Abstract

The purpose of this research is to analyze the relationship between intellectual capital and organizational performance with the mediating rol of intrinsic motivation in higher education institutions. We conducted an empirical study with a sample of 815 employees from public and private universities in Ecuador. Data were obtained from an instrument adapted the previous researchadministered to faculty and administrative staff in management positions. A structural equation modelling approach was used to analyze the relationships between variables and their magnitude and direction. The results showed a significant relationship between intellectual capital and organizational performance, with a partial mediation of intrinsic motivation. No significant differences were found in the effect of intellectual capital between public and private universities. Managers who aim to improve the performance of their organizations with their intellectual capital can benefit from the intrinsic motivation of their employees. This research shows intrinsic motivation as a mediator between intellectual capital and organizational performance, but also analyzes their relationships based on the Self-Determination Theory, which is a novelty according to the existing literature.

1. Introduction

Organizations strive to achieve a performance that makes them stand out, meet the needs of their customers and stakeholders, and achieve sustained growth (Almatrooshi et al., Citation2016). Intellectual capital has been identified as an important element to improve the performance of organizations due to the competitive advantage that represents the accumulation of knowledge, for example, the ability to solve increasingly complex problems and the reduction of costs with process improvement (Mehralian et al., Citation2020). Some authors have also highlighted the importance of intellectual capital for organizational performance in higher education institutions (Chatterji & Kiran, Citation2017).

Intellectual capital is not easy to accumulate, it takes time, dedication and correct decision-making, which implies a cost that could be quantified (Juliya, Citation2015). However, making a great effort to accumulate intellectual capital is not enough to achieve the expected results (Bhandari et al., Citation2020), since there are organizations that have intellectual capital and still do not see it reflected in their performance (Khan et al., Citation2018; Rehman et al., Citation2021; Weqar et al., Citation2020). This problem affects many organizations, but particularly universities as they are more dependent on the accumulation of intellectual capital to create value and achieve a sustainable competitive advantage (DiBerardino & Corsi, Citation2018; Quintero-Quintero et al., Citation2021). Previous studies pointed out that intellectual capital in universities is necessary to improve their social image (Frondizi et al., Citation2019), their ranking (Brusca et al., Citation2019), their academic results (De Matos Pedro et al., Citation2020; Salinas-Ávila et al., Citation2020) and the fulfillment of objectives (Cricelli et al., Citation2018; Nicolò et al., Citation2021).

Intellectual capital is shown as a fundamental resource to give the organization a competitive advantage, however, it is still necessary to find the best way to acquire and adapt this resource considering the dynamics of changes (Barrena-Martínez et al., Citation2019). Intellectual capital increases the value of intangible assets through the application of knowledge, but it is the employees of the organization who create it and share it (Konno & Schillaci, Citation2021). However, the development and implementation of intellectual capital depends on the fact that members of the organization have the necessary knowledge and the will to use it and share it (Alvino et al., Citation2021). Thus, it is necessary to identify ways to improve the application of intellectual capital so that it can impact on the results of the organization (Weqar et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, there is little literature that establishes how intellectual capital should be increased and implemented (Ahmed et al., Citation2019; Konno & Schillaci, Citation2021) especially in higher education institutions (De Matos Pedro et al., Citation2020; Nicoló et al., Citation2020; Quintero-Quintero et al., Citation2021).

The knowledge-based view (KBV) theory points out that the resources of the organization that come from knowledge are essential to establish a sustainable competitive advantage because they drive cost efficiency, better customer relationships, innovation and creativity, which has an impact on a better performance (Kengatharan, Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2018). This could explain the fact that research on intellectual capital and its relationship with other variables has been conducted with that view, ignoring that resources are managed and implemented by the people who work in the organization, so human behavior plays a key role. The self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000) established a new perspective on the dynamics of human talent. The authors highlighted the need to maintain an adequate environment for the internal motivation of employees, which is a way to promote high-quality motivation and reflects in the results of the organization. In order to make that employees feel satisfied while performing their tasks without relying on external stimulus, it is essential that they feel competent and with the necessary resources. This will increase their productivity and performance (Rigby & Ryan, Citation2018). Internal motivation reduces negative aspects and increases positive aspects, which helps improve results (Manganelli et al., Citation2018).

Another aspect observed in the literature is the lack of clarity on the differences in the application and effectiveness of intellectual capital between public or private institutions (Barral et al., Citation2018; Guthrie et al., Citation2015). Quintero-Quintero et al. (Citation2021) carried out a bibliometric analysis of all research on intellectual capital since 1947 and, based on their opinion about the university setting, they did not find studies that differentiated the effect of intellectual capital in public and private higher education institutions.

In order to fill these literature gaps, this research proposes a theoretical model that includes intrinsic motivation as a key element of the relationship between said variables. This model includes intellectual capital as a second-order construct that has a positive relationship in organizational performance with the partial mediation of intrinsic motivation, besides considering the effects of intellectual capital if the organization is public or private.

This model contributes to close the knowledge gap in terms of the application of intellectual capital, its nature and its effect on the field of higher education (Barrena-Martínez et al., Citation2019; Quintero-Quintero et al., Citation2021). It also creates more knowledge about the benefits of intrinsic motivation in the organizational performance, which needs further research (Kuvaas et al., Citation2017; Mostafa et al., Citation2020; Scales et al., Citation2020) especially in the field of higher education (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). In addition, it analyzes the differences between public and private organizations in terms of the use of intellectual capital and its results, which is necessary and little studied nowadays (Guthrie et al., Citation2015; Yeganeh et al., Citation2014).

