Abstract

The OPEC countries rely on oil to fund their budgets, similar to many countries worldwide. However, the fall in oil prices in 2008 and 2014 put significant strain on their public finances, including healthcare finances. This study examines the effect of the fall in oil prices on OPEC countries’ healthcare spending and whether the burden has shifted from government to private spending. The government and private healthcare spending after 2008 and after 2014 were compared to spending before 2008. Moreover, Welch’s t-test was used to assess the difference between healthcare spending in the stated periods. The study found that the majority of OPEC countries decreased government healthcare spending after 2008 and after 2014, indicating that the burden shifted from governments to private spending. The study suggests that countries should minimize reliance on oil, diversify their income, and avoid relying heavily on debt and foreign reserves, as these might negatively impact healthcare spending in the future.

Public interest statement

This paper examines the outcome of the effect of changing oil prices on healthcare spending in oil-exporting economics, particularly OPEC countries. This study has used a t-test to show that the proportion of government spending on healthcare to total spending on healthcare in the sample countries has decreased during 2009 to 2013 and during 2015 to 2019 due to oil prices shock as compared to the situation in 2003 to 2007. At the same time, the burden of healthcare spending has shifted into private spending and specifically to individuals, since the majority of the private spending in the investigated countries is based on OOP, argues that oil-dependent economies may have to reevaluate its social welfare programmers in response to global commodity prices.

Introduction

Governments of numerous countries rely on oil to finance their budgets, whether through direct revenues from country-owned oil companies, taxing oil companies, or taxing consumption. In 2018, 24 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) governments taxed petroleum fuel at $2 per gallon, where 10 of them taxed nearly $3 OECD OfECaD (Citation2022). Most of these were European countries with the highest fuel taxes globally OECD OfECaD (Citation2022). In 2019, revenues from oil exports accounted for a minimum of 4% of the GDPs of 25 countries worldwide, with nine of them exceeding 20% The Global Economy (Citation2019). However, in the absence of a sustainable alternative to oil, government financing might be affected by oil price fluctuations.

The global financial crisis that began in 2007 caused severe pressure on economies worldwide to slow economic activities and lower demand for energy Lindström and Giordano, GNJSS, Medicine (Citation2016),Keegan et al. (Citation2013). As a result, oil prices plunged by 75%, from $140 per barrel in July 2008 to as low as $35 in December 2008 OPEC OotPEC (Citation2022). A similar fall in oil prices occurred in 2014, primarily due to oil oversupply, notably from the US and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), besides lower demand, particularly from China and Europe Mead and Stiger (Citation2015), to decrease prices by 52% from $108 in July 2014, to $52 in December 2014. Both circumstances put the public finances of many individual countries under significant strain, such as the OPEC countries, the United States, Canada, Russia, and other countries Bajpai (Citation2022),Statista, Citation2022a).

The OPEC was founded in 1960 with a mission to coordinate and unify the petroleum policies of its members and ensure the stability of the oil market Kisswani et al. (Citation2022). The level of oil production by OPEC members is subject to regulations, where each member is limited to a specific production level, and increases or decreases are based on developments in the market to secure an efficient, economic, and regular supply to consumers Kisswani et al. (Citation2022). Since its foundation, 16 members have joined the organization at different periods; some have suspended their membership for some time or withdrew their membership. At the time of writing and conducting this study, 13 are still members of the organization OPEC OotPEC. OPEC Member Countries (Citation2022).

From 2009-2013, the period after the 2008 fall in oil prices (hereafter referred to as “post-2008”), OPEC countries’ average revenue from oil exports ranged between 12% (min Nigeria and Ecuador) and 50% (max Libya and Kuwait) of their GDPs The Global Economy (Citation2019). Their average level of production also ranged between 0.5 (min Ecuador) and 9.0 (max Saudi Arabia (SA)) million barrels in the same period (see Table ) OPEC OotPEC (Citation2017),OPEC OotPEC (Citation2013),OPEC OotPEC (Citation2020). The OPEC countries’ dependence on oil from 2015-2019, after the fall in oil prices in 2014 (hereafter referred to as “post-2014”) was also high. Nevertheless, it was at a lower level compared to post-2008. For example, OPEC countries’ average revenue from oil exports ranged between 5% (min Nigeria and Ecuador) and 38% (max Kuwait) of their GDPs The Global Economy (Citation2019), and the average level of production ranged between 0.5 (min Ecuador) and 10.1 (max SA) million barrels OPEC OotPEC (Citation2017),OPEC OotPEC (Citation2013),OPEC OotPEC (Citation2020).

Table 1. OPEC dependency on oil and the effect of the drop in oil prices

The reliance on oil caused immediate budget deficits in many OPEC governments’ budgets in 2008 and 2014 due to the fall in oil prices, specifically in Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, and Angola (see Table ) Country Economy (Citation2022),The World Bank (Citation2022). The effect was higher one year later (2009 and 2015), where the deficit in 2009 reached 13% in Iraq, 8% in Venezuela and Angola, and more than 15% in SA and Algeria in 2015 vis-à-vis their GDPs. The Libyan government had the highest deficit in 2014 and 2015, with percentages reaching 72% and 80%, however, that may also be because of political instability Country Economy (Citation2022). The level of impact and timing were not homogenous across OPEC countries, as shown in Table . The aforecited Table details the effect level and timing in addition to countries’ reliance on oil.

