Abstract

A perusal of the literature shows that a broad frame of references for organizational success is not adequately developed. Therefore, by taking an interdisciplinary approach with a relational perspective, this study takes an integrative and fresh approach toward illuminating the moderate role of competitive strategy in realizing the potential influence of supply chain management (SCM) practices on organizational performance of the manufacture organizations. Using the gathered data of 157 manufacturing organizations that operate in Kosovo, this study boosts the margins of the existing literature. The findings indicate a positive influence of SCM practices and competitive strategy on organizational performance. In addition, the findings also show that competitive strategy moderate the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance. It highlights that differentiation strategy is necessary to increase the actual value of SCM practices and makes the organization flourish.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The trend of the business environment is changing fast and current market solidity may suddenly turn to uncertainty in the near future. In an unpredictable market, competitive intensity changes occasionally. Organizations continuously try to increase their competitive power to beat their rivals in order to reap the benefits of gaining the title of the last survivor and market leader. To cope with this tremendous uncertainty, the highest in the history of mankind, organizations must be prepared to respond to unanticipated changes. Thus, they must always be prepared to act with appropriate resources and capabilities on hand for the next rounds of the fight. For that reason, by taking an interdisciplinary approach with a relational perspective, this study takes an integrative and fresh approach toward illuminating the role of competitive strategy in realizing the potential influence of supply chain management practices on organizational performance.

1. Introduction

In an unpredictable market, competitive intensity changes occasionally. To cope with this tremendous uncertainty, the highest in the history of mankind, organizations must be prepared to respond to unanticipated changes. They must always be prepared to act with appropriate resources and capabilities on hand for the next rounds of the fight. The turbulent waters of international competition of the last few decades have abated concerns over whether internal, external or industrial factors are more vital to creating, capturing and sustaining a competitive advantage and organizational success. In this vein, David and David (Citation2017) highlight that an effective integration of both internal and external factors is crucial to achieving and maintaining a competitive advantage. Thus, researchers are currently focused on testing the relationship between strategic instruments and measuring the effect of an integrative strategic model on oranizational performance, which has opened a new window for future investigations (Islami, Citation2021b). For instance, insights into specific aspects of SCM are offered on industrial organization theory, associated transaction cost theory (Miles, Citation2012), and competitive strategies theory (Adăscăliței & Guga, Citation2018). Despite the increased attention paid to SCM the literature does not offer much evidence of successful implementations (Li et al., Citation2006).

Because of a lack of a unifying conceptual framework, it can be said, with reason that much remains unknown about how and when SCM practices resulting from inter-organizational relationships and competitive strategy can provide an improvement to organizational performance. Hence, the presence of an integrated three-dimensional strategic model, incorporating upstream and downstream sides of SCM practices, dimensions of competitive strategies and linking such activities to organizational performance, detracts from the usefulness of the application of previous results on operational and strategic management.

It is worth mentioning that, several authors highlighted the importance of building this kind of integrative model. For example, Qi et al. (Citation2011) claim that the influence of the SC strategy in practice and the method in which organizations build capabilities to support their strategies over time are yet to be fully explored. Therefore, more work is needed to further explore the impact of SCM practices on performance by including other areas of the organization and their perspective (K.C. Tan et al., Citation2002). Furthermore, Huo et al. (Citation2014) claim that the effects of contextual factors on competitive strategies, SC integration practices, company performance and the relationships between them, need to be developed further. Lastly, Kumar et al. (Citation2020) require testing a moderation effect of the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance.

To address these concerns, this study aims is to examine, understand and develop the relationship between two strategic instruments, that is, SCM practices and competitive strategy, as well as their direct and contingency effect on organizational performance. In this respect, through fine-grained analysis of the literature and by taking the perceptions of the high or mid-level managers of the manufacturing organizations that have a complete view of the organization’s strategy and functioning. This study presents three levels of management: firstly, it develops and clarifies SCM practices and their effect on organizational performance; secondly, it clarifies competitive strategy dimensions and their effect on organizational performance; and thirdly, it finds the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance, moderated by competitive strategy.

2. Theory informing our study

Organizations cannot operate efficiently if they are isolated from their suppliers and other supply chain units, so they should go beyond their boundaries in order to be successful in a competitive market. The role of SCM in improving organizational performance is clear, given that “today, firms view supply chain management as a strategic tool to increase their competitive advantage” (Qrunfleh & Tarafdar, Citation2013, p. 571). Overall, SCM definitions, in essence, have the same meaning, that is, they try to describe organizations as an integrated process that involves activities or operations in the distribution channels from suppliers to the final consumer. Thus, SCM becomes increasingly important as firms started to recognize that SCM is the main factor to create a sustainable competitive advantage for their business in an increasingly crowded and fierce environment especially in the digital era nowadays (Kitchot et al., Citation2020).

2.1. Supply chain management practices development

Upstream and downstream dimensions of the SC have been treated in different studies in order to define SCM. For instance, Li et al. (Citation2006) represent SCM by five practices: customer relationship, strategic supplier partnership, level of information sharing, postponement and quality of information sharing. Talib et al. (Citation2011) by six practices: strategic supplier partnership, material management, customer relationship, information and communication technologies, close supplier partnership and corporate culture. Bimha et al. (Citation2019) reviewed the main SCM practices, such as: logistics, management of procurement, information and communications technology, inventory and customer service in tandem with other SCM associated notions, such as: SC integration, SC collaboration, customer relationship management and supplier relationship management.

In the present study, the boundaries of SCM are defined including the most important and applicable practices: strategic supplier partnership, customer relationship, information sharing, lean manufacturing and postponement strategy, which fit with other variables explored in this study (Islami, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). These five practices cover four dimensions of the SC: upstream and downstream sides of the SC, information flow through the SC, and internal SC processes.

Strategic supplier partnership means creating an alliance between two or more organizations to facilitate each other in essential areas, such as: research, marketing, product manufacturing and distribution, is an important way to manage the SC (Khan & Siddiqui, Citation2018). It is about building better relationships with the selected strategic suppliers by which all members of the SC may benefit (Jacobs & Chase, Citation2014). A strategic partnership with a supplier should be created based on the “win-win” partnership principles. The win–win partnership should not be based only on price-based competition, but mainly on agreed rules for sharing risks and benefits between partners (Oliver & Delbridge, Citation2002).

Customer relationship in the SC involves the whole range of practices that an organization employs aimed at managing complaints, improving satisfaction and building long-term relationships with its customers (Li et al., Citation2006). A close relationship among the manufacturer and customers provides the opportunity to improve the accuracy of demand information, reduce product design and production planning time, and avoid any inventory obsolescence of the manufacturer, which makes it more responsive to the needs of its customer (Flynn et al., Citation2010). Through its connection to product development and innovation (Song & Di Benedetto, Citation2008), the customer partnership is related directly and indirectly to customer satisfaction (Homburg & Stock, Citation2004), and it allows manufacturers to create greater value, cut costs and rapidly detect changes in demand (Flynn et al., Citation2010).

