Abstract

Supply Chain Management (SCM) fulfils an important role in the economy and public expenditure of a country and can be regarded as a critical factor for the efficiency of a government because it is a main component of public service delivery. Since the introduction of the SCM policy in South African public sector it has been faced with a myriad of challenges which are hampering service delivery. This study aims to investigate the challenges in supply chain management, affecting service delivery in the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality (MMM). The study was qualitative in design. Semi-structured interviews were used, and the data was thematically analysed. One of the findings of this study is that the SCM department cannot function properly if there are instability, lack of integrity, lack of human capacity, lack of skills, non-payment of suppliers, political interference, corruption, and lack of accountability. The supply chain management system should move from a paper-based system to an electronic system to allow for effective and efficient service delivery. Public officials should be able to interpret the acts, rules, and regulations, as well as policies, governing SCM. The study recommended that, to improve service delivery, there is a need to hire people in supply chain management who have the capacity and skills to do the job. The study also recommended that, internal controls need to be strengthened in all areas of SCM and legislation needs to be reviewed to allow for the quicker procurement of goods and services.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The Auditor General of South Africa has highlighted in the local government audit outcomes that SCM Department in the MMM is facing challenges such as skills shortages, instability and non-compliance with policies and legislation. To improve the challenges in SCM local government needs to review SCM legislation and policies. The local government needs to adopt and implement practices that promote effective control and management of its supply chain. It is imperative that the SCM Department is equipped with enough human resources, ensure the timely payment of service providers and compliance with regulatory frameworks in order to alleviate the challenges in SCM in the MMM.

1. Introduction

Supply Chain Management (SCM) has evolved over the years from being mainly used in the private sector to being applied in the public sector and municipalities (M. M. Sibanda, B. Zindi, et al., Citation2020). The purpose of SCM is to achieve value for money, as a result, there are five pillars on which procurement is based in South Africa, which are: value for money, equity, openness and effective competition, ethics and fair dealing, accountability, and reporting. SCM also consists of four management functions, namely: demand management; acquisitions management; logistics management; and disposal management. SCM in South Africa (SA) encounters problems, such as the practice of over-reliance of individuals in areas of asset management, revenue management and SCM and this is also highlighted in the comments of the Auditor General Report (2018–19) on procurement.

The procuring of goods by a municipality and the assurance that these goods are supplied to the end users entails an effective SCM. Therefore, there will be an upgrade in service delivery if the procurement process is not flawed. Hence, this research focuses on municipal management with a direct focus on the challenges of SCM, affecting service delivery within the local government with MMM as a case study. The system of SCM has certain objectives by providing value for money, while improving government, particularly the provision of services.

Van der Walt, Phutiagae, Nealer, Venter, Khalo and Vyas-Doorgapersad (2018:243) state that at the forefront of socio-economic development is South African Municipalities, and the delivery of services and goods requires such development to fulfil the requirements of the communities. To deliver excellent services to communities, municipalities have a dependency to some degree, on external suppliers. Furthermore, even though there is need for municipalities to procure some of the commodities and services externally, there are still instances in which most goods and services are provided internally to support service delivery.

Van der Walt et al. (Citation2018, p. 243) further state that a clear strategy, therefore, needs to be developed by municipalities on how externally supplied resources are to be obtained; that is how these goods and services are to be purchased, chosen, and handled. Therefore, there is a need for municipalities to develop an asset disposal and procurement system that will enable them to provide goods and services. This system is managed through a process known as SCM. It is a long term, complex link to quality service delivery. The SCM determines the effective and efficient movement of resources, services, products, data, and financial information from the first tier of service providers, through the numerous intermediary groups to the final consumer.

2. Background

The management and organisation of the SA public sector is to guarantee that the systems of SCM are set up for the critical supply of goods and services to the residents. The obligation of public service departments is to supply goods and services to the people of SA; hence, it is essential that this is done in an equitable, transparent, fair, and economical manner. The tools of SCM ensure that quality services and goods are supplied at a fair and reasonable price (Manzini et al., Citation2019, pp. 117–129).

Pauw et al. (Citation2015) state that the purpose of the public sector is to provide services and the aim of the private sector is profit-making. The private sector is the sector in which profit is used as a gauge of achievement. The public sector is the sector in which service to the general population is the main gauge of accomplishment. Furthermore, procurement of goods and services, through direct negotiation, will occur when there is a catastrophic event, then there is critical importance for early delivery required for urgent cases and the request of quotations is either impractical or impossible.

Xhariep, Lejweleputswa, Thabo Mofutsanyana, Fezile Dabi District, including MMM, are municipalities in the Free State (FS), which have evaded on paying their creditors on time and other suppliers when likened to other municipalities in other provinces. The adverse financial effects on rural businesses, municipalities, youth, and women, who own Small, Medium and Macro Enterprises (SMMEs) have been due to the non-payment of suppliers (Tshilo & Van Niekerk, Citation2016, pp. 109–126). There is a dispute between the MMM and Bloem Water, concerning the contract signed by both partners for supply of bulk water (Kusakana et al., Citation2019, pp. 104–108).

Glasser and Wright (Citation2020, pp. 413–441) expand on Tshilo and Van Niekerk’s assertion by giving an example of the MMM when Bloem Water decreased the pressure of water, and this was because of the failure by the Municipality to pay a debt amounting to R247million. Glasser and Wright (Citation2020, pp. 413–441) argue that it is not transparent that the decreased water load would institute a grave infringement of the Municipality’s service delivery responsibilities. In its attempts to ensure that the citizens of Mangaung would not suffer because of an avoidable tassel amongst the Municipality and the service provider, Bloem Water, the City revisited the court order that was lodged against the water entity.

It is a government’s obligation to supply decent water quality to the public (The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996). Kusakana et al. (Citation2019, pp. 104–108) argue that until now, this does not seem to have been accomplished. The result of the supply of poor water quality by the Municipality has led to the people developing a bad impression about the MMM and the Department of Water and Sanitation. According to Kusakana et al. (Citation2019, pp. 104–108), in the agreement between Bloem Water and MMM it is stated that a payment of at least 70% of the bulk water will be made to Bloem Water by MMM. It is further agreed by the stakeholders that MMM has the responsibility to pay Bloem water for 70% minimum of the bulk water if it fails to pay for the minimum percentage of water (Kusakana et al., Citation2019, pp. 104–108). Against this background, we ask the following question relevant for academic research and supply chain practice: What are the challenges in SCM affecting service delivery in the MMM? Avoiding the challenges in SCM requires knowing what the term entails and how it is legally defined. Then, recognising that we can only approach the challenges of SCM if we really understand the phenomenon, including insights from other authors who have researched about SCM in the section below.

