Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the factors that promote or discourage knowledge-sharing behaviour among academic staff in higher education institutions. The main objective of this study was to investigate the effects of organizational factors and personality on knowledge-sharing behaviour. Utilizing three main theories—those of social capital, social cognition, and social exchange, this study developed a theoretical model that unveiled two critical dimensions: psychological and organizational factors that are believed to explain knowledge-sharing behaviour. A dataset was collected from 203 academic staff members working at a public university in Vietnam. Pearson’s correlation and multiple regression analyses were used to analyse the data. The results indicated that two components of the organizational factors, trust and organizational support, were positively and significantly related to knowledge sharing, whereas information technology did not influence knowledge sharing. The findings also show strong, significant positive relationship between extroversion and knowledge-sharing behaviour, whereas, there is a negative relationship between introversion and knowledge-sharing behaviour. The findings also show that perceived reciprocal benefits and reputation enhancement have strong influences on knowledge-sharing behaviour.

Public interest statement

Knowledge is one of the crucial and dominant economic resources in order to obtain sustainable advantages in any community. In an academic institution, sharing knowledge is crucial to exploiting core competencies and achieving sustained competitive advantage. To allow collective learning and grow knowledge assets, a university must develop an effective knowledge-sharing process and encourage its employees and partners to share knowledge among its members.

1. Introduction

Knowledge is a source of competitive advantage because it signifies intangible assets that are unique, inimitable, and non-substitutable (Spender, Citation1996). Information is believed to be the most crucial component in fuelling innovation in a global economy (Stewart, Citation1997). Knowledge, which is a fluid combination of framed experiences, values, contextual data, and expert insights, provides the foundation for interpreting and assimilating new experiences and information (Davenport & Prusak, Citation1998). Although Alavi and Leidner (Citation2001) observe that the source of competitive advantage resides not in the mere existence of knowledge at any given point in time, organizations are approving knowledge management initiatives and are capitalizing heavily on information and communication technologies in the form of knowledge management systems (Alavi & Leidner, Citation2001; Davenport & Prusak, Citation1998). Knowledge management has been identified as a critical function and strategic instrument for achieving or maintaining a sustainable competitive advantage (Sharimllah et al., Citation2009). However, the propensity to hoard information is so prevalent that it is regarded as a fundamental human trait (Davenport & Prusak, 1988). Knowledge sharing is a strategic enabler of knowledge management (Alavi & Leidner, Citation2001; Nonaka & Takeuchi, Citation1995). Sharing knowledge is crucial for exploiting core competencies and achieving a sustained competitive advantage (Argote et al., Citation2000). To allow collective learning and grow knowledge assets, an organization must develop an effective knowledge-sharing process and encourage its employees and partners to share knowledge about customers, competitors, markets, and products (Bock & Kim, Citation2002; Osterloh & Frey, Citation2000). According to Liebowitz and Chen (Citation2001), knowledge sharing can provide incremental benefits to a company, resulting in the translation of personal knowledge into corporate knowledge. Numerous studies have confirmed that knowledge sharing and cooperation are the most important organizational factors for sustaining competitiveness (Tapscott & Williams, Citation2006).

The development and wealth of a nation are determined by the quality of its higher education, which also determines its social, political, technological and economic environments and modernization (Nawaz & Gomes, Citation2014). Due to competition and increasingly dynamic environments in the 21st century, the strength of a successful university is in its ability to create, manage, and use knowledge in the most effective way (Geng et al., Citation2005). Knowledge management in higher education is the art of increasing the value from selected knowledge assets, which could improve its effectiveness (Biloslavo & Trnavcevic, Citation2007). Although knowledge sharing in higher education institutions has become extremely important, unfortunately, many universities have not accepted the need for knowledge sharing among their members as an inevitable effort towards their survivability (Adamseged & Janne, Citation2018). Employees’ unwillingness to share their knowledge can harm an organization (Lin, Citation2007), especially universities, which exist to create and share knowledge. Therefore, many researchers focuses on investigating factors that influence on knowledge sharing. For example, Ardichvili (2008), in offering a general review, identifies motivation factors (personal benefits, community-related considerations, and normative considerations), barriers (interpersonal, procedural, technological, and cultural), and enablers (supportive corporate culture, trust, and tools). Seba et al. (Citation2012) suggest that more research is needed that focuses on the organizational context of knowledge sharing. Moreover, to implement successful knowledge management and promote knowledge sharing in Oriental cultures, it is necessary to understand and accommodate the associated cultural values and cultural approaches to organizations (Nguyen & Tran, Citation2020).

