?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The research about responsible consumption began during the 70’s decade, but recently it became extremely relevant due to global warming and increasing social demands. In this regard, our research tries to determine the effects of moral outrage on consumers’ perceived values of socially irresponsible companies. Once we introduce our research problem, we conduct in the first stage a literature review, to construct a conceptual model for responsible consumption. In the second section, we verified our previous conceptual model at a practical level, applying a quantitative approach through structural equations. Specifically, we verify the effects of the moral outrage, on consumers’ perceived values, in the context of a price cartel, that operated for more than 14 years, involving the biggest five producers of toilet paper, napkins, diapers, and handkerchiefs in Colombia. The findings show that the moral outrage due to corporate social irresponsibility, affect the consumer’s perceived values, related to (i) the consumer loyalty, and (ii) the consumer social and economic costs. Based on these findings, we suggest some implications for marketing practitioners, public policy-makers, shareholders and CEOs. Furthermore, we also recommend the future inclusion of the control mechanisms, and the technical cycle for products and services, in the responsible consumption studies.

Public interest statement

Responsible consumption has recently become a relevant concern due to global warming and increasing social demands. Consequently, we try to understand the effect of moral outrage on consumers’ perceived values of socially irresponsible companies. With this purpose, we first try to understand the current status of the theoretical discussion about responsible consumption. Finally, we apply these findings to the case of a price cartel, that operated for more than 14 years, involving the biggest five producers of toilet paper and related products in Colombia. Where we wondered how consumers perceived companies’ behaviour, finding that moral outrage affected consumer loyalty and perceived social and economic costs. It means that Marketing practitioners, policy-makers, shareholders and CEOs can consider these findings. For example, they may include it while referring to the decision-making process, brand management, reputational issues, between others.

1. Introduction

The debate around responsible consumption began during the decade of the 70s, but still alive until now, where it becomes hugely relevant with global warming, and the increasing social demands. In the beginning—i.e., during the 70’s-, the debate was scattered. Some authors, for example, defined responsible consumption, as the rational and efficient use of resources in the framework of the human population’s needs (Fisk, Citation1973). At the same time, others characterised the socially conscious consumer as a person that can be identified by personality, attitude, and socioeconomic traits (Webster, Jr., Citation1975). While, some synthesised the emerging theoretical efforts as proposals with “ethical and moral baseline” (Golob et al., Citation2019; Muncy & Vitell, Citation1992). Where, they define consumer ethics as “the moral principles and standards that guide the behaviour of individuals or groups as they obtain, use, and dispose of goods and services” (Muncy & Vitell, Citation1992), and suggest that managers must focus on those stakeholders affected by the entrepreneurial activity (Cortina, Citation2009). Nevertheless, the discussion does not stop at this point. Recently, some experts discussed how consumption itself becomes a site of political dispute (Harrison et al., Citation2005, p. 5).

Consequently, we discover five different perspectives or themes while referring to responsible consumption as a construct (Gupta & Agrawal, Citation2018). The (1) first one relates to the social perspective, where some authors focus on the socially conscious consumer (Roberts, Citation1995), and others review the socially responsible consumption (Webb et al., Citation2008). The (2) second refers to the ethical perspective, which includes, for example, the consumer ethics (Muncy & Vitell, Citation1992), or recently the ethically minded consumer studies (Sudbury-Riley & Kohlbacher, Citation2016). The (3) third perspective corresponds with the sustainability perspective, which refers, for example, to the sustainable consumption (Balderjahn et al., Citation2013). The (4) fourth perspective is the green one, where the authors analysed, between others, the green consumption (Kim et al., Citation2012). Finally, the (5) fifth perspective includes the environmental issues, related for example, to the eco-habits (Carfagna et al., Citation2014), environmental consumer behaviour (Gatersleben et al., Citation2002), and environmentally responsible consumer (Stone et al., Citation1995).

In this regard, some authors that have recently review responsible consumption include some recommendations for future research. Between them, are (1) Golob et al. (Citation2019) that review how normative factors induce consumers to act according to social responsibility principles during the buying stage. They suggest the future inclusion of personal values and beliefs when analysing socially responsible purchasing behaviour. (2) Prendergast and Tsang (Citation2019) try to explain the various categories of socially responsible consumption. The authors suggest that public policy-makers and marketers may create specific devices that promote responsible consumption. (3) Gupta and Agrawal (Citation2018) conceptualise environmentally responsible consumption to develop a standardised scale. They promote their future application by governmental and non-governmental bodies, policy-makers, environmental groups, and businesses that try to change consumer behaviours. (4) Schlaile et al. (Citation2018) develop theoretical research that tries, between others, to re-conceptualise the Consumer social responsibility from Max Weber’s approach, recover moral principles, and identify its constraints. They conclude, highlighting the importance of analysing consumer behaviour in developing regions, where consumers do not have sufficient “power” to act responsibly. (5) Song and Kim (Citation2018) create a predictive model that explains the impact of good traits (i.e., virtuous and personality traits) on socially responsible consumption. They propose the future inclusion of other variables like emotional or social intelligence, gratitude, compassion, transcendence, gender, generation, and ethnic origin, in the research field of socially responsible consumption. At last, (6) Agrawal and Gupta (Citation2018) identify consumers’ environmentally responsible consumption behaviours. They recommend cross-national studies that pay special attention to “why” and “when” do consumers undertake environmentally responsible consumption.

