?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Large and medium-scale manufacturing industries undoubtedly bring an unprecedented human and environmental crisis. To overcome these negative effects, governments provide regulatory frameworks that entrench businesses actively involve in social responsibilities where they are operating. The goal of this study was to look at the scope and levels of corporate social responsibility for local community development from the perspective of social and economic responsibility. A total of 401 local communities living near industry were selected proportionally from four Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region zones, and Hawassa city in the Sidama Region. Quantitative data was collected from local communities and interviews with government officials and focus groups with members of the local community were also undertaken. Analyses were conducted qualitatively and quantitatively. The quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods and regression models. Thematic analysis and interpretation were used to examine and understand qualitative data. The study found that industries’ role and dedication in accomplishing corporate social responsibility objectives in the investigated area was low, owing to poor follow-up, corruption, and the government’s reluctance to adequately enforce rules and regulations. The study suggests that the state authorities should monitor and evaluate the enforcement of business regulatory frameworks at grassroot levels rather than rely on reports. There is evidence showing the networked interest of businesses and corrupt state authorities hurdle the local community development should be benefited from business social responsibilities in exchange for their resources. The untold history of business effect should be revealed and remedies should be provided.

1. Introduction and the concept of corporate social responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) was touted as a self-regulatory and voluntary endeavor by firms to produce shared wealth with host communities beyond their legal responsibilities. However, the multiple conceptualization and application of CSR over the years which allows for flexibility in the application of the concept at different times and different social, political, and economic contexts has resulted in a lack of a common definition of CSR and reduced its contribution to development (Gond & Moon, Citation2011; Idemudia, Citation2011; Lin-Hi, Citation2010; Okoye, Citation2009,; Uwafiokun, Citation2008).

According to Prieto-carron et al. (Citation2019), the distinctions between a company’s mandated and voluntary actions are blurred, particularly in developing nations, and CSR initiatives are frequently observed as a blend of the two. CSR is a determined effort by businesses to act in ways that benefit their owners, employees, and suppliers, as well as consumers, the government, the host community, the ecosystem, and society as a whole (Michael & Nwoba, Citation2016). CSR has become a global priority (Saiia et al., Citation2003), with commercial organizations committing to community well-being and the environmental (Carroll, Citation1991; Du et al., Citation2013; Michael Blowfield & Jedrzej George Frynas, Citation2005).

CSR lacks a clear and uniform definition. According to the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (Watts et al., Citation1999), it is defined as a company’s ongoing commitment to act ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of its employees and their families, as well as the local community and society at large. CSR is also defined by the European Commission as “businesses that voluntarily integrate social and environmental issues into their business operations and relationships with their stakeholders” (European Union Green Paper, Citation2001). Furthermore, many countries have used CSR as a vehicle for socioeconomic development, understanding that employees are a valuable resource; ethical concerns are essential to the firm; and corporations have a responsibility to the community (Murphy & Schlegelmilch, Citation2013).

CSR, also known as social investments in major areas such as water, health, education, and so on, has been promoted as a self-regulatory mechanism through which companies, in addition to their legal financial commitments to the host country and communities, undertake various initiatives and projects. Academics, practitioners, and stakeholders disagree over what motivates companies to make this voluntary social investment (Carroll, Citation2016; Hilson, Citation2012; Prieto-carron et al., Citation2019). Higher levels of trust (Lin et al., Citation2011), improved image or reputation (Tewari, Citation2011), higher employee retention (Kim & Park, Citation2011), and the development of customer relationships are all benefits of CSR expenditures (Peloza & Shang, Citation2011). CSR refers to an organization’s responsibility to engage in actions that protect and contribute to the welfare of society, including consumers, shareholders, the environment, and employees (Davis & Frederick, Citation1984).

CSR, according to Smith (Citation2003), is treating the firm’s stakeholders ethically or responsibly. When a company engages in certain-caring corporate community service activities to achieve strategic commercial objectives, this is known as strategic CSR (Lantos, Citation2002). According to Smith (Citation2003), CSR refers to a company’s responsibilities to society, or more specifically, the company’s stakeholders who are impacted by its policies and activities. CSR is a concept in which businesses consider the interests of society by accepting responsibility for their actions influence on consumers, suppliers, employees, shareholders, communities, and other stakeholders, as well as the environment. This requirement demonstrates that businesses must abide by the law and take voluntary steps to promote the well-being of their employees and their families, as well as the local community and society at large (Maimuneh, Citation2009). CSR proponents argue that it is a way for businesses to generate shared wealth by creating jobs, supporting local businesses, financing infrastructure development, and providing training and education opportunities in host communities, as well as gaining social legitimacy (Carroll, Citation2016; Hilson, Citation2012; Prieto-carron et al., Citation2019). Critical CSR theorists, on the other hand, argue that CSR is simply a mechanism for businesses to get a social mandate/license to operate and lower business risks associated with host community rejection and resistance to their activities (Barsoum & Refaat, Citation2015; Gilberthorpe & Banks, Citation2012; Hilson, Citation2012). According to Barsoum and Refaat (Citation2015), companies are faced with the double burden of ensuring that their activities have no or minimal socio-economic and environmental impacts while also taking on governments’ responsibility of undertaking development due to poor socioeconomic conditions and high unemployment rates, particularly in developing countries, combined with neglected government responsibility in ensuring community development. As a result, when corporations’ CSR programs do not reflect community expectations and demands and are not tailored to the local environment, they are viewed as “poor development” (Barsoum & Refaat, Citation2015).

The growth of large corporations and their desires to maximize individual profits has not only split the world into wealthy and poor but has also resulted in an imbalance between development and environmental sustainability (Vyralakshmi & Sundaram, Citation2018)

According to a study conducted by Dodh et al. (Citation2013), the earth is gradually becoming a dangerous place to live as a result of unsustainable human-induced activities. As a result, many governments have taken hard positions to ensure that current development methods are in optimal harmony with environmental sustainability and human security. As a result, the notion that environmental and social security is not solely the responsibility of the government but also require active participation from the corporate and business world has gained traction (G.Vyralakshmi & Sundaram, Citation2018).

To generalize, though different conceptual understandings are evolving on CSR, we can summarize it as the way out where business organizations are actively engaging in sociocultural, economic, and environmental development activities in their host communities to minimize their spillover effects. Indeed, it has far-reaching community development implications. On top of that, this paper presents empirical evidence of CSR in developing countries’ context based on primary data collected from local communities in southern Ethiopia. The paper contributed to the literature on CSR from developing countries’ perspectives, to bring together government authorities, practitioners, and businesses for dialogues, and policy inputs.

