?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study investigates whether effective audit committees, gender-diverse boards, and corruption controls affect the level of voluntary disclosures of Asian banks. Further, we analyze whether directors’ experience moderates the impact of audit committee independence, audit committee meetings, board gender diversity, and corruption controls on voluntary disclosures. We use data for commercial banks operating in six Asian countries, i.e., China, India, Pakistan, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Singapore. For empirical analysis, we apply several robust statistical techniques. We find that commercial banks with effective audit committees, gender-diverse boards, and corruption controls tend to disclose less information voluntarily as they perceive limited benefits from optional disclosures. Further, we find unique evidence that directors’ experience significantly moderates the impact of audit committee independence, audit committee meetings, board gender diversity, and corruption controls on voluntary disclosures of Asian banks. Our unique findings are consistent with the proprietary cost theory. Further, our results indicate that commercial banks operating in countries that maintain rule of law, regulatory quality, and government effectiveness tend to disclose less information voluntarily.

1. Introduction

Several financial scandals and corporate failures have occurred over the last few decades in both developed and developing economies which have been attributed to the lack of financial transparency, inadequate corporate disclosures, and weak corporate governance (Arnold & De Lange, Citation2004; Haniffa & Hudaib, Citation2006; Ntim et al., Citation2012). These financial scandals have renewed the interest of policymakers, practitioners, and academicians to the extent of voluntary disclosures in both developed and developing economies. Voluntary disclosures refer to the disclosure of additional information in the annual report of a firm about issues that would be of particular interest to its stakeholders for decision-making (Zamil et al., Citation2021). Prior studies indicate that voluntary disclosures lead to several benefits for the firm which include lower incidence of underpricing, greater analyst following, enhanced transparency, and greater trust (Rahman et al., Citation2007). Further, firms disclosing information voluntarily benefit from lower information risk premiums, cost of capital, and higher trading volumes and share prices (Rahman et al., Citation2007). In addition, voluntary disclosures reflect management’s credibility and sincerity with the stakeholders which enhances the overall firm reputation in the market. Despite the benefits of voluntary disclosures, existing studies suggest that firms continue to disclose less information voluntarily, perhaps because this information may be used by competitors and rivals for their competitive advantage. Low voluntary disclosure has remained a problem for policymakers, shareholders, and the general public (Cai et al., Citation2017; Masoud et al., Citation2021; Masum et al., Citation2020). While voluntary disclosures benefit all stakeholders, shareholders have the most to gain from the financial transparency arising from voluntary disclosures. As a result, shareholders usually exert pressure on a firm’s management to reduce information asymmetry by enhancing voluntary disclosures.

Given the importance of voluntary disclosures, several studies have focused on the issue but numerous knowledge gaps continue to remain unexplored. First, the majority of the existing literature has used the agency theory but limited attention has been given to other theories such as the proprietary cost theory, signaling, and legitimacy theories (Chi et al., Citation2020; Hazaea et al., Citation2020; Khatib & Nour, Citation2021). Second, few previous studies have considered how executives’ attributes, educational level, experience, and diversity affect the level of voluntary disclosures (Zamil et al., Citation2021). Third, past studies that have used governance-related variables provide inconsistent findings (Zamil et al., Citation2021). For instance, several studies have documented a positive and significant effect of board independence on voluntary disclosures (Yusoff et al., Citation2019), while others found a negative or insignificant relationship between these variables (Nguyen et al., Citation2020). Fourth, while previous studies have investigated the impact of only a few key attributes of the top management on voluntary disclosures, very few studies have analyzed how different aspects of board and senior management affect voluntary disclosures. Fifth, most of the existing literature focuses only on developed countries (Jamil et al., Citation2021; Situ et al., Citation2020); however, the findings of these studies cannot be generalized in the context of emerging economies. Sixth, the existing literature on voluntary disclosures is confined to only a few industries; but does not provide enough evidence for other industries such as banks, airlines, chemicals, and textiles (Zamil et al., Citation2021).

Given the above-mentioned knowledge gaps, this study has two main objectives. First, we investigate whether effective audit committees, gender-diverse boards, and corruption controls affect the level of voluntary disclosures of Asian banks from China, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, India, and Pakistan. Second, we analyze whether directors’ experience moderates the impact of audit committee independence, audit committee meetings, board gender diversity, and corruption controls on voluntary disclosures.

The study contributes to the existing literature in several interesting and unique ways. First, prior studies have not investigated the nexus between audit committee independence, audit committee meetings, board gender diversity, and corruption controls with voluntary disclosures of Asian banks. Second, we provide unique evidence that directors’ experience moderates the impact of audit committee independence, audit committee meetings, board gender diversity, and corruption controls on voluntary disclosures. Third, our unique results support the proprietary cost theory, suggesting that banks determine the level of voluntary disclosures after evaluating the associated costs and benefits. Thus, we argue that banks with effective audit committees and gender-diverse boards would settle for low voluntary disclosures as they perceive limited benefits from these disclosures. Fourth, we report a novel finding that commercial banks operating in countries with superior corruption controls tend to have lesser voluntary disclosures arguably due to fewer agency problems and conflict of interests between contracting parties. Sixth, our further analysis provides unique evidence that banks operating in countries that maintain rule of law, regulatory quality, and government effectiveness tend to have fewer voluntary disclosures.

The remainder of the study is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the literature review containing the theoretical background and hypothesis development. Section 3 discusses the data, measurement of variables, model specifications, and statistical analysis. Subsequently, section 4 reports the empirical results and discussion, followed by further analysis in section 5. Finally, the conclusion is presented in section 6 which mentions the main findings, implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical background

The theoretical foundation of the study is mainly based on two theories, i.e., the agency theory and the proprietary cost theory. Agency theory explains how conflicts of interest affect the behavior of two or more parties in a contract (Fama & Jensen, Citation1983; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). These conflicts of interest result from contracting parties pursuing their private interests at the expense of each other. Further, the theory explains how these conflicts of interest may be mitigated using appropriate governance mechanisms. The previous literature argues that agency costs and conflict of interests between contracting parties can be reduced through effective monitoring and governance mechanisms (Boone et al., Citation2007; Lasfer, Citation2006). It is believed that firms with effective governance systems can utilize the firm’s resources to further shareholders’ interests. Prior studies argue that audit committee effectiveness and strong board attributes play a pivotal role in undermining agency costs associated with agency conflicts (Boone et al., Citation2007). A strong governance framework with audit committee effectiveness and board attributes enhances stakeholders’ confidence in the firm and gives positive signals about the credibility of the management. Therefore, firms with a good governance environment have a lesser need to voluntarily disclose information to stakeholders for the sake of preserving their reputation. Further, firms operating in countries with a high level of corruption may need to voluntarily disclose more information to satisfy investors’ concerns about governance and transparency.