Information sharing designates the degree to which critical and proprietary information is shared with the SC partner, wherein the accuracy, adequacy, timeliness and reliability of the information shared refer to the quality of the information (Koh et al., Citation2007). Information sharing can help reduce uncertainty in SC process integration and enhance the organization’s forecasting and cost reduction capabilities (Liker & Choi, Citation2004). The service of information sharing is an important component of a manufacturing firm’s competitive strategy, which helps organizations in their SC environment that often need to deal with complicated inter-organizational processes (Chan & Chan, Citation2009).

Lean manufacturing in essence, may be called “efficient manufacturing”. It refers to the elimination of anything that does not add value to the production process, such as material flow, inventory and set up time (Gorane & Kant, Citation2015). Lean manufacturing rests on several basic principles, such as eliminating wasteful activities, pursuing continuous process improvement with employee involvement, minimizing process variability, maintaining a synchronized flow of production through visual signals on the shop floor and delegating duties such as quality inspections and periodic maintenance to line workers (Angelis et al., Citation2011). Lean can be reflected in two perspectives: philosophical perspective, which is related to guiding principles or overarching goals, and practical perspective, which consist of a set of management practices, tools or techniques that can be observed directly (Shah & Ward, Citation2007).

Postponement strategy is defined as the practice of pushing forward one or more activities or operations (sourcing, manufacturing and delivering) to a much later point in the SC (Li et al., Citation2006), and as a strategy that purposely delays the accomplishment of a task, instead of beginning it with inadequate or unreliable information (Yang et al., Citation2004). The basic principle of postponement is to increase the supply chain’s flexibility in customer demand by possessing a SC that is able to keep materials undifferentiated for as long as possible until receiving orders from customers (Lee, Citation2004). Indeed, postponement seeks to “pull” instead of “push” the manufacturing process, and thus move inventory from finished goods to semi-finished goods or raw materials (Yeung et al., Citation2007), so it could improve quality, reduce cost of product and save time (Mukherjee, Citation2017).

2.2. Competitive strategy development

Competitive strategy is focused on illuminating the processes regarding how an organization can develop a competitive advantage in the industry in relation to its competitors (Danso et al., Citation2019). In measuring competitive strategy this study involves cost leadership strategy, differentiation strategy, and integrated strategy.

Cost leadership strategy gives priority to the production of standardized products at a low per-unit cost, which is designed for price sensitive consumers (David & David, Citation2017). The provider’s foremost strategic objective of the cost leadership is to operate on explicitly lower costs than rivals although not necessarily the lowest possible cost (Thompson et al., Citation2018). The orientation of organizations that pursue a cost leadership strategy aims to operate efficiently its value chain activities, which enables it to reduce the production cost and exceed the current market share. Thus, in the cost leadership viewpoint, an organization must produce its product using the lowest amount of capital and the lowest possible cost of scale (Dombrowski et al., Citation2018).

Differentiation strategy, an organization adopts a differentiation strategy when it strives to be unique in its industry (or to be perceived as unique) through some dimensions of its product/service that customers value widely (Tanwar, Citation2013). Thus, an organization may charge a premium price to customers for its unique products, which distinctness can be associated with product design, the technology used, the firm’s brand image, product features or customer service (Tanwar, Citation2013). Lapersonne (Citation2017) points out that choosing differentiation strategy with a value proposition that emphasizes uniqueness on certain attributes involves a higher cost due to the aggregation of value on certain activities of the value chain. And all this process will require customers to pay a higher price. To avoid this phenomenon Lapersonne (Citation2017) suggests that the configuration of the differentiated attributes of its value proposition has to once be defined, and then the organization can exploit the operational efficiency of its value-chain activity.

Integrated strategy, an integration of cost leadership and differentiation strategy creates value by optimizing the trade‐off between product cost and quality (Dostaler & Flouris, Citation2006). Integrated strategy allows organizations to easily adapt to dynamic macroeconomic conditions (Moir & Lohmann, Citation2018), where organizations that operate in a dynamic environment must be more flexible and responsive in pursuit of an integrated competitive strategy to be more successful (Danso et al., Citation2019). Thus, in light of the numerous benefits related to both low-cost and differentiation strategies, it is acceptable for some organizations to choose to adopt the integrated strategy, where the disadvantages of one strategic orientation are counterbalanced by the advantages of the other (Kim et al., Citation2004).

2.3. Organizational performance measurement

This study follows the method used by Huo et al. (Citation2014) and Islami (Citation2021b) where organizational performance was measured using two dimensions: operational performance and financial performance.

Operational performance aims to measure organizational success in non-monetary terms, or to be more specific, it is focused on finding items that provide a competitive advantage rather than on financial-focused factors, such as return of investments or net profitability. There is no standard list of non-financial criteria that should be used by all studies that measure operational performance, but it rather depends on the nature of the work (Islami, Citation2021b). This study uses five criteria to represent operational performance: overall product quality, responsiveness to customers, customer service level, delivery speed and delivery dependability.

Financial performance aims to measure the financial aspect of organizational development. Financial metrics have served as a tool for comparing organizations among themselves, to an industry average norm, to benchmarking organizations and evaluating an organization’s behavior over time (Holmberg, Citation2000). The current study uses seven monetary items to measure financial performance: return on investment (ROI), growth in return on investment, growth in sales, return on sales (ROS), growth in return on sales, growth in market share and growth in profit.

2.4. Hypotheses development

2.4.1. The influence of SCM practices on organizational performance

As organizational competition moves beyond individual organizations on the supply chains, it is not enough to focus only on improving intra-organizational quality management practices (Hong et al., Citation2019) in order to improve its whole SC. Several studies argue a positive relationship between divergent perspectives of SCM practices and organizational performance (e.g., see Quang et al., Citation2016; Truong et al., Citation2017). But, these studies viewed SCM practice as independent variables, focusing mainly on their direct effects (Duong et al., Citation2019). For instance, strategic supplier partnership may produce organizational benefits in terms of financial performance (Stanley & Wisner, Citation2001), customer partnership is reported to enhance organizational performance (K. C. Tan et al., Citation1998), and information sharing between organizations has been recognized as a competitive means that enhances firm performance (Whipple & Russell, Citation2007). The divergence perspectives on SCM practices and their role in performance outcome motivate examining the potential role of SCM practices on organizational performance to better understand their value and relevance to the organization operating amid increased uncertainty and volatility in a dynamic and complex environment. Thus, in view of the theoretical arguments and pertinent empirical evidence (Gölgeci & Kuivalainen, Citation2020), SCM practices that are closely related could be expected to have a largely positive role in enhancing the organization’s performance. This study, therefore, proposes the hypothesis:

H1: An organization’s SCM practices have a positive influence on its organizational performance.

