Abstract

This study aimed to examine how employees’ perceived benefits of training impact their level of affective organizational commitment through investigating the mediating role of individual readiness for change in National Jordanian banks. The study sample included 451 employees from 16 banks in Jordan. Stratified random sampling was used for the selection of the study participants, and data were collected using a self-administered written questionnaire. Partial least squares structural equation modelling was conducted to analyze the collected data and test the study hypotheses, which were developed according to the social exchange theory and psychological contract theory. The analysis provided strong evidence for the contentions of the social exchange theory, whereby employees’ affective commitment to their banks was found to be positively influenced by their perceptions of the job-, career, and personal-related benefits of training. Moreover, individual readiness for change was shown to be positively influenced by employees’ perceived benefits of training, and employees’ affective organizational commitment was positively influenced by their readiness for change. Finally, individual readiness for change was found to act as a mediating variable between employees’ perceived benefits of training and their level of affective commitment to their banks. The current study provides bank management teams with a comprehensive understanding of employees’ affective organizational commitment as a potential outcome of training and provides evidence for the relationship between the two variables.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Each Jordanian bank spends a significant amount of money on employee training each year, and this investment can be justified by improved bank performance, which results from trained employees applying what they have learned in training courses at their workplaces, and which will eventually be reflected in overall bank effectiveness. The benefits of employee training extend beyond solving work-related problems and upgrading employees’ skills and knowledge; training also assists banks in successfully driving change initiatives and implementing innovative solutions because training provides employees with self-confidence as well as the necessary knowledge and skills to perform their duties under transitions. This in turn may increase employees’ affective commitment to their banks because employees will identify their own benefits as well as the benefits that their banks might gain from their participation in training programs.

1. Introduction

The contemporary business environment, shaped by rapid technological advancements, globalization, and competing value multiplicity, has created an urgent need for organizations to adopt innovative practices to survive the subsequent impacts of an increasingly competitive environment. Therefore, organizations have been reconstructing their tactics to be aligned with the increasing demands of the business environment (Ocen et al., Citation2017; Potnuru & Sahoo, Citation2016).

To ensure organizational survival, employees should promptly and effectively acclimatize to the organizational changes arising from the growing business environment. In this regard, training can be considered as a systematic approach that can be implemented by organizations to improve organizational effectiveness by providing and improving employees’ knowledge, skills, and abilities (Aguinis & Kraiger, Citation2009; García, 2005; Ng & Dastmalchian, Citation2011; Potnuru & Sahoo, Citation2016; Aragón-Sánchez et al., Citation2003; Van de Wiele, Citation2010). In contemporary organizations, training has become an integral part of strategic planning (Ballesteros-Rodríguez et al., Citation2012; Kucherov & Manokhina, Citation2017; Lin & Jacobs, Citation2008, Narayan et al., Citation2007).

Training is a human resource management practice (Fontinha et al., Citation2014; Jiang et al., Citation2012) which plays an important role in organizations achieving competitive advantage. Not only does training enhance employees’ organizational commitment and satisfaction, but it also improves employees’ self-confidence, behaviors, work-related attitudes, creative thinking, and interaction with each other (Aguinis & Kraiger, Citation2009; Burden & Proctor, Citation2000; M. Shammot, Citation2014; Marin-Diaz et al., Citation2014; Muñoz Castellanos and Salinero Martín, 2011). Training provided by organizations can be perceived as an investment in human capital, as providing employees with knowledge, skills, and abilities may lead to positive outcomes for the organization. Furthermore, as employees implement the skills and competencies gained from training, this can improve their performance in their assigned duties and thus lead to improved organizational performance and productivity (García, 2005; Ng & Dastmalchian, Citation2011; Potnuru & Sahoo, Citation2016; Van de Wiele, Citation2010).

In addition, training provides employees with a significant amount of data which can then be transformed into information. This information eventually becomes knowledge, which promotes the intellectual capital of an organization and ultimately allows organizations to maintain their competitive advantage. Therefore, training is important for improving organizations’ intellectual capital, especially organizations characterized by constantly dynamic work conditions and frequent change initiatives. From a strategic point of view, training has been employed by organizations as a mechanism to impede human capital knowledge obsolescence (Koster et al., Citation2011; Muñoz Castellanos and Salinero Martín, 2011; Vidal-Salazar et al., Citation2012).

However, training may pave the way for feelings of employability development among employees, which may be reflected in the increase in their job opportunities and alternatives (Benson, Citation2006; J. J. Lee et al., Citation2014). Accordingly, investment in training may make employees more marketable and increase their employability, therefore increasing organizations’ chances of losing skilled employees. In turn, low level of employee commitment and high employee turnover exposes the employer to human capital investment risk (Koster et al., Citation2011; Ling et al., Citation2014). In this vein, organizations usually incur significant expenses to invest in their employees by providing them with training programs (Kucherov & Manokhina, Citation2017; Lauzier & Mercier, Citation2018; Steele-Johnson et al., Citation2010). However, in cases where the benefits gained from training programs are not met with an increased level of affective organizational commitment (AOC) among employees, there is no guarantee that training will be of any benefit for the organization, especially if the employee decides to leave the organization after completing the training program (Abd Rahman et al., Citation2013; Dirani, 2012).

Therefore, organizations are more inclined towards adopting training programs that enable them to track and assess the conformity of training program outcomes with their objectives and the effectiveness of such programs (Ghosh et al., Citation2012). In this respect, designing and implementing a training program is a critical matter, as previous studies have indicated that training programs should be tailored to enhance employees’ commitment to their organizations (Dhar, Citation2015; Sahinidis & Bouris, Citation2008).

In providing training, organizations should attempt to ensure that their employees have positive perceptions towards training programs. This can be achieved through ensuring the availability of these programs; providing social support for training from all organizational members, especially supervisors; motivating employees to learn from these programs; and explaining the potential benefits that can be gained from participation in these programs (Ahmad & Bakar, Citation2003; Almodarresi & Hajmalek, Citation2015; Ashar et al., Citation2013; Bartlett & Kang, Citation2004; Bashir & Long, Citation2015; Bulut & Culha, Citation2010; Dhar, Citation2015; Newman et al., Citation2011; Silva & Dias, Citation2016). It has been empirically evidenced that employees’ work-related attitudes, including their organizational commitment, are associated with their perceptions of the human resource management practices (e.g., training) adopted by their organizations. Thus, employees’ commitment to their organizations may be managed by such practices (Meyer & Allen, Citation1997).

Previous literature suggests that the competencies, skills, abilities, and knowledge that can be acquired by employees’ participation in different training programs are considered fundamental elements in generating profit and maintaining competitive advantage. This may be particularly observed in financial institutions such as banks, where there is clear interaction between employees and customers. Accordingly, employees’ work-related attitudes (e.g., AOC) in such organizations are considered to be of the main factors contributing to the success of these organizations (Choi & Yoon, Citation2015; Díaz-Fernández et al., Citation2014; Vidal-Salazar et al., Citation2012).

The banking sector is faced with constant changes and technological advancements, in addition to different types of customers with various demands and needs. These changes may be the result of new legislations, forceful competition, technological advancements, or staffing-related issues. To survive and succeed in a continuously changing business environment, it is essential that banks provide their employees with training opportunities that enable them to perform their required duties under the new changes at the right and acceptable level (Chang et al., Citation2016; Raineri, Citation2011; Sackmann et al., Citation2009).

