Abstract

The dominant media ideology argues that the successful application of social media engagement in commercial marketing has the potential to influence customers buying decisions by X percentage. This can equally play a pivotal role in voters` voting decisions. Political marketing research scholars have proposed the need to study the role of social media in the voting decision. However, scholarly responses to this call have received limited attention with interesting debates and opposing arguments. The diverse opinion in the field complicates our understanding, making it difficult to draw a viable conclusion on its relevance and proper application. The authors, therefore, empirically examined the role of social media in the relationship between determinants of voters` behaviour and voting intention in Ghana. This is to help overcome the limited empirical understanding to stir up its relevance and proper application in the political space. The authors collected data from 600 Ghanaian voters, which were analyzed with the help of the Structural Equation Model (SEM) Smart PLS. We found a positive and significant relationship between determinants of voters` behaviour dimensions and voting intention. The study further established that social media engagement plays a vital role in the relationship between the determinants of voters` behaviour and voting intention. We, therefore, recommend that since the information displayed on social media platforms about political parties and their leaders has the potential to influence voters voting decisions, the media actors, political leaders, and political consultants should pay particular attention to media engagement and the kind of information placed in the media about the political leaders.

1. Introduction

Determinants of voters` behaviour (DVB) have received considerable attention over the past half-century among academic scholars and practitioners. Political parties worldwide, particularly emerging economies like Ghana, resort to DVB to overcome the challenges of declining voters` participation and voting intention (Konlan, Citation2017; Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015 & Lees ‐ Marshment, Citation2019, Citation2019). The review of related literature revealed some key issues requiring research attention. Scholars have therefore made several attempts to advance DVB models that can improve voting intention, but their effort and response to this call have yielded inconclusive results (Elinder, Citation2010; Rachmat, Citation2014 & Dabula, Citation2017). While some found positive relationships (eg. Lee et al., Citation2004; Elinder, Citation2010), others found no relationships (eg. Durr, Citation1999; Petterson &Lidband, Citation2008) others (eg.Ahmed et al., Citation2011; Rahmat, Citation2013) found negative relationship, (Veiga & Veiga, Citation2010) also found the relationship to be indirect.

Evidence has shown that most DVB initiatives have failed to predict voting intention (International IDEA, Citation2016), while some scholars have also reported increasing perceptions of over-exploitation (Konlan, Citation2017). Others opine that the déterminants of voters` behaviour are personal beliefs (Newman, Citation2002; Newman & Sheth, Citation1987, Citation1987). Lees ‐ Marshment, Citation2019; Lees ‐ Marshment, Citation2019) argued that the growing mixed findings are worth scholarly attention as they may lead to missed guidance and poor policy implementation. Following a model developed and proposed by Neuman and Seth (Citation1981) and tested by Newman and Sheth (Citation1987); Newman (Citation2002)), more concern has been raised among scholars in the last three decades. A number of these scholars have recognized DVBand voting intention such as; political issues (Lee et al., Citation2004), contingent situations, Srinivasan and Morman (Citation2005), Candidate personality (Neuman & Sheath, Citation1981; Citation1985 & Newman, Citation2002), Social imagery(Neuman & Sheath, Citation1981, Citation1985 &Newman, Citation2002), Epistemic value (Neuman & Sheath, Citation1981, Citation1985 & Newman, Citation2002), Trust and loyalty (Dabula, 2017). These researchers examined some of these variables on voting intention (Gefen, Citation2000; Du Plessis, Citation2010; Hooghe et al., Citation2011; Ahmed et al., Citation2011; Chiru & Ghrghina, Citation2012; Rahmat, Citation2013 & Dabula, Citation2017). However, so far, the above key determinants of voting intention have been extensively stdied, with little attention being paid to voters` behaviour determinants that contribute most to voting intention. Although DVB dimensions influence on voting behaviour has gained significant attention in western developed dimensions democracies (Elinder, Citation2010; Hooghe et al., Citation2011). A piece of successful experience in voting intention in one country could hardly be replicated in another place due to voters` behaviour determinants, geographics, and cultural dependents characteristics (Zhang, Citation2009; Jeng, Citation2011). Therefore, the universal application of findings will be inappropriate. The inability of politicians to identify these differences and emphasize voters` behaviour has been a major drawback in our political landscape (Anebo, Citation2002; Era, Citation2015). In fact, (Vries et al., Citation2011; Newman, Citation2002) argued that there is a significant disparity concerning the best way to determine the best model that can universally predict voters` behaviour and that no single model of voters` behavior is accepted; hence behavioural examination will be the best predictor of voting intention. To contribute meaningfully to the literature, the study assesses how DVB dimensions, such as the candidate’s personality, contingency situation, epistemic value inflation rate, corruption, and foreign policy, can improve voters’ voting intention. Two conditions in the form questions are specified and assessed: (1) Does the DVB influence voting intention? (2) Does social media mediate the relationship between DVB and voting intention?

While it is prudent to examine further the direct impact of DVB on voting intention, scholars (Reimann et al., Citation2010; Rahmat et al., Citation2013) have raised concerns about the “direct and unconditional performance effects” of these variables. Rahmat et al. (Citation2013) posit that the relationship could be redrafted under certain conditions. Responding to calls by scholars (Lee-Marshment, 2006 & Dabula, Citation2017) for future research to examine the mechanisms (why & how & by what means) through which voting behavior determinants translate into a positive voting intention. Scholars alike have examined mediators such as ethnicity (Kim, Citation2014), religion (Kim, Citation2014), media (Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015), and Celebrity endorsement (Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015) from political leaders’ perspectives. From the voters’ perspectives, scholars have mostly examined voters` demographic characteristics (e.g., Mensah, Citation2011 & Citation2016). Over-reliance on demographic characteristics as the best measure of voting intention is criticized in the literature. In long-term relationships, social media engagement has been recommended as a strong predictor of behavioral intentions and the new frontier through which politicians can connect with voters compared to demographic characteristics (Ahmed et al., Citation2011; Dabula, Citation2017; Kumar & Natarajan, Citation2019). Despite gaining much attention in the political marketing literature, the role of social media appears to have received fairly scant empirical attention, despite being described by scholars (Kumar & Natarajan, Citation2019 & Dabula, Citation2017) as the fundamental principle upon which voting intention should be built on and therefore should be the next frontier for the politicians (Langlois & Elmer, Citation2013 & Dabula, Citation2017). Notwithstanding the growing body of research in the area, it is still unclear how the DVB interacts with variables such as social media to predict behavioral intention (Dabula, Citation2017). There is a serious concern that the role of social media voters` trust in voters` behavior determinants literature has only received very few empirical findings to support the claim. This missing link is very crucial.

Voting behavior strategies may not be universal, because voters` voting behavior determinants and voting intention may differ based on their partisan identification, individual political inclination, early childhood socialization, the information they received from the media, and the impression they form from the message (Benoit, Citation2003, Citation2007; Seiler et al., Citation2013; Vasudeva & Singh, Citation2017). It is, therefore, very important that politicians are reminded about the dangers of information placed in the media and its influence on voting behavior, considering the factors of the local condition influencing voting intention (Newman, Citation2002, p. 2007). Poor understanding of how social media influence voting intention has been identified as a key threat facing politicians in Ghana (Benoit, Citation2007), as empirical evidence has shown that social media mediate the nature of relationships between the DVB antecedents and voting intention (Dabula, Citation2017). Therefore, it is logically extended that possible differences may exist in how different voters evaluate DVB and how their perceptions of these determinants influence their voting intention (Benoit, Citation2007; Rahmat, Citation2013 & Dabula, Citation2017). Notwithstanding the empirical evidence available on the mediating role of social media in determining voters` behavior and voting intention, relationships are yet to receive adequate attention in the political marketing literature (Benoit, Citation2007 & Dabula, Citation2017).

