?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines corporate tax aggressiveness captured by agency problem type 3. The results show that there are negative relations between corporate governance and tax aggressiveness. The findings provide evidence of agency conflicts between companies and tax authorities. A corporate governance mechanism can improve the quality of corporate financial reporting. The result also illustrates how corporate governance affects the actions of corporate tax aggressiveness at various levels by using regression quantile analysis. It is believed that corporate companies with high levels of aggressiveness will make the mechanism of corporate governance in the company to be more effective.

1. Introduction

The company is a profit-oriented entity (to gain as maximum profit as possible). As a taxpayer, the company has an obligation to pay taxes. As the subject of the tax in the country, the company is obligated to deposit taxes each period based on the profit earned. Therefore, the tax aspect becomes vital because the company has the intention/interest to manage the company’s finances so that companies can produce maximum profits (Minh Ha et al., Citation2021). Because the tax is considered a burden to the company, the company tends to minimize the tax burden. Efforts to minimize the company’s tax burden are often conducted by tax planning. Tax planning is a method or a way to minimize or streamline tax payments. Minimizing the tax burden can be legal in the corridors of taxation (tax avoidance) or illegal by breaking the applicable tax regulations (tax evasion) (Frank et al., Citation2009). The actions of tax avoidance and tax evasion carried out by the company are known as tax aggressiveness.

According to the existing literature, tax aggressiveness is defined as a tendency or intention of the company to minimize the burden of taxes by using a mechanism of tax avoidance and tax evasion. The actual act of tax aggressiveness is not wrong. As taxpayers, companies are interested in regulating the tax burden so that the company’s profit can be maximum. However, the issue is that tax planning carried out by the company often leads to actions tax planning that is illegal (tax evasion). Companies usually use illegal methods to minimize the burden of taxes, such as earning management, income smoothing, and transfer pricing (Kim et al., Citation2018).

The Ministry of Finance of Indonesia noted that the tax ratio in Indonesia still lags behind ASEAN countries, with tax ratios ranging from 15–17% (Hadi, Citation2012). The tax Ratio of Indonesia in 2006 was 13.02%, and it experienced a fluctuation over the following five years, reaching 12.59% in January 2011. The low tax ratio in Indonesia indicates that the compliance of taxpayers in Indonesia is low, suggesting that there are still many taxpayers in Indonesia that are aggressively against tax. A poll of tax professionals attending the International Tax Review’s Asia Tax Forum indicates that Indonesia occupies the second position behind India which is the most challenging country for tax audits (Haines, Citation2019). It indicates that tax authorities are becoming stricter because taxpayers tend to be less compliant.

Several factors influence tax aggressiveness. One of them is the company’s ownership structure (family or company rather than a family company). Since basically the tax burden also indirectly affects the owner of the stock, it is possible that, as a single unified whole company (the management and owners of the shares), the parties strongly contribute to the act of tax aggressiveness as policies in a company can be affected by a decision made by the owner of the shares and the management (Chen et al., Citation2010). In this research, it is agreed that the company takes the actions of tax aggressiveness as a united part (consisting of the shareholders and the management) because in the Asian region, especially in Indonesia, the structure of ownership of the company is dominated by the family company (Claessens et al., Citation2000).

Previous research describes this phenomenon as agency problem type 1. In contrast, these actions constitute a conflict of interest between the manager (as agent) and company owners (as principle) to maximize the incentives manager (Armstrong et al., Citation2015; Desai & Dharmapala, Citation2006). In comparison, this phenomenon should be viewed from the side of a conflict of interest between the company and the Government. It can be explained by the theory of agency type 3, that explain a conflict of interest between the government and the company (Armour et al., Citation2009). Tax authority (as the representation of the Government) cannot control the behavior of the opportunists from companies as taxpayers, such as companies manipulating financial statements for minimize tax payable.

