Abstract

This study deals with the primary areas and the present dynamics related to entrepreneurial capacity (EC); apart from this, it provides research directions in EC’s research field that would be of use in the future. With the aid of bibliometric analysis, we analysed Google Scholar, Scopus, and the ISI Web of Science databases and arrived at 193 studies that we use as samples; these studies enable us to recognise the research activity conducted on EC from 1979 to 2022. The most influential articles and authors have been identified based on their publications, citations, location, and importance within the network. Apart from this, we investigate current themes, discover barriers to development in literature, and provide ways for future research. Although research activity on EC occurs globally, there is a shortage of studies concerning developing countries’ context; countries experience a lack of collaboration, which is observed explicitly between the authors of developing and developed countries. This research focuses on broadly two themes: entrepreneurship education (EE) as an antecedent of EC, which, in turn, is an antecedent to entrepreneurial intention (EI), and EC as an antecedent factor of firm performance and economic growth. Interestingly, there is also a rising focus on Entrepreneurial Universities. We conclude by suggesting potential research directions.

1. Introduction

According to modern economic theory, entrepreneurship primarily drives growth (Sergi et al., Citation2019). Entrepreneurship has assumed massive importance in the face of global economic challenges (Chhabra, Dana, Malik et al., Citation2021; Dana, Citation2001). Despite several factors influencing economic development, entrepreneurship is seen to be playing a vital role. Hence, policymakers and researchers should be more focused on gaining insights into entrepreneurship antecedents (Ahlstrom et al., Citation2019). Significant research is being undertaken to study entrepreneurial behaviour (Dana & Dana, Citation2005; Karmarkar et al., Citation2014). Entrepreneurship capital, knowledge, and capacity significantly affect entrepreneurial performance (Chhabra et al., Citation2022; Sebikari, Citation2019).

Why do only certain people become entrepreneurs (Shane et al., Citation2000)? Adequate discussion revolves around what sets entrepreneurs apart from non-entrepreneurs, as well as the traits and qualities that a person should possess that enable them to cope with the tension, uncertainty, and difficulties that accompany entrepreneurship (Alvarez & Barney, Citation2005; Bullough et al., Citation2014; Chhabra & Karmarkar, Citation2016; Gartner, Citation1988; Mberi, Citation2019; Sarasvathy, Citation2004).

Similar to lawyers and doctors who are specialised in their fields, entrepreneurs also require a pool of abilities, and these significant abilities could be categorised into (1) managerial ability (the implementation of a business model once an obligation is made) and (2) personal ability (making the required pledge). The entrepreneurial process consists of EC (innovative evaluation and future-focused abilities related to opportunity evaluation, which results in the proposal of a business model), managerial ability (Azila-Gbettor & Harrison, Citation2013; L. Li et al., Citation2015), and psychological abilities (González-Serrano et al., Citation2017; Srivastava & Misra, Citation2017) and uses these as a tool to create a business model (Afzal et al., Citation2018; Cavallo et al., Citation2019; Pinho, Citation2017; Soria et al., Citation2016; Di Vaio et al., Citation2022).

This question is significant, as, in response to it, we can observe the ability to increase, enrich, or target the entrepreneurial pool; while doing this, we also enhance the community’s prosperity. Entrepreneurs’ ability to create something significant and not just innovative is what differentiates them from other resourceful individuals (Thompson, Citation2004). Different individuals possess different skills and competencies than others (Dana, Citation1987), and according to systematic investigation, “entrepreneurial capacity” appears both irregularly and occasionally in the contexts of management, entrepreneurship, and economics research (Ablo, Citation2015; Baron & Henry, Citation2010; Bygrave et al., Citation2003; Carlisle et al., Citation2013; Clarysse et al., Citation2011; Hindle, Citation2002, Citation2007; Hindle & Yencken, Citation2004; Kuratko et al., Citation2005; Lopez et al., Citation2019; Otani, Citation1996; Reynolds et al., Citation2005; De Soto, Citation1999; Thanasi-Boçe, Citation2020).

In 2007, in his study titled “Formalising the Concept of Entrepreneurial Capacity,” Kevin Hindle made a prodigious effort to formalise the concept of EC. The formalisation integrates the clear opportunity-based definition of entrepreneurship research offered by Shane and Venkataraman (Citation2000). The consensus in economics, management, entrepreneurship, and strategy literature is that innovation is a process for transforming the integral monetary value of innovative knowledge into realised economic value for identified stakeholders.

Our lacunae in the field of entrepreneurship need to be taken seriously because there is mounting evidence that the key to economic growth and productivity improvements lies in the entrepreneurial capacity of individuals and the economy (Prodi, Citation2002). Despite the significance of EC to economic development and progress, very limited studies have been conducted on the beginning and development of EC from an academic viewpoint (Hindle, Citation2007). Also, a systematic investigation has revealed that the term “entrepreneurial capacity” appears intermittently and unsystematically within the literature of economics, management, and entrepreneurship research but is not yet fully explored, developed, or defined as a unique or specialised term within any field (Hindle, Citation2007). With such varied contexts used in the EC research field, this paper attempts to embrace a substantial review of EC’s research field. No author other than Hindle (Citation2007) has yet presented a review of the field.

Historical reviews examine the progression of a discipline or area of study across time and may include ongoing comments evaluating the impact and weaknesses of various contributions (e.g., Chhabra, Dana, Malik et al., Citation2021; Cobo et al., Citation2011; Hassan et al., Citation2021). Thus, to provide access to this field, this study presents a bibliometric review of management literature on EC and a guide for management scholars—ranging from doctoral students to experts in other management areas. This paper seeks to add a historical perspective to the contemporary debate concerning the concept of EC. Through a detailed systematic review of the management literature on EC, we assess the emerging research domains, identify gaps in the past literature, and propose future research topics. Following Chreim et al. (Citation2018), our paper answers the following key questions: (1) What is the domain of EC research? (2) What are the present and past preliminary study streams in EC research? and (3) What are the most important future research questions regarding the concept of EC? Given the current focus on boosting entrepreneurship across global contexts, our findings should pique the interest of academics and policymakers alike. This is the first study to present the thematic landscape of the research field of EC.

The current condition of EC research is then examined using a bibliometric approach to determine the popular publications and the themes of interest. This allows for a thorough grasp of what writers are creating in terms of research (Chhabra et al., Citation2021; Dabić et al., Citation2020). It also portrays the drifts in the management literature regarding co-citations and geographic areas of interest in the research field of women entrepreneurship. The articles are then subjected to content analysis to discover current and emerging EC research issues. The following is a breakdown of the paper’s structure: we begin with a description of the study’s theoretical background, followed by a description of our technique. We then present a discussion of current developments. Finally, we perform a thematic assessment of EC literature and assess the paper’s limitations and future research directions.

2. Theoretical background

Hindle (Citation2007) integrated Shane and Shane and Venkataraman’s (Citation2000) prominent definition of entrepreneurship research based on the literature’s dominant consensus. According to this consensus, entrepreneurship research is a method by which innovative knowledge’s innate economic significance. Synthesising the two schools of thought, Hindle (Citation2007) defined EC as “The ability of an individual or grouped human actors to evaluate the economic potential latent in a selected item of new knowledge and to design ways to transform that potential into realisable economic value for intended stakeholders.” According to Hindle (Citation2007), a ramification of novel literature about economics and management shows a broad concurrence with the definition’s viewpoint. Thus, it can be postulated that literature regarding economics and management provides adequate support for summarising EC’s significant characteristics in the following manner. The creation of wealth or value results from synthesising the two inputs at a comprehensive level. An opportunity should primarily exist and be followed to be revealed. Next, the ability to transform an innovative prospect into one with economic significance should come into being. Economic significance is created when a transformational ability is applied to the underlying ability or significance attached to the revealed opportunity.

Otani (Citation1996) stipulated that EC determines the firm’s long-run size but is a black box, or a gift, an exogenous parameter beyond economic explanation or evaluation. EC’s concept is formulated as a kind of human capital based, and Lucas (Citation1978) considers EC an innate exogenous talent that is heterogeneous among individuals. Otani (Citation1996) assumes that EC is also exogenous but an acquired ability and assumes that individuals are homogenous and that only capital goods are heterogeneous. There is wide heterogeneity in the literature about the definition of EC based on its underlying constructs. Table presents EC’s constructs, as depicted by the top 20 authors (based on citations).

