?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the causality between Chinese Investment under China–Pakistan Economic Corridor and economic growth in Pakistan by using the Autoregressive distributed lag estimation framework. For this purpose, quarterly time series data ranging from 2009 to 2018 were used. In short run, results failed to establish causality from Chinese Foreign Direct Investment to Economic Growth, while a unidirectional causality was found from economic growth to Chinese Foreign Direct Investment. However, results of this study confirm that the variables of interest are bound together in the long run only when Chinese Foreign Direct Investment is the dependent variable, indicating that enhanced economic growth attracts more Foreign Direct Investment in Pakistan. Results of this study have important implications for economists and policymakers to make policies alongside China Pakistan Economic Corridor in order to ensure that the potential spillovers from the inflow of Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in the shape of China Pakistan Economic Corridor infrastructure projects create domestic spillover. Moreover, the insignificant effect of Chinese Foreign Direct Investment on the economic growth of Pakistan in the short run is due to the real challenges that Pakistan faces due to access to credit and state capacity to sustain economic growth. Therefore, it is recommended that government should formulate policies for technologically demanding sectors to bring diversity in the products and increase exports.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper examines the causal relationship of Chinese foreign direct investment under the mega project of China–Pakistan Economic Corridor with the economic growth of Pakistan. Our results revealed that in the long run, to overcome the deficit of domestic resources at local level, Pakistan trying to overcome this deficiency through foreign direct investment to enhance economic growth, which further attracts more inward FDI into Pakistan. It can be concluded that the insignificant effect of Chinese FDI on the economic growth of Pakistan in the short run is due to the real challenges that Pakistan faces relating to access to credit and state capacity to sustain economic growth. Therefore, government should formulate policies for technologically demanding sectors for increasing exports.

1. Introduction

In the past few decades, the determinants of Economic growth have been the main focus, especially in developing countries. Investment in the form of foreign direct investment (hereafter FDI) is the engine of economic growth. FDI offers a high degree of financial resources, technology, and approach to foreign markets. FDI refers to the cross-border investments made by an organization of the investing country with the main purpose of obtaining long-term benefits in other countries (Shaikh et al., Citation2019). Various trade theories argued that a donor or investing country invests their funds (FDI) in the host country at a time when they understand that they have competitive advantages over local companies in the host country. Thangavelu et al. (Citation2009) argued that FDI creates a win–win situation for the host and investing country that gives the former external capital for maintaining economic growth level while the latter grabs the available foreign markets. Belloumi (Citation2014); Moran (Citation2005) demonstrate that foreign investors can bring managerial knowledge and skills, as well as new or advanced product and process technologies, which can help to increase the efficiency of the existing or new operations within the host country. The host country enjoys various benefits from FDI, it enhancing the growth rate of GDP and economic development (Rahman & Bakar, Citation2018), getting foreign capital without any risk (Belloumi, Citation2014; Demirhan & Masca, Citation2008), developing physical infrastructure, creating employment opportunities, managerial know-how of developed economies, and global market integrations (Tiwari & Mutascu, Citation2011). Further, Boateng et al. (Citation2017) documented that FDI inflow contributes positively towards the economic growth of the local country by investing in physical and human capital.

Prior researchers documented that economic growth and FDI attract the attention of academicians as well as the government of developing countries (Dinh et al. (Citation2019). Pakistan being a developing country has been struggling for sustainable high economic growth. For this purpose, different development projects are designed by policymakers to speed up economic growth. The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is one of them. Recently, China's investment under China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) aiming to connect central Asia, Africa, and Europe for trade and commerce was worth more than US$46 billion.Footnote1 The US$46 billion investments under CPEC exceed all the past FDI in Pakistan and are greater than the aid received from the US since 9/11 (Abid & Ashfaq, Citation2015). The initial US$46 billion investment under CPEC was raised to US$62 billion in 2017 (Boyce, Citation2017). World Investment Report in 2017 stated that FDI inflow in Pakistan increased by 56% due to CPEC investment. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reported that FDI in Pakistan reached $1.2 billion in 2015 and $ 2.1 billion in 2016 due to the rising investments of China in the shape of the CPEC project. For Pakistan, CPEC is a development strategy that is used as a source of potential synergy for attaining new level of success. All these allow us to contribute to the existing literature by testing the role of Chinese FDI (CFDI) under CPEC in economic growth from Pakistani context.

Given the growing inflows of FDI in the shape of CPEC into Pakistan and their perceived impact on different areas of an economy, the study contributes to the existing body of literature based on the following limitations/gaps. First, as prior researchers extensively studied the relationship of FDI with economic growth (Azman-Saini et al., Citation2010; Belloumi, Citation2014; Herzer, Citation2012; Qi, Citation2007; Srinivasan et al., Citation2011; Zaman et al., Citation2012), but their results are mixed and failed to provide conclusive results. Regarding inconclusive mixed results, some of the previous studies found a significantly positive effect of FDI on economic growth (Azman-Saini et al., Citation2010; Boateng et al., Citation2017; Erhieyovwe & Jimoh, Citation2016; Louzi & Abadi, Citation2011; Nwosa et al., Citation2011; Pegkas, Citation2015; Wang, Citation2009; Zaman et al., Citation2012). While some studies evidenced a negative association of FDI with economic growth (see, e.g, (Ahmad et al., Citation2012; Babalola et al., Citation2012; Herzer, Citation2012; Oyatoye et al., Citation2011). Wang (Citation2009) argued that mixed results in prior studies might be due to the use of total FDI instead of sector-level FDI. Moreover, due to the heterogeneous relation of FDI and Economic growth, a single country study is needed (Carbonell & Werner, Citation2018). Keeping this, we contribute to the literature by examining the relation of Chinese FDI under CPEC on the economic growth of Pakistan.