2.1. Theoretical overview

This section covers the concept of public SCM and discusses the conceptual framework, Empirical Review of literature about the challenges facing SCM locally, regional, and global.

2.1.1. Public sector SCM defined

Mantzaris (Citation2017, pp. 121–133) states that SCM can be well defined as the strategic, planned, and logical procedures and structures designed, at refining the extended performance of a public or private unit through the impartial, transparent, moral, and active deployment of a variety of multi-level networks. Manzini et al. (Citation2019, pp. 117–129) argue that public SCM in the public sector may be seen as procurement through buying of commodities and services by government. Mafini and Masete (Citation2018) argue public SCM is a practice that is essential in the administration of municipal supplies. It has a tactical responsibility in the public sector’s capacity to provide on its duties of service delivery in connection with the government’s service delivery, as prescribed by the South African Constitution (Republic of South Africa, 1996).

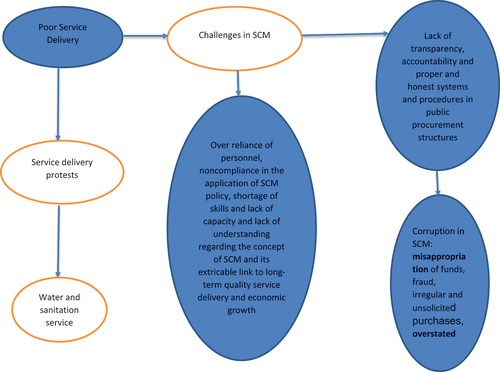

2.2. Conceptual framework for MMM: Challenges in SCM affecting service delivery

Based on this framework highlighted in figure , the challenges in SCM are important in identifying the causes of poor service delivery. The challenges in SCM and its effect on service delivery are articulated in the framework above in figure . The notion presented in the conceptual framework above is that the challenges in SCM are the over reliance of staff in the MMM. According to the Auditor General’s report (2018–19), there is nonconformity in the use of the SCM policy; shortage of skills and lack of capacity; and the lack of knowledge concerning the concept of SCM and its extricable connection to long-term quality service delivery and economic development. The other challenge is lack of transparency and accountability, which leads to corruption in SCM and the misappropriation of funds and fraud. To substantiate this, there is continued diminishing of public trust in government to meet its obligations to deliver adequate economic and social services, as well as to ensure accountability and transparency in its affairs (Mathiba, Citation2020, pp. 642–661).

2.3. Empirical review

This section looks at public procurement and SCM in South Africa, regionally and globally.

2.3.1. Global trends

The processes of public procurement through which the public sector and governments obtain required goods, works and services can be used to uphold certain guidelines. Accelerating the hiring of underprivileged groups, encouraging impartiality, and guarding the surroundings while procuring goods and services, solve two problems at once (Mantzaris & Ngcamu, Citation2020, pp. 207–249). Mantzaris and Ngcamu (Citation2020, pp. 207–249) further state that an example of how social and environmental deliberations can lead to discernment is well explained in two milestone cases, namely that of Beetjes and Concordia Bus.

A tender by Gebroeders Beentjes BV in the Beentjes case was excluded by the Netherlands Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, because it seemed less suitable than that of the next lowest bidder. The authority, which awarded it, indicated that the Beentjes did not have the required experience and that it did not seem to be in the position to hire long-term out of work individuals (Mantzaris & Ngcamu, Citation2020, pp. 207–249). Martinić and Kozina (Citation2016, pp. 159–165) argues with Mantzaris and Ngcamu’s (Citation2020, pp. 207–249) assertion that the emergence of the new European Public Procurement Act 2020, is one of the many motives Europe initiates to create equality in terms of community and skilled incorporation or recuperation of disabled and underprivileged people, such as unemployed members of minority or other disadvantaged groups, publicly marginalised.

2.3.2. Europe, Asia, and North America

The vulnerabilities of supply chains across many industries have been exposed by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Health care systems in many countries in the recent years have stimulated or forged the offshoring of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) production to less costly service providers. Ninety-five percent of surgical masks in the United States and 70% of ventilators are manufactured abroad. During the COVID-19 epidemic in the People’s Republic of China, factory closures and prohibitions on travel and PPE export have put significant political and technical constraints on the market, while the evolving nature of COVID-19 has strained PPE supply chains (Park et al., Citation2020, pp. 1–10).

Countries, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, United States, France, Mexico, and China became pioneers in producing medical supplies. France requested domestic manufacture of ventilators for French healthcare workers in March 2020. National export restrictions on masks were imposed by Germany on face shields and other PPE, which later led to the scarcity of health kits between European Union countries (Andaneswari & Rohmadiena, Citation2020, pp. 171–188).

2.3.3. SCM challenges in Africa

SCM challenges for a study conducted on Kenya’s petroleum industry discovered that deficiency of premeditated stocks, moderately high petroleum costs, continuous fuel scarcities, below standard products, and a deviation of goods, destined for exports back into the country, were the main challenges (Bimha et al., Citation2020, pp. 97–109). A related study on challenges and themes in making SCs environmentally sustainable established that five key challenges for SCM are costs, intricacy, operationalisation, mind set and social challenges and uncertainties (Bimha et al., Citation2020, pp. 97–109).

2.3.4. SCM challenges in South America

The main challenges shown in an exploratory survey hindering SC performance in Uruguayan SMEs found 18 problems, which hamper SC performance personnel. However, the main hindrances were product availability and government policies, followed by data machineries, dedication of top management, macro-economic factors and market uncertainty, political environment, as well as local warehouse structure, among other challenges (Bimha et al., Citation2020, pp. 97–109).

2.3.5. Challenges facing SCM in South Africa

This section discusses the challenges facing SCM in South Africa, which include lack of accountability, corruption and non-compliance with policies, rules, and guidelines.

