?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The pandemic leap continues and only makes things worse. Sharp criticism continues to pour in about what measures it can put in place to reduce the social crisis. Although some have accused the restrictions of being relaxed (lockdown), it does not improve human nature, which instinctively requires communication with partners, family, and co-workers. This study has a target to uncover the relationship between stress and anxiety on social tourism interest. We invited the 321 respondents to be surveyed online. The characteristics of the response involved cross-age, namely generations Y and Z (17 to 40 years) from 15 provinces in Indonesia. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) applied to the AMOS program to interpret the data. Statistical tests found that stress and anxiety levels had no significant effect on social tourism interest. Other results prove an important difference if altruistic value increases social tourism interest significantly. From empirical moderation, altruistic value actually plays a significant role in the relationship between stress and anxiety levels in social tourism interest. The respondents have emotional resilience in the face of COVID-19. Finally, the novelty, contribution, and implications of the research is comprehensively disclosed. A follow-up agenda could investigate these findings in order to improve upon the limitations of the study.

1. Introduction

Since 2020, Indonesia has faced an exploding population density, where the composition of the population is 270.20 million people with a composition aged 75+ years reaching 1.87% (Helmi et al., Citation2021). Interestingly, 11.56% of pre-baby boomers are aged 56–74 years, where at 40–56 years are those classified as generation X (11.56%) and generation Y (24–39 years) slightly above generation X is 25.87%. The Z generation aged between 8–23 years is around 27.9%, while the Z generation post aged 0–7 years is 10.8%. If we look at this population structure, then generation Y and generation Z or those with a maximum age of 40 years are +50% (Dwidienawati & Gandasari, Citation2018).

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), it seems to provide multiple stresses in people’s lives (Ratnasari et al., Citation2021). Besides being afraid of contracting the virus, they are worrying about losing family members, colleagues, and the stress of being fired by a company that is experiencing a decline in acceptance (Roy et al., Citation2021). Various media reports also trigger constant reporting of the situation and numbers of people infected or dying by COVID-19, so that over time it triggers a sense of stress (Nicomedes & Avila, Citation2020). They are now excessively depressed during the pandemic (Yang et al., Citation2021).

describes the results of the online survey in May 2021. The level of anxiety and depression, which reflects demographic, geographic, social, and economic conditions, is correlated with changes in work status and changes in income during COVID-19.

Table 1. Mental health disorders due to the pandemic in Indonesia

also highlights about 55% of the informants showing depression with varying degrees of anxiety (from mild to severe). Another impact for women, they experience higher anxiety than men. The greater the educational background, the lower the level of anxiety. The 20–40 year age group actually experienced higher tension, where those classified as victims of unilateral dismissal and decline in welfare also experienced more severe levels of anxiety. Another urgent matter that is quite prominent is that 80% of the participation of 1522 informants in the world, identified by symptoms of stress as a negative response by COVID-19 (Saeed et al., Citation2021; Spinelli et al., Citation2020).

Substantially, stress is defined as the inability to cope with the pressure that is being faced that comes from external pressures, mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual pressures that are unstoppable and affect the individual’s physical condition (Salleh, Citation2008). In addition, anxiety is an individual response that begins with worry and discomfort by an unclear object (Grupe & Nitschke, Citation2013).

Scientists who focus on psychological science reflect that two dimensions such as anxiety and stress are needed in life (Rodríguez-Rey et al., Citation2020; Segerstrom & Miller, Citation2004; Steimer, Citation2002). At a low level, even moderate, people are moved to dive into an activity. For example, enthusiasm for anxiety in the future will encourage individuals to study hard or feel bored with a surge in life needs (Epel et al., Citation2018). The essence that describes economic activities more actively will allow high stimulation, where individuals have been dedicated to highlighting broad thinking power and maintaining social abilities (Wuryaningrat et al., Citation2021).

Psychologists also advise individuals who are psychologically shaken, such as anxiety disorders, to actualize a positive activity through doing good by helping others, prioritizing caring for nature, and blending with the environment so that stress can disappear (House & Stark, Citation2002).

One means to reduce individual stress levels that can be chosen is social tourism. In recreation, social tourism is not yet popular (Chen et al., Citation2016). However, for the case in Indonesia, several travel agencies offer this social tourism package. In addition to refreshing, tourists who travel socially can also do good according to their calling by caring for the natural environment, so that the output will reduce anxiety levels (Rahman et al., Citation2021; Zhuang et al., Citation2019).

In Berlin (Germany), there is a unique social tourism character, where tourists are invited to visit places that are usually used for sleeping, sitting, and gatherings of the homeless. In this way, they gain insight into how the homeless live in the context of cultivating the social spirit of the community (e.g. Brown, Citation2014; Füller & Michel, Citation2014; Garcia, Citation2016). The tourists have an emotional bond and avoid negative stigma.

Taking the above perspective, the reason for taking this topic is that there is a gap between studies on the research subject. Abbas et al. (Citation2021), Gössling and Schweiggart (Citation2022), Rokni (Citation2021), Pocinho et al. (Citation2022) and Kang et al. (Citation2021) describe that stress is a crucial motive for the reasons individuals and groups of people travel when a pandemic occurs. Dramatically, the fact that emerges is the prohibition and lockdown policies that create generational inequality because young people cannot control their emotions compared to those who are older in age. Unexpectedly, the maturity aspect plays a key role when individuals face the problems or tragedies of Covid-19 rather than looking for other solutions (e.g. Fegert et al., Citation2020; Coulombe et al., Citation2020; Maison et al., Citation20210. Tactical, one solution, alternative, and recovery to minimize the current mental burden is not only by traveling but also consulting with a psychiatrist, discussing with family and colleagues, even strengthening worship (religion) significantly (Corrigan et al., Citation2014; Jacob, Citation2015). Although, traveling is also considered appropriate to simply refresh or neutralize the mind from all routines (Kusumaningrum & Wachyuni, Citation2020).

This study aims to review and summarize several points. The first essence relates to the cycle of stress and anxiety at a reasonable level (mild and moderate) intending to go on a social trip. In addition, we also need to explore the effect of individual characteristics (altruistic value) in encouraging social tourism interest. Research commitment is useful for addressing social tourism actors and helping them understand this unique market. It should be noted that the attributes of social tourism are tips for solving individual rationalities such as anxiety and stress, so that awareness of marketing communication can be channeled according to the condition of the segment group. It organized the rest of the paper into six attributes. The first point provides an introduction. Literature review can be distributed by the second point. The third point is the proposed method. The fourth point is as findings. The fifth point describes the results (discussion). The sixth point emphasizes the conclusion, limitation, and suggestion.

2. Literature review

2.1. Stress level

Fink (Citation2016) defines stress as a disorder of the mind and body that is affected by the demands and changes of life. Shahsavarani et al. (Citation2015) believes that stress arises from unpleasant disturbances, pressures, and tensions that come from outside the individual. Segerstrom and O’ Connor (Citation2012) actually claim that psychological and physiological reactions have the potential to cause stress, where the perception imbalance phase demands a level of burden on the individual’s ability to fulfill it.

Realizing this, Tsigos et al. (Citation2020) asserts that stress is a non-specific reaction of humans to stimulate any pressure. Godoy et al. (Citation2018) also views that stress is an adaptive reaction that is individual, so that one person’s response is not necessarily the same as someone else’s. In addition, the body’s reaction to psychosocial stressors, such as the burden of life or mental stress, also shows early symptoms of stress (Schneiderman et al., Citation2005).

