?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

While several studies have investigated the linear effect of lending rate on economic growth, the asymmetrical effect of lending rate on economic growth has received far less attention in the economic literature. To contribute to literature, this paper uses yearly time series data covering the period of 1970 to 2019 to study the asymmetric effect of lending rate on economic growth of Ghana. Using the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) model as an estimation strategy, we found evidence of long-run and short-run asymmetrical effects of lending on economic growth of Ghana. Specifically, the estimates from long-run and short-run dynamic NARDL suggest that positive changes in lending rate generate a decrease of nearly 0.151% and 0.213% in economic growth while negative changes lead to an increase of about 0.214% and 0.677% in economic growth, respectively. Other key findings from this study also showed that the time it takes for economic growth to respond to positive changes in lending rate is different from the time it takes to respond negative changes in lending rate in the short run, providing further evidence of the presence of asymmetries inherent in lending rate. Our results are robust to different diagnostic and reliability checks. The findings from this study help us to understand that the mix outcome among studies that seeks to examine the link between lending rate and economic growth might be due to failure to account for asymmetric tendencies inherent in lending rate.

1. Introduction

An imperative economic indicator for evaluating the economic performance of a country is its yearly rate of real GDP growth. As a result, numerous studies have attempted to identify the various factors that influence real GDP growth and the potential sources of growth differences across space and time from both empirical and theoretical perspectives (S. A. R. KHAN et al., Citation2020; ABDULAHI et al., Citation2019). Lending rate has been identified as one of the factors (BUABENG et al., Citation2021; LADIME et al., Citation2013; NASIR et al., Citation2014; SHAUKAT et al., Citation2019). However, the evidence presented in the literature is not conclusive and the debate on whether lending rate promotes or impedes economic growth is still ongoing. For example, NASIR et al. (Citation2014) used time series data for Saudi Arabia to examine the impact of lending rate on economic growth and reported that lending rate affects economic growth negatively. Contrary, OBAMUYI et al. (Citation2012) found no relationship between lending rate and economic growth in Nigeria using vector error correction model (VECM) as estimation strategy. An important source of dispute in this strand of growth literature is failure of existing studies to account for the asymmetric behavior of lending rate when examining the relationship between lending rate and economic growth. This study attempts to address this long-lasting econometric issue in the literature by asking the following questions: Does upward and downward movement of lending rate have varying or equal effect on economic growth? Does economic growth response to downward and upward changes in lending rate at the same time or in different time periods in the short run. The present study seeks to answer to these questions and other relevant issues using an appropriate econometric approach. For instance, nonlinear ARDL model can account for the asymmetric behavior of lending rate in order to isolate the effect of the downward and upward movement of lending rate on economic growth; however, empirical evidence is lacking to back this assertion, which this paper attempts to address.

According to economic theory and empirical studies, lending rate affects the core operation of an economy through consumption and production, exchange rate, inflation, policy rate and others (S. A. R. KHAN et al., Citation2020; TODARO & SMITH, Citation2012; UFOEZE et al., Citation2018). Specifically, lending rate is an imperative component of marginal cost of financing which affects the incentive for consumer’s and firms to borrow and thus affects investment spending to influence economic growth (NAMPEWO, Citation2021; SHAUKAT et al., Citation2019). As a result, banks’ lending rate could serve as an important pathway for monetary policy transmission to influence the real economy (NAMPEWO, Citation2021). For instance, the theory of monetary policy transmission mechanism suggest that policy rate changes is expected to influence banks’ lending rate and later the real economy through their influence on the flow of credit and on incentive for optimal allocation of investment expenditure (MISHKIN, Citation1996).

Ghana’s banking system, as in the case of many developing countries, is characterized by asymmetric response of lending rate to changes in macroeconomic shocks especially monetary policy rate (LADIME et al., Citation2013; NAMPEWO, Citation2021). Thus, the behavior of other macroeconomic variables especially monetary policy rate influences lending rate behavior in Ghana. Banks’ lending rates had tended to track the evolution of the monetary policy rate since Ghana adopted the inflation targeting policy in 2002 (ABANGO et al., Citation2019; KYEREBOAH‐COLEMAN, Citation2012). However, recent update from the Bank of Ghana (2019) suggest that banks’ lending rate reacts to changes in monetary policy rate asymmetrically, with lending rate reacting slower when the monetary policy rate is falling but reacts faster when monetary rate is increasing. Although the asymmetrical behavior of lending rate in Ghana is significantly driven by changes in monetary policy rate compared to other macroeconomic variables, its asymmetric behavior also influences economic growth through investment and consumption expenditure which are key component of economic growth (ROMER, Citation1994). Thus, lending rate influences investment projects and consumption such that when lending rate is high, it attracts riskier projects and few borrowers (consumers) but when lending rate falls significantly it attract risk free project and more borrowers to increase investment and consumption which promotes economic growth.

The asymmetric behavior of lending rate in Ghana is a major concern to firms, banks, consumers, and policy makers. There is thus an urgent call for policy makers to take necessary steps to stabilize and lower lending rate to increase borrowing from banks which would increase gross domestic investment and thus increase economic growth. A good prerequisite to designing a sound policy aim at stabilizing and lowering lending rate to boost economic growth require sound empirical grounds and the current study seeks to fulfil that. Thus, the key findings from this study are envisaged to help policy makers in Ghana to keep lending rate in a specific range or target in order to encourage borrowing from commercial banks for investment and consumption which tend to foster economic growth. Further, the finding of this study will also be helpful for other developing countries with similar socioeconomic and demographic features like Ghana that are facing similar economic problem regarding frequent lending rate fluctuations that mitigate economic growth.

The literature on the relationship between economic growth and lending rate is limited. Within such literature most the studies found adverse effect of lending rate on economic growth (ADEDE, Citation2015; BUABENG et al., Citation2021; NASIR et al., Citation2014) while other few studies found no relationship between lending rate and economic growth (AWAD et al., Citation2019), using different time series approaches. For instance, NASIR et al. (Citation2014) draws on time series data and found that lending rate affects economic growth negatively in South Arabia. A subset of studies within this literature tend to focus on factors that derive Bank’s lending behavior (LADIME et al., Citation2013; OLUSANYA et al., Citation2012; PERERA, Citation2018). For example, in Ghana, LADIME et al. (Citation2013) examined the determinants of bank lending behavior and found that bank size, capital structure, central bank’s lending rate and exchange rate are the major determinants of bank lending behavior in Ghana.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the leading study in the context of Ghana, which attempts to examine the nonlinear relationship between lending rate and economic growth in one scope at the country-level, utilizing asymmetrical ARDL model approach. Specifically, we use NARDL to disentangle asymmetric behavior of lending rate into positive and negative changes and examine their individual effect on economic growth, which is not common in the economic literature especially in the case of Ghana. Thus, our study differs from existing studies that examines the relationship between economic growth and lending rate by using an improve econometric strategy that can account for asymmetries inherent in lending rate. Few studies that examined the relationship between lending rate and economic growth used linear ARDL model as an estimation strategy which tend to focus on a linear relationship between lending rate and economic growth (ADEDE, Citation2015; BUABENG et al., Citation2021; NASIR et al., Citation2014). Thus, using ARDL model as estimation strategy may either neglect either the positive or negative changes in lending rate which could bias the finding from these studies. This is so because either the influence of the negative or positive changes in lending rate may be neglected when making inferences from the results of these studies that used linear models such ARDL model as an estimation strategy. To overcome this limitation, the study focuses on nonlinear relationship between economic growth and lending rate by using nonlinear ADRL model as an estimation strategy which account for the asymmetrical behavior of lending rate. Using the asymmetrical NARDL model approach will aid in producing more detailed and reliable estimates/results compared to the symmetrical ARDL model because it accounts for both the downward and upward movement in lending rate. Indeed, the literature has demonstrated that the asymmetrical NARDL model is superior over symmetrical ARDL model because it predicts impact of both positive and negative shocks to the main explanatory variable on the outcome variable (NEOG & YADAVA, Citation2020; REHMAN et al., Citation2021). Also, the asymmetrical NARDL is preferable over other conventional time series approaches like vector error correction model because it accounts for short-run volatilities and structural breaks problems in the data which may lead to bias estimates if not accounted for.