2.3.5.1. Lack of Accountability

According to Shava and Mubangizi (Citation2019, pp. 74–93), social accountability is the wide-ranging activities and instruments outside voting, which citizens can undertake to hold the Government to account, and activities on the part of Government, action groups, media, and other social players that sponsor or enable these effects. Nkwanyana and Agbenyegah (Citation2020, pp. 1–9) argue that non-payment of service providers, are among many areas of weaknesses, including political interferences during administering of tenders, below standard valuations of criteria and uneven tender practices.

The Auditor General of South Africa (2019) condemns this on lack of preparation, insufficient procedures, shortage of reliable reporting and accountability and insufficient monitoring by all role players engaged with the SCM process. In the Consolidated General Report on Local Government audit outcomes (2018–19), the AGSA states that there is lack of oversight over public money, which leads to weak accountability and resultant experience to mishandling of public money of which fiscal maladministration and ethical transgression cannot be excepted (Van Niekerk & Sebakamotse, 2020:269–293). Corrupt procedures limited to procurement dealings include corruption, coercion, theft, favouritism, patronage practices and dishonesty (Fourie, Citation2018, pp. 726–739).

2.3.5.2. Corruption and Non-Compliance- to Rules, Regulations and Policies

According to Mhelembe and Mafini (Citation2019, pp. 1–12) fraud and corruption involved in unethical conduct, cost the SA Government sizable sums of income yearly, as fruitless, and wasteful expenditure. Mhelembe and Mafini (Citation2019, pp. 1–12) further argue that in 2014, for example in the SA Government paid around R26, 4 billion in aspects that breached rules and policies, as well as corruption. In addition, the lack of a skilled SCM staff is exacerbating the situation, which continues to be one of the major restrictions to the growth of business functions in SA. Moreover, ineffective monitoring and evaluation, the lack of adherence to current policies, lack of preparation and too much decentralisation of the procurement method are among the many challenges facing public sector SCM.

Mantzaris and Ngcamu (Citation2020, pp. 461–479) further substantiate this by stating that the previously compromised SCM and procurement systems are further weakened, because of an apparent need of organisation, insufficient distribution of knowledge and poor record-keeping. These are the foundations that led government officials to be beneficiaries of donations and benefits that they were not eligible to, due to the absence of incorporation, certification and sharing data realities. These disparities and vulnerabilities led to SCM legislation being put on the side, clear indications of overpricing, fraudulent procedures, and possible dishonesty.

3. Methodology

The study adopted an interpretive philosophical paradigm (Ikram et al., Citation2018, pp. 121–124) and a case study research design (Webb & Auriacombe, Citation2006, pp. 588–602). The qualitative research design used was a case study, and it was applicable to this kind of investigation because tools that are largely grounded on the qualitative method were equipped and managed by a researcher to acquire significant information about the supplies and public officials’ views on the challenges of SCM, affecting service delivery. The study population consisted of senior municipal officials. The study employed snowball sampling, a technique commonly used in qualitative studies, central of which are the traits of interacting and recommendation (Parker et al., Citation2019).

The interview sample was eight. The researcher used snowball sampling to select the General Manager SCM, HOD Corporate Services and CFO in the Finance Department and five participants in the SCM Department, recommended by only the General Manager SCM, who have knowledge about the challenges in SCM affecting service delivery and who added value to the research.

3.1. Research design

The qualitative research design used was a case study and it was appropriate to this kind of investigation, since tools that are mostly grounded on the qualitative method were equipped and managed by a researcher to acquire significant data about the supplies and public officials’ opinions on the challenges of SCM, affecting service delivery. Webb and Auriacombe (Citation2006, pp. 588–602) state that a research design consists of plans of interpreting, collecting, and processing, as well as a clear statement intended to test the hypothesis and provide answers to the research question. This method of study was relevant, because it focussed on a real-life case study of the MMM, which has characteristics of a qualitative research methodology. Therefore, qualitative methodology usually comprises a case study. It is an approach referring to measures, practices, and approaches to implement a plan that is employed in the process or research design (Webb & Auriacombe, Citation2006, pp. 588–602).

3.2. Data collection instruments

The researcher used semi-structured interviews, which permitted him to make follow-ups in exciting paths that emerged from the interview, and respondents were able to give a complete image by questioning participants for data. Face-to-face interviews were conducted. Participants were recruited through personal invitations by both phone calls, email, and personal visits after giving a full explanation of the purpose of the research. A digital voice recorder was used to conduct the semi-structured interviews. Participants were helped by the researcher in answering the questions from the interview guide by clarifying some concepts verbally.

3.3. Data analysis

Thematic analysis is a qualitative approach of detecting, evaluating, and describing patterns within a data corpus (Scharp & Sanders, Citation2019, pp. 117–121). The study adopted a thematic analysis to describe themes; that is information trends that are significant or valuable, and to use these themes to examine the challenges in SCM affecting service delivery in the MMM. Thematic analysis involves a six-phase analytic method. Thematic analysis, like most methods to qualitative analysis, is not strictly a linear procedure. Instead, it is reiterative and recursive (Terry et al., Citation2017, pp. 17–37). Terry et al. (Citation2017, pp. 17–37) state that the first phase of thematic analysis is a process that involves the researcher familiarising himself with the data, and it begins at data collection. Generating codes is the second phase, which involves the researcher immersing himself with the data in-depth and establishing the structure sections of analysis. As coding advances, the researcher began to see patterns and notice connections throughout the data. However, it was fundamental for the researcher that before moving from coding to creating themes, to keep concentrating on coding the whole dataset in the third phase. The researcher developed draft themes at this point, which are a flexible piece of writing, and flexibly open to alterations (Terry et al., Citation2017, pp. 17–37). The fourth phase involved revising prospective themes. There are various methods and questions to drive progress to identifying and selecting themes and ultimately improving the whole analysis during the sixth and final stage, creating the report. The report provided the last chance to make modifications that improved the analysis and essentially shared the analyst’s description of the information (Terry et al., Citation2017, pp. 17–37). The researcher used a combination of ATLAS TI and OTTER.AI software for converting audio data into text.

