Abstract

This study considers the relationship of the tour operators to the tourism platform services in the context of a COVID-19 post-pandemic recovery. The findings are based on semi-structured interviews with representatives of Slovak tour operators’ businesses. The results show that the platform economy is not perceived as a poison for the industry. Specialised tour operators are less open to potential cooperation than organisations with the mass product, which are especially likely to use platform information and incorporate platform food-related services into packagded tours enriched with authentic experiences. Platform economy thus presents for willing tour operators a chance to differentiate themselves, open uncontested market space and survive in a competitive post-pandemic period. In this context, legislation development is required.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The paper introduces a theoretical framework that connects seemingly incoherent themes of tour operators and the platform economy. It extends the existing limited literature focusing on the influence of tour operators on sustainable development based on more rational consumption. Moreover, it fills a gap in the literature dedicated to the possibilities of COVID-19 recovery, highlighting opportunities for reimagined tour operators.

The findings are based on interviews with representatives of Slovak tour operators’ businesses. The results show that the platform economy is not perceived as a poison for the industry. Specialised tour operators are less open to potential cooperation than organisations with the mass product, which are especially likely to use platform information and incorporate platform food-related services into packaged tours enriched with authentic experiences.

1. Introduction

The unfettered global tourism development period has ended with COVID-19 (Brouder, Citation2020), declared a pandemic by WHO, 12 March 2020. Lim (Citation2021a) notes that unlike many other pandemics (e.g., H1N1, MERS, SARS), the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the Earth like no other—primarily due to its multinational presence and reach. The health communication strategies and measures have paused global travel, tourism, and leisure (Sigala, Citation2020) and brought the sector to a near standstill (Brouder, Citation2020; Wen et al., Citation2020). As Lim (Citation2021b) states, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, undertourism (a legitimate but under-researched phenomenon in tourism) manifested itself in the form of a crippling tourism industry that was triggered by closure orders issued by governments around the world. According to UNWTO (Citation2021), the overwhelming influence of COVID-19 on tourism has carried forward into 2021, with new data showing an 85% collapse in international tourist arrivals in the first quarter of 2021 over the same period in 2019, which signify a decrease of 260 million international arrivals and millions of jobs when compared to pre-pandemic levels. Thus, it is essential to have a well-thought-out tourism crisis and disaster management to mitigate the effect and support post-crisis recovery (Yeh, Citation2021).

Instead of identifying tourism as a passive victim, experts (e.g., Mostafanezhad, Citation2020; Sigala, Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2020) unanimously suggested that the pandemic should be perceived as an unprecedented opportunity to transform tourism into more sustainable and resilient development. To emerge from the COVID-19 crisis stronger, safer, and more sustainable, an accelerated transformation of existing business and destination practices targeting sustainability and digitalisation is required (The European Tourism Manifesto alliance, Citation2021). It also includes tour operators (TOs), which are among the organizations most affected by this crisis (Kvítková & Petru, Citation2021).

As Montes (Citation2020) claims, the tour and activity industry are the third-largest travel sub-industry after flights and hotels. As a result of this pandemic, TOs sales have dramatically fallen (for example, in Slovak market, a decrease of 90 to 95 per cent in 2020 compared to 2019 was recorded). Although TOs played a crucial role in facilitating tourist demand and tourism destination development (Holland & Leslie, Citation2018), they are currently facing the most turbulent era in modern history. How the TOs will handle this situation, how many of them will survive, change their business focus, or modify their product is largely unknown today. As our knowledge and understanding of TOs are not yet proportionate with the economic and social significance of the phenomenon (Dhiman & Kumar, Citation2019), we are interested in the possibilities of reimagining TOs organisations by a sustainable and digitalised imperative.

The framework covering these requirements is the platform economy (also called collaborative, sharing, peer-to-peer, on-demand, or the access economy),Footnote1 altering how individuals handle transactions in connective digital realms, catalysing innovative ways of community involvement (Scott et al., Citation2020). As there is no examination in available literature of potential cooperation between TOs and platform tourism services providers in general, we find and fill this research gap and find out whether the platform economy is for TOs a cure allowing them to bridge the post pandemic period or, contradictory, a poisoning acceleration of their decline.

The paper is organised as follows. First, the theoretical basis of the researched issues will be approached, focusing on the role of TOs in the development of sustainable tourism and the challenges posed by the platform economy. Subsequently, a research methodology based on an interview method is advanced. The Findings and discussion section focuses on interpreting the results of interviews with TOs representatives. It reveals the perception of the future of the TOs after the COVID-19 pandemic, draws attention to the relationship of the TOs to platform tourism services, and offers a discussion in which the results of the research are confronted with the outputs of international literature. The conclusion also includes study limitations, theoretical and managerial contributions, and directions for future research.

2. Literature review

TOs play a crucial role with connecting visitors to tourism destinations by designing, organising, packaging, marketing, and operating tourism resources. Due to the widespread influence, they have on consumers, individual services producers and even destinations, the TOs also act as a significant stakeholder and could be involved in leading the industry toward sustainability (Budeanu, Citation2005; Lin et al., Citation2018; Sigala, Citation2008; Van Wijk & Persoon, Citation2006). The importance of TOs concerning their responsibility for the proper performance of the offered product, consisting of several producents services, is explicitly underlined in the European Union framework by Directive (EU) 2015/2302 on package travel and linked travel arrangements that impact not merely EU countries, but also non-EU countries receiving EU travellers.

