?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The impact of monetary policy on bank performance and risk is driven by bank individual characteristics and the COVID-19 pandemic, and the joint effect of bank individual factors and the coronavirus has been under-researched so far. To fill this void, this research applies the dynamic two-step system generalized method of moments (S-GMM) estimator to a sample of representative commercial banks on a quarterly basis for a small open emerging market such as Vietnam. We find that monetary policy expansion stimulates both banks’ performance and risk in a COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, the effectiveness of monetary policy expansion on banks’ operating outcomes is dependent on the interaction between the heterogeneity of the bank’s balance sheet items and the COVID-19 outbreak. More specifically, the performance-decreasing effects of monetary policy loosening are more pronounced in banks with small size, high liquidity, low capitalization, and high credit risk in the shadow of the COVID-19 crisis. Meanwhile, the risk-increasing impacts of monetary policy easing are conspicuous in well liquid, less capitalized, and high credit risk banks in an uncertain time of the COVID-19 crisis. These results are robust to alternative proxies of monetary policy instruments.

1. Introduction

Since the end of 2019, all countries around the globe have encountered the unanticipated COVID-19 pandemic, which has taken a toll on the entire economy. The COVID-19 outbreak plunged the world into an “emergency like no other”. The IMF described the global recession as the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s and predicted that the global economy would contract by 3% in 2021 (DerbaDerbali et al., Citation2021). In response to these risks, almost all major countries have implemented monetary policy easing to boost economic growth, thereby changing the behaviors of financial markets in which banks operate (Wei & Han, Citation2021). Despite the important impact of monetary policy on bank performance and risk, there is limited evidence focusing on the impact of monetary policy pass-through on bank performance and risk (Bikker & Vervliet, Citation2018; Borio et al., Citation2017). In addition, the effect of monetary policy on the performance and risk of banks depends on the different bank-specific characteristics and an exogenous shock such as COVID-19, which remains scarce from both theoretical and empirical perspectives. Therefore, this research attempts to address the response of bank performance and risk to monetary policy shocks in the context of the COVID-19 crisis in a small open economy such as Vietnam.

Vietnam offers an appropriate case to investigate due to its several unique features. First, in the past decade, regulatory reforms have caused enormous changes in the Vietnamese banking system, which affect bank performance and risk (V. D. Dang, Citation2021). Bank system reforms, particularly in developing countries, have not provided the desired consequence, namely solid and sustainable funding sources for the economy (Khalfaoui & Derbali, Citation2021). Second, financing sources from the banking system are highly vital to economic agents in Vietnam, where the economic agents are largely dependent on banks for financing credit sources and the commercial banks still hold the dominant role in facilitating capital flows into the real economy. Third, Vietnam is considered an emerging case of relatively successful control of the COVID-19 pandemic despite ongoing complications relating to the consequences of this pandemic. The central bank has conducted monetary policy easing in response to the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, driving some changes in the operation of commercial banks.

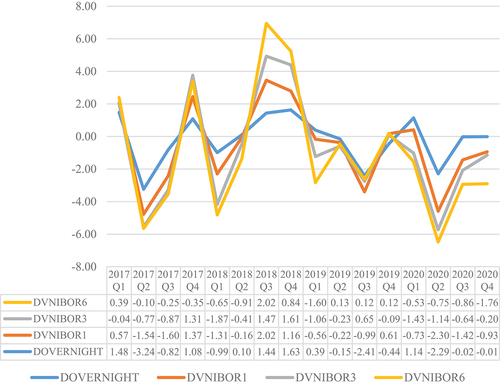

Figure shows the evolution of policy interest rates in the studied period (from Q1/2017 to Q4/2020). It can be seen that, in general, the intervention of the SBV allows the monetary policy’s interest rates to move in the same direction. Before entering the Covid-19 pandemic period, monetary policy was executed to alternate between expansion and contraction in response to different states of the economy. In addition, SBV has proactively responded to the adverse impact of the Covid-19 epidemic by reducing policy interest rates continuously from Q1/2020 (when the pandemic started to break out) to Q4/2020 (when the number of infections increases rapidly and becomes difficult to control).Footnote1 Interest rates during this period were all below zero and tended to gradually shrink (due to the phenomenon of the financing surplus of commercial banks, but this funding source did not stimulate production and business operations); meanwhile, interest rates in the previous period alternated between decreasing and increasing states to follow the real situation of the economy.

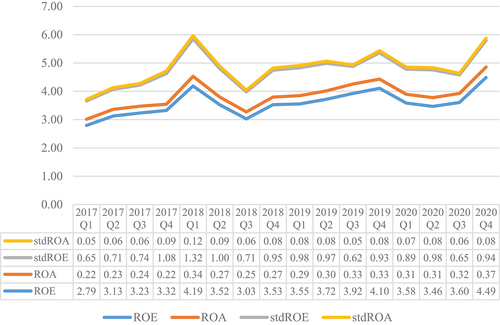

It is worth noting that monetary policy loosening (for example, a decrease in OVERNIGHT) can increase Vietnamese commercial banks’ performance (in terms of returns on equity and returns on total assets) during the time of the raging Covid-19 epidemic. Figure shows that, after interest rates fell in Q1/2020, from Q2/2020 to the end of 2020, bank performance began to increase rapidly. Specifically, in Q4/2020, ROE reached the highest average value (4.49%) compared to the second highest average value (4.19%) in Q1/2018. The same pattern goes for the value of the ROA variable (a value of 0.37% in Q4/2020 versus a value of 0.34% in Q1/2018).