2. Problem analysis

The International Monetralty Fund (IMF, Citation2006), reported that developing country economies are fast evolving. Their businesses’ operational activities have a profit-making growing market. It also has substantial social and environmental issues, including civil conflicts, natural disasters, and political unrest (IMF, Citation2006). In response to environmental and social factors such as globalization, economic growth, investment, and business activity, developing countries will be forced to adopt CSR practices, according to (UNDP, Citation2006) report instability developing countries will be forced to adopt CSR practices. Furthermore, Visser & Crane, Citation2012 shows that CSR in Africa is still in its infancy. Because the legal system is underdeveloped, CSR is a less demanding driver.

According to Carroll (Citation2016), the bulk of the world’s population resides in developing countries, each of which faces its own set of social, political, and environmental challenges. These countries are in the process of industrialization and are generally marked by insecure governments, high unemployment, inadequate technological capacity, unequal income distribution, unreliable water sources, and underutilized production factors. Besides, these challenges, business corporations have long been chastised for irresponsible actions such as pollution, unfair treatment of employees and suppliers, and selling inferior goods to customers. However, they are expected to be lucrative, socially and ecologically responsible, humane employers, and worldwide good citizens, according to Murphy and Schlegelmilch (Citation2013).

Irrespective of this, businesses in Ethiopia primarily aimed to maximize profit margins, at whatever cost to its employees, consumers, suppliers, environments, and/or residents of resource frontiers. (Ayele, Citation2008; Stebek, Citation2012). Due to this reason businesses, particularly, large and medium size manufacturing industries in Ethiopia are continuously bringing devastating human and environmental damages, and sociocultural crises (see, Regassa, Citation2022).

There are twofold contradictory scenarios in this context. On the one hand, the government provides various regulatory frameworks to businesses that force them to engage in social responsibilities where they are operating. On the other hand, the environmental and human impacts of businesses are continuously increasing in the country (see Robertson, Citation2009; Stebek, Citation2012; Eyasu et al., Citation2020, Endale et al., Citation2020; Regassa, Citation2022; Ying et al., Citation2021; Degie & Kebede, Citation2019). The existing studies on CSR in Ethiopia are emphasized conceptual understanding of CSR (Robertson, Citation2009; Kellow & Kellow, Citation2021), unprecedented business impacts (Regassa Citation2022), causal factors of CSR (Eyasu et al., Citation2020, Endale et al., Citation2020), and theoretical understandings of CSR (Degie & Kebede, Citation2019; Gulema & Roba, Citation2021). However, the effects of CSR activities of business organizations are studied. There are limited studies on the local residents’ perceptions as the data sources also prevalent which shows the methodological gaps. These empirical and methodological gaps are addressed in the current study. As a result, the central research question of the study is how and to what extent manufacturing industries are involved in community development to discharge their social and economic responsibilities of local resource frontiers.

To answer the research question, the study relied on the stakeholder theory perspective. Stakeholder theory proponents (R. E. E. Freeman & McVea, Citation2005; & R. E. Freeman & Dmytriyev, Citation2017; Brown & Forster, Citation2013; Freeman and Dmytriyev, Citation2017) argue that for long-term profitability and sustainability of businesses, it is crucially important to incorporate societal and community interests into their strategic goals and daily operations as the pillar of business activities. Business firms owe corporate accountability to a wide range of stakeholders, including employees, suppliers, consumers, the government, investors, the community, and the environment (Astrie & Bangun, Citation2013).

These days, it is impossible to avoid growing stakeholder pressures, accommodating their interests in the process and decision-making makes business more friendly with resource frontiers and local communities (Brown & Forster, Citation2013; Russo & Perrini, Citation2010). Stakeholder theory helps to draw attention to the contractual relationship and validate its practices, identify stake claims and risks, and analyze it from multiple perspective of busienss sustanaibality vis-s-vis minimize environmental tradoff effects of business operations (Brown & Forster, Citation2013; R. E. Freeman & Dmytriyev, Citation2017). Thus, this theory helps the study to meet its objectives and coined the relationships among business and local vicinities based on the fact that it demonstrates that industries as firms have duties to a larger group of stakeholders. Over time, it calls business firms to their social responsibility programs with dual objectives. First, it ensures its sustainability and profit margins, and second, it fosters development in its host communities of resource frontiers.

3. Materials and methods

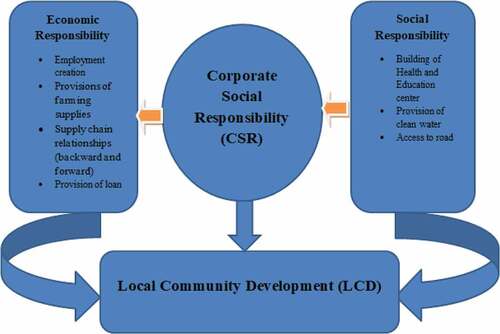

3.1. Conceptual framework of the study ()

3.2. Description of the study area

One of Ethiopia’s regional states is the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (commonly known as SNNPR). Kenya (including a small portion of Lake Turkana) borders the SNNPR on the south, the Ilemi Triangle (a region claimed by both Kenya and South Sudan) on the southwest, South Sudan on the west, the Gambela National Regional State on the northwest, and the Oromia National Regional State on the north and east. The region is expected to have a population of 14,929,548 people, with 7,425,918 men and 7,503,630 women (Central Statistical Authority (CSA), Citation2007). Rural residents make up 13,433,991 people (89.98%), whereas city dwellers make up 1,495,557 people (10.02 percent). The SNNPR is Ethiopia’s most rural area, according to these estimates. With an estimated area of 105,887.18 square kilometers, this region has a population density of 141 people per square kilometer. This region has 3,110,995 households, with an average of 4.8 people per home (3.9 persons per a household in urban areas and 4.9 persons per a household in rural areas).

Sidama, the second study area region, has become Ethiopia’s newest 10th regional state since June 2020, and is located around 275 kilometers south of Addis Ababa. Sidama became Ethiopia’s tenth regional state in November 2019, after previously serving as one of the administrative zones of Ethiopia’s Southern Nations Nationalities and People’s Regional State. Between 6° 10′ and 7° 05′ north latitude and 38° 21′ and 39° 11′ east longitude, the Sidama can be found. It is largely bordered on the south, north, and east by the Oromia area, and on the south by the Gedeo zone and Oromia, and on the west by the Bilate River. In 2014, the total population was 3,677,370, with a total area of 6538 km2 and a population density of 452/km2, with an average household size of 4.99 people (Central Statistical Authority (CSA), Citation2007); (Matewos, Citation2019).

3.3. Data and methodology

Four different types of data gathering instruments/tools were utilized to collect primary data. Among the tools employed were key informant interviews, questionnaires (PAPI), Focus Group Discussions (FGD), and observation. In addition, secondary data was gathered from a few of the companies that were observed.