Recently, the Vietnamese government is taking efforts for public higher education institutions to function efficiently by providing them autonomy in operation, organization, and finance. Under the extremely fierce competition among universities in Vietnam, the autonomy offers more room to higher education institutions in better decision making based on their resources. It is undeniable that human resource is the most important asset of an organization. In universities, specifically, the academic staff members play an important role in university development. Thanks to the autonomy mechanism, piloting universities can attract more capable lecturers and researchers. Therefore, management of knowledge has become critical in universities and knowledge sharing in higher education has become the focus of attention for public universities. As a result, most public educational institutions in Vietnam that are piloting autonomy policies use a multitude of effective tools for promoting knowledge sharing activities. Despite the fact that studies have advocated the implementation of knowledge management systems in higher education institutions in Vietnam, relatively few empirical studies have simultaneously evaluated the effects of organizational factors and personality traits on knowledge sharing behaviour. This study contributes to an understanding of knowledge sharing in the public sector higher education institutions in Vietnam under the first stage of piloting university autonomy mechanism. The main objective of this study is to investigate the psychological and organizational factors that shape the actual knowledge sharing behaviours of academic staffs.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Theoretical background

2.1.1. Social capital theory

Social capital was first systematically conceptualized by Coleman (Citation1988). Putnam (Citation1993) found a strong correlation between measures of civic engagement and government quality, which furthered social capital research to its current widespread and lively phase of development. Social capital theory explains the network of relationships that are created among individuals or a group of people with the set of resources within it; this method is likely to facilitate knowledge sharing among members (Chiu et al., Citation2006). The factors identified to form part of social capital are trust, recognition, common language, and shared vision. Social capital theory is considered to be a framework for understanding the importance of interpersonal connections and shared resources. This method is likely to facilitate knowledge sharing among members (Chiu et al., Citation2006).

2.1.2. Social cognitive theory

According to social cognitive theory, people’s interactions are greatly influenced by their personal characteristics, those of their environment, and their actions (Hsu et al., Citation2007). The theory explains that individuals’ personal factors interact with behavioural and environmental aspects, which results in triadic reciprocity (Lu et al., Citation2006). Trust and altruism are considered environmental factors, as they can influence personal characteristics and the behaviour itself (Papadopoulos et al., Citation2013). Others have considered the norm of reciprocity as an environmental factor, whereas perceived relative advantage and perceived compatibility are personal factors (Chen & Hung, Citation2010; Ling et al., Citation2009). Social cognitive theory has served as the sole theoretical foundation for numerous previous investigations (Chen & Hung, Citation2010; Hsu et al., Citation2007; Lin, Citation2007; Xu et al., Citation2012).

2.1.3. Social exchange theory

The social exchange theory refers people’s behaviours are driven by the typical and expected benefits they receive from others (Blau, Citation1964). The social exchange was developed to explain the non-contractual relationships between individuals (Staples & Webster, Citation2008). This concept is predicated on the projected returns and benefits of cooperative behaviour. The theory proposes that there are two categories of perception (organizational support and supervisor support) that influence one’s behaviour within an organization (Eisenberger & Cameron, Citation1996). The social exchange theory explains that the motivation behind an individual’s social interaction is the expectation that he or she would receive social rewards, such as respect, status, and approval (Liao et al., Citation2010). Organizational support theory is an extension of the social exchange theory.

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. Trust

Trust is considered the most important among the key variables of social exchange theorists; consequently, the persistence and extension of social exchange is based on trust between actors in an exchange relationship (Blau, Citation1964). The social exchange theory is one of the theories that seek to describe how individuals communicate with one another (Bock et al., Citation2005). Gambetta (Citation2000) defined trust is the willingness to be vulnerable based on positive expectations about the actions of others. Trust has been recognized as a factor that influences knowledge sharing (Alam et al., Citation2009; Bousari & Hassanzadeh, Citation2012; Cheng et al., Citation2009; Jolaee et al., Citation2014; Nguyen & Tran, Citation2020). Trust is the most efficient and economical technique for motivating people to contribute their own knowledge and establish and maintain exchange relationships that may lead to the spread of high-quality information (Liang et al., Citation2008). According to Hislop (Citation2005), trust is also a contributing factor that reflects employees’ dedication to sharing knowledge. Employees are more likely to share their knowledge if they believe that doing so will benefit them and the organization as a whole (Riege, Citation2005). Furthermore, Nguyen and Tran (2019) confirm that when a university maintains trustworthiness among its members, knowledge-sharing behaviour improves. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Trust has a positive effect on knowledge sharing behaviour.

2.2.2. Organizational support

According to Jolaee et al. (Citation2014), organizational support is one of the most essential concepts in management literature, and its absence is one of the greatest impediments to knowledge sharing. Igbaria et al. (Citation1996) believe that if an organization provides available resources, relevant training, meaningful incentives, and removes barriers in knowledge sharing, the quality of knowledge sharing would be higher. Based on the social exchange theory, research has found a relationship between organizational support and knowledge-sharing behaviour because of employees’ interest in adopting behaviours that correspond to the support they receive from the organization (Bartol et al., Citation2009). In the earlier qualitative phase of this study, respondents confirmed that organizational support was particularly important in influencing knowledge sharing. A remarkable result is achieved with organizational support, not only in the form of financial support but also policies related to rewards and incentives for knowledge-sharing acts. In the Vietnam public higher education sector, the official salaries of lecturers that the state pays are not sufficient to make the ends meet; hence, lecturers are forced to earn extra income from external teaching jobs and scientific research projects. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Organizational support has a positive effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour.

