Abstract

Expediency is subtle, but it is detrimental to the organization. This study aims to discover what at the workplace prompts supervisor expediency. Based on the literature, it is predicted that supervisor expediency results from high-performance goals. Furthermore, supervisor bottom-line mentality acts as a moderator between high-performance goals and supervisor expediency such that a high bottom-line mentality strengthens this relationship. The present study’s theoretical framework is grounded on a transactional model of stress and coping. Two source data (supervisor-subordinate) are collected from the private health sector of Pakistan, and the sample size is 591 supervisor-subordinate dyads. Findings support the hypotheses formulated in this study. Statistical results underline that high-performance goals lead to supervisor expediency. Moreover, results confirm the moderating effect of supervisor bottom line mentality. Implications and research directions for the future are also highlighted.

1. Introduction

High-profile ethical scandals around the world have shown the ubiquity of unethical behavior in corporations and how these firms have paid the price (Niven & Healy, Citation2016). Recent scandals, such as the Boeing 737 Max, have demonstrated how businesses succumb to bottom line pressure and expediency (Yglesias, Citation2019). Similarly, the chief executive officer, chief operating officer, and board of directors of Wirecard AG Corporation, a financial services provider, were found guilty of unethical behavior (Aziz, Citation2020). These crises brought to light the far-reaching implications of unethical workplace behavior.

According to scholars, systematic research on unethical behavior began in the 1980s (Treviño et al., Citation2014). Over time, research on unethical behavior has emerged, attracting the attention of both researchers and practitioners. In the past 39 years, scholars’ increased interest in workplace ethics has resulted in a large amount of literature. This research includes both qualitative and quantitative findings (Ahn et al., Citation2018; Kalshoven et al., Citation2016). Because of the negative consequences of work-related unethical behaviors, experts have spent the last three decades researching the origins and effects of such behavior (Kish-Gephart et al., Citation2010). However, most of the studies in the literature concentrated on overt unethical behavior, leaving covert unethical behavior as an understudied phenomenon (Eissa, Citation2020; Greenbaum et al., Citation2018). Recently, expediency has been discussed as a form of covert unethical behavior at the workplace. Expediency in the workplace exists at all levels of the hierarchy and can be harmful (Jonason & O’Connor, Citation2017; Parks et al., Citation2010). Although expediency is elusive, it nonetheless harms the organization (Ren et al., Citation2021). These researchers underlined that, despite the fact that expediency might have negative consequences for businesses, it is understudied and needs researchers’ attention. This research focuses on supervisory expediency (SE), defined as unethical leadership action that goes against societal moral expectations (Treviño et al., Citation2006). However, Parks et al. (Citation2010) highlighted that supervisors might use expediency on a regular basis to run their businesses more efficiently. When supervisors cut corners to finish work assignments faster or manipulate performance figures to appear more effective, they engage in expediency. This study explores a type of unethical supervision known as supervisor expediency, which is less morally severe and more widespread than other forms of unethical activity. Till to date, research on supervisory expediency is very limited, and scholars have emphasized examining antecedents and consequences of supervisor expediency (R. L. Greenbaum et al., Citation2018). This study is in response to these researchers’ call for an investigation.

In previous researche, it is underlined that leaders at work face constant pressures (Joosten et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the persistent pressure that leaders are subjected to may weaken the determination required to follow ethical norms and standards, leading to unethical behavior. Overworked executives are more likely to break ethical standards. One of the most difficult challenges that organizational leaders have is staying focused on ethical behavior during their fragmented, chaotic, and disorderly workdays. Indeed, several ethical failures within firms, such as fraud and corruption, that have been exposed in the media over the previous decade clearly emphasize organizational leaders to function ethically. Indeed, if leaders concentrate on acting ethically, they can be a valuable source of moral direction for their followers (Brown et al., Citation2005; Walumbwa et al., Citation2011). It is proposed in this study that the continual burden that leaders in organizations feel can reduce the determination needed to behave ethically. This deficiency of psychological energy may have unfavorable outcomes. One of the main pressure in today’s contemporary organizations is organizational set high-performance goals (HPGs). In the modern business world, goals are everywhere. However, many high-profile business scandals have raised serious concerns about the inadvertent implications of HPGs. For instance, Wells Fargo was fined a huge some of amount in 2016 after it was revealed that workers had issued unlawful credit cards over 500,000 and created unapproved customer accounts up to 3.5 million to reach ambitious sales targets (Glazer, Citation2016). Conferring to emerging scholarly research on the dark side of goal creation, HPG enhances unethical behavior relative to low or “do your best” goals (Welsh & Ordóñez, Citation2014b). According to researchers, immoral effects from performance goals are generally the result of goals being set excessively high (Ordóñez & Welsh, Citation2015; Schweitzer et al., Citation2004).