This monetary expansion accords with the surplus of mobilized financing sources of Vietnamese commercial banks, possibly because investors are afraid of risks and choose banks as the main investment channel in this period. This abundant funding helps the bank improve operational efficiency. However, an interesting point is that, along with the increase in returns on equity and returns on total assets, the bank’s risk started to increase rapidly, especially after the second quarter of 2020. This may stem from the inefficiency of capital sources when economic agents are paralyzed by the epidemic and cannot absorb capital effectively. These observations need to be tested and verified quantitatively in the following sections.

For more details, to overcome the negative impact of the COVID-19 outbreak and stabilize the whole economy, the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) actively and constantly conducts monetary policy easing by cutting the policy rate three times since 1st quarterly of 2019 (NEU & JICA, Citation2020). This solution is to eliminate the obstacles of production and business operations and liquidity support for commercial banks. However, the recovery signal of the economy has not been seen to date because of the fact that the economy’s demands are severely affected due to the negative consequences of the pandemic. The commercial banks are in a state of money surplus but have not enhanced the quality of credit provision. These points are appealing to using Vietnam’s scenario to investigate the impact of monetary policy and bank performance and risk, especially in the COVID-19 crisis.

The study examines the impacts of monetary policy on bank performance and risk, as well as the joint effect of bank-specific characteristics and the COVID-19 pandemic crisis on these nexuses. Current research tests a case study of representative commercial banks in Vietnam covering the period of 2017Q1–2020Q4. The dynamic two-step system generalized method of moments (S-GMM) technique is employed to address the dynamic nature of the regression model and the endogeneity problem. During our sample period, there is little significant evidence on the impact of monetary policy on bank performance and risk. However, these relations exist under the COVID-19 pandemic in the manner that monetary policy loosening increases both performance and risk of banks. In addition, the dependence of monetary policy-bank performance and monetary policy-bank risk relations on bank-specific characteristics is also evidenced. Interestingly, the COVID-19 outbreak can weaken the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank performance and risk.

The study provides the following empirical evidence on monetary policy and bank outcomes under various conditions. First, in the study period, the transmissions of monetary policy into bank performance and risk are workable when considering the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak. Second, the impacts of monetary shocks on bank performance and risk are more conspicuous in banks with different characteristics such as size, liquidity, credit risk, and capitalization. This evidence highlights the role of bank individual characteristics in the monetary policy transmission mechanism into bank performance and risk. Third, the responses of bank performance and risk to the shocks of monetary policy depend on the joint effect of bank-specific profiles and the coronavirus crisis. This result emphasizes the weakening effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank performance and risk when considering the heterogeneity of bank characteristics.

This study contributes to the growing empirical literature in several dimensions. First, our study offers empirical evidence that the increase in bank performance and risk caused by monetary policy loosening are present in the COVID-19 crisis, which has been under-researched. Second, to the best of our understanding, we are among the first attempts to examine the differentiated effects of monetary policy on bank performance and risk across the heterogeneity of banks’ profiles. Third, this research exploits the three-way interaction term (or cubic-interactive terms), reflecting the joint effect of the bank’s profiles and the COVID-19 pandemic, which was neglected in previous research.

From this introduction, the remainder of this research is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a review of the literature. Section 3 presents the methodologies and data, followed by Section 4 discussing the research findings. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature review

In the aftermath of the prevailing coronavirus, banks have experienced severe problems related to their profitability and risk management (Wei & Han, Citation2021). To stabilize the banking system against this negative shock and achieve the desired macroeconomic goals, central banks have implemented monetary policy, which has a direct effect on bank performance and risk. Economic policies, including monetary policy, play a critical role in defining an economy’s economic development, and policy uncertainty can hinder the process (Wu et al., Citation2019). However, there is currently a challenge to using monetary policy to maintain financial stability (Derbali et al., Citation2020). More understanding regarding the impacts of monetary policy on bank performance and risk in an uncertain time caused by the COVID-19 crisis, as well as the conditionality of these impacts, is highly vital to assessing the soundness of the banking system.

2.1. The impact of monetary policy on bank risk and performance

Several studies have investigated the driving role of monetary policy on bank performance from a positively impactful direction (Berument & Froyen, Citation2015; Borio et al., Citation2017) or a negatively impactful direction (Borio & Gambacorta, Citation2017). It can be seen that the bank’s performance is driven by the shocks of monetary policy but remains inconclusive. In addition, the potential reasons for the monetary policy–bank performance relationship can be driven by the opposing directions. First, the impact of monetary policy on bank performance can be based on the changes in the bank’s interest margin. Given the fact that the elasticity of bank lending rates can be larger than that of deposit rates (Hancock, Citation1985), in the case of monetary policy loosening through cutting policy interest rates, the positive difference between interest rate-based monetary policy and deposit rates is accordingly extended. This can reduce the net interest margins and thus the bank’s performance. Second, the macroeconomic conditions can be improved due to the interest rate reduction, thus leading to a favorable funding cost for banks and improved creditworthiness for borrowers (Borio et al., Citation2017), hence increasing bank performance.

There is a growing body of literature on the bank risk-taking channel through which monetary policy can be transmitted. The majority of the research has focused on industrialized economies with near-zero or negative interest rates (Altunbas et al., Citation2012; Dell’Ariccia et al., Citation2014; Heider et al., Citation2019; Jiménez et al., Citation2014), suggesting the decreasing stability of the low interest rate. For the case of emerging countries, Chen et al. (Citation2017) present similar findings. As far as we are concerned, Buch et al. (Citation2014) and Agenor et al. (Citation2018) are the only exceptions, arguing that interest rate decreases do not inevitably put banks in riskier circumstances. The literature suggests that a policy-driven interest rate implementation can affect bank risk through several mechanisms, such as banks’ risk tolerance (Borio & Zhu, Citation2012), incentives to “search for yield” (Borio & Zhu, Citation2012; Buch et al., Citation2014), and the adverse selection problem (Dell’Ariccia et al., Citation2014).