Participation in training courses may have personal-, career-, and job-related benefits for employees, which may increase their readiness and ability to embrace technological advancements and adopt new methods for production. These benefits may also promote employees’ creativity and innovation, increase their level of affective commitment, and hence decrease their intentions of leaving their organizations (Hassan & Mahmood, Citation2016; Muma et al., Citation2014). In this respect, Kennett (Citation2013) argued that the aim of training is to encourage organizational culture to adopt and execute change initiatives during the business cycle.

Change efforts in organizations have often failed to meet the expected outcomes. One of the major reasons behind the unsuccessful implementation of organizational change initiatives is related to the negative attitudes of employees towards these initiatives. Thus, employees should be well-prepared, motivated, and psychologically ready to accept changes. Otherwise, executing change initiatives without considering the attitudes of employees towards these changes may reduce employees’ commitment to their organizations (Cinite et al., Citation2009; Elias, Citation2009; Jones et al., Citation2005; Lyons et al., Citation2009; Weiner et al., Citation2008).

Employees’ readiness for change is considered an antecedent to positive work-related attitudes, including organizational commitment (Elias, Citation2009; Rafferty et al., Citation2013). Employees usually show positive attitudes towards change initiatives when they have a high level of AOC. In this regard, employees’ readiness for doing their best for the sake of the organization will significantly contribute to the successful implementation of change initiatives (Vakola & Nikolaou, Citation2005).

The resistance of individuals to change usually arises from imagined uncertainty, fear of working under new arrangements, and fear of possible incapability to carry out tasks under such changes. Organizations must first convey the message of change to their employees to pave the way for change initiatives and later must make all necessary attempts to minimize their employees’ fears of change. To achieve this, strategies such as human resource management practices, particularly training, are required (Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999; Fletcher et al., Citation2018; Rafferty et al., Citation2013).

Few studies have explored employees’ perceptions towards human resource management practices, such as training, and the outcomes of such practices, such as increased AOC among employees (Ahmad & Bakar, Citation2003; Newman et al., Citation2011). Further, the majority of studies on training have focused on tangible returns, such as performance, productivity, and service quality (Apospori et al., Citation2008; Aragón-Sánchez et al., Citation2003; Collier et al., Citation2011; García, 2005; Muñoz Castellanos and Salinero Martín, 2011; Tharenou et al., Citation2007; Ubeda-García et al., 2013). It is worth mentioning that training outcomes such as AOC and job satisfaction have been shown to play a mediating role between training and overall organizational effectiveness (Kehoe & Wright, Citation2013; Tharenou et al., Citation2007).

The impact of employees’ perceived benefits of training on their level of AOC has not been extensively investigated, and further investigation has been recommended by various studies (Ahmad & Bakar, Citation2003; Newman et al., Citation2011). Even though the aforementioned impact was tested in various contexts among healthcare sector employees in the United States (US) (Bartlett, Citation2001) and the US and New Zealand (Bartlett & Kang, Citation2004), hotel sector employees in Turkey (Bulut & Culha, Citation2010), academic staff at a public university in Malaysia (Bashir & Long, Citation2015), and employees of multinational enterprises in China (Newman et al., Citation2011). However, very few studies have examined the relationship between employees’ perceived benefits of training and their levels of AOC in the Arab world, especially in Jordan.

Both training and employees’ AOC have been investigated by researchers, but little is known about the relationship between the two variables. Specifically, little is known about the relationship between employees’ perceived benefits of training as a multi-dimensional construct comprising career-, job-, and personal-related benefits on one hand and employees’ AOC on the other (Newman et al., Citation2011; Yang et al., Citation2012). In addition, it has been recommended that further research is conducted to investigate the extent to which adopted change initiatives influence employees’ AOC and whether these changes strengthen or weaken AOC among employees (Madsen et al., Citation2005).

The current study aimed to investigate the potential impacts of employees’ personal-, career, and job-related perceived benefits of training on their levels of AOC. Whilst AOC has been extensively explored by studies in the field of organizational behavior, further research is needed to investigate how employees’ AOC can be enhanced by their perceptions of the benefits of training (Ahmad & Bakar, Citation2003; Newman et al., Citation2011; Shuck et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, though various aspects of change management have been researched, no conclusions have been reached regarding the inter-relationships between employees’ perceived benefits of training (EPT), individual readiness for change (IRFC), and employees’ level of affective organizational commitment (AOC). Accordingly, the current study contributes to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the relationship between perceived benefits of training and level of AOC among employees of national banks in Jordan. This study also investigated the mediating role of four dimensions of IRFC, namely appropriateness, self-change efficacy, management support, and personal valence (benefits), in the aforementioned relationship.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical foundation

The relationship between training opportunities provided by an organization to its employees and the potential impacts of these opportunities on the employees’ commitment to their organization can be understood in the context of social exchange theory (Bashir & Long, Citation2015). Training opportunities provided by an employer can be considered a social exchange between the employing organization and its employees (Maurer et al., Citation2002; Newman et al., Citation2011). Training opportunities indicate that the organization invests in its employees, catalyzing their sense of obligation towards their organization (Ocen et al., Citation2017; Shore et al., Citation2006).

According to social exchange theory, providing employees with continuous training opportunities can be viewed as a signal to employees, indicating that the organization cares about them and appreciates their contributions. Therefore, according to social exchange theory, training opportunities not only have the potential to improve employees’ performance but also extend to cover the socio-emotional aspects of the relationship between the organization and its employees. Accordingly, employees will respond positively to this signal by showing more affective commitment to their organization (Bashir & Long, Citation2015; Bulut & Culha, Citation2010; Dhar, Citation2015; Ling et al., Citation2014; Newman et al., Citation2011; Ng & Dastmalchian, Citation2011).

3. Affective Organizational Commitment (AOC)

Recently, organizational commitment has been conceptualized by many studies as affective organizational commitment (AOC) or attitudinal commitment, since the attitudinal nature of organizational commitment can be better reflected by AOC than by continuance organizational commitment (COC) and normative organizational commitment (NOC) (Cohen, Citation2007; Dhar, Citation2015; Ehrhardt et al., Citation2011; Karatepe & Uludag, Citation2007; Solinger et al., Citation2008; Yi‐Ching Yi‐Ching Chen et al., Citation2012). Affective organizational commitment reflects an employee’s commitment to his/her organization and the extent to which the employee is emotionally attached to his/her organization (Ismail, Citation2016).

Previous studies have mainly focused on AOC rather than COC or NOC, since AOC has the strongest impact on employees’ general work-related behaviors, including employee turnover and performance (Albrecht & Marty, Citation2020; Froese & Xiao, Citation2012; Ouedraogo & Ouakouak, Citation2018). In this respect, COC reflects an employee’s commitment to his/her organization due to the lack of alternative job opportunities, while NOC reflects an employee’s commitment due to a sense of moral obligation. Meanwhile, AOC reflects an employee’s commitment to his/her organization because s/he is emotionally attached to his/her organization (Cohen, Citation2007; Dhar, Citation2015; Ehrhardt et al., Citation2011; Ismail, Citation2016; Karatepe & Uludag, Citation2007; Solinger et al., Citation2008; Yi‐Ching Yi‐Ching Chen et al., Citation2012).

In comparison to COC and NOC, AOC has received the most attention by researchers, since it captures the essential meaning of organizational commitment; namely an employee’s emotional attachment to his/her organization (Conway & Briner, Citation2012; Jin, Citation2018; J. Lee et al., Citation2018; Sharma & Dhar, Citation2016; Steyn et al., Citation2017). Meyer and Allen (1991, p. 67) defined AOC as “the employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with and involvement in the organization”. According to Krajcsák (Citation2020), AOC describes an employee’s emotional reliance on his/her workplace. An employee with a high level of AOC is dedicated to his/her coworkers, team, and the work environment in general and therefore enjoys work. Hence, it is possible that group identification and affective commitment have a positive relationship.