Table 1. EC constructs, as represented by the top twenty authors

The views expressed in terms of EC constructs vary from resource mobilisation (Norton, Citation1988; Otani, Citation1996; Hindle & Yencken, Citation2004; effective knowledge management (Ablo, Citation2015); innovative capacity (Newbert, Citation2008); locus of control (Newbert, Citation2008); ability to identify, evaluate and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities (Hindle, Citation2007; Nicolaou et al., Citation2009; Hindle, Citation2010; Baron & Henry, Citation2010; Clarysse et al., Citation2011); capacity of learning and integration (Fladmoe-Lindquist, Citation1996; Gibb, Citation1999), etc. Thus, the field is characterised by heterogeneous contexts. Therefore, through a systematic literature review, the study aims to synthesise and present the conceptual map of the research field of EC to identify the contemporary themes in the field.

3. Data collection and methods

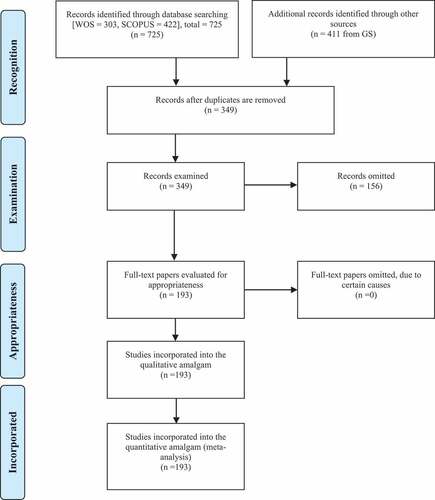

A comprehensive strategy for carrying out a topic search was employed using the Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases. The principal components spanned a broad array of high-quality articles and high-impact journals that experts had earlier studied in the field (Skute, Citation2019). While searching, the terms “Entrepreneurship Capacity,” “Entrepreneurial Capacity,” and “Entrepreneur Capacity” were utilised in the topic search area; no restrictions were laid on the language used in the documents or the publication year. The terms that are used in the topic area are examined in the abstracts, titles, and keywords (given by the authors) as well as in the Key Words Plus® (which includes index terms that spontaneously originate from the headings of articles that are referred to in the Web of Science). Boolean operators (AND/OR) were employed to enhance the search for associated documents. Due to this, 725 articles were initially derived from an amalgam of the keywords provided earlier. These articles that appeared initially were individually analysed and then filtered. First, we checked whether at least one of these search keywords was contained among the keywords, title, and abstract of the article in question. The abstracts of the articles thus selected were sought and analysed to confirm that the EC is defined in the article, and a lot of articles were found to have the EC as just in a contextual term or a part of the statement of findings without contributing to the concept of the EC. Such articles were, thus, eliminated. Also, the cited papers were analysed to decide whether it would be possible to select them. If so, then the procedure was followed similarly till no more articles were located within the reference list of a particular article. After applying this procedure and removing the duplicate articles, the search resulted in 193 articles. The Prisma Flow Diagram depicting the same is presented in Figure .

A comprehensive list comprising several articles was derived from SCOPUS, Google Scholar, and the Web of Science in Excel format; this list was then processed to generate a file in the required structure and format for the network analysis conducted in VOS viewer. VOS viewer is an open-source tool utilised for creating and envisaging bibliometric networks. The following tasks were performed with the tool:

Evaluation of the evolution over time of the number of articles published and included in the list

Evaluation of the evolution of the citations generated by various articles

Evaluation of the articles published by various authors

Examination of the articles published by several countries

Examination of the articles published by various organisations

Examination of the articles published in each respective journal

Examination of the most popular keywords

Co-occurrence Network Based on Title and Abstract Fields to identify clusters (thematic fields)

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Composition of research publications

The composition of research publications is presented in Table . English publications comprise almost the entire sample (88.61%); non-English publications comprise 11.39%, and among this, Spanish articles (6.33%) constitute the maximum. These findings are consistent with the earlier findings from previous studies, and English is considered the language used the most often in academic publications (Escamilla-Fajardo et al., Citation2020). Most of these records were articles and conference papers published in journals or as part of conference proceedings.

Table 2. Composition of research publications

4.2. Year of publications: evolution of published studies

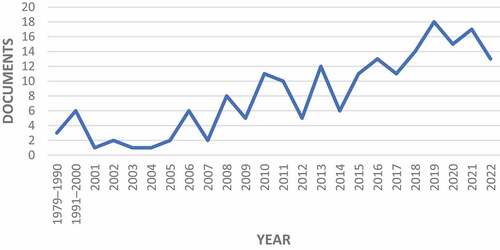

Table indicates the publications related to the EC from 1979 to 2022. There has been an increase in publications after the year 2009. There seems to be a rising interest in the research field of EC after 2007 when Kevin Hindle formalised the EC concept in his article titled “Formalising the Concept of Entrepreneurial Capacity.” In this article, a definition of “entrepreneurial capacity” was developed; Hindle later formalised the EC concept in two models to explain value creation during innovation. The impactful definition of “entrepreneurship research” provided by Shane and Venkataraman (Citation2000) was also integrated. Hindle’s article can be considered a benchmark article in EC, as it was the first effort to synthesise the literature on EC and give it a formal definition. A graphical presentation of the list of publications year-wise is presented in Figure .

Figure 2. Documents by year.

Table 3. Year of publications

4.3. General publication profiling of the EC research field

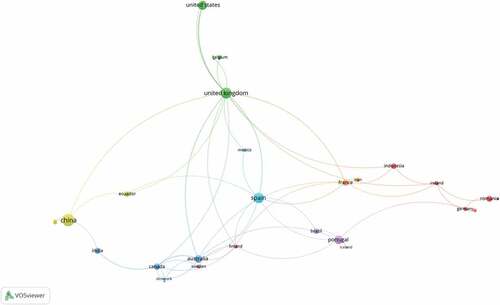

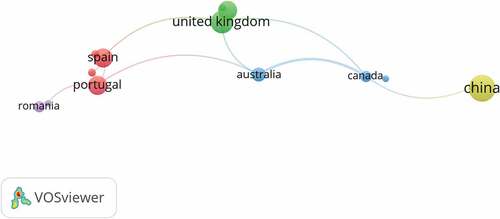

While considering the 193 articles that were assessed in this study, a total of 441 authors in 107 countries were evaluated. The highest number of publications are from China, an emerging economy, and the others on the list are the United Kingdom, Spain, United States, Portugal, Australia, and Canada, all of which are highly developed nations (also presented in Figure ). Thus, there are more publications from developed nations in the EC field. The literature largely neglects the role of learning in facilitating resource- and knowledge-scarce local entrepreneurs’ capability development in emerging economies (Khan et al., Citation2019).

Figure 3. Network visualisation map of the citation by countries.

Our study found that the journals Education and Training, Communications in Computer and Information Science, and Environmental Engineering and Management Journal were the leading source titles that are publishing research focused on the topics related to the field of EC. The most productive authors in several publications revealed that the publications varied around a large group of scholars’ research and were not concentrated on any leading universities. Kevin Hindle from Swinburne University, Australia, is the most prolific author in EC research. The details of the data supporting general publication profiling of the EC research field are presented in Table .

