Abstract

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) was colonised for about a century by the British, French and other European countries. Therefore, we examine these forms of colonisation on accounting development in Africa. We use a description-explanatory approach to show how three forms of colonisation have driven the development of accounting in Africa during and post-colonisation era. This paper defines driving forces during the colonisation period as ex-ante driving forces, and after independence, as ex-post driving forces. We identify among the ex-ante driving forces, governance, economic policy, education and language influenced accounting systems/practices, and they are still predominant. Regarding the ex-post, we found four ex-post driving forces that impact accounting in SSA, which supports the instrumental form of accounting colonisation. These four driving forces are foreign aid, foreign trade liberalisation, membership in international associations and prevalence of foreign ownership. This paper provides insights into how accounting practices have evolved in Africa and how colonisation has driven different accounting systems across the continent. Unlike prior studies, which are limited to pre or post-colonial eras, we provide an understanding of accounting development during the colonial and post-colonial era. Therefore, we demonstrate how colonisation still influences accounting development even after independence in many African countries.

1. Introduction

Since its discovery, Africa has been under the significant influence of European countries through direct colonisation (Falola, Citation2004) and neo-colonisation (Rao, Citation2000). However, Annisette (Citation2006) suggests that research on accounting history in Africa, in general, is very limited, except for the works of Ezzamel (Citation2002) on Egypt; Carnegie and Potter (Citation2000) on Anglo-Saxon accounting history in ex-colonies. Briston (Citation1978) argues that colonial inheritance is a major explanatory variable for the general financial reporting system in many countries outside Europe. Nobes (Citation1998) argues that former colonies are very likely to use their ex-colonisers’ accounting system, although this system is inappropriate for their current needs (see also, Hove, Citation1986). In effect, different colonisers used different key strategic driving forces (hereunder driving forces) to implant their accounting systems during the colonial epoch.

After independence, former colonies were still connected to their colonising powers and are now constrained by similar forces prevailing during colonisation. These forces are in the form of pressures from donor bodies, international associations, and institutions. The support from World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Trade Organisation (WTO) (known as the unholy trinity by Peet, Citation2009) on trade and finance has enabled formal colonial masters to maintain political influence in developing countries (Rao, Citation2000). For example, Judge et al. (Citation2010) contend that the World Bank and the IMF influence developing countries (ex-colonies) to adopt international accounting standards. However, many colonies such as South Africa, Nigeria, and Ghana claim to have developed new driving forces for accounting in the form of new regulatory frameworks and review of the accounting education system after they were decolonised but scrutinising these frameworks confirms that many have mainly emulated what their ex-colonisers are doing. Similarly, some countries, including Sudan, Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Algeria (mainly Islamic jurisdictions), are reverting to their practice beliefs of Islamic accounting, thus weaning away the colonisers’ accounting systems.

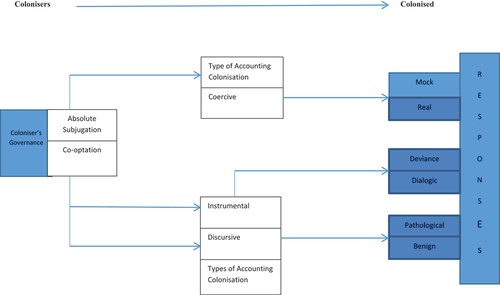

This paper defines driving forces during the colonisation period as ex-ante driving forces and after independence as ex-post driving forces. It then identifies the driving forces and conducts an ex-ante and an ex-post investigation to determine their impact on accounting. We develop a theoretical framework for this study considering (i) the governance systems (co-optation and absolute subjugation), (ii) three forms of accounting colonisation (coercive, instrumental and discursive), and (iii) the expected responses of the colonised to the colonisers’ driving forces. We use a description-explanatory approach to document the laws affecting accounting and construe the different types of accounting colonisation (Briston, Citation1978).

We extend and update the literature on the history of accounting in Africa (Boolaky & Jallow, Citation2008; Boolaky et al., Citation2018) by providing insights into how colonisation has shaped accounting practices in the continent. Unlike prior studies, which are limited to pre or colonial eras, we provide an understanding of accounting development during the colonial and post-colonial eras. Therefore, we demonstrate how colonisation still influences accounting development in Africa even after independence.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2.0 presents the research methods. Section 3 traces accounting practices in Africa before colonisation. Section 4.0 is on modes of accounting colonisation. Section 5.0 discusses the ex-ante driving forces. Section 6.0. presents the ex-post driving and the paper concludes in section 7.0.

2. Research methods

Consistent with prior studies (Briston, Citation1978; Saunders et al., Citation2019), we adopt a descriptive-explanatory approach. This research approach involves a description of phenomena and an explanation of why the phenomena work in a particular way (Saunders et al., Citation2019). Given the lack of data on some issues, we use different sources to generate sufficient appropriate evidence for our findings in this study. We, therefore, proceeded as follows. First, we used archival data by accessing archives of a few African countries (in Mauritius, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Ghana) and other secondary data published by the World Bank, International Financial Statistics, IFAC and WTO, and Reports from the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), ICAEW, CIMA, World Economic Forum, Deloitte IAS Plus (see, Boolaky, Citation2004; Briston, Citation1978).To determine the domestic accounting standards used in countries, we sighted a random sample of firms’ balance sheets and income statements during the period. We accessed these documents through the registrar of the company’s office.

