Abstract

The existing literature has focused on the exclusive relationship between institutional logics that are perceived as competing. The current study argues that multiple logics can co-exist in a blended relationship. The purpose of this study is to shed light on such a blended relationship between the alleged competing logics through the analysis of the institutional demands prescribed for artisan product innovation. A qualitative study with 15 semi-structured in-depth interviews as the main data source was conducted in Bát Tràng, a local artisan ceramic community in Hanoi, Vietnam. This exploratory study reveals that institutional logics show the mutual intersection of some attributes that pave for the existence of the blended relationship. In other words, the mutual intersection of two logics permits the agents to traverse such a blurry boundary between these two logics without incurring institutional conflicts. This study also offers future research agenda in an established literature of institutional logics.

1. Introduction

Blindly following ancient customs and traditions doesn’t mean that the dead are alive, but that the living are dead.– Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406).

Organizational and individual behavior has been substantially studied in the management literature. The management literature has benefited from the adoption of institutional logic as the perspective that sheds more light on organizational and individual behaviors, particularly in a hybrid context (P. H. Thornton et al., Citation2012). The existing studies applying institutional logics perspectives have lent us quite a deep understanding of how organizations or individuals cope with the logic multiplicity. As defined as “the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules” (P. H. Thornton et al., Citation2012), logics help us answer the questions of why and how the actions of entities are implemented. The actions are not only dependent on the compatibility but also the centrality of logics. The former refers to the extent to which different logics can get along with each other while the latter is characterized by the embeddedness of logics in the organizational or individual practices. In a hybrid context which shows the low level of compatibility associated with a high level of centrality, actors are expected to take strategic responses that carefully reconcile such logics to reduce the likelihood for actors to face unexpected outcomes.

Further, the extant literature on the actors’ reaction to the hybridity of the context often has overlooked the intersection among components of logics because it has much focused on logics as a whole and how logics interact with each other. For example, existing studies found that market or corporate logics show contrasting demands with state or community logics (Reay & Hinings, Citation2009). Such multi-logic context can be responded with to strategies such as coupling and decoupling (Battilana & Lee, Citation2014). However, the question on whether different logics are both conflicting and synergistic has been left unanswered so far since the suggestion from the research results conducted by A. Pache and F. Santos (Citation2013) regarding the “selective coupling” strategy with which components of competing logics can be selectively coupled and imprinted on organizational actions. So, the current study will address the question of how the relationship between logics’ components can elaborate on the co-existence of logics. The authors attempt to dive more deeply into the relationship between the elements of logics rather than merely focusing on analyzing the relationship between logics as a whole.

To address the research question, Bát Tràng, an artisan ceramic community in Vietnam is an interesting case for several reasons. First, its 700-year history which is rooted in the socio-economic-historical development of Vietnam is an appropriate context for analyzing the manifestation of artisan logic. Further, the waves of technology and mass-products-based competition following the economic reform “Doi Moi” in the transition economy of Vietnam clearly introduce a new logic that permeates the business industry. The survival and thrivingness of this ceramic community are fertile ground for exploring the “How do artisan entrepreneurs balance tradition and innovation in their pursuit of growth and to what effect” by Pret and Cogan (Citation2019, p. 606).

The current study found that market logic and artisan logic are competing with relatively equal power for the influence on artisan business’ product innovation. By “blended relationship”, the authors mean that, on the one hand, some attributes from market logic and artisan logic are competing with each other by giving contrasting demands that drive the way how products are produced and how changes to products are made. On the other hand, other attributes of these logics show the synergistic effects in product innovation among artisan businesses. So, the current study identifies the signal for the existence of the mutual intersection between logics that allows actors to traverse the blurry boundary between logics without expecting negative outcomes. So, the current study extends the analysis regarding the relationship between logics by clarifying the logic behind the survival and prosperity of the selected community that has been given little attention in management and entrepreneurship literature.

2. Institutional logics as a theoretical framework

The institutional logics perspective has been fashionable in organization and management literature. The recent scholarship in this field has provided a panoramic discussion of the organizational and individual responses to multiple logics that co-exist in hybrid organizations. Originating from the analysis of Friedland and Alford (Citation1991), institutional logics has been defined as “the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality” (P. H. Thornton et al., Citation2012). Such a set of “formal and informal rules of action” (P. Thornton & Ocasio, Citation1999, p. 804) are distinctive in terms of the demands they require actors at all levels to respond to (Reay & Hinings, Citation2009; Scott, Citation2008).

As a meta-theory, the institutional logics perspective has some assumptions. The first assumption is on “embedded agency” (Battilana, Citation2006). That means that actions, beliefs, and values at different levels of individual and organization are embedded in the institutional context where dominant institutional logics will be more likely to take control (Granovetter, Citation1985; P. H. Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008). This assumption helps differentiate institutional logics perspective from neoclassical economics that emphasizes the rationality-based decision of individuals or firms. In a multiple-logic context, individuals or corporates may not be rational as described in the traditional economics with which they make decision based on the reasoning that they will put effort to achieve the optimal choice of profit or utility based on the consideration of cost and benefit. In contrast, the institutional logics perspective insists that institutionalized environments where multiple logics co-exist will drive actors away from rational choice. If one institutional logic predominates others, actors will be more likely to try to react to it over the other peripheral ones. This assumption emphasizes the way actors in an institutionalized context identify, consciously react to a set of ethos, values or norms and then become partly autonomous in such context (Friedland & Alford, Citation1991).

Second, another assumption of institutional logics perspective is on its premise. The institutional logics perspective assumes that institutional orders reflect two features of material and non-material premises. This assumption suggests that institutional orders are interdependent systems where both cultural and material practices and rules of the game interact with each other and collectively condition actions and ways of thinking among actors. By partly denying the core assumption of rational choice in the neoclassical economics approach, Granovetter (Citation1985, p. 504) demonstrated that most of the behaviors are “closely embedded in networks of interpersonal relations and that such an argument avoids the extremes of under- and over-socialized views of human action”. He further added that the level of embeddedness of human (economic) action is found to be low in non-market societies. It is hard to find a context where only one logic exists, and continues to live long over time without any contradictions from other logics that newly enter such context. This assumption brings back the role of cultural aspects in institutional scholarship. Although culture-based factors constrain the actions in practice, they are manifested in material practices.

