Abstract

The majority of research on competitiveness is based on the analysis of quantitative data. There is significantly less research on the soft elements of competitiveness. This research aims to fill this gap in the literature. Starting from the national culture, the authors investigated the impact of trust characteristics of organisational culture on the characteristics of strategy, knowledge management and organisational effectiveness. Respondents (∑943) from five countries on three continents (USA, China, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania) took part in the quantitative research conducted with a questionnaire survey. The analysis was performed using the SPSS and AMOS 27 programs based on the SEM model. The results show that there is a significant relationship between the examined elements of competitiveness (strategy and management), which also show a significant relationship with organisational trust. Through a culture of trust, the interaction between the elements has a significant impact on the characteristics influencing the efficient operation of the organisation and its competitiveness, regardless of the value of Hofstede’s characteristics of different national cultures.

1. Introduction

Competitive economies can only strengthen their position in international markets under knowledge-based (innovative) conditions (Abrams et al., Citation2003). In this process, the acquisition, retention, sharing, continuous improvement and use of knowledge play a prominent role (Blendinger & Michalski, Citation2018; Ismail et al., Citation2017). It means that investing in human capital and knowledge, valuing the workforce, and taking their needs into account are a prerequisite for competitiveness (Alkhurshan & Rjoub, Citation2020). Educating employees and preparing them for innovation and research development is a long-term investment, the return of which is possible with well-designed working conditions and organisational culture (Hadas, Citation2020). It also means that knowledge and its necessary exploitation is only possible under the conditions of a trust-based organisational culture, where employees and managers turn to each another with the same thinking, value judgment, and trust, and share their knowledge, help each other, work together, and create competitive products and services (Fantazy & Tipu, Citation2019). In other words, knowledge and trust go hand in hand for successful operation and competitiveness, and the need to utilise knowledge without trust is fruitless (Ivanova et al., Citation2019; Piotrowska, Citation2019).

Research on competitiveness is topical because the competitive situation is strengthening in both domestic and international markets, the economic environment is changing more and more intensively, and the pandemic has eliminated several former trends (Alexa et al., Citation2019). Thus, the asset that has previously provided a competitive advantage for a country or an organisation has become unpredictable in how it will perform in the next period (Van Fan et al., Citation2018).

Due to rapid and unpredictable changes, the World Economic Forum (WEF) introduced a new methodology for rating the competitiveness of nations in 2018, including the concept of the Fourth Industrial Revolution in the definition of competitiveness. The methodology emphasises the role of human capital, innovation, resilience and agility, which are not only drivers of economic success in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, but also defining characteristics. This new approach relies more than before on the impact of soft factors.

At the beginning of the study, we would like to state that, since an economy can be regarded as a complex system, an interpretation of competitiveness is needed at both corporate and national levels, as they mutually influence each other’s performance. Competitiveness can be examined with a system-based approach at all levels, and the results can only be qualified after an aggregate analysis. The present study addresses a single element of this system, namely, it examines organisational functioning through the exploration of the relationship between knowledge management and trust, and assesses their combined impact on the essential characteristics of organisational functioning.

The aim of the research is to compare the behaviour and thinking of distant cultures from several continents through the analysis of the above mentioned relationships, and to assess the factors in terms of their impact on competitiveness. The research is not intended to quantify other indicators of the competitiveness of individual countries, to incorporate them into a research model, or to compare previous research results, international reports or GDP.

The quantitative research was based on the latest research results (journal articles, studies), and the questionnaire survey way with the help of respondents (∑943 people) from five countries on three continents (USA, China, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania). The analysis was performed using the SPSS 27 and AMOS 27 programs based on the SEM model.

There was a serious difficulty in collecting the sample and in tuning different cultures and thinking to the same level, in order to assess the questions on an equal footing. As a result, certain characteristics defined in the original model were neglected, and were omitted from the final model. Thus, the sample cannot be considered representative, the results are true only to those involved in the present research. Although the results are indicative, there is raison d’être to continue the research for further evidence.

In the following chapters, you can read a brief theoretical overview of the significance of economic success and culture, and the cultural characteristics of the nations examined, the essence of trust and knowledge management are presented. This is followed by a presentation of the research methodology and the practical examinations. The author states the aim of the research topic, its focus, explains its originality, and introduces its structure.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. The aspect of economic success

The interpretation, conceptual system, and calculation method of competitiveness change from time to time. The framework of the study does not allow (and does not require) a detailed discussion of these, so we focus only on the approach that is relevant to understanding the research. Adam Smith was the first to take the view that markets solve everything, and that the solution is clear and optimal (Smith, Citation2006). Later, in accordance with the style of the era, Arrow and Debreu (Citation1954) articulated this in mathematical form as well, and thus won the Nobel Prize.

Traditional, “mainstream” economics does not address the usefulness of “soft indicators”; in the opinion of its representatives, the only important indicator is the one that can be measured and modelled.

The basis of our thinking is that economic success (the improvement of competitiveness) cannot be solved by focussing only on quantifiable indicators. It is necessary to take into account the so-called soft factors such as cultural capital, regional capital, community capital, and social capital. Several national economies and their organisations prefer the constant strengthening of human capital, natural/environmental capital and social capital (IMD Talent ranking Citation2018; Kovács & Kot, Citation2017).

The question may be raised how economies can compete. With natural resources (oil, gas, land), cheap resources, wages and subsidies, knowledge, creativity, and innovation. This means that besides determined, hard and quality work, knowledge, and intellectual skills, intellectual capital have also become dominant factors of competitiveness (Carbonell & Nassè, Citation2021). To the question of what causes good economic performance, competitiveness, and growth, the answer is sought by many in a variety of approaches. (This is the thinking behind the WEF’s new calculation methodology.) One of these possible ways of thinking, which we will follow, and present in the following, is knowledge management through the characteristics of a trust-based culture (Fukuyama, Citation1995; Luo & Lin, Citation2022; Putnam, Citation1995).

