Abstract

The proponents claim that the Indian Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016 (RERDA, 2016/Act) has saved homebuyers from exploitation by promoters’ evasive and aggressive approach and has impacted society. The paper, while discussing the relevant statutory provisions and judicial decisions protecting urban homebuyers’ interests, examines the reactions of 751 respondents, comprising homebuyers, unsuccessful buyers, builders, officials, and nine experts, using descriptive statistics, ANOVA, and the chi-square test. The findings show that builders’ lobbying and regulatory capture exploit homebuyers. Timely judiciary interventions have eased builders’ obstacles, allowing builders and governments to safeguard homebuyers’ interests. Politics and interstate tensions create homebuyers’ owes. Violation of ethical principles is a common practice. However, the Act’s performance remains uneven six years after its adoption. Our results on real estate reform might help policymakers, and planners, alter current laws in a worldwide competitive economy. Our findings suggest that a law’s success in a country’s development depends on political will, design, alignment with development objectives, flexibility, efficacy, and adaptability to socioeconomic realities. The study has implications for research on the real estate market’s theory, policy, and socioeconomic practice.

1. Introduction

A growing population and urbanization bring with them social, economic, and environmental issues that have an impact on housing.Footnote1 With the increasing urbanization trend, 80–90% of the population will live in cities by 2100, putting pressure on housing markets (United Nations, Citation2017). Urbanization heralds a surge in economic growth (Henderson, Citation2010; Turok & McGranahan, Citation2013)-brings more global capital and foreign direct investment (FDI) for infrastructure development, particularly in urban housing and real estate businesses (Lin et al., Citation2018; Van Doorn et al., Citation2019). While unprecedented urban growth provides an unparalleled opportunity for local economic development, residents require suitable and affordable housing—a challenge that remains a global issue.Footnote2 Providing a higher standard of living in cities has also become a crucial problem for urban planning (Mouratidis, Citation2021). Urban planning, if not correctly addressed through regulation and policy, a reduction in the urban residential area, living space, and housing stock, as well as a rise in real estate value, will be a challenging task (Mendonça et al., Citation2020).

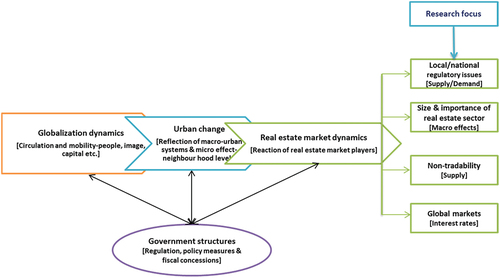

Globalization supports and influences urban regions as economic entities, and among others, it has heralded real estate requirements (NORGES Bank, Citation2015). Urbanization under globalization results from a multifaceted society, a complex economy, and an interconnected culture; it is becoming more open and more affected and restricted by external causes (Hu & Chen, Citation2015). In the face of many changes to urban settings affected by globalization, factors like new regulatory interventions are essential to reflect and organize global, national, and local changes (Da Cunha et al., Citation2012). Most countries’ housing and real estate markets feature strong government involvement in regulation, policy measures, and various fiscal concessions. As a result, the markets are highly complex, since economic and “extra-economic” factors influence the outcome. These factors also affect the pricing, volume, composition, and structure of real estate markets. Using the work of Bardhan and Kroll (Citation2007), Da Cunha et al. (Citation2012), and NORGES Bank (Citation2015), illustrates the underlying economic, legal, and other variables that affect real estate’s reaction to globalization. Such an analysis gives rise to a different way of looking at the relationship between real estate and social and economic issues. Specifically, this refers to the competitive aspect, economics, and social control of the sector. Moving along a similar trend, India also faces challenges regulating housing and real estate markets (McGranahan & Martine, Citation2012). Studying the legal and policy issues governing such an essential market in an Indian context makes sense.

1.1. Real estate market in the Indian context

States’ property laws primarily govern Indian housing markets, including land transfer, ownership, and registration. Before 2008, there were no regulations to monitor the housing, retail, hospitality, and commercial real estate markets.Footnote3 The government’s limited responsibilities included land allocation and issuing licenses and approvals.Footnote4 Middle-class Indians, primarily urban settlers, have suffered significantly due to real estate builders’, promoters’, and agents’ exploitative attitudes and aggressive approaches (Mahadevia, Citation2001).Footnote5 The market was unregulated. Most developers were family-owned businesses. There were severe ethical issues. Developers used to require homebuyers to sign unilateral contracts with strict payment terms. The promise to deliver land or apartments (flats) on time was a futile exercise.Footnote6 They charged exorbitant interest even with a day’s delay in an installment payment. Cost escalation frequently caused anger and frustration due to uncertainty in the delivery and refund of settlements in disputes.Footnote7 Many cities’ housing project promoters created artificial scarcityFootnote8 through deceptive advertisements and information, luring prospective homebuyers to rush into bookings. The government was aware of the promoters’ constant harassment, lawsuits, and other problems.

Because of the attractive returns, many global and domestic corporate houses and investors jumped into Indian real estate after 2008. The market expanded quickly, but it had flaws like creating supply without estimating demand. Developers’ land banks and project launches heavily influenced pricing and valuation. These practices caused fiscal irregularities and project delays.Footnote9 In addition, homebuyersFootnote10 could not receive complete information or hold builders accountable without an effective mechanism. Some aggrieved buyers obtained relief from the courts under the Consumer Protection Act (COPRA), 1986, but builders prolonged the litigation by exploiting arbitration clause loopholes.Footnote11 Furthermore, the construction works were defective in violation of the guidelines of the National Building Code of India.Footnote12 Even the promoters violated their ethical standard as envisaged through their association’s “Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice” (National Association of Realtors-India).Footnote13 Homebuyers’ option of moving to consumer courts was still inadequate to redress their concerns. Because the land was a state issue, state governments governed and controlled the real estate business, each with its own rules, creating complications due to a lack of standardization.

Because the industry was almost opaque, unregulated, and unaccountable until 2016, there was a need for legislation to protect consumers’ (i.e., homebuyers’) interests and boost the economy. India needed to counter the negative impact of the unregulated real estate market by improving EoDB and inviting more FDI.Footnote14 Regulatory reforms were necessary for India’s changing macroeconomic policies (Mitra & Singh, Citation2010). After almost eight years of debate, from May 2008 to March 2016, the Indian government passed the Act on 25 March 2016 to regulate the real estate industry and benefit homebuyers.Footnote15 Research on real estate regulation, homebuyers (primary beneficiaries), and social linkage is essential.

Economic analysis of legislation forecasts the impact of laws on individual incentives and behavior and evaluates the societal efficiency of alternative rules (Holman, Citation2004; Kaplow & Shavell, Citation1999). This analysis yields different results (Popa, Citation2021). Policy punctuations vary based on political change. Regulatory changes link law and society, altering organizational domains and executive leadership (John & Bevan, Citation2012). We noticed this change in India after May 2014 with the new regulation’s implementation to fix homebuyers’ complaints in 2016.

In this context, the Indian government’s legal policy and perspectives on urban housing and real estate markets to ensure the quality of life for urban settlers owning a dream home (one’s ideal residence) take on research importance. As a result, the primary goal of this paper is to critically examine the various provisions of the Act that arguably protect the interests of consumers, particularly urban homebuyers. Additionally, we analyze their impact on them and society.