Many company leaders pursue bottom-line goals with zeal and determination in the hopes of outperforming their competitors. Many business leaders believe that the only way to make their firms profitable and have a fantastic career is to focus solely on the bottom line. However, critics contend that this devotion has resulted in countless scandals that have permanently tarnished great company reputations and lost individual investors their life savings. Bottom-line mentality (BLM), which consists of a single-minded pursuit of financial profit while neglecting ethical considerations, may be ubiquitous in high-profile company disasters like Enron, WorldCom, Volkswagen, HealthSouth, and GM (Callahan, Citation2007; Hotten, Citation2015; Isidore, Citation2015).

The current study aims to contribute to the literature in a number of ways, both theoretical and practical. Contribution to research on unethical leadership in the first place. To date, the majority of unethical supervision research has focused on supervisors mistreating subordinates (Brown & Mitchell, Citation2010) or on unethical leadership in broad terms (Craig & Gustafson, Citation1998). In the present study, it is believed that examining SE as a sort of unethical leader behavior is worthwhile because taking corners and breaching regulations to boost one’s performance can appear to be smart and efficient (Parks et al., Citation2010). The current study’s objective is to investigate why and when supervisors may engage in expediency at the workplace. Secondly, this study advances the nomological network of SE a widespread yet understudied phenomenon. This study draws on the transactional model of stress and coping while building a conceptual framework (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984) and propose that one significant and unexamined source of supervisor expedient behavior is high-performance goals. More than thousands of study supports the notion that high-performance goals yield positive outcomes. However, empirical investigation on the dark side of HPGs is limited. This study empirically tests the relationship between HPGs and SE. Third, integration of the transactional model of stress and coping with high-performance and expediency research. The transactional model of stress and coping, also known as the cognitive theory of stress, describes coping as a process including both cognitive and behavioral reactions that people utilize to cope with internal and external pressures that exceed their resources. Fourth, our study extends the research on supervisor bottom-line mentality (SBLM) by examining its exacerbating effect, and the findings also add to the limited but growing body of knowledge on BLM.

2. Literature review

2.1. High-performance goals and supervisor expediency

In today’s workplace, goals are everywhere. Goals are the purpose or intent of an action, such as achieving a given level of expertise within a specified time frame (Locke & Latham, Citation2015). HPGs in goal-setting theory are defined as specified and tough performance objectives (Locke & Latham, Citation1990). Further, these scholars recommend setting HPGs at the 90th percentile. Despite the clear correlation between high goals and performance, several kinds of research have revealed that goal formation may have a negative side. High goals have been demonstrated to generate stress and worry, create a competitive mindset and reduce self-esteem in some cases (Poortvliet & Darnon, Citation2010; Soman & Cheema, Citation2004). According to scholars, employees are more inclined to cheat to achieve high goals (Schweitzer et al., Citation2004), and this effect has been reproduced in other experimental investigations (Cadsby et al., Citation2010; Welsh & Ordóñez, Citation2014a).