2.2. Briefly about efficiency

Efficiency means that the result is achieved with less (smaller) input (time, material, intellectual, etc.) in an organisation. Drucker (Citation2006) put the concept of efficiency in simple terms. In his view, efficiency is doing the right things, while effectiveness is doing things right. Both assume that it is possible to determine what the right outcome is and what things need to be done to achieve it.

Organisational effectiveness (as well as competitiveness) is a broad concept, in the evaluation of which, all organisational processes can be brought to the fore. Thus, the influence of the cultural values of an organisation can have an impact in all areas, such as reducing costs (Kovács & Kot, Citation2017), optimising processes (Van Fan et al., Citation2018), building strategy (Carbonell & Nassè, Citation2021), increasing emotional intelligence (Cui, Citation2021), strengthening a culture of trust (Brockman et al., Citation2018), etc. A small percentage of publications in the literature target these relationships. This fact justifies one of the focuses of our research, the demonstration of the impact of trust on organizational effectiveness.

Unfortunately, few organisations recognise the power of organisational effectiveness. Those that do, achieve outstanding success, provided they apply it. Organizational effectiveness is based on the speed of information flow, the quality of communication, the methods of knowledge transfer, collaboration, on the whole, cultural values. When employees speak a common language in accomplishing tasks, respect each other and each other’s work, and work together to achieve organizational goals, misunderstandings and problems are reduced and work is accelerated. An organisation, whose people know how to transfer and receive information, how to solve problems collaboratively, quickly and effectively building on trust, will gain a market advantage.

2.3. The importance of culture

Generally speaking, culture is the sum of material and immaterial values created by humanity. An area of culture, or its manifestation in an era, among a people. The impact of culture on competitiveness is reflected in the competitive products of a nation, in export performance, high value-added products, quality services, the creation of demanding, knowledge-based jobs, in the creation of a cultured environment, etc. (Florida, Citation2003). Dengjian (Citation2001) compared the competitiveness result of the USA and Japan in his study. He found that the cultural factor plays a significant role in joint development processes. Using an integrated model, he presents how national learning patterns that affect innovation differ from one another. The model provides a comprehensive picture of the dynamic relationships between culture, technology, organisations and government, and the characteristics of joint development (Tseng, Citation2010).

Organisational culture can be interpreted as the value system of an organisation, which shows how they perceive and react to their environment (Keyton, Citation2015). Many believe that culture does exist conceptually, but it cannot be measured or monitored. In his study, Nold (Citation2012) sheds light on organisational culture from a new perspective. He treats it as a significant resource of knowledge that supports the intellectual (knowledge) assets of a company’s management. In his opinion, organisations should see culture as a competitive factor (a resource) that must be managed in order to become a learning organisation, and knowledge management initiatives should be seen as an opportunity to change culture.

In the practical part of our study, starting from the characteristics of the national culture and touching upon the organisational culture, we present the individual behaviour and thinking, which are considered a factor determining both the cultural characteristics and competitiveness.

2.4. Characteristics of the studied cultures

The characteristics of the cultures involved in the research are described along the components studied by Hofstede in as much depth as required to understand research results.

In order to provide the widest possible insight into the relationships between the studied parameters, the nations involved in the research come from three continents (Europe, Asia, North America). Their most important characteristics are shown in Table below.

Table 1. Hofstede’s characteristics of the studied nations

The characteristics of culture show very different values, even in the case of European nations. The most distant nations are Slovakia, Romania, and China, the significance of which will later be important for building relationships of trust. For the same nations, the indicator of individualism is low, which is interesting in terms of cooperation and knowledge sharing—collectivist nations are inclined to share their information and work together.

In particular, the Masculinity indicator carries the characteristics of competitiveness. The high values indicate that the society primarily prefers a competitive approach: being successful is the most important thing, which is strongly present in the operation of organisations. In this respect, Slovakia is at the forefront, followed by Hungary, and this is the least important driving force for Romania. In the case of a low value, quality life indicates success, paying attention to the other, family, and leisure time are the typical preference over work. (Fully in line with the indicator of individualism.) The USA and China show a more balanced value for this parameter. Uncertainty avoidance can be associated with the tolerance of an unpredictable future, openness to the new willingness to take risks, and entrepreneurship. In the case of Romanian and Hungary, the high value shows less flexibility and fear of the uncertain and unpredictable future, while among the European states, Slovakia is the most enterprising nation. The lowest value of China can be confirmed through the many small and family businesses (Techo, Citation2017).

Long Term Orientation is about cherishing the values of the past and preparing for the future. It is no coincidence that the Chinese are at the forefront, followed by Slovakia, while the USA is the last in the line.

In the Indulgence indicator, people’s past and present are confronted. Weak control is accompanied by easy forgiveness and tolerance, while otherwise no serious attention is paid to controlling the compensation for free time and desires. The values of the nations, with the exception of the USA (also referred to as “the melting pot”), are relatively close to one other. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/china,the-usa/

From the point of view of our research, the values of Masculinity and Uncertainty Avoidance are important for the assessment of competitiveness, and the values of Individualism and Power Distance are important for the assessment of knowledge sharing and trust.

A characteristic, which fundamentally affects an individual’s working behaviour, and also manifests at the organisational level, and which can be deduced from the national culture, is presented in the next chapter, namely, trust.

2.5. The importance of trust

Trust is the source of economic success. In the most competitive countries, social capital is strong, common values, traditions, and culture strengthen the social capital. Because national culture fundamentally determines the cultural characteristics of organisations, firms with a higher level of trust-based culture are more likely to outperform firms with a lower level of trust.

Organisational culture significantly supports or hinders successful knowledge management initiatives (Hadas, Citation2020). According to Fantazy and Tipu’s study (2019), competitive organisational culture and knowledge development mutually influence each other, and have a positive impact on organisational performance.

