Abstract

Previous literature which examined relationship between fraud risk factors and occupational frauds occurrence is limited to the setting of a single developed country. This study aims to bridge this gap by examining the moderating role of ethical culture in affecting the relationship between fraud risks and occupational fraud using the sample of regional development banks (RDB) in one of the major developing countries, Indonesia. Our study employs Indonesian RDBs due to their economic significance and their exposure to a higher risk of occupational fraud. Primary data was collected using a survey method involving 355 employees from the 15 largest RDBs in Indonesia. The collected data was analyzed using the Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). We find that occupational fraud in RDBs is associated with opportunity and pressure. A strong ethical culture can weaken the positive relationship between these two fraud risks and occupational fraud. The findings of our paper imply that organizations that face a significant risk of fraud, such as RDBs, should invest in strengthening the organizations’ ethical culture as it could mitigate two out of four fraud risk factors. This study contributes towards development of the fraud diamond theory by examining the effect of ethical culture in mitigating fraud risk in the banking industry which is growing rapidly in a developing economy. This study focuses on a context that has still only been analyzed by previous research to a limited degree, namely RDBs which are known as the “second sector” of the banking industry in Indonesia.

1. Introduction

Fraud remains one of the main challenges for businesses around the world. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) conducted a survey titled the Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey in 2020 and found that 47% of the 5,000 respondents had experienced fraud within the previous 24 months (PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC), Citation2020). This figure represented the second-highest figure in the incidence of fraud in the last 20 years and the financial services industry, including banking, represented one of the sectors that were significantly affected by fraud. Likewise, a survey by the Association of Certified Examiners (ACFE) laid out in the Report to Nations 2020: Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, showed that banking and financial services are the biggest victims of occupational fraud, with 386 cases or 15.41% of the total fraud cases (ACFE, Citation2020). Indonesia is one of the countries that experienced a significant number of fraud cases which ranked among the highest in the Asia-Pacific region according to the ACFE survey.

The impact of fraud on the banking industry is greater than it is on other industrial sectors due to the financial nature of the industry (Suh et al., Citation2019; Suh & Shim, Citation2020). Banking institutions are more vulnerable to the risk of fraud because banks have large amounts of financial assets and it is the main motivation of fraud perpetrators to obtain financial benefits. Thus, employees working in banking institutions are more exposed to fraud risk factors that could lead them to commit fraud. White-collar crimes in the banking sector undermine public confidence in the financial sector and pose systemic risks to the national economy (Suh et al., Citation2018; Valukas, Citation2010). Fraud in the banking industry harms all bank stakeholders, not only the banks themselves (Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Mangala & Soni, Citation2022). Regional development banks (RDBs) represent a sizeable part of the Indonesian banking system as they own 8.60% of the total assets of all Indonesian commercial banks (Financial Services Authority, 2021). Our study employs Indonesian RDBs due to their economic significance and their exposure to a higher risk of fraud due to weaknesses in governance and internal control (Akyuwen et al., Citation2019).

The adverse impact of fraud on the banking sector has led researchers to investigate what factors drive perpetrators to commit fraud and how to mitigate them (Said et al., Citation2017; Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Asmah et al.; Citation2019; Younus, Citation2021; Suh et al., Citation2018; Suh & Shim, Citation2020; Suh et al., Citation2019; Hidajat, Citation2020; Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021; Repousis et al., Citation2019; Mangala & Soni, Citation2022; Aladwan, Citation2022; Murthy & Gopalkrishnan, Citation2022a; Chen et al., Citation2022). These previous studies have generally focused on the causes (fraud risk factors) in the banking sector based on the fraud triangle theory (FTT) and fraud diamond theory (FDT). However, these findings are inconclusive. Avortri and Agbanyo (Citation2021) and Kazemian et al. (Citation2019) found that pressure had a positive effect on the occurrence of fraud but Said et al. (Citation2017) found that pressure had no significant effect on fraud while Sunardi and Amin (Citation2018) provided empirical evidence that pressure mitigates fraud.

The influence of fraud risks that exist at the individual level on occupational fraud may vary depending on the ethical culture of the organization where the employee works. Prior literature found that ethical culture could represent a moderating variable because it weakened the influence of fraud risk factors on occupational fraud (Albrecht et al., Citation2015; Dorminey et al., Citation2012; Ocansey & Ganu, Citation2017; Suh & Shim, Citation2020). Ethical culture could assist in the prevention of fraud because individuals in organizations do not exist in a vacuum. An individual’s behavior, including the tendency to commit fraud, is influenced by the organizational context in which they work (Maulidi, Citation2022; Ocansey & Ganu, Citation2017; Suh & Shim, Citation2020).

This study focuses on occupational fraud because fraud caused by insiders has a greater impact in terms of financial losses than fraud caused by external actors (PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC), Citation2020; Agyemang et al., Citation2022). Previous fraud studies examined determinants of occupational fraud using the fraud triangle or the fraud diamond theory (Cressey, Citation1953; Said et al., Citation2017; Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Asmah et al.; Citation2019; Hidajat, Citation2020; Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021). Since prior empirical research showed the inconsistent relationship between the independent and dependent variables, the relationship could be explained by a third variable called the moderator variable (Hair et al., Citation2017). This study seeks to modify the scope of the FTT and FDT theory by not only examining the effect of fraud risk factors on occupational fraud, but also analyzing the moderating role of ethical culture on the relationship between these variables.

Although prior research has concluded that ethical culture can weaken the influence of fraud risk factors on the occurrence of fraud (Suh & Shim, Citation2020; Suh et al., Citation2018), the generalization of those findings is limited to countries that share cultural or regulatory environment similarities with South Korea. Cultural factors have been shown to affects values more strongly compared to national differences (Tan & Chow, Citation2009). Therefore, this study contributes to prior literature by employing the setting of a banking industry in a developing economy to examine whether ethical culture could moderate the relationship between fraud risk factors and the occurrence of occupational fraud.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Banking industry in Indonesia

The banking industry in Indonesia has a unique structure due to regulations. Per the provisions of Law No. 10 of 1998 on banking, there are two types of banks in Indonesia, namely commercial banks and rural banks. Furthermore, commercial banks can be classified into two categories, namely national commercial banks and regional development banks (RBDs). RDBs can be categorized as the “second banking sector” because of limitations in the capital, risk management, governance, compliance, and information technology compared to national commercial banks (Akyuwen et al., Citation2019; Karamoy & Tulung, Citation2020; Syaputra & Abidin, Citation2022).