According to studies, the processes through which high goals boost performance also increase immoral behavior, creating a quandary in terms of effectually motivating performance while concurrently encouraging performance-directed unethical behavior. This problem is reflected in a growing debate in the literature between behavioral ethics specialists and goal-setting theorists, with data signifying that when creating goals for employees, managers must choose between performance and ethics (Welsh et al., Citation2019). A substantial correlation between HPG and unethical behavior has been suggested in various studies (Welsh & Ordóñez, Citation2014b; Welsh, et al., Citation2020; Niven & Healy, Citation2016; Ordóñez & Welsh, Citation2015). Too much pressure and stress on accomplishing goals, according to the scholar, might lead to unethical behaviors (Dockterman & Weber, Citation2017). Employees in many firms are under pressure to improve their performance to achieve lofty goals, and failing to do so can result in serious consequences such as firing (Gutnick et al., Citation2012). As a result, these effects jeopardize employees and increase their stress levels. Scholars agree that high-performance goals are stressful and can compel the employee to engage in questionable activities to achieve them (Welsh, et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, these researchers claimed that when employees are presented with demanding goals and question “if they can achieve them”? HPG can contribute to an unpleasant state of ambiguity and dissatisfaction, which can have detrimental consequences. Scholars found limited focus, suppressed learning, erosion of corporate culture, one-sided risk preferences, lower intrinsic motivation, and an increase in unethical behavior as the systemic side consequences of HPGs (Ordonez et al., Citation2009). HPGs are stressful, according to researchers, and as a result, employees may engage in an unethical activity (Welsh, et al., Citation2020; Ordóñez & Welsh, Citation2015). Scholars have found that stressful situations have an impact on leaders’ ethical behavior and their ability to recognize ethical challenges (Selart & Johansen, Citation2011). Furthermore, the ethical decision-making of leaders is influenced by organizational variables. In organizations, stress and ethical dilemma coexist because a leader in a difficult position is frequently confronted with an ethical choice (Mohr & Wolfram, Citation2010). Furthermore, the manager may be faced with changing goals and new responsibilities before completing existing work, putting strain and stress on the management. Similarly, empirical research has proven that leaders experience difficult and taxing work schedules (Ganster, Citation2005; Hambrick et al., Citation2005). Individuals in modern firms must cope with complex business ethics, and job stress has an impact on moral behavior. The current study, based on the transactional model of stress and coping, reveals that supervisors use expediency to deal with the stress of HPGs. Thus it is hypothesized

H1

High-performance goals have a significant and positive effect on supervisor expediency

2.2. Supervisor BLM as a moderator

BLM is one-dimensional thinking that focuses on the most critical priority at the cost of others (Greenbaum et al., Citation2012). Supervisor BLM has received a lot of attention in recent years, but research on leaders’ bottom-line mindset is still in its early stages (Greenbaum et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, as evidenced by scandals across industries, important decision-makers may be concerned with safeguarding the bottom line while ignoring competing goals such as ethics. The bottom-line attitude has been shown to be maladaptive in research. According to scholars, the bottom line becomes problematic when an employee develops a game-like mentality, where the only way to win a game is to secure a bottom line (Bonner et al., Citation2017). Researchers emphasized that supervisors with high BLM are more probable to bend ethical standards or rules to achieve bottom-line objectives while ignoring the negative consequences of such unethical behavior on individual and organizational performance (Zhan & Liu, Citation2021a). Researchers believe that supervisors’ actions should be influenced by their actual BLM. According to Farasat et al. (Citation2020), BLM tends to increase workaholism in employees, which leads to workplace dishonesty. In today’s competitive atmosphere, managers frequently use bottom-line targets to inspire staff (Babalola et al., Citation2020). In pursuit of bottom-line goals, a supervisor with a high BLM overlooks the means and tactics employed to attain those goals, even if they are unethical (Mawritz et al., Citation2017). SBLM is a negative and dysfunctional mentality that is triggered by emotional exhaustion (Rice & Reed, Citation2021). This emotional exhaustion could be caused by the organization’s high-performance goals, which have been linked to anxiety and emotional exhaustion in prior studies (Welsh, et al., Citation2020). Zhang et al. (Citation2021) investigated the association between SBLM and unethical pro-organization behavior and found a positive correlation. As a result, it may be claimed that the bottom-line mentality of a supervisor is stressful since it is hard and demanding and that to deal with, expeditious behavior is evoked. According to the transaction model of stress and coping, supervisors demonstrate expeditious conduct to cope with stress related to their personal BLM and high-performance goals. SBLM can be utilized as a moderator in investigating the behavioral response to workplace stressors in this vein. Zhan and Liu (Citation2021b) underlined that the attitude, personality, and preferences of a leader have an impact on his or her actions or conduct in the workplace. Thus it is hypothesized

H2

Supervisor bottom-line mentality moderates the relationship between high-performance goals and supervisor expediency such that the relationship is stronger when SBLM is high.

Based on the above literature review and hypotheses, the conceptual framework is derived and presented in Figure .