2.2.3. Information technology

In the form of knowledge management systems, information and communication technologies enhance collaborative work and knowledge exchange. According to Davenport and Prusak (Citation1998), IT systems facilitate knowledge sharing, which boosts productivity. Technological variables include the availability of an information technology infrastructure that facilitates communication and the exchange of knowledge (Seba et al., Citation2012). Prior studies on information and knowledge sharing in the public sector have repeatedly stressed the use of information and communication technologies (Nguyen & Tran, Citation2020; Seba et al., Citation2012). Therefore, tools and technology that are regarded as easily accessible and easy to use are expected to have a positive effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Information technology has a positive effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour.

2.2.4. Perceived reciprocal benefits

The social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964) describes human behaviour in terms of social exchange. Prior research indicates that individuals share knowledge in anticipation that their future knowledge requests will be fulfilled by others (Bock et al., Citation2005; Kankanhalli et al., Citation2005). Bock and Kim (Citation2002) also note the importance of reciprocity in the context of knowledge sharing. Similarly, Kankanhalli et al. (Citation2005) indicate reciprocity to be a salient motivator of individuals’ knowledge contribution to electronic knowledge repositories. Thus, it is theorized that knowledge workers’ belief that their future knowledge needs will be met by others in return for knowledge shared by them is likely to have a positive effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Perceived reciprocal benefits have a positive effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour.

2.2.5. Perceived reputation enhancement

The SET suggests that social exchange engenders social rewards such as feelings of approval, status, and respect. Because reputation depends on an individual’s attributes and actions that are visible to others, people choose a specific self-image that they want to reflect and adjust their behaviour accordingly (Carroll et al., Citation2001). In Oriental cultures, lecturers and teachers are valued highly by the society. By demonstrating their expertise to others, employees achieve identification and respect, resulting in an improved self-concept (Kankanhalli et al., Citation2005). Therefore, it is claimed that employees’ belief that sharing knowledge will enhance their reputation and status in the profession is likely to be an important motivator in sharing valuable knowledge. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Perceived reputation enhancement has a positive effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour.

2.2.6. Personality

Awad and Ghaziri (Citation2004) confirmed that people’s personal characteristics, or in other words, personalities might influence how they share their knowledge. Personality traits are considered a significant predictor of individual behaviour in the workplace (Penney et al., Citation2011). Personality consists of a person’s feelings, sense of self, views of the world, thoughts, and behaviour patterns (Jadin et al., Citation2013). Numerous elements have been identified to have an impact on the degree to which groups and teams share information. At the individual level, personality factors can influence workplace knowledge-sharing behaviours (Matzler et al., Citation2008). Introversion and extroversion are considered two personality dimensions, and it is believed that most people can be classified into these two categories (Akhavan et al., Citation2016; Bradley & Hebert, Citation1997)

Extroverts are far more likely than introverts to be outgoing, quick to make friends, confident, and comfortable. They are adept at the art of repartee, have a large network of contacts, and actively participate in gatherings, celebrations, and other public events. Extroverts have been found to be easy to build social relations, friendships, and partnerships with extroverts because they have excellent social skills and a preference for interaction (Doeven-Eggens et al., Citation2008). The literature demonstrates that extroverts experience positive feelings and a sense of fulfilment while working in groups and teams (McCrae & Costa, Citation1987). Multiple research studies have demonstrated that extroverted personalities promote information exchange (DeVries et al., Citation2006; Ferguson et al., Citation2010). Introversion is associated with subjective inner sight. Introverts are often more equipped with self-control and composure. They are less likely to participate in community activities and spend a lot of their time engaging in mental and solitary pursuits (Eysenck, Citation1947). Introverts are reserved, calm, trustworthy, and slightly pessimistic They rarely engage in conflict and frequently control their emotions (Akhavan et al., Citation2016). Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6: An extrovert personality has a positive effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour.

H7: An introvert personality has a negative effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour.