3.4. Ethical considerations

Ethical factors attached to the study were considered by the researcher. Therefore, the privacy and identity of those officials and other key individuals in the study were protected by the researcher. The assurance of anonymity was given at the start of the interview and the assurance was included in the informed consent form, signed by the interviewee. The study was in alignment with the institution’s research ethics policy. The researcher also took into consideration all the other institutions, which were involved, such as Government’s ethics and research policies or any policies that were of relevance to the study. The research first got clearance from the Faculty Research Ethics Committee at UFS. The ethical clearance number for this research is UFS-HSD2022/0051/22. The researcher also asked for permission from participants.

4. Discussion of findings

This section provides detail on the description of the themes and codes generating from this study on the challenges in SCM in the MMM.

4.1. Instability in SCM

This theme has identified how participants view instability as a challenge, both in SCM and service delivery. Participants noted that instability has an effect in the sitting of the bid committees. Instability also leads to uncertainty in SCM as the constant changes in management, which affect decision-making and productivity. This theme relates to the first objective of this study as it identifies the challenges in SCM in MMM. Mafini and Masete (Citation2018, pp. 581–593) have supported this claim by identifying that municipalities in South Africa are failing to implement corporate governance, due to various costs, such as loss of integrity, decline in investors’ interest to invest in municipalities, communities protesting about poor service delivery, mismanagement, and unforeseen leadership changes in municipalities without preparing for succession.

4.1.1. Instability

The following codes identified instability within an institution. It has been noted by participants X, C, Y and D that there is instability caused by the inconsistent appointments of different City Managers. These instabilities result in delays in service delivery, which disrupts the service delivery system (Zweni et al., Citation2022, pp. 169–188) Political instability is among the many reasons municipalities fail to fulfil their executive obligations that makes the municipalities not have proper governance structures and tools. Lack of proper governance leads to a collapse in municipal structures, thus leading to municipalities being placed under administration by the provincial governments in their respective provinces. During an interview, one participant noted that:

Participant D: The other problem is that they change managers too much. If I tell you that, in this financial and past financial year, we have had three general managers. That’s a problem because everybody has their own management style. Attempting to take, somebody who knows nothing about supply chain has no idea and it just creates a lot of chaos, mistrust, and friction amongst colleagues. One would retaliate and say I can’t work with somebody who I’m supposed to look up to for advice, but who doesn’t even know as much as I do.

In addition, another participant during an interview noted that:

Participant C: The first one is the issue of top management changing the GM of supply chain now and then.

Another participant during an interview stated that:

Participant Y: we found ourselves being led by three different types of general managers. The GM was just merely and procedurally removed from the position claiming that they are doing some investigations and then they brought in two more people.

Another participant added that;

Participant X: The other issue is your instabilities within the institution. If you are in an institution, whereby we are having the acting city manager today, the following week or following month, there’s another city manager. The one that basically signed those things we don’t know what happened to that so we must start afresh. So, instabilities within the institution also cause delays in terms of services actually disrupts the Service Delivery System.

4.2. Integrity

This theme has identified the lack of integrity in SCM. Participants noted that there is lack of integrity by SCM officials and service providers in conducting their work. There is falsifying of invoices and lies about machinery of service providers. This theme relates to the first objective of this study as it identifies the challenges in SCM in MMM. Fourie (Citation2018, pp. 726–739) has supported this claim by maintaining that integrity in public procurement must be the starting point of any attempt to minimise corruption. General policies for officials in government should be a requirement, as well as codes of conduct to ensure the employment of certain criteria for SCM officials.

4.2.1. Lack of integrity

Participants have mentioned the issue of lack of integrity leading to the appointment of people who lack skills and knowledge in SCM. It has been noted by participants A, D and Z that there is a lack of integrity leading to the appointment of officials in SCM who lack the knowledge and skills, which is affecting service delivery. One of the things that service providers do when completing a bid document is to lie about their staff component and machinery contents. Participants have mentioned the need for suppliers to be truthful in submission of tender documents. It has been noted by participant A and D that suppliers need to be truthful in what they are saying in the tender documents by submitting a list of all the projects they have done. Service providers should also be truthful when they are awarded tenders if they will be able to carry out the project. Adusei (Citation2018, pp. 41–50) has noted that more can be achieved from trustworthiness, competence through more transparency, fair competition and zero fraud by investors. Adusei (Citation2018, pp. 41–50) further argues that parties are colluding in the procurement procedures, which is leading to inflated prices for work and in some instances no work is completed, but payments are done. One participant echoed the same sentiments by stating that:

Participant D: The problem is unfortunately that integrity is gone. It’s no longer about the service that needs to be delivered and our communities and the people being the communities, it’s about you and I, and what we want to achieve. Instead of looking at somebody who has the skill, and the knowledge, and that you can see, will be in a position to do what is needed to be done. I will be looking at, I owe my neighbour a favour, and daughter is not working, or their son is not working, it’s time to return that favour and pay their debt. So now I’m just bringing somebody in, as a manner of repaying that debt and returning that favour but not thinking about how this person’s inexperience or lack of knowledge, or understanding, or education or skill is going to affect what needs to be done here. The service providers just need to be honest. What people need to understand is that when you do business with government it’s not a means for you to have a living. It’s a lot of lives that are affected.

Another participant during an interview noted that:

Participant A: Again, suppliers in all respect, they should be truthful to what they are saying in the tender documents. If the tender document says, please submit a list of all projects that you have done so that we can check, I think they should be truthful to submit those. One of the things that service providers do when completing a bid document is to lie. They lie of what their staff component is. They also lie of what they have in terms of machinery contents.

Another participant during an interview noted that;

Participant Z: We need people who are principled we need people who have integrity, can we find them? That’s the question. We need people who will be here and do what they are paid for, and not expect to be paid in certain ways for what they’re being paid for. So, I think we need people of integrity.

4.3. Lack of human capacity

This theme has identified the perception of lack of human capacity in SCM. Participants have noted that lack of human capacity was quite prominent amongst all participants. There is an acute shortage of skills in SCM. The shortage of skills and the inability to delegate duties are leading to a delay in service delivery. This theme is related to the first objective of this study as it identifies the challenges in SCM in MMM. Nyide (Citation2022, pp. 1–11) has supported this claim by recognising lack of individual knowledge, skills, and ability as some of the attributes within SCM in the public sector. These challenges inevitably prevent this sector from receiving clean audits, due to non-compliance with SCM policy and guidelines.