This article empirically tested the relationship between the DVB and voting intention in an emerging democracy to contribute to theory and practice. This expands the theoretical boundaries of the discipline of political marketing and provides significant practical benefits and managerial implications for political parties and practitioners in an emerging democracy. This study argued that, under certain conditions, the effect of determinants of voters’ behavior may be redrafted and that some boundary conditions may better explain how determinants of voters’ behavior improve voting intention. This study investigates the direct effect of DVB on voting intention and the possible mediating role of social media. The study enriches the theorization of the effect of determinants of voters’ behavior by explaining some boundary conditions that improve voting intention in an emerging democracy. The general political atmosphere gives credence to the importance of DVB when making decisions that affect the voter and the politicians (Strauss, Citation2009; Newman, Citation2002). There is an increasing role for determinants of voters’ behavior in the overall election process (Elinder, Citation2010).

Neuman (Citation2002) argued that efficient DVB deployment greatly impacts a voting decision. This notion presupposes that implementing DVB enables political parties to enhance voting intention (Bukari et al., Citation2020). Research over the years has dealt with various aspects of the concept of DVB(e.g., Konlan, Citation2017). In the existing literature, however, two important issues appear not to have received sufficient attention. First, in the empirical research, few studies have investigated how DVB can efficiently and effectively influence voting intention. Neuman (Citation2002) posits that assessing DVB is important to improve voting intention’s efficiency and effectiveness. This study accordingly seeks to examine the influence DVB has on voting intention. Although DVB influences voting intention, the varying outcome recorded in empirical findings (e.g., Newman, Citation2002; Neuman & Seth, Citation1981; Pearson et al., Citation2009) is a source of concern regarding its rightful application.

Although studies such as Elinder (Citation2010) and Neuman (Citation2002) have examined the antecedents and outcomes of determinants of voters’ behavior in the political context, there may be boundary conditions that may shape the effect of DVB on voting intention under certain conditions. The possible mediating factors that may optimize the DVB-voting intention relationship have not been adequately explored in the literature. The last objective of this research is to extend this line of inquiry by investigating how DVB may serve as an antecedent to other higher-level constructs. Empirical findings from political marketing literature have suggested that the difference between successes and failures in a political party and voters` relationship is the DVB. DVDs are, therefore, seen as an important critical factor for social media (Benoit, Citation2007; Dabula, Citation2017). In this study, DVBs are seen as second-order determinants whose effect on the intention we propose is best explained through other first-order determinants. According to Benoit et al. (2010), relatively little attention is paid to the specific consequences of second-order determinants, such as DVBs. Social media is a first-order determinant closely related to DVB (Ahmed et al., Citation2011; Benoit, Citation2007 & Dabula, Citation2017). This research examined the mediating role of social media in the relationship between DVB and voting intention. The study applied DVB rationale in political marketing to understand the behavior of Ghanaians toward voting decisions. This is premised on the model developed by Newman and Seth (Citation1981) and tested by Newman and Sheth (Citation1987); Newman (Citation2002), which clearly defined the constituents of a predictive model of voters’ behavior and antecedents of voting intention (Newman, Citation2002). Building the study on the theoretical frameworks of the media dominant theory, this study seeks to understand how political leaders can take advantage of these determinants to get the best from voters through project development, implementation, positioning and repositioning in a manner that leads to an improved voting intention. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews the literature on determinants of voters’ behavior and voting intention. The subsequent section covers the research model and hypotheses development, while the fourth section presents the methodology and analysis. The last section concentrates on discussing the findings and offers both theoretical and pragmatic implications as well as conclusions.

2. Literature review

2.1. Determinants of voters` behaviour

The DVB are key factors for evaluating any incumbent government’s performance and have been recognized as the new frontier of competitive advantage (Neuman & Seth, Citation1981; Newman, Citation2002). Political parties that can implement good DVBcan improve the standard of living of their citizens and benefit from a voting decision, which improves their overall performance in the election (Elinder et al., 2002). DVB is a strategic tool targeted at identifying, developing, and improving the voters` requirements by delivering superior voter value compared to the competition with the primary goal of improving electoral outcomes (Newman, Citation2002). The importance of the DVBis that it facilitates the improvement of voters` requirement in their environment and help enhance their standard of living. As the DVBlevel increase, there is a concomitant increase in the voters` ability to improve their standard of living, which increases satisfaction, trust, and loyalty (Dabulah, 2917). DVBthus allow political parties to create the environment for the voters to perform the two distinct roles of performance evaluation and promoting development (Newman, Citation2002.). The DVBin this study denotes the extent to which political parties can prioritize voters` requirements in their policy formulation and implementation agenda. It, therefore, measures the performance capacity of political parties and their leaders to enjoy the reward of good policy formulation and implementation offers by voters` satisfaction, trust, loyalty, and improved voting intention, which have been recorded in the literature (e.g., Dabulah, Citation2017; Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015).

3. Social media in politics

The dynamic nature of the political environment, in general, has led to the discussion of social media from a different point of view. Morar and Chuchu (Citation2015) and Dabulah (Citation2017) argued that social media influence on politics might come from different sources, and political parties look for information from social media from within their internal customers, from the political market (external environment) and the voters. The current study lends support to the argument of the synthesis approach in which social media in politics is regarded as a new integrative position of the assimilation and demarcation approaches. The assimilation approach emphasizes that social media engagement in commercial business and politics is similar; for that matter, the same measures and indicators should be used (Dabulah, Citation2017). On the other hand, the demarcation approach sees social media engagement in politics as different; therefore, it should require its sets of theories and analytical instruments to study the patterns (Dabulah, Citation2017). This study conceptualizes social media engagement in politics as a process or outcome of undertaking a new dimension in a political party’s activities targeted at generating new insight and processes, enhancing the delivery and communication of significant benefits of programs and activities (product), and improving the competitive nature of the political party in its environment. Social media engagement in the political marketing literature has shown a strong and positive relationship with voting intention (see, Bukari et al., Citation2020; Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015 & Dabulah, Citation2017). In literature, three types of engagement have gained significant attention: attacking, defensive, and acclaiming of policies and positions (Benoit, Citation2007; Benoit & Hartcock, Citation1999). Benoit (Citation2007) described attacking engagement as developing a strategy to attack the political opponent’s policies and programs while presenting one’s own as the alternative option, e.g., Benoit (Citation2007) and Benoit and Hartcock (Citation1999) also posit that attacking social media engagement defines the “extent to which political parties alter their strategic agenda to enhance strategic communication” (p. 8). Defensive, on the other hand, refers to defending and supporting the core activities while stressing the benefits of these policies (Benoit, Citation2007; Benoit & Henson, Citation2007). Acclaiming strategy, however, helps candidates to make themselves appeal to electorates during the election by engaging in acclaiming or self-praise Benoit. This suggests that acclaiming engagement could be incremental or radical (Benoit, Citation2007). Acclaim strategies will increase benefits for the candidates or the political parties. The development of an entirely new strategic position (radical) offers political parties the opportunity to reach new voter segments. Acclaiming social media engagement is a projection of parties’ policies and positions in nature. It allows political parties to strategically position themselves in the target audience’s mind (voters), increase the expectation of value to be delivered to current voters, and sometimes break into offensive strategies. Empirical studies on this engagement in politics have shown a positive relationship between voting intention (see Dabulah, Citation2017; Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015) and overall performance in terms of vote share, election outcome, and loyalty (see Benoit & Brazeal, Citation2002; Benoit & Hartsock, Citation1999).