Third, historical contingency is an important assumption in institutional logics perspective. The institutional logics perspective emphasizes the role of a historical context where socio-political events occur. The nature of each context is determined by a large number of key events ranging from economic, social to political aspects. This assumption paves for the broader space of changes in institutions when institutional logics change over time varying according to historical contexts. That means that institutions may be subject to transformation when practices and institutional logics change. As examined in P. Thornton’s (Citation2004) book on the publishing field at a higher educational level, the shift from editorial logic that emphasizes the nexus between the editor and the authors and sale increase to the market logic that focuses on business growth, profit increase, and competition causes significant changes in executive succession. P. Thornton (Citation2004, p. 83) wrote that “when, whether and how leaders deploy their power to affect succession in organizations is conditional on the prevailing institutional logic in an industry”. Ruef and Scott’s (Citation1998) study found that the meaning of medical care and particularly hospitals experienced a gradual transformation since the chance for survival became a critical issue concerning the hospital. Such requirements of surrounding environments led to the modification of managerial practices that were later conditioned by market forces.

The above framework in Figure is developed from the conceptualization of logic multiplicity by Besharov and Smith (Citation2014). They conceptualize four forms of organizations when they face multiple logics with the combination of the compatibility and centrality between logics. The framework predicts that the “Contested” form which is a combination of a high degree of centrality and a low degree of compatibility will lead an organization to the risk of conflicts within internal organizations. An unexpected outcome of such lasting conflicts is the low firm performance or high turnover rate. “Estranged” form that is made from the competition between logics in a situation in which one logic dominates just makes an organization face moderate conflicts in its internal system. In contrast, “Aligned” and “Dominant” forms are more comfortable situations for an organization because logics multiplicity does not create a conundrum for it with multidirectional demands or instructions. These authors suggest that further research that can analyze how logics multiplicity is embodied within organizations will expand the proposed framework and thus make a theoretical contribution.

Like other previous academic works, the framework proposed by Besharov and Smith (Citation2014) takes one side to analyze logic multiplicity. Logics in the existing literature are supposed to be either conflicting or complementary. It limits our understanding of the varied nature of logics multiplicity. A. -C. Pache and F. Santos (Citation2013) and then Gümüsay et al. (Citation2020) inform us of the complex variation of the relationship between logics. Accordingly, multiple logics’ components can be selectively coupled while other components are still decoupled or portrayed in an “elastic hybridity”. Unfortunately, the existing body of literature has not well responded to their suggestion. Instead, they have put much emphasis on how organizations respond to multiple logics. As a consequence, the diversity and nature of organizational responses are somehow the myth because we miss the clear link between the varied nature of the relationship between logics that shapes what will be done by organizations.

3. Literature review on institutional logics and artisan business

In addition to other factors affecting organizational and individual behaviors, the co-existence of institutional logics put actors in a dilemma in their decision-making process, particularly when logics are competing. The consistency between logics in the way they give guidance for actions is conceptualized by Besharov and Smith (Citation2014). The compatibility between logics refers to “the extent to which the instantiations of logics imply consistent and reinforcing organizational actions” (Besharov & Smith, Citation2014, p. 9). That means that the level of compatibility between logics will be lower when institutional logics prescribe different directions for actions. The common logics revealed in the existing literature such as state logic, community logic, market logic, family logic, and profession logic (P. H. Thornton et al., Citation2012) show varied relationships. On the one hand, logics can get along with each other and thus give little chance to conflicting actions (Mars & Lounsbury, Citation2009) while many logics signal the competing demands for organizations and individuals. That is when a field or an organization has “two or more strong, competing or conflicting belief systems” (Scott, Citation1994, p. 211). For example, much research in many fields shows that actors in hybrid organizations face different suggestions for their practices regarding micro-finance (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010), social services (A. Pache & F. Santos, Citation2013; Binder, Citation2007), health careKitchener, Citation2002; McVey et al., Citation2020), justice (Valentini, Citation2017), education publishing (P. Thornton, Citation2002), gig economy and innovation (Browder et al., Citation2022; Frenken et al., Citation2020; Genin et al., Citation2020), and artisanship (Lindbergh & Schwartz, Citation2021; Solomon & Mathias, Citation2020). More recently, Gümüsay et al. (Citation2020) have found the “elastic hybridity” that is presented in “polysemy” and “polyphony” in the way an Islamic bank copes with market logic and community logics.

Organizational or individual behaviors in a multi-logic context may be difficult to anticipate because different logics have different comparative powers that partly determine the centrality that is defined as “as the degree to which multiple logics are each treated as equally valid and relevant to organizational functioning” (Besharov & Smith, Citation2014, p. 12). When one logic is dominant, then another will be peripheral to the responses of organizations or individuals. In contrast, when centrality degree is high with competing logics, actors will try to adopt strategic responses to avoid any negative outcomes resulting from deviant behaviors (A. Pache & Santos, Citation2010), e.g. decline in firm performance (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010; Tracey et al., Citation2011). For instance, Reay and Hinings (Citation2009) found that the introduction of corporate logic in a health-care system informs the centrality among logics that creates logic hybridity. Although medical staff conforms to profession logic (medical professionalism) while the government and managerial staff abide by corporate logic (business-like), the business-like logic gradually dominates and permeates the health-care system. As A. Pache and F. Santos (Citation2013) conceptualized, individuals in hybrid organizations will play the role as “hybridizers” who combine two competing logics if they are identified with these two logics and these logics are of comparable strength. Further, A. Pache and F. Santos (Citation2013) propose five types of individual responses to competing logics based on the awareness and information they have about the institutional context including ignorance, compliance, defiance, combination, and compartmentalization. These authors came to conclude that entrepreneurs are the “multicultural” hybridizers who contribute to innovation and institutional change.

Organization and management literature has recently turned its attention to artisan entrepreneurship (Pret & Cogan, Citation2019), an interdisciplinary field that is characterized by the existence of multiple logics. First, market logic that is prevalent among private firms now permeates the artisanship in the making of business-like forms. Artisan entrepreneurs “who emphasize manual production over mass-production, independence over conglomeration, local community over scale, and value creation over profit maximization” (Solomon & Mathias, Citation2020, p. 1) struggle with the question of “who we are” with which they need to adopt a market rule in the business (Kellogg, Citation2009; Lindbergh & Schwartz, Citation2021). Artisan firms may introduce process innovation in which technology has more roles to play in making artisan products or semi-artisan products (Campana et al., Citation2016; Kabwete et al., Citation2019). They do so to satisfy their customers’ tastes and needs in pursuit of firm growth (Aakko, Citation2018; Pret & Cogan, Citation2019).

