Abstract

Previous research rarely examined the antecedents of employee well-being with the interactive effect of abusive supervision and mediating impact of psychological contract breach especially in the developing country context. Drawing upon the social exchange theory, this study attempts to bridge a research gap by investigating work engagement, work–life balance, and turnover intention with employee well-being directly and through the moderating and mediation effects of abusive supervision and psychological contract breach. To validate these relationships, 208 employees who are working in banks of Pakistan were investigated, through a survey-based questionnaire. The Smart PLS 3.0 was employed to measure the association and test the hypotheses in which structural equation modelling played a role in checking the relationships among variables. The results demonstrate that work engagement, work–life balance, and turnover intention directly affect employee well-being. This study also found that psychological contract breach has a partial mediation effect between work engagement, work–life balance, turnover intention, and abusive supervision with employee well-being. Additionally, this study shows that abusive supervision has a moderating impact between psychological contract breach and employee well-being. This study contributes to the literature and body of knowledge in human resource management and organizational behaviour. This study helps to better understanding employee well-being at micro-level in a service sector especially in developing country context (Pakistan). Finally, this study helps managers to express their feedback, suggestions, and interaction with employees.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Talent retention and well-being in the workplace are still unexplored areas of research for both academicians and practitioners. This research attempts to showcase the key elements of the subordinate's psychological behaviour that influence their decision to leave the company, as well as their health issues. To ensure an efficient relationship between employees and employers, it is critical to consider the psychological contract of employees. Employee well-being in the workplace is a common occurrence, and employees should not be subjected to it. As a result, the goal of this research is to look into the three most significant factors work engagement, work-life balance, and turnover intention were used to assess employee wellbeing and abusive behaviour of supervisors in Pakistani organizations as perceived by subordinates and coworkers during their employment. The study has significant implications for managers and leaders in terms of rethinking current strategies to promote a viable culture with a healthier workplace environment for workers to improve performance.

1. Introduction

Work engagement, work–life balance and turnover intention are three important factors to assess employee well-being via mediation mechanism of psychological contract breach and moderating effect of abusive supervision have paid rare attention by previous scholars. Despite the importance of above factors in the developing country context especially power distance culture in the Pakistan. To the knowledge of the authors, no studies have examined the link between work engagement, work–life balance and turnover through mediated-moderated model of psychological contract breach and abusive supervision with employee well-being in one study. In this way, this study contributes to body of knowledge.

Companies and management worldwide have been in predicament because they overlooked the contents of their employees’ psychological contract. It is important to consider employees’ psychological contract to maintain an effective relationship among employees and employers (Asantiel, Citation2017). In recent years, the psychological contract has emerged as a widely researched concept to better understand employees’ and employers’ expectations worldwide (AL-Abrrow et al., Citation2019). Similarly, psychological contract, which has been carried out since the 1960s till date, and which is generally explained from the employee perspective in the studies conducted after the 1980s, can be defined as the perception of the employees about the fulfilment of the obligations of the employer towards them (Ahmed et al., Citation2016). In modern organizational life, the employer’s obligations arising from the employees’ employment relationship are not fulfilled. In other words, the perception that the psychological contract has been violated is a fact that severely restricts the employee’s contribution to the organization. According to Tayyab and Tariq (Citation2001), the culture is unable to motivate employees and encourage them in Pakistani society. Employer’s attitude sometimes damages the employee’s values and behaviour, and they get disconnected from their work.

In another study (Rousseau, Citation2011; Alnoor, et al., Citation2019), researchers have identified that Pakistan has a big pool of unskilled and skilled, professional, or non-professional workers and has a different mindset and expects employers accordingly. Their relationship with the employer reflects their breached psychological contract that affects their performance level. In this study, researcher (AL-Abrrow et al. Citation2019) focuses on the relationship among psychological contract breach, turnover intention, and work engagement in the banking sector of Pakistan (Malik, S. Z., & Khalid, N. Citation2016). This competitiveness and sustainability of workers, specifically in service-based organizations, attracted scholars to develop the psychological contract of employees (Hussain et al., Citation2020).

More importantly, the banking sector is facing problems in managing employees effectively in developing country context (Malik, S. Z., & Khalid, N., 2016). To achieve the organizational objectives, a skilled and performance-oriented workforce is the primary concern of each organization. Employees’ skills are the top priority of employers because they have to produce the results. A perfect job fit employee can increase work accuracy and ultimately affect organizational performance in an effective manner (Chen Guo, Citation2016). As employees’ skills and behavior go side by side, it is imperative to have a well-behaved workforce in the organization. If a person is skilled and possess positive attitude and behaviour they add value in their performance (Sharkawi et al., Citation2013). A pilot study was conducted on the four executives of four different commercial banks. They were asked to validate the problems employers face to manage their employees concerning their skills and job performance.

According to Hofstede (Citation1980), Pakistan is a high-power distance society, in contrast to western countries, where the vast majority of abusive supervision research is concentrated. If we compare Pakistan to the Western world, such as the United States and the European Union, where power distance is minimal, the results will undoubtedly show a significant difference because abusive supervision is less destructive in Pakistani organizations because people are more likely to underestimate abusive supervision and pay less attention to how they are treated (Peltokorpi, Citation2019). In terms of the mediator, our proposed model is noticeably different. The primary goal of this study is to investigate the moderating impact of abusive supervision in the context of the mediating variable Psychological contract, as well as to assess effects on employee well-being. To determine the costs borne by employees and to comprehend this concept, which still lacks research in Pakistani organizations. In Pakistan’s banking sector, the psychological contract between employee and employer is not explicit, which eventually affects employee performance. In Pakistan’s banking sector, with respect to employees’ psychological contract formation, it is evident that they are unable to meet the employer’s expectations, and ultimately, they show poor performance.