4. Social media engagement in Ghana politics

The last decade has witnessed a significant trend in social media engagement in Ghana’s politics. The growing interest of the youth, in particular, to express their concerns and grievances on political and economic issues on social media platforms has gained the political actors’ attention, with the major political parties having their own official social media platforms with employees assigned specifically to handle all matters relating to politics and economics situations. They defend their party, attack the opponent and project their party image. The 2016 and 2020 general elections witnessed campaigns and activities on social media. The 2020 general election took it to a different dimension due to the covid-19 movement restriction and a ban on public gatherings. The campaign was now taken to various social media platforms, including journalists and online bloggers. However, it is worth noting that Ghan’s social media penetration is very slow due to the low internet penetration rate. This notwithstanding, information on social media is free and can universally be accessed by all users. The challenge, therefore, is that Ghana’s internet penetration rate is only about 50%, with abo only 8 million social media users. Therefore, this paper seeks to examine how the information in the media can influence a voting decision.

5. Voting intention

Neuman (Citation2002) explains that voting intention measurement is a key political party activity central to the sustenance and prosperity of any political organization. Intention measurement indicates the strength of the political parties and most often helps the political leaders and management realign their strategies to improve the outcome. Voting Intention generally has been examined from a wider variety of contexts. The dominant voting intention measurements in the political marketing literature are mostly political issues, such as unemployment (Elinder, Citation2010; Elinder et al., 2015), the rate of inflation (Incantalupo, Citation2018), and exchange rate factors that influence the future voting decision (Pasek et al., Citation2009; Straus, 2009) are seen as key determinants of voting intention. Neuman and Seth (Citation1987) and Neuman (Citation2002) found a political issue measure (e.g., unemployment) to relate to political leaders’ performance generally, while others have used the rate of inflation and exchange rate to measure how well the economy is performing. Elinder et al. (2015) assert that these measures are better indicators of future voting intention than unemployment measures and are valuable in evaluating and measuring future voting intention. The combined effect of these indicators is important as they all reflect the living standard of the citizens, how well the economy is performing, and the overall leader’s performance. In many empirical studies, either individual or combined determinants have been used to explain better the effect of voters` decisions on their future voting intention (see, Newman, Citation2002). Previous studies have generally adopted objective and subjective measurement approaches in measuring voters’ voting intention. Objective measures are data-based, while subjective measures are usually self-reported. Predicting future voting decisions is extremely difficult in a multiparty democratic environment with intense competition. Bukari et al. (Citation2020) submit that subjective performance measures are appropriate and serve the same purpose as objective measures. Prior studies (e.g., Pasek et al., Citation2009) have also established the reliability of subjective, self-reported measures, while Dabulah (Citation2017) has shown that both direct and indirect measures of voting intention are strongly correlated (e.g., Newman, Citation2002; Bukari et al., Citation2020 & Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015) have used subjective measures.

6. Theoretical underpinning

The theoretical underpinning of this study is the dominant media model. This is a determining factor of voting behavior due to its role in informing citizens and forming their opinions (Wiese, Citation2011). Ball &Peters (Citation2005:180) posits that the role of the mass media, particularly that of television, is increasingly gaining attention in determining election outcomes. Citizens generally depend on the media for information about politicians and their actions and inactions to make an informed voting decision (Ladd, Citation2010; Wiese, Citation2011). The information in the media plays a central role in political elections by adjusting the voters’ political opinions and electoral preferences (Ladd Citation2010). Usually, images and texts placed in the mass media are used to form the public’s perception of their political leaders and their parties. By exposing their audiences to certain texts conveying messages about political leaders, government performances political conduct and doing this regularly, certain images and impressions are unequivocally formed in the audience’s minds, which can lead to informed political opinions and political support in an election (wise, 2011). In the case of voting and elections, the media provide a lot of the information used by the electorate (Strömberg Citation2004:265).

Furthermore, media messages affect voting preferences by providing political information and direct persuasion (Ladd Citation2010). Those who follow the news during a presidential campaign have different perceptions of national economic performance and voting preferences. Moreover, those who consume more news are more likely to change their views of the candidates during a presidential campaign (Ladd Citation2010). One route for partisan change in adolescence is through the information encountered in their social and political contexts (Wolak Citation2009:575).

Furthermore, the media may significantly affect policy without changing public opinion or voting behaviour. The reason for this is that politicians respond at the same time and in a similar way to changes in media coverage, keeping voting contentions constant (Strömberg Citation2004:271). However, according to Strömberg (Citation2004:266), the simultaneous responses of political parties to media coverage may keep voting intentions and public opinions relatively constant while policies change considerably. Media can have a sizeable political and, more specifically, electoral impact (Della; Vigna & Kaplan Citation2007). When voters distrust the media or press, voting based on party identification becomes the most instrumental choice (Ladd Citation2010). Media effects research has focused on media messages’ power to persuade the public. However, it has been increasingly noted that political behavior depends on the volume and content of media messages and attitudes toward the press (Ladd Citation2010).

Changes in the news media’s reputation as an institution can affect political beliefs, opinions, and voting preferences, even while media messages are constant (Ladd Citation2010). This model emphasizes how groups and individuals interpret their position, which depends on how their position has been presented to them via mass media and education, as well as by the government (Heywood Citation2002:244). According to Heywood (Citation2002), the media can also distort the flow of political communications by setting the agenda for debate and structuring or manipulating preferences and sympathies. Thus, the Dominant ideology Model and the Media go hand-in-hand as dominant ideologies are portrayed in the mass media, which leads to political opinions and support being constructed in the minds of the electorates. However, a notable weakness of the model is that the overemphasizing of the process of social conditioning completely disregards individual determination and personal autonomy (Heywood Citation2002:244). Furthermore, it should always be considered that individuals tend to read and listen to texts in the media selectively. Audiences normally select information and remember it, depending on how compatible the information is with their current or existing values and beliefs.

7. Psychological and sociological theory

Interestingly, the central focus of the (Goldberg, Citation1966, p. 914) argument is that determinants of voters’ behavior as a tactical weapon to an organization/political party do not automatically guarantee a sustainable competitive advantage over arch-rival. DVB as, a strategic tool to improve voting intention, will largely depend on how it is allocated and implemented to yield a mutually beneficial voter-politician relationship to establish an among the voter audience and their political leaders. The level of relationship that is established is what will unequivocally lead to the generation of sustainable competitive advantage through an improved voting intention and vote share of the party in question. This study, therefore, argued that human psychology and sociology play a vital role in the relationship between DVB and voting intention.

The psychological theory assumes that individual consumers view the relationship with firms and political organizations as psycho-social group ties to commit their time and resources to a relationship. Thus, a second theory underpinning this thesis is the psychological theory (Catt Citation1996). The psychological theory explains how individuals develop loyalty over time in a given relationship. Individuals in such a relationship develop love and affection for each other through psycho-social group ties. The central assumption here is that long-term patterns of partisanship are developed through a chronological stage of an individual’s entire life. This is the premise that social location as a political, environmental factor is an important determinant of who an individual interacts with, and the environment in which one lives generally affects their life, subsequently influencing their political behavior and support (Catt Citation1996, p. 5).

