Abstract

This paper examines the value interplay and governance challenges among cooperatives, particularly operating in an extreme environment such as Indonesia’s BMTs (Islamic cooperatives). BMTs act as a “bridge” for small and medium enterprises to gain financial support unobtainable from more formal financial institutions. BMTs have experienced unprecedented growth in Indonesia. Recently, there has been an alarming increase in the instances and magnitude of fraud in BMTs. This paper is built on micro‐level evidence showing how value creation and disruption lead to fraud in cooperatives. The author focuses on a specific value interplay process to understand how fraud incidents disrupt internalised values and affect organisational governance. The findings indicate the challenges of the overlapping values in cooperatives in extreme organisational settings and the need for better alignment between micro and macro values to minimise fraud.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper investigates fraud issues in cooperatives, particularly those operating in a difficult environment such as Indonesia’s BMTs (Islamic cooperatives). BMTs are an important phenomenon in Indonesia due to their rapid growth across the nation. However, in contrast to what we would expect from organisations espousing Islamic values, in recent years there have been several frauds involving BMTs which both socially and economically have had a damaging effect on communities. This paradox merits an investigation. The author focuses on a specific stakeholder’s value interplay to understand how fraud incidents disrupt internalised values and affect organisational governance. The findings indicate that organisations such as cooperatives should pay attention to their stakeholder interests and roles to minimise fraud. The instances of fraud in BMTs are considered a systematic failure of Islamic cooperative governance in Indonesia. All stakeholder groups have a part to play in these failures as well as the prevention efforts.

1. Introduction

Organisations can be divided into types based on many classification systems; for instance, based on size (large, medium, and small organisations); ownership (public, private organisations); coverage areas (regional, national, international) and so on, including traditional and non-traditional organisations. Handy (Citation1995, p. 350) points to the traditional assumption that organisations are led through a hierarchical command derived mainly from classical and scientific management principles. Handy defines the basic structure of a traditional organisation as one with a linear, segmented, and hierarchical framework. Over time, this design, however, has been modified into a complex, multi-layered structure (Mabey et al., Citation2001; McMillan, Citation2002; Mullins, Citation1993), though there is some fear that such a structure would not last long, given the flexibility required to adapt in a rapidly changing world.

A new organisational paradigm emerged and influenced the definition of the non-traditional organisations (Rahajeng, Citation2018) used in this study. Delayering, downsizing, and de-structuring were part of the new business re-engineering (Coulson-Thomas & Coe, Citation1991; Mabey et al., Citation2001). Significant shifts were seen from the old/traditional factors that were thought to achieve success, including size, role clarity, specialisation, and control, to new success factors, including speed, flexibility, integration, and innovation (Ashkenas, Citation1995, p. 7). Structural integrity, functionality, sustainability, and aesthetic appeal were also adopted in a non-traditional organisational approach (McMillan, Citation2002; Pascale, Citation1999). This re-engineering, however, carried the risk that it could fail if not carefully prepared and supported by organisational resources (Mumford & Hendricks, Citation1996).

The findings of studies on traditional corporate governance (CG) are to some extent inapplicable to the non-traditional organisations operating in lower-income economies, mainly due to their different organisational characteristics (Liew, Citation2008; Mees & Smith, Citation2019; Okike, Citation2007; Rahajeng, Citation2018; Tsamenyi et al., Citation2007; Tsamenyi & Uddin, Citation2008; Uddin et al., Citation2008; Vaughn & Ryan, Citation2006). A large amount of research in CG is conducted on the issues of board performance, non-executive directors, ownership, and managerial board separation in traditional organisation settings, mainly in the context of higher-income countries (Brennan et al., Citation2008; Goergen & Tonks, Citation2019).

Aguilera and Jackson (Citation2010) argue that traditional CG mechanisms neglect other organisational variables such as the institutional, legal, and cultural environments in which non-traditional organisations are embedded. In practice, specific organisational characteristics, namely value-based organisationsFootnote1 and membership-based organisations, play an essential consideration in non-traditional CG frameworks (Aguilera & Jackson, Citation2010). This paper analyses how the specific value interplay process disrupts CG structures in non-traditional organisations in an extreme institutional environment.

Baitul Maal Wat Tamwil (henceforth BMTs) are Islamic cooperatives that are a combination of value-based and membership-based organisations with contractual obligations to their members and a need to follow Islamic values in their governance mechanisms. As Islamic cooperatives, BMTs need to avoid the elements of interest or usury (riba), speculation or gambling (maysir), forbidden things (haram), and excessive uncertainty (gharar; Al-Muharrami & Hardy, Citation2013; Government of Indonesia, Citation2008; Haniffa & Hudaib, Citation2002; Lewis, Citation2005; Riaz et al., Citation2017; Safieddine, Citation2009). Islamic values also require businesses to not cause harm to others (dzalim).

Contrasting with the values of BMTs, a series of fraud incidents have recently occurred among BMT cooperatives. This is the largest documented BMT-related fraud in Indonesia since 2006. For instance, the 11 biggest BMT frauds in Indonesia from 2011 to 2014 cost the Indonesian economy more than IDR 1,143.69 billion (USD 80.54 million) a year which was equal to 12.69% of the contribution of small and medium enterprises to the Indonesian gross domestic product or 0.007% from the Indonesian GDP is USD 1,058,423.84 million (World Bank, Citation2020). The fraud costs equated to more than IDR 36,000 or USD 2.5 lost per second every day; this was in a country where more than 28.5 million people, or 11.1% of the population, had an income below the poverty line at IDR 11,494 or USD 0.81 per day (Berita Satu, Citation2020). The master plan of Islamic financial architecture in Indonesia indicates a lack of corporate governance in BMTs (Bappenas, Citation2016), which potentially leads to fraud. The astonishing levels of fraud in the system warrant an analysis of governance practices in these institutions. To date, very little attention has been given to the CG practices of these institutions, irrespective of the unparalleled levels of fraud.

2. Theoretical perspectives

Each organisation develops a unique and complex culture derived from its characteristics and values shared with corresponding stakeholders. The non-traditional organisations are differentiated from the old, and the traditional factors thought to achieve success, including size, role clarity, specialisation, and control, are replaced by adapted success factors, including technology and innovation, at the heart of non-traditional organisations (Harter & Krone, Citation2001). Cooperatives and other social enterprises are usually small, have a non-centralised ownership structure, focus on social innovation, high adaptability, capacity to learn and change, and are considered to be more efficient due to their less bureaucratic structures (Allen, Citation2001; Defourny & Nyssens, Citation2008; McMillan, Citation2002). Therefore, different CG mechanisms are needed for non-traditional organisations such as cooperatives. Cornforth (Citation2001a, Citation2001b) states that theories of CG can be extended to help understand the governance of social enterprises, including cooperatives and mutual organisations. As Jegers (Citation2009) highlights, the word “corporate” in corporate governance is no longer restricted to corporations or for-profit organisations.

Societal and organisational characteristics affect CG structures in higher- and lower-income countries. However, non-traditional organisations in the microfinance industry, particularly in developing regions like Central Europe, Eastern Europe, the Newly Independent States, and other emerging economies, have more complicated CG frameworks due to their dynamic societal and organisational characteristics. Hartarska (Citation2005) and Campion (Citation1998) firmly assert that microfinance institutions are themselves quite diverse in terms of organisational types, including non-governmental organisations (NGOs), banks, credit unions, cooperatives, and nonbank financial institutions. Other managerial aspects, including organisational ownership, also affect CG mechanisms.

The researcher has adopted stakeholder theory (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984) as an analytical framework for four main reasons. First, using stakeholder theory in the context of BMTs is considered novel. Many areas in stakeholder theory remain insufficiently investigated, especially in the context of non-profit organisations, small enterprises, and family firms (Laplume et al., Citation2008). Moreover, as described previously, many studies focus on publicly traded companies rather than social enterprises. Second, stakeholder theory is useful in depicting the relationship of any group or individual who can affect, has been affected by, or may potentially be affected by the organisation (see, R.E. Freeman, Citation1984). As a form of cooperative, BMTs have stakeholders who are highly important to their development. As an enterprise or organisation, a cooperative is jointly owned or managed by those (i.e. stakeholders) who use its facilities or services (i.e. a “co-op”; Birchall, Citation2003; Simmons & Birchall, Citation2008). Their main stakeholders are not limited to members; other stakeholders are the beneficiaries, and community, who have interests, willingness, and the ability to cooperate and support a cooperative (i.e. BMT). Stakeholder theory embraces the notion that all stakeholders, including shareholders, are vital stakeholders of the company and, as such, their interests should be taken into account (Strand & Freeman, Citation2015).

