?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study aims to analyse tax noncompliant activities by specifically examining the effect of tax amnesty on taxpayers’ compliant behaviour. Indonesia is taken as a case study since it is a populous country with a high dependency on tax revenue and a long history of tax reforms of more than 20 years. In this study, the 2008 tax amnesty is analysed since the policy targeted both individual and corporate taxpayers; hence it is argued to provide a more comprehensive analysis. The analysis is based on 5-year data before and after the 2008 tax amnesty (periods of 2003 to 2013). A trend analysis is conducted to show the compliance of both individual and corporate taxpayers in terms of the total number of taxpayers submitting annual tax returns and total income tax collected. In addition to the trend analysis, to examine the corporate taxpayers’ compliance, this study conducts a regression analysis with a moderating variable of foreign investors to examine corporate taxpayers’ compliance proxied by tax aggressiveness, before and after-tax amnesty. Manufacturing listed companies with a total of 783 observations are chosen as the sample. This study found that tax amnesty is effective in increasing the compliance of individual taxpayers only. The results show further that after-tax amnesty, corporate tax aggressiveness increased, and foreign investors are found to strengthen this condition.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Taxation is arguably the most important revenue source for many countries around the world, especially in the context of achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The phenomena of tax noncompliance, indeed, have gained the attention of tax authorities and researchers around the world over the decades. This paper fills the gap in tax noncompliance literature by analysing the long-term impact of tax amnesty policy in a developing country, i.e. Indonesia, since it is a populous country with a high dependency on tax revenue and a long history of tax reforms. Focusing on a 2008 tax amnesty, the analysis which is based on 5-year data before and after the amnesty found that tax amnesty is effective in increasing the compliance of individual taxpayers only. The results show further that after-tax amnesty, corporate tax aggressiveness increased, and foreign investors are found to strengthen this condition.

1. Introduction

Taxation is arguably the most important revenue source for many countries around the world, as it can constitute more than 50% of the total government revenue (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, Citation2020). Tax revenues as a percentage of GDP i.e. Tax-to-GDP ratios across 80 countries range from 10.8% to 45.9% (OECD, Citation2018). In most countries, this ratio has an increasing trend as in OECD countries, the average 2018 ratio slightly increased to 34.3% from 34.2% in 2017, while the ratio was 34% in 2016 and 33.7% in 2015. In many Asian economies, the tax-to-GDP ratio changed from −1.4% to 2.5% from 2017 to 2018 (OECD, Citation2020).

Despite this increasing trend in an emerging economy, Indonesia experienced a lower tax ratio to GDP than other developing economies. While Indonesia’s tax revenue is more than 82% of the total revenue budget, data from OECD (Citation2020) shows that Indonesia’s tax-to-GDP ratio is only 11.9%, while the neighbour countries are 12.5% (Malaysia), 13.2% (Singapore), 17.5% (Thailand) and 18.2% (Philippines). The fact that Indonesia is one of the most populous countries, but it experiences the lowest tax ratio to GDP in Southeast Asia, needs to be examined further, especially related to tax compliance, as it is confirmed to be a low tax compliance rate (Brondolo et al., Citation2008). Moreover, it is important to evaluate the efforts of the Indonesian government in collecting tax revenue and improving tax compliance through tax reform programs which have already taken place, as documented by Brondolo et al. (Citation2008); from the strict tax reform such as tax amnesty programs in 1964, 1984, and the latest in 2016, to other types of reform such as small tax amnesty programs, i.e. the sunset policies in 2008, the changes in the tax rate, i.e. corporate tax rate in 2010, and yet another tax amnesty program called “a voluntary disclosure program” which has just about to begin in 2022. The tax amnesty program is argued to be a controversial revenue-raising tool of the government in combating tax evasion. As a politically popular way to generate government revenue, enacted in the previous years, this tax amnesty program is argued to have more political rather than economic aspects. Despite its effectiveness in generating immediate revenues for the governments, its long-term impact on tax compliance is questionable (Alm & Beck, Citation1993; Alm et al., Citation2009; Baer & Le Borgne, Citation2008; Saraçoğlu & Çaşkurlu, Citation2011).

The phenomena of tax noncompliance, indeed, have gained the attention of tax authorities and researchers around the world over the decades. Fischer et al. (Citation1992) identified three variables explaining direct tax compliance behaviour: noncompliance opportunity, tax system/structure, and attitudes and perceptions. Two indirect categories are related to demography and culture (added in the modification of the Fischer model). Research in tax noncompliance can be divided into two main areas (Borrego et al., Citation2013). They are firstly, the studies that attempt to explain tax noncompliance and the attitudes of taxpayers towards tax, and secondly, the studies which seek to quantify it using a proxy, for example, aggressive tax management (tax avoidance), illegal tax avoidance (tax evasion, tax fraud) and other mechanisms leading to tax noncompliance. Moreover, Borrego et al. (Citation2013) stated that most studies are from developed countries, i.e. Anglo-Saxon countries, particularly the US. They also found that the literature lacks studies that examine involuntary tax noncompliance. This involuntary tax noncompliance is indeed necessary to be explored; as found by McKerchar (Citation2002), in examining unintentional noncompliance of taxpayers, taxpayers experienced a high level of errors causing unfair overstatement of tax liability when they conducted voluntary compliance in the tax return. The study found unintentional noncompliance of taxpayers related to tax complexity. This complexity mostly relates to the ambiguity of tax laws and the voluminous of explanatory material required.