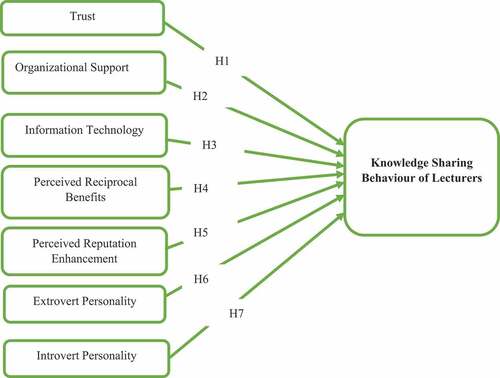

All hypotheses are illustrated in Figure

3. Research methodology

3.1. Sample and data collection

This study combined qualitative and quantitative research methods. In the qualitative research process, in-depth interviews were conducted to collect the data. Participants included ten lecturers from public universities who are piloting autonomy mechanisms in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. The study measured eight constructs: trust, organizational support, information technology, perceived reciprocal benefits, perceived reputation enhancement, extroversion, and introversion that adapting scales of the constructs to Vietnamese. The questionnaire was circulated among professional researchers and later was given to lecturers to pre-test. The final data were obtained via a cross-sectional survey of 203 academic staff members at the University of Finance—Marketing (UFM). Located in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, the UFM is one of the largest public higher education institutions belonging to the Ministry of Finance, Vietnam. This university is also one of the first public higher education units to have a pilot financial and administrative autonomy policy since 2015.

Convenient sample method was used in the study, and the sample size was determined using Green’s method for sample size for multiple regression (1991), using the formula n = 50 + 8*m, where “m” is the number of predictors in the proposed model. Using Green’s method, the required sample size was 106, and we conducted a self-administered survey of 300 lecturers to meet the minimum sample size requirement for this study. The response rate was 67.7 percent, as 203 out of the total disseminated questionnaires were returned and qualified for analysis.

3.2. Measurements

The scales to measure the constructs were produced based on validated instruments from prior studies (Table ). All the original scale items were translated into Vietnamese and back into English to ensure equivalent meaning (Brislin, Citation1980). The Trust (TR) scale was derived from Hsu et al. (Citation2007) and Bock et al. (Citation2005). The Organizational Support (OS) scale was adapted from studies by Kankanhalli et al. (Citation2005), Lin (Citation2007), and Bock et al. (Citation2005). The Information Technology (IT) scale was obtained from Lin (Citation2007) and Jolaee et al. (Citation2014). The Perceived Reciprocal Benefits (PRB) scale was adapted from studies by Kankanhalli et al. (Citation2005) and M. M. L. Wasko and Faraj (Citation2005). The Perceived Reputation Enhancement (PRE) scale was derived from studies by Kankanhalli et al. (Citation2005) and M. M. L. Wasko and Faraj (Citation2005), and scales that measured introversion (INT) and extroversion (EXT) was derived from Bradley and Hebert (Citation1997) and Akhavan et al. (Citation2016). Items used to measure the knowledge-sharing behaviour were developed based on the works of Lee (Citation2001) and Bock et al. (Citation2005). All measurements used a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Table 1. Constructs and scale items

3.3. Data analysis

In formal quantitative research, after collecting and cleaning the data, the valid data were encoded and analysed using the SPSS software. The data analysis process included the following main steps: descriptive statistics, testing the reliability of scales, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), correlation analysis, and regression analysis. The reliability of the scales was established using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. If Cronbach’s alpha values reached 0.7, and the corrected item-total correlation coefficients were ≥ 0.3, the scales had good reliability. The EFA was employed for all observed variables, varimax rotation, and eigenvalue > 1.0, to determine the representative factors for the variables. According to Hair et al. (2010), standards for the EFA include: (i) Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value from 0.5 to 1; (ii) the items are retained if their factor loading (FL) coefficients are higher than 0.3; (iii) total variance explained > 50%; and (iv) eigenvalue > 1. Finally, scales retained after the EFA were recoded, and correlation analysis and multivariate regression were run to test the research model and hypotheses. The SPSS 22.0 software was used as a tool for analysis in this study.

4. Research findings and discussion

4.1. Respondents’ characteristics

As shown in Table , 65 percent of the 203 respondents were female and 35 percent were male. The majority of respondents (83.3%) held MBA, while 19.7% held doctorates. Table also displays the age ranges and teaching experience of the respondents. More than half (55.7%) of the respondents were between the ages of 30 and 45 years, and more than half (54.2%) had over 10 years of teaching experience. In particular, 30.1% (approximately one-third) of the respondents had 5 to 10 years of teaching experience, whereas only 10.8% has 1 to 5 years of teaching experience. Very few respondents (4.9%) had less than one year of teaching experience.

Table 2. Respondents’ demographic information

4.2. Measurement model analysis results

This study adopted Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to analyse the measurement model. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were greater than 0.8 and the corrected item-total correlation coefficients were greater than 0.3 for all scales. The Cronbach’s alpha values indicated a high level of reliability. Next, the exploratory factor analysis was conducted using the Principal Component Extraction method with varimax rotation and an eigenvalue larger than 1.0 as the criterion. The EFA result indicated that eight factors were extracted, the KMO value was greater than 0.5 (0.781), and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity had significance value less than 0.05, eigenvalue > 1 (1.581); the dataset was appropriate for the EFA, and all items were retained because factor loadings were more than 0.5 (Table ).

Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha and exploratory factor analysis results

4.3. Regression results

4.3.1. Correlation analysis

Multiple regression analysis was used to test the models and hypotheses. We examined the correlation between the independent and dependent variables, and the results indicated that all seven independent variables had a substantial connection with the dependent variable. Of the seven exogenous variables, TR, OS, IT, PRB, PRE, and EXT were positively correlated with the endogenous variable, whereas INT had a negative correlation with the dependent variable. Consequently, all independent variables were used to investigate multiple linear regressions with the dependent variable (Table ).

Table 4. Pearson’s correlation coefficients

4.3.2. Regression model results

Regression model analysis was carried out based on applying the method of Enter in multiple linear regression. The statistical results were: R2 = 0.617 and adjusted R2 = 0.605 (Table ). The adjusted R-square showed that independent variables caused 60.5% variance in the dependent variable. In other words, an estimated 60.5% of the knowledge-sharing behaviour is accounted for by independent variables, the remaining being due to other variables caused by non-model factors. The result of the ANOVA (analysis of variance; Table ) illustrates the statistical value F = 52.636, and Sig. = 0.000 with a confidence level of 99%. This shows that the theoretical model is consistent with the actual data. In other words, the independent variables have a linear correlation with the dependent variable at a 99% confidence level.

Table 5. Result of regression model summary

Table 6. Result of ANOVA test

The hypotheses testing results (Table ) indicate that, with the exception of IT, the six independent factors have a significantly positive correlation with knowledge-sharing behaviour. The results of the standard regression coefficient values indicated that trust (TR) is the strongest significant predictor of a lecturer’s knowledge-sharing behaviour. Organizational support (OS) has a significant impact on the knowledge-sharing behaviour; however, information technology (IT) does not show any significant effect. Moreover, hypothesis testing revealed that perceived reciprocal benefits (PRB) and perceived reputation enhancement (PRE) have a statistically significant influence on the knowledge-sharing behaviour. Finally, extroversion (EXT) has a positive significant influence on the knowledge-sharing behaviour; by contrast, introversion (INT) has a negative significant impact on lecturers’ knowledge-sharing behaviour.

Table 7. Result of regression coefficients and hypotheses testing

4.4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to enhance our collective understanding of the factors affecting knowledge-sharing behaviours based on two sets of key factors: organizational and personal, which are considered to influence knowledge-sharing behaviours, including trust, organizational support, information technology, perceived reciprocal benefits, perceived reputation enhancement, introversion, and extroversion. The results of the hypothesis testing were as follows:

The effect of trust on the knowledge-sharing behaviour was statistically significant, supporting Hypothesis 1. This indicates that lecturers who have faith in their organization and co-workers engage in extensive knowledge exchanges. This finding is in contrast with that of Jolaee et al. (Citation2014); however, it supports the social exchange theory and is consistent with some of the earlier studies, including those of Davenport and Prusak (Citation1998) and Nguyen and Tran (Citation2020). This finding shows that trust is crucial in knowledge sharing.

In addition, organizational support has a positive and significant influence on the knowledge-sharing behaviour, supporting Hypothesis 2. It is seen as an important predictor of the knowledge-sharing behaviour, as it contributes to the creation and provision of a supportive atmosphere and suitable resources for knowledge-sharing activities. As proposed and supported by earlier research, a greater level of assistance would enhance lecturers’ knowledge sharing. This outcome is consistent with the findings of Igbaria et al. (Citation1996) and Jolaee et al. (Citation2014). It is noteworthy that in the context of this study, organizational support includes both financial and reward policy support. Financial support is an individual’s belief that monetary incentives will be provided for knowledge-sharing activities. The result confirms that financial and monetary rewards are important factors that encourage the knowledge-sharing behaviour at public universities in a developing nation.

Surprisingly, the results of this study appear to reject the hypothesis that information technology has a positive effect on knowledge-sharing. The finding contrasts with previous studies that identified information technology as an important factor affecting knowledge sharing (Davenport & Prusak, Citation1998; Nguyen & Tran, Citation2020). This inconsistency may be related to the context of the study, and with the development of information technology, lecturers have many ways to connect and exchange information with colleagues easily. In addition, lecturers also have the ability to study, update themselves with new knowledge, and make use of information to facilitate knowledge sharing in both formal and informal networks. This means the lectures do not need the supports of information technology from universities.