3. Tracing accounting practices in Africa before colonisation

Annisette (Citation2006) argues that many pre-colonial African societies had features of modern economic activities such as taxation, accounting, money, tariff system, and even cosmopolitan commercial centres before colonialisation. For example, the Land of Gold (Ghana), Timbuktu (Mali), and Songhai (Niger and Burkina Faso) were doing commerce (Diop, Citation1987; Okafor, Citation1997). Diop (Citation1987) further argues that Timbuktu (Mali) was well-known in Asia and Europe for its important centres for international trade and commerce, whereas the Land of Gold (Ghana) had in place good administrative and tax systems. Timbuktu commonly used the practice that any debt should be in writing, like debt covenant nowadays.

The Axumite Kingdom, one of the most prominent trading hubs in the pre-colonial era, also practices some form of accounting system. Indeed, the kingdom is noted for being the first to mint coins as currency in Africa (Pankhrust, Citation1965, p. 2002). Largely trade between this the Axumite Kingdom and the Mediterranean countries was done in coins, and these transactions required book-keeping (Rena, Citation2005). The use of Axum coins and its related documentation is believed to be the beginning of banking and accounting systems in East Africa (Rena, Citation2007)

Extant literature in anthropology also provides evidence of financial systems and practices in ancient Africa (Bascon, Citation1952; Nwabughugu, Citation1984). These authors refer to a practice called “esusu” which originated in Africa. Esusu is a financial system whereby a number of people pool a fixed amount of money to a common fund for an agreed period (Bascon, Citation1952). For instance, each member who joins the fund contributes $10 monthly for a year. Then every month, each member, in turn, receives $120 (if there are 12 members) as agreed until the 12th month, where each member will receive the amount contributed, and the cycle is complete. In this system, an Esusu Leader will organise and manage the fund (that is, keep a record of members, their contributions, and all the pay-outs). While there were no clear-cut accounting principles, it is logical to believe that the leader keeps proper accounts and reports to members periodically. This indicates the presence of accounting during that era. This practice is equivalent to modern mutual finance commonly practised under different names in many other parts of the globe, such as Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, Mozambique, the Caribbean, and Ghana.

The above examples indicate that most African societies and kingdoms had well-functioning accounting systems that could have been developed further to suit the continent. However, when the colonisers penetrated Africa, they imposed their own systems and practices on the Africans using different forces and suppressed them from their own systems and practices where community trust and faith were prevalent. The colonisers made it appear that the existing systems were inferior and hence abolished them. For instance, on arrival in Eretria, the Italians replaced the existing coins with their own currency called the lire (Rena, Citation2007). Given the long years the colonisers spent in Africa, most societies forgot about their system in the pre-colonial era. Hence they adapt to what the colonisers left behind. The colonial mentality and the lack of expertise have hindered the development of the pre-colonial accounting system even after independence. Another reason why some of the well-function African origin systems could not develop further is globalisation. As the countries open up and embrace the culture of a global village, accounting systems across nations turn to mimic each other for easy cross border trade and investment. In effect, accounting has become both an instrument and an object in globalisation (Hopper et al., Citation2017). Prior studies also suggest that it is cheaper and more beneficial to adopt existing superior systems such as IFRS from the Western countries than to develop own system (Tawiah, Citation2019; Tawiah & Boolaky, Citation2019)

4. Mode of accounting colonization

Alam et al. (Citation2004) argue that it is difficult to theorise and generalise colonialism because the models, strategies, and practices of colonialism have differed from time to time and place. However, Said (Citation1993) defines colonialism as the implantation of settlements on a distant territory. Broadbent and Laughlin (Citation1997) posit that accounting colonisation occurs when changes to accounting are a force through changes in values and culture. Extending on Broadbent and Laughlin’s (Citation1997) definition of accounting colonisation, Oakes and Berry (Citation2009) contend that it can take place in three modes; (i) coercive, (ii) instrumental and (iii) discursive colonisation. .0 present mode of accounting colonization and the potential responses from ex-clonisers

Coercive colonisation occurs where controllers (colonisers) realise their intentions or objectives through enforced practices. This may entail two behavioural responses: mock obedience or real obedience. Mock obedience implies that ideologies of the colonised may remain unaltered, and the intentions of the colonisers are enacted by the colonised. Real obedience is that the ideologies of the colonised may change due to the inexorable imposition of coercive practices. In the context of this study, there are ex-colonies that have enacted the colonisers’ intentions, but their original ideologies have not changed. This is true in the Arabic World and other Islamic jurisdictions (Sudan, Egypt, Tunisia, and Algeria) that have reverted to the Islamic Accounting and Finance systems and practices.Footnote1 However, some are still following the accounting proposed by their ex-colonisers but under different names such as OCAM,Footnote2 OHADA, and UDEAC.Footnote3 For example, the OCAM Accounting Plan and UDEAC Accounting Plan are mainly simplified versions of the French Accounting Plan 1947. This argument is echoed by the narrative study conducted by Elad and Tumnde (Citation2009) on the accounting system of the OHADA countries in Africa. They contend that there are similarities between the book-keeping provisions of the Salary Code 1673, Code of Commerce 1807 and the OHADA Uniform Act on Accounting 2000. Elad’s (Citation2015) follow up studies also revealed that despite the persistent pressure of the World Bank and IMF for large entities to adopt IFRS, some Africa Franc Zone countries’ financial accounting practices are still modelled on the long-established French traditions. Colonisers have imposed their own systems and practices. For example, French colonisers used the Napoleonic Commercial Code 1807 (also called Commercial Code or Code of Commerce in some colonies) to enforce their rule-based Accounting Plan. This was common across all the ex-French colonies in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and other ex-French colonies in the rest of the world. Some colonies have adopted the colonisers’ intention due to fear of sanctions, especially where governance was of an absolute-subjugation type. Nowadays, the scenario has changed. Some developing countries, including ex-colonies, adopt accounting systems and practices due to fear of sanctions from international funding agencies or authoritative bodies. A typical example in Africa is that countries in OHADA must comply with the Uniform Act on Accounting, and failure could lure to sanctions for non-compliance from UMEC (Elad, Citation2015). Some other countries adopt IFRS due to pressure from the World Bank (Judge et al., Citation2010) or their affiliation with the International Federation of Accountants IFAC or World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Instrumental colonisation occurs when the colonisers realise their intentions or objectives using incentives, persuasion, bribery, and propaganda. This type of colonisation may entice two types of obedience/compliance, viz: devious compliance or dialogic compliance. Devious compliance means that changes to ideologies of the colonised are unlikely, despite support being expressed and instructions enacted. Dialogic compliance means that the colonised accept many changes to ideologies, and instructions are enacted and realised by bribery and incentives. In this perspective, Bakre (Citation2009) contends that colonisers, mainly British, offered education as an incentive to the sons of Chiefs because colonisers considered them to have the power to maintain the colonial systems and practices, including accounting. Arguably instrumental colonisation was practised through other incentives such as conditions for promotion at work. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many civil servants were promoted to top-level because of propagating and supporting colonisers’ intentions and instructions. The instrumental cololnialisation is common among the British ex-colonies, particularly those in West Africa.