Elcock (Citation1976, p. 220) posits that partisanship is often inherited, which tends to influence an individual voter to develop preferences for the political party or candidate preferred by family, friends, and other social group members. The principal assumption underlying this model is early socialization (Goldberg, Citation1966, p. 914) which subsequently influences an individual’s information evaluation and processing. This phenomenon, however, leads to the development of partisan orientation by an individual and its associated effects on their stable political involvement (Darmofal & Nardulli, Citation2010). As one grows along the line, they take cues from the position of their social group ties; this includes the development of party identification which plays a vital role in their perceptions of politically related decisions (Wolak, Citation2009). This theory guides political leaders in establishing and developing a long-term relationship with the citizens/ voters over time, and this development plays an unparallel role in their voting decision.

The sociological model assumes that social determinants like individual social characteristics are the most important determinants of voting behavior, but not attitude (Catt, Citation1996). This theory guides the researcher in conceptualizing the mediating role of social media in determining voters` behavior and the voting intention relationship. Thus, group membership influence on individual voting behaviour is a key component of this model (Schoeman & Puttergill, Citation2007). Though this model, like any other theory/model, is not free, it is still considered relevant in the voting behaviour literature (Brooks et al., Citation2006). The principal point is that several voters make a voting decision that resonates with their childhood-oriented political predisposition.

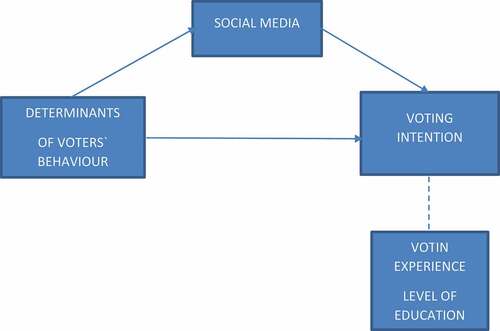

8. Research model and hypotheses development

The main arguments of this study are depicted in a conceptual model in Figure . The study argues that when political parties implement DVB successfully, it will influence voting intention. This is based on the argument that improving the DVB by political parties will influence voting decisions (Neuman & Seth, Citation1981; Citation1987 & Newman, Citation2002). However, determinants of voters’ behavior should be further seen as a strategic tool that enhances political parties` performance to influence the voters voting decisions positively. Successful implementation of DVB enables political parties to exploit voters to their advantage through trust and loyalty-building as well the argument on their social media engagement that can subsequently lead to an improved voting intention. Social media engagement in projecting and strengthening one policy position while attacking the opponent is therefore shown to be an important mediator between DVB and voting intention.

9. Determinants of voters’ behavior and voting intention

How political parties implement sets of specific, identifiable determinants of voters’ behavior routinely into their policies and programs influences their level of performance for a considerable period (Neuman, 2007; 2008). The level of determinants of voters’ behavior implementation explains the difference in political parties’ performance in an election, that is, their vote share (see Neuman, 2008). Political parties that seek to improve their competitiveness and enhance their performance can gain positive voting intention decisions from the voters (Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015). DVB thus allow political parties to purposely extend, create or modify their strategies, policies, and implementations (Newman, Citation2002). In politics, the voter is a key external resource that the political party can purposely extend or modify to enhance election performance (Konlan, Citation2017; Lee-Marshment, 2009). Neuman and Seth (Citation1981) and Neuman (Citation2002) suggest that determinants of voters’ behavior are effective development and strategic weapons when effectively exploited, which will bring about voting intention improvement. Therefore, developing and implementing the right determinants to exploit this strategic development tool becomes important for voting intention enhancement. The ability of the political parties to learn from, utilize and involve the grassroots with their effective implementation of DVB to create value is contingent on the general acceptance of the political party by all (Konlan, Citation2017; Lee-Marshment, 2019). Political parties generally accepted by society, like the ones that implement good policies for their welfare, can, for instance, exploit their determinants of voters’ behavior as a strategic resource through effective and efficient deployment. The acceptance and recognition by the non-party supporters allow the political party to fully harness these determinates as a strategic resource to improve the voters voting intention. The determinants of voters as a strategic weapon are generally available to all political parties. However, a political party that implements it to benefit society is in a better place to take advantage of such efficient and effective resource deployment to enjoy positive voting intention from the voter audience. DVB become personal and specialized assets that enhance the efficiency of policy implementations to put the party in a very competitive position. Since such determinants (determinants of voters` behavior) are idiosyncratic and should be developed, implemented and deployed intentionally and purposefully to achieve competitiveness, political parties that consciously develop them DVB will enhance their vote share and improve voting intention. The study, therefore, assumes that, barring any country-specific factor influence, political parties are likely to benefit immensely from the efficient and effective implementation of determinants of voters` behavior. The study, therefore, hypothesizes that:

H1. There is a positive relationship between the DVB and voting intention.

10. Social media as a mediator between DVB and voting intention

Although DVB may affects (−/+)voting intention in Ghana, this can be reshaped and boosted if it is first targeted at the social media users for their opinion and wide acceptance before implementation since political information in social media tends to influence voters` voting decisions. Voters` opinions on social media normally provide policy implementation trends and directions in the governance process, which should lead to a better understanding of their future demands (Benoit et al., 2010; Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015). When a political party develops its DVB considering its opinions on social media, it can develop more strategic options and implement effective policies to increase voting intention. DVB are was therefore seen as a second-order determinant whose effect on voting intention is mediated by other first-order determinants (Dabulah, Citation2017). For instance, political parties with good standing in terms of DVB can stay close to voters and, therefore, generate and respond to intelligence on voters’ present and future needs better (Newman, Citation2002). Paying attention to voters also helps political parties develop innovative products and services tailored to voters` preferences, improving overall voting intention (Newman, Citation2002). DVB allow political parties to develop new ideas on what voters are asking for, which leads to the introduction of good policies. This indicates that social media plays an important intermediary between DVB and voting intention. Some studies have found that social media mediates the relationship between some determinants and political parties’ performance in an election. Benoit et al. (2010) found social media to mediate the relationship between political issues and voting intention. Benoit and Brazeal (Citation2002) also found that social media is a mediator that improves voting intention. Hoffmann and Suphan (Citation2017) and Jungherr, Schoen, and Jürgens (Citation2016) found social media to mediate the relationship between key determinants of voters` behavior, such as contingent situation, epistemic value, candidate personality, and voting intention. The empirical literature, therefore, supports this study’s assertion that the current political atmosphere provides fertile grounds for social media engagement that can improve political parties’ performance and voters` voting intention.

This study, therefore, proposes a two-step causal chain from second-order determinants (determinants of voters` behavior) to first-order determinants (social media engagement) to election outcomes. In this two-step causal chain, Ghanaian voters’ perspectives expect the outcome to be positive. DVB is expected to facilitate social media engagement aligned with voters’ demands, eventually enhancing overall voting intention.

Lee-Marshment (2009) and (2019) explain that, in the current turbulent political environment, the political party’s role changes from designing product solutions to their expectation of performance to providing the solution to meet the designs and expectations of voters. This, therefore, supports the claim that the voters become the source of introducing new policies and programs, while the political parties provide the platform for this development. However, the ability to perform this function depends on the party’s level of implementation of determinants of voters` behavior. The successful development and implementation of DVB in the political sector are dependent on a political party’s ability to create a platform through its determinants, policies, and program implementations, which allows the political parties to produce the required public goods that satisfy the need of the citizens (see, Bukari et al., Citation2020; Newman, Citation2002). Benoit et al. (2010) suggest that DVB are an important factor in social media engagement and voters` voting decisions. Voters (current and future voters) are the most important stakeholders of the DVB (Neuman &Seth, Citation1981; Newman, Citation2002). Political parties may benefit from their voters by designing and implementing DVB that will be more beneficial to them. As the political parties improve their determinants of voters` behavior, mutual gains are made through seamless interactions with the citizens, an essential element of the entire political process through the continual implementation of good policies (Neuma, Citation2002). This implies that developing and implementing DVB is an important prerequisite for the nature of the social media interactions of the citizens/voters about the potential of the political party in question, which will eventually influence voting intention. We, therefore, submit the hypothesis that:

H2. Social media engagement will mediate the relationship between DVB and voters` voting intention in Ghana.

