?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The paper seeks to examine the joint effect of entrepreneurship and FDI inflows on economic wealth in Africa. It employs a dynamic system GMM for a panel dataset of 52 African economies between 2006 and 2020. The study finds that FDI inflows induced a negative impact on the ease of doing business but it increases the business capital start-ups of entrepreneurs. We find that entrepreneurship reduces economic wealth in the short term but in the long-term entrepreneurship positively affect economic wealth. The results show that FDI inflows increase economic wealth and that FDI is an important channel through which entrepreneurship can impact economic wealth. We find evidence to support that ease of doing business and FDI inflows are substitutes while minimum capital of starting business complements FDI inflows in determining economic wealth. Based on the marginal effects, we conclude that entrepreneurship reduces economic wealth but improves economic wealth when the level of FDI inflows increases in a country. The implication is that countries should provide strategies that promote economic wealth of individuals, people and entrepreneurs through prudent business development framework and FDI supports in the short term.

1. Introduction

Recent debate on the concept of entrepreneurship, trade and economic growth (Ács et al., Citation2014; Huang & Chen, Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2022; Majumder et al., Citation2022; Miah & Majumder, Citation2020; Zhao, Citation2022) focusses on the impact of trade facilitation and institutions on sustainable environment and economic growth (Ibrahim & Ajide, Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c; Jiahao et al., Citation2022; Sakyi et al., Citation2017); the extent to which trade facilitation contributes to improving social welfare in Africa (Sakyi et al., Citation2018); and the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth in emerging markets (Ivanović-Đukić et al., Citation2022). A number of studies are devoted to the entrepreneurship-technological change nexus (Acs & Varga, Citation2005); impact of corruption on entrepreneurship (Dreher & Gassebner, Citation2013; Dutta & Sobel, Citation2016), as well as the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on entrepreneurship (Albulescu & Tămăşilă, Citation2014; Zhao, Citation2022). In addition, the role of foreign direct investments and entrepreneurial activity, as one of the main engines of economic growth is a topic of much discussion in existing literature (Kim et al., Citation2022; Neumann, Citation2020; Miah & Majumder, Citation2020; Gui-Diby, Citation2014, Gui-Diby & Renard, Citation2015; Coccia, Citation2011). The debate on the interrelationship between entrepreneurship, FDI and economic growth among economists in the past decade has reached a consensus that entrepreneurship and FDI independently matter for economic development and growth (Ács et al., Citation2014; Belitski & Desai, Citation2016; Huang & Chen, Citation2021; Nguyen, Citation2022). Entrepreneurship in particular is one of the drivers of macroeconomic development, but the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic wealth is complex. The literature emphasizes that the overall positive impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth (Atems & Shand, Citation2018; Audretsch & Keilbach, Citation2004a; Fritsch, Citation2008; Fritsch & Mueller, Citation2004) depends on a variety of associated determinants that influence the magnitude of the impact.”

It is evident that entrepreneurs require resources to make their efforts productive (Alvarez & Busenitz, Citation2001; Kim et al., Citation2022; Van Stel et al., Citation2005; Zhao, Citation2022), and one of the key resource for enhancing entrepreneurs’ abilities is foreign direct investments (Huang & Chen, Citation2021; Nguyen, Citation2022). Only recently have researchers begun to assess the impact of FDI on business creation or entrepreneurship (Albulescu & Draghici, Citation2016; Ibrahim & Ajide, Citation2022c; Urbano et al., Citation2019a; Zhao, Citation2022). Moreover, extant literature has focused on entrepreneurship-economic wealth nexus while ignoring the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on this relationship. However, to our knowledge, none of the studies examining the interrelationship between entrepreneurship, FDI and economic wealth distinguish between channels of entrepreneurial activity to promote economic wealth. This particular emphasis is theoretically attractive because entrepreneurs need resources to remain productive and that the expected impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth can be amplified by foreign direct investment inflows (Albulescu & Draghici, Citation2016; Alvarez & Busenitz, Citation2001; Ayyagari & Kosová, Citation2010; Jiahao et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2022). Therefore, this paper seeks to contribute to the literature by updating and expanding the empirical literature with the emerging stream of research on emerging economies, and incorporating studies that analyze not only the impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth but also the joint impact of entrepreneurship and FDI on economic wealth.

Advocates of entrepreneurship have supported the view that entrepreneurship is a channel for improving economic wealth (Acheampong & Hinson, Citation2019; Sobel, Citation2008) while others show that entrepreneurs can increase economic wealth through external financing models such as the FDI inflows (Fahed, Citation2013). FDI inflows provide capital to fund entrepreneurial activity, leading to an increase in economic wealth. For most developing countries, FDI inflows are one of the most important source of external financing (Albulescu & Tămăşilă, Citation2014) that contributes to economic wealth, as receiving entrepreneurs and private businesses heavily rely on those inflows to enhance their businesses (Neumann, Citation2020).

Extant literature posits that entrepreneurs through their entrepreneurship, function to coordinate, control and combine factors of production in order to create wealth in economies (Kriese et al., Citation2021). FDI is imperative for stimulating entrepreneurs to develop their businesses and generate income for start-ups and entrepreneurial activities (Agbloyor et al., Citation2016). The extensive literature has shown that incentives to business entry is associated with the setup capital for a new business (Adusei, Citation2016; Kim & Li, Citation2012; Kriese et al., Citation2021). In fact, the usual way of evaluating entrepreneurial activities refers to the ability of entrepreneurs to generate resources to start a business. This implies that entrepreneurs require good business conditions to start a business or even to continue existing business. However, these studies do not take into account the ease of starting a business, the ease of doing business, and the minimum capital needed to start a business—as well as how these indicators interact with foreign direct investment to affect economic wealth. The effect of FDI inflows on the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic wealth has been discussed in two ways, as documented in the empirical literature (Doytch, Citation2012). On the one hand, entrepreneurs are expected to benefit from the support and know-how they receive through transfers from large companies or direct inflows of foreign capital (Doran et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, entrepreneurs are expected to suffer negative externalities due to the increase in the competitive environment (Kritikos, Citation2014). Despite the mixed debate existing between entrepreneurship, FDI and economic wealth in the literature (Kim et al., Citation2022; Majumder et al., Citation2022; Zhao, Citation2022; (Ács et al., Citation2014; Huang & Chen, Citation2021; Ibrahim & Ajide, Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c; Ivanović-Đukić et al., Citation2022; Jiahao et al., Citation2022; Miah & Majumder, Citation2020; Sakyi et al., Citation2017), as discussed above, most of these studies were focused on developing countries.

It is important to note that the Agenda 2063 has become Africa’s blueprint and a master plan for transforming Africa into developing a strategic framework that aims to deliver on its goal for inclusive and sustainable development. Thus, increased globalization and increased integration among economies in Africa has made the region a global powerhouse to be reckoned with and hence, improving sustainable economic growth through their support to emerging development and investment opportunities. Given the importance of globalization and the fact that Africa is endowed with abundant resources that serve as primary inputs for entrepreneurial activities and investment opportunities for most sectors of an economy (Agbloyor et al., Citation2014; Awad & Ragab, Citation2018), studies that examine how foreign direct investment and entrepreneurship interact to affect economic wealth in Africa are lacking. This is because most African economies who seek to develop their entrepreneurship and private sector businesses, lack the needed support or capital, and capital flows that can enhance their business-wealth nexus (Agbloyor et al., Citation2014). While there are both intuitive and theoretical reasons that FDI inflows play a key role in modulating the impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth, it is unclear in the empirical literature whether FDI inflows better modulate the impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth. The current study fills this gap by examining the impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth that depends on FDI flows.