In contrast, much research highlights the artisan logic existing in the artisanship field and firms in which it informs actors in such context of the rules that differentiate artisan products from mass-produced products. Terrio (Citation1996, p. 77) concluded that “The very persistence of skilled craftsmen and family modes of entrepreneurship in these [post-industrial] economies means they can be absorbed within and designated as unique manifestations of a unified national culture.” Artisanship is unique because it is “the application of skill and material-based knowledge to relatively small-scale production” (Adamson, Citation2010, p. 3). Artisan products portray social-historical and aesthetic values (Twigger Holroyd et al., Citation2017) that may reduce the actions of artisan firms or firm owners to the situation in which they partly deny profit-making opportunities (Humphreys & Carpenter, Citation2018). Thus, artisan firms face the dilemma between preserving tradition or introducing changes to past legacies in pursuit of material benefits (Lindbergh & Schwartz, Citation2021).

4. Methodology

4.1. Research setting

To study the “social world”, interpretivism and positivism are two well-known paradigms with different ontologies, epistomologies, and the research aim. With positivism approach, social researchers attempt to study social phenomenon that is socially constructed in a relatively direct way with the assumption that they can be independent of the things they observe and analyze (Schaffer, Citation2016). Conversely, interpretivism demands the different ways that researchers see and study the world. Accordingly, researchers in social science tend to observe and perceive the shared meanings of the “unreal” social entities that are socially constructed and embedded in an institutionalized cultural context (Hawkesworth, Citation2014). Collins (Citation2019) describes interpretivism as “associated with the philosophical position of idealism, and is used to group diverse approaches, including social constructivism, phenomenology, and hermeneutics; approaches that reject the objectivist view that meaning resides within the world independently of consciousness”. A qualitative method with an interpretive approach has been applied in this study. The interpretive approach will allow researchers to get more insights from the practical data and events from the view of informants (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015; Van Maanen, Citation2011). Another focus of this study is on describing the direction driven by different logics to find out the subtle meaning of the relationship between logics.

Bát Tràng has been chosen as the research site of the present study because it provides an appropriate and interesting context for analyzing competing logics. Located in Hanoi, the capital city of Vietnam, Bát Tràng has been a fertile ground for the making and development of ceramic production since the fourteenth century (Bui et al., Citation2013). As a handicraft subindustry, ceramic production in Bát Tràng has witnessed a lot of adversities in its historical development. Having started in the fourteenth century, it mainly served the demand of royal members through Vietnamese dynasties (Phan et al., Citation1995). Craft production only experienced gradual changes over the 600 years (Phan et al., Citation1995) before it encountered the serious challenge from mass production (Fanchette & Stedman, Citation2009) and customers’ changing needs (Do, Citation1989). Economic reform “Doi Moi” since 1986 in Vietnam has opened the avenue for private business, including craft ceramic production. Rapid socio-economic development in Hanoi has created not only business opportunities but also a dilemma for ceramic production. On the one hand, market expansion that went along with the competition of alternative mass-produced products (particularly Chinese goods), tourism-driven demands, and proliferation of local production brought considerable economic benefits to local artisanship producers (Bui et al., Citation2013; Fanchette & Stedman, Citation2009). On the other hand, the “rules of the game” guiding traditional craft production that was passed on over several hundred years in this local artisan community have still been in effect and embedded in traditional cultural events, documents, and historical buildings (e.g. village convention, annual local festival, family trees, village temple of literature). Therefore, artisanship production may be subject to the tension between the demands resulting from the market and the “rules of the game” anchored to traditional values.

4.2. Data collection

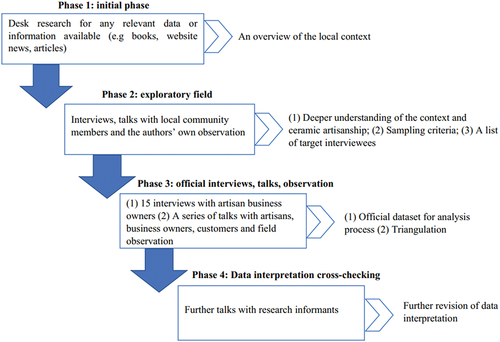

The in-brief entire data collection process is visualized through a diagram below. Then, a more detailed description of the data collection is provided below in Figure .

We were aware that analysis of logics in a cultural context like the artisanship community, Bát Tràng, in my study demands a careful data collection process. The research design introduced by A. Pache and F. Santos (Citation2013) provides us with a useful initial recommendation for my data collection. The authors broke data collection into multiple phases. During the initial phase of data collection, desk research was carried out to gather any documents or data available to gain an overview and background knowledge on the socio-economic and historical development of the artisanship community, focusing on the ceramic community, Bát Tràng, regulations on craft village and artisan certificate. The research site is a large ceramic-making community that is a large region for thousands of family businesses, micro-small and medium-sized enterprises and local citizens. The life and business of local people are intertwined in the way Bát Tràng is home to local life, ceramic production and business, craft ceramic exhibitions and reserve.

After phase 1, I continued with a series of interviews and talks with a local couple who are an artist cum artisan (Hoang) and an architect (Van Anh). I brought what I learned, e.g. background knowledge about the artisanship community, to the interview and discussion with these informants. I traveled back and forth between October 2021 to February 2022 to Bát Tràng for many interviews, informal talks, and field notes. This second stage offered me a deeper understanding of social and economic activities in the research site from the insider’s view. The data collection was continued with a further connection with a community leader, Tuc Dinh Dang, who had been a commune leader for around 20 years and played a key role as a host for hundreds of socio-economic and policy events in the local community. Tuc first helped me clarify the confusing points and further provided me with a comprehensive background regarding social and business activities of the local context over a long period, particularly focusing on the key changes in artisanship and local people’s socio-economic life. Then, he kept sharing some key written documents that are unaccessible, e.g. Bát Tràng village convention and some not-for-sale books that describe the comprehensive background information about key socio-economic aspects of my research site. Drawing on the rapport with the local influencers (Tuc, Hoang, and Van Anh), the data collection is eased and continued with the connection with the target interviewees. We discussed with each other scanning the list of artisans and artisan business owners to find the candidates who are qualified for the current study’s interviews based on several core selection criteria regarding (1) being awarded at least one artisan certificate, (2) running the business in Bát Tràng and (3) being born and raised in Bát Tràng. All of these three criteria will ensure the suitability of research informants.

