ABSTRACT

Leaders play crucial roles in their enterprises. Most modern organizations today, such as corporations and government departments, have no leaders. About 80% of all organizations have no top structures, and are run by inertia as leaderless organizations. These organizations have pretense-pseudo structures and filled roles, such as CEO, Department Head/Secretary, EVP, VP, and others, but this non-accountable system mostly harms than benefits the organization and its stakeholders. When the eventual crisis unfolds, often because the façade setup has failed to properly prepare the organization for the future, these “leaders” cut resources and lower-level roles out of the organization to continue in the downfall. Sometimes, they even sacrifice their own citizens.

1. Introduction

I say, then, that hereditary states, accustomed to the line of their prince, are maintained with much less difficulty than new states. For it is enough merely that the prince does not transcend the order of things established by his predecessors, and then to accommodate himself to events as they occur. So that if such a prince has but ordinary sagacity, he will always maintain himself in his state, unless some extraordinary force should deprive him of it.

Niccolo Machiavelli

Today’s world is extraordinary and unstable. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists estimates the world to be 90 seconds to midnight (2023), the closest it has ever been to a world catastrophe. The global coronavirus pandemic, war in Ukraine, fluctuating oil prices, inflation, political instability in many countries make it hard to argue the opposite view. Taleb (Citation2010) goes further and argues that the world has always been unstable, impacted by his unrelenting and unpredictable Black Swans, which are events that are hard to impossible to predict, but which have extreme impact on societies. Coronavirus pandemic is one of the most recent examples of such an event, along with the war in Ukraine, baby formula and medications shortage in the United States, and many other local, national, and worldwide presently-unfolding events. Today, even the physicists are dismayed at the kilogram losing its weight (2007, 2018), further exemplifying that even the items that we have assumed to be stable and constant, in their true nature are changing. The world we live in, fundamentally, is unstable and unpredictable.

Dwivedi (Citation2022), and others explore leadership, dreaming of a better future, different from today. Farooq (2023) discusses deviant behavior in organizations, and their destructive and harmful impact. Mastio et al. (Citation2021) goes further, describing inertia in modern organizations.

Machiavelli (Citation1505) argues that his prince—the modern CEO—must be capable to handle the complexity of work in the role. Machiavelli writes that if the CEO is ordinary, he or she could probably manage and endure in a stable environment. However, if the environment is unstable, to survive, the CEO must be capable. Today’s environment is clearly unstable.

2. Organizational theory

Chandler (Citation1977) presented and described the early development of the modern—hierarchical – organizational structure that he argues began in the mid-18th century, after the Industrial Revolution. Other scholars have contributed to the description of the hierarchical organizational structure, which has fundamentally not changed since the mid-18th century. Many scholars, most notably Chomsky (Citation2019), reason that the organizational hierarchy—in its core—is a totalitarian system, and therefore, is unstable.

After the World War II, Wilfred Brown, a managing director of the Glacier Metal Company in the United Kingdom, in his search for a more democratic organizational structure, sponsored research by EBrown and Jaques (Citation1965). Jaques, a known psychoanalyst and member of the British Psychoanalytical Society, and at the time interested in group dynamics in the organization, undertook the project, and what he believed, made new scientific discoveries in the organizational structure (1979), and continued his research into the organizational systems, proposing new ideas on information and work complexity (2002). Jaques (Citation2002b) believed that the hierarchical system could function more effectively if properly – requisitely – designed.

Today, most organizations are hierarchical. These include corporations, government organizations, universities, and others. Hierarchical means that there are bosses (managers, higher-ups) and subordinates. Some exceptions are small partnerships, families, and other member-based associations. Chandler (Citation1977), and several other scholars note that until the switch to a larger hierarchical structure in the mid-19th century, all organizations had no middle-management, and were largely operated by owners. Today, few organizations are operated by owners, except for new start-ups, and small businesses. Most larger organizations operate by hired managers, world-wide. These managers may be called Presidents, CEOs, Deans, Vice Presidents, amongst other titles.