It has been argued that AOC is the most important and beneficial component of organizational commitment, since employees with a high level of AOC are more likely to accept the change initiatives adopted by their organizations (Jain, Citation2016). Accordingly, AOC has been used by numerous studies as the sole indicator of employees’ commitment to their organizations (Bulut & Culha, Citation2010; Dhar, Citation2015; Ehrhardt et al., Citation2011). In addition to their genuine willingness to remain employed by their organization, affectively committed employees are characterized by loyalty, belongingness, high levels of engagement with their organization, high levels of self-motivation, and a willingness to strive passionately to attain organizational goals and objectives. Evidently, AOC mirrors an employee’s attitudes towards his/her organization and can also be perceived as an employee’s investment of emotional resources in his/her organization (Brunetto et al., Citation2012; Sharma & Dhar, Citation2016).

A number of empirical studies on organizational commitment have revealed that AOC plays a vital role as an antecedent of many highly relevant work-related attitudes and behaviors, including intent to quit, organizational citizenship, absenteeism, turnover, job performance, and adaptability to organizational change (Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2013; Neves, Citation2009; Su et al., Citation2009). Specifically, AOC has been found to negatively correlate with turnover intention, actual turnover, and absenteeism, whilst it correlates positively with in-role and extra-role performance, and employees’ well-being (Kim et al., Citation2016; Wong & Wong, Citation2017).

Developing employees’ commitment to their organizations is a prominent topic studied by researchers in the field of human resource management practices, since adopting different human resource practices reflects the way that employees are treated in their organizations (Chambel et al., Citation2016; Malhotra et al., Citation2007). Human resource management practices, including training, are considered a long-term investment in employees, who perceive themselves to be a key source of competitive advantage, and a way of enhancing employees’ AOC (Camelo-Ordaz et al., Citation2011). In this regard, employees’ commitment to their organizations can be used to evaluate or measure the implications of adopted human resource management practices (e.g., training). Increased AOC may be measured in terms of employees’ job performance, as several empirical studies have evidenced a positive relationship between employees’ AOC and their performance (Steyn et al., Citation2017; Wong & Wong, Citation2017).

3.1. Individual Readiness for Change (IRFC)

Literature related to change management has recently started to focus on IRFC as an essential element contributing to the success of change processes within organizations (Goksoy, Citation2012; Haffar et al., Citation2019). Thus, the effective management of employees’ psychological transition before introducing any planned change is regarded as an integral part of achieving successful organizational change (Martin et al., Citation2005). Change management researchers have argued that the concept of IRFC is more valid and practical than the concept of individual resistance to change for better understanding individuals’ attitudes towards organizational change (Choi & Ruona, Citation2011). It can be argued that IRFC represents the most prevailing positive attitude that employees hold towards change initiatives (Rafferty et al., Citation2013).

Therefore, neglecting the central role of individuals in any change efforts may result in difficulties in the implementation of change initiatives or even the complete failure of these initiatives. In this regard, employees’ attitudes towards change initiatives form one of the most critical factors leading to difficulties or failure in the implementation of change processes (Rafferty et al., Citation2013). Employees’ attitudes towards a change initiative can be described as the organizational members’ negative or positive evaluative verdicts of this change, whereby these attitudes may be strong positive attitudes or strong negative ones. Hence, employees may receive a change initiative with contentment and excitement, or they may receive this change with outrage and fear, since change initiatives within an organization entail moving employees from known situations to unknown ones (Vakola & Nikolaou, Citation2005; Visagie & Steyn, Citation2011).

Individual readiness for change, according to Holt et al. (Citation2007, p. 235), reflects “the extent to which an individual or individuals are cognitively and emotionally inclined to accept, embrace, and adopt a particular plan to purposefully alter the status quo”. Interestingly, readiness for and resistance to change have recently gained increasing attention by change management researchers (Rafferty et al., Citation2013; Van den Heuvel et al., Citation2015), as most research on employees’ attitudes towards change initiatives has focused on readiness for and resistance to change (Visagie & Steyn, Citation2011). Bouckenooghe’s (Citation2010) review of studies which focused on attitudes towards change and which were published between 1993 and 2007 found that more than 90% of these studies had focused on readiness for or resistance to change.

Despite the importance of organizational change, literature has indicated that many change efforts fail to achieve their intended goals and lead to sustainable change (Cinite et al., Citation2009; Fuchs & Edwards, Citation2012; Lyons et al., Citation2009; Rafferty et al., Citation2013; Weiner et al., Citation2008). In a similar vein, change management research has indicated that rates of organizations’ failure to successfully implement change initiatives range between 28% and 70%, rates which are considered alarming for change management researchers and practitioners alike (Decker et al., Citation2012; Goksoy, Citation2012; McKay et al., Citation2013).

These failure rates have urged scholars to identify the individual and contextual motives that may contribute to the failure or success of organizational change (Choi & Ruona, Citation2011; Jones et al., Citation2005; Rafferty et al., Citation2013). Consequently, change management researchers have started focusing on the individuals within organizations and their fundamental role in the implementation of change initiatives. Thus, individuals’ attitudes towards change and its related concepts, such as readiness for change, commitment to change, acceptance of change, resistance to change, coping with change, openness to change, cynicism about organizational change, and adjustment to change, have gained an increasing amount of research attention (Bouckenooghe, Citation2010).

Individuals in any organization represent a key element for the success or failure of organizational change efforts. Hence, employees may be a major reason for the successful functioning of change efforts through their readiness for these changes, whilst their resistance to change may lead to the failure or difficult implementation of changes (Choi & Ruona, Citation2011; Jones et al., Citation2005). More importantly, developing IRFC has become an indispensable tool allowing organizations to successfully implement planned changes, since developing IRFC helps organizations reduce the detrimental effects of their employees’ resistance to change. In support of this claim, literature pointed out that readiness for change has a significant negative correlation with resistance to change (Haffar et al., Citation2019; K. Y. Kwahk & Lee, Citation2008).

There is consensus among organizational psychologists and scholars regarding the role of IRFC as a decisive factor in organizations’ endeavors for implementing effective and successful organizational change initiatives (By, Citation2007; Elias, Citation2009; Holt et al., Citation2007; Jones et al., Citation2005; Lyons et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, Elias (Citation2009) argued that implementing change initiatives without considering whether employees are psychologically ready for these changes results in cynicism and stress, eventually leading to reduced AOC among employees.

In this vein, Holt et al. (Citation2007) developed an instrument for measuring readiness for organizational change at the individual level. The authors concluded that readiness for change may be considered a multidimensional construct which is affected by the beliefs of the individuals within an organization. This includes the belief that 1) the employees are able to implement the planned change (self-change efficacy); 2) the planned change is appropriate for the organization (appropriateness); 3) the organization’s leaders and seniors are committed to supporting the planned change (management support); and 4) and the planned change is beneficial and helpful to the members of the organization (personal valence (benefits)).

Holt and colleagues concluded that IRFC is influenced by individuals’ beliefs regarding appropriateness (i.e., appropriateness of the change), which reflects their belief that the proposed change is an appropriate response to a present situation and would be beneficial for the organization. Meanwhile, self-change efficacy represents employees’ belief in their own capability to perform the proposed change, in addition to their confidence in their ability to successfully execute the suggested change.

