Abstract

The purpose of this study was twofold; (1) to establish the direct influence of Entrepreneurial competencies and Firm capability on SME Performance and (2) to examine the mediating role of Firm capability between Entrepreneurial competencies and SME Performance. A cross-sectional and explanatory design was utilized to collect and analyze data from 314 SMEs in Uganda. The sample size was proportionally distributed amongst three SME subsectors; manufacturing, trade, and restaurants. A positive and significant influence of entrepreneurial competencies and firm capabilities on SME performance was established. Among the seven entrepreneurial competencies understudy, innovative competency is highly associated with SME performance than other competencies. Interestingly, firm capabilities were found to be a powerful predictor of SME performance than entrepreneurial competencies. In addition, a partial and significant mediating role of firm capabilities was also found. Theoretically, the study provides maiden evidence of the indirect influence of a firm’s capabilities on the association between entrepreneurial competencies and SME performance. In practice, managers and SME owners should address their competency deficiencies to develop more capabilities like management and marketing capabilities which could enhance SME performance. The study provides initial evidence for the mediating role of firm capabilities in the association between entrepreneurial competencies and firm performance.

1. Introduction

Recent development in entrepreneurship research has paid increased attention to Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. This is due to the realization that SMEs play a significant role in economic growth and development (Eikelenboom & de Jong, Citation2019; Turyahebwa et al., Citation2013). The impact of SMEs on both developed and developing countries is considerable. Scholars like Asiimwe (Citation2017), observed that even the developed economies such as Europe and America heavily relied on SMEs to attain accelerated economic growth and rapid industrialization. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (Citation2019), SMEs employ about 45% of the labor force and remarkably contribute over 20% of Uganda’s total Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This is why globally SMEs play a pivotal role in the socio-economic development and poverty reduction in terms of employment generation, growth of GDP (Donkor et al., Citation2018; OECD, Citation2019), engines for innovation (Maldonado-Guzmán et al., Citation2019), income distribution, resources utilization (Hernández-Linares et al., Citation2021; Karami & Tang, Citation2019) and regional development (Donkor et al., Citation2018; Pucci et al., Citation2017).

On a good note, the global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM) reports that Uganda has the second-highest TEA (total entrepreneurial activity) index (31.6) among all the global entrepreneurship countries after Peru and the second-highest startups activity cited by (Abaho, Aarakit, Ntayi & Kisubi, Citation2017). However, the same report indicates that the country’s SME sector registers the worst performance among the GEM countries. To be specific, Orobia et al. (Citation2020) reveal that 30 percent of SMEs shut down before witnessing their third birthday. Relatedly, less than one-half of small start-ups exist for more than 5 years (OECD, Citation2019). Despite being the largest sector (80%) of the economy, due to its poor performance, the sector contributes only 20% to the national GDP (Turyahebwa et al., Citation2013) and only a fraction develop into the core group of high-performing firms (OECD, Citation2019).

Through a critical review of the empirical literature, several factors have been investigated concerning SME performance. For instance, innovative capability and strategic goals (Donkor et al., Citation2018) inventory management and managerial competencies (Orobia et al., Citation2020), transformational leadership and dynamic capabilities (Eikelenboom & de Jong, Citation2019), innovative capability dimensions (Maldonado-Guzmán et al., Citation2019; Saunila, Citation2020), dynamic capabilities and marketing orientation (Hernández-Linares et al., Citation2021), entrepreneurial orientation, networking capability and experiential learning (Karami & Tang, Citation2019), internal capabilities (Arshad & Arshad, Citation2019), board governance and intellectual capital (Nkundabanyanga, Citation2016) branding capability (Odoom et al., Citation2017), green supply chain adoption (Namagembe et al., Citation2019), firm capability and business model design (Pucci et al., Citation2017).

It has been observed that the majority of the studies provide evidence for contexts other than Uganda. A few that have used Ugandan evidence have concentrated on the financial performance of SMEs (Namagembe et al., Citation2019; Nkundabanyanga, Citation2016; Orobia et al., Citation2020) while (Osunsan et al., Citation2015; Sebikari, Citation2019) focused on direct effects. But given the nondisclosure tendencies of financial information and poor record-keeping by these firms, examining their financial performance could be difficult. As such, this study examined both the financial and non-financial performance of SMEs. We also did not find any study that explored the mediating role of firm capabilities between entrepreneurial competencies and SME performance. The only study found by Al Mamun et al. (Citation2016) focused on the direct influence of these variables. Therefore, evidence for a significant correlation between entrepreneurial competencies and SME performance exists (Barazandeh et al., Citation2015; Khalid & Bhatti, Citation2015; Ng et al., Citation2014; Sarwoko, Citation2016). There is also support for a significant and positive correlation between firm capabilities and firm performance (Donkor et al., Citation2018; Eikelenboom & de Jong, Citation2019; Maldonado-Guzmán et al., Citation2019). Relatedly, the dynamic capabilities theory which is an extension of the resource-based view (RBV) asserts that firm owners and/or managers’ entrepreneurial competencies have a strategic role to play in creating firm capabilities and improving performance (Ringov, Citation2017; Teece, Citation2014a).

