?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Audit quality is a strong external monitoring mechanism to protect the interest of the owners according to agency theory. The auditor choice research has paid more attention to the audit committee overall but has overlooked the unique agency context of audit committee’s chairman characteristics on the audit quality especially on auditor choice. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the audit committee’s chairman characteristics on the auditor choice. The sample of 111 firms listed on the ACE market was used to test the hypotheses. Using logistic regression, this study finds that only the audit committee’s chairman tenure and busyness are significant factors that influence the auditor choice. Whereas, the audit committee’s chairman ethnicity, expertise and qualification have no significant influence on the auditor choice. These results have theoretical implications for the alignment and entrenchment hypotheses of the agency theory and practical implications for the regulators to improve the audit committee’s structure and regulations.

1. Background of the study

The independent auditor is considered as an important instrument that aligns the conflict of interest between the management and owners, where the independent auditor reports periodically to financial statement users (internal/external) on the truth and fairness of the financial statement issued by a company’s management (Watts & Zimmerman, Citation1983). According to the agency theory, the main reason behind the need for external auditing is to mitigate the conflict of interests among managers, owners and bondholders (Jensen, Citation1994). Carcello and Neal (Citation2000) concluded that audit quality has a role in the reduction of agency conflicts, where it enhances the reliability and credibility of accounting numbers. The author further stated that argued the audit quality and the role of statutory auditors may be influenced by the characteristics of company governance and the legal system for investor protection. However, due to the many corporate collapses, the confidence of investors in the quality and reliability of the financial system and audited financial information has been undermined (Carcello & Neal, Citation2000).

One of the main internal governance mechanisms is the AC that may influence the auditor choice (Carcello & Neal, Citation2000; He et al., Citation2017; Olowookere & Inneh, Citation2016; Tee & Rassiah, Citation2019). The AC enhances the internal monitoring mechanism that ultimately leads to better quality reporting (Tanyi & Smith, Citation2014). Whereas, the head of AC has a significant role in the overall effectiveness of the AC. Therefore, prior literature has identified that the characteristic of AC s is very important especially related to the chairman of the AC because he is the head and significant role in the overall effectiveness of the AC (Inaam & Khamoussi, Citation2016).

Many studies have been conducted on the issue of the role of AC in the audit quality, but the role of chairmen’s characteristics is ignored in the extant literature. The main reason behind the emphasis on the chairman’s attribute is that as a head he leads the AC and he is in the position to determine the decisions and effectiveness of AC. Moreover, according to agency theory, due to the appropriate role chairman, it can reduce the conflicts between management and owners, thereby facilitating and the relationship between management and external auditor well. Therefore, the studies related to chairmen’s characteristics and audit quality are very important theoretically and particularly. DeFond and Zhang (Citation2014) suggested more researches to be conducted on audit quality which is considered as a potential research avenue.

The scandals in the widely held corporations around the world, such as Enron, WorldCom, Tyco and Toshiba, as well as in closely held publicly listed firms, for example, Adelphia, Cirio, Parmalat Pescanova and Toshiba are related with bad accounting practices. There are also many Malaysian domestic accounting scandals in public listed firms, e.g., Technology Resources Industries Berhad, Transmile Group Berhad, Nasiocom Holdings Berhad, and Felda Group Berhad are also related with manipulation of accounting information. These firms deceived investors through false financial statements and shattered investors’ confidence (Darussamin et al., Citation2018). These cases not only highlighted the importance of quality of accounting information but also shed light on the issue of the poor auditing practices. The Malaysian regulators have done several efforts to improve accounting and auditing practice especially the introduction of corporate governance code and subsequent revision in 2012 and 2016. The revised code in 2016 related to the AC endorses that the members of the AC be comprised fully of non-executive directors, who are able to read, analyze and interpret financial statements. The MCCG 2012 concentrates on the strength of the structure and composition of the board of directors and recognizes its role as an active and responsible fiduciary. Despite the advanced steps that have been taken by Malaysian regulatory bodies to enhance the audit profession in Malaysia, the level of audit quality still needs to be significantly improved to ensure the quality of the firms is preserved.

In the following year of the establishment of AOB (audit oversight board), a number of Malaysian companies obtained qualified auditors’ opinions, such as Leader Steel Holdings Bhd., Lebar Daun Bhd., Vastalux Energy Bhd., ARK Resources Bhd., Matronic Global Bhd. and Ho Hup Construction Co. (The Star, Citation2011). Therefore, to be able to improve audit quality, Malaysian companies, as well as regulators, need to determine the level of audit quality and know the factors that may affect audit quality.

Most previous studies on audit quality have demanded the need for an external auditor and in the context of Malaysia as well (Che Ahmad et al., Citation2006; DeFond & Zhang, Citation2014; Hay, Citation2013; Nazatul Faiza Syed Mustapha Nazri et al., Citation2012), the current trend of appointing external auditors is different from how it was in the 1990s or early 2000s where the Big 4 audit firms dominated about 70% of the publicly listed companies on Bursa Malaysia. In relation to this, Johl et al. (Citation2012) documented that the Big 4 audit firms appear to dominate the Malaysian audit market with a market share of about 68.5%. In addition, Azmi et al. (Citation2013) documented that the significance of Big 4 audit firms in the Malaysian context lessened where its market share decreased from 75% to just shy of 60% in 20 years period (1991–2011). It is reported that many public listed companies turned from Big 4 audit firms to local audit firms. Thus, it is important to examine the factors affecting the demand for audit quality in Malaysia.

In addition, Francis (Citation2011) stated that more research should be carried out on the notion that good governance leads to the demand for a higher auditor quality. Recently, DeFond and Zhang (Citation2014) argued that the role of auditee’s competency (governance system) in driving audit quality needs more investigation. The recent literature also shed lights the AC as a one of the main determinants of the auditor choice (Al-Absy et al., Citation2018; Bajra & Čadež, Citation2018; Hansen et al., Citation2019; Onyabe et al., Citation2018; Tee & Rassiah, Citation2019). Moreover, the role of the chairman is much important because he is the head of the AC and contributing to the effectiveness of the AC. On the other hand, it is also notable that as head he may hire other members of the audit committee that are very close to him and dominate the board and misuse his power to influence audit committee decision. Prior literature has identified different audit committee’s chairman’ characteristics that may influence the auditor choice (Hansen et al., Citation2019; Lai et al., Citation2017; Lisic et al., Citation2019; Olowookere & Inneh, Citation2016; Shafie & Zainal, Citation2016; Tee & Rassiah, Citation2019). In turn, if it happens the quality of the audit will be low. Moreover, the ACE market is based on the companies which are not very big in size and therefore, due to resource constraints they are not interested to hire big 4 auditors. Thus, it is significant to investigate the effect of AC chairman’s characteristic on auditor choice in Malaysian ACE Market.

2. Literature review and related theory

This section presents the theories that are relevant to explain the demand for audit services or the choice of a particular level of audit quality. There are numerous theories that could explain the demand for audit services. Further, these theories complement each other (Wallace, Citation1984).