Further, the present study differs from existing studies by making use of commercial banks’ base rate as a proxy for lending rate which is commonly used as the market lending rate in Ghana. Most of the existing studies in the economic literature made use of the central bank’s lending rate which may not be able to explain significant variations in economic growth (ADEDE, Citation2015; BUABENG et al., Citation2021; NASIR et al., Citation2014). This so because central bank’s lending rate is the rate that is set out by the central bank to lend out money to commercial banks in times of economic crisis in order to mitigate the collapsing of commercial banks in difficult times. It often come into play when there is a serious economic crisis like covid-19 when there is the need for the central bank to lend money to commercial banks; hence, it impacts on economic growth may not be felt significantly in an economy compared to commercial bank’s lending rate. Commercial bank’s lending rate is set out by the commercial banks to lend out money to its customers and firms. Commercial banks in Ghana holds large number of customers; hence, its lending rate changes can explain significant variations in economic growth. Thus, a small change in commercial banks lending rate can influence the borrowing behavior of large number of individuals and firms in Ghana which will cause significant changes in investment and consumption to have an impact on economic growth significantly. Additionally, using commercial banks’ base rate as a proxy for lending rate reflects the true cost of borrowing for large number of consumers and firms in Ghana, which provides a good ground for making inferences.

The rest of the study is organized in the following form: literature review, methodology, empirical results, and conclusion.

2. Literature review

This section reviews theoretical and empirical studies related to this study. While the first subsection focused on theoretical studies, the second section presents a review of empirical studies.

2.1. Theoretical studies

Moral hazard, adverse selection, and switching cost hypothesis

Stiglitz and Weiss (Citation1981) proposed the adverse selection hypothesis which suggests that increase in lending rate create two problems on the financial market. First, it forces risk free borrowers out of the market. Secondly, it makes banks faces or sometimes bears additional cost on riskier loan. As a result, banks are reluctant to increase lending rate whenever there is an increase in the monetary policy rate. Lowe and Rohling (1992) provided further explanation to this hypothesis by stating that there exists an asymmetrical information problem between firms and banks such that firms have perfect knowledge and information about their investment plans and projects while banks have limited information (BERGER et al., Citation2011; CLAUS, Citation2011). Thus, firms know risk free and riskier investment while banks do not know due to lack of information (DELL’ARICCIA, Citation2001). This issue breeds moral hazard and adverse selection (PAULY, Citation1978).

Moral hazard hypothesis arises when increase in lending rate by banks tends to induce borrowers to invest in riskier projects while adverse selection hypothesis occurs when an increase in lending rate reduces expected return on both risk free and riskier projects (ERICSON et al., Citation2000; PAULY, Citation1978). As per the adverse selection, risk-free projects are more likely to be withdrawn first from the financial market following a significant increase in lending rate (WILSON, Citation1989, Van NESS et al., Citation2001). However, the moral hazard implies that banks might not earn expected return following an increase in lending rate because expected return depend on other factors such as probability of default from the riskier projects or loans (CASTILLO et al., Citation2018).

One of the main objectives of banks is to make expected return when lending rate increases. Hence, to meet this objective, banks incur cost to find out more information about riskier projects and customers which turns out to be costly for the banks (ZHAO et al., Citation2013). Thus, firms incur cost in gathering information about riskier projects and profile of riskier customers. As such, banks passed the cost of gathering information about customers or projects to buyers through increasing the lending rate further. Rational buyers or customers spend time and incur cost to search for alternative banks with easy loan application documentations as well as with low lending rate charges (COHEN et al., Citation2019). This breeds the switching cost hypothesis which suggests that both customers and banks incur cost (COHEN et al., Citation2019; NIELSON, Citation1996).

Overall, these hypotheses help us understand lending rate behavior on the financial market. Specifically, it tells us that lending rate is not stable but continuous changes (increase or decrease) depending on nature of the market, structure of the banking sector, banking environment and related cost (CASTILLO et al., Citation2018; CLAUS, Citation2011). For instance, in a less competitive banking environment lending rate turns out to be rigid because such banking environment encourages monopolistic banks (LEVIEUGE & SAHUC, Citation2021). Hence, irrespective of monetary policy actions, lending rate continue to increase or remain high in less competitive banking environment. At the same time, the cost incurred by the customers in searching (or switching from one bank to another bank) for appropriate bank with lower interest rate and the cost incurred by bank on gathering information on the customer collusion and segmentation in the market also influences lending rate behavior. All these factors lead to a reduction in elasticity of demand facing banks which tends to drive lending rate.

2.2. Empirical studies

The determinants of economic growth have been a subject of continues debate in the economic literature. The possible determinants of economic growth highlighted in the literature include exchange rate (WANG et al., Citation2021), inflation (EGGOH & KHAN, Citation2014), interest rate (MOYO & Le Roux, Citation2018), financial development (ADU et al., Citation2013), foreign direct investment (MUHAMMAD & KHAN, Citation2021), domestic investment (ULLAH et al., Citation2014), energy (I. KHAN et al., Citation2022), Co2 emissions (REHMAN et al., Citation2021), foreign aid (AZAM & FENG, Citation2022), and others. For example, I. KHAN et al. (Citation2022) found that clean energy transition promotes economic growth while TANG et al. (Citation2022) found that business regulations influence economic growth positively. I. KHAN et al. (Citation2022) also draw on time series data covering the period of 1990 to 2016 and found that energy usage increases economic growth at the expense of energy sustainability. Additionally, a recent study by AZAM and FENG (Citation2022) draws on time series data for 37 developing countries to study whether foreign aid may stimulate or mitigate economic growth of these developing countries. Although several studies have shown that foreign aid foster economic growth (EKANAYAKE & CHATRNA, Citation2010; NWAOGU & RYAN, Citation2015), the study found that the influence of foreign aid on economic growth is limited in these countries. Other supplementary findings from this study also revealed that exports from these 37 countries generates a significant increase in economic growth of these countries which is in line with findings from BAHRAMIAN and SALIMINEZHAD (Citation2020) and EDO et al. (Citation2020) for Turkey and Sub-Sahara Africa, respectively. However, what has remained dominant in the empirical literature over years regards to finding economic variables that affect economic growth is on how inflation affects economic growth (BASSEY & ONWIODUOKIT, Citation2011; CHU et al., Citation2017; ZULKHIBRI & RANI, Citation2016). These studies argued that inflation has a negative repercussion on economic growth across different countries, possibly because inflation increase cost of production and reduces purchasing power of consumers. For instance, KARAHAN and ÇOLAK (Citation2020) applied an nonlinear ARDL approach on a quarterly time series data covering the period of 2003 and 2017 and found nonlinear relationship between inflation and economic growth in the long run. However, a recent study by NKEMGHA et al. (Citation2022) draws on panel data for Central African countries and produce a contradictory findings. Specifically, the study found that inflation promotes economic growth of these Central African countries while insecurity hinders it. Others studies also stressed that interest rate is one key macroeconomic variables that influences economic growth, likely due to the fact that high interest rate increase cost of borrowing and thus influences investment significantly (SALAMI, Citation2018; UFOEZE et al., Citation2018). For instance, SALAMI (Citation2018) investigated the effect of interest rate on economic growth of Swaziland, using the ordinary least squares estimation strategy. The study found that interest rate exerted a negative and significant effect on economic growth. SHAUKAT et al. (Citation2019) also argued that low interest rate is beneficial and highly require for developing or transitory economies to attain higher levels of economic growth. This finding is consistent with finding from SAYMEH and ORABI (Citation2013) in Jordan but contradicts that of UFOEZE et al. (Citation2018) in Nigeria.