In the context of sustainability issues, Budeanu (Citation2005), Sigala (Citation2008), and Ibarnia et al. (Citation2020) discuss the meaning of TOs with the integration of sustainability in the tourism supply chains. As the authors claim, TOs can affect the diffusion of tourists in destinations. They can also support and initiate suppliers’ activities towards the co-development of sustainable tourism, mainly by contracting and comprising package tours to only suppliers adhering to sustainability principles. TOs should also educate their clients on the destinations’ environmental and socio-cultural sensitivities, including potential impacts of their consumption, and advise them on how to avoid negative influences on the environment and communities. Hence, as Ibarnia et al. (Citation2020) argue, TOs should above all play a role of professional information intermediaries, particularly when exclusive and specialized experiences are involved. In this regard, Yusoff et al. (Citation2013), Pompurová and Marčeková (Citation2017), McNicol and Rettie (Citation2018), and Zahari et al. (Citation2020) highlight alternative TOs products like gastronomy tourism, volunteer tourism or ecotourism.

The most noticeable activity concerning the assumption of responsibility of TOs for sustainable development is the former Tour Operators Initiative for Sustainable Tourism Development, advanced by TOs internationally with the support of UNEP, UNESCO and UNWTO. The Initiative encourages TOs to improve and report their sustainability activities, manage their supply chain, and cooperate with destinations (Budeanu, Citation2005; Van Wijk & Persoon, Citation2006).

Despite the undeniable potential of TOs to become one of the key players in promoting sustainable tourism, Van Wijk and Persoon (Citation2006) conclude that in comparison to other industry sectors, TOs performance has been weak, which may be related to the attitude of TOs managers (Lin et al., Citation2018). As Budeanu (Citation2005) suggests, the frequent argument of TOs against the idea of being proactive in offering products that are less damaging for environments and societies is the low consumer demand for such products and their unwillingness to pay for the extra costs connected with sustainability implementation.

Boreli & Bernardi (2019) emphasise that the idea of making tourism more sustainable at low costs finds at present a new ally in the spread of ICT. As the authors state, the internet-based booking platforms matching supply and demand enable the extent of unconventional tourist products that appear “more sustainable, low-impact, and respectful of the environment and the local communities than the traditional tourist offer” (Boreli & Bernardi, 2019, p. 31). As the authors state, this kind of triangulation ˗ tourism, sustainability, platform economy ˗ is also presenting new challenges to TOs. The latter can no longer ignore the influence of the platform economy on the tourism sector and should try to understand the phenomenon better and perform specific strategies to undertake sustainability goals and sustain their position in the market, especially in the context of a post-pandemic recovery.

Although some scholars question the sustainability of the platform economy, particularly in accommodations in popular urban destinations, according to Zhu and Liu (Citation2020), most are persuaded of the sustainable value of this concept, underlined by the rationalisation of individual consumption. Thus, there is no transformation in the ownership between supply and demand, but the simple allowing of a transitory right of access to selected underused or unwanted commodities mediated by digital technologies (European Commission, Citation2016; Jorge-Vázquez, Citation2019; Scott et al., Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2017). As mentioned by UNWTO (Citation2017, p. 10), “these new business models have a significant potential to offer innovative services, often at lower prices, creating new products, employment opportunities and sources of income, as well as a more efficient use of resources”.

According to some scholars, the business model is characterised by environmental and social responsiveness (De Las Heras et al., Citation2021; Peña-Vinces et al., Citation2020; Serrano et al., Citation2020; Zhu & Liu, Citation2020), trust to members of the platform’s community (Belk, Citation2014; Popescu & Ciurlău, Citation2019), the duality of concept that can be commercial or non-commercial (Klarin & Suseno, Citation2021), but, so far, has imprecise legislative boundaries (Chen et al., Citation2021; European Commission, Citation2016; Scott et al., Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2020; Zhu, Citation2020), which disadvantages traditional businesses.

The platform economy is expeditiously changing dynamics of the labour market (Hoang et al., Citation2020). Faced with the platform economy, the traditional organizations fear change, as they might become less relevant or even obsolete and may need to adapt to survive. However, the platform economy is not necessarily a threat, which was proved by the first and so far, the only survey aimed at determining the willingness and degree of cooperation between traditional tourism organisations, namely TOs, with providers of platform accommodation services through the Airbnb portal (Pastor & Rivera García, Citation2020). Although new platform tourism services are often in competition with traditional businesses, there might be circumstances where the supply of these services can bring benefits to all subjects from the opportunities generated. As UNWTO (Citation2017) further argues, in some cases, privately offered services can provide additional enrichments to the tourism experience, that traditional providers cannot deliver. Moreover, there are further occasions for platform information services use. Customer feedback can help identify fragile spots in conventional business, and consequently, turn feebleness into strengths if adequately managed. Furthermore, positive feedback can help to motivate both entrepreneurs and staff. By increasing collaboration efforts, established tourism operators can work together with platforms to mutually benefit from the opportunities generated. The platform studies supply a framework for examining the construction of authenticity in travel writing considering specific structural influences related to the publication and dissemination of information online. This makes it possible to explore how firmly designated conceptions of an objective sense of authenticity or an existential search for a uniquely personal experience are renegotiated in these emerging socio-economic facts (Salet, Citation2021). Among the first firms in tourism to exploit the Internet as a platform to connect supply and demand were the online travel agencies and booking engines. Recently, B2C services (like BeMyGuest), which were previously covered only to a minimal extent, started to be offered, which opened up the areas of new business opportunities waiting for their use (UNWTO, Citation2017).

Considering the challenges, TOs will emphasise a sustainable and resilient recovery in the post-pandemic period, this research attempts to address these gaps and study how TOs see their future, particularly concerning platform tourism services.

3. Research methodology

The aim of the study is to analyse the relationship of TOs to tourism platform services in the context of a post-pandemic recovery.

A qualitative research methodology is used in this study, which is considered suitable when a new field of study is investigated (DeJonckheere & Vaughn, Citation2019; Jamshed, Citation2014). Specifically, the interview method was chosen as the most critical and widespread way of conducting tourism research, particularly under the post-positivist or interpretive and constructivist paradigms of research (Picken, Citation2018). Regarding this study’s exploratory and inductive nature, individual semi-structured interviews were undertaken where the researcher asked participants a series of predetermined but open-ended questions (DeJonckheere & Vaughn, Citation2019; Given, Citation2008).