DVB in social media engagement has received considerable attention in the literature (Benoit, Citation2007; Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015; Dabulah, Citation2017). Benoit et al. (2010), in explaining social media engagement as an important decision-making point, argue that voters take cues from the argument presented on social media in combining positive and negative arguments to make an important voting decision. Voters thus closely interact and engage each other on national issues through social media platforms which eventually influence their voting decisions. DVB allow voters to determine and influence the process through which politicians deliver value to them and thus influence the adjustment of policies and programs of the politicians through social interactions. In the political process, taking a cue from voters/citizens’ opinions on national issues and delivery of public goods is considered fundamental to the programs and policies implementation and as important as the product or service delivered, and value assessment is based on the total experience delivered to the citizens. This is important to the electoral outcome, and the voting decision is largely a function of the determinants of voters` behavior.

11. Research methodology

This study examined the relationship between the DVB and voting intention from Ghanaian voters` point of view. Ghana is arguably the most peaceful democratic country in Sub-Saharan Africa. The country possesses the characteristics of advanced democracy with strong institutions and vibrant media, civil society, the rule of law, pressure groups, and adherence to public opinion (Graham et al. Citation2016; Bukari et al., Citation2022 &, Citation2020). The country is regarded as the symbol of democracy in Africa (Ayee Citation1997; Gyimah-Boadi Citation2001; Daddieh Citation2009; Abdulai & Crawford Citation2010; Gyimah-Boadi & Prempeh Citation2012; Gyimah-Boadi 2015). Ghana has been noted for its free and fair elections since 1992. The country was ranked number one in Africa and twenty-three in the world regarding press freedom. As of 2010, Ghana’s population was about 25 million, with an annual growth rate of about 2.7% per annum (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2012; Citation2016). The country’s political system is a multiparty democracy.

Ghana’s registered voters as of December 2016 were 15,712,499, representing 71.35% of the total population (Ghana Statistical Service, 2016). Ghana became the first black African nation in the Sub- Sahara to gain political independence. The voting pattern has been inconsistent, with an average voter turnout of less than 70%. This assertion makes Ghana a crucial example for evaluating emerging Sub-Saharan African voting behavior. Voters` behaviour research has gained significant attention from qualitative and quantitative researchers’ perspectives (Newman and Seth, 1981; Newman, Citation2002). Smith (Citation2009) and Davies and Chun (Citation2002) argued that qualitative research is most relevant at early stages and largely in areas relatively under research. Building on this logical argument, an area like this requires a quantitative approach. Therefore, the study employed a deductive approach to the quantitative inquiry on determinants of voters’ behavior (Sambassivan et al., Citation2019) to understand the Ghanaian voters` perception of the DVB and its role in their voting decision. This makes it possible to unearth areas where problems are likely to be emanated from and how to overcome them. Consistent with this logical argument, this paper employed a quantitative approach using a structured questionnaire to solicit the views of Ghanaian voters to understand their voting intention (Sambassivan et al., Citation2019). A deductive approach to scientific inquiry generally gives room for a wider opinion about the issue under discussion; hence, generalization of the findings is a guarantee (Hair et al., Citation2001). Quantitative research techniques were employed with the help of a questionnaire to solicit the views of the eligible voters in Ghana who have voted in at least two consecutive elections. This was to help the research participants respond adequately to the issues under discussion while addressing the research questions and the stated objectives. This approach has been deemed appropriate as the study employed standard procedures, and replication of findings is a guarantee. Using the quantitative approach helped the researchers to avoid several issues, which would have been encountered, if the qualitative approach had been employed in the study, more importantly, validity, generalizability, access and consent, reflexivity, voice as well as transparency (Butler-Kisber, Citation2010, 13). However, the validity of this study is, nonetheless, a function of the quality of the data collected and the interpretation of findings to the extant literature.

11.1. Time horizon

The researchers employed a cross-sectional survey design to collect data relevant to the study. Some political marketing researchers (Ahmed et al., Citation2011 & Rahmat, Citation2013) have adopted the cross-sectional method in their data collection, and the findings have proven worthwhile.

11.2. Target population

Employing a purposive sampling procedure, the study targeted only registered voters in Ghana who have voted twice or more to determine how their experience influences the relationship between DVB and voting intention. This is because experience voters can conceptualize and evaluate political parties or candidates’ activities and make informed decisions based on the perception they form about the information in the media. Eligible Ghana voters are adults aged eighteen years or more and will exhibit maturity in responding to the issues under consideration. Specifically, the data were collected from 23 constituencies in the Greater Accra region of Ghana. This was based on the fact that Accra is a cost metropolitan city in Ghana and comprises people from all parts of the country in terms of geo-demographics characteristics, the region has also been regarded as one of the swing regions in Ghana’s general elections since 1992 (Electoral Commission of Ghana, Citation2016). The research participants (voters) were approached for information, and their eligibility was assessed in three key areas (Morgan, Katsikeas, & Vorhies, Citation2012): (1) knowledge about the questions, (2) accuracy of the information provided, and (3) confidence in the answers provided. The three key areas were included in the questionnaire. The measures were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). A minimum score of 6.25 was obtained, which indicates that the research participants have adequate knowledge of the issues under discussion and were optimistic in their responses.

11.3. Data collection procedure and sample size

The questionnaires were delivered personally to 600 registered voters who have voted in not less than two continuous elections. However, those considered cleaned and valid after the data cleaning for the analysis were 520. The researchers use a sample size table proposed by Krieger and Morgan (Citation1970) and Bartlett Kotalik and Higgins (Citation2001), which states that a population between 250,000 and 300000000 can have a population of 384 and above. A-PRIORI sample size calculator for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) by Soper (Citation2015) supports this, and a Sample size formula proposed by Yamane (Citation1967). The data from the electoral commission’s website has up-to-date statistics about the registered voters in Ghana. There were nearly 4 000,000 registered voters in the Greater Accra region. The data was analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) PLS. PLS became necessary as the questionnaires were adapted from the literature; therefore, employing CFA to ensure the instrument’s suitability was crucial. It further advocates that it is essential to interact all the variables used in the study in one model, and SEM was deemed appropriate.

11.4. The rationale for using structural equation modeling PLS

Two approaches are commonly used in estimating relationships in SEM. These include a Covariance Based SEM, popularly referred to as CB-SEM and another; variance-based SEM, commonly referred to as PLS-SEM. CB-SEM is used mostly when the study’s objective is theory confirmation, whereas PLS-SEM is useful when the objective is theory development (Hair et al., 2014). However, Hair et al. (2011, p. 139) argued that PLS-SEM is predictive modelling mainly targeted at maximizing the explained variance of the endogenous latent construct. The current study employs the use of Partial Least Squared Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) given the fact that it is increasingly being employed in modern social science research, perhaps because of its strength over other Covariance-Based SEM (CB-SEM) techniques (Ringle, Serstedt, & Straub, Citation2012; Henseler, Ringle, & Sinkovics, Citation2009). In the view of Hair et al. (2011), although PLS-SEM is now becoming popular with marketing and management research, its path modelling is considered a “silver bullet” which can be employed in estimating causal relationship models. They thus called for the inclusion of PLS-SEM, given its uniqueness as one of the useful approaches to SEM. PLS-SEM allows formative measures largely different from reflective measures to be used in PLS-SEM-based analytical tools.