Deif and Van Beek (Citation2019) examined competitiveness in relation to the issues of talent management. The relationship between talent and competitiveness manifests through the steps of knowledge creation, transfer, and development. The successful organisational operation defined in the strategy and supported by the culture depends on the mentioned relationships (Hadas, Citation2020; Covey, Citation2022). Although there is no consensus in the literature on the definition of trust, practice and research results have proven that trust is an important predictor of results, cooperative behaviour, organisational commitment, and employee loyalty (Zhang et al. Citation2008; Yu, Citation2019). It is the foundation of any workplace culture where the employees are productive and strive for continuous innovation (Twaronite, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2020).

While managers in organisations would like their teams to become more effective, many prefer their usual, traditional management methods (Kashyap and Rangnekar, Citation2016). They focus primarily on strategic plans, aims, the rationalisation of processes, reducing inefficiencies, while others see the recipe for success in allowances, bonuses, and flexible working (Seppala, Citation2015; Shao, Citation2014). A study by Cameron et al. (Citation2011) has revealed that an organisation can successfully operate without the introduction of various allowances or new processes. They gathered supportive practices such as increasing positive emotions, attracting and strengthening employees, and solidarity. To achieve all these, a change of culture supported by the upper management, the methods of small steps, and the shaping of organisational solidarity are required. Trust is, then, the currency of successful organisations, strengthened by the cooperation of team members who trust each other, who are more productive, creative and resilient by building on trust, which increases the general efficiency of the organisation (Jardon & Martinez-Cobas, Citation2021; Twaronite, Citation2016). In addition to emphasising trust, it is worth mentioning its opposite: distrust. According to participants of Twaronite’s (Citation2016) research, the five most important reasons for employee distrust about the organisation are unfair assessment, unequal opportunities for pay and promotion, lack of strong leadership, high fluctuation, and the lack of cooperating teams.

According to research under COVID-19, managers, who could not directly monitor their employees, (primarily during remote working), had difficulty in trusting their employees to actually work. The negative consequence of this is unreasonable expectations, which jeopardise work-life balance, thus increasing the development of various forms of stress at work. This type of managerial behaviour can generate a sort of negative spiral that can lead to a decrease in employee motivation, along with productivity and performance, and a reciprocity of distrust (Hernaus & Černe, Citation2022).

Research by Mohamed et al. (Citation2012) examined the relationship between organisational commitment, trust and satisfaction. Their results showed that there is a positive relationship between organisational trust and emotional commitment. Paliszkiewicz’s (Citation2012) research analysed the relationship between organisational trust and performance, and found that organisational trust and its impact on the performance of the organisation are in close connection with managerial trust. The results of further research, which can be related to learning, knowledge, and talent development, belong to the topic of knowledge management (Ng, Citation2022).

2.6. Knowledge management

Learning is one of the fundamental processes of organisation functioning and survival, when colleagues interact with each other for information exchange, asking for or providing help, and sharing knowledge (Carmeli et al., Citation2009). Newman & Conrad, Citation2000) research prefers supportive management, relationships with colleagues, and supportive organisational practices, which also increase knowledge management, commitment, creativity, innovation, and, last but not least, individual and organisational performance. Overall, it can be described as an inter-employee belief that serves as a basis for the security of interpersonal risk taking in organisational operation (Carmeli et al., Citation2009). In terms of its manifestation, it is tacit, as individuals take it for granted, and is rarely, hardly ever discussed openly, it stems from mutual trust and respect (Carmeli et al., Citation2009; Edmondson, Citation1999; Castellani, Citation2021).

Knowledge Management is a business model embracing knowledge as an organizational asset to drive sustainable business advantage (Yasir et al., Citation2017). It is a management discipline that promotes an integrated approach to create, identify, evaluate, capture, enhance, share and apply an enterprise’s intellectual capital (Davenport & Prusak, Citation1998; Skytt & Winther, Citation2011).

The definition supports the introduction that investment in intellectual capital is key to competitiveness (Y.L.A. Lee et al., Citation2020). The need for developing knowledge management systems, and their integration into organisational operation dates back decades in Western societies, while it is a less preferred business model in less successful economies such as in Central and Eastern Europe. The need for system building is often formulated at the level of management and of strategy, but few firms reach the level of operative implementation (Mueller, Citation2012). Isolated asset uses or methodological solutions are more often recognisable in corporate operations, but their presence is not typical at the level of an integrated operating model (Bouncken et al., Citation2021; Rajkovic et al., Citation2021).

In recent years, there have been a lot of publications on research and findings about the relationship between knowledge sharing and trust (Abrams et al., Citation2003; Darroch, Citation2005; J. Lee et al., Citation2019; Lewicki et al., Citation1998; Paliszkiewicz & Koohang, Citation2013; Sankowska, Citation2013). Without exception, all of them confirm that trust influences the act of knowledge sharing, its quality and depth, so it can be closely related to the building and operation of organisational knowledge management systems (Massaro et al., Citation2019). The present study does not intend to increase the list of studies proving these relationships, but the research results undoubtedly touch upon this relationship as well.

Based on the above chapters, it can be said that competitiveness and economic success are interrelated with the so-called soft factors, and this back-and-forth effect prevails. These are long-term factors; focussing on short-term economic indicators can destroy their values, ignoring them is unused potential. For the “health” of society, these factors (e.g., workplace culture, cooperation) are often more important than economic results. Research questions based on the above: What is the relationship between trust and the organisational strategy that favours knowledge? How does trust-based organisational culture affect the functioning of the elements of a knowledge management system? Is there a relationship, and if so, how strong is it between strategy, KM elements and trust? Does organisational trust, and to what extent, affect the processes that influence competitiveness and ensure organisational success?