2. Literature review and research gap

Shelter, houses, and homes are three levels of housing that are basic physiological needs (Miller Lane, Citation2006; Oliver, Citation1978). According to Bachelard (1994), intimacy, daydreams, imagination, and memories affect a home’s establishment. Making a distinction between these three, Oliver (Citation1978) and Miller Lane (Citation2006) viewed the home as a connotative social system, reflecting the family’s relationship with home space. Bledsoe (Citation2019) links it to life quality and humanizes housing. Higher happiness levels are higher among those who own a home (Cheng et al., Citation2020). These propositions imply that people want to build or buy their dream homes with hard-earned money.Footnote16

As a critical infrastructure, housing is a large part of the real estate industry. Experts say housing drives economic growth (Van Dijk, Citation2019). Housing’s combined contribution to the GDP of the USA, UK, Australia, India, China, Japan, and Germany averages 3–18%, implying its contribution to nation-building. Acolin et al. (Citation2021) confirm that the housing sector contributes around 13% to GDP in emerging market economies. As housing goes, so does the economy (Arku, Citation2006). Housing affects economic stability, labor mobility, productivity, affordability, human capital, and life chances. Consumption and spending affect the economy indirectly. Housing aids poverty reduction (Kisiała & Rącka, Citation2021; Leviten‐Reid et al., Citation2021; Saguin, Citation2020; Singh et al., Citation2020). The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)—2015, specifically Habitat for Humanity, demonstrate the importance of housing to people, communities, and the global economy. Housing affects life quality (Doling et al., Citation2013). India respects the UN’s right to adequate housing.

According to macroeconomic policy, the Indian government’s housing policy has shifted from providing housing units to encouraging their provision (D’Souza, Citation2019; Gopalan & Venkataraman, Citation2015). Economically, housing lasts. Proper housing conditions improve household welfare by providing shelter. In addition to enabling better health, education, and nutrition, they also contribute to social benefits such as lower public health costs and the rule of law. It took several years to get clearance/approval from multiple agencies at the center and state levels—the environment department, development authority, municipal corporation, and fire safety. Costs and time discouraged many entrepreneurs, promoters, and builders. Inadequate regulations exacerbated the situation (Gopalan & Venkataraman, Citation2015). The analysis of homebuyers’ litigation-related case decisions suggests increasing complaints against builders/promoters and real estate agents for contract violations, construction defects, and poor service. The magnitude of the problem forced the Indian government to develop a firm housing policy and model Act, namely The Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016 (RERDA, 2016/Act), in March 2016, effective May 2016.

Adopting a State Act and Rules in response to RERDA, 2016, to regulate the housing and real estate industry and protect homebuyers is a positive step. Because of the exploitative real estate market, homebuyers’ investment in a lifetime dream home is complicated. Forbes believes housing is vital because consumers (homebuyers) value it, so the proposed Rules may build trust and make decisions easier.Footnote17 These factors prompted research on homebuyers’ protection at the micro-level. Finding the research gap through a literature review is an essential academic exercise that has significance.

Because the research focuses on 2016 real estate regulations governing urban housing and real estate markets, the research gap identification exercise scoured Mendeley, Google Scholar, SSRN, CORE, and DOAJ for impact assessment of law on the theme in general, spanning over 1900 articles published since 1998. We could not find an impact study on homebuyers or society. The first group was policy issues and measures that covered the analysis and debate of austerity measures, FDI, the financial crisis, housing equality, regulatory governance, and taxation difficulties. Studying socioeconomic factors as a second broad category included discriminatory treatment and harassment of builders, corruption in property, demand-supply issues, housing affordability, housing market assessment, housing pricing and/or bubble formation, poverty and housing needs, the public housing system and mortgage instruments, real estate business practices, and users’ housing motivation. There were a few studies on postimplementation legal issues. However, the research does not show how laws affect key actors’ behavior. In economics and management, the law is only just coming into play in the housing industry, and its implications for the primary actors (homebuyers) are hardly apparent. The study fills this gap. briefly enumerates the relevant features studied in the past.

Table 1. Research gap identification-highlights of literature survey

The forgone analysis brings home two research questions to ponder.

First, is the RERDA, 2016 beneficial to homebuyers and society? The rationale behind it is that most individuals follow most laws the majority of the time. Nonetheless, increasing adherence is a critical component of a law’s success. Thus, compliance with legislation is an essential measure of its influence (Bogart, Citation2002). However, the ceremonial laws’ existence doesn’t always have the desired impact. Many nations don’t implement rules, apply them selectively, or can’t implement them (World Bank, Citation2017). In this context, the research question stems from the Act, which compels builders to work within the strict framework of government regulations and its regulatory board. Penal provisions appear stringent. Frivolous supply will automatically decrease because of restrictions on builders’ multiple projects at a time. Keeping homebuyers’ interests in mind, builders have no choice but to avoid risks and litigation. Therefore, the policy and impact assessment to answer the research question assumes significance.

Second, does the regulation aid FDI inflow into India? The latest evidence is available to establish FDI’s relationship with economic growth (Çakërri et al., Citation2021; Miao et al., Citation2021). Because FDI flows are a well-studied and often-discussed topic, we won’t be looking at them in this exercise. Instead, we’ll be looking at the Act’s effects, a barren area of research, particularly on homebuyers and society as a whole.

2.1. Theory development and research model

In contemporary society, the role of the law as an agent of social transformation is gaining prominence. The law is significant because it guides society’s acceptable behavior and brings about social change in a nation or area. It influences politics, the economy, and the community and mediates interpersonal connections. Social institutions enforce laws to control conduct (Kostiner, Citation2003; Vago et al., Citation2017). Law influences the development and preserves civic liberty to promote economic growth. Law is vital because it maintains and supports internal stability and directs policies that nations should pursue throughout the development process, and it is susceptible to local variations (Y.-S. Lee, Citation2017). The law makes it simple to adapt to societal changes. There would be conflicts between social groups and communities if they did not exist (Armstrong & Frankot, Citation2020; Mather, Citation2013). As a result, we renew our belief that the law has been and continues to be critical in introducing societal structure and relationship changes.

The quality of implementation of the law is another concern in understanding its effectiveness in serving people and society better. Analyzing Y.-S. Lee (Citation2017), the quality of the law’s implementation involves regulatory enforcement. The law maintains order by performance, including regulatory enforcement. The legislation assesses its effectiveness by how well a state meets the requirements of the law, including its enforcement and monitoring measures. Cases of infractions (particularly those overlooked by the state), omissions, and poor state implementation affect execution quality. Incompetence and corruption hurt performance. In light of this, we build a research model to determine how RERDA affects homebuyers and society.

Regulation stems from public concern about the impact of one or more businesses’ actions (Dixon et al., Citation2006). The Indian government enacted the Act primarily to protect homebuyers’ interests—timely project delivery, rescue from harassment by builders, and to boost the economy through industry-regulated growth. After six years of implementation, the government claims that the Act has empowered homebuyers and has protected their rights as consumers. There are a number of claims and reports with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs that indicate the government is proactive, the judiciary has effective intervention, and builders respect laws and regulations.Footnote18 From the reference materials (Dimri, Citation2019; Kumar & Miryala, Citation2021) and a preliminary study, we found four primary factors impacting the Act’s impact on homebuyers and society. The factors are awareness of the Act (aa), delivery time (dt), builders’ harassment (bh), and grievance redress (gr). Mathematically, E = f(aa, dt, bh, gr). While recognizing various actors’ roles, the hypothesis (H₁) is that the Act did not protect homebuyers’ interests across the country; it was ineffective. There is no significant difference in the respondents’ opinions among the four factors (H₂: faa = fdt = fbh = fgr; alternatively, H₂: all factors are not the same). presents a research model for the proposed hypotheses.

3. Research methods and design

The study reviews the policy implications of the Act’s postimplementation period and answers the specific research question of how the Act has impacted homebuyers, the prime stakeholders, with consequences for society. Accordingly, we adopted a research design, sampling method, and analytical tool. The sample was from across the country’s four zones (east, west, north, and south), with eight capital cities, two from each zone, to minimize the bias and answer the research question succinctly.

The research used secondary and primary data. Secondary data sources included central and state government websites, India Brand Equity Foundation, National Real Estate Development Council, Asia Pacific Real Estate Association, Real Estate Developers Association, Confederation of Real Estate Developers’ Association, the United Nations and leading business/legal publications and reports. Using the Right to Information Act of 2005, we sought information from the public domain wherever applicable. The method relies on reviewing the Act relevant to homebuyers and judicial pronouncements.