Quantitative and qualitative data gathering methods were used in the study. Quantitative data was collected from 401 local municipalities that are located close to manufacturing industries. These respondents were selected at random and proportionally from the two areas, SNNPR and Sidama Regions.

Gedeo, Gurage, Wolayta, Gamo Zones and Bugarija city in the SNNPR region, and Hawassa City in the Sidama region, were purposefully chosen based on the recommendation of SNNPR and Sidama Region Investment office and the level of local community resides around these industries. Researchers oversaw the PAPI (Paper Assisted Personal Interview) technique, which was used to collect the questionnaire. Six Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with members of the local community and six key informant interviews with government officials were held respective to the selected 6 study area and categorized as FGD1 to FGD6 and KII1 to KII6 according to the order of selected areas listed above. Observation was also held during the data collection and it strengthened the finding of the study to see the real effect of industries to local community.

The collected data was analyzed using both qualitative and quantitative methods. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 and STATA 15 were used to process and analyze survey data and thematic approach were used to analyze the data collected from FGDs and KII

3.4. Sampling technique and sample size

In this study, probability (random) sampling methods were applied. Using the probability sampling method in this type of inquiry is more difficult and costly. On the other hand, probability samples are the only type of sample whose results may be extended to the entire population.

Researchers employed multistage sampling methodologies to discover local communities surrounding industries. In the first step, the Southern Nation Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR) and the Sidama Region were divided into zones. The authors chose four (4) zones from the total of 16 zones in the SNNPR, as well as Hawassa City Administration from Sidama Region, using simple random selection. As table shows the researchers selected 401 local communities from the defined zones and city in a proportional manner.

Table 1. The sample respondents allocated for each zone

The sample size determination formula is used to determine the study’s overall sample size (Cochran, Citation1977).

Where Z—Upper α/2 percentile point of a standard normal distribution with α = 0.05 being the level of significance

P—The probability of success

d—The desired margin of error

DEFF—design effect because of using multi-stage sampling

The sample is distributed when the overall sample size has been calculated. The following formula was used to calculate probability proportional to size.

Where:—nh—sample size in h zones,

n—Estimated final sample size,

Nh—Total number of households in h zone and,

N—Total number of households in selected 4 zones and two city Adminstrations

As a result, the sample of respondents to be assigned to each zone was determined as shown in the table below:

3.5. Method of data analysis

Descriptive (mainly tabular) and inferential statistics are used to analyze quantitative data gathered through questionnaires and secondary information. Descriptive data were used to determine the extent to which industries are meeting their social and economic responsibilities, as well as the effect of their operations on the local community. Inferential statistics such as multiple regressions, on the other hand, were utilized to facilitate effective analysis and interpretation of research data. This analysis framework develops a relationship between the study’s variables using modeling and the casual association of the variables (Independent Variables Vs Dependent Variables). To examine qualitative data, narrative and descriptive analyses using the theme technique were utilized.

Various parametric statistics were evaluated using the R regression output. At a 5% level of significance, the coefficient of correlation (R square) and F statistic were employed to assess the strength of the association between the independent and dependent variables. The significance of the independent variable was determined using the t-test. The amplitude, direction, and significance of the association were evaluated using the model coefficient (estimator).

The relationship was explained by the following regression model

Where: Y- Local community development, βo—constant, β1 and β2 are—Social and Economic responsibility coefficient, X1 and X2 Social and Economic variable and e—Error term for model (Gujarati & Porter, Citation2010)

3.6. Test for assumption

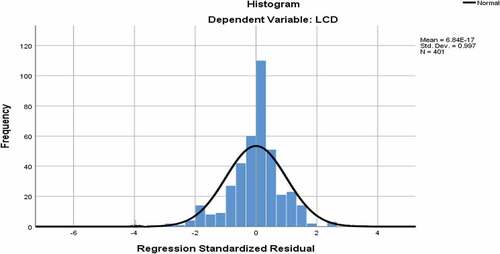

3.6.1. Normality test

Experts create a variety of normality tests. Each has its own set of advantages and disadvantages. One of the tests is the histogram. Examine how well the distribution line shape and bar heights match in the histogram. The data closely resembles the normal distribution if the bars closely follow the predicted distribution line, indicating that the model is well fitting as shown in Figure below. (Ayitey et al., Citation2021).

3.6.2. Testing for multicollinearity test

As we can see, in Table , the VIF value for both social and economic responsibility is 1.247. As a result, the VIF value of 1.247 is less than 10. The variance of an ordinary least ordinary least square (OLS) estimated regression coefficient measures its precision. We can conclude that the VIF value is less than 10, indicating that the independent variables are not multicollinear (Rawlings et al., Citation2001).

Table 2. Testing for multicollinearity assumption

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Introduction

A total of 8 manufacturing industries are examined in order to investigate the socioeconomic effect of Corporate Social Responsibility for Local Community DevelopmentFootnote1 in Southern Ethiopia.

From the SNNPR region, industries such as METAD Agriculture Development PLC from Gedeo Zone, Tinaw Flower Factory and Destaw Textile from Gurage Zone, Dilbe Ali Plastic PLC and Floor factory from Wolaita Zone, Arba Minche Textile factory from Gamo Zone, ETAB soap factory and BGI Ethiopia from Sidama Region have been chosen for this study.

Eight industries are selected from four zones and two cities based on SNNPR And Sidama Region Investment commission recommendation. These industries are suggested based on the longest stay in the establishment year, the largest industries in the area, the level of interaction with the local community and the availability of local community near to industries to see whether the industries effects are positive or negative or both.

When Industries established in one locality they obliged three major responsibilities besides the social and economic responsibilities. These obligations are creation of job opportunity for local communities; the second is income generation and payment of tax to the government; and the third is generation of foreign currency.

Apart from these obligations, since they are generating profit by utilizing local community resources, such as agricultural land; they are required to fulfill various responsibilities through various means in order to address some community problems, such as the building of schools, roads, clinics, the provision of clean water, and any other activities that will improve the local community’s living conditions.

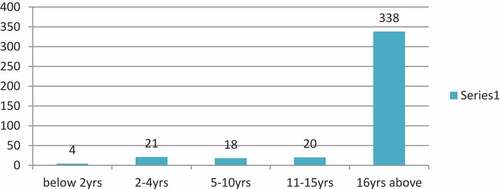

4.2. Length of stay in the community

In order to determine the socioeconomic effect of corporate social responsibility on local community development, we found it necessary to inquire about the length of stay of the respondents near to the industry. As seen in , a considerable number of the local communities have resided in the area for more than 16 years, with 338 (84.3%) of the total respondents. Because the majority of the respondents have lived in the neighborhood for a long time, they can readily assess the effect of industries on community well-being by comparing what has improved and what has had bad consequences in that area.

