010.483463

- Chit, M. M., Rizov, M., & Willenbockel, D. (2010). Exchange rate volatility and exports: New empirical evidence from the emerging East Asian economies. The World Economy, 33(2), 239–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01230.x

- Chou, L. W. (2000). Exchange rate variability and china’s exports. Journal of Comparative Economics, 28(1), 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcec.1999.1625

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(336), 427–431. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01621459.1979.10482531

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1981). Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica, 49(4), 1057–1072. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912517

- DIPP. (1991). Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade. Retrieved from https://dipp.gov.in/acts-and-rules/press-notesfdi-circular/erstwhile-press-notes-1991

- Duttagupta, R., & Spilimbergo, A. (2004). What happened to Asian exports during the crisis? IMF Staff Papers, 51 (1), 72–95. International Monetary Fund. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2307/30035864

- Eichengreen, B., & Hausmann, R. (1999). Exchange rates and financial fragility. Working Paper, w7418. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Engle, F. R., & Granger, C. W. J. (1987). Co-Integration and error correction: Representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica, 55(2), 251–276. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913236

- Forbes, J. K. (2002). How Do Large Depreciations Affect Firm Performance? Working Paper 9095. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Ghei, N., & Pritchett, L. (1999). The Three Pessimisms: Real exchange rates and trade flows in developing countries. In L. Hinkle & P. Montiel (Eds.), Exchange rate misalignment: Concepts and measurement for developing countries (pp. 467–96). Oxford University Press.

- Goldstein, M., & Turner, P. (2004). Controlling currency mismatches in emerging markets. Columbia University Press.

- Hiremath, G. S. (2019, October 18). What is the way forward for the ailing banking sector in India? CNBCTV18.com. https://www.cnbctv18.com/views/what-is-the-way-forward-for-the-ailing-banking-sector-sbi-hdfcbank-pnb-nbfcs-4527321.htm

- India Brand Equity Foundation. (2020). Indian financial services industry report. India Brand Equity Foundation. https://www.ibef.org/industry/financial-services-india.aspx

- Jarque, C. M., & Bera, A. K. (1987). A test for normality of observations and regression residuals. International Statistical Review/Revue Internationale De Statistique, 55(2), 163–172. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1403192.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A05f8df441c9ea775aeb0104706169825

- Johansen, S. (1991). Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica, 59(6), 1551–1580. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938278

- Kletzer, K., & Bardhan, B. (1987). Credit markets and patterns of international trade. Journal of Development Economics, 27(1–2), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(87)90006-X

- Krueger, A., & Tornell, A. (1999). The role of bank restructuring in recovering from crises: Mexico 1995–98, Working Paper w7042. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Krugman, P. (1999). Balance sheets, the transfer problem, and financial crises. International Tax and Public Finance, 64(4), 59–472. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-011-4004-1_2.

- Kunieda, T., & Shibata, A. (2014). Credit market imperfections and macroeconomic instability. Pacific Economic Review, 19(5),592-611. doi:10.1111/paer.2014.19.issue-5

- Kwiatkowski, D., Peter, P. C. B., Schmidt, P., & Shin, Y. (1992). Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? Journal of Econometrics, 54(1–3), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(92)90104-Y

- Morimune, K., & Mantani, A. (1995). Estimating the rank of cointegration after estimating the order of a vector autoregression. The Japanese Economic Review, 46(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5876.1995.tb00011.x

- Pandey, R., Pasricha, G. K., Patnaik, I., & Shah, A. (2015). Motivations for capital controls and their effectiveness. Working Papers. Bank of Canada. Retrieved April 12, 2016. http://EconPapers. repec.org/RePEc:bca:bocawp:15-5.

- Patnaik, I., Shah, A., & Singh, N. (2015). Foreign currency borrowing by Indian firms. Working Paper. International Growth Center.