Phase 3 was conducted with a series of 15 semi-structured in-depth interviews and fieldwork with notes and observation during 5 months. The current study adopted semi-structured in-depth interviews as a main data collection tool because it allows the author to further discover new knowledge based on the development of the interviews. Not to mention ice-breaking questions and the ones on personal details, the interview guide (see further in the appendix) was initially developed with 25 questions focusing on identifying logics, logics’ demands, perception of informants on logics and their demands, the changes of products over time. For example, interviewees were asked: What drives the changes in your products? Do such changes come from the market? Could you please clarify any boundary for such changes and if there is any boundary for the changes, why? From the view of a business owner, what do you think you should do? As an artisan, what do you pursue?

This data collection strategy yielded fruitful outcomes. For example, a clue revealed from the interview 4 encouraged the author to further explore more about the underlying logic behind the artisan product strategy that couples two competing logics. Data collection from interviews as a primary data source was stopped when no new theoretical concept emerged (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967; Glaser, Citation1992). Further, to verify the qualitative data, triangulation was applied to offer a more comprehensive understanding of institutional logics. In addition to data collected from 15 in-depth interviews, several informal talks with both local citizens who are not either artisans or business owners and customers who ever purchased craft ceramics made in Bát Tràng. Such additional data would not only give further information for the study but also help cross-check some data collected from interviews (e.g. interviewees reported that their artisan products experienced changes varying according to customers’ taste. They also stated artisan products are part of symbolic value for the local community).

To respond to the ethical issue, the authors clearly explained the purpose of the current study for research informants. The authors also promised them to keep their identities confidential. Further, they asked the interviewees if they have any concerns when joining the interviews (e.g., any harm to the personal brand, business growth) at the outset of interviews and talks before they verbally agreed on participating in the current study. The authors of the current study also got back to Bát Tràng to have more discussions with interviewees during data analysis that was being carried out. The purpose of this approach was to reduce any misinterpretation of meanings or subtle meanings of qualitative data.

4.3. Data analysis

Qualitatively analyzing institutional logics has been used in qualitative studies. The current study applies the “pattern-matching” technique to qualitatively capture the institutional logics (Reay & Jones, Citation2016). The pattern-matching technique has been used in several influential studies in the literature on institutional logics, e.g. P. Thornton and Ocasio (Citation1999), P. H. Thornton et al. (Citation2012), Goodrick and Reay (Citation2011). This technique requires researchers to compare practical data to the ideal-type logics to identify institutional logics (Reay & Jones, Citation2016). The descriptions of attributes or characteristics of institutional logics (market logic and profession logic) are borrowed from studies by P. H. Thornton and Ocasio (Citation2008) and Goodrick and Reay (Citation2011). Then, the author of the current study would match the practical data collected from interviews, talks, historical documents, and government policies with each of the attributes of these two logics. As suggested by Goodrick and Reay (Citation2011), an evaluation of the closeness between practical data and ideal-type logics would be carried out to reduce any mismatch. The scale for such evaluation will range from 1 to 5 reflecting the increasing level of closeness.

Data analysis of this study also adopted the back-translation technique to avoid any misrepresentation of language because the Vietnamese language was used for all interviews and talks. First, Vietnamese language was used in the qualitative coding process. Then, Vietnamese-written texts would be translated into English to match the ideal-type logics. A parallel reverse process was also completed. English-written presentation of the attributes/characteristics of ideal-type logics was translated into Vietnamese to help matching process. Next, after matching process, the results will be translated back into English. These two parallel processes were able to minimize the translation problems that might distort the genuineness of the coding process.

5. Results on market logic, artisan logic, and blended relationship

5.1. Matching process between practical data and ideal-type logics

5.1.1. Learning stage of logics

The co-existence of market logic and artisan logic is clearly stated in the practical data collected from in-depth interviews, government and historical documents, and informal talks. The matching process produces a high level of matching between practical data with the ideal-type institutional logics. Before matching practical data with the ideal-type institutional logics, the following paragraphs will present the learning stage of the pattern-matching stage by capturing the sense and meaning of the logics available. Interviews and talks with Tuc, Hoang, and Van Anh have benefited the first stage of the pattern-matching process.

Tuc, Hoang, and Van Anh stated that thanks to the increasing production, Bát Tràng has been a home for thousands of paid labors originating from elsewhere. These labors have been provided a series of technical training sessions at different levels in craftwork. Moreover, Tuc also emphasized that Bát Tràng has been experiencing a gradual shift from purely business to a combination between ceramic business and ceramic-driven local tourism. Such a shift is the result of government policy direction and market demand. Government and local authorities have explored and then focused on the potential of the researched community tourism. In recent years, they implemented many supportive programs for the development of the local community tourism. As a result, local firms and family businesses follow the call from the government policies and then change the direction in a way that they put their focus on tourism that is anchored to the symbolic meaning of local community products. The development of community-based tourism in Bát Tràng is also one of the reasons for promoting changes in the production and products of Bát Tràng. Previously, consumers of Bát Tràng’s products were mainly in other localities, but in recent years, the increase in the number of visitors to Bát Tràng has resulted from the pursuit of the personal enjoyment of local features. Consequently, visitors flocked to Bát Tràng for purchasing activities and localized distinctive characteristics.

Another point worth consideration, the perception of local artisans and citizens is divided. Part of them is open to whatever is new in the craft business while the remaining part supports the adoption of a new method, ceramic input, or technology. All of these local informants warned that the ones who support the newness do not necessarily clearly express that view in the public sphere. They may carefully show their idea to the public because of fearing the unexpected reactions from those whose mind is anchored to oldness. The informants emphasized that artisans in Giang Cao village tend to be more open to innovations than their counterparts in Bát Tràng village.

Although Bát Tràng village and Giang Cao village are two villages of Bát Tràng commune, but if you want to see traditional craft skills and pure artisan ceramic products, just come to Bát Tràng village. If you want to see something new, you can see it in Giang Cao village.

On the one hand, the local artisans try not to show discrimination against the perception of artisan business, products, and skills from both sides. On the other hand, there still exists a fact based on the insiders’ view like Hoang, Van Anh, and Tuc that, although changes are a must and the changed direction in artisanship has been prevalent, part of the researched community shows the opposing view on the newness.