2.2. Risk and performance of banks driven by monetary policy contingent on Covid-19 pandemic

The lessons based on the response of the monetary policy implementation of the central bank to the global financial crisis can be applied to the COVID-19 outbreak (Bhar & Malliaris, Citation2021). The decrease in interest rates and unconventional monetary policy can recover the economy from the uncertainty caused by the pandemic storm (Pinshi, Citation2020). The weakening effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on monetary policy transmission into the financial market is statistically evidenced in a sample of 37 countries severely affected by the COVID-19 outbreak (Wei & Han, Citation2021). In a time of COVID-19 crisis, monetary policy can have a significant impact on the financial markets (Yilmazkuday, Citation2021) in which the banking system operates. Additionally, in response to COVID-19 consequences, the Austrian package rescue (the Eurosystem’s targeted longer-term refinancing operations) has a significant influence on bank loan supply. However, there is no research on the effect of monetary policy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic on two important aspects of a bank such as risk and performance. This might be due to the newly unexpected nature of this pandemic from the economic perspective, leading to complicated quantification in the econometric specification. Therefore, we expect the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the impact of monetary policy on bank risk and performance to be minimal.

2.3. The distributional effect of monetary policy on bank risk and performance depending on bank individual characteristics

The conditional role of bank characteristics on the relation between monetary policy and bank performance and risk is associated with recent research on the bank lending channel and bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy pass-through, respectively. Much of the research in the lending view of monetary policy transmission looks at the balance sheet strength affecting the response of bank loan supply to monetary policy shocks (Altunbas et al., Citation2010; Gambacorta & Marques-Ibanez, Citation2011; Kashyap & Stein, Citation2000; Kishan & Opiela, Citation2000); that is, less liquid, small-sized, and poorly capitalized banks are more sensitive to monetary policy shocks than well-liquid, large- Another strand of empirical research on the bank risk-taking of monetary policy transmission depending on the different bank characteristics has been given increasing attention (Altunbas et al., Citation2012; V. D. Dang, Citation2020; Matthys et al., Citation2020). For example, Altunbas et al. (Citation2012) posit that the insulation impact against bank risk stemming from capital and liquidity of banks can be lower in a country with a low interest rate environment. Furthermore, bank risk-taking and bank lending can positively affect bank performance (V. V. Dang, Citation2019; Odonkor et al., Citation2011). Interestingly, the impact of monetary policy on bank performance is directly driven by the bank-specific features and has been under-researched to date. Therefore, it is plausible that banks with different levels of balance sheet items such as size, capitalization, and liquidity would have a difference in sensitivity to monetary policy shocks, thus causing banks to end up with variations in their performance.

2.4. The joint effect of monetary policy and Covid-19 pandemic on bank risk and performance contingent on bank-specific characteristics

Heryán and Tzeremes (Citation2017) indicate that the response of bank loan supply to monetary policy when controlling for the bank’s specific characteristics can be different between the pre-crisis and during the crisis. Salachas et al. (Citation2017) show that due to monetary policy tightening, banks become dependent on their balance sheet’s liquidity as a funding source for bank loan supply and that banks’ dependence is more pronounced in the pre-crisis. Although the 2007–2009 global financial crisis was not identical to the COVID-19 pandemic, the lessons learned can be used to implement adaptive monetary policy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Bhar & Malliaris, Citation2021). There is no evidence of the influence of monetary policy on bank performance and risk under the joint effect of the COVID-19 turmoil period and the strength of banks’ profiles. Inspired by these points, we expect the implications of the bank-specific characteristics on the response of bank risk and performance to monetary policy to be clear when considering the COVID-19 effect.

Figure is designed to illustrate all study links that need to be addressed, as follows:

3. Methodology and data collection

3.1. Econometric model

From the model of Kumar et al. (Citation2020), we propose the specifications as follows:

where refers to performance of bank i at quarterly t, measured by two components such as the return on assets (ROA) and the return on equity (ROE).

denotes the risk of bank i at quarterly t, defined by the standard deviation of ROA (sdROA) and that of ROE (sdROE). These measures capturing bank performance and risk are widely used in the literature on bank performance and risk (Li et al., Citation2021; Rafinda et al., Citation2018; Vo, Citation2020).

Similar to Borio and Gambacorta (Citation2017), the change in overnight interest rate , a monetary policy tool is employed. The increase and decrease in

can be employed to account for contractionary and expansionary monetary policy, respectively (Sanfilippo-Azofra et al., Citation2018). To capture the COVID-19 pandemic, we use the dummy variable CRISIS, which takes the value of 1 in the case of the existence of this pandemic starting from quarterly 1st in 2019 and 0 in the opposite cases. The product term of

is used to compare the existence of the influence of monetary policy on bank performance and risk with and without the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. All variables on the right-hand side of specifications (1) and (2) are lagged one-period in order to eliminate the potential issue of endogeneity (V. D. Dang, Citation2021) and the possible impact of reverse causality (Danisman & Demirel, Citation2019).

The interaction terms such as and

are included to address the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank performance and risk. The significant values of

and

means that the responses of bank performance and risk to monetary policy shocks are dependent on the balance sheet items of banks. The cubic-interactive terms such as

and

are constructed by interacting with each bank’s balance sheet item, the monetary policy instrument, and the CRISIS dummy. These terms may capture changes in the distributional effect of monetary policy under the COVID-19 pandemic crisis.