This study addresses several research gaps. Firstly, it has been suggested to explore the antecedents of employee well-being especially in service sector (Pradhan et al., Citation2019). In this way, our study responds to aforementioned call to explore antecedents of employee well-being in banking sector of Pakistan. Despite the multiple calls for research to assess the impact of psychological contract breach as a mediation and abusive supervision as a moderator (Ampofo, Citation2021; Wei & Si, Citation2013; Lv & Xu, Citation2018). For this reason, this study considered psychological contract breach and abusive supervision as an important at the workplace and they affect employee performance along with their well-being, which is crucial for accomplish business excellence in banks. Finally, to date there is lack of research on this emerging phenomenon especially in developing country context (Pakistan). Also, this study contributes to contextual gap by conducting research in Pakistan.

In this regard, the most highlighted problems by the executives related to their skills, job performance and behaviour were work ethics, unionized staff, value behaviour, integrity, flexibility, adaptability, inclusiveness, uncomfortable in working with female bosses, lacking punctuality, oral and written communication, self-confidence, patience, work–life balance and lacking in professionalism. It also involves factors such as loyalty, perception, politics, grooming, and commitment. The individuals who are referred to as generation Y or millennial may hinder the growth of each other because of a different mindset, conflicting status, lack of effort or self-insecurities. These are the reasons why employers need to establish a psychological contract and revise it with the passage of time to address the aforementioned issues, which will be the focus of this study. However, the studies exploring the issue of psychological contact breach as well as abusive supervision are generally lacking, and the context of Pakistan is particularly underexplored. Hence, the topic is quite relevant with considerable interest to carry out the present study and fulfil the prevailing research gap.

2. Theory and hypothesis

2.1. Social exchange theory

In social exchange theory, the explanatory framework helps to understand the employees’ negative perception about the different event, situation, while they interact with their bosses, in result psychological contract may breached. As per this theory, people connected and engaged with each other and were motivated to stay together as they received inducement in return from other parties (Blau, Citation1968; Gouldner, Citation1960). In case employees perceived that their employer is not reciprocating their contributions, they showed anger, disrespect, and got frustrated. Moreover, employees reinstated their performance and behavior and ultimately exhibit job dissatisfaction and lower their commitment. Few researchers Cook et al. (Citation2013) concluded that social exchanges are most essential and play their contribution to the psychological contract.

If employees or employers don’t receive anything in return, their relationship, with each other, can be affected. It is essential to create positives and heartier relations by meeting mutual expectations. As a result employees are less willing to leave the organization and increase in job satisfaction and commitment to their employment relationships. Understanding the behaviour of subordinates at work, social exchange theory sends convincing conceptual patterns (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Furthermore, according to social exchange theory, substantial imputation occurs on employee behaviour as a result of the exchange of diverse relationships, which ultimately affects the organization’s performance (Jiwen Song et al., Citation2009). As per this theory’s philosophies (Tepper et al., Citation2009), it discusses harmful behaviour or uncomfortable responses by subordinates prompted by superiors’ aggressive behaviour due to the rule of equality, which is considered one of the most essential mortars of this proposition (Gouldner, Citation1960; Harris et al., 2007).

2.1.1. The link between work engagement and psychological contract breach

According to Kahn (Citation1990)’s empirical approach, the emotional and psychological state of employees has a noticeable effect on their role performance. He quoted himself as “People can use varying forms of their self, physiologically, intellectually, and mentally, in their work roles. performance” to support his claim. The above-mentioned quote supports the idea of a relationship between the employee engagement construct and the psychological contracts (Li et al., Citation2020). These two constructs i.e. employee engagement (EE) and psychological contracts (PC) are observed because these two constructs can actually help forecast the organization’s outcome, financial stability, and employees’ behavior. The connection between the employee and the employer impacts the economical and the behavioral well-being of the organization (Karatepe et al., Citation2020). If the organization’s financial health is affected by EE, then the already demotivated employees ward off work, surrender emotionally and cognitively, work half-heartedly, and show weak role performance (Ishtiaq, M & Zeb, M., Citation2020). If the employer fails to provide what was promised to the employee when hiring, they start cheating and looking for better options. This can be quite devastating for the organization if not given much attention. The employers need to know what the basic needs of their employees are. How an employee behaves and works at his workplace is dependent on how satiated he is psychologically (Sandhya & Sulphey, Citation2020).

H1 = Work engagement is positively associated with psychological contract breach

2.1.2. The link between work–life balance and psychological contract breach

As per the conservation of resources theory, the employees take care of their values resources by causing conditions, energies, personal characteristics, and objects (Kaya, B., & Karatepe, O. M., Citation2020). This theory further states that the employees’ values resources can be lost if they are facing stress due to their workplace (Hobfoll, Citation2001). This stressful situation then gradually leads to bad outcomes and bad employee performance (Álvarez‐Pérez et al., Citation2020). The organization’s incapability in providing what was promised through psychological contract leads to its failure to make the most of the valued resources its employees possess. Then as a consequence, the employees again face negative results through an endangered job. When an employee feels that he has been cheated in the work–life balance, he starts showing traits of giving up and caring less; the traits involve showing late at work, taking longer lunch hours, and signing off as soon as possible (Coyle-Shapiro et al., Citation2019).

H2 = Work life balance is positively associated with psychological contract breach

2.1.3. The link between turnover intention and psychological contract breach

The study of Feldman and Tumley (Citation2000) claims to observe a direct relationship between the breach of psychological contract and turnover intention Chiu et al. (Citation2020). It is said that this breach results in employees’ EVLN i.e., Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect in study of Wei Feng (Citation2004) and Haque (Citation2020). Psychological Contract has been divided into Rousseau’s two types; the first one is Relational Psychological Contract, and the other being Transactional Psychological Contract. The Relational Psychological Contract is an emotional exchange between the two concerned parties i.e. employee willing to be a loyal and long-term employee and adjust ensure job security. On the other hand, Transactional Psychological Contract goes with its name; an economic exchange between the two concerned parties i.e. training of employee, overtime, appreciation, and taking extra work for remuneration in the future (Moquin et al., Citation2019). If there is a breach in either of the contracts as mentioned earlier, the employee loses emotional and economic resources; then, it becomes necessary for him to recover this loss through some other window, as put forth by the conservation of resources theory (Gordon, S., 2020). Furthermore, if this loss is huge in magnitude, it also causes the staff to portray withdrawal (Wang et al., Citation2017). This claim, however, indicates an indirect relationship between turnover intention and psychological contract.

