Abstract

While access to finance is a key link between economic opportunity and economic outcome, it remains a major barrier for aspiring entrepreneurs. The current research aims to conduct an in-depth case study of Assadaqaat Community Finance (ACF), a unique UK-based community finance institution with the objectives of addressing the global challenges of financial exclusion and social and economic inequalities through entrepreneurship and self-employment. ACF offers free professional training using an innovative and ground-breaking financial model based on Islamic financial principles via the ACF Cycle of Shared Prosperity framework. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 participants including beneficiaries, benefactors and founders to explore the impact of ACF training, advice and mentoring and access to interest-free and debt-free finance in helping participants overcome the challenges and develop feasible business plans for their micro, small and medium enterprises. The results suggest that the beneficiaries are happy and become financially independent within 3–6 months, resulting in the transformation of beneficiaries into benefactors as they are able to contribute back to ACF. We highlight the transformational nature of this unique institutional business model and its applicability for existing Islamic MFIs, allowing them to make a clear contribution to development of sustainable communities. We also argue that the ACF financial model offers a sustainable solution to overcome global challenges and contribute towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

1. Introduction and motivation

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) and non-profit organisations grant loans to allow the recipients to realise entrepreneurial ventures and climb out of poverty. The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Yunus Muhammad in 2006 gave a worldwide stamp of approval to microcredit strategies and how they can be used to combat global poverty (Armendáriz & Morduch, Citation2010). However, the world of microfinance has been unable to ensure transparency in its operations despite significant criticism (Rhyne & Otero, Citation2007), and there has been debate on the effectiveness of such operations and their impact on the impoverished. There has also been a significant increase in transparency requests due to an increasingly discerning charity sector, and there remain concerns about MFIs’ mission drift, ethical risks and sustainability, whereby the best-fitting model remains unclear. There is also an ethical crisis in microfinance (Hudon & Sandberg, Citation2013) concerning profit-making mechanisms, and the fight against poverty requires a selfless outlook (Marshall and Keough, Citation2004). While subsidies and donations can be used as resources to help microfinance organisations succeed, and may initially appear helpful, they may actually hinder the effectiveness, efficiency, and viability of MFIs in the long run.

While numerous studies have established a relationship between religiousness and world development (e.g., Marshall and Keough, Citation2004; Haar and Ellis, Citation2006), there is still lack of research explaining how and in what sense an innovative Islamic business model can transform communities using the Islamic financial principles specially the instrument of Assadaqaat. This is a unique instrument which has never been used for entrepreneurship development and financial empowerment. This is despite the fact past literature (e.g., Weber (2002) have argued for an association between religion and economics. For example, Haar and Ellis (Citation2006) stated that religious beliefs give ethical guidance and assist people in developing their lives. Others provide evidence for MFIs as providers of training efforts, thereby identifying the differences between Christian and secular MFIs in various dimensions of organisational performance (Okuda and Aiba, Citation2016).

However, the effect of religious actors on modern microfinance has not been rigorously addressed. For example, Bussau and Mask (Citation2003) outlined the theological reasons why Christian actors should care about microfinance and entrepreneurship, while Harper et al. (Citation2008) described MFIs from three religions (Islam, Christianity, and Hinduism). Rulindo and Pramanik’s (Citation2013) study of 400 Muslim microentrepreneurs showed that the majority of whom received Islamic microfinance, found that spiritual and religious enhancement programmes benefitted them. Similarly, Ahmad (Citation2020) surveyed 543 conventional and 101 Islamic MFIs operating in Islamic and non-Islamic countries to compare the social performance and financial sustainability of conventional and Islamic MFIs. The study showed that Islamic MFIs outperform conventional MFIs in terms of outreach but not financial performance, suggesting that sustainability, interest costs and MFI mission drift concerns remain (Mersland & Strøm, Citation2010; Hartarska & Mersland, Citation2012; Ahmad, Citation2020).

We aim to contribute to this field by identifying and discussing the relevance of a unique business sustainable model for MFI based on Islamic Finance principles that is particularly applicable in the post-Covid-19 era in the sense of creating value not only for the followers of a particular faith group but across all segments of the society. To this end, we conducted interviews to delineate the unique business model of Assadaqaat Community Finance (ACF), a UK-based MFI that grounds in Islamic values. Our findings reveal that those who benefit from ACF are not only happy but become financially independent within 3–6 months, at which point they can contribute back to ACF as benefactors. We report that ACF is an inclusive organisation that offers financing to people regardless of their faith, with philanthropy lying at the core of its mission. As per our findings, ACF particularly focuses on financially empowering people from underserved communities, and the organisation attempts to understand the challenges and barriers that communities face via collaborative and community-focused programmes. This finding is in line with the notion that religion and MFIs are closely related elements with a substantial influence on society (Hoda & Gupta, Citation2016).

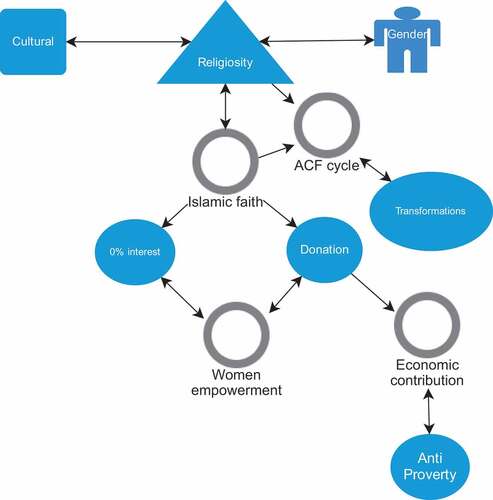

We also discover that ACF’s financial strategy is based on financial support for communities, and it has demonstrated social and economic success. The ACF Entrepreneurship Programme trains and mentors future entrepreneurs while also providing interest-free finance to help micro, small, and medium-sized firms get started. We find that the ACF Women Empowerment Programme enables young women to realise their full potential and put their business ideas into action.

Guided by stakeholder theory, we discover the intersection of religion, gender, and culture having a substantial impact on economic development, and women benefit greatly from the financial and non-financial resources made available via the ACF Training Programme, which includes moral support. Finally, we discover that ACF offers a secure platform for donations of any magnitude from individuals, philanthropists, public/private/corporate bodies, trusts or foundations. These donations enable ACF to empower individuals without undermining their self-esteem, thereby gradually transforming today’s beneficiaries into tomorrow’s benefactors.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. The second section presents a detailed review of prior studies and poses the research question. The third section describes the sample and research methods. The findings and analysis are presented and discussed in the fourth section. Finally, the fifth section presents the concluding remarks.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical and empirical studies

Stakeholder theory asserts that organisations can gain and retain the support of their component groups or stakeholders by addressing and balancing their respective interests (Reynolds et al. Citation2006). Freeman (Citation1984) suggested that for efficient administration, organisations must meet the needs of different stakeholders. Later theorists distinguished between “internal stakeholders” and “external stakeholders” (Jones, Citation1995), referring to the firm’s board members, managers, and workers on the one hand, and its customers, suppliers, government, regulatory agencies, rating agencies, and the community on the other hand. Each of these parties has unique expectations of the MFI, and they can also serve as control mechanisms. For instance, the government organisations that oversee and monitor an MFI represent an external governance system, while its board functions are an internal control mechanism (Hartarska Citation2005). The conflicting aims of MFIs, namely to retain sustainability and expand their reach, indicate that stakeholders have different priorities in defending their interests. Research on organisational behaviour (Middleton, Citation1987; Cornforth, Citation2005) has evaluated the role, involvement, and results of stakeholders in organisational decision-making processes. According to Hartarska (Citation2005, p. 4), funders may choose outreach over sustainability, whereas private investors favour sustainability over outreach.