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1998). An autoregressive distributed-lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Econometric Society Monographs, 31, 371–413. https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=61x_K6mPpgwC&oi=fnd&pg=PA371&dq=Pesaran,+Hashem+M.,+and+Yongcheol+Shin,+1998,+An+autoregressive+distributed-lag+modelling+approach+to+cointegration+analysis,+Econometric+Society+Monographs+31,+371-413.&ots=XVJaK0SIdE&sig=aR_FNnc-14zz1ZKBIe2YNdGlNlM#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Phillips, P. C. B. (1991). Bayesian routes and unit roots: De rebus prioribus semper est disputandum. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 6(4), 435–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.3950060411

- Phillips, P. C. B., & Hansen, B. E. (1990). Statistical inference in instrumental variables regression with I (1) processes. The Review of Economic Studies, 57(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297545

- Phillips, P. C. B., & Loretan, M. (1991). Estimating long-run economic equilibria. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(3), 407–436. https://doi.org/10.2307/2298004

- Phillips, P. C. B., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/75.2.335

- Pradhan, A. K., & Hiremath, G. S. (2020a). External commercial borrowings by the corporate sector in India. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1987

- Pradhan, A. K., & Hiremath, G. S. (2020b). Why do Indian Firms Borrow in Foreign Currency? Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 14(2), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973801020904492

- Quinn, B. G. (1988). A note on AIC order determination for multivariate autoregressions. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 9(3), 241–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9892.1988.tb00468.x

- Radelet, S., & Sachs, J. (1998). The onset of the East Asian financial crisis. No. w6680. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 559–586. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/116849.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A87325d223e924a9bd6a175e6186e825b

- Ramachandran, M., & Srinivasan, N. (2007). Asymmetric exchange rate intervention and international reserve accumulation in India. Economics Letters, 94(2), 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2006.06.040

- RBI. (2017). Financial Sector: Regulations and Developments. 21 December, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=888

- Roy, A. (2016, August 24). Only major firms relishing masala bonds. Business Standard.

- Sahoo, M. S. (2015). Report Of The Committee To Review The Framework of Access to Domestic and Overseas Capital Markets, Phase II, Part II: Foreign Currency Borrowing, Report III. Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

- Samargandi, N., Fidrmuc, J., & Ghosh, S. (2015). Is the relationship between financial development and economic growth monotonic? Evidence from a sample of middle-income countries. World Development, 68, 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.010

- Sauer, C., & Bohara, A. K. (2001). Exchange rate volatility and exports: Regional differences between developing and industrialized countries. Review of International Economics, 9(1), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9396.00269

- Shin, H. S., & Zhao, L. (2013). Firms as surrogate intermediaries: Evidence from emerging economies. Mimeograph. Princeton University.

- Song, Z., Storesletten, K., & Zilibotti, F. (2011). Growing like china. American economic review, 101(1),196-233. doi:10.1257/aer.101.1.196

- Stiglitz, J. E. (1998). Sound Finance and Sustainable Development in Asia. World Bank.

- Tang, K. B., Tan, H. B., & Naseem, N. A. M. (2013). The effect of foreign currency borrowing and financial development on exports: A dynamic panel analysis an Asia-Pacific Countries. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 18(3), 460–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2012.742707

- Venkatesh, H., & Hiremath, G. S. (2020). Currency mismatches in emerging market economies: Is winter coming? Buletin Ekonomi Moneter Dan Perbankan, 23(1), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.21098/bemp.v23i1.1182

- Wasmer, E., & Weil, P. (2004). The macroeconomics of labor and credit market imperfections. American Economic Review, 94(4),944-963. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/0002828042002525

- World Bank. (2020). Global Financial Development Report 2019/2020: Bank Regulation and Supervision a Decade after the Global Financial Crisis. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/gfdr/report

Appendix

Figure A1. Export growth and Exports as a proportion to GDP.

Figure A2. Exchange rate between the US Dollar to Indian Rupees.

Table A3. End-use pattern of ECBs