Discursive colonisation occurs where the colonisers realise their intentions through processes of social discourse, and with this approach, colonisation is accepted by most colonised. Like the two fore-mentioned types of colonisation, discursive colonisation also leads to two types of behavioural responses, viz: discursively pathological and discursively benign. Discursively pathological means the degree of social discourse may contain hidden agenda, and therefore the risk of undesirable forms of ideological power may be implicated. Discursively benign arises from extensions to democratic processes. With discursively benign, the colonial masters start with the negative impact of the policy but stress more on the positive side

5. Ex-ante driving forces on accounting

Colonisation in SSA began in 1881 and lasted until 1981, though a few colonies obtained independence in the 1960s. Table (column 5) details how each of the forty-five SSA countries obtained independence. Colonisers were British, French and other Europeans. The strategies of the French influenced the other European colonisers. They used the law(s) and similar economic policies to influence the colonies (Meredith, Citation2005). For example, Spain, Portugal, and Belgium used the French Code of Commerce 1807 as accounting law and closed trade policies and punitive taxes on businesses in their colonies.

Table 1. List of SSA countries/colonisation/accounting standards/independence

The colonisers adopted a “divide and rule principle in all the colonies” (Posner et al., Citation2010). But this entailed conflict across race, gender, and a class of the total population. Arguably, with a similar conflict, only those with the strongest power were able to influence systems and practices. The colonisers, having dominant power, imposed their finance and accounting systems and practices over the colonised own systems and practices (Berry & Holzer, Citation1993; Boolaky & Jallow, Citation2008; Hove, Citation1986). They turned down the degree of trust prevalent among the Africans during these times.

5.1. Accounting law(s) and standards

British colonies were following the British Companies ActFootnote4 1862 and 1948. They followed the provisions of the Act, which relates to accounts of companies (there was no evidence on accounting by sole trader and partnership). Section 123–163 of the Companies Act 1948 deals with accounts and audits. Companies were required to keep records of transactions such as stock and cash records, maintain effective controls, and prepare accounts according to the generally accepted accounting principles (Companies Act 1976) and have them audited as prescribed in this Act. Although the UK has revised its own Companies Act since then, the colonies did not necessarily follow the same path but decided to rely on the old Acts. The UK generally accepted accounting principles used during colonisation and even for long after independence.

Non-British colonies were following the Code of Commerce, similar to the Commercial Code of 1807. Section 8–17 deals with accounts and audits of businesses. Unlike the Companies Act(s), the Commercial Code applied to all businesses, including sole traders and partnerships. Appendix 1 (a) summarises the relevant section of the Companies Act 1948, and Appendix 1 (b) is a summary of the relevant section of the Code of Commerce 1807. Table lists the Code of Commerce of the ex-French colonies and their Accounting Plans in SSA, and Table is the Companies ActsFootnote5 and accounting systems of each ex-British colony. In the British colonies, the section in their Companies Acts on “Accounts and Audit” was comparable to sections 123–163 of the UK 1948 Act, and for the non-British colonies, the provisions in their Code of Commerce were similar to Articles 8–17 in 1807 Commercial Code. To assist in compliance with the accounting requirements of the 1807 Code, the French designed the Accounting Plan in 1947, whereas the British did not have any similar Accounting Plan to meet the accounting requirements prescribed in the 1948 Act but later came up with the statement of standard accounting practices (SSAPs), now financial reporting standards (FRSs).

Table 2. Accounting laws and accounting systems and practices in French colonies after independence until late 2000

Table 3. Accounting law(s) and accounting systems and practices in British colonies after Independence until 2000

The three key driving forces that the colonisers used were namely: (i) political governance, (ii) economic and (iii) social policies, which are further sub-divided into elements (as proposed by Klerman et al., Citation2008).Footnote6 Each of the key driving forces has at least one or more elements of force (Klerman et al., Citation2008). Political governance during colonisation was either (i) direct rule (Absolute subjugation) or (ii) indirect rule (co-optation). Economic policies comprised two elements: (i) trade policy and (ii) tax policy. Trade policy was either open or closed, whereas tax was either a punitive or incentive policy. Social policies included (i) education system, (ii) language and (iii) religions. The ex-ante driving forces are presented in a conceptual framework in Figure , and further explained in the forthcoming paragraph.