This study found that perceived reciprocal benefits have a significant but moderate effect on knowledge-sharing behaviours. This finding supports the social exchange theory and findings of prior research, where generalized reciprocity was consistently found to be an important predictor of knowledge contribution (Connolly & Thom, 1990; Constant et al., Citation1994; M. M. Wasko & Faraj, Citation2000). The significance of perceived reciprocal benefits indicates that knowledge workers are likely to engage in knowledge sharing with the expectation of receiving future help from others, in return for sharing knowledge. Consistent with the social exchange theory, perceived reputation enhancement has a significant positive effect on knowledge-sharing behaviours. This finding suggests that knowledge workers are likely to engage in knowledge sharing with the desire to build professional reputation. By sharing knowledge, they display their skill sets and impress others. This results in their being acknowledged, recognized, and respected. Prior research on online communities of practice, open-source programming communities, and electronic knowledge repositories has indicated that increased reputation and visibility among co-workers and the relevant community are important motivators for participating in knowledge sharing (Kankanhalli, 2005; Wasko & Faraj, Citation2000).

This study also demonstrated that both H6 and H7 were supported. This indicates that extroversion has a positive relationship with the knowledge-sharing behaviour, whereas introversion has a negative influence. These findings support the conclusion reached by Akhavan et al. (Citation2016), who confirmed that extroverts are more likely than introverts to share their thoughts and communicate with others.

5. Managerial implications

This study examines the factors that explain the knowledge-sharing behaviour in the context of public universities in Vietnam. It contributes by filling the gap left by previous research that focused primarily on predictors of the knowledge-sharing behaviour. This research has shed light on the relationship between personal and organizational characteristics and the knowledge-sharing behaviour.

Trust was the strongest predictor of lecturers’ knowledge-sharing behaviour. In the context of this study, trust is defined as the degree of trust in colleagues and their knowledge. Once lecturers feel safe and confident with their peers, they feel comfortable sharing their ideas. The managements must improve lecturers’ perceptions of trustworthiness and facilitate the development of an atmosphere where they feel comfortable. To this end, managements should design and implement supportive plans and culture for employees. This can be achieved through activities such as meetings, parties, and special occasions, which enhance engagement and trust among lecturers.

In this study, organizational support refers to the level of support that an organization provides for knowledge sharing, and is believed to play a crucial role in promoting knowledge exchange. In an effort to encourage teaching staff to share their expertise, managements should develop a supportive environment, including financial support and attractive incentive strategies linked to the knowledge-sharing behaviour.

The results showed that perceived reciprocal benefits have a significant but moderate effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour. This finding supports the findings of prior research, where generalized reciprocity was consistently found to be an important predictor of knowledge contribution (Connolly & Thom, 1990; Constant et al., Citation1994; M. M. Wasko & Faraj, Citation2000). The significance of perceived reciprocal benefits indicates that knowledge workers are likely to engage in knowledge sharing with the expectation of receiving future help from others, in return for sharing knowledge. Moreover, perceived reputation enhancement has a significant positive effect on the knowledge-sharing behaviour. This finding suggests that knowledge workers are likely to engage in knowledge sharing with the desire to build professional reputation. By sharing knowledge, knowledge workers display their skill sets and impress others. This results in their being acknowledged, recognized, and respected.

Introversion and extroversion are two important personality traits (Ross, Citation1992). This study established a connection between the two types of personality and the knowledge-sharing behaviour of the teaching staff. The results indicate that extroversion has a beneficial effect on the behaviour of university instructors with regard to knowledge sharing. This is because this personality type is characterized by sociability and enjoyment of interpersonal communication (Mount et al., Citation1998). Therefore, an organization’s management should have recruitment strategies to select candidates who are likely extroverts.

6. Limitations and future research

This study focused only on one official type of knowledge–the knowledge that lecturers communicate; therefore, non-official knowledge sharing is a potential and fruitful area for additional research. In addition, the data collection was limited to a single public higher education institution, excluding the teaching staff of private universities. Consequently, future research should enlarge the sample size to generalize the findings and shed light on disparities in the knowledge-sharing behaviours of teaching staff at public and private colleges. Future research should explore the significance of additional variables such as the impact of digital media like the social media. As a group of Internet-based applications, social media allows academic staff to share user-generated content (Kaplan & Haenlein, Citation2010). Indeed, social media has introduced substantial changes in communication among individuals, communities, and organizations; there is substantial room to investigate its role in knowledge sharing among academic staff. Prior research on online communities of practice, open-source programming communities, and electronic knowledge repositories has indicated that increased reputation and visibility among co-workers and the relevant community are important motivators for participating in knowledge sharing (Kankanhalli et al., Citation2005; Wasko & Faraj, Citation2000).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the University of Finance – Marketing

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Du Thi Chung

Du Thi Chung is a lecturer at the Faculty of Marketing, University of Finance - Marketing. Her research directions include consumer behaviour, service quality, marketing strategy, and corporate innovation. Currently, she teaches marketing research, B2B marketing management, and strategic marketing.

Pham Thi Tram Anh

Pham Thi Tram Anh is a lecturer in business management and currently in charge of subjects such as enterprise culture, business ethics, and management at the Faculty of Administration Management, University of Finance - Marketing.