2.1. Agency theory

The agency theory has been used by academics in a variety of disciplines, including sociology, political science, marketing, economics, and accounting (Clarke, Citation2004). Agency theory helps explain the contractual relationship between owners and managers. The agency theory, according to Eisenhardt (Citation1989), focuses on overcoming two issues that arise from the conflict of interests and risk-sharing when the owner and management have different viewpoints on risk. While the managers may make choices that have disproportionately negative effects on the owners and workers of the firms they oversee, the shareholders require the information to assess the managers’ performance. These managers could behave selfishly in order to increase their own riches. As a result, there may be a conflict between managers’ personal objectives and those of the company’s shareholders in this so-called “principal–agent relationship.” This situation is modeled as an agency relationship in which shareholders’ inability to control managers’ behavior results in moral hazards, which then increase agency costs (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). By compensating the firm’s agents and controlling their activities with the help of suitable instruments of control, the owners of the company might opt to lessen the conflict of interests (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Agency costs are the expenditures spent by the business as a result of agency disputes. According to the agency hypothesis, there is a rising need for superior auditor services as agency issues become more serious. There are a number of ways the principals may use to evaluate and track the work of their agents while boosting confidence in them in order to align the conflict of interests between the agents and principals. One of the key ways to make sure that management of the firm acts in the interests of the founders is via auditing. Independent auditors’ presence may make management activities more noticeable and allow for behavior monitoring (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). When evaluating the validity of financial accounts supplied by management on behalf of the shareholders, an external auditor plays a critical monitoring function (Watts & Zimmerman, Citation1983). According to research on audit quality, bigger multinational audit firms provide high-quality audit services because they have a greater ability to reduce agency concerns (Davidson & Neu, Citation1993; DeAngelo, Citation1981).

The demand for audit services originates as an outcome of the potential conflicts of interest among the auditees, shareholders, employees and creditors (Watts & Zimmerman, Citation1986). Investors or managers demand auditing to carry out three dimensions of demands: as a monitoring instrument; for information, production to enhance the decisions of investors and instrument to protect against losses from distorted information (Wallace, Citation1980). An auditor plays a significant role in increasing the informational value of financial statements (Beatty, Citation1989). Thus, the higher-quality auditor may decrease the doubts related to the prepared financial statements by companies’ managers Wallace (Citation1980) and signal the quality of the information presented.

The two parts that make up audit quality are determined by the aforementioned metrics. First, an auditor’s ability to see mistakes or abnormalities in a client’s financial reports relates to their competency. Next, an auditor’s objectivity to spot false information is a function of their independence, honesty, and integrity (Watts & Zimmerman, Citation1986). (Menon & Williams, Citation1994). Similar to that, the definition of audit quality is the auditor’s capacity to identify and rule out breaches and fraud in the reported net income (Davidson & Neu, Citation1993). Better auditor effort, which indicates “more assurance, which needs more audit labor,” is how Carcello and Nagy (Citation2004) characterized higher audit quality in relation to other factors. There are several critiques about DeAngelo’s definition of audit quality, despite the fact that it has been often used. DeAngelo’s definition of audit quality includes competence and independence, which are crucial elements of audit quality, but it does not include the complete range of traits, including service quality and responsiveness, which are also vital components of audit quality (Duff, Citation2004). DeAngelo’s definition is lacking in details on the many elements that influence an auditor’s capacity to spot inaccuracies (Francis, Citation2011). There is no unified definition of audit quality, according to Sutton’s (Citation2003) argument, because of the competing roles played by audit market players (external users, auditees, and auditors).

While the quality of audit services lacks explicit and consensual meaning, it is argued that the literature on auditing suggests that the quality of audit services is differentiated (Gul, Citation1999). Yardley et al. (Citation1992) argued that previous studies have measured two related characteristics of the audit service that may vary with the auditor category. The assurance level offered by audit opinion is the first feature, which is a direct consequence of the quality of an audit opinion. The auditor’s opinion is a function of expending effort and expertise by auditors to gather supporting evidence that reflects the truthfulness of the report. The ability of auditors to signal is the second feature of audit product differentiation amongst the sellers of the audit. The company’s managers may select a higher-quality auditor to signal management’s expectations of future cash flows or their honesty. In the same way, DeFond & Zhang (Citation2014) extended the role of the auditor to detect the GAAP and providing assurance of financial reporting quality. As a result, there are different operationalization of audit quality. Many surrogates of audit quality have been used by previous studies, namely: audit firm size, specialist auditor, audit fees and auditor choice. The following section provides these measures of auditor choice.

2.2. Auditor choice

Previous studies have used the reputation of auditor to measure audit quality since audit quality is not directly observable. Numerous studies have documented that auditors who have well-recognized brand-names provide higher audit quality (Palmrose, Citation1986; Shockley, Citation1981). Big 4 audit firms which have an international reputation are viewed as higher audit quality suppliers than non-Big 4 auditors (Ferguson et al., Citation2006). Menon and Williams (Citation1991) introduced the second-tier audit firms to characterize the reputation of the auditor. Both posited reputation: an international reputation for first-tier (Big 4); and national reputation for second-tier (Menon & Williams, Citation1991). It is suggested that the company’s managers are more likely to pay a premium to choose a Big 4 auditor (Menon & Williams, Citation1991).

In addition, the need for assurance is the main driver for audit services (Kane & Velury, Citation2004). The reputation of Big 4 audit firms is relatively greater; so, these firms possess incentives to keep their reputation by producing high-quality audits. Therefore, a potential loss of brand name, auditor’s remuneration and auditee base are incentives for reputational auditors to provide high audit quality (DeAngelo, Citation1981). Moreover, the big 4 auditors have high skills, expertise and broader experience in the different industry sector. Therefore, the big 4 firms are associated with high-quality audits and also reduced the conflict of interest between owners and management by protecting owners’ interest by providing high-quality audits. Moreover, the ability of larger audit firms is more than smaller audit firms in conducting more, often specialized, engagements of varied scope. These audit firms can charge a higher price and tend to be bigger, more proficient and better at maintaining their independence.

There are many factors that may influence the auditor choice but past literature has identified AC characteristics as important factors that may influence the auditor choice (Lisic et al., Citation2019). Whereas, the role of the AC chairman is emphasized in the literature due to its dominant nature (Bajra & Čadež, Citation2018). Literature has also emphasized the characteristics of the AC chairman such as tenure, expertise, ethnicity, qualification and busyness (Baatwah et al., Citation2015; Husnin et al., Citation2016; Johl et al., Citation2012). Consequently, this study has taken AC chairman characteristics as independent variables due to its significance in the past literature. The AC committee’s chairman characteristics are discussed in the sections below.

2.3. Audit committee

AC is made up of AC chairman, finance directors, external and internal auditors and (Spira, Citation1999). According to MCCG (2017), one of the most important fundamental principles is that all members of AC should be comprised of the non-executive directors. This step will improve the process the efficient overseeing the financial reporting process. The Audit Committee members are expected to be financially literate and have sufficient understanding of the company’s business. This would enable them to continuously apply a critical and probing view on the company’s financial reporting process, transactions and other financial information, and effectively challenge management’s assertions on the company’s financials.

2.4. Audit committee chairman

An AC chair who is not the chair of the board, and a size of at least three members (Haka & Chalos, Citation1990). While the role of the chairman is the role of a leader. For example, if a member’s personality is dominant in nature but he lacks the financial reporting abilities, could dominate meeting time, therefore, AC may not work efficiently. In that case, the AC chairman needs to bring the AC back to its main responsibilities. On the other hand, some AC might be heavily dependent on one financial expertise of one member, consequently, other committee members may not be able to resolve the problem (Dezoort, Hermanson, & Reed, Citation2002).

Furthermore, the chairman of the board is not the chairman of the audit committee. The overall efficiency and independence of the Audit Committee must be maintained, according to the Chairman. The independence of the board’s evaluation of the conclusions and recommendations of the Audit Committee may be compromised if the chairman of the board and the chairman of the audit committee are the same person. Overall, it is clear that the chairman’s position is crucial under the new rules. As a result, this research will evaluate how several AC chairman qualities, including tenure, competence, ethnicity, qualification, and activity, affect the choice of auditor. According to earlier study, these are the features that are most crucial (Hansen et al., Citation2019; Lisic et al., Citation2019; Sharma & Iselin, Citation2012; Sultana et al., Citation2015; Tanyi & Smith, Citation2014; Tee & Rassiah, Citation2019; Wan Mohammad et al., Citation2018). Based on earlier research, this study has chosen to analyze these traits in the Malaysian setting.

