Abstract

With a young population structure, young consumers in Vietnam have been becoming a driving force and a major purchasing power behind the economic development. While ethical issues associated with consumerism have been a topic of discussion in the society, young consumers have stepped up to the plate by showing a positive support for being ethical consumers. It is still unclear, however, whether they are willing to actualize their perspective, as the alleged attitude—behavior gap is still commonplace. This research attempted to examine the influence of socialization agents and environmental concern on the ethically minded consumer behavior (EMCB) of young consumers by drawing on the socialization framework. The context of this research is Generation Z in Vietnam, the generation who has been growing up with technology but has been received lack investigation. With a sampling of 230 young consumers based in Ho Chi Minh City, results demonstrate that intimate relationships have a significant impact on young consumers’ behavior towards dimensions of EMCB. In particular, family and peers exert substantial effect on young consumers’ tendency to pay more for an ethical product as well as to purchase eco-friendly goods. Media, on the contrary, is not a significant determinant.

1. Introduction

Research on ethical or responsible consumption has increased in the last decade as businesses began to understand the impact on consumer choices (Vitell, Citation2009). Coupled with environmental concern when people are more educated and public conscious, responsible consumption has been under the spotlight, across cultures (Belk et al., Citation2005). Young people, meanwhile, are known for their strong environmental consciousness, in which they show attentive care and interest on issues of living environment (Flurry & Swimberghe, Citation2016; Lee, Citation2008). However, there is lack of research on responsible consumption of young generation (Flurry & Swimberghe, Citation2016; Muralidharan & Xue, Citation2016), especially almost no research on Generation Z.

Generation Z refers to the group of youths born around 1995, and this is the first generation of children having access to a wide scale of digital communication (Bassiouni & Hackley, Citation2014). Thus, they would be the important consuming power in the near future, as they could also influence other age segments. Growing up in the era of social media (Mangold & Smith, Citation2012), Generation Z have been influenced by the environmental campaigns and social activities supporting social corporate responsibility (CSR) of companies. Therefore, understanding the influence of people around such group of young consumers is very important to understand the attitude and ethically minded behavior (Lee, Citation2008).

This research aims to investigate the social structural variables as consumer profiles (i.e. gender, age, education and family structure), socialization agents (i.e. family, peers and media) and environmental attitude on the responsible consumption of Generation Z. People from this generation clearly have an ethically minded attitude towards what should be purchased and consumed, but most of them have failed to actualize their pro-environment attitude, meaning that they are hesitant to make ethical choice (Gaudelli, Citation2009). As the translation from ethical mind to responsible consumption needs to further examined (Muralidharan & Xue, Citation2016). In the present study, the ethically minded consumer behavior from Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (Citation2016) was applied as the measurement for the sustainable consumption.

Lack of research on ethical or responsible consumption has been conducted in Asian emerging markets (Arli & Pekerti, Citation2017). Vietnam is an emerging economy with a young and growing population, in which the middle class is increasingly adopting sustainable lifestyles (De Koning et al., Citation2015). Vietnam has entered the 21st century with a young population structure. The total amount of population under labor force age is approximately 81 million, accounting for nearly 84% of the entire population. Therefore, young consumers are the major target of most businesses. As standards of living are improved, Generation Z would potentially become wealthier compared to their parent generations. They now have more purchasing power than ever and also a remarkable source of influence on their friends and family (Flurry & Swimberghe, Citation2016).

2. Literature review

2.1. Consumer Ethics Scale (CES)

Consumer ethics has long been under examination by numerous researchers and scholars. Muncy and Vitell, meanwhile, are among the most prevalent active in this area. First introduced late in the 1990s (see, Muncy & Vitell, Citation1992; Vitell & Muncy, Citation1992), the consumer ethics scale had been gradually modified to adapt the new era of consumerism. The modified scale (Vitell & Muncy, Citation2005) comprises seven items, namely active/illegal, passive/illegal, questionable/legal, no harm, downloading, recycling and do good. The specific definitions and items are as followed: active/illegal (actively benefiting from illegal activities; passive/illegal) (passively benefiting); questionable/legal (actively benefiting from deceptive or questionable, but legal practices); no harm (no harm, no foul activities); downloading (downloading copyrighted materials, buying counterfeit goods); recycling (recycling, environmental awareness); do good (doing the right thing).

These studies have widely adopted from other researchers in the field, for they provide primary conceptual frameworks to decode consumer ethics (Lu & Lu, Citation2010). Controversies, however, still exist on the grounds that this scale is focused merely on the attitude facet of consumer (Le & Kieu, Citation2019). It provides immaculate description into how consumers are presented upon an ethical dilemma and how they reason to judge the situation, whereas no information of actual behavior is existent (Shaw et al., Citation2005). This attitude—behavior gap challenges any attempt to interpret consumer behaviors. Moreover, evidence shows that there is validity failure when it comes to cross-cultural reasoning process (Polonsky et al., Citation2001). Consumers in Austria, for instance, find it less intolerant regarding questionable behaviors (Rawwas, Citation1996). Even some CES dimensions were discovered to result in ambiguous answers, since there is not a logical reasoning consistency across different cultures (Vitell et al., Citation2016).