Second, despite the potential heterogeneity among the relationship of FDI with economic growth, most of the prior studies also suffer from empirical weaknesses. Elaborating further, Prior studies (i) failed to find the causal relationship between FDI and Economic growth in developing countries (Belloumi, Citation2014), (ii) used improper co-integration techniques that are not suitable for small sample size (Odhiambo, Citation2009), and (iii) failed to consider country-specific problems in their cross-sectional data (Ghirmay, Citation2004; Odhiambo, Citation2009). The rising inflows of FDI into Pakistan and its impact on Pakistan’s economy force many researchers to conduct studies in this context. However, most of the studies on Chinese FDI under CPEC considered policy associated issues (e.g., (A. Ahmed et al., Citation2017; Z. S. Ahmed, Citation2019; Ali et al., Citation2017; Babar & Zeeshan, Citation2018; Khan & Marwat, Citation2016; Kousar et al., Citation2018; McCartney, Citation2020; Shahzad & Javaid, Citation2020). Further, the reported studies are mostly qualitative, while the only known study that used quantitative technique (OLS) for the effect of Chinese FDI on Economic Growth (see e.g., (Mehar, Citation2017; Shahzad & Javaid, Citation2020). Based on this, our study is the first to empirically examine Chinese FDI under CPEC with economic growth by employing general to specific (GETS) econometric methodology of ARDL bounded co-integration approach developed by (Pesaran et al., Citation2001), previously used only by (Belloumi, Citation2014; Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006) for developing countries. Moreover, the GETS methodology is more suitable when the literature remains inconclusive (Carbonell & Werner, Citation2018).

Third, prior literature documented the importance of absorptive capacity of FDI to enhance economic growth (Carbonell & Werner, Citation2018), which depends on human capital and domestic financial markets (Alfaro et al., Citation2004), initial income, and trade openness (Herzer, Citation2012). As, Pakistan is a lower-middle-income country in South Asia,Footnote2 principally considered by relatively high economic growth, growing markets for various services and products, cheap labor forces, and numerous Greenfield investment opportunities (Sahoo, Citation2006; Sehrawat & Giri, Citation2016). Due to these characteristics, Pakistan is to be considered the most favorable for foreign investments. The present study strives to fill these gaps by analyzing the causality between Chinese investment under the CPEC project and economic growth in the context of Pakistan.

The following sections of this paper are arranged as follows: Section 2 highlights the theoretical and empirical literature; section 3 describes the estimation techniques and data used, section 4 provides the estimation results and section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature review

There is a strong belief among policymakers, academicians, economists, and other local and international institutions that FDI can play a major role in boosting the economic growth of the host country (Sokang, Citation2018). FDI comprises of the foreign funds’ investment in the host country that impact the host country’s GDP rate, trade balance, productivity, increasing labors skills, transfer of technologies and innovative ideas, and other business conditions. Agarwal (Citation1980) argued that FDI is the inflow of investment made by the foreign country in the host country in the form of financial assets, materials, labor, and technologies for the purpose to gain competitive advantages, reducing labor cost, gain new technologies, and expanding businesses in the host country. More specifically, FDI is transferring of capital from the foreign country to the host country either to invest in the existing company or establish a new company (M. Tahir & Alam, Citation2020; Unctad, Citation2010). Todaro and Smith (Citation2003) described that FDI is the investment made by Multinational Corporations (MNC’s) in the host countries. The inflow of FDI enable the host country to create new jobs, adopts new technology, expand market size and accelerate its economic growth (Dritsaki & Stiakakis, Citation2014; Tiwari & Mutascu, Citation2011). Overall, FDI is the major source of external financing for those economies whose domestic funds are inadequate to finance investment projects (M. Tahir & Alam, Citation2020).

2.1. Theoretical evidence

A review of the prior research work regarding FDI and its impact on economic growth provides theoretical and empirical background for the study. Many theories have been developed in connection with FDI and economic growth. Among these theories, exogenous growth theory and endogenous growth theory are very popular.

2.1.1. Exogenous growth theory

The exogenous growth theory states that capital accumulation or technological progress is important for the development process. The transfer of technology through FDI from foreign countries remains the main recommendation by international organizations for the countries to increase the growth (Blomström & Sjöholm, Citation1999). Empirical studies provide support for the exogenous growth theory that FDI benefits economic growth. Blomström and Sjöholm (Citation1999) found that FDI provides knowledge transfer effects on domestic firms. It is believed that FDI improves the communication and transport infrastructure of the host country and increases the level of human capital (Noorbakhsh et al., Citation2001), which leads to enhancing the growth of the economy (Mehar, Citation2017).

Based on the same notion, exogenous growth theory provides a base for the association between Chinese FDI and economic growth in Pakistan because all these Chinese FDI invested in human capital and technology in Pakistan to complete the mega project of CPEC. This mega project of CPEC from China brings prosperity to Pakistan (Haq & Farooq, Citation2016). Further, under CPEC, an extensive network of infrastructure in the form of highways, oil pipeline, railroads, power plants, economic zones, and optical fibers would be built from Kashgar in China to Gwadar in Pakistan (Kousar et al., Citation2018; Shoukat et al., Citation2016).Footnote3 Moreover, these extensive networks of infrastructure help to enhance trade opportunities (Kousar et al., Citation2018), increase per capita income (Mehar, Citation2017), get more social welfare (Haq & Farooq, Citation2016), create employment opportunities, and reduce transportation costs (McCartney, Citation2020), which will lead to economic prosperity in Pakistan (Kousar et al., Citation2018). Mehar (Citation2017) demonstrated that the policymakers recognized CPEC as the only way to rapidly increase the economic growth of Pakistan.

2.1.2. Endogenous growth theory

In 1986, Paul Romer developed endogenous growth theory. This theory stated that investment in human capital, technology, and knowledge through FDI in the host country plays a significant role in the economic growth of the host countries. Endogenous Growth theory suggests that FDI is a significant contributor to the long-run growth by generating positive returns in production through the spillover effect (Ford et al., Citation2008). This theory further argued that the economic growth of the local country depends on FDI, which is made on skillful and knowledge base employees, leading to higher levels of output and income. On the other hand, the investing country invests its funds in the local country in the form of FDI for low labor cost, high productivity, better marketing, and good managerial structures (Borensztein, De Gregorio, & Lee, Citation1998). Additionally, the positive relation of FDI with the economic growth of the host country requires trade openness, well-established financial markets, and an appropriate level of human resources (Malik, Citation2015).