Compared to Indonesian national commercial banks, RDBs have special characteristics regarding ownership and objectives (Akyuwen et al., Citation2019; Karamoy & Tulung, Citation2020). As for ownership, an RDB’s shares are not owned by the central government or the private sector. Almost all of the RDB’s shares are owned by local governments including the provincial, district, and municipal governments. The objectives of RDBs are not entirely directed at achieving profitability or increasing shareholder value; instead, they aim to support regional development. In this matter, RDBs must contribute to solving various regional development problems, such as unemployment, poverty, and social inequality. The Indonesian government has mandated that RDBs are expected to become regional champions in their respective regions in the context of banking operations (Akbar et al., Citation2019).

RDBs in Indonesia have strengths that they derive from their local presence (Akyuwen et al., Citation2019). RDBs are widely known by the local community. Thus, they become the choice for regional civil servants to work and they act as a financial institution that manages local government budgets. RDBs also have a specific captive market, namely civil servants who work in local governments. However, RDBs’ efforts to grow faced various internal challenges, such as weaknesses in the quality of human resources, products, service development, information technology, management information systems, and bureaucratic work culture. In addition, the quality of governance, risk management, and compliance with regulations are lower compared to commercial banks (Akbar et al., Citation2019; Akyuwen et al., Citation2019). Supriyono and Herdhayinta (Citation2019) concluded that the competitiveness level of RDBs is lower than that of commercial banks. Furthermore, Akbar et al. (Citation2019) and Syaputra and Abidin (Citation2022) provided empirical evidence showing that, on average, RDBs in Indonesia have not been consistently efficient in carrying out their operational activities.

In addition to those internal challenges, managers of RDBs often face obstacles in the form of intervention from local politicians (Akyuwen et al., Citation2019). The turnover of the board of commissioners and directors of RDBs is relatively faster compared to other banks because of the short-term interests of the heads of local governments. Another example is that RDBs are mandated to provide large loans to customers who may not fully comply with the banks’ credit policies. Consequently, the internal challenges and intervention of local politicians could potentially lead to a greater propensity of fraud in RDBs compared to national commercial banks (Suh & Shim, Citation2020).

2.2. Fraud risks in the banking industry

This study focuses on occupational fraud which is often referred to as “internal” or “employee fraud” (Holtfreter, Citation2005a, Citation2005b,; Suh et al., Citation2018). Occupational fraud is defined as “the use of one’s job to increase personal wealth through the intentional misuse or abuse of the resources or assets of the organization where one works” (ACFE, Citation2020; ACFE Chapter Indonesia, Citation2020). Therefore, occupational fraud is fraud against organizations that can be carried out by all individuals who are members of the organization, whether they are ordinary employees or directors. Occupational fraud falls into three categories: (1) asset misappropriation, which includes the theft or misappropriation of organizational assets; (2) corruption, where a person uses their influence in a business transaction to obtain an unauthorized advantage contrary to their duty to their employer; (3) financial statement fraud, where the reported financial statements are made to look better than they are (ACFE, Citation2020; Albrecht et al., Citation2015; Suh et al., Citation2018; Xiao et al., Citation2022).

The 2019 Indonesia Fraud Survey report showed that the banking industry had the highest risk of fraud exposure in the country (ACFE Chapter Indonesia, Citation2020). This statistic indicated a significant increase in the number of fraud cases in the banking industry because, in the 2016 Fraud Survey, banking was ranked second (after government institutions) in terms of fraud exposure of the total fraud cases (ACFE Chapter Indonesia, Citation2020). About two decades earlier, banking industry fraud in Indonesia in 1997–1998 contributed to a large amount of government debt due to the misappropriation of Bank Indonesia Liquidity Assistance (BLBI). Since the economic crisis in 1998, the frequency of fraud in Indonesian banks has continued to rise (ACFE Chapter Indonesia, Citation2020).

However, there is very little empirical literature that employed RDBs to test the theories of fraud and efforts to mitigate it. Suh and Shim (Citation2020) argued that there is a need for improvement in ethical culture, whistleblowing policy, and overall anti-fraud strategies for RDBs. Hidajat (Citation2020) investigated the causes of fraud in Indonesian rural banks using secondary data analysis. Compared to Hidajat’s study, our study focuses on RDBs which have much larger total assets than rural banks. Based on the Banking Industry Profile Report—Quarter III 2021, the total assets of all RDBs are IDR 801,390 billion, or 8.60% of the total assets of all commercial banks in Indonesia (Financial Services Authority, 2021). Meanwhile, the total assets of the rural banks amounted to IDR 162,374 billion as of 30 September 2021, which is significantly smaller than RDBs.

RDBs are exposed to a high risk of fraud due to weaknesses in governance and internal control (Akyuwen et al., Citation2019). From 2019 to 2021, several occupational fraud incidents occurred in Indonesia RDBs which were handled by law enforcement officials and made public in the mass media. “Bank A” (the RDB with the largest assets in Indonesia) experienced fraud due to fictitious credit disbursed by its branch head causing a loss of IDR 8.7 billion (Ridho, Citation2021). Fictitious credit was also the scheme employed in another case of fraud that occurred at “Bank B” (RDB with the second-largest assets in Indonesia) causing a loss of IDR 195 billion (Dirhantoro, Citation2022). Lending fraud also occurred in “Bank C” (the RDB with the third-largest total assets in Indonesia) which led to a total loss of IDR 597.7 billion (Rahmawaty, Citation2021).