Field research assessed the Act’s impact on homebuyers and society. Referring to Szolnoki and Hoffmann (Citation2013), Bornstein et al. (Citation2013), and Brodaty et al. (Citation2014), we followed convenience sampling with due care to avoid sampling bias due to data collection from different regions and different categories of respondents. Moreover, COVID-19 restrictions led to convenience-based sample size selection. Without funding, convenience sampling was the logical and preferred data collection option. The sample covered the prior RERDA, 2016 enactment period and had at least two years of real estate ownership before the interview date. Because the Act primarily benefits urban “middle-income settlers”Footnote19 dreaming of a sweet home, homebuyers buying up to three residential unitsFootnote20 were in the sample. We excluded investors wanting to resell or rent.

We surveyed 1027 homebuyers from eight Indian metropolitan cities. Of them, 572 (56%) participated. Finally, the views recorded by 540 (94%) homebuyers were suitable and provided the impact outcome. City selection criteria included capital region, city type, and apartment culture. Indore’s selection was because it is the financial capital of Madhya Pradesh, and it was the cleanest city in India from 2016 to 2021. Kochi’s chosen preference was because, on 8 May 2019, the Supreme Court ordered the demolition of four multistory apartment buildings with 357 flats for violating Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) norms, affecting 1500 homebuyers and creating a sensational issue.Footnote21

The respondents included 54 homebuyers who had booked flats from the Delhi region’s leading real estate developer (Amrapali Silicon City Private LimitedFootnote22). About 41% of the respondents belonged to the Odisha state capital of Bhubaneswar and Delhi, the national capital, where the researchers live. Other respondents belonged to Bengaluru, Kochi, Hyderabad, Indore, Kolkata, and Mumbai. gives a glimpse of the distribution of respondents according to zone, specific location, and reasons for sample selection coverage across the country.

Table 2. Distribution of respondents according to zone, specific location and reasons for selection (N = 540)

.The information was collected using a pretested semistructured questionnaire about flat possession, apartment life, society management, and developers’ approach to homebuyers between January and May 2021. The questionnaire had acceptable internal consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.652) at a 1% significance level. From March-June 2021, the researchers could also contact 87 unsuccessful buyers. We analyzed all 540 respondents’ views and quoted unsuccessful buyers’ responses to meet the research objectives. The talks focused on two main questions: (ii) whether the builder harassed homebuyers; if so, at what stage, types of harassment and recourse; and (ii) whether the Act benefited/impacted them. Home cost, payment structure, builder’s promised date of giving possession and delay period, time of filing a complaint, choice of the grievance redress mechanism, views on regulating agencies, including the government and builder, and builder harassment were all questions. We conducted face-to-face interviews with homebuyers/owners and attended apartment society (management) meetings, mobile calls, and Skype/WhatsApp/messenger chats for data collection. Friends and contacts helped arrange computer-assisted meetings and interactions at different locations. The authors tallied the opinions for analysis and interpretation.

For RERDA 2016 development, in the sixth year of its implementation, we preferred to match homebuyers’ responses with builders’ views, the judiciary’s mind, and experts’ opinions. In this second phase field survey covering all regions between January and April 2022, we received responses through contacts and e-mails from various online sources. The responses were from 59 builders out of 114 approaches (52%) and 39 functionaries from the judiciary and state real estate regulating authorities, including advocates (55% response) and 17 other government officials who dealt with real estate issues (43% reply). The questionnaire contained three parts: a partially structured questionnaire (rank and order format 1 to 5), a partly Likert scale (poor to very high), and an open-ended component. A score between 2.5 and 3.5 is considered moderately low or high, and above 4.5 is the highest. Additionally, nine out of 22 independent experts from various agencies (41%), whom we contacted in December 2021, responded to a pairwise comparison questionnaire (1 to 9 in either direction of increasing importance) and were deemed suitable for analysis.

Following Boone and Boone (Citation2012), we used one-way ANOVA to determine the significance of the Act’s effectiveness and looked at all 751 answers from homebuyers, failed buyers, builders, judges, experts, and other officials. Because the sample collection was from eight capital cities, we performed the chi-square test to validate the regional variation of the Act’s impact on homebuyers in the country. At the end of the analysis, following Ishikawa (Citation2004) and Mahto and Kumar (Citation2008), we dissected the findings through Fishbone’s diagram, a root cause analysis tool,Footnote23 which appears appropriate for a graphical presentation to identify and explain the Act’s impact on homebuyers and society.

4. Results and analysis

Before discussing the research findings, understanding the RERDA 2016 provisions that assist homebuyers is essential. The lack of standards slowed industry growth. Homebuyers could not get accurate information or hold developers and builders accountable without a legally enforceable system. The 1986 Consumer Protection ActFootnote24 offered a forum for resolving such complaints, but the remedy was curative and insufficient to meet all purchasers’ and promoters’ concerns. Homebuyers and other impacted parties underlined the necessity for a particular Act in numerous forums. Because the Act came into effect in May 2016, it is crucial to analyze its provisions protecting homebuyers’ interests. looks at homebuyers-related clauses and the implementation timeline, indicating that the Act ensures security, transparency, fairness, quality, and permission.

4.1. Benefits of homebuyers

The Act has defined RERA as resolving conflicts between builders and homebuyers faster and time-bound. Homebuyers have the right to transparency in measurement, payment structure, completion time, and penalties for delays or legal issues. Besides, they need clarity on area measurements, refund claims, speedy trials, and financial discipline. summarizes the benefits of RERA to buyers vis-à-vis other key players.

Table 3. Benefits of RERA

With REDA 2016 and IBC 2016, disgruntled buyers have more alternatives for rapid redress. Concerning a disappointed homebuyer’s legal options for grievance resolution (), the Act provides that the homebuyer can decide whether to go to Consumer Court/NCLT or RERA. As RERA is an exclusive regulation for real estate transactions and defends homebuyers’ interests, a consumer’s approach to the adjudicating officer is preferable. The Act penalizes builders/agents for RERA infractions against homebuyers (). Depending on the offense, the penalty may be revocation, a fine, or a jail term.

4.2. Important judicial decisions

Since the RERDA, 2016, came into force on 1 May 2017, the judiciary’s role has been crucial in defining and applying the Act’s principles in disputes and conflicting views brought in by stakeholders. A brief analysis of the vital judicial decisions of the Indian Supreme Court helps understand the judicial trend and the judiciary’s mindset.

4.2.1. Constitutional validity

The initial period following the implementation of RERDA, 2016, saw a slump in the sector. The builders and agents were unaware of the various provisions of the Act and its implications. Some litigation and court cases arose, questioning the constitutional validity of the Act.

Real estate market actors, especially promoters, questioned RERDA’s constitutionality. They challenged the Act’s validity and application in courts, including India’s Supreme Court. On 4 September 2017, the Supreme Court transferred all connected petitions to the High Court of Bombay (Court) with instructions to hear the cases promptly within two months. Neelkamal Realtors Suburban Pvt. Ltd. v Union of IndiaFootnote25 and several others challenged the constitutionality of RERDA, 2016 in the Court. Finally, on 6 December 2017, the Court held that relevant RERDA, 2016, is legal and constitutionally valid. The Court ruled that the Act applies to ongoing projects after registering it with RERA. In this case, the Act required registration of the ongoing projects because the provisions are retroactive. The promoter might set a revised deadline for the remaining development work during project registration.

Furthermore, it has clarified that the interest provision is not punitive but compensates homebuyers for project delays. The provisions regarding penalties are not retroactive, as they cover events and instances after project registration. There would be no distortion and structural abuse of the stakeholders’ power to ensure the real estate industry’s safety and transparency.Footnote26

4.2.2. Power of other redress agency

The Supreme Court of India clarified the dispute over the jurisdiction issue in a recent verdict in M/S. Imperia Structures Ltd v Anil Patni and Another, Civil Appeal No. 3581–3590 of 2020,Footnote27 hinting that the availability of an alternative solution is no bar to entertaining a complaint under another Act, i.e., the Consumer Protection Act. Hence, the dispute can fall under the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC).