Based on endogenous growth theory, the CPEC project will enhance economic growth with the view that internal factors strongly influence the economic growth of a country. Therefore, FDI from China to Pakistan extends the goods sector, viz., technology progress and enhances economic growth by reducing the cost of productivity through advanced knowledge.

2.1.3. Modern theory of international trade

The Modern theory of international trade, also known as Heckscher General Equilibrium state that a country gains competitive advantages through the factor of endowments (Heckscher & Ohlin, Citation1991). The factor of endowment refers to the amount of capital, land, the number of labor, and entrepreneurship that a country possesses and is used for manufacturing (Lenka & Sharma, Citation2014). According to this theory, a country is required to export those goods which it produces in large number and import those goods for which the country has scarce resources. Some countries have more machinery and technology, while others have more labor. The former will be required to produce technology-intensive products and the later will require to produce labor-intensive products. In such a case, both types of products (labor-intensive & technology-intensive) produced by all the countries will be required to export those goods in which they are experts in production.

This theory provides a base for the study, to investigate the association between Chinese FDI and economic growth in Pakistan. As, for the success of the CPEC, Pakistan has favorable factors like big markets with growing demand, ease of cheap labor, more land for construction, and good climatic condition (Mehar, Citation2017; Sahoo, Citation2006; Sehrawat & Giri, Citation2016; M. Tahir & Alam, Citation2020). Similarly, Ali et al. (Citation2017) argued that the Chinese government invest their FDI in Pakistan due to low labor cost. Therefore, in such a case China uses the labor-intensive strategy of the modern theory of international trade for completing the CPEC project.Footnote4

2.2. Empirical Literature and Hypothesis Development

An extensive amount of empirical work in the field of FDI concerning economic growth had been done internationally. Gherghina et al. (Citation2019) investigated the association between FDI and economic growth of eleven (11) Central and Eastern countries. They found a significantly positive relation between FDI and economic growth. Another study conducted by Kalai and Zghidi (Citation2019) in 15 countries of the Middle East and North Africa and found a direct relation between FDI and economic growth for the sampled countries. Similarly, Jyun-Yi and Chih-Chiang (Citation2008) examined that how economic growth and GDP rate are affected by the increasing inflow of FDI in 62 countries. They found a positive and significant relation between FDI and economic growth subject to a better level of human capital and initial GDP. Melnyk et al. (Citation2014) investigated FDI inflow and its impact on the economic growth of 26 post-communist transition economies. The finding of their study revealed a significant positive connection between FDI inflow and the host country’s GDP. From the African region, most of the researchers found a significant positive impact of FDI on economic growth (e.g., (Adam & Tweneboah, Citation2009; Babar & Zeeshan, Citation2018; Belloumi, Citation2014; Iddrisu et al., Citation2015; Juma, Citation2012; Okeke et al., Citation2014; Owusu-Antwi et al., Citation2013; Zekarias, Citation2016). Similarly, from the Asian region, researchers also found a positive relation between FDI and economic growth (Chowdhury & Mavrotas, Citation2006; Javaid, Citation2016; Malik, Citation2015; Sokang, Citation2018; Waikar et al., Citation2011; Wang, Citation2009).

From the Pakistani context, apart from general literature on the association between total FDI inflow and economic growth, more specifically, Chinese FDI under CPEC also attracts the attention of researchers around the globe. Haq and Farooq (Citation2016) demonstrate that Chinese FDI under CPEC brings prosperity in Pakistan that leads to improved economic growth. Likewise, Mehar (Citation2017) reported that the majority of Pakistani policymakers, analysts, and statesmen consider CPEC as an accelerator of Pakistan’s economic growth. Additionally, Chinese investments under CPEC can bring sustainable and long-term effects on the economic growth subject to human resource development (A. Ahmed et al., Citation2017). More recently, McCartney (Citation2020) theoretically pointed the effect of CPEC on economic development in Pakistan and argued that CPEC has a transformative effect that promotes growth effects on corporate logistics, reduces the distance to China, raises local cement production, and creates employment that leads to modest economic growth for Pakistan. Therefore, we hypothesize as:

H1: Chinese FDI under CPEC positively affects economic growth in Pakistan.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data

For the purpose of achieving the required objective, quarterly time series data ranging from 2009 to 2018 for all the study variables were obtained from different sources, such as the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), and (A. Tahir et al., Citation2018) who reported GDP quarterly data for Pakistan.

3.2. Analytical procedure

To empirically estimate the long-run relationship and short-run dynamics among Chinese FDI under CPEC and economic growth in Pakistan, the study used Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model (Pesaran & Shin, Citation1998; Pesaran et al., Citation2001). ARDL is a co-integration technique used to control endogeneity and omitted-variables bias in the long-run effect of Chinese FDI under CPEC (Herzer, Citation2012). Further, ARDL has three advantages over other co-integration techniques, that it is not necessary that all the variables be integrated in the same order, it is more appropriate for a small sample size, and provides long-run unbiased estimates (Belloumi, Citation2014; Harris & Sollis, Citation2003). To use the ARDL model, all the variables were screened for stationarity. For this purpose, we used Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test (developed by (Dickey & Fuller, Citation1979) based on Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) .

Where p is the lag order of the autoregressive process, determine by Schwarz information criterion (SIC). After carrying out the unit root test, the null hypothesis (has unit root) against the alternative hypothesis

(has no unit root) using test statistics in EquationEq.(2)

(2)

(2) be compared to the relevant critical values of the ADF test.

