Abstract

This research aims at examining determinants of battery electric vehicle (BEV) purchase in Vietnam market from both self-interested and pro-environmental perspectives. Data collected from 200 BEV drivers show that purchase intention is positively affected by self-interested factors such as performance expectancy, effort expectancy and facilitating conditions. Additionally, intention could be shaped by personal norm, which is influenced by awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility. Finally, intention is a reliable predictor of purchase behavior, and the relationship is moderated by personal innovativeness. This research provides various theoretical and practical implications to enhance public acceptance towards BEVs.

1. Introduction

Global demand for energy is on the rise. Despite a slight drop in 2020 due to the impact of Covid-19, the energy demand in 2021 is projected to recover and increase by 4.6%, exceeding the pre-Covid-19 level (International Energy Agency, Citation2021). Along with the recovery of energy demand, the amount of CO2 emissions is predicted to reach 33 Gt (International Energy Agency, Citation2021), which contributes greatly to climate change, respiratory diseases, and air pollution. Transportation sector, which is responsible for 7.3 Gt of CO2, is a major source of emission (Statista, Citation2020). In an attempt to alleviate the impact of transportation activities on the environment, many Western governments have taken actions to phase out conventional vehicles and promote electric vehicles (EV; Hasan, Citation2021). EVs refer to cars that depend partially or solely on electricity to operate (Adnan et al., Citation2017). EVs can be categorized into 3 types, namely Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV), Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV), and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV; Shalender & Sharma, Citation2021). In addition to government initiatives, automobile manufacturers have been switching to sustainable practices to attract green consumers. For example, Volvo has started using renewable biogas instead of natural gas for heating its factory in Sweden; it is also promoting a green lifestyle by offering the market with its mass-produced EVs (Awan, Citation2011).

In Vietnam, The Prime Minister (Citation2014) has approved the strategy for developing automotive industry by 2025 in which expanding domestic EV market is one of the top priorities. Nevertheless, there were no specific objectives related to the number of EVs to be achieved. However, there has been a positive sign in EV adoption since the end of 2021 when VinFast (the first Vietnamese EV manufacturer) started delivering 25,000 orders of made-in-Vietnam EVs which is expected to spring up EV ownership in the country (Nguyen, Citation2022).

As Vietnam’s EV market is currently in an early stage, examining factors affecting the customer’s purchase decision is an important task. However, most previous studies paid attention to purchase intention instead of actual behavior. For example, Xu et al. (Citation2019) reported that attitude, perceived behavioral control, subjective norm, environmental performance, and monetary policy positively affected the EV purchase intention of Chinese customers. The research of Nazari et al. (Citation2019) showed that gender, education, ethnicity, income, and pro-environmental behaviors are associated with the EV purchase intention in the US. Jreige et al. (Citation2021) found the impact of range, car ownership and cost on purchase intention. Although intention is a strong indicator of behavior, research on EV purchase should not stop at purchase intention. This study not only examines determinants of EV purchase intention, but also further explore the intention–behavior relationship and its moderator. Additionally, early studies usually applied the Theory of Planned Behavior of Ajzen (Citation1991) to explain EV purchase (Haustein & Jensen, Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2020; Schmalfuß et al., Citation2017; Xu et al., Citation2019). However, the TPB model only explains consumer behaviors from a rational self-interested perspective (Asadi et al., Citation2021). As EV purchase is an innovation adoption as well as a pro-environmental behavior, this study proposes to incorporate both self-interested and pro-environmental motives in order to fully understand customers’ decision. This study is expected to contribute a comprehensive theoretical basis and empirical evidence in Vietnam market to enrich current knowledge of EV purchase decision.

2. Literature review

Purchase decision is an important part of customers’ decision-making process, in which the customers turn their purchase intentions into actual purchase behaviors. In fact, an intention does not always lead to an actual product choice and this phenomenon is termed as “intention-behaviour gap” in previous literature (Moghavvemi et al., Citation2015). Although intention is an important predictor, greater interest is placed on actual purchase behavior and factors that moderate the intention-behavior relationship. Nevertheless, most recent studies related to EV purchase have focused on purchase intention rather than actual purchase behavior. Various determinants of EV purchase intention have been identified and they can be categorized into 4 groups, namely demographic, product attribute, supporting conditions and psychological factors. The effects of demographic factors including age, education, gender, and income were found in previous research. People expressing high purchase intention towards EVs are usually young men and have a high level of education as they are highly aware of environmental issues (Chen et al., Citation2020; Lu et al., Citation2020; Nazari et al., Citation2019). Medium and high income are also positively associated with EV purchase intention as the price of an EV is higher than a conventional vehicle (Berneiser et al., Citation2021). In addition, product features such as environmental performance, charging time, range and cost are important predictors of intention (Haustein & Jensen, Citation2018; Jreige et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2018; Xu et al., Citation2019). She et al. (Citation2017) pointed out that range, reliability, safety, battery and charging time are the main inhibitors preventing customers from purchasing an EV. Particularly, many respondents concerned about battery depletion during travel, long charging time, the likelihood of incidents, and immature technology. Meanwhile, other product features were identified as the drivers of purchase intention such as ease of use, faster acceleration, and cost savings (Chen et al., Citation2020). Moreover, supporting conditions such as policy and infrastructure are also the antecedents of EV purchase intention. Specifically, purchase subsidies, tax exemptions, preferential insurance policies, bus lane driving permission, and public parking benefits were found to positively affect EV purchase intention (Kim et al., Citation2019; Lu et al., Citation2020; Xu et al., Citation2019). Similarly, the availability of charging station and fast charging option also strengthens EV purchase intention (Ščasný et al., Citation2018). Regarding psychological factors, attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control (PBC) were commonly mentioned in earlier research. A qualitative study conducted by Van Heuveln et al. (Citation2021) found that attitude about EVs drives customer’s purchase intention and it is formed based on benefit-barrier calculation of EV technical features. Furthermore, the intention is also shaped by social influence (subjective norm) and customer’s perception of sufficient ability and resources to use EV (perceived behavioral control). These findings are also validated in other quantitative studies (Ackaah et al., Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2020; Du et al. (Citation2018). Other psychological variables in previous research include product knowledge (Kim et al., Citation2019), environmental concern (Wang et al., Citation2021), motivation (Rezvani et al., Citation2018), perceived risk and perception of brand (Jiang et al., Citation2021). Only a few studies examined the actual purchase behavior of customers towards EVs. Afroz et al. (Citation2015) posited that the impact of attitude, subjective norm and PBC on EV purchase behavior is mediated by intention. Adnan et al. (Citation2017) reported that intention is a powerful predictor of behavior, and the relationship is moderated by environmental concern. So far, much research effort has been directed to EV purchase intention, meanwhile, the path from intention to actual purchase behavior and its moderators are barely explored. This is the first gap in existing literature that the authors attempt to fill.