3.1. Sampling strategy

We examine the problem with the example of the Central European country Slovakia. The reason for choosing this country is knowledge of the TOs market, relatively small size of the market (5.4 million residents) with innovation potential and a central location in the middle of Europe, which assumes that the holiday plans of the inhabitants, to which tour operators try to adapt, are more homogeneous and further oriented to the sea.

For selecting interview participants, purposeful sampling was applied, which is widely used (DeJonckheere & Vaughn, Citation2019) and a highly efficient sampling technique (Vasileiou et al., Citation2018), notably in gathering information from a specific population (Neuman & Robson, Citation2015) like interviewing tourism-related professionals. The sample size was determined by the limited availability of respondents, time constraints, as well as by project manageability. Based on the researchers’ previous experience and literature (Boddy, Citation2016), we estimated that the recruitment of 20 representatives of TOs responsible for product creation would be sufficiently large enough and varied to reveal the aim of the study.

The potential interview participants were selected from the list of tour operators maintained and published by The Slovak Trade Inspection Authority as the supervisory body of the Act no. 170/2018 Law on packages of travel services and linked travel arrangements. According to Pompurová (Citation2020), a year before the corona crisis, 232 active tour operators were in the Slovak market, while 97% were small organizations. The vast majority (88.4%) were primarily focused on outbound tourism, 8.2% in domestic and 3.4% in inbound tourism. The market was slightly dominated (55.6%) by general tour operators offering various mass products, while 44.4% of tour operators were specialised.

3.2. Study procedure

The interviews were based on a flexible interview protocol (Ritchie et al., Citation2005) to keep the interview focused on the desired line of action and examine respondents’ opinions and attitudes more systematically and comprehensively (Jamshed, Citation2014). The interview protocol questions were developed according to the UNWTO report (UNWTO, Citation2017) and comprised of the core question and several follow-up questions and comments (DeJonckheere & Vaughn, Citation2019; Jamshed, Citation2014). The instrument was pre-tested by four academics for improving validity in qualitative data collection procedures and the interpretation of findings (Hurst et al., Citation2015).

Firstly, we asked the interview participants how they see the future of TOs after the COVID-19 pandemic. We were curious what topics they would spontaneously mention and whether they would relate to sustainability, digital technologies, or even the platform economy. Second, we asked them directly about the relationship of the TOs to the platform tourism services. Finally, as UNWTO (Citation2017), five tourism segments were presented in the context of the platform economy. Subsequently, we specifically asked the TOs representatives if they planned to incorporate them into their product in the future:

platform information services (user-generated reviews, ratings, and content for tourism-related services),

platform accommodation services (short-term rentals of beds, rooms, apartments, homes, etc.),

platform transport services (short-distance ride-hailing, long-distance ridesharing, vehicle-sharing services),

platform food-related services (home cooking and communal dining in a private environment, cook courses) and

other platform tourism activities (guided tours and excursions, attractions, and similar activities).

The follow-up questions aimed to find out whether the interview participant knew the service, what it thought of it and whether it had ever used it. The supplement comments related explanations of what the service involves and gives examples of the concrete digital platforms provided by the service.

During December 2020, 157 subjects from the list of tour operators published by The Slovak Trade Inspection Authority have been sequentially contacted by email and telephone. Finally, 20 of them agreed to be interviewed, so the interview date was arranged. Due to anti-pandemic measures, particularly regarding the current curfew, the interviews were conducted by telephone or online from 4 January to 15 February 2021. Picken (Citation2018) mentioned that the advantage of using communication technologies during interviews is convenient for the researcher, who can alleviate the time and the budget and the possibility to address a geographically dispersed territory. The interviews lasted from 21 to 45 minutes and were conducted in the Slovak language.

Almost all (19) interview participants were the owners of small tour operator organizations, only one held a managerial position in a medium-size tour operator company. From the total number of 20 interview participants, 11 were representatives of general tour operators, and 9 participants represented specialised tour operators. Except for one tour operator offering package tours in Slovakia, they represent organizations focused on outbound tourism, which is typical for the local market. We state that the sample of interview participants offers a good picture of the TOs market of the surveyed country in terms of the size of organizations, product specialization and geographical targeting of the product. summarises the profile of organizations that participants represented.

Table 1. The profile of TO represented by interview participants

To capture the interview data authentically and effectively, the interviews were recorded and then transcribed into written text. As the declension of nouns and the verb tenses in the Slovak language complicate the search for codes in qualitative software, the text was translated into English before performing a content analysis. The data were coded, analysed, and categorised using Atlas.ti software. Categorisation facilitated the identify main issues and capturing the variety of stated issues. The transcript was carefully read through numerous times to ensure the detailed textual analysis necessary for describing the phenomenon under investigation.

3.3. Results and discussion

The results of this study are summarised and reinforced with direct quotes taken from the scripts.

3.4. The future of the TOs after the COVID-19 pandemic

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we looked at how TOs see their future. Most expressed the belief that travel would not disappear because it gave a dynamic sense of freedom, and people would continue to be eager to learn about other countries, e. g.: “I believe that tourism will return to prominence this year, because people want to have experience, they want to travel and discover, discover new things. They want to see life in other countries as well. Traveling gives freedom. I will do everything to ensure that travel never ends “(IP12). “Over time, and with the expansion of vaccination, business travel will gradually resume, as we see the need to travel even during a pandemic “(IP16). “The situation will definitely change, but we think that clients will be “hungry” for travelling. We are concentrating abroad, but, of course, as people living in Slovakia, we hope that tourism will also be restored “(IP20).