Further, the proprietary cost theory argues that managers weigh the cost and benefits of voluntary disclosures before deciding how much information to disclose (Dye, Citation1985; Healy & Palepu, Citation2001). As a result, managers voluntarily disclose the information if they believe that the proprietary cost of disclosure is lower than its benefits. Prencipe (Citation2004) argues that there are two kinds of proprietary costs associated with voluntary disclosure, i.e., internal and external costs. The costs associated with gathering and disseminating information are referred to as internal costs. Further, the cost associated with competitors misusing the disclosed information to their advantage at the expense of the disclosing firm is referred to as external cost. It is argued that firms with effective monitoring and governance mechanisms maintain good credibility in the market and do not have many benefits to derive from disclosing information voluntarily as compared to the associated internal and external costs (Botosan & Plumlee, Citation2002). Therefore, managers will be reluctant to disclose information voluntarily unless the benefits of disclosure considerably exceed the proprietary cost (Suijs, Citation2005). Similarly, firms operating in countries with high corruption are likely to report information voluntarily as the potential benefits of disclosure would exceed the associated cost.

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. Audit committee independence and voluntary disclosures

Audit committee independence refers to the extent to which the audit committee is independent. Audit committee independence acts as a control mechanism that regulates managerial expropriation and reduces conflict of interests between the contracting parties in an organization (Akhtaruddin & Haron, Citation2010; Allegrini & Greco, Citation2013). Agency theory argues that firms having an independent audit committee tend to have a good governance environment and lower agency problems (Fama & Jensen, Citation1983; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Therefore, these firms enjoy higher investor confidence and a favorable market reputation. Further, the proprietary cost theory suggests that firms will carefully consider the costs and benefits of voluntary disclosure before deciding the extent of voluntary disclosure (Healy & Palepu, Citation2001). It is argued that firms with high audit committee independence tend to have a good governance environment, favorable market reputation, and higher investor confidence. As a result, these firms may not need to disclose information voluntarily as they are unlikely to derive substantial benefits from additional voluntary disclosures. Further, managers of reputable firms are sometimes reluctant to disclose excess information as it may be used by competitors and rivals for their competitive advantage. Several previous studies analyzing the association between audit committee independence and voluntary disclosures have reported mixed findings (Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, Citation2010). Some prior studies have documented a positive relationship between audit committee independence and voluntary disclosures (Akhtaruddin & Haron, Citation2010; Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, Citation2010). These studies argue that an independent audit committee may effectively monitor the management and reduce information asymmetry. Contrarily, several studies did not find a significant association between audit committee independence and voluntary disclosures (Abdullah et al., Citation2017; Allegrini & Greco, Citation2013). Thus, we propose the hypothesis:

H1: Audit committee independence has a significant influence on voluntary disclosures.

2.2.2. Audit committee meetings and voluntary disclosures

Audit committee meetings refer to the frequency of meetings held by the audit committee of a firm. The agency theory argues that the greater the frequency of audit committee meetings, the better the governance environment and monitoring of a firm (Karamanou & Vafeas, Citation2005). Talpur et al. (Citation2018) contended that the frequency of audit committee meetings provides a good measure of audit committee participation and efficacy. Li et al. (Citation2012) suggest that audit committees that meet frequently can better supervise financial reporting and disclosures, resulting in superior financial transparency. Therefore, we argue that investor confidence in the firm’s financial reporting practices increases when audit committees are more effective and vigilant.

Further, the proprietary cost theory suggests that the level of voluntary disclosures is dependent upon the associated costs and benefits. Firms with effective monitoring and governance mechanisms are less inclined to devote substantial resources for making additional information disclosures. The literature provides mixed evidence on the association between audit committee meetings and voluntary disclosures (Othman et al., Citation2014; Talpur et al., Citation2018). Some studies have found a positive effect of audit committee meetings on voluntary disclosures (Abdullah et al., Citation2017; Kent & Stewart, Citation2008; Talpur et al., Citation2018). They argue that a greater number of audit committee meetings enhances corporate monitoring and reduces information asymmetry and conflicts of interest between contracting parties. Contrarily, several studies did not find a significant association between audit committee meetings and voluntary disclosures (Menon & Williams, Citation1994; Othman et al., Citation2014). The insignificant association between audit committee meetings and voluntary disclosures supports the view that frequent meetings do not guarantee monitoring diligence and financial reporting transparency. Thus, we propose the hypothesis:

H2: Audit committee meetings have a significant influence on voluntary disclosures.

2.2.3. Board gender diversity and voluntary disclosures

A gender-diverse board includes the representation of both male and female directors. Gender-diverse boards comprising female directors are considerably more efficient and capable than non-diverse boards (Gul et al., Citation2008). In addition, female directors enhance the accountability of management and transparency of financial reporting practices (Adams & Ferreira, Citation2009). Further, gender diversity enhances the boards’ decision-making capabilities by limiting the stereotypical thinking approach of male directors (Chen et al., Citation2017). Board gender diversity also helps in reducing groupthink in board decisions (Chen et al., Citation2017; Gul et al., Citation2008). The agency theory implies that gender-diverse boards can provide better monitoring and strategic governance as they align the interests of contracting parties (Fama, Citation1980). Thus, we argue that firms comprising gender-diverse boards will have lower agency costs, which will inspire greater investor confidence and financial reporting transparency.