References

- Adamseged, H., & Janne, J. (2018). Knowledge sharing among university faculty members. The Journal of Educational Research, 9(24), 1–10. https://www.iiste.org

- Akhavan, P., Dehghani, M., Rajabpour, A., & Pezeshkan, A. (2016). An investigation of the effect of extroverted and introverted personalities on knowledge acquisition techniques. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 46(2), 194–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-06-2014-0043

- Alam, S., Abdullah, Z., Ishak, N., & Zain, Z. M. (2009). Assessing knowledge sharing behaviour among employees in SMEs: An empirical study. International Business Research, 2(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v2n2p115

- Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250961

- Argote, L., Ingram, P., Levin, J. M., & Moreland, R. L. (2000). Organizational learning: Creating, retaining, and transferring knowledge. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Awad, E. M., & Ghaziri, H. M. (2004). Knowledge management. New Jersey: Pearson Education.

- Bartol, K. M., Liu, W., Zeng, X., & Wu, K. (2009). Social exchange and knowledge sharing among knowledge workers: The moderating role of perceived job security. Management and Organization Review, 5(2), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2009.00146.x

- Biloslavo, R., & Trnavcevic, A. (2007). Knowledge management audit in a higher educational institution: A case study. Knowledge and Process Management, 14(4), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.293

- Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. Wiley.

- Bock, G. W., & Kim, Y. G. (2002). Breaking the myths of rewards: An exploratory study of attitudes about knowledge sharing. Information Resources Management Journal, 15(2), 14–21. https://dx.doi.org/10.4018/irmj.2002040102

- Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y. G., & Lee, J. N. (2005). Behavioural intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148669

- Bousari, R. G., & Hassanzadeh, M. (2012). Factors that affect scientists’ behaviour to share scientific knowledge. Collnet Journal of Scientometrics and Information Management, 6(2), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09737766.2012.10700935

- Bradley, J. H., & Hebert, F. J. (1997). The effect of personality type on team performance. Journal of Management Development, 16(5), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621719710174525

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology (pp. 389–444). Allyn and Bacon.

- Carroll, A., Hattie, J., Durkin, K., & Houghton, S. (2001). Goal-setting and reputation enhancement: behavioural choices among delinquent, at-risk and not at-risk adolescents. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 6(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532501168262

- Cheng, M. Y., Ho, J.S.Y, & Lau, P. M. (2009). Knowledge sharing in academic institutions: A study of multimedia university, Malaysia. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(3), 313–324. www.ejkmcom

- Chen, C. J., & Hung, S. W. (2010). To give or to receive? Factors influencing members’ knowledge sharing and community promotion in professional virtual communities. Information & Management, 47(4), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2010.03.001

- Chiu, C. M., Hsu, M. H., & Wang, E. T. (2006). Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decision Support Systems, 42(3), 1872–1888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2006.04.001

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2780243

- Constant, D., Kiesler, S., & Sproull, L. (1994). What’s mine is ours, or is it? A study of attitudes about information sharing. Information Systems Research, 5(4), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.5.4.400

- Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: How organisation manage what they know. Havard Business school Press.

- DeVries, R. E., van den Hooff, B., & de Ridder, J. A. (2006). Explaining knowledge sharing the role of team communication styles, job satisfaction, and performance beliefs. Communication Research, 33(2), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205285366

- Doeven-Eggens, L, De Fruyt, F, Hendriks, J., Bosker, R, & Van der Werf, M. P. C. (2008). Personality and personal network type. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(7), 689–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.017

- Eisenberger, R., & Cameron, J. (1996). Detrimental effects of reward: reality or myth?. American Psychologist, 51(11), 1153–1166. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.51.11.1153

- Eysenck, H. (1947). Dimensions of Personality. Transaction Publishers.

- Ferguson, R. J., Paulin, M., & Bergeron, J. (2010). Customer sociability and the total service experience: Antecedents of positive word-of-mouth intentions. Journal of Service Management, 20(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231011025100

- Gambetta, D. (2000). Can we Trust, Trust? In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations (electronic) ed., Vol. 13, pp. 213–237). Department of Sociology, University of Oxford.

- Geng, Q., Townley, C., Huang, K., & Zhang, J. (2005). Comparative knowledge management: A pilot study of Chinese and American universities. Journal of American Society for Information Science and Technology, 56(10), 1031–1044. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20194

- Hislop, D. (2005). Knowledge Management in Organizations, A Critical Introduction. University Press.