2.4.2. The moderating influence of competitive strategy on the relationship of SCM practices and organizational performance

Recently, nearly all business functions are headed and connected with overall organizational strategy (Gold & Heikkurinen, Citation2013). Measuring the relationship between competitive strategy (cost leadership and differentiation strategy) and sustainable financial performance, Banker et al. (Citation2014) and Islami et al. (Citation2020a) argue that both strategies have a positive effect on firm performance, even though the differentiation strategy has precedence on this relationship compared to the cost leadership strategy. Danso et al. (Citation2019) presented a positive effect of integrated strategy on financial performance. Further, Li and Li (Citation2008) considered that an organization’s superior performance can be achieved since its reliance on integrated strategic orientation is tantamount to existing organization‐specific conditions. Despite these findings, there appears to be a lack of empirical research investigating the relationship between competitive strategies and organizational performance in the manufacturing industry (Lee et al., Citation2010). Consequently, this study, proposes the hypothesis:

H2: An organization’s competitive strategy, as cost leadership, differentiation or integrated strategy has a positive influence on its organizational performance.

Since organizations have to contend with competing priorities and business practices within and across their boundaries (Gölgeci et al., Citation2019), competitive strategy might be crucial in leveraging potential synergies between SCM practices and organizational performance, which integrates and uses them wisely toward achieving a specific position in a competitive market.

With the emerging of SCM, the alignment of competitive and SC strategies turn into a challenging new task (Qi et al., Citation2011). In uncertain and difficult times, cooperation may be rewarded within the firm and among the SCM partners (Gölgeci & Kuivalainen, Citation2020) in order to find a course toward organizational success. In this case, a competitive strategy may provide an incentive which strengthens the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance.

Distinctive SC practices ought to be aligned with competitive strategies, where a focal organization invests and develops suppliers with the intention of improving their efficiency and increasing possible collaborative advantages (Hoejmose et al., Citation2013). SC researchers e.g., (González-Benito, Citation2010; Hoejmose et al., Citation2013) have analyzed the relationship between competitive strategies (cost leadership strategy and differentiation strategy) and SC activities, clarifying the knowledge for their alignments with the aim of maximizing competitive performance. Pursuing a cost leadership strategy or a differentiation strategy requires making changes in the organization’s SC activities in order to synchronize them with the competitive strategy selected. Thus, by boosting the competitiveness of the SC, a competitive strategy affects organizational performance (Soni & Kodali, Citation2011). This study expects that competitive strategies would positively moderate the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance, since the entity as a whole could give a more unified response to the SC partners, due to joint inducements to work together to improve organizational achievement. Based on the discussion above, in order to have a thorough understanding of the moderating role of competitive strategies on the correlation between SCM practices and organizational performance, the current study, therefore, proposes the final set of hypotheses:

H3: The positive relationship between SCM practices on organizational performance is strengthened when firms pursue a cost leadership strategy.

H4: The positive relationship between SCM practices on organizational performance is strengthened when firms pursue a differentiation strategy.

H5: The positive relationship between SCM practices on organizational performance is strengthened when firms pursue an integrated strategy.

3. Research methodology

The process of conducting this study includes seven phases: (1) examining the prior literature regarding SCM practices, competitive strategies and organizational performance, (2) discovering and analyzing existing literature for constructing an integrative conceptual model that fits with the research typology used in this study, (3) searching for elements that each testable variable should contain, (4) preparing questionnaires finding practices that each instrument and items that each practice should contain, (5) pre-pilot study, (6) pilot study, and (7) large-scale data analysis.

3.1. Conceptual framework and questionnaire designed

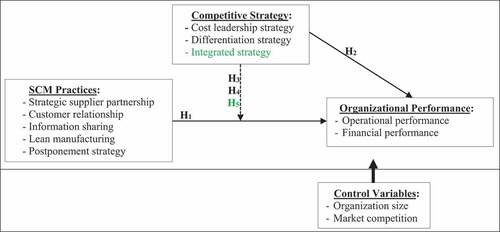

A visualization of the relationships between variables of the current study is shown in , that is, the research framework. Indeed, the conceptual diagram seeks to explore the possible relationship between variables, which aim to build a typical model, of the way that variables tend to be found in relation to each other. The moderation of the direct effect of the research variables used in this study is adopted by Hayes (Citation2018).

Questionnaires were designed including three strategic instruments, such as SCM practices, competitive strategy and organizational performance. When the existing literature could not provide consistent and valid measures, new measures were developed, based on the author’s understanding of the constructs, observations during company visits, and interviews with several high-level managers and academics. The constructs and measures used in this study are shown in Appendix 1.

Since the scales drawn from the existing literature were in English, to ensure the questionnaire’s reliability, the English version was developed first, reviewed and then translated into Albanian by an English language expert and controlled by a knowledgeable Kosovan professor of management. The Albanian version was then translated back into English by a different professor of English and a strategic professor fluent in the English language. Some questions in Albanian were reworded to better mirror the original meaning of the questions in English.

We used the existing validated scales for measuring SCM practices (Chen & Paulraj, Citation2004; Jayaram et al., Citation2014; K.C. Tan et al., Citation2002; Li et al., Citation2006; Shah & Ward, Citation2002; Wu et al., Citation2014), competitive strategy (Danso et al., Citation2019; Huo et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2010), operational performance (Huo et al., Citation2014) and financial performance (Flynn et al., Citation2010; Gölgeci & Kuivalainen, Citation2020; Huo et al., Citation2014; Qi et al., Citation2011), items were modified for the purposes of the current study. Respondents indicated this on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 7.

It is worth clarifying that, to measure integrated strategy, are followed Aulakh et al. (Citation2000), Acquaah (Citation2007), and Danso et al. (Citation2019). Where, to examine the impact of the simultaneous implementation of cost leadership and differentiation strategies in moderating the impact of SCM practices on organizational performance, one variable is included in separate model (Acquaah, Citation2007). To classify the integrated strategy, an interaction between the cost leadership and differentiation strategies is created (CosLea_x_DiffStr) using their centered (de-meaned) values (Aulakh et al., Citation2000; Hayes, Citation2018).

In this study, is controlled for organization size and market competition, which are likely to influence our results. Organization size is controlled because it may impact financial resources (Brammer & Millington, Citation2006). Organization size was measured as the natural logarithmic transformation of the number of full‐time employees (Danso et al., Citation2019). Market competition is included as a control variable as the organizations that operate in high dynamic industries have a shorter product life cycle (Koufteros et al., Citation2007), and show higher revenue volatility and customer turnover compared to those in low dynamic industries (Wu et al., Citation2014). This study followed Acquaah (Citation2007), where respondents were asked on seven questions to indicate the degree to which the activities had taken place in their organization’s industry between March 2017 and March 2020 (see Appendix 1).

3.2. Pre-pilot Study, Pilot Study and Large-Scale Method

In the pre-pilot study, research items were reviewed by fifteen doctoral and master’s students of the management department, three professors (one strategic management professor, one operational professor and one financial management professor), and re-evaluated through structured interviews with two practitioners who were asked to remark on the appropriateness of the research constructs. Next, the first version of the questionnaire was pre-tested in 10 manufacturing organizations from Kosovo, which involved face-to-face discussions.

In the pilot study stage using the Q-sort method, SC managers were asked to act as judges and categorize the items into the five dimensions of SCM practice. A strategic manager was asked to place the items into the two dimensions of competitive strategy and into the operational performance dimension. And financial managers were asked to place the items into the dimension of financial performance.