In order to achieve the above, we used a quantitative approach with a cross-sectional data collection and a structural model of equations. The study was conducted in public and private universities in several cities of Ecuador and the population included executives that carried out administrative tasks and planning. The next section of this manuscript presents the literature review and the justification of the hypotheses. Later, we explain the methodology, including the population, sample, data collection and instruments. The subsequent chapters present the data analysis and the results obtained, as well as the findings, implications, limitations and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature review and hypothesis

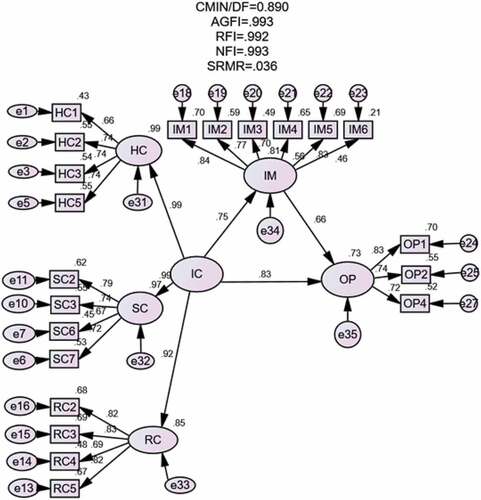

This research proposes a theoretical model that includes the positive impact of intellectual capital on the organizational performance, with a partial mediation of intrinsic motivation, in a higher education setting (Figure ). This section reviews the most important concepts of the study variables and how they are linked to each other, based on the proposed model.

2.1. Intellectual capital

Intellectual capital can be defined as the set of skills and experiences of the members of an organization that, combined with information and other resources, can guide its growth (Joshi et al., Citation2013). According to Agostini et al. (Citation2017), intellectual capital is composed of three main elements: human capital, organizational capital and relational capital. The first is the ability of employees to solve problems. In this category, it should be noted the importance of the creativity, experience and learning abilities of employees. The organizational capital is all the knowledge that remains in the company and does not come from its employees; it mostly relates to activities and processes. The relational capital is formed by the relationships established with external service providers, such as suppliers, customers and others, taking into account other relational resources such as reputation, brand and loyalty. External actors give the organization important resources and capabilities such as money for sales, raw materials and distribution channels.

Intellectual capital has been studied as a unique construct, but its elements have also been examined separately to consider their individual effects (Agostini et al., Citation2017). This is how we found different results in terms of the elements of intellectual capital, highlighting human capital, because according to some research it has had a greater influence on certain results of the organization, such as innovation (Barrena-Martínez et al., Citation2019) and commitment (Ouakouak & Ouedraogo, Citation2018). Managers have considered it a predictor of the performance of the human resource within the organization (Kianto et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, Aramburu and Sáenz (Citation2011) pointed out that human resources, given their specialized knowledge, represent an asset that is difficult to copy, thus, they have the potential to provide the organization with a competitive advantage.

2.2. Intrinsic motivation

The SDT theory shows two types of motivation: extrinsic and intrinsic. However, some authors have found difficulties when trying to explain it by integrating the two types of motivation instead of focusing on one at a time (Lombardi et al., Citation2019). Kuvaas et al. (Citation2017) recommended focusing on intrinsic motivation as a factor that can explain the results at work more accurately. Moreover, according to Ryan and Deci (Citation2020), intrinsic motivation is an expression of the active integrative tendency of the human being. Thus, their exploration in work activities is an example of behaviors that do not dependent on external incentives or pressures, but on satisfaction. When employees are intrinsically motivated, there will be higher quality consequences in terms of their behaviors and general well-being. When jobs have extrinsic rewards, employees do not significantly change their intrinsic motivation; on the contrary, some studies have shown that the extrinsic motivation grows at the expense of the intrinsic one (Dysvik et al., Citation2013).

Although the two types of motivation can coexist, in reality they are two separate dimensions and one of them may have greater influence than the other one (Gagné & Deci, Citation2005). Based on this fact, some authors created models that analyzed these constructs separately to understand their characteristics and their possible impact on organizations (Frey & Jegen, Citation2001). With the introduction of behavioral economics thought currents, the price effect suggests that external incentives do not alter intrinsic motivation and refer to it as the presumption of separability, which gives extrinsic motivation independence from the intrinsic one (Bowles & Polanía-Reyes, Citation2012).

2.3. Organizational performance

Organizational performance is the measure of the progress and development of the organization (Koohang et al., Citation2017). It can be considered as the comparison between actual results and expected results in the organization, taking into account its goals and objectives (Tomal & Jones, Citation2015). Some authors have considered that financial and non-financial parameters measure organizational performance. The financial parameters have to do with assets, revenues, profits or profitability (Liao & Wu, Citation2009), while the non-financial ones are related to innovation, competitive advantage, quality or continuous improvement (Kirby, Citation2005). However, other authors have noted the difficulty in determining a general list of measures that can be applied to all organizations.

In the case of higher education settings, Abubakar et al. (Citation2018) highlighted the superiority of non-financial measures to evaluate the acquisition of long-term competitive advantages and affirmed that it is necessary to measure the organizational results in this way.

These authors also stated that most higher education institutions use peers for accreditation based on their academic achievements; however, these results are difficult to interpret for anyone outside the academia, as is the case of some stakeholders. Likewise, quality used to be assessed only on the basis of the academic achievement of students, but non-academic aspects affecting students are now considered to be equally important. Based on this perspective, to measure the organizational performance of universities it is necessary to consider their objectives, student satisfaction, university responses, curriculum development, research productivity and research ranking (Iqbal et al., Citation2019).