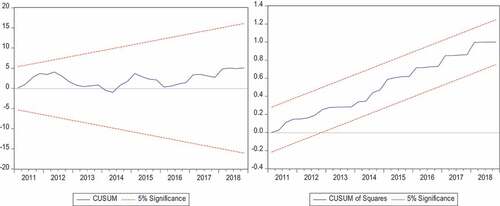

Additionally, all the diagnostics tests regarding normality (Jarque–Bera test), heteroscadaticity (White heteroscadaticity test), and serial correlation (Breusch–Godfrey test) were also applied. Moreover, for the stability of the estimated long-run coefficients and short-run dynamics, the cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and CUSUM of square (CUSUMSQ) test was also applied (Habib & Zurawicki, Citation2002; Pesaran & Pesaran, Citation1997; Pesaran & Shin, Citation1998).

Following prior researchers (Belloumi, Citation2014; Kumar Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006), we used the following econometric forms of ARDL time series models:

Where m and n are lags of the dependent and independent variables, respectively, is the difference operator, and

is the error term. EG is the economic growth proxy by the natural log of real GDP (at the constant basis of 2005–06) change in each successive period (Alfaro et al., Citation2004; Belloumi, Citation2014). CFDI is the Chinese FDI under CPEC calculated by total Chinese FDI to GDP (Musah et al., Citation2018; Pegkas, Citation2015; M. Tahir & Alam, Citation2020). INF is the rate of inflation (M. Tahir & Alam, Citation2020). GE is the government expenditure measured by total government expenditure as a percent of GDP (Alfaro et al., Citation2004). GDS is the gross domestic savings measured by gross domestic saving as a percent of GDP (Musah et al., Citation2018). GDS, GE, and INF are used in the model as determinants of economic growth and to overcome the problem of omitted variables bias. Summary statistics and Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) test results for all variables are presented in .

Table 1. Summary statistics and variance inflation factor (VIF) test

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Results of ADF unit root test

To test the stationarity status of all the variables, we used the conventional ADF test presented in EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) . The test is commonly used to determine, the unit root problem in time series data. Additionally, it also determines the level of integration for the ARDL bound test. reports the result of the ADF test at the level and first difference. It is evident from the results that the test statistics of all the variables are unable to reject the null hypothesis

, and conclude that at a level all the variables have unit root issues. Further, at the first difference, the null hypothesis is rejected for all the variables, indicating that our variables are stationary at first difference (i.e. integrated of order one, I (1)).

Table 2. Results of augmented Dickey–Fuller unit root test for all variables

4.2. ARDL bound test for co-integration

To scrutinize the long-run association and short-run dynamics amongst the study variables (EG, CFDI, GDS, GE, and INF), we used ARDL bound test approach (Allen & Fildes, Citation2001; Belloumi, Citation2014; Kumar Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006; Morley, Citation2006). The ARDL bound test expressed in EquationEq.(3)(3)

(3) to EquationEq. (7)

(7)

(7) were estimated for the long-run relationship amongst the variables through F-statistics and the joint significance of the null and alternate hypothesis through t-statistics, and the results were reported in .

Table 3. Results of ARDL bound test

Due to the short period, we choose a maximum lag of 1 based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) criteria. Additionally, also reported the critical values on the two assumptions of I(0) and I(1) at a given significance level of 1% and 5% (Pesaran et al., Citation2001). From , it is obvious that the value of F-statistic, as well as t-statistic for EquationEq. (3)(3)

(3) and EquationEq. (5

(5)

(5) –Equation7

(7)

(7) ), is smaller than the lower bound value. This means that we do not reject the null hypothesis of no co-integration and conclude that there exist short-run dynamic interactions amongst the variables in EquationEq. (3)

(3)

(3) and EquationEq.(5

(5)

(5) –Equation7

(7)

(7) ). Moreover, for EquationEq.(4)

(4)

(4) we are unable to reject the null hypothesis of no co-integration, because both calculated F-statistic and t-statistic value is higher than the upper bound critical values at 1% and 5% level, which indicates that a long-run relationship exists for EquationEq. (4)

(4)

(4) in Pakistan.

4.3. Results of granger causality

From the results of the ARDL Bound teppp-st, the equations where EC, GDS, GE, and INF are dependent variables were examined for granger causality without an error correction term, as the variables in these equations are not co-integrated. However, the equation, where CFDI is a dependent variable is co-integrated, and we examined it for granger causality with a lag of error correction term (Belloumi, Citation2014; Kumar Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006; Morley, Citation2006). Once the co-integrated is established for EquationEq. (4(4)

(4) ), we estimated ARDL (p, q, r, s and u) for the long run EquationEq. (8)

(8)

(8) through OLS and the results are presented in .

Table 4. ARDL long-run relationship

illustrates the results of normalized CFDI in the long run. EquationEq.(8)(8)

(8) is estimated using AIC criteria for lag selection with specification ARDL (2,0,0,0,0). The coefficient of economic growth is positively significant at 5% level. This result shows that enhanced economic growth attracts more FDI in Pakistan. Our results are consistent with the notion of exogenous growth theory and prior studies, that economic growth prospects made the country more attractive to foreign investors (Broadman & Sun, Citation1997; Liu et al., Citation2002). This result is also in line with the findings of Chakraborty and Basu (Citation2002); Chowdhury and Mavrotas (Citation2006), who suggest that economic growth positively cause FDI. Similarly, the coefficients of GDS and GE are positively significant with CFDI, indicating that growing government savings and increase of government expenditure on infrastructure development stimulate the inflow of foreign investment to Pakistan. The positive relation of GE with CFDI is in line with the findings of Othman et al. (Citation2018), who documented that government expenditure, contributes positively towards FDI in the long run. Similarly, the positive effect of GDS on CFDI is consistent with the prior studies (Aghion et al., Citation2016; Chani et al., Citation2010). The coefficient of INF is negatively significant with CFDI at a 1% level. It indicates that the inflation rate in Pakistan discourages the inflow of foreign direct investment. This result is consistent with the view of Agudze and Ibhagui (Citation2021), who argued that the impact of inflation on FDI is negative in emerging economies.