4.3.1. Human capacity

Participants have mentioned that the SCM Department is short-staffed, therefore it is affecting service delivery. It has been noted by participants B C, X, E, Y, Z and D that workflow is being affected, due to the short supply of staff in the SCM Department. Vacant posts are not being filled when a person resigns or retires from work. It is the human resources lacking as the Department is short-staffed and it is affecting the improvement of SCM. The above statement resonates with the Mangaung SCM Annual Report (2021:1), which noted that the SCM unit is understaffed. In the MMM, there are 80 positions and currently 44 (55%) positions are filled, and 36 (45%) positions are vacant. Participants have mentioned the issue of being short-staffed in SCM. It has been noted by participants A and Y that one of the challenges facing the improvement of SCM, is being short-staffed, therefore, there is failure to segregate duties on who is checking the procurement plan. Fourie and Malan (Citation2020, pp. 1–23) have noted that the South African Institute of Government Auditors laments the scarcity of skills in the public financial sector. There are internal management weaknesses and uncompetitive or dishonest procurement practices in spending supervision. There is misuse of public money, which also suggests a widespread shortage of capability, skills, and internal financial management structures within the finance department of government bodies. One participant during an interview noted with great concern that:

Participant E: another thing is that there are a lot of posts which are vacant. And then because of the funding, I think it has been a struggle since 2016–2017 to fill those positions. So, you find one person doing a job for two or three employees, which is the main problem. We have a problem of acting, I think last time I checked, it was like almost I think 60% of the municipality employees are acting.

Another participant during an interview stated that:

Participant D: I would say the flow of work is affecting, you know, procurement of services to be delivered. Number one we short staffed.

Another participant also stated that:

Participant C: Am going to be honest with you filling of posts. We are having a lot of vacant posts here. For example, we have people who have gone to retirement, some have resigned, but I want to be honest with you those vacant posts were never filled.

A participant’s comment during an interview stated that:

Participant B: the shortage of resources we are having people who resigned we didn’t lose many people in that year, but we lost someone in there. Then you see that Mangaung they take long to replace even if someone is resigning, they take long to replace. Post can be advertised people can apply at times they will be interviewed come time to appoint you don’t hear anything. So, to improve supply chain, get the required resources. We are lacking in resources; we have a short staff.

On the same note, another participant during an interview echoed the following sentiments:

Participant A: we are short, stuffed in demand management we are supposed to have at least eight officials, eight that’s the minimum, but we only have four so its 50% now what does that mean? It means somewhere somehow, we are unable to segregate duties in terms of who is a checking, the incoming work for compliance who’s checking the budget, who’s checking the procurement plan, whether user directory is procuring is in line with the procurement plan or not. So that’s the problematic challenge of being short staffed at supply chain

Similarly, another participant during an interview echoed the following sentiments:

Participant Y: Firstly, the challenges that we can also mention is about the capacity in supply chain. Now, let’s start with the institutional arrangement or institution as such capacitating supply chain would start with a political area where politicians have a wrong impression about supply chain that they have a say in capacitating supply chain, and you’ll find that ultimately, they want to interfere in terms of the governance of supply chain. Those vacancies that are not filled up the posts that have been, frozen it is also an institutional matter.

Another participant during an interview noted that:

Participant Z: according to me, there is poor performance. I don’t know maybe they are lacking capacity or skill. I just don’t know how service providers were appointed, but its poor performance for me.

On the same note, another participant echoed the following opinions:

Participant X: human capacity must capacitate, your supply chain management unit for you basically to realize service delivery because service delivery, for it to be realized, you are required to follow certain procurement processes, which is your supply chain assessment, all those things, they still need to be done by the individual homebodies.

4.4. Lack of skills in SCM

This theme has identified how participants perceive that there are people with skills in SCM. Participants have noted that the people in the SCM department have the required skills, while others said they lack the necessary skills. Participants, however, noted that there is a shortage of skills in the SCM Department, caused by failure to fill vacant posts. This theme relates to the first of objective of this study as it identifies the challenges in SCM in the MMM. Munzhedzi (Citation2021, pp. 1–8) has supported this claim by identifying that the lack of skills and capability are the biggest challenge confronting the democratic South African Municipalities. Good policies and programmes as a result are poorly employed if employed at all.

4.4.1. Unskilled people in SCM

Participants have noted that shortage of skills, experience and expertise are influencing factors towards rendering a poor service delivery in SCM. It has been noted by participants D, E, X and Z that they are employed and do not have the necessary skills and are easy to manipulate. The people appointed are not competitive enough, and it can be a problem for compliance. If officials are not familiar with the applicable legislations, they will not follow them, and it will have an impact on the audit report. Mhelembe and Mafini (Citation2019, pp. 1–12) argue that in 2014, for example, the SA Government spent around R26,4 billion in circumstances that breached laws and policies, as well as corruption. In addition, the lack of skilled SCM personnel is exacerbating the situation. However, other participants mentioned that they are all skilled and knowledgeable in SCM. It has been noted by participants A, B and C that they have knowledgeable and skilled people in SCM as it is a highly regulated environment with over 15 Acts. The people in SCM understand the timeframes and comply with rules and regulations that govern supply chain. The people in SCM are appointed based on their qualifications. In recent years’ service delivery protests have escalated. Lunga et al. (Citation2019, pp. 435–446) argue this situation is provoked by the reality that municipalities are beleaguered by challenges of infrastructure backlogs, maladministration, and incapacity due to lack of skills. One participant during an interview noted with great concern that:

Participant E: I think it’s one of the major problems, certain individuals are not appointed because they are competent to execute what is expected of them. I think it either slows the service delivery and then also, it might be the problem or a challenge with regard to compliance because, if you are not familiar with the applicable legislations, then you not going to follow them and then that might impact the audit report that our municipality was non-compliant.

Another participant during an interview noted that:

Participant D: definitely, that’s a resounding yes. Look, I can’t be sitting here and not have the necessary skills to execute my small portion of what I should do and think that it wouldn’t have an effect on service delivery.

However, one participant during an interview echoed a different sentiment by noting with great worry that:

Participant C: supply chain has lost regulations, guides that guide us. I will not say a lack of skills, experience, and knowledge it’s a factor. I will say to other officials or the other user Department not necessarily us supply chain officials and bid committee members. Remember supply chain management officials and bid committee members are the implementers of supply chain management policy. We do have skills and experience and knowledge, and we understand the timelines we ensure that we comply with the rules and regulations that govern supply chain.