It is widely recognised that MFIs have a unique significance in emerging economies, although their success varies by nation, culture, and environment. Sinha and Ghosh (Citation2021) documented the organisational sustainability perspective of MFIs based on the experiences and perceptions of MFI managers in a developing market. By examining a holistic and organisation-centric approach and relying on stakeholder theory, Sinha made an important contribution by analysing the impact on women borrowers in terms of their financial sustainability and empowerment. This is relevant to this research because it provides a framework for describing the environmental elements that influence the aims of credit unions in delivering microfinance services. Since credit unions and financial cooperatives are membership-based, and hence co-ownership based, their internal stakeholders often implement stringent control procedures to guarantee that the efficiency and outreach objectives are met. Ben-Ner and Van Hoomissen (Citation1991) also contended that stakeholder theory is useful for explaining organisational behaviour regarding the control of production and service delivery by demand-side stakeholders interested in services for themselves as consumers, as well as for the benefit of others such as donors. This concept is reflected in credit unions and financial cooperatives because members co-own and co-produce services while realising both economic and social advantages.

Many MFIs provide social services, such as management training and coaching (Boye et al. Citation2011), and achieving a positive social impact is essentially their main mission. However, there has been debate regarding the different religiosities of MFIs, such as whether conventional and Islamic MFIs perform differently, an issue investigated by Rahman (Citation2010), who asserted that Islamic finance plays an important role in promoting socioeconomic development, especially of the poor and small businesses, without charging interest. According to Rahman (Citation2010), Islamic finance offers a wide variety of ethical schemes and instruments suitable for microfinance, such as qardhul hasan (interest-free financing), murabahah (cost-plus financing), and ijarah (leasing) schemes, which are relatively easy to manage and provide capital, equipment, and leased equipment. Within the same framework, Rulindo and Pramanik (Citation2013) surveyed 400 Muslim microentrepreneurs, the majority of whom received Islamic microfinance, and found that spiritual and religious enhancement programmes can, in the short run, increase the positive impact of Islamic microfinance. Moreover, they demonstrated that Islamic microfinance can have a significant impact on recipients’ income and poverty status, although the impact on poverty alleviation is less significant if the poverty benchmark is based on international poverty standards.

Hassanain (Citation2015) stated that microfinance services exceed the concept of microcredit by incorporating charity in finance. Meanwhile, Hoda and Gupta (Citation2015) examined the literature on faith-based organisations and their role in various aspects of development, particularly poverty alleviation. These organisations have the potential to add significant value to the microfinance industry in the form of social capital, community connections, reputation, and cost-efficiency. However, there are few studies on the detailed performance of faith-based MFIs even though the three major religions—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—have doctrines encouraging their adherents to do good for others, e.g., caring for the sick and poor and assisting those in need.

Past research has examined the impact of religiosity on MFIs’ social role; for example, Ahmad (Citation2020) surveyed 543 conventional and 101 Islamic MFIs operating in Islamic and non-Islamic countries to compare their social performance and financial sustainability. The author showed that Islamic MFIs outperform conventional MFIs in terms of outreach and financial performance, while conventional MFIs outperform Islamic MFIs in terms of breadth and depth. Tamanni and Besar (Citation2019), employing a mixed-method approach to analyse 7,200 microfinance data from the Microfinance Exchange Market and the vision and mission statements from the annual reports and websites of 25 MFIs, found that despite the increased adoption of financial or banking performance measures, Islamic microfinance has remained unchanged. The size and age of the institutions, on the other hand, were found to potentially impact the outcomes: smaller MFIs maintain genuine objectives in serving the poor, but as they grow larger, they tend to be more inclined toward sustainability objectives.

An essential social function of MFIs during the pandemic is explored in this article, which compare three distinct MFIs according on their religious background (Islam, Christianity and Hinduism). Due to factors such as high credit risk, insufficient staff, and client illiteracy, commercial banks in rural regions have a hard time delivering financial services; hence, microfinance has evolved as a solution. It is clear from the Grameen Bank experience in Bangladesh that MFIs play an essential and successful role in the fight against poverty in emerging countries. However, no research has yet studied the influence of three distinct faiths on MFIs and their reaction during crises such as COVID-19. Previous studies have demonstrated the good impact of MFIs on poverty reduction. In order to better understand the function of MFIs in society, this research examines the beneficial influence of beliefs and religion.

2.2. Financial sustainability of MFIs

Examining the microfinance sector’s financial capacity to survive on the market, i.e. its financial sustainability, reveals its success and development (Lensink, Citation2018). Financial sustainability was defined by D’espallier (Citation2013) as a firm’s capacity to meet financial goals without external help. In the sustainability literature, most studies estimate the factors influencing the sustainability of MFIs (Tehulu, Citation2013). Emerging research on MFIs’ sustainability in reducing poverty involves lending to women (Kittilaksanawong & Zhao, Citation2018), microfinance plus services (Lensink, Citation2018), governance (Bibi, Citation2018), and capital structure (Bayai & Ikhide, Citation2018), among others.

Macroeconomic stability and financial sector growth are crucial study topics in the literature. Fung (Citation2009) concluded that the economic decisions and the financial performance of a business are intertwined because economic and monetary policies influence financial development. However, few studies specifically integrate macro-level variables with microfinance success to evaluate economic choices and microfinance sustainability, although various economic variables may influence the microfinance sector’s financial stability, as outlined below.

First, Vanroose (Citation2007) analysed the literature offering a substantial correlation between economic success and microfinance performance, revealing that gross national income and population density positively influence MFI performance (Vanroose, Citation2008). Meanwhile, the smaller variance between economic indices and microfinance development was explained by Honohan (Citation2004), while Ahlin et al. (Citation2011) and Imai et al. (Citation2011) empirically examined the macroeconomic indicators and institutional factors that impact financial sustainability. Both studies indicated that economic development has a beneficial effect on the sustainability of MFIs.

According to Nwachukwu (Citation2014), the inflation and interest rates are the primary macroeconomic variables determining the stability of the economy and the growth of the financial sector. Indicators relating to the country are external variables that influence the overall performance of all sectors, including the microfinance industry. Thus, the economic policies of the nation, such as the interest rate, tax policy, inflation rate, and unemployment rate, affect MFI performance (Ahlin et al., Citation2011). For MFIs to be sustainable, their microfinance strategy must consider the country’s scope. Only three studies in the microfinance literature (Ahlin et al., Citation2011; Imai et al., Citation2011; Awaworyi, Citation20119) relate economic aspects with microfinance sustainability, revealing a complex link between economic progress and the financial sustainability of microfinance.

Vanroose (Citation2008) demonstrated that MFIs are successful at decreasing poverty, regardless of the stability of the economy. Ahlin et al. (Citation2011), on the other hand, suggested that there is a substantial causal association between GDP growth and MFIs’ financial sustainability. The research has indicated that inflation and income disparity also impact MFIs: the higher the inflation, the greater the need for loans for fundamental requirements, such as food, security, health, and education. Consequently, financial sustainability declines due to poor financial performance.

The preceding discussion has raised the issue of whether there is a relationship between religiosity and MFIs’ financial success and performance. Hence, this research aims to establish a new model for business sustainability post-Covid-19 and determine how macroeconomic conditions impact MFIs’ financial sustainability.

2.3. Faith-based organisations

Faith-based organisations is an “umbrella word for religious and religion-based organisations, places of religious worship or congregations, specialised religious institutions, and registered and unregistered non-profit organisations with religious character or missions” (Woldehanna, Citation2005, p. 27). These organisations expressly claim a religious motivation (Kirmani & Zaidi, Citation2010), and religion is often represented in their mission statements (Petersen, Citation2010). Fritz (n. d.) lists the following types of institutions: “a religious congregation (church, mosque, synagogue, or temple); an organisation, programme, or project sponsored/hosted by a religious congregation (may be incorporated or not incorporated); a non-profit organisation founded by a religious congregation or religiously-motivated incorporators and board members that clearly states in its name, incorporation, or mission statement that it is a religious organisation.” Several studies have identified the distinguishing qualities of faith-based organisations. Jeavons (Citation1997) proposed seven dimensions, and Sider and Unruh (Citation2004) enumerated them as “organisational self-identity, selection of organisational participants (staff, volunteers, funders, and clients), sources of resources, goals, products, and services (including ‘spiritual technologies’), information processing and decision making (e.g., reliance on prayer and religious precepts for guidance), the development and distribution of organisational power, and the development and dissemination of organisational knowledge” (p. 111).