2.4. Intellectual capital and intrinsic motivation

Intellectual capital is a resource that improves employee motivation and influences organizational performance (Li et al., Citation2021) because when employees feel motivated, their work performance improves (William & Pelto, Citation2021). Employees feel motivated when they know they have the necessary resources to improve their work (Deci et al., Citation2017). This self-awareness of their capacity is a source of internal satisfaction and encourages them to use those resources in their work and meet the goals (Bhandari et al., Citation2020). Based on this, we assumed that the feeling of having all the necessary resources stimulates the willing of employees to use them. Therefore, we posed the following hypothesis:

H1: Intellectual capital has a positive relationship with intrinsic motivation

2.5. Intrinsic motivation and organizational performance

Intrinsic motivation improves work production, not only in quantity but in quality (Garbers & Konradt, Citation2014). Kuvaas et al. (Citation2017) found a direct relationship between intrinsic motivation and employee performance. Çetin and Aşkun, (Citation2018) found a direct relationship between intrinsic motivation and the self-efficacy of employees. Within the context of education, Froiland and Worrell (Citation2016) and Taylor et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated that there is a relationship between intrinsic motivation and improvement in academic performance as well as in the outcomes of educational institutions.

Motivation is directly related to the commitment of the organization employees, the objectives and the organizational culture (Anra & Yamin, Citation2017), as well as the skills to execute tasks and work in an environment that allows individual development (Shoraj & Llaci, Citation2015). In addition, motivation gives employees the opportunity to act, create and develop (Deci et al., Citation2017; Muzafary et al., Citation2021) but also contributes to the generation of a greater performance (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020) through a high level of commitment to the organization (Kuvaas et al., Citation2017; Sabir, Citation2017). As a result, we posed the following hypothesis:

H2: Intrinsic motivation has a positive relationship with organizational performance

2.6. Intellectual capital and organizational performance

Several studies have shown a positive impact of the human, structural and relational dimensions of intellectual capital on the performance of organizations (Agostini et al., Citation2017). Although some authors prefer to measure it from an economic approach, intellectual capital improves the effectiveness and performance of the organization in general (Iqbal et al., Citation2019) by making available, from the human capital, the skills and capacities of the employees (Kengatharan, Citation2019); from the structural capital, the knowledge and business culture (Agostini et al., Citation2017); and from relational capital, the strengthening of relationships within and outside the organization (Bontis, Citation2011; Kengatharan, Citation2019). In this regard, an adequate level of intellectual capital should be reflected in better organizational performance and an increase in the competitive advantage (Shujahat et al., Citation2017). Thus, we posed the following hypothesis:

H3: Intellectual capital has a positive relationship with organizational performance.

2.7. Relationship between intellectual capital, intrinsic motivation and organizational performance

In order to achieve an adequate organizational performance it is necessary to have the employees motivated and this commitment mainly relies on the managers of the company because if they manage their subordinates effectively, the organization can be successful (Pirohov-Tóth, Citation2019). Within a company, motivation favors the internal part of the employees because it implies a great organizational commitment and make them see their professional prosperity with greater freedom in the work context (Liu et al., Citation2021; Martín et al., Citation2009). Therefore, motivation allows the exchange and use of knowledge, but also, positively influences the organizational performance (Jobira & Mohammed, Citation2021; Tran & Bich, Citation2018)

Likewise, motivation increases employee satisfaction levels and drives them to make the most of their knowledge, which is critical to individual and collective performance in organizations (Gagné & Deci, Citation2005; Ryan & Deci, Citation2020; Shoraj & Llaci, Citation2015; Vroom, Citation1964). In addition, it increases the level of satisfaction of individuals and leads them to fully use their knowledge, which is essential for the improvement of individual and collective performance within an organization (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020; Shujahat et al., Citation2017). Despite some authors highlighted the importance of rewards (Jyoti & Rani, Citation2017; Rohim & Budhiasa, Citation2019), recent research pointed out the counterproductive effects of external stimuli, as they cause individuals to be trapped in inertia and not act for the benefit of the organization if they are not rewarded. Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, has been shown to be directly related to the achievement of goals (Lombardi et al., Citation2019). Based on these theories, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H4: Intrinsic motivation mediates the positive effect of intellectual capital with organizational performance

Intellectual capital consists of intangible assets that create competitive advantage in the operations of an organization; however, there is a question that arises whether these intangible assets perform the same function or have the same influence if the organization is public or private (Quintero-Quintero et al., Citation2021). Wall (Citation2005) affirmed that the private sector is not aware of the importance of valuing non-tangible assets, while the public sector needs to look at non-financial results. Guthrie et al. (Citation2015) promoted more research on intellectual capital in the public sector due to significant differences between sectors of the economy to improve administration and strategic control, just as private organizations do. Some authors have identified differences between public and private universities in terms of key drivers to obtain their results (Klafke et al., Citation2020; Mohammadi & Karupiah, Citation2019), while others have not found significant differences (Barral et al., Citation2018). In this regard, the elements that form the intellectual capital have not shown homogeneity in their influence when they have been measured separately (Brusca et al., Citation2019; De Matos Pedro et al., Citation2020). As a result, we posed the following hypothesis:

H5: The effect of intellectual capital on intrinsic motivation is significantly different in public universities than in private universities

Recent research has found ambiguous results regarding the effect of intellectual capital on the organizational performance of public and private institutions. While the public sector can benefit more from intellectual capital due to public policies (Guthrie et al., Citation2015), the elements that form the intellectual capital can favor private universities due to the technology and organizational and personal capacities that are part of the strategic agility that is common in them (Lyn Chan & Muthuveloo, Citation2019). Some elements of intellectual capital could be affected due to dependence on public funds, especially in developing countries (Khalid et al., Citation2019). Based on the above, the effect of intellectual capital on organizational performance could vary depending on the type of organization; therefore, we posed the following hypothesis:

H6: The effect of intellectual capital on organizational performance is significantly different in public universities than in private universities.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Sampling and data collection

The population is represented by the personnel who work in higher education institutions, the research was conducted in Ecuador. Professors and university directors who perform planning and administration tasks because we considered they had the necessary knowledge to answer the questions. The questionnaire was emailed and data were collected between December 2021 and January 2022. The sample size was composed of 879 participants who were part of the 59 officially registered Ecuadorian universities. The average age of the participants was 46 years (SD = 8) and the seniority at work was 12 years (SD = 8). Table shows other important characteristics. After the data collection, we conducted an analysis to find lost or skewed data towards a single response. We eliminated 64 records and kept 815 valid observations. The sample size exceeded the minimum recommended by several authors to test a SEM model (Kline, Citation2011; Shi et al., Citation2018).