Another participant during an interview added that:

Participant B: Not really because some of the staff in supply chain they were appointed according to their qualification.

Another participant during an interview echoed a different sentiment by noting with great concern that:

Participant A: I will be saying if you want me to answer this based on Mangaung supply chain management unit, then I will say this one doesn’t affect us because we are all skilled. We are all experienced and then we have the knowledge. In essence, if you employ someone to supply chain who doesn’t have the skills, who doesn’t have the experience anyway, not only in supply chain recruiting the function of that office, for instance, if you get a manager who doesn’t know supply chain to manage supply chain, and then it will be a difficult one because remember supply chain is one of the highly regulated environments.

Another participant during an interview noted that:

Participant Z: yes, there are people sometimes that are employed who do not have skills, and those people are easy to manipulate.

Another participant during an interview stated that:

Participant X: I’m saying that we need to have proper and relevant people at the right positions with knowledge and skills in a specific area of responsibility.

4.5. Payment of Suppliers

This theme has identified how participants perceive the non-payment of suppliers as a hindrance to service delivery. Participants noted that the inability and failure to pay suppliers on time is delaying the start of projects, therefore affecting service delivery. This theme relates to the first objective of this study as it identifies the challenges in SCM in the MMM. Mazibuko (Citation2020, pp. 1–9) has supported this claim by identifying those improvements needs to be done in contract management performance. All contractual obligations, in terms of the contract management oversight, should be resolved and funds in arrears should be paid within acceptable conditions. Mazibuko (Citation2020, pp. 1–9) further adds that the SCM policy in SA states that a supplier should be paid within 30 days and those 30 days will change into months and years without the organisations or hiring authority having made a payment to the service provider on time.

4.5.1. Payment of suppliers

Participants have mentioned the late or non-payment of suppliers. It has been noted by participant A, B, D and E that one of the challenges facing SCM is the late or non-payment of suppliers, which disadvantages the suppliers who are unable to work or pay their workers. Since the MMM is struggling to pay its suppliers, service providers are reluctant to do business with them. It has been noted by Glasser and Wright (Citation2020, pp. 413–441) that water pressure was reduced by Bloem Water, which affected the population of the MMM, because of an outstanding debt of R247 million, due by the MMM. In the case of MMM, the participants echoed the following sentiments:

Participant E: number one is the fact that this municipality is struggling to pay the suppliers. So, if you fail to pay the suppliers, and you request them again to do the job, they cannot and some because they heard that the municipality cannot pay. They don’t want to do business with this municipality.

It was further noted by a participant during an interview that:

Participant D: on the part of the municipality, or the government, we still slow to pay our service providers your budget would set out this financial year, this much for this project, maybe it’s a project that spans over three years, and then your budget is set up like that, from point A to B of the project, and you are going to pay this much, and then so forth and so on over the three years. Then in year two service provider is expected to deliver a good quality job but I have handicapped the service provider because I haven’t even paid the previous year’s money in full.

On the same note, during an interview, a participant noted that:

Participant B: If you are appointed and then you are expecting that after reaching this point, I must be paid and then I will need to pay my staff also, then if you don’t get paid to what you do, you put your project on hold.

It was also noted by a participant, during an interview that:

Participant A: The part which can be a challenge is from our side as the driver in terms of the law. Supplier’s must be paid within 30 days when the invoice was submitted but now when we take longer than the 30 days period, which is regulated. When we take longer, we are disadvantaging the suppliers, maybe two scenarios, one they won’t be able to comply with the agreement that they are going to work. If they are not paid, then they will have to get money from somewhere. Then it can create a problem for the suppliers. If they don’t get money. They are not able to work, 2). They are not able to pay their people on the ground.

4.6. Political interference

This theme has identified how participants perceive political interference. Participants noted that political interference in the access of tenders is affecting service delivery. There is interference through the appointments of political affiliated individuals who lack the knowledge and know-how of SCM processes. This theme relates to the first objective of this study, as it identifies the challenges in SCM in Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality. Munzhedzi (Citation2021, pp. 1–8) has supported this claim over concerns which have been raised of the high staff turnover rate of SA Accounting Officers, which is mainly linked with political interference. Munzhedzi (Citation2021, pp. 1–8) further adds that the term of these accounting officers is often defined by their association rather than expertise with their political instructors.

4.6.1. Political interference

Participants have mentioned that there is a lot of political interference. It has been noted by participants B, C, D, E and Z that decisions are passed from the top hierarchy with limited consultation with staff. Politicians are influencing appointments in SCM for their own interests, which is affecting service delivery. Siljeur (Citation2017, pp. 14–27) argues that public sector procurement has been plagued by incidents, such as lack of accountability, political interference, and appointment of inexperienced and unqualified officials and service providers. One of the participants during an interview echoed the following sentiments with great concern that:

Participant E: The first one I think would be political interference, I think mostly councillors. Mostly from the ruling party, because I believe that they just want to have a say, on the supply chain processes, sometimes who gets appointed and who does not get appointed and in terms of the service providers, but also in terms of the employment who they employee. I think they want somebody will be able to fulfil their mandate.

Another participant during an interview noted that:

Participant D: supply chain is the playground of politician’s supply chain is the place where everybody wants to show their power, whoever is in control of supply chain, in terms of politicians, and all those sectional managers. If I have a hold over supply chain, and I have my people will do things the way I want it, and I hold all the power. That hampers a lot in terms of service delivery.

During an interview, it was also noted by a participant that:

Participant C: The problem is the political interference for example, the city managers or the politicians will influence the appointment of supply chain management officials because they should have known that supply chain management officials and bid committee members, they are doing critical functions that affects service delivery.

On the same note, another participant echoed the following sentiments:

Participant B: we are in a political environment, and you know, some politicians, they take chances they can bring someone who’s not qualified, or they can use someone who’s qualified to focus on their interests.

Another participant during an interview added that:

Participant Z: a lot of interference. I think the space we are in, there’s a lot of politics. So even if people will not say, but sometimes if you get an instruction from somebody up there, other people, they will see they don’t have a choice, because it’s either you lose your job, or you do what you are told to do.