For granger causality, we followed (Belloumi, Citation2014; Kumar Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006; Morley, Citation2006), and the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) in matrix form as follows:

Based on Granger Theorem, the long-run relationship for the equation where CFDI is a dependent variable illustrates that there is Granger causality in at least one direction shown by the t-statistic of and F-statistics of the explanatory variables (Belloumi, Citation2014; Kumar Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006). reports the results of long and short-run Granger causality for EquationEq. (4)

(4)

(4) . The short-run Granger causality effect is shown by the F-statistics on the explanatory variables and the long-run causality effect is represented by the t-statistic of the lag value of error correction term (Belloumi, Citation2014; Kumar Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006; Odhiambo, Citation2009). For the short run, the values of F-statistics show that there is a bi-directional Granger causality among EG and INF and unidirectional Granger causality runs from EG to CFDI, from GE to CFDI, from EG to GDS, from CFDI to GDS, and from CFDI to INF. There is no Granger causality between GE and GDS, and between GE and INF. In the short run, our results failed to establish causality from CFDI to EG supporting the notion of prior researchers that foreign investment eliminates domestic firms (Alaya et al., Citation2006; Belloumi, Citation2014). Belloumi (Citation2014) argued that multinational firms create positive spillovers through labor mobility channels for domestic firms. As Pakistan is a lower-middle-income country, and our distant history shows the significance of implementing industrial policy alongside CPEC in order to make sure that increasing inflow of Chinese FDI in the shape of CPEC infrastructure projects cannot create positive spillovers for domestic firms. However, in the long run, enhanced economic growth attracts more FDI in Pakistan. Our results are consistent with the notion of exogenous growth theory that capital accumulation and technological progress are important for the development process. Therefore, with a deficit of domestic resources at local level, countries try to overcome their deficiency through foreign debt financing or FDI to enhance growth rate, which further attracts more inward FDI (Hansen and Rand, Citation2006).

Table 7. Results of short-run granger causality

Table 5. Results of problem diagnostics

The coefficient of is negative and significant statistically at the 5% level. It confirms the results of the bound test of co-integration and shows that the adjustment speed for the equilibrium after a shock is too high. The coefficient of

implies that any deviation from the equilibrium due to the shock of the prior year adjusted by 70% in the current year. This result is almost similar to the result of (Belloumi, Citation2014).

4.4. Model Diagnostics and parameter Stability

Following Belloumi (Citation2014); Kumar Narayan and Smyth (Citation2006), the Eq. (10) with long-run relationship and error correction term is also passed through model diagnostics and parameter stability tests. Table 8 reports the results of diagnostic tests such as Breusch–Godfrey LM test for Serial Correlation, Jarque-Bera test for normality, White test for heteroscadaticity, and Chow Breakpoint test for structural breaks in 2015. We took the year 2015 as a breakpoint because the inflows of Chinese investments under CPEC are high this year. From the results, it is clear that the P-values of all the diagnostic tests are insignificant at a 5% significant level, indicating that all the diagnostic tests pass the model against normality test, serial correlation, heteroscadaticity, and structural breaks. Thus, the results of diagnostic tests concluded that this research has economic significance and is reasonable as well (Stock & Watson, Citation2015).

To check the long-run stability of Eq. (10), we used Cumulative Sum (CUSUM) and Cumulative Sum of Squares (CUSUMSQ) test ((Brown et al., Citation1975). Prior researchers argued that parameter stability test is necessary as unstable parameters lead to model misspecification that biased the results (Kumar Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006). Following prior studies (Belloumi, Citation2014; Habib & Zurawicki, Citation2002; Kumar Narayan & Smyth, Citation2006; Pesaran & Shin, Citation1998), shows the graph of CUSUM and CUSUMSQ. From , it is clear that the graph of CUSUM and CUSUMSQ stays within 5% critical bound, which confirms the stability of the long-run coefficients.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

In the last few decades, developing countries tried to attract FDI and expand their local markets and businesses. In this regard, Pakistan received a fair share of FDI since the inception of CPEC. The main focus of the study was to investigate the dynamic causality between Chinese FDI under CPEC and economic growth in Pakistan. For this purpose, we applied the ARDL bound test of co-integration for the existence of a long-run relationship between EG, CFDI, GDS, GE, and INF. Our results are two fold; first, we found that EG, CFDI, GDS, GE, and INF are co-integrated when CFDI is used as dependent variables, while there is no co-integration when either of the other variables is used as the dependent variable. Second, for the short run, there is a bi-directional Granger causality among EG and INF and unidirectional Granger causality runs from EG to CFDI, from GE to CFDI, from EG to GDS, from CFDI to GDS, and from CFDI to INF. There is no Granger causality between GE and GDS, and between GE and INF. In the short run, our results failed to establish causality from CFDI to EG supporting the notion of prior researchers that foreign investment eliminates domestic firms, thus creating positive spillovers through labor mobility channels. However, in the long run, enhanced economic growth attracts more FDI in Pakistan. Our results are consistent with the notion of exogenous growth theory that capital accumulation and technological progress are important for the development process. Therefore, with a deficit of domestic resources at a local level, countries are trying to overcome this deficiency through foreign debt financing or FDI to enhance growth rate, which further attracts more inward FDI.

Our results have important implications for economists and policymakers to make policies alongside CPEC to ensure that the potential spillovers from the inflow of Chinese FDI in the shape of CPEC infrastructure projects create domestic spillover. Our results are also beneficial for the Pakistan investment board (PIB) to manage and better use these large investments in the local market businesses and in order to bring prosperity to Pakistan. It can be concluded that the insignificant effect of Chinese FDI on the economic growth of Pakistan in the short run is due to the real challenges that Pakistan faces relating to access to credit and state capacity to sustain economic growth. Therefore, government should formulate policies for technologically demanding sectors for increasing exports.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sabeeh Ullah

Dr. Sabeeh Ullah, is an Assistant Professor of finance in the Institute of Business & Management Sciences (IBMS), Faculty of Management & Computer Sciences (FM&CS), The University of Agricultural Peshawar, Pakistan. His research interest includes Stock markets, corporate finance, corporate governance and financial econometrics.