Further, differences in economic activities and the nature of interrelationship between entrepreneurship, foreign direct investment and economic wealth across countries in Africa, allow us to adopt the dynamic system GMM model to capture assumptions about specific moments of the random variables employed instead of assumptions about the entire distribution.

Improving economic growth in the developing and emerging economies remains a top priority on the global development agenda, as policymakers, development partners, practitioners and researchers worldwide aim to achieve the sustainable development goals. This study makes some important and novel contributions to the literature in developing and emerging economies. First, it investigates whether foreign direct investment (FDI) is an important driver of the alternative measures of entrepreneurship (based on the World Bank indicators of Doing Business). Second, the study contributes to the literature by examining the independent effect of the alternative measures of entrepreneurship and FDI on economic wealth. Finally, it empirically examines the interactive impact of FDI and entrepreneurship on economic wealth do not happen immediately (in the short term), but they take effect in the long term.

“The rest of the paper is organized into an overview, literature review, methodology, empirical results and discussions and conclusion and policy implication and recommendation sections.”

2. Entrepreneurship, FDI Inflows and economic wealth in Africa: an overview

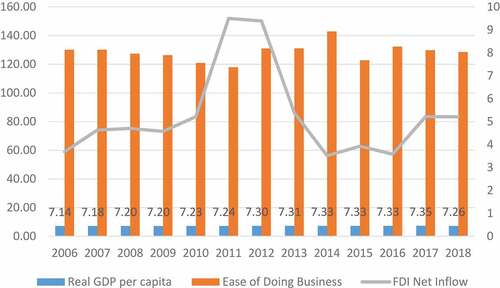

This section provides an overview of entrepreneurship (measured as the ease of doing business), FDI flows (measured as FDI inflows relative to GDP), and economic wealth (measured as real GDP per capita) in Africa. The World Bank has published the annual Ease of Doing Business report since 2004, and the report ranks nearly 200 countries on the ease of doing business on various criteria. These criteria include 10 indicators of ease of doing business. Data on the ease of doing business come from the World Bank’s Doing Business Report, while data on real GDP per capita come from the World Bank’s Development Indicators Database.

Ease of doing business represent entrepreneurship that translates into promoting economic wealth. Moreover, FDI inflow is a conduit through which entrepreneurship affects economic wealth. In Table , the average ease of doing business in Africa is 128.54. Over the period 2006–2017, the ease of doing business in Africa has shown a stable trends, although there were some marginal changes over the period. From Table , it decreased generally from 130.07 in 2006 to 128.54 in 2018. This implies that the ease of doing business in Africa needs to be strengthened. FDI inflows increase from 3.69 in 2006 to 5.27 in 2018. Moreover, FDI inflows in Africa shows a general changing trends over the 2006–2018 period.

Table 1. Trends in Entrepreneurship, FDI Inflows and Economic Wealth

Considering economic wealth, measured as real GDP per capita, the average is 7.26 with the lowest (7.14) and highest (7.35) occurring in 2006 and 2017, respectively. Thus, real GDP per capita shows an increasing trends over the 2006–2017 period in Africa.

In Figure , it is evident that real GDP per capita has been increasing at a steady state over the period while ease of doing business and FDI inflows have shown some changing trends over the same period (see, Figure ). This shows that the relationship between entrepreneurship, FDI inflows and economic wealth is not clear from the African perspective.

3. Literature review: theories, empirics

In recent times, increased globalization have driven and stirred up greater interest among researchers in understanding how the world business activity and private capital flows can induce greater wealth for an economy (Layla et al., Citation2020). Wealth, which explains the value of all the assets of worth owned by a person, community, company or country, is an important concept which cannot be overemphasized. Thus, it can be argued that market economies that allow for trade and entrepreneurship create higher national gross domestic product required to create economic wealth (see, Jiahao et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2022; Miah & Majumder, Citation2020).

The study draws insight from the theory of resource-based entrepreneurship, which states that “entrepreneurs need resources to start and carry their businesses. Money and time alone are not sufficient for a successful startup, hence entrepreneurs require resources to make their efforts productive and creating wealth for themselves (Alvarez & Busenitz, Citation2001)”. The theory is therefore important in the process of enhancing an economic agent’s ability to maximize wealth through financial, social and human resources. Entrepreneurship has now been linked with all economic activities that create residual profits in excess of the rate of return for land, labor and capital (Glancey & McQuaid, Citation2000). The residual profits generated from entrepreneurial activities have the potential to yield high returns, drive economic growth and in turn leads to greater national and individual wealth. In this regard, many scholars have taken the interest to understand the important role that entrepreneurship play in economic growth and economic wealth (Doran et al., Citation2018; Hessels & Van Stel, Citation2011; Olaison & Meier Sørensen, Citation2014). In the literature, entrepreneurship can affect wealth in many ways. These include increased competition and increased diversity in terms of product and services offering (D. Audretsch & Keilbach, Citation2004; Fritsch, Citation2008). It also leads to the creation of jobs, the introduction of new innovations and productivity enhancement.

“The entrepreneurship literature has focused on identifying determinants of entrepreneurship, including the economic context, government policies, entrepreneurial culture, and the operating environment. Recently, researchers have started to study the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on the set up of new enterprise (Ayyagari & Kosová, Citation2010). This can be argued from the resource curse hypothesis, which explains that many resource-rich countries fail to benefit from their natural resource wealth, and governments in these countries fail to respond effectively to public welfare needs. In view of this, it is expected that the impact of FDI on entrepreneurship can be a curse or a blessing to an economy. On the one hand, demand creation indicates that the impact of domestic companies are expected to benefit from the know-how that multinational companies transfer. On the other hand, entrepreneurs of domestic companies are expected to suffer negative externalities due to increased competition and technology created by barriers to entry. Thus, the resource curse hypothesis induces a positive or a negative impact of FDI on entrepreneurship (Zhao, Citation2022). Therefore, foreign direct investment is a key channel through which entrepreneurship affects economic wealth. Our work on entrepreneurship and the FDI relationship advances a new frontier of research on the determinants of the entrepreneurship literature. On the one hand, as explained by Kim and Li (Citation2012), the relationship between FDI and entrepreneurship was first examined in the context of the secondary effects of FDI in host countries. Previous studies have reported both positive and negative effects of FDI on entrepreneurship. Most previous studies are based on state regulations in developed and developing countries (Kim & Li, Citation2012; Sabirianova Peter et al., Citation2005). Adverse side effects or no effects have been reported in emerging economies (Djankov & Hoekman, Citation2000; Konings, Citation2001; Sabirianova Peter et al., Citation2005), with less empirical studies in the African region. Similar results were reported by De Backer and Sleuwaegen (Citation2003) for firm entry and exit among Belgian manufacturing industries. In contrast, Görg and Strobl (Citation2002) find a positive effect of FDI on the entry of new domestic firms into Ireland. A more recent work by Zhao (Citation2022) used a panel dataset containing 31 provinces of China over 1992–2017, and they found a positive FDI-entrepreneurship nexus. Zhao (Citation2022) provide evidence that the knowledge diffusion and technology transfer effect more than offset the crowding-out effect of FDI on local entrepreneurship.