5.1.2. Matching stage of logics

5.1.2.1. Market logic in artisan firms

Table below presents the attributes of Market logic. Economic reform “Doi Moi” since 1986 has been a turning point that marked the transition from a centrally planned economy to a market-based economy in Vietnam. Along with such a transition, the dissolution of state cooperatives in most business fields gave rise to the private and family business. The introduction of technology in the local artisan community sparked the severe competition facing artisan production. Running a business in the contemporary economy of Vietnam, particularly in the area of the ceramics-producing community, is perceived as the “battlefield” because of the high competition resulting from a large number of local competitors and Chinese technology-driven ceramics. All of the current research’s informants are fully aware that their firm struggles the survival in a competitive business context. In such context, craft production is portrayed as a business-like form that pays attention to market signals, e.g. competitors and customers. That is considered the source of identity for craft production. To survive such severe competition, on the one hand, artisan businesses need to be navigated by the market position that explicitly refers to competitive advantages. On the other hand, artisan businesses are oriented by customers’ tastes. For example, the products need to show their utility and satisfy the customers’ needs. In other words, firm performance will be decided by the taste and the need of customers. At the core of serving customers’ needs are product price and values that are largely affected by technology-based productivity growth. Thus, technology can be intentionally engaged in many production phases to make changes to products.

Table 1. Attributes of market logic and artisan logic

5.1.2.2. Artisan logic

Table below presents attributes of Artisan logic. The local artisan ceramic community has been long established since the fourteenth century. It was when craft products were merely produced with manual labor and craft skills. The changes in ceramics did occur but slowly over several hundred years until the twentieth century. Craftwork has its own “rules of the game” in which the manual labor and craft skills through the hand of artisans will play a strongly decisive role in craft production. Artisans themselves become a part of such a process. Informants of this research reported that they put their passion and love into craft production which makes craft products unique and aesthetically beautiful. Traditional values in craft production are passed on from generation to generation within the local community. They are manifested in annual festivals that are considered a way to honor their craft ancestors. The view of Vietnamese government is also for preservation of craft skills and craftwork and also make them better adapt to the contemporary era. Local authority of Hanoi issued a city program for preservation and development of craft ceramics production. Further, the current policies set a number of criteria for those who want to be certified as artisan. For example, a meritorious artisan must be doing job at least 30 years, show the significant contribution to the profession through provision of training for at least 50 future artisans, etc. Therefore, the craft products not merely represent the symbolic values of the community, but also the personal reputation of artisans.

5.2. Institutional demands toward craft products

Institutional logics have different demands that guide the actors’ behaviors. This study provides further evidence in support of market logic’s demand for innovation in craft products. In contrast, artisan logic shows the hybrid demands for product innovation.

5.2.1. Institutional demands from market logic for craft production

As presented in Table , market logic requires that the price of a product must be competitive. In so doing, it allows the engagement of technology in production phases as the replacement for manual labors. As a result, it not only causes changes in the products, mainly in the design, thickness, and color of products but also allows producers to introduce new products fast. Market logic emphasizes the role of new products as a competition tool for firms. It entails the quick reaction of craft producers to the launching of new products by competitors. Unlike artisan logic’s demand that considers the uniqueness of craft products as a competitive advantage, market logic’s demand urges craft producers to boost the speed of product innovation to take action as the first movers. Further, the material utility of products is a must. Craft producers are expected to ensure the utility of products that is guided by customers’ taste. Technology can be a useful tool to make positive changes in products with a higher level of technical precision that was never achieved with traditional craft skills.

Table 2. Institutional demands from market logic for craft production

5.2.2. Institutional demands of artisan logic

In this study, artisan logic shows the hybrid institutional demands toward product innovation (see further in Table ). On the one hand, it requires that manual labor must be a main source that creates the values of products. At the heart of craft products is the manual labor of artisans. To help create craft products’ values, artisans are aware that traditional craft skills should be transferred over generations. Products must own the “spirit” inside. It is embedded inside craft products. The “spirit” of products is the “uniqueness” that differentiates it from other mass products. The ambivalence toward product innovation is revealed through the artisan logic. To warrant the uniqueness of craft products, the artisan must take control over production phases, particularly the main phases that help differentiate craft products. The value of craft products can be maintained as long as artisans play a decisive role in making craft products. Further, the adoption of technology at a certain level can upgrade the aesthetics and precision in craft production.

Table 3. Institutional demands from artisan logic for craft production

5.3. The view of local citizens and customers toward artisan ceramic products

First, Table presents the points of view of local citizens who are not artisans or business owners in the ceramic field. Their view and observation will shed light on the existence of logics, the cross-checking method for the data collected from qualitative semi-structured interviews and the external expectation or pressures for artisan business.

Table 4. Perception of local citizens and customers on artisanship

Generally, there exist some external pressures from the general public and the customers facing artisan business and production. The perception of customers and the public embodies the institutional constituents and thus the external pressures that partly shape how artisan firms perform their products. The ambiguity embedded in these external stakeholders fosters diversity in the way firm owners respond to logics. Indeed, local citizens and customers show both “for and against” toward changes in products. On the one hand, they support products’ changes with the belief that no one can stand outside the “game”. On the other hand, they urge artisans to retain heritage skills at all costs.

When the authors of this research conducted informal talks with local citizens and customers, they responded to his question immediately without reluctance. They clearly expressed their proud feeling about the brand “Bát Tràng” and were eager to talk about it. We can see that the view of local citizens in the current research represents a fact that they feel secure with the familiar products because they consider the ancient values as pride of their community. In contrast, the transformation still occurs when the socioeconomic context changes. Thus, they also feel comfortable with the changes at certain levels. Similarly, customers are not conservatively faithful to old values. They accept changes as a necessity along with the traditional values conservation.

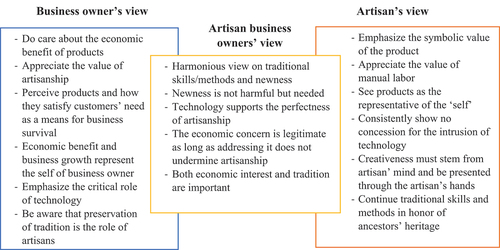

5.4. The view of local artisans and business owners toward artisan ceramic products

Table reveals the contrasting view between the artisan and business owner. In the current study, only one “pure” artisan and one business owner who is not an artisan are recruited. Data collected from them clarify logics and identities related to the research topic. The artisan in the current study shows a firm view on artisan products. For him, Duc, artisan products are the ones that cannot be equated with mass-produced ones or the ones with the support of technology. From his point of view, artisans not only need to take full control over the production of artisan products but also directly get involved in making those with their hands. By participating directly in the production process, artisans can sense their “self”. We see that artisans, who are imbued with the artisan logic and stay away from business logic, obviously show their passion for tradition and symbolic values based on the identification of craft skills transfer over the next generations as their mission. The firm and partly “conservative” view against the change keeps them away from business growth. In contrast, the journey of the business owner who is not either rooted in the local community or being an artisan is different. Although the business owner who is recruited in this research is aware of and appreciates the value of artisan ceramic, he only maintains the things that cannot be substituted by technology. The symbolic value of artisan products is emphasized in his words, but economic concerns are just his firm’s priority.