The remaining 21 (5.1%), 20 (5%), 18 (4.5%), and 4 (1%) respondents, respectively, had lived in the neighborhood for 2–4 years, 11–15 years, 5–10 years, and less than 2 years.

Overall, 397 of the total respondents have lived in the area for more than 5 years. From this figure, we can infer that the respondents have sufficient knowledge about the companies’/ manufacturing’s negative and positive effects on the local community, as well as the extent to which the industries are meeting the duties they promised when they started the business activity.

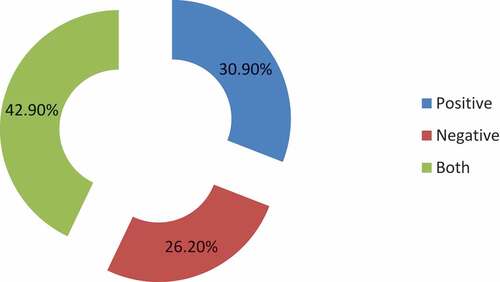

4.3. Effect of industries to the local community

As shown in the Figure below, 26.2% of the respondents stress industries negative effect on their community, 30.9% believe that industries have a positive effect on their community, and 42.9% believe that industries have both a negative and positive effect on their community.

According to the FGD with local community members, the soap and beverage industries in Hawassa, the flower factory in Welkitie, and the textile factory in Butajura towns dispose of their liquid wastes into the open environment with little treatment, exposing the surrounding community to various health problems such as asthma as a result of bad smile and skin diseases, and pregnant women who work in these industries and live near them face abortion as a result of the waste. Furthermore, their domestic animals (goats, sheep, and cows) were harmed because they drank the factory-released waste liquids. In line with this finding according to Daouda (Citation2014), multinational corporations have been accused of violating workers’ rights and environmental standards (release of toxic waste, air and water pollution and sometimes low wage compensation).

As shown in Figure , industries, notably ETAB soap factory in Sidama region, Hawassa city, release liquid waste during the night and when it rains, and the odor has negative effect on human’s health condition and animals. Furthermore, liquid wastes are dumped into Hawassa Lake, causing harm to aquatic species and reducing the productivity of fish in the Hawassa Lake.

Even if the company management verifies that there are no negative effects or noise for the community, what we learn from the community through FGD and our observation during data collection shows the soap company is not effectively treating trash discharged by the company. The researchers enquired of the government official whether corrective measures had been done for such industries. The interviews with the Hawassa city Investment and Project office explains that even if the company is creating jobs for the local community and paying high taxes to the government, there are certain problems associated with waste management system. Even if the city administration strives to monitor and check the industry’s function in regard to its negative effect on the neighborhood, the monitoring system is weak and ineffective. According to community elders, the industries have negative consequences on the community, but the government has done little to address the problem despite the fact that the community has frequently raised the matter.

According to an interview with investment office experts, the industries’ irresponsibility is exacerbated by inadequate follow-up, corruption, and poor application of the investment office’s laws and regulations. Even while a consultation conference with higher government officials and industry representatives is held four times a year, it does not achieve the desired results and solve repeatedly reported problems from the community.

Community members in the majority of the examined locations complained that Industries are exploited their local resources without contributing to the community’s well-being. The firm has taken without compensation the community’s arable and grassing grounds, which were utilized to subsidize their families by cultivating crops and grassing their domestic animals. In line with this finding, according to Michael and Nwoba (Citation2016), industries can contribute to community development and poverty reduction not only by providing sources of livelihood through social investment, but also by ensuring that existing resources are not harmed or lost as a result of company operations.

4.4. Social responsibilityFootnote2

Among the key activities of industries’ corporate social responsibility, the first and most important is to alleviate poverty to the local communities and to promote social amenities such as health center, building education, drinkable water, and roadsThe authors devised four primary indicators to determine whether the industries are fulfilling their social responsibility or not.

4.4.1. Social responsibility on education

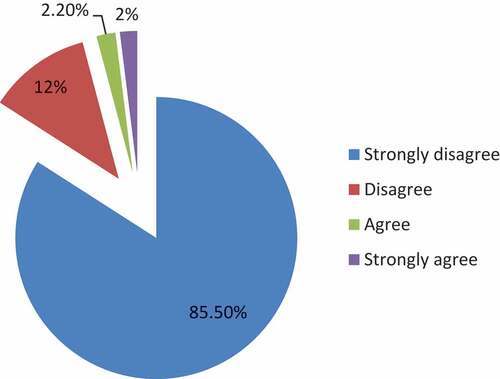

Respondents were asked their level of agreement about whether the industry in their local area was established school for the community, as indicated in . About 85.5% and 12% of the overall respondents disagreed and strongly disagreed, respectively, that the industry has no contribution for school building for the local community. According to an interview with corporate executives in METHD Agriculture Development PLC and BGI Ethiopia, they are not building schools but they are contribute some amount of money for school building, supporting impoverished and orphan children in the community by supplying exercise books, pens, and books, as well as fixing school chairs.

In addition, METHD Agriculture Development PLC from Gedeo Zone has provided iron sheets and cement for the reconstruction of the police station, as well as repairing classrooms in the community’s old school. This business firm wants to develop elementary schools for the community around their property, according to the manager, but they are being contested by local officials. The corporation needs to establish a school under their own supervision, but the local governors are not willing because all aspects of the school construction be handed over to them, which the company is unwilling to do to control wastage of money by the local official.

4.4.2. Social responsibility on healthcare center

Table shows that, industries corporate social responsibility (CSR) in funding health care centers which is quite limited. Only 6 (1.5%) of the total respondents agreed with the support of industries in the construction of healthcare centers for the community to promote healthcare delivery.

Table 3. The industry has built healthcare centers for the community to promote healthcare delivery

The results demonstrate that a significant number of respondents disapproved or strongly disagreed with the industries’ support. As a result, the majority of community members are dissatisfied with the services offered by industries in the local area. According to Robertson (Citation2009), private investment in Ethiopia aspires but is not engaged in corporate social responsibility, and private–public partnerships are scarce. According to FGD with community members, the manufacturing industries in their local area are not supporting the community through the provision of health facilities such as clinics and other health treatment facilities, nor have they provided subsidies to remedy the current health center supply shortages.

4.4.3. Social responsibility on water provision

When asked if the local industry supplies drinkable water to the community, As table shows that,only30.1% strongly agreed or agreed that it does. According to FGD with community members, “the water supplied by the corporation is insufficient to meet community need, lacked regularity, is not sustainable, is distributed in phases (once a week), and is not accessible to the community who resides near to the industry.”