Management support for a proposed change refers to the support of the leaders and managers of an organization in the implementation of a proposed change. Management support allows employees to feel that their organization will provide them with tangible support, including the necessary information and resources, for the successful implementation of the planned change. Finally, personal valence (benefits) refers to the organizational members’ belief that a proposed change will be of use for them. Personal valence includes an individual’s assessment of the costs and benefits resulting from the proposed change that will directly influence his/her role in an organization (Holt et al., Citation2007, p. 232; Rafferty et al., Citation2013).

3.2. Employees’ perceived benefits of training

Perceived benefits of training can be defined as “employees’ perceptions of the positive and favorable outcomes that can be acquired through attending training activities” (Yang et al., Citation2012AU: Please provide missing corresponding author details.). The potential benefits resulting from any training program conducted by an organization can be best understood through the norm of reciprocity, as these benefits are directed towards the two sides of the employment relationship (Aguinis & Kraiger, Citation2009). When employees feel that their participation in training activities holds benefits for them and their organization, they may be more willing to participate in these activities. Training activities are expected to produce positive outcomes (Dhar, Citation2015), which may include improved overall organizational performance directly (e.g., reduced costs, increased quality of services and production) or indirectly (e.g., decreased employee turnover, reputation construct, and social capital) (Aguinis & Kraiger, Citation2009).

With respect to employees’ benefits from training activities, training programs may increase employees’ self-confidence, creativity, and readiness for change, increase interaction between them, improve their behaviors and attitudes, and increase their commitment to and satisfaction with the organization (Donovan et al., Citation2001; Muñoz Castellanos and Salinero Martín, 2011). In the same vein, Phillips and Stone (Citation2002, p. 210) argued that “most successful training programs result in some intangible benefits. Intangible benefits are those positive results that cannot be converted to monetary values”. Newman et al. (Citation2011) posited that one of the intangible benefits of training is the increase in employees’ commitment to their organization, resulting from their growing enthusiasm to participate in more training activities. Accordingly, it can be argued that employees who perceive that they will gain benefits from training programs are likely to be stimulated to pursue and participate in training programs offered by their organization (Bartlett & Kang, Citation2004).

Employees’ perceived benefits of training fall into three categories, namely perceived job-, career-, and personal-related benefits (Nordhaug, Citation1989). These benefits are proposed to be reflected in employees’ work-related attitudes and increased emotional attachment to the organization (Ahmad & Bakar, Citation2003; Dhar, Citation2015). Perceived job-related benefits (PJRB), can be regarded as the usefulness of the acquired skills and knowledge for the advancement of the employee in his/her current job. These benefits create positive relationships between employees and their supervisors and enable employees to take the breaks they need when performing their jobs (Dhar, Citation2015; Noe & Wilk, Citation1993).

On the other hand, perceived career-related benefits (PCRB) are associated with the future career path of an employee, whereby training programs help employees obtain the skills and knowledge required for succeeding in future jobs. Therefore, career-related benefits can be viewed as the degree to which employees perceive that their participation in training programs helps them in determining and reaching their career objectives and provides them with the opportunity to follow new career paths (Al-Emadi and Marquardt, 2007; Bulut & Culha, Citation2010).

Perceived personal-related benefits (PPRB) refer to the outcomes that may directly or indirectly impact the work context and include psychological, political, and social results. Personal-related benefits can be viewed as the degree to which individuals perceive that their participation in training programs provided by the organization helps them with networking within the organization, contributes to their personal development, and enhances their performance (Al-Emadi and Marquardt, 2007; Bulut & Culha, Citation2010). Consequently, employees with positive feelings towards their participation in training programs believe that the outcomes of these programs may be beneficial for their job, career path, and personal advancement.

Employees’ perception that their participation in training programs will be useful for them and their organization is likely to lead to favorable training outcomes and increase employees’ willingness to participate in future training opportunities. In addition, employees’ perception that they will be able to practice and apply the acquired skills and knowledge in the workplace is also essential for achieving positive outcomes of training programs and increasing employees’ participation in future training opportunities (Bulut & Culha, Citation2010).

3.3. Employees’ perceived benefits of training and affective organizational commitment

Previous studies have indicated the presence of a positive relationship between employees’ perceived benefits of training and AOC (Al-Emadi and Marquardt, 2007). In this vein, Bartlett (Citation2001) concluded that career-related benefits had a significant positive correlation with AOC among employees. Personal-related benefits were also found to have a positive association with AOC, whilst job-related benefits were not found to have any correlation with AOC. Ahmad and Bakar (Citation2003) concluded that the three types of benefits that employees obtain from training programs contribute significantly to the development and maintenance of employees’ commitment to their organization. Further, these benefits have been found correlate strongly with AOC in particular, as compared to other types of organizational commitment (i.e., COC and NOC). Hence, the authors suggested that employees’ awareness of the potential benefits of their participation in training programs is likely to lead to increased emotional attachment to the organization. Thus, employees’ perceived benefits of training can be regarded as a tool for increasing employees’ participation in training opportunities.

Bartlett and Kang (Citation2004) reported that employees’ perceived personal-, career-, and job-related benefits had a significant positive correlation with their level of AOC. This indicates that employees who recognize that their participation in training programs is beneficial for their career, job, or personal life tend to be more affectively committed to their organization. The findings of Al-Emadi and Marquardt (2007) revealed that career- and personal-related benefits had a significant positive correlation with employees’ AOC. Meanwhile, job-related benefits were found to have a positive but insignificant correlation with employees’ AOC. However, the authors reported that the strongest antecedents to employees’ AOC to their organization were personal-related benefits, age, and years of service.

Similarly, Bulut and Culha (Citation2010) reported that employees who expect to obtain job-, career-, or personal-related benefits are more likely to be more affectively committed to their organizations. The authors concluded that the three types of training benefits had a significant positive correlation with employees’ AOC, which was also reported by Riaz et al. (Citation2013). Hence, training programs may lead to more positive outcomes when the participating employees are aware of the benefits of training and recognize their employers’ efforts, and this is likely to increase employees’ commitment to their organizations. Similar results were reported by Almodarresi and Hajmalek (Citation2015), Bashir and Long (Citation2015), Dhar (Citation2015), and Silva and Dias (Citation2016). These studies concluded that employees who perceive that attending training programs held by their organization is beneficial for their job, career, and personal growth are more likely to develop robust emotional bonds with their organization. It can therefore be argued that employees’ emotional attachment to their organization can be enhanced by increasing their awareness of the benefits of training. Accordingly, these findings demonstrate the potential benefits that can be gained from increasing employees’ level of AOC, which can be achieved by enhancing employees’ perceptions of the personal-, career-, and job-related benefits of training. Based on the foregoing, the current research will attempt to examine the following hypothesis:

H1: Perceptions of the benefits of training have a significant positive effect on affective organizational commitment among employees in the Jordanian national banking sector.

3.4. Perceived benefits of training and individual readiness for change

Globalization, changing markets, and technological advancements have become common features of the contemporary business environment. These dynamic characteristics have prompted organizations to seek to employ individuals with specialized skills and knowledge, in addition to the ability to adapt effectively to changing situations. Training can be regarded as a vital part of the overall strategy adopted by organizations to maintain competitive advantage, as training ultimately enables organizations to survive in such a dynamic and challenging business environment (Carbery and Garavan, Citation2005; Gil et al., Citation2015; Ouedraogo & Ouakouak, Citation2018).