In the following, we carry out the examination of the hypotheses based on the research questions through the analysis of “soft” factors and their joint impact that fundamentally influence organisational competitiveness, presenting the results of our empirical research

3. Research objective, methodology and data

Between 2016 and 2020, we conducted a multi-step study on organisational trust to explore the effect of the so-called “soft” factors that influence competitiveness, namely, the relationship between culture, organisational trust, and knowledge management processes. In this context, we assessed whether the managers pay attention to the economic consequences of trust or its lack, and the characteristics of the relationships between “soft” factors that influence competitiveness.

In the first phase, the research involved only organisations in Hungary, and in the second phase, the practice of companies in Slovakia and Romania were observed. In the last phase, moving out of the cultural environment of European countries, the operation of Chinese and American organisations were analysed.

3.1. The sample

The selection of the examined nations was based on the idea of looking at how the factors influencing success work in the case of nations similar to our country (Hungary), in terms of historical, economic, and political background. Seeing the research results, the move toward other continents was motivated by our curiosity about how different the behaviour of cultures far from European thinking is in this area. Our goal was to examine nations that are different from each other. This is how the American and Asian continents were selected, within them, concerning competitiveness and the level of development, the USA and China.

Although the two countries show significant differences in economic performance from the Central and Eastern European nations studied, these results are based on quantitative (mainly GDP-based) accounts. These figures exclude all the influencing factors that are the focus of this study. The authors have prepared an overview table that gives a more accurate picture of the actual performance of the nations studied (GDP per capita, GDP per capita PPP), supplemented by the World Happiness Indicator (WHI) values. The calculation of WHI is based on 6 components, one of which is the log. (It can be seen that if the soft components are included, the perception changes.) If the GDP per capita is subtracted from the six characteristic values of the WHI, the influencing effects of the soft components remain. Table clearly shows that it is worth further analysing the values of the quantitative indicators to see the effects of real (and not directly or difficult to detect) influencing factors. (The values show the analyses of the year 2021.) Since the aim of the research is not to compare the usual test results of the competitiveness of countries (GDP) but to detect other culture-based effects at the organisational level, the difference between the parametric values of competitiveness (GDP) is not relevant for the present research. (It is interesting to note, however, how soft elements play a decisive role even in a country with a significantly higher GDP. This also proves the validity of our research.) As shown in the table, the WHI index for all the nations studied is around 6 on a scale of 0–10, from which, if GDP per capita is subtracted, the values fall between 4 and 5, which only show the impact of the soft elements. They thus provide a nearly identical basis for analysis.

Table 2. GDP, GDP per capita and WHI index of the countries

No criteria were set for the organisations included in the study. Since the authors have examined the parameters derived from the characteristics of national culture at the organisational level, other characteristics of the organisations have been ignored. The target group was the employed adult population. When selecting respondents, the heads of the organisations were asked to nominate those who had the best insight into the areas under study. From the staff they nominated, respondents were selected at random. The total number of respondents to the questionnaire was 943. Inquiries were made in person, via phone or e-mail, and on community forums. Respondent willingness was above 10%.

3.2. Query method

Research participants were required to complete an online questionnaire in anonymous form. During the pilot survey, 10 asked respondents completed the questionnaire, during which they had no interpretability problems, so all (35) questions remained unchanged in the questionnaire. There were four open questions, the others were closed questions. Of the responses received, 15 questionnaires were found during the clarification that could not be used for further analysis. The questionnaires were translated into the languages of all nations for the same level of comprehensibility. The structure of the questionnaire is shown in Table .

Table 3. The structure of the questionnaire

3.3. Evaluation of the sample

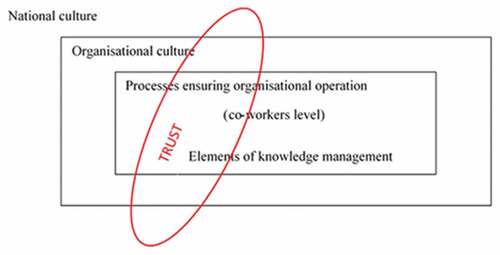

In the first phase, a model was set up that summarises the theoretical relationships between the factors introduced in the theoretical section (Figure ).

Qualifiable parameters were assigned to each level of the model, the assessment of which was based on the questions the respondents raised in the questionnaire.

During the analysis, the existence and significance of relationships derived from each level of the model were examined. As mentioned in the introduction, the present study focuses on the “soft” elements of competitiveness and the organisational level, so, based on the system of relationships in the model, it presents the examination of the following hypotheses:

H1. Organisational trust is in a close and positive relationship with the identifiable knowledge management strategy within organisations.

H2. Organisational trust is in a close and positive relationship with the identifiable knowledge management elements within organisations.

H3. Organisational trust positively impacts the efficiency of organisational operation, on optimal functioning.

To analyse the above hypotheses, uni- and multivariate statistical methods (frequency, mean, standard deviation, factor analysis, ANOVA) and SEM modelling were used, with the help of the SPSS Statistics 27 and SPSS AMOS 27 programs. In the following, the research results are presented.

4. Results and discussion

The characteristics of the sample are shown in Table .

Table 4. Specification of the sample

By industry, the most typical occurrence for the total sample: 14.6 % education, 10.1% manufacturing industry, 12.4% trade—service, 11.7% transport—storage, 8.9% financial services.

European respondents (Hungarian, Romanian and Slovak) were included in the sample in almost equal proportions. As the WHI for these countries is almost the same (see, Table ), this distribution of the sample is considered appropriate for this study. The answers of the American respondents are included with the smallest number. (Presumably, due to the focus of the topic, the Americans’ interest was less motivated, (see Characteristics of the national culture), so during the clarification of the sample, about 20% had to be omitted from further analyses.)

Participants were required to rate a pre-formulated definition about trust by marking their level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale. The definition was: “A very high level of mutual agreement and affection, where we no longer consider it necessary to monitor the other party’s honesty, goodwill, values, and deeds, but we know for sure that he/she will think and do the best things possible. The full understanding of the other party.” On the scale, one meant “strongly disagree”, and five meant “strongly agree”. The mean of the given answer was 3,56, while the standard deviation was,978, that is, the respondents thought similarly about the statement and accepted the definition formulated by the authors.