The second research gap regards the approach of researchers in previous studies. One of the most popular underlying theories used to explain customer behavior towards EVs is the Theory of Planned Behavior—TPB developed by Ajzen (Citation1991). TPB proposes that an intention can predict a behavior and it is influenced by (1) attitude—the positive or negative evaluation of individuals regarding the behavior, (2) subjective norm—the influence of other individuals, and (3) perceived behavioral control (PBC)—perception of ability and available resources to conduct the behavior. Although TPB is extensively used in explaining transportation behavior (Sang & Bekhet, Citation2015), empirical studies using TPB found mixed findings in reality. Xu et al. (Citation2019) reported that all 3 constructs of TPB show positive impact on EV purchase intention in China. Nevertheless, another research in China conducted by Huang and Ge (Citation2019) only confirmed the impact of attitude, PBC. Asadi et al. (Citation2021) reported positive effects of attitude and subjective norm, but not for PBC. Furthermore, the explanation power of the TPB often faces criticisms. According to Hasan (Citation2021), the predictive power of TPB is low due to insufficient determinants and it assumes that the decision-making process is systematic and rational. As noted by Asadi et al. (Citation2021), the original TPB only emphasizes on self-interest factors. Meanwhile, EV purchase is not only an innovation adoption behavior (based on rational self-interest) but also a pro-environmental behavior (based on altruism; Rezvani et al., Citation2015). Thus, explaining EV purchase decision might require the combination of both approaches. In order to fill this gap, instead of extending TPB model, this research proposes to explore factors affecting EV purchase by incorporating the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) and Norm Activation Model (NAM). Unlike TPB, which is widely applied to explain behaviors in general, UTAUT was specifically designed to examine innovation adoption behavior (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). With higher predictive power, the UTAUT model has been proved to predict innovation adoption more effectively than the TPB (Samaradiwakara & Gunawardena, Citation2014). Meanwhile, NAM is a powerful model in explaining pro-social and pro-environmental behavior (De Groot & Steg, Citation2009). The combination of both models allows the researchers to comprehensively explore customer purchase of EVs.

Finally, the results of previous research varied in different context. Studies carried out in developed EV markets usually demonstrated the impact of both self-interested and environmental factors on purchase intention. In a survey of 573 Swedish car owners, the effect of moral norm (norm motivation) on intention is as strong as gain motivations (Rezvani et al., Citation2018). In Germany, EV’s green performance is a stronger determinant of attitude and intention than technical features such as price and range. However, in developing markets, the impact of environmental motive is quite weak or insignificant. Krishnan and Koshy (Citation2021) reported that perceived benefits, social influence, technological consciousness, price, and aftersales service are factors determining the purchase intention of customers in India, whereas environmental consciousness plays an insignificant role. The same result was found in the research of Ackaah et al. (Citation2021) in Ghana market. As Vietnam is a new market for EVs, it would be worthwhile to examine whether the purchase decision is driven by self-interested or environmental factors. It is also noteworthy that, BEV is the most popular type of EV in Vietnam. Additionally, the perception of customers is different among EV types. BEV is more eco-friendly, advanced and requires a significant change in the behavior of user (Westin et al., Citation2018). Therefore, instead of examining all types of EV, this study only focuses on BEV.

3. Theoretical background and hypothesis development

3.1. UTAUT model

The UTAUT model was first proposed by Venkatesh et al. (Citation2003) on the basis of synthesizing 8 dominant theories of innovation adoption. The model was proved to outperform all previous models in terms of predictive power. So far, UTAUT has been widely applied in explaining the adoption of various innovations such as internet banking (Rahi et al., Citation2018), Internet of Things (Ronaghi & Forouharfar, Citation2020), e-government services (Al-Swidi & Faaeq, Citation2019), web-based services (Arif et al., Citation2018) … Among various theories related to innovation adoption, UTAUT is chosen as the base for this research because it is a reliable framework to examine technology acceptance (Samaradiwakara & Gunawardena, Citation2014).

UTAUT was developed based on 4 factors including performance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE), social influence (SI) and facilitating conditions (FC). They are theorized to affect intention and the actual behavior of users.