5.2. Colonial governance and accounting

Absolute subjugation is mainly military dictatorship or direct rule, that is, using a form of coercion in order to appropriate the economic resources of the colonies and then redistribute the least minimum to the population. Co-optation is an indirect rule of governance that is instrumental or discursive, whereby traditional authorities are retained as agents to manage the local government. The reason(s) was mainly to use local political institution(s) for economic development. British colonisers used a co-optation strategy, whereas French and other colonisers used absolute subjugation. For instance, in Uganda, Sejjaaka (Citation2005) suggests that British colonial administrators impose British firm law as guidelines for preparing financial reports due to the absence of legislation. However, Uganda continued to use the British laws after legislation of the company Act in 1964. Leonard (Citation1987) highlighted that many ex-colonies followed the colonisers’ pathway even after independence though operational quality has reduced. On the verge of the nineteenth century, many non-British colonies in SSA made a paradigm shift from absolute subjugation to co-optation because the cost of governing through Absolute subjugation was high.

5.3. Colonizers’ trade policies and accounting

Trade policies were either open or closed. Grier (Citation1999) states that British colonisers were the only colonisers that allowed an open trade policy. The British imperial power did not avert any of its colonies to restrict their trade to only Britain. On the contrary, French and other European colonisers were practising trade protectionism, thus narrowing the trading scope of their colonies to only their own countries. For example, French colonisers traded only with France (Duignan & Gann, Citation1975). France has maintained economic, military and cultural ties with its colonies. To Lassou and Hopper (Citation2016), “exclusivity” is the cornerstone of France’s African policy compared to Britain because ex-France colonies in Africa still take 50–60% of their imports from France. Further, through pré-carré or domaine réservé (i.e., French preserve), EU partners are limited in their incursion on Francophone African countries (Martin, Citation1995). Arguably the non-British colonisers used the closed trade policy mainly to facilitate accounting based on a chart of accounts (Accounting Plan) which is rigid and rule-based as opposed to the British system. It, therefore, follows that because of its open trade policy, most British former colonies are geared towards principle-based accounting and can easily integrate into the globalisation of accounting standards.

5.4. Colonizers’ tax policies and accounting

Another driving force used by colonisers to influence development was the taxation system, which affected accounting systems and practices (Bush & Maltby, Citation2004; Nobes, Citation1983, Citation1998; Nobes & Parker, Citation2008). The tax policies were either incentive or punitive. Using the direct rule principle, French colonisers imposed punitive taxes and forced labour for non-payment of tax (Crowder, Citation1968). The British colonisers imposed lower taxes on the population because they were cheaper to administer through indirect rule and encouraged industry and trade development in the colonies (Austin, Citation2008; Maddison, Citation1971). In either case, (i.e. British or other colonies), accounting was mainly for tax reporting, and there was no evidence of accrual accounting practice in that epoch. Bush and Maltby (Citation2004) point out that the British used taxation to achieve social objectives and not merely as an instrument of economic policy.

Due to the punitive nature of the French system, most businesses were not likely to fully disclose all income; hence the French had to impose a rule-based Chart of Accounts. This rule-based Chart of Accounts was intended to restrict manipulation and ensure full disclosure of financial information for tax purposes.

On the contrary, the income tax strategy of the British did not require a rule-based as the focus was on motivating people to pay taxes rather than force them. Therefore, the British accounting system was principle-based, allowing for flexibility in reporting.

5.5. Colonizers’ education system, religions, languages, and accounting

The education system during colonisation was dependent on colonial governance. British colonisers used co-optation by giving incentives for education to the colonised. However, the incentive for western education was very discriminative and limited only to the Chief families and solely to the male: a pure closure theory principle whereby the opportunity for education was restricted to only a group (Chua & Poullaos, Citation1998). The British believed that the males of the Chiefs’ families were better placed to value the British system and acted as an intermediary between the British and the local people (Foster, Citation1965). As a result, the British colonisers offered education opportunities as an incentive to the sons of Chief families.

Moreover, the British colonial education system has multiple objectives, i.e. formal language, history, geography, numeracy, and religion. They entrusted educational responsibility to missionaries, which could also propagate religions simultaneously. Through this pathway, the British influenced the cultural beliefs and practices and languages of the indigenous. This has made the ex-colonies adopt and follow their coloniser’s education model. Consequently, the accounting education model in all these colonies is the British Accounting Education Model (BAEM; Bakre, Citation2009; Nobes & Parker, Citation2008), both in form and substance. For instance, Wijewardena and Yapa (Citation1998) content that Singapore and Sri Lanka, former British colonies, inherited their accounting education and practice from the British system. The Institute of Chartered Accountants (ICA) in many colonies were set up after independence based on the coloniser’s model. The ICA of South Africa, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, and Ghana, to mention a few, are modelled on the ICA in England and Wales. Even now, any update of their syllabi is inspired by the British model. Another evidence for the BAEM is the influence of UK-ACCA filtration in English-speaking countries around the globe. Interestingly, ACCA has also penetrated Rwanda, Mozambique, and a few other non-British colonies.

The French used a stricter education system where admission to the “Grandes Ecoles” was very limited and competitive. Like the British colonies, the French colonies have also adopted the French Education Model in general and the accounting profession. To qualify as an “Expert Comptables” (i.e. Chartered Accountant) in many of the ex-French colonies, one needs to have completed an undergraduate and pass the examinations of the “Ordres des Experts Comptables” (the equivalent of the Institute of Chartered Accountants). It is important to note that contrary to ex-British colonies, the number of qualified accountants in the French colonies was less in number (Boolaky, Citation2004). This could be due to the lower human development index in the ex-French colonies instead of the ex-British colonies.