5. Implications, conclusions, and recommendations

The basics of SCM are the complexity theory, theory of constraints and resource-based theory and the system theory. It is recognised by the complexity theory that all systems function amongst order and disorder. Due to the participation of several role players, such as service providers, clients, technological improvements and government procedures, systems become complex (Nkwanyana & Agbenyegah, Citation2020, pp. 1–9).

5.1. Resource based theory

Nkwanyana and Agbenyegah (Citation2020, pp. 1–9) state that the Resource-Based View, also known as the RBT, implies to a set of resources, related to an organisation for a specific phase. These resources are not restricted to, but can include physical assets, skills, organisational procedures, and material. The aim of RBT is to improve roles and capabilities of these resources to expand SC associations and performance. Challenges in the application of public procurement practices in the Mangaung Metro Municipality SCM Department include features, such as poor enactment of procurement processes, lack of skills and capacity in the application of SCM, value of goods and services in the SC, and the delay and failure to pay suppliers that are applicable to all municipalities, including the district municipalities in the FS Province (Tshilo & Van Niekerk, Citation2016, pp. 109–126).

5.2. Theory of constraints

Some of the constraints found in the system are equipment, measures, strategies, work force, and process consistency and arranged work time. For an organisation to keep up to date of its restraints, it must classify restrictions in the structure, which may be supported via interior and exterior audit analyses/peer analyses (Nkwanyana & Agbenyegah, Citation2020, pp. 1–9). To substantiate this, the Auditor General (South Africa, 2019), states that in the Mangaung Metro Municipality SCM Department, over-dependence on individuals, was general practice. In illustration of such over-dependence, it led to the risk of the SCM unit being relocated, leading to an increase in cases of materials’ non-adherence with procurement regulation included in the audit statement, and in addition, the extent of irregular expenditure.

5.3. Justification of the RBV and theory of constraints

The study uses these two theories to obtain a better understanding of the challenges in SCM. The Resource-Based Theory is used to explain the relationship between suppliers, distributers, manufacturers within the SC and the host organisation. The theory of constraints is also adopted by the study to understand the importance of the participation of role-players in SCM for an organisation to keep abreast of its restraints as there is need for interior and exterior audit analysis/peer reviews.

Various recommendations were made from the research for challenges in SCM affecting service delivery for MMM. In order to establish approaches which overcome the challenges in SCM, there is need to come up with guidelines that better stabilise and control SCM. These are some of guidelines that the study makes:

5.4. Capacitate SCM

There is need to capacitate your SCM Department with enough human resources to allow for division of tasks and people who have the required skills. In turn, this would ensure that there are a fully fledged staff component and that people in SCM are not overburdened with work tasks which leads to low morale and demotivated staff. Having skilled people in SCM also ensures that there are less mistakes, which is very critical through application of SCM regulations. There is also needed encouragement for further improvements and in ensuring that positions in the SCM Department are filled; this is by advertising jobs and making sure they are filled.

5.5. Training

The lack of training, due to funds is an obstacle to the SCM Department. Training, mentorship, and seminars should therefore be carried out to train and increase employees’ awareness to issues, such as corruption and non-compliance with legislation. In addition, training should be done in the use of technology from moving from paper-based to a paperless system, so that work can be done even during weekends, leading to timely delivery of services.

5.6. Policies and legislation

The study recommends that there are changes needed to be done to legislation, as it is a hindrance. It has certain red tapes, in terms of the procuring of commodities and services. The issue is that by nature of procurement, above R200 000, it takes time to approve, because you may advertise for a certain time, and it has to go through all the three committees, which are the bid evaluation, specification, and adjudication committee. If the process is effective, it will take almost 3 months to finalise one tender. Legislation is too rigid and must be changed to allow the procurement to be below the R200 000 threshold, which would assist to finalise the procurement on time. National Treasury needs to review the current SCM regulations, so that they can give more time and space for departments and municipalities to procure, using the short time.

The study concluded that various factors have significantly contributed to the challenges in SCM affecting service delivery, comprising instability, lack of human capacity, lack of skills, lack of funds, lack of communication on the part of service providers, lack of monitoring, government officials and service providers. Through vetting of officials, moving from a paper-based to a paperless system and the monitoring of projects, these challenges can be reduced, therefore capacitating SCM and the training of staff, pertaining to SCM challenges, are also key.

6. Conclusion

The study concluded that various factors have significantly contributed to the challenges in SCM affecting service delivery, comprising instability, lack of human capacity, lack of skills, lack of funds, lack of communication on the part of service providers, lack of monitoring, government officials and service providers. Through vetting of officials, moving from a paper-based to a paperless system and the monitoring of projects, these challenges can be reduced, therefore capacitating SCM and the training of staff, pertaining to SCM challenges, are also key.

6.1. Limitations of the study

The limitations identified could be:

▸ Some participants did not provide the information wanted by the study, due to its high level of confidentiality and privacy and thus to mitigate this situation, this information was obtained through a review of related literature in the topic under study.

▸ Failing to conduct face-to-face interviews. This meeting was conducted face-to-face with strict adherence to COVID-19 regulations, which were applied through the wearing of masks and sanitising.

6.2. Suggested areas for further research

The study only concentrated in the MMM and did not cover other Metropolitan Municipalities in other Provinces. Moreover, it did not specifically look at the smaller district municipalities, which are part of the MMM.

There is need to investigate SCM challenges in other municipalities in the province. Research of this nature will be able to come up with a broad overview of the challenges in SCM and solutions.

Instability, due to political interference has subsequently culminated in the decline of the operational running of SCM Departments. Therefore, there is need to investigate the phenomena to understand the impact of instability and political interference has on the day-to-day activities of the SCM Departments and subsequently what can be done to address the challenge.

A comprehensive study on the challenges of service providers in ensuring effective service delivery in the local government sphere needs to be done. This will go a long way in identifying the trials confronting service providers, which ultimately undermines their potential to deliver effective services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tafadzwa. C. Maramura

Tafadzwa. C. Maramura is a Senior Lecturer and Researcher at the University of the Free State in the Economics and Management Faculty. Her research interests lie in sustainable service delivery and governance.