4.2.3. Supreme court cancels Amrapali’s RERA license, lease deeds

On 23 July 2019, the Supreme Court of India directed the government to take stern measures against errant builders such as Amrapali Silicon City Private Limited.Footnote28 In this case, 45,000 homebuyers were involved, canceling their lease deeds for illegalities and ensuring timely delivery of projects. The Court heavily slammed the Amrapali promoters for diverting millions of rupees of hard-earned money from 45,000 homebuyers to fund its promoters’ extravagant lifestyles, such as buying fancy cars and villas. Candidly, the Court canceled its RERA license, lease deeds and handed over its unfinished projects to National Building Construction Corporation. In addition, the Court ordered a money-laundering investigation by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) into the allegations that the developer could have taken money in connivance with banks and authorities. Additionally, the company may face an inquiry under the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA probe) for the possible violation.

4.2.4. Homebuyers treated as financial creditors under the IBC

Over 150 developers challenged the provision treating homebuyers as financial creditors. In Pioneer Urban Land and Infrastructure Limited vs. Union of India,Footnote29 the Supreme Court has upheld the constitutionality of the IBC (Second Amendment) Act, 2018, declaring homebuyers as “financial creditors.” Homebuyers’ remedies under laws such as RERDA, Consumer Protection Act, 1986 (now 2019), and IBC are concurrent. If IBC and other laws conflict, IBC will prevail. In a new judgment in May 2022, the Apex Court upheld homebuyers as financial creditors and had rights, unlike operational creditors.Footnote30 The ruling is a boost for homebuyers.

4.2.5. Supreme court upheld homebuyers’ right to pursue remedies in consumer court

The Supreme Court, in the judgment of M/S. Imperia Structures Ltd v Anil Patni and Another, Civil Appeal No. 3581–3590 of 2020Footnote31 on 2 November 2020 held that homebuyers could approach consumer courts and RERA if a promoter fails to hand over a real estate project on time. The homebuyers can prefer consumer courts for compensation because of deficiency in service (delayed delivery) and invoke the RERA Act’s relevant provisions for proceedings against the builder/promoter for contravening the Act. The Apex Court imposed a fine of fifty thousand rupees on the appellant Imperial Structures for the cost of litigation, payable to the affected homebuyers. It also directed them to pay the penalty imposed by the NCDRC.

4.2.6. Indian supreme court orders more empowerment to the homebuyers

In M/s. Newtech Promoters and Developers Pvt. Ltd. v State of UP & Others, Civil Appeal No (S) 6745–6749 of 2021 and the other eight appeals (Civil Appeal No (S) 6750–6757 of 2021),Footnote32 the Apex Court on 11 November 2021 recommended amending RERDA, 2016, to protect homebuyers’ rights. RERDA’s retroactive application covers all projects, including projects without a completion certificate, even before the enactment of the Act. Before challenging any RERA judgment, the Court required developers to deposit 30% of the regulator’s penalty. The verdict may discourage such builders, who must now deposit the total amount plus interest to do business. The Court ruled that RERA has sole authority to order a refund plus interest, direct interest payment for late possession, or a penalty and interest to the allottee. The adjudicating body can assess compensation and interest to speed up the process.

After RERDA’s implementation, homebuyers through the Forum for People’s Collective Efforts (FPCE) and other organizations have emphasized easing RERA restrictions in several states. Buyers will benefit from the ruling’s unified regulatory framework and improved grievance remedies. Builders must pay a predeposit before appealing a RERA penalty, speeding up decisions for buyers. Developers must follow RERDA/RERA regulations and register ongoing projects before enacting the Act if the relevant authority has not issued a completion certificate. Builders who appealed RERA decisions in previous years must evaluate the circumstances.

The decision might force revisions to State Rules based on the Act.

The review of these five cases suggests that the Supreme Court of India’s judgments have broader implications for builders and lessons for central and state governments. The rulings help homebuyers nationwide. Depending on the situation, the Indian Supreme Court may issue a favorable order.Footnote33

4.3. RERA: implementation status

4.3.1. Rules notification, infrastructure, and grievance redress mechanism

The Act allows state governments to notify Rules, appoint the Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA/Authority) and Real Estate Appellate Tribunal (Tribunal), and host the specific website. shows the Act’s implementation status in Indian states and union territories (UTs). Thirty-five out of a total of 36 states and UTs (97%) have notified their respective Rules, including two newly established UTs in August 2019.Footnote34 The Nagaland state is in the process of legislating its Rules. West Bengal is the only state in the country that did not follow RERDA, 2016; instead, it adopted its Act, West Bengal Housing Industry Regulation Act (WBHIRA), 2017.Footnote35 According to reports, the reason is a political conflict between the center and the state.Footnote36 Some homebuyers believed the Act conflicted with the RERDA (2016)’s provisions. Therefore, a group of homebuyers, the Forum for People’s Collective Efforts (FPCE), challenged this Act’s validity in the Supreme Court,Footnote37 and it is now decided.Footnote38 However, the Government of India had advised the West Bengal government to notify the Rules in conformity with the RERDA, 2016.

Table 4. Implementation Status of RERDA, 2016 as on 11 September 2021

At this point, 30 states and UTs have established their regulatory authority, of which 25 are regular and five are interim. Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, Meghalaya and Sikkim notified their Rules while still setting up their regulatory authority. In the meantime, following the Supreme Court’s judgment, West Bengal has announced its Rules but has yet to establish its regulatory authority. In addition, 28 states/UTs have created Tribunals, of which 22 are regulars, and six are temporary. Five states have only a website format; no details are available. As of 11 September 2021, the total number of projects and agents registered under the Act was 68,900 and 53,995, respectively. The government report35 suggests that with the available infrastructure and mechanisms, 74,183 complaints drew the attention of the redress authorities and were disposed of across the country by the reporting date.

The inference from this development is that the progress and development in implementing the Act so far appear uneven.

4.3.2. State-level modifications to RERA

The review of RERA of all the states suggests that among the 34 states that have notified the Rules, nine states (Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Punjab, Telangana, and Uttar Pradesh) have understandably twisted the Rules, potentially making them more favorable to builders. These states have amended the provisions by excluding ongoing projects from the purview of RERA, the penalty for compounding offenses and project delivery timing.

The dilution in the Rules suggests builders can follow corrupt practicesFootnote39 and harass homebuyers by delaying the project, investing buyers’ hard-earned money elsewhere, chances of cost escalation and compromising quality. A possible fundamental reason for such dilution/modification could be that the Act’s implementation is a state matter. Every state has the authority (power) to change according to the prevailing conditions in the concerned state. In a few cases, political willpower and weak interstate relations work; the builders’ lobby and regulatory capture are imminent.

4.4. Impact analysis

4.4.1. Field investigation: homebuyers’ response

The homebuyers can redress grievances through RERA, Consumer Court, NCLT or Bankruptcy Court. Because of this, both before and after the RERDA, 2016, the options for homebuyers associated with real estate languished in the NCLT. In the process, several projects get delayed. The builders prefer RERA to be the first point for redressing grievances. The developers’ associations have advised the government to create an escalation mechanism, let RERDA act and decide first. If aggrieved parties are unhappy, they can move to a different forum. People are heading to RERA, NCLT, and the consumer forum today, which is unfair. Therefore, the developers and their associations have called for changes in the law. The recently enacted Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Act, 2020, to eliminate bottlenecks and streamline the corporate insolvency resolution process, would affect default builders while benefiting homebuyers. The newly enacted rule requires that at least 100 homebuyers in the project, or 10% of total homebuyers, whichever is less, collectively file a complaint with the NCLT. This complaint should be against the default builder. Apprehension is that because the individual buyer cannot turn to NCLT, the newly introduced provision works against the homebuyers’ interest.