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

3.2. Instruments

Instruments taken from previous research in the literature were considered. For the intellectual capital variable and the organizational performance variable, we used the questionnaire created by Iqbal et al. (Citation2019), whereas for the intrinsic motivation variable, we used the questionnaire of Kuvaas et al. (Citation2017). Intellectual capital was a second-order construct that had three first-order reflective constructs: human capital with 5 indicators, structural capital with 7 indicators and relational capital with 5 indicators. Intrinsic motivation was a first-order construct with 6 indicators, while organizational performance had 5 indicators, which made it also a first-order construct. All these instruments were validated in previous research and obtained indicators that certify their reliability and convergent and discriminant validity. The items of the questionnaire were measured with a five-point Likert scale, with ranges that went from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

We used the double translation method for the questionnaire and administered it in Spanish. Two certified translators translated the questionnaire into Spanish and then back into English to compare it with the original. This procedure also improved the drafting of the questions. The Spanish translation of the questionnaire was analyzed by a group of eight experts, four university professors and four company directors from various sectors. The experts examined the appropriateness, relevance, formulation and content of the questions. Some questions were changed to ensure their understanding and accuracy; however, none were removed at this stage. We conducted a pilot test to ensure the correct understanding of the questions and measure their internal consistency using the Cronbach’s Alpha, which achieved a value greater than 0.7 (Nunnally, Citation1978). After all these procedures, we finally obtained the final version of the questionnaire (Appendix A1). In order to avoid a possible bias of the common method, due to the nature of the data collection process, we followed the procedures recommended by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003) regarding the psychological distance, drafting and ordering of the items of the questionnaire.

3.3. Method

In order to confirm the relationships between variables, we used a structural equation model and an unweighted least squares estimation. Following all the phases indicated by Weston and Gore (Citation2006) for the preliminary analysis of the data, we tested the measurement model and the structural model. Then, we carried out a confirmatory factor analysis to establish the measurement model and ensure the reliability as well as the convergent and discriminant validity. Later, we evaluated the structural model to measure the relationships between all the variables of the theoretical model and their adjustment.

4. Data analysis and results

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis to establish a priori the psychometric properties of the questionnaire and the possibility of a common method bias. The items included three dimensions as expected and no factor had more than 50% of the variance so the common method bias was not considered a risk. In order to verify the requirement of multivariate normality, we calculated the Mardia’s coefficient and obtained a value of 115, much higher than the value of 5, as suggested by Bentler (Citation1990), which indicates that the data did not follow a multivariate normal distribution. When analyzing the measurement model, we found adequate values in the composite reliability (CR) and in the average variance extracted (AVE); however, the discriminant validity was not satisfied for the IC and OP variables. The results in the goodness-of-fit tests were neither adequate. Using index modification, we identified the items with high correlation among the constructs and later eliminated HC4, SC1, SC4, SC5, RC1, OP3, and OP5.

Table shows the Cronbach’s Alpha values and the composite reliability, which had to be greater than 0.7 to prove the reliability of the items (Henseler et al., Citation2009; Nunnally, Citation1978). In the same table, we noted the average variance extracted, as a measure of convergent validity, with a value greater than .50 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981), which fulfilled all variables with this parameter. In addition, as a measure of convergent validity, we analyzed the factor loadings that were significant and greater than .70, with the exception of HC1 and RC4 that were very close to that value. We also revised item IM6 with a value of .457, but there was no need to eliminate it because the whole variable complied with the required values, and the other indicators were greater than .70.

Table 2. Validity and reliability results

For the discriminant validity analysis, we used the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (Henseler et al., Citation2015) that uses the correlations between indicators within each construct and the correlations of indicators between constructs. This method is more reliable than others commonly used (Hair et al., Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2015). Many authors suggests that the value of the ratio should be less than .85 for strict discriminatory validity and less than .90 for a more liberal one. As Table shows, there were no values lower than .85; therefore, it can be concluded that the main constructs had discriminating validity.

Table 3. Discriminant Validity using Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

In the end, we obtained adequate goodness-of-fit indices according to the acceptance ranges, as suggested by Hu and Bentler (Citation1999): Square root mean residual (SRMR) =.036, Adjusted Goodness of Fit (AGFI) =.993, Relative Fit Index (RFI) =.992, Normed Fit Index (NFI) =.993 and Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) =.866). This allowed us to conclude that the measurement model had a good overall adjustment, and we continued the analysis.

For the structural equations model, we used the AMOS 26 program and an unweighted least squares estimation. This method does not establish that the observed variables should follow a normal distribution. It is widely used in Likert-type questionnaires and is based on the polychoric correlation matrix (Bollen, Citation1989; Schumacher & Lomax, Citation1996). The model met the suggested values for goodness-of-fit indicators (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Kline, Citation2011), thus, we used to validate hypotheses about relationships between constructs. The coefficient of determination R2 of the dependent variable OP obtained a value of 0.734, which indicates that 73.4% of its variance was explained by the other two variables of the model. The results obtained and their cut-off points are summarized in Table .

Table 4. Results of measure index in structural model using ULS

According to these results, there is a direct, significant and positive effect between intellectual capital and intrinsic motivation (βstandardized = .751, p = .003); therefore, H1 was accepted. There is also a direct, positive and significant relationship between intrinsic motivation and organizational performance (βstandardized = .657, p = .002); thus, H2 was accepted. In addition, the results proved that there is a direct, positive and significant relationship between intellectual capital and organizational performance (βstandardized = .830, p = .002) (see results of direct effects in Figure and Table ). In order to verify the mediating effect of the intrinsic motivation variable, we used the bootstrapping technique and the results showed significance in the direct and indirect effects (see Table ). The intrinsic motivation had a partial mediating effect in the relationship between intellectual capital and organizational performance, so H4 was accepted.