Once recognised the perspectives of the study about the responsible consumption, and the current research gaps, we select corporate social responsibility—CSR- construct as the theoretical framework of our study. This selection is supported, between others, by the possible inclusion of the environmental, social, economic, stakeholder and voluntariness dimensions that CSR proposes (Dahlsrud, Citation2008). Furthermore, we support its election by the anthropocentric purpose of the CSR studies, which differs from the eco-centric purpose of corporate sustainability—CS- (Montiel, Citation2008). Our selection also recognises the traditional controversy between marketing ethics and social responsibility—SR- (Carrigan & Attalla, Citation2001; Mohr et al., Citation2001, p. 70). Consequently, we try to take advantage of the literature available about corporate social responsibility and the critical role of the consumers in its implementation (Vitell, Citation2015). A consumer that goes beyond the locus of individual consumers, to other consumer forms, like families, governments, and consumer groups, among others (Caruana & Chatzidakis, Citation2014).

In this theoretical context, we wonder how moral outrage affects consumer’s perceived values of socially irresponsible companies. With this purpose, we introduce in the present stage the research problem, its theoretical backgrounds, and research gaps. In the second stage, we conduct a literature review about “responsible consumption”, which tries to understand the present perspectives of the study. Then in the third stage, we describe the research methodology, conduct the empirical verification—in a price cartel of care, hygiene and cleanliness products in Colombia-, and relate the obtained results. Finally, in the fourth and fifth stage, we present the discussion of our findings with other authors, and then the conclusions.

2. Literature review and selection of the theoretical framework

Once introduce the research problem, in this stage, we conduct a literature review about responsible consumption. Here we begin with bibliometric analysis. Then we continue with discourse analysis and finally, with the choice of a theoretical framework for corporate social irresponsibility and consumer’s perceived values. In this sense, we first develop a bibliometric analysis using the software VosViewer®, where we apply mathematical and statistical methods to research papers, books, chapters, conference proceedings, and other research communications. Specifically, we try to measure the quantity, performance and other structural indices that help us inferring links between research communications, authors, and other research topics.

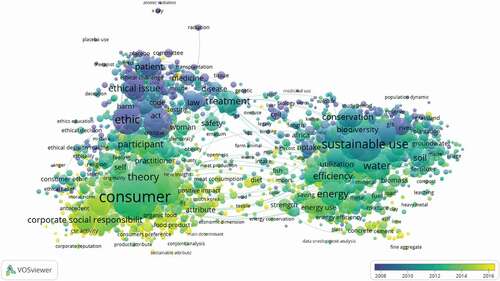

For this purpose, we define the next search equation, applying the citation pearl growing technique (Schlosser et al., Citation2006), ((“responsib*” OR “liable” OR “amenabl*” OR “accountabl*” OR “in charge” OR “sustainab*” OR “answerabl*” OR “ethic*” OR “moral*” OR “staid” OR “sober”) AND (“consum*” OR “use” OR “intak*” OR “uptake*” OR “purch*”)). We look for these research criteria in the titles of the publications of the main Web of Science database, Derwent Innovations Index, Korean Journal Database, Russian Science Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index, and Scopus. Where we found, at the beginning of 2020, 19.693 publication titles—i.e., in WOS 8.074 and 11.619 in Scopus- that include words of our search equation. With this information, we run VosViewer® software, to obtain the knowledge map for corporate social irresponsibility and consumer’s perceived values (see ).

Figure 1. Knowledge map for responsible consumption

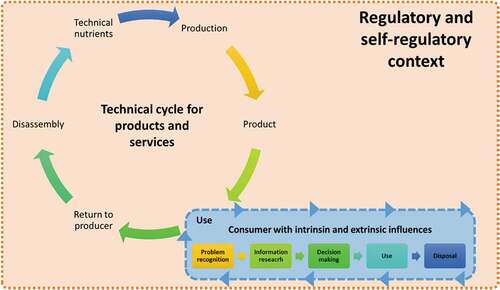

According to the year of its occurrence, VosViewer® classifies the most common terms, as is shown in the knowledge map of . However, the software can also classify it according to clusters that the software creates itself. In this specific case, the software created four clusters. The first one contains terms like consumer, behaviour, company, attitude, perception and corporate social responsibility. The second relates to terms like sustainable use, water, region, land, land use, agriculture, conservation, soil, species, plant, and natural resource. The third refers to terms like ethic, responsibility, treatment, ethical issue, participant, patient, care, and law. Finally, the fourth comprises energy, efficiency, waste, energy consumption, property, emission, cycle, utilisation, uptake, and biomass. We summarise these clusters, like those related to (1) the consumer -e.g., customers, users and buyers- with his intrinsic and extrinsic influences or motives, (2) the control mechanisms, self-appointed or mandatory, and (3) the technical cycle for products and services, that relates with the whole products and services life cycle.