Table 4. The industry provides potable water to the community

For example, the Tinaw Flower Factory in Gurage zone, which has been in operation for 14 years and is the largest flower producer in Southern Ethiopia, operates on 47 hectares of land. The community in this area raised a lot of complaints to the company. According to a focus group discussion with a local community youth organization and elders, it has been noted that the corporation has not lived up to its social responsibility promises made when it first opened its doors.

In addition, they point out that the firm promised to give clean drinking water, a road, a school, and a clinic, but only provided clean drinking water. Unfortunately, the water supply is insufficient and inaccessible to the local populace living near the industry. The community pointed out their agricultural land is being stolen by the enterprise without recompense and fake promises and the concerned government body is not monitoring regularly, way of monitoring is mechanism is exposed to corruption and are not controlling the company is fulfilling their responsibilities or not.

“As the community has stated, the company took our arable land without adequate compensation in exchange for more profitable land, but we still drink water from the river and ponds because the water provision expected from the company is not accessible to us, and our children are absent from school in search of water.”

4.4.4. Social responsibility on road

Only 4.2% and 0.5% of the total community residents who were questioned their level of agreement with the manufacturing industry providing the community with good roads strongly agreed and agreed. Table demonstrates that a significant proportion of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed about the role of business firms in investing in road infrastructure. Even, the constructed road by the company have low quality and only functional during the dry season; during the rainy season, they completely crumbled, posing a difficulty for people and animals in the community’s mobility.

Table 5. The manufacturing industry has provided the community with good roads

During FGD with community elders and religious leaders in Gedeb Woreda and Hawassa city, the company did not invite them to participate in the development of the community support strategic plan or the decision-making process regarding the community support system, and that they were not asked what their priorities were, but instead engaged in community service on a haphazard basis. For example, we were asked the company to build road but the company is not engaged in this aspect. In line with this, According to Masum et al. (Citation2020) companies operating in developing countries, lack transparency on the issue of local implementing agencies, since they do not make sufficient steps to reveal information about their programs, audits, and the use of funds intended for CSR activities

We can conclude from the aforementioned findings that the industries are failing to meet their social responsibilities and are primarily concerned with maximizing profit at the expense of community benefit, and that the government’s follow-up mechanism is week, exposed to corruption and, the system is weak and this exacerbate the problem and create grievance with the community and on the government.

In general, the participants of the study area reported that industries are useful contribution to improve social amenities and solve social problems in one hand if they fully respond to their responsibility but not fulfilled their responsibility with the desired amount and the companies in the study area does not have corporate social responsibility division except the company of Tinaw Flower factory in Wolqite Zone.

Participants in the study area are grateful for the contribution made by the business firm to help the member of the community through helping the farmers to increase the productivity of the coffee production, to gain improve the school service of the children, employment creation, supporting youth in the sport club, building bridge, access to potable water, contribution to orphaned children, elderly and poor people, supporting displaced people by the conflict.

However, some issues make it difficult to conclusively state the community members to fully satisfied with service business firms has made available. The first issue that the community members regret is the mismatch between what the industries promised when they establish the business and what the company actual performance. Which means the mismatch between community expectation and the performance of the business firm in the provision of social amenities. Another source of dissatisfaction is the size of land taken by the company as a payback for infrastructure building in the community. But, not compensate the community instead of the arable land taken. This is true in business firms in Hawassa city, Butajira city, Welqite Zone and Wolayita zone. According to Muthuri et al. (Citation2012), given the high altitudes of poverty, illiteracy, disease, poor governance, and lack of infrastructure in developing countries, companies are projected to play a vital role in addressing these problems. The archetype of CSR contribution to community infrastructure development demonstrates corporate donations to build school, hospital buildings, renovation bridges, building of roads, and other community projects (Newell & Frynas, Citation2007).

4.5. Economic responsibilityFootnote3

The researchers examine the economic responsibility of industries by asking four major questions through four major variables in order to see the economic influence of industries CSR activity for local community development. These are the industries’ ability to create jobs for the local community, the extent to which industries support the local community (farmers) by providing farming supplies such as seeds, pesticides, and fertilizer, supply chain relationships (backward and forward) linkages between industries and local communities, and finally, loan provision.

4.5.1. Economic responsibility on employment creation

Local communities were asked whether or not the industries in their community had created job opportunities for the local community. As shown in Table , 272 (67.8%) of the total respondents agreed that industries formed in local communities create job opportunities for unemployed youths and e part of societies in the community, depending on their educational background and experience. The remaining 126 (31.5%) of the respondents stated that the industries in their community did not create job opportunities for the unemployed youths. According to an interview with the local community, in Hawassa city industries, such as ETAB Soap Factory, do not recruit employment from the local community; rather, the company recruit employees from other areas, this creates dissatisfaction among the local community.

Table 6. Manufacturing industries/companies and employment creation capacity

According to Trading Economics’ global macro models and analysts’ predictions, in Ethiopia, there is an increasing number of graduate students but job losses deskilling many of the country’s active youth. Manufacturing industries/enterprises play an essential role in CSR for individuals who have graduated but are unemployed.

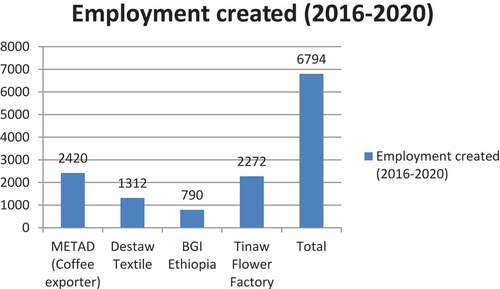

As indicated in Figure ,the information obtained from textile factories in Butajira, BGI Ethiopia in Sidama, METAD in Gedeo Zone, and Tinaw flower factories in Wolqite, a total of 6966 job opportunities have been created d for the local community residences. From the total employees, 4301 are permanent, and the remaining 2372 and 293 being casual and temporary employees respectively

Almost 90% of the personnel are hired from the local community, according to the interview conducted with the industry managers. But the employees complained that the work load and working hours is not proportional to the payment and compensation system of the company and they said that the company exploits them.

The main economic obligations of industries, according to (Baah & Tawiah, Citation2011), are to hire local workers, which ensures the supply of employment opportunities and good working conditions. In our case, it appears that industries are producing job opportunities for the local population, but the wage, working conditions, and working environment are not conducive to the company employees.

“We work long hours, often more than 8 hours each day, but the remuneration is insufficient, therefore most workers leave their job. There is no such thing as equal pay for equal work.”