While previous studies indicated the effect of the oil price shocks on economic growth, public spending, and public policy in oil-dependent economies Martínez (Citation2022),Charfeddine and Barkat (Citation2020),A. J. Ali (Citation2021), the literature still lacks studies on the effect of oil price shocks on healthcare spending and who incurs the spending burdens. A probing of the literature reveals more focus on the period of the 2008 financial crisis and its indirect consequences on health outcomes. For example, some studies investigated the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on health coverage, such as the effect on home care and the increase in specific health aspects, such as the incidence of mental health disorders. However, no indication to government and private spending was highlighted Barr et al. (Citation2012),Burke et al. (Citation2014). Another study investigated different healthcare spending variables, such as the healthcare spending to total government expenditure and government healthcare spending to GDP, but the study directed the investigation to some types of mortality indicators rather than the entire healthcare system Budhdeo et al. (Citation2015). Another study focused on pharmaceuticals Alba et al. (Citation2019), whereas other studies focused on spending in relation to health outcomes Edney et al. (Citation2018),Singh (Citation2014). A systematic review study that included more than 120 papers investigated the effect of the 2008 financial crisis on healthcare, where there was a lack of input in regards to the impact on government and private healthcare spending, with a special focus on mental health, suicide, some communicable and non-communicable diseases, and access to healthcare Karanikolos et al. (Citation2016). Similarly, another study investigated the unmet healthcare needs post the 2008 financial crisis; however, the study did not highlight if there is an effect resulting from any changes to the government or private healthcare spending at large Pappa et al. (Citation2013). Another study investigated the effect among non-oil-dependent countries (a group of European countries that received financial bailout) with no inputs in regard to the oil price shocks Loughnane et al. (Citation2019). More recent studies investigated healthcare spending. However, such studies focused not on oil price shocks but more on the effect and affordability of private healthcare spending Johnston et al. (Citation2019),Keane et al. (Citation2021). Therefore, this study aims to contribute to the literature by investigating whether healthcare spending has been affected by the 2008 and 2014 fall in oil prices and whether the impact has shifted the burden of healthcare spending from government to private spending.

The financing process of the healthcare system in OPEC countries differs. For example, the Algerian healthcare system provides free healthcare services for all citizens in the country, where the majority of the finances are derived from the government (>50% during the study period) Scherer et al. (Citation2018),Financial (Citation2022). In Nigeria, the healthcare system is financed through different sources, but predominantly through out-of-pocket (OOP) payments, which accounts for 70% of total healthcare spending, putting the system in a critical situation to meet the demand for healthcare Uzochukwu et al. (Citation2015). Moreover, healthcare system financing in Venezuela is fragmented with private and public funding Atun et al. (Citation2015), but tends to be more private with a growing share of OOP payments, which is one of the highest in the world Roa (Citation2018). The system lacks adequate medicines, and adequate access to healthcare has been jeopardized due to a lack of resources Fowler (Citation2017). In Iran, the healthcare system is financed via public funds, social healthcare insurance, private insurance, OOP, and government support through public revenue Dizaj et al. (Citation2019), Zare et al. (Citation2014). Most of the system was financed privately, and OOP often financed over 50% of the total healthcare spending World Health Organization (Citation2022), Zakeri et al. (Citation2015). In Iraq, the constitution obliges the government to ensure a universal right to healthcare for the population, in which the public sector offers free services to citizens, primarily financed through oil revenues Jaff et al. (Citation2018). The private sector supplements the public sector, especially in curative care Al Hilfi et al. (Citation2013). In Kuwait, the healthcare system provides free healthcare services to citizens, financed by the government Alkhamis et al. (Citation2014), Khoja et al. (Citation2017), with private spending predominantly financed through OOP World Health Organization (Citation2022), Alkhamis et al. (Citation2014). The Saudi healthcare system provides free public healthcare services to all Saudis and non-Saudis employed publicly, including their dependents, financed by the government budget. The system also provides free services through the private sector to cover privately employed people and their dependents, financed by their employers Al Mustanyir et al. (Citation2022). In the UAE, services are provided by public and privately owned facilities, and the government mainly finances the system. Private insurance covers health services more in the emirates of Abu Dhabi and Dubai, where most services are delivered in private facilities, while the other five emirates are served by the Ministry of Health Koornneef et al. (Citation2017), Andersen (Citation2013).

Methodology

To serve the purpose of this study, government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare was selected as the primary indicator for analysis, and private healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare was selected as the secondary indicator. The evaluation metrics were selected based on their capacity to demonstrate the effects of the fall in oil prices in 2008 and 2014 on healthcare spending and whether the distribution of spending shifted from government to private spending. The analysis performed in this study used aggregate spending on healthcare as opposed to absolute values typically used for specific countries or diseases Zhang et al. (Citation2010), Turner (Citation2017). However, it is worth mentioning that aggregates are appropriate when undertaking comparisons across countries as they permit the investigation of different explanatory variables and institutional systems Gerdtham and Jönsson (Citation2000). Given that this study compares healthcare spending across countries, aggregates are appropriate and can reveal relevant changes in the proportion of government and private healthcare spending, even if the absolute values remain unchanged. Study data were extracted from the World Health Organization (WHO) global health expenditure database World Health Organization (Citation2022).

With the spread of the effect of the fall in oil prices in 2008 and 2014, the years 2009 and 2015 were chosen as the turning points. The data were categorized into three groups for statistical comparison, i) the period from 2003 to 2007 was categorized as the pre-fall in oil prices (hereafter referred to as “pre-2008”), ii) post-2008, and iii) post-2014. Since the study aims to investigate the effect on healthcare spending after a fall in oil prices, 2008 and 2014 were excluded. Essentially, 2008 and 2014 were excluded because the effect is usually observed in the year after the fall in prices. It is likely that only half of 2008 and 2014 were affected since the fall in prices began in July 2008 and 2014. Accordingly, this is implemented to avoid bias in the data categories.

Descriptive analysis was used to analyze the mean changes in healthcare spending after 2008 and 2014 with spending before 2008. The study also employed a comparison of means using Welch’s t-test to assess the difference between healthcare spending in the aforementioned periods. Welch’s t-test is appropriate for measuring the mean changes of the two independent groups, especially if a small sample size was involved (short periods of comparison) Delacre et al. (Citation2017). A two-sided t-test was used, and the results were indicated with significance levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%. The test was used to measure the significance of the difference between the means Burke et al. (Citation2014). The comparison of the means calculates the difference between the observed means in two independent samples. The significance value (p-value) of the difference is reported. The p-value is the probability of obtaining the observed difference between samples if the null hypothesis is true. The null hypothesis was that the difference was 0. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software version 14.0.