3. Hypotheses development

3.1. Tenure of chairman of audit committee

The chairman’s term of office is one of AC’s features. The AC chairman must be responsible for and influential in the firm’s misstatement rectification efforts in order to serve as an AC member (Hansen et al., Citation2019). Additionally, the length of the AC’s tenure may affect how successful an AC is by ensuring financial reporting is under control (Pozzoli et al., Citation2022; Rochmah Ika et al., Citation2012). After the first year, the quality of audits for private clients quickly improves, but with time, it degrades (Bell et al., Citation2015).

According to previous research on corporate governance, the AC chair has the position of highest authority inside the company, which denotes a potent source of influence (Sharma et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, compared to other members who do not head any committees, Spira (Citation1999) views the chair of a keyboard committee (such as AC) as a powerful individual. The responsibility of the AC chair includes ensuring the proper flow of information to the AC, as well as open communication between the management and the AC, internal auditors, and external auditors (Tanyi & Smith, Citation2014). Albring et al. (Citation2014) make the case that long-serving independent AC members gain knowledge of the business’s operations, which enables them to manage the financial reporting processes effectively. On the other hand, independent AC members who only work for a short time at the company could not acquire the necessary knowledge to manage the financial reporting process effectively.

The effect of tenure on audit quality has been the subject of several research. Othman et al. (Citation2014), for instance, looked at how AC traits affected voluntary ethical disclosures. The outcome demonstrates that the voluntary ethical disclosure in the companies listed on the Malaysian capital market is only significantly correlated with tenure and numerous directorships. Baatwah et al. (Citation2015) demonstrate a relationship between CEO tenure and the timely submission of the audit report using 339 observations made between 2007 and 2011 on the Muscat Security Market. The CEO’s expertise of the company’s financial reporting systems is significantly improved by tenure. However, Sun et al. (Citation2014) use 75 firms from 2005 to 2007 to evaluate the association between the AC director’s tenure in the USA. The results demonstrate a positive and substantial relationship between the term of AC directors and the likelihood that a corporation would consistently satisfy analyst expectations. Thoopsamut and Jaikengkit (Citation2009) discovered that long-term AC membership results in less earnings management.

The research anticipates that the choice of auditor would be influenced by the personal characteristics of the AC chairman, such as tenure. According to the argument made by agency theory, prolonged tenure may lead to a number of issues, including staleness and entrenchment (Sharma & Iselin, Citation2012). Importantly, two defenses have also been made for the directors’ short service terms. The first argument is that an independent director who needlessly stays in office too long could build a connection with the management and end up being unable to express his opinions on the management’s actions in a way that is sincere and critical (Onyabe et al., Citation2018; Sharma & Iselin, Citation2012). Second, since they can become irrelevant in terms of the company’s future due to their lack of creativity or fresh ideas (Rochmah Ika et al., Citation2012).

Importantly, it has been shown in a number of prior studies that the longer a director has been on the board, the more familiar they are likely to be with the company’s procedures and, as a result, the better equipped they are to safeguard shareholders’ interests and enhance company performance. Similar to this, Thoopsamut and Jaikengkit (Citation2009) contend that a longer tenure for AC members will increase performance and improve monitoring abilities, knowledge, and experience to manage the firm’s operations. Thus, it may be stated that if an AC chairman continues a long time with a company, he would presumably have more knowledge of the company and the quality of the internal monitoring system will be increased, which will lead to the selection of high-quality auditors. This research forecasts the following conclusion based on the reasons made:

H1: There is a significant association among tenure of chairman of AC and auditor choice.

3.2. Audit committee chairman’s ethnicity

The CEO’s ethnicity, the ethnicity of the board chairman, and the dominant board members’ ethnicities make up ethnicity (a stand-in for culture). Examining ethnicity is crucial because it helps us understand how corporations act when members of a specific ethnic group control their organizational structures (Magang, Citation2012).

The multiracial makeup of Malaysia’s business sector, which includes native Malays, Chinese, and Indians, is an intriguing problem. Legally speaking, Malaysia has more compliance with its corporate governance standards because it adheres to common law, which is more stringent than the civil law of its neighboring nations like Thailand and Indonesia (La Porta et al., Citation2000). Ethnic Malays were incorporated as affiliates in Chinese-dominated companies to maintain a balanced economy. Some claim that the Chinese businessmen must give in to this rent-seeking tactic in order to get access to some of the projects since the ethnic Malays will receive some advantages without putting in any genuine labor (Yoshihara, Citation1998; Wan Jan, 2011). The appointment of ethnic Malays to predominantly Chinese-dominated enterprises may be the result of their knowledge and proficiency in the appropriate fields or as a result of their sway over Malaysian political organizations and institutions.

Despite being a diversified society, Malaysia has a sizable ethnic, religious, and linguistic divide. According to Sendut (Citation1991), each ethnic group strives to preserve its ethnic identity, indicating that in heterogeneous countries like Malaysia, the influence of race may be considerable. Therefore, race is used in this research as a stand-in for ethnicity. There are around 22.97 million people living in Malaysia, of which 65% are Bumiputera, 26% are Chinese, 8% are Indians, and 1% are other ethnic groups. In total, 82 percent of Bumiputera, who make up 65 percent of the population, are Malay, while 18 percent are other indigenous groups. Malaysia’s Department of Statistics, 2004. Malay directors make up an average of 38 percent of all directors on the boards of the sample corporations; this number is low when compared to the 53.3 percent of Malay people in Malaysia, who make up the majority of the country’s population. However, of the 100 businesses examined in this research, 47% have a Malay chairwoman, and 53% are made up of people of other ethnicities, mostly Chinese (87 %). As a result, although if the average number of Malay directors on the board is low, if this proportion is reflective of other industries, it implies that over half of the firms in Malaysia are headed by Malay individuals. Since ethnicity matters and previous research have highlighted ethnicity as a crucial factor, it relies on who heads the AC (Tee & Rassiah, Citation2019). It is shown that ethnicity affects the audit quality (Husnin et al., Citation2016; Lai et al., Citation2017). Literature from the past has claimed that ethnicity is significant because there is a connection between the ethnicity of AC members and the external auditor. For instance, the choice of auditor may be influenced if the chairman prefers that the auditor be a Chinese person. The following theory may be formed in light of the considerations mentioned above.

H2: There is a significant association among ethnicity of chairman of AC and auditor choice.

3.3. Expertise of audit committee chairman

Governance regulators from all around the globe have shown a great deal of interest in the AC members who have professional knowledge due to the complexity and nature of financial reporting (Ghafran & Yasmin, Citation2018; Pozzoli et al., Citation2022).

Similar to this, Malaysia’s MCCG (2017) recommends that each member of the AC has sufficient financial understanding. According to agency theory, having members of AC who are knowledgeable in finances increases their capacity to guarantee that the role of the external auditor is performed skillfully (Sultana et al., Citation2015). Expertise in accounting improves the AC’s ability to monitor the financial reporting process (Krishnan & Visvanathan, Citation2008; Abbott et al., Citation2004; Abernathy et al., Citation2015; Sultana et al., Citation2015, Citation2015). A small number of scholars, including Abernathy et al. (Citation2015), Ghafran and Yasmin (Citation2018), and Schmidt and Wilkins (Citation2013), have studied the empirical link between expertise AC chair and audit quality (2013). To carry out their monitoring responsibilities, AC members must put out a lot of work because to the complexity of a firm’s accounting and financial information (He & Yang, Citation2014). According to the agency’s perspective, the presence of members with accounting experience is crucial to boosting the efficacy of monitoring (Abernathy et al., Citation2015; Amin et al., Citation2018), as well as the AC’s capacity to guarantee the external auditor’s job is done professionally (Sultana et al., Citation2015). Additionally, according to resource dependency theory, the skill and knowledge of AC members would enhance their capacity to comprehend financial accounting data and audit conclusions (Sultana et al., Citation2015). In order to increase the monitoring function of AC, accounting knowledge is thus the most effective (Dhaliwal, Naiker, & Navissi, Citation2010).