Table 4. General publication profiling of the research field of EC

4.4. Keywords analysis

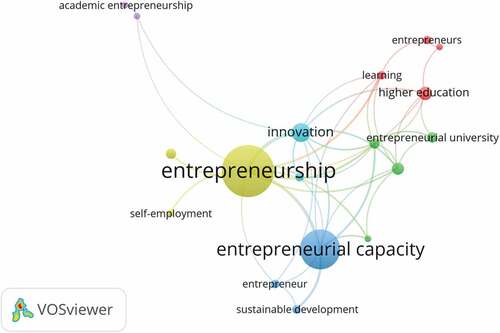

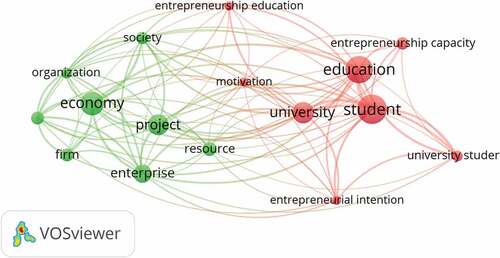

Figure depicts the keywords and the co-occurrence or co-word evaluation; this figure also indicates several well-known themes found in EC literature. We have discovered that the themes of innovation, higher education, entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial university, gender, and technology transfer dominate the discourse in this field. This signifies that innovation and EC, the two essential pillars of economic growth, are dealt with parallelly in several research lines. EC has been increasingly studied about the EC of students in higher education and assesses entrepreneurship education’s effect on students’ EC.

Figure 4. Network visualisation map of the author keywords.

EC is the capacity to evaluate the economic potential in novel innovations and to create means for entirely transforming these into aspects that have actual economic worth (Batte & Da Silva, Citation2013; Cunningham & Moroz, Citation2008; Y. H. Li et al., Citation2008; Lee & Peterson, Citation2000; Lee II, Citation2013; Lumpkin & Dess, Citation1996; Newbert, Citation2008). The significance of entrepreneurship education concerning encouraging entrepreneurial activity and beliefs is extensively recognised. According to Kuratko et al. (Citation2005), an enhanced number of courses and programs on entrepreneurship in training or educational institutions, and an increased number of trainers and mentors dealing with entrepreneurship, is evident proof of this fact. It has, thus, been proved that entrepreneurship or at least a few aspects of it, can be taught. Hindle (Citation2007) and Kuratko et al. (Citation2005) agree that from a fundamental and logical viewpoint, there is no a priori cause behind entrepreneurship not being imparted. They propose three approaches toward entrepreneurship education: Teach about it. Teach it in several ways and in different places. Just teach it. Studies that have been lately conducted in the field of entrepreneurship, for instance, Maritz and Brown (Citation2013), Raposo and Do Paço (Citation2011), Zeng and Honig (Citation2016), and Maritz (Citation2017), also have as their foundation the concept that entrepreneurship is something that can be probably taught. This literature review yielded many studies measuring entrepreneurship education’s effect on improving students’ EC as potential entrepreneurs. The concept that universities should or could be entrepreneurial entities could be traced back to the early 1980s. This concept discusses how institutions involved in imparting higher education could play a role in economic development and social change and, as a result, how they started being featured more prominently within literature (Clark, Citation1998; Etzkowitz, Citation1983; Gibb & Hannon, Citation2006; Guerrero & Urbano, Citation2019; Klofsten & Jones-Evans, Citation2000; Perkmann et al., Citation2013). Various universities have attracted a great deal of attention from researchers who are interested in examining their entrepreneurial capacity, and this has been possible due to the following reasons: Universities act as catalysts by enabling the transfer of knowledge, attracting highly educated individuals, sustaining the competitive spirit observed in established institutions and firms, and contributing toward the establishment of novel ventures (Peterka & Koprivnjak, Citation2017; Pugh et al., Citation2018). Table presents the top keywords that several authors utilise.

Table 5. Top keywords

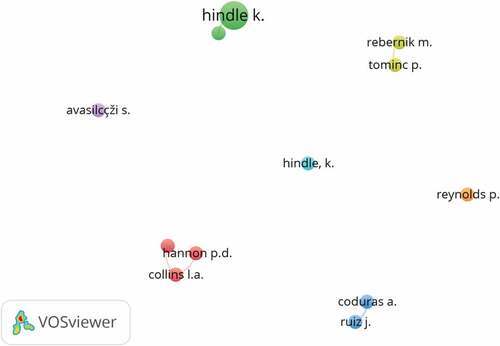

4.5. Authorship

Table presents the number of authors per document. Articles with three authors are the highest in number (27.98 %), followed by two (26.42%), one (21.24%), and four (17.62%) authors. Table presents the most productive authors in the EC field, among whom Kevin Hindle is the most illustrious author in this field. The co-authorship feature in research endeavours, a type of social networking, is of exceeding interest to the academic public (Martins et al., Citation2012). Research partnerships have significant appeal because they facilitate sharing of knowledge, thoughts, abilities, and perceptions. They can also enhance research productivity and quality (Koufteros et al., Citation2020).

Table 6. List of the author(s) for every document

Cooperation among various scholars is required to develop any field; thus, more cross-country cooperation is necessary (Baker et al., Citation2020). Figure presents the degree of collaboration among scholars in several nations and depicts the countries with the most influential publishing records within this network of cooperation among scholars. As depicted in Figure , the influential countries in collaborative efforts are China, the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, Australia, Canada, and Romania. Cultural relationships, geopolitical place, and language are the factors that determine and shape the preferences for co-authorship (Schubert & Glänzel, Citation2006). Spanish, Romanian, and Portuguese are among the significant Romance languages; the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada are all a part of CANZUK, these countries’ theoretical, political, and economic union. Thus, it is evident that language and geopolitical affinity play a crucial role in determining cross-country co-authorship.

Figure 5. Network visualisation map of the co-authorship.

The cooperation between scholars is the best formal method for intellectual association about scientific research (Cisneros et al., Citation2018). International cooperation networks enable developing nations to be involved in the knowledge-creation procedure, usually led by the developed nations (Palacios-Callender & Roberts, Citation2018). The amalgam of any two perspectives results in the development and maturity of thoughts. This also enhances the quality of a multi-author published article, as there are fewer mistakes and the contributions are from various disciplines (Tahamtan et al., Citation2016). This section discusses the cooperation between scholars and identifies the most significant authors in this network of cooperation between scholars. As depicted in Figure , the most prominent author countries in the collaborative effort are China, the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, Australia, Canada, and Romania. The most influential authors in terms of collaborative effort are Kevin Hindle and Peter W. Moroz from Australia; Robert Anderson from Canada; Lorna A. Collins, Alison J. Smith, Paul D. Hannon, Alice Coduras, and Jesús Ruiz from the United Kingdom; and Polona Tominc and Miroslav Rebernik from Slovenia. These authors comprise a homogeneous network within which cooperative attempts are restricted mainly to the authors within their respective nations. Such a network indicates that research concentrates around a few authors, and most of the nodes seem to create a network of two or three authors, highlighting the need for a higher cross-country authorship in the research field of EC.

Figure 6. Network visualisation map of the co-authorship.

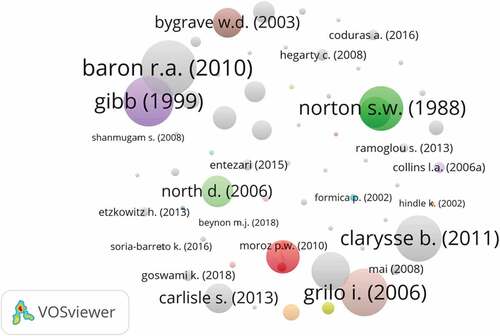

4.6. Citation analysis

Table presents the citation metrics of the 193 records from 1979 to 2022. Over 43 years, the total number of citations is 2458, resulting in 56.16 citations per year. Citations are intended to indicate that a publication has utilised the contents of several other publications (in the form of others’ ideas, research results, etc.); thus, the number of citations utilised in research assessment serves as a determiner of the influence of the research (Bornmann et al., Citation2008). “The impact of a piece of research is the degree to which it has been useful to other researchers” (Shadbolt et al., Citation2006, p. 202; see also, Bornmann & Daniel, Citation2007). The citation count of 12.76 per paper is good, as, with ten or more citations, academic research comes in the top 24% of the most cited works worldwide (Beaulieu, Citation2015).

Table 7. Citations metrics

While considering the number of their citations, the most significant authors are depicted in Table and Figure . The most frequently cited authors are Robert A. Baron and Rebecca A. Henry, famous for their article “How entrepreneurs acquire the capacity to excel: Insights from research on expert performance” (Baron & Henry, Citation2010). This article suggested that to the point that entrepreneurs obtain improved cognitive resources via a current or previous deliberate practice, their ability to carry out tasks associated with innovative venture success (e.g., precise recognition and assessment of business opportunities) is enhanced. Thus, the performance of their novel ventures is also augmented. They also described the particular manner by which entrepreneurs could probably benefit from improved cognitive resources. The authors depicted in Table and Figure were the most relevant in the search carried out because they have many citations (Demil & Lecocq, Citation2010). However, Peters et al. (Citation2015) stated that most of the current literature’s information is not cited rigorously.

