Abstract

Thisis the first study that explores consumer perception, preferences, and barriers in the purchase of non-certified organic food. The qualitative approach was applied to investigate the phenomena in real-life settings. Twenty-eight interviews were conducted from organic shoppers in specialized organic food markets. Data were analyzed from detailed parts to categories, themes, dimensions, and codes. Finding shows that organic food buyers are well aware of organic food benefits by virtue of its production methods. Although there are similarities in results between certified and non-certified organic food, however, many unique themes such as subcategories of health motives, various dimensions of trust, role of sales person, inelastic price, role of organic food cues, deceptive marketing, etc. are explored. Based on consumption motives, several categories of organic food consumers are also reported. The research has contributed to the literature by offering a consumer decision map that depicts important factors that play a vital role in the purchase of non-certified organic food. The pragmatic insight offered in this study can assist growers, enterprises, and policy makers in developing consumer understanding especially in ninety two other countries operating without organic food regulations. The results will be useful in developing a quantitative model for future studies.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The results of this study confirm that growing food scandals have ruined the reputation of conventional food products. As a result, consumers became health conscious and they have developed good understanding and motivation to consume organic food. This study further explores that trust plays a vital role in the purchase of organic food especially due to inadequate organic certification and labelling. Several unique dimensions of trust are explored in the study. Furthermore, consumers are found to be willing to pay premium prices, while many consumers showed their concerns that due to lack of competition, organic products are overpriced. Likewise, insufficient availability is also a barrier in developing organic food market. Imported organic food products from EU and US are preferred in value addition food category. From the policy perspective, organic agriculture can be an emerging source of entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment, which can contribute to rural development of under developing countries like Pakistan. The findings could be useful for retailers to learn the art of marketing organic food products.

1. Introduction

Food consumption patterns have been constantly evolving with changes in social values, technological advancement, and consumer lifestyle. However, sustainability is considered at the heart of organic agriculture since its increasing consumption is often regarded as a sustainable food provisioning system (Mørk et al., Citation2017; Vittersø & Tangeland, Citation2015). The dynamic growth of the organic food markets has enforced marketing researchers to explore the insights of consumers. Organic food is emerging as a combination of traditional and innovative food production, processing and preservation methods with contemporary marketing practices (Thøgersen & Crompton, Citation2009). It became the most popular food segment in the ethical and sustainable product line (Juhl et al., Citation2017), and certified organic food has gained greatest momentum in recent years (Rizzo et al., Citation2020). Healthy, natural, organic, sustainable, ethical, authentic, tasty, and humanitarian are common words used to label organic food, providing a recurrent persuasive marketing discourse for consumers of natural products (Freyer & Bingen, Citation2015). As a result of transformation in the food industry, food producers and enterprises have started redesigning their marketing strategies with much focus on environmentally friendly products for sustainable growth, especially to create a positive attitude of global consumer towards their brands (Olsen et al., Citation2014).

Food safety issues have also increased the demand and ultimately the scholastic interest to study organic food marketing in emerging economies of Asia such as Thailand and China (Pedersen et al., Citation2018). The rising consumer awareness and increase in per capita income of Asian countries are also growing with organic demand in these countries with stable market development (Aryal et al., Citation2009; Pedersen et al., Citation2018; Willer et al., Citation2018; Yadav & Pathak, Citation2016). The unique national context (e.g., differences in national food cultures, organic agriculture’s share of total agriculture, and the maturity of the organic market) depicts a distinctive scenario of each native market with respect to consumer preferences and choices of organic food products (Thøgersen & Crompton, Citation2009).

The demand of organic food is on hype in Pakistan, and there are signs that markets are maturing with increasing growth rates in the last few years (Poerting, Citation2015). The area under naturally organic agriculture or organic by default in Pakistan is about 1.51 million hectares as compared to inorganic that is 22.6 million hectare (Musa et al., Citation2015). There is an emerging supply chain of branded organic food products in Pakistan that flow through various organic food enterprises and are sold against self-declaration methods. Since, Pakistan is 26th largest economy with respect to purchase price parity, thus, development of the organic food industry and promotion of organic food products based on the findings of present research can assist in encouraging sustainable consumption—as food consumption plays a dominant role in overall consumption. Therefore, we can argue that present research makes a strong case to study the consumption pattern from a sustainable perspective, as they exist within broader societal and global fabrics (Prothero et al., Citation2011).

There are relatively few studies on organic food in regional context of Asia (Rahman & Noor, Citation2016; Al-Swidi et al., Citation2014) while also few studies have looked at organic food consumers in Pakistan (see Al-Swidi et al., Citation2014; Akbar et al., Citation2019; Asif et al., Citation2017; Mangan et al., Citation2016; Memon, Citation2013; Poerting, Citation2015; Sarfraz & Abdullah, Citation2014). However, the rigor of consumer research was questionable in aforementioned studies conducted in Pakistan, since, data were collected from general consumers instead from organic food consumers.

Although several mapping techniques have been used on organic food consumers for the purpose of analyzing concept associations and links, for instance, multidimensional scaling and laddering are associated with the means-end chain theory and attribution theory (Hasimu et al., Citation2017). However, these theories were found to be not suitable for immature organic food consumers in underdeveloped Pakistani market especially where the consumers awareness level is yet to explored. Further, in broader discussions, there is a sense in the field of management studies that the pursuit of theory building has detracted the scholars from the applied contribution to practice specifically to address significant, unresolved issues (George et al., Citation2014). In view of said backdrop, the present study was more focused on applied problem and research questions rather epistemological or ontological theoretical assumptions (Creswell et al., Citation2003). Furthermore, using previous theories in qualitative research can bias the data, since it is not testing of theory (Merriam, Citation1998). However, pre-existing theory can provide a crucial challenge to theory building in a unique context, wherein the existing literature may not be valid to explore the phenomena. It can lock the analytical focus and restrict the researcher from revealing new insights and theoretical breakthrough (Andersen & Kragh, Citation2010). Therefore, the research problem due to its complex nature was explored in present study in accordance with the generic qualitative and inductive approach (Merriam & Tisdell, Citation2015)—not underpinned by a specified theoretical perspective (Holloway & Todres, Citation2003). According to Lim (Citation2011), the generic approach aims at a rich description of the phenomenon under investigation. This means that the methods within generic qualitative approaches are generally “highly inductive; the use of open codes, categories, and thematic analysis are most common” (Lim, Citation2011, p. 52). However, utmost care has shown that lack of theoretical knowledge will not lead the findings to replicate the existing literature and further data are organized and interpreted in such a way that novel insights could be explored and reported with clarity (Andersen & Kragh, Citation2010) particularly with the help of theoretical triangulation.

The current paper is organized into four sections: first, it provides a contextual analysis of organic agriculture globally and in Pakistan. Second, it reviews the literature in context of organic food consumption and highlights the gaps, which is followed by research methods. Finally, it presents the results of qualitative data and discuss it through theoretical interpretation to draw a conclusion and practical implications.