H3 = Turnover intention is positively associated with psychological contract breach

2.1.4. The mediating effect of psychological contract breach on employee well-being

In general prior work in relation to Psychological contract breach and employee well-being had takes no consideration of the researchers and not explored in detail. The observations also agree with the results reported by Zhao et al. (Citation2007) one substantial meta-analysis on 22 studies related on breach with other constructs but none with employee well-being (Zhao et al., Citation2007). A review of study undertaken looking at well-being by Cassar and Buttigieg (Citation2015), in that study he found that psychological contract breach negatively effect on employee well-being at the workplace due to not fulfilment of the contract from their bosses.

On the other hand Zagenczyk et al. (Citation2009) noted that the detrimental effect of psychological violation of contract on perceived organizational support has been minimized by advisors, encouraging managers and mentors. Additionally, Bono et al. (Citation2007) predicted that interactions among employees and their supervisors had an influence on psychological breach of contract and employee well-being. Psychological breach of contract is seen to be effective determinant of organizational performance (Zhao et al., Citation2007)

Nevertheless, little has been published on employee well-being, and psychological contract as an integral important relationship and determinant of the most imperative individual and organization performance (Vaart et al., Citation2013; Guest et al., Citation2010).

H4. Psychological contract breach will be positively associated with employee well-being

H5. Psychological contract breach will mediate the relationship between work engagement and employee well-being

H6. Psychological contract breach will mediate the relationship between work–life balance and employee well-being

H7. Psychological contract breach will mediate the relationship between turnover intention and employee well-being

2.1.5. The moderating role of abusive supervision

The exploitation of employees by their reporting officer is abusive supervision in which they are not given the due respect and treated wrongly (Wei & Si, Citation2013) through non-physical behavior (Tepper, Citation2000). Interestingly, it is said that abusive supervision is a product of unjust attributes of the organization faced by the supervisor (Haque, Citation2020); those who are victims of organizational injustice become abusive supervisors (Mahmood et al., Citation2020). As mentioned above, this breach of psychological contracts results in stressed employees having lesser loyalty and dedication towards the organization (Wei & Si, Citation2013). It is observed that the abusive supervision is not reported much to the HR because the subordinates fear for their future in the organization if the relation between them and their supervisors gets heated up (Xu, Loi, and Lam, Citation2015). Consequently, the subordinates start reflecting this distress through their role performance such as getting demotivated not much later after joining the organization (Qian, song, & Wang, Citation2017). Similarly, Abid and Abid (Citation2017) emphasized how much sound leadership skill set by the supervisor is important for subordinates. The subordinates usually keep analyzing their reporting officer’s behavior, which results in the levels of dedication and commitment towards the organization. There have been various studies on the negative products of abusive supervision in an organization such as emotionally disturbed employees to even those who are physically affected (Aryee et al., Citation2007; Ashfort, Citation1997; Tepper, Citation2000; Tepper et al., 2007; Tepper et al., 2007; Wei & Si, Citation2013) also claim that this emotional exploitation of subordinates affects them much negatively and consequently affect the well-being of the organization as a whole. Therefore, the Transactional Psychological Contract is said to be indirectly related to the silence of subordinates, and the abusive supervision is said to debilitate this relation

H8. Abusive supervision moderates the relationship between Psychological contract breach and employee well-being

3. Method

3.1. Participants and procedure

A quantitative approach posited by Creswell and Creswell (Citation2017) has been deployed to examine the behavior and attitudes of the sample size under observation. A survey technique has been utilized because it is appropriate for obtaining quantitative data to examine the relationship between variables (Saunders et al., Citation2009).

The ten major banks participated in this study. These banks were situated in the province of Sindh, Pakistan. A survey was administered to the full-time employees currently working in public and private sector banks through soft- and hard-copy-based questionnaires. Both probability and non-probability sampling techniques were utilized for this purpose. The unit of analysis (i.e., 10 private and public sector banks) were determined using a non-probabilistic sampling approach. The criteria for adopting this approach included: ease of access to the respondents, geographical distance, cost-effectiveness, etc. (Etikan et al., Citation2016). A hard copy of the survey form was used to obtain data from the respondents. Moreover, a soft copy of the survey was administered to those respondents who were not willing to answer the questions in a physical format. A total of 400 survey forms were distributed (i.e. both hard and soft copies) among the employees in banks, and only 208 responses (52%) were returned to be useable for further analysis.

According to , the majority of respondents were male (56.6%), while 43.4% were females. As far as the respondents’ ages between 24 and 45. The 19% of the respondents were aged between 24 and 30 years old, while 26% aged between 41 and 45 years. Moreover, when taking the respondents’ qualification into consideration. On the basis of education, 37% were graduate degree holders, 19% were Master’s degree holders. With regard to their experience, it was found that 38% held 5–10 years of experience and 14% held more than 15 years of experience, and as far as job designation is concerned, 48% held Assistant Manager positions and 13% were on Managerial Level.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents (n = 208)

3.2. Measurement scale

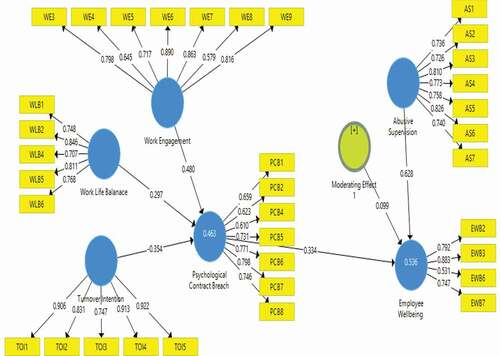

All measures used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree and 5 = Strongly Agree). The current study used measures from similar studies and the instruments for the under-observation variables (see ). Work Engagement was adopted from (Schaufeli & Salanova, Citation2011), nine items were measured (e.g “At my work, I feel bursting with energy”). Work Life Balance (WLB) was taken from Hayman (Citation2005), six items were measured (e.g “The demands of my family or spouse/ partner interfere with work-related activities”). Turnover intention was adapted from Jung and Yoon (Citation2013) to measure turnover intention. A sample item includes, “I am currently seriously considering leaving my current job to work at another company”. Psychological Contract Breach (PCB) was adopted from (Coyle-Shapiro, J., Kessler, I., Citation2000) eight items were measured (e.g “Fair pay in comparison to employees doing similar work in other organizations”). Abusive supervision was assessed using Tepper’s (Citation2000) seven item measured (e.g., “My boss reminds me of my past mistakes and failures”). Employee well-being (EWB) was assessed through 7-item scale from the multidimensional scale adopted through review of literature (Zheng et al. (Citation2015).