2.2. Ethically Minded Consumer Behavior (EMCB)

Consumer ethics research has recently begun to take precedence over business ethics research, for the most part. There is a perception that consumer ethics assessment scales do not exist as frequently as those for business decisions. It is common for ethical studies to focus on environmental issues rather than larger social concerns. Environmental and social issues are still lacking in scales for ethical consumption. Researchers need an instrument to use in future studies to establish the various underlying reasons and antecedents for ethical buying, as well as uncover and assess the barriers to such purchasing. This new scale addresses a void that focuses on real action instead of intentions or attitudes. (Sudbury-Riley & Kohlbacher, Citation2016)

Regarding the fact that the attitude-behavior gap is still extensively problematic, new measurement instruments were introduced to measure and explain consumer choices associated with environmental issues. The ethically minded consumer behavior (Sudbury-Riley & Kohlbacher, Citation2016) serves as a new scale that is composed of five dimensions of consumer making decision. It views consumer ethical making decision as a continuum, where there would be a segment of consumers who continuously strive to purchase ethically, while others do not (Le & Kieu, Citation2019). Details of EMCB scale are five dimensions as follows: Ecobuy (the deliberate selection of environmentally friendly products over their less friendly alternatives), Ecoboycott (refusal to purchase a product based on environmental issues), Recycle (specific recycling issues), CSRBoycott (refusal to purchase a product based on social issues), and Paymore (a willingness to pay more for an ethical product) (Sudbury-Riley & Kohlbacher, Citation2016).

Served as an endeavor to measure actual purchasing behavior, EMCB scale made marked progress in questioning authentic decisions, given the fact that attitude is hardly converted into ethical actions (Carrington et al., Citation2010). This new measurement scale, having proved itself as a valid framework across different cultures and nations, provides a crucial, reliable and easy-to-administer instrument pertaining to ethically minded consumer behavior.

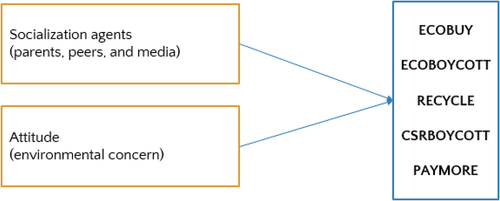

2.3. Consumer socialization framework

Consumer socialization is the process by which young consumers obtain skills, knowledge, and attitudes as they are forming the behavior to be a mature consumer in the market. To be more specific, socialization occurs when young consumers, throughout their cognitive and social development to adulthood, are influenced by the surrounding environment, in terms of norms, attitudes, and behaviors (Moschis & Churchill, Citation1978). In studying the effect of socialization agents (family and peers), Muralidharan and Xue (Citation2016) examined how social variables and structural agents elicit impact on young consumer green buying behavior, on the grounds that young consumers (millennial, in this case) are increasingly dominating purchasing power and market share. They vale the significant influence of word-of-mouth reference rather than mass media, coupled with attitude (as environmental concern). Social structural variables (age, gender, education, and family structure), socialization agents (peers, parents, and media advertising), and attitude (environmental concern) were explored whether they have impact on green buying behavior of young consumers. All these aspects were thoroughly measured and explained, thereby providing sufficiently fundamental theoretical framework to form new hypotheses. Applying for the context of Generation Z for this study, the socialization agents and social structural variables were examined to test those impacts on the dimensions of ethically minded consumer behavior. The research model and hypotheses were presented in as follows:

H1: Family will positively impact the dimensions of EMCB in young consumers: (a) Ecobuy, (b) Ecoboycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSRBoycott and (e) Paymore.

H2: Peer will positively impact the dimensions of EMCB in young consumers: (a) Ecobuy, (b) Ecoboycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSRBoycott and (e) Paymore.

H3: Exposure to mass media will positively impact the dimensions of EMCB in young consumers: (a) Ecobuy, (b) Ecoboycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSRBoycott and (e) Paymore.

H4: Environmental concern will positively impact the dimensions of EMCB in young consumers: (a) Ecobuy, (b) Ecoboycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSRBoycott and (e) Paymore.

Furthermore, with a view to testing whether differences of gender, family structure and family income exert any impact of each dimension of EMCB, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: There is difference among genders, family structures, and family income with respect to each dimension of EMCB in young consumers: (a) Ecobuy, (b) Ecoboycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSRBoycott and (e) Paymore.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection method

As examining the EMCB, the survey method was utilized in this research. The survey in questionnaire form was delivered to the students by email. An email survey was created by Google and sent out to students by email. Students answered the questionnaire by filling in the email survey and the results were collected. The respondents are the students from Vietnam National University in Ho Chi Minh City, one of two national universities in Vietnam, which has more than 60 thousand students with various majors. The participants were asked to share the questionnaires with their friends to spread the survey.

Respondents were chosen at random using a convenient sampling procedure that ensured their identity was protected. There was a total of 436 participants that participated in data gathering. After data collection and cleaning, 230 valid and full questionnaires were returned, resulting in an overall response rate of 52.75%. There were additional personal and ethical issues in the survey. Therefore, a medium response rate was predicted.

3.2. Measures

Questionnaires consist of two main parts. The first part gives details of EMCB scales, socialization agents, and attitude, while the latter seeks to explore demographic attributes. Five-point Likert scale was employed mostly in the first part, with one exception being questions surrounding attitude, where a five-point semantic differential scale was applied. Five choices were available, ranging from either strongly disagree to strongly agree, or always true to never true, and very frequently to very infrequently.