Third, stakeholder theory (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984) also helps model and classify BMT stakeholders into two main groups: internal stakeholders (i.e. managers, employees, members) and external stakeholders (i.e. beneficiaries, authorities, community). The roots of stakeholder theory include value creation, the ethics of capitalism, and the managerial mindset (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984). The researcher has adopted these concepts, particularly the value creation framework, as they help in understanding the internalisation (value interplay) of BMT stakeholders. R. E. Freeman et al. (Citation2013) indicate that stakeholder theory discusses how organisations work at their best and effectively create as much value as possible for their stakeholders.

Fourth, many possible theories could have been adopted. However, this study emphasises the values interplay of stakeholders; it is not only underlining the conflicting and disrupting values that may occur (which could be analysed using agency relationship theory) but also defining the value creation within the organisations. It is beyond the surface analysis of agency problems. Therefore, using stakeholder theory (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984) can help to depict the accountability and responsibility processes of organisations to their stakeholders through the value interplay in the governance mechanism.

2.1. BMTs

In Indonesia, BMT cooperatives are financial institutions that provide alternatives for unbanked and underbanked individuals and small and medium enterprises (Doi, Citation2010). Most of the formal financial services (77.64%) are concentrated in five provinces: the Special Province of Jakarta (DKI Jakarta), East Java, West Java, Central Java and North Sumatra (Jasa Keuangan, Citation2019). Only 49% of households in Indonesia have access to formal financial institutions (Hadad, Citation2015). BMTs are regulated, supervised, and monitored by the Ministry of Cooperatives and Small and Micro Enterprises of the Republic of Indonesia (henceforth, just Ministry of Cooperatives). BMTs mainly accommodate the financial needs of small and medium enterprisesFootnote2 by offering them convenient financial products and services with less burdensome procedures. However, the mushrooming growth of BMTsFootnote3 has taken place in an environment of limited regulation, and they have only been loosely monitored by the authorities (Riwajanti, Citation2013).

As an Islamic cooperative, BMTs adopt Islamic values. The definition of Islamic law (sharia law) by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions represents a comprehensive value system for all aspects of life, in conformity with the environment. The paper adopts the terminology of Al-Ghazali’s (Citation1989) Islamic values based exclusively on the interpretations of the Qur’an and Sunna (Sidani & Al Ariss, Citation2015). It covers the concepts of khayr (goodness), birr (righteousness), qist (equity), ‘adl (equilibrium and justice), haqq (truth and right), ma’ruf (known and approved), and taqwa (piety; Beekun, Citation1997). However, it is important to note that sharia law does not replace the regulatory system of current Indonesian legal codes.

2.2. Extreme environment

BMTs operate under the conditions of fragile and extreme environments. First, they operate in an institutional void as the authorities only loosely monitor the BMT operations. Second, they face the risk of default by providing funds to the unbanked and underbanked. The micro size of the enterprises that BMTs serve, the risk for BMTs in providing financial services to small and medium enterprises, and the limited regulation of the micro-enterprise sector underline the sector’s vulnerable characteristics for BMTs. Third, they face growing religiosity, cultural changes and a dynamic political situation due to the rise in religious conservatism across Indonesia. Lastly, they have a limited organisational network that can act as a buffer for risks such as the liquidity risk that is predominant in the sector. Furthermore, BMTs lack human resources with the right skills and appropriate knowledge to understand BMT practices, manage cooperatives, and maintain product or service standards and quality.

The number of incidents of fraud disrupt BMTs’ values and add further challenges to their operation. In this paper, the researcher examines whether the occurrence of fraud influences BMT values and disrupts governance structures in non-traditional organisations in Indonesian BMTs. The researcher seeks to contribute to the literature on how religious and cultural values affect the governance of cooperatives. The focus is on a specific value interplay process based on stakeholder perceptions of BMTs to understand how internalised values are disrupted by fraud incidents and affect organisation governance.

2.3. Stakeholder theory and BMTs

The researcher analyses BMT values using stakeholder theory (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984) by conducting a documentary analysis of the BMT fraud incidents from 2007 to 2017. The documents reviewed include police reports, court rulings, media archives such as local newspapers, social media posts by stakeholders on platforms such as Twitter and Instagram, and so on. This paper echoes Laplume’s et al.’s (Citation2008) argument that several areas in stakeholder theory remain insufficiently investigated, particularly the not-for-profit, small businesses, and family firms in emerging markets. This study contributes to the literature that explores how cultural and religious perspectives influence CG theories, such as those discussed in Beekun and Badawi (Citation2005), particularly the importance of corporate governance in non-traditional organisations like BMTs.

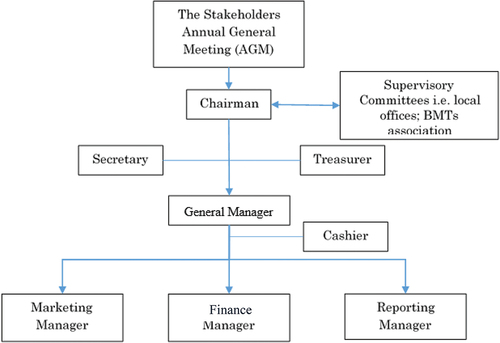

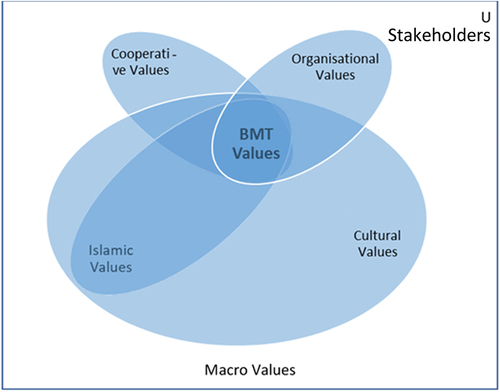

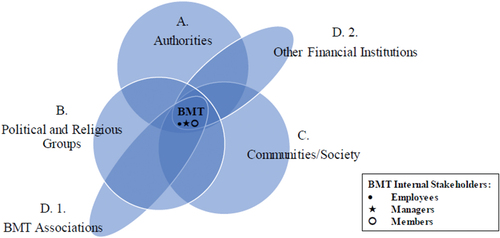

A model of BMT stakeholder groups and value relations, modified from the Donaldson and Preston (Citation1995, p. 69), is depicted in below:

Figure 1. Model of BMT stakeholder groups.

Using the modified Donaldson and Preston (Citation1995) model depicted above, the researcher identifies several underexamined factors in current BMT CG mechanisms that ignore the extreme institutional environment in which they operate.

First, the unregulated environment (A) relates to the role of authorities; while BMTs have a significant impact on poverty alleviation and the Indonesian economy, little is known about their regulation and even less is known about their financial reporting practices and standards because their financial reporting is not regulated by any appropriate authorities. The BMTs should provide annual financial reports to the Ministry of Cooperatives; however, the reports are neither reviewed nor audited by professional accountants. The laws regarding cooperatives and other microfinance organisations do not stipulate any requirements related to the content of financial reports. The Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (the financial services authority) focuses more on banking than non-banking financial institutions. The financial services authority requires any organisations that collect and distribute funds to and from people to be rigorously monitored; most BMT choose the cooperative form to avoid this requirement (therefore, they will be monitored by the Ministry of Cooperatives which is less strict than the financial services authority in terms of financial reporting). In the absence of regulatory requirements, it is likely that other forces, for instance, the community, create a demand for financial statements. However, the main users/beneficiaries of BMTs are usually less sophisticated individuals who have little knowledge and education; they are not aware of their right to demand financial and non-financial reports. Stakeholder protection is also generally very poor because the authorities (i.e. the Ministry of Cooperatives) offer limited assistance or legal protection from fraud.

Second, cultural changes and a dynamic political situation have resulted from the rise in religious conservatism across Indonesia (B). Notwithstanding that Indonesia has the fourth-largest Muslim population globally, with 87.2% of its citizens being Muslim, the law in Indonesia is based on civil law, not Islamic law (sharia). Islam and its logic are dominant, but sharia law is only used selectively in Indonesia (i.e. mainly while worshipping). However, there is growing attention to the idea of fully adopting Islamic values into civil law. Pepinsky et al. (Citation2018) argue that the growing piety in Indonesia has gained considerable media attention.