Further, the proprietary cost theory implies that firms comprising gender-diverse boards will be less motivated to report voluntary information as they enjoy a strong market reputation and investor trust (Healy & Palepu, Citation2001). However, the existing literature on the association between board gender diversity and voluntary disclosures remains inconclusive (Srinidhi et al., Citation2011; Sun et al., Citation2012). Several prior studies document a positive impact of board gender diversity on voluntary disclosures (Liao et al., Citation2015; Sartawi et al., Citation2014), perhaps because gender-diverse boards exhibit superior leadership qualities and facilitate democratic decision-making (Eagly & Johnson, Citation1990). Contrarily, several studies did not find a significant association between board gender diversity and voluntary disclosures (Sun et al., Citation2012). Thus, we propose the hypothesis:

H3: Board gender diversity has a significant influence on voluntary disclosures.

2.2.4. Corruption controls and voluntary disclosures

Corruption is a common problem in both developed and developing countries. However, the issue of corruption is particularly serious and prevalent in developing countries due to weak institutional and judicial systems (Jain, Citation2001; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1993). Corruption is considered a significant issue that undermines the economic and social development of a country. Several studies document the adverse consequences of corruption on firm performance and growth (Gaviria, Citation2002). Corruption may seriously affect firm performance due to several reasons such as inefficient resource allocation, lack of innovation, adverse market reputation, and a negative organizational culture (Hung, Citation2008). Contrarily, some studies have argued that corruption may benefit a firm in several ways, such as by reducing bottlenecks in bureaucratic systems, facilitating timely decisions that enable firms to achieve goals, and avoiding strict regulations that deter market activities (Lui, Citation1996). In addition, corruption may allow firms to develop informal networks and associations with influential figures that may facilitate new business opportunities and improve firm performance (De Jong & Van Ees, Citation2014). Finally, the agency theory implies that firms operating in highly corrupt countries are likely to have a serious conflict of interests and agency costs between contracting parties.

Consequently, the high agency cost increases stakeholder skepticism and distrust in management decisions and financial transparency. Further, the proprietary cost theory implies that firms operating in a corrupt environment will gain immensely from voluntary disclosures. These disclosures will help them develop stakeholders’ trust and reduce information asymmetry. Prior studies have mainly focused on the effect of corruption on several aspects of a firm (Gaviria, Citation2002; Hung, Citation2008; Lui, Citation1996). However, the existing literature on the association between corruption controls and voluntary disclosures is very limited. Thus, we propose the hypothesis:

H4: Corruption controls have a significant influence on voluntary disclosures.

2.2.5. Directors’ experience and voluntary disclosures

Director experience refers to the relevant industry experience of the board members. The board of directors’ relevant industry experience helps them make effective and timely strategic decisions that determine the long-term success of a firm (Westphal & Milton, Citation2000). Boards with experienced directors tend to exhibit effective monitoring and governance, improving firm performance and leading to greater financial transparency (Kroll et al., Citation2008). On the contrary, boards with less experienced directors are likely to make short-sighted decisions that may have adverse consequences on firm performance and reputation in the long run (McDonald et al., Citation2008). The agency theory implies that firms having experienced directors tend to exhibit effective monitoring and governance, which lowers agency costs between the managers and other stakeholders (Fama, Citation1980). Therefore, it is argued that an experienced board sends positive signals to a firm’s stakeholders regarding management intentions to have good governance and financial reporting quality. Likewise, firms with experienced boards are likely to make less voluntary disclosures as these firms possess a favorable market status and reputation, thus lowering the benefits of additional disclosures. This viewpoint is consistent with the proprietary cost theory (Kamardin et al., Citation2015). Despite the importance of directors’ experience, there is a lack of empirical evidence on the association between directors’ experience and voluntary disclosures. Further, prior studies have not analyzed whether director experience influences the relationship between board attributes, audit committee effectiveness, and voluntary disclosures. Thus, we propose the hypotheses:

H5: Directors’ experience has a significant influence on voluntary disclosures.

H6: Directors’ experience moderates the impact of audit committee independence on voluntary disclosures.

H7: Directors’ experience moderates the impact of audit committee meetings on voluntary disclosures.

H8: Directors’ experience moderates the impact of board gender diversity on voluntary disclosures.

H9: Directors’ experience moderates the impact of corruption controls on voluntary disclosures.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

The study uses data for listed commercial banks operating in six Asian countries, i.e., China, India, Pakistan, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Singapore, for the period 2016 to 2020. The sample used in the study was selected in three steps. First, we extracted a list of listed commercial banks from the stock exchange website of the sample countries. Second, we retrieved the market capitalization of these banks and sorted them from largest to smallest using market capitalization. Third, we selected ten banks from each country which included a mix of large, medium, and small banks. Thus, our final sample comprises large-cap, medium-cap, and small-cap banks from the six Asian economies. The sample data was extracted from the annual reports of the commercial banks which were available on their websites. There are two reasons for including commercial banks from these six Asian economies. First, the commercial banks from these major economies provide a good representation of the banking industry in Asia. For example, China, Singapore, and Hong Kong are considered leading Asian economies, while India and Malaysia are considered healthy and well-performing economies. In addition, Pakistan was included as it is a relatively new emerging economy in South East Asia. Second, these economies have a more stable and regulated financial system as compared to other Asian economies.

3.2. Measurement of variables

The study investigates how voluntary disclosures are affected by audit committee attributes, board gender diversity, and corruption controls. The measurement of variables and their operational definitions are discussed below.

3.2.1. Voluntary disclosures

Voluntary disclosures (VD) were measured through the index developed by Akhtaruddin and Haron (Citation2010). The index consists of 64 items from 9 dimensions. To calculate the index for each commercial bank, we proceeded as follows. First, we carefully inspected the financial records of each bank to check whether the voluntary disclosure index items were disclosed. Second, if the item was disclosed, we assigned the particular disclosure a value of 1, and 0 otherwise. Third, we calculated the voluntary disclosures score for each bank by dividing its aggregate score by 64. The voluntary disclosures score for each bank was used as the dependent variable in this study.