The EMCB scale includes 10 items, adapted from the work of Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (Citation2016). Responses vary from (1) Never true, (2) Rarely true, (3) Sometimes true, (4) Mostly true, and (5) Always true. Family and peer influences on young consumers’ behavior were measured using the scale borrowed from Muralidharan and Xue (Citation2016), and Lueg and Finney (Citation2007). Respondents were asked to rate their answers on a five-choice questionnaire. Responses range from (1) Strongly disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Neither agree nor disagree, (4) Agree, to (5) Strongly agree. Exposure to media was measured based on a scale consisting of two items. Each item reflects the frequency that consumers are exposed to different modes of media. Participants were required to rank their responses on a frequency scale, varying from (1) Very infrequently, (2) Infrequently, (3) Occasionally, (4) Frequently, to (5) Very frequently. Attitude (environmental concern) was measured using a five-point semantic differential scale containing five items (Mohr et al., Citation1998), with responses ranging from (1) Of little concern, to (5) Of great concern; (1) Uninvolving, to (5) Involving; (1) Not personally relevant, to (5) Personally relevant; (1) Unimportant, to (5) Important; (1) Does not really matter to me, to (5) Really matters to me. All measurement items are presented in . Social structural variables were recorded by asking participants to provide their demographic details, including age, gender, education level, family structure, and family income.

4. Results

4.1. Sample profile

The demographic information of sample includes age, gender, education level, family structure, and family income. The details are as illustrated in . As the target sample was young consumers, the majority of respondents falls between 18 and 24 years of age, accounting for nearly 96%. They are people born from 1995 to 2000, who are of the Generation Z (Bassiouni & Hackley, Citation2014). This corresponds to the proportion of university students, making up 96.5% in the education level criterion. There is a striking disparity in gender, however, in which almost 64% of all participants were female. Approximately half that number were male respondents, namely 33.9%. In terms of family structure, most respondents are living with parents and grandparents, with 69.1% staying with parents and 24.3% staying with both parents and grandparents. A 5.2% of all participants are living with either father or mother, while a tiny 0.9% are with grandparents only. Regarding family income, a significant proportion of the sample was reported to earn under 10 million VND per month, namely 38.7%. The middle-income households (between 10 and 40 million VND) make up a total of 45.2%, while upper-income families are responsible for merely 16.1% of all respondents, who make more than 40 million VND per month. It is noteworthy at this moment that the number refers to the total family earnings, which is explicable due to the fact that most people in Generation Z are still with their parents. Furthermore, this result is interesting since there was a considerably even distribution among family income, even though lower-income families are still a big part in the economy. It can also be seen that the upper-social class now carry more weight in income distribution, meaning that the super-wealthy people are becoming much richer and richer.

Table 1. Source of hypothesis

Table 2. Sample profile

4.2. Descriptive and reliability analysis

Descriptive statistics is put into practice in an attempt to examine, condense and describe the obtained data. Descriptive statistics would be of great use on condition that there is a desire to form some generalizations about the data. In this section, the valid sample of 230 was selected conduct descriptive statistics on the factors that affect ethically minded consumer behavior of young consumers.

Family: Descriptive statistics of the family-dimension refers to how much agreement consumers show toward the seven statements. The average mean value at 3.74 indicates that respondents agree with this dimension to a considerable extent. The fact that the standard deviation was 0.931 on average also shows that there exists a significant similarity among consumers’ perspectives pertaining to all 7 statements. The highest mean reported was 3.91 (Family5). This means that, “My family are aware of ethical consumtion” (Family5) is one element that yields the biggest impact in among the family dimension. The elements of “My family consume ethically” (Family6) and “I talk with my family about ethical consumption” (Family1) can also be seen as effective components due to high mean values at 3.83 and 3.77, respectively. In contrast, “I seek out the advice of my family regarding which consumtion behavior is ethical” (Family4) is not regarded positive by most respondents.

Peer: In terms of descriptive statistics of peer pressure, responses imply the degree of agreement of consumers with their counterparts regarding purchasing behavior. The average mean value at 3.69 suggests that survey takers somewhat have the same supportive opinion with this dimension. In particular, “My peers are aware of ethical consumption” (Peer5) stands out having the highest mean value at 3.86, meaning that it is more influential than any other items in the scale. “I talk with my peers about ethical consumption” (Peer1) and “My peers and I tell each other which consumption behavior is ethical” (Peer3) are second to most impactful items, with both mean values reaching 3.77. In stark contrast, “I seek out the advice of my peers regarding which consumption behavior is ethical” (Peer4) has both the lowest mean value and the highest standard deviation, at 3.50 and 1.018, respectively. This implies that there is a significant variation in respondents’ viewpoints, most of which show negative support to this item. Hence, we can make a rough assumption at this point in which even though peers have influence on their counterpart’s opinion, they do not consult each other on a regular basis, and make the decision themselves instead.

Media: Regarding Media, there is a total of two items, with average mean value being 4.48. This result suggests that the majority of respondents have extremely frequent access to the media. Between the two items, “How often do you use social network?” (Media1) has the highest mean value, at 4.60, indicating that nearly all survey takers have exceedingly high frequency in using social network. The corresponding standard deviation of this item is merely 0.609, which also strengthens the similarity in respondents’ opinion.

Attitude: The Attitude-dimension uses a differential semantic scale, differing from all other dimensions. The overall mean value at 4.16 indicates a significant positive relationship between respondents and each item, with the standard deviation 0.797 implying a high consensus among respondents. Particularly when asked whether “The solid waste or the garbage problem” is important or not (Attitude4), most participants were reported a notable mean value of 4.42, which means almost all of them acknowledged the crucial importance of this issue.