A small body of literature have shown that lending rate influence economic growth across different countries (NASIR et al., Citation2014; OBAMUYI et al., Citation2012). Lending rate defined as the price paid for borrowing money (loan) affects economic growth basically through marginal cost of financing. Most of the study argued that lending rate has a negative relationship with economic growth (ADEDE, Citation2015; BUABENG et al., Citation2021; NASIR et al., Citation2014). Specifically, an increase (decrease) in lending rate causes a decrease in economic activities because it increases cost of borrowing which discourages firms and consumers from borrowing money for investment and consumption, respectively. In a specific country-case study in Saudi Arabia, NASIR et al. (Citation2014) found that lending rate affects economic growth negatively, using Granger causality and Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) as an estimation strategy. Contrary, OBAMUYI et al. (Citation2012) found that there is no relationship between bank lending rates and economic growth in Nigeria, using vector error correction model (VECM) as estimation strategy. In China and Vietnam, Van Dinh (Citation2020) draws on ordinary least square (OLS) model as an estimation strategy and reported that inflation stimulates economic growth through lending rate in both countries. In the same vain, AWAD et al. (Citation2019) draws on time series data for Palestine and examine the impact of bank lending on economic growth. The findings from the study revealed that banking lending has no significant influence on economic growth likely due to the fact that banks are unwilling to lend money to the production sector in Palestine.

In Ghana, we are aware of a related work by LADIME et al. (Citation2013) LADIME et al. (Citation2013) who used system GMM as an estimation strategy to investigate the determinants of bank lending behavior in Ghana. Their findings revealed that bank size and capital structure had a statistically significant and positive relationship with bank lending behavior while central bank’s lending rate and exchange rate had a negative and significant impact on banks’ lending behavior in Ghana. In a related study in the same country, ADUSEI and APPIAH (Citation2011) draws in data for 222 credit unions to examine the determinant of group lending among the credit union industry and reported that size of management, lower repayment performance, better liquidity position and no delinquent loans are the main factors that influences group lending while gender structure of credit union does not have a significant impact on group lending decisions. However, BAOKO et al. (Citation2017) shows that real lending rate is one of the significant factors that influences banks ability to give out credit by applying an ARDL model on a time series data covering the period of 1970 to 2011.

Regarding lending rate behavior, it is dynamic especially regarding how it reacts to banking sector environment, domestic market terms and other macroeconomic variables especially policy rate to influence economic growth (BANERJEE et al., Citation2015; HASELMANN & WACHTEL, Citation2010; S, Citation2018; SARATH & Pham, Citation2015). For instance, ILLES et al. (Citation2015) argue that large banks slowly adjust their lending rate to market terms than small banks, possibly because small banks have narrow scope of interest rate setting than large banks. Lending rate is more likely to be stickier for capitalized banks than less capitalized banks because capitalized banks are less likely to be affected by monetary policy shocks than less capitalized banks (GAMBACORTA & MISTRULLI, Citation2014). Lending rate also tends to be more rigid in a concentrated banking environment (BANERJEE et al., Citation2015). For instance, BANERJEE et al. (Citation2015) argued that a more concentrated banks tends to have a sluggish adjustment of lending rate (interest rate specifically) downwards and a faster adjustment upwards. NAMPEWO (Citation2021) also argued that lending rate responses to policy rate is asymmetrical but tends to be stickier downwards compared to upwards. Indeed, he further stressed that risk, cost, bank sector concentration, the level of bank capitalization and government borrowings are the factors associated with asymmetrical response of lending rate (interest rate) to policy rate.

From the past studies reviewed, it is observed that empirical studies on economic growth and lending rate are scanty in literature, especially in Ghana. However, the few existing studies tends to focus on the linear relationship between lending rate and economic growth, neglecting the asymmetrical behavior of lending rate. We depart from previous studies by using NARDL to account for asymmetries inherent in lending rate to examine the asymmetrical effect of lending rate on economic growth of Ghana. This is our unique contribution to this strand of literature as no study in the literature has taken this econometric issue into consideration. Further, the study used recent data (Thus from 1970 to 2019) to examine the asymmetrical effect of lending rate on economic growth in a more contemporary era in order to inform policy actions. Lastly, although our empirical evidence is for Ghana, lending rate is globally, hence, our findings will be relevance for developing countries with similar socioeconomic and demographic setting like Ghana. This shows that our findings/results are significant beyond Ghana’s boundaries.

3. Methodology

This section provides descriptions of the data, model specification and estimation strategy in a sequential order. The first section describes the source of the data and variables used in or regression model while the second section provide brief model specification. The last section gives detailed description of the reason why we used Non-linear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) model as our estimation strategy over other time series approaches.

3.1. Data type and Source

The study utilized yearly time series data covering the period of 1970 to 2019. On one hand, data on lending rate, and monetary policy rate was obtained from Bank of Ghana (2019) database. On the other hand, data on inflation, exchange rate and foreign direct investment were obtained from World Bank (2019) database. Detailed description of the variables with their expected relationship with economic growth are shown in . A prior, the study expects the effect of lending rate on economic growth to be in two parts. Thus, the study expects the upward movement of lending rate to have a negative effect on economic growth following existing studies (ADEDE, Citation2015; NASIR et al., Citation2014). This might be due to the fact that upward trends in lending rate (increase in lending rate) is associated with high cost of borrowing which tends to deter borrowing from banks to increase consumption and investment. However, downward movement in lending rate is expected to increase economic growth because it is encourages borrowing since is associated with low cost of borrowing. Specifically, downward trends in lending rate decrease marginal cost of borrowing which tends to increase borrowing with a resultant increase in investment and consumption to boost economic growth. Following existing studies the study expects inflation to decrease economic growth (BITTENCOURT, Citation2012; SEQUEIRA, Citation2021). This is so because high inflation increases cost of production and decreases purchasing power of consumers. High cost of borrowing and low purchasing power has been linked with decreasing output produced and low consumption, respectively, which tend to lower overall output or gross domestic product of an economy (SEQUEIRA, Citation2021). For example, PARADISO et al. (Citation2012) found that higher inflation rate tends to be associated with lower consumption in United Stated of America. A prior, we expect the relationship between economic growth and monetary policy rate to be negative, following empirics (ONYEIWU, Citation2012; SENA et al., Citation2021). The reason behind this expectation is that high monetary policy rate is more likely to reduce money in circulation and increase interest rates which decrease consumption and investment that are the key component of gross domestic product. Specifically, high monetary policy rate tends to increase short-term and long-term market interest rate that deter borrowing to decrease investment which is a significant component of economic growth (BAUER, Citation2012; PEERSMAN, Citation2002). For exchange rate, we expect it to have a negative relationship with economic growth because high exchange rate decreases the value of domestic currency making import of good and services more expensive (AKADIRI & AKADIRI, Citation2021; RAPETTI et al., Citation2012). Hence, high exchange rate is more likely to decrease importation of goods and services because it decreases purchasing power of domestic currency in terms of purchasing foreign goods and services which tend to decrease the overall output of an economy (RAPETTI et al., Citation2012). Lastly, the relationship between foreign direct investment and economic growth is expected to be positive because inflow of foreign direct investment to developing countries enable them to create new jobs, increase developmental projects, bring in innovations and promote rapid industrialization which boost economic performance (CHEUNG & Lin, Citation2004; MÜLLER, Citation2021). For example, CHEUNG and Lin (Citation2004) draws on provincial data for China to examine the effect of FDI on innovation and found that FDI has a significant positive impact on patent applications including inventions, external design and utility model which are more likely to increase economic growth of an economy.