Table 2. Items and construct validity and reliability

4. Results

4.1. Power analysis

The current study calculated the sample size by executing a priori power assessment employing G*Power 3.1.9.4 software. The findings demonstrate that a minimum of 98 observations were intended to achieve an 80% statistical power medium effect (0.15) at a 5% (0.05) significance level for the model. This study used (n = 208), which is greater than the minimum sample size and is equivalent to other common rules of thumb (Barclay et al., Citation1995; Hair et al., Citation2010; Kline, Citation2005; Roscoe, Citation1975).

4.2. Common method bias

There was a high probability of common method bias because all the data collected was from a single source, i.e. survey forms. (Podsakof et al., Citation2003). Therefore, the current study used various procedural and statistical techniques to mitigate common method bias. For example, a clear set of instructions has been provided were provided to respondents and efforts were made to preserve confidentiality and anonymity (Reio, Citation2010). In addition, this study also used a single-factor Harman technique to check any common method bias. The exploratory factor analysis implemented to all six latent constructs. The outcomes of a single factor are nearly 21.45%. There is no single factor that accounted for more than 40% of the variance, and it has been recommended that common method bias is not an issue in this study.

5. Data analysis

A PLS-SEM technique is an advanced statistical procedure utilized in the domain in HRM and social sciences (Ringle et al., Citation2018). There were two reasons behind the use of this technique. Firstly, to provide facilitation for the prediction of dependent variables and secondly, due to the incremental nature of the current study (i.e. the mediating role of psychological contract breach between work engagement, work–life balance, turnover intention, and employee well-being) (Nitzl et al., Citation2016; Richter et al., Citation2016). The inner and outer models were examined using SmartPLS 3.0 software (Ringle et al., Citation2015). The PLS-SEM analysis was carried out over two phases. The measurement models were examined in various dimensions during the first phase. It included internal consistency, reliability, convergence (CV) and discriminant validity. The second phase was focused on the structural model i.e. R2, f2, and Q2). shows that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values are less than3, indicating that collinearity is not an issue in this study.

5.1. Internal consistency reliability

Internal consistency is evidence of the extent to which the items reflect latent variables.

Internal consistency reliability can be measured using the CR value. A CR value of more than 0.70 is generally considered to be acceptable. The results show that all the under-observance constructs reveal an acceptable/satisfactory value of CR, i.e. work engagement (0.907), work–life balance (0.884), turnover intention (0.937), psychological breach of contract (0.875), abusive supervision (0.909), and employee well-being. As a result, all items project a higher level of internal consistency.

5.2. Convergent validity

Convergent Validity (CV) is the degree to which a measure is positively correlated with an alternative measure belonging to the same construct (Hair et al., Citation2014). CV can be measured by analyzing the indicators’ outer loading and their average variance extracted (AVE) (Hair et al., Citation2017). A higher outer loading suggests that the indicator truly represents the construct. A rule of thumb suggests that the outer indicator loading should be more than 0.708, as the number squared equals 50% AVE (0.50). However, indicators having a lesser loading can be considered only if other indicators have an AVE of 0.50 or more (Hair et al., Citation2017). The results point out that all indicators except WE1, WE2, WLB3, PCB3, EWB1, EWB4, and EWB5 had acceptable loadings, and therefore, the aforementioned indicators were discarded. Moreover, the outer loadings of WE4 (0.645), WE8 (0.579), PCB1 (0.659), PCB2 (0.623), PCB4 (0.610), and EWB6 (0.531) fell below the satisfactory benchmark of 0.708 but were not discarded because the other indicators of these constructs exhibited higher loadings (i.e. greater than 0.70 and an AVE of greater than 0.50). As depicted in , the AVE scores for work engagement (0.586), work–life balance (0.605), turnover intention (0.750), psychological contract breach (0.502), abusive supervision 90.590), and employee well-being (0.562) reaffirmed the convergent validity of the measurement model.

5.3. Discriminant validity

According to Hair et al. (Citation2014), discriminant validity (DV) is the degree to which a construct is definite and exclusive from other constructs by empirical standards. The current study analyzed the DV by utilizing the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT). According to Henseler et al. (Citation2015), HTMT is the most conservative approach to measure DV compared to other techniques. It depicts the ratio of trait correlation to within trait correlations (Hair et al., Citation2017, p. 118). The HTMT value should not be more than 0.85 for the DV to be established (Clark & Watson, Citation1995; Kline, Citation2011). Other authors such as Gold et al. (Citation2001) and Teo et al. (Citation2008) put the HTMT threshold value at 0.90. depicts that each of the constructs fulfilled the HTMT 0.85 and 0.90 criterion, which indicates the presence of DV in the model.

Table 3. Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) discriminant validity

5.4. Structural model

The structural model analysis comprises the testing of the causal relationships among constructs that are under observation. This model deployed various approaches that include path coefficients, coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and the predictive relevance (Q2) (Chin, Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2017). R2 represents the predictive accuracy of the proposed model (Hair et al., Citation2014). R2 values of 0.26, 0.13, and 0.02 are large, moderate, and small (Cohen, 1998). The results indicate a large R2 value (0.463) for psychological contract breach and an R2 value of 0.536 for employee well-being (see ). The effect size (f2) is the change in R2, that occurs when a certain exogenous construct is discarded from the model to determine whether the discarded construct has a significant impact on the endogenous variable (Hair et al., Citation2014, p. 177). f2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicate small, moderate, and large effect sizes, respectively. The results show that work engagement had an f2 of 0.386 and abusive supervision had an effect size of 0.798. It means that both of these variables had a substantial effect on the psychological contract breach. The effect size of work–life balance was recorded at 0.132, which indicates that WLB had a small impact on psychological contract breach. Moreover, the effect size of turnover intention was recorded at 0.206, which indicates that it had a medium effect on psychological contract breach. The psychological contract breach had a moderate impact on employee well-being, as indicated by its effect size (f2 0.237) (see ).