A survey of 540 homebuyers reveals that a single aggrieved homebuyer has no voice or a weak voice against the concerned builder. Homebuyers encounter difficulties out of fear because they are unsure whether to take the defaulting developer to court. Most of the respondents (89%) supported this observation. The other problem that haunts them is that litigation resolution takes longer than stipulated and expected. Because lawyers handled the vast majority of cases, approximately 82% of respondents believed that the defendant’s advocate (s) dragged the matter for convenience, resulting in an excessive delay in resolving the issue. Approximately 78% of respondents believed that builders invariably compromised the quality of their work and obtained compliance primarily through unethical means. Because the Supreme Court has dragged Amrapali to Court over severe violations of the real estate Act, it ensures all homebuyers are aware of the law and have faith in it. Homebuyers’ housing society (or association) management improved significantly during the six years following the implementation of the RERDA, 2016. While confirming this development, 63% of the buyers expressed that builders possessed the upper hand because of their closeness to the power corridor. They believed a concerted effort through their association to fight for their rights could lead to a more pleasant, hassle-free quality of living and bring peace of mind. depicts the findings of the interview on the impact assessment of the Act on homebuyers.

The Appendix shows that approximately 80% of respondents who were either retired or service holders had invested their hard-earned savings in buying their dream home worth less than Rs 10 million, with a significant portion of the money coming from a housing loan from the office/bank. Arguably, this indicates that they belonged to the middle-class category who would afford otherwise. While 69% paid more than 50% of the cost, they suffered a delay in possession by more than 18 months. On the one hand, paying interest on a home loan and, on the other, staying in a rented house or paying the additional cost of retaining official accommodation or similar, delaying the possession of a dream home, pinches their pockets. Among them, almost 72% were aggrieved because of the builder’s delay in possession.

On the other hand, some homebuyers (28%) were loyal to the builder because of their family linkage, friendship and closeness as raw materials suppliers/service providers. Because of this, they preferred not to air any grievances and compromise with the prevailing conditions. Of the aggrieved, 60% filed formal complaints, and 51% filed cases before the RERA (22% completed and 30% pending). Almost 83% of complainants pursued individual cases on their own. Regarding the effectiveness of the Act’s redress mechanism, 75% of homebuyers rated it as very good or good, indicating that they have faith in the system. However, the complainant homebuyers with favorable orders (23%) expressed concern about its timely implementation. To ensure the order’s enforcement, nearly 62% of them had to take additional steps, such as filling out an execution application. The respondents’ discussion reveals that the builder had resorted to harassment of homebuyers for some reason. They used oppressive measures such as unjustified penalties for late payment of installments, canceling the deed and selling it to others for a higher price, disconnecting essential services, and abusing and threatening people. Some cases narrated below are eyebrow-raising.

While attending 32 apartment society (management) meetings and in-depth interaction with respondents, a few terrifying and interesting facts surfaced that merit mention here to understand the nature and degree of builders’ wrath and the effect of RERDA, 2016. Respondent 247 narrated her own horrifying story about the builder’s repressive attitude and her helplessness. For nearly two decades, her woes began with local authorities, including the police, seeking protection from the State Consumer Dispute Redress Commission for the disconnection of power and water supply and the Registrar of Companies Office to collect information about the company’s true identity. Respondent 91 was deeply disturbed by how the builder defrauded him by taking two cheques in advance at the booking time for encasing with prior notice. Still, the respondent faced a criminal case filed by the builder for bouncing a check in a disputed installment payment issue. Respondent 510, who owns the unit with his wife, explained how his police complainant turned crime branch investigation took about two years. The study finally determined that the owner occupied the apartment without a local authority’s clearance certificate. Thus, the complaint was closed due to the misstatement of facts. The respondent’s angst stemmed from the fact that the investigating officer had acted for extraneous reasons.

The story of respondent 98, who was instrumental in forming the owners’ society to combat the mighty builder, suffered collectively due to factionalism among the owners-one group favoring the builder. An encroachment case about the disputed apartment was pending before the registering authority for more than ten years, and respondent 98 was an intervened petitioner. The owners of several flats (condominiums) registered their units with their local authorities without obtaining a license from the appropriate sources. Still, the builder managed to move freely with the landowner’s irrevocable power of attorney. A respondent (221) who was the founder and President of the apartment society narrated how the builder harassed the office bearers of the flat owners’ (homebuyers) association just before implementing RERA because of legal recourse taken by the owners’ association collectively. The issues were that they had no right to information; obtaining property documents was difficult. The legal right to compensation was absent if they did not receive the property as agreed. In any case, the right to claim a refund from the builder was unthinkable. Seven homebuyers (Respondents (27, 129, 142, 310, 325, 411, 507) expressed how they proceeded to RERA court for grievance settlement without fear and confidence and expressed satisfaction about the development and outcome.

4.4.2. Field investigation: builders’ and experts’ response

Most of the developers with multiple responses (86%) viewed that the delivery delays were because of financial issues, approval delays including environmental clearance, market conditions, and the developers’ negligence. There were delays in obtaining raw materials (like cement and steel), workers who didn’t know what they were doing, and problems with civil contractors running their businesses. However, some builders wanted to keep their reputation and promises, so they put a penalty clause in their contracts. About 64% of developers attributed delays in delivery to market conditions. These included government policies and legislation, interest rates, tax incentives, deductions and rebates or subsidies, and investment potential. Inadequate or improper project financing, high unsold inventory and a growing proportion of stalled projects caused delayed delivery (49% of developers’ responses). There were compromising opinions on developers’ negligence causing the delay. Views (41%) were that some homebuyers’ associations or individuals complained of political reasons or extortion.

According to builders’ understanding, the average score of awareness of the Act among urban homebuyers was 60%. Similarly, the Act’s effectiveness in grievance redress was 53%. On the harassment question, the majority of respondents avoided answering, and some replied that it was a misunderstanding or a miscommunication. However, one-way ANOVA analysis reveals that the p-value (0.0131) is significant at a 5% level (), implying that the results are random. Therefore, we reject the hypothesis that the Act is ineffective in protecting the homebuyers’ interests and accept the alternative notion that the Act has empowered the homebuyers.

Regarding variations in respondents’ opinions across the regions/zones, , through the chi-square test, explains no significant differences in two factors, i.e. delay in delivery (χ2 6.745) and view on harassment (χ2 5.065) across the zones. Therefore, the hypothesis H₁ = fdt = fbh is accepted, implying that the respondents’ opinions follow a similar trend across the zones. However, the other factors, awareness of the Act (χ2 16.785) and view on grievance redress (χ2 22.96), are significant, resulting in the rejection of hypothesis H₂ = faa = fgr. The implication is that the Act has a variable impact on homebuyers across the country. The variation is possible because implementing the Act and creating awareness are state subjects, and states have different approaches.

4.4.3. Impediments

Inadequate infrastructure and workforce hinder the timely resolution of many RERA complaints. Most states follow the makeshift workFootnote40 system. Some states have trouble recruiting RERA members, while others lack a fully equipped office with administrative support and infrastructure. RERA’s staff and infrastructure are insufficient to handle consumer complaints. RERA is not booming yet, because even after six years, it is still not preventing corruption/malpractices.Footnote41

The implementation of RERA orders is another challenge for authorities and homebuyers. Inbuilt constraints prevented authorities from executing several homebuyer-friendly orders. According to RERDA 2016, an execution order must be completed within a set timeframe. The promoter’s or real estate agent’s penalties/compensation is recoverable as land revenue arrears.Footnote42 The authority has no power to issue directives to any agency, so ensuring proper action is challenging. Homebuyers who hoped for RERA were trapped in dud projects. Most states have not adequately implemented it six years later, frustrating homebuyers. In RERA-enabled states, most of its orders fail to execute.Footnote43 RERA authorities in all states have recently agreed to issue a recovery warrant, placing it with the district administration to recover arrears from penalties or unpaid fees. However, this problem persists.

However, the analysis above gives a broader view of the Act’s impact on people and society. , the Fishbone diagram, shows the analytical views of the impact assessment.