For large-scale method, the sampling frame used for the purposes of this study was based on the registry of the Kosovo Agency of Statistics. Six hundred organizations that met our selection criteria were randomly selected among a total of 10,190 organizations registered within KAS. Of the 600 manufacturing organizations, only 447 organizations had updated contact information. It was made sure that firms that were contacted had a minimum of 10 full‐time employees, whereas the maximum number was not limited. The respondents sought in these organizations were those high and mid-level managers that have inclusive responsibilities enabling them to have a clear understanding and a complete view of the organization’s strategy and functioning, and financial managers that oversee financial aspects of the organizations.

The data was collected during the period of July–September 2020. Gathering data from respondents passed through two waves. In the first wave, dual respondents from each participant organization were required, where high and mid-level managers of 447 organizations were approached in person with an online questionnaire to obtain information on SCM practices, competitive strategy and operational measures. The questionnaires were mailed, along with a cover letter clarifying the study’s objectives. Follow-up telephone calls and mailings were used to improve the response rate. A total of 346 responses were obtained from 173 organizations, with an effective response rate of 29% of the sample. After screening, two of the questionnaires were found to be incomplete, and six organizations returned surveys with a single response. These questionnaires were rejected, leaving 165 usable responses. Two months after the first wave, the finance managers of the 165 organizations were contacted in person to tap financial performance measures. A total of 161 questionnaires were obtained from the finance managers, four of which had not been filled in and were discarded. Finally, 157 samples were used in our subsequent analyses, with an effective response rate of 26% of the sample, which was deemed adequate for our study.

Key characteristics of the sample organizations are summarized in . The results show that a large percentage of our respondents are from the construction and food sectors. Over half of the responding organizations had less than 49 employees, and about 43% had over 20 years of work experience. Our analysis shows that the responding organizations had adopted at least one international quality standard.

Table 1. Characteristics of sample organizations (N = 157)

The current study addressed potential non-response bias during the data collection process through two means. Firstly, to mitigate the possibility of common method bias, dual respondents from each participant organization were required to be included in the final analysis for all variables except financial performance. The issue of common source bias is a critical one, and can arise when the same respondent provides the measure of predictor and criterion variables (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), who stressed that such issues may be expected to be minimized by tacking two responses from two different respondents of the same organization.

Secondly, Harman’s single-factor test is used as a statistical remedy to identify common-method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). The results showed that no single factor is found to explain more than fifty percent (>50%) of the variance. Consequently, there was no serious common-method bias in this study.

4. Data analyses and measurement

The purification and reliability of the measurement for first and second-order variables were checked using the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The IBM SPSS AMOS 26 package software was used to analyze the model fit of second-order constructs. To measure the model fit this study similar to Islami (Citation2021b) uses five criteria: chi-square divided by degree of freedom (x2/df); IFI; NNFI; CFI; and SRMR.

4.1. Validation of first and second-order constructs

To detect the underlying dimensions a maximum likelihood factor analysis with promax rotation was used. For simplicity, only loadings above .45 (Hair et al., Citation2019) are displayed in .

Table 2. Measurement items (with factor loadings) for first-order constructs

For SCM practices (SCMp), a factor analysis was initially conducted using the 25 items that measure the five first-order constructs. An initial factor analysis indicated that six items had a low-loading on their respective factors (see appendix 1). After removing these six items, the 19 remaining items were factor analyzed and the results indicated that all items loaded on their respective factors with loadings above the recommended cut-off value of .45, all of the t-values were greater than 2.0 (Huo et al., Citation2015), and none of the items cross-loaded on other factors, as shown in .

The competitive strategy (CS) construct was initially represented by two dimensions and 12 items. An initial factor analysis indicated that two items had a low-loading on their respective factors. After removing these two items, the remaining items were factor analyzed and the results indicated that all items loaded on their respective factors with most loadings above the recommended cut-off value of .45, all of the t-values were greater than 2.0, as shown in .

When organizational performance (OP) was factor analyzed, two factors emerged with one over-loading item (OpePer_3 over-loaded its factor). OpePer_3 was removed and factor analysis was performed on the remaining items, and the results are shown in . It can be seen that all items loaded on their respective factors, with most loadings above .45 and all of the t-values were greater than 2.

Finally, the market competition (MC) construct was initially represented by one dimension and seven items. An initial factor analysis indicated that one item: MarCom_2 had a low-loading on its factor. After removing this item, the remaining items were factor analyzed and the results indicated that all items loaded on its factor, with most loadings above .45 and all of the t-values were greater than 2.0 ().

To discuss assessing the reliability of the constructs were used Cronbach’s alpha. report the number of items and reliability values for each of the constructs, means and standard deviations. The reliability values for all constructs were higher than the suggested threshold of 0.7, which are considered acceptable (Hair et al., Citation2019), and further confirms the reliability of the measurement items.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations and reliability of the first-order constructs of (a) SCM practices, (b) competitive strategy, (c) organizational performance and (d) market competition

Then, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) measurement models were run to estimate first-order construct validity. The results indicated that for all constructs, the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) estimates were above the recommended thresholds of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively, which indicates convergent validity (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation2012). Discriminant validity was evaluated and showed that the square roots of AVE on diagonal were greater than correlations in all cases , as a result discriminant validity was confirmed.

Table 4. Convergent and discriminant validity of the first-orderfactors.a

In second-order models, a second condition must be met for convergent validity (Huo et al., Citation2015; Peng et al., Citation2007), the first-order factors “factor scores” must load significantly on their respective second-order factors. The CFA results presented in show that the second-order factor loadings were greater than .45 (most of loadings were greater than 0.70), and all of the t-values were greater than 2.0, demonstrating convergent validity.

Table 5. CFA results of second-order constructs

Additionally, this study measured the credibility for each second-order construct, using target coefficient index that compares chi-square values of first-order and second-order models (Li et al., Citation2006). SCM practices, the fit statistics for the second-order construct are shown in , where (x2/df, IFI, NNFI, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR) represent a good model-data fit (Hair et al., Citation2019). The coefficients were all significant at p < .001. The target coefficient index is 94.4%, which is strong evidence of the existence of a higher-order SCM practices construct. Organizational performance (), the fit indexes for the second-order model also showed a good model-data fit. The coefficients were all significant at p < .001. The target coefficient index is 100%, indicating the existence of a second-order competitive advantage construct.

4.2. Hypotheses testing

provides the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the main variables. It shows significant correlations between variables. Indeed, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) of the study variables were all less than 10, indicating that there is no cause for concern regarding multicollinearity (Hoejmose et al., Citation2013).