In this case, the individual’s stress level lies in the degradation of overcoming the pressures faced, including spiritual, emotional, physical, and mental, which, at some point, ignores physical conditions (Williams, Citation2018). There are several elements that characterize stress, such as personal difficulties, distractions at work, and major threats from the community (Epel et al., Citation2018). The existence of conflicts with partners, not having welfare, anxiety about the future, gaps with colleagues, workload, lack of rest hours, experiences of violence and illness, even low economic opportunities, strengthen stress levels to the peak (Lestari et al., Citation2021).

Rafique et al. (Citation2019) groups three symptoms of stress, namely mild stress, moderate stress, and severe stress. Mild stress is a stressor experienced by the regular type of person. Early symptoms are when individuals receive criticism from superiors, lack of rest time, and due to traffic jams. The reason is, a mild stressful situation lasts for a few hours or minutes. In anti-climax, indeed those who experience it can solve problems and increase enthusiasm, but it is accompanied by characteristics such as feeling restless, decreased memory (brain), digestive system disorders, sometimes feeling tired for no reason, decreased energy reserves, and sharp eyesight. Without ruling out its effects, mild stress is actually useful because it can trigger individuals to think harder to face life’s challenges.

Separately, moderate stress lasted longer than mild stress. Publication by Othman et al. (Citation2013) concluded that moderate stress is driven by long-term family absences, sick children, and frustration due to unresolved conflicts with coworkers. The striking elements of this type of stress are the body feels unsteady, sleep disturbances, muscles and feelings of tension, to stomach pain.

Severe stress is classified and represented with a stress condition that is much longer than moderate stress. Sometimes, this might be felt by the individual over a period of weeks and months. Uniquely, the effects arise from chronic diseases that are difficult to cure until fatal for long-term physical changes, separation from family because of death, terrible and long-lasting financial difficulties that do not improve significantly, and persistent marriage disputes. Behaviors that are plagued by severe stress are indicated by the inability to complete simple work, increased fatigue, decreased concentration, negative thinking, difficulty sleeping, impaired social relations, and difficulty doing activities (e.g. Godoy et al., Citation2018; Memar & Mokaribolhassan, Citation2021). The first hypothesis is formulated below:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Stress level has a significant effect on social traveling interest.

2.2. Anxiety

Anxiety was popularized by Bystritsky et al. (Citation2013) as a response to uncontrollable feelings. In practice, anxiety is a pressure to feel threatened by individuals from unknown, internal, and vague sources (Kroenke et al., Citation2016). Anxiety differs from fear, which is a follow-up to a known, external, and clearly felt threat (Adwas et al., Citation2019).

Kemp et al. (Citation2021) underlined that the emergence of anxiety stems from individual subjective-based emotions, where the individual can no longer stem his behavior. It is important to remember if anxiety is a part of everyday life (Ayandele et al., Citation2020). Naturally, all humans certainly have levels of anxiety that give valuable signals of something dangerous. It is natural that it is necessary to survive.

Stuart and Laraia (Citation1998) assume that anxiety is an emotional and subjective experience without a specific object, thus channeling the individual to get rid of logical things such as excessive sensations, something bad happens, and autonomic symptoms in the short term.

Observing this phenomenon, Locke et al. (Citation2015) and Roerig (Citation1999) describe four levels of anxiety (mild, moderate, severe, and panic). The first is mild anxiety. This group highlights the tension of events in daily activities. Therefore, the individual will be vigilant. Of course, it is natural that those who experience mild anxiety disorders will issue their ability to form creativity. The physiological response that triggers it is the occasional experience of stomach symptoms, lip twitching, facial wrinkles, spikes in pulse and blood pressure, or shortness of breath. Then, the cognitive aspect is manifested by effective problem concentration, receiving complex stimuli, and widening the perceptual field. On the other hand, the form of their emotions and behavior such as a raised voice, fine tremors in the hands, and among them can not even sit still.

The second is moderate anxiety. Here, those who are positively affected by moderate anxiety are alleged to have a poor level of understanding of the environment and only concentrate on things that are important, while ignoring other aspects that are considered less important. Regardless of the other dimensions, the physiological responses of those confirmed to have this disorder are anxiety and constipation, diarrhea, anorexia, dry mouth, increased blood pressure and pulse, and shortness of breath. Attracting attention, if the cognitive element is actually contrary to rationality, where there is a degradation of the level of concentration, it is difficult to accept external stimuli, and environmental conditions are narrowed.

In severe anxiety, enthusiasm for environmental conditions becomes narrow, individuals have negative energy, and ignore general things. They also find it difficult to think realistically, so they need directions to focus on other areas. The physiological response of severe anxiety comprises heightened tension, blurred vision, unbearable headache, profuse sweating, excessive blood pressure, and shortness of breath. In the cognitive element, it actualized this with brief insight in reducing life’s problems, while for behavioral responses, the individual is at a peak emotional point, which has fatal consequences for blocking, feeling comfortable, and verbalizing.

In the realm of panic, a small ability to understand anything plagued the individual, including severe disorders, so that the individual can no longer control himself and finds it difficult to carry out activities even though he is supported by direction. Physiological responses such as shortness of breath, feeling of suffocation, chest pain, pallor, hypotension, and poor motor coordination are noted. Meanwhile, the cognitive response for sufferers is low logical thinking and often experiences biased perceptions. As an illustration of the positive response, the individual’s emotional level is agitation, loss of self-control, distorted perception, frequent shouting to oneself, and tantrums for things that are not clear. The following are hypotheses that can be developed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Anxiety level has a significant effect on social traveling interest.

2.3. Altruistic value

Hu et al. (Citation2016) commented the term altruism on which describes the nature of altruism. Egilmez and Naylor-Tincknell (Citation2017) and Bykov (Citation2017) divide altruism into two, namely selfish helping behavior and altruistic helping behavior. In providing help, humans have altruistic and selfish motives. Both incentives represent to provide help. On the one hand, selfish helping behavior actually benefits the helper, and the individual takes advantage of the person being helped (Kusumawati & Indriani, Citation2019). From the behavior of helping altruists is only applied solely to get a positive impression from the person being helped.

In line with this, Pfattheicher et al. (Citation2022) define altruism as an action by an individual or group of people to help others expecting nothing in return. More specifically, Levit (Citation2014) explains that altruism is the opposite of egoism. They converted altruism to a motive to improve the welfare of others, expecting nothing in return. Individuals who are altruistic tend to care for and want to help, even though there are no benefits offered for themselves or nothing to get something back in the future. It’s just that, from the dimension of individual belief values, willingness and liking for outrageous things to help others are oriented sincerely, purely, and do not expect any reward (benefit) for him. Schmid (Citation2010) enriches the explanation of altruistic value at the level of helping others is voluntary or the willingness to sacrifice for the sake of others.

Szuster (Citation2016) promotes three elements of altruistic behavior, such as volunteerism, willingness to give, and empathy. Volunteering means what it gave solely for others with no expectation of getting something in return, while empathy is the ability to get the feelings that are being experienced by others, and the leniency of giving should meet the needs of others.

Some aspects of altruistic behavior are practiced as follows: compassionate, impatient, generous, demanding mercy, ready and sensitive to act to help others, willing to sacrifice, not selfish, and cooperate without showing off (e.g. Filkowski et al., Citation2016; Oakley, Citation2013). Referring to the systematics of the concept, it is reasonable and logical to offer the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Altruistic value has a significant effect on social traveling interest.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Altruistic value strengthens the effect of stress level on social traveling interest.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Altruistic value strengthens the influence of anxiety level on social traveling interest.

2.4. Social tourism interest

Everyone commonly done traveling to release fatigue, stress, or escape for a moment from daily routines to regain energy, so that they can work with a happier and more normal feeling (Rahmawati et al., Citation2021).