This paper fills the gap in tax noncompliance literature by analysing the long-term impact of tax amnesty policy in a developing country, i.e. Indonesia, since it is a populous country with a high dependency on tax revenue and a long history of tax reforms. A 2008 Tax Amnesty Program is chosen to be analysed by this study instead of the current 2016 since the 2008 Tax Amnesty targeted both individual and corporate taxpayers; hence it is argued to be more comprehensive to analyse the impact of the policy. Moreover, studying both individual and corporate taxpayers is important for Indonesia since, as a populous country, it is an anomaly that currently, the biggest tax revenue is collected from corporate rather than individuals. Hence, a trend analysis of the compliance behaviours of both individual and corporate taxpayers is presented in this study. In addition to the trend analysis, a regression analysis is also conducted to examine the effect of the policy on compliance of the main contributor of tax revenue of Indonesia, i.e. corporate taxpayers. Tax aggressiveness is used as a proxy for tax noncompliance. This paper follows OECD (Citation2018) and Borrego et al. (Citation2013) which classify tax aggressiveness as one of the tax noncompliant behaviours of taxpayers, i.e. deliberate noncompliance. This paper provides a practical contribution to the policymakers regarding the necessity to maintain tax-compliant behaviour following the tax amnesty program.

The structure of the paper is as follows: after the introduction, previous literature is critically reviewed. Then, the third section presents the research method and data analysis. This is followed by section four which presents an analysis and discussion of the results. The last section presents the conclusion and implications of the study.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Tax compliance and theories of tax compliance

Tax compliance, as defined by OECD (Citation2010), is a condition when a taxpayer cumulatively meets these four requirements: 1) registered for tax purposes; 2) filing tax returns on time (i.e. by the date stipulated in the law) or at all; 3) correctly reporting tax liabilities (including as withholding agents); 4) paying taxes on time (i.e. by the date stipulated in the law). Consequently, the conduct of not meeting one of the above four requirements can be defined as tax noncompliance. In addition to these definitions, OECD () identifies types of tax noncompliance which can be deliberate or not. One of the examples of intentional tax noncompliance is tax avoidance, including aggressive tax planning (OECD, Citation2017).

In line with OECD, Borrego et al. (Citation2013) stated that the definition of tax noncompliance, as documented by previous literature, is much broader as it covers all intentional schemes of failing to meet tax compliance criteria as well as all unintentional tax noncompliance, and whether it is conducted in legal or illegal ways. Therefore, non-compliant tax activities can vary and cover not only unintentional mistakes in fulfilling tax obligations but also intentional aggressive tax management, tax avoidance, and illegal tax fraud.

Various factors can influence the tax compliance of taxpayers. According to Fischer et al. (Citation1992) and other scholars (Devos, Citation2013; Marandu et al., Citation2015; Richardson & Sawyer, Citation2001), these causes can be categorised into direct and indirect factors. Direct factors include noncompliance opportunity (i.e. income, level, income source, occupation), tax system/structure (i.e. complexity of tax system, probability of detection, penalties and tax rate), and attitudes and perceptions (i.e. fairness of tax systems, peer influence) while two indirect variables are related to demography and culture (added in the modification of Fischer model). Religiosity and national culture are also found to be important variables that decrease tax evasion (Sutrisno & Dularif, Citation2020).

Examining incompliant behaviours of taxpayers, based on the Prospect Theory of Kahneman and Tversky (Citation2013), taxpayers can be considered risk-takers or risk-averse in the condition of a condition whether prepaid taxes are greater or lesser than the actual tax liability. Hence, if the tax authorities deliberately set the advance payments slightly above the taxpayer’s actual tax liability, there will be a specific condition that the taxpayer will gain from filing a return; therefore, noncompliance can be avoided (Elffers & Hessing, Citation1997).

2.2. Tax amnesty, tax compliance, and tax aggressiveness

To improve tax compliance and increase tax revenue, governments around the world often adopt such various additional tax policy schemes as tax amnesty and other tax reform programs. The tax amnesty program, for example, is a program that provides opportunities for individuals and companies to report and pay taxes that have not been paid before, without the imposition of part or all the administrative and criminal sanctions as imposed on the discovery of normal tax avoidance practices (Alm & Beck, Citation1993). By definition, it is “a limited time offer by the government to a specified group of taxpayers to pay a defined amount, in exchange for forgiveness of a tax liability (including interest and penalties), relating to previous tax period (s), as well as freedom from legal prosecution” (Baer & Le Borgne, Citation2008). While this kind of program is often used by governments around the world, both developed and developing countries, to generate an immediate, short-run increase in compliance as well as tax revenue, the impact of the tax amnesty program often does not run as smoothly as expected. The long-term impact of this program also needs to be questioned as it is argued that tax amnesty has the possibility of reducing compliance in the future (Alm & Beck, Citation1993; Alm et al., Citation2009; Baer & Le Borgne, Citation2008; Saraçoğlu & Çaşkurlu, Citation2011). Heinemann and Kocher (Citation2013), conducting a laboratory experiment, found that tax evasion increases after-tax reform while, in the case of reform from a proportionate to a progressive system, tax compliance decreases compared to a switch in the reverse direction.

Alm and Beck (Citation1993) and Baer and Le Borgne (Citation2008) argued tax amnesty is successful if it is followed by some procedures such as greater enforcement efforts and improvement in taxpayer services. It increases tax compliance if it can get more individual taxpayers to file tax returns on the tax rolls. On the other hand, it may have a deteriorating effect since it can be seen as an unfair tax break for tax cheats. There will also be an expectation that tax amnesty is repeated in the future so that it may delay individuals from participating in the current tax amnesty. The frequently exercised tax amnesty may indicate the pervasive and easy conditions of noncompliance.