Recent studies examine the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on entrepreneurship using a panel data approach. For instance, Ibrahim and Ajide (2022) investigates whether trade facilitation acts as a stimulus or deterrent for FDI inflows by employing the fixed effects model and differece-generalized method of moments (D-GMM) for a panel data of 26 African countries over the period, 2004–2914. They show that trade facilitation significantly hinders FDI inflows. While Doytch and Epperson (Citation2012) found that foreign direct investment positively affects entrepreneurship only in the middle-income group, Kim and Li (Citation2012) found that the most important positive effect of foreign direct investment on entrepreneurship is in regions with weak institutional support is more obvious. Their findings, from the analysis of a committee of 104 countries, are consistent with expectations that foreign direct investment is positively associated with starting a business, particularly in less developed countries characterized by a lack of institutional support, political stability and good human capital. However, the contradictory findings in the literature can also be related to the missing distinction between opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurs. In terms of FDI inflow, startups are increasing as entrepreneurs see new opportunities in the market. On the contrary, since multinational corporations create jobs, foreign direct investment has a negative impact on the necessity-driven entrepreneurs. These hypotheses allow us to reconcile conflicting findings in the literature. Albulescu and Tămăşilă (Citation2014) studied 16 European countries over the period 2005–2011 and showed that FDI inflows have a positive impact on opportunity-driven entrepreneurs, while FDI outputs have a positive impact on necessity-driven entrepreneurs and a negative effect on the other category of entrepreneurs. In addition, we also examine the impact of entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment on economic wealth. When local investors live in the country to find new opportunities abroad (foreign direct investment), opportunity-based business activity decreases while demand increases as more people looking for alternative incomes to improve their wealth find no work. Interestingly, the above discussion from the literature has not specifically examined the impact of FDI on different measures of entrepreneurship, given the nature and different forms of entrepreneurship in developing and emerging markets.

Given that research on the macroeconomic impacts of entrepreneurship and FDI has gained increasing recognition over the past two decades and across a wide range of disciplines (Ibrahim and Ajide, 2022; Urbano et al., Citation2019a; Zhao, Citation2022), empirical work on this relationship in the African context needs to be regularly reviewed to inform and reflect current advances and stimulate future research. Several high-quality review papers have already summarized the large body of research on the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth, ignoring empirical studies on how entrepreneurship affects economic wealth in Africa. For example, Wennekers and Thurik (Citation1999) were the first to discuss the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth in the analysis of the narrative literature. Van Praag and Versloot (Citation2007) made the first systematic attempt to distinguish the few economically significant start-ups from the most insignificant youth. In a non-systematic study, Fritsch (Citation2013) conducted a comprehensive survey and evaluated the knowledge available at the time on how start-ups in particular have affected regional development over time.

Improving economic growth in the developing and emerging economies remains a top priority on the global development agenda. For that reason, previous studies have shown which factors can determine the impact of start-ups or entrepreneurial activities on economic growth. For instance, Ivanović-Đukić et al. (Citation2022) showed that entrepreneurial activity has a positive impact on economic growth by using a panel data analysis of 20 emerging countries in the period, 2011–2018. Block et al. (Citation2017) analyzed the consequences of innovative entrepreneurship based on a systematic literature review of 102 studies published between 2000 and 2015. Urbano et al. (Citation2019a), a systematic literature review of 104 studies published between 1992 and 2016, focusing on the relationship between institutional structure, entrepreneurship and economic growth (see, Ibrahim & Ajide, Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c; Jiahao et al., Citation2022; Sakyi et al., Citation2018). For instance, Jiahao et al. (Citation2022) examine the direct and interactive impacts of trade facilitation and institutions on sustainable economic growth, by employing the two-step dynamic system GMM estimator for 41 sub-Saharan African economies over the period, 2005–2019. They find that the interactive impacts of trade facilitation and institutions positively predict the sustainable economic growth. Accordingly, all existing studies have been structured with an overview of empirical knowledge on the impact of entrepreneurship on the economy. However, they did not provide empirical evidence on the impacts of entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment on economic wealth. Recently, Doran et al. (Citation2018) examined the role of entrepreneurship in stimulating economic growth in 55 countries, including developing and developed countries, between 2004 and 2011. They found that entrepreneurial activities suppress or dampen gross domestic product per capita in low- and middle-income economies. This result clearly shows that entrepreneurship is a key factor in boosting national productivity. Research over the past 25 years shows that entrepreneurship is one of the drivers of economic development, but the impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth is very complex. Although a number of research works have identified different types of entrepreneurships as well as trade facilitation and their impacts on sustainable economic growth in the African region (Ibrahim & Ajide, Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c; Jiahao et al., Citation2022; Sakyi et al., Citation2018), these studies have ignored the independent impacts of FDI and different measures of entrepreneurship (such as ease of doing business, ease of starting business, and minimum capital for starting business) on economic growth in Africa. The current literature emphasizes that the impact of entrepreneurship depends on a variety of related determinants that influence the magnitude of that impact, particularly foreign direct investment. For instance, Fritsch (Citation2008) explained that entrepreneurship has several mechanisms through which it can affect economic wealth.

Much emphasis has been given to the existing relationship between entrepreneurship and growth. However, though, extant literature also assumes a strong connection between FDI and economic growth (Mamede & Davidsson, Citation2004), the potential impact of FDI on the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic wealth has not been explored. A recent study by Majumder et al. (Citation2022) employed the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) for a dataset from 1997 to 2018, to test the effects of foreign direct investment (FDI) on export processing zones in Bangladesh. They found that FDI and GDP growth both have a positive relationship in accelerating export processing zones. Miah and Majumder (Citation2020) applied the ARDL bound testing and the error correction model for a time series dataset covering the period 1972–2017 to explain the impact of FDI and export on the economic growth of Bangladesh. They found that an increase in FDI and exports lead to an increase in economic growth. However, in the long run, FDI negatively and insignificantly related to economic growth. Surprisingly, these studies have not empirically examined the effect of FDI in the entrepreneurship-wealth nexus, especially in Africa. Based on the literature, it is argued that globalization or integration of market economies is critical to developing national wealth because it creates higher national GDP, increase world business activities and promote economic creativity to obtain wealth through trade and entrepreneurship—yet the role of FDI in shaping the effect of entrepreneurship on economic wealth has not been empirically examined. Given that FDI drives entrepreneurship to affect economic wealth, it will be interesting to examine empirically the impact of FDI on the entrepreneurship-wealth nexus.”

Based on the reviewed literature above, the paper formulates the following hypotheses:

H1: FDI inflows has a negative impact on entrepreneurship

H2: The independent impact of entrepreneurship and FDI inflows on economic wealth is positive in the long term.

H3: FDI inflows moderates the impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth

4. Methodology

We construct a panel dataset of 52 African economies. The sample covers 13 years from 2006 to 2020, a period spanning different economic and business conditions. Data were selected based on the availability of data. This is because data on the variables of interest (FDI, Global Ease of Doing Business indicators and real GDP per capita) that were obtained from the respective databases (i.e. collection of datasets from Global Financial Development, World Bank Ease of Doing Business databases and IMF)—captured 52 African countries over the period, 2006–2020, hence, controlling for missing data bias. We utilize the baseline model, which is expressed as:

5. Model specification

5.1. Relationship between entrepreneurship, FDI Inflows and economic wealth

Following previous studies (Alfaro et al., Citation2004; Doran et al., Citation2018; Ferreira et al., Citation2017; Ibrahim & Ajide, Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c; Jiahao et al., Citation2022; Neumann, Citation2020; Sakyi et al., Citation2017) there is an interrelationship between entrepreneurship, FDI inflows and economic wealth. We build on their model by adopting the dynamic System Generalized Method of Moments (SGMM) that allows for the simultaneous determination of entrepreneurship, FDI inflows and economic wealth.