Asymmetry of information becomes one of the reasons why the practice of tax aggressiveness of corporate still exists. Because of the asymmetry of information between the parties, the company and tax authority action opportunists to the company become difficult to detect. We need a mechanism to solve the problem of Agency between the company as agent and tax authority as a principle because this could cause a threat to the country’s tax revenues.

The mechanism of corporate governance could be a solution to solve the problem of agency’s problems. Corporate governance is the mechanism that explains the relationship between the various participants within the company that determines the direction of the company’s performance (Monks Robert et al., Citation2011, p. 11). Thus mechanism also give assure that the company will be fulfilled the stakeholders interest (Khan et al., Citation2022). A company is a taxpayer; therefore, a corporate governance structure affects how a company fulfills the obligations of its taxes and tax planning in companies (Friese et al., Citation2008). In brief, four main components are necessary for the concept of corporate governance, i.e., fairness, transparency, accountability, and responsibility. The fourth component is important because the application of the principles of corporate governance is consistently shown to improve the quality of financial reporting (Beasley, Citation1996). Increasing the quality of profits in an enterprise’s financial statements indicates that the company’s financial report describes the actual financial state of the company, so this will lower the risk of the company committing aggressive actions against tax.

This article gives some contributions toward the novelty and evidence of tax aggressiveness. First, previous research only identified the tax aggressiveness framed by the Agency theory without clearly explaining the type of agency and what the appropriate way to describe the corporate tax aggressiveness. Therefore, this article aims to examine the phenomenon of corporate tax aggressiveness using agency theory type 3. Second, the results of previous studies showed inconsistent results. On the one hand, corporate governance has been identified as an important variable explaining variation in tax aggressiveness (Armstrong et al., Citation2015; James & Igbeng, Citation2014). However, the results of empirical research show that the influence between corporate governance and tax aggressiveness is still not conclusive. Some researchers found that corporate governance variables do not affect tax aggressiveness (Khaoula, Citation2013; Kurniasih & Sari, Citation2013; Maharani & Suardana, Citation2014), while others found that corporate governance negatively influences tax aggressiveness (Armstrong et al., Citation2015; Darmawan & Sukartha, Citation2014; Desai & Dharmapala, Citation2006; Fernandes et al., Citation2013; James & Igbeng, Citation2014; Minnick & Noga, Citation2010). In this regard, for further analysis, this article aims to provide evidence about the influence of corporate governance on a different level of tax aggressiveness to explain the inconsistent result in previous studies. This study provides an alternative development model for subsequent studies. Measurement differences include corporate governance index to measure corporate governance. Furthermore, the difference in using the term phenomenon, such as tax avoidance becoming tax aggressiveness, is to describe the phenomenon more comprehensively.

2. Literature review

The issue of opportunist actions that arises because of a conflict of interest between the government, in this case, represented by the tax authority, and the company, is called an agency problem. Agency relationship type 3 describes the relationship between the company and third parties (in this case, tax authority as a government representation) (Armour et al., Citation2009). The government legally has the right to collect taxes from companies, but companies often do not run their obligations to pay taxes. The act of opportunistic company in conducting tax aggressiveness is caused by the asymmetry of information between tax authority and company. Corporate governance mechanisms are needed to reduce the asymmetry of information.

This article refers to the previous research conducted by Desai and Dharmapala (Citation2006), namely research on tax avoidance. The results showed that corporate governance (described by the corporate governance perception index) has negative effects on tax avoidance (described by book-tax difference). Good corporate governance is a system for regulating and controlling the companies to create values added to stakeholders (Desai & Dharmapala, Citation2006).

Agency theory type 3 is used to describe the behavior of corporate tax aggressiveness because Asian companies, especially in Indonesia, are defined as family companies (Claessens et al., Citation2002). Thus, agency problems used in previous studies, such as Desai and Dharmapala (Citation2006) and Armstrong et al. (Citation2015), are not suitable to be applied in this study which is dominated by family companies. In this study, corporate tax aggressiveness is an opportunist act of the company (the company as a single shareholder and manager) to minimize the tax burden that creates a conflict of interest with the government represented by the tax authority. Because of this consideration, researchers do not use incentive managers as one of the determinants in investigating the phenomenon of tax aggressiveness.