According to Teece (Citation2014b), dynamic capabilities enhance the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments. Thus, entrepreneurial competencies play a critical function in creating firm capabilities which ultimately results in better SME performance (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000). Entrepreneurial competencies act as a driving force in the search for opportunities and resources for better firm performance (Colombo & Grilli, Citation2005; Vijay & Ajay, Citation2011). We, therefore, propose that while Entrepreneurial competencies and Firm capabilities individually explain the performance of Ugandan SMEs, the mechanism in which entrepreneurial competencies influence firm performance is enhanced through firm capabilities. The study makes two important contributions below;

Given the nature of SMEs in terms of resource constraints and owner-managed, their better performance largely depends on the owner’s/ managers’ entrepreneurial competencies. We, therefore, explored which of these competencies matter a lot in influencing firm performance. This would guide SME managers to focus on which competence gaps to give address priority. Secondly, the study provides initial empirical evidence on the indirect influence of firm capabilities on the association between entrepreneurial competencies and SME performance. It is a timely response to calls for investigations on the mechanisms through which entrepreneurial competencies influence firm performance (Orobia et al., Citation2020; Tehseen et al., Citation2019). The rest of the paper is structured in terms of theoretical and literature review in section 2, the methodology in section 3, results and discussion in section 4, 5 conclusions, 6 implications, and 7 limitations and future research direction in section.

2. Study context

Uganda is a landlocked country located in East Africa. It is edged by Kenya in the East, South Sudan in the North, the Democratic Republic of Congo in the west, Rwanda in the South-West, and Tanzania in the South (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, Citation2019). Uganda’s population is estimated at 41 million with a growth rate of 3.32 percent. This growth rate is influenced by the country’s fertility rate of 4.78 births per woman (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, Citation2019). At this growth, over one million people are added to the population each year. Uganda Bureau of Statistics categorizes these enterprises based on the number of employees, capital investment, and annual sales turnover. In quantitative terms, small enterprises are those businesses employing between 5 and 49 and have total assets between UGX: 10 million but not exceeding 100 million. The medium enterprise, therefore, employs between 50 and 100 with total assets of more than 100 million but not exceeding 360 million (Uganda investnebt Authority, Citation2019). For the purpose of this study, SMEs are those firms employing between 5 and 100 employees and have total assets between 10 million and 360 million shillings. SMEs are predominately in manufacturing, trade, service, and agriculture. The sector is composed of 1,100,000 enterprises, making it the largest in the country (Uganda Business Impact Survey, Citation2020). Thus, the country’s economy is predominately small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that constitute 90% of the private sector (Al Mamun et al., Citation2016). SMEs contribute above 20% of gross domestic product (GDP) and 80% of the manufactured output in Uganda (Al Mamun et al., Citation2016). These firms are regarded as key contributors to economic growth and transformation and create employment for Ugandans (Orobia et al., Citation2020). Though their contribution to the Ugandan economy is significant, SMEs have faced a persistent challenge of low performance, which has affected their survival. Literature attributes the poor performance of SMEs to a lack of opportunism, organizing ability, networking, relationship, commitment, execution, and innovative thinking (Man et al., Citation2002; Vijay & Ajay, Citation2011). However, it is unclear whether entrepreneurial competencies in terms of opportunism, organizing ability, networking, commitment, execution, and innovative thinking can be mediated by firm capabilities in order to realize better SME performance. It is against this backdrop that this study was called for.

3. Theoretical and empirical review

3.1. Dynamic capability theory

Dynamic capabilities encapsulate wisdom from earlier works on distinctive capabilities (Kay, Citation1993), organizational routine (Nelson & Winter, Citation1982), architectural knowledge (enderson & Clark, Citation1990), core competence (Prahalad & Hamel, Citation1997), core capability, and rigidity (Leonard‐Barton, Citation1992), combinative capability (Kogut & Zander, Citation1992) and architectural competence (Henderson & Cockburn, Citation1994). The dynamic capabilities theory builds on the RBV which asserts that resources and capabilities are the geneses of competitive advantage (arney, Citation2001). Further, RBV posits that resources are heterogeneously distributed across competing firms and are imperfectly mobile which, in turn, makes this heterogeneity persist over time (Barney, Citation1991; Barney et al., Citation2011). On the contrary, the theory of dynamic capabilities exhibits commonalities in resources across firms (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000; Teece, Citation2014a). However, such commonalities have not been systematically identified. Eisenhardt and Martin (Citation2000) define capabilities as the firm’s processes that use resources to integrate, reconfigure, gain and release resources to match or create market changes. Such capabilities can originate from entrepreneurial competencies at the individual level (Hwang et al., Citation2020) that are key in mobilizing more resources both within and outside the firm (creating firm capability) at the firm level (Teece, Citation2014b). Firm Capability gives the firm leverage to utilize resources efficiently and perform tasks or activities that generate a competitive advantage for the firm (Teece, Citation2014b). From a strategic point of view, a firm’s capability in terms of actions, processes, systems, and relationships define the firm's performance position and competitive edge in the market (Barney et al., Citation2011). As entrepreneurial competencies play a critical role in spotting the firm’s strategic opportunities and/or threats from the broad environment, the ability to implement such opportunities and manage environmental shocks lies in the firm’s capability (Barney & Arikan, Citation2001). As such, a firm’s capability focuses on strategy perception and implementation that generate better firm performance as a conduit for achieving competitive advantage (Wang et al., Citation2009). Thus, dynamic capabilities enhance the firm's ability to build, integrate and reconfigure its internal and external resources to adapt to the volatile environment (Khalil & Belitski, Citation2020). In addition, firms are able to innovate and cultivate change in their operations from which they derive better performance. To this end, it can be postulated that the efficiency of any SME in solving problems lies in the owner’s/manager’s entrepreneurial competencies and the firm’s ability to support the implementation of any interventions (Weinstein et al., Citation1999).