2. Literature review

The inappropriate use of agrochemicals, including pesticides, herbicides, antibiotics, growth hormones, and their residues in food stuffs, is a known source of modern illnesses. In response to several food scandals, which are creating serious threat to human health and societies; the national and international organization along with government institutions has started playing an active role in awareness activities towards organic food (Ling, Citation2013). The rising consumer awareness and increase in per capita income of Asian countries show major potential of organic food for Asia (Willer et al., Citation2018). Consumer interpretation of the term organic is diverse within various contexts, while the purchase decision of organic food is based on subjective experiences and perception about it (Hughner et al., Citation2007). There are diverse awareness levels and understanding about the concepts of organic food among consumers of various regions (Hamzaoui Essoussi & Zahaf, Citation2009). Moreover, consumers’ awareness, knowledge, and information about organic food can play a vital role in understanding their preferences towards organic food. Padiya and Vala (Citation2012) also support the notion that respondent’s belief about organic food in India has a direct dependence on the source of awareness, wherein knowledge about organic food plays a significant role in developing their purchasing attitudes. Aschemann‐Witzel and Zielke (Citation2017) in consensus with several studies also report that the consumer knowledge about organic food is positively related to willingness to purchase (WTP) of organic food. However, it is pertinent to mention that organic food segment varies from market to market based on the development phase, market structure, awareness level, climate conditions, government support, culture and other such factors. Thus, there is an immense need to explore the consumers’ awareness, and knowledge about organic food especially in non-regulated markets.

RQ- I. What is consumer understanding and awareness about the term organic food?

Extensive literature in developed and regulated markets has identified the factors that influence consumer behavior, i.e. Padel et al. (Citation2005) revealed various reasons behind consumer motivation to purchase organic products, i.e better nutrition, reduced health risks, social aspects, and support of local farming, fair market, and environmental awareness. Hughner et al. (Citation2007) recognized several factors while exploring the phenomena that why people purchase organic food. They found health consciousness, better taste, environmental concerns, food safety issues, trust deficit on conventional food, animal welfare, benefit to local economy, more wholesome, nostalgia, and fashionable/curiosity as major motives for consumption of organic food. A metastudy by Hemmerling et al. (Citation2015) shows that in forty studies, the consumers’ perceptions, beliefs, associations, and expectations from organic products were related to health and/or environment protecting aspects. They further report that seventeen studies indicate its consumption due to nonexistence or with fewer chemicals and ,pesticides, while other eighteen studies highlight consumer association, due to good or better taste; however, in seven studies, respondents prefer organic food for the reason of good or better quality. Furthermore, Rana and Paul (Citation2017) also revealed that in India, health-conscious consumers more prefer organic food and similarly in developing countries, the demand for organic food may exist for food safety purposes. Likewise, Pacho (Citation2020) in the context of developing countries reports increasing non-communicable diseases as an important factor towards growing knowledge, health consciousness, and ultimately consumption of organic food. Vigar et al. (Citation2020) in a systematic review reports that despite significant positive outcomes in longitudinal studies, increased organic intake was associated with reduced incidence of infertility, birth defects, allergic sensitization, otitis media, pre-eclampsia, metabolic syndrome, high BMI, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Organic food is also achieving popularity as an immunity booster food (Gumber et al., Citation2021). However, the non-regulated and specifically the purchase of non-certified organic food is still an unexplored avenue in this regard, that either non-certified organic food is equally considered safe food or there are other factors that contribute towards its purchase. Thus, such unexplored phenomena lead us to following research question.

RQ-II. Why do consumers buy organic food especially when it is non-certified?

In a recent couple of decades, the construct of “trust” has been a focus of attention among food risk scholar, mainly due to increasing food scandals that have threatened the food system. Consumption of products involves several risks, while consumer always strives to eliminate these risks by adapting risk-reduction strategies (Chen, Citation2013), such as brand and store image, brand reputation, and label references, which may enhance trust at the same time (Hamzaoui-Essoussi et al., Citation2013a). In contrast to conventional food, the organic food practices requiremore strict parameters by chain members to ensure trust, credibility, and quality to consumers, since there are marginal differences in visual and sensorial characteristics among both categories (Thøgersen et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, organic food has a credence attribute and its purchase requires more expertise and knowledge by consumers to build their trust (Nuttavuthisit & Thøgersen, Citation2017). Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen (Citation2017) also support the notion that to hedge the risk, credence goods such as green products always required consumer trust as prerequisite for establishing markets particularly if they are of premium price. Indeed, due to growing food safety issues, debate on consumer trust particularly in short food supply chains became a vital component of the food system (Giampietri et al., Citation2018). This is especially true when organic food is non-certified. Thus, the role of trust cannot be ignored in this food segment. In context of organic food consumption in Asian markets, Hsu et al. (Citation2016) suggest that in Taiwan, development of the organic food industry requires the establishment of correct knowledge and concepts through its effective promotion. The study in the context of Taiwan concludes that details of authentication sources and traceability about organic food products is a good source of consumer awareness about organic food, while such practices contribute to developing marketing strategies towards building consumer trust (Liang, Citation2016). Therefore, the above discussion leads us to a research question that how consumers trust non-certified organic food.

RQ- III. How do consumers trust on non-certified organic food?

Certain obstacles and notable deterrents in the purchase process of organic food have also been reported while ploughing through a plethora of literature. Rödiger and Hamm (Citation2015) in meta-analysis of 194 articles explore that the majority of studies connected to consumer behavior are mentioning the price issues as a major barrier in organic food purchase. In the same line, Aschemann‐Witzel and Zielke (Citation2017) support the notion that with respect to the consumer policy perspective, the price as a barrier in purchasing of organic food requires appropriate action and proactive approach towards sustainable consumption. Furthermore, in some cases, price also acts as an important quality cue in the case of inadequate information about intrinsic quality cues (Acebrón & Dopico, Citation2000; Zeithaml, Citation1988), while a meta-regression concludes that expensive organic food triggers consumer purchase intentions (Massey et al., Citation2018). However, in the case of non-certified organic food, this will be more interesting to know that either without certification cost, the organic is still sold on premium prices and what are other factors in the domain of pricing that affect consumer purchase. Several studies have also reported the impact of organic food availability on the consumer decision process and indicate it as a significant barrier (Paul & Rana, Citation2012). Moreover, inadequate merchandising, distrust on organic certification boards and labels, ineffective marketing, dissatisfaction on food traceability, and lack of sensory appeals are also found as a notable barriers in purchase of organic food (Hughner et al., Citation2007). John Thøgersen et al. (Citation2015) also revealed that most of the participants in Thailand were found aware of organic food but could not explain its qualifying characteristics properly in detail, while many were confused with name reference and could not differentiate between organic and other safe products. The aforementioned literature identified several themes, which have certainly helped in identifying the following research question to answer.

RQ—IV. What are the barriers in purchasing non-certified organic food?