2.1. Corporate governance and tax aggressiveness

Tax is generally defined as a liability by companies, so they always try to minimize the tax burden to maximize the profits for the company (Wahab et al., Citation2015). Since tax aggressiveness increases benefit cash flows, tax aggressiveness can be seen as one of the opportunities to maximize profit (Kovermann & Velte, Citation2019). According to the law, the government has the right to collect taxes based on the company’s profit. Tax authority often has difficulties detecting opportunistic actions of companies, such as committing tax evasion, due to the asymmetry of information between tax authority and company. The tax authority cannot control the opportunistic action done by the company, so it is possible if there is misleading information between the tax authority and the company about the financial statement provided by the company (for example, tax authority cannot detect the manipulation of a financial statement given by the company). Corporate tax aggressiveness is an opportunist act of the company (the company as a single shareholder and manager) to minimize the tax burden that creates a conflict of interest with the government represented by the tax authority. Because of this consideration, researchers do not use incentive managers as one of the determinants in investigating the phenomenon of tax aggressiveness.

There is a need for a mechanism to reduce the information asymmetry between tax authorities and companies. During the early 2000s in America, IRS (Internal Revenue Service), Congress, dan SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) were improving standard firms’ tax and financial reporting and corporate governance system. Tax authorities as a regulator aimed to create stricter reporting requirements to reduce the opportunity for corporate tax avoidance (Jiménez-Angueira, Citation2018). Corporate governance schemes allegedly can be used to reduce the asymmetry in this issue since the governance is a scheme that provides more added value for stakeholders (Desai & Dharmapala, Citation2004). From previous study it is expected that the existence of good corporate governance will lower the company’s tendency to act aggressively against tax.

The application of the principles of corporate governance is consistently shown to improve the quality of financial reporting (Beasley, Citation1996). Increasing the quality of profits in an enterprise’s financial statements indicates that the company’s financial report describes the actual financial state of the company, so this will lower the risk of the company committing aggressive actions against tax (Graham et al., Citation2014). High quality of financial reporting allows firms to achieve lower ETRs without increasing the risk of their tax strategies (Gallemore & Labro, Citation2015). Based on these explanations, the hypothesis in this study is:

H1

Corporate governance affects negatively to the aggressiveness of the taxes.

2.2. Corporate governance on different tax aggressiveness level

The results of previous studies that showed inconsistent results might suggest that corporate governance mechanisms may be inefficiently applied to companies with a certain level of tax aggressiveness. The results study of Armstrong et al. (Citation2015) explains that it is possible for corporate governance to have a stronger influence on corporate companies with a higher level of tax aggressiveness. Companies with a high level of tax aggressiveness need a better corporate governance mechanism to deal with the risks of aggressive tax actions. Based on these explanations, the research hypothesis in this study is:

H2

Corporate governance has a stronger influence on companies with a high level of tax aggressiveness than the lower level of tax aggressiveness

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

The population in this study is all the manufacturing companies listed on the Indonesia stock exchange (IDX). The researchers chose manufacturing companies as objects of research as they are companies that sell products from an uninterrupted production process, starting from the purchase of raw materials and processing of materials until finished goods. It shows the high level of the company’s operations, indirectly describing the size of a large company (Bujaki & Richardson, Citation1997). Manufacturing companies have high operating levels and process, so it is possible to perform the tax because the aggressiveness of large companies has organized internal procedures and more diverse working relationships.

The sampling method used in this research is purposive sampling. Purposive sampling is a method of taking population samples based on certain criteria. The criteria for selecting the sample are as follows:

1. Manufacturing companies registered in Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) consecutively from 2013 to 2017. The reason for selecting this period is that in 2012 the IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) convergence was fully implemented and thus several aspects of changes related to corporate financial reporting will possibly affect corporate income tax in the following years.