Religion has indeed come to dominate Indonesian politics, particularly in some political events such as gubernatorial and recent presidential elections. For example, the media has reported on the rise in sectarianism; Hermawan (Citation2019, p. 3) stated, “sectarianism is on the rise, and Islamist groups, once considered fringe, have become mainstream and normalised. These factors played a crucial role in determining the outcome of the Jakarta gubernatorial election.” Another example was the formation of a new BMT, named “Koperasi Syariah 212”, in December 2012 as a symbol of the Islamic movement towards Muslim independence from non-Muslim economic expansionism. These faith-based political activities show the growing interest and motivation of people joining, supporting, and conveying loyalty to Islamic products and organisations, including BMTs, and the growing numbers of people who feel Islam should play a bigger role in public life. This results in pressure to acknowledge religious values in organisation structures, including governance mechanisms. This includes the necessity of political and religious leaders’ involvement or representation in the BMT leadership boards. Financial organisations abroad do not face these extreme cultural changes, and these conditions challenge BMTs to find suitable and sustainable cooperative governance systems.

Third, BMTs operations include a high degree of financial risk, as they serve unbanked and underbanked people (C); therefore, BMTs have more risk than the more common and formal banking financial institutions, particularly credit risk (or namely “non-performing financing” in Islamic organisations). BMTs rely on the good intentions of the users and control or monitoring from communities and associations that are still very much limited.

Finally, BMT network risk (D) relates to the role of competitors that is not limited to conventional (non-Islamic) cooperatives but includes other non-banking and banking financial institutions. Both non-traditional and traditional financial institutions such as banks pay attention to 98.79% of the SME financing market. Competition has traditionally been considered a source of excessive risk-taking, and, as a consequence, regulation has tried to control it (Matutes & Vives, Citation2000). Each BMT competes with other BMTs, conventional cooperatives, and rural banks. Many rural, conventional and Islamic banks have opened a special unit to serve the SME players. Eni V. Panggabean, Executive Director of Financial Access and SME Development Department, Bank Indonesia, stated that, at the end of 2012, Bank Indonesia had mandated that 20% of bank loan portfolios should be lent to the small and medium enterprises segment by 2018. Consequently, similar to BMTs, these units also provide convenient lending. Whilst a BMT must operate within the fragile environmental factors outlined above, they still need to compete with the more formal financial institutions such as banks, including rural banks, which have established networks, infrastructure and human resources. BMTs may join existing BMT associations in Indonesia to reduce the network risk as they can build a network of interlinked BMTs and strengthen their bargaining position with competitors.

In addition to the external institutional factors, BMTs also suffer from fragile internal institutional factors. For instance, they may be lacking human resources with the skill and knowledge to understand BMT practices, manage cooperatives, and maintain product standards and quality (Wardiwiyono, Citation2012). As cooperatives, BMTs have annual general meetings (AGMs) (known, in the case of BMTs, as Rapat Anggota Tahunan or general assembly meetings) as one of their internal control mechanisms. At the AGM, stakeholders, particularly members and employees, can raise their concerns and question the leadership about the organisation’s progress. It is important to have supporting staff (especially board members and employees) who understand the required organisational practices, including financial and legal knowledge. Therefore, this paper aims to examine the fragile institutional environment of BMTs, fraud incidents that cause values disruption in BMT, and the relationship of values disruption to the governance of cooperatives. Hence, the paper contributes by giving insights and recommendations for BMT CG developments.

In general terms, cooperatives can be categorised as either the Rochdale type (similar to producer cooperatives and agricultural cooperatives) or the Raiffeisen type (similar to consumer cooperatives). In early stage of development in 1932, Rochdale cooperatives adopt the principle of neutrality in political and religious. However, following the establishment of The International Co-operative Alliance, Rochdale cooperatives support democratic governance. BMTs follow the principles of the Rochdale cooperatives (see Birchall, Citation2012). Davidovic (Citation1967, p. 228) described these principles and they can help to analyse the situation with BMTs: 1) Membership of a BMT is voluntary and available; 2) members have an equal right to vote (one member-one vote); 3) any surplus is distributed in proportion to members’ participation; 4) BMTs should make provisions for the education of the stakeholders; 5) BMTs should best serve the interests of their members and their communities. However, due to two of their characteristics, namely that the coverage of BMTs is still limited to a geographical location (i.e. serving local communities) and BMTs serve religious interests (i.e. Islamic principles), BMTs can also be categorised as a Raiffeisen type of cooperative. By adopting Islamic principles and considering the fragile political environment, the formation of a BMT leads to the abandonment of one of the main principles seen in a Rochdale cooperative, which is the principle of neutrality.

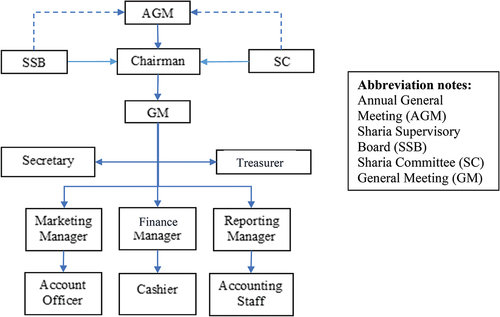

BMTs normally adopt a similar organisational structure to cooperatives (Riwajanti, Citation2013). F. R. Chaddad and Cook (Citation2004, p. 350) argue that a cooperative is constructed by three main agents: members, patrons, and investors. In a traditional cooperative, the rights are restricted to member-patrons, and the benefits are distributed in proportion to the members’ patronage. This is also the case for BMTs. Among the many forms of BMT, such as non-formal, semi, and formal organisations, the researcher analyses the formal type of BMT that operates in the form of a cooperative. Prakash (Citation2003) categorised the cooperative stakeholder into four main groups: members, employees, community, and managerial boards. However, there is no such uniformity in terms of the cooperatives’ structure; it depends on the organisational characteristics, region, and communities. The typical cooperative governance mechanism of a BMT is shown below:

In Figure , two main flawed models that allow fraud to take place can be identified. First, the most important element in the Islamic organisations, the Dewan Pengawas Syariah (sharia supervisory boards), is missing. The role of sharia supervisory boards is essential as the sharia gatekeeper maintaining the organisation’s compliance with Islamic principles (Rahajeng, Citation2011). Members of sharia supervisory boards are responsible for overseeing the implementation of Islamic principles in an organisation’s products and activities and detecting any noncompliance that leads to error or fraud. Therefore, their role should be acknowledged and clearly depicted in the cooperative governance mechanism, and not merely be part of the supervisory committee (SC).

Following the two tiers of CG mechanisms, sharia supervisory boards should also be at the same level of authority as the chairman so that they can push the chairman and general manager to respond and implement corrective actions immediately for any irregularities or red flags in the organisation. For instance, if the sharia supervisory boards find any irregularities such as accounting anomalies, they can push the chairman and general manager to investigate and bring it before the AGM to make stakeholders aware.

The existing condition in Figure fails to provide the parallel level of authority of sharia supervisory boards and supervisory committees. If the supervisory committee and the supervisory board were not sharing the same level of line authority, it could cause the less strong advisory and monitoring activities (for instance, the supervisory board cannot necessarily push their recommendation to the board to be immediately implemented, without the push from the AGM as the ultimate decision-making level in BMTs). The line of authority between the supervisory committee and the chairman should also be parallel so that the supervisory committee and sharia supervisory board can insist that the chairman and general manager follow specific recommendations, particularly for fraud detection and prevention activities. Therefore, this research recommends the revised model for BMTs shown which is shown in Figure below:

3. Data and methodology

The research consisted of two stages. The first was a content analysis of the relevant documents, followed by 38 interviews stemming from the results of the content analysis. In the first stage, the researcher analysed the documents on fraud cases in BMT cooperatives from 2006. The content analysis of the relevant documents and literature was followed by initial coding that depicted the nodes used for the analysis. Although the initial codes were too general, these codes were essential in constructing the interview questions; the questions seek confirmation and opinions on the preliminary findings from the content analysis. The compiled coding scheme was constructed after the interviews. The reseracher compiled the coding book together with the nodes extracted from interview transcription. These coding books have been analysed using stakeholder theory (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984) to answer the research questions.