It can be argued that findings of previous studies based on certified organic food from developed and regulated markets may not completely be generalized and/or valid for non-regulated markets like Pakistan—where organic food policies are still in process (Willer et al., Citation2018) and organic food is sold as non-certified on self-declaration of retailers. However, no study has explored the purchase of non-certified organic food in the qualitative perspective. Thus, this study addresses a significant avenue for marketing theorists and practitioner. Furthermore, its findings can have vital implications for countries operating without organic food regulations and where organic food is sold without certification. Given this unique nexus, the present study is undertaken to understand the challenges to consumers in the purchase of non-certified organic food.

3. Methodology

The research approach to answer these questions was qualitative. The qualitative approach has helped in identifying what “people do, know, think, and feel” (Patton, Citation2002, p. 145) about the purchase of non-certified organic food in Pakistan. Moreover, qualitative research has always had a strong link to applied fields in its research questions and approaches (Flick, Citation2002). The common narrative of research participants was considered as its core data (Bryman, Citation2016).

3.1. Research tools

Preparatory desk research was conducted for the development of questioner (Annex-A). The interview guide was developed based on the results of IFOAM-adapted survey,Footnote1 conducted before designing the qualitative study. The interview guide was further enhanced from the review of literature (Cheong et al., Citation2019), and its validity was confirmed through the research team.

3.1.1. Data collection

The population of interest was organic food shoppers, both regular and occasional, and thus, purposive sampling was used to collect the data, the most widely used sampling methods in qualitative research (Cheong et al., Citation2019). It provided information-rich individuals, which deal with issues of central importance particularly in order to explore the insights in developing in-depth understanding (Patton, 2015). Twenty-eight respondents participated in the study representing housewives, salaried individuals, businessman, and self-employed individuals as depicted in . First 9 interviews were conducted as semi-structured interviews of 20–25 minutes where different questions and counter questions were asked; next three interviews were on the laddering technique, while remaining 16 interviews were structured of 10–15 minutes with specific questions in the same order and no counter questions were asked. These interviews were conducted in specific markets specialized in offering organic food products, i.e Nomad and Farmer markets in Islamabad and Khalis and Haryali markets in Lahore. It would not have been relevant to conduct interviews in all cities of Pakistan, where organic food companies were not operating and most consumers may not be familiar with the term “organic food”. During each interview, an active listening approach was employed where predetermined and emerging aspects were discussed. After taking consumer consent, all interviews were audio-recorded with a smartphone voice recorder (Cheong et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

Table 2. Various unique themes uncovered in the study

For all interviews, the framework for the questions began with questions about understanding and awareness about organic food and then, the reason for organic food consumption was explored. Remaining questions were related to trust, origin, price, availability etc. Finally, cross-questioning and discussion on emerging themes were conducted. However, the interviews through the laddering technique were started from general questions and preceded in accordance with consumer’s replies. The commonly proposed criterion in qualitative research is indeed “saturation” for determining the sufficient sample size (Charles et al., Citation2015; Charmaz & Smith, Citation2003 ; Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985; Merriam & Tisdell, Citation2015; Morse, Citation1995).

3.2. Analyses

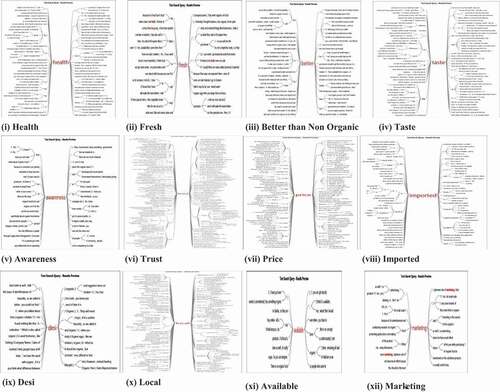

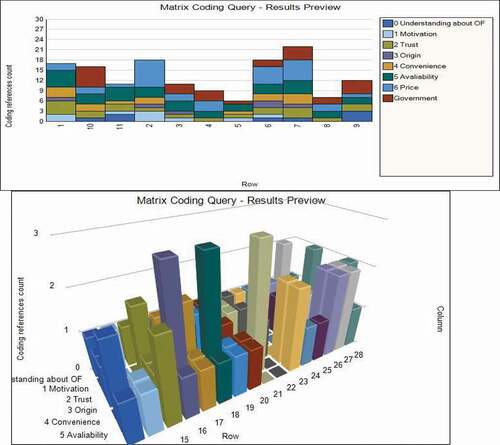

The interviews were conducted mixed, in Urdu and in English. However, all interviews were transcribed into English, which resulted in 23,655 words. All interviews were transcribed verbatim (Eaton et al., Citation2019). The transcription process was the focus of attention as it is always critical in data analysis and central in qualitative research (Mero-Jaffe, Citation2011). Since the researcher was interviewer an the transcriber in most of the interviews of present research, thereby, it reduced compromising influences with respect to the transcript quality (Mero-Jaffe, Citation2011). The coding was done by following a six-step process as suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2012). Narrative preparation was made in first step. Data were transcribed and properties and characteristics of the data were identified. Initial codes were generated in the second step wherein data were interpreted, organized, and structured. This was done line by line wherein conceptually similar responses were coded (Blair, Citation2015; Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990). In the third step, data were organized in accordance with codes. It follows themes identification and placing codes into potential themes. Afterward, themes were further reviewed and divided into subthemes to generate a thematic map for analysis. Themes were further refined to assign the label to each theme. Finally, findings were written with support of raw data (quotes) and interpretation was carried out through theoretical triangulation in order to report the noted phenomena. The use of software package, i.e Nvivo- 11 in qualitative research, was found useful since it helped to store, organize, and present enormous data and their analysis in an efficient way (Feng & Behar-Horenstein, Citation2019). It provided a holistic view and range of tools for exploring and understanding the pattern in data particularly to answer research questions of the study. The results of various queries such as word frequency (Table A1), text query (), word cloud (), and matrix coding () are placed at Appendix A.

Data were analyzed from detailed parts to categories, themes, dimensions, or codes. Thematic analysis was used for answering the research questions. Interpretation was carried out through theoretical triangulation in the light of various theories and concepts (Nielsen et al., Citation2020). In addition, a set of countercheck activities such as (i) checking interpretations against raw data and (ii) peer debriefing was also carried out as required to ensure validity of data.

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. Consumer understanding about organic food

The findings indicated that consumers had growing concerns over the “production methods” of food, mainly due to various food safety scandals. They perceived organic food as a food without chemical fertilizers and pesticides that grow in a natural way with clean water, healthy soil, and away from the polluted environment. A respondent while sharing his views informed that “I feel, organic food here, is without preservatives, additives, without chemical fertilizers and pesticides. They (growers) are providing it organic feed (inputs) in a natural way, and that’s why it is known as organic” (Respondent, 23).

A majority of respondents associate organic farming with characteristics such as natural food; free of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and adultery; not using the spray things; directly coming from the land; without any artificial means and modern methods; organic origin; real thing; without major agribusiness operations; and product of small local farmers. However, few respondents also told that being natural does not mean organic, as organic required many “strict regulations”. “Organic food is anything that has authorization; proper ingredients go into it, proper certification from competent authority. If you grow organic vegetables it has to be properly harvested so different products have different requirements” (Respondent, 13).