Table 4. R2 and Q2 of endogenous constructs

Table 5. F2 values of the path model

The Q2 values were obtained using the blindfolding technique. According to Hair et al. (Citation2017) blindfolding is a sample reuse procedure that discards every dth data point in the indicators that are a part of the endogenous constructs. According to Fornell and Cha (1994), a Q2 value of greater than 0 depicts the predictive relevance of a model’s dependent constructs. The Q2 values for psychological contract breach and employee well-being were recorded at 0.269 and 0.212, respectively (see ). This suggests that both of these constructs depicted acceptable predictive relevance. The parameter’s statistical significance was measured using the bootstrapping approach (5000 subsamples, one-tailed significance). The results show that abusive supervision (H1, β = 0.628, t = 13.505 p = 0.000) positively moderates the interactive effect on employee well-being. Psychological contract breach (H2 β = 0.334 t = 7.533 p = 0.000) had a direct positive effect on employee well-being. H3, H4 and H5 Turnover intention (H3 β = −0.354 t = 3.966 p = 0.000), work engagement (H4 β = 0.480 t = 9.453 p = 0.000) and work–life balance (H5 β = 0.297 t = 4.675 p = 0.000) also had a direct positive effect on psychological contract breach (see ).

Table 6. Path coefficient direct and indirect relationship

The mediating impact of psychological contract breach (H6, H7, H8) in association with work engagement, work–life balance, turnover intention, and employee well-being was analyzed using mediation analysis. The indirect path analysis depicts H6 from TOI→PCB → EWB (β = −0.118, t = 3.401 P = 0.001) and path H7 from WE → PCB → EWB (β = 0.160, t = 5.807 p = 0.000), and path H8 from WLB→ PCB → EWB β = 0.099, t = 3.772 p = 0.000). Hence, it can be deduced that psychological contract breach partially mediates the association among work engagement, work–life balance, turnover intention, and employee well-being (see ).

6. Discussion

Drawing upon social exchange theory as an overarching theoretical framework, this study examined the role of work engagement, work–life balance, and turnover intention on employee well-being by mediating the role of psychological contract breach and moderating the interactive effect of abusive supervision. This study revealed that hypothesis (H1) abusive supervision has a significant and positive moderating interactive effect on employee well-being, agreeing with the study by (Lin et al., Citation2013). This implies abusive supervisors affects employees’ well-being at the workplace by reducing employee performance and increasing stress levels. Importantly, this research found that Pakistan has power distance culture in the banks, where mostly managers and supervisors negatively affect employee well-being. Also, in a recent study by Hussain et al. (Citation2020) conducted in service-based organizations in Pakistan, they found that if supervisors abuse their employees, it directly impacts on their psychological well-being. Moreover, well-being is an important to maintain health and safety of employees at workplace. Our research revealed that employees are struggling to achieve organizational performance due to negative behaviour of supervisors and managers in banks.

Hypothesis (H2) psychological contract breach has a positive impact on employee well-being. Our finding is consistent with several studies (Duran et al., Citation2019; Gracia et al., Citation2007; Parzefall and Hakanen (Citation2008) they can be understood that contract breach has negative consequences for employees and affects their well-being. The results of the study undertaken are also similar with; Guest et al. (Citation2010) that transformation in the employment association and exact kinds of employment contracts affect employee well-being. Similarly, banks do not fulfil contract obligations of employees so this breach brings negative behaviours from employees. Importantly, prior research conducted in banking sectors of Albania; they found that violation of psychological contract breach reduces employee performance and deteriorate well-being at the workplace (Manxhari, Citation2015).

Hypothesis (H3) confirms turnover intention is positively related to psychological contract breach. This finding is similar to a study conducted in the context of Pakistan by Azeem et al. (Citation2020). They found that employees experiencing psychological contract breach had an increasing intention to leave because of employer disloyalty. Additionally, our results are also consistent with numerous studies (Robinson & Rousseau, Citation1994); (Arshad, Citation2016; Estreder et al., Citation2020; Raja et al., Citation2011). Hypothesis (H4) work engagement is significantly and positively related to psychological contract breach. This finding is consistent with these recent studies (Gordon & Gordon, Citation2020; Naidoo et al., Citation2019; Soares & Mosquera, Citation2019). Hypothesis (H5) work–life balance is positively related to psychological contract breach. Our finding is similar to (Kaya & Karatepe, Citation2020). Recent research by Wong et al. (Citation2021) found that work–life balance promotes employee well-being and quality and quantity of personal life-time. This study found an indirect effect (H6), turnover intention is a partially mediated relationship between psychological contract breach and employee well-being. This finding is consistent with prior studies (Vaart et al., Citation2013; Bravo et al., Citation2019). They suggested that employers must devise employee-friendly policies to enhance workplace well-being as a retention strategy.

Hypothesis (H7) demonstrates that work engagement is a partially mediated relationship between psychological contract breach and employee well-being. This finding is similar to previous studies by (Gordon & Gordon, Citation2020; Karatepe et al., Citation2020). These findings endorse the study’s argument that work engagement plays a crucial role in the workplace by mediating psychological contract breach mechanisms. Hypothesis (H8) shows that work–life balance partially mediates between psychological contract breach and employee well-being. This finding is consistent with these studies (Haider et al., Citation2018; Kaya & Karatepe, Citation2020; Quratulain et al., Citation2018).