Even while these businesses provide significant employment opportunities for the local people, they lack job security and a suitable working environment. Low payment and long working hours without relaxation impair employees’ physical and psychological well-being, according to focus group discussion with industry employees and their families. This indicates that majority of employees are abandoning their jobs because of low payment and employment benefits. Furthermore, corporations do not provide training, and future employment opportunities, as well as employee safety, are not taken into account. Contradict with the finding of Alemayehu, Citation2017, who stated that the corporation is very careful when it comes to CSR initiatives involving employee safety, security, benefits, development, and overall well-being.

4.5.2. Economic responsibility on provision of farming supplies

Local residents were asked whether the industries give farming products such as seeds, insecticides, fertilizer, and other materials that will assist farmers living near the industry in increasing their productivity.

According to the local community elders

“When the companies developed in the area, they were promised to support farmers through the provision of fertilizer, better seed, and training services for farmers around their sites, but they did not provide what they promised.”

Unfortunately, as shown in Table , about 327 (81.2%) respondents believe that the industries working in their local area do not provide support to the s the community who live near the business organization up on their promises. Farmers in Gedeo zone Gedeb Woreda, however, are in a unique situation where the coffee exporting company, METAD, aided the growers in a variety of ways. According to the farmers, before this industry began to work in their area, their coffee plantations were infected, the soil had lost its fertility due to soil erosion, and the lack of shade trees for coffee quality was one of their main challenges, and as a result, their coffee yield in quantity and quality had decreased, and their income had been severely impacted. In which the coffee industry registers coffee producer farmers and assists them by supplying better coffee seedling, training, fertilizer, and assigning coffee specialists to assist the farmers and produce quality coffee. They also assist them in digging up steep coffee grounds and planting VtiVar grass to improve soil fertility. The industry contacts the farmers two times within a year pre-harvest and post-harvest to provide training for farmers and to discuss social issues. In addition, in collaboration with FTC (Farmer Training Center) the company providing training for farmers to get best experience in how to increase productivity and how to use of pesticides in their farm land. Apart from that, industry, specifically Tinaw flower factory, participates in tree-planting campaigns, clean-up and green initiatives, and the germination and development of tree seedlings to promote reforestation and afforestation efforts across the country.

Table 7. Industries support the local community (farmers) with provisions of farming supplies (seeds, pesticides, fertilizer, etc.)

4.5.3. Economic responsibility on supply chain relationship

There is no substantial backward and forward linkage between the local community and the industries, as shown in Table , 370 (92.3%) of the total respondents strongly disagreed or disagreed. During discussion with community members, even though they produce materials that will serve as input for industries t, the industries do not used our products as input for they industries s instead purchase raw materials from other companies and/or industries. Furthermore, communities are not purchasing industrial products since, the industries are not considering the demand and purchasing power of the community.

Table 8. The industries support the local community through supply chain relationships (backward and forward)

According to the zonal administration, there is a significant gap in agricultural technology transfer compared to farmers’ and the zonal administration’s expectations, and the level of forward and backward linkage is very poor, with almost no linkage in terms of using inputs from nearby farmers. Those who agreed or strongly agreed, particularly those from the Gedeo zone, believed that the industry in their community has some backward and forward linkage with the local community (farmers). Farmers sell their coffee to METAD Agriculture Development P.L.C., and the company provides various supplies like training on new technology, best seeds and training on diversification farming system to the coffee farmers in order to help them boost their productivity. According to Ahmad et al. (Citation2020), closer ties aid in transfer of technology between MNCs that provides concern on CSR and communities in the host countries

4.5.4. Economic responsibility on provision of loan

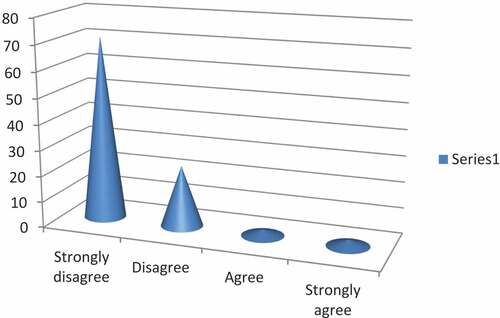

The youth and farmers in the local community needs loan from the manufacturing companies at a very low interst rate. As Figure indicates, a total of 381 (95%) of the respondents had not obtained a loan from the industries.

“We asked the industries to offer us with a loan and arrange ourselves to engage in different economic activities,” according to discussions with local youngsters in various communities, “but the reaction from the industries” was not positive. As a result, we are jobless and reliant on our families’ sources of finance to start business. This is consistent with the study GTZ businesses in Africa have found that the most common approach to CSR issues is through philanthropic support in particular focusing on education, health and environment (GTZ, 2009). But in some zone like in Gedeo zone, the company provides farmers interest-free loans during coffee harvesting season and provide dividends based on the international coffee market.

Most of the factors that assess a firm’s economic responsibility, for job creation, were found to be insignificant, implying that in terms of economics, the local community is not benefiting from firms and industries are not resolving problems. The focus groups we held in various industry sectors revealed that industries have a minor role in the community and rely solely on local resources. This industrial action causes resentment in the host community, which leads to conflict. In line with this, (Michael & Nwoba, Citation2016)claim that firms’ social corporate responsibility to their host communities has far-reaching community development advantages. Businesses and organizations that fail to practice Corporate Social Responsibility may face conflict, which can block the attainment of the company’s stated objectives.

Businesses’ commitment to social corporate responsibility in their host communities has far-reaching community development implications. Businesses and organizations that fail to practice corporate social responsibility may face conflict, which can block the attainment of the company’s stated objectives (Michael & Nwoba, Citation2016).

4.6. The effects of CSR for local community development

It is thought that a company’s or manufacturing industry’s corporate social responsibility is linked to the growth of the community in which they operate. The results of the multiple regression analysis of the effects of corporate social responsibility on local community development are presented in . A multivariable study, shown in Table , assesses the simultaneous effects of corporate social responsibility on community development at the local level.

Table 9. The aggregate effect results of Model summary of CSR for community development

Table 10. OLS regression results: The effects of CSR on local community development

In regressions where the model has been chosen as a dependent variable, the R squared values and adjusted R squared values in the previous table are less than even 0.5. In these circumstances, the slope coefficients were employed.

However, for the multiple regression analysis, the R squared but not adjusted r squared values are significantly bigger than 0.05 and the slope coefficient is significant. As performance indicators, social and economic responsibilities have been highlighted. As a result, if we omit regression and rely on R squared values and adjusted R squared values, we can conclude that social and economic responsibility, or CSR, has a significant effect on local community development.

The term “percentage variation in LCD that is explained by independent (CSR) factors” is defined by R-squared. Social and economic responsibilities account for 49.1% of the variation in y (LCD) in this case. This statistic has a flaw: as the number of predictors (LCD local community development) grows, so does the number of predictors.