After that, the respondents were requested to qualify pre-formulated statements on a five-point Likert scale regarding their own organisational practices. The statements intended to explore the characteristics of organisational strategy, the importance of knowledge, the elements of knowledge management, trust, and the impact trust has on organisational functioning. On the scale one meant strong disagreement, while five meant strong agreement. The statements, the mean and standard deviation of responses are summarised in Table .

Table 5. Statistical results of the examined organisational characteristics

The abbreviations in the table are letter designations for the variables in each study area. (KM) elements of knowledge management, (T) trust, (S) strategy, and (E) efficiency. The mean and standard deviation data show that, in the case of the examined organisations, the application of knowledge management elements is better than average, which is also confirmed by the knowledge-intensive thinking appearing at the strategic level. Trust appears to be less strong in relation to the knowledge management elements of the organisations, although the organisations are aware of its positive impact on organisational functioning and competitiveness. The relatively high value of standard deviations shows that respondents did not have the same opinion on the questions. The table separately shows the average values according to national cultures. The comparison of the individual cultures based on the ANOVA analyses in connection with three variables did not show a significant difference of opinion, (in connection with the strategy S1, S2, and about the elements of knowledge management in the case of KM3). Organisational practice was different in the other areas. The examination of the relationship between KM elements and strategy shows the highest average value in American organisations. (They considered their realisation in their organisations to be the most typical.) In the case of trust, the picture was more varied. It was rated with the highest values by the American, Chinese and Romanian respondents. This value judgment is also present in the assessment of the impact of trust on efficiency (see, Table .).

For further studies (to create an SEM model), the variables shown in Table have been compressed into factors (principal components). All variables were suitable for factor formation. The Cronbach’s alpha values were appropriate for all factors. Tables summarises the individual factors, factor components, and the Cronbach’s alpha values.

Table 6. Factors

The theoretical model was tested using the SPSS AMOS 27 program. With the help of the SEM (Structural Equation Modelling), we examined the relationship between one or more exogenous variables (independent), and one or more endogenous (dependent) variables (Byrne, Citation2016). Endogenous variables are directly or indirectly influenced by exogenous variables. The aim of the CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) study is to analyse the relationships between the examined and latent variables. The CFA should be applied if the researcher has some knowledge of the latent variable structure.

The study analysed how KM elements and the strategy are related to trust, and how their joint impact influences the factors that affect the effective functioning of the organisation.

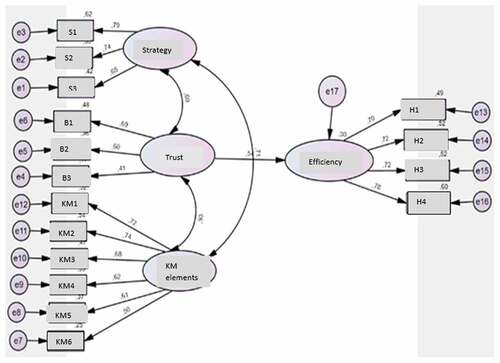

The model formed by factors and variables was created with the SPSS AMOS 27 version. Four external models were created (Measurement model), in which there are latent variables and indicators, and it is possible to explore the relationships between them. KM elements, Trust, Strategy, Efficiency and their indicators took place in the external models. The examined Measurement models are Reflective Measurement models because the arrows towards the indicators start from latent variables. In the internal model (Structure model), the relationships between KM elements, Trust, Strategy, and Efficiency, i.e. latent variables can be learnt about. In Figure , each arrow shows the effect of one variables on the other, and the back-and-forth arrows symbolise covariance, or correlation between the variables. Indicators received the lettering shown in Table . The error variables are marked with a circle in the figure, (these are the factors that have been ignored when examining the relationships of the model because not all factors can be examined), but they have an effect on variables. The model is shown in Figure .

Figure 2. The relationship between trust, strategy, KM elements and organisational efficiency.

The adequacy of the model can be checked by many criteria. The first study metrics confirm “absolute mode fitness”: the chi-square was significant ((500)508,452, df: 100, p: .00). This is not sufficient to reject the adequacy of the model, since, after a sample number above 200, the significance of the chi-square shows a value of 0 ore strongly, so further metrics need to be analysed. The RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) value: .066, which should typically be less than 0.08. The GIF index (Goodness of Fit Index), which is acceptable above 0.9, is .935 in this case, so it is appropriate. For Incremental Model Fit, four indices were examined: AGFI, CFI, NFI, TLI, the value of which above 0.9 can be considered good. In the model, the AGFI: .911, the CFI: .924, the NFI: .907, the TLI: .909, that is, the values of these indices were also appropriate. In the case of Parsimonious Fit, the chi-square/df- value is 5.085, which is minimally higher than the threshold value of 5, so, based on this, the model can be considered appropriate as well.

In the following, we examined the relationships between the individual variables. Regression values (Table ) show that trust has a strong positive significant impact on organisational efficiency (0.544). The effect of Trust, KM elements and Strategies on one another also shows a strong positive significant correlation value. The correlation: Trust—KM element (.930), Strategy—Trust (.597), KM element—Strategy (.715). The figure shows that, in the case of efficiency, the square of the multiple correlation coefficient is .296, that is, trust also influences the efficiency of the processes of organisational functioning.

Table 7. Regression values (p = 0.05)*

As a final step, correlations specific to each nation were examined. The results show that trust has a significant impact on organisational efficiency in each country (Table ). This impact is strongest in the case of the Chinese respondents, while the weakest among Hungarian organisations.