Table 1. Brief description of variables

3.2. Model specification

We expect gross domestic product (or economic growth) to depend on lending rate and other relevant variables following previous studies (ADABOR & BUABENG, Citation2021; NASIR et al., Citation2014) . The functional of the model is specified in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) .

Where GDP is gross domestic product, LR is lending rate, MPR is monetary policy, FDI is foreign direct investment, INF is inflation and EXCR is exchange rate. The estimable form of Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) is specified in equation (2).

Where the variables GDP, LR, MPR, FDI and EXCR are explained earlier in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) .

is the constant term and

is the disturbance term. The parameters

s (i= 1, 2 … …, 5) are the coefficient of the respective variables.

3.3. Estimation strategy

The discussion on the estimation strategy in this section is structured in two sections. The first section describes the strategies used to carry out stationarity checks while the last section describes the Non-linear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) model and the reason why we decided to use this estimation strategy.

3.3.1. Stationarity checks

Using non-stationary variables in time series analysis may lead to inconsistent and biased estimates (GRANGER et al., Citation1974). Additionally, it will result in spurious regression which might not be suitable for making analysis and inferences. For stationarity test, we employed the Phillips and Perron test by PHILLIPS and PERRON (Citation1988) and the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test by DICKEY and FULLER (Citation1979). The ADF test can be expressed as follows:

Where Xt is the variable under consideration at period t. The ADF and PP test are conducted with a null hypothesis of H0: δ = 0 as against an alternative hypothesis that H1: δ < 0. The null hypothesis states that there is the presence of unit root whiles the alternative hypothesis states that there is no unit root. The series become stationary when the null hypothesis is rejected.

3.3.2. Autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model and Non-linear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) model

A study by NAMPEWO (Citation2021) has shown that lending rate has an asymmetric effect on policy rate in Uganda. Based on this finding which provides evidence of the existence of asymmetries in lending rate instead of symmetries, we employed the NARDL as estimation strategy to estimate the asymmetrical effect of banks’ lending rate on economic growth of Ghana. Basically, the NARDL model by SHIN et al. (Citation2014) is an extension of the bound test approach to co-integration within the ARDL model developed by PESARAN et al. (Citation2001). Using such a model offer flexibility because it is applicable regardless of the stationarity properties of the underlying variable. Thus, irrespective of whether the underlying variables are integrated of order I(0) or/and I(1) or mutually co-integrated the NARDL model can be used (SALISU & ISAH, Citation2017). But this is not to bypass the need for pre-testing of the order of the integration of the variables, which is very important to ensure that all the variables used in the present study are not I(2). Additionally, pre-testing the order of the integration provides a good basis to verify the presence of a long-run co-integration among the variables. We used NARDL model over ARDL model because the ARDL model does not account for the asymmetries in the movement of lending rate in Ghana. However, lending rate in Ghana has exhibited a nonlinear trend over the period of 1970 to 2019. Thus, there are periods where lending rate in Ghana increase and there are some periods where lending rate in Ghana decreased. As a result, the effect of lending rate on economic growth might be asymmetrical as it could be negative when lending rate is increasing and could also have a positive effect economic growth of Ghana when lending rate decreasing continuously. Hence, applying the ARDL model to estimate our empirical model in Equationequation (2)(2)

(2) would generate spurious regression results leading to wrong inferences. Like the ARDL, the NARDL model is efficient and performs well in small sample as well as able to account for endogeneity among all the variables. The model takes into account the short and long run asymmetries in the movement of the variables (lending specifically) and applicable in mixed order of integration. The general asymmetric long run regression model for examining the asymmetric effect of lending rate on economic growth is shown in Equationequation (3)

(3)

(3) below:

Where and

are scalar (1) variables and

is decomposed as

where

and

are partial sum processes of negative and positive changes in

, respectively. Thus, the study filtered the positive changes in lending rate (increase) from the negative changes in lending rate (decrease) to be able to examine their individual effect on economic growth of Ghana. The partial sums are formally defined as follows:

Where the variables in Equationequation (4)(4)

(4) and (Equation5

(5)

(5) ) are explained already in the previous equations. To obtain the estimable NARDL model, Equationequation (4)

(4)

(4) and (Equation5

(5)

(5) ) was used. Thus, we substituted equation (4) and (5)Footnote1 of the partial sum into the original ARDL model to arrive at the following nonlinear ARDL model for economic growth (SHIN et al., Citation2014) as shown below:

Where the variables in Equationequation (6)(6)

(6) are explained already in the previous equations. In model (6), the partial sums of Positive

) and Negative

are the asymmetric changes in lending rate. Model (6) is an error-correction model that is labelled as Nonlinear ARDL model as compares to the linear ARDL model. Nonlinearity is introduced through the partial sums variables in model (4) and (5). SHIN et al. (Citation2014) have demonstrated that Pears, Shin and Smith approach of estimating the linear ARDL and testing of co-integration is equally applicable to the nonlinear ARDL model. The difference between these two models is that, for the nonlinear ARDL, lending rate changes would have symmetric (linear) effect on economic growth if the coefficient of the Positive and Negative in model (6) have the same size and sign. Any result aside this outcome makes the model asymmetric. For instance, if the sign and size of

and

are different, then we can conclude that the effect of lending rate changes on money demand is asymmetrical. Additionally, few asymmetric assumptions need to be tested. Firstly, if

and

take different lag order in the short run, that would be indication of adjustment asymmetries, implying that the time it takes for economic growth to respond to increase in lending rate is different than the time it takes to respond decrease in lending rate. Secondly, the short run asymmetric impact of lending rate on economic growth would be established if we reject the null hypothesis of ∑

=∑

. This hypothesis would be tested by the Wald test.

The long-run effect is obtained by setting the non-first-difference lag component of Equationequation (6)(6)

(6) to zero and normalizing

,

and

. Following NARDL by SHIN et al. (Citation2014) we can also apply bound testing procedure by PESARAN et al. (Citation2001). The

,

are the optimal lag selected through Akaike Information Criterion. We restricted the lag length to a maximum lag of 1 to save the degree of freedom which also best fit for data with low frequency like yearly, quarterly and monthly data (PERRON, Citation1989).

4. Empirical results and discussion

In this section, we present the empirical results from the nonlinear ARDL. First, we present descriptive statistics of all the variables employed in the study. This is followed by the results from the unit roots and the co-integration test. Lastly, we present discussions on the long-run and short-run estimates from the NARDL as well as the diagnostic test results.

show the descriptive statistics of the variables used in our study. Lending rate had a minimum value of 1.297 and the maximum value is 2.977. Lending rate averaged 2.371 whiles its deviation from the mean is 0.501. Monetary policy rate variable averaged 3.134 with a minimum value of 2.526 and a maximum value of 3.807. It also had a standard deviation of 0.394. For foreign direct investment, the maximum and the minimum values were 1.381 and 2.253 respectively with an average of 1.119. The deviation of foreign direct investment from its means is 1.024. In addition, the average inflation rate was 2.861 and with a minimum and maximum values of 1.964 and 4.0853 respectively. It also had a standard deviation of 0.524. Gross domestic product also averaged 1.642 with minimum and maximum values of 1.194 and 2.642 respectively. Lastly, exchange rate averaged 1.137 and ranges between 0.033 and 4.351. Exchange rate also had a standard deviation of 1.269. Regarding the skewness and Kurtosis, all the variables are positively skewed with fatter tails at the end.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

4.1. Unit root and co-integration test results

In this section we present the results from The Philip-Perron (PP) and Augmented Dickey Fuller tests. display the results attained. We find that lending rate (LR), monetary policy rate (MPR), foreign direct investment (FDI) and exchange rate (EXR) were all integrated of order one I(1) whiles gross domestic product (GDP) and inflation (INF) were integrated of order zero I(0) series. These results have two implications. First, it provides evidence in support of our choice of NARDL model which allow for inclusion of I(1) and I(0) independent variables in the same empirical equation. Lastly, the implication of these results is that the study can apply the bounds test to examine the long-run relationship between lending rate and economic growth in Ghana.