Table 5. Test for direct effects between constructs with 95% confidence interval

Table 6. Test for mediation using a bootstrap analysis with 95% confidence interval

In order to identify whether the effect of intellectual capital on intrinsic motivation and organizational performance is different if universities are public or private, we conducted a multigroup analysis, which was useful to know if the factor structure of the model was significantly different or not, among the groups examined (Byrne, Citation2004). We established the configural invariance and metric invariance prior to the multigroup analysis. Likewise, to measure the configural invariance, we used the obtained measurement model and recalculated the goodness of fit indicators, first with the data of public universities and then with the data of private universities. The results obtained showed that adequate adjustment indicators were met considering the two groups (AGFI =.974, NFI=.971, RFI=.970, SRMR=.039). Therefore, we established the configural invariance and indicated that the measurement model was unique for public and private universities.

Regarding the metric invariance, following the recommendations of Cheung and Rensvold (Citation2002), we calculated the differences of the RFI and the NFI between the two groups using a general model and a restricted one with equal factor loadings. Under this analysis, if the difference was less than 0.01, the equality between the restricted and the unrestricted model had to be accepted, in this way, the invariance was fulfilled. As Table shows, in both cases the difference was less than 0.01, thus, the existence of metric invariance was confirmed, that is, the items measure the same throughout the two groups surveyed.

Table 7. Comparison of metric invariance indicators

For the multigroup analysis, it was necessary to determine whether the relationships proposed in the model differed according to the type of university. For this purpose, we measured the differences between the path coefficients of the model for public university and those of the model for private university, as well as its significance. The comparison of the restricted and unrestricted models showed a difference in chi-square of 11,007 (p = .088) which indicates that there were differences between the models. However, these differences were found within the second-order construct. Table shows the results obtained from the individual analysis. We noted that the relationship between intellectual capital and intrinsic motivation did not vary significantly between public and private universities, therefore, H5 was not accepted. Likewise, the relationship between intellectual capital and organizational performance did not differ significantly between public and private universities, therefore, H6 was not accepted. However, it should be noted the dynamics between first-order constructs and intellectual capital, which is a second-order construct. The relationship between intellectual capital and structural capital was stronger in public universities, just as the relationship between intellectual capital and human capital. On the other hand, the relationship between intellectual capital and relational capital was stronger in private universities. The evaluation of the hypotheses has been summarized in Table .

Table 8. Differences in factor loadings according to type of institution

Table 9. Summary of results of hypothesis tests based on the Structural Equation Model

5. Discussion

The purpose of this research was to test the relationship between intellectual capital and organizational performance with the mediation of intrinsic motivation. The results showed a positive impact of intellectual capital on intrinsic motivation. Therefore, we can affirm the resources of the organization influence the intrinsic motivation of the employees and this can be explained by the basic elements of intrinsic motivation such as autonomy and trust. When employees know they have all the resources and skills, they decide to use them and see their tasks as a motivation, without the need for external stimuli (Deci et al., Citation2017).

The data analysis also showed that intellectual capital has a positive impact on organizational performance. This is consistent with previous results, and although this relationship has been extensively studied in some industries, it has not been the same in the field of higher education. In this regard, Cricelli et al. (Citation2018) found in Colombian universities a positive relationship between the three elements of intellectual capital and the organizational performance by measuring them separately. It was also found that the universities with the greatest intellectual capital are those that excel in performance. Tjahjadi et al. (Citation2019) found a relationship between IC and OP in universities in Indonesia using intellectual capital as a construct with three dimensions. Both studies, conducted in developing countries, considered public institutions that were previously measured by their research, education and community service for development. The relationship between the acquisition of intellectual capital and the performance of higher education institutions in this case suggested that its accumulation, management and dissemination help universities to improve their role before their stakeholders and may generate a greater influence in society in the future. This is in line with the study of Bisogno et al. (Citation2018), who stated that the future of intellectual capital in universities should have a greater impact on the daily lives of people.

The results also showed a direct relationship between intrinsic motivation and organizational performance. More than a century of research on motivation and its relationship with work has shown that goal orientation and resource placement are important elements that are repeated on time and everywhere (Kanfer et al., Citation2017). Kuvaas et al. (Citation2017) found that intrinsic motivation is positively related to the positive results of the organization and that it is better to measure it as a separate construct. They concluded that organizations should make every effort to increase the intrinsic motivation of their employees if they want to improve performance. The results are especially significant for higher education institutions, since intrinsic motivation is one of the most significant elements in a learning environment (Fırat et al., Citation2017).

The relationships that were identified also showed a partial mediation of the intrinsic motivation in the positive relationship of intellectual capital with organizational performance. This suggests that the intangible resources that form intellectual capital facilitate the intrinsic motivation by giving employees confidence in their skills to use said resources and meet the entrusted goals. According to the SDT theory, when employees feel they have autonomy and competence to do their work, their satisfaction and intrinsic motivation increase, as well as their performance, which benefits the entire organization (Gagné & Deci, Citation2005). Curiosity and exploration are behaviors promoted by intrinsic motivation and do not depend on external incentives; besides bringing satisfaction and joy, this type of motivation represents an important aspect in the learning process and actions of organizations (Deci et al., Citation2017). The SDT theory is very convenient in the higher education setting, since elements such as motivation and psychological well-being are especially relevant for the academic environment (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). These results are consistent with the approach that states that interactions between organizational structures and employee motivation shape organizational performance (Jinhai et al., Citation2021).