To obtain further insights and nuances regarding these cases and to cross-check information derived from multiple sources, semi-structured interviews were conducted with stakeholders. This allowed the researcher to explore a series of predetermined but open-ended questions. The interviews identified the value interplay of stakeholders during the incidents of fraud. Before conducting the 38 interviews, a pilot study was conducted consisting of three in-depth interviews with stakeholders representing the leadership board, members, and authority from both fraudulent and trustworthy BMTs. The results prompted some modification of the interview instrument. By interviewing different stakeholder groups, such as managers, members, community, and authorities, the researcher was able to carry out data triangulation to cross-check information and obtain a better understanding from various perspectives. Most of the interviews were recorded, and notes were taken during all of them. However, a key interviewee from one of the fraudulent BMTs, BMT Perdana Surya Utama (PSU) Malang, East Java, refused to be recorded due his personal preference. The transcripts and notes taken were coded using the NVivo11 software package.

The findings from investigating fraud by using two different sources of information (i.e. primary and secondary) were further substantiated and verified (Citation2008). The paper provides micro-level evidence of fraud disruption on the governance of value-based and membership-based organisations (i.e. BMTs) in emerging markets (i.e. Indonesia). Therefore, the study adds to the empirical evidence on the cooperative sector’s engagement with values such as culture and religion.

The sample comprised thirty-eight (38) interviews from both BMT groups representing each stakeholder group (see the detailed distribution of interviewees in Table ). They were selected through referral sampling which was gained from the pilot study.

Table 1. Distribution of interviewees

The pilot study was conducted with three in-depth interviews with the Directors of BMT associations in Indonesia, BMT users, and Ministry of Cooperatives officers. The rationale for conducting the pilot interview with the Directors of the BMT association he was that they had sufficient knowledge and skills regarding the Islamic cooperative industry, they owned a BMT, worked with BMT-related industries, and were currently directing one of the leading BMT associations in Indonesia. Moreover, they were the key persons to provide details of other interviewees. Therefore, building rapport with them through the pilot study was essential. The rationale for the BMT users and Ministry of Cooperatives officers were to ascertain their insights on BMT circumstances as well as give updates on current Ministry of Cooperatives activities in Indonesia.

There was no maximum number of interviewees, although the period over which the study carried out was limited. There was no exact way of determining the sample size required since the study aims to gain in-depth knowledge about frauds and stakeholders’ perceptions of fraud. Therefore, the sampling size was determined based on three main factors: the information power of the sample, the fair distribution of stakeholder groups and the interviewees’ availability, and data saturation.

Many of the studies included references to theoretical or data saturation as described by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967, p. 65) who define data saturation as the point at which “no additional data are being found whereby the researcher can develop properties of the category and become empirically confident that a category is saturated.” Strauss and Corbin (Citation1990, p. 136) argue that saturation is a “matter of degree” determined by the researchers by familiarising themselves and analysing their data for new information to emerge so that they add something to the overall story, model, theory or framework. Data saturation can be reached by conducting interviews until the point at which the last few interviews have not provided new insights; or “when themes begin arising over and over in these interviews” (Forte, Larco, and Bruckman, Citation2009, p. 54); or when further coding is no longer feasible. There is no statistical demonstration of sample size to reach data saturation; the many factors that can influence it include quality of dialogue in terms of answering the key research questions, the number of interviews per participant, sampling procedures, and researcher experience/judgment (Sandelowski, Citation1995).

In this research, the data saturation point was reached when no new additional data were found in the interviews and documents. This paper discovered that, after a certain number of interviews, there were themes being raised repeatedly, as was the case with the documents, and no new themes were emerging. At this point, it was concluded that the data saturation point had been reached.

Table shows the range of BMT stakeholders in Indonesia who were interviewed and shared related documents for the supporting analysis. The notes column shows additional information regarding respondents which was relevant in order to understand their position in the cases, their background and values, as well as understanding their capacity to provide certain comments/perspectives needed in this study.

The sample represents different BMT clusters in Indonesia, such as the Sumatran cluster (South Sumatra), the West Java cluster, Central Java cluster (Yogyakarta and Central Java), and the East Java cluster. Each cluster reflects the rapid growth of BMTs in Indonesia. The BMT stakeholder consisted of internal stakeholder groups such as group A (governing boards, managers, employee), group B (members), group D (beneficiaries), and external stakeholder groups such as group C (authorities) and group D (communities).

Table also shows that most of the respondents were from the non-failed BMTs. The reseracher could not conduct any interviews with the fraudsters because the whereabouts of those that had been released from prison was unknown. Due to confidentiality issues, the officials also refused to share their addresses. One fraudster passed away during their prison term due to illness. The researcher also could not use any trial documentation such as fraudster testimony because those documents are not available to the public. The only publicly available document, evidence from the court ruling on criminal offence from the supreme court’s website, is analysed in the next section.

4. Result

4.1. Fraud as a disruptor of the values of an organisation

Most interviewees agreed that internal control was very poor due to ineffective AGMs and weak supervisory boards. One interviewee (MAN8.1) admitted that internal controls in the failed BMT were missing. MAN8.1 added that this gap was seen as an opportunity by the fraudster (i.e. the general manager) to misuse his power over the organisation.

There was no such internal control at all from anyone, including the supervisory board. He [the general manager/the fraudster] totally dominated the board and never listened to us [other directors]. (MAN8.1)

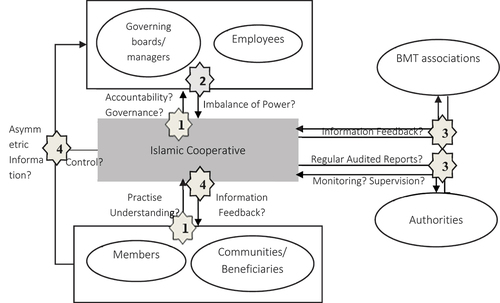

Figure shows that the instances of fraud in BMTs are considered a systematic failure of Islamic cooperative governance in Indonesia. All stakeholder groups have a part to play in these failures. They are responsible for these incidents as they have an essential role in stopping fraud before it starts. For instance, at point 1, members could educate themselves on how the organisation works hence they could be more involved as part of internal control mechanisms. Even though some interviewees confirmed that the purpose of BMTs is not only to conduct business but also spread Islamic values, in practice, the business is more dominant than the values (overlapping values). Therefore, understanding the practice is an essential issue for stakeholders.

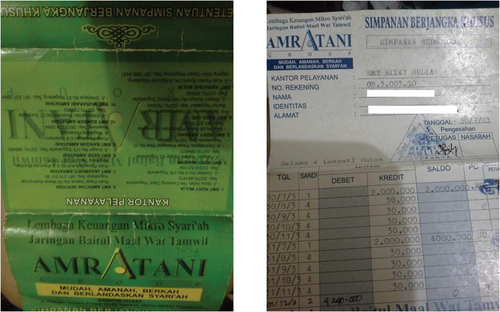

CUST7, a victim of the failed BMT Amratani,Footnote4 also stated that the supervisory board in the BMT was weak. There was no control system to prevent abuse of power in BMT Amratani, which provided opportunities to commit fraud due to the lack of internal control.

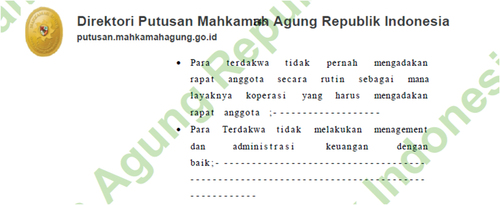

The supporting evidence from the court ruling on criminal offence which shown in stated that defendants were convicted of fraud due to abuses of power as managers.

Figure 5. Evidence from court ruling on criminal offense.

The first paragraph of the evidence above translates as: ”the defendants did not appropriately conduct the regular annual members assembly which is mandatory for a cooperative.” The second paragraph states that: “the defendants did not manage the cooperative well and failed to provide good financial administration.”

The court ruling provides evidence that there were flaws in internal monitoring, inspection and accountability; the general assemblies that are part of internal control were not functioning properly. Such an environment may undermine stakeholder rights, as the AGM is one of the main governance mechanisms that enable managers to be held accountable to stakeholders. As F. Chaddad and Iliopoulos (Citation2013) point out, the general assembly is a mechanism for members to exercise their roles in decision control.

According to stakeholder theory (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984), all interested parties have equivalent rights in the organisation; therefore, in the BMT case, members should be involved in any strategic decision-making processes relating to BMT activities through the AGM. In a cooperative, strategic decisions should be confirmed in the general assembly, which is supposed to be the highest decision-making level and requires members’ approval; members should be the key and strongest stakeholders in BMTs.