3.2. Control variable

stands for the bank characteristics (with k = 4, denoting the number of banks’ balance sheet items used in the model), such as the ratio of bank capital to total assets (CAP), the natural logarithm of total assets (SIZE), the ratio of cash and deposits to total assets (LIQ), and the ratio of loan loss provision over gross loan (LLP). To obtain the relative values of proxies for bank-specific characteristics, according to Gambacorta (Citation2005) and Nguyen and Dinh (Citation2022), the independent variables are normalized with their mean values as follows:

where refers to cash and deposits;

is total equity;

is total assets;

, and

stand for the loan loss provisions and total loans, respectively.

is the number of banks in the sample.

From empirical evidence, bank performance is positively affected by bank size (Berger & Mester, Citation2003), liquidity (Pasiouras & Kosmidou, Citation2007), and the level of capital (Athanasoglou et al., Citation2008), and negatively influenced by credit risk (Vu & Nahm, Citation2013). On the contrary, bank risk is positively affected by the ratio of loan loss provision over total assets (Ghenimi et al., Citation2017), and negatively influenced by the bank’s size (Salas & Saurina, Citation2002), liquidity (Ratnovski, Citation2013), and level of capital (Furlong & Keeley, Citation1989).

For controlling the macro-economy and aggregate demand, we include the growth rate of gross domestic product (GDPG), which is primarily employed in the extant literature. GDPG has ambiguous effects on bank performance and risk; it can be significantly negative (Liu & Wilson, Citation2010), positive (Dietrich & Wanzenried, Citation2011), or insignificant (Sharma et al., Citation2013). Similarly, the GDPG–bank risk nexus is inconclusive; for example, this nexus is positive (Fu et al., Citation2014), negative (Saif-Alyousfi et al., Citation2020) or insignificant (Sharma et al., Citation2013). The summary of variable definitions is reported in Table .

Table 1. Variable definitions and sources

3.3. Econometric regression technique

The regression with bank performance and risk as the dependent variables regularly faces the potential endogenous issue caused by the dynamic model of the inclusion of the dependent variable, the reverse relationship, and the variable omission (Wintoki et al., Citation2012). The inclusion of instruments must meet the p-values of the Hansen test, in which the insignificant value of the Hansen test’s p-values shows the validity of instruments. Besides, the Hansen test relates to the overidentification test for the restrictions in the GMM estimator (Ghenimi et al., Citation2017). The AR(1) and AR(2) tests are employed to test the existence of the first-order and second-order serial correlation with the error term, respectively. The differenced error term is allowed to be first-order serial correlation, but the second-order serial correlation with the error term will not qualify the GMM measure assumption. Following the approach of Matousek and Solomon (Citation2018) and Huan (Citation2021), we apply the method of general-to-specific capturing the choice of instruments by employing original instruments from t-1. In total, the use of 27–30 instruments does not exceed 30 (the number of groups), which shows no concern about the outnumber problem of instruments (V. D. Dang & Dang, Citation2021).

3.4. Data collection

This research draws on the final panel data for the 30 Vietnamese commercial banks,Footnote2 making up approximately 90% of market share in terms of the total assets for the case of Vietnam’s banking system, between the first quarter of 2017 and the fourth quarter of 2020, covering the period of the COVID-19 pandemic with the first disease case beginning on 23 January 2020. We exclude banks without having sufficient data. The previous empirical studies in Vietnam mostly employed annual data for bank-specific characteristics. This hand-collected dataset is retrieved from the audited financial statements of commercial banks and obtains a balanced sample of 480 bank-quarterly observations. Following V. D. Dang (Citation2020), we approach the winsorizing process at 2.5% for both tails of observations to avoid the potential impact of outliers.

Table shows the descriptive statistics for all research variables. Concerning bank performance, the mean value of ROA (ROE) is 0.30% (3.71%), which is within the range of −0.75% (−4.68%) to 1.25% (15.82%), with a standard deviation of 0.27% (2.88%). With respect to bank risk, the mean value of sdROA (sdROE) is 0.07% (0.88%), ranging from a minimum value of 0.01% (0.26%) and a maximum value of 0.07 (2.73%). On average, the overnight interest rate as the monetary policy instrument has a mean value of −0.18% with a variation of 1.38%. Therefore, the heterogeneity of a bank’s variables can help to obtain reliable results (V. D. Dang, Citation2020). To sum up, the summary statistics do not show any anomalies in the data sample.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics/

Turning now to Table , the correlation matrix among variables is displayed. It can also be observed that all pairs of variables are highly low, suggesting no severe issue of multicollinearity driving the regression estimation. Due to the high correlations of bank performance (ROA and ROE) with 0.897 and that of bank risk (sdROA and sdROE) with 0.882, they do not enter into the same regression specification to avoid spurious results.

Table 3. Pairwise correlation matrix

4. Empirical findings

4.1. Impact of monetary policy on bank performance conditional on Covid-19 pandemic and bank-specific characteristics

In this subsection, we estimate bank performance and risk as a function of monetary policy shocks, taking into account the bank’s individual characteristics as well as the period of the COVID-19 crisis. The post-estimation testing for the appropriateness of our model is reported through the values of AR(1), AR(2), and the Hansen test. As a result, at the bottom of each table, the significant values of AR(1) and the insignificant values of AR(2) are reported, indicating the presence of first-order correlations and the absence of second-order correlations with the error term. In addition, Hansen tests with insignificant values show the acceptance of the null hypothesis for valid instruments. These tests show that the regression model is right, which makes it easier to draw conclusions from the S-GMM results.

Each model in Table displays several research links discussed previously, as follows: (i) the response of bank performance and risk to monetary policy shocks depending on the COVID-19 crisis; (ii) the impact of monetary policy on bank-specific outcomes such as risk and performance; and (iii) the combined effect of bank-specific characteristics and the COVID-19 pandemic on the response of bank-specific outcomes to monetary policy shocks. Columns (1)–(3) and columns (4)–(6) are the results of ROE and ROA as the dependent variables, respectively, accounting for bank performance. For more details, see columns (2) and (4). They show the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank performance, while columns (3) and (6) present full models to capture the joint effect of bank-specific profiles and the COVID-19 crisis.