Additionally, the accounting expertise of the AC members will make financial reporting more efficient, particularly when the AC chair uses it (Abernathy et al., 2014). Therefore, through his direct interactions with the audit partner and the Chief Financial Officer (CFO), the AC chair who has accounting expertise becomes in a better position to comprehend auditor judgments and mediate disputes between external auditors and management (Sultana et al., Citation2015; DeZoort & Salterio, Citation2001). (Baatwah, Salleh, & Stewart, Citation2018). Since he is more likely to be held accountable for financial reporting errors than any other AC member, the AC chairman has the greatest obligation to monitor financial reporting (Schmidt & Wilkins, Citation2012). According to Bromilow (Citation2010), the chairman of the committee serves as the primary conduit between management and internal and external auditors, which influences how successful the AC is (Grange et al., Citation2021; Yosra & TAHARI, Citation2022).

The information, credentials, and experience a member of the audit committee has are referred to as expertise. The primary areas of this knowledge and expertise are accounting, auditing, and finance. Effective AC members can provide the attention, objectivity, and openness needed to oversee the financial reporting process (MCCG, 2017). The capacity of AC to carry out its tasks successfully and efficiently depends on the membership’s degree of aptitude, dedication, expertise, and experience (MCCG, 2017). In 1993, the Malaysian Securities Commission (SC) determined that AC in a firm was essential. As part of Bursa Malaysia’s requirements for the AC, this committee must have three or more members, the majority of whom must be independent directors and at least one of whom must be a member of the Malaysian Institute of Accountants (MIA) or possess sufficient training and experience in accounting to qualify as financially literate.

According to MCCG (2017), all AC members should understand the firm’s operations and be financially educated. As a result, AC members will be able to apply a critical viewpoint to the firm’s transactions, the financial reporting process, and other data. They will be able to challenge the manager’s claims on the company’s financials as a result. According to MCCG (2017), one of the key responsibilities of the AC is to examine the financial statements of the firm and provide comments about whether they accurately reflect the company’s performance and financial status. Financial literacy is defined as the capacity to read and grasp financial statements and reports, to comprehend and appreciate the application of accounting standards, and to effectively criticize and query the firm’s risk management and internal control practices (Malaysia, 2009).

In order to assure the preservation of shareholders’ interests, Abbott and Parker (Citation2000) define an effective AC as a committee that includes members with significant resources, authority, and expertise. By ensuring effective internal controls, controlling risks, and ensuring the caliber of financial reporting while performing its oversight responsibilities, the AC may successfully protect the interests of shareholders. Therefore, as the head of AC, the chairman will better understand the process of financial reporting and how the choice of qualified auditors contributes to better serving the interests of the owners if he has previous audit expertise. As a result, the chairman’s expertise will help in making the choice of the auditor’s kind. The following theory may be formed in light of the considerations mentioned above.

H3: There is a significant association between expertise of chairman of AC and auditor choice.

3.4. Audit committee chairman’s qualifications

The academic (undergraduate or postgraduate) and professional credentials of the members of the audit committee include membership in organizations like ACCA, CPA America, or CPA Australia. Additionally, important for AC members to have specific academic and professional credentials in order to successfully perform their tasks. According to Bursa Malaysia, the AC must include at least one member who is a member of the Malaysian Institute of Accountants (MIA) or who has a professional certification in accounting or auditing, such as the ACCA or CPA. Those AC members who are familiar with accounting or auditing, according to Hayes (Citation2014), favor lowering earnings management methods as a stand-in for anomalous accruals. Additionally, Hay (Citation2013) discovered that AC members with accounting degrees are regarded as financial specialists and as a result, they support restrict earnings management. Wan Mohammad et al. (Citation2018) and Lisic et al. (Citation2019) discovered a negative and substantial relationship between the financial report’s restatements and an AC that has at least one member with academic or professional degrees in accounting or auditing. Their research explains that these members are able to comprehend and identify the financial statements, auditing concerns, and dangers before making suggestions to mitigate these problems. Yatim et al. (Citation2006) did not discover a connection between the credentials of AC members and financial reporting restatements. This outcome might be explained by the fact that the research was looked at in 2000 (before the establishment of SOX act). Another factor might be the tiny sample size, which included just 106 US enterprises over the course of a year.

In the context of external audit, Vafeas and Waegelein (Citation2007) discovered a favorable relationship between the quality of the external audit and an AC that includes one member with a qualification in accounting or auditing. One explanation is that more assurance requests result in higher audit quality. Additionally, Yasin and Nelson (Citation2012) discovered a favorable correlation between postgraduate-trained AC members and the quality of external audits. Salleh, Baatwah, and Ahmad (Citation2017) could not find any correlation between audit report latency and the academic or professional backgrounds of AC members. They asserted that if AC independence is present, this component is related to a shorter audit report latency. Prior studies discovered a correlation between fewer asset thefts and the presence of AC members having accounting or auditing credentials (Mustafa & Ben Youssef, Citation2010). As was indicated above in this section, prior research often investigates AC competence as a generic term in various circumstances. This research aims to establish a relationship between internal audit budget and the qualifications of AC members. You may approach this from two distinct angles. Members of the audit committee with backgrounds in accounting or auditing are more knowledgeable about internal controls and risk management, so they need less confidence from internal audit. According to a different viewpoint, AC members who meet these requirements want greater internal control and so need more assurance from the internal audit department.

Because of this, if the chairman of the AC has a foreign degree, he has a greater understanding of the value of selecting excellent auditors to provide excellent financial reporting quality. The foreign certification would thus motivate him to enhance auditor choice diction. The following theory may be formed in light of the considerations mentioned above.

H4: There is a significant association among qualification of chairman of AC and auditor choice.

3.5. Audit committee chairman busyness

The issue of the directors’ “busyness” is quite serious since there is a great deal of doubt over their capacity to carry out their duties with diligence (Tanyi & Smith, Citation2014). Additionally, it is normal to have many directorships while serving on numerous board committees, such as the audit and pay committees (i.e., overlapping board committee memberships). Therefore, one may argue that “busyness” is related to having several directorships at different companies as well as concurrent board committee memberships at the same business.

The Corporate Governance Blueprint, which details the regulator’s strategic objectives for achieving excellence in corporate governance in the context of Malaysia, was released by the Securities Commission of Malaysia in 2011. The Securities Commission (2011) has also expressed concern about how the tasks of directors have significantly expanded as a result of recent corporate changes, making their responsibilities even more onerous than before. For busy directors, it may be challenging to commit adequate time and attention to carrying out their fiduciary obligations diligently due to many board positions. Additionally, it has been noticed that some of the directors in Malaysia have faced increasingly severe enforcement actions over the years as a result of their extreme devotion as well as lack of focus and attention (Securities Commission, 2011).

According to Malaysia’s Bursa Listing Requirements, a director was not allowed to have more than 10 directorships in publicly listed companies before to 2013. Less than 1% of directors, according to the Securities Commission (2011), hold more than five directorships. The Securities Commission asserts that the issue is not the quantity of directorships held, but rather the qualifications and commitment of each director. The regulator has thus advised that before assuming new directorships at another listed business, each director seek approval from their respective boards.

In the context of an increase in accounting scandals, authorities have begun to pay attention to one of the contemporary corporate governance issues: director busyness (Tanyi & Smith, Citation2014). Directors’ failure to dedicate the required time and attention to their oversight obligations might negatively affect the company’s success (Shivdasani & Yermack, Citation1999). This group argues that busy, overcommitted directors suffer with not having the time to diligently perform their fiduciary duties. For instance, Fich and Shivdasani (Citation2006) showed that businesses’ market-to-book value and profitability were lower when at least 50% of its board members had more than two directorships using samples from the Forbes 500.