Thus, a review of prior literature shows that there is a high risk of fraud in RDBs in Indonesia. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are not many studies that address the causes of fraud and consider the effect of ethical culture in mitigating fraud in RDBs. In the context of the country’s banking supervision, the Financial Services Authority has issued a fraud regulation, namely POJK No. 39 of 2019 on the Implementation of Anti-Fraud Strategies for Commercial Banks. Following these provisions, the anti-fraud culture program for bank employees is one of the important pillars promoted in the anti-fraud strategy. However, research on the effectiveness of anti-fraud culture in Indonesia has not appeared in the literature.

2.3. Ethical culture

Several factors influence a company’s fraud risk: (1) the nature of its business; (2) the environment in which the company operates; (3) the effectiveness of its control; and (4) the company’s ethics and values. Ethical culture is defined as “a subset of organizational culture, representing a multidimensional interplay among various formal and informal systems of behavioral control that are capable of promoting ethical behavior” (Trevino et al., Citation1998, p. 451). Schwartz (Citation2013) argues that three essential elements must be present if illegal or unethical activities are to be minimized through the maintenance of an ethical corporate culture. The three elements include: (1) the existence of core ethical values; (2) ethics training; (3) ethical leadership which sets the appropriate tone at the top as reflected by the board of directors and senior managers. Ethical culture is an important element in anti-fraud strategies compared to monitoring control (Suh & Shim, Citation2020; Suh et al., Citation2018).

2.4. Hypotheses development

This study investigates the relationship between fraud risk factors (opportunity, pressure, rationalization, and capability) and occupational fraud. In addition, this study examines the moderating role of ethical culture in the relationship between the four elements of fraud risk factors and occupational fraud (Figure ).

2.4.1. The relationship between opportunity and occupational fraud

A bank employee looks for opportunities to commit fraud to eliminate personal financial or non-financial pressure (Mangala & Soni, Citation2022). It is not sufficient for bank employee(s) to commit fraud just because of pressure; opportunities due to weaknesses in the internal control system should exist as well for fraud to occur. According to the Fraud Triangle Theory (FTT), the opportunity is defined as the opening of a door for a member of the organization to commit fraud (Cressey, Citation1953). Opportunities can arise from the conditions at a banking company that makes it possible for employees to commit fraud. Opportunities occur because of the weakness of an organization’s internal control system that allows perpetrators to commit fraud without being detected. Some of the weaknesses of the internal control system in banking include unclear segregation of duties and responsibilities, weak supervision from superiors, inadequate standard operating procedures, transactions that are not recorded promptly, unsafe cash boxes, and inadequate restrictions on access to savings books (Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021; Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Mangala & Soni, Citation2022; Suh et al., Citation2019).

Several studies on fraud in banking institutions (Abdullahi & Mansor, Citation2018; Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2016; Asmah et al., Citation2019; Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021; Bonsu et al., Citation2018; Hidajat, Citation2020; Hollow, Citation2014; Ilter, Citation2009, Citation2014; Jaswadi et al., Citation2022; Kassem, Citation2022; Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Murthy & Gopalkrishnan, Citation2022b; Rizwan & Chughtai, Citation2022; Said et al., Citation2017; Suh et al., Citation2019) concluded that the number of opportunities due to internal control weaknesses increases the occurrence of fraudulent practices. Based on the literature review, the following alternative hypothesis can be formulated:

H1. There is a positive relationship between opportunity and occupational fraud at regional development banks in Indonesia.

2.4.2. The relationship between pressure and occupational fraud

Pressure can be described as financial and non-financial burdens on individual members of the organization that can come from environmental, social, financial, and political sources (Mangala & Soni, Citation2022). Financial pressure can come from living beyond one’s means that encourage an immoral employee to commit occupational fraud (Asmah et al., Citation2019; Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021; Hidajat, Citation2020; Ilter, Citation2009; Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Sanusi et al., Citation2015; Suh & Shim, Citation2020). In the context of financial fraud, the pressure that comes from within the individual himself to support a lifestyle is the main determinant of occupational fraud (ACFE, Citation2020). Meanwhile, financial pressure from the organization is the pressure to meet the company’s profit targets.

The type of financial pressure varies depending on the role and position of the fraud perpetrator (Kazemian et al., Citation2019). Personal pressure is the main motivating factor for low-level employees, while middle and upper-level employees are more motivated by external or work-related pressures (ACFE, Citation2020; Mangala & Soni, Citation2022). Hidajat (Citation2020) found that non-financial pressure was the main factor for shareholders, commissioners, and directors to commit fraud in Indonesian rural banks. Meanwhile, employees at the middle and lower levels commit fraud mainly due to financial pressure, namely inadequate remuneration. Studies found strong evidence that pressure affects the tendency of bank employees to commit fraud (Asmah et al., Citation2019; Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021; Bonsu et al., Citation2018; Hidajat, Citation2020; Hollow, Citation2014; Kazemian et al., Citation2019). Therefore, a second alternative hypothesis is developed as follows:

H2. There is a positive relationship between pressure and occupational fraud at regional development banks in Indonesia.

2.4.3. The relationship between rationalization and occupational fraud

According to the FTT, the third element that drives fraud is rationalization. Kazemian et al. (Citation2019) and Asmah et al. (Citation2019) argued that a rationalization is an act that fraud perpetrators use to justify their fraudulent actions as being normal and morally acceptable and to defend themselves by saying they have no other choice. Examples of rationalization in banking fraud include employees who commit fraud with the justification that they only borrow money from the bank. Several other fraud perpetrators have justified their fraudulent actions as being a consequence of their salaries being too low (Kazemian et al., Citation2019)

Previous empirical studies found evidence showing that rationalization is positively associated with the occurrence of banking occupational fraud (Ilter, Citation2009; Sanusi et al., Citation2015; Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Avortri and Agbanyo, Citation2021). Based on the FTT and prior empirical literature, the following third alternative hypothesis is formulated:

H3. There is a positive relationship between rationalization and occupational fraud at regional development banks in Indonesia.