Table 4. The impact of monetary policy on bank performance conditional on bank characteristics and Covid-19 pandemic

We obtain some empirical evidence as follows. First, at a normal time, there is a positive link between monetary policy and bank performance across all models, showing the performance-decreasing effect of monetary policy easing in the study sample. However, the coefficients on this link are not significant. The result is consistent with the work of Kumar et al. (Citation2020), who find the positive impact of monetary policy on bank performance. Interestingly, the monetary policy–bank performance relations exist when considering the crisis period of the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting the performance-increasing monetary policy expansion through cutting policy rates under the Covid-19 outbreak. One justification for this result is that despite the SBV’s attempt to recover the economy through monetary policy expansions in response to COVID-19 drawbacks, the bank’s performance has improved due to an increase in the bank’s financing funds. This result is consistent with the case of Vietnam when commercial banks are in a state of money surplus because the risk-averse attitude of depositors caused by the uncertainty of the COVID-19 period can induce them to invest their money in the banking system. Therefore, these banks can enjoy more efficiency in the time of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Second, concerning the interaction terms between bank-specific characteristics and overnight interest rates, we find significant evidence that the impact of monetary policy on bank performance can depend on the bank’s profiles. The impact of monetary policy easing on performance is more pronounced in banks with high capitalization, low credit risk, large size, and less liquidity than in banks with low capitalization, high credit risk, small size, and good liquidity.

Third, considering the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the monetary policy–bank performance nexus, we observe the change in the sign of coefficients on the cubic-interactive terms between Covid-19, the bank’s profile, and monetary policy, compared with the interaction terms. Interestingly, the performance-decreasing impact of monetary policy easing is significantly reliant on the joint effect of bank-specific characteristics and the pandemic crisis. More specifically, the crisis weakens the positive response of bank performance to monetary policy shocks for banks with well-capitalization, low credit risk, large size, and less liquidity, thus decreasing the distributional effect of monetary policy.

Fourth, with respect to control variables, the bank’s size has a positive impact on bank performance, suggesting that larger banks can benefit from economies of scale to enhance their performance (Berger et al., Citation1993). This positive sign is similar to other banks’ balance sheet items. For example, banks with high levels of capital, liquidity, and credit risk lead to high levels of bank performance, which is in accordance with previous studies (Athanasoglou et al., Citation2008; Figlewski et al., Citation2012; Pasiouras & Kosmidou, Citation2007; Saona, Citation2016). The coefficient on the impact of economic development on bank performance is statistically negative, suggesting that the positive prospect of the economy can hamper the bank’s performance. This result can agree with the view that high economic growth boosts the business environment and lowers bank entry barriers, leading to the increased competition dampening the bank’s performance (Liu & Wilson, Citation2010).

4.2. Impact of monetary policy on bank risk conditional on Covid-19 pandemic and bank-specific characteristics

Turning now to bank risk, Table reports the reaction of bank risk to the shocks of monetary policy conditional on bank-specific characteristics and the crisis from the COVID-19 outbreak. Columns (1)–(3) and columns (4)–(6) are the results of sdROE and sdROA as the dependent variables, respectively, accounting for bank risk. For more details, columns (2) and (4) display the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank risk represented in the interaction terms, and columns (3) and (6) capture the joint effect of the bank’s balance sheet items and the COVID-19 crisis on both proxies of bank risk through the cubic-interactive terms. The testing diagnostics at the bottom of each table continue to meet the econometric requirements, i.e., the insignificant values of the Hansen test show the validity of instruments, and the insignificant value of AR (2) indicates the absence of serial correlation with the idiosyncratic disturbances.

Table 5. The impact of monetary policy on bank risk conditional on bank characteristics and Covid-19 pandemic

We observe several empirical results, as follows: First, due to insignificant coefficients for any specification, monetary policy does not have a significant direct effect on bank risk. However, monetary policy expansion can drive the higher risk of banks under the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. This implies the role of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis in the instability-increasing effect of monetary policy loosening, which can create the potential risk of the banking system. Commercial banks have to cope with an increase in unanticipated non-performing loans and operating costs from social distancing requirements. This may affect the potency of monetary policy easing transmitted into banks’ performance.

Second, we find that the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank risk, as captured by interaction terms between bank-specific characteristics and overnight interest rate, is more pronounced for banks with good liquidity, high credit risk, less capitalization, and small size than for counterparts with less liquidity, low credit risk, well capitalization, and large size.

Third, for the cubic-interactive terms among monetary policy, bank characteristics, and the COVID-19 crisis, the finding shows that the impact of monetary policy on bank risk can be contingent on both bank individual characteristics and the outbreak of COVID-19. To be specific, the stability-increasing effect of monetary policy expansion in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak is favorable for banks with low liquidity, low credit risk, and undercapitalization. This result also emphasizes that the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank risk depends on the bank’s balance sheet items and can be weakened by the time of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Fourth, with respect to variables controlling for bank-specific characteristics, size and bank liquidity tend to have a negative impact on bank risk, which is consistent with Boyd and Prescott (Citation1986), Boyd and Prescott (Citation1986), and Ratnovski (Citation2013), respectively. For most specifications, there is an insignificant impact of bank credit risk and bank capital on bank risk. The coefficient on the growth rate of GDP is significantly negative, suggesting that the higher rate of economic growth decreases the risk and boosts banks’ stability (Saif-Alyousfi et al., Citation2020).