However, they warned that returning to the pre-pandemic period will be neither quick nor easy. While more optimistic organizations speak of several (2–3) years, others more realistic estimates mention from the medium to the long-term horizon of a gradual recovery of TOs market. They also explain that it is necessary to anticipate structural changes on both the demand and supply sides.

TOs agree that, in the beginning, the clients will be careful and postpone their purchase of the product until the last possible moment, to make sure that measures at the borders or destinations do not restrict their stay, or to make sure that their trip will be refunded or transferred under the most favourable of possible conditions. More than ever before, health security will play a key role in choosing the destination as well as the specific accommodation facility. According to the representatives of TOs, this can also be reflected in the preference of smaller accommodation facilities at the expense of the scope, complexity and higher standard of services provided. At the same time, TOs consider the fast tempo of vaccination against COVID-19 and a uniform and predictable system enabling foreigners to enter the country, for example, in the form of a Covid passport, to be an essential determinant for easing business. The obligation to pass the PCR test before or after returning from abroad or domestic quarantine after returning from abroad is no longer perceived by TOs as a significant obstacle to their business, as the clients are willing to complete the procedures and count on a specific time reserve for possible quarantine after returning from vacation.

TOs are aware that those who are willing and able to adapt to the changes will survive, e.g.: “Those who can adapt to change will survive. We hope to be among them “(IP9). They anticipate that a commitment contracting will certainly not be possible in the future to the same extent as in the past. They see the reason for the lower purchasing power of the population, the constantly growing share of individual travellers, and the effort to avoid risk by postponing the purchase of tourism services until the last minute. More than a third of the contacted TOs are pessimistic and fear whether they will be able to survive in the current situation. On the other hand, two-thirds of the companies have hope for gradual positive market developments. Instead of hibernation, they fully innovate their products (new destinations, new concept of offered products, greater emphasis on the winter season, product for individuals, etc.), and the way of communication with potential clients, so that the offer is more adapted to the new trends. Ultimately, they perceive a pandemic year as a challenging year and a year that has taught them a lot.

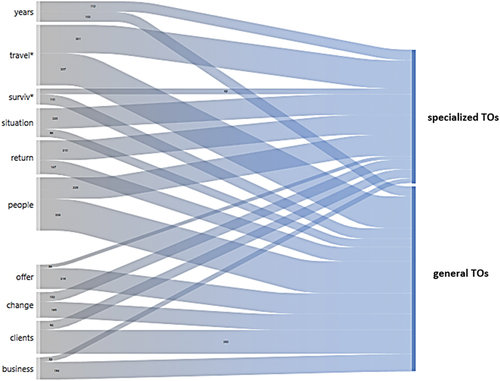

We were interested if there was a difference between general and specialised TOs. While less than a fifth of general TOs have a gloomier view of the future, more than half of specialised TOs are pessimistic. In their answers, the struggle for survival resonates and a questionable return to the “normal situation”, which can last for years. On the contrary, general TOs will focus more on the future offer of travel experiences for people, resp. potential clients ().

3.5. The relationship of the TOs to platform tourism services

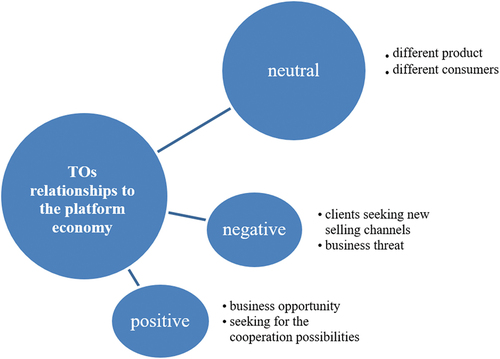

We were interested in the relationship of TOs to tourism services provided on the principle of a platform economy. Most respondents sought to defend the importance of the existence of TOs on the market and argued that their product is diametrically different from the individual services offered through digital platforms in terms of complexity, customer care and employee qualifications. They acknowledge that demand for TOs products will be lower in the upcoming years. Still, specific target segments (especially business clients, seniors, and middle-aged people) are not changing their habits. Therefore, they do not see the platform economy as a threat and do not consider it an opportunity (). They are convinced that for a certain share of the population, the use of TO services is more convenient and cheaper, or it is a confirmation of their social status; therefore, platform tourism services are not considered competition for TOs.

The second group of representatives of TOs are convinced that tourism will inevitably change, with information technology having a significant impact on the business. At the same time, some of them perceive this as a threat to their existence, for example: “Regardless of COVID, tourism was facing a radical change. Mainly by changing sales channels. The solvent generation of IT-skilled consumers grew up, and only older clients, accustomed to the smell of catalogues, qualified words of the seller, went to bricks-and-mortar operations. The sharing economy is a real threat to classic tour operators and not only to them but also to hotel chains, standard transportation providers, … ” (IP10).

Other TOs consider platform tourism services as opportunities for innovative business. They are sensitive to the necessity to adapt to the needs and requirements of clients and become much more flexible, for example: “I have thought about such things, I believe it could be an opportunity to gain or retain customers, but certainly to save costs” (IP8).

However, at the same time they state, that the current legislation limits the cooperation: “We have cooperated with some of them before. However, it is not that simple in terms of legislation and product liability in the sense of the law” (IP5). According to Slovak Act no. 170/2018 Coll. on packages of travel services and linked travel arrangements, which is a transposition of the EU Package Travel Directive 2015/2302, the TOs are responsible for the package of services as a whole. Yet, TOs are afraid to guarantee the quality of platform services, which may be inherently variable. Besides, general accounting and tax laws permit organisations to trade only with the entities authorised to do business, which many platform service providers do not.

For more detailed information, we also asked TOs to what extent they used specific platform services to create the product in the past and which services they would like to incorporate into their offer in the future.