2.4.4. The relationship between capability and occupational fraud

Wolfe and Hermanson (Citation2004) believed that FTT does not sufficiently explain the nature of occupational fraud and therefore is not sufficient to prevent and detect the cases of fraud. Therefore, they included a new element called capability which refers to the position of a person in the organization that provides them with the ability to exploit an opportunity to engage in fraud. Kazemian et al. (Citation2019) argued that perpetrators of fraud are intelligent individuals who can understand and exploit internal control weaknesses and take advantage of their positions to gain benefits by committing fraud. Wolfe and Hermanson (Citation2004) also stated that the availability of “open doors” as opportunities is not enough; instead, perpetrators of fraud must have sufficient capabilities to take advantage of the situation.

Capability is the main motivating factor that gives employees with certain attributes the impetus to turn opportunities to commit fraud into reality (Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021). Capability plays a major role in the occurrence of fraud because, when it involves large amounts of money, it cannot be carried out without the right people with sufficient capabilities (Kazemian et al., Citation2019). Capability can even encourage others to work together to commit fraud. Empirical evidence from previous studies showed that capability is positively related to fraud in the banking industry (Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021; Kazemian et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the following alternative fourth hypothesis is written as follows:

H4. There is a positive relationship between capability and occupational fraud at regional development banks in Indonesia.

2.4.5. Moderation of ethical culture in the relationship between fraud risks and occupational fraud

Ethical culture is proposed as one of the recommended methods to reduce the influence of pressure, opportunity, rationalization, and capability on fraud (Murphy & Free, Citation2016; R; Ocansey & Gau, Citation2017; Suh et al., Citation2018; Suh & Shim, Citation2020, Citation2020). Rationalization and pressure that are felt by the individual are difficult to observe because both occur in the subjective human mind. Furthermore, only the perpetrators of fraud who experience the alignment of the fraud risk factors will commit fraud, while normal employees do not often face the factors at the same time. As a result, this makes empirical studies of risk fraud factors complicated (Schuchter & Levi, Citation2016). However, if the unit of analysis is converted to the organizational level, ethical culture can be a factor that negatively weakens the influence of fraud risk factors on the tendency to commit fraud (Dorminey et al., Citation2012; Murphy & Free, Citation2016; Suh & Shim, Citation2020; Suh et al., Citation2018). Suh and Shim’s (Citation2020) research showed that a more proactive and intensive managerial effort in creating an ethical culture can be perceived by employees as a more effective anti-fraud strategy.

Several studies in the literature emphasize the importance of developing an ethical culture as part of an organization’s anti-fraud strategy (Button & Brooks, Citation2009: Cheng & Ma, Citation2009; Han (Andy) Kim et al., Citation2022; Ocansey & Ganu, Citation2017; Omar et al., Citation2015; Sihombing et al., Citation2022; Siregar & Tenoyo, Citation2015; Suh & Shim, Citation2020; Suh et al., Citation2018). Suh and Shim (Citation2020) stated that there is a possibility that ethical values moderate the relationship between fraud risk factors. It is generally expected that employees with strong ethical values and integrity will not easily rationalize unethical behavior (Albrech et al., 1984; Albrecht et al., Citation2015; Dorminey et al., Citation2012; Ocansey & Ganu, Citation2017; Suh & Shim, Citation2020). Culture comprises the beliefs of members of an organization regarding how the organization should operate and behave. Thus, ethical culture is aimed more at influencing the behavior of members of the organization. Individuals as members of the organization are influenced by various factors at the organizational level. In this context, organizational culture can reduce fraud risk factors for occupational fraud (Ocansey & Ganu, Citation2017; Sahla & Ardianto, Citation2022). Suh et al. (Citation2018) showed that organizational investment in ethical culture is more effective than monitoring control in preventing occupational fraud. Said et al. (Citation2017) argued that strong ethical values are crucial elements for mitigating occupational fraud in the banking industry in Malaysia. Therefore, the following fifth alternative hypotheses of ethical culture in moderating the relationship between individual fraud risk factors elements and occupational fraud are written as follows:

H5a. Ethical culture weakens the positive relationship between opportunity and occupational fraud at regional development banks in Indonesia.

H5b. Ethical culture weakens the positive relationship between pressure and occupational fraud at regional development banks in Indonesia.

H5c. Ethical culture weakens the positive relationship between rationalization and occupational fraud at regional development banks in Indonesia.

H5d. Ethical culture weakens the positive relationship between capability and occupational fraud at regional development banks in Indonesia.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample selection

This study employs a sample of employees working in regional development banks (RDBs) in Indonesia. Compared to national commercial banks, the governance, quality of human resources, risk management, compliance, internal control, and information technology of RDBs are generally weaker than national commercial banks (Akyuwen et al., Citation2019; Karamoy & Tulung, Citation2020; Syaputra & Abidin, Citation2022). Due to those characteristics, RDBs are considered to be more susceptible to fraud risk factors compared to other commercial banks. According to the Financial Services Authority in Indonesia, there were 26 RDBs as of 31 December 2020.

This study purposively selected employees from the the fundraising, lending, treasury, and accounting departments at the head office of the 15 biggest RDBs in Indonesia. The total assets of these 15 banks represent an 85.39% of the total assets of all RDBs in Indonesia. Studies by ACFE (Citation2020) and Avortri and Agbanyo (Citation2021) found that employees from these departments have the highest incidence of occupational fraud. The data was obtained using a questionnaire survey which is widely used in banking fraud research (Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Avortri and Agbanyo, 2020; Suh et al., Citation2018; Suh & Shim, Citation2020). To ensure that all respondents were working in the fundraising, lending, treasury, or accounting department; this study administered the questionnaires for the respondents with assistance from the Planning and Research Division of each bank. Of the 600 questionnaires distributed, there were 355 usable responses resulting in a response rate of 59.16%. Table presents the demographics of the respondents. The list of questions used in the questionnaire is presented in Appendix.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents

3.2. Variables measurement

All variables in this study were measured using a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 equal strongly disagree to 5 equals strongly agree). The occupational fraud variable is measured by 6 indicators adopted from the research of Kazemian et al. (Citation2019), Said et al. (Citation2017), Suh et al. (Citation2018), and Suh and Shim (Citation2020). The opportunity, pressure, rationalization, and capability variables were measured using 7, 8, 8, and 2 indicators, respectively, by adopting the research of Kazemian et al. (Citation2019), Avortri and Agbanyo (Citation2021), and Said et al. (Citation2017), and Wells (Citation2001). The measurement of ethical culture uses 6 indicators adopted from Suh et al. (Citation2018), Suh and Shim (Citation2020), and Denison and Neale (Citation1999).