Moral hazard is the main theme in the managers’ perceptions about what causes fraud. One of the managers from a successful BMT stated that it is more the internal (personal) factors that cause fraud: changing values (lifestyles) and losing the BMT spirit/motivations (ghirah).

People change their lifestyle. When they started, they just had a small amount of money, but when the BMT grew and became so huge, they changed their way of life. Secondly, they don’t have a good religious background; no amanah (upholding trust). They misuse the BMT’s money for personal benefits, not for the organisation. The BMT spirit was not there. (MAN3)

The finding shows conflicting values between micro-individual values (i.e. economic values) and macro-organisational values (i.e. BMT values to obey Islamic ethics such as dzalim, or not doing any harm to others).

MAN3ʹs statement underlines conflicts of interest between the individual and the organisation. The individual values (i.e. financial and lifestyle pressures) interrupt the ongoing organisation values of BMTs (i.e. benefiting society). The fraud incidents disrupt current organisational values; the fraudster aimed for personal benefit and neglected the organisation’s benefit and trust. Greenwood and van Buren (Citation2010) stated that in certain situations, the firm (i.e. manager in the fraudulent BMT) holds greater power than the stakeholder and therefore cannot necessarily be trusted to return the duty to the stakeholder. The fraudster was motivated by greed. The basic fraud model, Cressey’s (Citation1953) fraud triangle, explains that greed is the financial pressure that justifies the perpetrator’s behaviour to claim stakeholders’ money as their own. Braithwaite (Citation1992) claims that greed is “socially constructed as insatiable wants” (p. 80) that “can never be satisfied” (p. 84) as it is rooted in the individual’s character. This issue highlighted the conflicting individual and organisational values.

4.2. Value creation: The influence of religious and cultural values in BMTs

Values are affected by many inherent factors (i.e. ethnicity, religions, political stands). The author distinguishes between cultural and religious values, defining cultural values as related more to ethnicity because ethnic identity appears to be an important determinant of cultural norms, values, and preferences. Culture is a notoriously overbroad concept. The debates on multiculturalism mainly fall along the lines of ethnicity perspectives, language, adaptation of religion, nationality, and race. All these categories have been incorporated into the notion of culture.

For example, Java, the world’s most populous island, has a Muslim majority population and is considered a melting pot of religions and cultures. Java is rich in religious syncretisms, such as the Islamist-traditionalist (including priyayi, abangan) and Islam-modernist (such as santri; Geertz, Citation1981). The specific Javanese cultural values imaged by the sultanatesFootnote6 are valid if Islam is syncretic, although not in a specific or absolute sense. Although Geertz’s categorisation is debatable and irrelevant today, Javanese society still maintains traditional rituals such as prayers for the dead (tahlilan)Footnote7 and communal feasts (slametan)7. Culture is attached to the community whose values have changed from a Hindu–Buddhist pattern to Islam. It shows the dynamic interplay between Islam and local tradition in Indonesia. Culture explains how local Muslims have differed in their interpretation and application of Islam, especially in Java and Sumatra. It looks at processes of religious change as a world religion interacts with local cultures. Therefore, it explains that religion and culture fall under different domains yet share values in forming the society.

The author echoes Desmet et al.’s (Citation2017) argument that ethnic identity is a significant predictor of cultural values. Cultural heterogeneity and ethnic heterogeneity are two sides of the same coin. The level of ethnic diversity arises in groups of people who live in different geographical locations and have heterogeneous values, norms, and attitudes: the broad set of traits that we will refer to as “culture”. The author also refers to religious values as Islamic values in the context of BMTs; Muslims constitute more than 87.2% of the population.

This paper defines Islamic values as ethical principles described in the terminology of Al-Ghazali’s (Citation1989) concept of virtue. Al-Ghazali identifies five essential components for wellbeing in this world: religion, life, intellect, offspring, and property (Opwis, Citation2019). Al-Ghazali also identifies three distinct goals of economic activities, which are virtuous for their own sake and represent part of one’s religious duties. These include maintaining self-sufficiency, helping one’s progeny, and helping those in economic need. According to Al-Ghazali, true Islamic behaviour is characterised by this highest level of voluntary sharing and giving. Al-Ghazali is critical of what he calls excessive profit-making and suggests that businesses refrain from accepting high profits, even when those profits are obtained without fraud (Ghazanfar & Islahi, Citation1990).

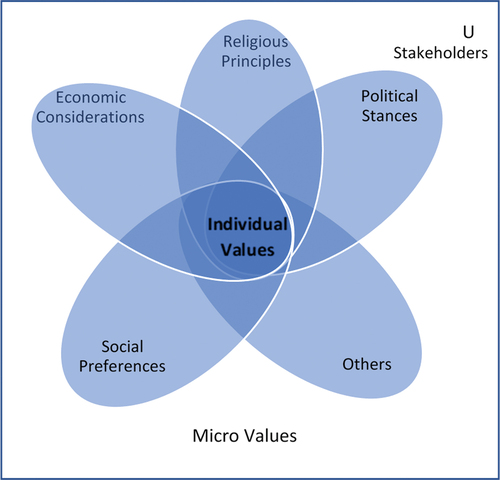

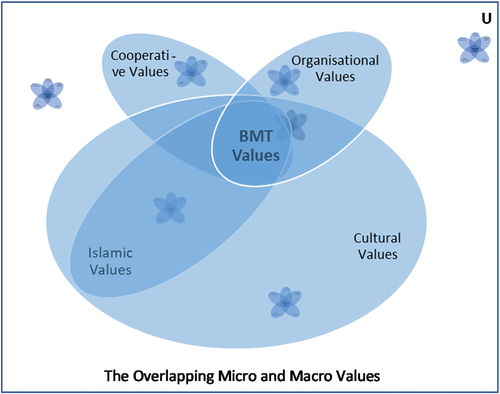

However, some elements overlap between micro (individual) and macro values (especially Islamic and cultural values). The observation and interview data suggest that stakeholders are seen as individuals who are isolatable units from the institutions. Although they shared some values (i.e. cultural and religious ones) that have well-defined boundaries, the individuals can be considered separate from their environments and are a separable part of the society in which they function. Therefore, individuals in each stakeholder group have boundaries that define their unique values, characters, and interests. The interplay of each value is illustrated in below:

The above diagram shows five main micro values, the intrinsic values of stakeholders that influence the values of a BMT: 1) Religious principles; 2) Political stances; 3) Social preferences; 4). Economic motives; 5) Other factors (i.e. pragmatism). The micro values can be considered as the fundamental values of each individual. Some groups of stakeholders join BMTs based on religious perspectives; however, many stakeholders join BMTs due to their practicality. One stakeholder describes:

I was interested in joining this BMT [PSU, Malang, East Java] simply because their service was very good, easy to withdraw some money as they [AO, account office] usually come here, so we don’t need to go to the office, no fees, only admin fees when we open an account; that’s what I like from it [BMT PSU]. In [BMT] Sidogiri, they also have profit-sharing, but not in the PSU. (CUST4)

One interviewee also stated that her motivation to join the BMT was due to its competitive interest rate compared to other financial institutions (banks). She was promised a fixed investment rate in the fraudulent BMT Amratani Yogyakarta.

I checked how much I would get if I put my money in the bank compared to the sharia banks. That was in 2003. In this BMT [Amratani], if I put Rp 1 million, I will get Rp 25,000 per month. Multiplied by how much we put our money there. Well, that’s good then! It could be like my kids’ education insurance! (CUST7)

Novkovic’s (Citation2006) study also considers that economic values (i.e. profit) remain the primary goal for individuals within financial institutions. BEN3 argues that most BMT users were not necessarily pursuing Islamic values in the BMT as they were mainly pursuing their individual values, that is, the benefits from saving with the BMT.