Victor (Citation1992) argues that because the English language has been predominant in the world of business for a very long time, the British accounting system has been entrenched in many countries. French textbooks were used to entrench the French Accounting Plan in the French-speaking colonies (Madagascar, Congo, Rwanda, Cameroon, Mali). However, in non-French speaking as well as non-English speaking colonies such as Mozambique, the Portuguese language has been used, and the Portuguese Accounting Plan followed (Boolaky, Citation2004). Despite the ex-colonies trying to infiltrate their local language at schools and accounting textbooks being written in their language, yet they have not significantly contributed to changing the entrenched colonial position (Oberholster, Citation1999).

6. Ex-post driving forces on accounting

Pistor et al. (Citation2003) provide an elaborative explanation as to how laws implanted by the colonisers continued to exist and with emphasis on Company Law from the UK (1862 and 1948) and Commercial Code (1807) from France. All the ex-colonies have continued to use the colonisers’ law of accounting even after independence. British colonies used British law, and French Colonies used French law. Hinton (Citation1968) states that reporting requirements in South Africa, a former British colony, were principally based on the United Kingdom (UK) Companies Act, 1926 until 1968 and then after, based on the recommendations of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales. This view is supported by Mueller (Citation1967), Da Costa et al. (Citation1978), and Briston (Citation1990), who suggest that many countries, including South Africa, were included under the British sphere of influence. Briston (Citation1990) contends that many ex-British colonies found themselves after independence with a British Accounting model. In like manner, Chaderton and Taylor (Citation1993) argue that colonisation is a key driver for transferring accounting systems to developing countries. Wallace (Citation1993) concurs with the above views by stating that accounting systems and practices during the imperial powers have moved on to the independent ex-colonies. For instance, in Madagascar, the accounting system before and after independence was French-based until they began to converge the Madagascar Accounting Plan with the IFRS in 2005 (Boolaky & Jallow, Citation2008). Similarly, in Central and North Africa, the colonies continued with the colonial inheritance until 1998, when the OHADA law on accounting was enacted and followed by the SYSCOA in 2000. On the other hand, ex-European colonies in Africa have continued with colonial laws and accounting systems. In the European colonies, Rwanda followed the Rwanda Accounting Plan until 2007, when the country decided to move for IFRS following the World Bank recommendations in certain sectors such as banking and insurance. Mozambique is also following a similar pathway by moving away from the Portuguese Accounting Plan to IFRS following the recommendation from the World Bank.

Table documents the accounting law(s) (including Sections or Articles) and accounting systems and practices used by several French colonies in Africa after independence. Table explains that ex-French colonies have not departed from the colonial system even after independence. The accounting law(s) has been based on the French Commercial Code in all these countries, as well as their accounting systems and practices based on Accounting Plan

Table presents the accounting law(s), accounting systems and practices and basis of the GAAP in the ex-British colonies in Africa after independence. It is interesting to note that the Companies Acts in these countries were basically a copy of the 1948 Act of the UK. The ‘Accounts and Audit section has the exact requirements as prescribed in UK law. Except for Nigeria, which was among the first to enact a Companies Act in 1912 and based on the UK 1862 Companies Act.

In order to determine the accounting practices used after independence, a few financial reports from 1980- to 1995 were reviewed to determine the accounting standards used in some of these countries. Evidence, therefore, suggests that in Mauritius, Zimbabwe, Ghana, and South Africa, the standard practices were based on the UK SSAPs before they decided to converge with IFRS. Our observation of some audit reports suggests that they only mention that accounts have been prepared according to the Act and Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and are true and fair. We counter-verified in the Companies Act(s) of these countries to determine the GAAP they refer to, but the Act(s) did not specify which GAAP. We further investigate by discussing with one accountant (academic or practising accountant) in one Ex-British colony (Ghana), an Ex-Portuguese colony (Mozambique), and an Ex-French colony (Madagascar) and an Ex-British/French colony (Mauritius). Our findings suggest that the ex-British colonies were using the UK SSAPs, the ex-French colonies used the French Accounting Plan, ex-Portuguese colony the Portuguese Accounting Plan. Although being British and French-influenced, Mauritius used the UK GAAP (SSAPS).