2. Companies that conducted transactions with related party sales during years of research, and companies that have positive earnings during years of research.

3. Companies that have positive earnings during years of research. The criteria were intended to avoid biased calculations towards the level of an effective tax rate of the company.

4. Companies that disclose financial statements denominated in rupiah. They were to prevent the occurrence of bias when differences in exchange rates cause the measurement variables.

5. Finally, according to the earlier criteria, this study observed 205 firms (2013–2017).

3.2. Variables and measurements

The variables used in this study consist of one independent variable, corporate governance, and the dependent variable, tax Aggressiveness. To create the research model BLUE (Best Linear Unbiased Equation), researchers add control variables such as related party transaction, profitability, firm size, and leverage. Further descriptions of the variables in this study are as follows:

3.3. Corporate governance

The corporate governance index is a measure used to describe whether corporate governance has been appropriately applied or not. Some aspects must be met to realize the implementation of good corporate governance. Desai and Dharmapala (Citation2004) used a proxy index of corporate governance for the measurement of the implementation of corporate governance within the company. In this study, the measurement of corporate governance using CGPI (corporate governance perception index issued by Forum for Corporate Governance in Indonesia) provides a corporate governance scoring list for each corporate (total score between 0–100).

3.4. Tax aggressiveness

Tax aggressiveness is an effort made by the taxpayer (company) to minimize the tax burden through a tax planning mechanism (Hanlon & Heitzman, Citation2010). Increasingly, companies use taxation loopholes to maximize tax savings; then, the company is considered to have committed acts of aggressive tax, although the action does not violate the rules. Tax aggressiveness in this study uses proxy ETR (Effective Tax Rate) and CETR (Cash Effective Tax Rate). ETR (Effective Tax Rate) and CETR (Cash Effective Tax Rate) are measures of the results based on the income statement and generally measure the effectiveness of the strategy and direct tax reduction on profit after tax (Minnick & Noga, Citation2010). The greater the value of ETR and CETR of the company, the less tax aggressiveness (reverse interpretation). Formulas for each proxy were as follow:

3.5. Transactions with related parties

Transactions with related parties are the transactions between companies and parties that have a special relationship with the company, such as a subsidiary or company owned by the members of the Board. The transactions used are transactions for the sale because the sale is one of the aspects used in the calculation of the amount of the income tax of a company. Companies that made transaction with related party is tend to carry out transfer pricing for tax purposes (Mashiri et al., Citation2021). The proxy used for RPT (Related Party Transactions) is RPT sale (Related Party Transactions) based on studies by Lo et al. (Citation2010). The formula for RPT proxy was as follow:

3.6. Firm size

Firm size describes the size of an enterprise that can be seen from total assets or total net sales (Bujaki & Richardson, Citation1997). The company’s size is the company’s characteristic that also affects the amount of income tax paid. The size of the company directly reflects the level of operating activity of a company. In General, the larger the company, the greater the operational activity. Large companies have organized internal procedures and various working relationships.

The larger the company size, the smaller the ratio between the tax burden to be paid and the net income before taxes, known as an Effective Tax Rate (Richardson & Lanis, Citation2007). The size of the company describes the size of an enterprise that can be seen from total assets or net sales. A proxy used to measure the company’s size is the total asset logarithm. Proxy of the company size refers to research by Hartadinata and Tjaraka (Citation2013).