3.2.2. Independent and moderating variables

The study has used two board attributes, i.e., board gender diversity and directors’ experience. Board gender diversity (BGD) was measured as a dummy variable, taking a value of 1 if female directors are present on the board, and 0 otherwise (Brahma et al., Citation2021). In addition, directors’ experience (DEXP) was measured as the proportion of directors on the board with relevant industry experience to the total number of directors (Meyerinck et al., Citation2016). Further, we have used two audit committee attributes, i.e., audit committee meetings, and audit committee independence. Audit committee meetings (ACMEET) were measured as the total number of meetings held by the audit committee of a commercial bank (Sultana et al., Citation2015).

Moreover, audit committee independence (ACIND) was measured as the proportion of independent audit committee members to total audit committee members (Akhtaruddin & Haron, Citation2010). In addition, we also included corruption controls as an independent variable, measured through the control of corruption indicator (CC). The control of corruption indicator is one of the six world governance indicators published by the World Bank which measures the extent of corruption in each country.

3.2.3. Control variables

The study used leverage (LEV), bank size (BSIZE), and bank age (BAGE) as control variables, consistent with the previous literature. Leverage was measured as the proportion of total liabilities to total assets of a commercial bank (Akhtaruddin & Haron, Citation2010). Further, bank size was measured as the natural logarithm of total assets (Hoang, Citation2015; Khan et al., Citation2012). In addition, bank age was measured as the total number of years since the bank’s inception (Kieschnick & Moussawi, Citation2018).

3.2.4. Model specifications

This section discusses the model specifications used for empirically examining the hypotheses developed previously. Models 1–5 were estimated to test H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5, respectively. The first hypothesis would be supported if the coefficient of ACIND is statistically significant in model 1. Similarly, the second hypothesis would be accepted if the coefficient of ACMEET is statistically significant in model 2. Likewise, the third, fourth, and fifth hypotheses would be supported if the coefficients of BGD, CC, and DEXP are statistically significant in Models 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

Further, models 6–9 were estimated for empirically testing H6, H7, H8, and H9, respectively. Following Dawson (Citation2014), if the coefficients of the interaction terms, i.e. ACIND*DEXP, ACMEET*DEXP, BGD*DEXP, and CC*DEXP are statistically significant, there is evidence of a moderating effect and it would support H6, H7, H8, and H9, respectively.

3.2.5. Statistical analysis

This study has used the feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) panel regression technique to investigate the association between audit committee effectiveness, board attributes, corruption controls and voluntary disclosures. The FGLS panel regression was applied as the data suffered from heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation and created the need for estimating robust standard errors (Greene, Citation2018). Further, we used the robust panel regression to revalidate our earlier statistical results. The robust panel regression also provides reliable estimations in the presence of heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation (Greene, Citation2018).

4. Discussion of results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Table reports the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study. The mean value of VD is 43.58% (with a standard deviation of 9.80%). The mean value indicates that the average VD of the sample Asian banks is 43.58%. The mean value of VD for our sample is slightly lower than 47.3% for Pakistani non-financial firms (Sheikh et al., Citation2019) and 58.62% for Malaysian non-financial firms (Akhtaruddin & Haron, Citation2010). Further, the mean value of ACIND is 53.35% (with a standard deviation of 23.77%). It implies that the average bank in our sample has nearly 53.35% independent members in the audit committee. This result is lower than 69.29% and 65.5%, which is the mean value of audit committee independence reported for Malaysian and Chinese non-financial firms, respectively (Akhtaruddin & Haron, Citation2010; Alkebsee, et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

In addition, we find that the mean value of ACMEET is 5.707 (with a standard deviation of 2.95). It suggests that the average number of audit committee meetings per year are 5.707. Moreover, the mean value of BGD is 72.88% (with a standard deviation of 44.53%). It implies that nearly 73% of the sample banks have a gender-diverse board. The average value of DEXP is 47.56% (with a standard deviation of 14.47%), which implies that nearly 48% of directors on the board have relevant industry experience. Our result is slightly lower than the 54.39% reported by Meyerinck et al. (Citation2016) for S&P 500 companies. Further, the mean value of CC is 63.80 (with a standard deviation of 25.81), which suggests that the average CC for the sample countries is 63.80. Finally, LEV, BSIZE, and BAGE mean values are 1.51, 6.55, and 61.73, respectively.

4.2. Pearson correlations

The Pearson correlations of the variables are reported in Table . The results suggest that VD has a negative and statistically significant correlation with ACIND (r = −0.4438), ACMEET (r = −0.2236), BGD (r = −0.2337), DEXP (r = −0.3995), CC (r = −0.2511) and BAGE (r = −0.1101). These results suggest that banks with independent audit committees and frequent audit committee meetings tend to have lower VD. Further, banks having gender-diverse boards and directors’ experience are associated with lower VD. In addition, banks operating in countries with corruption controls tend to disclose less information voluntarily. Lastly, we find that older firms are likely to disclose less information voluntarily.

Table 2. Pairwise Correlations

Moreover, the results indicate that ACIND is positively and significantly correlated with ACMEET (r = 0.2331), DEXP (r = 0.2092), CC (r = 0.1542) and BSIZE (r = 0.1283). It implies that large banks operating in countries with better corruption controls, frequent audit committee meetings, and experienced directors are likely to have independent audit committees. Similarly, ACMEET is positively and significantly correlated with BGD (r = 0.2028) and BSIZE (r = 0.1470). It suggests that audit committees of large banks with gender-diverse boards tend to meet frequently. In addition, BGD has a positive and statistically significant correlation with DEXP (r = 0.2815) and BAGE (r = 0.2453) but a negative correlation with BSIZE (r = −0.1665). Our results indicate that boards having directors’ experience are associated with higher gender diversity. Similarly, DEXP is positively and significantly associated with CC (r = 0.3280) and BAGE (r = 0.1767) but negatively correlated with LEV (r = −0.1696). This finding implies that banks operating in countries with better corruption controls tend to have experienced directors on the board. Further, it indicates that banks with directors’ experience usually have less leverage. Lastly, CC is positively associated with BAGE (r = 0.2185), while LEV is negatively associated with BSIZE (r = −0.5336).