The independent colonies continued to use the accounting systems implanted by their colonisers for more than three decades after independence. By the end of the twentieth century, many decided to either adapt or adopt international standards (including accounting and auditing) because of internal and global pressures in different forms (Bakre, Citation2006; Boolaky, Citation2004; Nobes, Citation1998). These pressures are regarded as ex-post driving forces on accounting systems and practices in SSA. Some examples of these pressures are (1) directives from donor institutions (World Bank) or donor countries, (2) requirements for membership to the World Trade Organisation, (3) promotion of IFRSs and ISAs by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), (4) foreign trade liberalisation (both exports and imports), (5) providing opportunities to foreign investors by offering the possibility to own share in local companies. A review of these ex-post driving forces suggests that some are still a form of modern colonisation and much more in the form of co-optation than absolute subjugation. For example, WTO and IFAC are classical examples of strategic disguised colonial vehicles to continue influencing the ex-colonies. Lassou and Hopper (Citation2016) contend that the unholy trinity (WB, IMF, and the WTO), in addition to western professional bodies, the Big4, the standard-setting bodies, are the nexus of interlocking international agencies influencing the diffusing of essentially Anglo-Saxon model of accounting in developing countries. This takes the form of the ancient colonisers’ tactic of co-optation, giving incentive(s) to countries to either obtain foreign aid or prestige by belonging to these international bodies. Bakre (Citation2014) and Annisette (Citation2000) also identify a similar trend in Commonwealth Caribbean, and Trinidad and Tobago, respectively. In other words, when one country has joined IFAC, for instance, many others followed suit for similar reasons despite the fact that they are not well-represented on the executive platform of these organisations. This is a form of instrumental colonisation, proposed by Oakes and Berry (Citation2009), is where modern colonisers attempt to realise their intentions or objectives by using incentives and propaganda. Rahaman (Citation2010) also argues that, through the control of the World Bank and IMF, which provide de facto financial governance to Sub-Saharan Africa, western countries still control their colonies. In earlier studies, Rahaman et al. (Citation2010) provided evidence of contemporary accounting imperialism through the World Bank’s neo-liberal agenda in the underdeveloped world. Similarly, Bakre (Citation2006) opines that capitalism and colonialism still have significant influence insofar as the institutions of the former colonising power would wish to exploit former colonies through the redefinition of its relations after independence. However, driving forces in the form of foreign trade liberalisation and opportunity for foreign investors are not all related to the ex-colonisers’ direct or indirect influence but are principally an economic decision of the independent colonies.

7. Conclusion

This paper identifies the colonisers’ driving forces on accounting during colonisation (ex-ante driving forces) and describes the theoretical links between colonisers’ governance. Further, we have documented the three forms of accounting colonisation and the expected behavioural responses of the colonised as proposed by Oakes and Berry (Citation2009). We also presented a conceptual framework to show the link between colonisers and their driving forces on accounting.

With regard to the post-colonial period, we identified four driving forces in accounting in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). While the colonisers’ education played a vital role during colonisation, after independence, the ex-colonies were not coerced to adopt only the colonisers’ education system but have opened to other systems. This is especially true for ex-French colonies. For example, the OHADA member countries were not forced to follow only French Accounting Training. OHADA countries have opened up themselves to implement IFRS by engaging in numerous technical training on IFRS. After numerous training and preparation, the OHADA countries adopted IFRS effective 2019.

A similar trend can be identified in Mozambique, Rwanda, and Madagascar. Prevalence of foreign ownership and foreign trade liberalisation are as well significant ex-post driving forces of the accounting in these countries. This paper confirms the theory that the number of trading partners has increased by adopting an open trade policy after independence. Similarly, the entry of foreign investors in these countries has also increased, thus pushing for better accounting. For instance, the US and European investors who have set up businesses in Mozambique, Rwanda or Madagascar would require a more sophisticated accounting that reflects international best practices. Findings on the ex-post factors suggest that there is no direct imposition as there was during colonisation, whereby colonised were forced to accept what they were asked to.

Our study has some limitations. Access to data is not easy, and most of the data were hand collected from various sources and data which the author personally collected while working in Africa.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI standards.

2. Organisation Communes d’Afrique et Madagascar.

3. Union Douanieres Economique d’Afrique Centrale.

4. In England, corporate law bean to be codified in 1844, but the first comprehensive act was that of 1862. This was the initial Companies Act that the colonisers brought in Africa and other British Colonies.

5. The Companies Acts of each country is searched from the World Fact Book.

6. Klerman et al. (Citation2008) call them influencing channel and grouped into key and sub channels.

References

- Alam, M., Lawrence, S., & Nandan, R. (2004). Accounting for economic development in the context of post-colonialism: The Fijian experience. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(1), 135–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1045-2354(03)00006-6

- Annisette, M. (2000). Imperialism and the professions: The education and certification of accountants in Trinidad and Tobago accounting. Organisations and Society, 25(7), 631–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(99)00061-6

- Annisette, M. (2006). People and periods untouched by accounting: An ancient Yoruba practice. Accounting History, 11(4), 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373206068704

- Austin, G. (2008). The reversal of fortune, thesis and the compression of history: Perspective from African and comparative economic history. Journal of International Development, 20(8), 996–1027. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1510

- Bakre, O. M. (2006). Second attempt at localising imperial accountancy: The case of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Jamaica (ICAJ) 1970s-1980s). Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 17(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2004.02.006

- Bakre, O. M. (2009). The inappropriateness of Western economic power frameworks of accounting in conducting accounting research in emerging economies: A review of the evidence. Accountancy Business and the Public Interest, 8(2), 65–95.

- Bakre, O. M. (2014). Imperialism and the integration of accountancy in the Commonwealth Caribbean. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25(7), 558–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2013.08.008

- Bascon, W. (1952). The Esusu: A credit institution of the Yoruba. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 82(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/2844040

- Berry, M., & Holzer, P. (1993). Restructuring the accounting function in the third world. Research in Third World Accounting, 2(1), 225–244.

- Boolaky, P. (2004). Accounting development in Africa: A study of the impact of colonisation and legal systems on accounting standards in Sub-Saharan African Countries. Delhi Business Review, 5(1), 123–135.

- Boolaky, P. K., & Jallow, K. (2008). A historical analysis of the accounting development in Madagascar between 1900 to 2005: The journey from accounting plan to IFRS. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 9(2), 126–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/09675420810900793

- Boolaky, P. K., Omoteso, K., Ibrahim, M. U., & Adelopo, I. (2018). The development of accounting practices and the adoption of IFRS in selected MENA countries. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 8(3), 327–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-07-2015-0052

- Briston, R. J. (1978). The evolution of accounting in developing countries. International Journal of Accounting, 14(1), 105–120.