Table 6. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of the main variables (N = 157)

Firstly, to measure if larger organizations are more likely to influence the implementation of supply chain compared to smaller organizations because they possess the resources and capabilities necessary to execute complex processes across partners (Li et al., Citation2006; Wu & Chang, Citation2012). Model O, tests the relationship between organization size and SCM practices. Results show that organization size is significant and positively related to SCMp (p < 0.01), which indicates that, in the sample, larger organizations apply more SCM practices than smaller organizations. Then, a series of hierarchical multiple regression analysis was used to test hypotheses. summarizes the regression results. Model I tests the relationship between the control variables and organizational performance. Organization size is significant and positively related to organizational performance (p < 0.05), which indicated that larger organizations achieve better organizational performance than smaller organizations. In Model II, the SCM practices variable is added to Model I, it significantly improves the explanatory power of Model I as indicated by the F-test for the change in adjusted R2 (R2 = 13.6%, F > 27.466, p < 0.001), and it is therefore clear that SCM practices plays a significant role in performance of the manufacture organizations. The result shows that SCM practices is positively and significantly related to organizational performance (p < 0.001), thus supporting H1 (H1↑).

Table 7. Results of hierarchical regression analysis on organizational performance (N = 157)a

In Model III, to measure the direct effect of the competitive strategy variables, cost leadership and differentiation strategies were added to the Model II, which significantly improves the explanatory power of Model II as indicated by the F-test for the change in adjusted R2 (R2 = 25.9%, F > 37.859, p < 0.001). The regression results show that the cost leadership and differentiation strategies are both positive and significantly related to organizational performance (p < 0.001 for cost leadership and p < 0.05 for differentiation). Whereas, the result indicates that the interaction between cost leadership strategy and differentiation strategy is significant and negatively related to organizational performance. These outcomes highlight that, while the pursuit of singular competitive strategies enhances organizational performance, the pursuit of a combination strategy worsens organizational performance. Thus, H2 was partially supported.

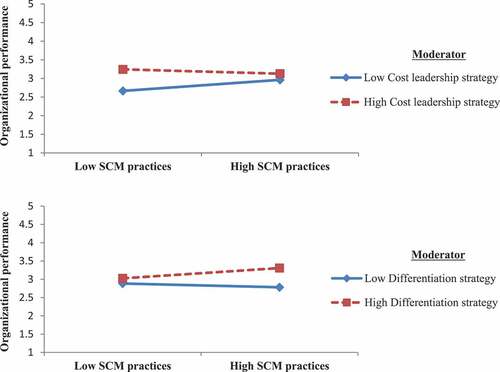

Finally, in Model IV, to measure the moderation effect of competitive strategy the interactions between SCM practices and three competitive strategies were added to the Model III, which marginally significant changed the explanatory power of Model III as indicated by the F-test for the change in adjusted R2 (R2 = 0.9%, F > 2.412, p < 0.10). However, in this model cost leadership strategy had a significant and negative moderating effect (p < 0.05) on the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance, indicating that H3 was not supported (H3↓). Differentiation strategy had a marginally significant and positive moderating effect (p < 0.10) on the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance, supporting H4 (H4↑). While, the integrated strategy had a non-significant and negative moderating effect on the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance, indicating that H5 was not supported (H5↓).

5. Discussion and research implications

This study replicates and broadens the previous research in different areas, such as: SCM, competitive strategy and organizational performance.

The results indicated that the implementation of SCM practices is related to organization size, where larger organizations apply the practices of SCM more than smaller organizations. This finding supports the previous SCM literature where Li et al. (Citation2006) and Huo et al. (Citation2014) have stressed that small companies (based on the number of employees) are seldom involved in sophisticated SCM activities. Hence, larger organizations are more likely to influence the implementation of SC practices compared to smaller organizations, as they possess the capabilities and resources necessary to execute complex processes across partners (Wu & Chang, Citation2012).

5.1. The role of SCM practices in influencing organizational performance

The direct effect of SCM practices on organizational performance was measured. The findings indicated that SCM practices developed from organizations have a positive impact on organizational performance, which are parallel to those of Li et al. (Citation2006), Quang et al. (Citation2016), Truong et al. (Citation2017), and Duong et al. (Citation2019), who have argued a positive relationship between divergent perspectives of SCM practices and firm performance.

By a fine-grained analysis of the results, it may be indicated that an adequate application of various SCM practices, such as creating a strategic supplier partnership, building a credible customer relationship, using appropriate information sharing system, trying to realize lean manufacturing and involving postponement strategy on the production process, may provide an improvement for the organization on operational performance indicators, such as on product quality, responsiveness to customers, delivery speed, delivery dependability, and on financial performance indicators, such as growth in return on investment, growth in sales, growth in return on sales, growth in market share, and growth in profit. Thus, SCM practices in Kosovan manufacturing organizations indeed act as links between the organization and the beyond organizational border community by diffusing information with trading partners and providing access to organizational resources.

Hence, it is argued that an organization’s access to resources and other benefits from creating a good strategic cooperation with suppliers, such as involving suppliers in the design of new products, solving problems jointly with suppliers, and involving key suppliers in business and strategy planning, may entail significant obligations for trading partners and provide favors for the focal organization. Also, creating a good partnership with customers through measuring and evaluating customer satisfaction, determining customer future expectations, facilitating customers’ ability to seek assistance from the organization, then, sharing credible information between trading partners, or delaying final product fitting activities until customer orders have actually been received by the organization, may provide an improvement on product quality, responsiveness to customers and delivery speed, which may bring in a high profit for the organization.

5.2. The moderating effect of competitive strategy

The direct relationship between competitive strategies and organizational performance hypothesized as, an organization’s competitive strategy (as cost leadership, differentiation or integrated strategy) has a positive influence on its organizational performance, was partially supported. The results support the findings by authors (e.g., Banker et al., Citation2014; Danso et al., Citation2019; Islami et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Based on these findings, it can be summarized that organizations which pursue a cost leadership strategy through the implementation of economization elements, such as realizing a cost advantage of raw material procurement, reducing cost of production, achieving an efficient way of operation, and implementing strict control of cost, may provide a better organizational performance. Similarly, when organizations implement the elements of differentiation strategy, such as providing a product with unique features, improving their products continuously, offering a high product quality into the market, and highlighting effective co-ordination among different functional areas that ensure customer satisfaction, may provide a higher organizational performance compared to those organizations that do not implement these elements. Whereas, results of this study indicated that organizations that attempt to implement both strategies simultaneously (pursue an integrated strategy) fail, as they will be “stuck in the middle”.

The contingency effect of competitive strategies on the role of practices has been identified in the existing literature (e.g., Acquaah, Citation2007; Danso et al., Citation2019; Huo et al., Citation2014). This study has examined the contingency role of competitive strategies in the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance. Where it is hypothesized that the positive relationship between SCM practices on organizational performance is strengthened when firms pursue a cost leadership strategy, but it was not supported. This measurement indicated that pursuing cost leadership strategy does not strengthen the positive relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance (see ). It may be true because based on transaction cost economics theory, the transaction cost of internal exchange is lower than the exchange with external partners (Huo et al., Citation2014). While, related to the differentiation strategy. Results indicated that differentiation strategy strengthens the positive relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance (see ). One possible explanation for these results/relationships may be that the implementation of SCM practices requires more resources and investments. Thus, cost leadership organizations cannot leverage their effectiveness to improve financial performance. In contrast, differentiation organizations are focused on product quality, deliver quality and process quality, which are costly but make the organization different from competitors. This quality improvement boosts the customer’s willingness to pay a premium price, which may provide a better organizational performance.