The results also showed that there are no significant differences between public and private universities in terms of the effect of intellectual capital, both in intrinsic motivation and in organizational performance. This is a novelty since there are no previous research on this type of analysis in a university setting, and contradicts the findings of Yeganeh et al. (Citation2014), who noted differences in the effect of the elements of intellectual capital on public and private insurance companies in Iran. In this research, the benefits of having intangible assets that provide a strategic advantage to the organizations seem to be the same regardless of how they obtain their funds. This can be explained by the fact that the most valuable resources of universities are the knowledge and expertise of their professors, researchers and managers, but also their interaction with their students and society in general, which creates a value that is difficult to imitate by other organizations (Quintero-Quintero et al., Citation2021).

6. Conclusions and implications

This study provides a deeper understanding of the relationships between intellectual capital, intrinsic motivation and organizational performance in higher education institutions. There are two main conclusions that should be highlighted. The first is that regardless of whether the organization strives to build its intellectual capital to improve its performance, it is the people who ultimately use those resources in the daily processes that create value, and if they are not internally motivated, the expected results may not be achieved. The second has to do with the dynamics of the elements of intellectual capital according to the type of organization. In higher education institutions, intellectual capital has a bigger impact on the elements that form them, depending on whether the organization is public or private. This opens up new questions, but also has theoretical and practical implications.

This research shows theoretical contributions by showing the integration between fundamental concepts of two different theories. The KBV theory highlights the knowledge of the members of the organization as a source of competitive advantage, but does not consider human behavior as a fundamental factor for the use and dissemination of that knowledge. The SDT theory helps integrate that element to explain why the results may not be as expected despite having accumulated intellectual capital. The present study opens new perspectives for the research on intellectual capital as a second-order construct, since there could be differences in the contribution of each element of intellectual capital in public and private organizations, at least in the higher education setting.

These results may change the perception of managers, in terms of the automatic application of intellectual capital, highlighting the need for a strategy that aligns the employees with the expected results of the organization. This strategy requires well-defined policies in the management of human talent, especially in the recruitment, selection and training. It is also important to improve the effectiveness of assigning tasks to the right individuals and to monitor that they are motivated by achievement. Finally, managers should closely monitor the way in which each element of intellectual capital contributes, without assuming that they all contribute equally and taking actions to improve their results.

7. Limitations and future research

This research was conducted in a university setting and included the participation of managers. Future research could consider interviewing other important actors in universities. In addition, we recommend to test the theoretical model in other settings to establish similarities or differences, which will contribute to the generalization of the results. Other studies could focus on the differences in the effect of intellectual capital according to some other characteristics of the organization, such as the size of the organization. Finally, the effect of intellectual capital elements could be measured separately to isolate their individual effects and gain greater insight into their behavior in organizations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abubakar, A., Hilman, H., & Kaliappen, N. (2018). New tools for measuring global academic performance. Sage Open, 8(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018790787

- Agostini, L., Nosella, A., & Filippini, R. (2017). Does intellectual capital allow improving innovation performance? A quantitative analysis in the SME context. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18(2), 400–418. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-05-2016-0056

- Ahmed, S. S., Guozhu, J., Mubarik, S., Khan, M., & Khan, E. (2019). Intellectual capital and business performance: The role of dimensions of absorptive capacity. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 21(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/jic-11-2018-0199

- Almatrooshi, B., Singh, S. K., & Farouk, S. (2016). Determinants of organizational performance: A proposed framework. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65(6), 844–859. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijppm-02-2016-0038

- Alvino, F., DiVaio, A., Hassan, R., & Palladino, R. (2021). Intellectual capital and sustainable development: A systematic literature review. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 22(1), 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-11-2019-0259

- Anra, Y., & Yamin, M. (2017). Relationships between lecturer performance, organizational culture, leadership, and achievement motivation. Foresight and STI Governance, 11(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.17323/2500-2597.2017.2.92.97

- Aramburu, N., & Sáenz, J. (2011). Structural capital, innovation capability, and size effect: An empirical study. Journal of Management & Organization, 17(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2011.17.3.307

- Barral, M. R. M., Ribeiro, F. G., & Canever, M. D. (2018). Influence of the university environment in the entrepreneurial intention in public and private universities. RAUSP Management Journal, 53(1), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rauspm.2017.12.009

- Barrena-Martínez, J., Livio, C., Ferrándiz, E., Greco, M., & Grimaldi, M. (2019). Joint forces: Towards an integration of intellectual capital theory and the open innovation paradigm. Journal of Business Research, 112, 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.029

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Bhandari, K. R., Rana, S., Paul, J., & Salo, J. (2020). Relative exploration and firm performance: Why resource-theory alone is not sufficient? Journal of Business Research, 118, 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.001

- Bisogno, M., Dumay, J., Manes Rossi, F., & Tartaglia Polcini, P. (2018). Identifying future directions for IC research in education: A literature review. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19(1), 10–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/jic-10-2017-0133

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004

- Bontis, N. (2011). Assessing knowledge assets: A review of the models used to measure intellectual capital. International Journal of Management Reviews, 3(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2370.00053

- Bowles, S., & Polanía-Reyes, S. (2012). Economic incentives and social preferences: Substitutes or complements? Journal of Economic Literature, 50(2), 368–425. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.2.368

- Brusca, I., Cohen, S., Manes-Rossi, F., & Nicolò, G. (2019). Intellectual capital disclosure and academic rankings in European universities. Meditari Accountancy Research, 28(1), 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/medar-01-2019-0432

- Byrne, B. M. (2004). Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(2), 272–300. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1102_8

- Çetin, F., & Aşkun, D. (2018). The effect of occupational self-efficacy on work performance through intrinsic work motivation. Management Research Review, 41(2), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-03-2017-0062

- Chatterji, N., & Kiran, R. (2017). Role of human and relational capital of universities as underpinnings of a knowledge economy: A structural modelling perspective from north Indian universities. International Journal of Educational Development, 56, 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.06.004

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

- Cricelli, L., Greco, M., Grimaldi, M., & Llanes Dueñas, L. P. (2018). Intellectual capital and university performance in emerging countries. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19(1), 71–95. https://doi.org/10.1108/jic-02-2017-0037