Since this study investigates the effect of the fall in oil prices on countries’ healthcare spending and whether the spending was moved from government to private spending, it is crucial to control the bias generated from government overspending on healthcare resulting from the overproduction of oil. This phenomenon might yield more collected taxes or increase revenue from government-owned oil companies –as many producers are independent in their decisions about oil production– Kisswani et al. (Citation2022), which is why it should be controlled for better analysis. Hence, OPEC countries were chosen as the study sample. In addition, to ensure best practice, the countries included in the study were those with OPEC membership during the entire study (2003-2019). Therefore, eight OPEC countries were included: Algeria, Nigeria, Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, SA, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Libya held its membership during the study period; however, it was excluded because no healthcare spending data for the country has been available since 2012 World Health Organization (Citation2022).

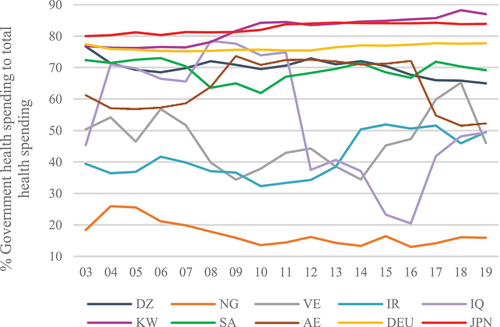

Further descriptive analysis was conducted on more variables to analyze the trend of healthcare spending post-2008 and post-2014 compared to the pre-2008 Haralayya (Citation2021). The analysis involved the mean change in government and private healthcare spending and the mean change in government and private healthcare spending to the GDP, which were compared to the study primary and secondary indicators to identify any difference in healthcare spending patterns. Moreover, to analyze the government healthcare spending dynamic in oil-dependent and non-oil dependent economies, the government healthcare spending to total healthcare spending was assessed for the entire study period (2003-2019) in OPEC countries in addition to Germany and Japan, which are two of the least oil producing countries Crude Oil Production (Citation2022).

Results

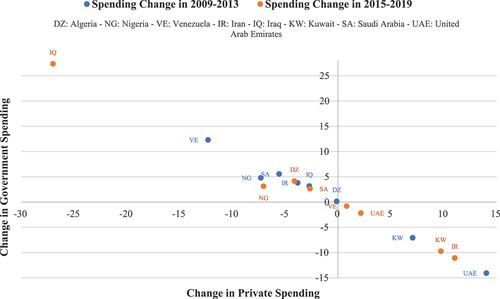

The comparison of mean changes in this study indicates that government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare in post-2008 Algeria declined relatively compared to pre-2008 by 0.12% (p = 0.93) but decreased significantly in post-2014 with a mean decline of 4.12% (p = 0.04) (see Figure and Table ). Concurrently, the mean change in private healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare increased post-2008 by 0.15% (p = 0.92), and increased significantly by 4.15% post-2014 (p = 0.04).

Figure 1. Change in government and private spending on healthcare as a % of total spending on healthcare for the periods 2009-2013 and 2015-2019 compared to 2003-2007.

Table 2. Welch’s t-test results for changes in healthcare spending in 2009–2013 and 2015–2019 compared to 2003–2007

In Nigeria, the mean change in government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare post-2008 decreased significantly relative to pre-2008 by 7.3% (p = 0.00) and decreased significantly by 7.05% post-2014 (p = 0.00). Simultaneously, the mean change in private healthcare spending increased significantly by 4.8% post-2008 (p = 0.03) and increased by 3.14% post-2014 (p = 0.14).

In Venezuela, the mean change in government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare declined significantly post-2008 relative to pre-2008 by 12.3% (p = 0.00) and increased relatively post-2014 by 0.82% (p = 0.85). Meanwhile, in the same period, the mean change in private healthcare spending increased significantly post-2008 by 12.32% (p = 0.00) and decreased relatively post-2014 by -0.80% (p = 0.86).

In Iran, the mean change in government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare decreased significantly post-2008 by 3.81% (p = 0.03) and increased significantly post-2014 by 11.06% (p = 0.00). In the same period, the mean change in private healthcare spending increased significantly post-2008 by 3.81% (p = 0.03) and decreased significantly post-2014 by 11.07% (p = 0.00).

In Iraq, the mean change in government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare decreased by 2.71% post-2008 (p = 0.79) and significantly decreased post-2014 by 27% (p = 0.00). Concurrently, the mean change in private healthcare spending increased by 3.17 post-2008 (p = 0.75) and increased significantly post-2014 by 27.4% (p = 0.00).

In Kuwait, the mean change in government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare increased significantly post-2008 by 7.07% (p = 0.00) and increased at higher levels post-2014 to 9.74% (p = 0.00). Further, the mean change in private healthcare spending decreased significantly post-2008 by 7.07% (p = 0.00) and decreased significantly by 9.74% post-2014 (p = 0.00).

In SA, the mean change in government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare declined significantly post-2008 by 5.57% (p = 0.00) and declined significantly by 2.64% (p = 0.02) post-2014. Meanwhile, in the same period, the mean change in private healthcare spending increased significantly post-2008 by 5.57% (p = 0.00) and increased significantly by 2.64% post-2014 (p = 0.02).

In the UAE, the mean change in government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare increased significantly by 14.05% post-2008 (p = 0.00) and increased by 2.17% post-2014 (p = 0.65). Moreover, the mean change in private healthcare spending decreased significantly by 14.05% post-2008 (p = 0.00) and decreased by 2.17 post-2014 (p = 0.65) (see Figure and Table ).