Hence, based on the conceptual framework of the model this study tested all the mentioned hypotheses to address the underlying research issue and achieve the objective of the study. In this regard, researchers recommend to consider the issue of common method bias, which has also been consider in the present study. Similarly, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability of the study is important requirement for robust results that has been ascertained as well. Moreover, the coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2) have also been included in the analysis adequately, as several research emphasized on the same. Hence such robust analysis provided reliable results necessary to address the theme of the present study.

6.1. Theoretical contribution

The results of the present study deliver worthy theoretical implications for the academic discourse. Firstly, this study contributes to the existing literature by exploring work engagement, work–life balance, and turnover intention on employee well-being. Secondly, this study also knows the mediating effect of psychological contract breach between work engagement, work–life balance, and turnover intention on employee well-being. Employers breach the promises made to employees, so consequently, it affects their well-being. Thirdly, this study introduces abusive supervision as a moderating role in employees’ well-being, which is not examined by prior studies. In this way, it is a novel contribution to the body of knowledge. Fourthly, this study broadens our better understanding by incorporating the social exchange theory, and assessing the mediating role of psychological contract breach from an employee’s perspective.

7. Practical implications for managers

Based on this study, we can observe two practical implications; the first one is the need for policies that entertain employees and their psychological contract with the organization, which is adverse in the case of this contact breach. The study explored that the employees go through various problems like workload, personal issues because of work, stress, and the worry of keeping up with their supervisor. Therefore, the workplace operations have a huge impact on the mental and physical health of the employees due to work dynamics and their relation with the supervisors. The second practical implication of this study is to provide a guidance to the supervisors about how they should not breach their subordinates’ psychological contract with the organization, which also emerged as a problematic aspect in the prevailing scenario of the banking sector of Pakistan. If dealt with care, the employees can be game-changers for any organization and help it achieve various objectives with less turnover rate.

7.1. Limitations and future direction

Despite several strengths, this study has few limitations, paving the way for future research to broaden the understanding of the association investigated in this study. First, this study collected data from a single source through a survey-based method. Hence, our model can be replicated by collecting longitudinal data to assess the frequent occurrence of psychological contract breach and abusive supervision causal relationship. Second. This study focused on only one sector (banking); future researchers can gather data from multi-sectors to attain broader understanding of employee well-being in different sectors due to diverse human resource policies. Third, this study was conducted in the power dominant society of developing country (Pakistan). Future researchers should investigate our model in western countries where power is less practiced at the workplace. Finally, our model can be replicated in individualistic cultural societies to understand the impact on employee well-being. Future research can also use different moderators such as (supervisory support, organization culture) and mediators (top management support and employee commitment) to develop more revelations regarding employee well-being. We also encourage applying this model to a bi-way model

8. Conclusion

This study examined the relationship among work–life balance, abusive supervision, work engagement, and turnover intention in Pakistan’s banking sector by applying the Structural Equation Model on Smart PLS. It can help policymakers in the banking sector globally and locally to come with employee-oriented policies. This research also provides an overview of employees’ aspects in a stressed workplace and how crucial their relation with the supervisors is. It is proved with this study that turnover intention; work–life balance, employee engagement, and abusive supervision impact the well-being of the employees.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Saba Gulzar

Saba Gulzar is a Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Business Management (IoBM), Pakistan. She has more than 13 years of teaching. Experience her main focus: employee wellbeing, psychological contract, employee competencies and abusive supervision. She is a reviewer for few research journals. She is also a PhD Scholar.

Nadia Ayub

Nadia Ayub is an Associate Dean at College of Economics & Social Development, Institute of Business Management (IoBM), Pakistan. She has more than 15 years teaching experience. Her area of research, includes psychometrics, organizational behavior, and positive psychology.

Zuhair Abbas

Zuhair Abbas is a Ph.D. candidate at FAME at Tomas Bata University in Zlin, Czech Republic, Europe. His main research on green human resource management, abusive supervision, psychological contract breach, employee wellbeing, and corporate sustainability.

References

- AL-Abrrow, H., Alnoor, A., Ismail, E., Eneizan, B., & Makhamreh, H. Z. (2019). Psychological contract and organizational misbehavior: Exploring the moderating and mediating effects of organizational health and psychological contract breach in Iraqi oil tanks company. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1683123.

- Abid, S., & Abid., H. (2017). Abusive supervision and turnover intention among female healthcare professionals in Pakistani hospitals. International Journal of Advanced Research, 5(11), 470–479.

- Ahmed, W., Kiyani, A., & Hashmi, S. H., (2016), The study on organizational cynicism, organizational injustice & breach of psychological contract as the determinants of deviant work behavior. actual problems of economics. Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2743141

- AL-Abrrow, H., Alnoor, A., Ismail, E., Eneizan, B., Makhamreh, H. Z., & Ratajczak-Mrozek, M. (2019). Psychological contract and organizational misbehavior: Exploring the moderating and mediating effects of organizational health and psychological contract breach in Iraqi oil tanks company. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1683123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1683123

- Álvarez-Pérez, M. D., Carballo-Penela, A., & Rivera-Torres, P. (2020). Work-life balance and corporate social responsibility: The evaluation of gender differences on the relationship between family-friendly psychological climate and altruistic behaviors at work. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(6), 2777–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2001

- Ampofo, E. T. (2021). Do job satisfaction and work engagement mediate the effects of psychological contract breach and abusive supervision on hotel employees’ life satisfaction? Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(3), 282–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1817222

- Arshad, R. (2016). Psychological contract violation and turnover intention: Do cultural values matter? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 3(1), 251–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-10-2013-0337

- Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., Sun, L. Y., & Debrah, Y. A. (2007). Antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision: Test of a trickle-down model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 191–201.

- Asantiel, K. (2017). The effects of perceived psychological contract breach on employees’ counterproductive work behaviour in Arusha City Council ( Doctoral dissertation.The Open University of Tanzania). http://repository.out.ac.tz/id/eprint/1964

- Ashfort, B. (1997). Petty tyranny in organizations: A preliminary examination of antecedents and consequences. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 14, 126–140.