Another study employing companies listed on the Zurich Stock Exchange discovered a negative relationship between the worth of the firm and the average number of directorships held by busy directors (Tobin’s Q; Loderer & Peyer, Citation2002). Similar findings from another study by Falato, Kadyrzhanova, and Lel using data from US firms from 1988 to 2007 support the “Busyness Hypotheses” (2014). According to the studies described above, overworked directors and boards negatively affect the efficiency of their supervision, which in turn decreases shareholders’ value. The “Busyness Hypotheses” are supported by further research by Lin and Liu (Citation2009), which shows that less-busy boards are associated with better internal governance and resource allocation. As a result, several studies have shown that overburdened directors and boards of directors are ineffective monitors.

One of the negative consequences of busy directors has been connected to lower shareholder wealth (Busyness Hypotheses; Ahn et al., Citation2010). Multiple directorships are viewed as a sign of a good reputation under the “Reputation Hypothesis,” which is the opposing line of inquiry. Low firm performance and firm value (Jackling & Johl, Citation2009), poor firm attendance at board meetings (Jiraporn et al., Citation2009), and high probability of financial reporting fraud. The reputational benefit and recognition that come with holding several directorships enable these directors to fully use their knowledge and experience while upholding their fiduciary duties. Numerous studies have found evidence to support the “Reputation Hypothesis.” Consider a 1995 sample of 3,190 US firms as an illustration.

Busy directors may greatly increase a company’s value in mergers and acquisitions and are thus not detrimental to shareholders, argue Payne et al. (Citation2009). Based on 1,049 sample firms in the US from 1997 to 2008, the authors also assert that restricting multiple directorships among directors is not always in the best interests of shareholders. Di Pietra et al. (Citation2008) discovered in a different study based on the Italian business environment that busy directors tend to be well associated with respectable corporate reputation and as a consequence have a significant and advantageous impact on enterprises’ market performance. This research is based on 71 publicly listed companies in Italy from 1993 to 2000, where the market is characterized by family, concentrated ownership, and minimal legislative protection for investors, mirroring characteristics of emerging markets, such as those in Asian countries.

According to a research by Lei and Lam (Citation2013), based on 2,953 independent directors from 611 Hong Kong listed companies, independent directors who hold numerous directorships increase the value of the companies and are generally more advantageous than disadvantageous. The “Reputation Hypothesis” is supported by yet another research that is focused on developing markets.

Studies on Malaysian firms dealing with multiple directorships are few and far between. Kamardin and Haron (Citation2011) provide evidence that the practice of several non-executive directorships in listed corporations has a detrimental impact on the supervision responsibilities. They thus compel authorities to monitor this behavior carefully. However, Hashim and Rahman (Citation2011) conducted a different study based on 554 firm-years in 2003 and 2004 and concluded that having more board appointments is associated with higher earnings quality. They also advocate careful board oversight in order to take advantage of the knowledge, experience, and skills gained from other board appointments. In contrast, a more recent study by Latif et al. (Citation2013) emphasizes the implications for the monitoring roles carried out by 1,023 directors of listed companies in Malaysia for the year 2008 and shows that directors who hold multiple directorships are more likely to miss board meetings. In terms of monitoring effectiveness, there are several noteworthy data that demonstrate both the benefits and drawbacks of having many directorships. However, empirical research is still unreliable and seldom ever released in relation to the Malaysian market. Sharma and Iselin (Citation2012) and Bajra and Čadež (Citation2018) both claim that there is still much to be determined about the influence of busy directors based on empirical evidence.

Regardless of the chairman’s other attributes, the audit’s quality will suffer if he is too busy to efficiently oversee the monitoring process. This issue will create a conflict of interest and prohibit the publication of the inaccurate financial results due to the activity. The chairman will be too busy to focus on every company; therefore, he could make a concession regarding the choice of the auditor. This will raise the probability that additional AC members or senior executive directors will put ownership-establishing tactics into action. As a consequence, he could settle on the auditors’ selection in an effort to hide his busyness-related irresponsibility. In light of the aforementioned factors, the following hypothesis may be developed.

H5: There is a significant relationship between busyness of chairman of AC and auditor choice.

4. Research design

4.1. Conceptual framework

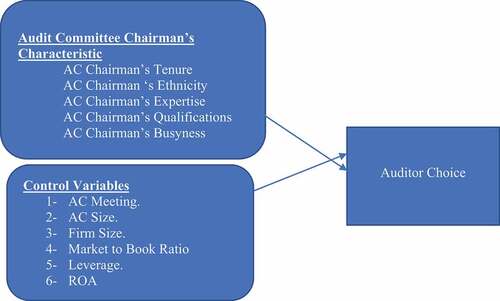

Consequently, AC’s chairman tenure, ethnicity, expertise, qualification are the strong determinants of the auditor choice. As shown in Figure , this study views AC’s chairman tenure, ethnicity, expertise, qualification influences the auditor choice.

4.2. Measurement of variables

The measurement of the variables connected to the hypotheses is explained in this section. It explains in detail how control, moderating, independent, and dependent variables are operationalized is mentioned in Table .

Table 1. Measurement and abbreviation of variables

4.3. Sample selection and unit analysis

This study utilizes the public listed company (PLC) as the unit of analysis. There are multiple benefits of choosing PLC compared to the non-listed company. First, accounts of PLCs are audited by an external auditor that increases the reliability of the data. Second, the application of MFRS is compulsory for PLCs, and this results in the uniformity of the financial statement data, hence making comparison easy with the previous Malaysian studies with similar samples. Third, PLCs have multiple stakeholders compared to non-listed firms (e.g., controlling shareholders, minority shareholders, creditors, employees and state agencies). In the case of business failures due to concealing the actual economic performance by managers, it will affect all the stakeholders (e.g., Enron, Pascanova and Transmile). The sample of the study comprises all listed firms on Bursa Malaysia ACE market (secondary market) for the year 2018. This study is based on the firms that have full coverage of data for the year 2018. The reason for taking ACE market is that the prior literature has focused mainly on the main market and this area is ignored in the extant literature and Ace market is growing in Malaysia and public interest is also growing as well. Moreover, the sample period is based on 2018 because that is the most recent data available. Table explains the process of sample selection.

Table 2. Sample

Initially, all companies listed on the ACE market as on 31 December 2018 were identified. There was a total of 122 listed firms as of 31 December 2018. The 11 firms were omitted because of non-availability of data on variables, such as auditor choice and AC characteristics, and the final sample is based on 111 firms.

4.4. Methodology

This study proposes that AC characteristics have a significant association with auditor choice Therefore, the baseline regression equation is given below in following Equation:

Where; AUDCit = auditor choice; ACTEN = Tenure of Audit Committee Chairman; ETH = Audit Committee Chairman Ethnicity; ACEXP = Chairman of Audit committee Expertise; ACQUL = Audit Committee’s Chairman’s Qualification; ACCBUS = Audit Committee’s Chairman’s busyness; ACM = Audit Committee Meetings; ACSIZE = Audit committee size; FSIZE = firm size; LEV = leverage; ROA = Return on Total; MTB = The market-to-book ratio.

5. Empirical result

5.1. Descriptive statistics

Table presents the distribution of firms among industry sectors on the basis of Bursa Malaysia’s classification. The highest concentration lies in the Technology (42.34%) followed by Industrial Products/Services (20.72%), Consumer Products (12.61%) and Telecom and Media (11.712%), and the lowest is Construction and Transportation & Logistic (2.70%).