5. Discussion

A lively debate regarding the valueFootnote44 of data creation is going on among academics and researchers. The presumption is essential for both effective policy and commercial prospects to guarantee that society as a whole benefits from data-driven economic developments (Coyle & Diepeveen, Citation2021). Following this, we need to learn more about the implications of value from different kinds of data generated and analyzed in this research and share its contribution for future references. Based on this premise, the discussion section covers three aspects: our findings’ linkage to past studies, practical insights and policy implications.

5.1. Relevance to past research

Before the Act’s implementation, homebuyers lacked information and property documents. If they didn’t get the property as promised, they had no legal recourse and no refund from the builder. The regulatory controls were lax. We agree with Bledsoe’s (Citation2019) contention that the Act’s implementation and intense judicial interventions give homebuyers who struggled before RERDA hope. Barker’s (Citation2008) and Brinkmann’s (Citation2009) observations that builders and real estate agencies create complex ethical issues are still visible. We agree with Haase et al. (Citation2021) that housing development needs state support to improve the live-work mix.Footnote45 Today, India has strict laws and rules to control the real estate business, protect consumers’ interests, and serve society as a whole.

The Act’s provision of an “Escrow account” has reduced builders’ chances of misappropriation/misuse of homebuyers’ advance payments/installments. The result is confident homebuyers. The Act’s provision allowing complainants to file a case without a lawyer empowers homebuyers. These components contribute to Bledsoe’s (Citation2019) idea of humanizing housing and quality of life.

A novel and distinct research dimension emerged during meetings with homebuyers’ society management. Cash-strapped buyers enter into presale agreements to buy with small down payments as home prices rise. Presales are an excellent short-term investment due to their high leverage and low transaction costs. Builders use presale to raise funds for construction projects and reduce price fluctuations by negotiating a favorable transaction price early in the development process. These observations support Li and Chau’s (Citation2019) findings on developer presales.

5.2. Practical insights

The narratives on homebuyers’ responses reveal their emotional anguish and the mood of governing/regulating agencies and the market. Homebuyers (consumers) must educate themselves more, seize opportunities without fear, and ensure that the “Consumer is King”. However, the Indian regulatory mechanism influenced by politically-linked industrial groups impacts regulatory governance and cripples the empowerment process (Burman & Zaveri, Citation2016; Dubash & Rao, Citation2008). Referring to Levien (Citation2021), we observe another hindering factor: informal land-grabbing by the land mafiaFootnote46 is rising in India. Land mafias involved in property and real estate show inadequacies in prevailing approaches to corruption and propose taking capitalism, coercion, and corruption seriously.

Besides, the Indian political system weakens regulatory governance and threatens the purpose of establishing independent regulatory agencies to depoliticize decision-making.Footnote47 In Kochi, Kerala, the 2006 construction of four high-rise flats breached environmental standards, exposing the nexus between builders and power corridors. Following a 2007 High Court stay order, the builders completed the project and sold it with the help of influential people, highlighting the industry’s impact on regulatory governance. Following the Supreme Court’s demolition directives, residents silently protested with political backing. Informality, planning violations, and corruption hamper Indian urban planning (Sundaresan, Citation2019). Examining RERDA and State Rules reveals that the real estate sector lobby continues to exert regulatory power. Against this, we observe Chikermane and Agrawal (Citation2020) claiming that the federal and state governments and their regulators did well with RERDA, 2016, ensuring residents’ convenience in the organized real estate industry. These observations imply that the Act empowers homebuyers in varying degrees to counter builders’ exploitation. Judicial actions improve homebuyer confidence. However, relying on the arguments of Y.-S. Lee (Citation2017), we believe that political will is essential for the Act’s timely and successful implementation, which is missing in some states.

Regarding violating or ignoring ethics, we observe that real estate associations’ codes of ethics clearly state an underlying commitment to morality. Most standards of practice provide detailed guidelines and rationale for proper professional conduct. However, its members, particularly promoters/builders, have frequently violated these provisions. Despite the common perception of unethical behavior in real estate,Footnote48 the principle of “rational choice theory”, i.e., individuals making decisions based on self-interest, persists. We believe Barker’s (Citation2008) argument that the case still poses challenging ethical questions is valid even today.

5.3. Policy implications

A line on RERDA’s contribution to economic growth appears significant. India regards the Act as a boost to the sector’s growth with fiscal incentives. The India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF) predicts a $9.30 billion industry by 2040, up from $1.72 billion in 2019.Footnote49 Market capitalization will reach $1 trillion by 2030, up from $120 billion in 2017, contributing 13% to GDP.Footnote50 Furthermore, the government claims that the Act helped India to improve its ease of doing business (EoDB) ranking to 63/190 in 2019 from 77 in 2018 and 100 in 2017, suggesting its continuous efforts to become a hub destination for more FDI.Footnote51 The impact of this factor on the economy is debatable and needs investigation.

The Act prepares the industry for healthy growth through improved regulation and transparency. We agree with Gilbert and Gurran’s (Citation2021) assessment of the reform’s influence on housing approvals, especially for higher-density infill buildings that local governments wouldn’t have allowed. The 2016 RERDA aims to achieve this. We agree with Bardhan and Kroll (Citation2007) claim that housing and real estate rules affect competition and economic and social control.

Finally, analysis and discussion show that the 2016 real estate law affects economic development law and policy (Crepelle, Citation2021). We support Munasib et al. (Citation2014) and Y.-S. Lee (Citation2017) that regulatory framework reforms have mixed effects. Some worry that authorized laws and rules alone will not generate the desired results. Some laws and norms are not enforced in many countries, while others are selectively enforced or impossible to implement.Footnote52 India’s the same. However, the industry appears confident of healthy development with increased regulation and openness.

6. Conclusion, limitations and future research

6.1. Conclusion

The RERDA, 2016, entered into effect on 1 May 2017, to promote openness and accountability in real estate and housing. The Act is one of the government’s most critical initiatives to regulate the unregulated and uncontrolled real estate sector for homebuyers and other stakeholders. Examining the Act and its postimplementation phase reveals it initially faced various hurdles, including constitutional legality, and filed several cases for adjudication. Due to competing federal (interstate) relations, the Act’s smooth implementation by some state governments is a hindrance. In one state, it breaches the central Act while twisting state-framed Regulatory Authority Rules in eight builder-friendly states. Recovering penalties and compensation from builders is another obstacle to the implementation of RERA by the authorities. With the early impediments cleared by the courts, it is now bearing fruit, and homebuyers are getting relief from builder exploitation and harassment.

Even after six years of implementation, growth and improvement in implementing the Act are uneven. We answer the research question about the Act’s impact on homebuyers and society favorably, concluding that overall, the Act gives homebuyers legal protections. Still, builders are influential, making homebuyers subservient to harassment and legal battles. The Indian government’s approach to redressing the woes of homebuyers needs substantial improvement in a challenging political environment. Our findings on the impact of the real estate reforms could assist policymakers, and development planners, in modifying existing rules in the globalized competitive environment. However, finally, the general observation we derive is that the success of legislation in a country’s development relies on political will, its design, particularly its alignment with development goals, its flexibility and effectiveness, and its adaptation to socioeconomic situations. Regarding ethical issues, the conclusion emerges that the Indian real estate market is still subservient to unethical business practices through builders’ violations of law and regulations. This includes market and customer exploitation. Because this article is empirical, it adds to the corpus of knowledge about the subject with a future direction.