Ethically Minded Consumer Behavior: The dependent variable EMCB measures the extent to which consumers make thoughtful purchasing decision regarding five dimensions of the ethically minded consumer behavior. The average mean value at 3.95 is indicative of a high agreement of survey takers with each item. Correspondingly, the average standard deviation at 0.944 signifies a minute difference among respondents’ point of view. Among each item, “I do not buy products from companies that I know use sweatshop labor, child labor, or other poor working conditions” (EMCB8) generates the highest mean value at 4.38, with relating standard deviation arriving at 0.949. This shows that consumers are very well aware of labor abuse practice, and they are willing to boycott products from these enterprises. Conversely, “I do not buy household products that harm the environment” has the lowest mean value at 3.61, meaning that respondents do not think highly of this item, mostly to a neutral extent. This may be due to the young demographics of respondents, most of whom are not yet responsible for providing household appliances.

To assess the inner-consistency of different factors of the construct, reliability and then factor analyses were taken into practice. In the research model, factor analysis plays a big part in minimizing the quantity of variables and pinpoints the in-need constructs. Interrelation reliability, or “internal consistency” inspects the extent to which a multi-component dimension in actual fact points to a single notion or phenomenon, and that each and every of component of this dimension has a correlation with each other (Bryman & Cramer, Citation1990). As a commonly used method, Cronbach’s alpha measurement scale decides whether a dimension is fit within itself. Computed results are shown in . As a rule of thumb, the lower acceptable limit for Cronbach’s alpha is 0.7, despite the fact that the estimate may go down to 0.6 in exploratory research (Mallery & George, Citation2003). Performed by SPSS, all items within every construct have the values as follows: Family (seven items, alpha = 0.914); Peer (seven items, alpha = 0.916); Media (two items, alpha = 0.717); Attitude (five items, alpha = 0.878); EMCB (10 items, alpha = 0.812). Therefore, all items were kept unchanged for further analyses.

4.3. Exploratory factor analysis

Factor analysis is a universally practiced analyzing method that is most often conducted in social sciences as well as education and psychology. The main objective of factor analysis is to scale down a large quantity of variables into a smaller set of so-called factors. These factors encompass the fundamental underlying notions in those variables, providing self-reporting scales with construct validity substantiation.

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure (KMO) is a standardized limit that is widely used to evaluate the appropriateness of EFA. An estimate ranging from 0.5≤ KMO≤ 1 is considered an acceptable variable. Bartlett’s Test, meanwhile, seeks to investigate whether there is any interrelation among observed variables (the null hypothesis H0). H0 is rebutted if sig. value is smaller than 0.05, indicating that those variables are statistically correlated (Hoàng & Chu, Citation2008). Varimax rotation was applied at the same time to finalize the expected result.

Hair et al. (Citation2006) pointed out that in order to successfully validate the pragmatic meaning of EFA, factor loading is advised to come in place. A value of factor loading greater than 0.3 signifies a minimum acceptable level, while it is seen as significant if the value is larger than 0.4, and more importantly if factor loading is over 0.5, it is indicative of a high significance (Hair et al., Citation2006). Items would be removed due to their low loadings (<0.500) and cross-factor loadings. The exploratory factor analysis was processed for independent variables and then dependent variables.

EFA for Independent Variables: Test runs for independent variables resulted in Bartlett's Test significance level lower than 0.05, and KMO value at 0.891 which is greater than 0.06. Both values are positively satisfactory. From , we can observe that three factors explain a cumulative 68.67% of the variability in the original 21 items, therefore we can considerably reduce the complexity of the data set by using these components. From the Rotated Component Matrix, all observation variables are narrowed down into four factors, whose factor loadings are all larger than 0.6. The loaded factors are named Family, Peer, Attitude, and Media, respectively.

Table 3. Descriptive and reliability analysis

EFA for Dependent Variables: Test runs for dependent variables resulted in Bartlett's Test significance level lower than 0.05, and KMO value at 0.778 which is greater than 0.06. Both values are positively supportive.

Results from show that three new factors were created from the original 10 observation variables. In theory, as adapted from Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (Citation2016), there are five major strands of EMCB, labeled Ecobuy, Ecoboycott, Recycle, CSRBoycott and Paymore. Exploratory factor analysis in this study, however, revealed three factors only, in that EMCB5, EMCB6, EMCB9, and EMCB10 (originally labeled Recycle and Paymore) now merged into one factor; EMCB1, EMCB2, EMCB3, and EMCB4 (originally labeled Ecobuy and Ecoboycott) were combined; only EMCB7 and EMCB8 (originally labeled CSRBoycott) remained unchanged. Based upon previous contradictory results, it is vital that a new measurement scale be established that contains only three dimensions, as shown in .

Table 4. Rotated component matrix for independent variables

Table 5. Rotated component matrix for dependent variables

This study attempts to bring together five original dimensions into three. It is worth noticing that the CSRBoycott-dimension was kept unchanged owing to the support from the test result. As Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (Citation2016) put it, Ecobuy is “The deliberate selection of environmentally friendly products over their less friendly alternatives”, while Ecoboycott is defined as “Refusal to purchase a product based on environmental issues”. The common element of these two is that both make every effort to make purchasing decision in an eco-friendly way. They both come down to making a pro-environmental conscious ethical choice. Consequently, it would be a logical inference that we coalesce both into one dimension hereafter named Eco. Henceforth, Eco encompasses a broad concept of not only choosing an eco-friendly product over less eco-friendly ones, but also declining to purchase non-eco-friendly goods.

Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (Citation2016) also pointed out that Recycle includes “Specific recycling issues”, and Paymore takes account of “A willingness to pay more for an ethical product”. Scratching only the surface of a hypothetically subjective correlation between these two dimensions brings about a vague conclusion. A connection, if existent, would be weak and need more supportive evidence. Nevertheless, in reality, an attempt to buy recycled and reusable products often entails extra costs. For instance, customers would be required to pay a certain amount of money if they wish to buy a reusable container made from recycled materials, unless they are satisfied to use the infamous plastic bags for goods packaging. In implementing this action, they present both sides of paying more for a product and a positive tendency towards recycled products. For this reason, it is rational to fuse both of these two dimensions into one single component, hereafter named Paymore.

At this point, it is reasonable to review the proposed hypotheses previously mentioned, as there have been changes to dependent variables. Hence, new hypotheses are proposed as follows:

H1: Family will positively impact the dimensions of adjusted EMCB in young consumers: (a) Eco, (b) CSRBoycott, and (c) Paymore.

H2: Peer will positively impact the dimensions of adjusted EMCB in young consumers: (a) Eco, (b) CSRBoycott, and (c) Paymore.

H3: Exposure to media will positively impact the dimensions of adjusted EMCB in young consumers: (a) Eco, (b) CSRBoycott, and (c) Paymore.

H4: Environmental concern will positively impact the dimensions of adjusted EMCB in young consumers: (a) Eco, (b) CSRBoycott, and (c) Paymore.

H5: There is difference among genders, family structures, and family income with respect to each dimension of EMCB in young consumers: (a) Eco, (b) CSRBoycott, and (c) Paymore.

4.4. Regression analyses

SPSS statistical software was used to examine whether there is any regression relationship between independent variables (family, peer pressure, media, and attitude) and dependent variables (ethically minded consumer behavior). Each dimension of the EMCB scale was the dependent variable. All four independent factors showed considerable significance to help interpret three dimensions of EMCB, with the highest adjusted R square being 19.9%. A summary of regression results is presented in .

Table 6. Revised EMCB scale

Eco: Regression results with Eco being dependent variable showed that Generation Z behavior towards Ecobuy and Ecoboycott is positively influenced by socialization agents (except for Media), but not Attitude. Standardized Betas for Family and Peers were .242 and .355, respectively, with corresponding t-values standing at 4.058 and 5.958. Therefore, H1a and H2a were supported, while H3a and H4a were not supported. This means that parents and friends have substantial impact on young consumers’ ethical purchasing behavior. Meanwhile, it is fairly clear that media and personal attitude (environmental concern) elicit no effect. A propositioned regression function is illustrated as follows:

Eco = .242*Family + .355*Peer

CSRBoycott: Family, media and attitude were significant positive predictors of the CSRBoycott- dimension, whilst peer was not significant. Coefficients for each factor were .178, .182 and .142 respectively. In addition, t-values were 2.789, 2.853 and 2.219 in that same order, indicating a significant relationship. As a result, whereas H1b, H3b and H4b were confirmed, H2b was not supported. Hence, young consumers’ tendency to refuse to purchase a product based on ethical and environmental issues is influenced by family members, media and their attitudes themselves, but not by their friends. This outcome came as an extreme surprise as it denied the influential contribution of consumers’ peers. In every respect, even though there existed a regression relation related to the CSRBoycott-dimension, the output R square value was fairly small (.069), indicating a weak correlation. Therefore, this relation is hardly explicable and applicable. Nevertheless, below is a propositioned regression function:

CSRBoycott = .178*Family + .182*Media + .142*Attitude

Paymore: Peer was a significant determinant of the last dimension of EMCB—Paymore. Additionally, parents and the consumers’ own attitude also have impact on their decision to pay more for an ethical product even they have other cheaper options. By contrast, media was not significant. Regression results presented Beta values for family, peer and attitude as .189, .348 and .159, with t-values being 3.113, 5.778 and 2.645, respectively. Consequently, H1c, H2c and H4c were supported, while H3c was not supported. A propositioned regression function is illustrated as follows:

Paymore = .189*Family + .348*Peer + .159*Attitude

4.5. Independent—samples T-test and one-way ANOVA

T-test is a popular test employed to compare means of two variables or two different groups (Polit & Beck, Citation2010). Hypothesis testing in conducting t-test implies that there is no variation between the two groups (Williams & Monge, Citation2001). To test our hypotheses of whether there is any similarity between different genders and different family structures, independent—samples t-test was processed. One-way ANOVA, introduced by Ronald Fisher in 1918, is a statistical test to examine whether there exists any difference in means of typically two or more groups or variables. Since there are more than two variables in family income, One-way ANOVA was conducted to test whether different levels of family income influence young consumers’ perception towards each dimension of EMCB. SPSS statistical software was used once again to examine whether there is any difference in means between gender and family structure towards each dimension of adjusted EMCB. Results are summarized in .