3.7. Profitability

In each of the company’s operations, the main objective of its business is to make a profit or profitability. Profitability can be measured using the Return on Assets (ROA) ratio. They contend that more profitable firms have more motivations to generate tax savings and firm capability to engage in tax aggressiveness (Richardson et al., Citation2015). The formula for ROA proxy was as follow:

3.8. Leverage

The leverage ratio is used to describe the use of debt to finance a portion of the corporation’s assets. The company’s leverage level can explain the financial risk of the company. It is because leverage is a tool to measure how significant a company’s dependence on creditors is in financing company assets. Financing with debt influences corporations because debt has fixed costs. Leverage demonstrates how much corporate debt is used to finance a company’s assets. The corporate is more aggressive as the higher its level of leverage. It is because corporate debt increases interest expenses, which lowering the corporate’s earnings before taxes (Ledewara et al., Citation2020). Leverage is defined as total debt divided by total assets (Jin, Citation2021). The formula for Leverage proxy was as follow:

3.9. Research framework and regression analysis

Based on the description of the research model, the theoretical framework can be described as follows (Figure ):

This study used multiple regression and regression quantile analysis. Thus in the hypothesis testing, the regression equation will be analyzed in two stages using STATA software analysis (the first stage using multiple regression analysis and the second stage using regression quantile analysis). Regression equation formulas in this study were as follows:

Effective Tax Rateit = α + β1.Corporate Governanceit + β2.Related Parties Transactionit + β3 Firm Sizeit + β4 Return On Assetsit + β5 Leverageit + ε

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Descriptive analysis

Table presents the descriptive analysis of each variable’s mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values. In general, the mean value of each variable shows an amount greater than the standard deviation value, which indicates a small variation between the minimum value and the maximum value. Small variation values suggest that there are no data out layers in each variable in general.

Table 1. Descriptive statistic

4.2. Inferential analysis

Table Panel A presents our primary results regarding the relationship between corporate governance and tax aggressiveness. We first mention the relation between corporate governance (measured by the corporate governance index) and tax aggressiveness. MRA estimates the conditional level of tax aggressiveness presented in Panel A of Table , showing evidence of a relationship between tax aggressiveness and CG index. Specifically, the estimated coefficient is 0.01164 (t-stat of 4.21. Meanwhile, the tax aggressiveness is measured with ETR and 0.01322 (t-stat of 3.07), and the tax aggressiveness is measured as CETR. Although the results of statistical tests show a positive influence between corporate governance and tax aggressiveness due to the opposite interpretation of ETR and CETR values (the greater the value of ETR and CETR of the company, the less tax aggressiveness of the company), the positive influence is considered to be a negative or opposite effect. This positive influence shows that corporate governance is proven to reduce the level of corporate tax aggressiveness. This result is inconsistent with xxx, which stated there is no relation between corporate governance (measured by Log CEOPortDelta and Log CEOPortVega) and tax avoidance (measured by EndFin48Bal and TAETR). This result also provides a variety of relationships between corporate governance and tax aggressiveness with different measurements.

Table 2. Inferential statistic

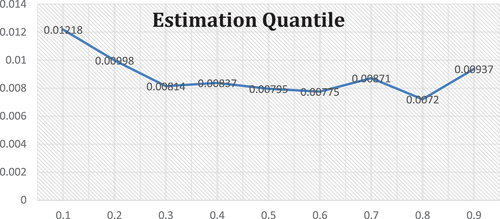

In Table , panel A, the quantile regression coefficient estimate (when ETR measures tax aggressiveness) showed that the relation between corporate governance and tax aggressiveness is generally positive. Still, the right tail distribution does not increase. Tests of differences in coefficients across the quantiles when ETR measures tax aggressiveness indicate that the coefficient at the 90th percentile (p-value of 0.116) is not significantly greater than the coefficient at the 50th percentile (p-value of 0.000). On the other hand, it is also not considerably larger than the coefficient at the 10th percentile (p-value of 0.135). Moreover, the result shows that the corporate governance mechanism is more effective with a higher level of corporate tax aggressiveness (reverse interpretation). Furthermore, the quantile regression coefficient estimates provide evidence that corporate governance has a more substantial effect on a higher level of corporate tax aggressiveness.

Figure and Figure show the trend of coefficients of each quantile regression. From the figure, it can be concluded that the regression quantile coefficient value decreases, corresponding to the decrease in tax aggressiveness. It is in accordance with the quantile regression test table that has been done, which shows that corporate governance has a more significant influence on companies with a high level of tax aggressiveness.