The most pragmatic reasons are: what are the benefits, whether the location is in a nearby area, whether it’s easy to get soft loans, etc., so merely based on technical practice, what’s my benefit? That’s it. On average, people tend to think pragmatically. Religion is the nth-number of factors, not the first. (BEN3)

However, some interviewees also have individual values that support the BMTs. One respondent stated that their preferences for joining BMTs as a Muslim were to utilise Islamic institutions such as a BMT. The interviewee stated:

I felt that this is our responsibility as Muslims to promote and utilise the BMT as one of the Islamic institutions. If not us, then who else? (CUST2)

The interplay of personal values (both the contradicting and supporting values) shows the significance of micro values in shaping the overall BMT values, particularly stakeholders’ religious values. The value creation (interplay of values) of BMTs is also influenced by macro values that represent the organisational values, cooperative values, and cultural values (including Islamic values). The interplay of each macro value is depicted in below:

The sizes of the circles and the overlaps in Figure correspond to the approximate relationships as inferred from the data sets. As evident, the controlling values in the BMT organisations are cultural ones. Stakeholder perceptions are shaped by the interplay between micro and macro values. This interplay includes value interplay (creation and co-creation of values that influence other values) and the creation of supporting and conflicting values. However, individual values are created by other values: religious principles, social preferences, economic motives, and so on; individual values are mutually dependent on external values. The external values are less significant to individuals in how they shape their values. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the interplay between each value that emerges internally and externally because the interrelationship of these values (i.e. conflicting values that the BMT does not fully follow Islamic values) may be why frauds occur. Figure below depicts the overlapping values of micro values (the small stars) and macro values (the larger diagram) in the BMTs as below:

The interplay between both values defined the stakeholders’ value creation. The individual values in Figure are depicted as symbol ![]() which represent all individuals inside and outside organisation who are spread in many level and layer of organisations, communities, and societies. It shows that individuals could adopt only cultural values, both cultural and Islamic values, or combination between cultural, Islamic, cooperative and general organisational values. Therefore, the existing individual values are embedded in their routines formal or informal activities.

which represent all individuals inside and outside organisation who are spread in many level and layer of organisations, communities, and societies. It shows that individuals could adopt only cultural values, both cultural and Islamic values, or combination between cultural, Islamic, cooperative and general organisational values. Therefore, the existing individual values are embedded in their routines formal or informal activities.

According to stakeholder theory (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984), values are the central factors that frame an individual’s interests, perspectives, beliefs, traditions, habits, routines, attitudes, responses, and activities. Therefore, in the BMT fraud context, no matter how strong other values are (especially the Islamic, cooperative, cultural values), if the micro values are not well aligned with BMT values, it could be hard to control any conflicting values or interests that may cause frauds to occur.

4.3. Governance structure

The legal form of a BMT as a cooperative is, to some extent, unsuitable for the organisation’s characteristics. Many factors are involved in shaping BMT characteristics, such as their dual purpose in both benefiting the organisation and contributing to society. BMTs still need to make some profit for their operations, but on a reasonable basis, not on a profit maximisation basis like a corporation.

Based on the analysis in the documents of cooperative regulation, the 1992 regulation was updated to Act of The Republic of Indonesia No. 17 of 2012; however, due to public objections regarding this regulation’s compatibility with BMT and Islamic cooperative characteristics, the latter regulation was cancelled by the Constitutional Court of Republic of Indonesia. The Court considered that Law No. 17 of 2012, which was a new cooperative law, was not compatible with the nature of the cooperative. Therefore, the law was cancelled in 2014, and the previous law (i.e. No. 25 of 1992) was reinstated. Public objections were due to fundamental changes in 17 articles in the new law (Law No. 17 of 2012): amendments to the BMT legal forms, which were perceived by the cooperatives to make the BMTs look more like a corporation than a cooperative. Stakeholder arguments covered by the national newspapers stated that the newest regulation changed the terms gotong royong (mutual assistance) and kekeluargaan (kinship values) in the articles into profit-oriented, corporate values (Sahbani, Citation2014).

One BMT that adopts Islamic values argued that those values go beyond others because following Islamic values is essential and is a part of daily life for Muslims.

Honestly, the BMT form as a cooperative is not ideal since it contradicts BMT characteristics. For instance, the BMT role is bridging between the Shohibul Maal (fund providers) and Mudarib (skill/expertise and management providers). From there, it’s not like a member-based organisation, but more into a community-based organisation. Hence, BMT may suit an LKM’s (Lembaga Keuangan Mikro/Islamic microbank) form, as they can serve non-members (customers) as well. (BEN6)

This respondent also pointed out that the current BMTs’ capital structure is different from a cooperative’s structure. In Indonesia, a cooperative is structured according to three types of member contributions: membership (simpanan pokok), mandatory capital (simpanan wajib), and voluntary capital (simpanan sukarela). Each member is limited to only one vote, no matter how much they have in savings. BEN6 stated that this situation is different in BMTs as the organisational structure consists of the Shohibul Maal (capital provider; donor in a charity organisation) and Mudarib (skilled entrepreneurs or capital managers). This relation infers that the Shohibul Maal’s voice has more power than other common members because they can have more capital in their voluntary accounts.

In the capital perspective, a BMT is constructed by the relationship of Shohibul Maal and Mudarib; therefore, the members should not be limited to the amount of the subscribed capital but follow the Shohibul Maal’s ability to invest in the organisation. Therefore, from three types of capital (i.e. membership/simpanan pokok, mandatory capital/simpanan wajib, and voluntary capital/simpanan sukarela), the amount of membership and mandatory capital can be equal for all members, but the voluntary capital should not be limited or defined by the organisation for each creditor. (BEN6)

BEN6 added that it is possible to have an additional account named simpanan pokok khusus (stock) to accommodate the ownership rights, particularly representing the additional capital from the shahibul maal. This affects the ownership structure, membership policy, voting rights, and governance structures because the organisation will not implement a pure one-member-one-vote principle but instead uses a combination with one-share-one-vote like many profit-oriented corporations. BEN6 stated that BMTs should have to adopt the one-share-one-vote structure before choosing the cooperative form. Some BMTs might want to choose another legal status as a Lembaga Keuangan Mikro Syariah (Islamic microbank) instead of a cooperative.

The lack of clarity in the BMTs’ legal status is, to some extent, contributing to fraud because the interviewees admitted their confusion as to whether a BMT is a cooperative, microbank, rotating-savings group or credit association, NGO, or other. They stated that they were unsure how they see their ownership rights assigned contractually to the organisations because the BMTs had not informed their members of their membership status.

BMT, cooperatives, and Islamic microbanks are different. The laws only cover the cooperative and microbank forms of organisations. BMTs tends to be like microbanks but was accidentally put into the cooperative form. Even so, BMT’s ‘sex’ [the respondent literally stated this to underline his annoyance on what the BMT actually forms] does not exactly suit a cooperative. But, yeah, that’s the fact. We usually joke by saying: if a cooperative is truly following the laws, it would not be as big as now; a growing cooperative is the one that disobeys the law [grinning]. (MAN3)

The confusion was experienced by the members and even the organisations themselves. The documents below were shared by one of the victims of BMT Amratani, Yogyakarta (the failed BMT), which showed the organisation’s confusion regarding its BMT form.

The above documents (Figure ) are translated as One Fraudulent BMT (see the title of each page: Amratani). The organisation called itself an Islamic microbank (see the green image on the left). If the BMT is under the Islamic microbank form, they were supposed to be monitored by the financial services authority, yet this BMT introduced itself as a BMT and registered under the Ministry of Cooperatives, not the financial services authority. Their account book picture on the right also stated that they were an Islamic microbank (see top left in picture). Therefore, these documents confirmed the ambiguousness of the BMT’s identity. Another fraudulent BMT (BMT PSU in Malang, East Java) also clearly stated that they were a Lembaga Keuangan Syariah (Islamic finance institution or microbank)Footnote5 in their main logo (see Figure ), both in their headquarters (image on the left showing the building) and on the letterhead (image on the right showing paperwork).

Figure 10. Logo of BMT PSU Malang, East Java as an Islamic finance institution.

BMTs currently fit uncomfortably into existing organisational paradigms. The occurrence of major frauds involving BMTs and the consequent social and economic impact on stakeholders suggest there is a need for a new and broad institutional approach to BMT cooperative governance mechanisms that can accommodate the form’s characteristics. Some BMTs moved from an equitable distribution of dividends based on patronage to a shareholding-based distribution, and others BMTs categorised themselves as microbanks, rotating-savings group or credit associations, and NGOs.

BMTs should choose the particular cooperative governance mechanism that suits them. A BMT could become like a microbank- supervised by the financial services authority while continuing business as usual, collecting and distributing public funds. A BMT could become an NGO that cannot collect and distribute funds from members as its primary business line but remains a social platform with a focus on a particular mission (such as poverty alleviation, financial literacy, and community development). A BMT could also become a non-formal organisation such as a rotating-savings group or credit association without such formal monitoring apart from voluntary community monitoring. In addition, a BMT can also adopt the current cooperative governance mechanism with minority shareholder involvement in the AGM. Given that the frauds occur due to the imbalance and domination of negative individual values during the monitoring process, there is a crucial need for independent and reliable monitoring elements to establish adequate supervision and anticipate the misbehaviour of management.