The premise of Jaques’ organizational theory, which he called Requisite Organization Theory (1997), and later renamed as the General Theory of Managerial Hierarchy (GTMH), extended Chandler’s organizational theory. Jaques found that not only most organizations are hierarchical, but these hierarchies also operate by certain theoretical laws and principles, which Jaques (Citation1966, Jaques, Citation2002a) and others have attempted to articulate, discover, formulate, and confirm.

Following Jaques’ newly-discovered organizational theory (any theory of about 20 or so years is a young theory), Jaques himself, and other independent scholars conducted a variety of organizational studies, and confirmed the basic findings and tenets that Jaques has claimed to have discovered. Among these other scholars, most notable are G. Kraines (Citation2021), Lee (Citation2017), Clement (Citation2015), Vrekhem and Fabiaan (Citation2015), Al Amiri (Citation2020), and others.

3. Major tenets of Jaques’ organizational theory

The major tenets of the Jaques’ organizational theory are that the hierarchical structure of all large organizations has many special, distinct, and definable management levels, for a reason. Jaques’ contributions are that he articulated, measured, and explained each level of the managerial hierarchy in terms of time and complexity of work.

The larger the organization, the more management levels it has. Jaques (Citation1969, Citation2002) discovered the instrument that measures the work complexity of all organizational roles, in a fairly clear, elegant, and unambiguous way. He called this instrument time-span of the role (or time-span of discretion). Timespan identifies the longest actual task in the role, as assigned by the manager to the subordinate, such as to get something done—tasks – in 3 months, 9 months, 1 year, 5 years, etc. The more complex the role is, the longer is its timespan, or time to complete a task or a set of tasks, as approved by the higher-up manager. For example, there is a difference in complexity in writing a college paper that is due next week from writing a sophisticated book, the endeavor of which may take years or even decades to complete.

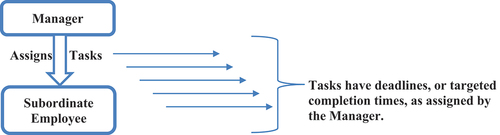

In the organization, the manager always decides and approves the tasks assigned to the subordinate employees. Many of the tasks are assumed, preapproved, or embedded within a role; nonetheless, it is the manager who has approved them and their targeted (expected) completion times. In the hierarchy, no employee can come up with an independent task and commit organizational resources, especially time, other employees, money, and other resources, towards the completion of his or her own objectives. In many organizations, many employees have experienced dysfunctional systems with multiple managers and supervisors assigning different—and occasionally—contradictory – tasks; however, a task or a group of tasks is always either approved, pre-approved, or handed down from the employee’s manager(s), as follows in Figure here:

All tasks have deadlines. An example of a task could be to prepare a budget, conduct an analysis, complete a project—all within a specified and expected timeframe. All managers expect certain targeted completion times within which a particular task or a set of tasks that must be completed. Jaques, Kraines, Lee, Clement, Van Vrekhem, and others have measured roles in organizational hierarchies—worldwide, identifying longest tasks (2021, 2017, 2015, 2015, 2002). The longer the task, the more complex the role is. For example, a surgeon may perform a highly-complex surgery within a short time-period of time, even in minutes. However, longer tasks in his or her role would be the entire patient treatment and recovery, learning new methodologies, retraining to a certain new technology, recertification, and others, which occasionally may take years.

Having been able to measure each organizational role for work complexity, Jaques, myself, and other scholars, independently traversed various organizations and measured roles for complexity. Jaques (Citation2002) identified—what he called and found—a universal organizational structure by levels that anyone would be able to find and verify in any hierarchical organization, irrespective of the location, culture, language, and other factors. Popper (Citation2002) would be pleased that any scholar or practitioner can now verify and test the developing theory, and possibly refute it.