3.5.1. TOs and platform information

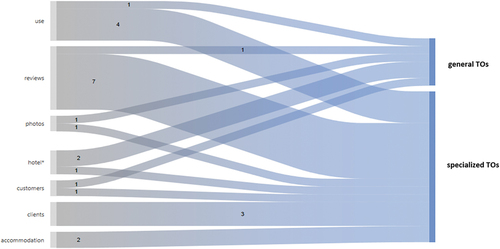

Representatives of the addressed subjects largely agreed that they proactively search for information available in specialised internet platforms (especially TripAdvisor, GoogleMaps or holidaycheck.de) and on social networks, primarily on Facebook, which is mainly used in Slovakia for private as well as business purposes. At the same time, general TOs assign greater importance to reviews compared to organizations with the specialised product ().

TOs use the reviews mainly to find and/or verify the quality of accommodation facilities (mostly hotels) that they plan to incorporate into their product. They appreciate the authenticity of the consumer opinions as well as published photos. Only two contacted TO representatives mentioned the need to select reviews, as real clients do not always write them. Also, because of this reason, they are not the only criterion for choosing a business partner. While most of the contacted TOs search for third-party platform information, only a minimum (two general TOs) engages in client reviews on digital platforms to eliminate shortcomings and continuously improve the services provided, e.g., “We need to receive feedback regarding our tours, but we do not place such a high demand on it. We do not send any questionnaires to our customers, and we leave it as it is. We focus mostly on social networks because now it is the top place where people communicate and write the most. When there is a negative review, we always want to improve it. We need to know our insufficiencies as well because we can eliminate them with the help of the reviews” (IP13).

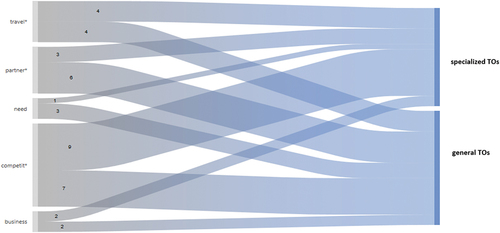

3.5.2. TOs and platform accommodation

Platform accommodation is perceived differently by the TOs. They are competitors more for TOs with a specialised product (9/9 specialized TOs) than for subjects offering a heterogeneous mass product (7/11 general TOs). General TOs compared to specialized TOs are more likely to consider them as potential partners (), even though they realize that digital platforms can act without them. According to the representatives of general TOs, platform accommodation is sought after mainly by language- and IT-skilled young people. Several of them have already given up the fight for this segment, so they do not need to fight digital platforms. They do not realise that Generation Y is gradually ageing and moving towards middle age. TOs point out that C2C platforms predominate in tourism. They are interested in cooperating with B2B digital platforms, which will enable them to create dynamic packages offered following current trends, like what online travel agencies do.

3.5.3. TOs and platform transport

We expected that in the case of the transport services, TOs would be more inclined to possible cooperation than accommodation services. However, our assumption was not fulfilled. The TOs have not yet cooperated with platform transport and, except for one entity, have strongly rejected possible cooperation in the future. Legislative obstacles were most often cited as reasons, especially issues of taxation and tax documents, but also the impossibility to guarantee quality and reliability of the service provider: “If we need the transport services for clients, we cooperate with reliable partners, there we can rely on 100% on the service quality, accuracy, technical condition of the vehicle, etc. I would never take an unknown driver for a client. I don’t know if they drive on time not to miss the plane or how they drive in terms of safety. When I travel alone, I also use this service, but if you are responsible for someone else selling a product that you want to be really top, you cannot afford to call someone you don’t even know. As for scooters or bicycles, we offer tours in places where it is possible to enjoy sightseeing on these means of transport. However, there is always an instructor or at least a guide; clients need to be provided with personal services “(IP17).

In their responses, TOs almost exclusively focused on short-distance ride-hailing (specifically on the C2C Bolt platform), which, in a certain sense, alternates with traditional taxi services. They marginally mentioned bike- and scooter sharing, completely omitting the sharing of other means of transport (cars, boats, possibly helicopters and aircraft), incorporating which into the product would make it possible to differentiate themselves from the competitors. In addition, in this segment, you can find the relatively largest share of B2B platforms suitable for partnership with TOs. The addressed subjects do not see the business opportunity even in long-distance ridesharing, which could be used creatively when offering tours for individuals travelling alone to less distant destinations.

3.5.4. TOs and platform food-related services

So far, none of the addressed TOs has incorporated platform food-related services into its product. One specialised TO planned to offer its clients a cooking course in Umbria, but the COVID-19 pandemic thwarted the implementation of this plan. Almost half of the representatives of TOs consider the platform food-related services to be very inspiring. In the future, they can imagine that they would offer them as part of team building tours or as an optional activity to diversify during traditional package tours. A quarter of subjects (especially specialised TOs) has not heard about these services yet, and more than a quarter, due to the nature of their product, do not plan to offer them in the future. They recommend their clients only proven, tried and tested services, which must be consistent in terms of quality, e.g., “I do not know this service. If I want to offer a service, I have to have it tested by myself (several times) to be satisfied with it” (IP17). Clearly, general TOs are more inclined to use food-related services platforms.

3.5.5. TOs and other platform tourism activities

TOs do not yet offer guide services and other platform tourism activities. The reason is mainly their ignorance. More than half of TOs representatives first replied that they had never heard of similar services. However, after explaining to them, several subjects showed interest in learning more about them, for example: “I admit that I do not know them and thank you for the information, I would like to learn something new (IP18). “I do not know them. I’ll look it up online later. I try to present to my customers every novelty that appears on the market and is interesting for travellers, and it’s up to them, how they decide … ” (IP12).