Smith and Sosin (Citation2001) researched numerous institutions to explore the existence of faith in organisations and concluded that it may be found in the forms of “resource dependence, authority, and organisational culture.” They discovered that the availability of funding, the control of religious institutions or people, and the effect of religion on organisational design are significant elements that shape the distinctiveness of faith-based organisations. Meanwhile, Harrison (Citation2008) defines charitable activities as “generous deeds or gifts to benefit the impoverished, sick, or defenseless” (p. 197), while Dunn’s (Citation2000) definition of charity is “the act of donating money, products, or time to the poor, either personally or by way of a benevolent trust or other deserving cause” (p. 223). According to the US government, charity is simply “anything provided to a person or individuals in need.” (US Congress, Citation1994, p. 53).

From charitable giving to social transformation, Leat (Citation2016) outlined the breadth and diversity of foundations, as well as their geographic dispersal. With many foundations across the globe, a comprehensive assessment thereof would be impossible due to the absence of reliable data. Few nations collect comprehensive statistics on foundations, and the foundations themselves are often content to remain anonymous for a variety of reasons (Hoda & Gupta Citation2016).

A non-profit organisation refers to all organisations that function independently and are not focused on producing a profit for the benefit of a person, board of directors or shareholders (Hoda, Citation2016). Non-profit organisations are categorised as charitable/community organisations and social businesses, with the former being the most common (Castellas, Citation2019). The administration of the two kinds of institutions differs, although they are often established for the same goals. Charitable and community organisations are governed by volunteers who pursue a common goal, while social businesses are administered by shareholders or hired individuals. Non-profit organisations are founded for a variety of reasons (Matic & Al Faisal, Citation2012), although most are formed to address various social problems in the community. The national legal frameworks have an impact on how businesses function, thus restricting their ability to expand globally since they must adhere to local laws and regulations.

In the opinion of Casey (2016), non-profit organisations play an important role in a country’s growth and development because they are often dedicated to improving the standard of living by contributing to the elimination of major social problems, such as poor health, illiteracy, unfavourable climatic circumstances, outdated cultural habits, and poverty. In developing nations, the influence of non-profit organisations is felt acutely because they often rely heavily on foreign assistance.

To differentiate between charitable and non-charitable microfinance services, a new criterion is required that approximates the criterion of normal profit and can be used in practice. The customers, employees, and donors of MFIs delivering services in multiple countries need to know the difference between charitable and non-charitable MFIs. Accordingly, we suggest establishing globally accepted standards for charitableness in microfinance and an internationally recognised microfinance authority. As transparency in microfinance illustrates, the establishment of such an authority may be done via a confederation (like CONCORD in Europe) or through a collaborating organisation that is formally independent of those organisations, like MFI Transparency. Existing microfinance projects, such as CGAP or Mixmarket, may theoretically also provide criterion suggestions.

2.4. Religion-based classification of MFIs

MFIs have proliferated globally (Hoda & Gupta Citation2016), with thousands now on the market. In considering a suitable business model, we explored MFIs by considering whether they are faith-based or have no religious background. We selected MFIs to examine based on the three most common global religions (World Population Review Citation2022), namely Christianity (2.38 billion adherents), Islam (1.91 billion adherents) and Hinduism (1.16 billion adherents).

We review the different business models of some of the MFIs based on their religious backgrounds using information derived from publicly available information on their websites. (Table ) presents the organisations with faith-based business models, although we were only able to obtain detailed data on ACF using interviewing and in-depth data analysis. Using the information on their websites, we describe the models of these organisations, specifically Opportunity International Australia (OIA; Christian background), Spandana Sphoorty Financial Ltd (SSFL; Hindu background), and Assadaaqat Community Finance (ACF; Islamic background).

Table 1. Illustrates the business models and religious backgrounds of 10 MFIs

2.5. Christian MFI

3. Opportunity International Australia (OIA)

Every aspect of a family’s existence is affected by poverty, which causes hunger and poor sanitation, a lack of access to education, and an increased risk of preventable disease, reducing the family’s productivity. People experiencing poverty may obtain modest loans and other financial services via microfinance, helping them to start or expand their enterprises. OIA provides such loans to impoverished people in India and Indonesia, for example, to start a vegetable farm or acquire sewing machines for a tailoring company, allowing the borrower to earn a regular income.

The families repay their loans as their companies grow, enabling OIA’s partners to use the money to help other families in need of financing. In many cases, small company owners hire others, creating employment and boosting the local economy. Microfinance thus enables families to improve their lives, their children’s prospects, and their communities, creating a scalable, long-term solution to poverty. In addition, OIA provides a wide variety of financial services and products through its partners, including savings accounts, micro-insurance and micro-pensions.

Overall, the Opportunity International Network, to which OIA belongs, has helped ten million households living in poverty throughout the world since 1970, through services such as small company loans and agricultural loans in partnership with visionary backers and microfinance institutions (programme partners). Families in need benefit directly from the efforts of these programme partners, who provide loans and other forms of assistance. Support members in Australia, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States provide funds towards the work of programme partners, who receive these monies in the form of stock, loans, or grants. Each programme and support partner is a separate legal organisation, despite their strong ties. No programme or support partner operates as an agent for anything else, and no programme or support partner has the power to legally bind anybody else.

To assist recipients in building their enterprises and making the most of their modest loans, training is often offered as part of loan discussions. Individuals and communities can benefit from additional educational programmes that concentrate on other aspects of daily living. Such financial education teaches individuals how to earn, spend, budget, and borrow money effectively. Financial literacy is an important part of raising responsible consumers, and OIA seeks to make it easier for families to learn about the many options accessible to them, such as via multimedia materials. Digital inclusion through smartphones also helps families conveniently access financial and information services. There are also several types of training, including fundamental themes like marketing and more specialised skills such as manufacturing soap or embroidering. For example, Indonesian participants were shown how to manufacture handicrafts from banana stems. Such life training empowers families in areas such as self-esteem, communication, health and leadership.

The COVID-19 outbreak and related mitigating efforts severely hampered the Indian microfinance sector (R.W. Scott, Citation2005), and OIA’s operations were no exception. The Indian government (Impacted Report, Citation2020) imposed a lockdown on 23 March 2020, restricting the company’s operations to essential services and forcing many small firms to close in the first half of 2020. Income plunged owing to mobility constraints, supply chain problems, and a complete stoppage of all transportation services. The harsh lockdown slowed India’s economy by 23% in the second quarter of 2020. Some of OIA’s partners had to lay off employees. Dia Vikas Capital, Opportunity’s Indian affiliate, worked diligently with the finance minister, the Prime Minister’s Office, and MFI lenders to achieve repayment moratoriums for over 90% of lenders from March to June. Despite high case numbers, India progressively began to reopen its economy beyond Containment Zones in June 2020, and OIA’s programme partners eventually resumed operations, with payback rates ranging from 34% to 90%, which was due to the fact that rural economies were less affected by COVID-19 than urban ones.

The Reserve Bank of India first mandated a three-month moratorium for debtors, eventually extending until 31 August 2020. However, few financial institutions financing MFIs extended the same moratoriums, causing liquidity issues when operations ceased, and borrowers’ repayments stagnated. Only two of OIA’s programme partners have defaulted on loan repayments, while other partners offered customers INR10,000–20,000 (A$187–374) top-up loans to help their small enterprises recover.

3.1. Hindu MFI

4. Spandana Sphoorty Financial Ltd (SSFL)

Spandana Sphoorty Financial Limited (SSFL) is a public limited company registered as an NBFC-MFI with the Reserve Bank of India. Established in 1998, the firm became the largest MFI in India and the sixth largest MFI worldwide by 2003. At its peak, SSFL had 1,856 branches with a presence in 10 states and over 13,500 employees. It offers four services, as detailed below. To uphold its primary concept of transparency, all terms and conditions of the loans are disclosed to the clientele, there are no hidden fees under the guise of value-added services, and all statutory criteria are met.