4.3. FGLS Panel regression results

The FGLS panel regression results are presented in Table . As per the recommendation of Greene (Citation2018), the FGLS panel regression is preferred to address statistical problems such as heteroskedasticity and auto-correlation. We estimate our models after performing several diagnostic tests such as the Breusch-Pagan LM test, Chow test, heteroscedasticity, and autocorrelation test. The Wald-Chi squared statistic of all the models reported in Table indicates that all the models are statistically significant and have sufficient explanatory power.

Table 3. FGLS panel regression results

The regression results reported in Table suggest that ACIND has a negative and statistically significant relationship with VD in model 1 (β = −0.1702, p < 0.01) and model 6 (β = −0.2605, p < 0.01), ceteris paribus. Further, ACMEET has a negative and statistically significant relationship with VD in model 2 (β = −0.0070, p < 0.01) and model 7 (β = −0.0204, p < 0.01), ceteris paribus. These results imply that banks with independent audit committees and frequent audit committee meetings tend to disclose less information voluntarily. These findings are consistent with the agency and proprietary cost theories but inconsistent with the majority of existing literature focusing on non-financial firms (Abdullah et al., Citation2017; Akhtaruddin & Haron, Citation2010; Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, Citation2010; Talpur et al., Citation2018). The agency theory argues that effective audit committees provide confidence and reassurance to stakeholders about management’s credibility. Further, the proprietary cost theory suggests that firms determine the extent of voluntary disclosures after evaluating the associated costs and benefits. Thus, we argue that banks with effective audit committees would settle for low voluntary disclosures as they perceive limited benefits from additional disclosures. Thus, we find support for H1 and H2.

Table also indicates that BGD has a negative and statistically significant relationship with VD in model 3 (β = −0.0211, p < 0.01) and model 8 (β = −0.0960, p < 0.01), ceteris paribus. Further, DEXP has a negative and statistically significant relationship with VD in model 4 (β = −0.2807, p < 0.01), model 6 (β = −0.2860, p < 0.01), model 7 (β = −0.4252, p < 0.01), model 8 (β = −0.4264, p < 0.01) and model 9 (β = −0.7570, p < 0.01), ceteris paribus. Our results are supported by both the agency and proprietary cost theories but are not consistent with the majority of existing literature focusing on non-financial firms (Liao et al., Citation2015; Sartawi et al., Citation2014). The agency theory argues that firms that employ proactive governance mechanisms can mitigate agency conflicts and inspire the trust and confidence of stakeholders. Thus, we argue that banks having gender-diverse boards and experienced directors have a lesser need for voluntary disclosures as they already enjoy the confidence and trust of stakeholders. The proprietary cost theory supports our viewpoint as the net benefits of voluntary disclosures are considerably low for well-governed firms. Hence, we find support for H3 and H5.

Furthermore, the results reported in Table indicate that CC has a negative and statistically significant relationship with VD in model 5 (β = −0.0006, p < 0.01) and model 9 (β = −0.0044, p < 0.01), ceteris paribus. Our results corroborate the viewpoint of both the agency and proprietary cost theories. This finding implies that banks operating in countries with better corruption controls tend to have fewer agency problems and conflicts of interest between contracting parties, consistent with the agency theory. Thus, we argue that banks operating in countries that control corruption effectively are likely to disclose less information voluntarily due to their limited net benefits. To the best of our knowledge, previous studies have not examined the association between corruption controls and voluntary disclosures in the context of financial firms. Thus, our study provides a novel contribution to the existing literature on voluntary disclosures, which also supports H4.

Moreover, the results presented in Table suggest that DEXP positively and significantly moderates the association between ACIND and VD in model 6 (β = 0.2160, p < 0.01), ACMEET and VD in model 7 (β = 0.0250, p < 0.01), BGD and VD in model 8 (β = 0.1760, p < 0.01) and CC and VD in model 9 (β = 0.0086, p < 0.01). These results are interesting and unique. To the best of our knowledge, previous studies on voluntary disclosures have not documented the moderating effects of directors’ experience. These novel findings can be justified in several ways. First, commercial banks with strong governance, effective audit committees, and operating in countries with low corruption tend to have low VD. They usually focus on meeting short-term targets and ignore the strategic consequences of low VD. However, when experienced directors interact with gender-diverse boards and effective audit committees, they tend to refocus on strategic factors that have long-term implications. Second, the prior literature suggests that directors with relevant industry experience can provide better monitoring and supervision as they possess in-depth knowledge about market dynamics and industry practices (Custódio & Metzger, Citation2013).

Further, experienced directors can better provide strategic direction to the firm and expert advice to the board (Armstrong et al., Citation2010; Custódio & Metzger, Citation2013). Thus, we argue that when experienced directors interact with gender-diverse boards and effective audit committees, they are more concerned about the strategic depth of a firm’s policies and encourage firms to disclose information voluntarily as it would enhance their long-term credibility. Third, firms with effective audit committees and well-governed boards tend to minimize additional disclosures as they are particularly concerned about VD’s internal and external costs. Thus, we argue that the presence of experienced directors on effective audit committees and diverse boards will encourage them to adopt a strategic focus and appreciate the long-term benefits of VD (Custódio & Metzger, Citation2013). The long-term benefits of VD may include greater investor confidence, stakeholders’ trust, and firm reputation. Consistent with earlier studies, we used LEV, BSIZE, and BAGE as control variables. The results suggest that LEV, BSIZE, and BAGE are statistically significant in some model specifications.

4.4. Robustness analysis

Table presents the robust panel regression results. We re-estimate our models to corroborate our earlier results with another estimation technique. The robust panel regression addresses violations of statistical assumptions such as heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation by adjusting the standard errors of the regression coefficients (Greene, Citation2018). The results in Table corroborate our earlier findings. The results are broadly consistent with the FGLS results in Table which indicate that ACIND, ACMEET, BGD, DEXP, and CC have a negative and statistically significant association with VD. Further, Table also indicates that DEXP moderates the impact of ACIND, ACMEET, BGD and CC on VD. Hence, our key findings are consistent across multiple estimation techniques, strengthening our viewpoint and contribution to the literature.