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and procedures

Full-time employees in private healthcare participated in this survey. The research team first contacted senior management or the head of the human resources department to notify them of the research’s substance, purpose, and methodology. When the hospital management agreed to be surveyed, a day and time were set for data collection. Employees were asked to rate two variables: supervisor BLM and supervisor expediency, whereas supervisory personnel were asked to rate high-performance goals. Employees and supervisors are both included in this study, and a four-digit code was assigned to the questionnaire for tracking and forming dyads. Initially, 850 self-administrated questionnaires on supervisor expediency and supervisor bottom-line mentality were distributed, 631 focal employees responded to the questionnaires, and in parallel 850 questionnaires were distributed to supervisors of focal employees on HPGs and only 602 supervisors responded. The responses created usable data from 591 supervisor-subordinate dyads. The response rate was 69 percent. Focal employees were 58.2% female had an average age of 33.27 years and an average organizational tenure of 4.48 years. Supervisors were 44% female and had an average age of 43.92 years and an average organizational tenure of 14.72 years.

3.2. Measures

Scales for data collection were adapted from previous studies demonstrating reliability. Following are the details about scales.

3.3. Supervisor expediency

Greenbaum et al. (Citation2018) established a four-item scale that was used to assess data for supervisor expediency. Employees rated their supervisor's expedient behavior by answering the questions like, “To what extent does your boss engage in the following behaviors?” “Cuts corners to accomplish work assignment more quickly,” Scale ranging from 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally, 4 = sometimes, 5 = frequently, 6 = usually, and 7 = all the time.

3.4. High-performance goals

High-performance goals were measured with four items developed by Welsh, et al., (Citation2020). The sample items include “My organization has set challenging performance goals” and “My organization has selected lofty performance goals”. Employees responded to these items on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

3.5. Supervisor bottom-line mentality

Four item scale by Greenbaum et al. (Citation2012) was used to measure supervisor bottom-line mentality. Employees rated these items; an example of an item is “only cares about the business” (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

3.6. Data analysis tools

The demographic features of respondents were determined by entering data collected from sample respondents into SPSS. Smart PLS software was also utilized in the analysis; it assisted in determining the measurement model’s reliability and validity, as well as evaluating the structural model to test the hypotheses. In comparison to covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM)., partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) has seen a lot of application in recent years PLS-SEM is becoming more common in social sciences (Hair et al., Citation2021).

4. Results

The factor loading of construct items, the average variance extracted (AVE) values, and composite reliability are presented in Table . The factor loading of all of the items in Table is higher than 0.7, which is a threshold value (Hair et al., Citation2019). The composite reliability should be better than 0.7 to assure construct reliability (Gefen & Straub, Citation2005). Table shows that all composite dependability values are higher than the required threshold. AVE specifies the convergent validity, which should be more than 0.5. All of the AVE values in Table for the constructs meet the convergent reliability criterion.

Table 1. Reliability and validity

The discriminant validity of the constructs is shown in Table . The square root of AVE must be greater than the correlation among the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Table shows that the AVE square roots of all constructs are greater than the correlations between constructs. Hair et al. (Citation2021) also recommended evaluating discriminant validity using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), which should be less than 0.90 (Henseler et al., Citation2015) Table shows that all of the HTMT values are less than the threshold value.

Table 2. Discriminant validity

Table depicts the model’s goodness of fit in terms of R2 and f2 values. According to Hair et al. (Citation2021) the R2 value spans from 0 to 1, and the R2 coefficient of determination for primary data should be greater than 0.26. Cohen (Citation1988) established an effect size (f2) guideline, with values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicating small, medium, and high impact sizes, respectively. Furthermore, a score of less than 0.02 indicates that there is no effect size. With reference to Table R2 value is 0.422 which is greater than 0.26. Moreover, the high-performance goals effect on supervisor expediency is 0.234, and the moderating effect of SBLM is 0.036 which refers to medium and small effect size respectively.

Table 3. Goodness of fit

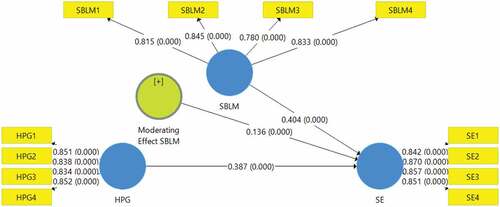

Table depicts hypothesis testing and for this very purpose, the PLS-SEM algorithm and Bootstrapping were used. Hypothesis 1 predicted the relationship between high-performance goals and supervisor expediency (β = 0.387, t = 10.677 and p = 0.000) supporting this hypothesis. Hypothesis 2 is the moderation hypothesis (β = 0.136, t = 4.167, and p = 0.000) proving the hypothesis.