Some respondents reported their concerns that strict regulations of organic food production methods do not allow one to grow organic food in the surroundings of large cities due to the polluted environment. However, due to “limited options” for healthy food, they had to rely on naturally/self-declared organic products.

The above responses depict that organic food consumers have a general understanding about the characteristics of organic food, while some consumers also have specific information about production, processes, and certification methods. The consumer segment with good knowledge about organic food and their production methods can be termed as the “organic food awareness segment” (OFAS). Hence, we can argue that consumers were found motivated and willing to consume organic food mainly by virtue of their awareness especially about its production method. These findings are in contrast to those of Aschemann‐Witzel & Zielke, Citation2017; Padiya & Vala, Citation2012. The lack of awareness and understanding about organic farming methods can act as a barrier in developing attitude towards purchase of organic food. Therefore, the “dissemination of information” about the benefits of organic food and its production methods can further boost the organic food industry in developed and in developing countries.

Moreover, the majority of respondents revealed that they consume mostly vegetables, fruits, chicken, eggs, milk, and honey (perishable products). As far as “consumption percentage” of organic food was concerned, many consumers informed that they consume thirty percent organic food of total consumption, while few reported as much as forty percent. These findings refer to the cultural backdrop against which people orientate themselves on questions of what is good, valuable, admirable, and worthwhile (Schösler et al., Citation2013).

shows the results of google trend for the term organic in Pakistan from May 2016 to May 2021.

4.2. Motivation behind organic food consumption

The results indicate that organic food consumption appeared to be driven by “health motives”. “Your life is only as good as your body is; as much your body will be healthy so as much your life will be better” (Respondent, 11). And “I consume organic as it is considered to be healthier and it has long term health benefits” (Respondent, 15).

Health as an important motivator is also evident from Nvivo results (see Appendix A), wherein respondents have used the word health on numerous occasions. In text query, Figure A1 of Appendix A, health can be observed as a key influencer in purchase of organic food. The health motives explored in the present study are further divided into “three subcategories”. For instance, (i) to improve their health and capacity, (ii) for health recovery from illness or disease for themselves or for family members, and (iii) to avoid any future health issues, they should think that “prevention is better than cure”.

The influence of “pro-environmental” factors and “localized raw food” to support local economy and people for “socio-economic benefits” (altruistic motives) were also noted as secondary motive, however, with a relatively less extent as compared to other motives. Some consumers revealed that they support local food particularly to promote organic growers, so to ensure “availability” of organic food in the future. However, promoting local farmers to ensure future availability is also unique finding as compared to previous studies (see Costa et al., Citation2014; Hamzaoui Essoussi & Zahaf, Citation2009; Naspetti et al., Citation2011; Padel et al., Citation2005; Schösler et al., Citation2013).

Findings indicate that the consumer attitude of organic food purchase in Pakistan is relatively less influenced by “altruistic values” and based on self-interest and private use values instead of public use value. The findings support the results of Magnusson et al. (Citation2003) that egoistic motives are better predictors of the purchase of organic foods than are altruistic motives.

It is pertinent to mentioned that some “activist consumers” were also found in the consumption of organic food, particularly in order to discourage large food corporations, MNCs and capitalism, which endorsed the findings of Hamzaoui Essoussi & Zahaf, Citation2009. A consumer described the slow food movementFootnote2 and asserted that “the organic is not like fashion or something, if it is taken to be serious, actually, it is opposition to food as produced nowadays” (Respondent, 7).

4.3. Trust

Trust was noted as a most relevant factor in purchase of organic food since, in the absence of regulations, certification and labelling, it was a matter of curiosity that how consumers purchase organic food in Pakistan. The characteristics of organic food are credence in nature. It is not easy to distinguish between organic and nonorganic food mainly prior to purchase. “We have to go by trust, whatever they are saying (standing in the company outlet), if there will be no trust then how can we proceed” (Respondent, 1).

In addition, following subthemes of trust were explored during interviews: (a) Trust through word of mouth, (b) Trust on market organizers and point of purchase, (c) Trust on the sales person, (d) Trust through test and trial, (e) The organic cues as a source of trust, and (f) Trust through traceability of food.

4.4. Trust through word of mouth

Consumers usually share their views, feedback, opinions, experiences, and disagreement within and across social groups. This phenomenon develops perception, understanding, and preferences of consumers about organic food products and their companies from different sources.

“In my known people, I always tell them to go to this place (farmer market) twice a week and buy (organic food) from there. I believe myself that this one is a good spot. If it is good for me, I am sure it will be good for my friends and for relatives”. (Respondent, 10)

Another respondent told that “I think those people consume, they tell that which person is reliable, while, here, in the open market it is difficult to judge” (Respondent, 15). And “So whatever is available in the market, we ask each other what you think is more worse?” (Respondent, 8)

Thus, Word of Mouth (WoM) plays an important role in consumer perception and overall evaluation of the products, markets, and companies/vendors. It can be considered as one of the key drivers towards trust and ultimately in a purchase decision of organic food in non-regulated markets of Pakistan. Hughner et al. (Citation2007) also identified word of mouth as an important source of information for organic food consumers.

4.5. Trust through market organizers

Some consumers have developed their trust in organizers of organic food markets. They believe that organizers have selected and allowed the vendors after proper monitoring and scrutiny to ensure that their products are in accordance with organic principles. “The people who run the market also screened it, many of them go and see the places of farming, so, I take it on the basis of what they say to me” (Respondent, 11).

Adding to this criterion, another respondent shared his views that “In organic market, business people (organic dealers) participate usually through contacts, and they are people having their own farms, lands and organic business; as we believe that organic food market organizers verify for us, about their organic food products and whatever they selling, that its right product” (Respondent, 4). It is worth mentioning that trust in organic food organizers is found as a unique theme, which was not reported in previous studies.

5. Trust on sales person and point of purchase

In the absence of certification and organic food labelling, sales person’s words, stories, statements, and even their appearances were also found to be a noteworthy source of trust for consumers. “Yeah, I have to trust, if he (sales person) is telling me, even if he has not labelled and told me about the ingredients in it” (Respondent, 1).

Another participant talking about trust also told that “We judge it by looking at face of the person (laughing) as he seems honest and in Pakistan this can be only criteria, but there should be some authority, there should be laboratory, some health inspector to check, there must be certification and due to certification there would be more sales”. (Respondent, 5).

Similarly, a respondent said that “You can tell when you talk to the person (sales person), they are immature and usually not much professional, I trust the words” (Respondent, 2).

5.1. Role of the sales person

Moreover, it was found that some consumers associate organic food products more with traditions and week business orientation. They expect that being cost-effective, small growers should not involve in business and marketing practices to capture mass markets that may detract them from basic principles of organic production and ethical practices. In other words, for some consumers, business orientation and scale of production are considered as destructive to trust measures.