Vakola (Citation2013) emphasized that IRFC can be developed by providing employees with training courses and development programs. In a similar vein, Haffar et al. (Citation2014) and Holt et al. (Citation2007) argued that the knowledge and personal skills acquired from training programs allow employees to feel more confident in adopting proposed change initiatives. Therefore, IRFC is positively impacted by perceived personal-related benefits of training. Accordingly, employees’ training has been shown to be positively connected to initiatives, organizational changes, and innovation (Carbery and Garavan, Citation2005; Gil et al., Citation2015). In particular, training plays an important role in promoting employees’ change efficacy (Chiang, Citation2010). Thus, organizations which plan to implement technological and organizational changes seek to provide their employees with continuous training programs to enable them to better perform in light of the adopted changes (Neirotti & Paolucci, Citation2013).

The need for training during the implementation of change processes arises from the fact that these changes will take place within the organization, requiring the organization’s employees to acquire novel skills and competencies. Consequently, the successful implementation and management of change initiatives requires organizations to upgrade their employees’ abilities, skills, attitudes, knowledge, and competencies by urging employees to participate in training programs (Andrews et al., Citation2008; García-Valcárcel & Tejedor, Citation2009; Ouedraogo & Ouakouak, Citation2018). In a similar vein, Vakola and Nikolaou (Citation2005) argued that providing employees with appropriate training programs makes them more resilient in adapting to change processes.

In this respect, Jones et al. (Citation2005) argued that the successful implementation of a change process necessitates specific capabilities, known as “dynamic capabilities”. Dynamic capabilities can be defined as the ability to update employees’ competencies according to the changing business environment, which can be achieved through the provision of training programs. These programs provide employees with the required skills and knowledge to perform their duties in accordance with any change made (Haffar et al., Citation2014; Holt et al., Citation2007). Hence, individuals who work in organizations concerned with providing their employees with adequate training tend to display high levels of IRFC, due to their confidence in their capability to successfully implement proposed changes.

Whilst studies in the literature have stressed the importance of training for organizations to successfully implement change initiatives (Olsen & Stensaker, Citation2014; Ouedraogo & Ouakouak, Citation2018; Vakola & Nikolaou, Citation2005), very few studies have investigated the relationship between employees’ perceived benefits of training and their level of readiness for change. Further, most studies on the relationship between training and IRFC have been in the fields of medicine and psychology and have focused on investigating the cessation of deleterious health behaviors (e.g., smoking and drug abuse) and initiation of positive health behaviors (e.g., healthy eating, exercising, weight management (Choi & Ruona, Citation2011; Madsen et al., Citation2005; McKay et al., Citation2013). It is worth mentioning that understanding the relationship between perceived benefits of training and IRFC strengthens the significance of training in strategic business decisions. This ultimately will move the view of training from a reactive perspective which perceives training only as a way for problem solving to proactive perspective in helping employees to be well prepared to any impending change (Gil et al., Citation2015). Based on the foregoing, the current research will attempt to examine the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceptions of the benefits of training have a significant positive effect on individual readiness for change among employees in the Jordanian national banking sector.

3.5. Individual readiness for change and affective organizational commitment

It has been argued that employees’ positive attitudes towards change (e.g., IRFC) may be considered as antecedents to some positive work-related attitudes, such as affective organizational commitment (Elias, Citation2009; Rafferty et al., Citation2013). In essence, employees’ emotional attachment to their organization, that is AOC, has been viewed to be one of the most widespread attitudinal outcomes of organizational change (McKay et al., Citation2013).

Leaders of organizations are often concerned with the potential outcomes of implementing change initiatives and the impacts these changes may have on employees’ attitudes. The literature suggests that adopted changes influence the relationship between employees and their organizations (Fedor et al., Citation2006). Therefore, there is a need to examine IRFC and its potential influence on employees’ level of AOC.

In a similar vein, Judge et al. (Citation1999) argued that coping with change (i.e., individuals’ attitudes towards change) must positively correlate with different outcomes which can be psychologically considered as meaningful and significant for both individuals and organizations. The authors argued that individuals who cope positively with change are more likely to be more committed to and satisfied with their organizations. Moreover, it has been evidenced that positive attitudes towards change initiatives, such as change acceptance, correlate positively with job satisfaction (Judge et al., Citation1999). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that IRFC, as an example of positive attitudes towards change, may enhance employees’ AOC.

Furthermore, a review of the change management literature revealed a lack of empirical studies that have investigated change events in relation to their potential consequences. It has been suggested that individuals’ positive perceptions towards the outcomes of change serve as a tool that can be used by organizations to promote their members’ commitment to the planned changes and to the organization in general (Fedor et al., Citation2006). In this respect, Elias (Citation2009) concluded that the growth need strength/ employees’ AOC relationship was fully mediated by employees’ attitudes towards organizational change. On the other hand, employees’ attitudes towards organizational change partially mediated the relationship between locus of control and employees’ AOC, and the relationship between internal work motivation and employees’ AOC.

Similarly, Madsen et al. (Citation2005) carried out a study among full-time employees working in four organizations in Utah, US. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationships between readiness for change, employees’ organizational commitment, and the social relationships among employees in the workplace. The results revealed that readiness for change had a significant positive correlation with employees’ organizational commitment. Likewise, Vakola and Nikolaou (Citation2005) carried out a study among employees of Greek organizations to examine the relationship between employees’ attitudes towards change, organizational commitment, and occupational stress. The results revealed an insignificant but positive relationship between positive attitudes towards change and organizational commitment, whilst a negative correlation was revealed between employees’ positive attitudes towards change and occupational stress. Further, the latter correlation was not moderated by employees’ organizational commitment.

Therefore, it can be argued that IRFC may play an important role in the development of employees’ AOC. In support of the above arguments, Chiang (Citation2010) concluded that perceived organizational change has been found to have a positive correlation with both employees’ attitudes towards change and employees’ organizational commitment. Based on the foregoing, the current research will attempt to examine the following hypothesis:

H3: Individual readiness for change has a significant positive effect on level of affective organizational commitment among employees in the Jordanian national banking sector.

3.6. Individual readiness for change as a mediator

Several studies which have examined the relationship between employees’ perceived benefits of training and level of AOC have not significantly considered the potential moderating effects of moderating and mediating variables. Thus, the current study attempted to investigate the mediating role of IRFC as a multidimensional construct, encompassing appropriateness, self-change efficacy, management support, and personal valence (benefits), in the relationship between employees’ perceived benefits of training and level of AOC. Essentially, the rationale behind examining the mediating or moderating variables in such a relationship is the fact that training opportunities may not be perceived and valued equally by all employees within an organization. Consequently, the impact of perceptions of training on level of commitment may vary from one employee to another (Ehrhardt et al., Citation2011; Maurer & Lippstreu, Citation2008).

Literature has argued that the relationship between employees’ perceptions of training and AOC is impacted by several factors which need to be identified and further examined (Bartlett, Citation2001); Ehrhardt et al., Citation2011);(Ismail, Citation2016).

Among the mediating variables which need to be examined by studies in the fields of human resource practices and organizational behavior is IRFC. On one hand, IRFC has been shown to be impacted by training and its related variables (Chiang, Citation2010; García-Valcárcel & Tejedor, Citation2009; Gil et al., Citation2015; Ouedraogo & Ouakouak, Citation2018), and on the other hand, employees’ AOC has been shown to be influenced by IRFC (Madsen et al., Citation2005; McKay et al., Citation2013).