3.3. Data analysis

The data is analyzed using the Partial Least Square Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM is used to examine the relationship between unobserved or latent variables in a relatively complex research model with exogenous/independent, moderating, and endogenous/dependent variables (Hair et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Kock, Citation2020; Nitzl, Citation2016). By using PLS, the results of simultaneous hypotheses testing can be obtained by minimizing measurement and structural errors (Hair et al., Citation2019; Nitzl, Citation2016). PLS-SEM analysis was performed following the recommendations of Hair et al. (Citation2017) in two stages: (1) evaluation of the measurement model (outer model that explains the relationship between latent variables and their indicators; and (2) evaluation of the structural model or inner model that explains the relationship between latent variables/constructs.

3.4. Evaluation of measurement and structural models

The first stage in the PLS-SEM analysis evaluates the measurement model to ensure that the reliability and construct validity criteria are met (Hair et al., Citation2017; Kock, Citation2020). The results in Table show that the composite reliability values and Cronbach’s alpha are within the acceptable range of the construct reliability standard, which is more than 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2017; Kock, Citation2020). The convergent validity standard for all individual items is within the acceptable loading factor criteria, which are more than 0.70 and are statistically significant (p-values <0.01). Likewise, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values are more than 0.50, indicating acceptable convergent validity.

Table 2. Results of reliability and convergent validity tests

Evaluation of discriminant validity was carried out by comparing the square root of AVE with correlations between the constructs (Hair et al., Citation2017; Kock, Citation2020; Nitzl, Citation2016). The results in Table indicate that the square root of AVE in the diagonal column is higher than the correlation between the constructs (the numbers in the same column), showing that the discriminant validity criteria are met (Hair et al., Citation2017; Kock, Citation2020).

Table 3. AVE discriminant validity

The second stage of the PLS-SEM evaluates the structural model by performing the goodness of fit analysis. The goodness of fit results of the PLS-SEM model in Table indicate that all the criteria for average path coefficient (APC), average R-square (ARS), and average adjusted R-square (AARS) have been met and the analysis of the causal relationships could continue (Kock, Citation2020). In addition, the criteria for no multicollinearity in the model are also met with the average block variance inflation factor (AVIF) and average full collinearity variance inflation factor (AFVIF). Likewise, Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) and Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) are within acceptable parameters, so an analysis of the results of the hypothesis testing can be carried out.

Table 4. Model fit indices

4. Hypotheses testing results

Figure presents the results of the PLS-SEM structural model in the form of a standardized path coefficient, p-value, and coefficient of determination R-squared in accordance with the output of the WarpPLS 7.0 software.

Table presents the results of the structural model and hypotheses testing. They indicate that, out of the four fraud risk factors, two variables are positively related to occupational fraud. Firstly, opportunity positively and significantly predicts occupational banking fraud. One standard deviation of an increase in the opportunity could lead to a 0.375 increase in occupational fraudulent behavior in banks (p < 0.001). Secondly, pressure is shown to be a significant determinant of occupational fraud. One standard deviation of the increase in the pressure could lead to a 0.363 increase in occupational fraud behavior in banks (p < 0.001). However, the other two fraud risk factors did not have a significant effect on occupational fraud in RDBs in Indonesia. Rationalization and capability are not associated with the probability of occupational fraud. To conclude, this study found that out of the two significant fraud risk factors, the opportunity to commit fraud is the most significant determinant of occupational fraud behavior in Indonesian RDBs. This result supports the FTT model which argues that opportunity is a “doorway” for someone who is under pressure to commit fraud.

Table 5. Path coefficients and p-values results

Table shows the results of testing the moderating effect of PLS-SEM using the two-stage PLS-SEM approach following Hair et al. (Citation2017). The results in Table provide evidence that ethical cultures could moderate the relationship between two fraud risk factors (opportunity and pressure) and occupational fraud in RDBs in Indonesia. The interaction coefficient between opportunity and culture is −0.148 and is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.002 (p < 0.05). These results support the alternative hypothesis H5a, namely that a strong ethical corporate culture could mitigate the perceived opportunities of potential fraud perpetrators. The interaction coefficient between pressure and culture is −0.103 and is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.025 (p < 0.05), thus supporting the alternative variable H5b. This result suggests that a strong ethical corporate culture could weaken the pressure faced by bank employees to commit potential frauds. The interaction and main effects of the other two elements of fraud risk factors (rationalization and capability) are not statistically significant.

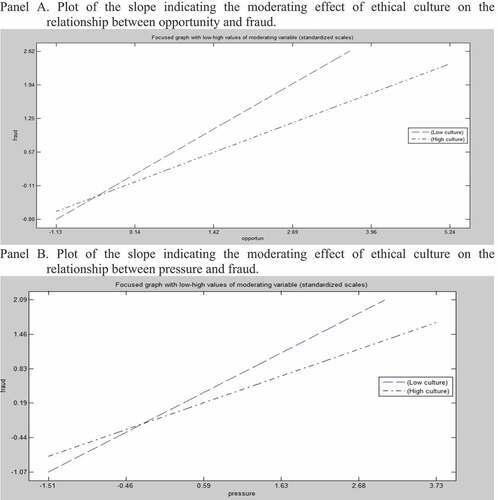

To clarify the results of the moderation test, we present the line plot of slopes that indicate the moderating effects of ethical culture in Figure Panel A & B following Hair et al. (Citation2017).

Figure 3. Moderating effect plot. Panel A. Plot of the slope indicating the moderating effect of ethical culture on the relationship between opportunity and fraud. Panel B. Plot of the slope indicating the moderating effect of ethical culture on the relationship between pressure and fraud.