The first offering is JLG loans, which are unique loans tailored specifically for low-income families who want to improve their financial standing. This main purpose is to enable women to establish and grow income-generating businesses, stabilise family cash flows, and purchase productive assets. A hassle-free monthly payback option means that consumers can save from their daily cash flows without experiencing repayment anxiety. The loan amount is up to $80,000 for 1 to 2 years. This product has an interest rate of 20.97%, along with a 1% upfront processing charge exclusive of GST.

The second service is loan against property (LAP). In order to expand and reach new heights, customers may at times need immediate cash for meeting personal needs or expanding their company, and their home or property might be their largest financial asset. Designed for non-BP L (Below Poverty Line) consumers in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu, this one-of-a-kind loan has an easy monthly payback structure. The purpose is to help customers with company development, working cash needs, or asset acquisition. The maximum loan amount is two billion rupees, with terms ranging from 1 to 8 years. This product’s interest rate ranges from 18 to 26%, plus a processing charge of up to 2% exclusive of GST.

Thirdly, they provide personal loans, which are granted only for firm development, satisfying working cash needs, and expanding the business, such as the acquisition of animals for dairy farming, inventory/materials for commercial purposes, completion of a house/renovation currently under construction, and the repayment of costly debts. By granting this credit, women can increase their present income-generating activities, improving the family cash flow and allowing them to purchase productive assets. Uncomplicated monthly payments make it simple for the clients to repay the loan without difficulty, and the loan amount is up to $2,000,000, and the term is 1 to 3 years. This product’s interest rate ranges from 24 to 26%, plus a processing charge of up to 2% exclusive of GST.

Fourthly, they provide interim loans to help borrowers who are having trouble meeting their short-term liquidity needs. Existing borrowers who have not defaulted in the past can obtain these loans to support their working capital requirements, company development, children’s school expenses, healthcare, or any other emergency needs. Individuals are given this loan with a collective guarantee, and the interim loan programme is of considerable assistance to borrowers under difficult circumstances The maximum loan amount is $20,000, and the loan term is between 1 and 2 years. The frequency of payments is monthly, and this product has an interest rate of 20.97% along with a 1% upfront processing charge exclusive of GST.

SSFL during Covid-19 and the change of management disturbed FY22. Lockdowns have been declared throughout several states as a result of Covid-19 wave 2. As limitations were relaxed across states, the rate of distribution returned to pre-Covid levels. No clients received a moratorium during the restructuring (as permissible per the Covid 2.0 guidelines). SSFL saw the stress much earlier since microfinance clients require time to regularise their revenue cycles. Their entire provisions, which number 648 crores, are adequate to handle any risk that could develop in the historical portfolio.

Presentation for investors on the Company’s audited financial statements for the three months and the year ending 31 March 2022. At the conclusion of Q4, the Management Transition was successfully completed. Concentrate on consolidation and satisfying current consumer demand.

4.1. Islamic MFI

5. Assadaqaat Community Finance (ACF)

In view of the massive global challenges of poverty alleviation, social and economic inequalities, and economic empowerment, the value proposition of the instrument of the Islamic faith-based organisation Assadaqaat Community Finance (ACF), as well as its effectivity, social impact and sustainability, are enhanced by combining government support with ACF’s unique model. The term Assadaqaat refers to a voluntary contribution made by competent Muslims for the benefit of fellow Muslims in need (Salih, Citation1999). ACF has been operational in the UK for 5 years and offers financial services to clients irrespective of their religious background.

Economic opportunity and economic success are linked in ACF’s financial services for community development. The value proposition is straightforward: “Philanthropy creates philanthropists” (ACF, Citationn.d.) according to Islamic principles of benevolence (Assadaqaat) and the common good (Maruf). This model’s trademark is providing quantifiable social and economic benefits while also offering financial support. Financial and social marginalisation, inequality, and poverty may all be addressed via ACF’s non-banking financial services. Thus, individuals, families, and organisations are nurtured and empowered to generate economic prospects for robust and inclusive growth via the provision of “interest-free” financing, professional help, and strategically targeted equity investments.

The literature review showed that Islamic MFIs represent one of the most sustainable models for MFIs because interest rates are prohibited in Islam: “Allah destroys interest and gives increase for charities”, as evidenced by Al-Quran 2:276. Interest-free Islamic MFIs instead rely on zakat, waqf, and sadaqah to bolster the supply side. However, long-term sustainability remains an issue due to reliance on donor organisations and the adoption of somewhat modified Islamic principles modelled on widespread institutional norms. To prevent the moral hazard or adverse selection issue (Mersland & Strøm, Citation2012; El-Zoghbi & Tarazi, Citation2013), most Islamic MFIs do not include other types of Islamic financing, like mudaraba or qard e hasana. Thus, sustainability issues emerge due to the charitable and interest-free nature of the loans.

Unlike others, ACF bases on a business model in which borrowers receive training to help them develop a workable business strategy. To continue the cycle the beneficiaries are encouraged to return the charity (sadaqat) and assist others by becoming benefactors once they have achieved success. This can provide public value comprising both social and economic value: The social value derives from the alleviation of poverty/unemployment and the economic value stems from the creation of successful entrepreneurs. This is in line with the divine guidelines from the Holy Quran as well as the ethical perspective (Kaleem & Ahmed, Citation2010): “Allah hath blighted usury and made almsgiving fruitful. Allah loveth not the impious and guilty” (Ch 2:276). This justifies interest-free finance and encourages Sadaqat. The risk of moral hazard and adverse selection can also be referred to from the divine guidelines and a religious/ethical perspective. Allah says in the Quran: “And be true to every promise, for verily you will be called to account for every promise which you have made.” (Ch17:34).

On the Day of judgment, Allah will ask us about every promise that we made to another and whether we kept that promise. Thus, the guiding principles of Islamic finance are not limited to interest-free loans but also manifest in terms of the mission and the products and services offered due to the different political, religious, economic, and regulatory contexts in which they operate to promote social justice. These principles include the prohibition of interest, the avoidance of excessive uncertainty and gambling, the importance of mutually agreed upon contracts, and the encouragement of risk sharing, mutual assistance, and asset- or equity-backed loans rather than debt-backed transactions without risk-sharing. Islamic MFIs play a role in supplying funds derived from Zakat (mandatory almsgiving and one of the “five pillars” of Islam), Waqf (movable property established by an individual owner to be used in perpetuity for charitable or religious purposes, often mosques, orphanages, or religious schools) and Sadaqat (voluntary charity given without expectation of reciprocity or recognition).

During covid 19 the struggles that individuals and communities confront. Many people lose their employment due to the pandemic, and finding a new work is unlikely. ACF is here to show community that there is a path forward; one that gives confidence and puts back in charge of community future. ACF Supports community by setting up their own company is difficult, but ACF promises during and post covid to secure their financial future, inspire people to work for them, and provide a means for them to support others in the future.

ACF is one of the few organisations that operate based on the Sadaqat principle, offering a revolutionary business model for when traditional microfinance does not live up to expectations.

5.1. A unique MFI business model for sustainability and performance improvement

Emerging economies have long recognised the vital role of MFIs, but their success is nation-, culture-, and context-specific, whereby each setting is different and unique. One of the first research attempts to measure the sustainability of non-profit organisations using the balanced scorecard (BSC) framework was conducted by Sinha and Ghosh (Citation2021), who focused on gathering observations and insights on MFIs’ management and organisational sustainability in a developing market. Sinha and Ghosh (Citation2021) gathered primary data by interacting with the senior management of different Indian MFIs, using thematic analysis to determine the many variables affecting the sustainability of MFIs. Most research on MFI sustainability similarly examines financial results, yet a holistic and company-centric approach, using stakeholder theory, provides added value as it considers a multitude of stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, and customers, all of whom are essential for the survival of MFIs. For both practitioners and firms, the BSC framework focuses attention on the many issues contributing to progress, facilitating performance assessment and the evaluation of the effect of making choices on such progress (Ahmad Citation2020).