Despite the pros and cons of tax amnesty, at least 37 countries around the world, including south-east Asia countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand are recorded conducting the policy (Baer & Le Borgne, Citation2008; Hermansyah, Citation2016; Huda & Hernoko, Citation2017). Argentina, which conducted several times of tax amnesty, is argued to have been successful in its last tax amnesty in 2017 compared to other countries in collecting the tax revenue (Aseng, Citation2017; Higgins Citation2017; StaufferCitation2017, January 3). Other countries that recorded successful tax amnesties are, for example, India in 1997 ($2.5 billion), Ireland in 1988 ($700 million), Italy in 2002 on capital repatriation amnesty, and the United States as the gross revenue collected from the 78 amnesties during the period 1980–2004 totalled $6.6 billion (Baer & Le Borgne, Citation2008). Brazil’s second-round tax amnesty in 2017, on the other hand, is argued to be unsuccessful in terms of tax collection compared to its first-round (Reuters, Citation2017). Specific to the Indonesian case, tax amnesty programs have been conducted several times; for example, in 1964 and in 1984, which unfortunately showed low participation of taxpayers. Then in 2008, a lighter tax amnesty program called the Sunset Policy was also conducted with the benefit of elimination of interest sanctions on unpaid or underpaid taxes applied to individual taxpayers (for both of who had and had not Taxpayer Identification Number-Tax ID Number) and corporate taxpayers (who had Tax ID Number; Indonesia, Citation2007, Citation2008). This 2008 policy is argued to be successful as it exceeded the revenue target in the last ten years of that period (Tambunan, Citation2015). Following the 2008 program, Reinventing Policy in 2015 was launched and was conducted in 2016 with its main objective to repatriate the capital and assets deposited by taxpayers abroad to avoid taxes applied in Indonesia.

In regards to total reform programs, Indonesian studies reveal different findings; for example, Tjen and Abbas (Citation2010) argued that Indonesia Sunset Policy was not effective since the increasing number of individual taxpayers in the Sunset Policy comprised of employees who were not the tax authority’s main target since the employees have their tax obligations withheld and paid by their employers, regardless of whether they have a Tax ID Number. On the other hand, Winastyo (Citation2010) and Mahestyanti et al. (Citation2018) argued that the Sunset Policy succeeded in achieving its targets in the short term, specifically in raising awareness of paying taxes and increasing the understanding of taxpayers regarding applicable tax regulations, hence increasing taxpayers’ compliance. Sayidah and Assagaf (Citation2019) found that the purpose of tax amnesty is mostly for a short-term goal which is to increase tax revenue in the budget state.

Regarding the unsuccessful tax amnesty program, at least two factors that are related to social psychology can explain the problem. Firstly, tax amnesty is believed to be a form of unfair treatment by the state, that is as a form of special treatment to tax evaders, and secondly, tax amnesty is conducted not only once but several times (Alm & Beck, Citation1993; Alm et al., Citation2009; Baer & Le Borgne, Citation2008; Saraçoğlu & Çaşkurlu, Citation2011). Then, regarding low compliance of taxpayers and the emergence of tax avoidance practices, Baer and Le Borgne (Citation2008) argued that tax noncompliance is due to fundamental problems consisting of weak tax administration and weak law enforcement in the country, as well as insufficient tax regulations and policies to overcome the compliance problem. Another condition that makes successful tax amnesty is economic liberalisation and/or technological progress (Bose & Jetter, Citation2010, Citation2012).

2.3. Hypotheses of the study to examine the corporate taxpayers’ compliant behaviour

Having discussed the pros and cons of tax amnesty and some findings related to the amnesty in the short-term and long-term, this study evaluates the Indonesian tax amnesty using a trend analysis and regression analysis. A trend analysis is carried out to depict the compliance behaviours of taxpayers before and after-tax amnesty in terms of the total number of taxpayers submitted annual tax returns and total income tax collected. To evaluate whether tax amnesty relates to tax compliance, a regression analysis is further conducted.

In the regression analysis, corporate tax aggressiveness is used as a proxy of tax noncompliance as it is identified as one of the deliberate tax noncompliance activities (Borrego et al., Citation2013; OECD,), hence corporate tax aggressiveness before and after-tax amnesty is tested. As discussed previously, while tax amnesty is expected to increase tax compliance in the future (Baer & Le Borgne, Citation2008), the findings show differently (Ahmed, Citation2020; Alm & Beck, Citation1993; Alm et al., Citation2009; Baer & Le Borgne, Citation2008; Saraçoğlu & Çaşkurlu, Citation2011). Therefore, the proposed Hypothesis 1 (H1) to examine the effect of tax amnesty is as follows.

H1: Tax amnesty affects corporate tax aggressiveness.

Regarding other tax non-compliant factors, many factors are found associated with tax noncompliance, for example, industry (Hanlon & Slemrod, Citation2009), size of companies, leverage, financial performance (ROA), and external auditor (Kourdoumpalou & Karagiorgos, Citation2012; Putri, Citation2015). Firm age is also found to be negatively associated with tax noncompliance characteristics (Wahlund, Citation1992; Wärneryd & Walerud, Citation1982; Wearing & Headey, Citation1997). Company size is found to be various that some studies found a negative association (Khuong, Citation2020; Nor et al., Citation2010; Tedds, Citation2010), while other studies found it has no effect on tax compliance (Hani & Lubis, Citation2016). In addition to these existing factors mostly found in the literature, this study examines the effect of foreign investors on tax aggressiveness. This study argues that this factor is important as one of the controlling mechanisms in a company. Many previous studies found significant positive relationships between foreign investors and corporate tax avoidance (Alkurdi & Mardini, Citation2020; Andrialdi et al., Citation2019; Pratama, Citation2020; Salihu et al., Citation2015; Shi et al., Citation2020). Different from the previous study, this study examines the effect of foreign investors as a moderating variable; hence Hypothesis 2 (H2) is proposed as follows:

H2: Foreign investors strengthen corporate tax aggressiveness.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Population and sample

For the trend analysis, data of individual and corporate taxpayers from 2003 to 2013 is collected. The data is collected from the Indonesia Directorate of Tax Potency and Compliance. Specific to the regression analysis, data of manufacturing companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) is collected. The manufacturing industry is chosen due to its large number in IDX so that it more represents IDX listed companies. Moreover, the manufacturing industry applies a normal general tax regulation, while other sectors such as bank and financial institutions, real estate, and construction, apply specific tax rules/final income tax regulations. All companies’ data used in this study are secondary data obtained from either the Thomson-Reuters database or from financial statements of related companies.