Linear regression is a simple yet powerful method for examining the connection between independent and dependent variables. Many people, on the other hand, disregard OLS assumptions before evaluating the data. As a result, analyzing the numerous data presented by Ordinary least squares is crucial (OLS).

Table shows that the p-values for social and economic responsibility are both less than 0. As a result, social and economic responsibility have a significant and negative effect on the development of the local community. However, because the p-value is greater than 0.05, we may be confident that the regression coefficient will fall within this range 95% of the time. If the interval does not contain 0 the p-value was 0.05 or less.

If the level of social responsibility (SA) rises by one unit, the LCD falls by 0.221 units, assuming all other parameters remain constant. Because the Sig. value is 0.000, which is less than the acceptability region of 0.05, the considerable change in LCD is attributable to economic responsibility. Holding all other factors constant, a one percent increase in economic responsibility increased the LCD by 0.125 percent. The research found a positive relationship between economic responsibility and local community development with a coefficient of 0.125. As a result, the analysis suggests that the economic responsibility (ECO) of CSR has a significant positive relationship with local community development (LCD).

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Companies have a vital role in developing countries to enhance community well-being through corporate social responsibilities by engaging them in different societal and economic activities.

Among the key responsibilities of industries’ Corporate Social Responsibility, the first and most important is to alleviate poverty of the local communities through employment creation and to promote social amenities like health, education, drinkable water, and roads. However, some provision has been made by the business firms but not up on what the industries promised and what the communities expected.

Another major responsibility among the primary ones are economic responsibility of industries in terms of job creation, credit provision, helping farmers through the provision of farming supplies, and forward and backward linkage. Other variables, aside from the creation of employment opportunity for the local community, are determined to be negligible and the created employment opportunity is not upon the standard of labor regulation of Ethiopia which violate equal pay for equal work.

In order for the business to be more profitable and acceptable for the society, the business firms have to fulfill what the community expects from them and what they promised. In addition, business firms have to be more conscious on their activity because strike will happen on the business firms if they are not obliged to their responsibility.

Weak government oversight, corruption, and government reluctance are the main reasons for industries failing to meet their obligations, putting the local population at risk, particularly when it comes to waste management.

The government has to protect the local community through regulating the business firm activities and forcing them to fulfill the responsibility on behalf of what has been taken from the community.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the local community, industry managers and the government officials who participated in this study for their honest and cooperative response to all the questions solicited in this research. We would also like to thank Dilla University, Research and Dissemination Directorate for the financial support we received to carry out the research project on which this article is based. Any errors that still remain in this article are, however, our intellectual responsibility.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The effort of an individual or organization in a community conducted to help and solve community problems.

2. The commitment of industries to fulfill their social responsibilities through the provision of social amenities like building of health and educational center, provision of drinking water and access to road to reconnect the rural to urban area.

3. The involvement of industries to bring economic improvement in the community through the indicated variables in the conceptual framework of the study.

4. Social responsibility: school, healthcare, water supply and roads.

5. Economic responsibility: employment creation, provision of loan, supply chain relationship, provision of farming supplies.

References

- Ahmed, M., Zehou, S., Raza, S. A., Qureshi, M. A., & Yousufi, S. Q. (2020). Impact of CSR and environmental triggers on employee green behavior: The mediating effect of employee well‐being. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(5), 2225–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1960

- Alemayehu, W. (2017). Assessment of corporate social responsibility practices of MOHA soft drinks industry: The case of summit plant.

- Amponsah-Tawiah, K., & Dartey-Baah, K. (2011). The mining industry in Ghana: A blessing or a curse. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(12). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kwasi-Dartey-Baah/publication/280557496_The_Mining_Industry_in_Ghana_A_Blessing_or_a_Curse/links/55b9045c08aed621de084c6c/The-Mining-Industry-in-Ghana-A-Blessing-or-a-Curse.pdf

- Astrie, K., & Bangun, Y. R. (2013). Development path of corporate social responsibility theories. International Conference on Innovation Challenges in Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, 3(December), 45–59.

- Ayele, S. K. (2008). Industrial waste and urban com- munities in Addis Ababa: The case of akaki kaliti and kolfe keranio sub cities (MA Thesis). AAU, July, 1–76. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Industrial-Waste-and-Urban-Communities-in-Addis-the-Kifle/fc6799ef8890e678ef4486888438aa4393122bb1

- Ayitey, E., Kangah, J., & Twenefour, F. B. K. (2021). Sarima modeling of monthly temperature in the northern part of Ghana. Asian Journal of Probability and Statistics, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJPAS/2021/V12I330287

- Barsoum, G., & Refaat, S. (2015). “We don’t want school bags”: Discourses on corporate social responsibility in Egypt and the challenges of a new practice in a complex setting. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 35(5–6), 390–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-07-2014-0054 :

- Brown, J. A., & Forster, W. R. (2013). CSR and stakeholder theory: A tale of Adam Smith. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(2), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1251-4

- Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. 39–48.

- Carroll, A. B. (2016). Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 1(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6

- Central Statistical Authority (CSA). (2007). Summary and statistical report of the 2007 population and housing census results. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Cochran_1977_sampling techniques.pdf. 1–428.

- Daouda, Y. H. (2014). CSR and sustainable development: Multinationals are they socially responsible in Sub-Saharan Africa? The case of Areva in Niger. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos, 28, 141–162. https://doi.org/10.4000/cea.1719

- Davis, K., & Frederick, W. C. (1984). Business and society : Management, public policy, ethics (5th) ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Degie, B., & Kebede, W. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and its prospect for community development in Ethiopia. International Social Work, 62(1), 376–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872817731148

- Dodh, P., Singh, S. A., & Ravita. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and sustainable development in India. Global Journal of Management and Business Studies, 3(6), 681–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-07664-9_8

- Du, S., Swaen, V., Lindgreen, A., & Sen, S. (2013). The roles of leadership styles in corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(1), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1333-3

- European Union Green Paper. (2001). Promoting a European framework for CSR. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities. European Commission.