TOs, who already had some idea about these services, expressed a negative view of their future use. At the same time, general TOs were more open to new opportunities, which could theoretically imagine incorporating services provided on the ToursbyLocals or BeMyGuest platforms into sightseeing tours intended for schools and other customer groups.

3.5.6. Discussion

During the last decades, the development of ICT has interrogated the construction of the existing tourism distribution channel and the role of its participants, primarily the TOs, as traditional intermediators (Karcher, Citation1995; Orieška, Citation2011). Up to these days, TOs have made significant efforts in innovating their processes and products. Even though innovations are often costly and time-consuming, they must continue in favour of collaboration between all value chain members (Ibarnia et al., Citation2020).

The urgency of change has also increased in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has crippled tourism on an international scale (Brouder, Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2021; Wen et al., Citation2020). The world’s authorities’ calls for recovery through sustainable development are growing stronger. Although the scientific literature in this context deals with TOs only marginally, in general, sustainability in addressing the COVID-19 crisis is increasingly associated with smart technologies. Smart cities are based on the use of data and digital technology to improve services and improve performance in a maintainable way (Cooper et al., Citation2021; Lyons & Lăzăroiu, Citation2020; Scott et al., Citation2020), are an excellent example worth following.

We were interested in the relationship of the TOs to the tourism platform services, based on innovative use of ICT, in the context of a COVID-19 post-pandemic recovery. The research results show that the negative attitude of TOs towards the platform economy is far from dominant. On the contrary, several organizations perceive the platform economy as an opportunity for innovation, indispensable for survival. Therefore, the conclusions from the study, which focused exclusively on platform accommodation services mediated through the Airbnb platform (Pastor & Rivera García, Citation2020), can be extended.

As TOs know the undeniable importance of digital trust and reputation in the technology-driven sharing economy platforms (Hollowell et al., Citation2019; Pop et al., Citation2021; Popescu & Ciurlău, Citation2019), they attach particular importance to the platform information. However, instead of emphasizing their own online reputation management (Celata et al., Citation2020), TOs use platform information particularly to check the credibility and reliability of their potential suppliers. In this aspect, their activities are comparable to customer behavior, seeking to reduce potential risks (Hollowell et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, they do not appropriately deal with false reviews and the implications of this misinformation upon the organization, its marketing, and consumers (Di Domenico et al., Citation2021).

A previous study (Pastor & Rivera García, Citation2020) confirmed the willingness of TOs to include platform accommodation services in their product, despite the probable reduction in margins. However, a potential source of product innovation for TOs are mainly platform food-related services and other platform tourism activities enabling a truly authentic experience, which is sought after in tourism (Domínguez-Quintero et al., Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2020). Though, TOs do not consider the fact that the integration of platform tourism services into their product may allow them to line up resources to improve their services and save costs (Cooper et al., Citation2021; Hollowell et al., Citation2019). We, therefore, state that TOs do not yet fully appreciate the benefits of the platform economy, and even though they do not have a negative relationship with it, they do not realize that in addition to differentiating from the competition, platform tourism services can help them embark on the path of sustainability. Thus, platform tourism services can certainly be part of an alternative TOs product (Budeanu, Citation2005). However, the key is to choose reliable partners with an offer of stable quality. As there is no more profound examination of the potential cooperation between traditional tourism organizations and providers of platform tourism services in the available literature, we call for further research into this phenomenon in business. In this context, it is also necessary to deal with legislative constraints, particularly tax and accounting, which currently hamper cooperation between traditional businesses and platform service providers and thus the creation of affordable, authentic products.

4. Conclusion

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on TOs, which have largely lost the opportunity to market their products, is undeniable. Current TOs face many obstacles that deny their ability to save their business. In time, differentiation and low cost will open uncontested market space. The market frontiers and industry structure are not a given and therefore can be reconstructed, hybridised, converged to consider the needs of contemporary visitors, and keep in mind sustainability goals. Thus, there is every reason to adopt a blue oceans strategy and incorporate platform tourism services, especially if it is evident that the so-called sharing economy is there to stay and instead become ever more important? UNWTO (Citation2017, Citation2020) emphasizes communication, collaboration, cooperation, and coordination between all stakeholders to develop more sustainable and resilient tourism. So far, general TOs are more open to taking on this challenge.

Some limitations of the current research should be noted. First, the study refers to the particular territorial area, Slovakia, which is a small market characterised by a larger number of small-sized TOs, focused primarily on outbound tourism. Thus, it may, in a sense, act as an incubator. Moreover, interview participants represented almost exclusively small businesses, while larger TOs may be far different, as Van Wijk and Persoon (Citation2006) confirmed. Second, the research could be partially limited by the distance-defeating technologies using during the interview process, which reduce interaction. We do not consider the small number of interviewees (20) to be a significant limitation, as they represent almost 9% of the total number of active TOs in the Slovak market, roughly copying the market structure concerning product specialisation the thematic saturation achieved during the interviews. Finally, the research focuses on the intentions of the TOs representatives, not on real product creation, which can be affected soon by many variables, including changing requirements of consumers or economic exhaustion.

This study has several theoretical contributions. Primary, it introduces a theoretical framework connecting seemingly incoherent themes of TOs and the platform economy. Secondly, this research extends the existent limited literature focusing on the influence of TOs on sustainable development based on more rational consumption. As a final point, it fills a gap in the literature dedicated to the possibilities of COVID-19 recovery, outlining opportunities for reimagined TOs.