- Azeem, M. U., Bajwa, S. U., Shahzad, K., & Aslam, H. (2020). Psychological contract violation and turnover intention: The role of job dissatisfaction and work disengagement. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(6), 1291–1308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2019-0372

- Babin, B. J., Griffin, M., & Hair, J. F. (2016). Heresies and sacred cows in scholarly marketing publications. 69(8), 3133–3138. Elsevier. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.001

- Barclay, D., Thompson, R., & Higgins, C. (1995). The partial least squares (Pls) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2, 285–287.

- Blau, P. M. (1968). Social exchange. International encyclopedia of the social sciences, 7, 452–457.

- Bono, J. E., Foldes, H. J., Vinson, G., & Muros, J. P. (2007). Workplace emotions: The role of supervision and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1357–1367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1357

- Bravo, G. A., Won, D., & Chiu, W. (2019). Psychological contract, job satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention: Exploring the moderating role of psychological contract breach in national collegiate athletic association coaches. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954119848420

- Cassar, V., & Buttigieg, S. C. (2015). Psychological contract breach, organizational justice and emotional well-being. Personnel Review, 44(2), 217–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2013-0061

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least Squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), modern methods for business research (pp. 295). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Chiu, W., Hui, R. T. Y., Won, D., & Bae, J. S. (2020). Leader-member exchange and turnover intention among collegiate student-athletes: The mediating role of psychological empowerment and the moderating role of psychological contract breach in competitive team sport environments. European Sport Management Quarterly, 47, 817–828 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1820548

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cook, K. S., Cheshire, C., Rice, E. R., & Nakagawa, S. (2013). Social exchange theory. In Handbook of social psychology (pp. 61–88). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Coyle‐Shapiro, J., & Kessler, I. (2000). Consequences of the psychological contract for the employment relationship: A large scale survey. Journal of management studies, 37(7), 903–930

- Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M., Pereira Costa, S., Doden, W., & Chang, C. (2019). Psychological contracts: Past, present, and future. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6(1), 145–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015212

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900. CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

- Duran, F., Woodhams, J., & Bishopp, D. (2019). An interview study of the experiences of police officers in regard to psychological contract and wellbeing. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 34(2), 184–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9275-z

- Estreder, Y., Rigotti, T., Tomas, I., & Ramos, J. (2020). Psychological contract and organizational justice: The role of normative contract. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2018-0039

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

- Gordon, S., & Gordon, S.. (2020). Organizational support versus supervisor support: The impact on hospitality managers’ psychological contract and work engagement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102374

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). “The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement.” American Sociological Review, 25: 161–178.

- Gracia, F. J., Silla, I., Peiró, J. M., & Fortes-Ferreira, L. (2007). The state of the psychological contract and its relation to employees’ psychological health. Psychology in Spain, 11, 33–41.

- Guest, D. E., Isaksson, K., & De Witte, H. (2010). Employment contracts, psychological contracts, and worker well-being: An international study. Oxford University Press.

- Guo, C. (2016). Employee attributions and psychological contract breach in china. The University of Manchester (United Kingdom).

- Haider, S., Jabeen, S., & Ahmad, J. (2018). Moderated mediation between work life balance and employee job performance: The role of psychological wellbeing and satisfaction with coworkers. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 34(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2018a4

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall: Pearson.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Haque, A. (2020). Strategic HRM and organisational performance: Does turnover intention matter? International Journal of Organizational Analysis,29(3), 656–681. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-09-2019-1877

- Hayman, J. (2005). Psychometric assessment of an instrument designed to measure work life balance. Research and Practice in Human Resource Management, 13(1), 85–91.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied psychology, 50(3), 337–421.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International studies of management & organization, 10(4), 15–41

- Hussain, K., Abbas, Z., Gulzar, S., Jibril, A. B., Hussain, A., & Foroudi, P.. (2020). Examining the impact of abusive supervision on employees’ psychological wellbeing and turnover intention: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1818998

- Ishtiaq, M., & Zeb, M. (2020). Psychological Contract and Employee Engagement; The Mediating role of Job-Stress, evidence from Pakistan. Business & Economic Review, 12(2), 83–108.

- Ishtiaq, M., & Zeb, M. (2020). Psychological contract, employee engagement, and the mediating role of job-stress: Evidence from Pakistan. Business & Economic Review, 12(2), 83–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22547/BER/12.2.4

- Jiwen Song, L., Tsui, A. S., & Law, K. S. (2009). Unpacking employee responses to organizational exchange mechanisms: The role of social and economic exchange perceptions. Journal of Management, 35(1), 56–93.

- Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2013). The effects of organizational service orientation on person–organization fit and turnover intent. The Service Industries Journal, 33(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2011.596932

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724. Google Scholar.

- Karatepe, O. M., Rezapouraghdam, H., & Hassannia, R. (2020). Does employee engagement mediate the influence of psychological contract breach on pro-environmental behaviors and intent to remain with the organization in the hotel industry? Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(3), 1–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1812142

- Kaya, B., & Karatepe, O. M. (2020). Attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of work-life balance among hotel employees: The mediating role of psychological contract breach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42, 199–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.01.003

- lKaya, B., & Karatepe, O. M. (2020). Attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of work-life balance among hotel employees: The mediating role of psychological contract breach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42(April 2019), 199–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.htm.2020.01.003

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. Guilford Press.