Recently, tourism in the modern scope is a travel activity carried out individually or in groups to visit certain destinations for recreational purposes, learn about the uniqueness of tourist areas, self-development, and gain insight incidentally or in a short time (Cavagnaro et al., Citation2018). On a broad scale, tourism is an activity that is fun which is characterized by spending money or doing activities that are consumptive in nature. Ketter (Citation2021) changes the meaning of tourism, which is a temporary traveling process, to go to another place outside the place of residence with the motive of gaining experience, refreshing health, recognizing other cultures, identifying social structures, and other interests.

Tourism with the theme of nature, culture or shopping, has been widely highlighted, even often done, but most of the types of social tourism are not known by many parties, especially Indonesia, and even in other countries. This tourism application may also have not been widely developed, so that publications relevant to social tourism have not been formally reviewed.

Individuals who travel to travel with a specific purpose require extra work, especially during this pandemic. When the business and social environment changes because of the effects of the COVID-19 virus, which makes economic pressures even more severe, the restrictions on socialization weaken the energy for activities. Therefore, the intensity of charity-based travel will make individuals achieve more benefits, such as positive self-confidence. Unfortunately, in Indonesia itself, there are few travel agencies that offer social tourism packages.

Is it social tourism? It combined social tourism all forms of tourist visits with social activities. In its capacity, this tour is not only a means of refreshing and motivating memorable experiences to stimulate inner satisfaction for tourists. Social tourism is created through traveling in mountainous areas with reforestation programs, visiting traditional villages of an inland tribe to share learning experiences or donating books to children of these inland tribes, or you can also act as a volunteer in a nursing home in a mountainous area with a beautiful view for a few days.

This is a new feature that is modified to drive the economy, also stimulates nature conservation, reduces illiteracy for the community, and grows tourists’ awareness of fellow human beings, so that many people can enjoy the positive effect. Most importantly, for tourists, it is not just a formality to have fun, but also to spread kindness. Social tourism will synergize with extraordinary inner satisfaction, provide new experiences that have never been encountered before, and provide happiness.

Cisneros-Martínez et al. (Citation2017) reported that the interest in social travel from potential tourists will grow as their awareness increases. As described by Jablonska et al. (Citation2016), that when they collect and successfully receive information about the benefits got from social tourism, it is likely that they will be interested in trying it.

In an instant, interest can arise when potential visitors know the benefits promoted by the marketer and there is no doubt about those benefits. Because there are adventuring activities in social tourism, it is not suitable for the elderly (Slivar et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the ideal segment is aimed at the productive young population aged 18–55 years who have a powerful physique (Hysa et al., Citation2021; Monaco, Citation2018). Specifically, in this study, the authors focused on generations Y and Z (e.g. Dimitriou & AbouElgheit, Citation2019; Haddouche & Salomone, Citation2018). Marketing communications that cover awareness and interest are required, referring to qualifications.

2.5. Consumer behavior on social tourism

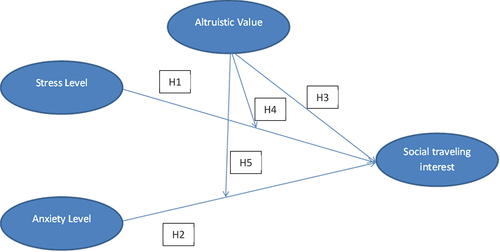

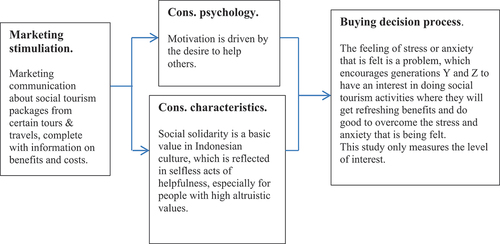

The approach of consumer behavior describes how a person proposes a purchase decision on goods or services, about what is behind the emergence of needs, consumer strategies for choosing products or services, to how to consume them, and compiling post-purchase evaluations (Harahap & Amanah, Citation2018; Petcharat & Leelasantitham, Citation2021). From this study, only simulating and examining stress, anxiety, and individual characteristics as altruistic values stimulates generations Y and Z who are interested in doing social tourism. displays a model of consumer behavior that is built based on the conceptual framework of the study.

Figure 1. Integration between consumer characteristics and market patterns.

Exposure of the marketing communication channel published by a tour and travel about social tourism open trips can move the motivation to take part. Altruistic values that are in line with motivation reinforce this. When feelings of stress and anxiety are increasingly formed and become a problem for the individual, then awareness slowly emerges towards positive things. Finally, stress and anxiety have the potential to increase interest in social travel to pursue goodness.

2.6. Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework is based on relevant phenomena because of the ongoing pandemic, so that many people suffer from stress and anxiety disorders. Actually, before the emergence of COVID-19 there were also many sufferers, but now the quantity is increasing. The pandemic, which also caused socio-economic surges to become increasingly unpredictable, actually had a systematic impact on entrepreneurs who lost their businesses and employees who were forced to lose their jobs. Not to mention the threat of viruses that can bring death and other factors to excess.

If left unchecked, stress and anxiety also produce depression, so that every individual who experiences these symptoms is getting higher and must immediately find a way out. One of them is trying to do good to others or focus on other people, so that the focus on putting yourself first will shift. The transformation that is applied through actualization to the surrounding environment will bring positive feelings. The media that can be channeled is social tourism, where individuals can be refreshed and immediately get out of misery.

In essence, individuals reform anxiety and stress through feelings of caution in acting and trying to survive to reduce these two conditions. If the intensity is quite heavy, then the individual will be fragile, difficult to communicate, and think rationally. They only concentrate on personal problems. Leaps through the professionalism of psychiatric care will cause competent outcomes.

Currently, the relationship between long-term consumer perceptions and behavioral intentions with respect to social tourism-related stress and anxiety is strongest, with the recent literature by Frajtova Michalikova et al. (Citation2022), Birtus and Lăzăroiu (Citation2021), and Watson and Popescu (Citation2021) claim that there are complex channels, motives, constructs, and portraits reflecting behavioral intentions and consumer perceptions that long-term influence stress and anxiety in social travel. From a different space, the relationship between consumers’ perceived value and cognitive attitudes regarding stress and anxiety in social tourism also shows a bright prospect (Andronie et al., Citation2021; Rydell & Kucera, Citation2021; Zvarikova et al., Citation2022).

To the author’s knowledge, there are no publications that analyze the relationship between stress and anxiety levels on individual interest in carrying out social tourism, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the author tries to produce a work on the factors that strengthen individual interest in social travel with limits on stress levels and anxiety levels moderated by altruistic values. We summarize the conceptual framework in .

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and data

This research uses quantitative techniques that are oriented towards marketing and social studies (e.g. Gupta et al., Citation2019; Snelson, Citation2016). We collected the data collection procedure from the survey. We have selected the data to be tested explanatory about the effect of the independent variables (stress level and anxiety level) and moderator variables (altruistic value) on the dependent variable (social traveling interest).

The research procedure focuses on generations Y and Z, arguing that the percentage of their population is the most dominant based on the Indonesian population census survey and also based on data by Survey Meter in 2020. That age group is prone to anxiety and explosive stress. Four specific criteria were to become a respondent, among others: 17–40 years old, Indonesian citizen, and willing to be interviewed, and understand the questions asked in the questionnaire. We applied data collection with an online survey (google form) during January 2022. The selection of samples was measured by purposive random sampling (e.g. Etikan et al., Citation2016; Palinkas et al., Citation2015; Sibona & Walczak, Citation2012).