The 2004–2013 periods were chosen to cover the conditions before and after the implementation of the 2008 Sunset Policy. Ideally, a span of 5 years was selected as a long-term range; however, according to Martani et al. (Citation2011), there are abnormal permanent differences caused by foreign exchange gains in 2003. Therefore, this study observed it during the period of 2004 until 2013, where 2004–2007 represented the period before Sunset Policy, 2008 represented the Sunset Policy period, and 2009–2013 represented the period after the Sunset Policy. Meanwhile, the 2008 period was eliminated to avoid bias since it was a transition period where the Sunset Policy was held. The study is limited to 2013 to exclude the effect of another tax amnesty program held in Indonesia in 2015–2016. At least 138 manufacturing companies had been on IDX from 2004 to 2013. Using a balanced panel data analysis, only 87 out of 138 companies passed the sample selection criteria, and hence for a nine-year research period, a total of 783 observations were used in this study.

3.2. Operationalisation of variables

In conducting the trend analysis, following the definition of OECD (Citation2010), tax compliance is measured by the total number of registered taxpayers and submissions of tax returns. While previous research (Alm & Beck, Citation1993; Alm et al., Citation2009) conducted a time series to examine whether there is a change in the trend of monthly tax revenue, in the long run, this study will be carried out with a descriptive analysis due to some limitations of existing data.

To examine the hypotheses, the level of compliance is measured using the company’s tax aggressiveness (Borrego et al., Citation2013; OECD). The higher the company’s tax aggressiveness, the lower the company’s tax compliance. Foreign investors are measured by the percentage of foreign ownership reported in financial statements.

The implementation of the 2008 Sunset Policy was accompanied by a reduction in applicable tax rates. Thus, to prevent bias in the results of the study, this study chose to use the Book Tax Difference (BTD) variable, instead of Effective Tax Rate (ETR), as a variable operationalising the level of corporate tax aggressiveness (TaxAgg). This study uses two types of BTD: Total BTD and Permanent BTD, to get comprehensive results. According to Manzon and Plesko (Citation2002), this study will use the measurement of Total BTD (TBTD) in accordance with its definition, namely the total difference between income before tax based on accounting and estimated fiscal taxable income. Meanwhile, the measurement of Permanent BTD (PBTD) is based on the permanent difference only. The results of the measurements are then normalised with the total assets of the company at the beginning of the year. Model 1 is proposed as follows to examine whether the 2008 Sunset Policy affects tax aggressiveness. Following previous studies (Surbakti, Citation2012; Yuan et al., Citation2012), some controlling variables are used in the model. The models for testing the hypotheses are as follows.

Model 1:

Model 2:

where:

TaxAgg = Tax avoidance (TBTD, PBTD);

PostTA = Dummy variable stating the period before (0) and after (1) the Sunset Policy;

Foreign = Proportion of foreign investor ownership in companies;

PostTA x Foreign = Interaction variable between PostTA and Foreign;

PP&E = Net fixed assets normalised with total assets at the beginning of the year;

ROA = Return on company assets;

LEV = The ratio between long-term debt and total company assets;

SIZE = Natural logarithm of total company assets.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Trend analysis of tax compliance before and after-tax amnesty

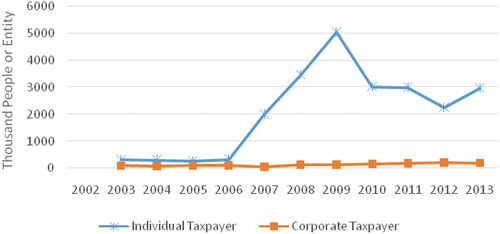

The following data illustrates the condition of the tax base, tax compliance (specifically in collecting tax returns), and income tax revenue of Indonesia from 2003 to 2013. One way to measure the tax base is using data on the number of taxpayers. The more taxpayers, the more income should be taxed. and show that the significant increment only occurred in the number of individual taxpayers while the number of corporate taxpayers tends to be constant.

Figure 1. Increment in the Number of Individual Taxpayers and Corporate Taxpayers for Periods 2003–2013.

Table 1. Total Registered Taxpayers for Periods 2002–2013*

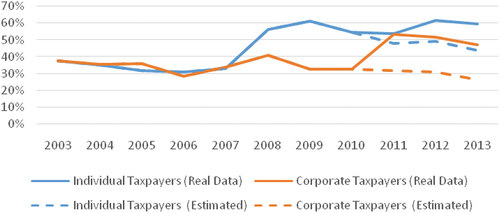

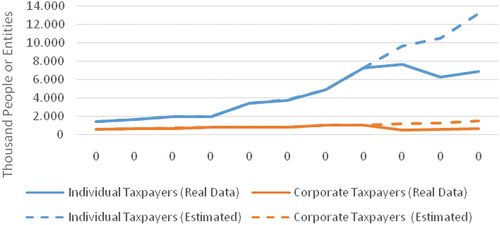

, and , depict the conditions related to taxpayers’ compliance, especially in terms of submitting their tax returns. In this case, the result shows that the individual taxpayers’ compliance in submitting their tax returns increased sharply in 2009, and it lasted for at least five years. On the other hand, corporate taxpayers showed a different trend. The compliance of corporate taxpayers is more stable, despite the very slight increase. It returned to its original condition after the Sunset Policy period ended. Furthermore, despite the effectiveness of increasing the number of tax returns submitted, the number of taxpayers who do not lodge their tax returns is also increasing yearly for both categories of taxpayers.