Jaques claimed and found that all hierarchical organizations consist of eight and only eight levels (or less), distinctly identifying and describing each level (stratum) of work. World’s largest organizations have eight levels of work, irrespective of the size of the company. Smaller organization, because of their smaller size and scope, may not have the highest levels of work, but if these organizations grow, eventually, they may fill the higher levels of work, in strata 5, 6, 7, and 8, as follows Table :

Table 1. Universal structure of the Hierarchical Organization as Discovered by Dr. Elliott Jaques

Organizational roles grow in work complexity from stratum (level) 1 to 8, where the top leadership roles normally reside, in the highest levels of work, assuming the highest complexity. In the level 1 role, the person works with the concrete and immediate future and results, often at the front-line, such as entering data into the HR system, working with customers, or procuring a product. Level 2 role is usually the role of a first-line manager, who has objectives to achieve within a fiscal year. Level 3 role is typically of a project manager, whose longest task may be to secure funding for a project 18 months from today. In the level 4 role, typically of a vice president of a large company, or a president of a smaller company, a person would try to attain the business goal three to four years into the future.

As roles grow in complexity, the level 5 president of a company makes decisions into the future of the entire enterprise, 5–10 years into the future, deciding on new markers, technologies, investments, products, merges, and acquisitions. The size of this business, typically, would be between $100 million to $1 billion dollars annually. The decisions of the CEO of a large multinational, in the level 7 or 8 role, impact generations of the future products, and all stakeholders. For example, to develop a new airplane would take several generations of planning for the return on investment, predicting the future of the airspace technology, demands, materials, markets, and other national and global factors. Another example would be city planning, or building a space colony on the Moon or planet Mars. Such endeavors may take decades if not—generations – to complete.

4. Leadership roles in work levels 5 through 8

Following Jaques’ organization theory, leaders must be able to work and operate at the higher levels of work to plan for the organization’s future years from today, encapsulating all lower-levels implications and complexities. The larger the organization, the higher the levels of work the leaders must be able to work at. Therefore, in the context of today’s global civilization, the majority of leadership roles in large organizations must be in levels 5 through 8 (based on the size of the company), as follows Table :

Table 2. Required Leadership Roles in Large Organizations

The predictive aspect of the theory is that if leaders operate at these highest levels of work (strata 5 through 8), organizations and societies should do fairly well, without any major mishaps or crises. A contradictory finding—that indeed leaders do operate at levels 5 through 8, and there are still lots of crises—would invalidate and refute the theory, satisfying Popper’s refutability (falsifiability) criterion (2002). 90 seconds to midnight is a global—“unprecedented danger” – crisis that we all live in today (2023).

5. Organizational studies

Having a particular interest in Jaques’ organizational theory, I have conducted multiple organizational studies to measure roles for work complexity, identifying longest tasks in these roles, and also to verify independently if the theory holds (I typically don’t trust any findings unless I independently verify them, stemming probably from a faulty leadership personality). I assumed that I would have no trouble finding top level leadership roles in larger organizations, such as in government, commercial industry (large multinationals), military, academia, and other types of organizations. I thought that I could easily identify level 5, 6, 7 and 8 roles, and, as a scholar, describe the longest tasks and challenges these people—leaders – face in their daily day-to-day work.

6. Methodology

In and around 1999/2000, initially as part of my doctoral study at The George Washington University, a fairly famous school—historically – for alternative and controversial management schools of thought, I went to work traveling all over the United States, and some counties in Eastern Europe. My goal was to test new propositions and also to replicate Jaques’ studies, as well as of other scholars, especially in the data-collection methods, and obtain—measure precisely—the level of work of each employee in the company. Jaques (Citation1999, Citation2000, Citation2021, Citation2022) trained me personally in his data-collection methods. It was important to me not to deviate and use exactly the same methods and procedures of data collection as required by the theory. Those methods are also described in a variety of scholarly publications and books by Jaques, Lee, Kraines, and others (1999, G. A. Kraines, Citation2001; G. Kraines, Citation2021).

In a nutshell, the companies invited me to visit and provided access to their employees. I visited them in person, and, when in an unacceptable area, such as the jungle or classified location—via the telephone and/or video-conference. The protocol remained the same. During the visit, I privately met with every employee, often in the organization’s private conference room. Usually, I am able to meet approximately 20 to 30 employees a day. Before the visit and the start of the organizational study, the organization initiates and agrees to the study, as long as all private details remain private. I am authorized to generalize and discuss the general findings to advance or refute the theory publicly, which is how this set of papers has been coming along.