Moreover, if the grower himself is selling the products in the market, it captures more attention and trust for consumers. Hemmerling et al. (Citation2015) also endorsed the findings of Aguirre Gonzalez, (Citation2009) that knowing the farmer and confidence in the vendor can be considered as an important factor in purchase of organic food products.

5.2. Trust through test and trial

Another important parameter of developing trust was “trying the product” as “its trial and tested process which builds our trust”. We try it and then we see what suits us” (Respondent, 17). This factor was also revealed by a number of respondents, and findings are similar to Moore (Citation2006). Although organic food is a credence, however, some knowledgeable consumers by virtue of their technical expertise in specific products can find the differences by taste.

5.3. Organic cues as a source of trust

In the absence of any technical identification and expertise, organic cues were found to be the most substantial and concluding trust parameter that elicits changes in consumer preferences. The “region cue” of products was found as an important determinant of trust. Indeed, in the light of cue model (Harvard, Citation2001), one can argue that region cue is complementary with organic consumption since that cue has been associated with consumption due to certain information about some specific areas. Most organic food products if supplied from particular areas were considered naturally organic due to the environment, development level, and agriculture practices in those regions. In most of the countryside and northern areas, small farmers could not afford costly inputs, while some species naturally did not require any artificial inputs. “About Gilgit and surroundings is that I know their environment is neat and clean and those people are at far (distance) so maybe they don’t use as much pesticides. That’s what I go (prefer) for it” (Respondent, 3). Likewise, a participant informed that “His (sales person) appearance and representative attitudes tell you that he is an organic sales person as we are familiar with People of Hunza (village) and they sell local organic things” (Respondent, 7).

When asked by a consumer, how do you believe that honey is organic? He replied robustly “Because I know the valley (Chitral), they don’t use chemical fertilizers and pesticides they have fresh water from lake, that is, from where the honey is coming from and in those areas there is a lot of organic farming, those remote areas are not accessible to commercial markets (for selling chemical fertilizers & pesticides) so they don’t have such practice” (Respondent, 12). The origin/ region as a source of trust for organic food is also discussed by Radman, Citation2005 and Hemmerling et al., Citation2015.

Many consumers also ensure their trust through “traceability” of products by visiting farms, lands, and cultivated areas of producers. “There is no certification but I actually go to their farm to see this” (Respondent,10). Another respondent while talking about trust told that “My trust level is that one should determine from where you are picking (cultivating) the food, I am talking about locally produced not imported” (Respondent, 19) and “For trust we can see their places (farm for traceability)” (Respondent, 21).

Appearance, size, smell, and quantity of organic products were also found as major cues, and these findings are similar to Eden et al., Citation2008a; Hamzaoui Essoussi & Zahaf, Citation2009; Hemmerling et al., Citation2015.

Many consumers were found to be reluctant in purchasing products with high-scale quantity, and they stated that organic could not be in higher quantity and in bigger size. However, in a general context, where consumers have always trust deficit due to various reasons, consequently, the cue model for identification can be applied to determine the credibility of organic certification and brands. “There is no certification so we trust from the size, because organic is smaller in all types while inorganic has a larger size that is a rough sort of indication, which is also called DESI” (Respondent, 16).

5.4. The impact of country of origin on organic food purchase

The country of origin (COO) and its impact on purchase intention are capturing interests of scholars, policymakers, and export ventures of organic food. This section reports consumer preferences towards various product categories in contrast to the influence of COO. “Imported, I will only buy it if I could not get local products. If all locales are available, rice, wheat then I would not buy imported product” (Respondent, 7). Another consumer told “I don’t think so origin matter either local or imported” (Respondent, 20).

Nvivo results also show the prominent presence of terms like “local, origin and Hunza,” which shows impact of ethnocentrisms in purchase of organic food. For instance, consumers repeatedly use the word local and origin on one hundred one and forty-one occasions, respectively, as shown in the word frequency table (Appendix A). Similarly, text query, word cloud, and matrix coding also depict similar results.

A consumer shared his viewpoint that the reason for local preference is that both plants and humans are grown in a similar environment and ecology consequently local organic would be more suitable with more compatibility for local people due to similar body and ecological conditions. More specifically, many similar responses show that consumers actually consider perishable products, i.e. vegetables and fruits, when talking about organic, which is why they prefer local products due to its freshness, taste, shelf life, and ecological compatibility.

However, for value-added certified and noncertified organic, consumers also preferred imported products and they were also available at large stores and specialized organic stores, i.e go organic, necos, haryali store, organic shop, and many other likewise stores in metropolitan cities are offering organic products. Nvivo results also reports the term “imported” on fifty occasions by respondents having the strong presence in word query, word cloud, and matrix coding.

5.5. Price as a purchase barrier

The role of price in the consumer decision process has always been a field of interest for scholars generally and for food products particularly for organic food products. A respondent pointed out that “There is a huge price difference as compared to normal products” (Respondent, 4). In some cases, price acts as a trust indicator for quality, i.e if food has organic cues and it is presented in a reasonable way, then premium price will contribute positively to influencing prospective consumers. Price of organic food in Pakistan is indeed defined by its right presentation in the right market instead of its cost. “That depends, if I am not getting good quality stuff where I live then obviously I will prefer that I would pay more and get better stuff” (Respondent, 26). Due to the lack of competition in the organic food segment, especially the absence of large food corporations and availability of certified imported organic products for the mass market, the organic is overpriced in Pakistan. Even some companies are charging hundred percent premium prices on certain products as a price skimming strategy. “I think the price is high, but it is due to lack of competition” (Case 20).

Similarly, another respondent revealed that “Basically, its (purchase) depends on product to product, if the absolute price of the product is low, for example, daily consumption products like eggs, tomatoes, such type of regular used products, as they have more consumption, so paying ‘double price’ for these regular products actually increase total expense massively” (Respondent, 4).

Hence, shoppers could consider it as a “price insensitivity” for a reasonable premium (up to 25%) has low price elasticity of demand in the organic food awareness segment (OFAS). The majority of older people and regular consumers were found to be more price insensitive. Reasonable premium price up to 25 percent was not considered as a barrier for organic food purchases, and even without certification, most consumers were willing to purchase. Indeed, intention to pay a premium price was actually based on the quality of the product, its presentation, image of the company, and point of purchase. As there was a lack of price alternatives or price evaluation mechanism, so consumers compare prices with nonorganic products. Consumers believe that to promote organic food and to obtain organic products in the future, they have to pay a premium price for survival and sustainability of the organic food chain members.

Moreover, some consumers have also reported that many species of organic products have been sometimes difficult to cook as it takes more time to prepare. Notable products mentioned in this regard were organic chicken, black grams (chickpea), wheat flour, and few pulses.

5.6. Impact of marketing practices on organic food consumption

The results revealed that labels, branding, and marketing practices can play vital roles in consumer awareness and ultimately for purchase of organic food for a specific consumer segment. It stimulates the consumer demand with positive perception, especially, the way information is delivered about organic food products. “Since when it (Haryali market/event marketing) has started, it has increased (organic consumption) a lot, more than 60 percent” (Respondent, 23).