Kosovan manufacture organizations appear to create networking partnerships with other organizations to mitigate the effects of international competitors on the market and to obtain product quality, responsiveness to customers, delivery speed and delivery dependability in order to absorb market opportunities. Based on the results, implementing a cost leadership strategy and differentiation strategy is beneficial to Kosovan organizations. To sum up, this study revealed that the positive influences of SCM practices are conditioned by the competitive strategies that organizations pursue.

5.3. Theoretical and practical implications

In response to calls for further analyzing the contingency role of competitive strategies on the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance, the current study advances the field in three ways.

First, it validates the strategic integration between second-order constructs of SCM practices and organizational performance, and the first-order construct of competitive strategies, which have generally been poorly defined and there has been a high degree of variability in people’s understanding of them. It has been shown that SCM practices form a second-order construct composed of five first-order constructs: strategic supplier partnership, customer relationship, information sharing, lean manufacturing and postponement strategy.

Second, where a few studies have investigated the effect of a bundle of SCM practices on organizational performance composed by financial and non-financial criteria. This study fills this gap by providing empirical evidence of the link between a set of SCM practices that aim to improve the organizational performance. It found that SCM practices play an important role in enhancing organizational performance, which deserve more attention in future studies.

Third, in response to the call made by K.C. Tan et al. (Citation2002) and Hohenstein et al. (Citation2014) for further research to explore the impact of SCM practices on organizational performance by including other areas of the organization and their perspective, this study investigates SCM practices under competitive strategies on organizational performance. In this way, the results open the “black box” of the link between SCM practices and competitive strategy. Hence, the broadened view of the strategic instruments operationalized here broadens the work evidenced in the literature, and it provides the lens for a more comprehensive and fine-grained analysis of the effect of SCM practices under different competitive strategies on organizational performance in emerging economies.

The study’s findings also have significant practical implications and insights that may allow organizations to better manage and coordinate SC and competitive strategies, providing recommendations for strategic managers in adopting SCM practices under different competitive strategies. Therefore, it helps practitioners in three ways.

First, scholars agree that it is critical for SC practitioners to separate truth from hype (Stank et al., Citation2011), understand the importance of SCM (Huo et al., Citation2015) and the elements required for its success (Ellinger et al., Citation2014; Huo et al., Citation2015). This study shows that SCM practices can significantly enhance organizational performance, suggesting that when designing and implementing SCM practices, manufacturers should have a strategic plan beforehand.

Second, it highlighted the characteristics of Kosovan manufacturers in terms of implementing various SCM practices under different competitive strategies. Kosovan manufacturers are capable of managing different types of SCM practices under competitive strategies. Therefore, this study showed a negative effect of cost leadership strategy on the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance, and a positive effect of differentiation strategy on the relationship between SCM practices and organizational performance.

Third, the emergence of a global marketplace has presented great challenges for organizations to successfully manage globe-spanning supply chains. From this perspective, this study, which examines competitive strategic differences, not only provides the rules for organizations in specific countries to manage their supply chains, but also offers suggestions for multinational organizations to manage their global supply chains in local countries.

6. Conclusion

In this study, measures are developed for a broader conceptualization of the SCM practices to provide empirical evidence of the direct and contingent value on organizational performance. To test the research questions: do organizations with high levels of SCM practices have high levels of organizational performance; do organizations with high levels of competitive strategy have high levels of organizational performance; and do organizations with high levels of SCM practices moderated by competitive strategies have a high level of organizational performance? A comprehensive, valid and reliable instrument for assessing research variables was developed. The instruments were tested using rigorous statistical tests including convergent validity, discriminant validity, reliability and the validation of first- and second-order constructs (Li et al., Citation2006).

This study supports that an integrative strategy developed from the SCM practices relationships moderated by competitive strategy are significant predictors of organizational performance after controlling for organization size and market competition. It finds that SCM practices have positive and direct effects on organizational performance, that pursuing a competitive strategy cost leadership or differentiation strategy has a positive effect on organizational performance, that SCM practices moderated by cost leadership strategy have negative effects on organizational performance, and that SCM practices moderated by differentiation strategy have positive effects on organizational performance.

In summary, it can provide a possible explanation for the inconsistent findings about the effects of SCM practices under competitive strategies on organizational performance. In this respect, the results showed that the main goal that assumes to create an integrative strategy approach is increasing the benefits of organizational performance by coordinating and fitting closely the main SCM practices and competitive strategy of an organization, which enables it to better utilize opportunities that may lead to business success.

7. Limitation and future research

Although this research study contributes to both academic and practice circles, it has several limitations. The limitations of this research study have opened up avenues for future research studies.

First, subjective measures of SCM practices, competitive strategies and organizational performance were used. The choice of perceptual measures of organizational performance was driven also by the difficulty of obtaining objective performance measures in emerging economies. Instead of choosing perceptual measures of organizational performance and other variables, future studies can examine this relationship using objective measures at least for organizational performance. An objective assessment of organizational performance can be achieved by using secondary data, such as organization records or financial statements.

Second, although this study uses five constructs to represent SCM practices, they do not cover all of the aspects of SCM, which is a mature discipline with many concepts. Future research can expand the domain of SCM practices by exploring additional dimensions, such as: JIT/lean capability, geographical proximity, logistics integration, cross-functional coordination, which have been overlooked in this study.

Third, it has only measured the upright relationship between SCM practices, competitive strategies and organizational performance. Future studies using an integrative holistic approach can examine the reverse causality to identify if organizational performance has an impact on pursuing competitive strategies and implementing SCM practices. Since organizational performance may influence the way of obtaining SCM practices and blurry the cause-effect link revealed in this study.

Fourth, the data used in this study covered the organizational position prior to the “COVID 19” pandemic crisis. Future studies should collect fresh longitudinal data to improve and broaden this research stream, and to compare the results before and after the pandemic crisis.

Statement

We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere nor it is currently under consideration for publication elsewhere. We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

We confirm that we have given due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property.

We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process (including editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). He/she is responsible for communicating about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs. We confirm that we have provided a current, correct email address which is accessible by the Corresponding Author and which has been configured to accept email from: [email protected].

Acknowledgements

The data analyzed on this paper are collected by first author Xhavit Islami for his doctoral thesis. The same data were used to test the model proposed in this paper, which is totally different from the model tested in doctoral thesis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xhavit Islami

Xhavit Islami is a PhD in Organizational Sciences and Management. He has received his Ph.D. from “Ss. Cyril and Methodius” University, Republic of North Macedonia, whereas MSc. and Bsc. degrees he has received from the University of Prishtina, Republic of Kosovo. His research interest includes: strategic management, supply chain management, and human resource management. He is a member of different scientific boards and a regular contributor to a number of journals over the years. His research contributions have drawn greater response to issues including teamwork, management by objectives, competitive strategies, and human resource management that have been widely acknowledged.