Figure 3. Estimation coefficient in various quantile (CETR).

5. Discussion

The results of the current study illustrate how corporate governance mechanisms affect corporate tax aggressiveness at different levels. It is believed that corporate companies with high levels of aggressiveness will make the mechanism of corporate governance in the company to be more effective. The reason is companies with better corporate governance are also big companies that have enormous resources. More prominent companies may have the ability to carry out good tax planning so that the company will comply with applicable tax regulations. The results of this study are consistent with the results of research conducted by Desai and Dharmapala (Citation2006) and Armstrong et al. (Citation2015), which shows that corporate governance has a stronger influence on companies with a high level of tax aggressiveness.

In addition, the control variables used in the study such as related party transactions, leverage, and profitability provide evidence for the company’s tax aggressiveness. Companies have a tendency to be more aggressive towards taxes through several ways, such as making transfer prices with affiliated companies and made thin capitalization to increase the company’s interest expense. This provides empirical evidence that the company’s tax aggressiveness is a part of the company’s financial strategy to minimize the company’s tax burden.

In general, corporate governance can be used as a solution to overcome the phenomenon of corporate tax aggressiveness. It is consistent with the research of Desai and Dharmapala (Citation2006) and Armstrong et al. (Citation2015) which state that corporate governance is one of the determinants in the tax avoidance phenomenon. In this way, corporate governance can be used as one solution to overcome the actions of corporate tax aggressiveness. The results of this study solve agency type 3, which occurs between the company and the tax authority.

Companies with a high level of tax aggressiveness may have competent resources. Hence, a big company has an excellent corporate governance system and the ability to conduct tax aggressiveness. Because tax management actions pose high risks for companies, such as being subject to sanctions from the tax authority and experiencing the decrease in the company’s image, companies must be able to ensure their resources can conduct tax aggressiveness to overcome those risks.

In addition, companies that have affiliates abroad tend to be carry out transfer pricing by taking advantage of differences in tax rates between countries. Transfer pricing is carried out by shifting company profits in countries with high tax rates to affiliated companies in other countries with lower tax rates. Therefore transactions with related parties are beneficial for companies to be able to carry out tax aggressiveness efforts, especially companies that have affiliations with companies in tax haven countries.

The results of the study also provide empirical evidence about the agency theory that occurred in Indonesia. With ownership structures dominated by family companies resulting in type 1, agency conflicts (agency conflicts between shareholders and managers) do not occur in companies in Indonesia. As a family company do not separate between the manager and the company owner, agency conflicts that arise more often are type 3 agency conflicts (agency conflicts between companies and third parties) developed by Armour et al. (Citation2009).

Agency conflicts type 3 occur between companies and third parties. The third party, in this case, is the tax authority interested in maximizing state tax revenues. On the other hand, the company wants to minimize the tax burden as low as possible. A corporate governance mechanism can improve the quality of corporate financial reports, which will later be used to calculate the amount of corporate tax that must be paid to the government. With a corporate governance mechanism, the company is directed to carry out tax planning efforts per the applicable tax regulations.

6. Conclusion

The results of the study show that the corporate governance mechanism can be a solution to overcome the actions of corporate tax aggressiveness. This is consistent with the results of research conducted by Desai and Dharmapala (Citation2006) and Armstrong et al. (Citation2015) which illustrate that corporate governance mechanisms can reduce the tendency of companies to take tax avoidance actions. Also, this study proves that the mechanism of corporate governance can improve the quality of corporate financial statements so that the company’s financial statements describe the actual financial situation of the company.

Furthermore, this research implication also gives evidence toward agency theory type 3 about agency conflicts that occur between companies (agents) and third parties (tax authority). The third party, in this case, is the tax authority interested in maximizing the government’s tax revenues. The existence of a corporate governance mechanism can improve the quality of corporate finances. With a corporate governance mechanism, the company is directed to carry out tax planning efforts per the applicable tax regulations. The regulator should improve the require standard of corporate governance implementation as part of increasing transparency.