Many issues relevant to the financial sustainability of MFIs have been identified by scholars (e.g., Conning, Citation1999; Woller & Schreiner, Citation2002; Cull et al., Citation2007; Mersland & StrØm, Citation2008). Characteristics of MFIs include the number of active borrowers, i.e. the breadth of outreach (Woller & Schreiner, Citation2002; Hishigsuren, Citation2004; Hartarska, Citation2005; Mersland & StrØm, Citation2008, Citation2009); the average loan size, i.e. the depth of outreach (Woller & Schreiner, Citation2002; Adongo & Stork, 2006; Cull et al., Citation2007); the interest rates on loans (Conning, Citation1999; Gregoire & Tuya, Citation2006; Gonzalez, Citation2007; Mersland & StrØm, Citation2008); the capital structure (Kyereboah-Coleman, Citation2007); and the efficiency in employee cost reduction (Navajas et al., Citation2000; Woller, Citation2002; Hartarska, Citation2005). A company’s financial sustainability is affected by increases in operating revenue and decreases in operating expenditures. A few studies concentrated on the financial sustainability component. This paper examines other dimensions of sustainability (MFIs’ geographical location, growth stages, ownership, age, and MFIs product delivery methodology, mission sustainability, programme sustainability, and human resource sustainability) with a focus on ACF, whose financial model is built on financial support for communities and proven social and economic outcomes.

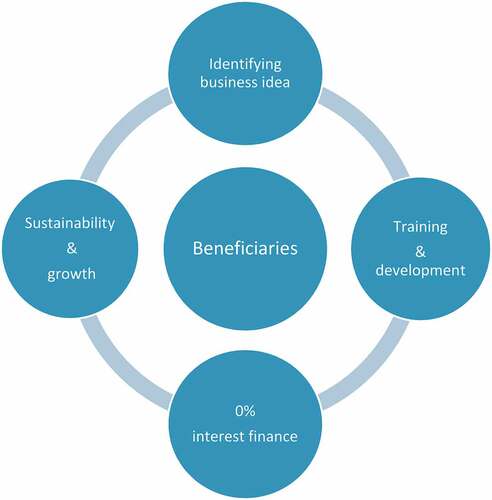

When it comes to addressing the issues of social and economic injustice, financial exclusion, poverty, and the empowerment of women, ACF is at the forefront of social innovation and transformation in the field. ACF recognises that each person’s path to economic success and empowerment is unique, and that individuals need solutions that are specifically designed to meet their needs. ACF’s collaborative and community-focused programmes aim to better understand the challenges that young, female entrepreneurs face and provide them with the assistance, resources, and resources they need, as indicated in Figure .

5.2. The ACF cycle

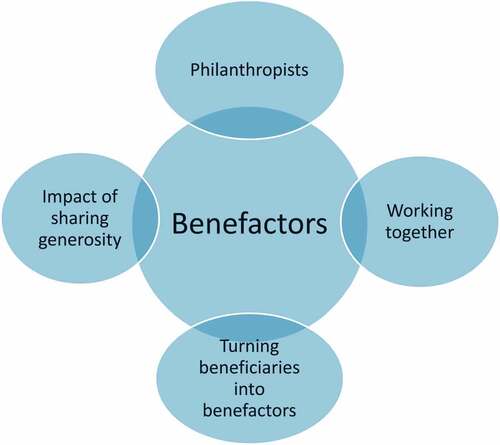

ACF is distinguished by a sustainable cycle that benefits people in need. Donations go a long way in a community of people who feel empowered to sustain themselves, generate employment, and effect good change. To influence communities, ACF depends on compassion and generosity. The ACF cycle works with philanthropists, with donors giving to ACF in order to help others achieve. Individuals and communities benefit by becoming able to realise their entrepreneurial aspirations. Then, ACF and its beneficiaries work together to launch new businesses by using their talents for the benefit of the community as a whole. By creating benefactors out of people who have already received help, the financial resources will expand in tandem with the success of these companies. Finally, by exploiting the benefits of generous exchange, ACF uses a more effective strategy for eradicating poverty. It reduces economic and social inequity while also meeting long-term global development objectives, as illustrated in Figure . Our study explores this unique business model of an Islamic MFIS in a developed country.

5.3. Sample and research methodology

The case study method provides an in-depth assessment of ACF by exploring its unique business models and how this non-profit organisation is able to ensure financial sustainability. The originality of our work manifests in the description of a unique business model of an MFI and an examination of whether its religiosity impacts its activity and performance. The study participants were beneficiaries, benefactors, and founders of ACF, whereby 20 adults (+18 years, male and female) were interviewed on the Zoom platform. Informants were selected using a criteria sampling technique. We received permission from each participant to record the interview sessions. All ethical standards and procedures were adhered to, including protecting participant anonymity and confidentiality and informing the participants of any potential hazards (Surmiak, Citation2018). The use of the case study can be justified as the organisation is a unique model of an Islamic MFI, i.e. based on the Islamic notion of Assadaqaat, and thus can serve as a role model for other MFIs. This research uses a qualitative method to describe the unique business model for MFIs, namely that of ACF, via semi-structured interviews with clients, donors, and the founder of ACF. On average interviews lasted from 45 minutes to one hour and these were transcribed. The transcribed data was analysed using NVivo software version 12. This was supported by frequent discussion and interaction among researchers that led to an interpretation of data .

5.4. Participants

This research utilised a convenience sample incorporating 7 female beneficiaries (most of them educated, 3 married, 3 single and 1 divorced single mum), 8 benefactors (6 male and 2 females, highly educated from affluent backgrounds) and 5 founders of ACF (2 male and 2 females, professionals and highly educated). This paper mainly concentrates on the women entrepreneurship program hence women participants were approached and selected. Participants were recruited with the support of ACF using their criteria selecting beneficiaries. This included general criteria such as age (18 and above), UK residents with the right to work in the UK, or applying for the right to do so, and employed full-time, part-time or unemployed. The average finance amount received by the beneficiaries from ACF ranges from £750 to £2,000. This amount donated (as Assadaqaat) by individual members of the communities, high net worth individual, philanthropist, trusts and foundation are used to provide interest free finance for the Micro and small enterprises set up by the beneficiaries.

5.5. Findings and analysis

As this is a case study the findings are not been generalised in this instance, however we can apply this to other countries and can compare in further studies. This study explores an MFI in the UK by discussing how the financial support can help the recipients to become financially independent or empowered . First, we examined how they are motivated to pay back the loans and how this encourages the beneficiaries to become benefactors and drive the ACF cycle indicated in Figure . Based on their daily, weekly, or monthly income, the re-payment process is done within a set amount of time. The money they borrow must be put into their business to make money, and the same income can be used to pay back the loan. This study evidence suggests that the clients are happy with the process and become independent within 3–6 months, at which point they can contribute back to the institution as benefactors.

MFIs help women improve their skills by giving them training in addition to other kinds of help. Their knowledge is put to use in the process of making money. Running a business teaches them more about life and gives them a better understanding of how to support their families. Knowing how they spend their money gives them a good social standing. This demonstrates how the lives of women can change significantly every day. After paying for everything, their income goes up every month, meaning that they can deposit more money. The confidence level of women in society highlights the success of the whole process.

We use a concept map to describe our results. Unlike other forms of data analysis in qualitative research, concept maps can increase the quality of the obtained data by requiring participants to abandon rehearsed scripts and stories. Qualitative researchers also examine the experiences, influences, and actions of the research participants while openly examining their own personal and epistemological reflexivity in order to recognise their own biases (Willig, Citation2001). Given the vast number of research choices made during research design and analysis (Palys & Lowman Citation2002), the recognition of the possibility of researcher bias is important in social science research. New ways of data gathering may provide additional tools to investigate reflexive analysis in qualitative research. In this paper, we use concept maps as they allow us to see the participants’ meanings as well as the connections that participants discuss between concepts or bodies of knowledge.

5.6. ACF women empowerment programme and financial sustainability

illustrates the effectiveness of the ACF Women Empowerment Programme and how it has had a significant impact on the women’s community in terms of both financial and non-financial support (moral support).