Figure 7. Most influential authors.

Table 8. Highly cited articles: most influential authors

4.7. Textual exploration

4.7.1. Co-occurrence network based on title fields

Figure presents the co-occurrence network based on the title field; it is represented in this figure that the EC is studied in relevance to the economy and economic growth because entrepreneurs are the pillars of economic growth (Korez-Vide & Tominc, Citation2016). The government and the well-structured private sector should aim to enhance their funding for vocational or entrepreneurial training programs as a fragment of the tertiary educational structure to augment the EC (Thaddeus, Citation2012) and the consequential economic development (Votchel et al., Citation2019).

4.7.2. Co-occurrence Network Based on Title and Abstract Fields

Keywords are identified, examined, and presented in an orderly manner with the VOS viewer, an advanced software. After this exploration, two diverse clusters were distinguished by colours (green and red). Figure depicts the graphical portrayal of the co-occurrence of co-words or keywords. This figure explains the structure of the earlier literature’s concepts or knowledge (Cheng et al., Citation2020). The exploration of the terms is indicated by circles that are of various colours and sizes. The circle’s size indicates the incidence of a particular term’s appearance; the larger the circle’s size, the larger the incidences within the abstracts and titles of the publications analysed (Van Nunen et al., Citation2018). The colours of the circles parallel the diverse clusters observed in the search. The distance observed between the circles, that is, the keywords give essential details about their relationship; the smaller the distance from one circle to another is, the more intense the relationship. This association relies on the number of incidences in which the terms appear together within the abstracts and titles of publications (Roy et al., Citation2014). The condition for inclusion was an event incidence of ≥ 9 times. Eventually, 16 terms overall were utilised in this study. The VOS viewer discovered two diverse clusters (Figure ) depending on the thematic area and distinguished them by two colours; red and green, which are as follows:

Figure 9. VOS Viewer Visualization of a Term Co-occurrence Network Based on Title and Abstract Fields (Binary Counting).

4.7.2.1. Red cluster—“entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial capacity”

The important keywords in the cluster are “entrepreneurial ability”, “education”, “student”, and “university”, and the other four keywords are “entrepreneurship education”, “motivation”, “university student”, and “entrepreneurial intention”. Thus, the cluster comprises eight keywords associated with the role that entrepreneurship education plays in influencing the entrepreneurial capacity related to university students, which, in turn, influences their entrepreneurial intention (Turulja et al., Citation2020).

Usually, this cluster accumulates papers associated with the role that education and entrepreneurial education play as antecedent factors in influencing the entrepreneurial capacity of potential entrepreneurs. Governmental authorities and experts adopt entrepreneurship as an appropriate mechanism to face the impacts of the economic crisis . Entrepreneurial education can enhance both the quality and the number of entrepreneurs in the future (Kyrgidou et al., Citation2013). As a vital producer of knowledge in the region, the university plays a central role in the regional entrepreneurial economic systems and is the key actor in economic change (Kochetkov et al., Citation2017).

The latest universal economic decline has caused an increased youth unemployment rate, which includes university graduates, and compels them to contemplate substitute work opportunities, for instance, commencing a novel business (Roffe, Citation2010; Vaquero-García et al., Citation2017). Kothari et al. (Citation2007) posit that universities should equip graduates with abilities associated with industries that are always appropriate for employment. Similarly, Rae et al. (Citation2012) recognised the necessity for university students to enhance their experience, entrepreneurial attitudes, creative thinking, trust, communication, and public abilities as an aspect of their syllabus. Recently, entrepreneurial education has been the subject of several debates and has been transformed into an opportunity that addresses poverty and unemployment (Acs, Citation2006). Oosterbeek et al. (Citation2010) stated that entrepreneurial ability is derived from an attitude that usually results in an individual taking risks to manage uncertainty; it is identified with various viewpoints and abilities, for instance, ingenuity, courage, persistence, leadership, and determination. Entrepreneurs strive to provide an innovative good or facility to the community during times of disorder, turmoil, imbalance, and incoherence (Yazdanifar & Soleimani, Citation2015). De Tienne and Chandler (Citation2004) posit that students who benefit from entrepreneurship training are probably more effective at recognising opportunities, portraying a higher EC state than those who did not obtain entrepreneurship training.

Portraying a complete view of all studies would be beyond this paper’s scope; however, the subsequent paragraphs are an effort to present the highlights of a few notable studies under this cluster. North and Smallbone (Citation2006) studied the EC of micro and small rural entrepreneurs and concluded that those who had received a higher level of education displayed increased states of ICT utilisation and innovation; hence, they possessed a higher ability to identify and exploit opportunities (EC). In his article, Guojin, Citation2011, September) elaborated on teaching “creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship” courses to engineering students at Hangzhou Dianzi University, China. He summarised that these courses developed the students’ originality and entrepreneurial ability extensively. The students excelled in their innovativeness and practical ability, which won them the acclaim of several employing units. Gunes (Citation2012) discussed how students specialising in design could enhance their entrepreneurial ability with the aid of courses on design specialisation; with this in mind, Gunes (Citation2012) suggested an enterprising and intense skilful syllabus. People possessing the spirit of entrepreneurship are disposed to having exclusive needs; such individuals possess varied knowledge and skill sets compared with other people or conservative entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship education probably aids in fulfilling the exclusive necessities of entrepreneurs. This education comprises any educational procedure or program focused on enhancing entrepreneurial skills (abilities and perspectives).

A research was conducted at Universidade Europeia, Portugal (Sousa et al., Citation2018) on digital learning approaches to improve the higher education students’ entrepreneurial ability; several methodologies were proposed to promote the improvement of prospective entrepreneurs’ information and abilities. In her study, Thanasi-Boçe (Citation2020) discovered the role of a marketing simulation activity as a pedagogical medium for improving entrepreneurial ability and postgraduate scholars’ tendency to become entrepreneurs. According to her, in a simulation background, entrepreneurial education can enhance students’ entrepreneurial abilities and motivate them to carry out entrepreneurial events. The simulation experience enabled students to face challenges, overcome limitations, strengthen their analytical skills, and improve their business acumen.

A research was conducted (Verzat et al., Citation2016) on the effect of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) on effectual entrepreneurship (Saras, Citation2005): It was found that (1) the role of motivation in self-directed learning is essential but is moderated by a sufficient allocation of time; (2) the MOOC enables a progression of the entrepreneurial self-efficacy regardless of the initial level; and (3) self-directed learning, which is a means rather than a goal of learning via a MOOC, does not progress as much as self-efficacy. González-Serrano et al. (Citation2017) conducted a study at the University of Valencia, Spain, to comprehend the entrepreneurial courses (internal features) and the environment (external features) that have an impact on the entrepreneurial motives of the students who are involved in sports science and physical activity. She concluded that the perceived EC of the students had a positive effect on their entrepreneurial intentions. Hence, university education as an aspect of policies that stimulate entrepreneurship will enhance the numerical figures of entrepreneurs in the sports field. A similar study was conducted by Turulja et al. (Citation2020) in Bosnia and Herzegovina and concluded that education’s role in encouraging and inspiring approaches and motives toward entrepreneurship is incontestable, specifically when we are dealing with entrepreneurial education. The logic for the impact is that by acquiring entrepreneurial abilities and knowledge, people develop self-confidence during their entrepreneurial motives, and the fear of failure is reduced. With education, a person acquires the entrepreneurial ability that enhances their entrepreneurial motives.