During the meeting with each manager, I confirm who his or her direct subordinates are. The organization has already provided me with the organizational chart; so, I know the reporting structure ahead of the start of the study, at least how it is on paper. For each subordinate, I ask the manager what each subordinate’s longest task is in the role (nothing controversial so far). Let’s say the manager says 9 months for a particular subordinate, on task X (I record all responses by hand on paper). Afterwards, when I meet with this subordinate employee, I also ask what his or her longest task is. Typically, in most cases, the employee would confirm the same timeline, sometimes slightly less, such as 8 months, for the same task X. Both would fall into the same work level, and thus, correspond to Level/Stratum 2 role (the words level and stratum are used interchangeably in this paper, and other works by all scholars and practitioners worldwide).

If there are discrepancies, let’s say the manager says 2 years for the longest task, and the subordinate claims 2 months for the same task, I then verify the tasks, revisit each, and finally, if I cannot reconcile the tasks, I get them both into the same conference room to understand how and why they view the same task differently. There is nothing controversial in these task surveys.

In practice, task discrepancies happen rarely, and there was only one case that in which both, the manager and in this case—his direct subordinate could not resolve. The manager saw the subordinate’s role very differently from the subordinate himself. After discussing the subordinate’s role of Marketing Director, both, the Marketing Director and Managing Director, together in the same conference room could not reconcile the longest tasks. In this special case, however, the Marketing Director has already resigned, and was likely stating his views what the role should be, during his last days in the company.

For further verification, especially, in larger organizations in the higher levels of work, I also check to make sure that if the manager’s role is in level 5, as he or she might claim, it means that the subordinates’ roles should also fall into level 4 – with proper supporting tasks, and not levels 2 or 1, thus, skipping multiple work levels. For example, if the manager claims a 7-year task in his or her role, and all of his/her direct subordinates state 2-week-deadlines, this obviously makes little sense, requiring further verifications. How can the subordinates’ work of 2-week deadlines support the manager’s task of 7 years? This type of a relationship is only suitable for administrative assistants, for example, a Vice President’s secretary, but not other direct subordinates. When someone is working on a 7-year project, for example, expanding into a new global market, he or she would find it impossible to have a subordinate team only working on weekly-tasks. The only working-relationship possible in this case would be of an administrative assistant/secretary, who would be supporting the boss with organizing daily activities, such as the calendar. If the boss’ task was 7 years, the subordinate supporting-tasks should typically fall into 3- to 4-year ranges, who would typically then also manage their own teams in 1-to-2 year sub-taskings ranges. To reconcile the differences, I would normally present the tasks-findings to the organization’s leaders. According to the theory, and also my experience and practice, if all subordinates’ roles are in a particular work level, a manager’s role is always one level above, coordinating and synthesizing the work of lower levels. For example, in academia, a college may apply for accreditation 3-to-4 years into the future. This means that the subordinate teams would have to collect and analyze data, within 1-to-2 years, while another team may coordinate and achieve other objectives, all of which are to be organized, and jointly-put-together for a successful accreditation effort.

7. Data collection, protocol, and analysis

In some of my studies, I had access to what my colleagues would consider level 7 or 8 roles in very large organizations (Clement, Citation2012). In these organization, besides meeting with lower-level employees, who would normally work in levels 1 and 2, I also surveyed higher level employees, believed to be at level 5 and above, at least according to the employee rank, position, and title in the organization. As found and confirmed by Jaques (Citation1996), I thought I would encounter a similar pattern of higher-level work, and mark that a particular role is in level 8, 7, 6, or 5. The method of obtaining the timeline of the longest tasks, as described above—the study protocol itself—is the same. Especially, having measured the roles for over several years, I have obtained substantial skills, knowledge, and experience at getting at the accurate measures quickly, as well as resolving potential obstacles. Confidently, I went forward measuring the longest tasks of top executives, thinking that I would find similar patterns Jaques, Clement, and others have found earlier. In a way, it was quite interesting to meet people who typically were older than me, and who have spent twenty-to-thirty years in their careers having attained the highest ranks in their organizations.