4.3. Robustness test

In this section, we perform the robustness test by employing the money market interest rates with different maturities (i.e., VNIBOR1, VNIBOR3, and VNIBOR6), which are reported in Table and Table for the use of bank performance and bank risk, respectively, as the dependent variables. The data for these variables can be collected on SBV’s website. The insignificant value of the Hansen test at the bottom of each table shows the validity of instruments employed in the S-GMM estimator. The correctness of the estimation model is confirmed by the fact that the second-order correlation and Hansen test results are not significant. This means that the regression results can be used to draw conclusions.

Table 6. Robustness test for bank performance model

Table 7. Robustness test for bank risk model

The findings are qualitatively similar to those reported in the previous section. We observe the main results summarized as follows: (i) The monetary policy loosening increases both bank performance and risk under a COVID-19 pandemic crisis; (ii) Balance sheet items show the positive and negative impact on bank performance and risk, respectively; (iii) The responses of bank performance and risk to the change in monetary policy are influenced by the joint effect of the COVID-19 crisis and the bank’s balance sheet items.

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic, with its severe damage, has been considered a “Great Compression” (Harvey, Citation2020), which captures the dramatically wide-scale influence on the worldwide economy (Talbot & Ordonez-Ponce, Citation2020). In response to the serious consequences of this novel pandemic, many countries have initiated adaptive monetary policy to offer monetary recovery for financial markets (Wei & Han, Citation2021). In addition, recent empirical research has focused heavily on the implications of monetary policy surprises on financial markets. We observe that empirical research on how bank performance and risk are affected by monetary shocks depends on the bank’s individual characteristics is rather limited. Furthermore, there is a lack of research on this nexus in the context of the COVID-19 crisis.

This study aims to address these voids by delving into a typical emerging market such as Vietnam by applying the dynamic S-GMM to a sample of comprehensive and representative commercial banks in Vietnam for the period of 2017Q1-2020Q4 covering the COVID-19 pandemic (starting from 2020Q1). We find an increase in bank risk and performance as a result of monetary policy loosening in the period of the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, the impacts of monetary policy shocks on bank performance and risk can vary with different banks’ profiles. However, these effects are weakened by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This shows that COVID-19 has a significant effect on the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank performance and risk when bank-specific factors are different.

Our research differs from previous studies in three dimensions. First, the indirect effect of monetary policy on bank performance and risk can be found in the COVID-19 crisis. Kumar et al. (Citation2020) demonstrate the positive impact of short-term monetary policy. However, the authors were unable to account for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on this nexus. Second, we are among the first to examine how the response of bank performance and risk to the shocks of monetary policy can vary with the difference in bank-specific factors in an emerging market. Third, the distributional effect of monetary policy on bank performance and risk can be attenuated in the event of a crisis driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been ignored in previous studies. For example, Elnahass et al. (Citation2021) show the direct impact of COVID-19 on financial performance and stability and do not consider monetary policy in their model, which is different to our research scenario.

These findings can give rise to careful surveillance of the increase in bank performance and risk driven by monetary policy loosening at the time of the COVID-19 outbreak. Importantly, the impacts of monetary policy on bank risk and performance become more dependent both on bank idiosyncratic characteristics and Covid-19 consequences, thereby drawing the great attention of SBV to adopt an appropriately adaptive monetary policy considering the joint effect of the Covid-19 outbreak and heterogeneity in banks’ profiles.

This research cannot avoid the limitations. First, because our aim is to collect strongly balanced quarterly data, study measures for bank performance and risk may not cover comprehensive aspects of a bank’s performance and risk. Second, while Vietnam has several distinct characteristics of a typical emerging market, these research findings aid in drawing conclusions for the country-specific context. Based on these weaknesses, future research can extend the sample to other countries with identical backgrounds for the sake of results’ representation. In addition, several proxies for the bank’s performance and risk should be included to create a more robust inference of findings in this study. In addition, the unconventional monetary policies pursued by major central banks in response to the instability of the economy are receiving increasing attention (Derbali & Chebbi, Citation2018). Future research can include non-traditional monetary policy instruments into risk and performance models to offer more insights on the monetary policy transmission through bank performance and risk.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Tho Ngoc Tran and Thi Thu Hong Dinh for valuable comments and encouragement. This research is funded by the University of Economic Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam). This study is also a part of the thesis of Ph.D. Candidate Thanh Phuc Nguyen.

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thanh Phuc Nguyen

He is a senior lecturer of School of Banking (University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City). His current research interests include banking & finance, investment, and financial markets.

His research passion revolves around economics, banking & finance. His research interests focus on banking system, publicly listed firms and macroeconomic policy.

She is a senior lecturer of Faculty of Banking and Finance (Van Lang University). Her current research interests include banking & finance, investment, and financial markets.

Notes

1. See more at https://baochinhphu.vn/ngan-hang-nha-nuoc-giam-lai-suat-dieu-hanh-lan-thu-3-trong-nam-102279877.htm

2. These banks consist of ABB, ACB, Bac A Bank, Baovietbank, BIDV, CTG, Eximbank, HDBank, Kienlongbank, LienVietPostBank, MB, MSB, Nam A Bank, NCB, OCB, PG Bank, PvcomBank, Sacombank, Saigonbank, SCB, SeABank, SHB, Techcombank, TPBank, VCB, VIB, Viet Capital Bank, VietABank, Vietbank, and VPBank.

References

- Agenor, R., Alper, K., & da Silva, L. P. (2018). Capital regulation, monetary policy, and financial stability. 32nd Issue (September 2013) of the International Journal of Central Banking.