3.1.1. Performance expectancy

Performance expectancy (PE) is originally interpreted as the perceived benefits or usefulness of the technology that help individuals improve their job performance (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). In this research context, PE refers to the benefits of BEVs that facilitate an efficient trip for drivers (Jain et al., Citation2022). As compared to conventional vehicles, BEVs are more energy efficient (Helmers & Marx, Citation2012), offer faster acceleration, reduce noises, and increase smoothness during their operation, thus drivers might experience higher performance (Skippon, Citation2014). Additionally, BEVs generate no emission when travelling as they are powered by electricity, which helps drivers contribute to protecting the environment (Degirmenci & Breitner, Citation2017). Previous studies reported that when customers perceive high performance, they tend to form intention to purchase BEV (Lee et al., Citation2021; Zhou et al., Citation2021; Jain et al., 2021). Therefore, the authors hypothesize that:

H1: Performance expectancy has a positive impact on intention to purchase BEVs.

3.1.2. Effort expectancy

Effort expectancy (EE) refers to the technology’s perceived ease of use (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). UTAUT posits that the innovation adoption intention not only depends on the benefits but also depends on how easy it is to use the new technology. According to Jain et al. (Citation2022, EVs in general are user-friendly, which requires little effort to learn how to drive. Zhou et al. (Citation2021) stated that BEVs are slightly different in driving style, experience, and additional task (such as charging the battery). Nevertheless, both studies found a positive effect of EE on intention. Therefore, the authors hypothesize that

H2: Effort expectancy has a positive impact on intention to purchase BEVs.

3.1.3. Social influence

Social influence (SI) reflects the degree to which others believe that the individual should adopt a certain technology (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). SI represents the impact of important people’s opinions, such as friends’ and families’, on one’s decision. Representing a recent innovation, a BEV expresses identity and social status of users, thus external opinion might significantly affect intention to purchase (Jain et al., 2021). However, researchers have not reached a consensus on the impact of SI due to mixed findings in previous papers. SI was reported to affect intention in the studies of Krishnan and Koshy (Citation2021) and Carley et al. (Citation2019). Meanwhile, an insignificant effect was found in the studies of Zhou et al. (Citation2021), Wang et al. (Citation2021), and Pradeep et al. (Citation2021). The authors want to verify the effect of SI on intention; thus, the hypothesis is stated as follow:

H3: Social influence has a positive impact on intention to purchase BEVs.

3.1.4. Facilitating conditions

Facilitating conditions (FC) are defined as the users’ perception that the infrastructure is available to support the technology usage (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). In this research context, the availability of charging infrastructure is vital for the acceptance of BEVs (Kalthaus & Sun, Citation2021). Additionally, maintenance facilities and parking lots designed with compatible chargers are also necessary for BEV usage (Zhou et al., Citation2021). The original UTAUT only proposed the impact of FC on actual behavior (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). However, later research pointed out a significant relationship between FC and intention (Dwivedi et al., Citation2019). If customers consider the supporting facilities for BEVs as sufficient, they will express higher intention to purchase (Khazaei & Tareq, Citation2021). Therefore, the authors hypothesize that

H4: Facilitating conditions has a positive impact on intention to purchase BEVs.

H5: Facilitating conditions has a positive impact on BEVs purchase behavior.

3.1.5. Intention and behavior

Intention (IN) represents how much effort a person is willing to make to conduct an actual behavior (BH; Ajzen, Citation1991). Previous theories asserted that as intention becomes stronger, people are more committed to a certain behavior and tend to conduct it in reality. Therefore, intention could be a reliable predictor of behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). The empirical study of Zhou et al. (Citation2021) confirmed the positive impact of behavioral intention on the actual behavior of adopting EVs. Therefore, the authors hypothesize that

H6: Intention has a positive impact on behavior to purchase BEVS.

3.2. NAM model

The Norm Activation Model developed by Schwartz (Citation1977) was first used in explaining altruism or pro-social behaviors, but it was later proved to be useful in explaining pro-environmental behaviors. According to this theory, intention is affected by personal norm (PN), which in turn is influenced by awareness of consequences (AC) and ascription of responsibility (AR). In other words, the intention to conduct a pro-social behavior is guided by an individual’s moral norm. The moral norm is activated when the person is aware of the problem’s consequences and perceive a strong sense of responsibility in addressing it (Asadi et al., Citation2021). It was found that NAM is a mediator model rather than a moderator model (De Groot & Steg, Citation2009), starting from awareness of consequence, leading to responsibility ascription, personal norm, and finally intention.

3.2.1. Awareness of consequences

Awareness of consequences (AC) refers to the perceived negative consequences as a result of not acting pro-socially (Schwartz, Citation1977). In the context of BEV adoption, AC represents the negative effects of using conventional vehicles such as pollution, global warming, or exhaustion of fossil fuel energy (He & Zhan, Citation2018). When individuals perceive the severe impact of not behaving pro-environmentally, they express higher responsibility. Asadi et al. (Citation2021) and He and Zhan (Citation2018) found that when customers are well aware of the serious impact of traditional vehicles on the environment, they show higher ascription of responsibility for using EVs. Therefore, the authors hypothesize that

H7: Awareness of consequences has a positive impact on ascription of responsibility.

3.3. Ascription of responsibility

Ascription of responsibility (AR) is interpreted as the likelihood to take responsibility for the outcomes of an individual’s action (Schwartz, Citation1977). He and Zhan (Citation2018) stated that AR describes the sense of responsibility for the use of conventional vehicles. Customers have greater moral commitment to the environmental protection if they recognize a joint responsibility for the use of traditional vehicles (Asadi et al., Citation2021; He & Zhan, Citation2018). If customers acknowledge that the environmental damage is caused by themselves, the personal norm will be activated (Dong et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the authors hypothesize that

H8: Ascription of responsibility has a positive impact on personal norm.