Marija Topuzovska Latkovikj (PhD) works as full professor in the Institute for Sociological and Political-Legal Research, at University “Ss. Cyril and Methodius”, Republic of North Macedonia. She obtained the scientific degree Doctor in Organizational Sciences (Management) in 2011 and scientific degree Master of Human Resources Management in 2008. Along with teaching, she is involved in other academic and administrative activities also, with about 18 years of experience in research and teaching. Her research interest areas are based on human resource management, organizational behavior, and research methodology in organizational science. As a lead researcher or member of a research team, she has participated in several national and international projects. Her current research project is on the National Strategy for Youth (2015–2026).

References

- Acquaah, M. (2007). Managerial social capital, strategic orientation, and organizational performance in an emerging economy. Strategic Management Journal, 28(12), 1235–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.632

- Adăscăliței, D., & Guga, S. (2018). Tensions in the periphery: Dependence and the trajectory of a low-cost productive model in the Central and Eastern European automotive industry. European Urban and Regional Studies, 27(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418795205

- Angelis, J., Conti, R., Cooper, C., & Gill, C. (2011). Building a high‐commitment lean culture. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 22(5), 569–586. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410381111134446

- Aulakh, P. S., Kotabe, M., & Teegen, H. (2000). Export strategies and performance of firms from emerging economies: Evidence from Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 342–361. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556399

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x

- Banker, D. R., Mashruwala, R., & Tripathy, A. (2014). Does a differentiation strategy lead to more sustainable financial performance than a cost leadership strategy? Management Decision, 52(5), 872–896. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-05-2013-0282

- Bimha, H., Hoque, M., & Munapo, E. (2019). The impact of supply chain management practices on industry competitiveness: A mixed-methods study on the Zimbabwean petroleum industry. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 12(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2019.1613785

- Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2006). Firm size, organizational visibility and corporate philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2006.00424.x

- Chan, H. K., & Chan, F. T. S. (2009). Effect of information sharing in supply chains with flexibility. International Journal of Production Research, 47(1), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540600767764

- Chen, I. J., & Paulraj, A. (2004). Towards a theory of supply chain management: The constructs and measurements. Journal of Operations Management, 22(2), 119–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2003.12.007

- Danso, A., Adomako, S., Amankwah‐Amoah, J., Owusu‐Agyei, S., & Konadu, R. (2019). Environmental sustainability orientation, competitive strategy and financial performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(5), 885–895. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2291

- David, F. R., & David, F. R. (2017). Strategic management: Concepts and cases: A competitive advantage approach (16th ed.). Pearson education Limited.

- Dombrowski, U., Krenkel, P., & Wullbrandt, J. (2018). Strategic positioning of production within the generic competitive strategies. Procedia CIRP, 721, 1196–1201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.03.007

- Dostaler, I., & Flouris, T. (2006). Stuck in the middle revisited: The case of the airline industry. Journal of Aviation, Aerospace Education & Research, 15(2), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.15394/jaaer.2006.1502

- Duong, B. A. T., Truong, H. Q., Sameiro, M., Sampaio, P., Fernandes, A. C., Vilhena, E., Bui, L. T. C., & Yadohisa, H. (2019). Supply chain management and organizational performance: The resonant influence. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 36(7), 1053–1077. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-11-2017-0245

- Ellinger, A. E., Ellinger, A. D., & Maura Sheehan, P. (2014). Leveraging human resource development expertise to improve supply chain managers’ skills and competencies. European Journal of Training and Development, 38(1/2), 118–135. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejtd-09-2013-0093

- Flynn, B. B., Huo, B., & Zhao, X. (2010). The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. Journal of Operations Management, 28(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.06.001

- Gold, S., & Heikkurinen, P. (2013). Corporate responsibility, supply chain management and strategy: In search of new perspectives for sustainable food production. Journal of Global Responsibility, 4(2), 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1108/jgr-10-2012-0025

- Gölgeci, I., Karakas, F., & Tatoglu, E. (2019). Understanding demand and supply paradoxes and their role in business-to-business firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 76(1), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.08.004

- Gölgeci, I., & Kuivalainen, O. (2020). Does social capital matter for supply chain resilience? The role of absorptive capacity and marketing-supply chain management alignment. Industrial Marketing Management, 84(1) , 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.05.006

- González-Benito, J. (2010). Supply strategy and business performance: An analysis based on the relative importance assigned to generic competitive objectives. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 30(8), 774–797. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571011068162

- Gorane, S. J., & Kant, R. (2015). Supply chain practices. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 64(5), 657–685. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijppm-10-2013-0180

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning EMEA, British Library.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press, A Division of Guilford Publications, Inc.

- Hoejmose, S., Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2013). An empirical examination of the relationship between business strategy and socially responsible supply chain management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 33(5), 589–621. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571311322733

- Hohenstein, N. O., Feisel, E., & Hartmann, E. (2014). Human resource management issues in supply chain management research: A systematic literature review from 1998 to 2014. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 44(6), 434–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijpdlm-06-2013-0175

- Holmberg, S. (2000). A systems perspective on supply chain measurements. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 30(10), 847–868. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030010351246

- Homburg, C., & Stock, R. M. (2004). The link between salespeople’s job satisfaction and customer satisfaction in a business-to-business context: A dyadic analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(2), 144–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070303261415

- Hong, J., Liao, Y., Zhang, Y., & Yu, Z. (2019). The effect of supply chain quality management practices and capabilities on operational and innovation performance: Evidence from Chinese manufacturers. International Journal of Production Economics, 212(1), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.01.036

- Huo, B., Han, Z., Chen, H., & Zhao, X. (2015). The effect of high-involvement human resource management practices on supply chain integration. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(8), 716–746. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijpdlm-05-2014-0112

- Huo, B., Qi, Y., Wang, Z., & Zhao, X. (2014). The impact of supply chain integration on firm performance: The moderating role of competitive strategy. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 19(4), 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1108/scm-03-2013-0096

- Islami, X. (2021a). The relation between human resource management practices, supply chain management practices and competitive strategy as strategic instruments and their impact on organizational performance in manufacturing industry. Doctoral dissertation, “Ss. Cyril and Methodius” University in Skopje.

- Islami, X., Mustafa, N., & Topuzovska Latkovikj, M. (2020a). Linking Porter’s generic strategies to firm performance. Future Business Journal, 6(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-0009-1

- Islami, X., Topuzovska Latkovikj, M., Drakulevski, L., & Borota Popovska, M. (2020b). Does differentiation strategy model matter? Designation of organizational performance using differentiation strategy instruments – An empirical analysis. Business: Theory and Practice, 21(1), 158–177. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2020.11648

- Islami, X. (2021b). How to integrate organizational instruments? The mediation of HRM practices effect on organizational performance by SCM practices. Production & Manufacturing Research, 9(1), 206–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693277.2021.1978007

- Jacobs, F. R., & Chase, R. B. (2014). Operations and supply chain management (14th ed.). Mc Graw-Hill Irwin.