- Briston, R. J. (1990). Accounting in developing countries-Indonesia and Solomon Islands A case studies for regional cooperation. Research in Third World Accounting, 1(2), 195–216.

- Broadbent, J., & Laughlin, R. (1997). Developing empirical research: An example informed by a Habermasian approach. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 10(5), 622–648. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513579710194027

- Bush, B., & Maltby, J. (2004). Taxation in West Africa: Transforming the colonial subject into the “governable person”. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1045-2354(03)00008-X

- Carnegie, G. D., & Potter, B. N. (2000). Publishing patterns in specialist accounting history journals in the English Language, 1996–1999. Accounting Historians Journal, 27(2), 177–198. https://doi.org/10.2308/0148-4184.27.2.177

- Chaderton, R., & Taylor, P. V. (1993). Accounting systems of Caribbean, their evolution and role in economic growth and development. Research in Third World Accounting, 12(1), 45–66.

- Chua, W., & Poullaos, C. (1998). Rethinking the profession-state dynamic: The Victorian chartered attempt. Accounting Organisation and Society, 18(7–8), 691–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)90049-C

- Crowder, M. (1968). West Africa under colonial rule. Benin City: Ethiope. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 5(1), 173–177.

- Da Costa, R. C., Bourgeois, J. C., & Lawson, W. M. (1978). A classification of international financial accounting practices. International Journal of Accounting, 13(2), 73–85.

- Diop, C. A. (1987). Black Africa: Economic and cultural basis for a federal state. Lawrence Hill & Co.

- Duignan, P., & Gann, L. H. (1975). Colonialism in Africa 1870–1960. Cambridge University Press.

- Elad, C., & Tumnde, M. (2009). Bookkeeping and the probative value of accounting records: Savary’s legacy lingers on in the OHADA treaty states. International Journal of Critical Accounting, 1(1), 82–109. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJCA.2009.025332

- Elad, C. (2015). The development of accounting in the Franc zone countries in Africa. International Journal of Accounting, 50(1), 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2014.12.006

- Ezzamel, M. (2002). Accounting and redistribution: The palace and mortuary cult in the Middle Kingdom, ancient Egypt. Accounting Historian Journal, 29(1), 59–101. https://doi.org/10.2308/0148-4184.29.1.61

- Falola, T. (2004). Africa: The end of colonial rule, nationalism and decolonisation. University Press.

- Foster, P. (1965). Education and social change in Ghana. LondonRoutledge & Kegan Paul).

- Grier, R. (1999). Colonial legacies and economic growth. Public Choice, 98(3/4), 318–336. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30024490?seq=1

- Hinton, G. (1968). The international harmonisation of auditing standards and procedures. South African Chartered Accountant, 4, 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2016.06.003

- Hopper, T., Lassou, P., & Soobaroyen, T. (2017). Globalisation, accounting and developing countries. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 43(March), 125–148.

- Hove, R. (1986). Accounting practice in developing countries: Colonialism’s legacy of inappropriate technologies. International Journal of Accounting Research, 22(1), 81–100.

- Judge, W., Li, S., & Pinsker, R. (2010). National adoption of international accounting standards: An international perspective, Corporate Governance. An International Review, 18(3), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2010.00798.x

- Klerman, D., Mahoney, H., & Weinsten, M. (2008). Legal origin and economic growth. Unpublished, available at http://www.law.ucla.edu/docs/klerman_paper.pdf.

- Lassou, P. J. C., & Hopper, T. (2016). Government accounting reform in an ex-French African colony: The political economy of neo-colonialism. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 36(April), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2015.10.006

- Leonard, D. K. (1987). The political realities of African management. World Development, 15(7), 899–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(87)90041-6

- Maddison, A. (1971). Class structure and economic growth. Geoger Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Martin, G. (1995). Continuity and change in Franco–African relations. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 33(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00020826

- Meredith, M. (2005). The State of Africa: A history of fifty years of independenc. Jonatahn Ball Publishers (PTY) Ltd.

- Mueller, G. (1967). International accounting. Macmillan.

- Nobes, C. (1983). A Judgmental international classification of financial reporting practices. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, Spring(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.1983.tb00409.x

- Nobes, C. (1998). Towards a General model of the reasons for international differences in financial reporting. Abacus, 34(2), 162–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6281.00028

- Nobes, C. H., & Parker, R. (2008). Comparative international accounting. Pearson Education.

- Nwabughugu, A. I. (1984). The isusu: an institution for capital formation among NGWA IGBO; Its origin and development to 1951. Africa, 54(4), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.2307/1160396

- Oakes, H., & Berry, A. (2009). Accounting colonisation: Three case studies in further education. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 20(3), 344–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2007.06.006

- Oberholster, J. (1999). Financial accounting and reporting in developing countries: A South African perspective. SAJEMS, 2(2), 222–238. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v2i2.2575

- Okafor, V. A. (1997). Toward an africological pedagogical approach to African civilisation. Journal of Black Studies, 27(3), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193479702700301

- Pankhrust, R. (1965). the history of currency and banking in Ethiopia and in the Horn of Africa from the middle ages to 1935. Ethiopia Observer, (4), 10–12.

- Peet, R. (2009). Unholy trinity: The IMF, world bank and WTO (2nd Revised ed.). Zed Books Ltd.