Dr. Shahzad Hussain, is an Assistant Professor at Foundation University Islamabad (FUI), Pakistan. His research interest includes Corporate Finance and Financial Economics.

Budi Rustandi Kartawinata, is working in the Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Communication and Business, Telkom University, Bandung, Indonesia.

Zia Muhammmad, was a Master of Science (MS) student in the Institute of Business & Management Sciences (IBMS), The University of Agricultural Peshawar, Pakistan.

Rosa Fitriana, is a Lecturer in the Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics Universitas Bale Bandung, Bandung, Indonesia.

Notes

1. In May 2013, Chinese premier Li Keqiang signed the landmark CPEC agreement. Subsequently in April 2015, in a visit to Pakistan, Chinese President Xi Jinping signed investments agreements under CPEC worth US$46 billion.

2. According to the World Bank list of economies (June 2020).

3. Pakistan is placed at 100th in the overall infrastructure quality (Mehar, Citation2017)

4. According to Magsi (Citation2016), Pakistan ranked the 10th largest country in the world by the size of the labour force.

References

- Abid, M., & Ashfaq, A. (2015). CPEC: Challenges and opportunities for Pakistan. Journal of Pakistan Vision, 16(2), 142–18.

- Adam, A. M., & Tweneboah, G. (2009). Foreign direct investment and stock market development: Ghana’s evidence. International Research Journal of Finance Economics, 26, 178–185.

- Agarwal, J. P. (1980). Determinants of foreign direct investment: A survey. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 116(4), 739–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02696547

- Aghion, P., Comin, D., Howitt, P., & Tecu, I. (2016). When does domestic savings matter for economic growth? IMF Economic Review, 64(3), 381–407. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2015.41

- Agudze, K., & Ibhagui, O. (2021). Inflation and FDI in industrialized and developing economies. International Review of Applied Economics 35(5), 749–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2020.1853683

- Ahmad, N., Hayat, M. F., Luqman, M., & Ullah, S. (2012). The causal links between foreign direct investment and economic growth in Pakistan. European Journal of Business and Economics, 6, 20–21. https://doi.org/10.12955/ejbe.v6i0.137

- Ahmed, Z. S. (2019). Impact of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor on nation-building in Pakistan. Journal of Contemporary China, 28(117), 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1542221

- Ahmed, A., Arshad, M. A., Mahmood, A., & Akhtar, S. (2017). Neglecting human resource development in OBOR, a case of the China–Pakistan economic corridor (CPEC). Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies, 10(2), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCEFTS-08-2016-0023

- Alaya, M., Nouira, K., Ben Reguigua, M., Bedioui, H., Oueslati, S., Laabidi, B., Alaya, M., & Ben Abdallah, N. (2006). Investissement direct étranger et croissance économique: Une estimation à partir d’un modèle structurel pour les pays de la rive sud de la Méditerranée. Gastroenterologie Clinique Et Biologique, 30(2), 317–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73174-8

- Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Sayek, S. (2004). FDI and economic growth: The role of local financial markets. Journal of International Economics, 64(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(03)00081-3

- Ali, S. A., Haider, J., Ali, M., Ali, S. I., & Ming, X. (2017). Emerging tourism between Pakistan and China: Tourism opportunities via China-Pakistan economic corridor. International Business Research, 10(8), 204. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v10n8p204

- Allen, P. G., & Fildes, R. (2001). Econometric forecasting. In Principles of forecasting (pp. 303–362). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Azman-Saini, W., Baharumshah, A. Z., & Law, S. H. (2010). Foreign direct investment, economic freedom and economic growth: International evidence. Economic Modelling, 27(5), 1079–1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2010.04.001

- Babalola, S. J., Dogon-Daji, S. D. H., & Saka, J. O. (2012). Exports, foreign direct investment and economic growth: An empirical application for Nigeria. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(4), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v4n4p95

- Babar, S. F., & Zeeshan, Y. (2018). Financial institutions and Chinese investment: The review of China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Policy. European Journal of Economics and Business Studies, 4(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejes.v4i2.p73-82

- Belloumi, M. (2014). The relationship between trade, FDI and economic growth in Tunisia: An application of the autoregressive distributed lag model. Economic Systems, 38(2), 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2013.09.002

- Blomström, M., & Sjöholm, F. (1999). Technology transfer and spillovers: Does local participation with multinationals matter? European Economic Review, 43(4–6), 915–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00104-4

- Boateng, E., Amponsah, M., & Annor Baah, C. (2017). Complementarity effect of financial development and FDI on investment in Sub‐Saharan Africa: A panel data analysis. African Development Review, 29(2), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12258

- Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J. W. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of international Economics, 45(1), 115–35.

- Boyce, T. (2017). China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Trade security and regional implications. SANDIA Report SAND 2017, 207.

- Broadman, H. G., & Sun, X. (1997). The distribution of foreign direct investment in China. World Bank Publications.

- Brown, R. L., Durbin, J., & Evans, J. M. (1975). Techniques for testing the constancy of regression relationships over time. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 37(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1975.tb01532.x

- Carbonell, B. J., & Werner, R. A. (2018). Does foreign direct investment generate economic growth? A new empirical approach applied to Spain. Economic Geography, 94(4), 425–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1393312

- Chakraborty, C., & Basu, P. (2002). Foreign direct investment and growth in India: A cointegration approach. Applied Economics, 34(9), 1061–1073. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840110074079

- Chani, D., Irfan, M., Salahuddin, M., & Shahbaz, M. Q. (2010). A note on causal relationship between FDI and savings in Bangladesh. Theoretical Applied Economics, 17(11), 53–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1735667

- Chowdhury, A., & Mavrotas, G. (2006). FDI and growth: What causes what? World Economy, 29(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2006.00755.x

- Chowdhury, A., & Mavrotas, G. (2006). FDI and growth: what causes what? World economy, 29(1), 9–19.