This study uses a sample of companies in countries that apply voluntary corporate governance disclosures. For further research, there is need to examines the aggressiveness of corporate taxes in countries that apply mandatory corporate governance disclosure.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bani Alkausar

Bani Alkausar is lecture and researcher at Faculty Vocational Studies, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia. He is also managing TIJAB Journal (The International Journal of Applied Business). His research interest includes Accounting & Taxation, Corporate Governance, Tax Evasion, Tax Compliance Behaviour.

References

- Armour, J., Hansmann, H., & Kraakman, R. (2009). Agency problems, legal strategies, and enforcement. NELLCO Legal Scholarship Reporitory, 644(21), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.d7634

- Armstrong, C. S., Blouin, J. L., Jagolinzer, A. D., & Larcker, D. F. (2015). Corporate governance, incentives, and tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 60(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2015.02.003

- Beasley, M. S. (1996). Empirical analysis the of board the relation of financial between composition statement fraud. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 443–465. http://www.jstor.org/stable/248566

- Bujaki, M. L., & Richardson, A. J. (1997). A Citation Trail Review of the Uses of Firm Size in Accounting Research. Journal of Accounting Literature, 16, 1–27. www.proquest.com/openview/2c20eea8ed6c69966ccfe56b8cae2c37/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=31366

- Chen, S., Chen, X., Cheng, Q., & Shevlin, T. (2010). Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family firms? Journal of Financial Economics, 95(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2009.02.003

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S., Fan, J. P. H., & Lang, L. H. P. (2002). Disentangling the incentive and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2741–2771. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00511

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Lang, L. H. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00067-2

- Darmawan, I. G. H., & Sukartha, I. M. (2014). Effect of corporate governance implementation, leverage, return on assets, and company size on tax avoidance. E-Jurnal Akuntansi Universitas Udayana, 1, 143–161. https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/akuntansi/article/view/8635

- Desai, M. A., & Dharmapala, D. (2004). Corporate tax avoidance and high powered incentives. Journal of Financial Economics, April, 42. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.532702

- Desai, M. A., & Dharmapala, D. (2006). Corporate tax avoidance and high-powered incentives. Journal of Financial Economics, 79(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.02.002

- Fernandes, V. L., Martinez, A. L., & Nossa, V. (2013). The influence of the best corporate governance practices on the allocation of value added to taxes. A Brazilian case contabilidade, gestão e governança. Brasilia, 16(3), 58–69. https://www.revistacgg.org/index.php/contabil/article/view/535

- Frank, M. M., Lynch, L. J., & Rego, S. O. (2009). Tax reporting aggressiveness and its relation to aggressive financial reporting. The Accounting Review, 84(2), 467–496. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2009.84.2.467

- Friese, A., Link, S., & Mayer, S. (2008). Taxation and corporate governance — the state of the art. Tax and Corporate Governance, 357–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-77276-7_25

- Gallemore, J., & Labro, E. (2015). The importance of the internal information environment for tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 60(1), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.09.005

- Graham, J. R., Hanlon, M., Shevlin, T., & Shroff, N. (2014). Incentives for tax planning and avoidance: Evidence from the field. The Accounting Review, 89(3), 991–1023. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50678

- Hadi, W. (2012). What is Indonesia‘s Tax Ration. Direktorat Jenderal Pajak. http://www.pajak.go.id/content/article/berapa-sih-sebenarnya-tax-ratio-indonesia

- Haines, A. (2019). South-East Asian countries get increasingly aggressive. International Tax Review. 4(1), 1–7. https://www.internationaltaxreview.com/article/2a69yqg68jglxqxc3kvls/south-east-asian-countries-get-increasingly-aggressive

- Hanlon, M., & Heitzman, S. (2010). A review of tax research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 127–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.09.002