First, we argue that FDI inflows impact entrepreneurship-economic wealth nexus. This implies that FDI inflows have a direct impact on entrepreneurship and in turn influence economic wealth. Given this complex relationships, the study presents a dynamic SGMM model, as applied by Jiahao et al. (Citation2022), Ibrahim and Ajide (Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c), Wooldridge (Citation2001); Lu & Wooldridge, (Citation2020), and Sakyi et al. (Citation2017). This was employed to give an efficient estimates. First, the study explains the effect of FDI on the entrepreneurship indicators, as specified below:

“where subscript j denotes cross-sectional dimension (country specifics), j = 1, … , M; denotes the time series dimension (time),

= 1, … , T;

is the coefficient of the lag of dependent variable (entrepreneurship indicators);

represents the coefficient of FDI inflows;

k = 5, … , N, represent the regression coefficient parameters for vector V to be estimated. V is a vector of control variables that explains the model;

is idiosyncratic error term, which controls for unit-specific residual in the model for the jth country at period t.”

Second, we argue that both entrepreneurship and FDI inflows have an independent effect on economic wealth. We apply the SGMM model, as used by Agbloyor et al. (Citation2016, Citation2019) to deal with possible endogeneity that may exist. This is expressed as:

where is the coefficient of the lag of dependent variable (economic wealth);

represent the coefficients of entrepreneurship variables and its lags;

represents the coefficient of FDI inflows;

k = 5, …, N, represent the regression coefficient parameters for vector C to be estimated. C is a vector of control variables that explains the model.

is idiosyncratic error term, which controls for unit-specific residual in the model for the jth country at period t.

6. Independent effect

The dependent variable in the model is economic wealth. Economic wealth refers to the net wealth of an economy (Pettinger, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Neumann, Citation2020). It measures the value of all assets of worth (valuable economic resources) owned by a nation or economy. An increase in real output and real income suggests an economy is better off and therefore there is an increase in economic wealth. As explained earlier, numerous studies have investigated the determinants of economic growth from countries in Africa (Cramer et al., Citation2020; Heshmati, Citation2018; Hillbom & Green, Citation2019; Langdon et al., Citation2018; Mills et al., Citation2017; Nnadozie & Jerome, Citation2019; Noman et al., Citation2019). Following Batrancea et al. (Citation2022) and Pettinger (Citation2017a), we measure economic wealth using real GDP per capita, where higher values denote greater economic wealth. Data on real GDP per capita were obtained from the IMF database.

In Equationequation 3(3)

(3) , economic wealth is a function of past year’s economic wealth, entrepreneurship, FDI inflows and other macro-economic indicators.

Entrepreneurship, according to the Dau and Cuervo-Cazurra (Citation2014) is the “creation of new businesses by a stable collection of individuals, households, entrepreneurs, and micro, small and medium-sized enterprises who coordinate their efforts to generate new value-added economic activity.” We decompose entrepreneurship into three indicators including; (1) Ease of doing business, (2) Ease of starting business, and (3) Minimum capital for starting business. The use of these indicators were drawn from the ease of doing business database of the World Bank and the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) (Herrington, Kew & Kew, Citation2010), as were used in the studies of Kriese et al. (Citation2021). Data on ease of doing business was obtained from the World Bank database of ease of doing business index. This is defined as the ease of doing business score, which is measured with 10 indicators of the simple average of the scores for each of the doing business indicators: “starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting minority investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts and resolving insolvency. The score is computed based on the methodology in the DB17-20 studies for topics that underwent methodology updates.”

Data on ease of starting business was obtained from the World Bank database of ease of doing business index. This is defined as the “score for starting a business”, measured as “the simple average of the scores for each of the component indicators: the procedures, time and cost for an entrepreneur to start and formally operate a business, as well as the paid-in minimum capital requirement.” Data on “minimum capital for starting a business” was obtained from the “World Bank database of ease of doing business index, which ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 represents the worst regulatory performance and 100 the best regulatory performance.”

“EquationEquation 3(3)

(3) allows an analysis of the impact of entrepreneurship on economic wealth. As mentioned earlier, there are three alternative measures of entrepreneurship: ease of doing business, ease of starting a business, and minimum capital to start a business. These entrepreneurship indicators are expected to have a positive or negative impact on economic wealth. In particular, the effects of individual measures may not occur immediately. Previous research suggests that entrepreneurial activities can affect growth differently (Ibrahim & Ajide, Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c; Jiahao et al., Citation2022; Marcotte, Citation2013; Sakyi et al., Citation2018, Citation2017) due to differences in business formation and trade facilitation that exist among entrepreneurs. While previous studies show that entrepreneurship drives economic growth (Kim et al., Citation2022; Ivanović-Đukić et al., Citation2022; Asongu and Tchamyou Citation2016; Adusei, Citation2016), the current study contends that the positive impact is not straight forward. In view of that we expect entrepreneurship to have a negative effect on economic wealth in the short term. This is because initial levels of a country’s entrepreneurial capacity may not be sufficient to induce a positive effect on economic wealth. However, in the long run, we expect a positive entrepreneurship-wealth nexus. Also, we argue that entrepreneurship may not have a short-term positive impact on economic wealth. This is because a country may take time to develop its wealth or their economic resources may not be built up immediately to increase economic wealth through entrepreneurship. In this regard, we introduce the lag of each of the entrepreneurship indicators, and expect past year’s entrepreneurship indicators to positively affect economic wealth.

This suggests that countries that build their capacity to promote entrepreneurial activities are able to increase economic wealth in the long term. This is consistent with empirical studies that entrepreneurship boosts national productivity and economic growth (see, Adusei, Citation2016; Asongu & Nwachukwu, Citation2018; Doran et al., Citation2018) and that general ease of doing business is beneficial (Canare, Citation2018) and thus generate more economic wealth in the long term.”

EquationEquation 3(3)

(3) also shows the impact of FDI inflows on economic wealth.

FDI inflows are generally understood as an investment by a party in one country in a company or corporation in another country with the intention of establishing a lasting interest (Durham, Citation2004). FDI inflows in our sample are measured as the ratio of net inflows of foreign direct investment to a country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Data on FDI flows were taken from the Global Financial Development Database. We expect a positive or negative effect of FDI flows on economic wealth. A positive effect suggests that FDI inflows to a particular country are strong enough to promote economic wealth. This confirms the work by Gui-Diby (Citation2014). A negative effect suggests that countries with greater FDI inflows may channel investment funds into areas that may not directly increase economic wealth. This implies that FDI affects economic wealth spillovers negatively (see, Adams & Opoku, Citation2015; Konings, Citation2001).

Furthermore, as emphasized by earlier studies, FDI inflow has a divergent impact on economic growth. Indeed, most reviewed studies show that FDI had no impact on growth or may have been harmful to growth. Given that entrepreneurship may have a long-term positive impact on economic growth, we expect FDI inflows to supplement or complement entrepreneurship to influence economic wealth. Thus, countries with better entrepreneurial capability are expected to attract FDI inflows in order to promote economic wealth.

In what follows, we argue that past year’s entrepreneurship has a conditional impact on economic wealth conditioned on FDI inflows. Based on this, we introduce an interaction term between past year’s values of entrepreneurship indicators and FDI inflows to capture the joint effect and heterogeneity in the model. We expand Equationequation 2(2)

(2) and specify the model as follows:

where is the coefficient of the lag of dependent variable (economic wealth);

: represent the regression coefficients of a vector of three entrepreneurship variables, namely; ease of doing business, ease of starting business and minimum capital for starting business;

represents the coefficient of FDI inflows;

p = 1, … ,3 represents the coefficients of the interaction terms;

:

, are regression parameters for vector X (control variables) to be estimated;

is the country fixed effect; and

is the time fixed effect; and

is idiosyncratic error term, which controls for unit-specific residual in the model in the jth country at period t.