This study also provides significant practical implications. Firstly, ITC will significantly impact possible new solutions to making business that TOs should use to their advantage. Especially, the TOs should pay more attention to ongoing review management to retain clients for the next purchases. Future research suggested expanding this topic. Second, the TOs should consider the possibilities of incorporation of platform transport (especially unusual vehicle sharing), platform food-related services and other platform tourism activities into the original, more customisable authentic product able to replay to the growing demand of tourism based on experiences and contact with local communities. Third, given the lack of a legislative framework, it is perceived that this could be a major obstacle to cooperation, and thus this study calls for clearly defined legislation. Therefore, an international study analysing holes in legislation in the platform tourism services segments is strongly recommended.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kristína Pompurová

In their research activities, the authors of the paper deal with heterogeneous topics related to the tourism sector. Kristína Pompurová dedicates herself to the issues of tourism destination attractiveness, organized events, volunteer tourism, tour operator industry, and sharing economy. Ľubica Šebová is personally interested in issues related to the efficiency and performance of tourism organizations, financial controlling, destination management, accessible tourism, and sharing economy. Petr Scholz focuses on guest satisfaction, accommodation facilities, and eco-friendly facilities. He is also interested in contemporary issues of sports spectatorship. The authors’ paper is part of the project solution supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic VEGA, “Sharing economy as an opportunity for the sustainable and competitive development of tourist destinations in Slovakia.”

Notes

1. Concerning tourism services provided on the principle of the sharing economy, the UNWTO (Citation2017) explicitly uses the term “platform economy”, more specifically “platform tourism services”.

References

- Act no. 170/2018 Law on packages of travel services and linked travel arrangements.

- Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1595–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001

- Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research, 19(4), 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053

- Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

- Budeanu, A. (2005). Impacts and responsibilities for sustainable tourism: A tour operator’s perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2003.12.024

- Celata, F., Capineri, C., & Romano, A. (2020). A room with a (re)view. Short-term rentals, digital reputation and the uneven spatiality of platform-mediated tourism. Geoforum, 112, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.04.007

- Chen, G., Cheng, M., Edwards, D., & Xu, L. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic exposes the vulnerability of the sharing economy: A novel accounting framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29 , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1868484

- Cooper, H., Poliak, M., & Konecny, V. (2021). Computationally networked urbanism and data-driven planning technologies in smart and environmentally sustainable cities. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 13(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.22381/GHIR13120212

- De Las Heras, A., Relinque-Medina, F., Zamora-Polo, F., & Luque-Sendra, A. (2021). Analysis of the evolution of the sharing economy towards sustainability. Trends and transformations of the concept. Journal of Cleaner Production, 291, 125227 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125227

- DeJonckheere, M., & Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), 000057. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Dhiman, M. C., & Kumar, R. B. (2019). Building foundations for understanding the international travel agency and tour operation. In M. C. Dhiman & V. Chauchan (Eds.), Handbook of research on international travel agency and tour operation management (pp. 1–13). IGI Global.

- Di Domenico, G., Sit, J., Ishizaka, A., & Nunan, D. (2021). Fake news, social media and marketing: A systematic review. Journal of Business Research, 124, 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.037

- Domínguez-Quintero, A. M., González-Rodríguez, M. R., & Paddison, B. (2020). The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(2), 248˗260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1502261

- European Commission. (2016). Communication from the European Commission to the European Parliament. The Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A European Agenda for the collaborative economy. COM/2016/0356.

- European Parliament and Council. Directive (EU) 2015/2302 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on package travel and linked travel arrangements, amending Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004 and Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Council Directive 90/314/EEC.

- The European Tourism Manifesto alliance. (2021). Call for action: Accelerate social and economic recovery by investing in sustainable tourism development. https://www.ectaa.org/Uploads/documents/Manifesto-Paper-Investment-proposals-and-reforms-Travel-and-Tourism-final.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2021

- Given, L. M. (2008). The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE Publications.

- Hoang, L., Blank, G., & Quan-Haase, A. (2020). The winners and the losers of the platform economy: Who participates? Information, Communication & Society, 23(5), 681–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1720771

- Holland, J., & Leslie, D. (2018). Tour operators and operations. Development, management & responsibility. CABI.

- Hollowell, J. C., Rowland, Z., Kliestik, T., Kliestikova, J., & Dengov, V. V. (2019). Customer loyalty in the sharing economy platforms: How digital personal reputation and feedback systems facilitate interaction and trust between strangers. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 7(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.22381/JSME7120192

- Hurst, S., Arulogun, O. S., Owolabi, A. O., Akinyemi, R., Uvere, E., Warth, S., & Ovbiagele, B. (2015). Pretesting qualitative data collection procedures to facilitate methodological adherence and team building in Nigeria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691501400106

- Ibarnia, E., Garay, L., & Guevara, A. (2020). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the travel supply chain: A literature review. Sustainability, 12(23), 10125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310125

- Jamshed, S. (2014). Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy, 5(4), 87–88. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-0105.141942

- Jorge-Vázquez, J. 2019. La economía colaborativa en la era digital: Fundamentación teórica y alcance económico. In S. L. Náñez (Ed.), Economía Digital y Colaborativa: Cuestiones Económicas y Jurídicas (pp. 11–31). Università degli Studì Suor Orsola Benincasa. Eurytonpress. Retrieved April 7, 2021, from https://drive.google.com/file/d/14fAWUizIudKE11cKjJvaRGdnnjMu0wk-/view?usp=sharing

- Karcher, K. (1995). The emergence of electronic market systems in the European tour operator business. Electronic Markets, 5(1), 10–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10196789500000015

- Klarin, A., & Suseno, Y. (2021). A state-of-the-art review of the sharing economy: Scientometric mapping of the scholarship. Journal of Business Research, 126, 250–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.063

- Kvítková, Z., & Petru, Z. (2021). Vouchers as a result of Corona virus and the risks for tour operators and consumers. Mednarodno Inovativno Poslovanje, 13(1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.32015/JIBM/2021.13.1.65-71

- Lim, W. M. (2021a). History, lessons, and ways forward from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Quality and Innovation, 5(2), 101–108.