Table 5. Perception of artisans and business owners on artisanship

The comparison of the view between two actors who show different identities returns an important result. Artisans and business owners represent very different views on what ceramic should be in the contemporary society. The views of these two actors are located in the two extremes. In other words, the opposing views from these two extremes help us better understand the views in between of these two.

We can see in Figure that those artisan business owners portray a tolerant view that illustrates a reconciliation between the two sides. On the one hand, artisan business owners clearly express one of the logics for their business is the practice, value, and beauty of craftwork. There is a reminder here that all artisan business owners as the current research informants are those who started first with the journey to becoming an artisan. A long history of engagement with craftwork has implanted in them a firmly clear expectation to become an artisan. Scaling-up of their business and the transition of their role from an artisan to the one who runs the business put them face a tension that is made from two “rules”. The presence of the tolerant view does not necessarily mean the disruption of logics. Instead, it helps us better understand how artisan businesses can respond to different demands of logics.

6. Discussion and conclusion

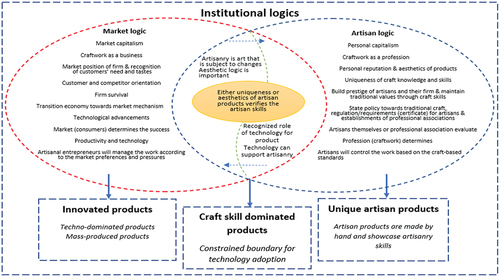

The current qualitative study identifies a blurry boundary in the mutual intersection between market logic and artisan logic. The mutual intersection between logics that is created by the compatible attributes of logics enables actors to have a more flexible strategy that is expected to satisfy both institutional logics’ demands. This research result showcases the diversity in organizational behavior among firms encountering multiple logics. Further, this study also provides further evidence that supports the compatibility of logics. However, it goes further by discovering the blended relationship that is characterized by the co-existence of incompatible and compatible attributes. The incompatible attributes prescribing different demands guide product innovation in different directions. The artisan logic demands that firms should maintain the introduction of traditional products buiding on craft skills, while market logic requires that firms can launch innovative products based on technology. The mutual intersection with a blurry boundary offers a new approach to the analysis of product innovation in an institutional context of the artisan community.

Drawing on the existing literature on institutional logics, the matching process between practical data of local artisan ceramic production with ideal-type market logic and artisan logic first provides a detailed presentation of attributes of logics. This study finds a blurry boundary between market logic and artisan logic that is made from the mutual intersection between logics. That means that not all attributes of these two logics are conflicting. Besides the competing attributes, these two logics have intersecting demands that allow the partial synergistic relationship without provoking conflicts between logics.

First, the market logic demands that craft product is subject to any changes stemming from market forces such as customers and competitors. Despite the uniqueness, artisan products need to satisfy the taste of customers which is changing over time. Further, to gain a competitive advantage, craft producers should take action as the first movers by innovating the products. In other words, the craft production process operates in the form of a business that is driven by market rules. In contrast, artisan logic generally requires that craft production should be more like a small-scale business that focuses more on artisan skills and manual labor, quality, aesthetics and, symbolic values, and sense of self rather than technology, quantity, material utility, and satisfaction of users, respectively. However, the present study also finds room for these two logics to get along with each other. Technology can not only help improve the precision of manual labor but also offer the chance for artisans to pursue the creation (glaze, design, color, quality of material) and a diverse range of aesthetic uniqueness that is hard to be achieved by artisan skills with manual labor only. Artisan logic also shows partial concession that paves for a new view regarding craft products leading to the penetration of technology. So, that permits the actors to traverse the blurry boundary between these logics without incurring institutional conflicts.

Such blended relationship results in diverse product innovation. The artisan logic will encourage the preservation and the pursuit of craft products in their purest form, while market logic will suggest product innovation in a very wide range. The mutual intersection of these two logics recommends a nuanced strategy that allows technology to engage more in artisanship as long as it does not violate the artisan logic’s attributes outside the intersection. Figure briefly presents the current research results.

The current study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, this study has identified the premise underlying the strategic response of hybrid organizations to institutional pressures. While the wisdom of organizational behaviors in the institutionalized context has been taken for granted due to the breakup with the nature of the relationship between logics, this study extends the effort of the recent stream of literature on the diverse strategies of artisan entrepreneurs with more insights. Artisanal entrepreneurs’ strategy is a tensional process that builds on the identification of market logic and artisanal logic. Solomon and Mathias (Citation2020) revealed that artisanal entrepreneurs face the conundrum between firm growth and artisanal identity. Applying counter-institutional identity literature, they found that the pursuit of firm growth will be rejected if artisanal entrepreneurs realize its threats to their artisanal identity, particularly their independence. The process of being “deviant” may happen when the development of relational identity leads to the likelihood of accepting the reduced artisanal attributes. They show the dynamic and nuanced different approaches of artisanal entrepreneurs in coping with the tension of firm growth and preservation of traditional values. The attitude of the artisan business owners of the present study who recognize the opportunities for product innovation from the blended relationship between logics may challenge the result from Gilbert et al. (Citation2006, p. 937) that refers artisan entrepreneurs as those who “must choose growth to foster venture growth”. It also challenges Besharov and Smith’s (Citation2014) study’s result for the prediction regarding the existence of an “extensive conflict” situation when there have equally powerful logics that are characterized by different demands. In the current study, that is because the existence of the blurry boundary in the mutual sphere between logics helps firms avoid being “deviant” because of the partial compatibility of institutional logics’ demands.