In this regard, we find some authors who complement our discussion. Among them are those who focus on the pre, during and post-purchase stages, and review the intrinsic and extrinsic influences that influence consumers, such as (1) Sangvikar et al. (Citation2019), that discovered how customer satisfaction, high costs, and unawareness affects sustainable products. (2) Wang et al. (Citation2019) sustainable customers while studying their retention from the brand association, loyalty, attachment, and preference perspective. (3) Maciejewski et al. (Citation2019) try to apply sustainable values as segmentation variables, and find that those customers classify as “responsible, aspiring to be connoisseurs” have greater sustainable consumption values, than those classified as “consumerists, connoisseurs, but not at any price”. (4) Yamoah and Acquaye (Citation2019) developed a sustainable product purchase behaviour mode based on inhibitors/promoters. They also found different typologies of inhibitors/promoters and explained the gap between claimed purchase behaviour and actual purchase behaviour based on the inhibitors. (5) Afzal et al. (Citation2019) review sustainability from the competitiveness lenses and define sustainability markets from individual materialistic values. (6) Su et al. (Citation2019) propose sustainability and consciousness issues as predictors in the market segmentation of consumers of the generation Z. (7) Sarti et al. (Citation2018) also try to segment consumers, according to sustainable and healthy habits but add a new category: the product labels. (8) Polimeni et al. (Citation2018) discover that economic value, wealth, and educational level are important factors for choosing sustainable products. (9) Del Giudice et al. (Citation2018) examine consumer preferences toward environmental or social certifications labelled on products as sustainability indicators. They find that consumers prefer products with sustainability certifications and that social certifications do not affect the price, while environmental ones have. (10) Cohen and Muñoz (Citation2017) propose market entry strategies for the conscious consumer, by reviewing its size and growth in the last decade and some failure and success cases. (11) Koszewska (Citation2016) discover that consumers’ attitudes influence their willingness to pay a premium for sustainable products and their recognition of ecological and social labels. (12) Koszewska (Citation2013) developed a consumer typology based on their buying habits and ecological and social criteria. Furthermore, (13) Venkatesan (Citation2016) propose the study of the topic from the perspective of the formation of generational behaviours, with a multidisciplinary approach.

On the other hand, we find other authors that review the control mechanisms related to responsible consumption. It is essential to say that these control mechanisms can be self-appointed or mandatory. Among them, we note (1) Coates and Middelschulte (Citation2019). They believe that international cooperation among industry peers can contribute to attaining the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and discuss the competition laws’ role, as the inhibitors of this long-awaited cooperation. (2) Zorell (Citation2020) proposes and reviews the term “Political consumers”, understanding them as those who base individual purchasing decisions on environmental, ethical and socio-political. (3) Wróblewski and Dacko-Pikiewicz (Citation2018) study the sustainable consumption of the cultural services, in a context of various legal regulations that promote it, to finally conclude that consumer behaviour does not follow this concept. (4) Tjiptono (Citation2018) while reviewing responsible consumption in an emerging market, highlights three challenges (a) understanding of consumer social responsibility, (b) targeting the “right” responsible consumption segments, and (c) helping consumers to be ready to be green. (5) Alshurideh et al. (Citation2017) analysed the incidence of ethical issues in advertising children’s products. They found that sexual appeals and child abuse are the main factors that affect parents’ acceptance of product advertisings. (6) García-Madariaga and Rodríguez-Rivera (Citation2017) suggest that some corporate social responsibility actions—e.g., those related to core business and critical stakeholders- can lead to better financial performance. Moreover, (7) Doni and Ricchiuti (Citation2013) discover that despite the people’s belief, an increment in the level of social responsibility of a market actor may trigger an increase in firms’ total clean-up but a reduction in social welfare.

Meanwhile, we find other authors who study the technical cycle for products and services and consider its life cycle. Among them are (1) Bryła (Citation2019) who develops the concept of sustainable consumption from the perspective of regional ethnocentrism, understanding, the last one as the intention to purchase not only foreign products but also regional products. (2) Mkhize and Ellis (Citation2018) characterise the known as “green gap”—when referring to the gap between the express concern for the environment, and the real consumer actions-, determining the root causes of this situation and making some recommendations for practitioners. (3) Kamboj and Rahman (Citation2017) while review sustainable innovation issues, define as mediator sustainable consumption. Furthermore, (4) Tseng et al. (Citation2016) propose the discussion about the firm’s (a) operational attributes, (b) sustainable consumption and production practices, and on (c) evaluation and implementation methods while referring to the sustainable consumption and production. Once completed the tour through the three proposed dimensions, next in , we present our conceptual model for responsible consumption.