Table 3. Industry category

5.2. Normality

The data should be derived from regularly distributed populations, which is one of the basic presumptions of the ordinary least square regression (OLS). It is assumed that the residuals distribution should be random, normal, and zero mean (Gujarati, Citation2003). Descriptive statistics were thus computed for all the variables utilized in this investigation before the models’ estimate. The results in Table show that the mean values of the dichotomous variables ACTEN, ETH, ACEXP, and ACQUL are 0.414414, 0.189189, 0.558559, and 0.486487, respectively, out of a maximum value of 1. The mean values of AUDC and AUDC1 are 0.351351 and 0.864865, respectively, out of a maximum value of 1. The mean values of the continuous variables ACCBUS, ACM, ACSIZE, FSIZE, LEV, ROA, and MTB are respectively 2.864865, 4.90991, 6.558559, 11.3638, .107361, −0.1888, and 1.01959. Kurtosis and skewness values for the normal data should, according to Greene (Citation2012) and Gujarati (Citation2003), be between +3 and −3. It emphasizes that all variables are normally distributed, with the exception of LEV, ROA, and MTB, based on the actual values of skewness and kurtosis.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of variables

It should be highlighted that the outliers in the data are authentic and came from trustworthy sources (e.g., Thomson Reuters Database and Annual Reports). In addition, Hair et al. (Citation2010) noted that if outliers are eliminated from the data, generalizability of the findings may be constrained. To ensure generalizability to the whole population, it may not be necessary to eliminate the outliers of certain variables from the sample. Outliers were left in the dataset due to the aforementioned defenses. Heteroskedasticity is one of the effects of non-normal data, according to Gujarati (Citation2003), and it has to be managed. Additionally, researchers may depend on the central limit theorem, which states that if the sample size is bigger than 30, the sampling distribution of any statistic will be normal.

According to Greene (Citation2012), normalcy is sometimes seen as unneeded and inappropriate for regression analysis. While normality will allow for the generation of many precise statistical findings, it is not essential to get many outcomes using multivariate regression analysis. Aside from situations when a different distribution is expressly assumed, it also aids in the generation of confidence intervals and t-statistics. A big sample offers a trustworthy foundation for statistical findings in the regression analysis under broad assumptions about the methodology used to create the sample data (Greene, Citation2012). The study is thus based on non-normal data.

5.3. Multicollinearity

For each variable, a Pearson correlation analysis was performed. According to the results shown in Table , the dependent variable, AUDC, significantly positively correlates with the independent variables ACTEN (r = 0.2619), ETH (r = 0.0300), and ACEXP (r = 0.0082), while the dependent variable, AUDC, negatively correlates with both ACQUL and ACCBUS (r = −0.1122 and r = −0.1628, respectively). The data also suggest that LEV and FSIZE have the greatest correlation between independent variables, as measured by the correlation coefficient (r = 0.4174), indicating that there is a problem with multicollinearity between these two variables. According to Gujarati (Citation2003) and Hair et al. (Citation2006), multicollinearity may be disregarded in OLS regression if its value is less than 0.8.

Table 5. Correlation matrix

Multicollinearity issue may be investigated further through tolerance value (TV) and the variance inflation factor (VIF). VIF and TV were computed for all variables in Models. The results are presented in Table . There is an absence of multicollinearity as TV and VIF values are less than .1 and 10, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2006; O’brien, Citation2007). As shown in Table 4.3, VIF and TV of all independent variables are lower than 10 and .1, respectively; therefore, the existence of multicollinearity is not in the model.

Table 6. Variance inflation factor and tolerance value

6. Multivariate regression analysis

This study uses logistic regression for the multivariate analysis because the dependent variable is auditor choice this measured as a dichotomous variable. Therefore, it is suggested that the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable then it is preferable to use logistic regression. Many of the past studies used the dichotomous regression when the dependent variable was measured as dichotomous variable (Guedhami et al., Citation2014; Hope et al., Citation2008; Hsu et al., Citation2015; Knechel et al., Citation2008; Lin & Liu, Citation2009; Wang et al., Citation2008). The results of multivariate regression analysis for logistic regression for the non-directional hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 are given below in Table . The hypotheses state that AC characteristics have a significant relationship with the auditor choice. The R2 is 16.38%, independent variables, ACTEN, ETH, ACEXP, ACQUL and ACCBUS explain 16.38% variation towards the dependent variable auditor choice.

Table 7. Relationship between audit committee chairman’s characteristics between auditor choice

The results of the regression found a significantly positive relationship among ACTEN and auditor choice (β = 1.266997, p < 0.01), supporting H1. This result confirms the significance of tenure of chairman of AC for the auditor choice. It also shows that if the chairman of AC stays a long time, these firms select the big 4 firm for auditing. The main reason behind is that when the tenure is long the chairman understands the operations of the firms deeply and also understand the role of big 4 audit firms to protect the owner’s interest. Therefore, this result is also in line with the alignment hypotheses of agency theory because it shows that conflict of interest between owner and managers are very low in the firms because long tenure gives the chairman expertise to protects the interest of the owners, consequently, these firms hire big 4 auditors for the audit of the firm. These results are also in line with the previous studies, that argued that the long tenure of chairman improves the monitoring mechanism that demand the big 4 auditors to improve the financial reporting process including Malaysian studies (Abbott & Parker, Citation2000; Bliss et al., Citation2007; Che Ahmad et al., Citation2006; He et al., Citation2017; Lai et al., Citation2017; Quick et al., Citation2018; Suryanto et al., Citation2017).

The association among ETH and AUDC is positive but insignificant (β = 0.136751, p > 0.10), rejecting H2. This result demonstrates that the ethnicity of the AC chairman has no influence on the auditor choice. The association among AUDEXP and AUDC is positive but insignificant (β = 0.194105, p > 0.10), rejecting H3. This result demonstrates that the AC chairman expertise has no influence on the auditor choice. The association among ACQUL and AUDC is negative but insignificant (β = −0.58007, p > 0.10), rejecting H4. This result demonstrates that the AC chairman audit experience has no influence on the auditor choice. The three main characteristics of the chairman of AC are insignificant, these results are not in line with the prior studies (Asmuni et al., Citation2015; Che Ahmad et al., Citation2006; Husnin et al., Citation2016; Nazatul Faiza Syed Mustapha Nazri et al., Citation2012; Olowookere & Inneh, Citation2016). The main reason behind this insignificance is the sample period and sample size because previous studies were based on the old data and this study is based on the recent data and moreover, the prior studies were conducted on the main stock market firm, whereas, the ACE market firms are not developed like the main market firms. Another plausible reason may the proxy of audit quality, some studies used other proxies, that is also a cause of different findings as compared to the current study.

The association among ACBUS and AUDC is negative and significant (β = −0.93828, p < 0.05), accepting H5. This result demonstrates that the AC chairman busyness has a negative and significant influence on the auditor choice. The reason behind this negative influence is that the more the chairman is busy, he does not have enough time to cater to the interest of every firm. So, this result is in line with the entrancement hypotheses of agency theory because when the chairman of AC is very busy he will be unable to protect the interest of owners, that will lead to high conflict of interest between owner and manager and wealth of the owners can be entrenched (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Morck et al., Citation1988).

7. Further analysis and robustness checks

The results of multivariate regression analysis for logistic regression for the non-directional hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 based on the alternative definition of auditor choice are given below in Table . In this analysis, the alternative definition of auditor choice is based on the international audit firm (AUDC1) vs local firms, where, the audit firm is international is considered as 1, otherwise 0. The R2 is 16.10%, independent variables, ACTEN, ETH, ACEXP, ACQUL and ACCBUS explain 16.10% variation towards the alternative definition of dependent variable auditor choice explained in Table .