3.2. Entrepreneurial competencies and firm performance

Entrepreneurial competencies refer to the fundamental distinctiveness in terms of personality, motives, knowledge, social roles, skills, and self-images that result in new venture creation, venture sustainability, and performance (Bird, Citation1995), while Khalid and Bhatti (Citation2015) define entrepreneurial competence as the managerial capability to create and communicate a strategic vision for structuring firms’ systems for better performance. According to Man (Citation2001), seven entrepreneurial competencies are identified that are opportunity, networking, relationship, commitment, execution, innovative thinking, and organizational ability as essential for SME performance. Substantial empirical evidence exists to support the positive and significant influence of entrepreneurial competencies on firm performance, for instance, g et al. (Citation2016) studied owner-managed SMEs in Malaysia. Similarly, Khalid and Bhatti (Citation2015) established the same effect between entrepreneurial competencies and overall firm performance among exporting firms. For more empirical evidence, (see Ahmad et al., Citation2018; Hwang et al., Citation2020; Ibidunni et al., Citation2021; Al Mamun et al., Citation2016; Orobia et al., Citation2020). To this end, it is argued that SMEs with managers who have high levels of entrepreneurial competencies tend to scan and manage the environment in which they operate to find new opportunities and consolidate their competitive positions. As such, better SME performance is believed to occur when managers/owners have the relevant competencies that are required by their firms (Bird, Citation2019). Furthermore, Bird (Citation2019) claims that the competencies required to launch a business (baseline competencies) are different from those required for better firm performance, survival, and growth. This is an explanation of why Uganda is excelling at firm startups as well as failure. As such, there is a need to acknowledge that additional competencies are necessary to enhance superior performance among SMEs. This resonates with Hwang et al. (Citation2020) assertion that entrepreneurial competencies in the form of technical and management knowledge and skills are critical in shaping the performance of any firm. Similarly, according to Ahmad et al. (Citation2018) execution and network competencies had significant positive association with firm performance among women owned firms in Malaysia. We, therefore, hypothesized that

H1 Entrepreneurial competencies and SME performance are positively related

3.3. Firm capabilities and firm performance

Most of the empirical studies have found a positive and significant relation between firm capabilities and performance for example (Arshad & Arshad, Citation2019; DeSarbo et al., Citation2007; Al Mamun et al., Citation2016; Pucci et al., Citation2017). A review of recent publications further indicates that different types of firm capabilities positively influence different performance dimensions. For instance, dynamic capabilities and export performance (Ribau et al., Citation2017), brand capability and general SME performance (Odoom et al., Citation2017), innovative capability and financial performance (Donkor et al., Citation2018; Ribau et al., Citation2017), firm capability and export performance (Krammer et al., Citation2018), networking capability and SME international performance (Karami & Tang, Citation2019), dynamic capability and SME sustainable performance (Eikelenboom & de Jong, Citation2019). To expand, Kamboj and Rahman (Citation2015) performed a meta-analytical review of 101 papers published between 1987 and 2014 and the results show that marketing capabilities positively affect firm performance. An earlier study by Tuan and Yoshi (Citation2010) of 102 industries in Vietnam found that firm capabilities are sources of competitive advantage that enhance firm performance in terms of sales and market share growth. Thus, if managers or owners evoke changes in their organizational capabilities such as marketing, market linking, and management capabilities (DeSarbo et al., Citation2007) it is these changed organizational attributes that are deemed to evoke improved worker well-being, worker behavior, efficiency that in the end, leads to higher customer acquisition and profitability (Eikelenboom, Citation2005; He et al., Citation2009). These tangible and intangible assets and resources are perceived as a “vehicle” for strategy implementation (Barney et al., Citation2011), rent-generating assets (Mithas et al., Citation2011) and they enable firms to earn above normal returns (Odoom et al., Citation2017). We, therefore, proposed that

H2 Firm capabilities and SME performance are positively related

3.4. Entrepreneurial competencies, firm capabilities, and SME performance

Entrepreneurial competencies influence firm performance in either a direct or indirect manner. Therefore, business owners/managers need to possess the opportunity, organizing, relationship building, commitment, and networking competencies to create organizational ability to perform a coordinated task to improve the competitive scope of the firm (Sánchez, Citation2012). SMEs have limited resources (capabilities) as compared to their counterparts (Chittithaworn et al., Citation2011; Eikelenboom & de Jong, Citation2019; Maldonado-Guzmán et al., Citation2019) this implies that these firms generate their capabilities from the competencies of its owners or managers (Al Mamun et al., Citation2016). Although firm capabilities such as marketing, market linking, and management capabilities (DeSarbo et al., Citation2007) determine firm performance, they are influenced by entrepreneurial competencies (Man et al., Citation2002; Monteiro et al., Citation2019). Organizing competencies call for the ability to lead, control, monitor, organize, and develop external and internal resources from different areas to create a firm’s capabilities (Man, Citation2001; Vijay & Ajay, Citation2011). On the other hand, the entrepreneur’s ability to set goals has to be embarked by the firm’s capabilities to take action in the realization of the set goals. Hwang et al. (Citation2020) suggest that the impact of managerial abilities on firm performance needs to be examined through firm capabilities due to the higher influence than the direct relationship. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed;