Our conceptual model for responsible consumption relates, through the use, the consumer with his intrinsic and extrinsic influences or motives, to the technical cycle for products and services (Solomon, Citation2013). The latter -that is, the technical cycle of products and services- is also related or contained in the regulatory and self-regulatory context, as one of the possible strategies to be implemented (McDonough & Braungart, Citation2005). In this theoretical context, we decide to combine the mentioned perspectives, specifically the first, that relates to the consumer -e.g., customers, users and, buyers- with his intrinsic and extrinsic influences or motives, and the second that refers to the control mechanisms, self-appointed or mandatory, in a particular empirical context, where corruption and corporate social irresponsibility has been demonstrated. We specifically refer to a price cartel in Colombia, South America. This cartel operated for more than 14 years and involved the five biggest Colombian companies, devoted to toilet paper, napkins, diapers, sanitary napkins, and handkerchiefs production (Semana, Citation2014). In the next section, we describe the research methodology and the obtained results.

3. Methodology and results

In this stage, once we developed the research problem and the literature review about corporate social irresponsibility and consumer perceived values, we present next in the research protocol proposed to solve the research question as mentioned above.

Table 1. Research protocol for the quantitative approach

We collect the data during 2018 in Medellín-Colombia—zip code 050001 to 050048-, between 1.112 consumers of products like toilet paper, napkins, diapers, sanitary napkins, and handkerchiefs in Colombia, South America-. 53,69% of the respondents were female, and 46.31% were male, that live in the six socioeconomic levels. Next, we present the findings for the Exploratory Factor analysis—EFA- in the first part, and in the second one, we provide the Confirmatory Factor Analysis—CFA-.

3.1. Findings of the exploratory factor analysis

Before we introduce the findings of the exploratory factor analysis—EFA-, it is crucial to say that in the structural equation model that we are trying to verify, we review the incidence of the moral outrage on the consumer’s perceived values of socially irresponsible companies. We represent the moral outrage at corporate social irresponsibility, with unobserved or latent variables like moral outrage, blame attributions, greed, fairness, Severity, and Negative word-of-mouth. Each of these unobserved or latent variables is defined with observed variables, directly gathered with the consumers through the survey previously designed by Antonetti and Maklan (Citation2016). Besides, we describe the consumer’s perceived values, with unobserved or latent variables like quality value, price value, emotional value, social value, consumer satisfaction, and consumer loyalty. Each of these latent variables is defined with observed variables, directly gathered with the consumers through the survey previously designed by Hassan et al. (Citation2016).

In this context, we first apply to the collected data an exploratory factor analysis—i.e., EFA-. The EFA is designed for cases where links between the observed and latent variables are unknown or uncertain (Byrne, Citation2010, p. 5). Therefore, we apply it to determine how, and to what extent, the observed variables are linked to their underlying factors, future latent variables. These factors are formed by the minimal number of factors that underlie (or account for) covariation among the observed variables (Byrne, Citation2010). In this context, next, we verify the adequacy of the model, through the KMO, Chi-square, df—i.e., degrees of freedom- and Cronbach alpha results for the collected data, using the SPSS® software for data analysis.

Previous findings support the adequacy of the model, for example, a KMO—i.e. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin- above 0.9, shows good sampling adequacy (Howard, Citation2016). Furthermore, the Cronbach alpha, where are suggested values greater than 0.7, shows the extent to which each item is measuring the same concept as the comprehensive questionnaire (Bryman & Cramer, Citation2001; Lazenbatt et al., Citation2005). Once we verified the adequacy of the model, next, we present in the pattern matrix.

Table 2. Pattern matrix

The interpretation of the factor pattern matrix has multiple effects. For example, it helps to identify whether items measure single or multiple factors—in SEM we prefer that items measure single-, and adequate construct validity (Schmitt & Sass, Citation2011, p. 111). In this sense, we choose Promax as rotation criterion, and Maximum likelihood as a method, to finally obtain the aforementioned table, with six new factors or constructs. Three of them define the moral outrage at corporate social irresponsibility, with the items or observed variables named QA_1, QA_2, QA_3, QB_2, QB_3, QC_2, QC_4, QD_1, QD_3, QE_1, QE_2, QE_3, QF_1, QF_2, and QF_3. Furthermore, the other three related to the consumer’s perceived values and noted as Q1_1, Q1_2, Q1_3, Q2_1, Q2_2, Q3_1, Q4_2, Q5_1, Q6_1, Q6_2, Q6_3, Q6_4. Finally, it is essential to say that the EFA analysis excludes some of the items or observed variables; this is the case of Q4_1, QB_1, QC_1, QC_3, QD_2.

3.2. Findings of the confirmatory factor analysis

Before introducing the findings of the confirmatory factor analysis—CFA-. In the structural equation model that we are trying to verify, our previous knowledge about the topic is essential to postulates relations between the observed variables and the latent variables, and for tests this hypothesised structure statistically (Byrne, Citation2010, p. 6). Once create the model, the next step is to determine the adequacy of its goodness-of-fit to the sample data.