Furthermore, according to Al-Gasawneh and Al-Adamat (Citation2020) and Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), the use of the mediating variable can be justified when there are relationships between the variables, such as between the independent variable and the dependent variable, the independent variable and the mediating variable, and the mediating variable and the dependent variable. The current study found all of the relationships mentioned above. Hence, IRFC was selected for investigation as a mediator between employees’ perceived benefits of training and level of AOC. Based on the foregoing, this study will attempt to examine the following hypothesis:

H4: Individual readiness for change mediates the relationship between perceived benefits of training and affective organizational commitment among employees in the Jordanian national banking sector.

3.7. Methods

The current study examined how national Jordanian bank employees’ perceived benefits of training (i.e., job-, career-, and personal-related benefits) affect their level of AOC by investigating the mediating role of individual readiness for change. A self-administered questionnaire consisting of two parts was used for the collection of primary data (Saunders et al., Citation2007). The first part was designed to collect data on the employees’ demographic characteristics, including age, level of education, and years of experience. Meanwhile, the second part included questions measuring the study’s major variables. The variables in the current study which are under investigation have been selected from well-established and validated scales and divided into three categories. First, employees’ perceived benefits of training was used as a multidimensional construct including job-, career-, and personal-related benefits as the independent variable. Second, the dependent variable was AOC, used as a unidimensional construct. Finally, IRFC was the mediating variable and was used as a multidimensional construct comprising appropriateness, management support, personal valence (benefits), and self-change efficacy. An expert panel of academics and bankers in Jordan reviewed the questionnaire items to assess face and content validity, and modifications were made according to their comments. As with regards to internal consistency, the Cronbach’s alpha values for all variables exceeded 0.70. The scale used to measure the three sub-dimensions of perceived benefits of training was originally developed by Noe and Wilk (Citation1993) and adopted by others (see Al-Emadi and Marquardt, 2007), with three items measuring job-related benefits, four items measuring career-related benefits, and another four items measuring personal-related benefits. The dependent variable, AOC, was measured using a six-item scale originally developed by Meyer et al. (Citation1993) and thereafter adopted by other scholars (see Dhar, Citation2015). Meanwhile, IRFC was measured using a twenty-item scale originally developed by Holt et al. (Citation2007) as an accurate measure of IRFC, as it treats IRFC as a multidimensional rather than unidimensional construct. This multidimensional construct comprises appropriateness, measured by 6 items; management support, measured by 5 items; personal valence (benefits), measured by 4 items; and self-change efficacy, measured by 5 items. In order to overcome the issue of common method variance, the measures in the current study were taken from different sources.

3.8. Sampling

The target population included 16 national banks operating in the capital of Jordan, Amman. Hence, foreign banks operating in Jordan and Jordanian national bank branches located outside of Amman were excluded. The sampling frame consisted of 18,923 employees working at different managerial levels (i.e., top, middle, and lower management) in the selected banks (Association of banks in Jordan, 2016). Stratified random sampling was used to select the study sample. This sampling technique allows for the representation of specific strata (groups) within the sampling frame, whereby the whole population can be accurately represented based on the criteria used for stratification (Zikmund et al., Citation2013). In turn, this increases the generalizability of the results to the whole population. The current study was carried out at the individual level of analysis that can be represented by employees who work in top, middle, and low management in national Jordanian banks and have undergone training programs during the previous two years. A list of employees who had undergone training during the previous two years was obtained from each of the selected banks.

The sample was drawn based on the annual report of Jordanian banks for 2016, which was issued by the association of banks in Jordan (Association of banks in Jordan, 2016). In addition, the sample size for the current study was determined based on the table developed by Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970), which states that if the population size is 20,000, the sample size should be 377. Due to the problems that could result from low response rate, and in order to guarantee that the retrieved, filtered, and screened questionnaires match the minimum number of (377); (20%) extra questionnaires have been considered for distribution proportionally to all (16) banks under investigation, resulting in the final and actual distribution of (451) questionnaires. After distributing the questionnaires at each bank, the researcher followed up on the respondents’ progress in the completion of the questionnaires and collected the questionnaires upon their completion. After filtration and screening process to eliminate questionnaires with extreme and/or missing sections, a total of 421 questionnaires were included for analysis, indicating a response rate of 93.3%.

Structural equation modeling was used for data analysis for several reasons. First, structural equation models have been proven successful in performing estimations and model development, as compared to regressions, when assessing mediation. Secondly, partial least squares path modelling is more suitable for real-world scenarios and complex models (Centobelli et al., Citation2019; Fornell & Bookstein, Citation1982). Since this study aimed to investigate the relationships between three second-order variables with seven sub-dimensions in total, it was necessary to use PLS-SEM techniques following a two-stage approach to ensure increased prediction accuracy (Ringle et al., Citation2012; Saris et al., Citation2007). Also, most data in the social sciences field are prone to normality problems (Osborne, Citation2010), and hence, PLS path modelling is suitable for such data as it does not require the data to be normal (Chin, Citation1998). Thus, PLS path modelling was considered to be the best option for preventing the occurrence of normality problems during data analysis. Finally, PLS-SEM provides more valid and meaningful results compared to analysis methods such as SPSS, which requires several separate analyses and often provides conclusions which are less clear (Singh et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, SEM is a powerful statistical tool for use in behavioral and social sciences research, as it can simultaneously test several relationships (Tabachnick et al., Citation2007).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement model

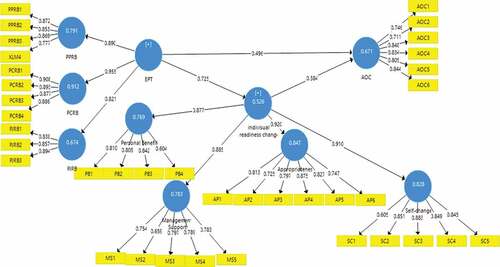

This study included two second-order variables and one first-order variable. Employees’ perceived benefits of training included perceived personal-related benefits, perceived career-related benefits, and perceived job-related benefits as first-order constructs. Meanwhile, individual readiness for change included personal valence (benefits), management support, appropriateness, and self-change efficacy. Affective organizational commitment was handled as a first-order construct in order to enrich the recognition of its conceptual and consensus aspects. Additionally, the second-order variables were used to reduce the number of associations and number of hypotheses to be addressed in the structural model, as this allows the PLS path model to be easily interpreted (J.F. Hair et al., Citation2016). This study utilized a two-stage approach. During the first stage, the repeated indicator approach was used, whereby the first-order scores were collected for first-order constructs. During the second stage, the weighting of the first-order variables was utilized in the calculation of the second-order constructs’ composite reliability (CR) and average variance extract (AVE). Convergent validity and discriminant validity were used in the evaluation of the measurement model. The convergent validity evaluation included the analysis of the following: CR, AVE, and factor loading.

As shown in . The measurement model. The design elements’ preliminary standardized factor loadings ranged between 0.655 to 0.955, all greater than the recommended minimum value of 0.6 (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2019). The AVE values ranged between 0.575 and 0.800, all greater than the recommended minimum value of 0.5 (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2019). Finally, the CR values ranged between 0.852 and 0.941, all greater than the recommended minimum value of 0.7 (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2019).

demonstrates that all of the latent variables in the IRFC dimension had HTMT values of less than 0.90, and thus, each latent construct measurement was completely distinct from the other (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The measuring scale was found to be reliable and valid for assessing the constructs and their related items in the IRFC dimension after the discriminant validity of the measurement model for that dimension was verified. Furthermore, all of the HTMT values of the latent constructs in the overall model variables ranged between 0.452 and 0.882, falling below the minimum value of 0.90 (see ). This study demonstrated that each measurement of a latent construct was completely discriminating (Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Table 1. Measurement model

Table 2. Discriminant Validity (HTMT)

In conclusion, the convergent validity and discriminant validity results obtained for the measurement model illustrated the suitability and accuracy of the measuring scale in the assessment of the constructs and their respective items in the CFA model. and provide the analysis results for convergent validity and discriminant validity, respectively.