Table 8. Regression values by country (p = 0.05)

Based on the above analyses, it can be said that trust also strongly impacts organisational efficiency. Based on the results, the third hypothesis has been confirmed. Country analyses show that trust is in a strong relationship with KM elements in American organisations, whereas in Chinese firms, a stronger relationship was found between all three latent variables examined than in the case of American organisations. Among European cultures, Romanian organisations had the strongest impact among KM elements, trust, and strategy. Based on this, the authors also see Hypothesis 1 and 2 as proven.

5. Discussion

As the results of the mentioned research also support, trust influences more organisational operation factors. It interacts with the knowledge-focussed thinking that emerges in the strategy, which seeks to ensure its competitiveness by favouring knowledge management system building and building on intellectual capital. This interaction is reinforced by the fact that there is also a close relationship between trust and the knowledge management elements already implemented in the organisations, back and forth. Moreover, as a consequence of the thinking that appears in the strategy, the application of knowledge management elements is also a practice, and the interaction can be traced here as well. Research results confirmed the hypothesis that the further effects of trust promote the efficiency of organisational functioning. It strengthens the further formation of culture through the characteristics supporting success, and, through the development of emotional intelligence, it affects employee and managerial behaviour. It supports the more pronounced articulation of organisation’s mission through honest communication. It contributes to cost reduction and process optimisation, which have a decisive impact on the performance of an organisation as a whole, and, as a result, on its competitiveness. Previous studies have examined the 1–1 relationship of the elements of the model we set up, which provided motivation for conducting the present research (Zhang et al. (Citation2008) and Mohamed et al. (Citation2012) trust—commitment, cooperativeness; Paliszkiewicz (Citation2012) trust—performance; Cameron et al. (Citation2011), Heinze and Heinze (Citation2020) and Twaronite (Citation2016) culture—trust, productiveness, innovation; Hadas (Citation2020) culture—knowledge management; Fantazy and Tipu (Citation2019) culture—knowledge development). Most research has examined the organisational relationships and effects of trust and culture. Further research has also focussed on the relationships between competitiveness (Deif and Van Beek (Citation2019) (competitiveness—talent, learning) and strategy (Seppala, Citation2015; strategy—teamwork—success). All research revealed positive correlations, which the present research has confirmed by examining the joint impact of several factors.

The interesting thing about the present research is that, for all the studied nations, the relationship system of the model shows a significant correlation. This means that, regardless of how high or low values Hofstede’s characteristics show, trust, its impact, and its relationship with further factors that influence organisational operation are important to all cultures, and the soft elements are taken into account when evaluating competitiveness. Based on its cultural characteristics, Slovakia is at the forefront in terms of the Masculinity factor, which means encouraging competition, and, at the same time, striving for excellence. In the research, in the case of this nation, trust and efficiency does not show a remarkably strong correlation, which is presumably due to the high value of Power Distance. Masculinity’s relatively high value in the case of Hungary also reflects a focus on competition, whereas Individualism works against trust building and the preference of joint thinking that brings about success. This prevails in the lowest value of trust—efficiency relationship that can be demonstrated in the research. In the case of the third European country (Romania), the high values of Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance, and the low value of Masculinity influence the relationship between trust and efficient organisational functioning. It is clear from the characteristics of the Chinese culture that the collectivist approach and the multiplicity of small businesses strengthen the relationship between the parameters of trust and efficient functioning, which appeared in the present study as the strongest correlation. Among the characteristics of the American culture, Individualism has a sufficiently high value, Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance have low, and Masculinity is stronger than average, which, in terms of trust, shows a tendency to compete, but not too strong, but works against joint thinking and trust-based cooperation. Perhaps this is why it does not show an outstanding relationship in the area of the two examined factors (trust—efficiency). This difference between China and the USA can be a notable result for the analysis of the current competitive situation in international markets.

The research takes a new perspective on the background factors that ensure competitiveness and their impact on market success/efficiency. In the literature, the influence of trust has been studied primarily in the case of quantitative indicators of management. In the study, these results are complemented by additional influencing factors. As a new finding, the authors have shown that the prevalence of organisational trust positively influences soft elements of organisational effectiveness, and through this, competitiveness. There is a strong numerically demonstrable impact of trust on cost and fluctuation reduction, and on the optimal functioning of business processes. (All characteristics affect organisational performance). Trust also has a positive impact on multilateral communication, emotional intelligence, self-confidence and corporate mission, which are difficult to quantify but have an impact on organisational success. It is a novel approach that the study shows that soft elements need to be taken into account when judging the success of an organisation by looking at the case of five countries with different cultures. Among the organisations surveyed, less than 10% of European firms consider the existence of trust, while for Chinese firms this figure is close to 15%. (This fact is reflected in the overall level of national economic indicators.)

6. Conclusion

The aim of the research was not to compare GDP as a numerical performance, but to assess the influence of soft factors based on cultural characteristics behind competitiveness at the organisational level.

Based on the cultural characteristics of the nations examined in the research, among the soft elements of competitiveness, trust and knowledge management and their interaction were examined, along with their impact on the characteristics of effective functioning that contributes to organisational competitiveness.

Based on the results, it can be demonstrated how, by deriving the cultural characteristics of the organisation from the national culture, the functioning of knowledge management processes and strategic thinking contribute to the competitiveness of the organisation. Trust affects success directly, and also through the functioning of knowledge management elements. The additional characteristics that contribute to success vary from country to country (depending on cultural characteristics).

The results show that, regardless of the very different national characteristics, in all cultures, there is a significant relationship between trust and the characteristics of effective functioning. At the same time, it shows that the soft characteristics of competitiveness should be taken into account in the calculation of evaluations, indicators, and characteristics, even if there are difficulties in detecting and quantifying these factors.