Another reason for using PLS-SEM for the current study is its ability to deal with structural and predictive questions. This makes it a better choice to use in assessing the interrelationships among the latent constructs of determinants of voters’ behavior, voters’ trust, voters’ loyalty, and voting intention. Again, as stated earlier, the purpose of this study is explanatory. The research is meant to provide further explanation on how determinants of voters’ behavior influence voting intention

12. Analysis

Five hundred and twenty (520) valid questionnaires were used for the analysis out of 600 administered questionnaires; this accounted for 86–7%. The data on gender revealed 234 males were 347(66.7 %) and 173 females (33.3%). The respondents’ age distribution showed that those between 22 and 30 accounted for 340 (65.38%), and respondents above 30 were 180 (34.6%). The analysis of the educational background of the respondents revealed that the majority were at least High School levers, 251 (48.28%), the least 88 (16.9%) had no former education, and 9(1.7%) had Doctorate degrees. The statistics on the respondents’ occupational background established that the majority were either doing their own business or self-employed; 245 (47%) and the least 2 (0.52%) did not indicate their occupational background. Regarding the voting experience, 111 (21.3%) have voted in two or three continuous elections. In addition, 409 (78.9%) have voted in more than three continuous elections.

12.1. Common method variance bias

Because all the data for this study were collected using a single instrument. There was the likelihood of common method bias (CMB).

The study checked common method issues through four techniques- correlation matrix (Pavlou, Citation2006 #2465), Harman’s single factor procedure (Podsakoff, Citation2003; Podsakoff, 2012), full collinearity assessment (Kock, Citation2012; Kock, 2015), and Unmeasured Latent Marker Variables (Podsakoff, 2012). The correlation matrix result showed that the maximum value was 0.798 between political issues and voting intention, which is less than 0.90. Again, the widely used Harman’s single factor test for CMB was 23%, less than 50% (Kumar, Citation2012). The correlations matrix and single factor test result showed that no common method bias issue prevails in this study. However, Harman’s single-factor test and correlation matrix are no longer useful for checking CMB (Guide, 2015). In the third approach full collinearity assessment suggested by (Kock (Citation2012) and Kock (2015) showed that the VIF values were less than 3.30 (Kock, Citation2012) except when the epistemic value was the dependent variable. In the case of epistemic value as a dependent variable (shown in Table ), four VIFs were more than 3.30 (the highest was 3.85) but less than 5.0 (Kock, Citation2012; 2015). This full collinearity assessment approach also showed no common method issue in this study.

Table 1. Common method bias test through full collinearity (VIF)

In the fourth approach, the study used an unmeasured latent variable marker (ULVM). The highest variance explained factor as a marker variable was extracted from exploratory factor analysis using principal axis factoring rotation. The SmartPLS algorithm analysis showed that with and without unmeasured, variable R square varies slightly. As Table indicates, the R square changed by 7.29% in the case of voter intention, which is less than 10% (Chin, Citation2012; Williams, Citation2016). This assessment’s results indicated no significant concern regarding CMB in the current study.

Table 2. Common method bias test through Unmeasured Latent Variable Marker (ULMV)

Table shows the various parameters of the measurement model (Outer Loading, Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite reliability, and Average Variance Extracted). The factor loadings ranged between 0.643 and 0.892; Cronbach’s Alpha between 0.726 and 0.953; Composite Reliability between 0.847 and 0.959; and AVE between 0.532 0.704. The values were higher than the respective threshold values. Thus, the measurement model’s result met the convergent validity criteria [Cheah, Citation2019 #3533; Hair, 2019 #3648; Sarstedt, Citation2019 #3532].

To assess the measurement model, another criterion is utilized-discriminant validity. Discriminant validity was determined using the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The result showed that the factors met the requirement of the discriminant validity based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion, as shown in Table , and the HTMT ratio, shown in Table . All squared roots of AVE of the respective constructs were always greater than the correlation of the construct with others. Discriminant validity was approved based on HTMT0.90 criterion [Kline, Citation2011 #2283].

Table 3. Convergent reliability (outer loading, cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability and average variance extracted)

12.2. Structural model

Before assessing the structural model, the study initiated the multicollinearity test because this test is essential before conducting the bootstrapping analysis. Multicollinearity issues prevail if two predictors are highly correlated (r > 0.90). Collinearity is measured through a variance inflation factor (VIF) of less than 5 (VIF < 5) [Hair, 2016 #2177]. A high signposts the biasness beta (β) for multiple regression. The study finding showed that VIF is less than 3.00. Therefore, the model does not include multicollinearity issues. (See Table )

Table 4. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)

Table 5. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT)

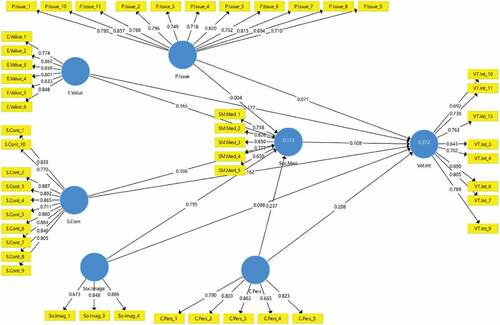

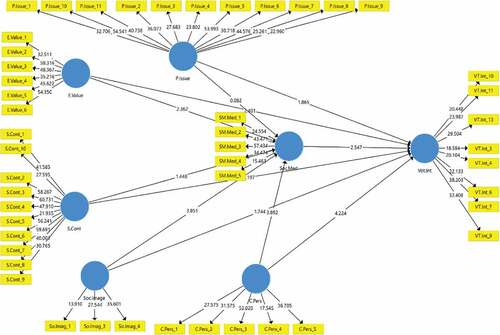

The study performed bootstrapping analysis based on 5,000 iterations. BC bootstrapped and two-tailed test. Table and Figure show the result of the structural model. Among eleven hypotheses seven hypotheses were accepted: candidate personality(β = 0.236, T = 3.789, P = 0.000), epistemic value (β = 0.167, T = 2.47, P = 0.014), social image (β = 0.196, T = 3.718, P = 0.000) have positive effect on social media. Similarly, candidate personality (β = 0.209, T = 3.908, P = 0.000), epistemic value (β = 0.177, T = 2.248, P = 0.025),S. Cont.(β = 0.162, T = 2.226, P = 0.026)have positive impact on voting intention. Further, social media (β = 0.107, T = 2.482, P = 0.013) influences voting intention positively and significantly. Overall, the predictive accuracy (R2) is 0.173 and 0.372 for social media and voting intention, respectively. Similarly, the predicted relevance (Q2) is higher than “zero,” implying high predictive relevancy (See Table and Figure ).

Table 6. Fornell-larcker criterion

Table 7. Hypothesis and co-efficient

12.3. Mediation effect of social media

In this study, social media mediated between predictors and predicted variables. This present research utilized a bootstrapping method with 5,000 subsamples at the 95% confidence interval (Preacher and Hayes, Citation2008). Table showed that social media significantly mediated the relationship between candidate personality and voting intention (B = 0.025, T = 2.123 p = 0.034, LLB = 0.003 and ULB = 0.050) and relationship between social image (B = 0.021, T = 2.089 p = 0.037, LLB = 0.005 and ULB = 0.045). In both cases, the p-value was significant, and there was 0 “zero” between the lower limit and upper limit band. The study further identified the nature of mediation that the direct and indirect relationships of social media are significant with voting intention. Thus, social media partially mediated this relationship (Baron and Kenny, Citation1986). On the other hand, social media has an indirect effect, not a direct effect, on intention voting with the presence of social media. Thus, this is fully mediation.