Table 4. Robust panel regression results

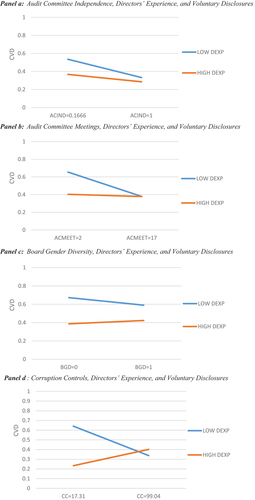

4.5. Moderation plots

The results presented above support our hypotheses that directors’ experience moderates the impact of audit committee independence, audit committee meetings, board gender diversity, and corruption controls on voluntary disclosures. These significant moderating effects are graphically presented through moderation plots as per Dawson (Citation2014). The moderation plots are presented in Figure which corroborate our earlier findings. First, we present the moderating effect of directors’ experience on the association between audit committee independence and voluntary disclosures in panel A. Second, the moderating effect of directors’ experience on the association between audit committee meetings and voluntary disclosures is presented in panel B. Third, panel C presents the moderating effect of directors’ experience on the association between board gender diversity and voluntary disclosures. Fourth, the moderating effect of directors’ experience on the association between corruption controls and voluntary disclosures in panel D. Thus, Figure provides support to H6, H7, H8, and H9.

Figure 1. Moderation Plots.

5. Further analysis

5.1. Effects of rule of law, regulatory quality, government effectiveness on voluntary disclosures

The earlier results suggest that corruption control has a negative and statistically significant association with voluntary disclosures. This finding implies that the characteristics of a country are among the major determinants of the level of voluntary disclosures. This section further analyzes whether selected World Governance Indicators (WGI) such as Rule of Law (ROL), Regulatory Quality (RQ), and Government Effectiveness (GE) affect the level of VD in our sample firms. In addition, it will enable us to strengthen further and extend our novel contributions to the existing literature. The baseline models for analyzing the impact of ROL, RQ, and GE are presented in models 10–12, respectively. The baseline model for DEXP has been presented in model 5 above and is not repeated.

Furthermore, the interaction models 13–15 analyze whether DEXP moderates the impact of ROL, RQ, and GE on VD, respectively.

Table presents the results of the baseline and interaction models. The results suggest that ROL has a negative association with VD in model 10 (β = −0.0008, p < 0.01) and model 13 (β = −0.0048, p < 0.01). Further, we find that GE has a negative association with VD in model 11 (β = −0.0012, p < 0.01) and model 14 (β = −0.0049, p < 0.01). Similarly, RQ has a negative association with VD in model 12 (β = −0.0006, p < 0.01) and model 15 (β = −0.0042, p < 0.01). These findings corroborate our earlier results and the viewpoint of agency and proprietary cost theory. It implies that firms operating in countries with better rule of law, regulatory quality, and government effectiveness are likely to disclose less information voluntarily as they perceive limited benefits associated with additional disclosures. Further, the results indicate that DEXP moderates the association between ROL and VD in model 13 (β = 0.0088, p < 0.01), GE and VD in model 14 (β = 0.0086, p < 0.01), and RQ and VD in model 15 (β = 0.0078, p < 0.01). These results further strengthen and support our earlier argument that experienced directors on the board in firms operating in countries with an adequate ROL, RQ, and GE level will bring strategic depth and focus. It may encourage firms to voluntarily disclose additional information due to their long-term strategic benefits, such as greater investor confidence, stakeholder trust, and firm reputation. Furthermore, we find that LEV, BSIZE, and BAGE are significant in some model specifications and consistent with our earlier results.

Table 5. Effects of Rule of law, regulatory quality, government effectiveness on voluntary disclosures

5.2. Audit committee characteristics, board attributes, and voluntary disclosure levels

As discussed earlier, firms with strong governance and effective audit committees enjoy stakeholders’ confidence and trust. Therefore, these firms have a lesser need to disclose additional information. Further, the proprietary cost theory suggests that firms determine VD levels according to the perceived cost and benefits associated with additional disclosures. Our earlier results indicate that firms with effective audit committees and well-governed boards tend to have low VD as they perceive limited benefits associated with additional disclosures. This section further explores the association of audit committee effectiveness and well-governed boards with firms with low and high VD thresholds. For this purpose, we divide our sample banks into two sub-samples, i.e., banks comprising low and high VD. We classify a bank with high VD if its VD score is greater than 0.5. On the contrary, banks with a VD score of less than 0.5 are classified as having low VD. The following models were estimated to differentiate between the effects of effective audit committees and well-governed boards on VD levels.

The dependent variable LOW_VD in model 16 is a dummy variable taking a value of 1 if a bank has a VD score of less than 0.5 and 0 otherwise. Similarly, the dependent variable HIGH_VD in model 17 is a dummy variable taking a value of 1 if a bank has a VD score of more than 0.5 and 0 otherwise. To estimate the models, we used the logit, probit, and complementary log-log regression techniques.

Table reports the results of logit, probit, and complementary log-log regression. The results indicate that ACIND, BGD, and DEXP have positive and statistically significant coefficients in model 16 which depicts LOW_VD. These results corroborate our earlier findings which suggest that firms with independent audit committees, gender-diverse boards, and experienced directors have a greater likelihood of LOW_VD. Contrarily, the results indicate that ACIND, BGD, and DEXP have negative and statistically significant coefficients in model 17 which depicts HIGH_VD. These findings further strengthen our earlier argument that firms with independent directors in the audit committees, board gender diversity, and experienced directors on the board have a lower likelihood of HIGH_VD. Overall, our results from this section cross-validate our viewpoint that firms with effective audit committees and well-governed boards are likely to disclose less information voluntarily as they perceive limited benefits associated with voluntary disclosures.