6.1. Limitations of research

There were limitations to the research on several fronts. Collecting the study sample was a major challenge, especially in the case of America and China. The sample size needs to be increased for all countries. The willingness to respond was quite low. Additional nations (from Europe and the other two continents) should be included in the study to validate the results. It is conceivable that further interesting results could be obtained for organisations from countries with different cultures and levels of economic development. As competitiveness and organisational effectiveness can be judged through complex indicators, there was opportunity to examine only a few of them. In the analysis, several factors have been omitted due to the application of the method, which led to the marginalisation of valuable information. Although in the authors’ opinion they would not change the final results decisively, their influence could be interesting. The research goes on to investigate the role of trust in each industry, focusing on the impact of company size growth.

Availability of data

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by the Research Centre at Faculty of Business and Economics (No PE-GTK-GSKK A095000000-4) of University of Pannonia (Veszprém, Hungary).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrea Bencsik

Habil Andrea Bencsik CSc. is a professor of economic and management science at Janos Selye University in Slovakia and University of Pannonia in Hungary. Her research and teaching areas are knowledge- change- and human resources management. She is the author of a number of scientific publications and a member of some international scientific committees.

Timea Juhasz

Habil Timea Juhasz PhD is an SAP logistics consultant and senior researcher at the Budapest Business School in Budapest, Hungary. Her research interests include knowledge management, human resource management, family-friendly organisations.

References

- Abrams, L. C., Cross, R., Lesser, E., & Levin, D. Z. (2003). Nurturing interpersonal trust in knowledge-sharing networks. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 64–24.

- Alexa, D., Cismas, L. M., Rus, A. V., & Silaghi, M. I. P. (2019). Economic growth, competitiveness and convergence in the European regions. a spatial model estimation. Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research, 53, 107–124. https://doi.org/10.24818/18423264/53.1.19.07

- Alkhurshan, M., & Rjoub, H. (2020). The scope of an integrated analysis of trust switching barriers, customer satisfaction and loyalty. Journal of Competitiveness, 12(2), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2020.02.01

- Arrow, K. J., & Debreu, G. (1954). Existence of an equilibrium for a competitive economy. Econometrica, 22(3), 265–290. https://doi.org/10.2307/1907353

- Blendinger, G., & Michalski, G. (2018). Long-Term competitiveness based on value added measures as part of highly professionalized corporate governance management of German dax 30 corporations. Journal of Competitiveness, 10(2), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2018.02.01

- Bouncken, R. B., Kraus, S., & Roig-Tierno, N. (2021). Knowledge- and innovation-based business models for future growth: Digitalized business models and portfolio considerations. Review of Managerial Science, 15(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00366-z

- Brockman, P., Khurana, I. K., & Zhong, R. I. (2018). Societal trust and open innovation. Research Policy, 47(10), 2048–2065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.07.010

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Taylor & Francis eBooks, Routledge.

- Cameron, K., Mora, C., Leutscher, T., & Calarco, M. (2011). Effects of positive practices on organizational effectiveness’. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47(3), 266–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0021886310395514

- Carbonell, N., & Nassè, T. (2021). Entrepreneur leadership, adaptation to Africa, organisation efficiency, and strategic positioning: What dynamics could stimulate success? International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25, 1–10. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/entrepreneur-leadership-adaptation-to-africa-organisation-efficiency-and-strategic-positioning-what-dynamics-could-stimulate-succe-12830.html

- Carmeli, A., Brueller, D., & Dutton, J. E. (2009). Learning behaviours in the workplace: The role of high quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety’. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 26(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.932

- Castellani, P., Rossato, C., Giaretta, E., & Davide, R. (2021). Tacit knowledge sharing in knowledge-intensive firms: The perceptions of team members and team leaders. Review of Managerial Science, 15(1), 125–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00368-x

- Covey, S. M. R. (2022). Trust & Inspire. Simon & Schuster Ltd. New York.

- Cui, Y. (2021). The role of emotional intelligence in workplace transparency and open communication. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 101602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2021.101602

- Darroch, J. (2005). Knowledge management, innovation and firm performance. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(3), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270510602809

- Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they know. MA: Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge.

- Deif, A., & Van Beek, M. (2019). National culture insights on manufacturing competitiveness and talent management relationship. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(5), 862–875. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-08-2018-0240

- Dengjian, J. (2001). The dynamics of knowledge regimes: Technology, culture and national competitiveness in the USA and Japan. Continuum.

- Drucker, P. F. (2006). The effective executive: The definitive guide to getting the right things. HarperBusiness Essentials.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2F2666999

- Fantazy, K., & Tipu, S. A. A. (2019). Exploring the relationships of the culture of competitiveness and knowledge development to sustainable supply chain management and organizational performance. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(6), 936–963. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-06-2018-0129

- Florida, R. (2003). The rise of the creative class. Turtleback.

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: Social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press.

- Hadas, M. (2020). The culture of distrust. On the Hungarian national habitus’. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 45, 129–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/26873883

- Heinze, K. L., & Heinze, J. E. (2020). Individual innovation adoption and the role of organizational culture. Review of Managerial Science, 14(3), 561–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0300-5

- Hernaus, T., & Černe, M. (2022). Trait and/or situation for evasive knowledge hiding? Multiple versus mixed-motives perspective of trait competitiveness and prosocial motivation in low- and high-trust work relationships. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(6), 854–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2022.2077197

- Hofstede Insights.https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/china,the-usa/ (Accessed 26 July 2020)

- IMD Talent raking. 2018. https://www.imd.org/wcc/world-competitiveness-center-rankings/talent-rankings-2018/ (Accessed 13 November 2020)

- Ismail, D., Alam, S. S., Hamid, R., & bt, A. (2017). Trust, commitment, and competitive advantage in export performance of SMEs. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 19(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamaijb.22680

- Ivanova, A. S., Holionko, N. G., Tverdushka, T. B., Olejarz, T., & Yakymchuk, A. Y. (2019). The strategic management in terms of an enterprise’s technological development. Journal of Competitiveness, 11(4), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2019.04.03