Second, the current research’s finding on the blendedness of the relationship between logics also extends the analysis of the relationship between logics. The existing literature suggests that the relationship between logics can be fluid and changeable over time as the result of contextual factors. For example, Goodrick and Reay’s (Citation2011) review reveals not only the coexistence of multiple logics, but also the correlation in the fluid relationship among them. They found that the practices of pharmacists in the USA changed through five eras from 1852 as a result of the comparative effects of such four logics as market, state, profession, and corporate. All these four logics that collectively have affected the professional work of pharmacists throughout the long period since the 1800s showed the cooperative and competing relationship. Dunn and Jones’s (Citation2010) study gives more insights into the dynamic balance and relationship between care and science logics in medical education. Accordingly, the relationship between logics in professions that co-exist will evolve over time under the changes of the exogenous forces. In other words, institutional logics are not only the source of subsequent institutional change but also affected by external forces that drive the comparative balance between them. By conceptualizing the new form of the relationship between logics as “blended”, the authors of the current study mean some attributes are compatible while some others may be incompatible. The partial compatibility of such two logics clarifies the multi-faceted actions at the firm level where multiple logics partly reinforce the firms’ actions (Besharov & Smith, Citation2014). It is useful for further elaborating on how organizations can reconcile logics when logics co-exist. The compatible components of logics will be a “safe zone” that allows artisan businesses to avoid the troubles resulting from conflicting demands. Whilst, the competing components drive the organizational reaction through their innovation in different directions. In other words, if “blendedness” does not exist, then the tension from institutional demands will trap hybrid organizations like artisan businesses in a dilemma between business growth and de-growth. Thus, this study provides further evidence that supports the “Trojan horse” strategy suggested by A. Pache and F. Santos (Citation2013) with which social enterprises that originate from the business field but try to engage in social welfare logic incorporate some institutional elements of social welfare logic to achieve a higher level of legitimacy. This study unveils how artisan entrepreneurs who “emphasize manual production over mass-production, independence over conglomeration, local community over scale, and value creation over profit maximization” (Solomon & Mathias, Citation2020, p. 1) to the different institutional demands. Their reactions through product innovation provide further support for the local creativity and innovation (Luong et al., Citation2019; Nguyen et al., Citation2022) that are often ignored in the mainstream of the management and organization literature.

This research finding suggests that future research should further explore the dynamics of the mutual intersection between logics. In other words, future research may analyze how the mutual intersection between logics is sustained over time. Moreover, this research finding recommends that future quantitative research can test the impact of artisan logic, and market logic on product innovation among artisan firms. More importantly, future quantitative research can explore the moderation role of artisan logic on the relationship between market logic and product innovation among artisan firms.

This research has not been done without limitations. The finding regarding a relatively homogeneous group of artisan business owners in ceramics production needs to be carefully either interpreted or generalized to other fields of a broader context of artisanship. This research only identifies the mutual intersection that is made of compatible institutional attributes but fails to capture the dynamism of such a mutual intersection.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the interviewees, and the local community members who provide great support in my data collection and interpretation. Special thanks to one anonymous researcher who helps me in back-translation process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this table, the “artisan” refers to those who are conferred at least one artisan certificate and do not run a business as owners. They can trade their product in a form of small business but they produce products by themselves.

2. Business owners here mean those who run business that trades ceramic products and do not hold artisan certificate.

References

- Aakko, M. (2018). Unfolding Artisanal fashion. Fashion Theory, 23(4–5), 531–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704x.2017.1421297

- Adamson, G. (2010). The invention of craft. Bloomsbury.

- Battilana, J. (2006). Agency and institutions: The enabling role of individuals’ social position. Organization, 13(5), 653–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508406067008

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318391

- Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing – insights from the study of social enterprises. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397–441. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.893615

- Besharov, M., & Smith, W. (2014). Multiple institutional logics in organizations: Explaining their varied nature and implications. Academy of Management Review, 39(3), 364–381. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0431

- Binder, A. (2007). For love and money: Organizations’ creative responses to multiple environmental logics. Theory & Society, 36(6), 547–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-007-9045-x

- Browder, R. E., Crider, C. J., & Garrett, R. P. (2022). Hybrid innovation logics: Exploratory product development with users in a corporate makerspace. Journal of Product Innovation Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12654

- Bui, X., Nguyen, T., Bui, T., & Ta, T. (2013). Bat trang lang nghe lang van (1st ed.). Hanoi Publisher.

- Campana, G., Cimatti, B., & Melosi, F. (2016). A proposal for the evaluation of craftsmanship in industry. Procedia CIRP, 40, 668–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.01.152

- Collins, H. (2019). Creative research: The theory and practice of research for the creative industries. Bloomsbury Visual Arts, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Do, T. (1989). Que gom bat trang (1st ed.). Hanoi Publisher.

- Dunn, M., & Jones, C. (2010). Institutional logics and institutional pluralism: The contestation of care and science logics in medical education, 1967–2005. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 114–149. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.114

- Fanchette, S., & Stedman, N. (2009). Discovering craft villages in Vietnam: undefined itineraries around Hà Nội. IRD Éditions.

- Frenken, K., Vaskelainen, T., Fünfschilling, L., & Piscicelli, L. (2020). An institutional logics perspective on the gig economy. In I. Maurer, J. Mair, & A. Oberg (Eds.), Theorizing the sharing economy: Variety and trajectories of new forms of organizing (research in the sociology of organizations (Vol. 66, pp. 83–105). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X20200000066005

- Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 232–263). University of Chicago Press.

- Genin, A. L., Tan, J., & Song, J. (2020). State governance and technological innovation in emerging economies: State-owned enterprise restructuration and institutional logic dissonance in China’s high-speed train sector. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(4), 621–645. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00342-w

- Gilbert, B. A., McDougall, P. P., & Audretsch, D. B. (2006). New venture growth: A review and extension. Journal of Management, 32(6), 926–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306293860

- Glaser, B. (1992). Glaser. Basics of grounded theory analysis. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory (1st ed.). Sociology Press.

- Goodrick, E., & Reay, T. (2011). Constellations of institutional logics. Work and Occupations, 38(3), 372–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888411406824

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Readings in Economic Sociology, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470755679.ch5

- Gümüsay, A. A., Smets, M., & Morris, T. (2020). “God at work”: Engaging central and incompatible institutional logics through elastic hybridity. Academy of Management Journal, 63(1), 124–154. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0481

- Hawkesworth, M. (2014). Contending conceptions of science and politics: methodology and the constitution of the political. In D. Yanow & P. Schwartz-Shea (Eds.), Interpretation and method: Empirical research methods and the interpretive turn (2nd ed., pp. 27–49). M.E. Sharpe.