The pool of data also includes studies that deal with academic entrepreneurial capacity. Clarysse et al. (Citation2011) utilised a large-scale academicians board from many universities in the United Kingdom between 2001 and 2009. They investigated how an academician’s extent of entrepreneurial ability in terms of their opportunity recognition ability and their previous entrepreneurial knowledge give rise to the probability of them being engaged in starting an innovative venture. They concluded by proving that individual-level features and experience constitute the most significant determiners of academic entrepreneurship. In a similar context, in a study conducted on academic researchers in the United Kingdom in Physical Sciences and Engineering, D’Este et al. (Citation2010) posited that various factors mould the recognition and utilisation of entrepreneurial chances. Commercial opportunities are recognised by previous entrepreneurial know-how and the distinctive quality of academic work.

In contrast, entrepreneurial opportunities are driven by an earlier collaboration with industrial partners, previous entrepreneurial know-how, and cognitive incorporation. Kochetkov et al. (Citation2017) compared different techniques of entrepreneurial capacity measurement in terms of university rankings. They concluded that the vast majority of the world rankings exclusively measure academic performance (publications, citations, internalisation). However, innovative rankings lack available statistical indicators. Thus, they suggested reforms in educational policy decisions because the existing system of indicative planning leads to the one-sided development of universities focusing solely on the number of publications. The beginning of the Fourth Industrial Revolution has resulted in knowledge playing a vital role in humanity’s socio-economic development. The university plays a central role in the knowledge-based regional economic growth model, being the leading producer of knowledge. Thus, the model of knowledge generation can be summarised in terms of the production process; hence, the term “entrepreneurial capacity” of entrepreneurial universities is used.

A plethora of studies in the sample is related to studying the effects of entrepreneurship education and building the EC of students/potential entrepreneurs. Indeed, it is encouraging news as an increased number of studies in this arena depict the higher significance placed on entrepreneurship education, which is the need of the hour. However, most of these studies have been conducted concerning developed countries, and there is an identifiable dearth of studies concerning developing, emerging, and transition economies. A growing market orientation and an intensifying economic basis categorise developing economies. The success of several economies takes place so that these economies emerge as significant economic powers globally. Entrepreneurship plays a significant role in this economic growth (Bruton et al., Citation2008). Thus, higher emphasis should be placed on conducting EC research concerning these economies. Then, suggestions can be made concerning how EC can be fostered from the ground level by adequately channelising the EE through colleges and universities.

The university moves toward intellectual capital, starting with growth and research and progressing toward technology transfer and expansion. The university does not conduct R&D just like that for business purposes; instead, it establishes an innovative industry. The university is the pivot around which innovative hi-tech businesses grow. This phenomenon is titled “entrepreneurial university,” which plays the primary role in the start-up or entrepreneurial economy. The creation of entrepreneurial universities only emphasises the formation of groups of entrepreneurs.

4.7.2.2. Green cluster—“entrepreneurial capacity and growth”

The important keywords are “economy”, “project”, “enterprise”, and “firm”, and the other four keywords are “organisation”, “society”, “resource”, and “economy”. Thus, the green cluster comprises eight keywords associated with entrepreneurial ability’s role in developing an enterprise and economy.

This cluster aggregates the papers related to EC and the growth of an enterprise and an economy. Entrepreneurship is an essential mechanism by which economic development can be achieved (Acs et al., Citation2012, Citation2008; Audretsch & Keilbach, Citation2004a, b, Citation2008). Earlier authors provided proof of entrepreneurship’s significance concerning economic growth; they differentiated between business ownership, self-employment, and innovative business establishment, among others (Blanchflower, Citation2000; Carree & Thurik, Citation2008; Carree et al., Citation2002). Such approaches have always utilised neo-classical economic development elements and the Schumpeterian theory to connect entrepreneurship with economic development. Entrepreneurship capital is a significant factor in attaining economic development (Urbano & Aparicio, Citation2016), and the EC is an integral part of entrepreneurship capital. Qian et al. (Citation2013) and Colino et al. (Citation2014) used the neoclassical production function while considering human capital and entrepreneurial ability as individuals’ unique features. Thus, entrepreneurship is evaluated in an economic development model to find its effect and complementarity (Urbano & Aparicio, Citation2016), and this is the case with EC.

Hindle (Citation2002) provided a theoretical demonstration that the specific domain of innovation policy should be entrepreneurial capacity, which, during any innovative procedure, constitutes the primary mechanism responsible for converting innovative knowledge into economic worth, thus differentiating entrepreneurial capacity and entrepreneurial performance. Jiménez et al. (Citation2014) examined the association between entrepreneurial ability and the performance of an organisation. More precisely, they examined the impacts of radical invention and learning coordination business performance and indicated that fundamental product invention and organisations’ orientation toward learning positively impacts a firm’s performance. Tehseen and Ramayah (Citation2015) conducted a theoretical examination of entrepreneurial abilities’ impacts on organisations’ success within Malaysian SMEs’ framework. They also embraced the resource-based view of competencies (RBV) and posited that entrepreneurial skills are prized and impalpable resources that result in any business’s success. It is suggested that the domain of entrepreneurial competency affects the success of MSMEs and includes the following: strategic skill (which is associated with the creation, assessment, and execution of the schemes for the organisation); conceptual skill (which involves various conceptual skills that entrepreneurs indicate in their behaviors, e.g., risk taking, creativity, witnessing, and comprehending intricate information, and decision competency); opportunity skill (which is the capacity to identify the chances in the market via several means); learning skill (which is the capacity of the entrepreneurs to acquire knowledge by using several methods and resources, while simultaneously keeping abreast in their specific field, learning in a proactive manner, and finally applying their acquired knowledge and abilities to practical situations); personal skill (which indicates the capability to motivate oneself to perform at the best level while retaining a high energy level, capacity to react to criticism, retaining a positive frame of mind, recognising powers and flaws as well as matching them with the fears and chances, and identifying their own weaknesses and working toward improving them); ethical skill (which indicates the role played by truthfulness and transparency in business dealings by accepting mistakes and saying the truth); and familism (societal standards that help one cope with the relationships both within the family and among the other family members). S. S. Kim and You (Citation2019) investigated entrepreneurs’ competence and success factors that influence young entrepreneurs’ business performance. They summarised one of their findings: that technological commercialisation ability and technological innovation capacity, which are sub-factors of technological and entrepreneurial capacity, influence business performance and creation. The entrepreneur is invested in establishing a new market by conducting test ballooning (test marketing) to learn about the market features and show users’ preferences. The economic behaviour of an SME is impacted positively by the EC of the entrepreneur.

S. Kim and Choi (Citation2016) studied the effect of organisational entrepreneurship-level competence, the attitude of design company members, and the CEO’s support; they illustrated that these three factors significantly affect an organisation’s culture and structure. Thus, it seems likely that the EC affects a firm’s performance and its culture. The conclusions of all these studies also assert that EC is different from entrepreneurial performance and that EC cannot be measured by business success but is the ability to identify, evaluate and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities (Hindle, Citation2007).

Velichová (Citation2013) described the economy’s entrepreneurial capacity as determined by people’s capacity and impetus to commence business activity and positive societal views of the business. In their article, Faghih et al. (Citation2019) established and calculated the EC index based on the GEM data from 2002 to 2009; they recommended that these could be used to study entrepreneurship’s globalisation process. The attitudes and intentions of entrepreneurship were the predominant topics in this study; the maximum value of potential entrepreneurial perception was named the “entrepreneurship capacity” index. The median of potential entrepreneurial perception was considered the “entrepreneurial attitude” index. Thus, the EC index has been created and used to improve countries’ economic categorisation, and a ranking list of countries was created based on this index.

Thus, articles in the green cluster collate on the EC as an antecedent factor of firm performance and economic growth and the EC of an economy or an organisation. The two themes just cited describe the categories of studies conducted in the context of EC.

5. Conclusion

This study’s outcomes partially help us comprehend the present state and the term EC’s growth in the entrepreneurship literature. This vital information gives the reader an overview of the authors, various publications, journals, institutions, and countries with the figures on publications and the figures of citations as per an evaluation of 193 articles altogether. One of the most significant contributions is recognising the thematic research areas where the EC is developed. On the one hand, this enables identifying the areas of interest and themes for academicians and researchers; on the other hand, this points out the future strands of research from the perspective of the growth of EC’s research field. The two clusters identified are; the importance of EE as a significant antecedent in promoting EC and the rising concept of the EC of entrepreneurial universities (red cluster); the EC as an antecedent factor of the firm and economic growth, and the concept of the EC as an index in measuring the growth of an economy (green cluster).