3.3.1. Personal norm

Personal norm (PN) is a feeling of moral commitment to conduct a certain behavior in accordance with a person’s norms and values (Schwartz, Citation1977). In BEV adoption, PN refers to the feeling of obligation to adopt BEVs instead of conventional vehicles, motivating customers to purchase BEVs (He & Zhan, Citation2018). The positive impact of PN on purchase intention was also documented in various studies (Asadi et al., Citation2021; Du et al., Citation2018; Shalender & Sharma, Citation2021). Therefore, the authors hypothesize that

H9: Personal norm has a positive impact on intention to purchase BEVs.

3.4. Moderating variable

3.4.1. Personal innovativeness

Personal innovativeness (PI) is a characteristic of individuals which represents the openness towards new technologies (Khazaei & Tareq, Citation2021). Highly innovative users are usually innovators and early adopters; and they are potential customers of new innovations (Rogers, Citation2010). Previous research showed that PI was found to positively impact BEV adoption (Berneiser et al., Citation2021; Yang & Chen, Citation2021). So far, little research has tested the moderating effect of PI on intention–behavior relationship. As innovative people are willing to take risk and initiate actions (Berneiser et al., Citation2021), the authors hypothesize that they are more likely to transform intention into action. Therefore, the hypothesis is stated as follow:

H10: PI positively moderates the relationship between IN and BH to purchase BEVs.

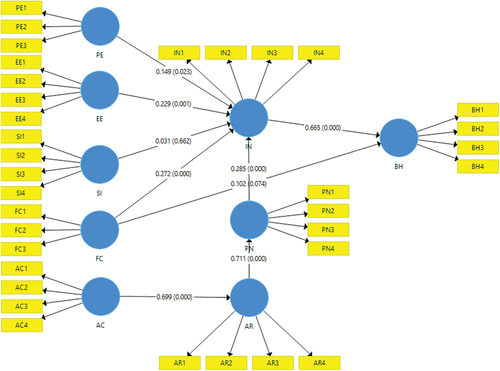

The proposed research model is presented as in below.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research design

In order to understand EV purchase decision, researchers can adopt a qualitative or quantitative approach. Regarding qualitative approach, several researchers conducted in-depth interviews to explore the underlying purchase motives (as in Noel et al., Citation2020; Van Heuveln et al., Citation2021). However, quantitative approach was more appropriate for this study because it allows the researchers to validate the relationships between variables and generalize the results to a large population. A similar approach has been applied in various past studies (Asadi et al., Citation2021; Khazaei & Tareq, Citation2021; He & Zhan, Citation2018).

Vietnamese BEV drivers were chosen as the target of this study as they could provide answers based on their product knowledge and actual experience. Since BEVs are newly introduced in Vietnam, the number of BEV drivers is limited. Therefore, convenience sampling technique was adopted as it facilitates prompt and convenient approach to the chosen target (Malhotra, Citation2009). An online survey was designed for the research purpose. Due to the social distancing during Covid-19 pandemic, the questionnaire was distributed in online form to Vietnamese BEV drivers’ online communities on social networks and website forums. The data were collected from March to June 2022.

According to the 10-time rule, the minimum sample size is equal to 10 times the maximum number of arrows leading to a particular construct which results in n = 50 (Hair et al., Citation2017). However, this simple calculation method could result in inaccurate estimation. According to the inverse square root method proposed by Kock and Hadaya (Citation2016), the minimum sample size n = 160 is acceptable. In this study, the authors received 221 responses in total, in which 21 responses were unqualified due to missing information or similar answer pattern. As a result, the number of qualified responses was 200, which exceeded the sample size requirement.

4.2. Research instrument

The questionnaire used in this research consisted of 2 parts. The first part examined the participants’ assessment of factors affecting their BEV purchases. Measurement items were adapted from previous research of Zhou et al. (Citation2021), Anjam et al. (Citation2020), Adnan et al. (Citation2017), and He and Zhan (Citation2018), and Jain et al. (2021). A 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) was used to measure the items. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of demographic questions, such as gender, age, education, and income. The questionnaire was presented in Vietnamese and then translated back into English. Prior to official distribution, the Vietnamese version of the questionnaire was pre-tested for readability or possible adjustments with the participation of 9 BEV drivers and sellers. The pre-test resulted in minor corrections in the item wording to be more comprehensible in Vietnamese context. The items used in this research are presented in Table .

4.3. Data analysis methods

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized to analyze the collected data as it is suitable for complex models with latent variables. It is a powerful statistical tool to validate complex relationships simultaneously with small sample and makes no assumption of data distribution (Hair et al., Citation2017). The collected data were analyzed by using Smart PLS software. The analysis process went through 4 stages. First of all, the characteristics of the sample were analyzed based on demographic information of the respondents. After that the measurement model was evaluated to ensure its reliability and validity. Then, the structural model was assessed to validate the relationships between variables. Finally, the effect of moderating variable was verified.

5. Research results

5.1. Characteristics of the sample

In general, the percentage of male respondents are slightly more than that of female respondents, accounting for 54.5% of the sample. Drivers of BEVs in Vietnam are quite young as the dominant age groups are 18–30 and 31–40. Most of them are well educated with bachelor’s degrees and their monthly income is below 25 million VND. The profile of participants is illustrated as in .

Table 1. The profile of participants (source: Authors)

5.2. Measurement model assessment

In order to assess the measurement model, the instruction of Hair et al. (Citation2017) was followed. Regarding internal consistency reliability, the data in Table show that the Cronbach’s alpha and CR of all constructs are higher than 0.7, which exceed the acceptable threshold. As for indicator reliability, the outer loadings of all indicators range from 0.716 to 0.896, which are above the suggested value of 0.7. In terms of convergent validity, all AVE values are greater than 0.5, indicating adequate convergence.