6.1. Interaction effects

In this model (Equationequation 4(4)

(4) ), we are interested in whether entrepreneurship indicators complement or substitute FDI inflows to influence economic wealth. We do this by looking at the signs and significance level associated with (1) the coefficients of the variables of interest and (2) the interaction terms. Following Compton and Giedeman (Citation2011), we interpret our results considering the signs associated with the coefficients of the interaction terms and the variable of interest. Given our expected (positive) signs associated with the coefficients of last year’s entrepreneurship indicators, a positive coefficient of the interaction terms between last year’s entrepreneurship indicators and FDI inflows suggests that the long-term effects of the variables of entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment inflows complement each other to achieve a desirable outcome of economic wealth. A negative coefficient of interaction terms between entrepreneurship indicators over the past year and FDI inflows suggests that the long-term effects of entrepreneurship variables and FDI inflows are substitutes to explain economic wealth. Following Brambor et al. (Citation2006), we interpret our results by calculating the marginal effects of the entrepreneurship variables. This interpretation makes economic sense because it tells us how last year entrepreneurship affects economic wealth due to differences in the levels of FDI inflows.

7. Controls

“We control for trade openness (percentage of export plus import to gross domestic product), industry employment (industry employment as a percentage of total employment), money supply (percentage of broad money to gross domestic product), gross capital formation growth (year-on-year percentage change in gross capital formation to gross domestic product), inflation rate (consumer price index), population growth (percentage change in year-on-year population on natural log of total population) and human development index (ranges between 1 and 0, computed as a function of education, health and income of an economy). Data on control variables were obtained from the World Development Indicator database the below variables and show the expected impact of the variables on economic wealth. We expect a positive relationship between trade openness and economic wealth, which implies that trade openness should increase wealth. We expect a positive effect of industry employment on economic wealth. This suggests that countries with greater share of industry employment should increase economic wealth. We expect positive effect of money supply on economic wealth. This indicates that countries with greater money supply should promote economic growth. We expect a positive relationship between gross capital formation and economic wealth, which implies that countries that are more focus on increasing gross capital formation should increase economic wealth. We expect a negative effect of inflation on economic wealth. This shows that macroeconomic uncertainty reduces wealth. We expect a negative effect of population growth on economic wealth. This shows that an increase in population puts pressure on the resources of a country, leading to a reduction in economic wealth. We expect a positive effect of human development on economic wealth. This shows that countries with a higher level of human capital development should achieve greater economic wealth.”

7.1. Estimation technique

The study employs a number of techniques to test for the validity, reliability and efficiency of the model. Based on the test results, there was no outliers, normality of each variable was achieved, multicollinearity was absent (Allison, Citation2012), and the severity of and presence of cross-sectional dependence was ignored for the models (Pesaran, Citation2015). “A potential problem that may arise from the model specified above is that problem of endogeneity. This is because the dynamic term and the bi-causal relationship that may exist between some of the explanatory variables and the dependent variable, under these circumstances, render the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) and Generalized Least Squares (Fixed-and-Random Effects) estimations not useful. In the presence of endogeneity, these estimation techniques are either biased upwards downwards. In view of that, the study employs the System Generalized Method of Moments (SGMM) Two-Step estimator with small sample size adjustments, forward orthogonal deviations and robust standard errors. This technique has been used by Jiahao et al. (Citation2022), Ibrahim and Ajide (Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c), Sakyi et al. (Citation2018), (Citation2017) and others. This improves efficiency and reduces finite sample bias (see, Arellano & Bover, Citation1995; Blundell & Bond, Citation1998). The GMM resolves issues of unobserved heterogeneity that may arise between countries and endogeneity that may exist from bi-causality and mismeasurements. The use of system GMM helps to generate its own instruments from the data and it has the advantage of not searching for external instruments whose exogeneity can be difficult to justify. Thus, the instruments that we use are therefore generated from within the data as is customary with GMM. The Hansen J test of over-identifying restrictions is used and the instruments are valid in our model. The Hansen test is distributed as chi-square under the null that the instruments are valid. We also check whether the model is correctly specified by looking at the presence of the nth-order serial correlation. To check for the reliability of the results, we use the Arellano and Bond (Citation1991) test of serial correlation in the errors, AR (1) and AR (2) to examine the serial correlation properties. Evidence of serial correlation in our model, as explained by Arrellano and Bond (Citation1991), Arellano and Bover (Citation1995) and Blundell and Bond (Citation1998), shows that the system GMM estimates are valid. We apply Windmeijer (Citation2005) correction to produce robust standard errors because the two-step estimator has been shown to be biased without this correction. The error term of the model was tested for its assumptions of normality, autocorrelation and homoscedasticity. We compare the number of instruments to the number of groups and confirm that the instrument did not exceed the number of groups (Roodman, Citation2009).”

8. Empirical results and discussions

Table shows the descriptive statistics of the explanatory variables. From Table , economic wealth recorded an average of 7.097 real GDP per capita. The average ease of doing business in our sample is 50.79, ranging from 19.11 to 81.59. The average score of starting business is 65.73, ranging from 2.21 to 95.13. This shows that out of a 100 score, the average score of the ease of doing business and starting business is more than half. Business capital start-up has an average score of 4.07, ranging from −2.3 to 8.54. FDI inflows recorded an average of 4.036% of GDP, given a range between −8.59 and 161.824.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics

In terms of the controls, trade openness recorded an average of 0.69, ranging between 0.19 and 3.76. The proportion of industry employment to total employment is 13.37%. Gross capital formation recorded an average of 21.58, inflation rate recorded an average of 7.74, population has an average of 15.69, money supply has an average of 34.54% of GDP and human development index recorded an average of 0.49.

Table shows evidence of no multicollinearity, as confirmed by a variance inflation factor (VIF) less than 10 (see, Wichers, Citation1975; York, Citation2012).

Table 3. Pairwise correlations

Table 4. Dynamic System GMM Estimation: Impact of FDI Inflows on Entrepreneurship

8.1. Relationship between FDI and entrepreneurship

In Table , it can be deduced that the impact of FDI inflows on entrepreneurship depends on the type of entrepreneurship indicator used. The three measures of entrepreneurship including the ease of doing business, ease of starting business and business capital start-up are the dependent variables in Table . It shows how FDI influence the ease of doing business, ease of starting business and business capital start-up. For example, in Model 1, FDI flows negatively impact ease of doing business. This suggests that FDI inflows limit the ease of doing business. This implies that entrepreneurs do not rely heavily on FDI inflows to fuel their activities within an economy. From the theoretical view of the resource curse hypothesis, a resource-rich countries fail to benefit from their natural resource wealth and their trading environment. Although foreign direct investment inflows can promote business activities and economic development, it is widely held among economists that FDI inflows can drive entrepreneurs’ interest from productive and economic activities to a wealth or rent-seeking activities and hence entrepreneurship can be severely hampered (Bjorvatn et al., Citation2012; Zhao, Citation2022). Therefore, resource curse hypothesis induces a negative effect of FDI inflows on entrepreneurship, and that entrepreneurs with a strong business capability attract smaller FDI inflows. This agrees with the debate in the work of Zhao (Citation2022) that FDI is a curse to entrepreneurship and it supports the negative impact of FDI on entrepreneurship from the works of Djankov and Hoekman (Citation2000), Konings (Citation2001), and Sabirianova Peter et al. (Citation2005). In model 3, however, foreign direct investment has a positive effect on the minimum capital required to start a business. This means that FDI inflows into an economy provide an immediate source of investment capital to entrepreneurs to start a business—hence, a blessing to entrepreneurship. The implication is that countries with higher FDI inflows can help entrepreneurs raise the minimum capital to start a business. Although our findings make significant contribution to the literature based on alternative use of entrepreneurship measures, it confirms the work of Christiansen and Ogutcu (Citation2002) that the FDI supports trade flows. It is also consistent with the work of Albulescu and Tămăşilă (Citation2014) that FDI positively influences opportunity-driven entrepreneurs. In general, our findings agree with the work of Zhao (Citation2022), who tested whether the impact of FDI on local entrepreneurship is a blessing or curse. He found that the impact is positive and that the effect of knowledge diffusion and technology transfer is more and offset the crowding out effect of FDI on local entrepreneurship in China’s economic transition.