Entrepreneurship is, if you see, the history of Islam such as Khadija (Prophet Mohammad peace upon him) … … .If she who is our mother, who is our example, if she was one of the best entrepreneurs of her sort of region of her time, why can’t we of empower our women. (Founder 1)

Unfortunately, we’ve had situations where just in the world in general, women sometimes don’t feel maybe as confident, they don’t feel that they can be able to get the same support as men in the world of business, which is obviously something that ACF distance categorically against And we’re trying to sort of come in to provide not just financial support, but to provide that sort of mental framework of people trying to get into business and just tell them that this is the mindset that you need to have and it’s okay, t’s a world of trade, your gender should not matter, that sort of thing. (Client 1)

Religion and MFIs are strongly associated and have a significant impact on society (Hoda, Citation2016). During the interviews, it emerged that cultural factors influence the perception of empowerment. Most MFIs’ providers see women’s empowerment as encompassing an increase in financial engagement, mobility, and household decision-making. However, although MFIs advertise microfinance programmes as successful and entirely contributing to women’s empowerment, Nyarko (Citation2022) discovered that males control and use most microfinance loans in rural Bangladesh due to patriarchal gender norms. Additionally, Shohel et al. (Citation2022) revealed that MFIs do nothing to monitor or solve this problem; rather, they emphasise strong loan recovery rates as proof of women’s empowerment. In addition, MFIs use the structural vulnerability of women, as seen by the gendered division of labour, mobility constraints, and conceptions of honour and shame, to assure high recovery rates. Memon (Citation2022) argued that MFIs obfuscate their ulterior profit-seeking goals with deceptive narratives of women’s empowerment.

And also the women in the previous years have been very behind. The women being just looking after kids, raising them and left alone without being like an independent, doing really such amazing job to just support these women who’s behind and they want someone to motivate them. And I’m glad this programme came. (Client 2)

The impact of donations on MFIs has been widely explored. Rahman (Citation2010) mentioned that interest-free Islamic financing plays a crucial role in fostering the socioeconomic growth of the underprivileged and small companies. According to this research, Islamic finance provides a broad range of ethical schemes and microfinance-appropriate tools.

There are many socioeconomic classes who are very deprived, especially if you look at it relative to us that includes obviously the being communities, a lot of women, single mothers, etc. […] and what microfinance can do is, like I mentioned before, it provides that sort of long term solution because it provides the sort of financial base for entrepreneurship, the sort of guidance and the financial base and the confidence for entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurship fosters and creates the base of the society.(Client 3)

The role of microfinance in the socioeconomic environment is pivotal sorry. To lifting women, especially out of maybe poverty and maybe lifting them out of deprivation, maybe lifting them in their status as well and building their self-esteem. (Donor 1)

Sinha and Ghosh (Citation2021) assessed the sustainability of non-profit organisations using the BSC methodology, focusing on accumulating observations and ideas on the management of MFIs and their organisational viability in emerging markets. ACF’s financial model is founded on financial assistance for communities and producing social and economic achievements.

The Woman Entrepreneurship Programme has been very well received. We’ve been doing it everywhere, and it’s on an international level as well. People are showing interest, and in particularly the online versions is what we’ve been focusing on Zoom. And we’re getting a lot of interest. And generally what we found is that the women tend to be quite engaged, more than males in a lot of these kind of things. So it is very sort of motivational for us as well. (Founder 2)

ACF’s strategy is distinguished by offering verifiable social and economic benefits and financial assistance to the communities it serves. Its non-banking financial services further allow financial and social exclusion, inequality, and poverty to be addressed.

Individuals, families, and organisations will be encouraged and enabled to produce economic opportunities for strong and inclusive growth via “interest-free” funding, professional assistance, and strategically targeted equity investments. (Founder 3)

I think personally it gave me a lot of confidence and big boost. So I know where I stand right now. I know I can do it because of Assadaqaat giving me that reassurance and help guiding me through that cause I know sort of exactly what I need to do, but at the right time. (Client 4)

ACF’s unique business model is a paradigm-shifting business concept when conventional microfinance has not met expectations and there is a need to make microfinance more successful. ACF recognises that each individual’s road to economic success and self-determination is unique, and that people need solutions tailored to their personal requirements. The aim of ACF’s collaborative and community-focused programmes is to better comprehend the obstacles faced by young female entrepreneurs and to assist them in realising their ambitions. ACF provides these individuals with the support, tools, and inspiration they need to find a solution that works for them.

In essence, philanthropy begets philanthropists. In order to qualify for financing from ACF, a beneficiary does not need to be a Muslim, but ACF’s philanthropic beliefs are at the core of its operations. Uniquely, ACF gives interest- and debt-free finance to UK businesses that it sources via contributions and collaborations. Its long-term answer to sustainability is based on an innovative community financing concept wherein individuals can not only realise their entrepreneurial goals, but can also become future financiers, assisting the next generation of company owners—the so-called ACF Cycle. As a result, community is at the heart of this form of financing. The features of the ACF finance model also include financial support for the communities and quantifiable social and economic consequences as communities need the necessary business skills to succeed. Mentorship and training programmes are therefore offered by ACF’s skilled staff to guarantee that its entrepreneurs are empowered, knowledgeable, and confident in business. Women and young people are a particular focus of ACF’s efforts to promote entrepreneurship and new ideas.

5.7. Religiosity: gender & cultural influence

Religion has a cultural influence, with a strong relationship between religion, gender and culture that also significantly impacts economic growth. The literature on the social construction of gender roles via religious beliefs has concentrated mostly on two major themes: the relative religiosity of men and women and the leadership responsibilities of men and women within congregations (Tranby, Citation2012).

While not all researchers define themselves as operating within a particular methodology, symbolic boundaries theory highlights the different ways in which (mainly) women and men use religious traditions as concepts, symbols, and metaphors for constructing gender roles and norms and navigating a gendered world. Researchers have focused on the manners in which women exert their control over a congregation as a result of the growing number of women in religious leadership positions (Chaves Citation1996). According to Wallace (Citation1993), female clergy adopt a more collaborative leadership style, are more involved with larger concerns of social justice, and are more liberal on social issues than male clergy. Women also face more challenges to their authority from congregational members. Female clergy often react to these difficulties by advocating gender equality and feminism as more inclusive alternatives to conventional patriarchal systems and by emphasising biblical passages that emphasise equality (Gross Citation1996; Wallace Citation1993).

So see, it’s religiously backed and it’s founded by Islamic principles of being able to support women and trying to progress careers and make them financially independent. (Founder 4)

ACF recognises that everyone’s path to economic empowerment and success is unique and that they need individualised solutions to overcome particular obstacles. ACF provides the necessary assistance, resources, and motivation for people to discover a solution that works for them. Through strategic collaborative partnerships with leading academics, experts, institutions, and organisations, ACF seeks to develop a deeper understanding of the financial needs and experiences of those experiencing economic hardships at the grassroots level and to provide them with custom-tailored solutions, as indicated in .

I think in society generally it’s kind of forgotten and culture gets mixed in that women should stay at home but then it’s given that empowerment back. (Donor 2)

Nonetheless, MFIs are not immune to the fact that an organisation’s success or failure is directly tied to the company’s ethical business practices. For example, ACF’s principles are based on the Islamic value proposition, whereby due to religious beliefs alcohol is prohibited, meaning that there are limitations in choosing business ideas. For example, a business involving alcohol will be rejected and ACF will not support it financially, although it will it support non financially, i.e. via a training programme.

ACF business model of community finance? I think it’s restricted because you have to do what they want and not what you want to do. I see. So, it’s a bit restricted for non-Muslims. (Client 5)

ACF provides a safe platform for contributions of any size, regardless of whether the donor is a person, philanthropist, public/private/corporate entity, trust, or foundation. These contributions help ACF to empower people without harming their self-esteem, aiming to convert today’s beneficiaries into tomorrow’s benefactors.

The ACF Entrepreneurship Programme educates, trains, and mentors potential entrepreneurs while providing interest-free financing to facilitate the creation of micro, small, and medium-sized businesses. The ACF Women Empowerment Program empowers young women to realise their potential and implement their entrepreneurial ideas. ACF focuses on empowering young people from underprivileged areas financially. Through collaborative and community-focused ACF programmes, the organisation seeks to comprehend the concerns and obstacles confronting our communities. ACF’s creative approach to community development is unique.