- Chowdhury, A., & Mavrotas, G. (2006b). FDI and growth: What causes what? The World Economy, 29(1), 9–19.

- Demirhan, E., & Masca, M. (2008). Determinants of foreign direct investment flows to developing countries: A cross-sectional analysis. Prague Economic Papers, 4(4), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.pep.337

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366a), 427–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1979.10482531

- Dinh, T. T.-H., Vo, D. H., & Nguyen, T. C. (2019). Foreign direct investment and economic growth in the short run and long run: Empirical evidence from developing countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(4), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040176

- Dritsaki, C., & Stiakakis, E. (2014). Foreign direct investments, exports, and economic growth in Croatia: A time series analysis. Procedia Economics Finance, 14, 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00701-1

- Erhieyovwe, E. K., & Jimoh, E. S. (2016). Foreign direct investment granger and Nigerian growth. Journal of Innovative Research in Management and Humanities, 3(2), 132–139.

- Ford, T. C., Rork, J. C., & Elmslie, B. T. (2008). Foreign direct investment, economic growth, and the human capital threshold: Evidence from US states. Review of International Economics, 16(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2007.00726.x

- Gherghina, Ș. C., Simionescu, L. N., & Hudea, O. S. (2019). Exploring foreign direct investment–economic growth nexus—Empirical evidence from central and Eastern European countries. Sustainability, 11(19), 5421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195421

- Ghirmay, T. (2004). Financial development and economic growth in Sub‐Saharan African countries: Evidence from time series analysis. African Development Review, 16(3), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1017-6772.2004.00098.x

- Habib, M., & Zurawicki, L. (2002). Corruption and foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8491017

- Hansen, H., & Rand, J. (2006). On the causal links between FDI and growth in developing countries. World Economy, 29(1), 21–41.

- Haq, R., & Farooq, N. (2016). Impact of CPEC on social welfare in Pakistan: A district level analysis. The Pakistan Development Review, 597–618.

- Harris, R., & Sollis, R. (2003). Applied time series modelling and forecasting. Wiley.

- Heckscher, E. F., & Ohlin, B. G. (1991). Heckscher-Ohlin trade theory. The MIT Press.

- Herzer, D. (2012). How does foreign direct investment really affect developing countries’ growth? Review of International Economics, 20(2), 396–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2012.01029.x

- Iddrisu, -A.-A., Adam, B., & Halidu, B. O. (2015). The influence of foreign direct investment (FDI) on the productivity of the industrial sector in Ghana. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 5(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARAFMS/v5-i3/1736

- Javaid, W. (2016). Impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth of Pakistan-An ARDL-ECM approach. School of Social Sciences, Södertörn University. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:sh:diva-30524.

- Juma, M.-A. (2012). The effect of foreign direct investment on growth in Sub-Saharan Africa (Doctoral dissertation, Amherst College). https://www.amherst.edu/media/view/434456

- Jyun-Yi, W., & Chih-Chiang, H. (2008). Does foreign direct investment promote economic growth? Evidence from a threshold regression analysis. Economics Bulletin, 15(12), 1–10. http://economicsbulletin.vanderbilt.edu/2008/volume15/EB-08O10014A.pdf

- Kalai, M., & Zghidi, N. (2019). Foreign direct investment, trade, and economic growth in MENA countries: Empirical analysis using ARDL bounds testing approach. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 10(1), 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-017-0460-6

- Khan, S. A., & Marwat, Z. A. K. (2016). CPEC: Role in regional integration and peace. South Asian Studies, 31(2), 103.

- Kousar, S., Rehman, A., Zafar, M., Ali, K., & Nasir, N. (2018). China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: A gateway to sustainable economic development. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(6), 909–924. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-02-2017-0059

- Lenka, S. K., & Sharma, P. (2014). FDI as a main determinant of economic growth: A panel data analysis. Annual Research Journal of Symbiosis Centre for Management Studies, Pune, 1, 84–97.

- Liu, X., Burridge, P., & Sinclair, P. J. (2002). Relationships between economic growth, foreign direct investment and trade: Evidence from China. Applied Economics, 34(11), 1433–1440. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840110100835

- Louzi, B. M., & Abadi, A. (2011). The impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth in Jordan. IJRRAS-International Journal of Research Reviews in Applied Sciences, 8(2), 253–258.

- Magsi, H. (2016). China-Pakistan economic corridor and challenges of quality labor-force. The Diplomatic Insight, 91.

- Malik, K. (2015). Impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth of Pakistan. American Journal of Business Management, 4(4), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.11634/216796061706624

- McCartney, M. (2020). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC): Infrastructure, social savings, spillovers, and economic growth in Pakistan. Eurasian Geography Economics, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1836986

- Mehar, A. (2017). Infrastructure development, CPEC and FDI in Pakistan: Is there any connection? Transnational Corporations Review, 9(3), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2017.1362857

- Melnyk, L., Kubatko, O., & Pysarenko, S. (2014). The impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth: Case of post communism transition economies. Problems Perspectives in Management, 12(1), 17–24. http://essuir.sumdu.edu.ua/handle/123456789/66749

- Moran, T. H. (2005). How does FDI affect host country development? Using industry case studies to make reliable generalizations. Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Development, 281–313. https://www.piie.com/publications/chapters_preview/3810/11iie3810.pd

- Morley, B. (2006). Causality between economic growth and immigration: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Economics Letters, 90(1), 72–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2005.07.008

- Musah, A., Gakpetor, E. D., Kyei, S. N. K., & Akomeah, E. (2018). Foreign direct investment (FDI), Economic growth and bank performance in Ghana. International Journal of Finance and Accounting, 7(4), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijfa.20180704.02