On the control variables, inflation has a positive impact on economic wealth. Population reduces economic wealth. This is because countries with greater population may increase the rate of unemployment and may lead to lower economic wealth. The Human Development Index aims to promote economic wealth and confirms the findings of previous studies (Mankiw et al., Citation1992) that human capital is relevant for the conversion of inputs into productivity outputs.

The control variables have a varying impact on entrepreneurship due to the measure of entrepreneurship used.

8.2. Relationship between entrepreneurship, FDI Inflows and economic wealth

In Table , the ease of doing business has a significant negative impact on economic wealth (Model 4). This means that countries that open up their economy for trade are not able to benefit from trade opportunities due to the resource curse and provide an indication that the ease of doing business reduces economic wealth. This is not surprising, given the theory that unproductive entrepreneurship (see, Baumol, Citation1996) could reduce wealth and productivity in the sense that trade globalization drives entrepreneurs’ interest from investing in entrepreneurial activities to investing in unproductive sectors of the economy (see, Bjorvatn et al., Citation2012). Further, our results are consistent with the work of Kim et al. (Citation2022), who do not find evidence of a positive link between aggregate entrepreneurship and economic growth in a sample of advanced and developing economies. However, this pattern is not consistent with the experiences of developing countries in the work of Koster and Rai (Citation2008) and Sautet (Citation2013)—who provide evidence that an increasing rate of entrepreneurship leads to a decline in economic growth. Thus, entrepreneurship or the activity of starting and running a business is a vital ingredient of economic growth and development—which is not consistent with our findings rather, our empirical evidence points to the heterogeneous nature of entrepreneurial activity that impedes on economic wealth.

Table 5. Effect of Entrepreneurship and FDI on Economic Wealth

Based on our discussion, we introduce the lags of entrepreneurship indicators (ease of doing business, ease of starting business and business capital start-up) to observe whether the impacts of entrepreneurship on economic wealth is persistent over time. Interestingly, the lag of ease of doing business has a positive and significant impact on economic wealth. This suggests that countries that open their economy for business activities have a strong framework for ease of doing business to generate more economic wealth in the long run. Similarly, the ease of starting a business has a significant negative impact on economic wealth in the short term. In the long run, countries are able to increase their economic wealth by providing a favorable environment for business start-ups (Model 5). This is not surprising if we follow the theory of unproductive entrepreneurship (see, Baumol, Citation1996), which shows that entrepreneurship does not necessarily lead to successful wealth creation in short-term productivity, but will affect long-term wealth creation. Thus, in the long run, wealth-seeking entrepreneurs benefit from effective resources from business start-ups. Interestingly, minimum start-up capital has a positive impact on economic wealth in both the short term and long term (see Model 6). This shows that countries that open their economy for trade have the incentives to provide minimum start-up capital for entrepreneurs to persistently increase their wealth. In general, countries with strong entrepreneurship models are able to improve economic wealth in the long run. Thus, entrepreneurs that have easy access and enabling business environment are able to increase economic wealth over time. This is consistent with work by Canare (Citation2018), who found that the general ease of doing business has a positive impact on business formation, which ultimately promotes long-term economic growth and development (Doran et al., Citation2018). This adds that improvement in the ease of doing business contributes to economic wealth, as supported by Adepoju (Citation2017). The implication is that entrepreneurship promotes a good business environment, allowing companies and private entrepreneurs to prosper more and better contribute to economic wealth.

The results show a negative and significant impact of FDI inflows on economic wealth in the presence of ease of doing business (models 4) but has no significant impact on economic wealth (models 5–7) in the presence of other entrepreneurship indicators like ease of staring business and business capital start-up. This indicates that the impact of FDI on economic wealth is not direct but can provide an important channel through which entrepreneurship can impact economic wealth. Our negative impact can be explained that when FDI increases excessively and it is not used efficiently, it can be detrimental to the host country, thereby hindering economic wealth. This supports the resource curse hypothesis that countries that open their economy for FDI inflows do not benefit from it and hence, agrees with Gui-Diby (Citation2014), who found a negative effect of FDI on economic growth in 50 African countries in the period 1980–1994. This disagrees with recent work of Nguyen (Citation2022) who provide evidence to support a positive impact of FDI on economic growth. Our findings also disagrees with previous works by Lucas (Citation2005) and Catrinescu et al. (Citation2009) who supported that FDIs lead to positive economic growth. This is because foreign direct investment that flows to resource-rich countries produces negative spillover effects or no effect on an economy’s transition (Djankov & Hoekman, Citation2000; Konings, Citation2001; Sabirianova Peter et al., Citation2005). Therefore, countries that develop and grow their investment channels, through FDI inflows do not impact economic wealth directly.

In general, we can be deduced from our results and discussions above that FDI can be an important channel through which entrepreneurship impact economic growth. In view of that, the next section provides the results showing the impact of FDI on the entrepreneurship-wealth nexus.

8.3. Interactive Effects of Entrepreneurship and FDI Inflows on Economic Wealth

We have earlier found that entrepreneurship has a negative impact on economic wealth but the lag impact of entrepreneurship is positive in the determination process of economic wealth.

In this section, we argue that the influence of the initial level of entrepreneurship alone is not meaningful in determining economic wealth. We show that entrepreneurship complements or substitutes FDI inflows to generate an optimal level of economic wealth. Therefore, we interact the contemporaneous values of entrepreneurship variables with FDI inflows and regress on economic wealth.

From Table , the coefficients of ease of doing business are negative and significant (models 4). Similarly in Table , the coefficients of ease of doing business is negative and significant (model 8) while the coefficients of the interaction terms between the ease of doing business and FDI inflows is positive and significant (model 8). This implies that ease of doing business can substitute for FDI inflows in determining economic wealth. In model 10, minimum capital for starting business has a positive coefficient and the coefficient of the interaction term between minimum capital for starting business and FDI is positive. This shows that minimum capital for starting business complements FDI to promote economic wealth.

Table 6. Interaction Effect of Entrepreneurship and FDI on Economic Wealth

According to Asongu and Nwachukwu (Citation2018), it is necessary to calculate the marginal effects of interactions to obtain a meaningful economic interpretation. For instance, the marginal effect of the ease of doing business is −0.00102[−0.00194 + (0.00023*FDI inflows)] (see model 8), when FDI inflow assumes an average of 4.036 (see, Table ). The marginal effect is negative but less negative compared to the unconditional impact. This suggests that the negative impact of ease of doing business on economic wealth is reduced at higher levels of FDI inflows. Moreover, the marginal effect of minimum capital of business start-up is positive: 0.0245[0.0192 + (0.00132* FDI inflows)] (see model 10), when FDI inflows assumes an average of 4.036 (see, Table ). This suggests that the positive impact of minimum capital of business start-up on economic wealth is amplified at higher levels of FDI inflows.