Table 4. Hypothesis testing

Figure demonstrates the path analysis. It represents the measurement and structural models, which are also known as outer and inner models respectively. The factor loading in the outer model, the beta, and significance in the inner model.

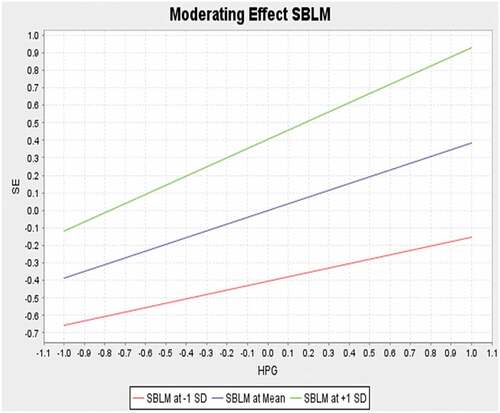

Figure depicts the graphical representation of the moderation effect of SBLM between HPG and SE. The slope shows that high- SBLM strengthens the positive relationship between HPG and SE.

5. Discussion

This research aimed to figure out what causes expediency at work, and based on the literature, high-performance goals has been identified as a predictor of expediency. Welsh, et al., (Citation2020) stressed the need of examining the impact of high-performance goals on various forms of unethical behavior, and in the current research case, the impact of high-performance goals on supervisory behavior has been examined.

The statistical results back up the hypotheses that were put forth in this study. Hypothesis 1 demonstrates the link between high-performance goals and supervisor expediency, which statistical analysis confirms. The statistical findings reasonably supported hypothesis 1. Previous research has found that high-performance goals are associated with unethical behavior (Welsh & Ordóñez, Citation2014c; Ordonez et al., Citation2009) In a recent empirical study, Welsh, et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that HPGs lead to unethical behavior via moral disengagement. As previously stated, supervisory expediency is a type of unethical behavior. Scholars believe that high-performance goals are stressful, and for that very reason, employees get involved in unethical behavior (Poortvliet & Darnon, Citation2010; Soman & Cheema, Citation2004). Hypothesis 2 proposes that the supervisor bottom-line mindset has a moderating effect on the link between high-performance goals and supervisor expediency. The findings show that a bottom-line attitude among supervisors improves the link between high-performance goals and supervisor expediency. Several empirical pieces of evidence on SBLM’s negative consequences may be found in the literature (Farasat & Azam, Citation2020; Lin et al., Citation2021; Greenbaum, Citation2009; Greenbaum et al., Citation2012; Zhang et al., Citation2020). According to past studies, a focus on the bottom line leads to a variety of unethical behaviors at the leader and employee levels, including cheating, pro-organizational unethical behavior, unethical pro-leader behavior, and employee immoral behaviors (Babalola et al., Citation2020; Bonner et al., Citation2017; Farasat et al., Citation2020).

Thus it can be deduced from the above discussion that our research results are in line with the previous research and these findings provide valuable insight to researchers and practitioners.

6. Managerial implications

Our research provides insight to practitioners that high-performance goals tend to trigger supervisor expediency. Supervisors may rationalize their expediency by claiming that their actions are modest and routine. These seemingly insignificant activities, on the other hand, can quickly escalate into a problem and cause harm (Cialdini et al., Citation2004). For instance, the WorldCom scam began with the corporation concealing little losses and culminated with the company concealing losses totaling over $12 billion (Bower & Gilson, Citation2003). To ensure the efficient and effective operation of their businesses in today’s competitive and global economy, organizations are increasingly relying on their employees to go above and beyond their responsibilities and duties, such as working longer hours or being available on behalf of their organizations (Bolino & Turnley, Citation2005). Furthermore, these businesses demand their staff to work hard, react swiftly, and deliver results in a timely and effective manner. Setting high-performance goals nowadays is common in the workplace. However, other than motivation, HPGs may lead to undesirable outcomes such as expediency. Thus monitoring of these goals is significant. Managers should weigh whether a goal aimed at extracting every ounce of motivation and performance from employees is worth the risk of unethical behavior. Key takeaway is rather than setting high targets in the 90th percentile frequently, managers may benefit from establishing a target level that correctly motivates performance without creating such a degree of “hypermotivation” that metrics outweigh ethics (Rick & Loewenstein, Citation2008).