Joseph Munashe Ruwanika is a Master’s graduate in the Department of Public Administration and Management at the University of the Free State. His research interests lie in local governance, supply chain management and sustainable management of local municipalities.

References

- Adusei, C. (2018). Public procurement in the health services: Application, compliance, and challenges. Humanities and Social Sciences Letters, 6(2), 41–17. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.73.2018.62.41.50

- Andaneswari, A. K., & Rohmadiena, Q. (2020). The disruption of personal protection equipment supply chain: What can we learn from global value chain in the time of Covid-19 outbreak? Global South Review, 2(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.22146/globalsouth.63287

- Bimha, H., Hoque, M., & Munapo, E. (2020). The impact of supply chain management practices on industry competitiveness. A mixed-methods study on the Zimbabwean petroleum in industry. African Journal of Science Technology, 12(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2019.1613785

- Fourie, D. (2018). Ethics in municipal supply chain management in South Africa. Local Economy, 33(7), 726–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094218809598

- Fourie, D., & Malan, C. (2020). Public procurement in South African Economy: Addressing the systematic issues. Sustainability, 12(20), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208692

- Glasser, M. D., & Wright, J. (2020). South African Municipalities in financial distress: What can be done? Law, Democracy & Development, 24(1), 413–441. https://doi.org/10.17159/2077-4907/2020/ldd.v24.17

- Ikram, A., Su, Q., Fiaz, M., & Rehman, R. U. (2018). Cluster strategy and supply chain management: The road to competitiveness for emerging economies. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 25(5), 1302–1318. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-06-2015-0059

- Kusakana, M. N., Coetzee, M., & Oke, S. (2019). A proposed innovative framework to explore the communication challenges between bloemwater and the mangaung municipality. Proceedings of the Open Innovations Cape Town Conference, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Lunga, S. N., Lubbe, S., & Meyer, J. (2019). uMshwati Municipality’s procurement planning and its effect on service delivery. Journal of Public Administration, 54(3), 435–446. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC-1aaa11f44e

- Mafini, C., & Masete, M. (2018). Internal barriers to supply chain management implementation in a South African Traditional University. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 12(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v12i0.389

- Mantzaris, E. A. (2017). Trends, realities and corruption in supply chain management: South Africa and India. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(8), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC-ab5687741

- Mantzaris, E. A., & Ngcamu, B. S. (2020). Municipal corruption in the era of a Covid-19 pandemic: Four South African case studies. Journal of Public Administration, 55(3–1), 461–479. https://doi.org/10.10520/ejc-jpad-v55-n3-1a4

- Manzini, P., Lubbe, S., Kopper, R., & Meyer, J. (2019). Improvement of infrastructure delivery through effective supply chain management at North West provincial department of public works and roads. Journal of Public Administration, 54(1), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC-1a9f9fb55b

- Martinić, S., & Kozina, A. (2016). ‘Europe 2020’ and the EU public procurement and state aid rules: Good intentions that pave a road to hell? Croatian Yearbook of European Law & Policy, 12(12), 207–249. https://doi.org/10.3935/cyelp.12.2016.238

- Mathiba, G. (2020). Corruption, public sector procurement and Covid-19 in South Africa: Negotiating the New Normal. Journal of Public Administration, 55(4), 642–661. https://doi.org/10.10520/ejc-jpad-v55-n4-as

- Mazibuko, G. (2020). Public sector procurement practice: A leadership brainteaser in South Africa. Journal of Social and Development Sciences, 11(1 (S), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.22610/jsds.v11i1(S).3109

- Mhelembe, K., & Mafini, C. (2019). Modelling the link between supply chain risk, flexibility, and performance in the public sector. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v22i1.2368

- Munzhedzi, P. H. (2021). An evaluation of the application of the new public management principles in the South African municipalities. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2132

- Nkwanyana, N. S., & Agbenyegah, A. T. (2020). The effect of supply chain management in governance: Public sector perspectives. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v14i0.493

- Nyide, C. J. (2022). Municipal financial management practices for improved compliance with supply chain management regulations. Journal of Management Information & Decision Sciences, 25(1), 1–11.

- Parker, C., Scott, S., & Geddes, A. (2019). Snowball Sampling. SAGE Research Methods Foundations. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036831710

- Park, C. Y., Kim, K., & Roth, S. (2020). Global shortage of personal protective equipment amid COVID-19: Supply chains, bottlenecks, and policy implications (No. 130). Asian Development Bank, 130, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.22617/BRF200128-2

- Pauw, J. C., Van der Linde, G. J. A., Fourie, D., & Visser, C. B. (2015). Managing Public Money (3rd ed.). Pearson.

- Scharp, K. M., & Sanders, M. L. (2019). What is a theme? Teaching thematic analysis in a qualitative communication research method. Communication Teacher, 33(2), 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2018.1536794

- Shava, E., & Mubangizi, B. (2019). Social Accountability mechanisms in decentralised state: Exploring implementation challenges. African Journal of Governance and Development, 8(2), 74–93. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC-1a856be27d

- Sibanda, M. M., Zindi, B., & Maramura, T. C. (2020). Control and accountability in supply chain management: Evidence from a South African metropolitan municipality. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1785105

- Siljeur, N. (2017). Moving beyond traditional procurement to strategic sourcing in the public sector procurement in South Africa. Journal of Public Administration, 2(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC-b0841ac08

- Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2, 17–37. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526405555

- Tshilo, M., & Van Niekerk, T. (2016). The management of suppliers as part of municipal procurement management practices in district municipalities of the free state: A theoretical perspective. Interim: Interdisciplinary Journal, 15(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC6cf9ed817

- Van der Walt, G., Venter, A., Phutiagae, K., Nealer, E., Khalo, T., & Vyas-Doorgapersad, S. (2018). Municipal Management: Serving the People (3rd ed.). Juta and Company.

- Webb, W., & Auriacombe, C. J. (2006). Research design in public administration: Critical considerations. Journal of Public Administration, 41(3), 588–602. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC51480

- Zweni, A., Yan, B., & Juta, L. B. (2022). The malady of perpetual municipal-finance mismanagement: Designing a leadership framework as a Panacea. African Journal of Development Studies (Formerly AFFRIKA Journal of Politics, Economics and Society), 12(1), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.31920/2634-3649/2022/v12n1a9