5. Discussion and conclusions

There is a gap in BMT practice due to discrepancies and conflicts between micro (individual) and macro (Islamic, cooperative, and cultural) values. Individual values are the most influential of these factors in framing stakeholders’ perceptions. No matter how strong the macro values are, if the individual’s values are not aligned, particularly with BMT values, then it could be hard to control any conflicting values or interests. The cultural background also strongly influences the way of thinking among stakeholders, including their responses to fraud. The overlapping values create an environment that encourages fraud to occur. Therefore, aligning micro/individual and macro values is essential to mitigate the probability of fraud in the future. This paper suggests that BMT needs to link BMT organisational culture to wider economic consequences and find a CG mechanism that can accommodate its characteristics rooted in religious and cultural values.

This paper also contributes to traditional corporate governance theories by adding cultural and religious perspectives to the analysis (see, Beekun & Badawi, Citation2005). Therefore, along with other literature on Islamic corporate governance such as Abu-Tapanjeh (Citation2009), Kirkpatrick and Maimbo (Citation2002), and Laplume et al. (Citation2008) which has also shaped the theoretical perspectives, this study advances corporate governance theories.

This paper addresses the gaps in CG implementation in non-traditional organisations and underlined the under-investigated CG implementation in value-based organisations. Irrespective of the challenges of an extreme institutional environment, BMTs have great potential to be a vehicle for financial inclusion and a mainstay of the Indonesian economy by providing small and medium enterprises with convenient and appropriate financial support. Therefore, the need for cooperative governance that suits the organisational characteristics is of utmost importance.

This paper also contributes to the stakeholder theory (R.E. Freeman, Citation1984) by enriching its implementation to the non-traditional organisation (such as Islamic BMT cooperatives) in an emerging economy (such as in Indonesia) in an extreme environment (such as the unregulated, competitive, risk-taking nature of operations, cultural changes and a dynamic political situation). To the best knowledge of the author, this is the first paper that has adopted stakeholder theory in an extreme context.

The stakeholder model, to some extent, can be extended to accommodate religious and cultural values in the organisation’s identity. This can be done by adding cultural and religious changes to the new BMT cooperative governance system, such as adding representatives of society, religious and political leaders and minority group members to the internal and external supervision boards. This study has also extended the previous study (see, Uddin et al., Citation2008) which underlined local peculiarities and culture in corporate governance implementation in non-traditional organisations.

This paper also has practical implications. BMTs should consider the active involvement of minority stakeholders (i.e. communities, beneficiaries, and members) in the decision-making process, including defining an organisation’s values and goals. The involvement of minority shareholders balances the domination of negative individual values that serve as the trigger for fraud. Fraudulent BMTs fail to disclose the value relevant information such as board processes and financing arrangements to their stakeholders, particularly during AGMs. Even though there are some BMT financial reports, these are still considered inadequate and artificial as they are unregulated and unstandardized and compiled only to meet the administrational enquiries from the Ministry of Cooperatives (as the BMT should submit financial reports regularly). Their involvement would develop an effective monitoring mechanism with other stakeholders and strengthen the protection mechanisms of the community investment in the BMT.

In addition, even though the BMT is an Islamic entity, it remains under threat of fraud for various reasons, while, at the same time, society remains pragmatic about their options regarding financial institutions. Hence, the findings of this study echo previous research (see, Anderson & Henehan, Citation2003; Jussila et al., Citation2008) which states that cooperatives have been accused of abandoning their original mission of benefiting members and should not aim at profit maximisation.

This paper has provided several theoretical and practical contributions relating to the value interplay in BMT Islamic cooperatives and paves the way for further research. However, it has been argued that there is no such thing as a perfectly designed study (Marshall and Rossman, Citation1989), especially if it is related to human interaction, as humans per se are characterised as complex.

The first limitation regards the nature of the research approach, which is qualitative research. A deeper understanding is possible by adopting this method. However, some insights might be missed as a consequence in this study. This is due to the interview time constraints since, for instance, most interviewees were only available to be interviewed for a maximum of two hours. Moreover, as fraud is a sensitive issue, talking about it was quite a challenge, especially for the researcher. This required the trust of interviewees, and trust cannot easily be built within one to two hours. Therefore, the researcher was pressured to build rapport from the very first contact with interviewees.

Another limitation of adopting a qualitative method was the diversity of the themes identified. Some selectivity is demonstrated by a researcher when choosing the relevant and most interesting themes (Seale, Citation2003), and so this might have caused some themes to be overlooked. Therefore, it is impossible to be fully confident that this study has covered all related aspects of fraud investigation and prevention, which implies that its contribution to policy might be incomplete.

Three main recommendations suggest new potential research inquiries. First, the use of quantitative data is needed to test the statistical generalisability of the study. For instance, researchers could use questionnaires in a survey to capture the samples of BMT groups in Indonesia. These questionnaires could use the themes developed in this study so that some testable hypotheses could be constructed. Second, adopting other methods such as ethnography may expand the views and provide an in-depth exploration into how stakeholders’ values are created. And lastly, a new direction of research could be established to assess the effectiveness of some recommendations, such as a new form of cooperative, by developing models to test the feasibility of current forms of cooperatives and the new forms of cooperative in practice.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This article is based upon parts of author unpublished dissertation.

Glossary of terms

| ABSINDO: | = | Asosiasi BMT Indonesia (The Association of BMT in Indonesia; one of BMT associations in Indonesia) |

| AGM: | = | Annual General Meeting (Rapat Anggota Tahunan) |

| Bappenas: | = | Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional (Ministry of National Development Planning of the Republic of Indonesia) |

| BMT: | = | Baitul Maal Wat Tamwil (Islamic Cooperative) |

| BMT BIF: | = | Baitul Maal Wat Tamwil Bina Ihsanul Fikri (BIF, one of the good BMTs in Yogyakarta) |

| BMT PSU: | = | Baitul Maal Wat Tamwil Perdana Surya Utama, City of Malang, East Java (one of the fraudulent BMTs) |

| DKI Jakarta: | = | Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta, the Special Province of Jakarta, Jakarta is the current Indonesia capital city |

| GDP: | = | Gross Domestic Product |

| IDR: | = | Indonesian Rupiah |

| INKOPDIT: | = | Induk Koperasi Kredit (INKOPDIT, Credit Union) |

| Inkopsyah: | = | Induk Koperasi Syariah (Centre of Shari’ah Cooperatives and BMTs; one of BMT associations in Indonesia) |

| KANINDO: | = | Koperasi Agro Niaga Indonesia (KANINDO Syariah, one of the good BMTs in East Java) |

| KJKS: | = | Koperasi Jasa Keuangan Syariah (Islamic Cooperatives for Financial Services) |

| KSPS: | = | Koperasi Simpan Pinjam Syariah (Islamic Cooperatives for Saving and Loan) |

| LKM: | = | Lembaga Keuangan Mikro (Microfinance Organization – similar to microbanks) |

| LKMS: | = | Lembaga Keuangan Mikro Syariah (Islamic microfinance organization – similar to Islamic microbanks and LKS) |

| LKS: | = | Lembaga Keuangan Syariah (similar to LKMS) |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dian Kartika Rahajeng

Dian Kartika Rahajeng is an Assistant Professor in Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She has finished her PhD in Accounting and Finance, at Essex Business School, the University of Essex, the United Kingdom, under the scholarship of Lembaga Pengelola Pendidikan, Ministry of Finance, the Republic of Indonesia. She finished her MSc in Islamic Finance, at Durham Business School, Durham University, the United Kingdom, under the scholarship of Islamic Development Bank, Saudi Arabia. She is currently reading about governance in non-traditional organisations. Her research areas are forensic auditing, fraud investigations, business ethics, Islamic accounting, and Islamic governance. She published two books on corporate governance. She is currently the Director of Strategic and Consultation Services, Shafiec Universitas Nadhlatul Ulama, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She is an educator associate member of the Association Certified Fraud Examiner. She can be contacted via email at [email protected]

Notes

1. VBOs such as political parties and religious organisations usually focus on specific objectives based on particular values and generally operate under contractual obligation to serve their members.

2. We follow the Government of Indonesia’s definition of SME. The government of Indonesia defines micro, small, and medium firms (Usaha Mikro Kecil Menengah, UMKM) based on nine main principles: they entail kinship or community self-help traditions, economic democracy, togetherness, sustainability, are fair and efficient, society-based, self-reliant, and they seek to improve the balance of national economic unity (Government of Indonesia, Citation2008).