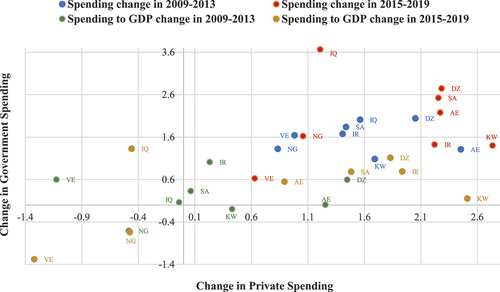

For the study’s other variables, the comparison of mean changes in government and private healthcare spending reflected the same trend in all countries involved in the study as the mean changes in government and private healthcare spending to total healthcare spending. For example, the mean change in private healthcare spending increased at a higher rate compared to the mean change in government healthcare spending in Iraq, Nigeria, SA, and Algeria in both comparison periods (post-2008 and post-2014) and in Venezuela and Iran post-2008. In addition, the mean change in government healthcare spending increased at a higher rate compared to the mean change in private healthcare spending in Kuwait and UAE in both periods and Iran and Venezuela post-2014 (see Figure ).

Figure 2. Change in government and private healthcare spending and change in government and private healthcare spending to GDP for the periods 2009-2013 and 2015-2019 compared to 2003-2007.

The mean changes in government and private healthcare spending to GDP showed the same trend as the mean changes in government and private healthcare spending to total healthcare spending in all the study countries (except Algeria and Nigeria post-2008 and post-2014, also SA and Venezuela post-2014). For example, the mean change in government healthcare spending to GDP in Kuwait and UAE in both periods (post-2008 and post-2014) increased at a higher rate compared to the mean change in private healthcare spending to GDP and in Iran post-2014. Moreover, the mean change in private healthcare spending to GDP increased at a higher rate in Iraq compared to the mean change in government healthcare spending to GDP in both periods and in Venezuela, Iran, and SA post-2008 (see Figure ). The study results also showed high fluctuations in government healthcare spending to total healthcare spending in all oil-dependent countries, compared to more stability in non-oil-dependent countries through the period from 2003 to 2019. The data showed 2% and 4% changes in government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare within this period in Germany and Japan (respectively). However, the fluctuations hit a maximum of nearly 60% and a minimum of 11% in the eight OPEC countries involved in this study (see Figure ).

Discussion

Throughout the fall in oil prices following 2008 and 2014, the majority of OPEC countries in this study experienced a decline in government healthcare spending (as shown in the northwest quadrant of Figure ). The analysis reveals that the fall in oil prices affected the spending levels of countries to varying degrees. Venezuela appeared to have experienced the greatest reduction in government healthcare spending relative to total healthcare spending after 2008, followed by Iraq after 2014. Algeria and Iraq post-2008 and Venezuela and UAE post-2014 experienced the smallest increase and decrease in healthcare spending, with no statistically significant change (see Table ).

The study results suggest that post-2008, the burden distribution of healthcare spending may have shifted from the government to private spending in all countries under investigation, except Kuwait and the UAE. In post-2014, approximately half of OPEC was adversely affected, namely Algeria, Nigeria, Iraq, and SA. The results also suggest that these four countries may have shifted the burden distribution of healthcare spending to private spending in both periods after the fall in oil prices, with a notable shift in Nigeria. Private healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare declined in Kuwait and the UAE after 2008 and in Venezuela, Iran, Kuwait, and the UAE after 2014, indicating that the burden distribution of healthcare spending moved to governments.

The literature stated that the fall in oil prices affects public spending AJ. Ali (Citation2021), and that it may hinder healthcare development C. W. Su et al. (Citation2020). Moreover, with the continuous increases in healthcare spending due to population growth and aging Dieleman et al. (Citation2017), it was evident that many OPEC countries were urged to increase the share of government healthcare spending to government total expenditure to maintain their levels of healthcare. However, many of the investigated countries failed to secure sufficient increases in their government healthcare spending given that some of them relied heavily on debt to report budget deficits and so, the healthcare spending burden has shifted to private spending. For example, the Algerian government barely maintained its healthcare spending proportion to total healthcare spending at 71% on average post-2008. It actually declined significantly to 67% post-2014, given that the government incurred high budget deficits of up to 5% of GDP post-2008 and up to 15% post-2014 in order to increase its spending on healthcare as a percentage of government total expenditure from 8.2% pre-2008 to 10% post-2008 and 10.7% post-2014 on average World Health Organization (Citation2022),Trading Economics, Citation2022a),Trading Economics, Citation2022b), making private spending cover the shortage. Iraq could not achieve this either with influence by war and economic sanctions Al Hilfi et al. (Citation2013),Lafta and Al-Nuaimi (Citation2019). The government budget incurred deficits of more than 12% of GDP post-2008 and more than 15% post-2014 to increase government healthcare spending to total government expenditure from 3% pre-2008 to 3.9% post-2008 and 4.1% post-2014, on average World Health Organization (Citation2022),Trading Economics, Citation2022c). That in fact, did not help, to report a decline in government healthcare spending to total healthcare spending from 63.6% pre-2008 to 60.9% post-2008 on average and down to 36.6% post-2014. Saudi Arabia, with its leading economic indicators, could not increase their government healthcare spending to total healthcare spending, and struggled to retain the same level of financing post-2014 as pre-2008. The share of government healthcare spending to total spending on healthcare in Saudi Arabia decreased from 71.9% pre-2008 to 66.4% post-2008, on average, responding to the decrease in government healthcare spending as a percentage of total government expenditure from 8.8% to 7.8% in the same periods. However, with the notable increase in this percentage to 11% post-2014, the government healthcare spending to total healthcare spending increased to just 69.3%.