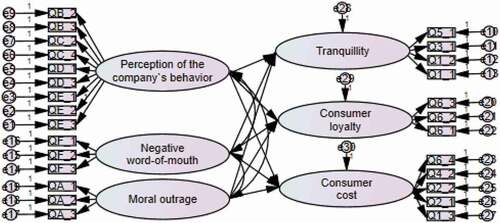

In this context and in the framework of the hypothesis that we want to verify, related to the research question. We construct two models, in the first one—shown in , we represent the basic relations that we want to verify, where moral outrage at corporate social irresponsibility influences consumer’s perceived values. In this model, moral outrage at corporate social irresponsibility is represented with 15 observed variables of Antonetti and Maklan (Citation2016) test, and three unobserved or latent variables defined as (1) perception of the company’s behaviour, (2) negative word-of-mouth, and (3) moral outrage. Meanwhile, the consumer’s perceived values are represented by 12 observed variables of Hassan et al. (Citation2016) survey, and three unobserved or latent variables defined as (1) tranquillity, (2) consumer loyalty, and (3) consumer costs.

Figure 3. Path diagram for the relation between outrage at corporate social irresponsibility and consumer perceived values—Model 1

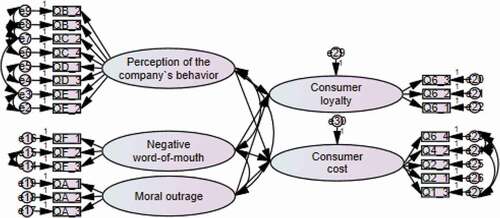

Moreover, in the second model, and taking into account that we use two instruments previously verified (Antonetti & Maklan, Citation2016; Hassan et al., Citation2016), we decided to test for the validity of factorial structure, trying to determine how items measure a particular factor (Byrne, Citation2010, p. 97). In this process, we test for factorial validity through the modification indices and the standardised residual covariances, as is shown in .

Figure 4. Path diagram with CFA analysis for the relation between outrage at corporate social irresponsibility and consumer perceived values—Model 2

In , we have correlated some errors, withdrawn some observed variables and extracted a latent variable defined as “tranquillity”. These actions have a direct effect on the model fit, as can be seen in . Where we present, the “root mean square error of approximation”, denoted as RMSEA, which tells us about how well the model estimates would fit the population’s covariance matrix (Hooper et al., Citation2008, p. 54).

Table 3. Root mean square error of approximation for the model 1 and the model 2

In this context, an RMSEA value close to 0.06 or less seems to be a good model fit (Hooper et al., Citation2008, p. 54). A context in which model 2, with an RMSEA of 0.052, can be considered a model that fits the population’s covariance matrix. It indicates—i.e., model 2- that in effect, moral outrage influences some of the consumer’s perceived values of socially irresponsible companies. Specifically, the moral outrage at corporate social irresponsibility related to (1) perception of the company’s behaviour, (2) negative word-of-mouth, and (3) moral outrage. Moreover, the consumer’s perceived values related to (1) consumer loyalty and (2) consumer costs. A fact that leaves aside the tranquillity, as a construct that is not affected by the moral outrage at corporate social irresponsibility.

4. Discussion with other authors

Our findings, specifically (1) our research approach that considers the consumer’s perceived values agree with Golob et al. (Citation2019). Who calls for the inclusion of personal values and beliefs when analysing socially responsible purchasing behaviour. (2) The empirical context that we work, especially its sample in Colombia, South America, attends the suggestion of Schlaile et al. (Citation2018), that proposed the importance of analysing consumer behaviour in developing regions, where consumers do not have sufficient “power” to act responsibly. (3) The variables that we selected for the research approach, for example, the perceived value and its resulting latent variable “consumer cost” that refers to economic and social costs, can be homologated with the variable “social intelligence” that was proposed by song and Kim (Citation2018). (4) The implications of our findings for the practitioners, for example, the possible reduction of consumer loyalty as a consequence of moral outrage, can be taken into account by marketers, as Prendergast and Tsang (Citation2019) suggested. (5) Our results, specifically the incidence of moral outrage on perceived values as loyalty, agree with the previous findings of Wang et al. (Citation2019). Finally, (6) our findings agree with Tjiptono’s (Citation2018) suggestions, of review this kind of issues in an emerging market, that needs to begin with a better understanding of consumer social responsibility.