Table 8. Relationship between audit committee chairman’s characteristics between auditor choice based on alternative definition

The results of the regression found a significantly positive relationship among ACTEN and auditor choice (β = 0.73157, p > 0.10), rejecting H1. The association among ETH and AUDC is positive but insignificant (β = 1.517211, p > 0.10), rejecting H2. The association among AUDEXP and AUDC is positive and significant (β = .608052, p < 0.05), accepting H3. The association among ACQUL and AUDC is positive but insignificant (β = −0.463218, p > 0.10), rejecting H4. The association among ACQUL and AUDC is negative but insignificant (β = −0.04012, p > 0.10), rejecting H5. These results are different from the model based on the primary definition of auditor choice, only one hypothesis is significant, i.e., H3 but this was not significant in the model based on the original definition of auditor choice. The main reason behind is that the quality of the audit of the international firms are different from the local firms, despite the fact that these big 4 firms are also international firms, but their quality is different from other international firms.

8. Implications of the study

This study offers several significant implications for agency theory. Previous research has focused mainly on main market firms that are always in the public eye and ignore the ACE market that is growing. This study considers most of AC’s chairman’s together, that was ignored in the extant literature. This study provided evidence that chairman’s tenure and busyness have implication for the agency theory that can create the conflict of interest between owners and managers and ultimately the choice of auditors that is a significant contribution to agency theory. In this study, the implications for policymakers also stem from the role of chairman’s characteristics especially busyness because it shows that busyness results in the choice of low-quality auditors. Therefore, policymakers, especially the Bursa Malaysia, should focus on this trend to understand the reason behind the busyness and should limit the chairing rule of chairman to the certain number of firms at a time improve the process of monitoring especially financial reporting process.

9. Conclusion, limitations of the study and future research directions

Overall the findings suggested that in general some attributes of the AC’s chairman influence the auditor choice, especially tenure influence positively and busyness negatively. However, other attributes such as expertise, qualification and ethnicity do not influence the auditor choice in the Malaysian context due to the fact that ACE market the AC structure is not well developed like the firm in the main market. This study also offers valuable implications for the policymakers to improve the structure of AC in the ACE market. This study also provides some exclusive directions for future research. Future studies may look at the notion in other nations. Applying the theoretical model to private enterprises might make a substantial contribution since the study could be expanded to private firms. Due to the lack of openness in private markets compared to highly regulated markets, the connections discovered in this research may be dramatically different for private enterprises.

The study’s limitations are listed in this part, along with an analysis of how they affected the findings and the conclusions that were reached as a consequence. Malaysia is the study’s focus area. A disparity in institutional and legal environments, however, may prevent the conclusions of this research from generalizing to other emerging countries, such as Indonesia and Thailand. The chairman of AC’s term and level of activity are the only factors found in this analysis to be statistically significant. The Malaysian setting supports these findings. Because of the variations in AC composition and practice, the findings may not be relevant to other emerging nations.

The removal of major and leap market enterprises from the sample is one example of how this research exhibits survival bias. Variable validity is another drawback of this research. Relationships between factors, such as the qualities of AC’s chairman and the choice of auditor, are shown in the conceptual framework of the research. In order to increase variable validity, the measures utilized to operationalize the variables are based on prior work. However, the factors utilized in earlier studies may not by themselves ensure their validity. Since audit quality cannot be consistently measured, this research simply considered the choice of auditor. Several directions for further investigation are provided by the conceptual framework of this study and its findings. First, it should be beneficial to evaluate the study’s conceptual framework in nations with various corporate governance and AC systems. This will also aid in overcoming the study’s shortcomings. Future scholars may make major contributions by determining if the suggested link holds true in other nations. In particular, it would be crucial to look at nations with less established markets and weaker legal systems than Malaysia. Additionally, PLCs served as the study’s sample. Applying the theoretical model to private enterprises might make a substantial impact since private firms control the majority of businesses worldwide. Because private markets are less transparent than highly regulated markets, the connections discovered in this research may alter dramatically for private enterprises.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, L. J., & Parker, S. (2000). Auditor selection and audit committee characteristics. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 19(2), 47–26. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2000.19.2.47

- Abbott, L. J., Parker, S., & Peters, G. F. (2004). Audit committee characteristics and restatements. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 23(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2004.23.1.69

- Abernathy, J. L., Beyer, B., Masli, A., & Stefaniak, C. M. (2015). How the source of audit committee accounting expertise influences financial reporting timeliness. Current Issues in Auditing, 9(1), 1–9.

- Ahmadpour, A., & Amin Hadiyan, S. (2015). Changes in the value relevance of accounting information and identifying the factors affecting the value relevance. The Iranian Accounting and Auditing Review, 22(1), 1–20.

- Ahn, S., Jiraporn, P., & Kim, Y. S. (2010). Multiple directorships and acquirer returns. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(9), 2011–2026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.01.009

- Al‐Matari, E. M. (2021). The determinants of bank profitability of GCC: The role of bank liquidity as moderating variable—further analysis. International Journal of Finance & Economics. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2485

- Al-Absy, M. S. M., Ismail, K. N. I. K., & Chandren, S. (2018). Accounting expertise in the audit committee and earnings management. Business & Economic Horizons, 14(3), 451–476. https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2018.33

- Albring, S., Robinson, D., & Robinson, M. (2014). Audit committee financial expertise, corporate governance, and the voluntary switch from auditor-provided to non-auditor-provided tax services. Advances in Accounting, 30(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2013.12.007

- Alfraih, M. M., & Gale, C. S. (2016). The role of audit quality in firm valuation: Evidence from an emerging capital market with a joint audit requirement. International Journal of Law and Management, 58(5), 575–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-09-2015-0049

- Al-Homaidi, E. A., Al-Matari, E. M., Anagreh, S., Tabash, M. I., & Senan, N. A. M. (2021). The relationship between zakat disclosures and Islamic banking performance: Evidence from Yemen. Banks and Bank Systems, 16(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.16(1).2021.05

- Al-Homaidi, E. A., Al-Matari, E. M., Tabash, M. I., Khaled, A. S., & Senan, N. A. M. (2021). The influence of corporate governance characteristics on profitability of Indian firms: An empirical investigation of firms listed on Bombay stock exchange. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 18(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.21511/imfi.18(1).2021.10

- Al-Matari, E. M. (2019). Do characteristics of the board of directors and top executives have an effect on corporate performance among the financial sector? Evidence using stock. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20(1), 16–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-11-2018-0358

- Al-Matari, E. M. (2022). Do corporate governance and top management team diversity have a financial impact among financial sector? A further analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2141093. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2141093

- Al-Matari, E. M., & Alosaimi, M. H. (2022). the role of women on board of directors and firm performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia financial market. Corporate Governance and Organizational Behavior Review, 6(3), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.22495/cgobrv6i3p4

- Al-Matari, E. M., Al-Swidi, A. K., & Fadzil, F. H. (2014a). The effect of board of directors characteristics, audit committee characteristics and executive committee characteristics on firm performance in Oman: An empirical study. Asian Social Science, 10(11), 149–171.

- Al-Matari, E. M., Al-Swidi, A. K., & Fadzil, F. H. B. (2014b). Audit committee characteristics and executive committee characteristics and firm performance in Oman: Empirical study. Asian Social Science, 10(12), 98.

- Al-Matari, Y. A., Al-Swidi, A. K., Fadzil, F. H. B. H., & Al-Matari, E. M. (2012). Board of directors, audit committee characteristics and the performance of Saudi Arabia listed companies. International Review of Management and Marketing, 2(4), 241–251.

- Al Matari, E. M., & Mgammal, M. H. (2019). The moderating effect of internal audit on the relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and corporate performance among Saudi Arabia listed companies. Contaduría y administración, 64(4), 9. https://doi.org/10.22201/fca.24488410e.2020.2316

- Al-Matari, E. M., Mgammal, M. H., Alosaimi, M. H., Alruwaili, T. F., & Al-Bogami, S. (2022). Fintech, board of directors and corporate performance in Saudi Arabia financial sector: Empirical study. Sustainability, 14(17), 10750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710750

- Al-Murisi, A. L. S. M., Ahmed, A. S., & Adon, I. (1997). Audit committees in Malaysia: patterns of establishment and characteristics.