Panel A shows that the slope that indicates the influence of opportunity on ethical culture is steeper for employees with weaker ethical culture. This result indicates that in conditions that indicate weaker ethical culture, the relationship between opportunity and fraud becomes stronger (Hair et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, the slope becomes flatter for employees with stronger ethical culture. This result shows that the relationship between opportunity and fraud becomes weaker for employees exhibiting stronger ethical culture. The plot from Panel A supports the hypothesis that ethical culture mitigates the positive relationship between opportunity and occupational fraud in Indonesian RDBs. The same interpretation could be applied to the slope plot indicating the moderating effect of ethical culture on the relationship between pressure and fraud in Panel B.

The results of this study provide empirical evidence that supports the fraud risk factors of the Fraud Triangle Theory (FTT), namely opportunities and pressure as determinants of occupational fraud in the banking industry of a developing economy that is highly exposed to fraud risk. The results of our study indicate that opportunity represents the main determinant of fraud in the financial sector which confirms the findings of previous research (Abdullahi & Mansor, Citation2018; Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2016; Asmah et al., Citation2019; Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021; Bonsu et al., Citation2018; Hidajat, Citation2020; Hollow, Citation2014; Ilter, Citation2009, Citation2014; Kaur et al., Citation2022; Kazemian et al., Citation2019; Navarrete & Gallego, Citation2022; Said et al., Citation2017; Suh et al., Citation2019). Likewise, we find that financial pressure could encourage employees to commit occupational fraud in the financial sector. This finding is also supported by previous studies (Asmah et al., Citation2019; Avortri & Agbanyo, Citation2021; Bonsu et al., Citation2018; Hidajat, Citation2020; Hollow, Citation2014; Kazemian et al., Citation2019).

This study also shows that a strong ethical culture can reduce the influence of risk factors by mitigating the effect of opportunities and pressures on the probability of occupational fraud. This finding corroborates the results of Suh et al. (Citation2018) which indicate that organizational investment in the strengthening of the ethical culture is effective in curbing the tendency of employees to commit fraud. This finding supports Suh and Shim’s (Citation2020) which demonstrated that a strong ethical culture (which includes core values, adequate support from top management, work integrity, and ethics training) is an effective anti-fraud strategy. This finding also supports Cheng and Ma (Citation2009) and Said et al. (Citation2017) who argued that it is important for banks to reform and strengthen business ethics to ensure that employees and organizations comply with regulations and do not engage in fraudulent activities.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

This study finds that the fraud risk factor of opportunity has a positive relationship with occupational fraud at RDBs in Indonesia. This finding indicates that weaknesses in internal control, such as transactions without sufficient authorization, late recording of transactions, unclear segregation of duties, undocumented procedures, insecure cashbox, or weak CCTV surveillance, could increase the risk of occupational fraud.

Furthermore, the fraud risk factor in the form of pressure has a positive association with occupational fraud. The pressure factor comprises both personal (luxurious lifestyles, insufficient salaries, family burdens, and unexpected expenses) and institutional pressures (such as excessively high-profit targets, workloads, and concerns about not getting bonuses due to unachievable targets). These examples of pressure could motivate bank employees to commit occupational fraud.

While the results of hypothesis testing indicate that rationalization and capability have no significant effect on occupational fraud. There are several possibilities for these results. Descriptive statistics show a low mean for these two variables. Rationalization factors such as low salaries, and fraud committed will not endanger finances and only borrowing bank assets are not enough to determine fraud. Capability is not a significant determinant because fraud in banking is not enough to be carried out by one individual employee, but requires the collusion of several parties.

Finally, the results of this study indicate that ethical culture is an important moderating variable that could weaken the positive relationship between the significant fraud risk factors (opportunity and pressure) and occupational fraud. Based on these findings, we recommend financial institutions in developing countries strengthen their ethical culture as a preventive measure. The organization should improve the code of ethics standard so that ethical practices are less dependent on the environment in which the employees and business operate (Said et al., Citation2017).

This study has limitations inherent in the questionnaire survey method, namely that the data on the occurrence of occupational fraud are based on employee perceptions, not the actual incidence of frauds identified by an audit process. However, the use of perceived fraud data in empirical studies is adequate because occupational fraud in the banking industry is regarded as a sensitive issue that complicates the collection of real fraud data (Suh et al., Citation2018). The questionnaire survey method is preferable because occupational fraud has a higher likelihood of being detected by bank employees (ACFE, Citation2020). The interpretation of the survey method is also constrained by personal bias and judgment errors. This study has attempted to minimize these biases, by guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality as well as using the reverse question technique.

Despite the limitations, our findings significantly expand the application of fraud risk frameworks (the fraud triangle theory and the fraud diamond theory) in mitigating occupational fraud risk for the banking industry in a developing country that has inherently high exposure to fraud. Our study finds that ethical culture could mitigate two significant fraud risk factors (opportunity and pressure). The first step in improving the ethical culture is to set a strong tone at the top, followed by strengthening core values and ethical training (Suh et al., Citation2018). These approaches could change the psychological framing for employees that should reduce the impact of fraud risk factors on occupational fraud. Future research could focus on evaluating the effectiveness of various measures that could be done to strengthen the ethical culture at the individual or organizational level. Future research could evaluate whether the internal challenges of RDBs such as quality of human resources, information technology, management information systems, and bureaucratic work culture contribute to the banking fraud. In addition, future research could compare the effectiveness of the ethical culture in moderating the fraud risk factors and fraud occurrences is similar between the first and second sectors of banking industry in Indonesia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdullahi, R., & Mansor, N. (2018). Fraud prevention initiatives in the Nigerian public sector: Understanding the relationship of fraud incidences and the elements of fraud triangle theory. Journal of Financial Crime, 25(2), 527–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-02-2015-0008

- ACFE (2020), “Report to the nation on occupational fraud and abuse”.

- ACFE Chapter Indonesia. (2020). “Indonesia Fraud Survey 2019”. ACFE Indonesia Chapter.

- Agyemang, S. K., Ohalehi, P., Mgbame, O. C., & Alo, K. (2022). Reducing occupational fraud through reforms in public sector audit: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Financial Crime, 1359–1790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-03-2022-0066

- Akbar, B., Djazuli, A., & Jariyatna, J. (2019 Jan-Jun). Measuring efficiency and effectiveness of Indonesian regional development banks. Journal of State Financial Governance & Accountability, 5(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.28986/jtaken.v5i1.309.