Table 3. Unit root test results

The main aim of this section is to test for structural break in the series using ZIVOT and ANDREWS (Citation2002) unit root approach. The results displayed in empirically confirms the presence of structural break for all the variables used in our empirical model. However, for gross domestic product (GDP) and exchange rate (LR), stationarity is attained at level while for lending rate (LR), monetary policy rate (MPR) and foreign direct investment (FDI) stationary is attained after differencing one time which conform to the results from the Augmented Dicky Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron unit root tests. The presence of structural breaks and mix order of integration that does not exceed integration order of one confirms the suitability to utilize NARDL to examine the nonlinear relationship between lending rate and economic growth in Ghana.

Table 4. Zivot and Andrews unit root structural break test

The study followed the bounds test approach to co-integration to examine the long run relationship between the dependent and the independent variables. From above, the result of the bounds test suggests that the F-statistics of 12.376 is greater than the upper bound critical value of 6.012 and 10.381 at 1% and 5% level of significance, respectively. We can therefore conclude there is the existence of a long run association or co-integration between the dependent and independent variables. We then proceeded to estimate the long run asymmetric effect of lending rate changes on gross domestic product in Ghana while controlling for other relevant factors that affect gross domestic product (GDP).

Table 5. Bounds test Co-integration test results

4.2. Estimated long-run and short-run coefficients using NARDL

The main goal in this section is to estimate the asymmetrical effect of lending rate on economic growth in the long run. From the long-run estimates reported in , we find that the positive () and negative (

change variables carry significant coefficient with different signs and size which support the presence of long-run asymmetric effect of lending rate on economic growth in Ghana. Thus, our NARDL long-run estimates empirically confirms an asymmetric effect of lending rate on economic growth because positive changes in lending rate (increase in lending rate) exerts a significant negative effect on economic growth while the negative changes (decrease) in lending rate exerts a significant positive effect on economic growth of Ghana. Specifically, our results revealed that one percent increase in

generates about 0.151 decrease in gross domestic product while one percent increase in

generates approximately 0.214 increase in gross domestic product, all else equal. These findings is similar to that of NAMPEWO (Citation2021) who examined the factors which drivers the asymmetric response of lending rate to changes in policy rate in Uganda. The economic implications of these findings are that positive changes in lending rate increases cost of borrowing from commercial banks which deter firms from borrowing from banks for new project thereby decreasing investment which is a key component of economic growth. Borrowers, firms, or customers may also search around for alternatives banks or source of funding for their projects following a positive change in lending rate (increase in lending rate specifically). In doing this, they incur cost and time in gathering information which turns out to breed the switching cost hypothesis, suggesting that customers incur cost in searching for an alternative low lending rate which is more likely to deter borrowing to decrease investment and consumption and thus a decrease in gross domestic product. Thus, the cost of searching for low alternative lending rate increase total cost of borrowing thereby decreasing investment to lower economic growth. On the banks side, banks are expected to make higher returns on loans or credit following an increase in lending rate (positive change), hence, banks spend time and incur cost to gather information about riskier projects of firms and customers which is likely to breed moral hazards and adverse selection (PAULY, Citation1978). Banks transfer the cost incur in gathering information to the firms and customers by increasing lending rate further which is more likely to decreasing borrowing significantly thereby decreasing investment and thus, decrease economic growth. The reasons why banks spend time to gather information on projects is that higher lending rate attracts riskier project than risk free projects. But it is impossible to obtain perfect information on the financial market, hence, it might be difficult for banks to identify all riskier project, and this might be the reason why positive changes in lending rate may breed adverse selection (ERICSON et al., Citation2000; PAULY, Citation1978). However, when there is a decrease (negative change) in lending rate cost of acquiring long-term loans or credits for new project become less expensive. Hence, borrowers and firms can go for loans to undertake new projects and acquire new capital or machinery which increases investment and thus increases economic growth. On the side of banks, low lending rate is likely to attract risk free project, hence, banks do not incur cost to gather information on the project. This is likely to stabilize or further reduce lending rate to attract more borrowers or firms to borrow for their project thereby increasing economic growth via increasing investment.

Table 6. Estimated long-run results

For the control variables, the study found that foreign direct exerts a positive and significant effect on economic growth at 5 percent level of significance. The coefficient of 0.732 implies that one percent FDI generates 0.732 percent increase in economic growth, all things been equal. FDI inflow promotes economic growth by increasing the expansion of local firms as well as the establishment of new multinational cooperation. In addition, inflow of FDI is also form significant part of source of funding for government infrastructure development projects such as roads, public health, and extension of electricity supply which promote economic growth. This finding is consistent with that of NKETSIAH and QUAIDOO (Citation2017) but contradict that of MWINLAARU and OFORI (Citation2017).

Theoretically, exchange rate is expected to affect economic growth negatively. However, the long-run results confirms that exchange rate exert a positive and significant effect on economic growth of Ghana at 5 percent level of significance which contradict findings from AKADIRI and AKADIRI (Citation2021) and RAPETTI et al. (Citation2012). Specifically, if the country experience one percent decrease in exchange rate, economic growth measured by gross domestic product would decrease by approximately 0.439 percent, all else equal. The implication of this result is that higher exchange rate increases the demand for domestic goods as the importation of foreign goods becomes relatively expensive. Profit maximizing local firms would increase their output to meet the demand on the local market thereby increasing total gross domestic product. Thus, depreciation of the local currency (Ghana cedis) makes importation of foreign goods expensive and thus increases the price of foreign goods and services. This would increase the demand for local product which turns to increase gross domestic product. This finding similar to that of ADEWUYI and AKPOKODJE (Citation2013).

For inflation, the result revealed that inflation exerts a negative and significant impact on economic growth of Ghana. Specifically, if the general price level increases by one percent, gross domestic product decreases by approximately 0.881 percent in the long run. The implication of this result is that an increase in inflation increases the cost of raw materials and other inputs used in production by firms, hence, decreases total output produced by firms. In addition, inflationary effect decreases consumer’s purchasing power. This reduces their demand for goods and services thereby reducing their standard of living which affect their productivity. Low productivity of labour decreases output produced by firms, hence, decreases economic growth. This result is consistent with that of SEQUEIRA (Citation2021).

Lastly, the results revealed a negative and significant relationship between monetary policy rate and economic growth as expected. Thus, monetary policy rate exerts a negative effect on gross domestic product at one percent level of significance. Specifically, one percent increase in monetary policy rate generates 0.504 percent decrease in gross domestic product, all other things being equal. This implies that an increase in monetary policy rate increases cost of borrowing from commercial banks and this reduces investment and consumption thereby reducing gross domestic product. How do these results change when if we shift to estimates of the short-run nonlinear ARDL results in Table ?