For some consumers, marketing also worked as a quality cue and they believe that companies must be focusing on marketing after ensuring their quality standards for organic products in order to create value. “The big point is that when you remove the origin (from product) then you need a label on it” & “we also consumed some organic product by Daali (Brand) because we have some value for money also” (Respondent, 6)

However, branded organic products by SMEs labelled as organic were also found to be alternative to organic certification since consumers show their trust towards certain brands. “There is no certification, so we go to name, brand name. We don’t have any other option, we can’t check how they have done this or not done” (Respondent, 18). Therefore, marketing was also identified as an important component of the organic food segment as it spread awareness and provided a competitive edge with differentiation from non-organic products.

On the contrary, the discussion also indicates that some traditional and activist consumers do not prefer the presence of marketing in organic food promotion, since it may increase the demand of organic food, while growers or supply chain members may not comply with production principles in order to meet the demand. There was also an important perspective that marketing practices made the organic food products less trustworthy as it depicts organic as a marketing tool.

However, to compete with conventional food industry practices and in contrast to marketing of organic food in developed organic food markets, there is no doubt that sustainability and development of organic food businesses are not possible without cost-effective marketing practices. However, most organic food private brands also carried out BTL activities, mainly focused on event management and social media marketing to promote their products.

In addition, deceptive marketing practices and sometimes food scam that refrain consumers from participating in organic purchasing were also found as one of the major barriers in purchase of organic food. When asked to respondent that why do you not purchase organic food products for all product types? She replied, “I think it’s a scam sometimes”. (Respondent, 2).

Moreover, some consumers have also reported that many species of organic food had been difficult to cook as it takes more time in preparing as compared to conventional. Notable products mentioned in this regard were organic chicken, black grams (chickpea), wheat flour, and few pulses, while few vegetables take more effort in peeling, i.e ginger and garlic.

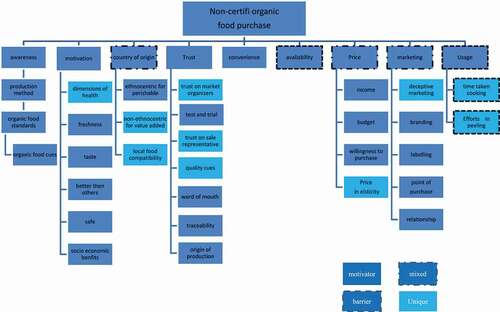

The extracted model of the study is presented in , which illustrates all factors in hierarchical form that influence the purchase of non-certified organic food in non-regulated markets of Pakistan.

6. Conclusion

The findings of the present study have revealed several patterns and themes that depict consumer awareness level, preferences, and barriers during purchase of organic food. The results clearly demonstrate that organic food shoppers have a good understanding about its benefits by virtue of their production methods. Our results confirm that food safety and health issues are main motivators and these choices are mainly driven by personal motives. Consumer concerns towards sustainability, environment, and benefits to society are at secondary priorities. These findings are an exploratory effort that contributes tounderstanding the cultural context of non-certified organic food consumption and it can be considered a unique contribution to the theory of food philosophy in this context.

In addition, due to credence in nature, it is not easy to develop trust on organic food products since they are sold on self-declaration instead of being certified. The study further explores that trust and its several dimensions play vital roles in shaping consumer decisions. In addition, due to inadequate organic certification and labelling, consumers made judgment based on different cues.

The unique themes reported in this study include three subcategories of health motives: various dimensions of trust especially trust on market organizers and organic food cues; role of sales person; price as a quality cue; marketing practices reduced the trust worthiness for specific consumer segment; and local food is perceived for compatible with local people ecologically, however, consumer prefer value-added imported organic food. Furthermore, deceptive marketing and various types of organic food perceived difficult to peel and cook and also act as a barrier.

Many consumers reported their concerns that due to lack of competition, organic products are overpriced. Similar to previous studies, price is also found as a important factor; however, some group of consumers were found to be price elastic (young, marketing oriented, and trendy), while others were found inelastic (aged, activist, amd individualistic). Likewise, insufficient availability was also found as a barrier in developing an organic food market. Although there is huge natural production of organic food in various parts of the country, however, it is not channelized at the mass level and there is a supply chain gap, which makes lack of availability in mainstream market a regular option for consumers. Consumers prefer local organic products, i.e vegetables, fruits, milk, etc. due to perishability, taste, and freshness. In the light of consumer responses towards imported organic food particularly due to certification, the consumers could not be declared as ethnocentric.

The organic consumer can be categorized into several groups, i.e activist (environmental, societal, and anti-capitalists), Individualist (health conscious, taste, and food safety), trendy (fashion, experimental, and outing), anti-marketing (quantity against quality), marketing oriented consumers (believe on mass customization as success of product and as quality cue), and no-choice consumer (who purchased non-certified organic food due to non-availability of certified organic food).

The developed consumer decision map based on the research findings as shown in is a theoretical contribution of the present study that depicts how consumers purchase non-certified organic food and what factors play a vital role in this regard.

7. Practical implications

This paper provides useful insights for managers, policy executives, and academicians. The organic food sector is an untapped food segment in Pakistan. Increasing consumer demand could develop vital prospects for young entrepreneurs, SMEs, large corporations, and MNC in this segment. While marketing organic food products, managers should focus on its health benefits, safety features, taste, and shelf life. Highlighting local origin for non-value added products can increase interest of consumers. For enhancing trust, the organic food should be promoted in credible markets where organizers of the markets/sales point can assure its quality. Moreover, sales representatives should be well informed and better if they belong to naturally organic regions, i.e Gilgit Baltistan, Kashmir, etc. Enterprises and vendors should offer products on a trial basis so consumers can experience the difference between organic and non-organic after trials. Organic food products should have at least private labels that contain necessary information like conventional products. Most importantly, organic products should be available through multi-dimensional channels, i.e online, farmer markets, and specialized stores through consortium of small vendors so prospective consumers can access with convenience.

The policy intervention towards organic food regulations, particularly subsidized certification, can be crucial in the development of the organic food industry and promoting sustainable products for the well-being of consumers and other agriculture stakeholders. Moreover, consumer purchase-power and their increasing preferences for imported certified organic food products are also opening new avenues for importers and foreign brands to capture this untabbed market as a blue sea segment. Indeed, in the context of organic food, it can be named as the green sea to capture South Asian and European markets through its cultivation and production in Pakistan. Contract and corporate farming can also create opportunities for local communities and SMEs to learn organic food systems, which may help in developing domestic markets through “diffusion of innovation” and as a win-win sustainable strategy for all stakeholders. Such agriculture ventures in organic farming can also contribute to rural development of under-developed countries like Pakistan. Willer et al. (Citation2018) reports that 179 countries have organic practices, wherein 87 are operating through proper organic regulations. Thus, findings can have vital implications for other 92 countries operating without organic food regulations and where organic food is sold without certification.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hasan Ali Mughal

I am a founder of Pakistan Organic Association (www.pakorganic.org), which has 200 plus members from all over Pakistan.