- Akomea-Frimpong, I., Andoh, C., & Ofosu-Hene, E. D. (2016). Causes, effects and deterrence of insurance fraud: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Financial Crime, 23(4), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-11-2015-0062

- Akyuwen, R., Susilo, R., & Kusumawijaya, R. (2019, March). Comparative financial performance of regional development banks and the banking industry in Indonesia. Journal of Applied Economics in Developing Countries, 4(1), 1–10. https://jurnal.uns.ac.id/jaedc/article/view/42557.

- Aladwan, Z. (2022). Legal basis for the fraud exception in letters of credit under English Law. Journal of Financial Crime, 1359–1790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-01-2020-0004

- Albrecht, W. S., Albrecht, C. O., Albrecht, C. C., & Zimbelman, M. F. (2015). Fraud Examination (5th ed.). South-Western College.

- Asmah, A. E., Atuilik, W. A., & Ofori, D. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of staff related fraud in the Ghanaian banking industry. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(3), 669–682. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-03-2019-0034

- Avortri, C., & Agbanyo, R. (2021). Determinants of management fraud in the banking sector of Ghana: The perspective of the diamond fraud theory. Journal of Financial Crime, 28(1), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-06-2020-0102

- Bonsu, O.-A. M., Dui, L., Muyun, Z., Esare, E. K., & Amankwaa, I. A. (2018). Corporate fraud: Causes, effects, and deterrence on financial institutions in Ghana. European Scientific Journal, 14(28), 315–335. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n28p315

- Button, M., & Brooks, G. (2009). Mind the gap”, progress towards developing anti-fraud culture strategies in UK central government bodies. Journal of Financial Crime, 16(3), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/13590790910971784

- Chen, L., Jia, N., Zhao, H., Kang, Y., Deng, J., & Ma, S. (2022). Refined analysis and a hierarchical multi-task learning approach for loan fraud detection. Journal of Management Science and Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmse.2022.06.001

- Cheng, H., & Ma, L. (2009). White collar crime and the criminal justice system: Government response to bank fraud and corruption in China. Journal of Financial Crime, 16(2), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/13590790910951849.

- Cressey, D. R. (1953). Other people’s money: A study in the social psychology of embezzlement. Free Press.

- Denison, D. R., & Neale, W. S. (1999). Denison organizational culture survey: facilitator guide. Denison Consulting, LLC, 104. http://scholar.google.de/scholar?q=Denison+organizational+culture+survey&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5&as_ylo=1996&as_yhi=1996#0

- Dirhantoro, T. (2022). “Kejaksaan Bongkar Korupsi di Bank Jatim Kali Kedua: Kerugian Total Rp195 M, 8 Orang Jadi Tersangka”. Kompas.tv. https://www.kompas.tv/article/249097/kejaksaan-bongkar-korupsi-di-bank-jatim-kali-kedua-kerugian-total-rp195-m-8-orang-jadi-tersangka

- Dorminey, J., Scott Fleming, A., Kranacher, M. J., & Riley, R. A. (2012). The evolution of fraud theory. Issues in Accounting Education, 27(2), 555–579. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-50131

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publication, Inc.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2019). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

- Han (Andy) Kim, Y., Park, J., & Shin, H. (2022). CEO facial masculinity, fraud, and ESG: Evidence from South Korea. Emerging Markets Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2022.100917

- Hidajat, T. (2020). Rural banks fraud: A story from Indonesia. Journal of Financial Crime, 27(3), 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-01-2020-0010

- Hollow, M. (2014). Money, morals and motives: An exploratory study into why bank managers and employees commit fraud at work. Journal of Financial Crime, 21(2), 174–190. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-02-2013-0010

- Holtfreter, K. (2005a). Fraud in US organisations: An examination of control mechanisms. Journal of Financial Crime, 12(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1108/13590790510625070

- Holtfreter, K. (2005b). Is occupational fraud typical white-collar crime? A comparison of individual and organizational characteristics. Journal Criminal Justice, 33(4), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2005.04.005

- Ilter, C. (2009). Fraudulent money transfers: A case from Turkey. Journal of Financial Crime, 16(2), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/13590790910951803

- Ilter, C. (2014). Misrepresentation of financial statements: An accounting fraud case from Turkey. Journal of Financial Crime, 21(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-04-2013-0028

- Jaswadi, J., Purnomo, H., & Sumiadji, S. (2022). Financial statement fraud in Indonesia: A longitudinal study of financial misstatement in the pre- and post-establishment of financial services authority. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 1985–2517. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-10-2021-0336

- Karamoy, H., & Tulung, J. (2020). The impact of banking risk on regional development banks in Indonesia. Banks and Bank Systems, 15(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.15(2).2020.12

- Kassem, R. (2022). Elucidating corporate governance’s impact and role in countering fraud. Corporate Governance. Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-08-2021-0279

- Kaur, B., Sood, K., & Grima, S. (2022). A systematic review on forensic accounting and its contribution towards fraud detection and prevention. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 1358–1988. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-02-2022-0015

- Kazemian, S., Said, J., Nia, E. H., & Vakilifard, H. (2019). Examining fraud risk factors on asset misappropriation: Evidence from the Iranian banking industry. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(2), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-01-2018-0008

- Kock, N. (2020). WarpPLS 7.0 user manual. ScriptWarp Systems.