6.2. Limitations and scope for future research

The study did not consider failed homebuyers as profoundly as other market participants. A socioeconomic analysis of newly enacted legislation may show a price effect on housing supply and demand. Additionally, we did not study the reasoning of the government or policymakers for linking the real estate Act to FDI inflows or EoDB ranking. We agree with Paul and Benito (Citation2018) that cross-country comparisons of FDI in developing economies are challenging, but it provides scope for further research. The other limitation is methodological: the nonavailability of a sampling frame of the homebuyers’ population, although random sampling is possible with data availability. Future studies will be able to validate this proposition through these dimensions. These dimensions validate the proposition by expanding future research. In the future, researchers may look at informal and slum housing as urban phenomena to compare and evaluate urban housing policies. An exciting new direction for future research in real estate and related fields is to compare the costs and benefits of rules systematically.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions that helped prepare this paper for publication in its current form.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

Sources of secondary data have been duly acknowledged. Primary data sharing is restricted due to confidential nature of data collection.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Neelam Chawla

Dr. Neelam Chawla is serving as an Associate Professor at Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies, Guru Govind Singh University, New Delhi, India for more than twelve years. She specialises in business and corporate laws. She follows the same research pursuit along with governance and public policy, corporate social responsibility, civil society and women empowerment.

Basanta Kumar

Dr. Basanta Kumar, post-retirement from Utkal University, India, is an Academic, Research, and Legal Advisor. Now he practices in the Orissa High Court. He is an avid researcher in the areas of laws and regulatory reforms, consumer rights protection, microfinance interventions, governance and public policy, CSR, public distribution system, housing and real estate industry, and micro and small enterprise development. Dr. Kumar is a certified Publons Reviewer. He works closely with the Academy of Business and Emerging Markets (ABEM) in Canada, the Asia Pacific Consortium of Researchers and Educators (APCoRE) in Manila, and the European Marketing Academy (EMAC) in Belgium.

Notes

2. See http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Making_Affordable_Housing_A_Reality_In_Cities_report.pdf accessed on, vol. 26, no. 01, p. 2020. 2019.

3. First National Housing Policies in India was formulated in 1988 and the recent one is National Urban Housing and Habitat Policy 2007.

4. http://ficci.in/sector/59/project_docs/real-eastate-profile.pdf. Even the Indian real estate markets were under-perform the stock market over 1998–2005 (Newell & Kamineni, Citation2007) .

5. Also see https://www.thehindu.com/real-estate/cracking-down-on-fraudulent-builders/article34280021.ece

6. Real estate development was rife with delays and defaults. Homebuyers were usually left in the lurch when the developer repeatedly delays completing apartments. As a result, the government passed the RERDA, 2016 (See the Supreme Court of India judgment in Civil Appeal No. 6239 of 2019 between Wg. Cdr. Arifur Rahman Khan & Aleya Sultana & Ors v DLF Southern Homes Pvt. Ltd. available at https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2019/27240/27240_2019_33_1501_23551_judgment_24-Aug-2020.pdf). Also see how the builder exploits the homebuyers at https://bengaluru.citizenmatters.in/be-careful-while-buying-an-under-construction-property-5827

8. Artificial scarcity (supply shortage) results in housing unaffordability (See https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2016/4/20/affordable-housing). A significant demand-supply gap which is the highest in low and middle-income segments exists in the residential housing segment of the Indian real estate market. In certain cities, demand outweighs supply three to four-fold (see https://www.ibef.org/download/Affordable-Housing-in-India-24072012.pdf.).

10. Homebuyer in the present research refers to a person/buyer defined as “allottee” in the RERDA, 2016 (s.1(d) to whom a plot/ apartment/ building is allotted/sold (freehold/leasehold)/transferred by the promoter and the person who later acquires the same allotment by sale/transmission/otherwise. It excludes the person to whom such a plot, apartment or building, as the case may be, is given on rent.

12. The National Building Code of India (NBC), initially introduced in 1970 and revised from time to time, with the most recent revision in 2016, is a national document that provides principles for controlling building construction operations throughout the country. See the Code at https://www.bis.gov.in/index.php/standards/technical-department/national-building-code/#:~:text=The%20National%20Building%20Code%20of,Code%20for%20adoption%20by%20all.

13. NAR-INDIA, founded in 2008, is a non-profit organization formed by the leading representative body and advocacy organization for persons involved in Real Estate Transaction Advisory to serve as the collective voice of Indian realtors. Its objective is to establish the highest standards and certification in the real estate market while facilitating professional growth for its members. See the Code at https://www.narindia.org/code-of-ethics.php.

14. No FDI was allowed in the Indian real sector before 2005, except for non-resident Indians and overseas corporate bodies. The government permitted 100% FDI in the housing infrastructure development projects subject to specific terms and conditions in 2005. FDI equity inflows in the industry during 2009–2013 were low, so the government relaxed the terms and conditions to attract more FDI. In 2018, 100% FDI under the automatic route was allowed. For details, see https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1549548

15. See the legislation at https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A2016-16_0.pdf

16. Shelter for protecting people, house is a denotative concept, meaning a small dwelling explaining the building’s physical structure

18. See for reports, minutes and notification about various housing and real estate issues at https://mohua.gov.in/cms/notifications.php

19. Divorce opinions exist about defining “middle-income settlers”. We consider people earning typically in the range of US $10 to $100 per day as defined by World Bank/OECD/ India’s National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER). Hence, the scope of this research excludes slum housing/informal housing.

20. Assumption-small nuclear family norms, one unit for self-occupation, the other two for a gift to son (s) and/daughter (s); may be for rent temporarily.

21. Order was passed on 8 May 2019 to demolish four apartments- Jains Coral Cove, Golden Kayaloram, H2O Holy Faith and Alfa Serene. The state government was to pay compensation to each owner Rs. 25 00,000 before demolition. Forty residents of Golden Kayaloram petitioned the Supreme Court for a rehearing, but the Court denied it. The Court quashed the industry body Confederation of Real Estate Developers Association of India (CREDAI) plea to reverse the demolition order on 25 October 2019. The final demolition took place on 12 January 2020.

22. The Supreme Court of India penalized the builder for violating ethical business practice through a judgment in July 2019.

23. Also known as the Ishikawa diagram or cause and effect diagram.

24. The newly enacted Consumer Protection Act, 2019, effective from 9 August 2019, has strengthened homebuyers’ grievance settlement mechanism. https://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2019/210422.pdf

25. Combined judgment of Bombay High Court in Writ Petition No. 2737/ 2017 together with other 10 cases at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/82600930/.

28. Supreme Court’s judgment details in Bikram Chatterji & Ors v. Union of India, Writ Petition(C) No. 940/2017

29. See judgment dated 9 August 2019 in Writ Petition(s)(Civil) No. 43/2019. Also refer IBC (Second Amendment) Act, 2018 and explanation to Section 5(8; f), Section 21(6A)(b) and Section 25A of the IBC.

30. See combined judgment in Civil Appeal No. 2221/2021 and 2367–2369/2021 [New Okhla Industrial Development Authority (NOIDA) v. Anand Sonbhadra, Manish Gupta and others…etc]

33. In one public interest litigation known as “PIL”, the Indian Supreme Court, on 17 January 2021, advised the Central Government to bring a model “builder-buyer” and “agent-buyer” agreement to safeguard middle-class homebuyers, which shall apply to the whole country. The reason for this is the attempt to include various conditions in the contract such that the average person may be unaware of their implications. See details in https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/it-s-important-to-have-model-builder-buyer-agreement-supreme-court-121100500039_1.html.

35. WBHIRA)-2017 was notified on 1 June 2017, almost one year after the promulgation of the central Act-RERDA, 2016.

37. Mishra (2019). https://www.proptiger.com/guide/post/bengal-notifies-own-real-estate-act-homebuyers-stand-to-lose.

38. Indian Supreme Court in Writ Petition No. 116/ 2019 on 4 May 2021 has struck down the Act ordering WBHIRA-2017 is unconstitutional and in conflict with RERDA, 2016. The state is bound to legislate new Rules soon. For more case details, see https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2019/2356/2356_2019_35_1501_27914_judgment_04-May-2021.pdf

39. India figures at 85 out of 180 countries in the corruption perception index of 2021 (see https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021/index/ind). According to Transparency International India’s 2019 report, 56% of people paid a bribe and 61% were unaware of a state hotline/helplines to report corruption.(see https://transparencyindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/India-Corruption-Survey-2019.pdf).