Table 6. Influence of effective audit committees and well-governed boards on VD Levels

6. Conclusion

This study investigates whether effective audit committees, gender-diverse boards, and corruption controls affect the level of voluntary disclosures of Asian banks. For empirical analysis, we have used robust estimation techniques. Consistent with the agency and proprietary cost theory, our novel results suggest that commercial banks with effective audit committees and well-governed boards tend to disclose less information voluntarily. Furthermore, we find unique and novel evidence that directors’ experience moderates the impact of audit committee independence, audit committee meetings, board gender diversity, and corruption controls on voluntary disclosures. To further strengthen our contribution to the literature, we document that several WGI indicators affect voluntary disclosures. In addition, we also find that directors’ experience moderates the association between these WGI indicators and voluntary disclosures. Lastly, we cross-validate our main results by dividing the full sample into two sub-samples based on the level of voluntary disclosures. Our sub-sample analysis indicates that firms with independent audit committees, gender-diverse boards, and experienced directors have a greater likelihood of low voluntary disclosures, which corroborates our main findings.

The study has several implications for policymakers, managers, and shareholders. First, policymakers are advised to make policy changes encouraging firms to enhance board gender diversity and experienced directors on the board. Second, the management of banks should promote voluntary disclosures as it provides numerous strategic benefits such as greater investor confidence, stakeholders’ trust, and firm reputation. Third, we suggest that shareholders should also support and encourage senior management in making voluntary disclosures due to their associated long-term benefits. Our study has some limitations, i.e., we have used data from selected Asian countries consisting of only financial firms over a limited time horizon. Future research may consider examining the association between effective audit committees, well-governed boards, corruption controls, and voluntary disclosures using data from non-financial firms in other countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdullah, M., Shukor, Z. A., & Rahmat, M. M. (2017). The influences of risk management committee and audit committee towards voluntary risk management disclosure. Jurnal Pengurusan, 50, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17576/pengurusan-2017-50-08

- Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

- Akhtaruddin, M., & Haron, H. (2010). Board ownership, audit committees’ effectiveness and corporate voluntary disclosures. Asian Review of Accounting, 18(1), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/13217341011046015

- Alkebsee, R. H., Tian, G. L., Usman, M., Siddique, M. A., & Alhebry, A. A. (2021). Gender diversity in audit committees and audit fees: Evidence from China. Managerial Auditing Journal, 36(1), 72–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-06-2019-2326

- Allegrini, M., & Greco, G. (2013). Corporate boards, audit committees and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Italian listed companies. Journal of Management & Governance, 17(1), 187–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-011-9168-3

- Al-Shammari, B., & Al-Sultan, W. (2010). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in Kuwait. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 7(3), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1057/jdg.2010.3

- Armstrong, C. S., Guay, W. R., & Weber, J. P. (2010). The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 179–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.10.001

- Arnold, B., & De Lange, P. (2004). Enron: An examination of agency problems. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(6–7), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2003.08.005

- Boone, A. L., Field, L. C., Karpoff, J. M., & Raheja, C. G. (2007). The determinants of corporate board size and composition: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 85(1), 66–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.05.004

- Botosan, C. A., & Plumlee, M. A. (2002). A re‐examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00037

- Brahma, S., Nwafor, C., & Boateng, A. (2021). Board gender diversity and firm performance: The UK evidence. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(4), 5704–5719. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2089

- Cai, W., Lee, E., Wu, Z., Xu, A. L., & Zeng, C. C. (2017). Do economic incentives of controlling shareholders influence corporate social responsibility disclosure? A natural experiment. The International Journal of Accounting, 52(3), 238–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2017.07.002

- Chen, J., Leung, W. S., & Goergen, M. (2017). The impact of board gender composition on dividend payouts. Journal of Corporate Finance, 43, 86–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.01.001

- Chi, W., Wu, S. J., & Zheng, Z. (2020). Determinants and consequences of voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from private firms. The British Accounting Review, 52(6), 100939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2020.100939

- Custódio, C., & Metzger, D. (2013). How do CEOs matter? The effect of industry expertise on acquisition returns. The Review of Financial Studies, 26(8), 2008–2047. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hht032

- Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

- De Jong, G., & van Ees, H. (2014). Firms and corruption. European Management Review, 11(3–4), 187–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12036

- Dye, R. A. (1985). Disclosure of nonproprietary information. Journal of Accounting Research, 23(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490910

- Eagly, A. H., & Johnson, B. T. (1990). Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 233–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.233

- Fama, E. F. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 88(2), 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1086/260866

- Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law & Economics, 26(2), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/467037

- Gaviria, A. (2002). Assessing the effects of corruption and crime on firm performance: Evidence from latin America. Emerging Markets Review, 3(3), 245–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1566-0141(02)00024-9

- Greene, W. (2018). “Econometric Analysis”. Stern School of Business, New York University.

- Gul, F. A., Srinidhi, B., & Tsui, J. S. (2008). Board diversity and the demand for higher audit effort. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–43. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1359450

- Haniffa, R., & Hudaib, M. (2006). Corporate governance structure and performance of Malaysian listed companies. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33(7‐8), 1034–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2006.00594.x

- Hazaea, S. A., Zhu, J., Al-Matari, E. M., Senan, N. A. M., Khatib, S. F. A., Ullah, S., & Ntim, C. G. (2020). Mapping of internal audit research in China: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1938351. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1938351

- Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31(1–3). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(01)00018-0

- Hoang, T. V. (2015). Impact of working capital management on firm profitability: The case of listed manufacturing firms on ho chi minh stock exchange. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 5(5), 779–789. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.aefr/2015.5.5/102.5.779.789

- Hung, H. (2008). Normalized collective corruption in a transitional economy: Small treasuries in large Chinese enterprises. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9396-2

- Jain, A. K. (2001). Corruption: A review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(1), 71–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00133

- Jamil, A., Mohd Ghazali, N. A., & Puat Nelson, S. (2021). The influence of corporate governance structure on sustainability reporting in Malaysia. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(8), 1251–1278. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-08-2020-0310

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Kamardin, H., Bakar, R. A., & Ishak, R. (2015). Proprietary costs of intellectual capital reporting: Malaysian evidence. Asian Review of Accounting, 23(3), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-04-2014-0050

- Karamanou, I., & Vafeas, N. (2005). The association between corporate boards, audit committees, and management earnings forecasts: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting Research, 43(3), 453–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2005.00177.x