13. Discussions

The primary aim of this study is to contribute to the body of knowledge in political marketing by proposing and empirically testing a predictive model developed to examine the effects of DVB on voting intention in Ghana. As a way forward measure, two key objectives were formulated to examine the direct relationships between DVB dimensions and voting intention, mediating the role of social media in the relationship between DVB dimensions and voting intention. This recent study, as opined in the introduction, is underpinned by the presence of a research gap in DVB and Voting intention literature, which indicates that very little empirical attention has been given to both the direct and indirect relationship between DVB dimensions (political issues, candidate personality, epistemic value, situational contingency, and social imagery) and voting intention. As already indicated in the first chapter of this study and the literature review, very few empirical findings exist to support the mediating role of social media in the relationship between DVB and voting intention from an emerging democratic context like Sub-Saharan Africa, more importantly, Ghana (See Table ).

Table 8. Specific indirect effect

The current study seeks to examine the determinants of voters’ behavior for efficiently and effectively influencing voting intention and the mediating effect of social media on the relationship between DVB and voting intention. The current findings support the three hypotheses specified and present significant implications for theory and practice. The first hypothesis opines that DVB would positively influence voting intention. This was supported at the general sample analysis level and therefore gives credence to the existing findings of political marketing scholars. The finding is consistent with the claim made by Neuman (Citation2002) and Neuman (2008) that the DVB is an important source of competitive advantage. During the election and has the potential to influence voters` behavior. Political parties with the right kind of DVB implementation could exploit this to improve their electoral outcome. This positive finding, however, confirms the assertions of Elinder et al. (2015) and Pasek et al. (Citation2009), and Strauss (Citation2009) that good development and implementation of DVB improve voting intention. This indicates that DVB thus allows political parties to create the environment for the voters to perform the two distinct roles of performance evaluation and promoting development. However, the disaggregated analysis at the specific construct/variable level reveals that the much-emphasized positive relationship can be constructed/variable-specific and that the relationship is not positive in all situations.

While a positive relationship was found with candidate personality, epistemic value, and situational contingency, a negative relationship was found with political issues and social imagery. The findings reinforce Dabulah, Citation2017, and Morar and Chuchu’s (Citation2015) argument that it will be inappropriate for us to assume that all the determinants can equally be accepted under any condition and any given situation and further posit that circumventing developmental policies and programs implementations issues of this nature when communicating research applicability would be inappropriate. The specific construct/variable findings attest that issue-specific is fundamental. The results may be explained by factors such as culture, geography, demographics, and some of these determinants of voters’ behavior dependents characteristics. Elinder et al. (2015) and Icatalupo (Citation2018) explain that the human development index in the form of standard of living, cost of living, and geo-demographics characteristics may explain the differences between these constructs/variables in an emerging democracy like Ghana. The positive relationship between determinants of voters’ behavior variables (political candidate personality, epistemic value, and contingent situation) and voting intention in Ghana may be explained by the fact that Ghanaian voters are more concerned about the political leaders’ abilities to deal with unexpected situations when they occur. This is due to the political challenges confronting the country and its citizens over the past decade (Bukari et al., Citation2020, Citation2020). They expect the political leaders to have contingency plans to handle unexpected situations such as flood fire outbreaks and corrupt cases (Incantalupo, Citation2018; Strauss, Citation2009; Pasek et al., Citation2009 & Bukari et al., Citation2020). They are also more attentive to the country’s political atmosphere and economic situations before the election and the leaders` general behavior in dealing with issues. They tend to make voting decisions based on certain cues. They are, therefore, very likely to directly reward political parties and leaders with the required calibre of skills and capabilities to deal with their peculiar situations. Political parties in such an emerging democratic environment where cost and living are fundamental to the citizens may benefit directly from their DVB more than political parties in a different democratic environment. In developing countries such as Ghana, the nature of association political leaders form with a certain cohort in society or between individuals is much of a concern to the voters. They don’t see this as a threat to the political leaders’ performance, and there has not been an issue in our political history where a political leader’s social relation has been a factor that impedes their performance in office. Political parties/leaders may, therefore, not benefit directly from the effect of social imagery on their electoral performance but may influence the voting decision in various ways. Consequently, political parties in a democratic environment like Ghana should see DVB as a second-order functioning to improve the implementation of other determinants.

In hypothesis H2 social media engagement was seen as a mediator. The results are consistent with Benoit (Citation2007), who found that social media engagement mediates the relationship between political issues and voting intention. These results also agree with Hoffmann and Suphan (Citation2017) and Jungherr, Schoen, and Jürgens (Citation2016), who found that social mediate the relationship between contingent situations and political parties in an election. The findings confirm and Benoit’s (Citation2007) argument that DVB is an important factor that increases social media engagement. The DVB of political parties enable them to draw upon voters` dual role of performance evaluation and voting decision (Newman, Citation2002, p. 2007). A high level of DVB implementation creates a platform for better political party voter engagement. The voter, as a stakeholder, can employ the economy, efficiency, and effectiveness mixed in their evaluation of the political parties’ performance and voting decision. The findings corroborate Pasek et al. (Citation2009), Dendere (Citation2013), and Bukari et al. (2019) assertion that paying close attention to the citizens/voters` requirement, which is made possible by determinants of voters’ behavior, helps political parties to develop innovative policies and programs to their citizens/voter preferences and to improve their overall performance at the end. Notwithstanding the lack of a positive and direct effect of DVB variables (social imagery and political issues) and voting intention, the findings show that DVB is an important antecedent to social media engagement for an improved voting intention.

Like commercial business and marketing, one of the primary aims of the political party is to discover voters’ response to their product; communications are therefore targeted at the target audience as Lees-Marshment (2009) Party posits; therefore, design its behaviour in response to voters demands. This is made possible through product adjustment. The party then adjusts its model product design to consider voters’ requirements. The product design is implemented throughout the party, where the majority must broadly accept the new behaviour and comply with it before an election. After the election, the party then considers delivery management and communication through continual market consultation, responsive product re-development and strategic thinking, product refinement in response to the competition, the internal market, such as party members, and public support, maintenance or re-establishment of a market-oriented attitude among, MPs and the leadership becomes strategic agenda of the political party after winning election Lees-Marshment

13.1. Theoretical implications

The application of psychological, sociological, and the dominant media ideology in this context will help promote the theoretical boundary of the marketing field and may even lead to the development of a new theoretical framework that blend the disciplines of marketing, psychology, sociology and communication for a proper contextual delineation. This perspective is yet to receive attention in the literature. The emphasis has largely been on individual theoretical applications. This study contributes to the literature on DVB and voting intention. In the current turbulent political environment, voters play a vital role in the policies and programs implementations in their electoral areas and make significant contributions towards its improvement, as opposed to being passive recipients of political products from politicians (Benoit & Airne, Citation2005). This implies that political parties that can develop and implement their DVB efficiently and effectively can yield an effective voting decision. Despite the breadth and depth of the existing research on determinants of voters` behavior, the empirical findings on determinants of voters` to efficiently and effectively facilitate voting decision has received fairly scant research attention. This study has empirically demonstrated and confirmed Neuman’s (Citation2002) assertion that the determinants of voters’ behavior implementation in the political context are a primary function of the political parties, and that is the political party’s responsibility to ensure efficient and effective implementation. The empirical findings thus suggest that developing and implementing these determinants enables political parties to create a platform for the voter to evaluate their performance and subsequently make an informed voting decision (Neuman & Seth, Citation1981, Newman, Citation2002 & 2008). Political parties with the required determinants can yield a politician-voter mutually beneficial relationship. The theoretical implication of the first hypothesis is that voters are market-based resources available to all political parties. Developing the right DVB to exploit this market-based resource is fundamental to the electoral outcome.