Figure 2. Compliance ratio for periods 2003–2013.

Figure 3. Number of taxpayers not submitting tax returns for periods 2003–2013.

Table 2. Compliance ratio for periods 2003–2013*

Table 3. Number of Taxpayers Not Submitting Tax Returns for Periods 2003–2013*

, and above also show the estimated numbers for the periods of 2011–2013. This is due to, in 2011, the Directorate General of Tax (DGT) of Indonesia held a National Tax Census for the first time. Through this program, DGT classifies and recalculates taxpayers who are required to submit their tax return based on the new criteria. As a result, the number of taxpayers who are required to submit the annual tax return decreased, which leads to an increase in the compliance ratio calculated. This can lead to a higher risk of misinterpretation than the data before the census (the classification and the calculation are based on the previous criteria before the census). Therefore, for this study’s objective, the estimation of compliance ratios for 2011–2013 is depicted in the tables to show the estimation figure if the classification and calculation were based on the previous criteria before the census. The estimated numbers shown in and confirm the compliance ratio based on the actual data. After the Sunset Policy, the compliance ratios returned to the ratios before the tax amnesty program, showing a decreasing trend. and confirm further that the total number of taxpayers who did not submit their tax return increased after the Sunset Policy.

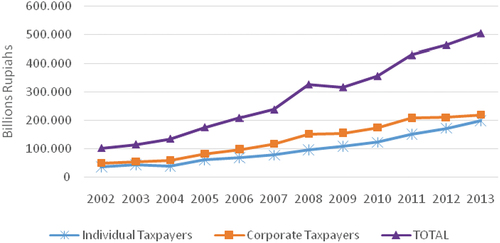

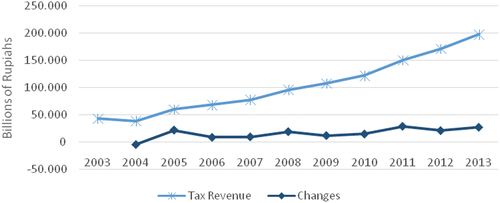

Finally, illustrate the accumulated impact of changes in the tax base and compliance, which should impact long-term revenue from income tax. The increase in the number of individual taxpayers and their compliance in submitting their tax returns positively impact the income tax revenue in the long run (). On the other hand, the number of corporate taxpayers tends to be stable, and their compliance in submitting their tax returns also tends to return to their original condition. These indicate that income tax revenue is only earned in the short term and tends not to impact long-term revenue (). However, in total, since the income tax originating from corporate taxpayers is far greater than the income tax originating from individual taxpayers, then the positive impact on income from individual taxpayers tends to be overshadowed. Thus, the increase in income tax revenue seems to be only earned in the short term, i.e.1–5 years, not in the long term, i.e. more than five years.

Figure 4. Total Indonesian Tax Revenue for All Categories of Taxpayers for Periods 2003–2013—All Taxpayers.

Figure 5. Total Indonesian Tax Revenue for All Categories of Taxpayers for Periods 2003–2013—Individual Taxpayers.

Figure 6. Total Indonesian Tax Revenue for All Categories of Taxpayers for Periods 2003–2013—Corporate Taxpayers.

Based on the above results, it can be concluded that the 2008 Sunset Policy has succeeded in achieving its specific goal to increase tax participation from individual taxpayers and increase income tax revenue in the long run from individual taxpayers. This is characterised by the increase in the number of individual taxpayers (Tax Base), the increase in tax compliance of individual taxpayers in the period, and the increase in income tax revenue from individual taxpayers. Thus, this study complements the results of research by Winastyo (Citation2010) and Anggraeni and Kiswara (Citation2011) and shows that Sunset Policy, for the target of individual taxpayers, achieves its goals in the short term and long term.

4.2. The effect of tax amnesty on corporate tax aggressiveness

To analyse the effect of tax amnesty on corporate tax aggressiveness, this study conducted three tests, i.e., the F-Restricted test, Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test, and Hausman test. The three tests showed that the Fixed Effect (FE) research model is the most appropriate method for the study. This FE method is more suitable as this study focuses more on the impact of variables that change over time, rather than on the type/fixed characteristics of each sample, i.e. firm characteristics.

below depict the results of multiple regressions of the two models used in examining the effect of tax reforms on corporate tax aggressiveness. Generalised Least Square (GLS) is used for the study’s Fixed-Effect (FE) model. shows Post TA variable has a positive coefficient that indicates an increase in tax aggressiveness after the Sunset Policy. shows a positive coefficient of interaction variables between Post TA and Foreign, suggests that foreign ownership increases the level of tax aggressiveness that occurs after the Sunset Policy (the coefficient of PostTA in Model 1 is 0.0087 while adding Foreign to PostTA in Model 2 resulted in an increase in the coefficient to 0.0242).

Table 4. Model 1 regression test results

Table 5. Model 2 regression test results

Based on the results, the Sunset Policy has been found to be ineffective in increasing the compliance of corporate taxpayers of listed manufacturing companies in Indonesia. This is supported by the empirical results indicating that the Policy tends to increase the tax aggressiveness of corporate taxpayers, especially for foreign-owned companies.