H3 Entrepreneurial Competencies and Firm Capabilities are positively related

H4 Firm Capabilities mediate the relationship between Entrepreneurial Competencies and SME Performance

4. Methodology

4.1. Design, population, sample, and data collection

The study adopted a cross-sectional and explanatory research design to collect and analyze data. The study population is composed of 1,724 SMEs operating in trade (1369), hotel and restaurant sector (128), and manufacturing sector (227) in Jinja city census of business establishment report UBOS (2017/2018). Using Yamane's (Citation1973) formula, a sample of 314 SMEs was determined and was proportionately distributed among the sectors; 249 trading SMEs, 23 restaurants, and 41 manufacturing SMEs. Out of the 314 questionnaires distributed, 257 usable questionnaires were returned and free from errors, giving a response rate of 81.2%.

4.2. Measurement of variables

Entrepreneurial competencies were operationalized in terms of opportunism, organizing ability, networking, relationship, commitment, execution, and innovative thinking (Man et al., Citation2002; Vijay & Ajay, Citation2011). Firm capabilities were measured following DeSarbo et al. (Citation2007) dimensions which are marketing, market linkage, and management capabilities, while SME performance was measured using both financial and non-financial indicators. Sales growth, profitability, and market share as financial measures (Eikelenboom, Citation2005; Mithas et al., Citation2011) were customer acquisition and retention were nonfinancial indicators (Pont & Shaw, Citation2003). All variables had a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient and CVI above 0.6 thresholds as recommended by (Nunnally, Citation1978)

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Descriptive statistics

Results from reveal that the percentage of businesses that were registered (47.9%) was slightly lower than those that are not registered (52.1%). These results indicate that a relatively bigger percentage of SME owners/managers have not yet taken the registration of their businesses seriously. Concerning ownership, the majority (78.2%), were Sole Proprietorships, followed by partnerships (17.9%) and then limited companies (3.9%). From these findings, we observe that most business owners in Jinja would rather start a business alone than teaming up with others. It has also been revealed that 53.7% of the firms have been in operation for 5–10 years, 29.6% for over 10 years and 16.7% for Less than 5 years. On the same note, the majority of the SMEs 90.7% employ 5–49 employees, whereas 9.3% of the SMEs employ 50–99 employees. Furthermore, the majority 74.7% of the SMEs deal in trade followed by manufacturing 16.3%, and the minority 8.9% of businesses were hotels and restaurants. It is also observed that for most SMEs 71.6% turnover is between 12 million and 360 million while 23.3% make over 360 million and the least businesses (5.1%) their annual sales are below 12 million. Lastly, findings reveal that the biggest percentage of businesses studied (59.1%) own assets value of between12-360 million, 37.0% own assets worth over 360 million while only 3.9% of the SMEs have accumulated assets below 12 million.

Table 1. SME profiles

5.2. Correlation results

Results in indicate that Entrepreneurial Competencies and SME Performance were found to be positively and significantly related (r = .460, p < .01). These results demonstrate that where SME owners have competencies of spotting and exploiting opportunities, they would promptly deal with challengesthus, and their businesses are more likely to attain higher levels of sales. It is also noted that Innovative Thinking (r = .409, p < .01) and Relationship Building (r = .405, p < .01) have the strongest relationship with SME Performance compared to other Entrepreneurial Competencies. Therefore, managers and entrepreneurs who are innovative and can build relationships can acquire and retain more customers. It is also reported that firm capabilities and SME Performance are positively related (r = .520, p < .01). These results indicate that when the firm has effective pricing and advertising programs, the performance of these firms in terms of sales, profitability, and market share will greatly improve. Lastly, correlation results reveal a significant positive relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and firm capabilities (r = .570, p < .01). Similarly, the relationships between the dimensions of entrepreneurial competencies; opportunity (r = .251, p < .01) commitment (r = .262, p < .01), organizing (r = .273, p < .01) executing (r = .263, p < .01) innovative thinking (r = .507, p < .01) networking (r = .383, p < .01) and relationship building (r = .442, p < .01) is positive and significant. This signifies that when managers/enterprise owners possess entrepreneurial competencies, this would enhance firm capabilities in form of management, marketing, and market linking.

Table 2. Pearson correlations/zero order matrix

5.3. Regression results

Linear regression results presented in show that Entrepreneurial Competencies and Firm Capabilities can explain 30.9% of the variance in SME Performance (R Square = .309). This implies that a change in entrepreneurial competencies and firm capabilities would cause a 30.9% change in SME performance. The most significant predictor of SME performance was firm capabilities (β = .382, t = 5.985, P. <.01) followed by entrepreneurial competences (β = .241, t = 3.777, Sig. <.01). The regression model was statistically significant (F statistic = 56.674, p < .001). The VIF values for all the study variables were less than 4.00, indicating that the data had no multicollinearity problems.