In general, entrepreneurship increases the economic wealth of people and entrepreneurs when there is more FDI inflows but the impact differ based on the kind of business activity an economy may engage in. Thus, countries that focus on enhancing FDI inflows are able to engage businesses and individuals (i.e. encourage or facilitate the entrepreneurships), which in turn has the potential to increase the economic wealth of people and businesses in the real sector of the economy. The implication is that good business environment should create more successful businesses, create more opportunities to start a business and generate income for entrepreneurs (Dreher & Gassebner, Citation2013) in other to drive economic wealth (Poschke, Citation2010). In support of Fritsch (Citation2008) who argued that entrepreneurship has several mechanisms through which it can affect economic wealth, we therefore provide evidence that entrepreneurship reduces economic wealth but improves economic wealth when FDI inflows increase in a country.

9. Conclusion and policy implication

The paper examines the combined effect of entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment inflows on economic wealth. The motivation for this study is that while entrepreneurship is seen as a driver of value creation and economic wealth, Africa has lagged behind in improving economic wealth through entrepreneurship and FDI inflows in the short term. In this sense, the study seeks to present new evidence on how entrepreneurship and FDI inflows jointly affect economic wealth. To this end, this study uses a dynamic GMM system for a panel dataset of 52 African economies between 2006 and 2020. First, the study examines the impact of FDI on entrepreneurship. Next, the independent effect of entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment on economic wealth is presented. Finally, the study interacts with entrepreneurship and FDI flows to examine their true impact on economic wealth.

The study shows that FDI inflows have a varying impact on entrepreneurship depending on the nature of business activities or measure of entrepreneurship of a country. We show that resource curse hypothesis induces a negative effect of FDI on the ease of doing business but FDI increases the business capital start-ups of entrepreneurs. This means that countries that open their economies for conducive business activities attract smaller FDI inflows due to the natural resource curse while FDI inflows into an economy, provides an immediate source of investment capital to entrepreneurs to start a business—hence, a blessing to entrepreneurship. The implication is that a country’s framework on trade and entrepreneurship should be strengthened to make such economy an investment hub. We provide evidence to support that entrepreneurship reduces economic wealth in the short term but in the long-term entrepreneurship positively affect economic wealth. This suggests that countries with strong framework for entrepreneurship models are able to increase economic wealth in the long run. The implication is that governments and trade economists should strengthen their trade polices within the short term to better attract FDI inflows into the productive sectors of the economy, and hence promoting entrepreneurship. The results show that FDI inflows increase economic wealth and that FDI is an important channel through which entrepreneurship can impact economic wealth.

We find evidence to support that ease of doing business and FDI inflows are substitutes while minimum capital of starting business complements FDI inflows in determining economic wealth. Therefore, based on the nature of entrepreneurship of a country, entrepreneurship, in general, has a substitutability effect and complementarity effect on economic wealth when conditioned on FDI inflows. The marginal effect shows that the negative impact of ease of doing business on economic wealth is reduced when interacted with FDI inflows while the positive impact of minimum capital of starting business on economic wealth is enhanced when interacted with FDI inflows. Thus, entrepreneurship increases the economic wealth of people and entrepreneurs when a country increases its FDI inflows. In conclusion, entrepreneurship reduces economic wealth but improves economic wealth when the level of FDI inflows increases in a country.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

In general, the study makes novel contributions to the strand of literature by providing evidence to support that FDI can help shape the complex relationship between measures of entrepreneurship and economic wealth. The study helps policymakers, practitioners and researchers to understand the role that globalization and players of the world market economies play in explaining the effect of business environment or entrepreneurship on economic wealth in the regions.

Based on the findings of this study, countries in Africa as well as developing countries should have appropriate trade policies to reverse the negative impact of FDI on entrepreneurship. In particular, the policymakers should focus more on improving trade and investment conditions (foreign investments) as well as improving policies that increase the absorptive capacity to FDI inflows in order to promote entrepreneurship development. Policymakers should strengthen their trade polices within the short-term to better attract FDI inflows into the productive sectors of the economy, and hence promoting entrepreneurship. Countries should bring up strategies that promote economic wealth of individuals, society and entrepreneurs through prudent business development strategies and FDI supports in the short term. The level of trade and entrepreneurship among participants should be improved comprehensively in market economies, aiming to maintain an effective and robust entrepreneurship framework that captures the dimensions of entrepreneurship and promote the wealth of individuals and the economy at large. Appropriate policies that allow the complementarity framework of entrepreneurship and FDI (that is effective and favorable trade environment protocols) to be put in place to facilitate the role FDI play in shaping the entrepreneurship-wealth nexus. Thus, policies and trade regulations are needed to reverse the resource curse and the adverse effects of entrepreneurship on economic wealth through FDI.

9.1. Limitation and future research recommendation

The study is limited to only African economies. In addition, it was not able to collect data on various dimensions and characteristics of entrepreneurship as well as measures of private capital flows or financial sector development from different economies in Africa and developing economies perspective. Acquiring these data were very difficult because some are not available publicly as a secondary source. Again, the empirical framework presented in the study does not allow to interpret the estimates (interaction coefficients) as causal effects. Future research is required to explore this study (including data extension) to other regions in the world to reveal how applicable this model fits the other part of the world. Future studies should explore alternative measures of entrepreneurship and private capital flows from different market economies to ascertain their impacts on economic growth, by using different methodological and contextual approaches.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acheampong, G., & Hinson, R. E. (2019). Benefitting from alter resources: Network diffusion and SME survival. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 31(2), 141–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2018.1462620

- Ács, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2014). National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Research Policy, 43(3), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.016

- Acs, Z. J., & Varga, A. (2005). Entrepreneurship, agglomeration and technological change. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1998-4

- Adams, S., & Opoku, E. E. O. (2015). Foreign direct investment, regulations, and growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy, 47, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2015.07.001

- Adepoju, U. (2017). Ease of doing business and economic growth. Unpublished Working Paper, Department of Economics of the University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario

- Adusei, M. (2016). Does entrepreneurship promote economic growth in Africa? African Development Review, 28(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12190

- Agbloyor, E. K. (2019). Foreign direct investment, political business cycles and welfare in Africa. Journal of International Development, 31(5), 345–373.

- Agbloyor, E. K., Abor, J. Y., Adjasi, C. K. D., & Yawson, A. (2014). Private capital flows and economic growth in Africa: The role of domestic financial markets. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 30, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2014.02.003

- Agbloyor, E. K., Gyeke‐Dako, A., Kuipo, R., & Abor, J. Y. (2016). Foreign direct investment and economic growth in SSA: The role of institutions. Thunderbird International Business Review, 58(5), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21791

- Albulescu, C. T., & Draghici, A. (2016). Entrepreneurial activity and national innovative capacity in selected European countries. Int J Entrep Innov, 17(3), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750316655902

- Albulescu, C. T., & Tămăşilă, M. (2014). The impact of FDI on entrepreneurship in the European countries procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 124(2014), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.480

- Alfaro, L., Areendam, C., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Sayek, S. (2004). FDI and economic growth: The role of local financial markets. Journal of International Economics, 64(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(03)00081-3

- Allison, V. L. (2012). Award-winning undergraduate paper: Econometric analysis of childhood poverty in Georgia. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 94(2), 595–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aar151

- Alvarez, S. A., & Busenitz, L. W. (2001). A resource-based theory of entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 27(6), 755–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700609

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-D

- Asongu, S. A., & Nwachukwu, J. C. (2018). Openness, ICT and entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa. Information Technology & People.