DVB has become an important political party resource with the potential to influence voters` voting intention because it allows the political parties to implement policies and programs to meet the expectation and requirements of the voters/citizens. A determinant of voters` behaviour thus enables dynamic fitness between voters and politicians through efficient and effective resource allocation to enhance the voters’ standard of living. This study shows that the effect of DVB could is variable-specific and that individual preferences, values and priorities may directly influence the impact of determinants of voters’ behavior on voting intention. Although DVB may has important effects on voting intention, it will be inappropriate to conclude that these effects are universal (Dabulah, Citation2017; Morar & Chuchu, Citation2015). The current findings thus give credence to the significant disparity in the effect of DVB research (Neuman & Seth, Citation1981; Newman, Citation2002, pp. 2007, Morar, Chuch, Citation2015, Dabula, Citation2017). DVB are is seen as possibly having some cultural, demographics, geographic, and geodemographic influences, and the effect of the determinants of voters’ behavior may be a function of some of these factors and the environment in which the DVB voter intention relationship takes place. Finally, the application of determinants of voters` behaviour as an antecedent to voting intention has generated an interesting debate in the political marketing literature due to the fluctuating outcomes recorded in empirical research (Bukari et al., Citation2020, Citation2020; Newman, Citation2002). This study reveals that some individual preferences and conditions influence the relationship between DVB and voting intention.

In providing empirical support for the likely boundary condition effect, the current study reveals that social media engagement mediates the relationship between DVB and voting intention. This implies that the relationship can be optimized if political parties see voters’ determinants as an antecedent to other, higher-level determinants. The results of the current study reveal that determinants of voters’ behavior should be seen as a second-order determinants whose effect on voting intention is best predicted through first-order determinants, such as social media engagement. The current study, therefore, provides empirical support for the specific outcome of the second-order determinants, such as DVB which Neuman (Citation2002) argued has received fairly scant research attention. DVB as, a second-order determinant, enhance the implementation and the effect of first-order determinants such as social media engagement.

13.2. Practical implications

Besides theoretical implications, one practical implication of this study is that the development and implementation of the DVB create the necessary environment upon which voters can evaluate the political leaders and their activities on various factors. Even though voters may play a vital role in the electoral process, their effectiveness largely depends on how well the political parties facilitate the process through its DVB implementation. The DVB improve their chances of creating a competitive advantage and enhancing voting intention. As indicated earlier, the voter is a market-based resource available to all political parties, so the political party that can exploit this resource creates competitive advantages and stands a better chance of winning the election. Political Parties should utilize this avenue to their advantage through the DVB to get the best from voters. While DVB appear to be an important factor to the political parties, the level of proceeds generated from it may be issue dependent. In a political environment where there is a high level of expectation for a particular determinant, for example, political parties may be able to benefit more from implementing a determinant than can a political party that implements it in an environment with low expectations. Political parties and their leaders must remember that while some DVB (political issues, contingent situation, and candidate personality) may be beneficial, such benefits will be more rewarded in a political environment where such determinants are prioritized. The implication, therefore, is that DVB implementation cannot be universal without considering individual needs, want, expectation and experience. In their quest to yield the maximum benefit from determinants of voters` behavior, political parties must examine the behavior of the voters in terms of need assessment. Even though the effects of DVB may are not ordered, this study’s findings posit that it has the potential to influence the overall outcome through social media engagement to influence voting intention positively. This study, therefore, gives credence to the appropriate application of DVB as as an antecedent to other higher-order determinants and the fact that its impact on voting intention is best observed through such higher-order determinants (e.g., social media engagement). Political parties should pay attention to social media engagement in determining voters` behavior development, as the former facilitates the latter’s effectiveness in enhancing voting intention.

13.3. Limitations and directions for future research

The current study is not without limitations like any other research; the researchers also acknowledged some worth of attention. To begin with, the study focused only on Ghana in assessing the emerging democratic environment. Although Ghana shares common characteristics with others within similar contexts, there may be notable differences that must guide political leaders in applying the study’s findings and implications. Future studies may extend the study beyond Ghana in testing the current study’s model. Such studies may consider how voters react to determinants of voters’ behavior in other contexts to their expectations and experience and how they influence their voting intention. In another case, further studies may consider alternative data collection and analysis methods, such as structural equation modelling, longitudinal panel data, objective performance, and importance-performance matrix, in future studies to test this study’s model. For example, the use of cross-sectional data did not allow for examining the extent to which DVB influence voting intention over time. Future researchers should explore longitudinal data to see the pattern of change and the extent to which DVB influence voters` voting intention over time in a different political environment. The data was collected from voters with two more voting experiences; first-time voters and those who are yet to vote were not included, further may consider cohort. Furthermore, even though this study does not segment the voter market and examine the effect of a specific segment on the model, it would be interesting for future studies to look at the nuances in specific segments and the cohort effects in different contexts. Notwithstanding these limitations, they are firm believers that the current study offers insightful theoretical and practical implications regarding applying the DVB and to their boundary conditions and integrating first and second-order determinants in a different political context.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to use opportunity to offer their deepest appreciation and gratitude to the various faculties and management at Putra Business School, Dr. Thomas Anning-Dorson of the Wits Business School, University of the Witwatersrand St David’s Place, Parktown, Johannesburg, and all those who play role in this research for the various contributions in getting this research completed successfully.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zakari Bukari

Zakari Bukari Affiliated institution; Department of marketing and supply chain management putra business school Dr. Zakari Bukari is a Research Assistant at the Department of Marketing and Entrepreneurship, University of Ghana Business School, Legon. He had his Ph.D in marketing at Putra Business School of University of Putra Malaysia. He obtained his MPhil in Marketing from the University of Ghana Business School and Bachelor of Science in Marketing from the University Professional Studies, Accra. E-mail: [email protected]

Abu Bakar Abdul Hamid

Abu Bakar Abdul Hamid has chosen academic as his profession in 1992, from a lecturer and later rise to a Professor of Marketing and Supply Chain Management. He holds a BBA and an MBA from Northrop University (USA) and PhD from University of Derby (UK, 2003). He has demonstrated an excellent record of teaching and supervision for more than 25 years in the academic field, both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Above all, his achievement in graduating more than 35 PhD candidates proves his ability, capability and passion in postgraduate supervisions. E-mail: [email protected]

Hishamuddin Md. Som

Hishamuddin Md. Som obtained his Bsc in Business Administration and M.B.A. from University of San Francisco, United State Of America and a PhD in Human Resource Management from University of Stirling, United Kingdom. Prior to joining Academia at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia in 1989, he has had extensive experiences in various capacities in the manufacturing sector and as a banker for Standard Chartered Bank, Empire of America (San Francisco, USA) and Central Bank Malaysia He is an editorial board member of several journals and have held several administrative posts as Assistant Dean (Postgraduate Studies) & Head Of Department as well as a Senate member and Committee members at the University & Faculty level of various universities. He is actively involved in numerous research and consultation activities at home and abroad and has also written several books and published in refereed international and national journal as well as proceedings. E-mail: [email protected]

Md. Uzir Hossain Uzir