Compared to previous studies (Desai, Citation2003; Manzon & Plesko, Citation2002), it is likely that the increase resulted from the perceptions of corporate taxpayers of the Sunset Policy and the following tax reform in Indonesia. Since the Sunset Policy was focused more on individual taxpayers, as indicated in Sunset Policy socialisations(DGT, Citation2008), this program could also be viewed as a reduction of government focus on corporate taxpayers. Thus, this encourages corporate taxpayers to increase their tax aggressiveness, as argued by previous studies that tax amnesty can only run effectively if there is a perception of an increase in tax enforcement in the future (Alm & Beck, Citation1993; Kara, Citation2014; Uchitelle, Citation1989). Moreover, the corporate tax rate that has declined from 28% to 25%, which was announced in 2008 but effective in 2010. The increasing tax rate is also predicted to affect corporate tax aggressiveness.

In contrast to foreign investors, in the Indonesian case, when there is a change in tax regulations, foreign ownership tends to make companies more reactive to the dynamics of the government’s policy. Since the foreign investors have a comparative advantage through the scale of their international networking to avoid taxes (Alkurdi & Mardini, Citation2020; Andrialdi et al., Citation2019; Pratama, Citation2020; Salihu et al., Citation2015; Shi et al., Citation2020), investors also have a higher inclination to conduct tax avoidance practices.

5. Conclusion, implications, and suggestions for future studies

The objective of this study is to examine the effectiveness of tax reforms on tax compliance. Indonesia is chosen as the case study due to its specific tax reform program. Taking the 2008 Sunset policy as one of the tax reforms, the results of this study indicate that the Sunset Policy was only effective in achieving its specific objective of increasing the tax participation of individual taxpayers. This study suggests that while there is an increase in the number of new individual taxpayers, the increase in compliance of individual taxpayers, as well as the increase in income tax revenue derived from individual taxpayers, in the long run, the policy is not effective upon corporate taxpayers. A detailed analysis of corporate aggressiveness confirms the ineffectiveness of the Sunset Policy on the behaviour of corporate taxpayers since there was an increasing trend in corporate tax aggressiveness in the post-Sunset Policy period. The results of the study also show an indication of the influence of foreign ownership in determining changes in the level of corporate tax aggressiveness in terms of responding to policies issued by the government. Overall, the study results bring implications to the academic literature by providing a more comprehensive analysis in investigating the effectiveness of tax reform on tax compliance. The study also brings practical contributions to the tax authority by providing evidence to evaluate the long-run effect of tax amnesty and the necessity to maintain the tax compliant behaviour following the tax amnesty program. This study limits its definition of tax noncompliance to tax aggressiveness (OECD, Citation2017, p. Citation2018) and does not perceive tax aggressiveness as one of the financial crimes or one of the methods of money laundering (Achim & Borlea, Citation2020). Therefore, this study can be extended by, for example, conducting a more detailed analysis such as content analysis of the Tax Assessment Letter issued by the tax authority, which shows the compliance of taxpayers’ self-assessment tax activities. Moreover, a further investigation can be conducted to examine whether tax aggressiveness is related to or perceived as one of the financial crimes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the research funding from Research Grant PUTI Q2 Universitas Indonesia (Ref: NKB-1775/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Siti Nuryanah

Siti Nuryanah is a researcher and lecturer in Accounting at the Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia. She previously taught Accounting and Business at Victoria University and Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. She is also a consultant in business and tax. Her research spans accounting, tax, finance, governance, and sustainability. She contributes to academic literature by writing books and papers published in national and international refereed journals.

Gunawan Gunawan

Gunawan Gunawan is an undergraduate in Accounting from Universitas Indonesia with a main interest in tax. He has working experience in corporate tax and transfer pricing from reputable consulting firms in Indonesia. Currently, he is involved in a project responsible for innovating and developing tax technologies in DDTC Indonesia.

References

- Achim, M. V., & Borlea, S. N. (2020). Economic and financial crime: Theoretical and methodological approaches. In S. Dina (Ed.), Economic and financial crime (Vol. 20, pp. 1–71). Springer. Studies of Organized Crime. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51780-9_1

- Ahmed, S. U. (2020). Tax amnesty schemes in Bangladesh: Some observations. The Cost and Management, 48(3), 35–40. http://www.icmab.org.bd/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/4.Tax-Amnesty-Schemes.pdf

- Alkurdi, A., & Mardini, G. H. (2020). The impact of ownership structure and the board of directors’ composition on tax avoidance strategies: Empirical evidence from Jordan. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 18(4), 795–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-01-2020-0001

- Alm, J., & Beck, W. (1993). Tax amnesties and compliance in the long run: A time series analysis. National Tax Journal, 46(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/NTJ41788996

- Alm, J., Martinez-Vazquez, J., & Wallace, S. (2009). Do tax amnesties work? The revenue effects of tax amnesties during the transition in the Russian Federation. Economic Analysis and Policy, 39(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0313-5926(09)50019-7

- Andrialdi, A., Nuryanah, S., & Islam, S. M., 2019, January. Foreign investor’s interests and tax avoidance. In 33rd International Business Information Management Association Conference: Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020, IBIMA 2019 (pp. 9319–9328). International Business Information Management Association, IBIMA.

- Anggraeni, M. D., & Kiswara, E. (2011). Pengaruh Pemanfaatan Fasilitas Perpajakan Sunset Policy Terhadap Tingkat Kepatuhan Wajib Pajak. ( Undergraduate Thesis). Universitas Diponegoro.

- Aseng, Andrew C. (2017). Tax Amnesty Implementation in Selected Countries and Its Effectivity. Paper presented at The 5th International Scholars Conference (5ISC), Asia-Pacific International University, Muak Lek, Thailand.

- Baer, K., & Le Borgne, E. (2008). Tax amnesties: Theory, trends, and some alternatives. International Monetary Fund.