Table 3. Regression results

5.3.1. Mediation results

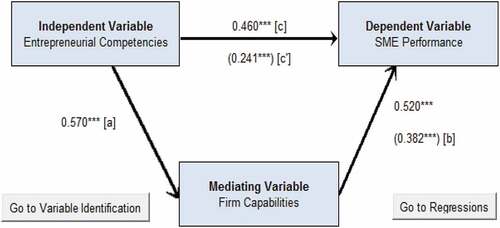

The path model proposed by Turyahebwa et al. (Citation2013) was used to explain the mediating role of firm capabilities in the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and SME performance as shown in . To fully understand the mediating role of firm capabilities in the relationship between Entrepreneurial Competencies and SME Performance, the approach suggested by Dr Jose Paul was used to execute this and the results were presented using the two models by taking into account the following conditions; a.) The Entrepreneurial Competency is a significant predictor of Firm Capabilities, b.) Firm Capabilities and SME Performance are positively related. Regression coefficients were used and entered into the Med Graph Software. The Sobel Z-value included shows that the mediation is significant (p < .01). Considering the Sobel Z-value of 5.271 and the existence of both direct and indirect effect values which were .241 and .217 respectively, it was concluded that the Firm Capabilities play a complementary mediating role in the relationship between Entrepreneurial Competencies and SME Performance.

Table 4. Mediation effect of firm capabilities

shows that when firm capabilities were introduced in the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and SME performance, the standardized beta (β) for the relationship reduced from 0.460 to 0.241, this confirms the indirect influence of firm capabilities between entrepreneurial competencies and SME performance. However, since the direct effect remained significant, it depicts a partial mediation. A ratio index (i.e. indirect effect/total effect) of 47.3% given by (0.217/0.460*100) was computed (see, ). This indicates that 47.3% of the effect of entrepreneurial competencies on SME Performance goes through firm capabilities, while 52.7% is a direct effect. To sum up, the total effect of entrepreneurial competencies on SME performance through firm capabilities (β = .520, P. <.001) which is higher than the total direct effect (β = .460, P. <.001).

5.4. Discussion

Drawing on the dynamic capability theory, the study investigated the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and firm capabilities on SME performance, and also examined the mediating role of firm capabilities in this association. The study established that entrepreneurial competencies such as opportunism, organizing ability, networking, relationship, commitment, execution, and innovative thinking have a positive correlation with SME performance thus supporting H1. This implies that when SME owners/managers can spot opportunities, innovate, network, and build relationships with different stakeholders; this would enhance the performance of their firms. A plausible explanation for such results could be due to the fact that SME managers in Uganda rely on their networks to establish long-term relations with their clients and other stakeholders which improve the performance of their firms. Our findings are consistent with the earlier establishment of a positive and significant relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and firm performance (Ahmad et al., Citation2018; Barazandeh et al., Citation2015; Hwang et al., Citation2020; Al Mamun et al., Citation2016).

Our results also revealed that firm capabilities significantly influence firm performance (supporting H2). This is an indication that as a firm gains more capabilities in form of management and marketing capabilities, their performance would greatly improve. For instance, marketing capabilities would enable firms to acquire and retain customers whilst management capabilities would aid in professionalization and formalizing firm operations. Thus, these capabilities would result in better sales, market share, and profits. Our results corroborate with J. B. Barney (Citation2001) assertion that firms that possess and control pool capabilities are in a better performance position compared to their counterparts. Related, Krammer et al. (Citation2018) argue that exporting firms that utilize their internal capabilities employee skills, better technologies realize better export performance. Furthermore, Kamboj and Rahman (Citation2015) explain that for firms to realize superior performance in this complex environment, there is a need to develop and efficiently use their capabilities especially marketing capabilities. More studies have established a positive and significant correlation between capabilities and firm performance (Eikelenboom & de Jong, Citation2019; Hernández-Linares et al., Citation2021; Karami & Tang, Citation2019; Saunila, Citation2020). Leveraging on the dynamic capability theory, firm Capability enhances the firm’s ability to utilize resources efficiently and perform tasks or activities that generate better performance (Teece, Citation2014b)

Regarding H3 a positive and significant association was established between Entrepreneurial Competencies and Firm Capabilities hence being supported. This suggests that when SME owners/managers are competent enough, firms are most likely to have capabilities in terms of management, marketing, and market linking and this would enhance their performance through efficiency in their operations. Entrepreneurial competencies like networking competence enable managers to mobilize and beef up the firm’s internal capabilities like recent technologies through external linkages. Therefore, despite the commonalities in firm resources as assumed by the theory, differences in performance are brought out by their ability to integrate, reconfigure, gain and utilize these resources to create market value (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000). The findings resonate with Hwang et al. (Citation2020), they also found that entrepreneurial competencies in the form of managerial skills and technical knowledge have a significant influence on competitive advantage. This is in line with the argument that intangible resources like competencies contribute to the advancement in the firm’s capabilities (Monteiro et al., Citation2019).

Lastly, our findings also support H4 which suggests that firm capability mediates Entrepreneurial Competencies and Firm Performance. More interestingly, the impact of entrepreneurial competencies on firm performance is much higher through firm capability than the direct influence. This suggests that firm capability is a conduit through which entrepreneurial competencies enhance firm performance. The mediating results of firm capability are consistent with the findings of Hwang et al. (Citation2020) who found that the indirect influence of entrepreneurial competencies on competitive advantage via firm innovation capabilities was stronger than their direct effects. As Monteiro et al. (Citation2019) also established that dynamic capabilities mediate the correlation of intangible resources and export performance of Portuguese companies. Also, Karami and Tang (Citation2019) establish a full mediating impact of networking capabilities between entrepreneurial orientation and the international performance of SMEs.