- Al-Sayani, Y. M., Mohamad Nor, M. N., Amran, N. A., & Ntim, C. G. (2020). The influence of audit committee characteristics on impression management in chairman statement: Evidence from Malaysia. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1774250. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1774250

- Amin, A., Lukviarman, N., Suhardjanto, D., & Setiany, E. (2018). Audit committee characteristics and audit-earnings quality: Empirical evidence of the company with concentrated ownership. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 7, 18–33.

- Asmuni, A., Nawawi, A., & Salin, A. (2015). Ownership structure and auditor’s ethnicity of Malaysian public listed companies. Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 23(3), 603–622.

- Ayadi, W. M., & Boujelbene, Y. (2015). Internal governance mechanisms and value relevance of accounting earnings: An empirical study in the French context. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, 7(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMFA.2015.067512

- Azmi, N. A., Samat, O., Zakaria, N. B., & Yusof, M. A. M. (2013). Audit committee attributes on audit fees: The impact of Malaysian Code of Corporate Governance (MCCG) 2007. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 9(11), 1442–1453.

- Baatwah, S. R., Ahmad, N., & Salleh, Z. (2018). Audit committee financial expertise and financial reporting timeliness in emerging market: Does audit committee chair matter?. Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting, 10(4), 63–85.

- Baatwah, S. R., Salleh, Z., & Ahmad, N. (2015). CEO characteristics and audit report timeliness: Do CEO tenure and financial expertise matter? Managerial Auditing Journal, 30(8/9), 998–1022. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-09-2014-1097

- Bajra, U., & Čadež, S. (2018). Audit committees and financial reporting quality: The 8th EU company law directive perspective. Economic Systems, 42(1), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2017.03.002

- Beatty, R. P. (1989). Auditor reputation and the pricing of initial public offeri. The Accounting Review, 64(4), 693.

- Bell, T. B., Causholli, M., & Knechel, W. R. (2015). Audit firm tenure, non‐audit services, and internal assessments of audit quality. Journal of Accounting Research, 53(3), 461–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12078

- Bliss, M. A., Muniandy, B., & Majid, A. (2007). CEO duality, audit committee effectiveness and audit risks: A study of the Malaysian market. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(7), 716–728. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900710772609

- Bromilow, C. 2010. Congratulations, you’re the audit committee chair. Now what? Available at: http://www.directorship.com/catherine-bromilow-audit-committee-chair/

- Carcello, J. V., & Nagy, A. L. (2004). Client size, auditor specialization and fraudulent financial reporting. Managerial Auditing Journal, 19(5), 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900410537775

- Carcello, J. V., & Neal, T. L. (2000). Audit committee composition and auditor reporting. The Accounting Review, 75(4), 453–467. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2000.75.4.453

- Cascino, S., Pugliese, A., Mussolino, D., & Sansone, C. (2010). The influence of family ownership on the quality of accounting information. Family Business Review, 23(3), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486510374302

- Chalos, P., & Haka, S. (1990). Transfer pricing under bilateral bargaining. 624–641.

- Che Ahmad, A., Houghton, K. A., Zalina Mohamad Yusof, N., & Haniffa, R. (2006). The Malaysian market for audit services: Ethnicity, multinational companies and auditor choice. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(7), 702–723. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900610680503

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Lang, L. H. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00067-2

- Clarke, T. (2004). Cycles of crisis and regulation: The enduring agency and stewardship problems of corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 12(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2004.00354.x

- Cleassens, S., Fan, J. P., Djankov, S., & Lang Larry, H. (2000). Expropriation of Minority Shareholders in East Asia. Institute of Economic Research Hitotsubashi University.

- Collins, D. W., Maydew, E. L., & Weiss, I. S. (1997). Changes in the value-relevance of earnings and book values over the past forty years. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24(1), 39–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(97)00015-3

- Darussamin, A. M., Ali, M. M., Ghani, E. K., & Gunardi, A. (2018). The effect of corporate governance mechanisms on level of risk disclosure: Evidence from Malaysian government linked companies. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 21(1), 1–19.

- Davidson, R. A., & Neu, D. (1993). A note on the association between audit firm size and audit quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 9(2), 479–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1993.tb00893.x

- DeAngelo, L. E. (1981). Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(81)90002-1

- DeFond, M., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2), 275–326.

- DeZoort, F. T., Hermanson, D. R., Archambeault, D. S., & Reed, S. A. (2002). Audit committee effectiveness: A synthesis of the empirical audit committee literature. Audit Committee Effectiveness: A Synthesis of the Empirical Audit Committee Literature, 21, 38.

- DeZoort, F. T., & Salterio, S. E. (2001). The effects of corporate governance experience and financial‐reporting and audit knowledge on audit committee members' judgments. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 20(2), 31–47.

- Dhaliwal, D. A. N., Naiker, V. I. C., & Navissi, F. (2010). The association between accruals quality and the characteristics of accounting experts and mix of expertise on audit committees. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(3), 787–827.

- Di Pietra, R., Grambovas, C. A., Raonic, I., & Riccaboni, A. (2008). The effects of board size and ‘busy’directors on the market value of Italian companies. Journal of Management & Governance, 12(1), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-008-9044-y

- Duff, A. (2004). Auditqual: Dimensions of audit quality. Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland Edinburgh.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/258191

- Endrawes, M., Feng, Z., Lu, M., & Shan, Y. (2020). Audit committee characteristics and financial statement comparability. Accounting & Finance, 60(3), 2361–2395. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12354

- Falato, A., Kadyrzhanova, D., & Lel, U. (2014). Distracted directors: Does board busyness hurt shareholder value? Journal of Financial Economics, 113(3), 404–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.05.005

- Faleye, O., & Krishnan, K. (2017). Risky lending: Does bank corporate governance matter? Journal of Banking & Finance, 83, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.06.011

- Fariha, R., Hossain, M. M., & Ghosh, R. (2021). Board characteristics, audit committee attributes and firm performance: Empirical evidence from emerging economy. Asian Journal of Accounting Research.

- Fatima, H., Nafees, B., & Ahmad, N. (2018). Value relevance of reporting of accounting information and corporate governance practices: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Paradigms, 12(1), 88–93.

- Ferguson, A. C., Francis, J. R., & Stokes, D. J. (2006). What matters in audit pricing: Industry specialization or overall market leadership? Accounting & Finance, 46(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.2005.00152.x

- Fich, E. M., & Shivdasani, A. (2006). Are busy boards effective monitors? The Journal of Finance, 61(2), 689–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00852.x

- Francis, J. R. (2011). A framework for understanding and researching audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(2), 125–152. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50006

- Germain, L., Galy, N., & Lee, W. (2014). Corporate governance reform in Malaysia: Board size, independence and monitoring. Journal of Economics and Business, 75, 126–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2014.06.003

- Ghafran, C., & Yasmin, S. (2018). Audit committee chair and financial reporting timeliness: A focus on financial, experiential and monitoring expertise. International Journal of Auditing, 22(1), 13–24.

- Ghayoumi, A. F., Nayeri, M. D., Ansari, M., & Raeesi, T. (2011). Value Relevance of accounting information: Evidence from Iranian emerging stock exchange. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 5(6), 830–835.

- Grange, M. L., Ackers, B., & Odendaal, E. (2021). The impact of the characteristics of audit committee members on audit committee effectiveness. Global Business and Economics Review, 24(4), 409–434. https://doi.org/10.1504/GBER.2021.115812

- Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric analysis (7 ed.). Pearson.

- Guedhami, O., Pittman, J. A., & Saffar, W. (2014). Auditor choice in politically connected firms. Journal of Accounting Research, 52(1), 107–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12032

- Gujarati, D. (2003). Basic Econometrics (4th ed.). McGraw Hill.

- Gul, F. A. (1999). Audit prices, product differentiation and economic equilibrium. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 18(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.1999.18.1.90