- Altunbas, Y., Gambacorta, L., & Marques-Ibanez, D. (2010). Bank risk and monetary policy. Journal of Financial Stability, 6(3), 121–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2009.07.001

- Altunbas, Y., Gambacorta, L., & Marques-Ibanez, D. (2012). Do bank characteristics influence the effect of monetary policy on bank risk? Economics Letters, 117(1), 220–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.04.106

- Athanasoglou, P. P., Brissimis, S. N., & Delis, M. D. (2008). Bank-specific, industry-specific and macroeconomic determinants of bank profitability. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 18(2), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2006.07.001

- Berger, A. N., Hunter, W. C., & Timme, S. G. (1993). The efficiency of financial institutions: A review and preview of research past, present and future. Journal of Banking & Finance, 17(2–3), 221–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(93)90030-H

- Berger, A. N., & Mester, L. J. (2003). Explaining the dramatic changes in performance of US banks: Technological change, deregulation, and dynamic changes in competition. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 12(1), 57–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1042-9573(02)00006-2

- Berument, H., & Froyen, R. T. (2015). Monetary policy and interest rates under inflation targeting in Australia and New Zealand. New Zealand Economic Papers, 49(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/00779954.2014.929608

- Bhar, R., & Malliaris, A. G. (2021). Modeling U.S. monetary policy during the global financial crisis and lessons for Covid-19. Journal of Policy Modeling, 43(1), 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2020.07.001

- Bikker, J. A., & Vervliet, T. M. (2018). Bank profitability and risk‐taking under low interest rates. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 23(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1595

- Borio, C., & Gambacorta, L. (2017). Monetary policy and bank lending in a low interest rate environment: Diminishing effectiveness? Journal of Macroeconomics, 54, 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmacro.2017.02.005

- Borio, C., Gambacorta, L., & Hofmann, B. (2017). The influence of monetary policy on bank profitability. International Finance, 20(1), 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/infi.12104

- Borio, C., & Zhu, H. (2012). Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: A missing link in the transmission mechanism? Journal of Financial Stability, 8(4), 236–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2011.12.003

- Boyd, J. H., & Prescott, E. C. (1986). Financial intermediary-coalitions. Journal of Economic Theory, 38(2), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(86)90115-8

- Buch, C. M., Eickmeier, S., & Prieto, E. (2014). In search for yield? Survey-based evidence on bank risk taking. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 43, 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2014.01.017

- Chen, M., Wu, J., Jeon, B. N., & Wang, R. (2017). Monetary policy and bank risk-taking: Evidence from emerging economies. Emerging Markets Review, 31, 116–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2017.04.001

- Dang, V. (2019). The effects of loan growth on bank performance: Evidence from Vietnam. Management Science Letters, 9(6), 899–910. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.2.012

- Dang, V. D. (2020). The conditioning role of performance on the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy: Evidence from a multiple-tool regime. Research in International Business and Finance, 54, 101301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101301

- Dang, V. D. (2021). How do bank characteristics affect the bank liquidity creation channel of monetary policy? Finance Research Letters, 101984.

- Dang, V. D., & Dang, V. C. (2021). Bank diversification and the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission: Evidence from the bank lending channel in Vietnam. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1885204. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1885204

- Danisman, G. O., & Demirel, P. (2019). Bank risk-taking in developed countries: The influence of market power and bank regulations. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 59, 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2018.12.007

- Dell’Ariccia, G., Laeven, L., & Marquez, R. (2014). Real interest rates, leverage, and bank risk-taking. Journal of Economic Theory, 149, 65–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jet.2013.06.002

- Derbali, A., & Chebbi, T. (2018). ECB monetary policy surprises and Euro area sovereign yield spreads. International Journal of Management and Network Economics, 4(2), 177–198. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMNE.2018.095193

- Derbali, A., Jamel, L., Ltaifa, M. B., Elnagar, A. K., & Lamouchi, A. (2020). Fed and ECB: Which is informative in determining the DCC between bitcoin and energy commodities? Journal of Capital Markets Studies, 4(1), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCMS-07-2020-0022

- Derbali, A., Naoui, K., & Jamel, L. (2021). COVID-19 news in USA and in China: Which is suitable in explaining the nexus among Bitcoin and Gold? Pacific Accounting Review, 33(5), 578–595. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-09-2020-0170

- Dietrich, A., & Wanzenried, G. (2011). Determinants of bank profitability before and during the crisis: Evidence from Switzerland. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 21(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2010.11.002

- Elnahass, M., Trinh, V. Q., & Li, T. (2021). Global banking stability in the shadow of Covid-19 outbreak. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 72, 101322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2021.101322

- Figlewski, S., Frydman, H., & Liang, W. (2012). Modeling the effect of macroeconomic factors on corporate default and credit rating transitions. International Review of Economics & Finance, 21(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2011.05.004

- Fu, X. (., Lin, Y. (., & Molyneux, P. (2014). Bank competition and financial stability in Asia Pacific. Journal of Banking & Finance, 38, 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.09.012

- Furlong, F. T., & Keeley, M. C. (1989). Capital regulation and bank risk-taking: A note. Journal of Banking & Finance, 13(6), 883–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(89)90008-3

- Gambacorta, L. (2005). Inside the bank lending channel. European Economic Review, 49(7), 1737–1759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.05.004

- Gambacorta, L., & Marques-Ibanez, D. (2011). The bank lending channel: Lessons from the crisis. Economic Policy, 26(66), 135–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00261.x

- Ghenimi, A., Chaibi, H., & Omri, M. A. B. (2017). The effects of liquidity risk and credit risk on bank stability: Evidence from the MENA region. Borsa Istanbul Review, 17(4), 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2017.05.002

- Hancock, D. (1985). Bank profitability, interest rates, and monetary policy. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 17(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.2307/1992333

- Harvey, A. (2020). The economic and financial implications of COVID-19 (3rd April, 2020), the mayo center for asset management at the university of Virginia Darden school of business and the financial management association international virtual seminars series. In.