Table 7. Regression analyses

Table 8. Independent samples test

Regarding difference in gender, Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances all showed values of sig. above .05, therefore we would use t-test when equal variances assumed. Subsequently, the CSRBoycott is the only value which is closed to the threshold 0.05, indicating that there is no difference in gender with regard to Eco and Paymore, but a lightly different between male and female regarding CSRBoycott, at the significance level of 0.1.

Regarding difference in family structure, only extended and nuclear families were chosen to implement t-test, since the majority of respondents falls into these two types of family. Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances all showed values of sig. above .05, except for the CSRBoycott-dimension. Therefore, we would use t-test when equal variances assumed for the Eco-dimension and Paymore-dimension, and equal variances not assumed for the CSRBoycott-dimension. As a consequence, all sig. values were over .05, suggesting that there is no difference in family structure towards three dimensions of EMCB.

For the ANOVA test, as for Test of Homogeneity of Variances, Levene Statistic values were all larger than .05, which means that ANOVA table would be employed in the next step. It can be clearly seen that all sig. values were much larger than .05. Hence, we have sufficiently statistical evidence to infer that there is no distinction regarding each dimension of EMCB among different family income levels.

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. Hypotheses results

This study aims to explore and comprehend the impact of socialization agents and attitude on each and every dimension of the ethically minded consumer behavior scale with Generation Z in Vietnam. With an increasingly mushrooming purchasing power, Generation Z is the driving force behind any social changes towards a more ethical or responsible consumption habit. Therefore, apart from explaining how young consumers reason and behave in actuality, this study suggested if consumers would manage to translate their positive attitude into actual ethical behavior. Results subsequently demonstrate that both socialization agents and attitude, to a certain extent, exert considerable influence on three adjusted dimensions of EMCB. Findings in this study not only confirmed previous empirical researches but also pointed out surprising implications for further research.

The study found that young people’s adjusted EMCB is positively influenced by their families. A similar conclusion can be drawn from the findings of Muralidharan and Xue (Citation2016) and Lueg and Finney (Citation2007). According to Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (Citation2016), peer influences just green purchasing behavior among millennials, however in this study, peer also influences the “paymore” elements of adjusted EMCB. In this study, exposure to media has a positive effect on EMCB’s CSRBoycott dimension but has no effect on the Eco or Paymore dimensions. This finding is only partially in line with that of the Muralidharan and Xue (Citation2016), Hindol (Citation2012), and Ankit and Mayur (Citation2013). Two dimensions of the adjusted EMCB are positively impacted by environmental concerns. This finding is nearly in agreement with those of Mohr et al. (Citation1998), as well as Muralidharan and Xue (Citation2016). Finally, there is no difference in gender, family structure, or family income when it comes to each dimension of EMCB, contrary to the findings of Witkowski and Reddy (Citation2010), Delistavrou et al. (Citation2017). A summary of hypotheses results is presented in .

Table 9. Independent samples test

Table 10. ANOVA results

Independent—samples T test and one-way ANOVA results demonstrate that there is no clear disparity between different genders, family structures and family income levels concerning their impact on each dimension of EMCB, except the relationship of gender and CSRBoycott with a low significant value. Hence, it can be concluded that male and female young consumers have similar opinion on ethical consumption, instead of the boycott activities as female might be more emotional and concerned about the CSR of the companies. Furthermore, whether it is a nuclear or extended family, and regardless of the richness of their household, consumers’ perspective on EMCB brings about almost no variations. The summary of hypotheses results is presented in .

Table 11. Summary of hypotheses results

5.2. Conclusion

The socialization framework was used in this study to explore the influence of socialization agents and environmental concerns on the ethically minded consumer behavior (EMCB) of young consumers. Generation Z in Vietnam is the focus of this study, a generation that has grown up immersed in technology but has gotten little in the way of research. According to the findings, young people’s propensity to pay extra for ethical products and to buy eco-friendly products is strongly influenced by their relationships with their families and peers, as well as by their level of environmental awareness. The media, on the other hand, has no bearing on the outcome.

5.3. Discussion

On the whole, we have sufficient evidence to confirm that media have a relative influence on ethical behavior of Generation Z. Most noticeably, family members were found to have impact on all dimensions of EMCB. This can be justified through a collectivistic culture rooted in all walks of life in Vietnam (https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/vietnam/). Vietnam is viewed as a highly collectivistic nation, where close networks are valued and encouraged (Hofstede, Citation1984). As a result, prior to deciding on any purchasing activities, it is sensitive for young consumers to refer to their close relationships for consultancy and advice. In particular, compared to other dimensions, parents have the greatest impact on Eco-related behaviors, such as buying an environmentally friendly bulb, or saying no to plastic-made glasses or straws. Also, family are associated with making young consumers willing to pay more for an ethical product.