6. Conclusion, implications and research direction

6.1. Conclusion

From the results of this study, it can be concluded that SME Performance can be improved by enhancing entrepreneurial competencies and firm capabilities. This could be done at individual level by entrepreneurs or managers taking advantage of any training opportunities through which skills and knowledge are attained or through specialized sector trainings organized by authorities like ministry of trade, industry and cooperatives. It’s evident that when entrepreneurs possess competencies such as innovative thinking, networking, and relationship building, their business performance tends to improve. Therefore entrepreneurs/managers need to attain such competencies as a way to spur improved SME performance. This will also fuel the accumulation of firm capabilities given the fact that SMEs are resource constraints. This suggests that entrepreneurs with high networking, relationship building, and innovative thinking competencies able to create firm capabilities in form of marketing, market linking, and management capabilities. To sum up, the significant contribution of this study is the mediating role of firm capability. It is revealed that the where these managers focus on building the overall firm capability as a conduit to promote SME performance, firms perform better than through the direct effect of entrepreneurial competencies.

6.2. Theoretical and practical contributions

This study provides both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, the study contributes to the body of literature concerning the direct influence of entrepreneurial competencies and firm capabilities on firm performance. Moreover, the study provides maiden evidence on the indirect influence of firm capabilities which is rare in the literature. Though there exists the direct relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and firm capabilities, the mechanisms under which entrepreneurial competencies influences firm performance are under research. The study fills this gap by revealing that such mechanisms greatly influence firm performance as compared to the direct effects. For managers and entrepreneurs, since entrepreneurial competencies contribute to both firm capabilities and performance, managers and SME owners should address their competency deficiencies to develop more capabilities like management and marketing capabilities which could enhance better SME performance. To be specific, they should pay special attention to building networks through which they are exposed, learn and become more innovative as well as better decision makers and implementers.

6.3. Limitations and research direction

Despite the significant contribution of this paper, it also presents some limitations and opportunities for future researchers. First, the study examined firm performance in terms of financial and market performance. Therefore, future research can examine SME performance by focusing on the environmental and social performance of these firms. We also did not explore the unique contribution of firm capability and entrepreneurial competencies dimensions on firm performance. As such, we could not establish which entrepreneurial competencies and firm capabilities dimensions explain more firm performance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Moses Kisame Kisubi

Moses Kisame Kisubi is a Ph.D. candidate at Moi University and a lecturer at Makerere University Business School Uganda, Jinja regional campus. Moses has experience of about ten years in teaching, business, and research.

Francis Aruo

Francis Aruo is lecturer in the Department of Marketing and Management – Makerere university business school – Jinja Regional Campus. He has a teaching experience of more than years. His research interest lies in the areas women and community entrepreneurship and Small Medium Enterprises

Aziz Wakibi

Lecturer in the Department of Marketing and Management Makerere University Business School – Jinja Regional Campus and a PhD candidate at Makerere University

Veronica Mukyala

She is the director Makerere University School Jinja Regional Campus and finalizing with her PhD at Moi University in Kenya. Veronica has published a good number of research papers in the areas of finance, accounting and governance.

Kassim Ssenyange

Kassim is lecturer in the Department of Marketing and Management at Makerere University Business School – Jinja Regional Campus. I am passionate with research especially in areas of management, project, marketing, and entrepreneurship and operations. Currently, he is finalizing with his PhD in project management at the University of South Africa.

References

- Abaho, E., Aarakit, S., Ntayi, J., & Kisubi, M. (2017). Firm capabilities, entrepreneurial competency and performance of Ugandan SMEs. Business Management Review, 19(2), 105–16. http://hdl.handle.net/11159/3229

- Ahmad, N. H., Suseno, Y., Seet, P.-S., Susomrith, P., & Rashid, Z. (2018). Entrepreneurial competencies and firm performance in emerging economies: A study of women entrepreneurs in Malaysia Knowledge, learning and innovation (pp. 5–26). Springer.

- Al Mamun, A., Nawi, N. B. C., & Zainol, N. R. B. (2016). Entrepreneurial competencies and performance of informal micro-enterprises in Malaysia. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 7(3), 273. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n3p273

- Arshad, M., & Arshad, D. (2019). Internal capabilities and SMEs performance: A case of textile industry in Pakistan. Management Science Letters, 9(4), 621–628. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.1.001

- Asiimwe, F. (2017). Corporate governance and performance of SMEs in Uganda. International Journal of Technology and Management, 2(1), 14. http://ijotm.utamu.ac.ug/

- Barazandeh, M., Parvizian, K., Alizadeh, M., & Khosravi, S. (2015). Investigating the effect of entrepreneurial competencies on business performance among early stage entrepreneurs global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM 2010 survey data). Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-015-0037-4

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Barney, J. B. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 41–56. http://www.bus.tu.ac.th/usr/sab/articles_pdf/research_articles/rbv_barney_web.pdf

- Barney, J. B., & Arikan, A. M. (2001). The resource-based view: Origins and implications. The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management, 5, 124–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/b.9780631218616.2006.00006.x

- Barney, J. B., Ketchen, D. J., Jr, Wright, M., Barney, J. B., Ketchen, D. J., & Wright, M. (2011). The future of resource-based theory: Revitalization or decline? Journal of Management, 37(5), 1299–1315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310391805

- Bird, B. (1995). Towards a theory of entrepreneurial competency. JA Katz RH Brockhaus (red.), Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence and growth. JAI Press, Greenwich. 51 - 72.