- Heider, F., Saidi, F., & Schepens, G. (2019). Life below zero: Bank lending under negative policy rates. The Review of Financial Studies, 32(10), 3728–3761. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz016

- Heryán, T., & Tzeremes, P. G. (2017). The bank lending channel of monetary policy in EU countries during the global financial crisis. Economic Modelling, 67, 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.07.017

- Huan, N. H. (2021). Market structure, state ownership and monetary policy transmission through bank lending channel: Evidence from Vietnamese commercial banks. 739898418.

- Jiménez, G., Ongena, S., Peydró, J. L., & Saurina, J. (2014). Hazardous times for monetary policy: What do twenty‐three million bank loans say about the effects of monetary policy on credit risk‐taking? Econometrica, 82(2), 463–505.

- Kashyap, A. K., & Stein, J. C. (2000). What do a million observations on banks say about the transmission of monetary policy? American Economic Review, 90(3), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.3.407

- Khalfaoui, H., & Derbali, A. (2021). Money creation process, banking performance and economic policy uncertainty: Evidence from Tunisian listed banks. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(8), 1175–1190. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-12-2020-0784

- Kishan, R. P., & Opiela, T. P. (2000). Bank size, bank capital, and the bank lending channel. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 32(1), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.2307/2601095

- Kumar, V., Acharya, S., & Ho, L. T. (2020). Does monetary policy influence the profitability of banks in New Zealand? International Journal of Financial Studies, 8(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs8020035

- Li, X., Feng, H., Zhao, S., & Carter, D. A. (2021). The effect of revenue diversification on bank profitability and risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters, 101957.

- Liu, H., & Wilson, J. O. (2010). The profitability of banks in Japan. Applied Financial Economics, 20(24), 1851–1866. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603107.2010.526577

- Matousek, R., & Solomon, H. (2018). Bank lending channel and monetary policy in Nigeria. Research in International Business and Finance, 45, 467–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.07.180

- Matthys, T., Meuleman, E., & Vander Vennet, R. (2020). Unconventional monetary policy and bank risk taking. Journal of International Money and Finance, 109, 102233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2020.102233

- NEU, & JICA. (2020). Assessment of policies to cope with Covid-19 and recommendations. Retrieved from

- Nguyen, T. P., & Dinh, T. T. H. (2022). The role of bank capital on the bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission: An application of marginal analysis approach. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2035044. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2035044

- Odonkor, T. A., Osei, K. A., Abor, J., & Adjasi, C. K. (2011). Bank risk and performance in Ghana. International Journal of Financial Services Management, 5(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJFSM.2011.041919

- Pasiouras, F., & Kosmidou, K. (2007). Factors influencing the profitability of domestic and foreign commercial banks in the European Union. Research in International Business and Finance, 21(2), 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2006.03.007

- Pinshi, C. (2020). COVID-19 uncertainty and monetary policy.

- Rafinda, A., Rafinda, A., Witiastuti, R. S., Suroso, A., & Trinugroho, I. (2018). Board diversity, risk and sustainability of bank performance: Evidence from India. Journal of Security & Sustainability Issues, 7(4), 793–806. https://doi.org/10.9770/jssi.2018.7.4(15)

- Ratnovski, L. (2013). Liquidity and transparency in bank risk management. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 22(3), 422–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2013.01.002

- Saif-Alyousfi, A. Y. H., Saha, A., & Md-Rus, R. (2020). The impact of bank competition and concentration on bank risk-taking behavior and stability: Evidence from GCC countries. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 51, 100867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2018.10.015

- Salachas, E. N., Laopodis, N. T., & Kouretas, G. P. (2017). The bank-lending channel and monetary policy during pre-and post-2007 crisis. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 47, 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2016.10.003

- Salas, V., & Saurina, J. (2002). Credit risk in two institutional regimes: Spanish commercial and savings banks. Journal of Financial Services Research, 22(3), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019781109676

- Sanfilippo-Azofra, S., Torre-Olmo, B., Cantero-Saiz, M., & López-Gutiérrez, C. (2018). Financial development and the bank lending channel in developing countries. Journal of Macroeconomics, 55, 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmacro.2017.10.009

- Saona, P. (2016). Intra-and extra-bank determinants of Latin American Banks’ profitability. International Review of Economics & Finance, 45, 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2016.06.004

- Sharma, P., Gounder, N., & Xiang, D. (2013). Foreign banks, profits, market power and efficiency in PICs: Some evidence from Fiji. Applied Financial Economics, 23(22), 1733–1744. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603107.2013.848026

- Talbot, D., & Ordonez-Ponce, E. (2020). Canadian banks’ responses to COVID-19: A strategic positioning analysis. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 1–8.

- Vo, X. V. (2020). The role of bank funding diversity: Evidence from Vietnam. International Review of Finance, 20(2), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/irfi.12215

- Vu, H., & Nahm, D. (2013). The determinants of profit efficiency of banks in Vietnam. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 18(4), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2013.803847

- Wei, X., & Han, L. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on transmission of monetary policy to financial markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 74, 101705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101705

- Wintoki, M. B., Linck, J. S., & Netter, J. M. (2012). Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 105(3), 581–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.03.005

- Wu, S., Tong, M., Yang, Z., & Derbali, A. (2019). Does gold or Bitcoin hedge economic policy uncertainty? Finance Research Letters, 31, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.04.001

- Yilmazkuday, H. (2021). COVID-19 and exchange rates: Spillover effects of us monetary policy. Available at SSRN, 3603642.