40. Retired people on contract or on deputation from other departments

41. The statement is based on several judiciary reviews of real estate litigation and feedback from field study.

42. See section 40, RERDA, 2016.

43. See Bombay High Court judgment in Arun Parshuram Veer vs State of Maharashtra and Others in WP No. 2159 of 2021. The Maharashtra RERA issued a recovery warrant against the builder and forwarded it to the District Collector. There was no execution of the order, and the Maharashtra RERA was silent. Finally, the homebuyer landed in the Bombay High Court for execution.

44. By “value,” we mean the economic concept of “social welfare,” which is the overall (economic) well-being of all of society, including individual incomes and needs, and non-monetary benefits like convenience, housing, or health. Specifically, “value” refers to the viewpoint of society.

45. The term “live-work mix” refers to real estate that combines residential space with business or manufacturing space.

46. Land mafias are those engaged in land and property-related corruption.

47. https://theprint.in/opinion/state-regulation-in-India-the-art-of-rolling-over-rather-than-rolling-back/216,647/. Policymakers decide on regulations mainly in four ways: expert, consensus, benchmarked or empirical. A trusted expert makes the expert decision, and political representatives take consensual decisions on political priorities. Benchmarked decisions are based on an external model, while empirical findings depend on fact-finding and analysis to specify action parameters (OECD, Citation1997, pp.14–15). India relies on this guidelines.

48. See, Wolverton and Wolverton (Citation1999).

52. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/25880/9781464809507_Ch03.pdf. Accessed 29 September 2021.

References

- Acolin, A., Hoek-Smit, M., & Green, R. K. (2021). Measuring the housing sector’s contribution to GDP in emerging market countries. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijhma-04-2021-0042

- Arku, G. (2006). The housing and economic development debate revisited: Economic significance of housing in developing countries. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 21(4), 377–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-006-9056-3

- Armstrong, J. W., & Frankot, E. (Eds.). (2020). Cultures of law in urban Northern Europe. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429262869

- Asiedu, E. (2002). On the determinants of foreign direct investment to developing countries: is Africa different? World Development, 30(1), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0305-750x(01)00100-0

- Asiedu, E., & Lien, D. D. (2010). Democracy, foreign direct investment and natural resources. SSRN Electronic Journal. (December), 1-39. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1726587

- Bachelard, G. (2014). The poetics of space. Penguin.

- Bardhan, A., & Kroll, C. A. (2007). Globalization and the Real Estate Industry: Issues, Implications, Opportunities 1. Haas School of Business, Cambridge. http://web.mit.edu/sis07/www/kroll.pdf

- Barker, D. (2008). Ethics and lobbying: the case of real estate brokerage. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9434-0

- Bartram, R. (2019). The cost of code violations: how building codes shape residential sales prices and rents. Housing Policy Debate, 29(6), 931–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1627567

- Berry, J., McGreal, S., Stevenson, S., & Young, J. (2001). Government intervention and impact on the housing market in Greater Dublin. Housing Studies, 16(6), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030120090520

- Biyase, M., & Rooderick, S. (2018). Determinants of FDI in BRICS countries: panel data approach. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai Oeconomica, 63(2), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.2478/subboec-2018-0007

- Bledsoe, C. (2019). The humanization of housing: coliving and Maslow’s hierarchy of “We”, NewCities. June 6. https://newcities.org/the-big-picture-humanization-housing-coliving-maslows-hierarchy/ (accessed 14 May 2021)

- Bogart, W. A. (2002). Compliance with law – deterrence and its alternatives. In Consequences: the impact of law and its complexity (pp. 53–81). University of Toronto Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10 .3138/9781442673267.6

- Boone, H. N., & Boone, D. A. (2012). Analyzing likert data. Journal of Extension, 50(2), 1–5. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol50/iss2/48

- Bornstein, M. H., Jager, J., & Putnick, D. L. (2013). Sampling in developmental science: situations, shortcomings, solutions, and standards. Developmental Review, 33(4), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2013.08.003

- Bramley, G. (2012). Affordability, poverty and housing need: Triangulating measures and standards. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 27(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-011-9255-4

- Breuer, W., & Steininger, B. I. (2020). Recent trends in real estate research: A comparison of recent working papers and publications using machine learning algorithms. Journal of Business Economics, 90(7), 963–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-020-01005-w

- Brinkmann, J. (2009). Putting ethics on the agenda for real estate agents. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0099-8

- Brodaty, H., Mothakunnel, A., de Vel-Palumbo, M., Ames, D., Ellis, K. A., Reppermund, S., Kochan, N. A., Savage, G., Trollor, J. N., Crawford, J., & Sachdev, P. S. (2014). Influence of population versus convenience sampling on sample characteristics in studies of cognitive aging. Annals of Epidemiology, 24(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.10.005

- Burman, A., & Zaveri, B. (2016). Regulatory responsiveness in India: A normative and empirical framework for assessment. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2888310

- Büthe, T., & Milner, H. V. (2008). The politics of foreign direct investment into developing countries: increasing FDI through international trade agreements? American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 741–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00340.x

- Çakërri, L., Muharremi, O., & Madani, F. (2021). An empirical analysis of the FDI and economic growth relations in Albania: A focus on the absorption capital variables. Risk Governance and Control: Financial Markets and Institutions, 11(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.22495/rgcv11i1p2

- Cheng, Z., Prakash, K., Smyth, R., & Wang, H. (2020). Housing wealth and happiness in urban China. Cities, 96(January), 102470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102470

- Chikermane, G., & Agrawal, R. (2020). Regulatory changes in India in the time of COVID19: lessons and recommendations. ORF Special Report No. 110. Observer Research Foundation. June. https://www.orfonline.org/research/regulatory-changes-in-india-in-the-time-of-covid19-67604/.

- Courchane, M. J., & Ross, S. L. (2019). Evidence and actions on mortgage market disparities: research, fair lending enforcement, and consumer protection. Housing Policy Debate, 29(5), 769–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1524446

- Coyle, D., & Diepeveen, S. (2021). Creating and governing social value from data. SSRN Electronic Journal. November 28, 1-32. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3973034

- Crepelle, A. (2021). White tape and Indian wards: removing the federal bureaucracy to empower tribal economies and self-government. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 54(3), 563–610. https://doi.org/10.36646/mjlr.54.3.white

- D’Souza, R. (2019). Housing poverty in urban India: the failures of past and current strategies and the need for a new blueprint. ORF Working Paper 187. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ORF_Occasional_Paper_187_HousingPoverty.pdf.

- Da Cunha, A., Mager, C., Matthey, L., Pini, G., Rozenblat, C., & Véron, R. (2012). Urban geography in the era of globalization: The cities of the future Emerging knowledge and urban regulations. Geographica Helvetica, 67(1/2), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-67-67-2012

- Dimri, S. (2019). Regulation of real estate transfers and protection of buyers’ interest: A perspective on legal and institutional developments in India. ournal, 22 (14), 1-13. Papers.ssrn.com. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3759289

- Dixon, L., Gates, S. M., Kapur, K., Seabury, S. A., & Talley, E. (2006). The impact of regulation and litigation on small business and entrepreneurship an overview. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/2006/RAND_WR317.pdf

- Doling, J., Vandenberg, P., & Tolentino, J. C. (2013). Housing and housing finance - A review of the links to economic development and poverty reduction. SSRN Electronic Journal. 362, 1-42. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2309099

- Dubash, N. K., & Rao, D. N. (2008). Regulatory practice and politics: lessons from independent regulation in Indian electricity. Utilities Policy, 16(4), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2007.11.008

- Gabriel, S. A. (1996). Urban housing policy in the 1990s. Housing Policy Debate, 7(4), 673–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1996.9521238

- Gastanaga, V. M., Nugent, J. B., & Pashamova, B. (1998). Host country reforms and FDI inflows: how much difference do they make? World Development, 26(7), 1299–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0305-750x(98)00049-7

- Gibb, K., & Hoesli, M. (2003). Developments in urban housing and property markets. Urban Studies, 40(5–6), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000074227