Other countries could not maintain their level of government healthcare spending due to instability and poor economic reforms to shift the healthcare spending burden to private spending Akinwale (Citation2018),Americas Quarterly (Citation2022),Ikeanyibe (Citation2016). For example, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government expenditure in Nigeria decreased to the low levels of 3.3% post-2008 and 4.5% post-2014 compared to 5.7% pre-2008, on average World Health Organization (Citation2022), which has been attributed to a dwindling economy Otu (Citation2018). This lowered the government spending proportion to total spending on healthcare from 22.2% pre-2008 to 15% post-2014, on average. Such that worsen the healthcare situation and prevail poor healthcare indices, which recorded one of the lowest indices in Africa Otu (Citation2018),Odunyemi (Citation2021). In Venezuela, the government has tried to increase its spending on healthcare Atun et al. (Citation2015), causing the government debt to rise to unprecedented levels (from a maximum of 30% post-2008 to 233% post-2014 of GDP) Trading Economics, Citation2022d),Trading Economics, Citation2022e), and the budget deficit to levels between 11% and 30% of GDP in the corresponding periods. However, the government healthcare spending to total government expenditure decreased from 11% pre-2008 to 7% post-2008 and 7.7% post-2014, on average, which worsened the healthcare situation Fowler (Citation2017). The government spending proportion post-2008 decreased to 39.6% compared to 51.9% pre-2008, on average, and returned to 52.7% post-2014, although that is still low due to the significant decrease in government healthcare spending to government total expenditure. Indeed, these poor indicators are accompanied by hyperinflation, which reduced people’s private access to healthcare, since the majority of the private spending is based on OOP payments Statista, Citation2022b),Pittaluga et al. (Citation2021). In Iran, the healthcare system still suffers a lack of sustainable resources and struggles with increases in private healthcare spending in proportion to total spending Harirchi et al. (Citation2020). During the period of investigation, studies found that nearly 20% of the population has no healthcare coverage. As the government increased its healthcare spending to total government expenditure from 10.1% pre-2008 to 13.8% post-2008, on average, the government healthcare proportion to total healthcare spending declined from 38.8% to 35% on average in the corresponding periods due to the high private spending post-2008 Harirchi et al. (Citation2020), to profound individuals struggles. In the period post-2014, the government increased healthcare spending by 22.6% on average to total government expenditure to alleviate the strain on individuals. Although private spending is still high in Iran, representing half the healthcare spending or more. Some studies indicated that the public and private proportions of total spending on healthcare in Iran are far from equity Zare et al. (Citation2014),Zakeri et al. (Citation2015).

Some countries showed resilience to the fall in oil prices in the study periods, but with more strains on their government finance policy. For example, Kuwait showed a significant decline in foreign reserves after 2008 and 2014 to increase the government healthcare spending from 76.5% pre-2008 to 83.5% post-2008 and 86.2% post-2014 to total healthcare spending Trading Economics, Citation2022f). Moreover, Kuwait may be different from other countries due to having the smallest population compared to the other countries involved in the study and being the fourth highest oil producer among OPEC countries Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD (Citation2022),Statista, Citation2022c). In addition, the UAE post-2008 reported budget deficits to increase government healthcare spending to government total expenditure from 8.3% pre-2008 to 8.5% post-2008, on average Trading Economics, Citation2022g). The budget deficit continued post-2014, although the government healthcare spending to government total expenditure decreased to 7.6%. With such levels of deficits, and the reported debt, which increased up to 22% post-2008 and 27% post-2014 of GDP Trading Economics, Citation2022h), the government healthcare spending to total spending post-2008 increased on average but returned to roughly the same proportion as pre-2008.

The result of this study revealed that oil should not be used as an ultimate source of funding for countries, as the high and continuous reliance on such a source of funding could risk the stability of their economies. This is attributed to oil’s high sensitivity to global market changes Onour and Abdo (Citation2022), which was experienced at different times historically Bayati and Bin Al-Hamid (Citation2022). The literature also indicated that oil increased economic policy uncertainty Qin et al. (Citation2020). Recently, with the market having just recovered in 2018 and 2019 Loughnane et al. (Citation2019), the COVID-19 pandemic caused another market disturbance, causing oil to plummet to unprecedented levels since the 1990s (Macrotrends, Citation2022). In addition, the outbreak of war in Ukraine exacerbated the economic situation, which took oil prices in another direction with high fluctuations Onour and Abdo (Citation2022). With the future continuous uncertainty, and the world moving to reduce carbon emissions and invest more in green energy to control threats posed to human society C.W. Su et al. (Citation2022), oil-dependent economies should take measures to free their economies from dependence on the such source of funding to ensure stability to their healthcare spending and reduce pressure on individuals and the government financing policy.

When more analysis was performed on different variables; for example, the mean change in government and private healthcare spending in addition to the mean change in government and private healthcare spending to GDP, to analyze the trend of the healthcare spending post-2008 and post-2014 with pre-2008, broadly similar results were found to those shown by the mean change in government and private healthcare spending to total healthcare spending (see Figure ). This emphasizes the study findings which suggest that the fall in oil prices has shifted the burden distribution of healthcare spending from the governments to private spending in most of the countries under investigation. Moreover, when the government healthcare spending to total healthcare spending in OPEC countries was investigated in addition to Germany and Japan over the period from 2003 to 2019, the instability of government healthcare spending in OPEC countries was clearly seen. This instability was due to their high reliance on oil for financing their healthcare as non-oil-dependent economies had stable healthcare spending in the same period.