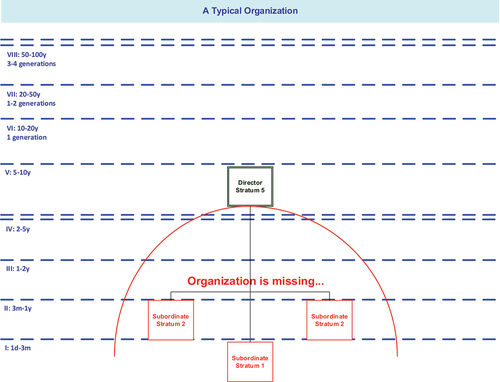

To my surprise, I typically found few to no roles in levels 5 and above where I was expected to find plenty. Often, top leaders would claim a higher level of work, but then I would find no supporting organization or task to support the claim of the high level of work. A two-week longest task is not an example of a level-8 work in the role. An example of a hollow organization is depicted in Figure .

Jaques found that SES (a U.S. Government Senior Executive Role, typically either career-based or politically-appointed), VPs, EVPs, etc. must all work in the highest—levels 5 to at least 7 – levels of work (1996). I kept on finding little evidence. In a way, I was finding the levels 2 to 4, and occasionally 1. All of these findings were presented and discussed with the leaders, with little to no disagreement. Further, meeting with these executives, they privately agreed about the short-term nature of their work and short-term focus of their organizations, something that Deming also found in his studies decades earlier (1992, 1994), applying fundamentally different approaches to his organizational studies. Clement (Citation2015), disagreeing with my findings, calls today’s short-term phenomenon normal—even naming it compressed organization, a term that Jaques came up with describing the expeditionary Army at war—as they operate under great duress (2002). Needless to say, a theory either holds or it doesn’t, without many exceptions. Therefore, I proceeded further: a good theory cannot have unwarranted exceptions. It is either that all organizations comply with the same organizational principles in all circumstances, or the theory simply does not hold and/or needs rethinking. Therefore, I cannot agree with Clement, whom I highly respect for his remarkable organizational contributions and studies worldwide (2015). A level 5 executive doing level 2 work is actually working at level 2, and not level 5-under duress.

8. Initial analytical insights

There are two possible explanations for the lack of evidence of higher levels of work (5 and above) in organizations today. One is that Jaques’ theory of organizations is simply incorrect, and complex work occurs through lesser timespans, and lowest levels of work, strata 1 through 4, as other scholars might claim, operating under great duress (Clement, Citation2015). Thus, no leader works into the distant future of the enterprise or society, and likely ends planning and thinking with five or less years into the future, which is a typical level 4 role, historically also a traditional planning mode of the former Soviet Union, during which the country has slowly disintegrated over the course of its existence.

If Jaques’ theory is incorrect, and indeed the leaders can successfully work and plan only to a maximum of five years into the future, organizations and societies must do quite well and not experience many significant crises and troubles. Analyzing the business and global environments today, it is obvious that this view is fundamentally incorrect. USSR did not do well under the five-year-planning cycle, having rotted in its core, ultimately disintegrating, the process of which is still unfolding today in Russia, Ukraine, and other former parts of the USSR.

Other corporations and government systems, similarly, have gone in and out of crises, quite eloquently observed and described by Deming (Citation1992, Citation1994), because they have not focused, planned, and prepared for the long-term future of their enterprises and societies. Other scholars, independently, and using different methods of study, have come to similar conclusions, most notably Deming (Citation1992, Citation1994), Ricks (Citation2012), and others. Perhaps, organizations and societies today desperately need new leaders and different leadership systems and approaches to enable a longer-term vision and planning of the future.