- Deci, E., Olafsen, A., & Ryan, R. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych032516-113108

- De Matos Pedro, E., Alves, H., & Leitão, J. (2020). In search of intangible connections: Intellectual capital, performance and quality of life in higher education institutions. Higher Education, 83(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00653-9

- DiBerardino, D., & Corsi, C. (2018). A quality evaluation approach to disclosing third mission activities and intellectual capital in Italian universities. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19(1), 178–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/jic-02-2017-0042

- Dysvik, A., Kuvaas, B., & Gagné, M. (2013). An investigation of the unique, synergistic, and balanced relationships between basic psychological needs and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(5), 1050–1064. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12068

- Fırat, M., Kılınç, H., & Yüzer, T. V. (2017). Level of intrinsic motivation of distance education students in e-learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12214

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Frey, B. S., & Jegen, R. (2001). Motivation crowding theory. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(5), 589–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00150

- Froiland, J. M., & Worrell, F. C. (2016). Intrinsic motivation, learning goals, engagement, and achievement in a diverse high school. Psychology in the Schools, 53(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21901

- Frondizi, R., Fantauzzi, C., Colasanti, N., & Fiorani, G. (2019). The evaluation of universities’ third mission and intellectual capital: Theoretical analysis and application to Italy. Sustainability, 11(12), 3455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123455

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

- Garbers, Y., & Konradt, U. (2014). The effect of financial incentives on performance: A quantitative review of individual and team-based financial incentives. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 102–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12039

- Guthrie, J. & Dumay, J. (2015). New frontiers in the use of intellectual capital in the public sector. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 16(2), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1108/jic-02-2015-0017

- Hair, J., Hult, G., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C., & Sinkovics, R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

- Hu, L. -T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Iqbal, A., Latif, F., Marimon, F., Sahibzada, U. F., & Hussain, S. (2019). From knowledge management to organizational performance: Modelling the mediating role of innovation and intellectual capital in higher education. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(1), 36–59. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-04-2018-0083

- Jinhai, Y., Checkland, K., Wilson, P. M., & Howard, S. J. (2021). Agency autonomy, public service motivation, and organizational performance. Public Management Review, 25(1), 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1980290

- Jobira, A. F., & Mohammed, A. A. (2021). Predicting organizational performance from motivation in Oromia Seed Enterprise Bale Branch. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 8(66), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00742-9

- Joshi, M., Cahill, D., Sidhu, J., & Kansal, M. (2013). Intellectual capital and financial performance: An evaluation of the Australian financial sector. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 14(2), 264–285. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691931311323887

- Juliya, T. (2015). Intellectual capital cost management. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 792–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00439-6

- Jyoti, J., & Rani, A. (2017). High performance work system and organisational performance: Role of knowledge management. Personnel Review, 46(8), 1770–1795. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2015-0262

- Kanfer, R., Frese, M., & Johnson, R. E. (2017). Motivation related to work: A century of progress. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000133

- Kengatharan, N. (2019). A knowledge-based theory of the firm: Nexus of intellectual capital, productivity and firms’ performance. International Journal of Manpower, 40(6), 1056–1074. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2018-0096

- Khalid, N., Ahmed, U., Tundikbayeva, B., & Ahmed, M. (2019). Entrepreneurship and organizational performance: Empirical insight into the role of entrepreneurial training, culture and government funding across higher education institutions in Pakistan. Management Science Letters, 9(5), 755–770. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.1.013

- Khan, S. Z., Yang, Q., & Waheed, A. (2018). Investment in intangible resources and capabilities spurs sustainable competitive advantage and firm performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1678

- Kianto, A., Sáenz, J. Y., & Aramburu, N. (2017). Knowledge-based human resource management practices, intellectual capital and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 81, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.07.018

- Kirby, J. (2005). Toward a theory of high performance. Harvard Business Review, 83(7), 30–39.

- Klafke, R., De Oliveira, M. C. V., & Ferreira, J. M. (2020). The good professor: A comparison between public and private universities. Journal of Education, 200(1), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022057419875124

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Methodology in the social sciences. principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Konno, N., & Schillaci, E. S. (2021). Intellectual capital in society 5.0 by the lens of the knowledge creation theory. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 22(3), 478–505. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-02-2020-0060

- Koohang, A., Paliszkiewicz, J., & Goluchowski, J. (2017). The impact of leadership on trust, knowledge management, and organizational performance: A research model. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 521–537. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-02-2016-0072

- Kuvaas, B., Buch, R., Weibel, A., Dysvik, A., & Nerstad, C. G. L. (2017). Do intrinsic and extrinsic motivation relate differently to employee outcomes? Journal of Economic Psychology, 61, 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2017.05.004

- Liao, S. H., & Wu, C. C. (2009). The relationship among knowledge management, organizational learning, and organizational performance. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(4), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v4n4p64

- Li, S., Jia, R., Seufert, J., Hu, W., & Luo, J. (2021). The impact of ability-, motivation- and opportunity-enhancing strategic human resource management on performance: The mediating roles of emotional capability and intellectual capital. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 60(3), 453–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12293

- Liu, X., Lyu, B., Fan, J., Yu, S., Xiong, Y., & Chen, H. (2021). A study on influence of psychological capital of Chinese university teachers upon job thriving: Based on motivational work behavior as an intermediary variable. Sage Open, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211003093

- Lombardi, S., Cavaliere, V., Giustiniano, L., & Cipollini, F. (2019). What money cannot buy: The detrimental effect of rewards on knowledge sharing. European Management Review, 17(1), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12346

- Lyn Chan, J. I., & Muthuveloo, R. (2019). Antecedents and influence of strategic agility on organizational performance of private higher education institutions in Malaysia. Studies in Higher Education, 46(8), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1703131