- Hartadinata, O. S., & Tjaraka, H. (2013). Analysis of the effect of managerial ownership, debt policy, and company size on tax aggressiveness in manufacturing companies on the Indonesia stock exchange period 2008-2010. Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Bisnis, 3(3), 48–59. https://doi.org/10.20473/jeba.V23I32013./25p

- James, O. K., & Igbeng, E. I. (2014). Corporate governance, shareholders wealth maximization and tax avoidance. Research Journal of Finance & Accounting, 5(2), 2012–2015. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/RJFA/article/view/10686/10891

- Jiménez-Angueira, C. E. (2018). The effect of the interplay between corporate governance and external monitoring regimes on firms’ tax avoidance. Advances in Accounting, 41(March), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2018.02.004

- Jin, X. (2021). Corporate tax aggressiveness and capital structure decisions: Evidence from China. International Review of Economics & Finance, 75(April), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2021.04.008

- Khan, N., Abraham, O. O., Alex, A., Eluyela, D. F., & Odianonsen, I. F. (2022). Corporate governance, tax avoidance, and corporate social responsibility: Evidence of emerging market of Nigeria and frontier market of Pakistan. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2080898

- Khaoula, A. (2013). Does corporate governance affect tax planning? Evidence from American companies. International Journal of Advanced Research, 1(10), 864–873. http://www.journalijar.com/uploads/2014-01-01_113753_520.pdf

- Kim, B., Park, K. S., Jung, S. Y., & Park, S. H. (2018). Offshoring and outsourcing in a global supply chain: Impact of the arm’s length regulation on transfer pricing. European Journal of Operational Research, 266(1), 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.09.004

- Kovermann, J., & Velte, P. (2019). The impact of corporate governance on corporate tax avoidance—A literature review. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 36, 100270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2019.100270

- Kurniasih, T., & Sari, M. M. R. (2013). Effect of return on assets, leverage, corporate governance, company size and fiscal loss compensation on tax avoidance. Buletin Studi Ekonomi, 18(1), 58–66. https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/bse/article/view/6160

- Ledewara, A. G. M. N., Kristanto, A. B., & Rita, M. R. (2020). A trade-off between tax reporting and financial reporting aggressiveness based on financial variables. Jurnal Keuangan dan Perbankan, 24(3), 326–339. https://doi.org/10.26905/jkdp.v24i3.4018

- Lo, A. W. Y., Wong, R. M. K., & Firth, M. (2010). Can corporate governance deter management from manipulating earnings? Evidence from related-party sales transactions in China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2009.11.002

- Maharani, I. G. A. C., & Suardana, K. A. (2014). The effect of corporate governance, profitability and executive characteristics on tax avoidance of manufacturing companies. E-Jurnal Akuntansi, 2(9), 525–539. https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/akuntansi/article/view/9290

- Mashiri, E., Dzomira, S., Canicio, D., & McMillan, D. (2021). Transfer pricing auditing and tax forestalling by Multinational Corporations: A game theoretic approach. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1907012

- Minh Ha, N. M., Tuan Anh, P., Yue, X. G., Hoang Phi Nam, N., & Ntim, C. G. (2021). The impact of tax avoidance on the value of listed firms in Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1930870

- Minnick, K., & Noga, T. (2010). Do corporate governance characteristics influence tax management? Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(5), 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2010.08.005

- Monks Robert, A. G., Minow, N., Monks, R. A. G., & Minow, N. (2011). Corporate governance. (Fifth Edit). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119207238

- Richardson, G., & Lanis, R. (2007). Determinants of the variability in corporate effective tax rates and tax reform: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 26(6), 689–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2007.10.003

- Richardson, G., Lanis, R., & Taylor, G. (2015). Financial distress, outside directors and corporate tax aggressiveness spanning the global financial crisis: An empirical analysis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 52, 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.11.013

- Wahab, N. S. A., Holland, K., & Soobaroyen, T. (2015). Do UK outside CEOs engage more in tax planning than the insiders? Jurnal Pengurusan, 45, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.17576/pengurusan-2015-45-11