9. Leaderless organizations

A leaderless organization is a structure that misses the top leadership roles in which leaders plan and lead the organization into the distant—long-term—future of the enterprise or society. Such an organization functions on inertia and heads nowhere, as Deming would claim (Deming, Citation1992, Citation1994). The leaderless organization does not plan for new products and services, does not innovate and reinvent itself, but simply attempts to live in the Machiavellian’s ordinary status-quo—continue the business as is, hoping that the future resembles the past, a fallacy exposed by Taleb (Citation2010) and others. Stagnation and decay are at the core of such an organization or society, unable to withstand the upcoming events and crises. Mastio et al. (Citation2021) describes leadership and organizational inertia, leading to and incapable of responding to crises, further and independently confirming similar findings.

Table exposes the leadership voids in the leaderless organization: no person is working in the level 5 through 8 roles:

Table 3. Leaderless Organizations – Findings

Other scholars have confirmed similar findings, but have interpreted them differently (Clement, Citation2015). Clement (Citation2015) calls this organization compressed—operating under duress, in which all work is conducted through lower levels of work, as if it is operating under a great crisis. The organization is indeed in crisis, self-imposed, with the root cause that no leader is working in the highest levels of work to resolve the current and future crises, as follows in Table :

Table 4. Organization’s Compressed Mode

Organizations and societies are in crises today—and 90 seconds to midnight is something we all must be aware—because very few leaders or possibly no one is working in the highest levels of work, strata 5 through 8. Even Clement says that is easier to work on projects results of which are immediately seen, but difficult to work on projects 10, 15, 25, and 30 years into the future.

Today’s societal crises are partly the result of the modern leaderless organizations, of work that is not being done. Procrastination or movement by a crisis is not a solution. An organization or society that does not actively create its future, eventually, will experience a different future it desires, a calamity, because the real problems of tomorrow remain unaddressed and grow (Machiavelli, Citation1505; Deming, Citation1996, Ivanov, Citation2011). Most totalitarian organizations and societies suffer from the leadership crisis: the organization has no leaders to plan and lead into the future. All we focus is “agreement” with the “leader” (Sharansky, Citation1998). Putin’s Russia is one of such sad examples. Submission and obedience to the leader, who may or may not have full faculties of the mind and/or may be hallucinating, has become the highest value of such enterprises (Milgram, Citation1974), an insanity in and of itself (Fromm, Citation1955).

10. Organizational two-modes: Let’s get rid of competent employees

Why does the leaderless organization or society occur? Our hypothesis is that most organizations operate in two distinct modes: get competency or get rid of competency (today, mostly—get rid of competency) as shown in Table ):

Table 5. Organizational Two-Modes

When the top roles are filled with people incapable of operating at the highest levels of work, the organization falls into the mode of incompetency, in which capable people can no longer function. Other organizational norms become more important—pleasantries, flattery, and appearance of agreement, but internal fear, paralysis, submission, and incompetence dominate the organization. Many organizations and societies today fall into this stagnating, sad, and unnecessary paradigm. Our civilization is at risk (Chomsky, Citation2023).

When the organization’s top leader is competent, this person can articulate the future that makes sense and is based on reality to which people can relate. For example, both Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos articulate with ease the future of where they are going and why. When the leader is competent to operate at the highest work level—level 8 (or even above, as Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos have demonstrated)—planning begins to make sense, which in the other paradigm is absent (when the leader can only work in level 3, for example, and/or has lost his or her mind). Both, Musk and Bezos see the world generations from today, and actively plan and act today to achieve the distant goals. Musk attempts to build a multi-planetary civilization (2016), and in order to achieve this goal, has build many different companies, including Tesla and SpaceX. Bezos, not far behind, sees a trillion people operating in space (2018), launching Blue Origin, and expanding Amazon.

The higher-mode leader can only accomplish new objectives when he or she is being supported by competent subordinates, operating one-level-below, to support the longer-term objectives. To be successful, he or she will, out of necessity, start replacing incapable executives, as Generals Pershing and Marshall did to succeed in WWI and WWII (Ricks, Citation2012). Thus, a level-8 leader will employ subordinates who could work in level 7, and will not tolerate anyone who could not function at this level, for example, level 3. Today, you would not find Elon Musk’s direct subordinates operating at level 3. Recursively, this work-structure propagates to the front-line.