3. Over the period 2003–2013, BMT reached a growth of 40–50%; 5,500 BMTs were spread across the country (CNN Indonesia, Citation2017). In 2014–2015, the number of BMTs decreased in some areas. However, in East Java, the sales volume of BMTs rocketed 254.05%, from IDR 170.97 billion to IDR 605.32 billion (CNN Indonesia, Citation2017).

4. One of the biggest BMT fraud cases in the Special Province of Yogyakarta (Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta/DIY), Indonesia.

5. The terms Islamic microbank (LKMS) and Islamic finance institution (LKS) are used interchangeably; both refer to the microbanks, with Islamic microbanks for LKMS and conventional microbanks for LKS or LKM.

6. The sultanate or palace is the main seat of the Sultan of Yogyakarta and his family. Related to Javanese culture, there is also the Kasunanan Surakarta Palace in Central Java. Both palaces serve as a cultural centre for the Javanese. Palace is considered as a cultural heritage that has very valuable aspect in social and economic values in a community.

7. Tahlilan means together to pray for those who have died. Geertz identifies the slametan as a “core ritual” in Javanese culture and as a prototypical animistic rite intended to reinforce village solidarity (Woodward, Citation1988).

References

- Abu-Tapanjeh, A. M. Corporate governance from the islamic perspective: A comparative analysis with OECD principles. (2009). Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 20(5), 556–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2007.12.004

- Aguilera, R. V., & Jackson, G. (2010). Comparative and international corporate governance. The Academy of Management Annals Taylor & Francis, 4(1), 485–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2010.495525

- Al-Ghazali, A. (1989). Al-Mizan. Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah.

- Al-Muharrami, S., & Hardy, D. C . (2013). Cooperative and Islamic banks: What can they learn from each other? Monetary and Capital Markets Cooperative. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp13184.pdf, .

- Allen, P. M. A complex systems approach to learning in adaptive networks. (2001). International Journal of Innovation Management, 05(2), 149–180. https://doi.org/10.1142/S136391960100035X

- Anderson, B. L., & Henehan, B. M. (2003). What gives cooperatives a bad name? International Journal of Co-operative Management, 2(2), 9–15 https://www.smu.ca/webfiles/ICJM-Vol-2-No-2-.pdf.

- Ashkenas, R. N. (1995). The boundaryless organization: Breaking the chains of organizational structure. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Azis, A. M. (2006). Tata cara pendirian BMT. PKES Publishing.

- Bappenas (2016) Masterplan Arsitektur Keuangan Syariah Indonesia. Available from: (Accessed 4 May 2019). https://www.bappenas.go.id/files/publikasi_utama/MasterplanArsitekturKeuanganSyariahIndonesia.pdf.

- Beekun, R. I. (1997). Islamic Business Ethics. International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT).

- Beekun, R. I., & Badawi, J. A. (2005). Balancing ethical responsibility among multiple organizational stakeholders: The Islamic perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-8204-5

- Berita Satu. (2020). Poverty rate lower in Indonesia: Report. Accessed 1 June 2020. Available from: https://jakartaglobe.id/news/poverty-rate-lower-in-indonesia-report.

- Birchall, J. (2003). Rediscovering the cooperative advantage: Poverty reduction through self-help. International Labour Office.

- Birchall, J. (2012). A ‘member-owned business’ approach to the classification of co-operatives and mutuals. In McDonnell, D., Macknight, E. (Eds.), The Co-operative Model in Practice: International perspectives. Scotland: CETS. https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/book-mcdonell-macknight.pdf

- Braithwaite, J. (1992). Poverty, power and white collar crime. Sutherland and the paradoxes of criminological theory. In K. Schlegel & D. Weisburd (Eds.), White collar crime reconsidered (pp. 78–108). North-Eastern University Press.

- Brennan, N. M., Solomon, J., & Brennan, N. M. Corporate governance, accountability and mechanisms of accountability: An overview. (2008). Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(7), 885–906. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570810907401

- Campion, A. (1998). Current Governance Practices of Microfinance Institutions: A Survey Summary. Microfinance Network.

- Chaddad, F. R., & Cook, M. L. Understanding new cooperative models: An ownership-control rights typology. (2004). Review of Agricultural Economics, 26(3), 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2004.00184.x

- Chaddad, F., & Iliopoulos, C. Control rights, governance, and the costs of ownership in agricultural cooperatives. (2013). Agribusiness, 29(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21328

- CNN Indonesia (2017) BI Dorong Pengembangan LKM Berbasis Syariah Available from: https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20171107181424-78-254140/bi-dorong-pengembangan-lkm-berbasis-syariah (Accessed 4 May 2019)

- Cornforth, C. (2001a) The governance of non-profit organizations: A paradox perspective. Open University Business School Paper.

- Cornforth, C. (2001b). Understanding the governance of non-profit organizations: Multiple perspectives and paradoxes.

- Coulson-Thomas, C., & Coe, T. (1991). The flat organisation: Philosophy and practice. British Institute of Management.

- Cressey, D. R. (1953). Other people’s money; A study of the social psychology of embezzlement.

- Davidovic, G. “Reformulated” Co‐Operative Principles. (1967). Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 38(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.1967.tb00190.x

- Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. Social enterprise in Europe: Recent Trends and Developments. (2008). Social Enterprise Journal, 4(3), 202–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508610810922703

- Desmet, K., Ortuño-Ortín, I., & Wacziarg, R. (2017). Culture, Ethnicity, and Diversity. American Economic Review, 107 (9), 2479–2513. Available from. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10 .1257/aer.20150243.

- Doi, Yoko World Bank. (2010). Total Financial Inclusion: A Better Tomorrow for All Indonesians. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2010/12/31/total-financial-inclusion-better-tomorrow-all-indonesians.

- Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. (1995). The Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/258887

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., Jackson, P. R. (2008). Smy, K. 5. SAGE Publications. https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/68376_Easterby_Smith___Management_and_Business_Research.pdf

- Forte, A., Larco, V., Bruckman, A. (2009). Decentralization in Wikipedia governance. Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(1), 49–72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40398966

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach (Boston: Pitman).

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., de Cole, S. et al. (2013). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Geertz, C. (1981). Priyayi dalam Masyarakat Jawa. Pustaka Jaya.

- Ghazanfar, S. M., & Islahi, A. A. Economic thought of an Arab scholastic: Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali (AH 450-505/A.D. 1058-1111). (1990). History of Political Economy, 22(2), 381–403. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182702-22-2-381

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing Company.

- Goergen, M., & Tonks, I. (2019). Introduction to special issue on sustainable corporate governance. British Journal of Management, 30(1), 3–9. Available from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10 .1111/1467-8551.12325.

- Government of Indonesia .(2008). Act of The Republic of Indonesia No. 20 of 2008 on Small Medium Enterprise. https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/39653/uu-no-20-tahun-2008

- Government of Indonesia. (2008). Act of The Republic of Indonesia No. 21 of 2008 on Islamic banking. https://www.ojk.go.id/id/kanal/perbankan/regulasi/undang-undang/pages/undang-undang-nomor-21-tahun-2008-tentang-perbankan-syariah.aspx

- Greenwood, M., & van Buren, H. J Greenwood, M., Islam, G. Trust and stakeholder theory: Trustworthiness in the organisation-stakeholder relationship. (2010). Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0414-4

- Hadad, M. D. (2015). Financial inclusion, financial regulation, and financial education in Asia Symposium on Financial Education 23-25 January 2015 https://www.slideshare.net/OECD-DAF/oecd-tokyo-fehadadmuliaman Tokyo. .

- Handy, F. Reputation as collateral: An economic analysis of the role of trustees of nonprofits. (1995). Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 24(4), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976409502400403

- Haniffa, R., & Hudaib, M. A. (2002). A theoretical framework for the development of the Islamic perspective of accounting. Accounting, Commerce and Finance: The Islamic Perspective Journal, 6(1/2), 1–71 https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Roszaini-Haniffa/publication/259678965_Haniffa_R_Hudaib_M_2011_A_Conceptual_Framework_for_Islamic_Accounting_in_Napier_C_Haniffa_R_eds_Islamic_Accounting_Edward_Elgar/links/5603da6508ae596d25920a91/Haniffa-R-Hudaib-M-2011-A-Conceptual-Framework-for-Islamic-Accounting-in-Napier-C-Haniffa-R-eds-Islamic-Accounting-Edward-Elgar.pdf.