At present, I am serving as a asst. professor (visiting) in various public sector Universities. Previously, I served as a lecturer at Lahore Business School, University of Lahore. I was awarded IRSIP,HEC PhD fellowship to Aarhus University, Denmark, where I also worked as a research associate on project with Professor John Thogersen.

Before starting my PhD, I worked as an Admin/marketing Officer at one of the prestigious institutes of Pakistan, i.e NDU for five years from 2010–2015;

Before Government job, I worked in the banking sector from 2004–2009.

As far as education background is concerned,

I have recently obtained my PhD in the field of Organic Food marketing and supply chain.

Previously, I did MPhil in export marketing and MBA in marketing.

I did BSc in statistics and Economics in 2003.

My research interest are Marketing and supply chain, public policy, consumer behavior and export marketing.

Notes

2. For more details, http://www.navdanya.org/organic-movement/organic-production.

References

- Acebrón, L. B., & Dopico, D. C. (2000). The importance of intrinsic and extrinsic cues to expected and experienced quality: An empirical application for beef. Food Quality and Preference, 11(3), 229–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-3293(99)00059-2

- Aguirre Gonzalez, J. A. (2009). Market trends and consumer profile at the organic farmers market in Costa Rica. British Food Journal, 111(5), 498–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700910957320

- Akbar, A., Ali, S., Ahmad, M. A., Akbar, M., & Danish, M. (2019). Understanding the antecedents of organic food consumption in Pakistan: Moderating role of food neophobia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 4043.

- Al-Swidi, A., Mohammed Rafiul Huque, S., Haroon Hafeez, M., & Noor Mohd Shariff, M. (2014). The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. British Food Journal, 116(10), 1561–1580. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2013-0105

- Andersen, P. H., & Kragh, H. (2010). Sense and sensibility: Two approaches for using existing theory in theory-building qualitative research. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2009.02.008

- Aryal, K. P., Chaudhary, P., Pandit, S., & Sharma, G. (2009). Consumers’ willingness to pay fCharlesor organic products: A case from Kathmandu valley. Journal of Agriculture and Environment, 10, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.3126/aej.v10i0.2126

- Aschemann‐Witzel, J., & Zielke, S. (2017). Can’t buy me green? A review of consumer perceptions of and behavior toward the price of organic food. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 51(1), 211–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12092

- Asif, M., Xuhui, W., Nasiri, A., & Ayyub, S. (2017, September). Determinant factors influencing organic food purchase intention and the moderating role of awareness: A comparative analysis. Food Quality and Preference, 63, 144–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.08.006 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0950329317301921

- Blair, E. (2015). A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 6(1), 14–29.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology: Vol. 2. Research designs (pp. 57–91). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Charles, S. J., Ploeg, C., & Mckibbon, J. A. (2015). The qualitative report sampling in qualitative research: Insights from an overview of the methods literature. The Qualitative Report, 20(11), 1772.

- Charmaz, K., & Smith, J. A. (2003). Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (J. A. Smith, Ed.) (p. 81).

- Chen, W. (2013). The effects of different types of trust on consumer perceptions of food safety. China Agricultural Economic Review, 51, 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/17561371311294757

- Cheong, H. J., Mohammed-Baksh, S., & Wright, L. T. (2019). US consumer m-commerce involvement: Using in-depth interviews to propose an acceptance model of shopping apps-based m-commerce. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1674077. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1674077

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21.

- Costa, S., Zepeda, L., & Sirieix, L. (2014). Exploring the social value of organic food : A qualitative study in France. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(3), 228–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12100

- Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L., Gutmann, M. L., & Hanson, W. E. (2003). Advanced mixed methods research designs. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, 209, 240.

- Eaton, K., Stritzke, W. G., & Ohan, J. L. (2019). Using scribes in qualitative research as an alternative to transcription. The Qualitative Report, 24(3), 586–605. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol24/iss3/12/

- Eden, S., Bear, C., & Walker, G. (2008a). Mucky carrots and other proxies: Problematising the knowledge-fix for sustainable and ethical consumption. Geoforum, 39(2), 1044–1057. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.11.001

- Feng, X., & Behar-Horenstein, L. (2019). Maximizing NVivo utilities to analyze open-ended responses. The Qualitative Report, 24(3), 563–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx052

- Flick, U. (2002). Qualitative research-state of the art. Social Science Information, 41(1), 5–24.

- Freyer, B., & Bingen, R. J. (2015). Re-thinking organic food and farming in a changing world. Springer.

- George, G., Haas, M. R., & Pentland, A. (2014). Big data and management. Academy of Management, 57(2), 321–326.

- Giampietri, E., et al. (2018). A theory of planned behaviour perspective for investigating the role of trust in consumer purchasing decision related to short food supply chains. Food Quality and Preference. Elsevier, 64(June), 160–166.

- Gumber, G., Rana, J., & McMillan, D. (2021). Who buys organic food? Understanding different types of consumers. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1935084. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1935084

- Hamzaoui Essoussi, L., & Zahaf, M. (2009). Exploring the decision-making process of Canadian organic food consumers: Motivations and trust issues. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 12(4), 443–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750910993347

- Hamzaoui-Essoussi, L., Sirieix, L., & Zahaf, M. (2013). Trust orientations in the organic food distribution channels: A comparative study of the Canadian and French markets. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(3), 292–301. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.02.002

- Harvard, T. (2001). A Cue-Theory of Consumption. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 81–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/003355301556356

- Hasimu, H., Marchesini, S., & Canavari, M. (2017). A concept mapping study on organic food consumers in Shanghai, China. Appetite, 108, 191–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.09.019

- Hemmerling, S., Hamm, U., & Spiller, A. (2015). Consumption behaviour regarding organic food from a marketing perspective—a literature review. Organic Agriculture, 5(4), 277–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-015-0109-3

- Holloway, I., & Todres, L. (2003). The status of method: Flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qualitative Research, 3(3), 345–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794103033004

- Hsu, S. Y., Chang, C. C., & Lin, T. T. (2016). An analysis of purchase intentions toward organic food on health consciousness and food safety with/under structural equation modeling. British Food Journal, 118(1), 200–216.

- Hughner, R. S., McDonagh, P., Prothero, A., Shultz, C. J., & Stanton, J. (2007). Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 6(2‐3), 94–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.210

- Juhl, H. J., Fenger, M. H., & Thøgersen, J. (2017). Will the consistent organic food consumer step forward? an empirical analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(3), 519–535. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx052

- Liang, R.-D. (2016). Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: the moderating effects of organic food prices. British Food Journal, 118(1), 183–199.

- Lim, J. H. (2011). Qualitative methods in adult development and learning: Theoretical traditions, current practices, and emerging horizons. In C. Hoare (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of reciprocal adult development and learning (2nd ed., pp. 39–60). Oxford University Press.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Ling, C. Y. (2013). Consumers’ purchase intention of green products: An investigation of the drivers and moderating variable. Elixir Marketing Mgmt. 5, 57(A), 14503–14509.