Researchers have used different themes for defining and measuring EC, such as the opportunity (create, identify, and exploit opportunities), innovation, skills and experience, risk-taking capacity, absorptive capacity, etc. These definitions of EC found in the literature are presented in a relational context. Except for one study, Hindle (Citation2007), no study has been identified to formalise EC and explore the concept in detail. Hindle (Citation2007) defined entrepreneurial ability as a concept; this was achieved through integrating the relationships between innovation, the entrepreneurial process, and the entrepreneurial context. Hindle’s motivation for developing the EC concept stemmed from a yearning to offer the entrepreneurship research institution a spring equivalent to the institution’s explanation of entrepreneurs’ tasks, i.e., creating new ventures. There have been no subsequent efforts toward its theoretical and empirical development, and the concept is underexplored. Most popularly, the EC concept has been dealt with in measuring the impact of the EE on the EC, which further impacts the EI and the EC as the antecedent factor of firm performance and economic growth. The research on EC is directionless and is becoming obsolete, thus inviting scholarly attention to the development of the concept. There is a need for a uniform scale to be developed for measuring EC.

6. Theoretical and practical implications of the study

This paper makes significant contributions to the literature. Heterogenous contexts characterise the EC field. Our findings concur with Hindle (Citation2007) that the term “entrepreneurial capacity” appears intermittently and unsystematically within the literature of economics, management, and entrepreneurship research but is not yet fully explored, developed, or defined as a unique or specialised term within any field. Thus, with such varied contexts used in the EC research field, this paper attempts to embrace a substantial review of EC’s research field. This study has identified the conceptual map of the research field. It presents “Entrepreneurial Education and Entrepreneurial Capacity” and “Entrepreneurial Capacity and Growth” as the main themes identified in the thematic landscape of the EC literature. This is the first study to give a detailed overview of the literature on EC.

This paper also has significant implications for managers and policymakers. The findings of this study reveal that education stimulates encouraging and inspiring motives towards entrepreneurship, especially when we are dealing with entrepreneurship education, and entrepreneurship education stimulates the perceived EC of the students, which in turn enhances their entrepreneurial intention (Guojin, Citation2011; Kochetkov et al., Citation2017; Kothari et al., Citation2007; Kyrgidou et al., Citation2013; North & Smallbone, Citation2006; Sousa et al., Citation2018; Turulja et al., Citation2020). Policymakers should invest more in work-based education and entrepreneurship to enhance competitiveness. With this in mind, policymakers should strive toward nurturing increased collaboration between the private sector and educational organisations, enabling constructive knowledge transfer. Managers should comprehend that equipping an individual with the required knowledge, abilities, and self-confidence and instilling the idea of working as a versatile and receptive employee would contribute to augmenting the overall resilience of the organisation. Thus, a significant focus on nurturing the EC of the employees with appropriate training can go a long way in nurturing the entrepreneurial skills of the employees, which would manifest as prized and impalpable resources that result in any business’s success. Thus, such methods will necessitate long-term policy assurance and managerial attitudes towards promoting EC of employees because nurturing a more entrepreneurial ethos is a long-term procedure (Huggins & Williams, Citation2009).

7. Limitations of the study

Comprehending the study’s background necessitates unveiling the research procedure’s shortcomings. Discovering these limitations may also be a primary point for conducting further research. First of all, science mappings, as well as research profiling, are quantitative methods. These methods analyse a broad range of publications and provide an extensive and comprehensive picture of the research field, but they may lack a “deep dive” into the thematic parts of this study. However, we should consider the co-word analysis procedure’s limitations (keywords co-occurrence analysis in our study). They result from the fact that a few publications do not contain keywords; certain kinds of publications are probably understated in bibliometric records; and the quality of co-word evaluation relies on the quality of the indexing methods, something over which the authors have no control (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). As a result, it is suggested to utilise an eclectic and ambidextrous method that combines qualitative and quantitative procedures. Considering our evaluation results in conjunction with the studies constructed on other methodological methods, for instance, meta-analysis studies and qualitative literature analysis, is significant. Second, during identifying prominent and emergent topics with keyword co-occurrence analysis, the entire research field was the unit of evaluation. This indicates that the distinctions between several subject areas have not been considered. Hence, consequent studies emphasised the topical profiling of scientific productivity in essential subject areas (e.g., Environmental or Engineering Science, Business, Accounting, and Management); these appear to constitute an exciting line of research. Further, our keyword selection is based on our literature analysis and our definition of EC. There is a future possibility of other keywords emerging.

8. Future research and recommendations

The EC field seems less explored and demands higher research interest; however, more research is needed in developing countries. Naudé and Rossouw (Citation2010) posited that entrepreneurship and economic development in developing nations is an under-researched theme in entrepreneurial research. If such a wide range of research is encouraged and further growth of this concept in other institutional contexts, according to Scott (Citation2005), it would attain its broader objectives. A similar case has been found in EC research, whether in the context of the effect of entrepreneurship education on EC or EC as an antecedent factor of business performance or economic growth or EC of an economy. The scales used by different authors to measure EC, whether it be of an entrepreneur, a firm, or an economy, are not uniform. They vary with questions ranging from those based on opportunity perspective (identify, evaluate, and exploit opportunities); capacity to initiate and sustain a new firm (knowledge and experience); innovativeness and locus of control; and motivation and skills. However, a uniform way to measure EC has not yet emerged. Further, the measurement of entrepreneurship education on EC could be done with more contextual factors such as gender, family business background, and institutional factors (Scott, Citation2005).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Indian Council of Social Science and Research (ICSSR), a research grant (No. IMPRESS/P1083 /489/18-19/ICSSR).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ablo, A. D. (2015). Local content and participation in Ghana’s oil and gas industry: Can enterprise development make a difference? The Extractive Industries and Society, 2(2), 320–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2015.02.003

- Acs, Z. (2006). How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalisation, 1(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1162/itgg.2006.1.1.97

- Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., Braunerhjelm, P., & Carlsson, B. (2012). Growth and entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9307-2.

- Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9135-9

- Afzal, M. N. I., Mansur, K., & Manni, U. H. (2018). Entrepreneurial capability (EC) environment in ASEAN-05 emerging economies. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(2), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-01-2018-0002

- Ahlstrom, D., Chang, A. Y., & Cheung, J. S. (2019). Encouraging entrepreneurship and economic growth. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(4), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040178

- Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2005). How do entrepreneurs organise firms under conditions of uncertainty? Journal of Management, 31(5), 776–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279486

- Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Does entrepreneurship capital matter? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(5), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00055.x

- Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2008). Resolving the knowledge paradox: Knowledge-spillover entrepreneurship and economic growth. Research Policy, 37(10), 1697–1705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.08.008

- Azila-Gbettor, E. M., & Harrison, A. P. (2013). Entrepreneurship training and capacity building of Ghanaian Polytechnic graduates. International Review of Management and Marketing, 3(3), 102. https://econjournals.com/index.php/irmm/article/view/483

- Baker, H. K., Pandey, N., Kumar, S., & Haldar, A. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of board diversity: Current status, development, and future research directions. Journal of Business Research, 108, 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.025

- Baron, R. A., & Henry, R. A. (2010). How entrepreneurs acquire the capacity to excel: Insights from research on expert performance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.025

- Batte, G. B., & Da Silva, I. P. (2013). Entrepreneurial capacity, government intervention and diffusion of technologies in Uganda: Comparing the supply side of modern types of energy and mobile telephony technologies. In 2013 Proceedings of the 10th Industrial and Commercial Use of Energy Conference (1–9).

- Beaulieu, L. (2015, November 19). How many citations are actually a lot of citations? Retrieved 26 July 2020, https://lucbeaulieu.com/2015/11/19/how-many-citations-are-actually-a-lot-of-citations/#:~:text=With%2010%20or%20more%20citations,manuscript%20is%20clearly%20below%2010!