Table 2. Evaluation of measurement model (source: Authors)

This study used Fornell-Larcker criterion to evaluate discriminant validity. The results in Table show that the square root of AVE values of all constructs are greater than the correlations with other constructs, suggesting that discriminant validity is verified.

Table 3. Fornell-Larcker criterion assessment (source: Authors)

As the collected data were self-reported from a single source, the occurrence of common method bias (CMB) might be a problem. Therefore, full collinearity test was carried out to detect the occurrence of CMB as proposed by Kock (Citation2015). As shown in Table , the VIF values of all constructs are under the threshold of 3.3, suggesting there is no issue of CMB.

Table 4. Full collinearity test result (source: Authors)

5.3. Structural model assessment

The collinearity values (VIF) of all constructs are below 5 as recommended by Hair et al. (Citation2017), which indicate that there is no collinearity issue. In order to evaluate the model path coefficients, bootstrapping technique with 5000 sub-samples was carried out. According to Table , PE (B = 0.149, p = 0.023), EE (B = 0.229, p = 0.001) and FC (B = 0.272, p = 0.000) have significant positive impacts on IN, supporting H1, H2 and H4. Meanwhile, SI (B = 0.031, p = 0.662) does not affect IN significantly, therefore H3 is rejected. Likewise, FC (B = 0.102, p = 0.074) exerts an insignificant impact on BH, thus H5 is rejected. IN (B = 0.665, p = 0.000) has a direct and positive effect on BH supporting H6. The research results also record the positive effects of AC on AR, AR on PN, and PN on IN, thus confirming H7, H8 and H9. The final structural model is presented in .

Table 5. Structural model assessment (source: Authors)

Adjusted R-squared (R2) values of IN and BH are 0.460 and 0.509, showing that exogenous variables can explain 46% and 50.9% of the variance in the two endogenous variables. f 2 was used to assess the effect size of exogenous variables. According to Cohen’s guidelines (Cohen, Citation1988), the effect sizes of PE, EE, FC and PN on IN are 0.023, 0.054, 0.119 and 0.103 respectively, which represent small effect sizes. The effect size of IN on BH is 0.730 signifying a large effect size. The Q-squared (Q2) values of two endogenous constructs (IN and BH) are 0.320 and 0.343, thus confirming the model’s predictive relevance.

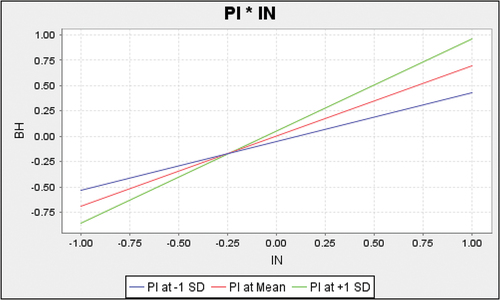

5.4. Moderating effect assessment

The effect of PI on BH is insignificant (B = 0.051, p = 0.467), but the moderating effect PI on the IN-BH relationship (Figure ) is validated. Particularly, the path coefficient of PI*IN is 0.213 (p = 0.003), therefore, PI positively moderates the relationship of IN and BH. The effect size of PI*IN f 2 = 0.143 indicates small effect. As a result, H10 is supported.

6. Discussion

In order to investigate the determinants of BEV purchase, 2 well-known theories have been combined, namely UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003) and NAM (Schwartz, Citation1977). The research results show that BEV purchase is an innovation adoption as well as a pro-environmental behavior.

From the perspective of innovation adoption, the intention to adopt BEVs is affected by performance expectancy, effort expectancy and facilitating condition. When compared to conventional vehicles, BEVs offer many benefits such as emissions reduction, energy efficiency, low noise, and faster acceleration. These perceived benefits (performance expectancy) could reinforce customers’ purchase intention towards BEVs, which is similar to previous findings of Zhou et al. (Citation2021) and Jain et al. (2021). Additionally, effort expectancy is another important factor as customers are more likely to buy BEVs if it takes little effort to drive. This finding is consistent with the research of Lee et al. (Citation2021), which demonstrated that EV purchase intention would increase if the customers considered EVs as user-friendly vehicles. Besides, as the spread of BEVs is heavily dependent on supporting infrastructure such as charging stations and maintenance facilities, facilitating conditions are essential for the adoption of BEVs. The fact that facilitating conditions affect intention instead of actual behavior reflects the decision-making process of customers. Prior to purchasing a BEV, facilitating conditions are taken into consideration and serve as input to form intention. After that, the decision will be carried out with the actual purchase behavior. It is also reported in this research that intention is a very reliable determinant of behavior, which is in line with previous theories (Ajzen, Citation1991; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). Interestingly, social influence does not have a significant effect on purchase intention, which contradicts the findings of Krishnan and Koshy (Citation2021), and Carley et al. (Citation2019). It reflects the fact that the purchase of BEVs is an individual decision in Vietnam market. The same conclusion can be found in the study of Pradeep et al. (Citation2021) in India and Wang et al. (Citation2021) in China context. As BEVs have just been released in Vietnam recently, their features and related information have not reached a wide range of audiences. Thus, BEV buyers are usually innovators or early adopters, and they are less likely to be influenced by others.

From the pro-environmental point of view, this study shows that when customers realize the severe consequences of conventional vehicles, they will feel a joint responsibility to prevent negative effects on the environment. In turn, personal norm, which is moral commitment to environmental protection, will be formed. As a result, they are motivated to form greater BEV purchase intention. These findings are also supported in the study of He and Zhan (Citation2018) and Asadi et al. (Citation2021).

When addressing the intention-behavior gap, previous studies usually focused on the moderating effect of external factors such as product price and availability (Buder et al., Citation2014; Ghali-Zinoubi, Citation2020). This study illustrates that personal innovativeness, which is an internal characteristic of customers, is a moderator of the intention–behavior relationship. In BEV adoption context, people who are more open towards new technology are more likely to turn their intention into actual purchase.