- Mangala, D., & Soni, D. (2022). A systematic literature review on frauds in banking sector. Journal of Financial Crime. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-12-2021-0263

- Maulidi. (2022). Gender board diversity and corporate fraud: Empirical evidence from US companies. Journal of Financial Crime, 1359–1790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-02-2022-0038

- Murphy, P. R., & Free, C. (2016). Broadening the fraud triangle: Instrumental climate and fraud. Behavioural Research in Accounting, 28(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria-51083

- Murthy, N., & Gopalkrishnan, S. (2022a). Creating a nexus between dark triad personalities, non performing assets, corporate governance and frauds in the Indian banking sector. Journal of Financial Crime, 1359–1790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-05-2022-0097

- Murthy, N., & Gopalkrishnan, S. (2022b). Does openness increase vulnerability to digital frauds? Observing social media digital footprints to analyse risk and legal factors for banks. International Journal of Law and Management, 64(4), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-04-2022-0081

- Navarrete, A., & Gallego, A. (2022). Forensic accounting tools for fraud deterrence: A qualitative approach. Journal of Financial Crime, 1359–1790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-03-2022-0068

- Nitzl, C. (2016). The use of partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in management accounting research: Directions for future theory development. Journal of Accounting Literature, 37(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acclit.2016.09.003

- Ocansey, E. O., & Ganu, J. (2017). The role of corporate culture in managing occupational fraud. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 8(24), 102–107. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/RJFA/article/view/40176.

- Omar, N., Johari, Z., & Hasnan, S. (2015). Corporate culture and the occurrence of financial statement fraud: A review of literature. Procedia Economics and Finance, 31, 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01211-3

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC), (2020), “PwC’s global economic crime and fraud survey. PWC”. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/forensics/economic-crime-survey.html

- Rahmawaty, L. (2021). “Kasus korupsi Bank Jateng rugikan negara Rp597,97 miliar”. Antara News. https://www.antaranews.com/berita/2609845/kasus-korupsi-bank-jateng-rugikan-negara-rp59797-miliar

- Repousis, S., Lois, P., & Veli, V. (2019). An investigation of the fraud risk and fraud scheme methods in Greek commercial banks. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 22(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-11-2017-0065

- Ridho, R. (2021). “Kasus Kredit Fiktif Rp 8,7 Miliar, Mantan Pejabat Bank di Tangerang Divonis 5,5 Tahun Penjara”. Kompas.com. https://regional.kompas.com/read/2021/06/03/054056678/kasus-kredit-fiktif-rp-87-miliar-mantan-pejabat-bank-di-tangerang-divonis?page=all

- Rizwan, S., & Chughtai, S. (2022). Reestablishing the legitimacy after fraud: Does corporate governance structure matter? South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 2398–628X. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-08-2020-0286Rodgers

- Sahla, W. A., & Ardianto, A. (2022). Ethical values and auditors fraud tendency perception: Testing of fraud pentagon theory. Journal of Financial Crime, 1359–1790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-04-2022-0086

- Said, J., Alam, M. M., Ramli, M., & Rafidi, M. (2017). Integrating ethical values into fraud triangle theory in assessing employee fraud: Evidence from the Malaysian banking industry. Journal of International Studies, 10(2), 170–184. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2017/10-2/13

- Sanusi, Z. M., Rameli, M. N. F., & Isa, Y. M. (2015). Fraud schemes in the banking institutions: Prevention measures to avoid severe financial loss. Procedia Economics and Finance, 28, 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01088-6.

- Schuchter, A., & Levi, M. (2016). The fraud triangle revisited. Security Journal, 29(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2013.1

- Schwartz, M. S. (2013). Developing and sustaining an ethical corporate culture: The core elements. Business Horizons, 56(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2012.09.002

- Sihombing, R., Soewarno, S., & Agustia, D. (2022). The mediating effect of fraud awareness on the relationship between risk management and integrity system. Journal of Financial Crime, 1359–1790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-02-2022-0058

- Siregar, S. V., & Tenoyo, B. (2015). Fraud awareness survey of private sector in Indonesia. Journal of Financial Crime, 22(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-03-2014-0016

- Suh, J. B., Nicolaides, R., & Trafford, R. (2019). The effects of reducing opportunity and fraud risk factors on the occurrence of occupational fraud in financial institutions. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 56 March 2019, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2019.01.002

- Suh, J. B., & Shim, H. S. (2020). The effect of ethical corporate culture on anti-fraud strategies in South Korean financial companies: Mediation of whistleblowing and a sectoral comparison approach in depository institutions. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 60 March 2020, 100361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2019.100361

- Suh, J. B., Shim, H. S., & Button, M. (2018). Exploring the impact of organizational investment on occupational fraud: Mediating effects of ethical culture and monitoring control. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 53 June 2018, 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2018.02.003

- Sunardi, S., & Amin, M. N. (2018). Fraud detection of financial statement by using fraud diamond perspective. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 7(3), 878–891. https://isdsnet.com/ijds-v7n3-04.pdf.

- Supriyono, R., & Herdhayinta, H. (2019). Determinants of bank profitability: The case of the regional development bank in Indonesia. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business, 34(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.22146/jieb.17331

- Syaputra, R., & Abidin, Z. (2022). Performance analysis of regional development banks in Indonesia using data envelopment analysis approach. American International Journal of Business Management (AIJBM), 5(1), 134–140. https://www.aijbm.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Q51134140.pdf.

- Tan, J., & Chow, I. H. S. (2009). Isolating cultural and national influence on value and ethics: A test of competing hypotheses. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9822-0

- Trevino, L. K., Butterfield, K. D., & McCabe, D. L. (1998). The ethical context in organizations: Influences on employee attitudes and behaviours. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8(3), 447–476. https://doi.org/10.5840/10.2307/3857431

- Valukas, A. R. (2010). White-collar crime and economic recession. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 2010(1, Article 2), 1–21 https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234121829.pdf.

- Wells, J. (2001). Why employees commit fraud. Journal of Accountancy, 191(February), 89–91. http://www.calgarycommunities.com/content/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Why-Employees-Commit-Fraud.doc

- Wolfe, D. T., & Hermanson, D. R. (2004). The fraud diamond: Considering the four elements of fraud. The CPA Journal, 74(12), 38–42. https://www.proquest.com/docview/212311888?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true.

- Xiao, X., Li, X., & Zhou, Y. (2022, March). Financial literacy overconfidence and investment fraud victimization. Economics Letters, 212 March 2022, 110308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2022.110308

- Younus, M. (2021). The rising trend of fraud and forgery in Pakistan’s banking industry and precautions taken against. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 13(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-03-2019-0037