- Bird, B. (2019). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial competency Seminal ideas for the next twenty-five years of advances. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Chittithaworn, C., Islam, M. A., Keawchana, T., & Yusuf, D. H. M. (2011). Factors affecting business success of small & medium enterprises (SMEs) in Thailand. Asian Social Science, 7(5), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v7n5p180

- Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2005). Founders’ human capital and the growth of new technology-based firms: A competence-based view. Research Policy, 34(6), 795–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.03.010

- DeSarbo, W. S., Di Benedetto, C. A., & Song, M. (2007). A heterogeneous resource based view for exploring relationships between firm performance and capabilities. Journal of modelling in management. https://doi.org/10.1111/b.9780631218616.2006.00006.x

- Donkor, J., Donkor, G. N. A., Kankam-Kwarteng, C., & Aidoo, E. (2018). Innovative capability, strategic goals and financial performance of SMEs in Ghana. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(2), 238–254. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-10-2017-0033

- Eikelenboom, B. (2005). Organizational capabilities and bottom line performance: The relationship between organizational architecture and strategic performance of business units in Dutch headquartered multinationals. Eburon Uitgeverij BV.

- Eikelenboom, M., & de Jong, G. (2019). The impact of dynamic capabilities on the sustainability performance of SMEs. Journal of Cleaner Production, 235, 1360–1370. Eburon Uitgeverij BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.07.013

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10‐11), 1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E

- He, J., Mahoney, J. T., & Wang, H. C. (2009). Firm capability, corporate governance and competitive behaviour: A multi-theoretic framework. International Journal of Strategic Change Management, 1(4), 293–318. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSCM.2009.031408

- Henderson, R. M., & Clark, K. B. (1990). Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393549

- Henderson, R., & Cockburn, I. (1994). Measuring competence? Exploring firm effects in pharmaceutical research. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150906

- Hernández-Linares, R., Kellermanns, F. W., & López-Fernández, M. C. (2021). Dynamic capabilities and SME performance: The moderating effect of market orientation. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(1), 162–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12474

- Hwang, W.-S., Choi, H., & Shin, J. (2020). A mediating role of innovation capability between entrepreneurial competencies and competitive advantage. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 32(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2019.1632430

- Ibidunni, A. S., Ogundana, O. M., & Okonkwo, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial Competencies and the Performance of Informal SMEs: The Contingent Role of Business Environment. Journal of African Business, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2021.1874784

- Kamboj, S., & Rahman, Z. (2015). Marketing capabilities and firm performance: Literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 64(8), 1041–1067. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-08-2014-0117

- Karami, M., & Tang, J. (2019). Entrepreneurial orientation and SME international performance: The mediating role of networking capability and experiential learning. International Small Business Journal, 37(2), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242618807275

- Kay, J. (1993). The structure of strategy. Business Strategy Review, 4(2), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8616.1993.tb00049.x

- Khalid, S., & Bhatti, K. (2015). Entrepreneurial competence in managing partnerships and partnership knowledge exchange: Impact on performance differences in export expansion stages. Journal of World Business, 50(3), 598–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.01.002

- Khalil, S., & Belitski, M. (2020). Dynamic capabilities for firm performance under the information technology governance framework. European Business Review, 32(2), 129–157. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-05-2018-0102.

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.383

- Krammer, S. M., Strange, R., & Lashitew, A. (2018). The export performance of emerging economy firms: The influence of firm capabilities and institutional environments. International Business Review, 27(1), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.07.003

- Leonard‐Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 13(S1), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250131009

- Maldonado-Guzmán, G., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Pinzón-Castro, S. Y., & Kumar, V. (2019). Innovation capabilities and performance: Are they truly linked in SMEs? International Journal of Innovation Science, 11(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-12-2017-0139

- Man, W. Y. T. (2001). Entrepreneurial competencies and the performance of small and medium enterprises in the Hong Kong services sector. Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Hong Kong).

- Man, T. W., Lau, T., & Chan, K. (2002). The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises: A conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00058-6

- Mithas, S., Ramasubbu, N., & Sambamurthy, V. (2011). How information management capability influences firm performance. MIS quarterly. 237–256. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sis_research/219

- Monteiro, A. P., Soares, A. M., & Rua, O. L. (2019). Linking intangible resources and entrepreneurial orientation to export performance: The mediating effect of dynamic capabilities. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 4(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2019.04.001

- Namagembe, S., Ryan, S., & Sridharan, R. (2019). Green supply chain practice adoption and firm performance: Manufacturing SMEs in Uganda. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 30(1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-10-2017-0119

- Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). The Schumpeterian tradeoff revisited. The American Economic Review, 72(1), 114–132. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1808579

- Ng, K. S., Ahmad, A. R., & Ibrahim, N. N. (2014). Entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurship career intention. Case at a Malaysian Public University.

- Ng, H. S., Kee, D. M. H., & Ramayah, T. (2016). The role of transformational leadership, entrepreneurial competence and technical competence on enterprise success of owner-managed SMEs. Journal of General Management, 42(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/030630701604200103

- Nkundabanyanga, S. K. (2016). Board governance, intellectual capital and firm performance. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 32(1), 20–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-09-2014-0020

- Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd edit.) mcgraw-hill. Hillsdale, NJ, 416. 387-405.