- Blanchflower, D. G. (2000). Self-employment in OECD countries. Labour Economics, 7(5), 471–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(0000011-7

- Bornmann, L., & Daniel, H. D. (2007). What do we know about the h index? Journal of the. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(9), 1381–1385. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20609

- Bornmann, L., Mutz, R., Neuhaus, C., & Daniel, H. D. (2008). Citation counts for research evaluation: Standards of good practice for analysing bibliometric data and presenting and interpreting results. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics, 8(1), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20609.

- Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Obloj, K. (2008). Entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Where are we today and where should the research go in the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00213.x

- Bullough, A., Renko, M., & Myatt, T. (2014). Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self–efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(3), 473–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12006

- Bygrave, W., Hay, M., Ng, E., & Reynolds, P. (2003). Executive forum: A study of informal investing in 29 nations composing the global entrepreneurship monitor. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 5(2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369106032000097021

- Carlisle, S., Kunc, M., Jones, E., & Tiffin, S. (2013). Supporting innovation for tourism development through multi-stakeholder approaches: Experiences from Africa. Tourism Management, 35, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.05.010

- Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2008). The lag structure of the impact of business ownership on economic performance in OECD countries. Small Business Economics, 30(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9007-0

- Carree, M., Van Stel, A., Thurik, R., & Wennekers, S. (2002). Economic development and business ownership: An analysis using data of 23 OECD countries in the period 1976–1996. Small Business Economics, 19(3), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:

- Cavallo, A., Ghezzi, A., Dell’Era, C., & Pellizzoni, E. (2019). Fostering digital entrepreneurship from start-up to scaleup: The role of venture capital funds and angel groups. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 145, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.04.022

- Cheng, S., Xu, G., Zhou, J., Qu, Y., Li, Z., He, Z., Yin, T., Ma, P., Sun, R., & Liang, F. (2020). A multimodal meta-analysis of structural and functional changes in the brain of tinnitus. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2020.00028

- Chhabra, M., Dana, L. P., Malik, S., & Chaudhary, N. S. (2021). Entrepreneurship education and training in Indian higher education institutions: A suggested framework. Education+ Training, 63(7/8), 1154–1174. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-10-2020-0310

- Chhabra, M., Dana, L. P., Ramadani, V., & Agarwal, M. (2021) A retrospective overview of journal of enterprising communities: People and places in the global economy from2007 to 2021 using abibliometric analysis. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy. Vol. ahead. Vol. aheadofprint No. ahead No. aheadofprint. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-06-2021-0091.

- Chhabra, M., & Karmarkar, Y. (2016). Effect of gender on inception stage of entrepreneurs: Evidence from small and micro enterprises in Indore. SEDME (Small Enterprises Development, Management & Extension Journal), 43(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0970846420160301

- Chhabra, M., Singh, L. B., & Mehdi, S. A. (2022) Women entrepreneurs’ success factors of Northern Indian community: A person–environment fit theory perspective. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy. Vol. ahead. Vol. aheadofprint No. ahead No. aheadofprint. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-04-2022-0059.

- Chreim, S., Spence, M., Crick, D., & Liao, X. (2018). Review of female immigrant entrepreneurship research: Past findings, gaps and ways forward. European Management Journal, 36(2), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.02.001

- Cisneros, L., Ibanescu, M., Keen, C., Lobato-Calleros, O., & Niebla-Zatarain, J. (2018). Bibliometric study of family business succession between 1939 and 2017: Mapping and analysing authors’ networks. Scientometrics, 117(2), 919–951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2889-1

- Clark, B. R. (1998). The entrepreneurial university: Demand and response. Tertiary Education and Management, 4(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02679392

- Clarysse, B., Tartari, V., & Salter, A. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurial capacity, experience and organisational support on academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1084–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.010

- Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011). Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1382–1402. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21525

- Colino, A., Benito-Osorio, D., & Rueda-Armengot, C. (2014). Entrepreneurship culture, total factor productivity growth and technical progress: Patterns of convergence towards the technological frontier. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 88, 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2013.10.007

- Collins, L. A., Smith, A. J., & Hannon, P. D. (2006). Discovering entrepreneurship: An exploration of a tripartite approach to developing entrepreneurial capacities. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(3), 188–205.

- Cunningham, E., & Moroz, P. (2008). Harmonising the concept of entrepreneurial capacity. Graduate School of Entrepreneurship (AGSE) Auckland.

- Dabić, M., Maley, J., Dana, L. P., Novak, I., Pellegrini, M. M., & Caputo, A. (2020). Pathways of SME internationalisation: A bibliometric and systematic review. Small Business Economics, 55(3), 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00181-6

- Dana, L. P. (1987). Towards a Skills Model for Entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 5(1), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.1987.10600284

- Dana, L. P. (2001). The education and training of entrepreneurs in Asia. Education + Training, 43(8), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006486

- Dana, L. P., & Dana, T. E. (2005). Expanding the scope of methodologies used in entrepreneurship research. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 2(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2005.006071

- Demil, B., & Lecocq, X. (2010). Business model evolution: In search of dynamic consistency. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.004

- De Soto, H. (1999). The Ethics of Capitalism. Journal of Markets and Morality, 2(2), 152–163. https://www.marketsandmorality.com/index.php/mandm/article/view/623

- D’Este, P., Mahdi, S., & Neely, A. (2010). Academic entrepreneurship: What are the factors shaping the capacity of academic researchers to identify and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities. Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics Working Paper No. 10, 5. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.13048/378

- De Tienne, D. R., & Chandler, G. N. (2004). Opportunity identification and its role in the entrepreneurial classroom: A pedagogical approach and empirical test. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3(3), 242–257. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2004.14242103

- Di Vaio, A., Hassan, R., Chhabra, M., Arrigo, E., & Palladino, R. (2022). Sustainable entrepreneurship impact and entrepreneurial venture life cycle: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 378, 134469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134469

- Escamilla-Fajardo, P., Núñez-Pomar, J. M., Ratten, V., & Crespo, J. (2020). Entrepreneurship and innovation in soccer: Web of SCIENCE BIBLIOMETRIC ANALYSIS. Sustainability, 12(11), 4499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114499.

- Etzkowitz, H. (1983). Entrepreneurial scientists and entrepreneurial universities in American academic science. Minerva, 21(2–3), 198–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01097964

- Faghih, N., Bonyadi, E., & Sarreshtehdari, L. (2019). Global entrepreneurship capacity and entrepreneurial attitude indexing based on the global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM) Dataset. In Faghih, N. (Ed.) Globalization and Development (pp. 13–55). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11766-5_2

- Fladmoe-Lindquist, K. (1996). International franchising: Capabilities and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(5), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(96)00056-0.

- Gartner, W. B. (1988). “Who is an entrepreneur?” is the wrong question. American Journal of Small Business, 12(4), 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225878801200401.

- Gibb, A. (1999). Can we build ‘effective’ entrepreneurship through management development?. Journal of General Management, 24(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/030630709902400401.

- Gibb, A., & Hannon, P. (2006). Towards the entrepreneurial university. International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 4(1), 73–110. http://www.ut-ie.com/articles/gibb_hannon.pdf

- González-Serrano, M. H., Crespo Hervás, J., Pérez-Campos, C., & Calabuig-Moreno, F. (2017). The importance of developing the entrepreneurial capacities in sport sciences university students. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 9(4), 625–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1316762.

- Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2019). A research agenda for entrepreneurship and innovation: The role of entrepreneurial universities. In D. B. Audretsch, E. E. Lehmann, & A. N. Link (Eds.), A research agenda for entrepreneurship and innovation (pp. 107–133). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2018-1126

- Gunes, S. (2012). Design entrepreneurship in product design education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 51, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.08.119.

- Guojin, C. (2011, September). Study on the education plan of the creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship ability in university students. In International Conference on Information and Management Engineering (305–311). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-24010-2_42.

- Hassan, R., Chhabra, M., Shahzad, A., Fox, D., & Hasan, S. (2021). A bibliometric analysis of journal of international women’s studies for period of 2002-2019: Current status, development, and future research directions. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 22(1), 1–37. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol22/iss1/1

- Hegarty, C., & Jones, C. (2008). Graduate entrepreneurship: More than child's play. Education+ Training, 50(7), 626–637.