Peers were discovered to exert influence on the Eco-dimension and Paymore-dimension of EMCB, to a significant extent. More importantly, compared to family, peers have a greater impact. This is in some way in line with previous researches. Throughout their upbringing and development from teenagers to adolescents and then adults, young people are more likely to seek advice from peers rather than families (Singh et al., Citation2006), despite the fact that family still play an important role in their decision-making process. They both appreciate their family and friends for their assistance (Hira, Citation2007). Regarding the CSRBoycott-dimension, it is attention-grabbing, however, that peers show no apparent relationship with refusal to purchase an item based on environmental reasons. As previously mentioned, due to low R square value, the CSRBoycott-dimension is considered an imperfect correlation, thereby making an insignificant contribution to scale comprehension. In reality, young consumers might communicate with both their families and friends upon which choice to make in a certain situation. However, when it comes to the final decision, they are more likely to turn to their parents’ opinion and their own reasoning in order to fulfil their intention. Klein et al. (Citation2004) pointed out that the most influential indicator of consumers’ boycotting involvement is “the perceived egregiousness of the firm’s actions”. Apart from that, consumers’ rational decision to boycott is influenced by numerous additional elements, one of which is their perceived difference they would make if they were to boycott. In other words, their allegedly positive action is deemed to be essential and would make them feel good about themselves, enhancing their self-esteem. Thus, intuitively speaking, motivation to participate in boycotting activities may be due to consumers’ perceived internal value, rather than relate to external connections. Furthermore, it is sometimes the case that consumers value price, quality and benefit of a product more than ethical benchmarks (Carrigan & Attalla, Citation2001). All in all, the weak link between socialization agents and CSRBoycott-dimension implies that denial to purchase a product based on corporate ethics has not been a common practice in Vietnam market.

As for Media, this factor showed no effect on two out of three dimensions of EMCB. Media was found to have impact only on the CSRBoycott-dimension. This means that upon denial to buy a product based on corporate reasons, young consumers are swayed by information from the media, apart from their family and their own environmental concern. However, as previously mentioned, there is a weak link regarding this dimension. Their decision-making process is likely to be swayed by word-of-mouth reference, rather than media (Mangold & Smith, Citation2012). Also, another reason could be attributable to the ambiguity and magnification of media in their pro-environmental messages (Fernando et al., Citation2014).

Environmental concern was discovered to have impact on two out of three dimensions of EMCB, while Generation Z consumers’ intention to favor eco-friendly products (Eco-dimension) has no relation with their personal environmental concern. In particular, the Paymore-dimension, affected by family and peers, is also connected with consumers’ positive interest in environmental issues. These results are in some way contradictory with each other. The lack of environmental concern when it comes to Eco activities is hard for any explanations. It could be due to the fact that when making a decision upon purchasing or boycotting an eco-friendly product, under the influence of their close relationships, young consumers are more likely to complete the action without genuinely reflecting on environmental issues. Their behavior could probably make them feel good about themselves in the presence of their important networks, in that they have done a good deed towards a more sustainable purchasing habit. With that in mind, it is vital that more studies be conducted to examine this contradiction.

5.4. Managerial implications

This study serves as theoretical backgrounds in order for pro-ethics marketing bodies to gain access to potential customers. It might assist marketers in having an in-depth understanding of consumer behavior. Consumers may think one way but act another way. It is of crucial importance, therefore, to clarify this attitude-behavior gap, so that marketers could find an ideal strategy to convey their messages, thereby convincing customers. In addition, the nonexistence of media impact on different dimensions of EMCB points to the need for a more effective utilization of this communication channel. Generation Z’ eagerness to seek information about environmental issues, eco-friendly living or recycling innovations is stronger than ever before. It is often the case that, however, even though they are aware of the imperative subject, whether their positive way of thinking translates into conducting an ethical purchase is uncertain. Likewise, “possessing knowledge about unethical behavior does not necessarily lead a consumer to boycott the unethical firm or its products” (Carrigan & Attalla, Citation2001). Therefore, apart from providing consumers with concise yet meaningful knowledge, marketers also need to ensure media has expected effect on consumers’ actual action, in particular persuading them to agree to a higher price margin.

Also, as the robust impact of close networks was confirmed, marketing strategists are encouraged to make greater use of the mass media to positively manipulate word-of-mouth communication. Even though digitalization has made it easier than ever for young people to keep abreast of the latest issues in an ever-changing world, they are uncertain of dependably trustworthy sources. This results in a likelihood to resort to such intimate relationships as family and friends. If marketers should manage to convince young consumers of their ethical procedures, by proving their integrity and honesty, a potential pro-ethics young generation of consumers can be successfully captured.

5.5. Limitations

As important as this study is to the field of green consumer socialization among Vietnamese millennials, it has some drawbacks. First, as a result of the fact that this subject is still very fresh in Vietnam, the phrasing in the surveys is still unclear, and respondents were required to check the definitions with the author on multiple occasions. Second, there are just two observed variables on the Media Scale, hence it is not ideal for creating the research scale; however, the research adopted the Media scale from Muralidharan & Xue, Citation2016, so the scale should not be modified. This study reduced the number of EMCB components from five in the study of Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (Citation2016) to three components. There is some leeway in this adjustment depending on the study’s specific circumstances. The study’s limitations remain, however, when analyzing the regression of each EMCB component separately, rather than the cumulative regression of all components. EMCB’s socialization agents and environmental concerns are examined using regression in this study. However, there is a relationship between the independent variables and the characteristics of the dependent variable, and future studies can employ the model SEM or PLS-SEM for analysis to better investigate these complicated interactions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ankit, G., & Mayur, R. (2013). Green marketing: Impact of green advertising on consumer purchase intention. Advances in Management, 6(9), 14.

- Arli, D., & Pekerti, A. (2017). Who is more ethical? Cross-cultural comparison of consumer ethics between religious and non-religious consumers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(1), 82–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1607

- Bassiouni, D. H., & Hackley, C. (2014). ’Generation Z’children’s adaptation to digital consumer culture: A critical literature review. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 13(2), 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1362/147539214X14024779483591

- Belk, R., Devinney, T., & Eckhardt, G. (2005). Consumer ethics across cultures. Consumption Markets & Culture, 8(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253860500160411

- Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (1990). Quantitative data analysis for social scientists. Routledge.