3.2. Analysis method

Descriptive statistics and AMOS-based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) support the data analysis tool. The goal is to obtain empirical results based on a hypothetical design. Statistical descriptions use SPSS software in order to maintain the discussion. The logic of the procedure for analyzing data, interpreting, and expressing hypotheses is empirically covered by the SEM method.

3.3. Measurements

The material in the four variables has its own function and explanation. It formed the research questionnaire into two parts. The first part is about the demographics of the respondents and the second part concerns questions that reflect the variable components (see ).

Table 2. List of variables

3.4. Description of survey and verbal

Exclusively, implies that the informant’s profile refers to geographic location (domicile), age, educational background, profession, level of welfare as measured by expenditure, and hobbies. As a result, the questionnaires that have been distributed to fifteen areas in Indonesia are the areas with the highest enthusiasm for social tourism. Broadly speaking, most of the informants came from East Kalimantan, amounting to 83 informants (25.9%). Of the 321 samples, the dominant respondents aged between 17–24 years, which showed that they were Generation Z or those born between 1997 and 2012, were 180 informants (56.1%). Interestingly, 171 resource persons, or 53.3% of respondents, have completed their education at Diploma IV and Bachelor levels. Furthermore, 172 resource persons of whom were still students or reached 53.6% with an expenditure level of around <Rp 2,500,000 (187 resource persons) or 58.3%. The World Inequality Report (Citation2022) exposes that the national average minimum wage is Rp 2,700,000, while the average income of Indonesians per month is only Rp 5,700,000 million. Art is the most popular hobby field, with a range of 34.9% or 112 sources. also highlights the relevant composition of respondents representing each region in Indonesia, referring to their capacity to provide comprehensive, honest, and responsible information without any intervention.

Table 3. Characteristics of respondents

It measured categorization of assessments based on the score of respondents’ responses. It is determined by the number of measurement scales applied as many as five classifications. The formulation is:

Where: P = length of class for each interval, Xmax = maximum value, Xmin = minimum value, and b = number of classes.

Referring to the details of the class length of each interval, and detail the classification of assessment categories on the arithmetic mean and standard deviation of respondents’ perceptions.

Table 4. Formulation of assessments for descriptive statistics

Table 5. The mean value and standard deviation for each variable

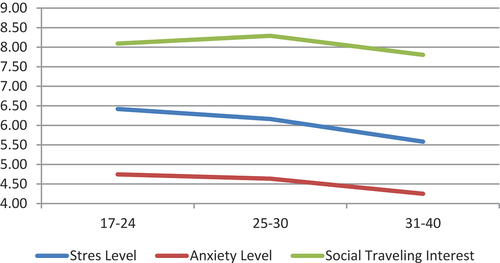

We proved that generations Y and Z in Indonesia do not feel a lot of stress or anxiety. This is seen from the stress level acquisition of 5.928 (moderate category), while the anxiety level is 4.219, which is relatively low. Thus, the pandemic has had little of an impact on generations Y and Z. They still have pretty good mental health.

4. Findings

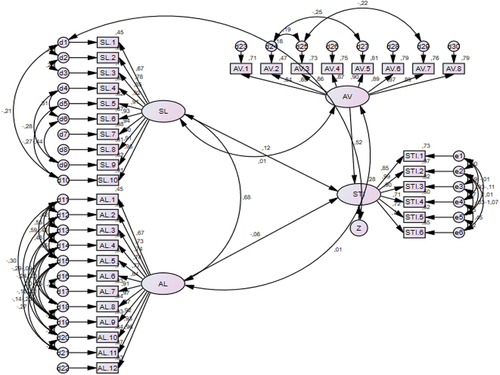

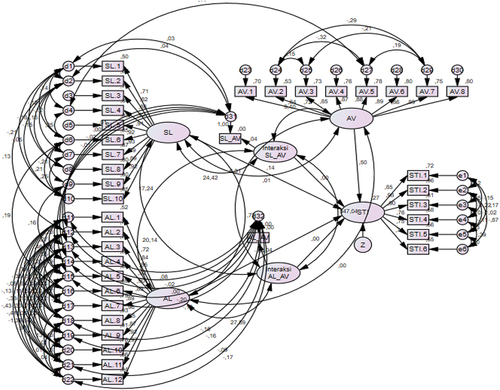

Data analysis using SEM must meet a set of goodness and fit criteria that predicts that we consider the model meeting the statistical requirements. The formulation of the model must be based on the relevant theory. The model in this study uses a one step approach to SEM according to the goodness and fit criteria, it seems that there is still a contrast. Therefore, it must apply modification indices according to the AMOS standard, which is to correlate between gradual errors starting from the acquisition of the largest modification indices. Tests for both causal and moderating relationships, reported in , , and , , , and . Specifically, in , the researcher combines 2 combined effects (direct and indirect effects) of all items.

Table 6. GoF results after modification indices

Table 7. Hypothesis testing between stress level, safety anxiety level, and altruistic value on social traveling interest

Table 8. GoF after modification indices for the moderation model

Table 9. Testing the moderating hypothesis

After the umpteenth time, we made modifications based on the AMOS SEM guideline; it was concluded that this model already met the goodness and fit criteria, although there is one criterion like AGFI, which is actually the opposite. The criteria can be ignored because reviewing other conditions has met the cut-off value. The reason for the poor AGFI criteria is that it does not align the model with the negative reactions or responses of the informants on several items in the questionnaire.

For hypothesis testing, the AMOS SEM method reported that only hypotheses 3, 4, and 5 were accepted, while hypotheses 1 and 2 were rejected. The test criteria are based on the amount of C.R > 1.96 and p < 0.05, so we can conclude that it has a significant effect. From another angle, in testing 5 research hypotheses, only hypothesis 3 fulfills these requirements.

5. Discussion

The test results show that of the 5 hypotheses built in this study, only 3 were accepted and the other 2 were rejected. The explanation is given below.

Hypothesis 1: Stress level has a significant effect on social tourism interest, rejected.

Hypothesis 2: Anxiety level has a significant effect on social tourism interest, rejected.

The rationale is that individuals who experience instability, such as anxiety and moderate stress, will need fun activities and positive channels. The rejection of the hypothesis, which states that stress levels have a significant effect on interest in social tourism, evidenced this, so the higher a person’s stress level is, the more they will have the intention to do good through social tourism. Wang and Zhao (Citation2020), Xu et al. (Citation2021), Liu et al. (Citation2021), Guo et al. (Citation2021), and Sengel et al. (2022) closely investigated the impact of stress, depression, anxiety, and psychology on Chinese society during the COVID-19 outbreak. His findings confirm the measures adopted to prevent these four factors were psychologically protective from the very beginning of the pandemic.

The pressure experienced by individuals has the potential to impact stress. There are two categories of stress, namely eustress and distress, which mean that stress can actually re-evoke motivation. However, this can also cause things that are not primed and have a negative impact, such as panic. In theory, people with severe stress will show signs of difficulty in activities, impaired social relations, difficulty sleeping, negative thinking, decreased concentration, increased fatigue, and unable to do simple work. Tactical pressure leads the sufferer to have an interest in social tourism.

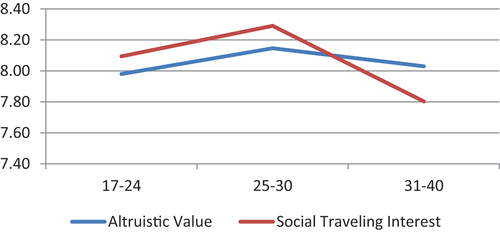

From the descriptive analysis, we can see that the average level of stress and anxiety experienced by generations Y and Z is only at a fairly low level, and allows them to do high social tourism. There is no congruence between these two variables, as shown in . From the graph, it is recognized that the more mature the individual, the less stress and anxiety, although the overall interest in doing social tourism is almost the same. The author also got information that, on average, generations Y and Z are experiencing moderate stress and low anxiety. However, at least they have the motivation to do good for the surrounding environment through social tourism.