- Kent, P., & Stewart, J. (2008). Corporate governance and disclosures on the transition to international financial reporting standards. Accounting & Finance, 48(4), 649–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.2007.00257.x

- Khan, A., Kaleem, A., & Nazir, M. S. (2012). Impact of financial leverage on agency cost of free cash flow: Evidence from the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 2(7), 6694–6700. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Asma-Khan-34/publication/340299049_Impact_of_Financial_Leverage_on_Agency_cost_of_Free_Cash_Flow_Evidence_from_the_Manufacturing_sector_of_Pakistan/links/5e83254592851c2f526d9a31/Impact-of-Financial-Leverage-on-Agency-cost-of-Free-Cash-Flow-Evidence-from-the-Manufacturing-sector-of-Pakistan.pdf

- Khatib, S. F., & Nour, A. N. I. (2021). The impact of corporate governance on firm performance during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(2), 0943–0952. https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO202104142259637.pdf

- Kieschnick, R., & Moussawi, R. (2018). Firm age, corporate governance, and capital structure choices. Journal of Corporate Finance, 48, 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.12.011

- Kroll, M., Walters, B. A., & Wright, P. (2008). Board vigilance, director experience, and corporate outcomes. Strategic Management Journal, 29(4), 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.649

- Lasfer, M. A. (2006). The interrelationship between managerial ownership and board structure. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33(7‐8), 1006–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2006.00600.x

- Liao, L., Luo, L., & Tang, Q. (2015). Gender diversity, board Independence, environmental committee and greenhouse gas disclosure. The British Accounting Review, 47(4), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2014.01.002

- Li, J., Mangena, M., & Pike, R. (2012). The effect of audit committee characteristics on intellectual capital disclosure. The British Accounting Review, 44(2), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2012.03.003

- Lui, F. T. (1996). Three aspects of corruption. Contemporary Economic Policy, 14(3), 26–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7287.1996.tb00621.x

- Masoud, N., Vij, A., & Ntim, C. G. (2021). Factors influencing corporate social responsibility disclosure (CSRD) by Libyan state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1859850. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1859850

- Masum, M. H., Latiff, A. R. A., & Osman, M. N. H. (2020). Ownership structure and corporate voluntary disclosures in transition economy. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 7(10), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no10.601

- McDonald, M. L., Westphal, J. D., & Graebner, M. E. (2008). What do they know? The effects of outside director acquisition experience on firm acquisition performance. Strategic Management Journal, 29(11), 1155–1177. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.704

- Menon, K., & Williams, J. D. (1994). The use of audit committees for monitoring. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 13(2), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4254(94)90016-7

- Meyerinck, F., Oesch, D., & Schmid, M. (2016). Is director industry experience valuable? Financial Management, 45(1), 207–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12089

- Nguyen, T. M. H., Nguyen, N. T., Nguyen, H. T., NGUYEN, V.-T., & Dao, T.-K. (2020). Factors affecting voluntary information disclosure on annual reports: Listed companies in Ho Chi Minh City stock exchange. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(3), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no12.053

- Ntim, C. G., Opong, K. K., & Danbolt, J. (2012). The relative value relevance of shareholder versus stakeholder corporate governance disclosure policy reforms in South Africa. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 20(1), 84–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2011.00891.x

- Othman, R., Ishak, I. F., Arif, S. M. M., & Aris, N. A. (2014). Influence of audit committee characteristics on voluntary ethics disclosure. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 145, 330–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.06.042

- Prencipe, A. (2004). Proprietary costs and determinants of voluntary segment disclosure: Evidence from Italian listed companies. European Accounting Review, 13(2), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963818042000204742

- Rahman, A. R., Tay, T. M., Ong, B. T., & Cai, S. (2007). Quarterly reporting in a voluntary disclosure environment: Its benefits, drawbacks and determinants. The International Journal of Accounting, 42(4), 416–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2007.09.006

- Sartawi, I. I. M., Hindawi, R. M., Bsoul, R., & Ali, A. J. (2014). Board composition, firm characteristics, and voluntary disclosure: The case of Jordanian firms listed on the Amman stock exchange. International Business Research, 7(6), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v7n6p67

- Sheikh, R. A. G. A., Shah, M. H., & Shah, M. H. (2019). Impact of Audit Committee Characteristics on Voluntary Disclosures: Evidence from Pakistan. Asian Journal of Economics and Empirical Research, 6(2), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.501.2019.62.113.119

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1993). Corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118402

- Situ, H., Tilt, C. A., & Seet, P. S. (2020). The influence of the government on corporate environmental reporting in China: An authoritarian capitalism perspective. Business and Society, 59(8), 1589–1629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650318789694

- Srinidhi, B. I. N., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. (2011). Female directors and earnings quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(5), 1610–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01071.x

- Suijs, J. (2005). Voluntary disclosure of bad news. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 32(7‐8), 1423–1435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0306-686X.2005.00634.x

- Sultana, N., Singh, H., & Van der Zahn, J. L. M. (2015). Audit committee characteristics and audit report lag. International Journal of Auditing, 19(2), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12033

- Sun, Y., Yi, Y., & Lin, B. (2012). Board Independence, internal information environment and voluntary disclosure of auditors’ reports on internal controls. China Journal of Accounting Research, 5(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2012.05.003

- Talpur, S., Lizam, M., & Zabri, S. M. (2018). Do audit committee structure increases influence the level of voluntary corporate governance disclosures? Property Management, 36(5), 544–561. https://doi.org/10.1108/PM-07-2017-0042

- Westphal, J. D., & Milton, L. P. (2000). How experience and network ties affect the influence of demographic minorities on corporate boards. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(2), 366–398. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667075

- Yusoff, H., Ahman, Z., & Darus, F. (2019). The influence of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility disclosure: A focus on accountability. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 23(1), 1–16. https://www.proquest.com/openview/38542bb47561b0dd95376f47309756f0/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29414

- Zamil, I. A., Ramakrishnan, S., Jamal, N. M., Hatif, M. A., & Khatib, S. F. (2021). Drivers of corporate voluntary disclosure: A systematic review. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-04-2021-0110