Table 7. Estimated short-run results using the NARDL

reports the short-run estimates from the NARDL which empirically confirm an asymmetric effect of lending rate on economic growth in Ghana. This is so because the coefficient of and

have different signs and size. Thus, our results revealed the different direction of the effect of negative (

and positive (

change in lending on economic growth, ceteris paribus. In addition to this, the short-run estimates revealed some important information.

We can also observe that the and

takes different lag order, supporting adjustment asymmetry. This implies that the time it takes for economic growth to respond to positive change in lending rate is different than the time it takes to respond negative change in lending rate. Specifically, the coefficients of

and

revealed that one percent increase in

generates 0.213 decrease in gross domestic product while one percent increase

generates 0.677 increase in gross domestic product, all else equal. The lag values of

and

are interpreted in the same manner. The economic intuition behind these estimates is that positive changes in lending rate decreases economic growth because high lending rate tends to force customers to seek for more information on alternative lending rate that might offer low rate. Seeking for this information is associated with high cost which might deter borrowing from banks and thus decreases economic growth, supporting the switching cost hypothesis (PAULY, Citation1978). Simply put, short run positive changes (increase) in lending rate decreases borrowing from commercial banks’ leading to shortfall in spending and investment which are the key components of economic growth and thus decreasing economic growth. From commercial banks perspective, they would be expecting to make higher return following an increase in lending rate (positive change). However, since higher lending rate attract riskier investment project in the short-run, banks may also spend time and resource to gather information on riskier project but may pass the cost associated with finding information on riskier loans to customers by increasing lending rate further. This likely to deter borrowing significantly in the short run because it increases cost of borrowing thereby decreasing economic growth since it may decrease investment and consumption which are the key component of GDP. On the other hand, the short run negative changes in lending rate are expected to increase economic growth because the negative changes (downward movement/decrease in lending rate) encourage borrowing from commercial banks and thus increases consumption and investment which are the key component of economic growth.

Turning to the control variables, foreign direct investment exerts a positive and significant effect on gross domestic product in the short run. Specifically, the coefficient of implies that a one percent increase in

generates nearly 0.459 percent increase in gross domestic product, ceteris paribus. This result suggests that inflow of foreign direct investment forester economic growth in the short run because it boost firm productivity and promote rapid industrialization. The study also found that exchange rate has a positive and a significant effect on economic growth in the short run. Thus, the coefficient of

implies that if the country experience exchange rate increase by one percent, gross domestic product would increase by approximately 0.819 percent in the short run, holding all else equal. The positive relationship between exchange rate and economic growth found in this study might be due to the increase in demand for domestic goods following an increase in exchange rate as the importation of foreign goods becomes relatively expensive, hence, forcing consumers to buy more domestically produced goods as compared to foreign goods. Further, the results also revealed that inflation exerts a negative impact on gross domestic product in the short run. Thus, inflation has a significant and inverse relationship with economic growth of Ghana at one percent level of significance. Specifically, one percent increase in inflation generates about 0.642 percent decrease in gross domestic product, all else being equal. The adverse effect of inflation on economic growth found in this study might be due to the fact that increasing inflation reduces the purchasing power of most Ghanaian, especially the poor and the vulnerable groups. Hence, they might not be able to buy more in the current period compared to the previous period where inflation was relatively low. Finally, monetary policy rate also exerts a negative and significant impact on gross domestic product in Ghana. Its coefficient of −0.890 implies that 1 percent increase in monetary policy rate causes a decrease of about 0.890 percent in gross domestic product, all else equal.

The error correction term [ECM (−1)] illustrates the speed of adjustment which portrays the endogenous responds to shocks of the dependent variables. The coefficient of the ECM is −0.365. This implies that co-integration and stability exist among the variables in the model. Hence, there is a one percent significance level of stability in the model and equilibrium in the long-run would adjust by approximately 36 percent annually after any short-run shock. The coefficient of determination (R2) in column 2 of indicates that the explanatory variables used in the present study explain approximately 94% of the total variation in economic growth. The F-statistics values reported in also show that the estimated model is well fitted.

4.3. Testing the validity and reliability of the estimates from the NARDL Model

The study carried out a diagnostic and reliability test to ensure that our estimations from the ARDL are reliable. The results are reported in below.

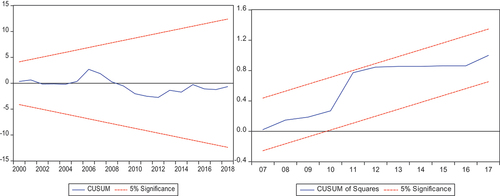

Table reports various statistical and econometric tests. From the diagnostic and reliability, it observed that the long run and short run dynamic estimates from the NARDL model is free from econometric and statistical problems. Specifically, the estimated results from the NARDL model are free from heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, functional form and it is also normally distributed since all the probability values are greater than 0.05. In addition, the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ graph (see, the Figure below) also revealed that gross domestic product over the period of 1990 to 2019 is stable. This is so because the plots of the cumulative sum and cumulative sum of square lie within the 5 percent critical bound. However, the Wald-test estimates for both short and long run are statistically significant supporting the long-run and short-run asymmetric effect of lending rate changes. Thus, the asymmetric effect of lending rate on economic growth is evidence in Ghana.

Table 8. Diagnostic and reliability test results

5. Concluding remarks

The literature on economic growth of developing countries still attracts researcher’s attention, mostly due to the important policy makers attach to economic growth. In order to aid in sound policy formulation and implementation on economic growth of developing countries, researchers have examined the various factors that influences economic growth. They found that factors such as exchange rate, foreign direct investment, financial development, energy, credit, employment, lending rate, interest rate and others influence economic growth significantly (S. A. R. KHAN et al., Citation2020; ADU et al., Citation2013; I. KHAN et al., Citation2022; MUHAMMAD & KHAN, Citation2021). However, the literature that focused on the relationship between economic growth and lending rate failed to account for the asymmetries inherent in lending rate. A recent study by NAMPEWO (Citation2021) has argued and empirically demonstrated the presence of asymmetries in lending rate but researchers failed to take this into account when examining the relationship between lending rate and economic growth.

This paper makes a unique contribution to literature by accounting for the asymmetries inherent in lending rate to examine the asymmetrical effect of lending rate on economic growth which has not been studied in the literature in the case of Ghana. To do this, we employed the nonlinear ARDL bound testing approach, which we applied to a yearly time series data covering the period of 1970 to 2019 obtained from World Bank (2019) and Bank of Ghana (2019). Our results confirm that banks’ lending rate affect economic growth asymmetrically. Specifically, positive changes in lending rate affect economic growth negatively while negative changes in lending rate affect economic growth positively in both short-run and long-run. Our results are robust to diagnostic and reliability checks. Our findings help us to understand the mix outcome in the extant literature as most of the existing studies did not pay attention to the asymmetric behaviour of lending rate, hence, unable to come into consensus on the relationship between lending rate and economic growth. Another major economic implication of the finding from this study is that maintaining low level and stable lending rate is one of the basic requirements for developing countries to attain high level of economic growth, hence, policy makers should pay attention to it when devising policies. The study also extends the literature on determinant of economic growth. In this regard, we find that monetary policy rate and inflation exert a negative effect on economic growth while foreign direct investment and exchange rate exert positive effect on economic growth.

In conclusion, the asymmetric behavior of lending rate in Ghana continues to be a subject of debate and possess threats to economic growth, particularly the positive changes (increase) in lending rate decrease economic growth of Ghana. Since, nature of the market, structure of the banking sector, banking environment and cost of searching for information on the financial market have been shown to be the drives of the asymmetric behavior of lending rate, banks and monetary authorities should pay attention to these factors when devising policies aim at stabilizing and reducing lending rate to foster economic growth. Future research studies should also focus on examining other factor that drives asymmetries in lending rate as well as uncover the variables that mediate the relationship between economic growth and lending rate for sound policy formulation and implementation.