On the other hand, (1) our research approach disagrees with the proposal of Gupta and Agrawal (Citation2018) who conceptualise environmentally responsible consumption. Because we only review ethical issues as the price cartels. (2) Our research approach, specifically our selection of variables, do not consider the variables that Song and Kim (Citation2018) propose, that refers to the inclusion of variables like gratitude, compassion, transcendence, gender, generation, and ethnic origin, in the research field of the socially responsible consumption. (3) We do not consider Agrawal and Gupta (Citation2018) recommendation of cross-national studies because our research context only includes Colombia. (4) Our findings do not have particular implications for the public policy-makers, as Prendergast and Tsang (Citation2019) suggested. Furthermore, (5) we do not classify our sample according to sustainability issues, as many authors recommend (Koszewska, Citation2013; Maciejewski et al., Citation2019; Sarti et al., Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2019).

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The moral outrage due to corporate social irresponsibility, understanding as a (a) perception of a company’s behaviour, (b) negative word-of-mouth, and (c) moral outrage or anger, affect in order of importance the consumer’s perceived values. Specifically, those values related to (i) consumer loyalty, and (ii) consumer social and economic cost, because we do not have information about the value “tranquillity”. We discover it in the corporate social irresponsibility context of a price cartel in Colombia, South America. This cartel operated for more than 14 years and involved the five biggest Colombian companies, devoted to toilet paper, napkins, diapers, sanitary napkins, and handkerchiefs production.

Once we conducted our literature review, we propose the “responsible consumption” review from three theoretical perspective lenses. That includes (1) the consumer -e.g., customers, users and buyers- with his intrinsic and extrinsic influences or motives, (2) the control mechanisms, self-appointed or mandatory, and (3) the technical cycle for products and services that relates with the whole products and services life cycle. We also note that the first approach, related to the consumer, has most of the studies, while the second and third lenses have minor development.

In this theoretical context composed of three lenses, we decided to assume an eclectic perspective that combines them. Specifically, we mixed the first lens related to the consumer -e.g., customers, users, and buyers- with his intrinsic and extrinsic influences or motives, and the second lens that refers to the control mechanisms, self-appointed or mandatory. With this purpose, we review from the first lens, the consumer’s perceived values, in a specific context of corporate social irresponsibility, where five companies violated Colombia’s pricing laws, mandatory control mechanisms. We conduct this empirical verification, among 1.112 Consumers, specifically users, of a Colombian price cartel’s.

For future studies, we call researchers to review other corporate social irresponsibility issues that include ethical aspects—i.e., like the price-and other legal—i.e., consumer rights- social and environmental matters. We also call them to consider other kinds of products, different from mass consumption goods that we review. Furthermore, it would be necessary, to consider cross-national studies, that allows the comparison between cultures, economies, and sectors. Finally, we suggest the future inclusion of the second and third lenses—i.e. (2) The control mechanisms, self-appointed or mandatory, and (3) the technical cycle for products and services related to the whole products and services life cycle- in the responsible consumption studies.

Our findings have practical implications for marketing practitioners that need to predict the effects of corporate social irresponsibility issues on consumer loyalty and social and economic cost. Moreover, public policy-makers can also consider our results, taking into account, for example, the public disclosure of companies’ actions, during the design of control mechanisms. Our findings can also be reviewed by companies’ shareholders and CEOs who want to enter price cartels and do not imagine its effects on the consumers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Manuela Escobar-Sierra

Manuela Escobar-Sierra is a researcher and professor of the PhD in administration at the University of Medellin. She has broad experience in the Colombian productive sector and is interested in researching organisational issues within the framework of corporate social responsibility.

Alejandra García-Cardona is a researcher and professor of the Accounting program at the University of Medellin. She has extensive experience in the research of sustainable issues from organisational lenses.

Luz Dinora Vera Acevedo is a researcher and professor of the Organisational area at the National University of Colombia. She has broad experience in social research related to environment and fair trade.

References

- Afzal, F., Yunfei, S., Sajid, M., & Afzal, F. (2019). Market sustainability: A globalisation and consumer culture perspective in the Chinese retail market. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(3), 6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030575

- Agrawal, R., & Gupta, S. (2018). Consuming responsibly: Exploring environmentally responsible consumption behaviors. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(4), 231–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2017.1415402

- Alshurideh, M., Al Kurdi, B., Abu Hussien, A., & Alshaar, H. (2017). Determining the main factors affecting consumers’ acceptance of ethical advertising: A review of the Jordanian market. Journal of Marketing Communications, 23(5), 513–532. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2017.1322126

- Antonetti, P., & Maklan, S. (2016). An extended model of moral outrage at corporate social irresponsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2487-y

- Balderjahn, I., Buerke, A., Kirchgeorg, M., Peyer, M., Seegebarth, B., & Wiedmann, K.-P. (2013). Consciousness for sustainable consumption: Scale development and new insights in the economic dimension of consumers’ sustainability. AMS Review, 3(4), 181–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-013-0057-6

- Bryła, P. (2019). Regional ethnocentrism on the food market as a pattern of sustainable consumption. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(22), 19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226408

- Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (2001). Quantitative data analysis with spss release 10 for windows, a guide for social scientists. Quantitative data analysis with spss release 10 for windows (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (Second ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203726532