- Hindle, K. (2002). Small-i or BIG-I? How entrepreneurial capacity transforms ‘small-I’ into ‘Big-I’ innovation: Some implications for national policy. Telecommunications Journal of Australia, 52(3), 51–63. http://www.kevinhindle.com/publications/C31.2002%20TJA%20Hin%20small%20i%20Big%20I%20Innovation%20Policy%20%2391FC.pdf

- Hindle, K. (2007). Teaching entrepreneurship at university: From the wrong building to the right philosophy. Handbook of Research in Entrepreneurship Education, 1, 104–126. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781847205377.00013

- Hindle, K. (2010). Skillful dreaming: Testing a general model of entrepreneurial process with a specific narrative of venture creation. Entrepreneurial Narrative Theory Ethnomethodology and Reflexivity, 1, 97–135.

- Hindle, K., & Yencken, J. (2004). Public research commercialisation, entrepreneurship and new technology based firms: An integrated model. Technovation, 24(10), 793–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(0300023-3

- Huggins, R., & Williams, N. (2009). Enterprise and public policy: A review of Labour government intervention in the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27(1), 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0762b.

- Jiménez, D. J., Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., Gattermann Perin, M., Sampaio, C. H., & Lengler, J. B. (2014). Entrepreneurial capacities as antecedents of business performance in Brazilian firms. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de l’Administration, 31(2), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1281.

- Karmarkar, Y., Chabra, M., & Deshpande, A. (2014). Entrepreneurial leadership style (s): A taxonomic review. Annual Research Journal of Symbiosis Centre for Management Studies, 2(1), 156–189. https://www.scmspune.ac.in/chapter/pdf/Chapter%2013.pdf

- Khan, Z., Lew, Y. K., & Marinova, S. (2019). Exploitative and exploratory innovations in emerging economies: The role of realised absorptive capacity and learning intent. International Business Review, 28(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.11.007

- Kim, S. J., & Choi, S. W. (2016). The Effect of Employee's Entrepreneurship Level (Capacity, Attitude, CEO Support) on Entrepreneurial Culture, Structure and Operation Systems of Corporate: Focused on Design Corporate in Korea. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship, 11(4), 103–116. https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO201631261180924.page

- Kim, S. S., & You, Y. Y. (2019). A study on the effect of successful factors of establishment on business performance and youth start-up firms’ competence. Restaurant Business, 15(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.26643/rb.v118i1.7254

- Klofsten, M., & Jones-Evans, D. (2000). Comparing academic entrepreneurship in Europe–the case of Sweden and Ireland. Small Business Economics, 14(4), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008184601282.

- Kochetkov, D. M., Larionova, V. A., & Vukovic, D. B. (2017). Entrepreneurial capacity of universities and its impact on regional economic growth. Economy of Region/EkonomikaRegiona, 13(2), 477–488. https://doi.org/10.17059/2017-2-13

- Korez-Vide, R., & Tominc, P. (2016). Competitiveness, entrepreneurship and economic growth. In Trąpczyński, P., Puślecki, Ł., & Jarosiński, M. (Eds.) Competitiveness of CEE economies and businesses (pp. 25–44). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39654-5_2

- Kothari, S., Handscombe, R. D., & Adcroft, A. (2007). Sweep or seep? Structure, culture, enterprise and universities. Management Decision, 45(1), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740710718953.

- Koufteros, X. A., Babbar, S., Behara, R. S., & Baghersad, M. (2020). OM research: Leading authors and institutions. Decision Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12452

- Kuratko, D. F., Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Hornsby, J. S. (2005). A model of middle–level managers’ entrepreneurial behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(6), 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00104.x.

- Kyrgidou, L., Mylonas, N., & Petridou, E. (2013). Identifying tomorrow’s entrepreneurs: Entrepreneurship education in Greece. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 9(3), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1504/WREMSD.2013.054739.

- Lee II, H. (2013). Mentoring nascent entrepreneurs: What leads to intention? Asia-Pacific. Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.16972/apjbve.8.2.201306.47

- Lee, S. M., & Peterson, S. J. (2000). Culture, entrepreneurial orientation, and global competitiveness. Journal of World Business, 35(4)(4), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(00)00045-6.

- Li, Y. H., Huang, J. W., & Tsai, M. T. (2008). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of knowledge creation process. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(4), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.02.004.

- Li, L., Qian, G., & Qian, Z. (2015). Should small, young technology–based firms internalise transactions in their internationalisation?. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 839–862. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12081.

- Lopez, Á. R., Souto, J. E., & Noblejas, M. L. A. (2019). Improving teaching capacity to increase student achievement: The key role of communication competences in Higher Education. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 60, 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.10.002.

- Lucas, J. R. E. (1978). On the size distribution of business firms. The Bell Journal of Economics, 9(2), 508–523. https://doi.org/10.2307/3003596.

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Enriching the entrepreneurial orientation construct-a reply to “entrepreneurial orientation or pioneer advantage”. Academy of Management Review, 21(3), 605–607. https://www.jstor.org/stable/258991

- Maritz, A. (2017). Illuminating the black box of entrepreneurship education programmes: Part 2. Education + Training, 59(5), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-02-2017-0018.

- Maritz, A., & Brown, C. R. (2013). Illuminating the black box of entrepreneurship education programs. Education + Training, 55(3), 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911311309305.

- Martins, R. M., Andery, G. F., Heberle, H., Paulovich, F. V., de Andrade Lopes, A., Pedrini, H., & Minghim, R. (2012). Multidimensional projections for visual analysis of social networks. Journal of Computer Science and Technology, 27(4), 791–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11390-012-1265-5.

- Mberi, C. F. (2019). Influencing entrepreneurial resilience to create sustainable business ventures (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria), http://hdl.handle.net/2263/68893.

- Naudé, W., & Rossouw, S. (2010). Early international entrepreneurship in China: Extent and determinants. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 8(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-010-0049-7.

- Newbert, S. L. (2008). Value, rareness, competitive advantage, and performance: A conceptual ‐level empirical investigation of the resource‐based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 29(7), 745–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.686.

- Nicolaou, N., Shane, S., Cherkas, L., & Spector, T. D. (2009). Opportunity recognition and the tendency to be an entrepreneur: A bivariate genetics perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 110(2), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.08.005.

- North, D., & Smallbone, D. (2006). Developing entrepreneurship and enterprise in Europe’s peripheral rural areas: Some issues facing policymakers. European Planning Studies, 14(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500339125.

- Norton, S. W. (1988). Franchising, brand name capital, and the entrepreneurial capacity problem. Strategic Management Journal, 9(S1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250090711.

- Oosterbeek, H., Van Praag, M., & Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. European Economic Review, 54(3), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.08.002.

- Otani, K. (1996). A human capital approach to entrepreneurial capacity. Economica, 63(250), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.2307/2554763.

- Palacios-Callender, M., & Roberts, S. A. (2018). Scientific collaboration of Cuban researchers working in Europe: Understanding relations between origin and destination countries. Scientometrics, 117(2), 745–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2888-2.

- Perkmann, M., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., Autio, E., Broström, A., D’Este, P., Krabel, S., Grimaldi, R., Hughes, A., Krabel, S., Kitson, M., Llerena, P., Lissoni, F., Salter, A., Sobrero, M., & Fini, R. (2013). Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Research Policy, 42(2), 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.09.007.

- Peterka, S. O., & Koprivnjak, P. M. J. T. (2017). Assessing entrepreneurial potential of university: Empirical evidence from Croatia. Marketing & Menedzsment, 59(4), 59–70. https://journals.lib.pte.hu/index.php/mm/article/view/868

- Peters, I., Kraker, P., Lex, E., Gumpenberger, C., & Gorraiz, J. (2015). Research data explored: Citations versus altmetrics, arXiv preprint arXiv:1501.03342. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1501.03342

- Pinho, J. C. (2017). Institutional theory and global entrepreneurship: Exploring differences between factor-versus innovation-driven countries. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 56–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-016-0193-9

- Prodi, R. (2002). For a new European entrepreneurship. Public speech. Instituto de Empresa.

- Pugh, R., Lamine, W., Jack, S., & Hamilton, E. (2018). The entrepreneurial university and the region: what role forentrepreneurship departments?European Planning Studies, 26(9), 1835–1855. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1447551