Data can be accessed at the links below

World development indicators. http://datatopics.worldbank.org/world -development-indicators/. Washington DC: World Bank.

Bank of Ghana: https://www.bog.gov.gh/monetary-policy/policy-rate-trends/

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The NARDL model presented in the present study is a summary of the model. For the full derivation and further understanding of the NARDL model see Shin, Y., Yu B. & Greenwood-Nimmo M. (2014).

References

- ABANGO, M. A., Yusif, H., & Issifu, A. (2019). Monetary aggregates targeting, inflation targeting and inflation stabilization in Ghana. African Development Review, 31(4), 448–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12399

- ABDULAHI, M. E., Shu, Y., & KHAN, M. A. (2019). Resource rents, economic growth, and the role of institutional quality: A panel threshold analysis. Resources Policy, 61, 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.02.011

- ADABOR, O., & BUABENG, E. (2021). Empirical analysis of the causal relationship between gas resource rent and economic growth: evidence from Ghana. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available at SSRN 3874481. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3874481

- ADEDE, S. O. (2015). Lending interest rate and economic growth in Kenya. University of Nairobi.

- ADEWUYI, A. O., & AKPOKODJE, G. (2013). Exchange rate volatility and economic activities of Africa’s sub-groups. The International Trade Journal, 27(4), 349–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853908.2013.813352

- ADU, G., Marbuah, G., & Mensah, J. T. (2013). Financial development and economic growth in Ghana: Does the measure of financial development matter? Review of Development Finance, 3(4), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2013.11.001

- ADUSEI, M., & APPIAH, S. (2011). Determinants of group lending in the credit union industry in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 12(2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2011.588914

- AKADIRI, S. S., & AKADIRI, A. C. (2021). Examining the causal relationship between tourism, exchange rate, and economic growth in tourism island states: Evidence from second-generation panel. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 22(3), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2019.1598912

- AWAD, I. M., Karaki, A. L., & S, M. (2019). The impact of bank lending on Palestine economic growth: An econometric analysis of time series data. Financial Innovation, 5(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-019-0130-8

- AZAM, M., & FENG, Y. (2022). Does foreign aid stimulate economic growth in developing countries? Further evidence in both aggregate and disaggregated samples. Quality & Quantity, 56(2), 533–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01143-5

- BAHRAMIAN, P., & SALIMINEZHAD, A. (2020). On the relationship between export and economic growth: A nonparametric causality-in-quantiles approach for Turkey. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 29(1), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2019.1648537

- BANERJEE, A., Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., & Kinnan, C. (2015). The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7, 22–53.

- BAOKO, G., Acheampong, I. A., & Ibrahim, M. (2017). Determinants of bank credit in Ghana: A bounds-testing cointegration approach. African Review of Economics and Finance, 9, 33–61.

- BASSEY, G. E., & ONWIODUOKIT, E. A. (2011). An analysis of the threshold effects of inflation on economic growth in Nigeria. West African Financial and Economic Review, 8, 95–124.

- BAUER, M. D. (2012). Monetary policy and interest rate uncertainty. FRBSF Economic Letter, 38, 1–5.

- BERGER, A. N., ESPINOSA-VEGA, M. A., FRAME, W. S., & Miller, N. H. (2011). Why do borrowers pledge collateral? New empirical evidence on the role of asymmetric information. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 20(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2010.01.001

- BITTENCOURT, M. (2012). Inflation and economic growth in Latin America: Some panel time-series evidence. Economic Modelling, 29(2), 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2011.10.018

- BUABENG, E., ADABOR, O., & NANA-AMANKWAAH, E. (2021). Understanding the impact of commercial banks lending rate on economic growth: an empirical evidence from Ghana doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-696863/v1

- CASTILLO, J. A., MORA-VALENCIA, A., & Perote, J. (2018). Moral hazard and default risk of SMEs with collateralized loans. Finance Research Letters, 26, 95–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2017.12.010

- CHEUNG, K.-Y., & Lin, P. (2004). Spillover effects of FDI on innovation in China: evidence from the provincial data. China Economic Review, 15(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1043-951X(03)00027-0

- CHU, A. C., Cozzi, G., Furukawa, Y., & Liao, C.-H. (2017). Inflation and economic growth in a schumpeterian model with endogenous entry of heterogeneous firms. European Economic Review, 98, 392–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2017.07.006

- CLAUS, I. (2011). The effects of asymmetric information between borrowers and lenders in an open economy. Journal of International Money and Finance, 30(5), 796–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2011.05.009

- COHEN, S. N., Henckel, T., Menzies, G. D., MUHLE-KARBE, J., & Zizzo, D. J. (2019). Switching cost models as hypothesis tests. Economics Letters, 175, 32–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2018.11.014

- DELL’ARICCIA, G. (2001). Asymmetric information and the structure of the banking industry. European Economic Review, 45(10), 1957–1980. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(00)00085-4

- DICKEY, D. A., & FULLER, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74, 427–431.

- EDO, S., Osadolor, N. E., & Dading, I. F. (2020). Growing external debt and declining export: The concurrent impediments in economic growth of Sub-Saharan African countries. International Economics, 161, 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2019.11.013

- EGGOH, J. C., & KHAN, M. (2014). On the nonlinear relationship between inflation and economic growth. Research in Economics, 68(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2014.01.001

- EKANAYAKE, E., & CHATRNA, D. (2010). The effect of foreign aid on economic growth in developing countries. Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies, 3, 1.

- ERICSON, R., Barry, D., & Doyle, A. (2000). The moral hazards of neo-liberalism: Lessons from the private insurance industry. Economy and Society, 29(4), 532–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140050174778

- GAMBACORTA, L., & MISTRULLI, P. E. (2014). Bank heterogeneity and interest rate setting: What lessons have we learned since lehman Brothers? Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 46(4), 753–778. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12124

- GRANGER, C. W., Newbold, P., & ECONOM, J. (1974). Spurious regressions in econometrics. Baltagi, Badi H. A Companion of Theoretical Econometrics, 557–561.

- HASELMANN, R., & WACHTEL, P. (2010). Institutions and bank behavior: Legal environment, legal perception, and the composition of bank lending. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 42(5), 965–984. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4616.2010.00316.x

- ILLES, A., Lombardi, M. J., & Mizen, P. (2015). Why did bank lending rates diverge from policy rates after the financial crisis?

- KARAHAN, Ö., & ÇOLAK, O. (2020). Inflation and economic growth in Turkey: evidence from a nonlinear ARDL approach. In Economic and financial challenges for Balkan and eastern european countries. Springer.

- KHAN, S. A. R., YU, Z., Sharif, A., & Golpîra, H. (2020). Determinants of economic growth and environmental sustainability in South Asian association for regional cooperation: Evidence from panel ARDL. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(36), 45675–45687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10410-1

- KHAN, I., Zakari, A., DAGAR, V., & Singh, S. (2022). World energy trilemma and transformative energy developments as determinants of economic growth amid environmental sustainability. Energy Economics, 108, 105884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105884

- KYEREBOAH‐COLEMAN, A. (2012). Inflation targeting and inflation management in Ghana. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 4(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/17576381211206460

- LADIME, J., SARPONG-KUMANKOMA, E., & Osei, K. (2013). Determinants of bank lending behaviour in Ghana. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 4, 42–47.