Once the proper capability structure is in place and is embedded and propagated into the organizational hierarchy (everyone is working in their proper levels of work), the organization’s leader will take risks and plot the new course, usually with excitement and energy, towards the future, having placed proper leaders in work levels 5 through 8, harmonizing the organization, because they are actually working in these levels on specific long-term tasks.

The modern corporation, government, and military today are unprepared and paralyzed because most leaders do not and cannot operate in work levels 5 through 8, either because of the lack of capability or the lack of organizational system and support. There are no bad soldiers (front-line employees), only bad generals (attributed to Napoleon) (Ricks, Citation2012).

When the person is promoted beyond his or her capability, he or she is overcome with fear, undergoing a complete change of personality. He or she becomes paranoid, stressed, overcome with suspicion and mistrust, which then fill the enterprise. Here are some of the fears the person experiences:

Fear of the job

Fear of making decisions/paralysis

Fear of being exposed

Fear of critics

Fear of competent subordinates

Fear of anything new/innovation

Incapable on focusing on the future of the enterprise, and not fully understanding the work at the highest level, this person now focuses on not getting fired, often done by:

Shutting down new ideas and creativity

Stopping innovation

Removing capable subordinates

Focusing on status-quo/no changes

Hiding away, as President Putin has been demonstrating (2022)

Death by PowerPoint, fear, and indecision are usually the state of the organization. The organization responds to the vacuum of leadership by low morale, as well as:

Massive Fear

Doubletalk (Sharansky, Citation2006, Orwell, 1961)

Bull/Façade/Wasteful-Work

Massive underemployment and boredom

Demeaning human spirit

Organizational Paralysis, Waste Away, and Marasmus

Organizational and Societal Crises (something we all may have experienced lately)

Needless to say, when the organization is in fear, a feararchy, an organizational hierarchy in fear, is an unlikely success story, or capable of moving anything forward.

11. Conclusion

Man can adapt himself to slavery, but he reacts to it by lowering his intellectual and moral qualities; he can adapt himself to a culture permeated by mutual distrust and hostility, but he reacts to this adaptation by becoming weak and sterile. … He can adapt himself to almost any culture pattern, but in so far as these are contradictory to his nature he develops mental and emotional disturbances which force him eventually to change these conditions since he can not change his nature.

Erich Fromm

Every organization must identify the size of all roles in its system, especially in levels 5 through 8, which are the highest levels of work in the organization, and the longest tasks in the these roles. Every organization must articulate the work in these highest leadership levels, as the U.S. Army did in their General Orders 00 (2008). Everyone in the organization must know what the work entails in the higher levels of work, what these tasks are, and what the people employed in the highest roles do.

Once the role sizes are well-understood and discussed, the organization will have to identify and match the capable leader to the role, which is another altogether difficult problem, possibly the root of the entire issue—selection of the right person to the role. Even General Marshall, demanding capability, could not articulate what he was looking for, highlighting such personality traits as good common sense, study of the profession, physical strength, cheerfulness and optimism, energy, loyalty, determination, and others (Ricks, Citation2012). It is likely that the root of the leaderless organization and subsequent organizational crises are that often the selected top leaders are not capable of the roles they occupy.

To get out of the crises, organizations should start selecting level 8 capable people into the level 8 organizational roles. These new leaders would raise the level of work necessary to un-compress the organization to confront the world challenges and crises. Ridding organizations of incapacity by reassigning people to the roles they naturally fit would help create the organization capable of handling the strategic complexities the modern civilization offers, and possibly harmonize the current unfolding global crises.

Is the organization where you work at today a leaderless organization? Is the fear present in your organization? If you possibly may have answered yes, there is a likelihood that the organization in which you work may be a leaderless organization.

The research itself needs a further study. It is necessary to reassess all government, university, and corporate structures to understand the work at the highest levels of work, in levels 5 and above. Ideally, this would also be conducted by other—independent – scholars so that as a society we may build better organizations, and as scholars, come up with a better organizational theory to organize ourselves for the civilization of the future.