- Carfagna, L. B., Dubois, E. A., Fitzmaurice, C., Ouimette, M. Y., Schor, J. B., Willis, M., & Laidley, T. (2014). An emerging eco-habitus: The reconfiguration of high cultural capital practices among ethical consumers. Journal of Consumer Culture, 14(2), 158–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540514526227

- Carrigan, M., & Attalla, A. (2001, December 1). The myth of the ethical consumer – Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(7), 560–578. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760110410263

- Caruana, R., & Chatzidakis, A. (2014). Consumer social responsibility (CnSR): Toward a multi-level, multi-agent conceptualisation of the “other CSR”. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(4), 577–592. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1739-6

- Coates, K., & Middelschulte, D. (2019). Getting consumer welfare right : The competition law implications of market-driven sustainability initiatives. European Competition Journal, 15(2–3), 318–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17441056.2019.1665940

- Cohen, B., & Muñoz, P. (2017). Entering conscious consumer markets: Toward a new generation of sustainability strategies. California Management Review, 59(4), 23–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125617722792

- Cortina, A. (2009). Ética de la empresa. Revista Portuguesa De Filosofía, 65(1/4), 113–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41220792

- Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.132

- Del Giudice, T., Stranieri, S., Caracciolo, F., Ricci, E. C., Cembalo, L., Banterle, A., & Cicia, G. (2018). Corporate Social Responsibility certifications influence consumer preferences and seafood market price. Journal of Cleaner Production, 178, 526–533. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.276

- Doni, N., & Ricchiuti, G. (2013). Market equilibrium in the presence of green consumers and responsible firms: A comparative statics analysis. Resource and Energy Economics, 35(3), 380–395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2013.04.003

- Fisk, G. (1973). Criteria for a theory of responsible consumption. Journal of Marketing, 37(2), 24–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224297303700206

- García-Madariaga, J., & Rodríguez-Rivera, F. (2017). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, corporate reputation, and firms’ market value: Evidence from the automobile industry. Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC, 21(S1), 39–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjme.2017.05.003

- Gatersleben, B., Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2002). Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Environment and Behavior, 34(3), 335–362. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502034003004

- Golob, U., Podnar, K., Koklič, M. K., & Zabkar, V. (2019). The importance of corporate social responsibility for responsible consumption: Exploring moral motivations of consumers. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), 416–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1693

- Gupta, S., & Agrawal, R. (2018). Environmentally responsible consumption: Construct definition, scale development, and validation. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(4), 523–536. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1476

- Harrison, R., Newholm, T., & Shaw, D. (Eds.). (2005). The ethical consumer. Sage.

- Hassan, S. H., Maghsoudi, A., & Nasir, N. I. M. (2016). A conceptual model of perceived value and consumer satisfaction: A survey of Muslim travellers’ loyalty on Umrah tour packages. International Journal of Islamic Marketing and Branding, 1(3), 215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIMB.2016.075851

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Howard, M. C. (2016). A review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices: What we are doing and how can we improve? International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 32(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2015.1087664

- Kamboj, S., & Rahman, Z. (2017). Market orientation, marketing capabilities and sustainable innovation: The mediating role of sustainable consumption and competitive advantage. Management Research Review, 40(6), 698–724. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-09-2014-0225

- Kim, S. Y., Yeo, J., Sohn, S. H., Rha, J. Y., Choi, S., Choi, A. Y., & Shin, S. (2012). Toward a composite measure of green consumption: An exploratory study using a Korean sample. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9318-z

- Koszewska, M. (2013). A typology of polish consumers and their behaviours in the market for sustainable textiles and clothing. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(5), 507–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12031

- Koszewska, M. (2016). Understanding consumer behavior in the sustainable clothing market: Model development and verification. In Muthu S. and Gardetti M. (eds.). Environmental footprints and eco-design of products and processes (pp. 43–94). Springer.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0111-6_3

- Lazenbatt, A., Thompson-Cree, M. E. E. M., & McMurray, F. (2005). The use of exploratory factor analysis in evaluating midwives’ attitudes and stereotypical myths related to the identification and management of domestic violence in practice. Midwifery, 21(4), 322–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2005.02.006

- Maciejewski, G., Mokrysz, S., & Wróblewski, Ł. (2019). Segmentation of coffee consumers using sustainable values: Cluster analysis on the Polish coffee market. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(3), 20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030613

- McDonough, W., & Braungart, M. (2005). De la cuna a la cuna: Rehaciendo la forma en que hacemos las cosas (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Mkhize, N., & Ellis, D. (2018). Consumer cooperation in sustainability: The green gap in an emerging market. In Promoting global environmental sustainability and cooperation (pp. 112–135). Sofia Idris: IGI Global. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-3990-2.ch005

- Mohr, L. A., Webb, D. J., & Harris, K. E. (2001). Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 45–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2001.tb00102.x

- Montiel, I. (2008, September). Corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability: Separate pasts, common futures. Organisation and Environment, 21(3), 245–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026608321329