4.2. Structural model

Before examining the size and relevance of the hypothesized parameter estimates (depicted in the path diagrams by one-headed arrows), a structural model evaluation focusing largely on the overall model fit was conducted (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2019). The final step in this evaluation is to verify the structural model’s accuracy using the hypothesized links between the identified and assessed variables.

As evident in and , the R2 values for AOC and IRFC were 0.671 and 0.526, respectively. Thus, 67.1% of the variation in AOC was predicted by EPT and IRFC, while 52.6% of the variation in IRFC was predicted by EPT. The R2 values met the 0.19 cut-off value recommended by Chin (Citation1998). The Q2 value for GPI of 0.354 was much higher than zero, denoting predictive relevance to the model (Chin, Citation2010). The model showed a sufficient level of fit and substantial predictive relevance. Also, the VIF values were 1.622, 1.391, and 1.254, all of which were below 5 (Hair et al., Citation2014). For the predictors of AOC, the p-values for EPT and IRFC were 0.003 and 0.001, respectively. For the predictors of IRFC, EPT had a p-value of 0.000, denoting that the chance of achieving prediction through absolute p-values are 0.01 and 0.05. Also, the path coefficient (S, B) values for (EPT > AOC), (IRFC > AOC), and EPT > IRFC were 0.496, 0.384, and 0.725, respectively. This showed that the relationships were positive, supporting hypotheses H1, H2, and H3.

Table 3. Hypothesized direct effects structural model

Table 4. Displays the results of the Bootstrapping, which showed that the indirect effect of EPT on AOC through IRFC was positive and statistically significant at the 0.05 level; β = 0.279, T-value = 4.177, P-value = 0.000. The indirect effect of Boot CI Bias Corrected did not straddle a 0 in between, meaning that a mediation effect would be in place (LL = 0.169, UL = 0.441. The results indicated that the mediation effect was statistically significant, and so hypothesis H4 was supported

4.3. Indirect EFFECT OF THE CONStructs

5. Discussion and conclusion

The findings of the current study shed light on the significance of training as a practice which can be adopted by Jordanian national banks to enhance their employees’ levels of AOC. Ultimately, increased AOC among bank employees will reflect in improved productivity and performance and the delivery of high-quality services to the banks’ customers. Accordingly, the aim of the present research was to examine the relationship between perceived benefits of training and level of AOC among a sample of employees working in Jordanian national banks. Further, the mediating effect of IRFC on this relationship was investigated. The study findings provide strong support for the contentions of social exchange theory, which formed the theoretical background of the study.

The current findings revealed that employees’ perceptions of training benefits contribute to enhance their level of emotional bonds to their banks through their perceptions of personal, career, and job-related benefits. In which, banks’ employees who perceive that their participation in training programs brings several benefits (returns) such as career path improvement tend to display higher levels of affective attachment to their banks (Bulut & Culha, Citation2010; Al-Emadi and Marquardt, 2007). Moreover, banks’ employees who perceive that their participation in training programs brings several benefits in terms of the usefulness of the acquired skills and knowledge in an employee’s advancement in his/her current job as well as the positive relationships between employees and their supervisors tend to manifest increased levels of AOC. Furthermore, employees’ perceptions of their personal-related benefits in terms of their networking within the organization and their progress with respect to their personal development influences how affectively committed they are to their banks.

The current finding is consistent with the findings of several studies which have examined the pivotal role of training in predicting IRFC (Ardestani et al., Citation2014; Neirotti & Paolucci, Citation2013; Ouedraogo & Ouakouak, Citation2018). These studies concluded that training programs are essential for preparing employees for change initiatives to be implemented by their organization. Thus, the benefits of training are not limited to improving employees’ skills and knowledge and allowing them to solve work-related problems. Rather, training facilitates the successful implementation of change initiatives and innovative solutions since training increases employees’ self-confidence and provides them with the knowledge and skills they require to effectively perform their duties under new changes. This finding indicates that positive employees’ perceptions regarding training benefits will in turn create positive variations in IRFC.

With regard to the relationship between IRFC and employees’ AOC, the findings revealed that employees’ AOC is positively and significantly influenced by IRFC. In this respect, and apart from the direction of the causality between IRFC and employees’ AOC, reviewing the related literature that examined this relationship revealed a positive and significant correlation between these two variables. Accordingly, the finding of the current study is consistent with the findings of previous studies that investigated the relationship between IRFC and AOC (Mangundjaya, Citation2012; McKay et al., Citation2013; Ouedraogo & Ouakouak, Citation2018; Straatmann et al., Citation2018; Visagie & Steyn, Citation2011). All the above studies concluded that employees’ commitment to their organization help them to be psychologically ready to be supportive for the change initiatives adopted by their organizations (Herscovitch & Meyer, Citation2002; Hill et al., Citation2012; Straatmann et al., Citation2018). Similarly, the current finding is compatible with the results found by scholars who concluded that employees’ positive attitudes towards change process (e.g., IRFC) can be thought as a best antecedent to positive employees’ work-related attitudes such as employees’ AOC (Elias, Citation2009; Rafferty et al., Citation2013).

The finding that IRFC was positively and significantly influenced by their positive perceptions of training programs indicates that their psychological readiness for adopting change initiatives will be enhanced by their positive perceptions of training programs provided by their employing banks, which will be positively reflected in an increased employees’ AOC. Therefore, when IRFC is improved due to the positive impact of EPT, this positive effect will be extended through IRFC to enhance employees’ AOC to their employing banks. This finding suggests that providing employees with training programs enables banks’ employees to be more psychologically ready to adopt and implement changes initiatives. Employees’ self-efficacy will be increased through participating in training programs, and this will be reflected in an improved employees’ self-confidence in performing their tasks under the new environment of change (Gil et al., Citation2015; Carbery and Garavan, Citation2005). This eventually will be manifested in an enhanced employees’ AOC. In view of this result, providing employees with training opportunities along with creating positive employees’ perceptions regarding these programs in terms of the potential benefits improve their readiness to adopt change initiatives, therefore, employees will in turn reciprocate in form of enhanced employees’ AOC.

Accordingly, the current findings provide a valid evidence that can be employed to extend the theory, which indicates that EPT represent a solid foundation for an effective, enduring organization-employee social exchange relationship (Balkin & Richebé, Citation2007; Bashir & Long, Citation2015; Dhar, Citation2015). In conclusion, the current study contributes to the knowledge by providing an empirical evidence that IRFC has independent functions in the fields interrelated to the perceived human resource management practices and organizational behavior in particular, training as well as employees’ affective commitment to their organizations. This has been achieved by integrating the construct of IRFC which represents a multidimensional framework into the association between EPT and employees’ AOC. Furthermore, the current research relies on a large sample, in which the findings can be generalized to the entire population of the current research, and this is perfectly consistent with the deductive approach (Saunders et al., Citation2007).