Other scholars, as well, describing similar issues, explore alternative organizational and societal designs. Yunus (Citation2007, Citation2010) develops his notions of social businesses, explaining new ways a business system could function aligning with the society, employees, and community. To Yunus’ credit, his work does not abandon Capitalism and its philosophy, only attunes and accommodates the organization to function in a better way. Other recent ideas also include B-Corporation certificate (2023), and Holacracy (2019). Many new ideas are needed, to get the world away from the 90 seconds to midnight crisis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Al Amiri, N., Rahima, R. E. A., & Ahmed, G. (2020). Leadership styles and organizational knowledge management activities: A systematic review. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 22(3), 250–13. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamaijb.49903

- Brown, W., & Jaques, E. (1965). Glacier Project Papers: Some Essays on Organization and management from the Glacier Project Research. Heinemann.

- Chandler, A. D., Jr. (1977). The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Harvard University Press.

- Chomsky, N. (2019). Totalitarian Corporations. Chomsky’s Philosophy. YouTube. www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uzs_0yqTuvI

- Chomsky, N. (2023). Q&A with Noam Chomsky about the Future of our world for the SXSW23 Wonder House. www.youtube.com/watch?v=dUOvpIOAmYk

- Clement, S. D. (2015). Time-span and time compression: New challenges facing contemporary leaders. Journal of Leadership and Management, 2(4), 35–40. http://www.leadership.net.pl/JLM/article/view/65

- Deming, W. E. (1992). Out of the Crisis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Deming, W. E. (1994). The New Economics: For industry, government, education. MIT/CAES Press.

- Dwivedi, A. (2022). Bibliometric analysis of management and leadership in the sustainability agenda. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003190820-19

- Fabiaan, V. V. (2015). The Disruptive Competence: The journey to a sustainable business, from matter to meaning. In De Eendracht (Vol. 26, pp. 2920). Compact Publishing.

- Fromm, E. (1955). The Sane Society. Fawcett Publications.

- Ivanov, S. (2011). Why Organizations Fail: A Conversation About American Competitiveness. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 4(1), 94–110. http://www.leadership.net.pl/JLM/article/view/51

- Jaques, E. (1996). Requisite Organization: A Total System for Effective Managerial Organization and Managerial Leadership for the 21st Century. Cason Hall & Co.

- Jaques, E. (2002a). The Psychological Foundations of Managerial Systems: A General Systems Approach to Consulting Psychology. Midwinter Conference of the Society of Consulting Psychology.

- Jaques, E. (2002b). Orders of complexity of information and of the worlds We Construct.: Unpublished Paper.

- Kraines, G. (2021). Management Productivity Multipliers: Tools for Accountability, Leadership, and Productivity. Career Press.

- Kraines, G. A. (2001). Accountability Leadership: How to Strengthen Productivity Through Sound Managerial Leadership. Career Press.

- Lee, N. R. (2017). The Practice of Managerial Leadership. Xlibris.

- Machiavelli, N. (1505). The Prince. Airmont Publishing Company, Inc.

- Mahdawi, A. (2023). Russia preparing to mobilise extra 500,000 conscripts, claims Ukraine. www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/06/russia-preparing-mobilise-extra-500000-conscripts-claims-ukraine, Jan, 1–3.

- Mastio, E. A., Clegg, S. R., Cunha, M. P. E., & Dovey, K. (2021). Leadership Ignoring Paradox to Maintain Inertial Order. Journal of Change Management, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.2005294

- Milgram, S. (1974).Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View . Harper & Row Publishers, Inc.

- Popper, K. (2002). The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Routledge.

- Ricks, T. E. (2012). The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today. The Penguin Press.

- Sharansky, N. (1998). Fear No Evil. PublicAffairs.

- Sharansky, N. (2006). The Case for Democracy: The Power of Freedom to Overcome Tyranny and Terror. Balfour Books.

- Taleb, N. N. (2010). The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. Random House.

- Yunus, M. (2007). Creating a World without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism. Perseus Books Group.

- Yunus, M. (2010). Building Social Business: The New Kind of Capitalism that Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs. Perseus Books Group.