Moreover, supervisor BLM may also lead to negative consequences. It is widely considered in the business world that company executives with high BLM will benefit their firms by increasing productivity and financial success. However, our findings suggest that, in certain instances, supervisor BLM is more probable to have the opposite impact than anticipated. The rate of unethical behavior rises under BLM’s leadership. As a result, corporations should be wary of BLM amid the executives they employ at various levels, as well as organizational rules that may encourage BLM. More specifically, when it comes to hiring, socializing, and educating supervisors and other organizational leaders, it is recommended that organizations prioritize morals, ethics, service, and synchronization over efficiency and business acumen. (Valentine et al., Citation2014). Setting goals and performance evaluation standards that are both demanding and ethical, rather than purely production-oriented, can help organizations reduce BLM among leaders.

Precisely, according to our findings, organizations and their decision makers must pay special attention to setting HPGs. Organizations should also design effective programs and initiatives to assist employees in dealing with difficult work situations.

7. Limitations and future research directions

This study has certain worth mentioning limitations, but it also points to some promising areas for future investigation. First, data collected in the present study are from the health sector, whereas the occurrence of expediency is a common workplace phenomenon and can be observed in several other sectors. Another drawback was the study’s cross-sectional design. Cross-sectional studies do not prove effect directionality and do not rule out other possible explanations. Lastly, this study includes the perspective of organization-set high-performance goalsbut not the perspective of self-set high-performance goals. Previous research has demonstrated that organizational-set and self-set high-performance goals yield different effective states (Welsh, et al., Citation2020).

Future research might be benefited from a systematic analysis of the relationship between HPGs and various types of unethical and deviant workplace practices. Individual differences may generate boundary conditions for the relationship between HPGs and supervisor expediency, which might be investigated further in future studies. Future research can also explore the mechanism through which HPGs affect supervisor expediency, such as a state of moral disengagement. Other factors such as personal factors (personality or attitude) or situational factors (climate and culture) may act as a predictor of supervisor expediency and must be investigated. Future research can also identify other moderators that can mitigate the relationship between high-performance goals and supervisor expediency such as perceived organizational support.

Finally, the current analysis gives valuable insights into why and when supervisors may participate in workplace expedient conduct. This research brings us a bit closer to understanding the phenomenon of expediency, which is still largely unknown. This study is intended to inspire others to explore this area of inquiry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ahn, J., Lee, S., & Yun, S. (2018). Leaders’ core self-evaluation, ethical leadership, and employees’ job performance: The moderating role of employees’ exchange ideology. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 457–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3030-0

- Aziz, F. (2020, July 2). Wirecard explained: The biggest European accounting fraud? Medium. https://furqanaziz.medium.com/wirecard-explained-the-biggest-european-accounting-fraud-4d2cbf8ed3f4

- Babalola, M. T., Greenbaum, R. L., Amarnani, R. K., Shoss, M. K., Deng, Y., Garba, O. A., & Guo, L. (2020). A business frame perspective on why perceptions of top management’s bottom-line mentality result in employees’ good and bad behaviors. Personnel Psychology, 73(1), 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12355

- Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2005). The personal costs of citizenship behavior: The relationship between individual initiative and role overload, job stress, and work-family conflict. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 740–748. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.740

- Bonner, J. M., Greenbaum, R. L., & Quade, M. J. (2017). Employee unethical behavior to shame as an indicator of self-image threat and exemplification as a form of self-image protection: The exacerbating role of supervisor bottom-line mentality. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(8), 1203–1221. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000222

- Bower, J., & Gilson, S. (2003). The social cost of fraud and bankruptcy. Harvard Business Review, 81(12), 20–22.