- Li Y, Wang Y, Jiang J, Valdimarsdottir U, et al. (2020) Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychological Medicine. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0

- Lin, W., Wang, L., & Chen, S. (2013). Abusive supervision and employee well-being: The moderating effect of power distance orientation. Applied Psychology, 62(2), 308–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00520.x

- Lv, Z., & Xu, T. (2018). Psychological contract breach, high-performance work system and engagement: The mediated effect of person-organization fit. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(7), 1257–1284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1194873

- Mahmood, F., Qadeer, F., Abbas, Z., Aman, J., Aman, J., Aman, J., Aman, J., & Aman, J. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ negative behaviors under abusive supervision: A multilevel insight. Sustainability, 12(7), 2647. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072647

- Malik, S. Z., & Khalid, N. (2016). Psychological contract breach, work engagement and turnover intention. Pakistan Economic and Social Review, 54(1), 37–54

- Manxhari, M. (2015). Employment relationships and the psychological contract: The case of banking sector in Albania. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 210, 231–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.363

- Medrano, L. A., & Trógolo, M. A. (2018). Employee well-being and life satisfaction in Argentina: The contribution of psychological detachment from work. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 34, 69–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2018a9

- Moquin, R., Riemenschneider, K., & L. Wakefield, R.. (2019). Psychological contract and turnover intention in the information technology profession. Information Systems Management, 36(2), 111–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2019.1587574

- Naidoo, V., Abarantyne, I., & Rugimbana, R. (2019). The impact of psychological contracts on employee engagement at a university of technology. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 17, 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v17i0.1039

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Carrion, G. C. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least Squares path modelling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

- Parzefall, M., & Hakanen, J. (2008). Psychological contract and its motivational and health-enhancing properties. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011013849

- Peltokorpi, V. (2019). Abusive supervision and emotional exhaustion: the moderating role of power distance orientation and the mediating role of interaction avoidance. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 57(3), 251–275.

- Podsakof, P. M., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research. MIS Quarterly, 30(1), 115–141.

- Pradhan, S., Srivastava, A., & Mishra, D. K. (2019). Abusive supervision and knowledge hiding: The mediating role of psychological contract violation and supervisor directed aggression. Journal of Knowledge Management.

- Qian, J., Song, B. & Wang, B. (2017). Abusvie Supervision and Job Dissatisfaction: The Moderating Effects of Feedback Avoidance and Critical Thinking. Frontiers in Psychology.

- Quratulain, S., Khan, A. K., Crawshaw, J. R., Arain, G. A., & Hameed, I. (2018). A study of employee affective organizational commitment and retention in Pakistan: The roles of psychological contract breach and norms of reciprocity. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(17), 2552–2579. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1254099

- Raja, U., Johns, G., & Bilgrami, S. (2011). Negative consequences of felt violations: The deeper the relationship, the stronger the reaction. Applied Psychology, 60(3), 397–420. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00441.x

- Reio, T. G. J. (2010). The threat of common method variance bias to theory building. Human Resource Development Review, 9(4), 405–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484310380331

- Richter, N. F., Sinkovics, R. R., Ringle, C. M., Schlagel, C., Sinkovics, R., Ruey-Jer, B. J., & Daekwan Kim, R. (2016). A critical look at the use of SEM in international business research. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 376–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-04-2014-0148

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2018). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617–1643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1416655

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015), Boenningstedt, S. GmbH, available at: http://www.smartpls.com(accessed October 20, 2020)

- Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(3), 245–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030150306

- Roscoe, J. T. (1975). Fundamental research statistics for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Holt Rinehart and Winston.

- Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Sage Publications.

- Rousseau, D. M. (2011). The individual–organization relationship: The psychological contract. In APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol 3: Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization. (pp. 191–220). American Psychological Association.

- Rousseau, D. M., & McLean Parks, J. (1993). The contracts of individuals and organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 15, 1–43.

- Sandhya, S., & Sulphey, M. M. (2020). Influence of empowerment, psychological contract and employee engagement on voluntary turnover intentions. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-04-2019-0189

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. Pearson education.

- Schaufeli, W., & Salanova, M. (2011). Work engagement: On how to better catch a slippery concept. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2010.515981

- Sharkawi, S., Rahim, A. R. A., & AzuraDahalan, N. (2013). Relationship between person organization fit, psychological contract violation on counterproductive work behaviour. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(4).

- Soares, M. E., & Mosquera, P. (2019). Fostering work engagement: The role of the psychological contract. Journal of Business Research, 101, 469–476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.003

- Tayyab, S., & Tariq, N. (2001). WORK VALVES AND ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT IN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTOR EXECUTIVES. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 95–112.

- Teo, T. S. H., Srivastava, S. C., & Jiang, J. Y. (2008). Trust and electronic government success: An empirical study. Journal of Management Information Systems, 25(3), 99–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222250303

- Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/1556375

- Tepper, B. J., Carr, J. C., Breaux, D. M., Geider, S., Hu, C., & Hua, W. (2009). Abusive supervision, intentions to quit, and employees’ workplace deviance: A power/dependence analysis. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 109(2), 156–167.

- Turnley W H., Feldman D C. (2000). A Discrepancy Model of Psychological Contract Violations. Human Resource Management Review, No.9, pp 367–386.

- Van der Vaart, L., Linde, B., & Cockeran, M. (2013). The state of the psychological contract and employees' intention to leave: The mediating role of employee well-being. South African Journal of Psychology, 43(3), 356–369.

- Wang, W., Fu, Y., Qiu, H., Moore, J. H., & Wang, Z. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: A moderated mediation model of organizational identification and moral identity. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1906.

- Wei Feng. (2004). Study on Organization- Manager Psychological Contract Violation. Doctoral dissertation in Fudan University.

- Wei, F., & Si, S. (2013). Psychological contract breach, negative reciprocity, and abusive supervision: The mediated effect of organizational identification. Management and Organization Review, 9(3), 541–561.

- Wong, K. P., Lee, F. C. H., Teh, P.-L., & Chan, A. H. S. (2021). The interplay of socioecological determinants of work–life balance, subjective wellbeing and employee wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4525. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094525

- Xu, A. J., Loi, R., & Lam, L. W. (2015). The bad boss takes it all: How abusive supervision and leader–member exchange interact to influence employee silence. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(5), 763–774.

- Zagenczyk, T. J., Gibney, R., Kiewitz, C., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2009). “Mentors, supervisors, and role models: Do they reduce the effects of psychological contract breach? Human Resource Management Journal, 19(3), 237–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2009.00097.x

- Zhao, H., Wayne, S. J., Glibkowski, B. C., & Bravo, J. (2007). “The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: A meta analysis. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 647–680. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00087.x

- Zheng, X., Zhu, W., Zhao, H., & Zhang, C. (2015). Employee well being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(5), 621–644. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1990