In addition, the findings of the current research affirm to some degree the conclusions have been made by previous empirical studies (Bashir & Long, Citation2015; Bulut & Culha, Citation2010; Dhar, Citation2015). In which these studies concluded that EPT are relevant to their AOC. This relationship has been found in different work settings as well as different cultures (e.g., the USA, New Zealand, China, Turkey). This suggests that EPT and its subsequent impact on employees’ work-related attitudes (e.g., AOC) can be generalized across cultural borders.

Meanwhile, the current findings provide a strong credence to the theoretical background of the current research; social exchange theory and its popular norm “reciprocity”. Clearly, training opportunities are provided to the employees not only to promote their performance and productivity, but it also aims to create a social exchange relationship between an employee and his/her bank. Since it has been argued that an organization’s investment in their employees’ training can be used as a tool to catalyze the sense of employees’ obligation to positively discharge this investment by showing high levels of affective commitment to their organization.

5.1. Limitations and future work

Human resource development researchers may replicate this study by using other employees’ work-related attitudes (e.g., turnover intention, job involvement, work engagement, job satisfaction) in order to seek for other potential intangible outcomes of employees’ training. Researchers are required to consider the use of employees’ AOC in addition to other important employees work-related attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction) and investigate these variables as potential outcomes of employees’ training. For example, investigating the impact of EPT on employees’ AOC along with employees’ job involvement or employees’ job satisfaction.

Second, examining the impact of employees’ AOC on other outcomes variables would be useful for future studies in this area, since the literature emphasized that AOC plays a vital role as an antecedent of many highly relevant work-related attitudes and behaviors, including intent to quit, organizational citizenship behavior, absenteeism, turnover behavior, and job performance, (Breitsohl & Ruhle, Citation2013; Neves, Citation2009; Su et al., Citation2009). Finally, researchers are required to consider the impact of other mediating variables, as well as considering the role of moderating variables in the association between EPT and their affective commitment to their organizations. In this respect, the literature suggested that employees’ training have a direct or indirect influence on employees’ affective commitment to their organizations.

On the other hand, the current research is restricted by few limitations. Therefore, the findings must be interpreted by recognizing these limitations. However, these limitations do not indicate that there were problems with the current research, rather, they indicate that there are few restrictions on what can be inferred from the findings. In the first place, the current research employed a survey strategy which has inherent limitations in the research design such as, differences in individuals’ knowledge and memory lapses, which in turn may affect the quality of the collected data. These inherent limitations can be seen in the studies that investigate employees’ perceptions of work-related practices (Schneider et al., Citation1996). However, several procedures have been followed in order to decrease these limitations including pretesting the questionnaire in order to make certain that the wording was familiar and an unambiguous to the respondents, straight to the point and not making the respondents to be confused.

Moreover, standard wording principles were accurately followed by the researchers and the terms employed in the questionnaire were comparable to the terms found in the setting of the local organizations. In addition to the simplicity and clarity of questions included in the questionnaire that enabled the respondents to easily understand and answer them. Moreover, the questions were not biased since they were not designed to guide the respondent or prevent him/her to certain answers. In this respect, triangulated research design can be employed in future studies, using qualitative methods to collect data such as interviews, focus groups, observations that may enable researchers to obtain a profound understanding of the research variables investigated. Moreover, it may enable researchers to have a more precise and obvious picture of the different research variables and the relationships between them.

Another limitation in terms of cross-sectional data that can be represented by the causality direction. In which conclusions regarding the direction of causality between research variables cannot be drawn. Despite the consistency to some degree between the findings of this study and its hypotheses that have been built on the existing literature, the possibility that the causality between the research variables functions in a contrary direction to what has been hypothesised cannot be ruled out. It is worth noting that the relationship between EPT and their affective commitment is reciprocal and dynamic (Yang et al., Citation2012). This indicates that EPT influence their affective commitment to their banks. On the other hand, the existing level of employees’ AOC guides their perceptions of training opportunities provided by their banks. For example, the current research hypothesized that employees who perceived that their participation in training programs would result in obtaining several types of benefits tend to be more emotionally attached to their banks. However, the opposite direction of causality has not been investigated, that is, employees with a high level of AOC will evaluate and perceive the training opportunities provided by their banks more positively. Importantly, the issue of causality can be solved by using a longitudinal research design in the future studies.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ayman Mansour

Dr. Ayman Mansour, the first author of this paper, graduated from the University of South Wales in the United Kingdom. My research interests are in three areas of management, the first of which is training as a single practice of human resource management practices. Second, organizational behavior, such as organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, job satisfaction, and turnover. Third, change management, namely change readiness, and change resistance.

The author is particularly interested in examining the effects of employees’ perceptions of implemented human resource practices such as training on various employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors, particularly during periods of organizational transformation. Since the researcher has been working in the National Jordanian banking sector for five years, he has developed an epistemological curiosity about how training programs in this sector might improve employees’ affective commitment to their banks. Future publications may be conducted in the subject of online training and its impact on employee attitudes and behaviors, particularly during Covid-19.

References

- Abd Rahman, A., Ng, S. I., Sambasivan, M., & Wong, F. (2013). Training and organizational effectiveness: Moderating role of knowledge management process. European Journal of Training and Development, 37(5), 472–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591311327295

- Aguinis, H., & Kraiger, K. (2009). Benefits of training and development for individuals and teams, organizations, and society. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 451–474. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163505

- Ahmad, K. Z., & Bakar, R. A. (2003). The association between training and organizational commitment among white‐collar workers in Malaysia. International Journal of Training and Development, 7(3), 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2419.00179

- Albrecht, S. L., & Marty, A. (2020). Personality, self-efficacy and job resources and their associations with employee engagement, affective commitment, and turnover intentions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(5), 657–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1362660

- Al‐Emadi, M. A. S., & Marquardt, M. J. (2007). Relationship between employees’ beliefs regarding training benefits and employees’ organizational commitment in a petroleum company in the State of Qatar. International Journal of Training and Development, 11(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2419.2007.00269.x

- Al-Gasawneh, J., & Al-Adamat, A. (2020). The mediating role of e-word of mouth on the relationship between content marketing and green purchase intention. Management Science Letters, 10(8), 1701–1708. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.1.010

- Almodarresi, S. M., & Hajmalek, S. (2015). The effect of perceived training on organizational commitment. International Journal of Scientific Management and Development, 3(12), 664–669. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Seyed-Mahdi-Alhosseini-Almodarresi/publication/331672753

- Andrews, J., Cameron, H., & Harris, M. (2008). All change? Managers’ experience of organizational change in theory and practice. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 21(3), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810810874796

- Apospori, E., Nikandrou, I., Brewster, C., & Papalexandris, N. (2008). HRM and organizational performance in northern and southern Europe. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(7), 1187–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802109788

- Aragón-Sánchez, A., Barba-Aragón, I., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2003). Effects of training on business results1. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(6), 956–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958519032000106164

- Ardestani, A., Teymournezhad, K., & Ahmadvand, S. (2014). An investigation on different factors influencing perceived organizational change. Management Science Letters, 4(5), 1033–1038. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2014.3.006

- Armenakis, A. A., & Bedeian, A. G. (1999). Organizational change: A review of theory and research in the 1990s. Journal of Management, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500303

- Ashar, M., Ghafoor, M., Munir, E., & Hafeez, S. (2013). The impact of perceptions of training on employee commitment and turnover intention: Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 3(1), 74–88. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v3i1.2924

- Balkin, D. B., & Richebé, N. (2007). A gift exchange perspective on organizational training. Human Resource Management Review, 17(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.01.001