- Brown, M. E., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Ethical and unethical leadership: Exploring new avenues for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(4), 583–616. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201020439

- Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

- Cadsby, C. B., Song, F., & Tapon, F. (2010). Are you paying your employees to cheat? An experimental investigation. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2481

- Callahan, D. (2007). The cheating culture: Why more Americans are doing wrong to get ahead. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Cialdini, R. B., Petrova, P. K., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). The hidden costs of organizational dishonesty. MIT Sloan Management Review, 45(3), 67.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

- Craig, S. B., & Gustafson, S. B. (1998). Perceived leader integrity scale: An instrument for assessing employee perceptions of leader integrity. The Leadership Quarterly, 9(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(98)90001-7

- Dockterman, D., & Weber, C. (2017). Does stressing performance goals lead to too much, well, stress? Phi Delta Kappan, 98(6), 31–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721717696475

- Eissa, G. (2020). Individual initiative and burnout as antecedents of employee expediency and the moderating role of conscientiousness. Journal of Business Research, 110, 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.047

- Farasat, M., & Azam, A. (2020). Supervisor bottom-line mentality and subordinates’ unethical pro-organizational behavior. Personnel Review, 51(1), 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2020-0129

- Farasat, M., Azam, A., & Hassan, H. (2020). Supervisor bottom-line mentality, workaholism, and workplace cheating behavior: The moderating effect of employee entitlement. Ethics & Behavior, 31(8), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1835483

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Ganster, D. C. (2005). Executive job demands: Suggestions from a stress and decision-making perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30(3), 492–502. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.17293366

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01605

- Glazer, E. (2016). Wells Fargo to pay $185 million fine over account openings. The Wall Street Journal, 8. https://www.wsj.com/articles/wells-fargo-to-pay-185-million-fine-over-account-openings-1473352548

- Greenbaum, R. (2009). An examination of an antecedent and consequences of supervisor morally questionable expediency. Doctoral dissertation, University of Central Florida.

- Greenbaum, R. L., Bonner, J. M., Mawritz, M. B., Butts, M. M., & Smith, M. B. (2020). It is all about the bottom line: Group bottom-line mentality, psychological safety, and group creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(6), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2445

- Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., Bonner, J. M., Webster, B. D., & Kim, J. (2018). Supervisor expediency to employee expediency: The moderating role of leader-member exchange and the mediating role of employee unethical tolerance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(4), 525–541. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2258

- Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., & Eissa, G. (2012). Bottom-line mentality as an antecedent of social undermining and the moderating roles of core self-evaluations and conscientiousness. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025217

- Gutnick, D., Walter, F., Nijstad, B. A., & De Dreu, C. K. (2012). Creative performance under pressure: An integrative conceptual framework. Organizational Psychology Review, 2(3), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386612447626

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hambrick, D. C., Finkelstein, S., & Mooney, A. C. (2005). Executive job demands: New insights for explaining strategic decisions and leader behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 30(3), 472–491. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.17293355

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hotten, R. (2015). Volkswagen: The scandal explained. BBC News, 10, 12. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-34324772

- Isidore, C. (2015). Death toll for GM ignition switch: 124. CNN Money, 10. https://money.cnn.com/2015/09/17/news/companies/gm-recall-ignition-switch/index.html

- Jonason, P. K., & O’Connor, P. J. (2017). Cutting corners at work: An individual differences perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.045

- Joosten, A., Van Dijke, M., Van Hiel, A., & De Cremer, D. (2014). Being “in control” may make you lose control: The role of self-regulation in unethical leadership behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1686-2

- Kalshoven, K., van Dijk, H., & Boon, C. (2016). Why and when does ethical leadership evoke unethical follower behavior? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(2), 500–515. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-10-2014-0314

- Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017103

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. 11. [print.]). Springer

- Lin, Y., Yang, M., Quade, M. J., & Chen, W. (2021). Is the bottom line reached? An exploration of supervisor bottom-line mentality, team performance avoidance goal orientation and team performance. Human Relations, 75(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211002917

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2015). Breaking the rules: A historical overview of goal-setting theory. Advances in Motivation Science, 2, 99–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2015.05.001

- Mawritz, M. B., Greenbaum, R. L., Butts, M. M., & Graham, K. A. (2017). I just can’t control myself: A self-regulation perspective on the abuse of deviant employees. Academy of Management Journal, 60(4), 1482–1503. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0409

- Mohr, G., & Wolfram, H. -J. (2010). Stress among managers: The importance of dynamic tasks, predictability, and social support in unpredictable times. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018892

- Niven, K., & Healy, C. (2016). Susceptibility to the ‘Dark Side’ of goal-setting: Does moral justification influence the effect of goals on unethical behavior? Journal of Business Ethics, 137(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2545-0

- Ordonez, L. D., Schweitzer, M. E., Galinsky, A. D., & Bazerman, M. H. (2009). Goals gone wild: The systematic side effects of overprescribing goal setting. Academy of Management Perspectives, 12. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1332071