- Lim, W. M. (2021b). Toward an agency and reactance theory of crowding: Insights from COVID‐19 and the tourism industry. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(6), 1690–1694. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1948

- Lin, L.-P., Yu, C.-Y., & Chang, F.-C. (2018). Determinants of CSER practices for reducing greenhouse gas emissions: From the perspectives of administrative managers in tour operators. Tourism Management, 64, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.07.013

- Lyons, N., & Lăzăroiu, G. (2020). Addressing the COVID-19 crisis by farnessing internet of things sensors and machine learning algorithms in data-driven smart sustainable cities. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 12(2), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.22381/GHIR12220209

- McNicol, B., & Rettie, K. (2018). Tourism operators ‘perspectives of environmental supply of guided tours in national parks. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 21, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2017.11.004

- Montes, D. (2020). What will happen to tour & activities operators after COVID-19?. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.plugandplaytechcenter.com/resources/what-will-happen-tour-activities-operators-after-covid-19/

- Mostafanezhad, M. (2020). Covid-19 is an unnatural disaster: Hope in revelatory moments of crisis. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 639–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763446

- Neuman, W. L., & Robson, K. (2015). Basics of social research qualitative and quantitative approaches. Third Canadian edition. Pearson Education.

- Orieška, J. (2011). Služby v cestovnom ruchu I. časť. DALI-BB.

- Pastor, R., & Rivera García, J. (2020). Airbnb and tourism intermediation. Competition or coopetition? The perception of travel agents in Spain. Empresa Y Humanismo. 23,(2), 107–132. https://doi.org/10.15581/015.XXIII.2.107-132

- Peña-Vinces, J., Solakis, K., & Guillen, J. (2020). Environmental knowledge, the collaborative economy and responsible consumption in the context of second-hand perinatal and infant clothes in Spain. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 159, 104840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104840

- Picken, F. (2018). The interview in tourism research. In V. Hillman & K. Radel (Eds.), Qualitative methods in tourism research. Theory and practice (pp. 200–223). Channel View.

- Pompurová, K. (2020). Cestovné kancelárie na území Slovenska – Charakteristika podnikov, ich lokalizácie, produktu a výkonov. Geografické Informácie, 24(2), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.17846/GI.2020.24.2.457-472

- Pompurová, K., & Marčeková, K. (2017). Are the volunteer projects included in package holiday tour? Case study evidence from the Slovakia and Czech Republic. Journal of Tourism and Services, 91, 19˗26.

- Pop, R., Săplăcan, Z., Dabija, D. C., & Alt, A. M. (2021). The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Current Issues in Tourism, 24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1895729

- Popescu, G. H., & Ciurlău, F. C. (2019). Making decisions in collaborative consumption: Digital trust and reputation systems in the sharing economy. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 7(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.22381/JSME7120191

- Ritchie, B. W., Burns, P., & Palmer, C. A. (2005). Tourism research methods: Integrating theory with practice. CABI Publishing.

- Salet, X. (2021). The search for the truest of authenticities: Online travel stories and their depiction of the authentic in the platform economy. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103175

- Scott, R., Poliak, M., Vrbka, J., & Nica, E. (2020). COVID-19 response and recovery in smart sustainable city governance and management: Data-driven internet of things systems and machine learning-based analytics. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 12(2), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.22381/GHIR12220202

- Serrano, L., Sianes, A., & Ariza-Montes, A. (2020). Understanding the implementation of Airbnb in urban contexts: Towards a categorization of European cities. Land, 9(12), 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120522

- Sigala, M. (2008). A supply chain management approach for investigating the role of tour operators on sustainable tourism: The case of TUI. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15), 1589–1599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.04.021

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- UNWTO. (2017). New platform tourism services (or the so-called sharing economy) – Understand, rethink and adapt. World Tourism Organization. Madrid.

- UNWTO. (2020). One planet vision for a responsible recovery of the tourism sector. Retrieved April 16, 2021, from https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-12/en-brochure-one-planet-vision-responsible-recovery.pdf

- UNWTO (2021, April 15). Tourist arrivals down 87% in January 2021 as UNWTO calls for stronger coordination to restart tourism. https://www.unwto.org/news/tourist-arrivals-down-87-in-january-2021-as-unwto-calls-for-stronger-coordination-to-restart-tourism

- Van Wijk, J., & Persoon, W. (2006). A long-haul destination: Sustainability reporting among tour operators. European Management Journal, 24, 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2006.07.001

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

- Wen, J., Wang, W., Kozak, M., Liu, X., & Hou, H. (2020). Many brains are better than one: The importance of interdisciplinary studies on COVID-19 in and beyond tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 45, 310–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1761120

- Wong, S. D., Broader, J. C., & Shaheen, S. A. (2020). Can sharing economy platforms increase social equity for vulnerable populations in disaster response and relief? A case study of the 2017 and 2018 California wildfires. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 5, 100131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100131

- Yeh, S. S. (2021). Tourism recovery strategy against COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1805933

- Yu, J., Li, H., & Xiao, H. (2020). Are authentic tourists happier? Examining structural relationships amongst perceived cultural distance, existential authenticity, and wellbeing. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22, 144 ˗154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2324

- Yusoff, N. M., Zahari, M. S. M., Kutut, M. Z. M., & Sharif, M. S. M. (2013). Is Malaysian food important to local tour operators? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 105, 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.048

- Zahari, M. S. M., Hanafiah, M. H., Akbar, S. N. A., & Zain, N. A. M. (2020). Perception of tour operators on rural tourism products: To sell or not to sell? The Journal of Rural and Community Development, 15(2), 8–28. https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/download/1733/413/5148

- Zhu, H. (2020). Why a non-discrimination policy upset Airbnb hosts? Annals of Tourism Research, 122, 102984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102984

- Zhu, X., & Liu, K. (2020). A systematic review and future directions of the sharing economy: Business models, operational insights and environment-based utilities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 290, 125209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125209