- LEVIEUGE, G., & SAHUC, J.-G. (2021). Downward interest rate rigidity. European Economic Review, 137, 103787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103787

- MISHKIN, F. S. (1996). The channels of monetary transmission: Lessons for monetary policy. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge.

- MOYO, C., & Le Roux, P. (2018). Interest rate reforms and economic growth: The savings and investment channel

- MUHAMMAD, B., & KHAN, M. K. (2021). Foreign direct investment inflow, economic growth, energy consumption, globalization, and carbon dioxide emission around the world. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(39), 55643–55654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14857-8

- MÜLLER, P. (2021). Impacts of inward FDIs and ICT penetration on the industrialisation of Sub-Saharan African countries. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 56, 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2020.12.004

- MWINLAARU, P. Y., & OFORI, I. K. (2017). Real exchange rate and economic growth in Ghana.

- NAMPEWO, D. (2021). Why are lending rates sticky? Investigating the asymmetrical adjustment of bank lending rates in Uganda. Journal of African Business, 22(1), 126–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2019.1693221

- NASIR, N. M., ALI, N., & Khokhar, I. (2014). Economic growth, financial depth and lending rate nexus: a case of oil dependent economy. International Journal of Financial Research, 5(2), 59. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijfr.v5n2p59

- NEOG, Y., & YADAVA, A. K. (2020). Nexus among CO2 emissions, remittances, and financial development: A NARDL approach for India. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(35), 44470–44481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10198-0

- NESS, V. A. N., WARR, R. S., A, R., F, B., NESS, V. A. N., WARR, R. S., & A, R. (2001). How well do adverse selection components measure adverse selection? Financial Management, 30(3), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/3666377

- NIELSON, C. C. (1996). An empirical examination of switching cost investments in business‐to‐business marketing relationships. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 11(6), 38–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858629610151299

- NKEMGHA, G. Z., Ofeh, M. A., & Poumie, B. (2022). Growth effect of Inflation in central African Countries: does security situation matter? Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1–22.

- NKETSIAH, I., & QUAIDOO, M. (2017). The effect of foreign direct investment on economic growth in Ghana. Journal of Business and Economic Development, 2, 227–232.

- NWAOGU, U. G., & RYAN, M. J. (2015). FDI, foreign aid, remittance and economic growth in developing countries. Review of Development Economics, 19(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12130

- OBAMUYI, T. M., Edun, A. T., & Kayode, O. F. (2012). Bank lending, economic growth and the performance of the manufacturing sector in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 8, 19–36.

- OLUSANYA, S. O., Oyebo, A., & Ohadebere, E. (2012). Determinants of lending behaviour of commercial banks: evidence from Nigeria, a co-integration analysis (1975-2010). Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 5, 71–80.

- ONYEIWU, C. (2012). Monetary policy and economic growth of Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 3, 62–70.

- PARADISO, A., Casadio, P., & Rao, B. B. (2012). US inflation and consumption: A long-term perspective with a level shift. Economic Modelling, 29(5), 1837–1849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.05.037

- PAULY, M. V. (1978). Overinsurance and public provision of insurance: The roles of moral hazard and adverse selection. In Uncertainty in Economics. Elsevier.

- PEERSMAN, G. (2002). Monetary policy and long term interest rates in Germany. Economics Letters, 77(2), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(02)00135-0

- PERERA, W. (2018). An analysis of the behaviour of prime lending rates in Sri Lanka. Asian Journal of Economics and Empirical Research, 5(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.501.2018.52.121.138

- PERRON, P. (1989). The great crash, the oil price shock, and the unit root hypothesis. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 57(6), 1361–1401. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913712

- PESARAN, M. H., SHIN, Y., & SMITH, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- PHILLIPS, P. C., & PERRON, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/75.2.335

- RAPETTI, M., Skott, P., & Razmi, A. (2012). The real exchange rate and economic growth: Are developing countries different? International Review of Applied Economics, 26(6), 735–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2012.686483

- REHMAN, A., MA, H., Ozturk, I., Murshed, M., & DAGAR, V. (2021). The dynamic impacts of CO2 emissions from different sources on Pakistan’s economic progress: A roadmap to sustainable development. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(12), 17857–17880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01418-9

- ROMER, P. M. (1994). The origins of endogenous growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.8.1.3

- S, W. I. N. (2018). Banks’ lending behaviour under repressed financial regulatory environment. the Context of Myanmar. Pacific Accounting Review.

- SALAMI, F. (2018). Effect of interest rate on economic growth: Swaziland as a case study. Journal of Business & Financial Affairs, 7, 1–5.

- SALISU, A. A., & ISAH, K. O. (2017). Revisiting the oil price and stock market nexus: A nonlinear panel ARDL approach. Economic Modelling, 66, 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.07.010

- SARATH, D., & Pham, D. V. (2015). The determinants of vietnamese banks’ lending behavior: A theoretical model and empirical evidence. Journal of Economic Studies, 42(5), 861–877. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-08-2014-0140

- SAYMEH, A. A. F., & ORABI, M. M. A. (2013). The effect of interest rate, inflation rate, GDP, on real economic growth rate in Jordan. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 3, 341.

- SENA, P. M., Asante, G. N., BRAFU-INSAIDOO, W. G., & Read, R. (2021). Monetary policy and economic growth in Ghana: does financial development matter? Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1966918. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1966918

- SEQUEIRA, T. N. (2021). Inflation, economic growth and education expenditure. Economic Modelling, 99, 105475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2021.02.016

- SHAUKAT, B., Zhu, Q., & KHAN, M. I. (2019). Real interest rate and economic growth: A statistical exploration for transitory economies. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 534, 122193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2019.122193

- SHIN, Y., YU, B., & GREENWOOD-NIMMO, M. (2014). Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In Festschrift in honor of Peter Schmidt. Springer.

- Stiglitz, J., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfection. The Emerican Economic Review, 71(3), 393–410.

- TANG, C., Irfan, M., Razzaq, A., & DAGAR, V. (2022). Natural resources and financial development: role of business regulations in testing the resource-curse hypothesis in ASEAN countries. Resources Policy, 76, 102612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102612

- TODARO, M., & SMITH, S. (2012). Economic Development. Addison Wesley. Pearson.

- UFOEZE, L. O., Odimgbe, S., Ezeabalisi, V., & Alajekwu, U. B. (2018). Effect of monetary policy on economic growth in Nigeria: an empirical investigation. Annals of Spiru Haret University, Economic Series, 9(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.26458/1815

- ULLAH, I., Shah, M., & KHAN, F. U. (2014). Domestic investment, foreign direct investment, and economic growth nexus: A case of Pakistan. Economics Research International, 2014, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/592719

- Van Dinh, D. (2020). Comparison of the impact of lending and inflation rates on economic growth in Vietnam and China. Banks and Bank Systems, 15(4), 193. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.15(4).2020.16

- WANG, Y., YU, H., Zhang, H., & Chen, T. (2021). Non-linear analysis of effects of energy consumption on economic growth in China: role of real exchange rate. Economic Modelling, 104, 105623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2021.105623

- WILSON, C. (1989). Adverse selection. In Allocation, information and markets. Springer.

- ZHAO, T., Matthews, K., & Murinde, V. (2013). Cross-selling, switching costs and imperfect competition in British banks. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(12), 5452–5462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.03.008

- ZIVOT, E., & ANDREWS, D. W. K. (2002). Further evidence on the great crash, the oil-price shock, and the unit-root hypothesis. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 20(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1198/073500102753410372

- ZULKHIBRI, M., & RANI, M. S. A. (2016). Term spread, inflation and economic growth in emerging markets: Evidence from Malaysia. Review of Accounting and Finance, 15(3), 372–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAF-04-2015-0056