Another unique thing revealed in this study explains several reasons generations Y and Z do not experience high stress and anxiety symptoms, even though the pandemic in Indonesia is not over yet. First, when this survey was conducted, the pandemic had been running for over 1.5 years, so they had adapted to various conditions that arose during the pandemic, such as restrictions on socialization, having to comply with health procedures, and other aspects. Second, they know certainly that being trapped in feelings of stress and anxiety cannot change the situation, because COVID-19 is a disaster that cannot be controlled. Making peace is the best way for their health. Third, Generations Y and Z in Indonesia are developing in religious teachings, making them continue to try their best and submit the results of their efforts to God’s decree. This will reduce the potential for feelings of stress and anxiety to be felt. Fourth, the generation who are familiar with the digital world, who stay connected with friends and acquaintances through social media, can also minimize stress and anxiety. Socialization does not have to be face to face. Fifth, the digital generation determines many opportunities. Finding various solutions to adversity is a powerful tip. Sixth, especially respondents, those who feel this impact are certainly not alone. Because many others have suffered the same fate, even worse. This also indicates that they do not need to corner the other party.

Individuals who feel high stress and anxiety actually have no interest in doing social tourism (e.g. Chen et al., Citation2016; Ohrnberger et al., Citation2017). With disturbed moral limitations it will not reduce stress and anxiety. They can no longer think logically and rationally, where fear and incompetence are increasing. Anxiety and stress at uncontrolled levels make individuals more focused on what they feel and concerned with worry that is not known for sure what the principal source is. This will make it difficult for them to adapt and see the difficulties of others, which leads to the low level of doing social tourism activities.

Hypothesis 3: Altruistic value has a significant effect on social traveling interest, accepted.

Altruistic value is a voluntary willingness to help others, or a willingness to sacrifice for the sake of others, which is driven by a sense of sincerity expecting nothing in return from others. Individuals with high altruistic values, they always moved their souls to do good to help others in need, according to their abilities.

Why do people with high altruistic values have an acute interest in social tourism? They are easily empathetic and sensitive to the suffering of others, because they are easy to call and pay attention to others, like to give help selflessly, and often put their personal interests lower than the interests of others. The author also finds that generations Y and Z in Indonesia have these two parts. They always carry out activities that contribute positively to other people and the environment during the pandemic.

Based on , it is known that the level of social traveling interest is linear with the level of altruistic value. In the 31–40 year age group, social traveling interest decreases significantly and the points are below the altruistic value. The phenomenon that can be explained is because in this age range, most people are married and have children under five, so it may be more difficult to do social tourism with family, where COVID-19 is very vulnerable to children under five.

Segments that are suitable for social tourism are characteristics with high altruistic value, have purchasing power, have enough time, and adequate physical strength. Moreover, for social tourism with the theme of environmental conservation or just doing a social trip to tribal areas inland.

Separately, Han et al. (Citation2020), Paraskevaidis and Andriotis (Citation2017), Shahzalal and Font (Citation2018), and Rodríguez et al. (Citation2021) have concluded that loving communication provides the best foundation under extreme stress such as scenarios for altruistic attachment that seriously impact traveling interest.

Hypothesis 4: Altruistic value strengthens the effect of stress level on social traveling interest, accepted.

Hypothesis 5: Altruistic value strengthens the effect of anxiety level on social traveling interest, accepted.

In hypotheses 1 and 2, it summarizes that the higher stress and anxiety it makes a person lose social skills, think logically, and rationally. They seem not interested in doing any activities, including the interest in doing social tourism. In hypothesis 3, altruistic value actually has a significant effect on social tourism interest. This is also in line with hypotheses 4 and 5, which try to find out whether altruistic values can strengthen the effect of stress levels and anxiety levels on social traveling interest. As a result, altruistic value cannot be a moderating variable for the relationship between the two.

The results also report that, on average, generations Y and Z have high altruistic values, especially when COVID-19 hit. At first they felt stress, a little anxiety, but prime interest in social tourism.

Several publications such as Israelashvili (Citation2021), Shallcross et al. (Citation2010), Ifdil et al. (Citation2020), Ágoston et al. (Citation2022), and Tyng et al. (Citation2017) explains that individuals who are bound by negative feelings felt stress and anxiety. The good news, after they consult the authorities and do a refresher, can change slowly. Then why is that? In fact, by paying attention to other people’s problems, the focus will shift from the problem at hand to other people, so that his heart will feel calm. In the end, the level of stress and anxiety will decrease and disappear. However, here to watch out for is the level of stress and anxiety is not a heavy level.

This study also claims that when individuals with high altruistic values and negative feelings activities that contribute positively to others will make them easy to distract from stress and anxiety. High interest must be compared to social tourism. They will get a double benefit. If the level of altruism is increasing, it will also increase interest in active social tourism.

Because of this, altruistic becomes an urgent attribute and orientation as a link between anxiety and stress to move traveling interest voluntarily (e.g. Berto, Citation2014; Haller et al., Citation2022; Luo & Lam, Citation2020; Pedrosa et al., Citation2020; Tepavčević et al., Citation2021; Yıldırım et al., Citation2022; Yulia et al., Citation2022).

6. Conclussion, limitation and suggestion

6.1. Conclusion

The aim of the study was to highlight the impact of stress and anxiety on social travel interest. Although there are no publications that highlight it, at least it can be a first step and a big change. Based on a series of tests, we found that generations Y and Z in Indonesia are in the structure of an educated society. They have adapted carefully when the epidemic hit, so the stress and anxiety they feel are also at a fairly mild level. The two generations also concluded that, on average, those who have high altruistic values tend to be easily attracted to activities that contribute positively to other people and the environment.

Indirectly, generations Y and Z have a great interest in social tourism, which is bridged by altruistic values. The high motivation to heal themselves from stress and anxiety indicates that the program is successful. In general, informants are a potential market for social tourism, but because the structure that is more practical to work on is the age of 17–30 years, we classified this for those who are still young. However, the attraction ratio is very high when compared to other age levels. Individuals who are experiencing high pressure, such as mild and moderate anxiety and stress, are still interested in social travel. The emergence of awareness causes this phenomenon to find solutions and not bother others for the negative feelings they feel.

6.2 Limitation and suggestion

This study also has some limitations that are oriented to be discussed in the future. Respondents who were invited were those belonging to generations Y and Z aged 17–40 years, where the largest group of students aged 17–24 years was 56%. Because the distribution of the questionnaires is not proportional, we hope it can expand the age range of the informants to 55 years of age.

In general, the research direction sees that there is potential for papers that impact important decisions by Gen Y and Z to create prime conditions and restore psychological stability when the Covid-19 pandemic spreads in Indonesia. At the same time, several critical concerns offer academic and theoretical contributions for further consideration.