7. Conclusion and implications

This study examines BEV purchase decision of customers in Vietnam market. Based on the responses of 200 participants who are BEV drivers, this study concluded that BEV purchase decision is driven by both self-interested and pro-environmental factors. In particular, performance expectancy, effort expectancy and facilitating conditions are positive antecedents of purchase intention. Meanwhile, there is no significant impact of social influence on purchase intention. The effect of facilitating conditions on purchase behavior is also insignificant. In addition, the path from awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility to personal norm was confirmed. Consistent to previous theories, intention is a strong predictor of purchase behavior, and the intention–behavior relationship can be positively moderated by personal innovativeness.

7.1. Theoretical implications

This study enriches the current theoretical knowledge of BEV purchase decision. Such behavior represents an innovation adoption as well as a pro-environmental behavior; therefore, it requires a comprehensive theoretical framework to analyze. In general, the integration of the UTAUT and NAM models showed a good explanation power as the adjusted R2 value exceeded the threshold of 25% as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2017). Regarding the UTAUT’s variables, this study found supporting evidence for the positive impact of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and facilitating conditions on BEV purchase intention. However, different from the original UTAUT, which predicted the strongest effect of performance expectancy (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003), this study found that facilitating conditions exerted higher impact on purchase intention. This suggests that if innovations heavily rely on supporting infrastructure, such as in the case of BEVs, facilitating conditions are more important than the perceived benefits and user-friendliness. Furthermore, the availability of facilitating conditions serve as an input to form purchase intention rather than directly leading to actual behavior as proposed in the original UTAUT. Social influence might not show a significant effect in the early stage of innovation adoption as early customers mainly make individual decisions. In addition, this study also clarifies the altruistic perspective of BEV purchase decision. Customers form a moral obligation towards buying BEVs if they are aware of environmental problems and connect with their responsibility. Finally, this study proposed and verified the moderating effect of personal innovativeness, which contributes to bridging the intention-behavior gap.

7.2. Managerial implications

Based on the findings, this study offers several implications for policy makers and BEV manufacturers. First of all, the advantages of BEVs such as emissions reduction, fast acceleration and energy efficient should be stressed in marketing campaigns to convince rational decision makers. At the same time, it is necessary to invest in battery technology to enhance the range and shorten the charging time of BEVs. Secondly, the ease of use should be demonstrated to customers via free public trials or BEV experience centers. Thirdly, the public acceptance of BEVs is strongly affected by supporting infrastructure, thus it is essential to develop a wide network of maintenance facilities and charging stations for BEVs. In addition to placing new charging stations in cities and along highways, BEV manufacturers can integrate a navigating application in their driver-assistance systems to help customers locate nearby charging points. Fourthly, the damage caused by conventional vehicles to the environment and human health should be presented in marketing communication messages. As a result, customers will be aware of their responsibility and form moral obligation towards protecting the environment by favoring the use of BEV. Finally, personal innovativeness can bridge the gap between BEV purchase intention and behavior. Therefore, marketing effort should be directed to a small innovative group of customers instead of the mass audience.

7.3. Limitations and future research

The authors also acknowledge some limitations and potential research gaps in the future. Although the convenience sampling method allows the researchers to gather responses quickly, the result representativeness is limited. Additionally, the research scope was restricted in Vietnam market; therefore, cross-border studies should be carried out in the future to increase the generalizability of research findings. The impact of culture on customers’ purchase behavior will also be an interesting research topic. Finally, personal innovativeness is just one factor among various unknown moderators of the intention–behavior relationship. In the future, more research should be conducted to explore these moderators to expand the current knowledge of customer behavior.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interests

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20417871.v1

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackaah, W., Kanton, A. T., & Osei, K. K. (2021). Factors influencing consumers’ intentions to purchase electric vehicles in Ghana. Transportation Letters, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19427867.2021.1990828

- Adnan, N., Nordin, S. M., Rahman, I., & Rasli, A. M. (2017). A new era of sustainable transport: An experimental examination on forecasting adoption behavior of EVs among Malaysian consumer. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 103, 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.06.010

- Afroz, R., Masud, M. M., Akhtar, R., Islam, M. A., & Duasa, J. B. (2015). Consumer purchase intention towards environmentally friendly vehicles: An empirical investigation in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22(20), 16153–16163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4841-8

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Al-Swidi, A. K., & Faaeq, M. K. (2019). How robust is the UTAUT theory in explaining the usage intention of e-government services in an unstable security context?: A study in Iraq. Electronic Government, an International Journal, 15(1), 37–66. https://doi.org/10.1504/EG.2019.096580

- Anjam, M., Khan, H., Ahmed, S., & Thalassinos, E. I. (2020). The antecedents of consumer eco-friendly vehicles purchase behavior in United Arab emirates: The roles of perception, personality innovativeness and sustainability. International Journal of Economics & Management, 14(3), 343–363. http://www.ijem.upm.edu.my/vol14no3/3.%20The%20Antecedents%20of%20Consumer.pdf

- Arif, M., Ameen, K., & Rafiq, M. (2018). Factors affecting student use of Web-based services: Application of UTAUT in the Pakistani context. The Electronic Library, 36(3), 518–534. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-06-2016-0129

- Asadi, S., Nilashi, M., Samad, S., Abdullah, R., Mahmoud, M., Alkinani, M. H., & Yadegaridehkordi, E. (2021). Factors impacting consumers’ intention toward adoption of electric vehicles in Malaysia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 282, 124474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124474