- Borrego, A. C., da Mota Lopes, C. M., & Ferreira, C. M. S. (2013). Tax noncompliance in an international perspective: A literature review. Contabilidade & Gestão, 14, 9–41. https://www.occ.pt/fotos/editor2/cg14_c.pdf#page=9

- Bose, P., & Jetter, M. (2010). A tax amnesty in the context of a developing economy. Department of Economics University of Memphis. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10 .1.1.629.582&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Bose, P., & Jetter, M. (2012). Liberalisation and tax amnesty in a developing economy. Economic Modelling, 29(3), 761–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.01.017

- Brondolo, J., Bosch, F., Le Borgne, E., & Silvani, C. (2008). Tax administration reform and fiscal adjustment: The case of Indonesia (2001-07) (Vols. 8-129). International Monetary Fund.

- Desai, M. A. (2003). The divergence between book income and tax income. Tax Policy and the Economy, 17, 169–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/tpe.17.20140508

- Devos, K. (2013). Factors influencing individual taxpayer compliance behaviour. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7476-6

- DGT. (2008). Instruksi Direktur Jenderal Pajak Nomor Ins - 2/Pj/2008 Tentang Optimalisasi Pelaksanaan Ketentuan Sunset Policy (instruction of the director general of taxes number Ins - 2/Pj/2008 concerning optimizing implementation of the sunset policy provisions). Directorate General of Taxes.

- Elffers, H., & Hessing, D. J. (1997). Influencing the prospects of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18(2–3), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(97)00009-3

- Fischer, C. M., Wartick, M., & Mark, M. M. (1992). Detection probability and taxpayer compliance: A review of the literature. Journal of Accounting Literature, 11, 1. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/detection-probability-taxpayer-compliance-review/docview/216306252/se-2?accountid=17242

- Hani, S., & Lubis, M. R. (2016). Pengaruh karakteristik perusahaan terhadap kepatuhan wajib pajak (The influence of company characteristics on taxpayer compliance). JRAB: Jurnal Riset Akuntansi & Bisnis, 10(1), 67–82. http://jurnal.umsu.ac.id/index.php/akuntan/article/view/466/429

- Hanlon, M., Mills, L. F., & Slemrod, J. B. (2005). An empirical examination of corporate tax noncompliance. Ross School of Business Paper(1025). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.891226

- Hanlon, M., & Slemrod, J. (2009). What does tax aggressiveness signal? Evidence from stock price reactions to news about tax shelter involvement. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1–2), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.09.004

- Heinemann, F., & Kocher, M. G. (2013). Tax compliance under tax regime changes. International Tax and Public Finance, 20(2), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9222–3

- Hermansyah, A. (2016, September 2). 38 countries have implemented tax amnesties: Expert. The Jakarta Post. Retrieved from https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/09/02/38-countries-have-implemented-tax-amnesties-expert.html

- Higgins, F. (2017, April 5). The Most Recent Argentine Tax Amnesty Makes the History Books. The Bubble. Retrieved from https://www.thebubble.com/the-most-recent-argentine-tax-amnesty-makes-the-history-books

- Huda, M. K., & Hernoko, A. Y. (2017). Tax amnesties in Indonesia and other countries: Opportunities and challenges. Asian Social Science, 13(7), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v13n7p52

- Indonesia. (2007). Ketentuan Umum dan Tata Cara Perpajakan (Perubahan Ketiga Atas Undang-Undang Nomor 6 Tahun 1983) (general provisions and taxation procedures).In R. Indonesia (Eds.), Vol. Nomor 28 Tahun 2007.

- Indonesia. (2008). Penegasan Pelaksanaan Pasal 37A Undang-Undang Ketentuan Umum dan Tata Cara Perpajakan Beserta Ketentuan Pelaksanaannya (affirmation of implementation Article 37A general laws and taxation procedures and the provisions of implementation).In D. G. O. Taxation (Eds.), Vol. SE34/PJ/2008.Taxation (Eds.), Vol. SE34/PJ/2008.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In L. C. MacLean & W. T. Ziemba (Eds.), Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 99–127). World Scientific.

- Kara, H. (2014). The Effects of Tax Amnesties on Tax Revenue and Shadow Economy in Turkey. Thesis (PhD). Middle East Technical University,

- Khuong, N. V., Liem, N. T., Thu, P. A., & Khanh, T. H. T. (2020). Does corporate tax avoidance explain firm performance? Evidence from an emerging economy. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1780101. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1780101

- Kourdoumpalou, S., & Karagiorgos, T. (2012). Extent of corporate tax evasion when taxable earnings and accounting earnings coincide. Managerial Auditing Journal, 27(3), 228–250. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686901211207474

- Mahestyanti, P., Juanda, B., & Anggraeni, L. (2018). The determinants of tax compliance in tax amnesty programs: Experimental approach. Etikonomi: Jurnal Ekonomi, 17(1), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.15408/etk.v17i1.6966

- Manzon, G. B.,sJr, & Plesko, G. A. (2002). The relation between financial and tax reporting measures of income. Tax L. Rev, 55(2), 175–214.