Further recommendations also focus on survey techniques. The online-based data collection method during the pandemic was uneven and did not get an enthusiastic response from the economy class segment. For this reason, it is necessary to add participants to all segments through offline interviews. Regarding the moderator variable, individual economic conditions can sharpen it because this is important to investigate the status of those experiencing stress or anxiety, which also involves affluent economic groups during the pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbas, J., Mubeen, R., Iorember, P. T., Raza, S., & Mamirkulova, G. (2021). Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: Transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 21, 100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100033

- Adwas, A. A., Jbireal, J. M., & Azab, A. E. (2019). Anxiety: Insights into signs, symptoms, etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. East African Scholars Journal of Medical Sciences, 2(10), 580–24. https://doi.org/10.36349/EASMS.2019.v02i10.006

- Ágoston, C., Csaba, B., Nagy, B., Kőváry, Z., Dúll, A., Rácz, J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2022). Identifying types of eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, eco-grief, and eco-coping in a climate-sensitive population: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042461

- Andronie, M., Lăzăroiu, G., Ștefănescu, R., Ionescu, L., & Cocoșatu, M. (2021). Neuromanagement decision-making and cognitive algorithmic processes in the technological adoption of mobile commerce apps. Oeconomia Copernicana, 12(4), 863–888. https://doi.org/10.24136/oc.2021.034

- Ayandele, O., Popoola, O. A., & Oladiji, T. O. (2020). Addictive use of smartphone, depression and anxiety among female undergraduates in Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Health Research, 34(5), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHR-10-2019-0225

- Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral Sciences, 4(4), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4040394

- Birtus, M., & Lăzăroiu, G. (2021). The neurobehavioral economics of the COVID-19 pandemic: Consumer cognition, perception, sentiment, choice, and decision-making. Analysis and Metaphysics, 20, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.22381/am2020216

- Brown, L. (2014). Memorials to the victims of Nazism: The impact on tourists in Berlin. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 13(3), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2014.946423

- Bykov, A. (2017). Altruism: New perspectives of research on a classical theme in sociology of morality. Current Sociology, 65(6), 797–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116657861

- Bystritsky, A., Khalsa, S. S., Cameron, M. E., & Schiffman, J. (2013). Current diagnosis and treatment of anxiety disorders. P & T: A Peer-Reviewed Journal For Formulary Management, 38(1), 30–57. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3628173/

- Cavagnaro, E., Staffieri, S., & Postma, A. (2018). Understanding millennials’ tourism experience: Values and meaning to travel as a key for identifying target clusters for youth (sustainable) tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0058

- Chen, -C.-C., Petrick, J. F., & Shahvali, M. (2016). Tourism experiences as a stress reliever: Examining the effects of tourism recovery experiences on life satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 55(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514546223

- Cisneros-Martínez, J. D., Mccabe, S., & Fernández-Morales, A. (2017). The contribution of social tourism to sustainable tourism: A case study of seasonally adjusted programmes in Spain. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1319844

- Conte, B., Hahnel, U. J. J., & Brosch, T. (2021). The dynamics of humanistic and biospheric altruism in conflicting choice environments. Personality and Individual Differences, 173, 110599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110599

- Corrigan, P. W., Druss, B. G., & Perlick, D. A. (2014). The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(2), 37–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614531398

- Coulombe, S., Pacheco, T., Cox, E., Khalil, C., Doucerain, M. M., Auger, E., & Meunier, S. (2020). Risk and resilience factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A snapshot of the experiences of Canadian workers early on in the crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 580702. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580702

- Crosswell, A. D., & Lockwood, K. G. (2020). Best practices for stress measurement: How to measure psychological stress in health research. Health Psychology Open, 7(2), 2055102920933072. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102920933072

- de Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2008). Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environment and Behavior, 40(3), 330–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506297831

- Dimitriou, C. K., & AbouElgheit, E. (2019). Understanding generation Z’s travel social decision-making. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 25(2), 311–334. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.25.2.4

- Dwidienawati, D., & Gandasari, D. (2018). Understanding Indonesia’s generation Z. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(3.25), 245–252. http://dx.doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i3.25.17556

- Egilmez, E., & Naylor-Tincknell, J. (2017). Altruism and popularity. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 3(2), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijem.3.2.65

- Epel, E. S., Crosswell, A. D., Mayer, S. E., Prather, A. A., Slavich, G. M., Puterman, E., & Mendes, W. B. (2018). More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 49, 146–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.03.001

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

- Filkowski, M. M., Cochran, R. N., & Haas, B. W. (2016). Altruistic behavior: Mapping responses in the brain. Neuroscience and Neuroeconomics, 5, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.2147/NAN.S87718

- Fink, G. (2016). Chapter 1 - stress, definitions, mechanisms, and effects outlined: Lessons from anxiety. Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior (Handbook of Stress Series, 1, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800951-2.00001-7

- Flint, D. (2003). What is the relationship between indicators of stress and academic performance in third year university students: A follow up study. Coursework Master Thesis, Victoria University.

- Frajtova Michalikova, K., Blazek, R., & Rydell, L. (2022). Delivery apps use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consumer satisfaction judgments, behavioral intentions, and purchase decisions. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 17(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.22381/emfm17120225

- Füller, H., & Michel, B. (2014). ‘Stop being a tourist!’ new dynamicsof urban tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1304–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12124

- Garcia, L.-M. (2016). Techno-tourism and post-industrial neo-romanticism in Berlin’s electronic dance music scenes. Tourist Studies, 16(3), 276–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797615618037

- Ghazali, E. M., Nguyen, B., Mutum, D. S., & Yap, S.-F. (2019). Pro-environmental behaviours and value-belief-norm theory: Assessing unobserved heterogeneity of two ethnic groups. Sustainability, 11(12), 3237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123237

- Godoy, L. D., Rossignoli, M. T., Delfino-Pereira, P., Garcia-Cairasco, N., & de Lima Umeoka, E. H. (2018). A comprehensive overview on stress neurobiology: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 127. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00127

- Gössling, S., & Schweiggart, N. (2022). Two years of COVID-19 and tourism: What we learned, and what we should have learned. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(4), 915–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2029872

- Grupe, D. W., & Nitschke, J. B. (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3524

- Guo, K., Zhang, X., Bai, S., Minhat, H. S., Nazan, A., Feng, J., Li, X., Luo, G., Zhang, X., Feng, J., Li, Y., Si, M., Qiao, Y., Ouyang, J., Saliluddin, S., & West, J. C. (2021). Assessing social support impact on depression, anxiety, and stress among undergraduate students in Shaanxi province during the COVID-19 pandemic of China. PloS One, 16(7), e0253891. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253891

- Gupta, V. K., Atav, G., & Dutta, D. K. (2019). Market orientation research: A qualitative synthesis and future research agenda. Review of Managerial Science, 13(4), 649–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0262-z

- Haddouche, H., & Salomone, C. (2018). Generation Z and the tourist experience: Tourist stories and use of social networks. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0059

- Haller, E., Lubenko, J., Presti, G., Squatrito, V., Constantinou, M., Nicolaou, C., Papacostas, S., Aydın, G., Chong, Y. Y., Chien, W. T., Cheng, H. Y., Ruiz, F. J., García-Martín, M. B., Obando-Posada, D. P., Segura-Vargas, M. A., Vasiliou, V. S., McHugh, L., Höfer, S., Baban, A., … Gloster, A. T. (2022). To help or not to help? Prosocial behavior, its association with well-being, and predictors of prosocial behavior during the coronavirus disease pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 775032. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.775032

- Han, H., Lee, S., & Hyun, S. S. (2020). Tourism and altruistic intention: Volunteer tourism development and self-interested value. Sustainability, 12(5), 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052152

- Harahap, D. A., & Amanah, D. (2018). Online purchasing decisions of college students in Indonesia. International Journal of Latest Engineering Research and Applications, 3(10), 5–15. http://www.ijlera.com/papers/v3-i10/2.201810138.pdf

- Helmi, A., Sarasi, V., Kaltum, U., & Suherman, Y. (2021). Discovering the values of generation X and millennial consumers in Indonesia. Innovative Marketing, 17(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.21511/im.17(2).2021.01

- House, A., & Stark, D. (2002). Anxiety in medical patients. British Medical Journal, 325(7357), 207–209. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7357.207