- Odoom, R., Agbemabiese, G. C., Anning-Dorson, T., & Mensah, P. (2017). Branding capabilities and SME performance in an emerging market: The moderating effect of brand regulations. Marketing Intelligence & Planning.

- OECD. (2019). OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship Strengthening SMEs and Entrepreneurship for Productivity and Inclusive Growth OECD 2018 Ministerial Conference on SMEs: OECD Publishing.

- Orobia, L. A., Nakibuuka, J., Bananuka, J., & Akisimire, R. (2020). Inventory management, managerial competence and financial performance of small businesses. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 10(3), 379–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-07-2019-0147

- Osunsan, O. K., Kinyatta, S., Baliruno, J. B., & Kibirige, A. R. (2015). Age and performance of small business enterprises in Kampala, Uganda. International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research, 3(1), 189–196. ISSN 2348-3164

- Pont, M., & Shaw, R. (2003). Measuring marketing performance: A critique of empirical literature. Paper presented at the ANZMAC 2003: a celebrations of Ehrenberg and Bass: marketing discoveries, knowledge and contribution, conference proceedings.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Hamel, G. (1997). The core competence of the corporation Strategische Unternehmungsplanung/Strategische Unternehmungsführung (pp. 969–987). Springer.

- Pucci, T., Nosi, C., & Zanni, L. (2017). Firm capabilities, business model design and performance of SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(2), 222–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-09-2016-0138

- Ribau, C. P., Moreira, A. C., & Raposo, M. (2017). SMEs innovation capabilities and export performance: An entrepreneurial orientation view. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 18(5), 920–934. https://doi.org/10.3846/16111699.2017.1352534

- Ringov, D. (2017). Dynamic capabilities and firm performance. Long Range Planning, 50(5), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.02.005

- Sánchez, J. (2012). The influence of entrepreneurial competencies on small firm performance. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 44(2), 165–177. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rlps/v44n2/v44n2a14.pdf

- Sarwoko, E. (2016). Growth strategy as a mediator of the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and the performance of SMEs. Journal of Economics, Business & Accountancy, 19(2), 219–226. http://digilib.mercubuana.ac.id/manager/t!@file_artikel_abstrak/Isi_Artikel_557262529637.pdf

- Saunila, M. (2020). Innovation capability in SMEs: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 5(4), 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2019.11.002

- Sebikari, K. V. (2019). Entrepreneurial performance and small business enterprises in Uganda. International Journal of Social Sciences Management and Entrepreneurship (IJSSME), 3(1), 162 - 171. http://mail.sagepublishers.com/index.php/ijssme/article/viewFile/41/43

- Teece, D. J. (2014a). A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(1), 8–37. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.54

- Teece, D. J. (2014b). The foundations of enterprise performance: Dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(4), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0116

- Tehseen, S., Ahmed, F. U., Qureshi, Z. H., Uddin, M. J., & Ramayah, T. (2019). Entrepreneurial competencies and SMEs’ growth: The mediating role of network competence. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 11(1), 2–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-05-2018-0084

- Tuan, N. P., & Yoshi, T. (2010). Organisational capabilities, competitive advantage and performance in supporting industries in Vietnam. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 15(1), 1–21. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yoshi-Takahashi/publication/44035889_ORGANISATIONAL_CAPABILITIES_COMPETITIVE_ADVANTAGE_AND_PERFORMANCE_IN_SUPPORTING_INDUSTRIES_IN_VIETNAM/links/0fcfd5137f91789a5f000000/ORGANISATIONAL-CAPABILITIES-COMPETITIVE-ADVANTAGE-AND-PERFORMANCE-IN-SUPPORTING-INDUSTRIES-IN-VIETNAM.pdf

- Turyahebwa, A., Sunday, A., & Ssekajugo, D. (2013). Financial management practices and business performance of small and medium enterprises in western Uganda. African Journal of Business Management, 7(38), 3875–3885.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. (2019). “Statistical abstract”. Uganda Bureau of Statistics. https://www.ubos.org/publications/statistical/

- Uganda Business Impact Survey. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on formal sector small and medium enterprises. Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

- Uganda Investment Authority. (2017). Annual Investment Abstract 2016/17; https://www.ugandainvest.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/UIA-ANNUAL-INVESTMENT-ABSTRACT_FY-2016_2017.pdf

- Vijay, L., & Ajay, V. (2011). Entrepreneurial Competency in SME? S. Bonfring International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management Science, Special Issue Inaugural special issue), 05-10, 1. http://www.journal.bonfring.org/papers/iems/volume1/BIJIEMS-01-1002.pdf

- Wang, H. C., He, J., & Mahoney, J. T. (2009). Firm-specific knowledge resources and competitive advantage: The roles of economic- and relationship-based employee governance mechanisms. Strategic Management Journal, 30(12), 1265–1285. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.787

- Weinstein, O., Azoulay, N., Gavrilov, V., Rosenthal, G., & Lifshitz, T. (1999). Firms’capabilities and Organizational Learning A critical survey of some literature. 21(5), 544–546. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-199910000-00010

- Yamane, T. (1973). Statistics: An introductory analysis (3rd ed.). Harper and Row.