Conclusion

This study examined the effect of a fall in oil prices on OPEC countries’ healthcare spending. It was observed that the effect was inevitable to all but in varying degrees. It was also evident in the study that the majority of these oil-dependent countries struggled to maintain their levels of government healthcare spending post-2008 and post-2014 as compared to the pre-2008 context due to the lack of sustainable alternative sources of public revenues and investments. Consequently, the healthcare spending burden shifted to private spending, specifically to individuals, since many countries fund most of the private spending via OOP. With the countries’ attempts to prevent the effect, they reported significant budget deficits, relied on their foreign reserves, and increased debt levels. However, the majority failed to shield private healthcare spending against the effect of the fall in oil prices. In contrast, non-oil-dependent countries showed high resilience to oil price shocks, where government healthcare spending maintained nearly the same percentage for almost two decades. The reduction in government healthcare spending might have alleviated the pressure temporarily on governments. However, that could have long-term adverse consequences. The short-sighted nature of decreasing government healthcare spending to control public finances will likely worsen healthcare outcomes and increase healthcare needs over time unless such patterns are reversed. In addition, the continuous economic instability caused by COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine could put the government healthcare spending of oil-dependent economies under more strain and cause the economies to face newer challenges, as healthcare systems might face increased demand for healthcare due to population growth, aging, and an increase in the number of people with chronic diseases, which would require more healthcare spending. The results of this study suggest that countries that rely on oil to finance their healthcare services, whether through direct exports’ revenues or through taxing consumption, minimize the reliance on such sources of income due to their high volatility, which might maintain the instability in government healthcare spending, as well as to diversify their healthcare finance resources. In addition, countries should not focus on short-term solutions, such as decreasing government spending or shifting the burden to private spending. Finally, governments must be prudent with their spending, as relying on debt or foreign reserves might negatively affect healthcare spending and the countries’ financing policy in the long term, especially if a similar fall in oil prices occurs in the future.

Highlights

The fall in oil prices in 2008 and 2014 put the OPEC countries’ public finances under significant strain.

The effect of the fall in oil prices on OPEC countries’ healthcare spending and whether the burden shifted from government to private spending were examined.

The effect was inevitable to the majority of OPEC countries albeit in varying degrees.

Healthcare spending shifted to private spending, and specifically, to individuals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Salem Al Mustanyir

Salem Al Mustanyir is a senior economist and head of strategic studies at Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority (SDAIA) and has experience working in different universities in Saudi Arabia and abroad and private companies in departments of accounting, finance, investment, insurance, and risk management. Dr. Salem’s research activities lie in building public and private performance indices (e.g., education, healthcare, population, labor, commerce and finance, infrastructure, environment sustainability, and social equalization), conducting policy impact assessment studies, health economics and financing, labor market, energy, education outcomes and market needs, smart cities, economic of data, and investment in artificial intelligence.

References

- Akinwale, S. O. (2018). Analysis of financial sector reforms on economic growth in Nigeria. European Journal of Business Economics and Accountancy, 6(4), 1–15. http://www.idpublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Full-Paper-ANALYSIS-OF-FINANCIAL-SECTOR-REFORMS-ON-ECONOMIC-GROWTH-IN-NIGERIA.pdf

- Alba, F. F., Soler, N. G., Reyes, A. M., & García Ruiz, A. J. (2019). Crisis, public spending on health and policy. Revista Espanola de Salud Publica, 93, e201902007. https://europepmc.org/article/med/30783077

- Al Hilfi, T. K., Lafta, R., & Burnham, G. (2013). Health services in Iraq. The Lancet, 381(9870), 939–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60320-7

- Ali, A. J. (2021). Do oil prices govern GDP and public spending avenues in Saudi Arabia?. Sensitivity and trend analysis, 11(2), 104–109. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.10791

- Ali, A. J. (2021). Volatility of oil prices and public spending in Saudi Arabia: sensitivity and trend analysis. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 670216917. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.10601

- Alkhamis, A., Hassan, A., & Cosgrove, P. (2014). Financing healthcare in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: a focus on Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 29(1), e64–e82. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2213

- Al Mustanyir, S., Turner, B., & Mulcahy, M. (2022). The population of Saudi Arabia’s willingness to pay for improved level of access to healthcare services: A contingent valuation study. Health Science, 5(3), e577. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.577

- Americas Quarterly. Venezuela’s Ad Hoc Economic Recovery Is Not Yet Sustainable. Americas Quarterly. ( Accessed 14 October 2022). https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/venezuelas-ad-hoc-economic-recovery-is-not-yet-sustainable/

- Andersen, B. J. (2013). The effects of preventive mental health programmes in secondary schools. World hospitals and health services: the official journal of the International Hospital Federation, 49(4), 8–11. https://doi.org/10.25142/spp.2016.003

- Atun, R., De Andrade, L. O. M., Almeida, G., Cotlear, D., Dmytraczenko, T., Frenz, P., Garcia, P., Gómez-Dantés, O., Knaul, F. M., Muntaner, C., de Paula, J. B., Rígoli, F., Serrate, P. C., & Wagstaff, A. (2015). Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America. The Lancet, 385(9974), 1230–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61646-9

- Bajpai, Prableen. (2022). What Countries Are the Top Producers of Oil? (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/what-countries-are-the-top-producers-of-oil

- Barr, B., Taylor-Robinson, D., Scott-Samuel, A., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2012). Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. British Medical Journal, 345(aug13 2), e5142. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5142

- Bayati, Y. F. K. A., & Bin Al-Hamid, Z. B. N. (2022). The impact of oil price fluctuations on the general budget and the Iraqi gross domestic product form the period 2010 to 2020. Journal of Business Management Studies, 4(3), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.32996/jhsss.2022.4.3.11

- Budhdeo, S., Watkins, J., Atun, R., Williams, C., Zeltner, T., & Maruthappu, M. (2015). Changes in government spending on healthcare and population mortality in the European Union, 1995–2010: a cross-sectional ecological study. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(12), 490–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076815600907

- Burke, S., Thomas, S., Barry, S., & Keegan, C. (2014). Indicators of health system coverage and activity in Ireland during the economic crisis 2008–2014–From ‘more with less’ to ‘less with less’. Health Policy, 117(3), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.07.001