- Hu, T. Y., Li, J., Jia, H., & Xie, X. (2016). Helping others, warming yourself: Altruistic behaviors increase warmth feelings of the ambient environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01349

- Hysa, B., Karasek, A., & Zdonek, I. (2021). Social media usage by different generations as a tool for sustainable tourism marketing in society 5.0 idea. Sustainability, 13(3), 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031018

- Ifdil, I., Yuca, V., & Yendi, F. M. (2020). Stress and anxiety among late adulthood in Indonesia during COVID-19 outbreak. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan Indonesia, 6(2), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.29210/02020612

- Iqbal, T., Elahi, A., Redon, P., Vazquez, P., Wijns, W., & Shahzad, A. (2021). A review of biophysiological and biochemical indicators of stress for connected and preventive healthcare. Diagnostics, 11(3), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11030556

- Israelashvili, J. (2021). More positive emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with better resilience, especially for those experiencing more negative emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648112. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648112

- Jablonska, J., Jaremko, M., & M, T. G. (2016). Social tourism, its clients and perspectives. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 7(3), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n3s1p42

- Jacob, K. S. (2015). Recovery model of mental illness: A complementary approach to psychiatric care. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(2), 117–119. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.155605

- Kang, S.-E., Park, C., Lee, C.-K., & Lee, S. (2021). The stress-induced impact of COVID-19 on tourism and hospitality workers. Sustainability, 13(3), 1327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031327

- Karakaya, Ç., Badur, B., & Aytekin, C. (2011). Analyzing the effectiveness of marketing strategies in the presence of word of mouth: Agent-based modeling approach. Journal of Marketing Research and Case Studies, 2011, 421059. https://doi.org/10.5171/2011.421059

- Kemp, E., Bui, M., & Porter, I. I. I. M. (2021). Preparing for a crisis: Examining the influence of fear and anxiety on consumption and compliance. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 38(3), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-05-2020-3841

- Ketter, E. (2021). Millennial travel: Tourism micro-trends of European generation Y. Journal of Tourism Futures, 17(2), 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-10-2019-0106

- Khoshaim, H. B., Al-Sukayt, A., Chinna, K., Nurunnabi, M., Sundarasen, S., Kamaludin, K., Baloch, G. M., & Hossain, S. (2020). Anxiety level of university students during COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 579750. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579750

- Kroenke, K., Wu, J., Yu, Z., Bair, M. J., Kean, J., Stump, T., & Monahan, P. O. (2016). Patient health questionnaire anxiety and depression scale: Initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(6), 716–727. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000322

- Kusumaningrum, D. A., & Wachyuni, S. S. (2020). The shifting trends in travelling after the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Reviews, 7(2), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.18510/ijthr.2020.724

- Kusumawati, W., & Indriani, Y. D. (2019). Altruism as perspective of medical students. Jurnal Medicoeticolegal Dan Manajemen Rumah Sakit, 8(3), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.18196/jmmr.83110

- Kuswoyo, Tentama, F., & Muhopilah, P. (2020). Altruism scale: A psychometric study for junior high school student. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 51(2), 208–219. https://gssrr.org/index.php/JournalOfBasicAndApplied/article/view/10818

- Lestari, D., Tricahyadinata, I., Rahmawati, R., Darma, D. C., Maria, S., & Heksarini, A. (2021). The concept of work-life balance and practical application for customer services of bank. Jurnal Minds: Manajemen Ide Dan Inspirasi, 8(1), 155–174. https://doi.org/10.24252/minds.v8i1.21121

- Levit, L. Z. (2014). Egoism and altruism: The “antagonists” or the “brothers”? Journal of Studies in Social Sciences, 7(2), 164–188. https://infinitypress.info/index.php/jsss/article/view/713

- Liu, X., Cao, H., Zhu, H., Zhang, H., Niu, K., Tang, N., Cui, Z., Pan, L., Yao, C., Gao, Q., Wang, Z., Sun, J., He, H., Guo, M., Guo, C., Liu, K., Peng, H., Peng, W., Sun, Y., and Zhang, L. (2021). Association of chronic diseases with depression, anxiety and stress in Chinese general population: The CHCN-BTH cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282(4), 1278–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.040

- Locke, A. B., Faafp, M. D., Kirst, N., & Shultz, C. G. (2015). Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults. American Family Physician, 91(9), 617–624. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2015/0501/p617.html

- Luo, J. M., & Lam, C. F. (2020). Travel anxiety, risk attitude and travel intentions towards “travel bubble” destinations in Hong Kong: Effect of the fear of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217859

- Maison, D., Jaworska, D., Adamczyk, D., Affeltowicz, D., & Atiqul Haq, S. M. (2021). The challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and the way people deal with them. a qualitative longitudinal study. PloS One, 16(10), e0258133. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258133

- Memar, M., & Mokaribolhassan, A. (2021). Stress level classification using statistical analysis of skin conductance signal while driving. SN Applied Sciences, 3(64), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-04134-7

- Monaco, S. (2018). Tourism and the new generations: Emerging trends and social implications in Italy. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0053

- Nicomedes, C., & Avila, R. (2020). An analysis on the panic during COVID-19 pandemic through an online form. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 14–22. https://doi/org/10 .1016/j/jad/2020/06.046

- Oakley, B. A. (2013). Concepts and implications of altruism bias and pathological altruism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(2), 10408–10415. https://doi/org/10 .1073/pnas/13025.47110

- Ohrnberger, J., Fichera, E., & Sutton, M. (2017). The relationship between physical and mental health: A mediation analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 195, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.008

- Othman, C. N., Farooqui, M., Yusoff, M. S. B., & Adawiyah, R. (2013). Nature of stress among health science students in a Malaysian University. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 105(3), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.026

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Paraskevaidis, P., & Andriotis, K. (2017). Altruism in tourism: Social exchange theory vs altruistic surplus phenomenon in host volunteering. Annals of Tourism Research, 62, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.11.002

- Pedrosa, A. L., Bitencourt, L., Fróes, A., Cazumbá, M., Campos, R., de Brito, S., Simões, E., & Silva, A. C. (2020). Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 566212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.021

- Petcharat, T., & Leelasantitham, A. (2021). A retentive consumer behavior assessment model of the online purchase decision-making process. Heliyon, 7(10), e08169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08169

- Pfattheicher, S., Nielsen, Y. A., & Thielmann, I. (2022). Prosocial behavior and altruism: A review of concepts and definitions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.021

- Pocinho, M., Garcês, S., & de Jesus, S. N. (2022). Wellbeing and resilience in tourism: A systematic literature review during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 748947. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748947

- Rafique, N., Al-Asoom, L. I., Latif, R., Al Sunni, A., & Wasi, S. (2019). Comparing levels of psychological stress and its inducing factors among medical students. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 14(6), 488–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2019.11.002

- Rahayu, G., Kurniati, D., & Suharyani, A. (2020). The influence of psychological factors on the buying decision process of tropicana slim sweetener products. SOCA: Jurnal Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian, 14(2), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.24843/SOCA.2020.v14.i02.p06

- Rahman, M. K., Gazi, M., Bhuiyan, M. A., Rahaman, M. A., & Xue, B. (2021). Effect of covid-19 pandemic on tourist travel risk and management perceptions. PloS One, 16(9), e0256486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256486

- Rahmawati, R., Achmad, G. N., & Adhimursandi, D. (2021). Do Indonesians dare to travel during this pandemic? Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 38(4), 1256–1264. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.38433-767

- Rahmawati, R., Oktora, K., Ratnasari, S. L., Ramadania, R., & Darma, C. D. (2021). Is it true that Lombok deserves to be a halal tourist destination in the world? A perception of domestic tourists. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 34(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.34113-624