- Marandu, E. E., Mbekomize, C. J., & Ifezue, A. N. (2015). Determinants of tax compliance: A review of factors and conceptualisations. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 7(9), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v7n9p207

- Martani, D., Anwar, Y., & Dan Fitriasari, D. (2011). Book-tax gap: Evidence from Indonesia. China-USA Business Review, 10(4), 278–284. https://www.davidpublisher.com/Public/uploads/Contribute/5599fb36e2af4.pdf

- McKerchar, M. (2002). The effects of complexity on unintentional noncompliance for personal taxpayers in Australia. Austl. Tax F, 17, 3–26. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/austraxrum17&i=1

- Modica, E., Laudage, S., & Harding, M. (2018). Domestic Revenue Mobilisation: A New Database on Tax Levels and Structures in 80 Countries [Working Papers]. OECD Taxation Working Papers No. 36, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1787/a87feae8-en

- Nor, J. M., Ahmad, N., & Saleh, N. M. (2010). Fraudulent financial reporting and company characteristics: Tax audit evidence. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 8(2), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/19852511011088389

- OECD (2010). Tax compliance and tax accounting systems. Forum on Tax Administration. d oi:http://www.oecd.org/tax/administration/45045662.pdf

- OECD (2017). Aggressive tax planning indicators: Final report. OECD Taxation Papers: Working Paper No. 71 - 2017 (July 2018 ed.). Luxembourg: Institute for Advanced Studies

- OECD. (2018). The Concept of Tax Gaps: Corporate Income Tax Gap Estimation Methodologies. OECD Taxation Papers: Working Paper No. 73 - (July ed.). Retrieved from https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2018-07/tgpg-report-on-cit-gap-methodology_en.pdf

- OECD. (2020) . Revenue statistics in asian and pacific economies 2020 – Indonesia (2020).

- Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2020). Taxation. OurWorldInData.org. https://ourworldindata.org/taxation

- Pratama, A. (2020). Corporate governance, foreign operations and transfer pricing practice: The case of Indonesian manufacturing companies. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 24(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2020.105167

- Putri, I. D. A. D. E. (2015). Corporate profiling based on tax malfeasance attributes, empirical study on non-financial companies listed on Indonesia stock exchange during 2010-2013. Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta. Retrieved from https://lib.ui.ac.id/detail?id=20422699&lokasi=lokal

- Reuters. (2017). Brazil raises $517 mln in second round of tax amnesty program. (2017, August 3). Reuters.

- Richardson, M., & Sawyer, A. J. (2001). A taxonomy of the tax compliance literature: Further findings, problems and prospects. Austl. Tax F, 16(2), 137–284. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/austraxrum16&i=135

- Salihu, I. A., Annuar, H. A., & Obid, S. N. S. (2015). Foreign investors’ interests and corporate tax avoidance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 11(2), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2015.03.001

- Saraçoğlu, O. F., & Çaşkurlu, E. (2011). Tax amnesty with effects and effecting aspects: Tax compliance, tax audits and enforcements around; the Turkish case. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(7), 95–103. http://ijbssnet.com/view.php?u=http://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol._2_No._7;_Special_Issue_April_2011/11.pdf

- Sayidah, N., & Assagaf, A. (2019). Tax amnesty from the perspective of tax official. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1659909. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1659909

- Shi, A. A., Concepcion, F. R., Laguinday, C. M. R., Ong Hian Huy, T. A. T., & Unite, A. A. (2020). An analysis of the effects of foreign ownership on the level of tax avoidance across Philippine publicly listed firms. DLSU Business and Economics Review, 30(1), 1–14. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85090942791&partnerID=40&md5=a0d50d0264df5a495e702388c54d69aa

- Stauffer, C. (2017, January 3). Argentines declare $97.8 billion in tax amnesty: government Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-argentina-economy-amnesty-idUSKBN14M17A

- Surbakti, T. A. V. (2012). Pengaruh karakteristik perusahaan dan reformasi perpajakan terhadap penghindaran pajak di perusahaan industri manufaktur yang terdaftar di bursa efek Indonesia tahun 2008-2010.Universitas Indonesia. Fakultas Ekonomi.

- Sutrisno, T., & Dularif, M. (2020). National culture as a moderator between social norms, religiosity, and tax evasion: Meta-analysis study. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1772618

- Tambunan, R. (2015, 22 April). Mengupas Sunset Policy & Tax Amnesty, Senjata Kejar Target Pajak. Liputan 6. Retrieved from https://www.liputan6.com/bisnis/read/2217599/mengupas-sunset-policy-amp-tax-amnesty-senjata-kejar-target-pajak

- Tedds, L. M. (2010). Keeping it off the books: An empirical investigation of firms that engage in tax evasion. Applied Economics, 42(19), 2459–2473. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840701858141

- TheBubble. (2017). The most recent Argentine tax amnesty makes the history books. TheBubble. (2017, April 5).

- Tjen, C., & Abbas, Y. (2010). Tax amnesty effectiveness in developing countries: The analysis of sunset policy in Indonesia. In J. Mendel & J. Bevacqua (Eds.), International tax administration: Building bridges (pp. 274–297). CCH Australia Limited.

- Uchitelle, E. (1989). The effectiveness of tax amnesty programs in selected countries. Quarterly Review, 14(Aut), 48–53. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/quarterly_review/1989v14/v14n3article5.pdf

- Wahlund, R. (1992). Tax changes and economic behavior: The case of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Psychology, 13(4), 657–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(92)90017-2

- Wärneryd, K.-E., & Walerud, B. (1982). Taxes and economic behavior: Some interview data on tax evasion in Sweden. Journal of Economic Psychology, 2(3), 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(82)90003–4

- Wearing, A., & Headey, B. (1997). The would-be tax evader: A profile. Austl. Tax F, 13(1), 3–18. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/austraxrum13&i=5

- Winastyo, E. F. P. (2010). Efektivitas sunset policy dalam meningkatkan tingkat kepatuhan wajib pajak dan penerimaan pajak pada kantor pelayanan pajak pertama Jakarta sawah besar dua. Universitas Indonesia. Fakultas Ekonomi.

- Yuan, G., McIver, R., & Burrow, M. (2012, August). Tax regimes, regulatory change and corporate income tax aggressiveness in China. In 25th Australasian Finance and Banking Conference.