- Jardon, C. M., & Martinez-Cobas, X. (2021). Trust and opportunism in the competitiveness of small-scale timber businesses based on innovation and marketing capabilities. Business Strategy and Development, 5(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.184

- Kashyap, V., & Rangnekar, S. (2016). Servant leadership, employer brand perception, trust in leaders and turnover intentions: A sequential mediation model. Review of Managerial Science, 10(3), 437–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-014-0152-6

- Keyton, J. 2015. Organizational Culture. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbieco023.pub2

- Kovács, G., & Kot, S. (2017). Facility layout redesign for efficiency improvement and cost reduction. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computational Mechanics, 16(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.17512/jamcm.2017.1.06

- Lee, J., Kim, S., Lee, J., & Moon, S. (2019). Enhancing employee creativity for a sustainable competitive advantage through perceived human resource management practices and trust in management. Sustainability, 11(8), 2305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082305

- Lee, Y. L. A., Malik, A., Rosenberger, I. I. I P. J., & Sharma, P. (2020). Demystifying the differences in the impact of training and incentives on employee performance: Mediating roles of trust and knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(8), 1987–2006. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-04-2020-0309

- Lewicki, R. J., Mcallister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 438–458. https://doi.org/10.2307/259288

- Luo, S., & Lin, H. C. (2022). How do TMT shared cognitions shape firm performance? The roles of collective efficacy, trust, and competitive aggressiveness. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39, 295–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-020-09710-4

- Massaro, M., Moro, A., Aschauer, E., & Fink, M. (2019). Trust, control and knowledge transfer in small business networks. Review of Managerial Science, 13(2), 267–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0247-y

- Mohamed, M. S., Kader, M. M. A., & Anisa, H. (2012). Relationship among organizational commitment, trust and job satisfaction: An empirical study in banking industry. Research Journal of Management Sciences, 2319, 1171. http://www.isca.in/IJMS/Archive/v1/i2/1.ISCA-RJMgtS-2012-025.pdf

- Mueller, J. (2012). The interactive relationship of corporate culture and knowledge management: A review. Review of Managerial Science, 6(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-010-0060-3

- Newman, B., & Conrad, K. W. 2000. A framework for characterizing knowledge management methods, practices, and technologies, 16-1 to 16-18, Citeseer, Paper presented at PAKM.

- Ng, K. Y. N. (2022). Effects of organizational culture, affective commitment and trust on knowledge-sharing tendency. Journal of Knowledge Management, ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-03-2022-0191.

- Nold, H. A. (2012). Linking knowledge processes with firm performance: Organizational culture. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 13(1), 16–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691931211196196

- Paliszkiewicz, J. (2012). Managers’ orientation on trust and organizational performance. Jindal Journal of Business Research, 1(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278682113476164

- Paliszkiewicz, J., & Koohang, A. (2013). Organizational trust as a foundation for knowledge sharing and its influence on organizational performance. Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management, 1, 116–127. http://www.iiakm.org/ojakm/articles/2013/volume1_2/OJAKM_Volume1_2pp116-127.pdf

- Piotrowska, M. (2019). Facets of competitiveness in improving the professional skills. Journal of Competitiveness, 11(2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2019.02.07

- Putnam, R. (1995). Tuning in, tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America. Political Science and Politics, 28(4), 664–683. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096500058856

- Rajkovic, B., Ðuric, I., Zaric, V., & Glauben, T. (2021). Gaining trust in the digital age: The potential of social media for increasing the competitiveness of small and medium enterprises. Sustainability, 13(4), 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041884

- Sankowska, A. (2013). Relationships between organisational trust, knowledge transfer, knowledge creation and firm’s innovativeness. The Learning Organization, 20(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696471311288546

- Seppala, E. 2015 Positive teams are more productive, Harvard Business Review Online – Organizational Culture, HBR Press. https://hbr.org/2015/03/positive-teams-are-more-productive (Accessed 22 August 2020)

- Shao, Q. Y. 2014. Research on relationship between trust and knowledge sharing of firm alliance of technological innovation, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Financial Risk and Corporate Finance Management, Vols. I and II. 418–424.

- Skytt, C. B., & Winther, L. (2011). Trust and local knowledge production: Inter-organisational collaborations in the Sønderborg region, Denmark, geografisk tidsskrift-danish. Journal of Geography, 111, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2011.10669520

- Smith, C. (2006). Adam smith’s political philosophy: The invisible hand and spontaneous order. Routledge.

- Techo, V. P. 2017. The Chinese Cultural Dimension, Paris: Horizons University https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.19863.78248

- Tseng, S. (2010). The correlation between organizational culture and knowledge conversion on corporate performance. Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(2), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271011032409

- Twaronite, K. 2016. A global survey on the ambiguous state of employee trust, Harvard Business Review Online – Developing Employees, HBR Press. https://hbr.org/2016/07/a-global-survey-on-the-ambiguous-state-of-employee-trust (Accessed 21 Jun 2020)

- Van Fan, Y., Varbanov, P. S., Klemeš, J. J., & Nemet, A. (2018). Process efficiency optimisation and integration for cleaner production. Journal of Cleaner Production, 174, 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.325

- Wang, F., She, J., Ohyama, Y., Jiang, W., Min, G., Wang, G., & Wu, M. (2020). Maximizing positive influence in competitive social networks: A trust-based solution. Information Sciences, 546, 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.09.002

- Yasir, M., Majid, A., & Yasir, M. (2017). Nexus of knowledge-management enablers, trust and knowledge-sharing in research universities. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 9(3), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-10-2016-0068

- Yu, P. L. (2019). Interfirm coopetition, trust, and opportunism: A mediated moderation model. Review of Managerial Science, 13(5), 1069–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0279-y

- Zhang, A. Y., Tsui, A. S., Song, L. J., Li, C., & Jia, L. (2008). How do I trust thee? The employee-organization relationship, supervisory support, and middle manager trust in the organization. Human Resource Management, 47(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20200