- Ratnasari, S. L., Rahmawati, R., Ramadania, R., Sutjahjo, G., & Darma, D. C. (2021). Ethical work climate in motivation and moral awareness perspective: The dilemma by the covid-19 crisis?*. Public Policy and Administration, 20(4), 398–409. https://doi.org/10.13165/VPA-21-20-4-04

- Rodríguez, M., Pérez, L. M., & Alonso, M. (2021). The impact of egoistic and social-altruistic values on consumers’ intention to stay at safe hotels in the COVID-19 era: A study in Spain. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.2008881

- Rodríguez-Rey, R., Garrido-Hernansaiz, H., & Collado, S. (2020). Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1540. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540

- Roerig, J. L. (1999). Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, 39(6), 811–879. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10609447/

- Rokni, L. (2021). The psychological consequences of COVID-19 pandemic in tourism sector: A systematic review. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 50(9), 1743–1756. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i9.7045

- Roy, J., Hasid, Z., Lestari, D., Darma, D. C., & Kurniawan, A., . E. (2021). Covid-19 maneuver on socio-economic: Exploitation using correlation. Jurnal Pendidikan Ekonomi Dan Bisnis, 9(2), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.21009/JPEB.009.2.6

- Rydell, L., & Kucera, J. (2021). Cognitive attitudes, behavioral choices, and purchasing habits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 9(4), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.22381/jsme9420213

- Saeed, B. A., Shabila, N. P., Aziz, A. J., & Lahiri, A. (2021). Stress and anxiety among physicians during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Iraqi Kurdistan region: An online survey. PloS One, 16(6), e0253903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253903

- Salleh, M. R. (2008). Life event, stress and illness. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 15(4), 9–18. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22589633/

- Schmid, H. (2010). Philosophical egoism: Its nature and limitations. Economics and Philosophy, 26(2), 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266267110000209

- Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G., & Siegel, S. D. (2005). Stress and health: Psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141

- Segerstrom, S. C., & Miller, G. E. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin, 130(4), 601–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601

- Segerstrom, S. C., & O’Connor, D. B. (2012). Stress, health and illness: Four challenges for the future. Psychology & Health, 27(2), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2012.659516

- Şengel, Ü., Genç, G., Işkın, M., Çevrimkaya, M., Zengin, B., & Sarıışık, M. (2022). The impact of anxiety levels on destination visit intention in the context of COVID-19: The mediating role of travel intention. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-10-2021-0295

- Shahsavarani, A., Azad Marz Abadi, E., & Hakimi Kalkhoran, M. (2015). Stress: Facts and theories through literature review. International Journal of Medical Reviews, 2(2), 230–241. http://www.ijmedrev.com/article_68654.html

- Shahzalal, M., & Font, X. (2018). Influencing altruistic tourist behaviour: Persuasive communication to affect attitudes and self-efficacy beliefs. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(3), 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2184

- Shallcross, A. J., Troy, A. S., Boland, M., & Mauss, I. B. (2010). Let it be: Accepting negative emotional experiences predicts decreased negative affect and depressive symptoms. Behaviour Research And Therapy, 48(9), 921–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.025

- Sibona, C., & Walczak, S. (2012). Purposive sampling on twitter: A case study. The 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 04-07 January 2012, IEEE Xplore, Maui, HI, USA, pp. 3510–3519. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2012.493.

- Slivar, I., Aleric, D., & Dolenec, S. (2019). Leisure travel behavior of generation Y & Z at the destination and post-purchase. E-Journal of Tourism, 6(2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.24922/eot.v6i2.53470

- Snelson, C. L. (2016). Qualitative and mixed methods social media research: A review of the literature. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915624574

- Spinelli, M., Lionetti, F., Pastore, M., & Fasolo, M. (2020). Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1713. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713

- Steimer, T. (2002). The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 4(3), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2002.4.3/tsteimer

- Stuart, G. W., & Laraia, M. T. (1998). Stuart & Sundeen’s principles and practice of psychiatric nursing (6th Ed. St ed.). Mosby Year Book.

- Szuster, A. (2016). Crucial dimensions of human altruism. affective vs. conceptual factors leading to helping or reinforcing others. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 519. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00519

- Tepavčević, J., Blešić, I., Petrović, M. D., Vukosav, S., Bradić, M., Garača, V., Gajić, T., & Lukić, D. (2021). Personality traits that affect travel intentions during pandemic COVID-19: The case study of Serbia. Sustainability, 13(22), 12845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212845

- Tsigos, C., Kyrou, I., Kassi, E., Chrousos, G. P. et. al. (2020). Stress: Endocrine physiology and pathophysiology. In K. R. Feingold (Ed.), Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.

- Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M., & Malik, A. S. (2017). The influences of emotion on learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454

- van Oort, F. V., Greaves-Lord, K., Ormel, J., Verhulst, F. C., & Huizink, A. C. (2011). Risk indicators of anxiety throughout adolescence: The TRAILS study. Depression and Anxiety, 28(6), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20818

- Wang, C., & Zhao, H. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety in Chinese university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01168

- Watson, R., & Popescu, G. H. (2021). Will the COVID-19 pandemic lead to long-term consumer perceptions, behavioral intentions, and acquisition decisions? Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 16(4), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.22381/emfm16420215

- Williams, D. R. (2018). Stress and the mental health of populations of color: Advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(4), 466–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146518814251

- Willman-Iivarinen, H. (2017). The future of consumer decision making. European Journal of Futures Research, 5(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40309-017-0125-5

- The World Inequality Report. (2022). Presentation of the world inequality report 2022. https://wir2022.wid.world/www-site/uploads/2022/03/0098-21_WIL_RIM_RAPPORT_A4.pdf

- Wuryaningrat, N. F., Alqurbani, I., Mambu, R., & Watung, S. R. (2021). Social perception on new normal (case Study on millennial generations at North Sulawesi Indonesia). Journal of International Conference Proceedings, 4(1), 192–196. https://doi.org/10.32535/jicp.v4i1.1140

- Xu, Z., Zhang, D., Xu, D., Li, X., Xie, Y. J., Sun, W., Lee, E. K., Yip, B. H., Xiao, S., Wong, S. Y., & Cheung, J. C. S. (2021). Loneliness, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder among Chinese adults during COVID-19: A cross-sectional online survey. PloS One, 16(10), e0259012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259012

- Yang, C., Chen, A., Chen, Y., & Lin, C.-Y. (2021). College students’ stress and health in the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of academic workload, separation from school, and fears of contagion. PloS One, 16(2), e0246676. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246676

- Yıldırım, M., Arslan, G., & Özaslan, A. (2022). Perceived risk and mental health problems among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the mediating effects of resilience and coronavirus fear. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(2), 1035–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00424-8

- Yulia, Y. A., Widianto, T., Pamastutiningtyas, T. S., Imron, P., & A, L. (2022). The tourism management information searching during pandemic COVID-19. Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Bisnis Jagaditha, 9(1), 57–65 https://doi.org/10.22225/jj.9.1.2022.57-65.

- Zhang, T., & Zhang, D. (2007). Agent-based simulation of consumer purchase decision-making and the decoy effect. Journal of Business Research, 60(8), 912–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.02.006

- Zhuang, X., Yao, Y., & Li, J. (Justin). (2019). Sociocultural impacts of tourism on residents of world cultural heritage sites in China. Sustainability, 11(3), 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030840

- Zvarikova, K., Gajanova, L., & Higgins, M. (2022). Adoption of delivery apps during the COVID-19 crisis: Consumer perceived value, behavioral choices, and purchase intentions. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 10(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.22381/jsme10120225