- Asongu, S. A., & Tchamyou, V. S. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship on knowledge economy in Africa. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 8(1), 101–131.

- Atems, B., & Shand, G. (2018). An empirical analysis of the relationship between entrepreneurship and income inequality. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 905–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9984-1

- Audretsch, D., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional Studies, 38(8), 949–959. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340042000280956

- Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2004a). Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional Studies, 38(8), 949–959. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340042000280956

- Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2004c). Does entrepreneurship capital matter. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(5), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00055.x

- Awad, A., & Ragab, H. (2018). The economic growth and foreign direct investment nexus: Does democracy matter? Evidence from African countries. Thunderbird International Business Review, 60(4), 565–575. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21948

- Ayyagari, M., & Kosová, R. (2010). Does FDI facilitate domestic entry? Evidence from the Czech Republic. Review of International Economics, 18(1), 14-–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2009.00854.x

- Batrancea, L., Rathnaswamy, M. K., & Batrancea, I. (2022). A panel data analysis on determinants of economic growth in seven non-BCBS Countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 13(2), 1651–1665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00785-y.

- Baumol, W. J. (1996). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)00014-X

- Belitski, M., & Desai, S. (2016). Creativity, entrepreneurship and economic development: City-level evidence on creativity spilloverof entrepreneurship. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(6), 1354–1376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9446-3

- Bjorvatn, K., Farzanegan, M. R., & Schneider, F. (2012). Resource curse and power balance: Evidence from oil-rich countries. World Development, 40(7), 1308–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.03.003

- Block, J. H., Fisch, C. O., & van Praag, M. (2017). The Schumpeterian entrepreneur: A review of the empirical evidence on the antecedents, behaviour and consequences of innovative entrepreneurship. Industry and Innovation, 24(1), 61–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2016.1216397

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

- Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses (pp. 63–82). Political analysis.

- Canare, T. (2018). The effect of ease of doing business on firm creation. Annals of Economics and Finance, 19(2), 555–584.

- Catrinescu, N., Leon Ledesma, M., Piracha, M., & Quillin, B. (2009). Remittances, institutions, and economic growth. World development, Elsevier, 37(1), 81–92.

- Christiansen, H., & Ogutcu, M. (2002, December 5-6). Foreign direct investment for development – Maximizing benefits, minimizing costs. OCDE, Global forum on international investment. Attracting foreign direct investment for development.

- Coccia, M. (2011). The interaction between public and private R&D expenditure and national productivity. Prometheus, 29(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/08109028.2011.601079

- Compton, R. A., & Giedeman, D. C. (2011). Panel evidence on finance, institutions and economic growth. Applied Economics, 43(25), 3523–3547. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036841003670713

- Cramer, C., Sender, J., & Oqubay, A. (2020). African economic development: Evidence, theory, policy. Oxford University Press.

- Dau, L. A., & Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2014). To formalize or not to formalize: Entrepreneurship and pro-market institutions. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 668–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.05.002

- De Backer, K., & Sleuwaegen, L. (2003). Does foreign direct investment crowd out domestic entrepreneurship? Review of Industrial Organization, 22(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022180317898

- Djankov, S., & Hoekman, B. (2000). Foreign investment and productivity growth in Czech enterprises. World Bank Economic Review, 14(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/14.1.49

- Doran, J., McCarthy, N., & O’Connor, M. (2018). The role of entrepreneurship in stimulating economic growth in developed and developing countries. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1), 1442093. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2018.1442093

- Doytch, N. (2012). FDI and entrepreneurship in developing countries. GSTF Business Review (GBR), 1(3), 120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.480

- Dreher, A., & Gassebner, M. (2013). Greasing the wheels? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. Public Choice, 155(3–4), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9871-2

- Durham, J. B. (2004). Absorptive capacity and the effects of foreign direct investment and equity foreign portfolio investment on economic growth. European economic review, 48(2), 285–306.

- Dutta, N., & Sobel, R. (2016). Does corruption ever help entrepreneurship? Small Business Economics, 47(1), 179–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9728-7

- Fahed, W. B. (2013). The effect of entrepreneurship on foreign direct investment. In Proceedings of world academy of science, engineering and technology (Vol. 78, pp. 242). World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology (WASET).

- Ferreira, J. J., Fayolle, A., Fernandes, C., & Raposo, M. (2017). Effects of Schumpeterian and Kirznerian entrepreneurship on economic growth: Panel data evidence. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(1–2), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1255431

- Fritsch, M. (2008). How does new business formation affect regional development? Introduction to the special issue. Small Business Economics, 30(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9057-y

- Fritsch, M. (2013). New business formation and regional development: A survey and assessment of the evidence. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 9(3), 249–364.

- Fritsch, M., & Mueller, P. (2004). Effects of new business formation on regional development over time. Regional Studies, 38(8), 961–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340042000280965

- Glancey, K. S., & McQuaid, R. W. (2000). Public policies to promote entrepreneurship. In Entrepreneurial economics (pp. 172–201). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Görg, H., & Strobl, E. (2002). Multinational Companies and Indigenous Development: An Empirical Analysis. European Economic Review, 46(7), 1305–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00146-5

- Gui-Diby, S. L. (2014). Impact of foreign direct investments on economic growth in Africa: Evidence from three decades of panel data analyses. Research in Economics, 68(3), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2014.04.003

- Gui-Diby, S. L., & Renard, M. F. (2015). Foreign direct investment inflows and the industrialization of African countries. World Development, 74, 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.005

- Herrington, M., Kew, J., & Kew, P. (2010). Global entrepreneurship monitor.

- Heshmati, A. (ed.) (2018). Determinants of economic growth in Africa. Springer, 2018

- Hessels, J., & Van Stel, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship, export orientation, and economic growth. Small Business Economics, 37(2), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9233-3

- Hillbom, E., & Green, E. (2019). An economic history of development in Sub-Saharan Africa: Economic transformations and political changes. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huang, X., & Chen, Y. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth within a city. Business, 1(3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses1030011

- Ibrahim, R. L., & Ajide, K. B. (2022a). Trade facilitation, institutional quality, and sustainable environment: Renewed evidence from Sub-Saharan African countries. Journal of African Business, 23(2), 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2020.1826886

- Ibrahim, R. L., & Ajide, K. B. (2022b). Trade facilitation and environmental quality: Empirical evidence from some selected African countries. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(1), 1282–1312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01497-8

- Ibrahim, R. L., & Ajide, K. B. (2022c). Is trade facilitation a deterrent or stimulus for foreign direct investment in Africa? The International Trade Journal, 36(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853908.2021.1937407

- Ivanović-Đukić, M., Krstić, B., & Rađenović, T. (2022). Entrepreneurship and economic growth in emerging markets: An empirical analysis. Acta Oeconomica, 72(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1556/032.2022.00004

- Jiahao, S., Ibrahim, R. L., Bello, K. A., & Oke, D. M. (2022). Trade facilitation, institutions, and sustainable economic growth. Empirical evidence from Sub‐Saharan Africa. African Development Review.

- Kim, P. H., & Li, M. (2012) Injecting demand through spillovers: Foreign direct investment, domestic socio-political conditions, and host-country entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Business Venturing. forthcoming. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.10.004.

- Kim, J., Petalcorin, C. C., Park, D., Jinjarak, Y., & Quising, P. (2022). Entrepreneurship and economic growth: A cross-section empirical analysis. Asian Development Bank. http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/WPS220399-2

- Konings, J. (2001). The effects of foreign direct investment on domestic firms: Evidence from firm panel data in emerging economies. Economics of Transition, 9(3), 619–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0351.00091