- Magnusson, M. K., Arvola, A., Hursti, U.-K. K., Åberg, L., & Sjödén, P.-O. (2003). Choice of organic foods is related to perceived consequences for human health and to environmentally friendly behaviour. Appetite, 40(2), 109–117.

- Mangan, T., Shah, A. R., Laghari, N., & Nangraj, G. M. (2016). Level of awareness and willingness to pay for organic. Science International, Lahore, 28(4), 4013–4017. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2018.1449697

- Massey, M., O’Cass, A., & Otahal, P. (2018). A meta-analytic study of the factors driving the purchase of organic food. Appetite, 125, 418–427. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.029

- Memon, A. (2013) Pakistan has favourable climate for production of organic dates Quantity: Tonnes. https://www.foodjournal.pk/2015/Jan-Feb-2015/PDF-Jan-Feb-2015/Exclusive-article-on-dates-Dr-Noor.pdf

- Mero-Jaffe, I. (2011). ‘Is that what I said?’Interview transcript approval by participants: An aspect of ethics in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(3), 231–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691101000304

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Revised and Expanded from” Case Study Research in Education”. Jossey-Bass Publishers, 350 Sansome St 94104.

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons

- Moore, O. (2006). Understanding post organic fresh fruit and vegetable consumers at participatory farmers’ markets in Ireland: Reflexivity, trust and social movements. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(5), 416–426.

- Mørk, T., Bech-Larsen, T., Grunert, K. G., & Tsalis, G. (2017). Determinants of citizen acceptance of environmental policy regulating consumption in public settings: Organic food in public institutions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 148, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.139

- Morse, J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation.

- Musa, M., Bokhtiar, S., & Gurung, T. (2015). Status and future prospect of organic agriculture for safe food security in SAARC countries. SAARC Agriculture Centre. www.sac.org.bd/archives/publications/Organic%20Agriculture.pdf

- Naspetti, S., Lampkin, N., Nicolas, P., Stolze, M., & Zanoli, R. (2011). Organic supply chain collaboration: A case study in eight EU countries. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 17(2–3), 141–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2011.548733

- Nielsen, B. B., Welch, C., Chidlow, A., Miller, S. R., Aguzzoli, R., Gardner, E., Karafyllia, M., & Pegoraro, D. (2020). Fifty years of methodological trends in JIBS: Why future IB research needs more triangulation. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(9), 1478–1499. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00372-4

- Nuttavuthisit, K., & Thøgersen, J. (2017). The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(2), 323–337.

- Olsen, M. C., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Chandukala, S. R. (2014). Green claims and message frames: How green new products change brand attitude. Journal of Marketing, 78(5), 119–137.

- Pacho, F. (2020, June). What influences consumers to purchase organic food in developing countries ? British Food Journal, 122(12), 3695–3709. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-01-2020-0075

- Padel, S., Foster, C., & McEachern, M. (2005). Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour: Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. British Food Journal, 107(8), 606–625. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700510611002

- Padiya, J., & Vala, N. (2012). Profiling of organic food buyers in Ahmedabad city: An empirical study. Pacific Business Review International, 5(1), 19–26. http://www.pbr.co.in/2012/2012_month/Jul_Sep/3.pdf

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283.

- Paul, J., & Rana, J. (2012). Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(6).

- Pedersen, S., Aschemann-Witzel, J., & Thøgersen, J. (2018). Consumers’ evaluation of imported organic food products: The role of geographical distance. Appetite, 130, 134–145.

- Poerting, J. (2015). The emergence of certified organic agriculture in Pakistan—Actor dynamics, knowledge production, and consumer demand. ASIEN, 134, 143–165. http://asien.asienforschung.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2015/02/ASIEN_134_Poerting_Abstract.pdf

- Prothero, A., Dobscha, S., Freund, J., Kilbourne, W. E., Luchs, M. G., Ozanne, L. K., & Thøgersen, J. (2011). Sustainable consumption: Opportunities for consumer research and public policy. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 30(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.30.1.31

- Radman, M. (2005). Consumer consumption and perception of organic products in Croatia. British Food Journal, 107(4), 263–273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700510589530

- Rahman, K. M., & Noor, N. A. M. (2016). Exploring organic food purchase intention in Bangladesh: An evaluation by using the theory of planned behavior. International Business Management, 10(18), 4292–4300. http://repo.uum.edu.my/20732/

- Rana, J., & Paul, J. (2017). Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 38(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.06.004

- Rizzo, G., Borrello, M., Dara Guccione, G., Schifani, G., & Cembalo, L. (2020). Organic food consumption: The relevance of the health attribute. Sustainability, 12(2), 595. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020595

- Rödiger, M., & Hamm, U. (2015). How are organic food prices affecting consumer behaviour? A review. Food Quality and Preference, 43, 10–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.02.002

- Sarfraz, M., & Abdullah, M. I. (2014). Buying of Organic Food in Multan (Pakistan): A case study of consumer’s perceptions. International Journal of Economics and Empirical Research, 2(2014), 288–293. https://ideas.repec.org/a/ijr/journl/v2y2014i7p288-293.html

- Schösler, H., De Boer, J., & Boersema, J. J. (2013). The organic food philosophy: A qualitative exploration of the practices, values, and beliefs of Dutch organic consumers within a cultural-historical frame. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 26(2), 439–460. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-012-9392-0

- Thøgersen, J., & Crompton, T. (2009). Simple and painless? The limitations of spillover in environmental campaigning. Journal of Consumer Policy, 32(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-009-9101-1

- Thøgersen, J., de Barcellos, M. D., Perin, M. G., & Zhou, Y. (2015). Consumer buying motives and attitudes towards organic food in two emerging markets. International Marketing Review, 32(3/4), 389–413. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-06-2013-0123

- Vigar, V., Myers, S., Oliver, C., Arellano, J., Robinson, S., & Leifert, C. (2020). A systematic review of organic versus conventional food consumption: Is there a measurable benefit on human health? Nutrients, 12(1), 7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010007

- Vittersø, G., & Tangeland, T. (2015). The role of consumers in transitions towards sustainable food consumption. The case of organic food in Norway. Journal of Cleaner Production, 92, 91–99. Elsevier. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.055

- Willer, H., Lernoud, J., & Kemper, L. (2018). The world of organic agriculture 2018: Summary. In The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2018 (pp. 22–31). Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL and IFOAM-Organics International.

- Willer, H., Lernoud, J., & Kilcher, L. (2018). The world of organic agriculture: Statistics and emerging trends 2014: Frick. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) & Bonn: International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM).

- Yadav, R., & Pathak, G. S. (2016). Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 732–739.

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. The Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

Annex-A

University Institute of Management Sciences

PMAS, University of Arid Agriculture, Rawalpindi

Organic Consumer Interview

Section I

Section II—Respondent Demographics

Appendix A

Nvivo—Results

Table A1 Word Frequency of the Study