- Awan, U. (2011). Green marketing: Marketing strategies for the Swedish energy companies. International Journal of Industrial Marketing, 1(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijim.v1i2.1008

- Berneiser, J., Senkpiel, C., Steingrube, A., & Gölz, S. (2021). The role of norms and collective efficacy for the importance of techno‐economic vehicle attributes in Germany. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(5), 1113–1128. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1919

- Buder, F., Feldmann, C., & Hamm, U. (2014). Why regular buyers of organic food still buy many conventional products: Product-specific purchase barriers for organic food consumers. British Food Journal, 116(3), 390–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2012-0087

- Carley, S., Siddiki, S., & Nicholson-Crotty, S. (2019). Evolution of plug-in electric vehicle demand: Assessing consumer perceptions and intent to purchase over time. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 70, 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.04.002

- Chen, C. F., de Rubens, G. Z., Noel, L., Kester, J., & Sovacool, B. K. (2020). Assessing the socio-demographic, technical, economic and behavioral factors of Nordic electric vehicle adoption and the influence of vehicle-to-grid preferences. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 121, 109692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109692

- Cohen, J. E. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum.

- Degirmenci, K., & Breitner, M. H. (2017). Consumer purchase intentions for electric vehicles: Is green more important than price and range? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 51, 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.01.001

- De Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2009). Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. The Journal of Social Psychology, 149(4), 425–449. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.4.425-449

- Dong, X., Zhang, B., Wang, B., & Wang, Z. (2020). Urban households’ purchase intentions for pure electric vehicles under subsidy contexts in China: Do cost factors matter? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 135, 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.03.012

- Du, H., Liu, D., Sovacool, B. K., Wang, Y., Ma, S., & Li, R. Y. M. (2018). Who buys new energy vehicles in China? Assessing social-psychological predictors of purchasing awareness, intention, and policy. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 58, 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.05.008

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Jeyaraj, A., Clement, M., & Williams, M. D. (2019). Re-examining the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Towards a revised theoretical model. Information Systems Frontiers, 21(3), 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9774-y

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley Publication Company.

- Ghali-Zinoubi, Z. (2020). Determinants of consumer purchase intention and behavior toward green product: The moderating role of price sensitivity. Archives of Business Research, 8(1), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.14738/abr.81.7429

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd) ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

- Hasan, S. (2021). Assessment of electric vehicle repurchase intention: A survey-based study on the Norwegian EV market. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 11, 100439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2021.100439

- Haustein, S., & Jensen, A. F. (2018). Factors of electric vehicle adoption: A comparison of conventional and electric car users based on an extended theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 12(7), 484–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2017.1398790

- Helmers, E., & Marx, P. (2012). Electric cars: Technical characteristics and environmental impacts. Environmental Sciences Europe, 24(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/2190-4715-24-14

- He, X., & Zhan, W. (2018). How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 3546–3556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.05.088

- Huang, X., & Ge, J. (2019). Electric vehicle development in Beijing: An analysis of consumer purchase intention. Journal of Cleaner Production, 216, 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.231

- International Energy Agency. (2021). Global energy review 2021. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/d0031107-401d-4a2f-a48b-9eed19457335/GlobalEnergyReview2021.pdf [ Accessed on 14/2/2022]

- Jain, N. K., Bhaskar, K., & Jain, S. (2022). What drives adoption intention of electric vehicles in India? An integrated UTAUT model with environmental concerns, perceived risk and government support. Research in Transportation Business & Management, 42, 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2021.100730

- Jiang, Q., Wei, W., Guan, X., & Yang, D. (2021). What increases consumers’ purchase intention of battery electric vehicles from Chinese electric vehicle start-ups? taking Nio as an example. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 12(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj12020071

- Jreige, M., Abou-Zeid, M., & Kaysi, I. (2021). Consumer preferences for hybrid and electric vehicles and deployment of the charging infrastructure: A case study of Lebanon. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 9(2), 466–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2021.02.002

- Kalthaus, M., & Sun, J. (2021). Determinants of electric vehicle diffusion in China. Environmental and Resource Economics, 80(3), 473–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00596-4

- Khazaei, H., & Tareq, M. A. (2021). Moderating effects of personal innovativeness and driving experience on factors influencing adoption of BEVs in Malaysia: An integrated SEM–BSEM approach. Heliyon, 7(9), e08072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08072

- Kim, J. H., Lee, G., Park, J. Y., Hong, J., & Park, J. (2019). Consumer intentions to purchase battery electric vehicles in Korea. Energy Policy, 132, 736–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.06.028

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kock, N., & Hadaya, P. (2016). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Information Systems Journal, 28(1), 227–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12131

- Krishnan, V. V., & Koshy, B. I. (2021). Evaluating the factors influencing purchase intention of electric vehicles in households owning conventional vehicles. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 9(3), 1122–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2021.05.013

- Lee, J., Baig, F., Talpur, M. A. H., & Shaikh, S. (2021). Public intentions to purchase electric vehicles in Pakistan. Sustainability, 13(10), 5523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105523

- Li, W., Long, R., Chen, H., Yang, T., Geng, J., & Yang, M. (2018). Effects of personal carbon trading on the decision to adopt battery electric vehicles: Analysis based on a choice experiment in Jiangsu, China. Applied Energy, 209, 478–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.10.119

- Liu, R., Ding, Z., Jiang, X., Sun, J., Jiang, Y., & Qiang, W. (2020). How does experience impact the adoption willingness of battery electric vehicles? The role of psychological factors. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(20), 25230–25247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08834-w

- Lu, T., Yao, E., Jin, F., & Pan, L. (2020). Alternative incentive policies against purchase subsidy decrease for battery electric vehicle (BEV) adoption. Energies, 13(7), 1645. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13071645

- Malhotra, N. (2009). Marketing research: An applied orientation (6th edition). Pearson.