- Eyasu, A. M., Arefayne, D., & Ntim, C. G. (2020). The effect of corporate social responsibility on banks’ competitive advantage: Evidence from Ethiopian lion international bank SC. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1830473. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1830473

- Eyasu, A. M., Endale, M., & Ntim, C. G. (2020). Corporate social responsibility in agro-processing and garment industry: Evidence from Ethiopia. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1720945. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1720945

- Freeman, R. E., & Dmytriyev, S. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder theory: Learning from each other. Symphonya. Emerging Issues in Management, 1, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.4468/2017.1.02freeman.dmytriyev

- Freeman, R. E., & Dmytriyev, S. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder theory: Learning from each other. Symphonya. Emerging Issues in Management, 1, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.4468/2017.1.02freeman.dmytriyev

- Freeman, R. E. E., & McVea, J. (2005). A stakeholder approach to strategic management. SSRN Electronic Journal. March 2018. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.263511

- Gilberthorpe, E., & Banks, G. (2012). Development on whose terms?: CSR discourse and social realities in Papua New Guinea’s extractive industries sector. Resources Policy, 37(2), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-07-2014-0054

- Gond, J., & Moon, J. (2011). Corporate social responsibility in retrospect and prospect: Exploring the life-cycle of an essentially contested concept. ICCSR Research Paper Series, 44(59), 1–40. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/business/who-we-are/centres-and-institutes/ICCSR/DOCUMENTS/59-2011.PDF

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2010). Essentials of econometrics (4th) ed.). Mc Graw Hill.

- Gulema, T. F., & Roba, Y. T. (2021). Internal and external determinants of corporate social responsibility practices in multinational enterprise subsidiaries in developing countries: Evidence from Ethiopia. Future Business Journal, 7(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-021-00052-1

- Hilson, G. (2012). Corporate social responsibility in the extractive industries: Experiences from developing countries. Resources Policy, 37(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.01.002

- Idemudia, U. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and developing countries: Moving the critical CSR research agenda in Africa forward. Progress in Development Studies, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100101

- International Monetary Fund. (IMF). (2006) IMF Annual report, World Economic Outlook Financial Systems and Economic Cycles. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2016/12/31/Financial-Systems-and-Economic-Cycles

- Kellow, A., & Kellow, N. (2021). A Review of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in Ethiopia. In S. M. Apitsa & E. Milliot (Eds.), Doing Business in Africa: From Economic Growth to Societal Development (pp. 191–211). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50739-8_9

- Kim, S. Y., & Park, H. (2011). Corporate social responsibility as an organizational attractiveness for prospective public relations practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(4), 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0886-x

- Lantos, G. P. (2002). The ethicality of altruistic corporate social responsibility. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(3), 205–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760210426049

- Lin, C. P., Chen, S. C., Chiu, C. K., & Lee, W. Y. (2011). Understanding purchase intention during product-harm crises: Moderating effects of perceived corporate ability and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0824-y

- Lin-Hi, N. (2010). the problem with a narrow-minded interpretation of Csr: Why Csr has nothing to do with philanthropy. Ramon Llull Journal of Applied Ethics, 1, 79–95.

- Maimuneh, I. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and its role in community development;An international perspective. The Journal of International Social Research, 2, 200–209. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.C1084.1083S19

- Masum, A., Hanan, H., Awang, H., Aziz, A., & Ahmad, M. H. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and its effect on community development: An overview. Journal of Accounting Science, 22(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-2201053540

- Matewos, T. (2019). Climate change-induced impacts on smallholder farmers in selected districts of Sidama, Southern Ethiopia. Climate, 7(5), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7050070

- Michael Blowfield & Jedrzej George Frynas. (2005). Editorial Setting new agendas: critical perspectives on corporate social responsibility in the Source: International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs, 81(3), 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00465.x

- Michael, U. J., & Nwoba, M. O. E. (2016). Community development and corporate social responsibility in Ebonyi State : An investigative study of selected mining firms and communities. Journal of Policy and Development Studies, 10(2), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.12816/0028346

- Murphy, P. E., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and corporate social irresponsibility: Introduction to a special topic section. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1807–1813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.001

- Muthuri, J. N., Moon, J., & Idemudia, U. (2012). Corporate innovation and sustainable community development in developing countries. Business & Society, 51(3), 355–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650312446441

- Newell, P., & Frynas, J. G. (2007). Beyond CSR? Business, poverty and social justice: An introduction. Third World Quarterly, 28(4), 669–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590701336507

- Okoye, A. (2009). Theorising corporate social responsibility as an essentially contested concept: Is a definition necessary? Journal of Business Ethics, 89(4), 613–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-0021-9

- Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0213-6

- Prieto-carron, M., Lund-thomsen, P., Chan, A., Muro, A. N. A., & Bhushan, C. (2019). Critical perspectives on CSR and development : What we know, what we don ’ t know, and what we need to know. International Affairs, 82(5), 977–987. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2006.00581.x

- Rawlings, J. O., Pantula, S. G., & Dickey, D. A. (2001). Applied regression analysis : A research tool. 657.

- Regassa, A. (2022). Frontiers of extraction and contestation: Dispossession, exclusion and local resistance against MIDROC Laga-Dambi gold mine, southern Ethiopia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 11, 100980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2021.100980

- Robertson, D. C. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and different stages of economic development: Singapore, Turkey, and Ethiopia. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(SUPPL.4), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0311-x

- Russo, A., & Perrini, F. (2010). Investigating stakeholder theory and social capital: CSR in large firms and SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0079-z

- Saiia, D. H., Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2003). Philanthropy as Strategy. Business & Society, 42(2), 169–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650303042002002

- Smith, N. C. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: Not whether, but how? Center for Marketing Working Paper, 44(3), 1–35. facultyresearch.london.edu

- Stebek,& E.N. (2012). The Investment Promotion and Environment Protection Balance in Ethiopia’s Floriculture: The Legal Regime and Global Value Chain The Investment Promotion and Environment Protection Balance in Ethiopia’s Floriculture. http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/56244

- Tewari, R. (2011). Communicating corporate social responsibility in annual reports: A comparative study of Indian companies & multi-national corporations. Journal of Management & Public Policy, 2(2), 22–51. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2034054

- UNDP. (2006). Multi-stakeholder engagement processes: A UNDP capacity development resource. UNDP Capacity Development, November, 1–29. http://content-ext.undp.org/aplaws_publications/1463193/Engagement-Processes-cp7.pdf

- Uwafiokun, I. (2008). Conceptualising the CSR and development debate. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 29(29), 91–110. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/jcorpciti.29.91

- Visser, W., & Crane, A. (2012). Corporate sustainability and the individual: Understanding what drives sustainability professionals as change agents. SSRN Electronic Journal, February. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1559087

- Vyralakshmi, G., & Sundaram, A. (2018). Corporate social responsibility and sustainable development: A legal perspective. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, 119(17), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95873-6_135

- Watts, P., Holme, L., International, S., & Tinti, R. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Meeting changing expectations. World Business Council for Sustainability Development. https://books.google.com.et/books?id=YWpaAAAAYAAJ

- Ying, M., Tikuye, G. A., & Shan, H. (2021). Impacts of firm performance on corporate social responsibility practices: The mediation role of corporate governance in Ethiopia corporate business. Sustainability, 13(17), 9717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179717