- Jayaram, J., Choon Tan, K., & Laosirihongthong, T. (2014). The contingency role of business strategy on the relationship between operations practices and performance. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 21(5), 690–712. https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-10-2012-0066

- Khan, A., & Siddiqui, D. A. (2018). Information sharing and strategic supplier partnership in supply chain management: A study on pharmaceutical companies of Pakistan. Asian Business Review, 8(3), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.18034/abr.v8i3.162

- Kim, E., Nam, D. I., & Stimpert, J. L. (2004). The applicability of porter‘s generic strategies in the digital age: Assumptions, conjectures, and suggestions. Journal of Management, 30(5), 569–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2003.12.001

- Kitchot, S., Siengthai, S., & Sukhotu, V. (2020). The mediating effects of HRM practices on the relationship between SCM and SMEs firm performance in Thailand. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 26(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-05-2019-0177

- Koh, S. C. L., Demirbag, M., Bayraktar, E., Tatoglu, E., & Zaim, S. (2007). The impact of supply chain management practices on performance of SMEs. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 107(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570710719089

- Koufteros, X. A., Edwin Cheng, T. C., & Lai, K. H. (2007). “Black-box” and “gray-box” supplier integration in product development: Antecedents, consequences and the moderating role of firm size. Journal of Operations Management, 25(4), 847–870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2006.10.009

- Kumar, A., Singh, R. K., & Modgil, S. (2020). Exploring the relationship between ICT, SCM practices and organizational performance in agri-food supply chain. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(3), 1003–1041. https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-11-2019-0500

- Lapersonne, A. H. (2017). The hybrid competitive strategy framework: a managerial theory for combining differentiation and low-cost strategic approaches based on a case study of a European textile manufacturer (Doctoral dissertation). The University of Manchester.

- Lee, F. H., Lee, T. Z., & Wu, W. Y. (2010). The relationship between human resource management practices, business strategy and firm performance: Evidence from steel industry in Taiwan. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(9), 1351–1372. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.488428

- Lee, H. L. (2004). The triple-A supply chain. Harvard Business Review, 82(10), 102–113.

- Li, C. B., & Li, J. J. (2008). Achieving superior financial performance in china: differentiation, cost leadership, or both? Journal of International Marketing, 16(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.16.3.1

- Li, S., Ragu-Nathan, B., Ragu-Nathan, T. S., & Rao, S. S. (2006). The impact of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage and organizational performance. Omega, 34(2), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2004.08.002

- Liker, J. K., & Choi, T. Y. (2004). Building deep supplier relationships. Harvard Business Review, 82(12), 104–113.

- Miles, J. A. (2012). Management and organization theory: A Jossey-Bass reader (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Moir, L., & Lohmann, G. (2018). A quantitative means of comparing competitive advantage among airlines with heterogeneous business models: Analysis of U.S. airlines. Journal of Air Transport Management, 69(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2018.01.003

- Mukherjee, K. (2017). Mass Customization. In Supplier Selection (pp. 59–66). 88. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-3700-6_3

- Oliver, N., & Delbridge, R. (2002). The characteristics of high performing supply chains. International Journal of Technology Management, 23(1/2/3), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtm.2002.002998

- Peng, D. X., Schroeder, R. G., & Shah, R. (2007). Linking routines to operations capabilities: A new perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 26(6), 730–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2007.11.001

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Qi, Y., Zhao, X., & Sheu, C. (2011). The impact of competitive strategy and supply chain strategy on business performance: The role of environmental uncertainty. Decision Sciences, 42(2), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2011.00315.x

- Qrunfleh, S., & Tarafdar, M. (2013). Lean and agile supply chain strategies and supply chain responsiveness: The role of strategic supplier partnership and postponement. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 18(6), 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1108/scm-01-2013-0015

- Quang, H. T., Sampaio, P., Carvalho, M. S., Fernandes, A. C., Binh An, D. T., Vilhenac, E., & Sampaio, Maria Sameiro Carvalho And Ana Cristina Fernandes, P. (2016). An extensive structural model of supply chain quality management and firm performance. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 33(4), 444–464. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijqrm-11-2014-0188

- Shah, R., & Ward, P. T. (2002). Lean manufacturing: Context, practice bundles, and performance. Journal of Operations Management, 21(2), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6963(02)00108-0

- Shah, R., & Ward, P. T. (2007). Defining and developing measures of lean production. Journal of Operations Management, 25(4), 785–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2007.01.019

- song, M., & Di Benedetto, C. A. (2008). Supplier’s involvement and success of radical new product development in new ventures. Journal of Operations Management, 26(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2007.06.001

- Soni, G., & Kodali, R. (2011). The strategic fit between “competitive strategy” and “supply chain strategy” in Indian manufacturing industry: An empirical approach. Measuring Business Excellence, 15(2), 70–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/13683041111131637

- Stank, T. P., Dittmann, J. P., & Autry, C. W. (2011). The new supply chain agenda: a synopsis and directions for future research. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management.

- Stanley, L. L., & Wisner, J. D. (2001). Service quality along the supply chain: Implications for purchasing. Journal of Operations Management, 19(3), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6963(00)00052-8

- Talib, F., Rahman, Z., & Qureshi, M. N. (2011). A study of total quality management and supply chain management practices. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 60(3), 268–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401111111998

- Tan, K. C., Kannan, V. R., & Handfield, R. B. (1998). Supply chain management: Supplier performance and firm performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 34(3), 2–9.

- Tan, K. C., Lyman, S. B., & Wisner, J. D. (2002). Supply chain management: A strategic perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22(6), 614–631. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570210427659

- Tanwar, R. (2013). Porter’s Generic Competitive Strategies. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 15(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.9790/487x-1511117

- Thompson, A. A., Peteraf, M. A., Gamble, J. E., & Strickland, A. J. (2018). Crafting and executing strategy: The quest for competitive advantage—concepts and cases (21st ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Truong, H. Q., Sameiro, M., Fernandes, A. C., Sampaio, P., Duong, B. A. T., Duong, H. H., & Vilhenac, E. (2017). Supply chain management practices and firms’ operational performance. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 34(2), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijqrm-05-2015-0072

- Whipple, J. M., & Russell, D. (2007). Building supply chain collaboration: A typology of collaborative approaches. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 18(2), 174–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090710816922

- Wu, I. L., & Chang, C. H. (2012). Using the balanced scorecard in assessing the performance of e-SCM diffusion: A multi-stage perspective. Decision Support Systems, 52(2), 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2011.10.008

- Wu, I. L., Chuang, C. H., & Hsu, C. H. (2014). Information sharing and collaborative behaviors in enabling supply chain performance: A social exchange perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 148(1) , 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.09.016

- Yang, B., Burns, N. D., & Backhouse, C. J. (2004). Postponement: A review and an integrated framework. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 24(5), 468–487. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570410532542

- Yeung, J. H. Y., Selen, W., Deming, Z., & Min, Z. (2007). Postponement strategy from a supply chain perspective: Cases from China. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 37(4), 331–356. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030710752532