- Humphreys, A., & Carpenter, G. S. (2018). Status games: Market driving through social influence in the U.S. wine industry. Journal of Marketing, 82(5), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.16.0179

- Kabwete, C., Ya-Bititi, G., & Mushimiyimana, E. (2019). A history of technological innovations of Gakinjiro wood and metal workshops. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation & Development, 11(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2018.1550928

- Kellogg, K. (2009). Operating room: Relational spaces and microinstitutional change in surgery. The American Journal of Sociology, 115(3), 657–711. https://doi.org/10.1086/603535

- Kitchener, M. (2002). Mobilizing the Logic of managerialism in professional fields: The case of academic health centre mergers. Organization Studies, 23(3), 391–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840602233004

- Lindbergh, J., & Schwartz, B. (2021). The paradox of being a food artisan entrepreneur: Responding to conflicting institutional logics. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/jsbed-08-2019-0288

- Luong, A., Sun, F., & Sham, S. (2019). Factors influencing Vietnam’s handicraft export with the gravity model. Journal of Economics and Development, 21(2), 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/jed-08-2019-0021

- Mars, M. M., & Lounsbury, M. (2009). Raging against or with the private marketplace?: Logic hybridity and eco-entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Inquiry, 18(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492608328234

- McVey, L., Alvarado, N., Keen, J., Greenhalgh, J., Mamas, M., Gale, C., Doherty, P., Feltbower, R., Elshehaly, M., Dowding, D., & Randell, R. (2020). Institutional use of national clinical audits by healthcare providers. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 27(1), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13403

- Nguyen, V., Nguyen, T., Ha, T., Bui, D., & Vo, H. (2022). Cac logic the che va chien luoc doi moi san pham trong cac doanh nghiep san xuat thu cong. Journal of Economics and Development, 301(2), 38–48.

- Pache, A. -C., & Santos, F. (2013). Embedded in hybrid contexts: How individuals in organizations respond to competing institutional logics. In M. Lounsbury & E. Boxenbaum (Eds.), Institutional logics in action, part b (research in the sociology of organizations, vol. 39 part B) (pp. 3–35). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X(2013)0039AB014

- Pache, A., & Santos, F. (2010). When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of Management Review, 35(3), 455–476. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.35.3.zok455

- Pache, A., & Santos, F. (2013). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 972–1001. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0405

- Phan, H., Nguyen, D., & Nguyen, Q. (1995). Bat trang ceramics: 14th-19th centuries (1st ed.). The gioi Publishers.

- Pret, T., & Cogan, A. (2019). Artisan entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(4), 592–614. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijebr-03-2018-0178

- Reay, T., & Hinings, C. R. (2009). Managing the rivalry of competing institutional logics. Organization Studies, 30(6), 629–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609104803

- Reay, T., & Jones, C. (2016). Qualitatively capturing institutional logics. Strategic Organization, 14(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127015589981

- Ruef, M., & Scott, W. R. (1998). A multidimensional model of organizational legitimacy: Hospital survival in changing institutional environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4), 877–904. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393619

- Schaffer, F. C. (2016). Elucidating social science concepts: An interpretivist guide. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Scott, W. R. (1994). ‘Conceptualizing organizational fields: Linking organizations and societal systems’. In H. Derlien, U. Gerhardt, & F. Scharpf (Eds.), Systemrationalitat und partialinteresse (pp. 203–221). Nomos Verlagsgescellschaft.

- Scott, W. R. (2008). Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory & Society, 37(5), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-008-9067-z

- Solomon, S., & Mathias, B. (2020). The artisans’ dilemma: Artisan entrepreneurship and the challenge of firm growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(5), 106044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106044

- Terrio, S. (1996). Crafting grand cru chocolates in contemporary France. American Anthropologist, 98(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1996.98.1.02a00070

- Thornton, P. (2002). The rise of the corporation in a craft industry: Conflict and conformity in institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069286

- Thornton, P. (2004). Markets from culture: Institutional logics and organizational decisions in higher education publishing (1st ed.). Stanford University Press.

- Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin-Andersson, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), Handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 99–129). Sage.

- Thornton, P., & Ocasio, W. (1999). Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: Executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958– 1990. The American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 801–843. https://doi.org/10.1086/210361

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A New approach to culture, structure and process. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199601936.001.0001

- Tracey, P., Phillips, N., & Jarvis, O. (2011). Bridging institutional entrepreneurship and the creation of new organizational forms: A multilevel model. Organization Science, 22(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0522

- Twigger Holroyd, A., Cassidy, T., Evans, M., & Walker, S. (2017). Wrestling with tradition: Revitalizing the Orkney chair and other culturally significant crafts. Design and Culture, 9(3), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2017.1370310

- Valentine, J. (2017). Cultural Governance and Cultural Policy: Hegemonic myth and political logics. In The Routledge handbook of global cultural policy (pp. 148–164). Routledge.

- Van Maanen, J. (2011). Tales of the field (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Not to mention the break-the-ice questions and questions that emerged during interviews/talks, the below section provides the key guiding questions for interviews/talks with research informants

Key guiding questions for interviews with artisan business owners:

What is your business’ main product category?

To what extent have you introduced new or improved products?

Could you please describe the changes in your products over time?

What drove the changes in your products?

What do you think you should do to respond to the market needs?

Could you please clarify any limit for such changes and if there is any limit for the changes? Why?

What remained unchanged? Why?

Which symbolic value do you think your products can represent?

Please tell me more about how you perceive your responsibility towards artisanship? Why? and how can you do that? And what did you do with that?

Do you have any concern regarding artisanship?

Key guiding questions for interviews with artisans:

Could you please summarise your journey to artisanship?

Which word(s) can best represent the value of your products?

What changes and what remains unchanged in your products over time?

Could you please give specific examples to clarify such changes or unchangedness?

What do market needs mean to you and your work?

What does artisanship mean to you?

Do you think you have any responsibility for maintaining artisanship? If yes, how did you do that?

Do you feel any pressure from the proliferation of successful businesses in your field? And why do you feel that way?

Key guiding questions for interviews with business owners:

Why did you start your business in this field? And how?

What value do ceramic products bring to your business?

Could you identify any difference in the way you and artisans perceive the value of ceramic products?

Why such difference(s) exist?

What changes and what remains unchanged in your products over time?

Could you please give specific examples to clarify such changes or unchangedness?

What made changes or unchangedness in your products?

Key guiding questions for interviews with local citizens:

What value do you think artisan products represent?

How do local citizens like you perceive the importance of such products?

From your own observation, what did you find about the changes in ceramic product or production of these two craft villages where you were born?

What remains unchanged?

Please show me what you think or feel about such changes?

If you have only two options with like or dislike, which one is your preferred one when you think about such changes and unchangedness?

What is your expectation for craft business and production in your village here?

Key guiding questions for interviews with customers:

What motivates you to buy these products?

Does your specific consumption need (taste) of these products change over time? If yes, why and how?

What do you like the most about these products? Please be specific

What is your expectation for the craft ceramic business and production?