- Moghavvemi, S., Salleh, N. A. M., Sulaiman, A., & Abessi, M. (2015). Effect of external factors on intention–behaviour gap. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34(12), 1171–1185. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2015.1055801

- Nazari, F., Rahimi, E., & Mohammadian, A. K. (2019). Simultaneous estimation of battery electric vehicle adoption with endogenous willingness to pay. ETransportation, 1, 100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etran.2019.100008

- Nguyen, T. K. (2022). Vietnam’s VinFast pledges to ditch gas-powered cars in a year, Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-05/vietnam-s-vinfast-pledges-to-ditch-gas-powered-cars-in-a-year [ Accessed on 15/2/2022]

- Noel, L., de Rubens, G. Z., Kester, J., & Sovacool, B. K. (2020). Understanding the socio-technical nexus of Nordic electric vehicle (EV) barriers: A qualitative discussion of range, price, charging and knowledge. Energy Policy, 138, 111292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111292

- Pradeep, V. H., Amshala, V. T., & Kadali, B. R. (2021). Does perceived technology and knowledge of maintenance influence purchase intention of BEVs. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 93, 102759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2021.102759

- The Prime Minister. (2014). Decision No. 1168/QĐ-TTg dated 2014 – Approval for strategy to develop automotive industry in Viet Nam by 2025, orientation toward 2035. https://vanban.chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=174938 [ Accessed on 15/2/2022]

- Rahi, S., Ghani, M., Alnaser, F., & Ngah, A. (2018). Investigating the role of unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) in internet banking adoption context. Management Science Letters, 8(3), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2018.1.001

- Rezvani, Z., Jansson, J., & Bengtsson, M. (2018). Consumer motivations for sustainable consumption: The interaction of gain, normative and hedonic motivations on electric vehicle adoption. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1272–1283. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2074

- Rezvani, Z., Jansson, J., & Bodin, J. (2015). Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agenda. Transportation research part D: Transport and environment. 34, 122–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2014.10.010

- Rogers, E. M. (2010). Diffusion of innovations (4th) ed.). The Free Press.

- Ronaghi, M. H., & Forouharfar, A. (2020). A contextualized study of the usage of the internet of things (IoTs) in smart farming in a typical middle eastern country within the context of unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model (UTAUT). Technology in Society, 63, 101415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101415

- Samaradiwakara, G. D. M. N., & Gunawardena, C. G. (2014). Comparison of existing technology acceptance theories and models to suggest a well improved theory/model. International Technical Sciences Journal, 1(1), 21–36. http://elpjournal.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/itsj-spec-1-1-3.pdf

- Sang, Y. N., & Bekhet, H. A. (2015). Modelling electric vehicle usage intentions: An empirical study in Malaysia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 92, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.045

- Ščasný, M., Zvěřinová, I., & Czajkowski, M. (2018). Electric, plug-in hybrid, hybrid, or conventional? Polish consumers’ preferences for electric vehicles. Energy Efficiency, 11(8), 2181–2201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-018-9754-1

- Schmalfuß, F., Mühl, K., & Krems, J. F. (2017). Direct experience with battery electric vehicles (BEVs) matters when evaluating vehicle attributes, attitude and purchase intention. transportation research part F: Traffic psychology and behaviour. 46, 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2017.01.004

- Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences on altruism. In Berkowitz L. (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 221–279). Academic Press.

- Shalender, K., & Sharma, N. (2021). Using extended theory of planned behaviour (TPB) to predict adoption intention of electric vehicles in India. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(1), 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00602-7

- She, Z. Y., Sun, Q., Ma, J. J., & Xie, B. C. (2017). What are the barriers to widespread adoption of battery electric vehicles? A survey of public perception in Tianjin, China. Transport Policy, 56, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.03.001

- Skippon, S. M. (2014). How consumer drivers construe vehicle performance: Implications for electric vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 23, 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2013.12.008

- Statista. (2020). Distribution of carbon dioxide emissions produced by the transportation sectors worldwide in 2020, by sector. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1185535/transport-carbon-dioxide-emissions-breakdown/ [ Accessed on 14/2/2022]

- Van Heuveln, K., Ghotge, R., Annema, J. A., van Bergen, E., van Wee, B., & Pesch, U. (2021). Factors influencing consumer acceptance of vehicle-to-grid by electric vehicle drivers in the Netherlands. Travel Behaviour and Society, 24, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2020.12.008

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS quarterly, 425–478 https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

- Wang, X. W., Cao, Y. M., & Zhang, N. (2021). The influences of incentive policy perceptions and consumer social attributes on battery electric vehicle purchase intentions. Energy Policy, 151, 112163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112163

- Westin, K., Jansson, J., & Nordlund, A. (2018). The importance of socio-demographic characteristics, geographic setting, and attitudes for adoption of electric vehicles in Sweden. Travel Behaviour and Society, 13, 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2018.07.004

- Xu, Y., Zhang, W., Bao, H., Zhang, S., & Xiang, Y. (2019). A SEM–neural network approach to predict customers’ intention to purchase battery electric vehicles in China’s Zhejiang province. Sustainability, 11(11), 3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113164

- Yang, J., & Chen, F. (2021). How are social-psychological factors related to consumer preferences for plug-in electric vehicles? Case studies from two cities in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 149, 111325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111325

- Zhou, M., Long, P., Kong, N., Zhao, L., Jia, F., & Campy, K. S. (2021). Characterizing the motivational mechanism behind taxi driver’s adoption of electric vehicles for living: Insights from China. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 144, 134–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2021.01.002

Appendix

Table A1. Measurement items used in the study