- Carrigan, M., & Attalla, A. (2001). The myth of the ethical consumer–do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(7), 560–578. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760110410263

- Carrington, M. J., Neville, B. A., & Whitwell, G. J. (2010). Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(1), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0501-6

- de Koning, J. I. J. C., Crul, M. R. M., Wever, R., & Brezet, J. C. (2015). Sustainable consumption in Vietnam: An explorative study among the urban middle class. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(6), 608–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12235

- Delistavrou, A., Katrandjiev, H., & Tilikidou, I. (2017). Understanding ethical consumption: Types and antecedents. Economic Alternatives, 4, 612–632.

- Fernando, A. G., Sivakumaran, B., & Suganthi, L. (2014). Nature of green advertisements in India: Are they greenwashed? Asian Journal of Communication, 24(3), 222–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2014.885537

- Flurry, L. A., & Swimberghe, K. (2016). Consumer ethics of adolescents. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 24(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2016.1089766

- Gaudelli, J. (2009). The greenest generation: The truth behind millennials and the green movement. Advertising Age.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall Upper Saddle.

- Hindol, R. (2012). Environmental advertising and its effects on consumer purchasing patterns in West Bengal, India. Research Journal of Management Sciences , 2319, 1171.

- Hira, N. A. (2007). Attracting the twenty something worker. Fortune Magazine.

- Hoàng, T., & Chu, N. M. N. (2008). Phân tích dữ liệu nghiên cứu với SPSS-Tập 1. NXB Hồng Đức.

- Hofstede, G. H. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values (abridged ed.). Sage Publications.

- Klein, J. G., Smith, N. C., & John, A. (2004). Why we boycott: Consumer motivations for boycott participation. Journal of Marketing, 68(3), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.3.92.34770

- Le, T. D., & Kieu, T. A. (2019). Ethically minded consumer behaviour in Vietnam: An analysis of cultural values, personal values, attitudinal factors and demographics. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 31(3), 609–626. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-12-2017-0344

- Lee, K. (2008). Opportunities for green marketing: Young consumers. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(6), 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500810902839

- Lu, L.-C., & Lu, C.-J. (2010). Moral philosophy, materialism, and consumer ethics: An exploratory study in Indonesia. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0256-0

- Lueg, J. E., & Finney, R. Z. (2007). Interpersonal communication in the consumer socialization process: Scale development and validation. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679150102

- Mallery, P., & George, D. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. Allyn.

- Mangold, W. G., & Smith, K. T. (2012). Selling to Millennials with online reviews. Business Horizons, 55(2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.11.001

- Mohr, L. A., Eroǧlu, D., & Ellen, P. S. (1998). The development and testing of a measure of skepticism toward environmental claims in marketers’ communications. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 32(1), 30–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1998.tb00399.x

- Moschis, G. P., & Churchill, G. A., Jr. (1978). Consumer socialization: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(4), 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377801500409

- Muncy, J. A., & Vitell, S. J. (1992). Consumer ethics: An investigation of the ethical beliefs of the final consumer. Journal of Business Research, 24(4), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(92)90036-B

- Muralidharan, S., & Xue, F. (2016). Personal networks as a precursor to a green future: A study of “green” consumer socialization among young millennials from India and China. Young Consumers, 17(3), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-03-2016-00586

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2010). Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(11), 1451–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004

- Polonsky, M. J., Brito, P. Q., Pinto, J., & Higgs-Kleyn, N. (2001). Consumer ethics in the European Union: A comparison of northern and southern views. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010780526643

- Rawwas, M. Y. (1996). Consumer ethics: An empirical investigation of the ethical beliefs of Austrian consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(9), 1009–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00705579

- Shaw, D., Grehan, E., Shiu, E., Hassan, L., & Thomson, J. (2005). An exploration of values in ethical consumer decision making. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 4(3), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.3

- Singh, N., Chao, M. C., & Kwon, I. W. G. (2006). A multivariate statistical approach to socialization and consumer activities of young adults: A Cross-Cultural study of ethnic groups in America. Marketing Management Journal, 16(2), 67-80.

- Sudbury-Riley, L., & Kohlbacher, F. (2016). Ethically minded consumer behavior: Scale review, development, and validation. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2697–2710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.11.005

- Vitell, S. J., & Muncy, J. (1992). Consumer ethics: An empirical investigation of factors influencing ethical judgments of the final consumer. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(8), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00872270

- Vitell, S. J., & Muncy, J. (2005). The Muncy–Vitell consumer ethics scale: A modification and application. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(3), 267–275. doi:10.1007/s10551-005-7058-9

- Vitell, S. J. (2009). The role of religiosity in business and consumer ethics: A review of the literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(S2), 155–167. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0382-8

- Vitell, S. J., King, R. A., Howie, K., Toti, J.-F., Albert, L., Hidalgo, E. R., & Yacout, O. (2016). Spirituality, moral identity, and consumer ethics: A multi-cultural study. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(1), 147–160. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2626-0

- Williams, F., & Monge, P. (2001). No. 001.422 W5. Reasoning with statistics how to read quantitative research.

- Witkowski, T. H., & Reddy, S. (2010). Antecedents of ethical consumption activities in Germany and the United States. Australasian Marketing Journal, 18(1), 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2009.10.011