- Hsu, M. H., Ju, T. L., Yen, C. H., & Chang, C. M. (2007). Knowledge sharing behaviour in virtual communities: The relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. International Journal of human-computer Studies, 65(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.02.008

- Igbaria, M., Parasuraman, S., & Baroudi, J. J. (1996). A motivation model of microcomputer usage. Journal of Management Information Systems, 13(1), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.1996.11518115

- Jadin, T., Gnambs, T., & Batinic, B. (2013). Personality traits and knowledge sharing in online communities. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.007

- Jolaee, A., Md. Nor, K., Khani, N., & Mdyusoff, R. (2014). Factors affecting knowledge sharing intention among academic staff. Int Journal Education Management, 28(4), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-03-2013-0041

- Kankanhalli, A., Tan, B. C. Y., & Wei, K. K. (2005). Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 113–143. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148670

- Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges an opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

- Lee, J. N. (2001). The impact of knowledge sharing, organizational capacity and partnership quality on IS outsourcing success. Information and Management, 38(5), 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(00)00074-4

- Liang, T. P., Liu, C. C., & Wu, C. H. (2008). Can social exchange theory explain individual knowledge-sharing behaviour? A meta-analysis. International Conference on Information Systems Proceedings: http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2008/171 (accessed 21 April 2017).

- Liao, C., Lin, H. N., & Liu, Y. P. (2010). Predicting the use of pirated software: A contingency model integrating perceived risk with the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0081-5

- Liebowitz, J., & Chen, Y. (2001). Developing knowledge - sharing proficiencies. Knowledge Management Review, 3, 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-24746-3_21

- Lin, H. F. (2007). Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on employee knowledge sharing intentions. Journal of Information Science, 33(2), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551506068174

- Ling, C. W., Sandhu, M. S., & Jain, K. K. (2009). Knowledge sharing in an American multinational company based in Malaysia. Journal Workplace Learn, 21(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620910934825

- Lu, L., Leung, K., & Koch, P. T. (2006). Managerial knowledge sharing: The role of individual, interpersonal, and organizational factors. Management and Organization Review, 2(1), 15–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2006.00029.x

- Matzler, K., Renzi, B., Muller, J., Herting, S., & Mooradian, T. A. (2008). Personality Traits and Knowledge Sharing. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(3), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.06.004

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the fi ve-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

- Mount, M. K., Barrick, M. R., & Stewart, G. L. (1998). Five-factor model of personality and performance in jobs inPRElving interpersonal interactions. Human Performance, 11(2–3), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1102&3_3

- Nawaz, M. N., & Gomes, A. M. (2014). Review of knowledge management in higher education institutions. European Journal of Business and Management, 6(7), 71–79.

- Nguyen, T. C. L., & Tran, T. L. N. (2020). Key determinants of organization culture on the knowledge sharing of lecturers in academic institutions: A study in the University of finance- marketing. Journal Of Science And Technology, 46(4), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.46242/jst-iuh.v46i04.709

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge - creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Osterloh, M., & Frey, B. S. (2000). Motivation, knowledge transfer, and organizational forms. Organization Science, 11(5), 538–550. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.5.538.15204

- Papadopoulos, T., Stamati, T., & Nopparuch, P. (2013). Exploring the determinants of knowledge sharing via employee weblogs. International Journal of Information Management, 33(1), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.08.002

- Penney, L. M., David, E., & Witt, L. A. (2011). A review of personality and performance: Identifying boundaries, contingencies, and future research directions. Human Resource Management Review, 21(4), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.10.005

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). The prosperous community: social capital and public life. AmericanProspect, 4(13), 35–42.

- Riege, A. (2005). Three- dozen knowledge – Sharing barriers managers must consider. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(3), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270510602746

- Ross, A. O. (1992). Personality Psychology (Theories and Processes). Harper.

- Seba, I., Rowley, J., & Delbridge, R. (2012). Knowledge sharing in the Dubai Police Force. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(1), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271211198972

- Sharimllah, D. R., Chong, S. C., & Hishamuddin, I. (2009). The practice of knowledge management processes: A comparative study of public and private higher education institutions in Malaysia. Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 39(3), 203–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/03055720911003978

- Spender, J. C. (1996). Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(2), 45–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171106

- Staples, D. S., & Webster, J. (2008). Exploring the effects of trust, task interdependence and virtualness on knowledge sharing in teams. Information Systems Journal, 18, 617–640. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2007.00244.x

- Stewart, T. A. (1997). Intellectual Capital: The new wealth of organizations. Doubleday/Currency.

- Tapscott, D., & Williams, A. D. (2006). Wikinomics: How mass collaboration changes everything. Penguin Group.

- Wasko, M. M., & Faraj, S. (2000). It is what one Does: why people participate and help others in Electronic Communities of Practice. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 9(2–3), 155–173. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-8687(00)00045-7

- Wasko, M. M. L., & Faraj, S. (2005). Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148667

- Xu, B., Li, D., & Shao, B. (2012). Knowledge sharing in virtual communities: A study of citizenship behaviour and its social-relational antecedents. International Journal of Human Computer Interaction, 28(5), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2011.590121