In the world is to transform the benefices of today to benefactors of tomorrow. So, by helping the people who are beneficiaries today we are asking them to support by repaying the capital back that can reuse for other beneficiaries. So when they are paying it is like basically Assadaqaat. It is a huge global transformation programme. (founder 5)

ACF is at the vanguard of social innovation and transformation that is redefining how we confront social and economic injustice, financial exclusion, poverty, and the empowerment of women. To do this, ACF relies on the generosity of its donors.

So, donating money is part of the pillars of Islam, so it’s one of the main pillars which is a part of what I believe and what I follow. So, yes, I do prefer donating money for religious purposes, but I also donate for humanitarian reasons. (Donor 3)

What five-pound mean to me and what five pounds meant to them. (Donor 4)

6. Conclusions

Funding micro-businesses involves a high level of risk. To gain more understanding of this, we explored in-depth the possible motivations of MFIs for funding women’s micro-businesses in conservative societies. The unique institutional business model of ACF could be adopted by existing Islamic MFIs or other small/medium enterprises around the world. In terms of sustainability, the core Islamic financial principles emphasise social justice, inclusion, and sharing of resources between the “haves” and the “have nots”. The two distinct features of “risk and reward sharing” and “the redistribution of wealth” significantly differentiate this approach to development from the conventional financial industry.

However, it should be noted that one size does not fit all. ACF depends heavily on the donation principle, i.e. if the donations stop for any reason, ACF cannot continue to operate. ACF follows a cycle, and it can only operate if it has numerous successful customers who can, in turn, become benefactors. When applying this business model in different contexts and countries, stakeholders should consider different factors such as age, education level, behaviour, cultural differences, religious beliefs, etc., as these can lead to a change in focus and suggestions. ACF also needs to expand its financial support to the fields of education, health, childhood disabilities (maintenance, health and well-being), and moral support, such as through enhanced well-being. Participants’ focus can be strengthened by running a face-to-face training programme, although Covid-19 has had a huge impact on online learning. ACF must further consider the language barriers, cultural differences, and different ethnicities and religious backgrounds when assigning customers to courses. The key part of this process is turning the beneficiaries into benefactors by motivating them during the training programme and asking them to make promises based on an ayah from the Quran (“And be true to every promise, for verily you will be called to account for every promise which you have made” (Ch17:34); a guideline to transform people—the risk of moral hazard/adverse selection). Finally, ACF should also cultivate strong relationships with global organisations that apply CSR to obtain financial support (benefactors) in order to keep donors on board.

According to the findings of this research, MFIs such as ACF should first reduce their reliance on donated money to become first operationally competent in the market and then financially viable. This should be done with care, however, due to the effect that departing from donations has on viability, as the majority of MFIs rely on contributed equity or subsidised income, particularly in their early years. Second, they should expand the number of borrowers (extent of their outreach) to boost the volume of their sales (loans). However, selling a large number of loans may not be sufficient to ensure financial sustainability, and thus should be complemented by effective follow-ups to guarantee a greater payback rate and to aim for substantially reduced operational expenses per borrower.

Similarly, MFIs must grow the average loan size (reach) in order to be self-sustaining. That is, implementing a bigger average loan size will enhance financial sustainability, but it will also raise the probability of payback failures. MFIs should thus use every effort to balance the average loan size, especially as the econometrics result suggests that the profitability, and hence sustainability, of MFIs increases in tandem with the average loan size, indicating less outreach, which is an indication of mission drift. Therefore, MFIs like ACF should ensure that their profitability growth aligns with their goals if they are to continue to fulfil their primary aim. In addition, subsidies and donations are genuine instruments that are intended to promote efficient performance in microfinance organisations. Subsidies seem beneficial at first glance, but their consequences on the performance, efficiency, and self-sustainability of microfinance organisations may be harmful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACF. (n.d.). The unique business model of Assadaqat Community Financing. https://www.assadaqaatcommunityfinance.co.uk/Communityfinance

- Ahlin, C., Lin, J., & Maio, M. (2011). Where does microfinance flourish? Microfinance institution performance in macroeconomic context. Journal of Development Economics, 95(2), 105–22.

- Ahmad, S., Lensink, R., & Mueller, A. (2020). The double bottom line of microfinance: A global comparison between conventional and Islamic microfinance. World Development, 136, 105130.

- AlRajhi Bank , Al. (n.d.) Al Rajhi Bank report of Corporate Social Responsibility). http://www.alrajhibank.com.sa/en/investor-relations/about-us/pages/corporate-social-responsibility.aspx. Accessed on 19 Jan 2022.

- Armendáriz, B., & Morduch, J. (2010). Economics of microfinance (2nd ed.). MIT Press.

- Awaworyi Churchill, S. (2019). The macroeconomy and microfinance outreach: A panel data analysis. Applied Economics, 51(21), 2266–2274.

- Barry, J. J. (2012). Microfinance, the market and political development in the internet age. Third World Quarterly, 33(1), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2012.628107

- Bayai, I., & Ikhide, S. (2018). Financing structure and financial sustainability of selected SADC microfinance institutions (MFIs). Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 89(4), 665–696.

- Bédécarrats, F., Baur, S., & Lapenu, C. (2011). Combining social and financial performance: A paradox? Commisioned Workshop Paper (Global Microcredit Summit), 1–27.

- Ben‐Ner, A., & Van Hoomissen, T. (1991). Nonprofit organizations in the mixed economy. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 62(4), 519–550.

- Benigni, U. (1913). Montes Pietatis. Encyclopedia Press.

- Bibi, U., Balli, H. O., Matthews, C. D., & Tripe, D. W. (2018). Impact of gender and governance on microfinance efficiency. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 53, 307–319.

- Boyé, S., Hajdenberg, J., Poursat, C., Munnich, D., & Pinel, A. (2011). Le guide de la microfinance. Editions Eyrolles.

- Bruene, J. & Bruene, J. (2008). Peer-to-peer lending volumes worldwide. Retrieved 20 May 2013, from Netbanker.com: http://www.netbanker.com/

- Bussau, D., & Mask, R. (2003). Christian microenterprise development: An introduction. OCMS.

- Castellas, E. I., Stubbs, W., & Ambrosini, V. (2019). Responding to value pluralism in hybrid organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(3), 635–650.

- Chaves, M., & Montgomery, J. D. (1996). Rationality and the framing of religious choices. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 128–144.

- Conning, J. (1999). Outreach, sustainability and leverage in monitored and peer-monitored lending. Journal of Development Economics, 60(1), 51–77.

- Cornforth, D., Green, D. G., & Newth, D. (2005). Ordered asynchronous processes in multi-agent systems. Physica D. Nonlinear Phenomena, 204(1–2), 70–82.

- Cull, R., Demirgu¨ Ç‐kunt, A., & Morduch, J. (2007). Financial performance and outreach: A global analysis of leading microbanks. The Economic Journal, 117(517), F107–133.

- Cull, R., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Morduch, J. (2008). Microfinance meets the market. NYU Wagner Research Paper No. 2011-05.

- Dean, K., Kendall, J., Mann, R., Pande, R., Suri, T., & Zinman, J. (2016). Research and impacts of digital financial services. NBER Working Paper No. 22633 September 2016.

- D'Espallier, B., Guerin, I., & Mersland, R. (2013). Focus on women in microfinance institutions. The Journal of Development Studies, 49(5), 589–608.

- Dunn, A. (2000). As cold as charity? poverty, equity and the charitable trust. Legal Studies, 20(2), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-121X.2000.tb00141.x

- El-Zoghbi, M., & Tarazi, M. (2013). Trends in Sharia-compliant financial inclusion. Focus Note, 84, 1–11.

- FINCA. (2014). “Charitable Microfinance Organization – FINCA.” FINCA. Accessed 19 April 2014 at http://www.finca.org/site/pp.asp?c=6fIGIXMFJnJ0H&b=6088193#.U1JX3X3LfK4

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach (pp. 1–4). Pitman Publishing.

- Fung, M. K. (2009). Financial development and economic growth: Convergence or divergence?. Journal of International Money and Finance, 28(1), 56–67.