- Ordóñez, L. D., & Welsh, D. T. (2015). Immoral goals: How goal setting may lead to unethical behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.06.001

- Parks, J., Ma, L., & Gallagher, D. G. (2010). Elasticity in the ‘rules’ of the game: Exploring organizational expedience. Human Relations, 63(5), 701–730. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709355331

- Poortvliet, P. M., & Darnon, C. (2010). Toward a more social understanding of achievement goals: The interpersonal effects of mastery and performance goals. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(5), 324–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410383246

- Ren, S., Wang, Z., & Collins, N. T. (2021). The joint impact of servant leadership and team-based HRM practices on team expediency: The mediating role of team reflexivity. Personnel Review, 50(7/8), ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-07-2020-0506.

- Rice, D. B., & Reed, N. (2021). Supervisor emotional exhaustion and goal-focused leader behavior: The roles of supervisor bottom-line mentality and conscientiousness. Current Psychology, 41(12), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01349-8

- Rick, S., & Loewenstein, G. (2008). Hypermotivation: Commentary on The dishonesty of honest people. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 645–648. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.45.6.645

- Schweitzer, M. E., Ordóñez, L., & Douma, B. (2004). Goal setting as a motivator of unethical behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159591

- Selart, M., & Johansen, S. T. (2011). Ethical decision making in organizations: The role of leadership stress. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(2), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0649-0

- Soman, D., & Cheema, A. (2004). When goals are counterproductive: The effects of violation of a behavioral goal on subsequent performance. The Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1086/383423

- Treviño, L. K., Den Nieuwenboer, N. A., & Kish-Gephart, J. J. (2014). (Un) ethical behavior in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 635–660. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143745

- Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306294258

- Valentine, S., Hollingworth, D., & Eidsness, B. (2014). Ethics-related selection and reduced ethical conflict as drivers of positive work attitudes: Delivering on employees’ expectations for an ethical workplace. Personnel Review, 43(5), 692–716. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2012-0207

- Walumbwa, F. O., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. L. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.11.002

- Welsh, D. T., Baer, M. D., & Sessions, H. (2020). Hot pursuit: The affective consequences of organization-set versus self-set goals for emotional exhaustion and citizenship behavior. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(2), 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000429

- Welsh, D. T., Baer, M. D., Sessions, H., & Garud, N. (2020). Motivated to disengage: The ethical consequences of goal commitment and moral disengagement in goal setting. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(7), 663–677. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2467

- Welsh, D., Bush, J., Thiel, C., & Bonner, J. (2019). Reconceptualizing goal setting’s dark side: The ethical consequences of learning versus outcome goals. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 150, 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.11.001

- Welsh, D. T., & Ordóñez, L. D. (2014a). Conscience without cognition: The effects of subconscious priming on ethical behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3), 723–742. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.1009

- Welsh, D. T., & Ordóñez, L. D. (2014b). The dark side of consecutive high performance goals: Linking goal setting, depletion, and unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 123(2), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2013.07.006

- Welsh, D. T., & Ordóñez, L. D. (2014c). The dark side of consecutive high performance goals: Linking goal setting, depletion, and unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 123(2), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2013.07.006/

- Yglesias, M. (2019, March 29). The emerging 737 Max scandal, explained. Vox. https://www.vox.com/business-and-finance/2019/3/29/18281270/737-max-faa-scandal-explained

- Zhang, Y., He, B., Huang, Q., & Xie, J. (2020). Effects of supervisor bottom-line mentality on subordinate unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(5), 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-11-2018-0492

- Zhang, Y., Huang, Q., Chen, H., & Xie, J. (2021). The mixed blessing of supervisor bottom-line mentality: Examining the moderating role of gender. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(8), 1153–1167. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-11-2020-0491

- Zhan, X., & Liu, Y. (2021a). Impact of employee pro-organizational unethical behavior on performance evaluation rated by supervisor: A moderated mediation model of supervisor bottom-line mentality. Chinese Management Studies, 16(1), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-07-2020-0299

- Zhan, X., & Liu, Y. Impact of employee pro-organizational unethical behavior on performance evaluation rated by supervisor: A moderated mediation model of supervisor bottom-line mentality. (2021b). Chinese Management Studies, 16(1), 102–118. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-07-2020-0299/