- Pistor, K., Yoram, K., Kleinheisterkamp, J., & West, M. D. (2003). The evolution of corporate law, a cross-country comparison. The University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law, 23(4), 791–871. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jil/vol23/iss4/4

- Posner, E. A., Spier, K. E., & Vermeule, A. (2010). Divide and conquer. Journal of Legal Analysis, 2(2), 417–471. https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/2.2.417

- Rahaman, A.S, Lawrence, S. & Roper, J. (2010). Social and environmental reporting at the VRA: Institutionalised legitimacy or legitimation crisis? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1045-2354(03)00005-4

- Rahaman, A. S. (2010). Critical accounting research in Africa: Whence and whither. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(5), 420–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2010.03.002

- Rao, N. (2000). Neo-colonialism or globalisation? post-colonial theory and the demands of political economy. Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, 1(2), 165–184. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41209050?seq=1

- Rena, R. (2005). A comprehensive history of Eritrea. Millennium Publishers.

- Rena, R. (2007, June). Historical development of money and banking in Eritrea from the Axumite Kingdom to the Present”, New York: USA. African and Asian Studies, 6(1–2), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1163/156921007X180613

- Said, E. (1993). Culture and imperialism. Vintage Books.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., Thornhill, A., & Bristow, A. (2019). Research methods for business students. Chapter 4: Understanding Research Philosophy and Approaches to Theory Development, 128–171.

- Sejjaaka, S. (2005). Compliance with IAS disclosure requirements by financial institutions in Uganda. Journal of African Business, 6(1–2), 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1300/J156v06n01_06

- Tawiah, V., & Boolaky, P. (2019). A review of literature on IFRS in Africa. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 16(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-09-2018-0090

- Tawiah, V. (2019). The state of IFRS in Africa. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 17(4), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-08-2018-0067

- Victor, D. (1992). International Business Communication. Happer Collins Publishers Inc.

- Wallace, R. (1993). Development of accounting standards for developing and newly industrialised countries. Research in Third World Accounting, 2, 121–165.

- Wijewardena, H., & Yapa, S. (1998). Colonialism and accounting education in developing countries: The experiences of Singapore and Sri Lanka. The International Journal of Accounting, 33(2), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7063(98)90030-9

Appendix 1

(A): Companies Act 1948 and Code of Commerce 1807

Companies Act 1948: Section 123-127

ACCOUNTS

123: The directors shall cause proper books of account to be kept with respect to: -

(a) all sums of money received and expended by the company and the matters in respect of which the receipt and expenditure takes place;

(b) all sales and purchases of goods by the company; and

(c) the assets and liabilities of the company. Proper books shall not be deemed to be kept if there are not kept such books of

account as are necessary to give a true and fair view of the state of the company’s affairs and to explain its transactions.

124: The books of account shall be kept at the registered office of the company, or, subject to section 147(3) of the Act, at such other place or places as the directors think fit, and shall always be open to the inspection of the directors.

125: The directors shall from time to time determine whether and to what extent and at what times and places and under what conditions or regulations the accounts and books of the company or any of them shall be open to the inspection of members not being directors, and no member (not being a director) shall have any right of inspecting any account or book or document of the company except as conferred by statute or authorised by the directors or by the company in general meeting.

126: The directors shall from time to time, in accordance with sections 148, 150 and 157 of the Act, cause to be prepared and to be laid before the company in general meeting such profit and loss accounts, balance sheets, group accounts (if any) and reports as are referred to in those sections.

127: A copy of every balance sheet (including every document required by law to be annexed thereto) which is to be laid before the company in general meeting, together with a copy of the auditors’ report, shall not less than twenty-one days before the date of the meeting be sent to every member of, and every holder of debentures of, the company and to every person registered under regulation 31. Provided that this regulation shall not require a copy of those documents to be sent to any person of whose address the company is not aware or to more than one of the joint holders of any shares or debentures.

CAPITALISATION OF PROFITS

128: The company in general meeting may upon the recommendation of the directors resolve that it is desirable to capitalise any part of the amount for the time being standing to the credit of any of the company’s reserve accounts or to the credit of the profit and loss account or otherwise available for distribution and accordingly that such sum be set free for distribution amongst the members who would have been entitled thereto if distributed by way of dividend and in the same proportions on condition that the same be not paid in cash but be applied either in or towards paying up any amounts for the time being unpaid on any shares held by such members respectively or paying up in full unissued shares or debentures of the company to be allotted and distributed credited as fully paid up to and amongst such members in the proportion aforesaid, or partly in the one way and partly in the other, and the directors shall give effect to such resolution:

Provided that a share premium account and a capital redemption reserve fund may, for the purposes of this regulation, only be applied in the paying up of unissued shares to be issued to members of the company as fully paid bonus shares.

129: Whenever such a resolution as aforesaid shall have been passed the directors shall make all appropriations and applications of the undivided profits resolved to be capitalised thereby, and all allotments and issues of fully-paid shares or debentures, if any, and generally shall do all acts and things required to give effect thereto, with full power to the directors to make such provision by the issue of fractional certificates or by payment in cash or otherwise as they think fit for the case of shares or debentures becoming distributable in fractions, and also to authorise any person to enter on behalf of all the members entitled thereto into an agreement with the company providing for the allotment to them respectively, credited as fully paid up, of any further shares or debentures to which they may be entitled upon such capitalisation, or (as the case may require) for the payment up by the company on their behalf, by the application thereto of their respective proportions of the profits resolved to be capitalised, of the amounts or any part of the amounts remaining unpaid on their existing shares, and any agreement made under such authority shall be effective and binding on all such members.

AUDIT

130: Auditors shall be appointed and their duties regulated in accordance with sections 159 to 162 of the Act