- (Gartner report, 2008) et al. (). Social banking platforms threaten traditional banks for control of financial relationships. Available at :. www.gartner.com/it/page.jsp?id=597907

- Gonzalez, A. (2007). Efficiency drivers of microfinance institutions (MFIs): The case of operating costs. Microbanking bulletin, (15).

- (Grameen bank report, 2013), (2013). Grameen Bank. Available at: Retrieved May 2013 from http://www.grameen-info.org/

- Gregoire, J. R., & Tuya, O. R. (2006). Cost efficiency of microfinance institutions in Peru: A stochastic frontier approach. Latin American Business Review, 7(2), 41–70.

- Gross, K. L. (1996). Toward gender equality and understanding: Recognizing that same-sex sexual harassment is sex discrimination. Brook. L. Rev, 62, 1165.

- Gulf Business. Biggest banks in Saudi Arabia [Online]. Retrieved 19 Jan 2022 from http://Sambaonline.samba.com/apps/consumer/ops/EBServlets.svl

- Haar, G. T., & Ellis, S. (2006). The role of religion in development: Towards a new relationship between the European Union and Africa. European Journal of Development Research, 18(3), 351–367.

- Harper, M., Rao, D. S. K., & Sahu, A. K. (2008). Development, Divinity and Dharma: The role of religion in development and microfinance institutions. Practical Action Pub.

- Harrison, L. A. (2008). The central liberal truth. Oxford University Press.

- Hartarska, V. (2005). Governance and performance of microfinance institutions in Central and Eastern Europe and the newly independent states. World Development, 33(10), 1627–1643.

- Hartarska, V., & Mersland, R. (2012). Which governance mechanisms promote efficiency in reaching poor clients? Evidence from rated microfinance institutions. European financial management, 18(2), 218–239.

- Hassanain, K. M. (2015). Integrating Zakah, Awqaf and IMF for poverty alleviation: Three models of Islamıc micro finance. Journal of Economic and Social Thought, 2(3), 193–211.

- Hishigsuren, G. (2004). Scaling up and mission drift: can microfinance institutions maintain a poverty alleviation mission while scaling up? (Doctoral dissertation, Southern New Hampshire University).

- Hoda, N., & Gupta, S. L. (2015). Faith-based organizations and microfinance: A literature review. Asian Social Science, 11(9), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n9p245

- Hoda, N., & Gupta, S. (2016). Loan loss reserves as a test of solidarity in cooperatives. International Conclave on Innovative Engineering and Management.

- Honohan, P. (2004). Financial development, growth and poverty: how close are the links?. In Financial development and economic growth (pp. 1–37). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hudon, M., & Sandberg, J. (2013). The ethical crisis in microfinance: Issues, findings, and implications. Business Ethics Quarterly, 23(4), 561–589. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201323440

- Imai, K., Gaiha, R., Thapa, G., Annim, S. K., & Gupta, A. (2011). Performance of microfinance institutions: A macroeconomic and institutional perspective. School of Social Sciences, University of Manchester.

- The impact of COVID-19 and the policy response in India Report. (2020). https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/07/13/the-impact-of-covid-19-and-the-policy-response-in-india/

- Jeavons, T. H. (1997). Identifying characteristics of “religious” organizations: An exploratory proposal. In J. Demerath III, P. D. Hall, T. Schmitt, & R. H. Williams (Eds.), Sacred companies: Organizational aspects of religion and religious aspects of organizations (pp. 79–95). Oxford University Press.

- Jones, T. M. (1995). Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 404–437.

- Kaleem, A., & Ahmed, S. (2010). The Quran and poverty alleviation: A theoretical model for charity-based Islamic microfinance institutions (MFIs). Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(3), 409–428.

- Kirmani, Nida, & Zaidi, Sarah (2010). The role of faith in the charity and development sector in Karachi and Sindh, Pakistan. Birmingham. Religions and Development Working Paper 50.

- Kittilaksanawong, W., & Zhao, H. (2018). Does lending to women lower sustainability of microfinance institutions? Moderating role of national cultures. Gender in Management: An International Journal.

- Kiva partners (2013), (). Available at :. Retrieved 10 April 2013 from http://www.kiva.org/partners/info

- Kyereboah‐coleman, A. (2007). The impact of capital structure on the performance of microfinance institutions. The Journal of Risk Finance.

- Leat, D. (2016). From charity to change, Brussels to Beijing. In Philanthropic foundations, public good and public policy (pp. 35–52). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lensink, R., Mersland, R., Vu, N. T. H., & Zamore, S. (2018). Do microfinance institutions benefit from integrating financial and nonfinancial services?. Applied Economics, 50(21), 2386–2401.

- Marshall, K., & Keough, L. (2004). Mind, heart and soul in the fight against poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Matic, N. M., Banderi, H. R. H., & AlFaisal, A. R. (2012, July). Empowering the Saudi social development sector. In The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs (pp. 11–18). The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

- McGee, Rosie, & Gaventa, John (2011). Shifting power? Assessing the impact of transparency and accountability initiatives. IDS Working Papers, 1–39.

- Memon, A., Akram, W., & Abbas, G. (2022). Women participation in achieving sustainability of microfinance institutions (MFIs). Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 12(2), 593–611.

- Mersland, R., & Strøm, R. Ø. (2008). Performance and trade‐offs in Microfinance Organisations—Does ownership matter?. Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 20(5), 598–612.

- Mersland, R., & Strøm, Ø. (2010). Microfinance mission drift? World Development, 38(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.05.006

- Mersland, R., & Strøm, R. Ø. (2012). The past and future of innovations in microfinance. The Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurial Finance.

- (Microloan Foundation, 2015). (). Client training evaluation volunteer, Malawi. MicroLoan Foundation: A different approach to charity. Retrieved 28 December 2015 from Available at: http://www.microloanfoundation.org.uk/Files/11_07_Client/20training/20evaluation/20volunteer/20Malawi-person/20spec.pdf

- Middleton, M. (1987). Nonprofit boards of directors: Beyond the governance function. The nonprofit sector: A research handbook. 141–153.

- Murphy, Shannon (2009). Business and philanthropy partnerships for human capital development in the Middle East. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative, Harvard Kennedy School Research Paper, 52.

- Navajas, S., Schreiner, M., Meyer, R. L., Gonzalez-Vega, C., & Rodriguez-Meza, J. (2000). Microcredit and the Poorest of the Poor: Theory and Evidence from Bolivia. World Development, 28(2), 333–346.

- NCB, Ahalina Achievements. (2016). Retrieved on 19 Jan 2022 from http://www.alahli.com.sa/en-us/about-us/csr/Pages/CSR-Awards.aspx

- NCB, K. K. F., & Support, N. C. B. (n.d.). Retrieved on 19 Jan 2022 from http://www.alahli.com/en-us/about-us/news/Pages/Jun2013_News_03.aspx

- Nwachukwu, I. N. (2014). Dynamics of agricultural exports in sub-sahara Africa: An empirical study of rubber and cocoa from Nigeria. International Journal of Food and Agricultural Economics (IJFAEC), 2(1128–2016–92046), 91–104.

- Nyarko, S. A. (2022). Gender discrimination and lending to women: The moderating effect of an international founder. International Business Review, 31(4), 101973.

- Okuda, H., & Aiba, D. (2016). Determinants of operational efficiency and total factor productivity change of major Cambodian financial institutions: A data envelopment analysis during 2006–13. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 52(6), 1455–1471.

- Palys, T., & Lowman, J. (2002). 1. Anticipating Law: Research Methods, Ethics, and the Law of Privilege. Sociological Methodology, 32(1), 1–17.

- Petersen, Marie Juul (2010). International religious NGOs at the United Nations: A study of a group of religious organizations. The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance. http://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/847

- Rahman, A. R. A. (2010). Islamic microfinance: An ethical alternative to poverty alleviation. Humanomics.

- Report, I., 2020. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/07/13/the-impact-of-covid-19-and-the-policy-response-in-india/ ( Available at 31 July).

- Reynolds, S. J., Schultz, F. C., & Hekman, D. R. (2006). Stakeholder theory and managerial decision-making: Constraints and implications of balancing stakeholder interests. Journal of Business Ethics, 64(3), 285–301.