- Narayan, P., & Smyth, R. (2006). Higher education, real income and real investment in China: Evidence from Granger causality tests. Education Economics, 14(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645290500481931

- Noorbakhsh, F., Paloni, A., & Youssef, A. (2001). Human capital and FDI inflows to developing countries: New empirical evidence. World Development, 29(9), 1593–1610. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00054-7

- Nwosa, P. I., Agbeluyi, A. M., & Saibu, O. M. (2011). Causal relationships between financial development, foreign direct investment and economic growth the case of Nigeria. International Journal of Business Administration, 2(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijba.v2n4p93

- Odhiambo, N. M. (2009). Finance-growth-poverty nexus in South Africa: A dynamic causality linkage. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(2), 320–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2008.12.006

- Okeke, R. C., Ezeabasili, V. N., & Nwakoby, C. N. I. (2014). Foreign direct investment and economic growth in Nigeria: An empirical evidence. International Journal of Innovative Research in Management, 3(3), 30–39.

- Othman, N., Yusop, Z., Andaman, G., & Ismail, M. M. (2018). Impact of government spending on FDI inflows: The case of Asean-5, China and India. International Journal of Business Society, 19(2), 401–414.

- Owusu-Antwi, G., Antwi, J., & Poku, P. K. (2013). Foreign direct investment: A journey to economic growth in Ghana-empirical evidence. International Business and Economics Research Journal, 12(5), 573–584 doi:10.19030/iber.v12i5.7832.

- Oyatoye, E., Arogundade, K., Adebisi, S., & Oluwakayode, E. (2011). Foreign direct investment, export and economic growth in Nigeria European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 2(1), 66-86 .

- Pegkas, P. (2015). The impact of FDI on economic growth in Eurozone countries. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 12(2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeca.2015.05.001

- Pesaran, M. H., & Pesaran, B. (1997). Working with microfit 4.0. Camfit Data Ltd, Cambridge.

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1998). An autoregressive distributed-lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Econometric Society Monographs, 31, 371–413.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Qi, L. (2007). The relationship between growth, total investment and inward FDI: Evidence from time series data. International Review of Applied Economics, 21(1), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692170601035058

- Rahman, S., & Bakar, N. (2018). A review of foreign direct investment and manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 6(4), 582–599. https://doi.org/10.52131/pjhss.2018.0604.0065

- Sahoo, P. (2006). Foreign direct investment in South Asia: Policy, trends, impact and determinants.(No. 56). ADBI Discussion Paper. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/53445.

- Sehrawat, M., & Giri, A. (2016). Financial development, poverty and rural-urban income inequality: Evidence from South Asian countries. Quality and Quantity, 50(2), 577–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0164–6

- Shahzad, M. K., & Javaid, U. (2020). Strategic significance of CPEC: A game changer for Pakistan. Journal of Political Studies, 27(1 107–117 http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/pols/pdf-files/7-v27_2_20.pdf).

- Shaikh, E. K. Z., Shaikh, N., & Mirza, A. (2019). Impact of GDP growth rate and inflation on the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Pakistan. Asia Pacific-Annual Research Journal of Far East and South East Asia, 35 160–172 https://sujo-old.usindh.edu.pk/index.php/ASIA-PACIFIC/article/view/5045 .

- Shoukat, A., Ahmad, K., & Abdullah, M. (2016). Does infrastructure development promote regional economic integration? CPEC’s implications for Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review, 455–467 https://www.jstor.org/stable/44986499.

- Sokang, K. (2018). The impact of foreign direct investment on the economic growth in Cambodia: Empirical evidence. International Journal of Innovation and Economics Development, 4(5), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.18775/ijied.1849-7551-7020.2015.45.2003

- Srinivasan, P., Kalaivani, M., & Ibrahim, P. (2011). An empirical investigation of foreign direct investment and economic growth in SAARC nations. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 5(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/15587891111152366

- Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (2015). Introduction to econometrics (3rd Updated Edition). 3(0.22).

- Tahir, A., Ahmed, J., & Ahmed, W. (2018). Robust quarterization of GDP and determination of business cycle dates for IGC partner countries. Retrieved from (No. 97). State Bank of Pakistan.

- Tahir, M., & Alam, M. B. (2020). Does good banking performance attract FDI? Empirical evidence from the SAARC economies. International Journal of Emerging Markets 17 (2), 413-432 . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-04-2020-0441

- Thangavelu, S. M., Wei Yong, Y., & Chongvilaivan, A. (2009). FDI, growth and the Asian financial crisis: The experience of selected Asian countries. World Economy, 32(10), 1461–1477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01202.x

- Tiwari, A. K., & Mutascu, M. (2011). Economic growth and FDI in Asia: A panel-data approach. Economic Analysis and Policy, 41(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0313-5926(11)50018-9

- Todaro, M. P., & Smith, S. C. (2003). Human capital: Education and health in economic development. Economic Development. United Kingdom.

- Unctad, W. (2010). World Investment Report 2010: Investing in a low-carbon economy. Paper presented at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION, New York and Geneva.

- Waikar, A., Jepbarova, L., Lee, S., Gardner, L., & Johnson, J. (2011). ’Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Kazakhstan’s Economy: A Boon or a Curse’. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(22), 92–98 https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lara-Gardner-3/publication/260136865.

- Wang, M. (2009). Manufacturing FDI and economic growth: Evidence from Asian economies. Applied Economics, 41(8), 991–1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840601019059

- Zaman, K., Shah, I. A., Khan, M. M., & Ahmad, M. (2012). Macroeconomic factors determining FDI impact on Pakistan’s growth. South Asian Journal of Global Business Research, 1(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1108/20454451211207598

- Zekarias, S. M. (2016). The impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on economic growth in Eastern Africa: Evidence from panel data analysis. Applied Economics and Finance, 3(1), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.11114/aef.v3i1.1317