- Muncy, J. A., & Vitell, S. J. (1992). Consumer ethics: An investigation of the ethical beliefs of the final consumer. Journal of Business Research, 24(4), 297–311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(92)90036-B

- Polimeni, J. M., Iorgulescu, R. I., & Mihnea, A. (2018). Understanding consumer motivations for buying sustainable agricultural products at Romanian farmers markets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 184, 586–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.241

- Prendergast, G. P., & Tsang, A. S. L. (2019). Explaining socially responsible consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(1), 146–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2018-2568

- Roberts, J. A. (1995). Profiling levels of socially responsible consumer behavior: A cluster analytic approach and its implications for marketing. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 3(4), 97–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.1995.11501709

- Sangvikar, B., Pawar, A., Kolte, A., Mainkar, A., & Sawant, P. (2019). How does green marketing influence consumers? The market trend examination towards environmentally sustainable products in emerging Indian Cities. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering, 8(3Special Issue), 561–571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.C1114.1083S19

- Sarti, S., Darnall, N., & Testa, F. (2018). Market segmentation of consumers based on their actual sustainability and health-related purchases. Journal of Cleaner Production, 192, 270–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.188

- Schlaile, M. P., Klein, K., & Böck, W. (2018). From bounded morality to consumer social responsibility: A transdisciplinary approach to socially responsible consumption and its obstacles. Journal of Business Ethics, 149(3), 561–588. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3096-8

- Schlosser, R. W., Wendt, O., Bhavnani, S., & Nail-Chiwetalu, B. (2006). Use of information-seeking strategies for developing systematic reviews and engaging in evidence-based practice: The application of traditional and comprehensive Pearl Growing. A review. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 41(5), 567–582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820600742190

- Schmitt, T. A., & Sass, D. A. (2011). Rotation criteria and hypothesis testing for exploratory factor analysis: Implications for factor pattern loadings and interfactor correlations. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 71(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164410387348

- Semana. (2014, November). El cartel del papel higiénico que da verguenza. Publicaciones Semana S.A. Denuncia, 29. https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/el-cartel-del-papel-higienico-que-da-verguenza/410587-3

- Solomon, M. R. (2013). Comportamiento del consumidor (G. Domínguez Chávez,Ed., 10th ed). Pearson.

- Song, S. Y., & Kim, Y. K. (2018). Theory of virtue ethics: Do consumers’ good traits predict their socially responsible consumption? Journal of Business Ethics, 152(4), 1159–1175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3331-3

- Stone, G., Barnes, J. H., & Montgomery, C. (1995). Ecoscale: A scale for the measurement of environmentally responsible consumers. Psychology & Marketing, 12(7), 595–612. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220120704

- Su, C. H., Tsai, C. H., Chen, M. H., & Lv, W. Q. (2019). U.S. sustainable food market generation Z consumer segments. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(13), 14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133607

- Sudbury-Riley, L., & Kohlbacher, F. (2016). Ethically minded consumer behavior: Scale review, development, and validation. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2697–2710. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.11.005

- Tjiptono, F. (2018). Examining the challenges of responsible consumption in an emerging market. In A. Thatcher & P. H. P. Yeow (eds.). Ergonomics and human factors for a sustainable future: Current research and future possibilities (pp. 299–327). Springer Singapore.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8072-2_12

- Tseng, M. L., Tan, K. H., Geng, Y., & Govindan, K. (2016). Sustainable consumption and production in emerging markets. International Journal of Production Economics, 181, 257–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.09.016

- Venkatesan, M. (2016). Relationships between consumption and sustainability: Assessing the effect of life cycle costs on market price. In (L.B. Byrne. eds.) Learner-centered teaching activities for environmental and sustainability studies (pp. 173–180). Springer International Publishing.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28543-6_22

- Vitell, S. J. (2015). A case for consumer social responsibility (CnSR): Including a selected review of consumer ethics/social responsibility research. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(4), 767–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2110-2

- Wang, Y., Ahmed, S. C., Deng, S., & Wang, H. (2019). Success of social media marketing efforts in retaining sustainable online consumers: An empirical analysis on the online fashion retail market. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(13), 26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133596

- Webb, D. J., Mohr, L. A., & Harris, K. E. (2008). A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. Journal of Business Research, 61(2), 91–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.05.007

- Webster, Jr., F. E. J. (1975). Determining the characteristics of the socially conscious consumer. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(3), 188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/208631

- Wróblewski, Ł., & Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z. (2018). Sustainable consumer behaviour in the market of cultural services in Central European Countries: The example of Poland. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(11), 11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113856

- Yamoah, F. A., & Acquaye, A. (2019). Unravelling the attitude-behaviour gap paradox for sustainable food consumption: Insight from the UK apple market. Journal of Cleaner Production, 217, 172–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.094

- Zorell, C. V. (2020). Reconfiguring responsibilities between state and market: how the ‘concept of the state’ affects political consumerism. Acta Politica, 55, 560–586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-019-00131–w