- Charfeddine, L., & Barkat, K. (2020). Short-and long-run asymmetric effect of oil prices and oil and gas revenues on the real GDP and economic diversification in oil-dependent economy. Energy Economics, 86, 104680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104680

- Country Economy. Deficit: Countries comparison. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://countryeconomy.com/deficit

- Crude Oil Production. Trading Economics. (Accessed 14 October 2022). https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/crude-oil-production

- Delacre, M., Lakens, D., & Leys, C. (2017). Why psychologists should by default use Welch’s t-test instead of Student’s t-test. International Review of Socal Psychology, 30(1), 92–101. http://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.82

- Dieleman, J. L., Squires, E., Bui, A. L., Campbell, M., Chapin, A., Hamavid, H., Horst, C., Li, Z., Matyasz, T., Reynods, A., Sadat, N., Schneider, M. T., & Murray, C. J. L. (2017). Factors associated with increases in US health care spending 1996-2013. JAMA, 318(17), 1668–1678. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.15927

- Dizaj, J. Y., Anbari, Z., Karyani, A. K., & Mohammadzade, Y. (2019). Targeted subsidy plan and Kakwani index in Iran health system. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_16_19

- Edney, L., Haji Ali Afzali, H., Cheng, T., & Karnon, J. J. H. P. (2018). Mortality reductions from marginal increases in public spending on health. Health Policy, 122(8), 892–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.04.011

- Financial, Expat. (2022). Algeria Healthcare System & Insurance Options for Expats Expat Financial. https://expatfinancial.com/healthcare-information-by-region/african-healthcare-system/algeria-healthcare-system/

- Fowler, Charlotte. (2017). Venezuela: Healthcare in Times of Crisis. Public Health in Latin America. (Accessed 2022, July 23) https://sites.google.com/macalester.edu/phla/key-concepts/venezuela-healthcare-in-times-of-crisis

- Gerdtham, U. G., & Jönsson, B. (2000). International comparisons of health expenditure: theory, data and econometric analysis. Handbook of health economics, 1(A), 11–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0064(00)80160-2

- The Global Economy. (2019). Oil revenue - Country rankings. The Global Economy. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/texts_new.php?page=aboutus

- Haralayya, B. (2021). Study on Trend Analysis at John Deere. IRE Journals, 5(1), 171–181. https://irejournals.com/formatedpaper/1702838.pdf

- Harirchi, I., Hajiaghajani, M., Sayari, A., Dinarvand, R., Sadat, H. S., Maddavi, M., Ahmadnezhad, E., Olyaeemanesh, A., & Majdzadeh, R. (2020). How health transformation plan was designed and implemented in the Islamic Republic of Iran?. International Journal of Preventative Medicine, 11(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_430_19

- Ikeanyibe, O. M. (2016). New public management and administrative reforms in Nigeria. 39(7), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3250011

- Jaff, D., Tumlinson, K., & Al-Hamadan, A. (2018). Challenges to the Iraqi health system call for reform. Journal of Health Systems, 3(2), 9–12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335965009_Challenges_to_the_Iraqi_Health_System_Call_for_Reform

- Johnston, B. M., Burke, S., Barry, S., Normand, C., Ní Fhallúin, M., & Thomas, S. (2019). Private health expenditure in Ireland: Assessing the affordability of private financing of health care. Health Policy, 123(10), 963–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.08.002

- Karanikolos, M., Heino, P., McKee, M., Stuckler, D., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2016). Effects of the global financial crisis on health in high-income OECD countries: A narrative review. International Journal of Health Servcies, 46(2), 208–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731416637160

- Keane, C., Regan, M., & Walsh, B. (2021). Medicine. Failure to take-up public healthcare entitlements: Evidence from the Medical Card system in Ireland. Social Science & Medicine, 281, 114069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114069

- Keegan, C., Thomas, S., Normand, C., & Portela, C. (2013). Measuring recession severity and its impact on healthcare expenditure. International Journal of Healthcare Finance and Economics, 13(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-012-9121-2

- Khoja, T., Rawaf, S., Qidwai, W., Rawaf, D., Nanji, K., & Hamad, A. (2017). Health care in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: a review of challenges and opportunities. Cureus, 9(8), e1586. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1586

- Kisswani, K. M., Lahiani, A., & Mefteh-Wali, S. (2022). An analysis of OPEC oil production reaction to non-OPEC oil supply. Resources Policy, 77, 102653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102653

- Koornneef, E., Robben, P., & Blair, I. (2017). Progress and outcomes of health systems reform in the United Arab Emirates: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2597-1

- Lafta, R. K., & Al-Nuaimi, M. A. (2019). War or health: a four-decade armed conflict in Iraq. Medicine, Conflice and Survival, 35(3), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2019.1670431

- Lindström, M., & Giordano, GNJSS, Medicine. (2016). The 2008 financial crisis: Changes in social capital and its association with psychological wellbeing in the United Kingdom–A panel study. Social Science & Medicine, 53, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.008

- Loughnane, C., Murphy, A., Mulcahy, M., McInerney, C., & Walshe, V. (2019). Have bailouts shifted the burden of paying for healthcare from the state onto individuals?. Irish Journal of Medicine, 188(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1798-x

- Macrotrends. Crude Oil Prices – 70 Year Historical Chart. (Accessed 2022, October 14). https://www.macrotrends.net/1369/crude-oil-price-history-chart#google_vignette

- Martínez, L. (2022). Natural resource rents, local taxes, and government performance: Evidence from Colombia. Working paper, University of Chicago.