- Manganelli, L., Thibault Landry, A., Forest, J., & Carpentier, J. (2018). Self-determination theory can help you generate performance and well-being in the workplace: A review of the literature. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 20(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422318757210

- Martín, N., Martín, V., & Trevilla, C. (2009). The influence of employee motivation on knowledge transfer. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13(6), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270910997132

- Mehralian, G., Peikanpour, M., Rangchian, M., & Aghakhani, H. (2020). Managerial skills and performance in small businesses: The mediating role of organizational climate. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 14(3), 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-02-2019-0041

- Mohammadi, S., & Karupiah, P. (2019). Quality of work life and academic staff performance: A comparative study in public and private universities in Malaysia. Studies in Higher Education, 45(6), 1093–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1652808

- Mostafa, A. A., Hussin, N., Jabbar, H. K., Ibithal, A., Othman, R., & Mohammed, A. (2020). Intellectual capital and firm performance classification and motivation: Systematic literature review. Test Engineering and Management, 83, 28691–28703.

- Muzafary, S., Ali, I., Hussain, M., Mdletshe, B., Tilwani, S. A., & Khattak, R. (2021). Intrinsic rewards and employee creative performance: Moderating effects of job autonomy and proactive personality: A perspective of self-determination theory. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 15(2), 701–725. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6464124

- Nicoló, G., Manes-Rossi, F., Christiaens, J., & Aversano, N. (2020). Accountability through intellectual capital disclosure in Italian Universities. Journal of Management & Governance, 24(4), 1055–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-019-09497-7

- Nicolò, G., Raimo, N., Polcini, P. T., & Vitolla, F. (2021). Unveiling the link between performance and Intellectual Capital disclosure in the context of Italian public universities. Evaluation and Program Planning, 88, 101969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.101969

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Ouakouak, M. L., & Ouedraogo, N. (2018). Fostering knowledge sharing and knowledge utilization. Business Process Management Journal, 25(4), 757–779. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-05-2017-0107

- Pirohov-Tóth, B. (2019). Role of management in the effect on employee motivation of organizational performance – Hungarian case study. Journal of Economics and Business, 2(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3413667

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Quintero-Quintero, W., Blanco-Ariza, A., Garzón, M., & Mikhailov, O. (2021). Intellectual capital: A review and bibliometric analysis. Publications, 9(4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9040046

- Rehman, U., Aslam, E., & Iqbal, A. (2021). Intellectual capital efficiency and bank performance: Evidence from Islamic banks. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22(1), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2021.02.004

- Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2018). Self-determination theory in human resource development: New directions and practical considerations. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 20(2), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422318756954

- Rohim, A., & Budhiasa, I. G. S. (2019). Organizational culture as moderator in the relationship between organizational reward on knowledge sharing and employee performance. Journal of Management Development, 38(7), 538–560. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-07-2018-0190

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

- Sabir, A. (2017). Motivation: Outstanding way to promote productivity in employees. American Journal of Management Science and Engineering, 2(3), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajmse.20170203.11

- Salinas-Ávila, J., Abreu-Ledón, R., & Tamayo-Arias, J. (2020). Intellectual capital and knowledge generation: An empirical study from Colombian public universities. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 21(6), 1053–1084. https://doi.org/10.1108/jic-09-2019-0223

- Scales, P. C., Van Boekel, M., Pekel, K., Syvertsen, A. K., & Roehlkepartain, E. C. (2020). Effects of developmental relationships with teachers on middle‐school students’ motivation and performance. Psychology in the Schools, 57(4), 646–677. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22350

- Schumacher, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (1996). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Shi, D., Lee, T., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2018). Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 79(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418783530

- Shoraj, D., & Llaci, S. (2015). Motivation and its impact on organizational effectiveness in Albanian businesses. Sage Open, 5(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015582229

- Shujahat, M., Ali, B., Nawaz, F., Durst, S., & Kianto, A. (2017). Translating the impact of knowledge management into knowledge-based innovation: The neglected and mediating role ofknowledge-worker satisfaction. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 28(4), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20735

- Taylor, G., Jungert, T., Mageau, G. A., Schattke, K., Dedic, H., Rosenfield, S., & Koestner, R. (2014). A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39(4), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.08.002

- Tjahjadi, B., Soewarno, N., Astri, E., & Hariyati, H. (2019). Does intellectual capital matter in performance management system-organizational performance relationship? Experience of higher education institutions in Indonesia. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 20(4), 533–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-12-2018-0209

- Tomal, D. R., & Jones, K. J. (2015). A comparison of core competencies of women and men leaders in the manufacturing industry. The Coastal Business Journal, 14(1), 13–25.

- Tran, G., & Bich, N. (2018). Factors affecting work motivation of office workers – a study in ho chi minh city, vietnam. Journal B&It, 2(2), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.14311/bit.2018.02.01

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley & Sons.

- Wall, A. (2005). The measurement and management of intellectual capital in the public sector. Public Management Review, 7(2), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030500091723

- Weqar, F., Khan, A. M., Raushan, M. A., & Haque, S. M. I. (2020). Measuring the impact of intellectual capital on the financial performance of the finance sector of India. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 12(3), 1134–1151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-020-00654-0

- Weston, R., & Gore, P. A. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 719–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345

- William, Y. D., & Pelto, E. (2021). Customer knowledge sharing in cross-border mergers and acquisitions: The role of customer motivation and promise management. Journal of International Management, 27(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2021.100858

- Yeganeh, M. V., Sharahi, B. Y., Mohammadi, E., & Beigi, F. H. (2014). A survey of intellectual capital in public and private insurance companies of Iran case: Tehran City. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 602–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.754

- Zhang, M., Qi, Y., Wang, Z., Pawar, K. S., & Zhao, X. (2018). How does intellectual capital affect product innovation performance? Evidence from China and India. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 38(3), 895–914. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-10-2016-0612