- Mead, Dave, & Stiger, Porscha. (2015). The 2014 plunge in import petroleum prices: What happened? (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-4/pdf/the-2014-plunge-in-import-petroleum-prices-what-happened.pdf

- Odunyemi, A. E. (2021). The Implications of Health Financing for Health Access and Equity in Nigeria. Healthcare Access. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.98565

- OECD OfECaD. (2022). Fule Taxes by country Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10327

- Onour, I., & Abdo, M. M. (2022). Sensitivity of Crude Oil Price Change to Major Global Factors and to Russian–Ukraine War Crisis. Journal of Sustainable Business Economics, 5(2), 4641. https://doi.org/10.30564/jsbe.v5i2.10

- OPEC OotPEC. OPEC Basket Price. Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries OPEC. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/40.htm

- OPEC OotPEC. 2013 Annual Report. 2013. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/AR_2013.pdf

- OPEC OotPEC. 2017 Annual Report. 2017. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/AR%202017.pdf

- OPEC OotPEC. 2020 Annual Report. 2020. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/AR%202020.pdf

- OPEC OotPEC. OPEC Member Countries. Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries OPEC. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/25.htm

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD. OPEC Countries 2022 - World Population Review. (Accessed 2022, August 06). https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/opec-countries

- Otu, E. (2018). Geographical access to healthcare services in Nigeria–a review. Journal of Integrative Humanism, 10(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3250011

- Pappa, E., Kontodimopoulos, N., Papadopoulos, A., Tountas, Y., & Niakas, D. (2013). Investigating unmet health needs in primary health care services in a representative sample of the Greek population. Environmental Health and Public Health, 10(5), 2017–2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10052017

- Pittaluga, G. B., Seghezza, E., & Morelli, P. (2021). The political economy of hyperinflation in Venezuela. Public Choice, 186(3), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-019-00766-5

- Qin, M., Su, C.-W., Hao, L.-N., & Tao, R. J. E. (2020). The stability of US economic policy: Does it really matter for oil price?. Energy, 198, 117315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117315

- Roa, A. C. (2018). The health system in Venezuela: a patient without medication?. Cad. Saúde Pública, 34(3), e00058517. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00058517

- Scherer, M. D. D., Conill, E. M., Jean, R., Taleb, A., Gelbcke, F. L., Pires, D. E. P., & Joazeiro, E. M. G. (2018). Challenges for health: a comparative study of University Hospitals in Algeria, Brazil and France. Ciênc. saúde colet, 23(7), 2265–2276. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018237.08762018

- Singh, S. (2014). Public health spending and population health: a systematic review. Public Health Spending and Population Health, 47(5), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.017

- Statista. Daily production of crude oil in OPEC countries from 2012 to 2020. (Accessed 2022c, August 06). https://www.statista.com/statistics/271821/daily-oil-production-output-of-opec-countries/

- Statista. Inflation rate from 1985 to 2023. (Accessed 2022b, October 14). https://www.statista.com/statistics/371895/inflation-rate-in-venezuela/

- Statista. Leading oil-producing countries worldwide in 2021. (Accessed 2022a, July 23). https://www.statista.com/statistics/237115/oil-production-in-the-top-fifteen-countries-in-barrels-per-day/

- Su, C. W., Chen, Y., Hu, J., Chang, T., & Umar, M. (2022). Can the green bond market enter a new era under the fluctuation of oil price?. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 2022, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2077794

- Su, C. W., Qin, M., Tao, R., & Umar, M. (2020). Does oil price really matter for the wage arrears in Russia?. Energy, 208, 118350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.118350

- Trading Economics. Algeria recorded a Government Budget deficit equal to 4.90 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product in 2021. (Accessed 2022a, July 23). https://tradingeconomics.com/algeria/government-budget

- Trading Economics. Foreign Exchange Reserves in Kuwait. (Accessed 2022f, July 23). https://tradingeconomics.com/kuwait/foreign-exchange-reserves?continent=africa/forecast

- Trading Economics. Government Spending in Algeria decreased to 503099.10 DZD Million in 2020 from 607032.30 DZD Million in 2019. (Accessed 2022b, July 23). https://tradingeconomics.com/algeria/government-spending

- Trading Economics. Iraq Government Budget. (Accessed 2022c, July 23). https://tradingeconomics.com/iraq/government-budget

- Trading Economics. United Arab Emirates Government Budget. (Accessed 2022g, July 23). https://tradingeconomics.com/united-arab-emirates/government-budget

- Trading Economics. United Arab Emirates Government Debt to GDP. (Accessed 2022h, October 14). https://tradingeconomics.com/united-arab-emirates/government-debt-to-gdp

- Trading Economics. Venezuela Government Budget. (Accessed 2022d, July 23). https://tradingeconomics.com/venezuela/government-budget#:~:text=Government%20Budget%20in%20Venezuela%20averaged,percent%20of%20GDP%20in%202018

- Trading Economics. Venezuela Government Debt to GDP. (Accessed 2022e, July 23). https://tradingeconomics.com/venezuela/government-debt-to-gdp

- Turner, B. (2017). The new system of health accounts in Ireland: what does it all mean?. Irish Journal f Medical Science, 186(3), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1519-2

- Uzochukwu, B. S. C., Ughasoro, M., Etiaba, E., Okwuosa, C., Envuladu, E., & Onwujekwe, O. E. (2015). Health care financing in Nigeria: Implications for achieving universal health coverage. Nigerial Journal of Clinical Practice, 18(4), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.154196

- The World Bank. GDP (current US$). (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD

- World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database. (Accessed 2022, July 23). https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en

- Zakeri, M., Olyaeemanesh, A., Zanganeh, M., Kazemian, M., Rashidian, A., Abouhalaj, M., & Tofighi, S. (2015). The financing of the health system in the Islamic Republic of Iran: A National Health Account (NHA) approach. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 29, 243. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4715399/

- Zare, H., Trujillo, A. J., Driessen, J., Ghasemi, M., & Gallego, G. (2014). Health inequalities and development plans in Iran; an analysis of the past three decades (1984–2010). International Journal of Equity in Health, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-42

- Zhang, P., Zhang, X., Brown, J., Vistisen, D., Sicree, R., Shaw, J., & Nichols, G. (2010). Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 87(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.026